Abstract

In recent years, measures proposed to address urban flooding caused by extreme rainfall often demand substantial investment, restricting their broad implementation. This study quantitatively assessed the inundation situations of 138 capital cities under both normal and extreme rainfall conditions. Using machine learning techniques, we found that grey infrastructure—closely commensurate with a city’s economic development—dominates flood reduction during normal rainfall events. However, during extreme precipitation, as rainfall intensity rises, the marginal effectiveness of grey infrastructure declines markedly. In contrast, green infrastructure and topography—less commensurate with economic development—play increasingly critical roles in mitigating urban flooding. These findings suggest that economic development has a limited impact on urban flooding during extreme rainfall events. Rationally utilizing topography and enhancing green spaces provides a cost-effective nature-based solution, which is particularly important for urban planning in low- and middle-income countries undergoing rapid urbanization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extreme precipitation is occurring more frequently around the world1,2, and floods have become one of the most damaging natural disasters, resulting in billions of dollars in losses and thousands of deaths globally each year3. Cities, where human activities are most concentrated, suffer the most damage4. Under the influence of climate change, the frequency and intensity of urban flooding caused by extreme precipitation have noticeably increased around the world, with the affected area gradually expanding5,6. Urban flooding is no longer a regional special problem, but has gradually become a global problem7,8,9. At present, urban flooding caused by extreme precipitation has become a major problem that is troubling the urban construction and economic development of countries around the world5,7,10,11. Hence, it is imperative to implement effective measures in order to enhance the city’s capacity for managing urban flooding and mitigating its impact.

Existing research has affirmed that gray infrastructure, green infrastructure, and topography are the primary factors influencing a city’s coping capacity against urban flooding10,12,13,14,15. Nevertheless, in contrast to infrastructure construction, alterations in topography are relatively more challenging to implement14,16. Moreover, some studies have verified that as urban systems grow more intricate, the influence of topography on flooding is gradually diminishing17. Consequently, a greater amount of research has centered on gray infrastructure and green infrastructure18,19. Gray infrastructure pertains to traditional municipal infrastructure, specifically referring to artificially constructed facilities aimed at addressing floods and averting losses to personal and property, including urban rainwater pipe networks, drainage pumping stations, flood control trenches, and flood control walls18,20,21. Research on gray infrastructure mainly focuses on formulating optimal construction or renovation plans for facilities such as pipe networks based on the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation18,22,23,24. Green infrastructure refers to an interconnected network of green spaces composed of open areas and natural landscapes, encompassing large-scale features such as greenways, wetlands, and rain gardens, as well as smaller-scale or household components like residential rain barrels, green roofs, tree pits, and balcony vegetation. Its core function lies in harnessing natural elements—plants, soil, and wetlands—to absorb, filter, and store stormwater, thereby reducing reliance on conventional gray infrastructure25,26,27. Existing research primarily focuses on the relationships between the spatial configuration of green spaces and their stormwater regulation and storage capabilities, as well as how multi-scale green installations, through spatial connectivity, collaboratively enhance drainage systems at the community and household levels. This multi-scale approach provides critical theoretical foundations for optimizing the stormwater retention function of urban green spaces28,29,30. These two aspects of research offer substantial support for cities to enhance their ability to mitigate urban flooding. However, in practice, the construction of infrastructure typically demands a considerable investment, particularly for gray infrastructure, which is burdensome for the majority of cities31,32. Even in cities of developed countries, given that most pipe networks are covered by buildings, the vast majority also struggle to bear the cost of upgrading the networks33. Therefore, cities at different economic development levels possess dissimilar economic capabilities to enhance drainage capacity and adopt inconsistent adaptive strategies. However, previous studies proposing technical solutions for urban flooding often overlooked cities’ economic capacity and development levels. This creates implementation challenges for promoting such solutions globally, especially across cities at varying development stages34. Hence, it is necessary to analyze the contribution degrees of various resilience facilities in cities at different economic development levels when dealing with urban flooding, and on this basis, propose flooding mitigation strategies commensurate with the economic development level.

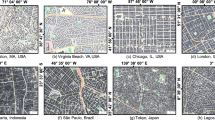

The core objective of this study is to further analyze the main influence mechanisms of gray infrastructure, green infrastructure and topography on inundation in capital cities of 138 countries at different economic levels when they are exposed to regular heavy rainfall (with a 10-year return period) and extreme rainfall events (with a 100-year return period). The level of economic development is classified by per capita gross domestic product (GDP). Specifically, countries with a per capita GDP lower than 1200 USD are classified as low-income countries, those with a per capita GDP ranging between 1200 USD and 12,000 USD are considered as middle-income countries, and countries with a per capita GDP exceeding 12,000 USD are designated as high-income countries. Based on this, we discuss the optimal disaster reduction path configuration for countries at different economic development levels in the process of sustainable urbanization. This will contribute to advancing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly in underdeveloped regions and developing countries35. As the capital city of a nation, it takes priority in national flood adaptation as it represents protections on the functions of governance, thus it typically embodies a higher level of flood protection within the country. Consequently, we identified the capital cities of 138 nations and employed a volumetric comparison method to quantitatively assess inundation scenarios during regular heavy rainfall (with a 10-year return period) and extreme rainfall events (with a 100-year return period). These capital cities span diverse geographical regions, climate zones, and economic development levels. Such diversity enables us to capture various scenarios and variables related to urban flood risks (Supplementary Table 1). We represented gray infrastructure, green infrastructure, and topographic conditions by drainage network density, green space ratio, and topographic relief, respectively24,36,37. By comparing the differences in flood risks among countries at different economic development levels, the main influence mechanisms of gray infrastructure and green infrastructure on urban flooding, as well as the impact of topographic conditions, were further elucidated using machine learning methods. This analysis result will provide an important reference for cities at different levels of economic development to formulate targeted and economically compatible strategies for urban flooding management.

Results

Distribution pattern of urban flood

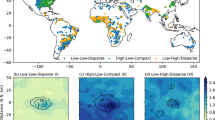

The inundation ratio for the capitals of 138 countries under different rainfall intensities is shown in Fig. 1. Overall, under a 10-year return period rainfall event, the inundation ratio for the capitals of low- and middle-income countries is markedly higher than that of high-income countries. The average inundation ratio reaches 6.03% for low- and middle-income country capitals, compared to only 2.93% for high-income country capitals (Fig. 1a). There is a significant negative correlation between inundation ratio and economic development level (95% confidence interval is significant), indicating that as economic income increases, inundation ratio decreases significantly (a 0.06% decrease in inundation ratio for every $1000 increase in per capita income) (Fig. 1c). Under a 100-year return period rainfall event, the inundation ratio for the capitals of countries at different economic development levels is relatively high, with an average inundation ratio of 6.99% for high-income country capitals and 10.15% for low- and middle-income country capitals (Fig. 1b). At this stage, the correlation between the inundation ratio and economic development level is no longer statistically significant (p > 10%) (Fig. 1d), indicating that an increase in economic income during a 100-year return period rainfall event will not lead to a reduction in the inundation ratio.

a Inundation ratio with a 10-year return period; b inundation ratio with a 100-year return period; c correlation between inundation ratio and economic level in the 10-year return period; d correlation between inundation ratio and economic level in the 100-year return period. The yellow dots represent the capitals of low- and middle-income countries, while the purple dots represent the capitals of high-income countries.

This implies that high-income countries are already equipped to manage regular heavy rainfall, and their capacity to do so is growing as their economic income increases. In contrast, low- and middle-income countries struggle to effectively handle regular heavy rainfall due to their lower economic income, resulting in a greater impact. However, when the rainfall level reaches the 100-year return period standard (extreme rainfall events), the influence of economic income on enhancing drainage capacity becomes less pronounced. At this point, all countries, regardless of their economic income level, face a relatively equitable situation during extreme rainfall events. This suggests that both high-income and low- and middle-income countries currently lack the ability to cope with extreme rainfall disasters38,39. This observation aligns with the actual occurrence of global urban flooding in the twenty-first century. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, climate change-induced extreme rainfall was relatively limited40,41. Urban flooding primarily resulted from regular heavy rainfall and occurred more frequently in low- and middle-income countries, with few instances reported in high-income countries42,43. However, after 2010, frequent extreme rainfall events (exceeding the 100-year return period) caused by climate change became widespread globally44,45. Consequently, urban flooding ceased being solely a problem affecting low- and middle-income countries but gradually evolved into a global issue7,44.

Disparities in gray infrastructure

The construction of gray infrastructure, which plays a crucial role in enhancing drainage capacity, often necessitates substantial human and material resources46,47. Therefore, the level of gray infrastructure construction is closely associated with the economic level38. As shown in Fig. 2, there is a strong positive correlation between economic level and the density of drainage networks (significant at the 95% confidence interval). Furthermore, there are substantial disparities in basic gray infrastructure construction among capital cities in countries with varying levels of economic development. The average density of drainage networks in high-income country capitals is nearly 17 times that of middle- and low-income countries.

a The density of drainage networks in 138 capitals; b correlation between drainage network density and economic level; correlation between inundation ratio and drainage network density at different precipitation levels, (c) ≤100 mm/d, (d) 100–200 mm/d, (e) >200 mm/d. The yellow dots represent the capitals of low- and middle-income countries, while the purple dots represent the capitals of high-income countries.

We employed XGBoost, an interpretable machine learning algorithm, to quantitatively assess the impact of gray infrastructure components on the inundation ratio. As depicted in Fig. 3, under a 10-year return period rainfall scenario, the drainage network is the primary factor influencing the inundation ratio in high-income country capitals. Its feature importance value reaches 0.7784, indicating it as the largest contributor to reducing the inundation ratio. When the rainfall intensity increases to a 100-year return period level, the feature importance value of the drainage network decreases to 0.3064, and its impact on the inundation ratio begins to decline. The drainage networks in the capital cities of low- and middle-income countries are relatively poor, and the existing drainage capacity is insufficient to affect the flooding level. The feature importance value of the drainage network in the 10-year and 100-year return period rainfall levels is relatively low. This is basically consistent with the distribution pattern of inundation ratio, where the gray infrastructure in the capital cities of high-income countries has been built and improved over a long period of time and has a good ability to cope with regular heavy rainfall, but lacks the ability to cope with extreme rainfall. Most capital cities of low- and middle-income countries are still in the early and middle stages of rapid urbanization, and the urban gray infrastructure construction is relatively limited, with a general lack of capacity to cope with flood disasters.

The purple bars represent the feature importance of various factors on the inundation ratio in the capitals of high-income countries, while the yellow bars represent the corresponding feature importance in the capitals of low- and middle-income countries. The colors transition from light to dark shades of purple and yellow, respectively. A darker bar color signifies a stronger association between the factor and the inundation ratio.

We further analyzed the contribution of gray infrastructure to the inundation ratio at different precipitation levels, dividing the precipitation level into three categories: ≤100 mm/d, 100–200 mm/d, and >200 mm/d. The difference in the role of gray infrastructure at different precipitation levels is obvious (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Specifically, at the precipitation level of 100–200 mm/d, the drainage network makes the greatest contribution, while the contribution of the drainage network markedly decreases when the precipitation level rises to >200 mm/d. From the marginal benefits, the density of the drainage network is negatively correlated with the inundation ratio at both the precipitation levels of ≤100 mm/d and 100–200 mm/d (both with a 95% confidence interval significance) (Fig. 2c, d). The marginal benefits are most obvious at the precipitation level of 100–200 mm/d, with the drainage network density decreasing the inundation ratio by 0.31% for every additional 1 km/km2. When the precipitation level is >200 mm/d, the correlation between the density of the drainage network and the inundation ratio is no longer significant (p > 10%) (Fig. 2e), meaning that increasing the density of the drainage network would not decrease the inundation ratio at this point.

Therefore, the construction and optimization of gray infrastructure plays an important role in enhancing a city’s ability to cope with regular heavy rainfall, but its effect on coping with extreme rainfall is not obvious. That is, the difference in gray infrastructure resulting from economic level mainly manifests in the ability to cope with regular precipitation, and the ability to cope with extreme precipitation will not show marked differences between countries with different economic levels38.

Increasing effect of green space

In recent years, optimizing green space has emerged as an important approach to enhancing drainage capacity due to the high cost of gray infrastructure construction and improvement29,47. Green space mitigates rainwater runoff through its natural properties of infiltration and water retention, a role that has been acknowledged by the academic community12,30. Unlike gray infrastructure, the presence of green space is not closely tied to economic development levels (Fig. 4). The average green space ratio in the capitals of high-income countries stands at 35.77%, which is comparable to the 29.71% found in middle- and low-income countries.

a The green space ratio in 138 capitals; b correlation between green space ratio and economic level; correlation between inundation ratio and green space ratio at different precipitation levels, (c) ≤100 mm/d, (d) 100–200 mm/d, (e) >200 mm/d. The yellow dots represent the capitals of low- and middle-income countries, while the purple dots represent the capitals of high-income countries.

In the scenario of a 10-year return period rainfall, the contribution of green space to the inundation ratio in the capital cities of high-income countries is limited, with a feature importance value of 0.17 (Fig. 3). When the rainfall intensity increases to a 100-year return period level, the contribution of green space becomes the largest factor, with a feature importance value of up to 0.65 (Fig. 3). In the case of middle-and low-income countries, the feature importance value of green space in the 10-year and 100-year return period rainfall scenarios is relatively low. That is, in the case where the drainage network is relatively complete, the role of green space is more pronounced.

There is a significant negative correlation between the proportion of green space and the inundation ratio at three precipitation levels of ≤100 mm/d, 100–200 mm/d, and >200 mm/d (with a 95% confidence interval being significant) (Fig. 4). When the precipitation rises to 200 mm/d or above, the drainage contribution of green space is the largest, surpassing the density of drainage networks to become the most important drainage factor (Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, as the intensity of precipitation increases, the marginal benefits of increasing the proportion of green space become increasingly pronounced. At ≤100 mm/d or 100–200 mm/d levels of precipitation, a 1% increase in green space corresponds to a reduction in inundation by 0.02% and 0.03%, respectively (Fig. 4). However, at a level of 200 mm/d precipitation or higher, a 1% increase in green space results in an associated decrease in inundation by as much as 0.16% (Fig. 4).

Consequently, optimizing green space can have the most substantial impact on mitigating flooding caused by extreme precipitation, and the more intense the precipitation, the more pronounced the role of green space. Capital cities with a large amount of green space have a relatively smaller inundation ratio. Compared with spending a large amount of money to improve the drainage capacity of drainage networks, expanding the area of green spaces is more effective in reducing the impact of extreme precipitation and at a lower cost12,47.

Implicit contribution of terrain

In addition to the above two factors, the terrain’s elevation and slope also have a direct impact on the efficiency of urban drainage48. While there is no correlation between topographic relief and economic development (Fig. 5), from a distribution perspective, capital cities in high-income countries tend to be situated in areas characterized by lower ground slopes compared to those in low- and middle-income countries49.

a The topographic relief in 138 capitals; b correlation between topographic relief and economic level; correlation between inundation ratio and topographic relief at different precipitation levels, (c) ≤100 mm/d, (d) 100–200 mm/d, (e) >200 mm/d. The yellow dots represent the capitals of low- and middle-income countries, while the purple dots represent the capitals of high-income countries.

From the contribution of topographic relief to the inundation ratio, due to the limited gray infrastructure such as drainage networks, topographic relief is the main factor affecting flood drainage in low-and middle-income countries, with the feature importance value reaching 0.5639 and 0.7717 at the 10-year and 100-year return period rainfall levels, respectively (Fig. 3). In high-income countries, the role of topographic relief can be ignored regardless of the rainfall levels at the 10-year or 100-year return period.

When considering the intensity of precipitation, there is no significant correlation between topographic relief and inundation ratio at the relatively low precipitation level of less than 100 mm/d (p > 10%). At the relatively higher precipitation levels of 100–200 mm/d and greater than 200 mm/d, there is a significant negative correlation between topographic relief and inundation ratio (with a 95% confidence interval), and the role of topographic relief becomes increasingly significant as the intensity of precipitation increases. Specifically, for precipitation levels of 100–200 mm/d, the inundation ratio decreases by 0.14% for every 10 m increase in topographic relief; for precipitation levels exceeding 200 mm/d, the decrease is even more substantial at 0.41% per every 10 m rise in topographic relief (Fig. 5).

Therefore, at lower precipitation levels, changes in topographic relief do not enhance drainage capacity. As precipitation intensity increases, the role of topographic relief begins to emerge, and the greater the precipitation intensity, the more important its role in reducing flooding becomes. The topographic relief determined at the time of city selection generally does not change easily. However, as the increase in extreme precipitation intensity caused by climate change begins to make the contribution of topographic relief to drainage capacity more apparent, the geographical situation of the capitals of various countries becomes an important factor. Once both gray and green infrastructure reach their drainage capacity limits, topographic relief emerges as a critical factor. Cities with substantial topographic relief experience concentrated flow of accumulated surface water preferentially toward low-lying areas, thereby reducing the inundation extent in higher-elevation regions and consequently lowering the city’s total inundation ratio. Conversely, in cities with minimal topographic variation, the lack of lateral flow momentum makes it difficult to achieve substantial changes in total inundation ratio through topography-driven rainwater redistribution. Consequently, under extreme precipitation conditions that exceed the combined drainage capacity of gray and green infrastructure, the topographic advantages of capitals in low- and middle-income countries become more pronounced compared to those in high-income countries, as these capitals are typically located in areas with greater topographic relief.

Discussion

Our study found that urban gray infrastructure supported by economic foundations in high-income cities could effectively cope with regular heavy rainfall (with a 10-year return period), but its effectiveness in dealing with extreme rainfall events (with a 100-year return period) is limited (Supplementary Fig. 2). Meanwhile, the gray infrastructure in medium and low-income cities is still insufficient to handle regular heavy rainfall (with a 10-year return period). This is primarily because the drainage design standards for the gray infrastructure in most high-income cities typically exceed those for regular heavy rainfall with a 10-year return period but fall short of those for extreme rainfall with a 100-year return period. Conversely, the drainage design standards for the gray infrastructure in medium- and low-income cities do not even meet the 10-year return period criterion. When the precipitation is lower than the maximum drainage capacity of the gray infrastructure (design standard), as the precipitation increases, the drainage volume of the gray infrastructure also increases, and the drainage is mainly completed by the gray infrastructure. Once precipitation exceeds this capacity, the gray infrastructure reaches saturation, and further increases in precipitation do not lead to additional drainage. Consequently, as precipitation continues to rise, the proportion of total precipitation discharged by gray infrastructure steadily decreases (Fig. 6). Therefore, the differences in gray infrastructure performance, driven by varying economic levels, are more pronounced in response to regular heavy rainfall. In contrast, during extreme rainfall events, the disparity in coping capabilities between countries with different levels of economic development is less pronounced. Our study also confirms that increasing green space is the most effective strategy for mitigating inundation caused by extreme rainfall events, with its role becoming increasingly important as precipitation intensity increases. As shown in Fig. 6, once the drainage capacity of gray infrastructure reaches saturation, the excess precipitation is discharged by green infrastructure, such as green spaces. Before the infiltration capacity of green spaces reaches saturation, the proportion of precipitation discharged by green spaces to the total precipitation keeps increasing as the precipitation volume grows. Therefore, when the precipitation exceeds the maximum drainage capacity of gray infrastructure, the marginal benefit of increasing the proportion of green spaces becomes more pronounced as the precipitation intensity increases. After both gray and green infrastructure reach saturation, cities with greater topographic relief can naturally divert rainwater to low-lying areas, reducing inundation extent in higher-elevation areas and effectively decreasing the total inundation ratio. Consequently, when extreme precipitation exceeds the combined drainage capacity of gray and green infrastructure, the contribution of topographic relief to drainage capacity becomes more apparent.

Compared with existing studies, our research examines the role of economic development levels in mitigating urban flood risk caused by extreme precipitation by analyzing the combined effects of gray infrastructure, green infrastructure, and topography on reducing the severity of urban flooding. This study reveals that under intensifying extreme precipitation scenarios, the high-capacity gray infrastructure drainage systems characteristic of high-income countries are gradually losing their dominant role in alleviating urban flooding, exhibiting markedly diminishing marginal effects. This implies that climate change-induced extreme rainfall has become a shared disaster risk for nations across all economic development levels50,51. Although urban flooding occurs in specific cities or nations, addressing the risks posed by climate-driven extreme rainfall must be a global collective responsibility7,8. It is important to note that many capitals in low- and middle-income countries have long faced inadequate infrastructure and geographical disadvantages due to settlement patterns established during the colonial era, which prioritized political and trade considerations over ecological and indigenous living patterns. Nature-based solutions, such as rationally utilizing topography and enhancing green spaces, although their effect on enhancing the flood resilience of existing cities is relatively limited, can still be regarded as a viable pathway for these countries to strengthen their risk resistance capacity against urban flooding in future urban upgrades. This is particularly crucial for low- and middle-income countries with weak economic capabilities but ongoing acceleration of urbanization, continuous expansion, and new construction of cities. Small towns and communities, often constrained by limited investment in gray infrastructure, may achieve greater efficiency and resilience through green infrastructure applications52. This represents a critical area for future research.

This research comprehensively takes into account multiple aspects and discloses the mechanism through which gray infrastructure, green infrastructure, and topography collaboratively influence urban flooding under various levels of economic development, providing insights for urban planning and advancement. Given that our study is conducted globally, the selected indicators encompass macro-scale urban metrics such as drainage network density, green space ratio, and topographic relief. Regarding data selection, raw data with relatively large spatial statistical units are employed, for instance, the land use data of the European Space Agency (ESA) CCI Land Cover with a spatial resolution of 300 m. Such selection of macro-scale indicators and data is conducive to a more intuitive comparison of the disparities among different cities. Nevertheless, this leads to the exclusion of some micro-scale indicators within cities from the analysis process of this study, such as the shape and connectivity of green spaces, the fragmentation of topography, and small-scale green infrastructure (smaller than the spatial resolution of 300 m). These micro-level indicators indeed influence the urban flooding situation in specific areas, introducing a degree of uncertainty into our calculation results. However, this uncertainty primarily affects localized regions and has a limited impact on the overall urban inundation ratio53,54. In other words, this uncertainty does not alter the overall trend of the urban inundation ratio as observed in this study. To further eliminate such uncertainty, in future studies, research indicators can be further refined, and a combination of multiple methods such as numerical simulation and field observation can be adopted to enhance the analysis of the more detailed interaction among topography, green spaces, and floods at the micro-scale13, thereby further proposing and refining the optimal flooding mitigation strategies suitable for the internal structural characteristics of cities at different levels of economic development15.

Methods

Data

The precipitation data were obtained from Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation (MSWEP). It is a near-real-time global coverage rainfall product that provides a maximum time resolution of 3 h and a spatial resolution of 0.1° grid rainfall dataset, with a time series from 1979 to the present. The MSWEP dataset takes advantage of the complementary strengths of measurement-, satellite-, and reanalysis-based data to provide a reliable estimation of precipitation on a global scale. Due to the necessity of laying drainage networks alongside roads, there is a high degree of correlation between the road network and the drainage network55,56,57,58,59. Therefore, the distribution of drainage networks was derived from GRIP4 Global Road Data. GRIP4 Global Road Data is a global road dataset that collects nearly 60 geospatial data sets on road infrastructure from government agencies, research institutions, non-governmental organizations, and public resources, covering 222 countries and over 21 million kilometers of roads. However, in some underdeveloped regions, due to limited economic levels, the construction of drainage networks under some road networks is not complete60. Therefore, we refer to previous related studies and adjust the ratio between the road network and the drainage network according to the economic level of the city, as shown in Supplementary Table 258,59. Green space distribution data was extracted from land use data. The ESA CCI Land Cover is a land use dataset produced by the ESA with a spatial resolution of 300 m, which includes 22 primary land cover classes and 15 additional sub-classes. The product has high global consistency. The topographic relief data was extracted from the Global Multi-resolution Terrain Elevation Data 2010, a global digital elevation model (DEM) jointly produced by the US Geological Survey and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency of the United States. More relevant information regarding the data can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Calculation of precipitation intensity under different exceedance probabilities

In the field of probability theory and statistics, the Gumbel distribution is widely used to model the distribution of the maximum (or minimum) values of samples in various distributions60. Its applicability to the distribution of maximum values is rooted in its close connection with extreme value theory. Extreme value theory reveals that the Gumbel distribution is particularly applicable when the underlying sample data follow a normal or exponential distribution61,62. Given that extreme precipitation events in meteorology are typically low-frequency and have substantial impacts, the Gumbel distribution can accurately fit the distribution characteristics of such events, thus becoming an important tool for simulating and predicting extreme rainfall intensities62. Consequently, we collected annual maximum daily rainfall data for 138 capital cities from 1979 to 2022 and applied the Gumbel distribution fitting. Utilizing the fitted distribution function, we computed the rainfall intensity for specific return periods (e.g., 10-year and 100-year return periods).

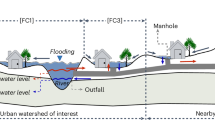

Inundation scenarios simulation

After obtaining the rainfall intensity, we conducted inundation scenario simulations by comparing volumes63,64. Initially, catchment units were extracted through a combination of DEM data and hydrological analysis. Subsequently, weighted average runoff coefficients for each catchment unit were derived using zonal statistics based on the corresponding runoff coefficients for different land use types. These average runoff coefficients were then combined with precipitation data to analyze the runoff volume for each catchment unit, serving as input data for extracting the inundation area in the subsequent step. Finally, we calculated the water volume collected in each catchment unit by multiplying its area by the respective runoff volume. By calculating and comparing the grid areas of catchment units, we obtained the inundation height, which is the area above the ground level that is potentially flooded.

Analysis of impact factor contributions

Compared with traditional machine learning algorithms such as Random Forest and Decision Tree, XGBoost leverages gradient boosting technology and incorporates regularization terms to iteratively correct prediction errors and effectively mitigate overfitting65,66. Consequently, XGBoost maintains high predictive accuracy while demonstrating robustness and strong generalization capabilities67,68. Therefore, we chose XGBoost to analyze the contributions of drainage network density, green space ratio, and topographic relief to the inundation rate. In the model construction phase, we utilized the xgb.XGBRegressor from the XGBoost library in Python to build the regression model. Specifically, 75% of the dataset was allocated for training, while the remaining 25% served as test data. Given that our data exhibit nonlinear characteristics and complex latent patterns, a tree-based gradient boosting model is better suited to capture these features compared to linear models. This model gradually fits the complex relationships in the data by iteratively constructing multiple decision trees, thereby enhancing adaptability to data diversity and complexity. After extensive experimentation and validation, we optimized the model parameters to ensure both accuracy and computational efficiency, while preserving generalization ability. The number of estimators (n_estimators) was set to 100 to adequately fit the data and capture its intricate features. The maximum depth (max_depth) was set to 6 to balance capturing complex patterns and avoiding overfitting. The learning rate (learning_rate) was set to 0.3 to control the contribution of each tree’s predictions to the final output, ensuring stable learning. Following model training, we used the feature importance attribute to quantify the importance of each feature, thereby elucidating the relative contributions of drainage network density, green space ratio, and topographic relief to the inundation rate.

Data availability

Precipitation data are obtained from Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation (MSWEP) in http://www.gloh2o.org. Drainage network data are obtained from GRIP4 Global Road Data in https://www.globio.info. DEM data are obtained from the Global Multi-resolution Terrain Elevation Data 2010 in https://www.usgs.gov/coastal-changes-and-impacts/gmted2010. Land use data are obtained from the ESA CCI Land Cover at https://essd.copernicus.org.

Code availability

All codes used to analyze and plot the data are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Bevacqua, E. et al. Higher probability of compound flooding from precipitation and storm surge in Europe under anthropogenic climate change. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw5531 (2019).

Merz, B. et al. Causes, impacts and patterns of disastrous river floods. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 592–609 (2021).

Dottori, F. et al. Increased human and economic losses from river flooding with anthropogenic warming. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 781–786 (2018).

Rentschler, J. et al. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 622, 87–92 (2023).

Jiang, R. et al. Substantial increase in future fluvial flood risk projected in China’s major urban agglomerations. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 389 (2023).

Boulange, J., Hanasaki, N., Yamazaki, D. & Pokhrel, Y. Role of dams in reducing global flood exposure under climate change. Nat. Commun. 12, 417 (2021).

Ajjur, S. B. & Al-Ghamdi, S. G. Exploring urban growth-climate change-flood risk nexus in fast growing cities. Sci. Rep. 12, 12265 (2022).

Ward, P. J. et al. A global framework for future costs and benefits of river-flood protection in urban areas. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 642–646 (2017).

Yan, L., Rong, H., Yang, W., Lin, J. & Zheng, C. A novel integrated urban flood risk assessment approach based on one-two dimensional coupled hydrodynamic model and improved projection pursuit method. J. Environ. Manag. 366, 121910 (2024).

Dharmarathne, G., Waduge, A. O., Bogahawaththa, M., Rathnayake, U. & Meddage, D. P. P. Adapting cities to the surge: a comprehensive review of climate-induced urban flooding. Results Eng. 22, 102123 (2024).

Dottori, F., Mentaschi, L., Bianchi, A., Alfieri, L. & Feyen, L. Cost-effective adaptation strategies to rising river flood risk in Europe. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 196–202 (2023).

Xiong, L., Lu, S. & Tan, J. Optimized strategies of green and grey infrastructures for integrated control objectives of runoff, waterlogging and WWDP in old storm drainages. Sci. Total Environ. 901, 165847 (2023).

Khoshkonesh, A., Nazari, R., Nikoo, M. R. & Karimi, M. Enhancing flood risk assessment in urban areas by integrating hydrodynamic models and machine learning techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 952, 175859 (2024).

Kelleher, C. & McPhillips, L. Exploring the application of topographic indices in urban areas as indicators of pluvial flooding locations. Hydrol. Process. 34, 780–794 (2020).

Kaushal, A., Nazari, R. & Karimi, M. Study of elevation role in representing sociodemographic status and susceptibility to flooding in Birmingham, Alabama. Nat. Hazards Rev. 25, 04024029 (2024).

Huang, H., Chen, X., Wang, X., Wang, X. & Liu, L. A depression-based index to represent topographic control in urban pluvial flooding. Water 11, 2115 (2019).

Komori, D. et al. Topographical characteristics of frequent urban pluvial flooding areas in Osaka and Nagoya cities, Japan. Water 14, 2795 (2022).

Dong, X., Guo, H. & Zeng, S. Enhancing future resilience in urban drainage system: green versus grey infrastructure. Water Res. 124, 280–289 (2017).

Chapman, C. & Hall, J. W. Designing green infrastructure and sustainable drainage systems in urban development to achieve multiple ecosystem benefits. Sust. Cities Soc. 85, 104078 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. The capacity of grey infrastructure in urban flood management: a comprehensive analysis of grey infrastructure and the green-grey approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 54, 102045 (2021).

Tansar, H., Duan, H.-F. & Mark, O. A multi-objective decision-making framework for implementing green-grey infrastructures to enhance urban drainage system resilience. J. Hydrol. 620, 129381 (2023).

Tian, Z. et al. Dynamic adaptive engineering pathways for mitigating flood risks in Shanghai with regret theory. Nat. Water 1, 198–208 (2023).

Moon, H.-T., Kim, J.-S., Chen, J., Yoon, S.-K. & Moon, Y.-I. Mitigating urban flood Hazards: hybrid strategy of structural measures. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 108, 104542 (2024).

Chen, Z. & Huang, G. Numerical simulation study on the effect of underground drainage pipe network in typical urban flood. J. Hydrol. 638, 131481 (2024).

Korkou, M., Tarigan, A. K. M. & Hanslin, H. M. The multifunctionality concept in urban green infrastructure planning: a systematic literature review. Urban For. Urban Green. 85, 127975 (2023).

Grabowski, Z. J., McPhearson, T., Matsler, A. M., Groffman, P. & Pickett, S. T. A. What is green infrastructure? A study of definitions in US city planning. Front. Ecol. Environ. 20, 152–160 (2022).

Valente de Macedo, L. S., Picavet, M. E. B., Puppim de Oliveira, J. A. & Shih, W.-Y. Urban green and blue infrastructure: a critical analysis of research on developing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 313, 127898 (2021).

Ambily, P., Chithra, N. R. & Firoz, C. M. A framework for urban pluvial flood resilient spatial planning through blue-green infrastructure. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 103, 104342 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Mechanisms and applications of green infrastructure practices for stormwater control: a review. J. Hydrol. 568, 626–637 (2019).

Wang, M. et al. Assessing and optimizing the hydrological performance of Grey-Green infrastructure systems in response to climate change and non-stationary time series. Water Res. 232, 119720 (2023).

Rentschler, J., Salhab, M. & Jafino, B. A. Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries. Nat. Commun. 13, 3527 (2022).

Aerts, J. C. J. H. et al. Exploring the limits and gaps of flood adaptation. Nat. Water 2, 719–728 (2024).

Sorensen, J. et al. Re-thinking urban flood management-time for a regime shift. Water 8, 332 (2016).

Winsemius, H. C. et al. Global drivers of future river flood risk. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 381–385 (2016).

Pielke, R. Tracking progress on the economic costs of disasters under the indicators of the sustainable development goals. Environ. Hazards 18, 1–6 (2019).

Staccione, A., Essenfelder, A. H., Bagli, S. & Mysiak, J. Connected urban green spaces for pluvial flood risk reduction in the Metropolitan area of Milan. Sust. Cities Soc. 104, 105288 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. A novel framework for urban flood risk assessment: multiple perspectives and causal analysis. Water Res. 256, 121591 (2024).

Wright, D. B., Bosma, C. D. & Lopez-Cantu, T. US hydrologic design standards insufficient due to large increases in frequency of rainfall extremes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 8144–8153 (2019).

Zhou, Q., Mikkelsen, P. S., Halsnaes, K. & Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K. Framework for economic pluvial flood risk assessment considering climate change effects and adaptation benefits. J. Hydrol. 414, 539–549 (2012).

Tang, Z. et al. Contributions of climate change and urbanization to urban flood hazard changes in China’s 293 major cities since 1980. J. Environ. Manag. 353, 120113 (2024).

Zou, A., Yang, Y., Wang, H., Wang, P. & Liao, H. Aerosol decline accelerates the increasing extreme precipitation in China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL113887 (2025).

EM-DAT (Emergency events database). The OFDA/CRED international disaster database. Retrieved from http://www.cred.be/emdat (2024).

CarbonBrief. Attributing extreme weather to climate change. Retrieved from https://www.carbonbrief.org/mapped-how-climate-change-affects-extreme-weather-around-the-world (2024).

Madsen, H., Lawrence, D., Lang, M., Martinkova, M. & Kjeldsen, T. R. Review of trend analysis and climate change projections of extreme precipitation and floods in Europe. J. Hydrol. 519, 3634–3650 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. Climate change impacts on magnitude and frequency of urban floods under scenario and model uncertainties. J. Environ. Manag. 366, 121679 (2024).

Seyedashraf, O., Bottacin-Busolin, A. & Harou, J. J. Assisting decision-makers select multi-dimensionally efficient infrastructure designs—application to urban drainage systems. J. Environ. Manag. 336, 117689 (2023).

Ruangpan, L. et al. Economic assessment of nature-based solutions to reduce flood risk and enhance co-benefits. J. Environ. Manag. 352, 119985 (2024).

Islam, M. T. & Meng, Q. Spatial analysis of socio-economic and demographic factors influencing urban flood vulnerability. J. Urban Manag. 13, 437–455 (2024).

Devitt, L., Neal, J., Coxon, G., Savage, J. & Wagener, T. Flood hazard potential reveals global floodplain settlement patterns. Nat. Commun. 14, 2801 (2023).

Yin, J., Ye, M., Yin, Z. & Xu, S. A review of advances in urban flood risk analysis over China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 29, 1063–1070 (2015).

Miller, J. D. & Hutchins, M. The impacts of urbanisation and climate change on urban flooding and urban water quality: a review of the evidence concerning the United Kingdom. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 12, 345–362 (2017).

Nazari, R., Karimi, M., Nikoo, M. R., Khoshkonesh, A. & Museru, M. L. Can small towns survive climate change? Assessing economic resilience and vulnerability amid major storms. J. Clean. Prod. 498, 145158 (2025).

Ernst, J. et al. Micro-scale flood risk analysis based on detailed 2D hydraulic modelling and high resolution geographic data. Nat. Hazards 55, 181–209 (2010).

Zhang, S. & Pan, B. An urban storm-inundation simulation method based on GIS. J. Hydrol. 517, 260–268 (2014).

Blumensaat, F., Wolfram, M. & Krebs, P. Sewer model development under minimum data requirements. Environ. Earth Sci. 65, 1427–1437 (2012).

Goldshleger, N., Karnibad, L., Shoshany, M. & Asaf, L. Generalising urban runoff and street network density relationship: a hydrological and remote-sensing case study in Israel. Urban Water J. 9, 189–197 (2012).

Liu, C., Duan, D. & Zhang, H. Relationships between fractal road and drainage networks in Wuling mountainous area: another symmetric understanding of human-environment relations. J. Mt. Sci. 11, 1060–1069 (2014).

Mair, M., Zischg, J., Rauch, W. & Sitzenfrei, R. Where to find water pipes and sewers? On the correlation of infrastructure networks in the urban environment. Water 9, 146 (2017).

Montalvo, C., Reyes-Silva, J. D., Sanudo, E., Cea, L. & Puertas, J. Urban pluvial flood modelling in the absence of sewer drainage network data: a physics-based approach. J. Hydrol. 634, 131043 (2024).

Dibaba, W. T. A review of sustainability of urban drainage system: traits and consequences. J. Sediment. Environ. 3, 131–137 (2018).

Gumbel, E. J. The return period of flood flows. Ann. Stat. 12, 163–190 (1941).

Osei, M. A. et al. Estimation of the return periods of maxima rainfall and floods at the Pra River Catchment, Ghana, West Africa using the Gumbel extreme value theory. Heliyon 7, e06980 (2021).

Li, X. et al. High efficiency integrated urban flood inundation simulation based on the urban hydrologic unit. J. Hydrol. 630, 130724 (2024).

Ming, X., Liang, Q., Xia, X., Li, D. & Fowler, H. J. Real-time flood forecasting based on a high-performance 2-d hydrodynamic model and numerical weather predictions. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR025583 (2020).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. KDD’16: 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2016).

Gong, J., Chu, S., Mehta, R. K. & McGaughey, A. J. H. XGBoost model for electrocaloric temperature change prediction in ceramics. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 140 (2022).

Niazkar, M. et al. Applications of XGBoost in water resources engineering: a systematic literature review. Environ. Model. Softw. 174, 105971 (2024).

Qin, L. et al. Global expansion of tropical cyclone precipitation footprint. Nat. Commun. 15, 4824 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42230510, J.F. and 72394403, B.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.F., B.L., and T.L. designed the study. Y.S. and T.L. compiled the data. B.L. and Y.S. conducted the calculations. J.F., B.L., Y.S., and Y.M. analyzed the results. Y.S., K.Z., S.L., X.G., and R.G. created the figures. B.L. and T.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. J.F., B.L., T.L., Y.M., and D.C. reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Emily O’Donnell and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, J., Liu, B., Lei, T. et al. Exploring how economic level drives urban flood risk. Nat Commun 16, 4857 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60267-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60267-6

This article is cited by

-

Quantitative estimation of urban flood damage from storm surges for a coastal city

Natural Hazards (2025)