Abstract

In ascomycetes, perithecium development involves sexual differentiation processes regulated by mating-related signaling pathways and mating-type locus (MAT) transcription factors, activated by uncharacterized receptors in response to stage-specific signaling cues. Here, we show that a non-pheromone receptor, Gip1, regulates two distinct sexual differentiation processes during perithecial development in the wheat scab fungus Fusarium graminearum. Gip1 controls the formation of perithecium initials via the cAMP-PKA pathway, and regulates subsequent development, including the differentiation of peridia and ascogenous tissues, via the Gpmk1 MAPK pathway. The C-terminal tail of Gip1 is important for intracellular signaling, while its N-terminal region and extracellular loop 3 are key for ligand recognition. Interestingly, all sexual-specific spontaneous suppressors of gip1 had mutations in the FgVeA gene, encoding a component of the Velvet complex, which regulates sexual reproduction in filamentous ascomycetes. These mutations partially rescue defects in either perithecium initiation or maturation in gip1 mutants, and restore upregulation of genes important for perithecium development such as MAT1-1-2 (encoding a MAT transcription factor). Thus, Gip1 controls two early stages of sexual differentiation by activating downstream cAMP signaling and Gpmk1 pathways, which may coordinately regulate the expression of genes important for initial perithecium development via FgVeA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The sexual life cycle initiates with pheromone-based recognition among compatible partners that differ at the mating-type locus in unicellular yeasts1. In two well-studied ascomycetous yeasts, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, mating is elicited by a pheromone signal. Cell-specific peptide pheromones released are recognized by G protein-coupled receptors specifically expressed in cells of the opposite mating type2. The binding between pheromone and receptor triggers a G protein-mediated signal transmission that involves a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade, resulting in cell cycle arrest in G1 and the activation of genes required for cell and nuclear fusion3. Unlike yeast, filamentous ascomycetes possess the ability to develop more complex fruiting bodies such as perithecia. In the life cycle of most fungi that form perithecia, the perithecial morphogenesis is not governed by pheromone receptors4,5. However, the exact receptor responsible for orchestrating this intricate process has yet to be identified.

Fusarium graminearum, a homothallic perithecium-producing ascomycete, is the major causal agent of wheat Fusarium head blight disease worldwide6,7. This fungal pathogen also infects barley, oats, corn, and other grain crops. In addition to causing significant yield losses, F. graminearum is a producer of harmful mycotoxins such as deoxynivalenol and zearalenone8,9. In the field, perithecia emerge on the surface of host plants and residual crop matter that are colonized by F. graminearum10. The process begins with the emergence of dikaryotic hyphae within the central cavity of a wheat plant infected by the pathogen. These dikaryotic hyphae progress within the plant’s chlorenchyma and substomatal spaces, culminating in the formation of initial structures for perithecia. Following the formation of the perithecium initials (PIs), a period of dormancy may ensue. Upon reactivation in the spring, the PIs gradually progress into young perithecia, subsequently advancing into mature perithecia, culminating in the uninterrupted release of ascospores10. Under favorable environmental conditions, ascospores (sexual spores) are physically discharged from perithecia. Because airborne ascospores are the primary inoculum for infecting floral tissues, sexual reproduction is a critical step in the infection cycle of F. graminearum. In F. graminearum, all three MAP kinase (MAPK) deletion mutants (Gpmk1, Mgv1, and FgHog1) failed to develop perithecia11. Moreover, the cAMP-PKA pathway plays a critical role in regulating perithecia formation and the growth of ascogenous tissues12,13. Despite the importance of the cAMP-PKA signaling and MAPK pathways in the formation and development of perithecia, it is crucial to identify the receptors upstream of these pathways. The absence of pre1 and pre2 (pheromone receptors) as well as ppg1 and ppg2 (pheromone precursors) in F. graminearum leads to reduced fertility in mutants, although they still demonstrate the ability to produce perithecia and ascospores14,15. This suggests that in F. graminearum, pheromone precursor and receptor genes are not essential for the initiation and maturation of perithecia. Notably, the deletion of GIA1, a non-pheromone GPCR, results in the formation of normal perithecia but lacks the capacity to undergo meiosis in F. graminearum16. While the pheromone receptors and Gia1 play crucial roles in cell recognition and meiosis, the specific receptor responsible for regulating the differentiation and development of perithecia remains unknown.

A systematic analysis of all 105 predicted GPCR genes in F. graminearum revealed that Gip1, a non-pheromone GPCR, is the only one required for perithecium formation17. However, the mechanism of action of Gip1, its downstream signaling pathways, and potential ligands remain unclear. In this study, we have found that Gip1 regulates the initiation and further development of perithecia in F. graminearum. While the regulation of Gip1 on PI formation relies on the cAMP-PKA pathway, the development of perithecia and the differentiation of peridia and ascogenous tissues are dependent on Gpmk1-mediated signaling. Furthermore, suppressor mutations in FgVeA partially relieved the sexual defects observed in the gip1 mutant. The spontaneous suppressor S1 only led to the formation of PIs, whereas most of the other spontaneous suppressors produced mature perithecia containing asci and ascospores. Taken together, these findings indicate that Gip1 operates upstream from various signaling pathways and collaborates with FgVeA to regulate the two-stage process of perithecial morphogenesis in F. graminearum.

Results

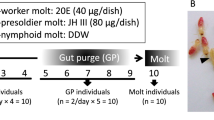

GIP1 is essential for peridium development and differentiation of ascogenous tissues

Although the gip1 mutant was blocked in perithecium formation on carrot agar (CA) mating plates (Fig. 1a), small, black perithecium-like structures that lacked ascogenous tissues were occasionally formed on some desiccated areas (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting a suppressive effect of environmental stress. Since F. graminearum commonly produces abundant perithecia on plant debris in the field, we conducted tests on autoclaved wheat straws to observe perithecium formation. Whereas fertile perithecia were formed by the wild type on wheat straws, the gip1 mutant only formed small, sterile perithecium-like structures (Fig. 1a). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) examinations showed that the gip1 mutant was normal in the formation of hyphal curling and PIs (Fig. 1b). However, unlike the wild type that formed mature perithecia with the typical peridium layer consisting of highly differentiated fungal cells, the gip1 mutant failed to develop the peridium layer and had only limited enlargement of developing fruiting bodies. At 7 days post-fertilization (dpf) or longer, the fruiting bodies formed by the gip1 mutant exhibited considerably reduced size compared to the normal perithecia, had a hairy appearance due to hyphal growth on the surface (Fig. 1b, c), and lacked ascogenous tissues and ostioles (Fig. 1d).

a Mating cultures of the wild type (WT) and gip1 mutant were examined for perithecium formation on carrot agar (CA) mating plates and wheat straws (WS) at 7 days post-fertilization (dpf). Bar = 0.5 mm. b SEM examination of fruiting bodies formed by the WT and gip1 mutant on wheat straws at the marked time points. Bar = 20 μm. c A close-up examination of sexual fruiting bodies formed by the WT, gip1 mutant, and mat1-1-1 mutant on wheat straws at 7-dpf. Bar = 20 μm. d Thick sections of sexual fruiting bodies formed by the same set of strains. P peridium, A ascogenous tissue. Bar = 20 μm. e The cross between the gip1 mutant (female) and the H1-GFP transformant of the wild type (male) resulted in fertile perithecia (Per) and asci containing 8 ascospores. Epifluorescence microscopical examination of 100 fertile perithecia showed the 1:1 segregation of H1-GFP signals in the nucleus. Bar = 0.5 mm for examination of perithecia, and bar = 20 μm for asci/ascospores. For a–e, similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Because the mat1-1-1 mutant also formed small, sterile perithecia on CA mating plates18, we then compared its defects with the gip1 mutant on wheat straws. Fruiting bodies formed by mat1-1-1 on wheat straws were small and lacked asci with ascospores but had the peridium and limited ascogenous tissues, which were not observed in the gip1 mutant (Fig. 1c, d). In outcrosses between the gip1 mutant (as the female) and a transformant of the wild-type strain PH-1 expressing H1-GFP (Supplementary Table 1), eight ascospores per ascus exhibiting a 1:1 segregation of GFP signals were observed in 100 analyzed fertile perithecia (Fig. 1e). These results indicate that GIP1 is not essential for female fertility but it regulates earlier sexual developmental processes than MAT1-1-1.

GIP1 functions upstream from the cAMP-PKA pathway to regulate the formation of PIs

GPCRs typically activate intracellular signaling pathways upon sensing signals. In F. graminearum, there are three MAPK signaling pathways, all of which are related to sexual reproduction. A MAPK cascade generally consists of MEKK, MEK, and MAPK19. Dominant active mutations in the MEKs can affect the phosphorylation of downstream MAPKs, thereby activating the related MAPK pathways. FST7, FgMKK2, and FgPBS2 serve as MEKs in the Gpmk1, CWI, and HOG MAPK pathways, respectively. To demonstrate that a MAPK functions downstream of upstream receptors, a common approach is to introduce dominant active MEKs into receptor mutants and observe whether the phenotypic defects are rescued16, because of the suppressive effect of desiccation and wheat straws, we introduced the FgPBS2DA and FgMKK2DA alleles16 into the gip1 mutant to determine the effects of hyperactivation of these two MEKs known to regulate stress responses. The resulting gip1 FgPBS2DA and gip1 FgMKK2 DA transformants (Supplementary Table 1) were increased in the phosphorylation of FgHog1 and Mgv1, respectively (Fig. 2a). On CA mating plates, the gip1 FgMKK2DA transformant, similar to the gip1 FST7 DA transformant16, failed to form perithecia (Fig. 2b). However, PIs were often observed on mating cultures of the gip1 FgPBS2DA transformant (Fig. 2b).

a MAPK phosphorylation assays of the wild type (WT) and indicated mutants. Western blots of proteins isolated from vegetative hyphae were detected with the anti-TpGY (P-p38), anti-TpEY (P-p44/42), anti-FgHog1, anti-Mgv1, anti-Gpmk1, and anti-Tubulin2 (Tub2) antibodies. The blots are representative of two independent biological repeats. Phosphorylation levels were quantified using ImageJ and normalized to the endogenous protein expression. b Mating cultures of the marked strains were examined for the formation of perithecia/PIs on carrot agar (CA) mating plates at 7-dpf. Bar = 0.5 mm. c Intracellular cAMP levels from vegetative hyphae of the gip1 mutant and gip1 FgPBS2DA transformant. Mean and SD were calculated with data from three independent repeats (n = 3). The P-value was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test and presented above the bar. d SEM (upper panels) and thick section (lower panels) observation of perithecia or PIs formed by the indicated strains on CA mating plates at 7-dpf. Bar = 20 μm. e Perithecia/PIs (upper panels, bar = 0.5 mm) formed by the indicated strains on wheat straws were examined for asci and ascospores (lower panels, bar = 50 μm). For the gip1 FST7DA transformant, only enlarged perithecia (marked with arrows) contained asci and ascospores. f Cultures of the WT, gip1 mutant, gip1 pde1 double mutant, and gip1 pde1 FST7DA transformant were examined for colony growth on PDA after 3 days. g Mating cultures of the WT, gip1 mutant, gip1 pde1 double mutant, and gip1 pde1 FST7DA transformant were examined for perithecia/PIs (upper panels, bar = 0.5 mm) and asci/ascospores development (lower panels, bar = 50 μm) on CA plates at 7-dpf. For a, d, e, and g, similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. Source data of a and c, are provided as a Source Data file.

Because GIP1 encodes a GPCR but GPCRs are not involved in the activation of the HOG pathway in S. cerevisiae and other ascomycetes20, the partial suppressive effect of FgPBS2DA may be due to its crosstalk with other signaling pathways, such as the cAMP-PKA pathway that is also important for sexual reproduction in F. graminearum12. In comparison with the gip1 mutant, the intracellular cAMP level was increased by 78.4% in the gip1 FgPBS2DA transformant (Fig. 2c). PDE1 and PDE2 encode two phosphodiesterases (PDEs) in F. graminearum that are involved in hydrolyzation of cAMP13, and PDE1 has higher expression levels than PDE2 during sexual reproduction stage21. We then generated the gip1 pde1 double mutant (Supplementary Table 1) by deleting the PDE1 gene in the gip1 mutant. On CA mating plates, the gip1 pde1 double mutant, similar to the gip1 FgPBS2DA transformant, produced abundant PIs (Fig. 2b) that lacked peridium and ascogenous tissues (Fig. 2d). These results indicate that cAMP signaling is one of the downstream signaling pathways of GIP1 and hyperactivation of FgHog1 may result in cross-talking with the cAMP-PKA pathway. Deletion of PDE1 could partially suppress the defect of gip1 in the formation of PIs but failed to bypass the requirement of GIP1 for the post-PI development.

Expression of FST7 DA partially rescues the defect of gip1 in the post-PI development

On wheat straws, the gip1 pde1, gip1 FgPBS2DA, and gip1 FgMKK2DA strains, similar to the gip1 mutant, formed PIs without the peridium and ascogenous tissues (Fig. 2e). However, although majority of perithecia formed by the gip1 FST7 DA transformant were small and sterile, some of them (<5%) were normal in size and contained asci and ascospores (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2). These results indicated that wheat straws may contain some compounds that are stimulatory to the initiation of perithecium development by bypassing the requirement of Gip1. Following the formation of PIs on wheat straws, the dominant active mutation in FST7 could partially rescue the defect of the gip1 mutant in the subsequent development of PIs, including peridium formation, differentiation of ascogenous tissues, and ascospore formation.

GIP1 functions upstream from the cAMP signaling and Gpmk1 MAPK pathways for regulating different sexual developmental processes

Because results from experiments described above indicate that GIP1 may function upstream from cAMP signaling for the formation of PIs but acts via the Gpmk1 pathway for further development of perithecia, we then transformed FST7 DA into the gip1 pde1 mutant. The resulting gip1 pde1 FST7 DA transformant (Supplementary Table 1) was normal in growth rate and colony morphology (Fig. 2f). On CA mating plates, the gip1 pde1 FST7 DA transformant occasionally (less than 5%) developed fertile perithecia with asci and ascospores (Fig. 2g), which is similar to the gip1 FST7 DA transformant on wheat straws. These results indicate that while overstimulating cAMP signaling can restore the formation of PIs in the gip1 mutant, the subsequent development of perithecia requires the hyperactivation of the Gpmk1 MAPK pathway.

The C-terminal tail of Gip1 is important for activating intracellular signaling associated with perithecium formation

GIA1 is a paralog of GIP1 that regulates ascosporogenesis via the Gpmk1 pathway in F. graminearum and other Sordariomycetes species16. Because of the importance of the C-terminal tail (CT) and intracellular ring 3 (IR3) regions of GPCRs in intracellular signaling, we generated the GIP1CTp and GIP1IR3p chimeric alleles with the CT and IR3 regions of GIP1 replaced with corresponding regions of GIA1 (Fig. 3a) and transformed them into the gip1 mutant. While the GIP1IR3p transformants exhibited normal perithecium formation, the GIP1CTp transformants were unable to form perithecia, despite the normal expression of the GIP1CTp protein (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 3a). These results indicated that IR3 is dispensable but the carboxyl-terminal cytoplasmic region of Gip1 is essential for its function in intracellular signaling.

a Diagrams of GIP1, GIA1 (a GIP1 paralog), and labeled chimeric alleles. NT, N-terminal region; CT, C-terminal region; EL1-EL3, extracellular loops 1-3; IR1-IR3, intracellular rings 1-3. Transmembrane regions (TM) are depicted as blue/green boxes. b Seven-day-old CA mating cultures of the wild type (WT), gip1 mutant, and transformants of gip1 expressing the labeled chimeric alleles. Bar = 0.5 mm. c The number of perithecia formed by the WT and transformants of gip1 expressing the labeled chimeric alleles at 7-dpf. Mean and SD were calculated with data from three independent repeats (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences based on one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple range test (P < 0.0001). The exact P-values are presented in the Source Data file. d The tertiary structure of Gip1 predicted by AlphaFold v2. Yellow, turquoise blue, green, and orange areas correspond to the NT, EL1, EL2, and EL3 regions, respectively. Two cysteine residues (C88 and C167) and the intramolecular disulfide bond they formed were highlighted. e Alignments of the EL1 and EL2 sequences of Gip1 homologs, with highly conserved cysteine residues indicated by red boxes. f Seven-day-old CA mating cultures of the WT, gip1 mutant, GIP1C88A and GIP1C167A transformants. Bar = 0.5 mm. For (b) and (f), similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Ligand recognition involves the N-terminal region and EL3 of Gip1

To determine which extracellular regions are responsible for ligand recognition, we generated the chimeric GIP1 alleles with its N-terminal region (GIP1NTp) or three extracellular loops (GIP1EL1p, GIP1EL2p, and GIP1EL3p) regions replaced with corresponding regions of GIA1 and transformed them into the gip1 mutant (Fig. 3a). The GIP1EL1p and GIP1EL2p transformants exhibited normal perithecium formation (Fig. 3b, c), whereas the GIP1NTp and GIP1EL3p transformants were defective in perithecium formation. Specifically, perithecia were not formed by the GIP1NTp transformants, and the GIP1EL3p transformants showed a significant reduction in perithecium formation compared to the wild type (Fig. 3b, c). The substitution of the N-terminal region and the third extracellular loop does not affect the protein stability of Gip1 (Supplementary Fig. 3b). In protein structures predicted with AlphaFold v222, the NT and EL3 regions of Gip1 are adjacent to each other, while the EL1 and EL2 regions are located on the other side of the tertiary structure (Fig. 3d). These results indicated that both NT and EL3 regions of Gip1 are involved in ligand recognition although NT plays a more critical role.

To identify potential ligands recognized by Gip1, we engineered a chimeric yeast STE2 CH allele. This construct incorporates the N-terminal extracellular region and three extracellular loops from Gip1 into the yeast Ste2 receptor (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Subsequently, we introduced this STE2 CH allele into a yeast strain that expresses the P FUS1-GFP construct, creating the reporter strain SP1. Upon treatment with crude extracts of perithecia, yeast cells of strain SP1 showed induced expression of the P FUS1-GFP reporter (Supplementary Fig. 4b), indicating activation of the yeast pheromone response pathway. The perithecial crude extracts treated with protease K for 1 h still induced the expression of the P FUS1-GFP reporter in yeast SP1 cells, but the GFP signal was weaker (Supplementary Fig. 4b). This suggests that unlike Gia1, which specifically recognizes proteinaceous ligands, Gip1 likely detects multiple ligands, both protein-based and non-protein-based, associated with different stages of perithecial morphogenesis.

Two conserved cysteine residues are important for the functions of Gip1

While the EL1 and EL2 of Gip1 can be substituted with the corresponding regions of Gia1 for ligand recognition, it is important to note that these two extracellular loops are positioned next to each other in the tertiary structure of Gip1 (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, two conserved cysteine residues identified in the EL1 and EL2 regions of Gip1 and Gia1 homologs across Sordariomycetes fungi are predicted to form an intramolecular disulfide bond (Fig. 3d, e). To elucidate the significance of these two cysteine residues, we generated the GIP1C88A and GIP1C167A alleles by site-directed mutagenesis. Subsequently, we introduced these two alleles separately into the gip1 mutant. The GIP1C88A and GIP1C167A proteins were successfully expressed and showed protein levels comparable to Gip1 (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The formation of perithecia was blocked in the resulting GIP1C88A and GIP1C167A transformants, indicating the indispensable role of these two cysteine residues in Gip1 function (Fig. 3f). It is likely that the intramolecular disulfide bond formed between C88 (in EL1) and C167 (in EL2) is important for the tertiary structure of Gip1 proteins.

GIP1 transcriptionally regulates a variety of genes involved in sexual development

To identify genes that are transcriptionally regulated by GIP1 during sexual development in F. graminearum, we conducted RNA-seq analysis with RNA isolated from fungal biomass collected from mating cultures at 3-dpf. Compared to the wild type, a total of 1043 genes were identified as differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with at least 2-fold changes in the gip1 mutant (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 1). For the 250 DEGs up-regulated in the gip1 mutant, GO enrichment analysis showed that they are enriched for genes involved in response to nitrosative stress, acyl-CoA metabolic process, fatty acid beta-oxidation, and fungal-type cell wall organization (Supplementary Fig. 5). The 793 DEGs down-regulated in the gip1 mutant were enriched for genes involved in RNA silencing, carbohydrate metabolic process, methylation, nucleoside metabolic process, and cellular amino acid catabolic process (Fig. 4b).

a A volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) on carrot agar (CA) plates at 3 days post-fertilization (dpf), identified using the UCexact Test with EdgeRun, is shown. Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 and log2 fold change > 1 are highlighted in orange (up-regulated) and blue (down-regulated). The P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method (FDR < 0.05). b Enriched gene ontology (GO) terms in genes with down-regulated genes in the gip1 mutant. GO enrichment analysis was performed using Fisher’s Exact Test, and P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method (FDR < 0.05). BP biological process, CC cell component, MF molecular function. c The expression patterns of GIP1 and seven representative down-regulated genes in vegetative hyphae (Hyp) and mating cultures (P1-P7, 1-7 dpf) based on our published RNA-seq data. FPKM, Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million fragments mapped. The FPKM value are provided in the Source Data file. d Mating cultures of the WT, gip1 mutant, and two specified gene deletion mutants were examined for perithecium/PI development on wheat straws at 7-dpf. Bar = 0.5 mm. e Thick sections of representative perithecia produced by the WT and three specified gene deletion mutants. The identified gene deletion mutants displayed a blockage in the development of ascogenous tissues. Bar = 50 μm. For (d) and (e), similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Among the DEGs down-regulated in the gip1 mutant, at least 18 of them (Supplementary Table 2), including FG2G04760 (cytochrome P450 monooxygenase), FG2G13000 (FgPKS7 polyketide synthase), FG2G39720 (GAL4-like transcription factor), FG3G23790 (alpha/beta hydrolase), and FG4G01590 (LrgB-like protein) are known to be important for the formation and/or development of perithecia on carrot medium23,24,25,26. All of these 5 genes had no or very low expression in hyphae but were specifically expressed or significantly up-regulated during sexual reproduction, showing expression patterns similar to that of Gip1 (Fig. 4c). To further characterize their roles in the formation and development of PIs, we generated mutants by deleting these five genes with the split-marker approach27. While the FG4G01590 and FG2G39720 deletion mutants were almost blocked in the formation of PIs on wheat straws (Fig. 4d), the FG2G04760, FG2G13000, and FG3G23790 deletion mutants formed smaller perithecia that lacked asci or ascospores, indicating a defect in the post-PI development (Fig. 4e). Therefore, the downregulation of these genes could be responsible for the defects observed in the gip1 mutant.

Spontaneous suppressor mutants of gip1 forming fertile perithecia on mating cultures

Interestingly, on mating plates of the gip1 mutant older than two weeks, clusters of fertile perithecia with asci and ascospores were occasionally observed (Fig. 5a), suggesting the occurrence of spontaneous suppressor mutations. The appearance of spontaneous suppressors is due to mutations occurring in the genome. Since the gip1 mutant is unable to produce perithecia on CA, mutations occurring in genes that have genetic interactions with GIP1 may give rise to spontaneous suppressors. In total, we isolated 10 spontaneous suppressor strains. To rule out contaminations, all of them were verified to be deleted of GIP1 by PCR analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). On PDA, these suppressor strains had reduced growth rate and abnormal colony morphology (Fig. 5b). On mating cultures, they all formed PIs or perithecia (Fig. 5c). Asci and ascospores were not observed at 7-dpf (Supplementary Fig. 7) but observed in all those suppressor strains except S1 at 14-dpf (Fig. 5c), suggesting a delay in ascus development and ascospore formation. Suppressor S1 formed darkly pigmented PIs that lacked ascogenous tissues and ostioles (Fig. 5d). Even after incubation for longer than 14-dpf, it failed to develop asci and ascospores, indicating that suppressor S1, unlike the other nine suppressor strains, is only partially rescued in the defect of gip1 in the initiation of perithecium formation. Therefore, the sexual development of suppressor S1 is halted at the PIs stage and fails to proceed to mature perithecia, whereas other suppressors are able to continue development beyond the PIs stage.

a CA mating cultures (upper panels, bar = 0.5 mm) of the gip1 mutant with or without clusters of perithecia (marked with arrow) that contained asci and ascospores (lower panels, bar = 50 μm). b Three-day-old PDA cultures of the wild type (WT), gip1 mutant, and ten spontaneous suppressor strains. c CA mating cultures of suppressor strains were examined for perithecium/PIs formation (upper panels, bar = 0.5 mm) and asci/ascospores (lower panels, bar = 50 μm) at 14-dpf. d SEM examination (upper panels) and thick sections (lower panels) of perithecia formed by the WT and PIs formed by suppressor S1 on CA plates at 7-dpf. Bar = 20 μm. e Flowering wheat heads drop-inoculated with conidia from the WT, gip1 mutant, and ten spontaneous suppressor strains at 14-dpi. The inoculation sites were indicated with black dots. For a–d, similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

In infection assays with flowering wheat heads, the wild type and gip1 mutant caused typical head blight symptoms at 14 days post-inoculation (dpi). However, all 10 suppressor strains caused disease symptoms only on the inoculated spikelets at 14 dpi or even 20 dpi (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 8). These results indicate that spontaneous suppressors of gip1 had mutations that were suppressive to the defect of gip1 in sexual development but detrimental to the spreading of infectious hyphae via the rachis to neighboring spikelets.

Suppressor mutations specifically occurred in FgVeA

Three suppressor strains, S1, S5, and S7, were selected for whole-genome sequencing analysis. In comparison with the updated genome sequence of the wild-type strain PH-128, all of them have mutations in the FgVeA gene (FG1G22150) (Supplementary Table 3). Suppressor S1 had a deletion of two nucleotides (A1436G1437) that caused a frameshift after S479. Suppressors S5 and S7 had the A583G and G595A substitutions that resulted in the K195E and G199S mutations, respectively (Fig. 6a).

a Spontaneous suppressor mutations identified in FgVeA and sequence alignment of the Velvet domain (purple box) of FgVeA and its orthologs from labeled ascomycetes. PEST, proline-, glutamate-, serine-, and threonine-rich motif. b Cultures of three selected spontaneous suppressor strains (S1, S2, and S7), FgVeAS479fs, FgVeAP39L, FgVeAG199S, gip1 FgVeAS479fs, gip1 FgVeAP39L, and gip1 FgVeAG199S mutants were examined for colony growth on PDA (left panels) and perithecia/PIs formation on CA plates (right panels). Bar = 0.5 mm. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. Whereas suppressor S1 and gip1 FgVeAS479fs transformants only produced PIs, all other strains produced fertile perithecia with ascospore cirrhi. c The tertiary structure of the FgVeA (gray) and FgVelB (green) dimer predicted with AlphaFold v2 and visualized with the UCSF Chimera tool. The six mutation sites in the Velvet domain (blue) are in red. d The relative expression levels of five selected down-regulated genes assayed by qRT-PCR with RNA isolated from mating cultures of the indicated strains sampled at 3-dpf. Mean and SD were estimated with data from three independent replicates (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Because mutations in FgVeA were common in S1, S5, and S7, we then amplified and sequenced this gene from the remaining seven suppressor strains. Nonsynonymous mutations in FgVeA were identified in all of them (Fig. 6a). The velvet protein FgVeA is conserved in ascomycetous fungi and functions as a global regulator of hyphal growth, asexual and sexual development, secondary metabolism, and infection processes29. Whereas the S479fs frame-shift mutation results in the truncation of the C-terminal region, all six missense mutations in FgVeA (P39L, L127H, Y135C, K195E, P198L, and G199S) are in the conserved Velvet domain. Sequence alignment revealed that all of these missense mutation sites are well conserved in the FgVeA orthologs from ascomycetes (Fig. 6a). Interestingly, three of them, K195E, P198L, and G199S, are adjacent to each other and the P198L and G199S mutations were present in two and three suppressor strains, respectively.

Verification of suppressive effects of the P39L, G199S, and S479fs mutations in FgVeA on gip1

To verify the effect of S479fs mutation which was identified in suppressor S1, the FgVeAS479fs allele was generated and used to replace the FgVeA allele. We then used the gene replacement approach to delete GIP1 in the FgVeAS479fs mutant. Both the FgVeAS479fs and gip1 FgVeAS479fs mutants were reduced in growth rate (Fig. 6b). Whereas the FgVeAS479fs mutant formed fertile perithecia, the gip1 FgVeAS479fs mutant, similar to suppressor S1, developed PIs that were blocked in ascus and ascospore formation (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 9). These results indicate that the truncated FgVeA protein expressed in the FgVeAS479fs transformant can rescue the defect of gip1 in the formation of PIs but fails to rescue its defect in late stages of sexual development, including ascosporogenesis.

The P39L and G199S missense mutations identified in S2 and S7 were also verified for their suppressive effects on the gip1 mutant. To avoid spontaneous suppressor mutations, we first replaced the endogenous FgVeA allele with the FgVeAP39L and FgVeAG199S mutant alleles by gene replacement. Similar to suppressors S2 and S7, the FgVeAP39L and FgVeAG199S mutants were reduced in growth rate and plant infection (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 10). However, although the P39L and G199S mutations affected vegetative growth and plant infection, the FgVeAP39L and FgVeAG199S mutants were normal in perithecium formation and development of asci and ascospore cirrhi at 7-dpf (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 9).

We then deleted the GIP1 gene in the FgVeAP39L and FgVeAG199S mutants. The resulting gip1 FgVeAP39L and gip1 FgVeAG199S mutants were reduced in growth rate (Fig. 6b). On CA mating plates, they formed fertile perithecia. However, similar to suppressor strains S2 and S7, the gip1 FgVeAP39L and gip1 FgVeAG199S mutants were delayed in ascosporogenesis and asci with ascospores were not observed at 7-dpf but observed at 14-dpf (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 9). These results confirm that the P39L and G199S mutations in FgVeA could partially suppress the defect of the gip1 mutant in perithecium maturation and ascospore development.

Mutations in suppressor strains rescue the expression of DEGs in the gip1 mutant

Based on the prediction by AlphaFold v222, the missense mutation sites identified in suppressor strains are not situated on the VeA-VelB interaction surface. Instead, these mutations occurred at amino acid residues located within a groove in the tertiary structure, a region potentially involved in DNA binding (Fig. 6c). It is possible that these suppressor mutations in FgVeA enable the expression of genes important for perithecium development and ascosporogenesis that normally require the activation of intracellular signaling pathways by Gip1 GPCR. To test this hypothesis, five DEGs (FG2G04760, FG2G13000, FG2G39720, FG3G23790, and FG4G01590) down-regulated in the gip1 mutant were selected for qRT-PCR assays in mating cultures of suppressor strains S2 and S7. In comparison with the gip1 mutant, three of them, FG2G04760, FG2G13000, FG3G23790, had increased expression levels in both S2 and S7 (Fig. 6d). These results indicate that mutations in FgVeA may be suppressive to the gip1 mutant by rescuing the expression of down-regulated DEGs during sexual reproduction in F. graminearum.

Mat1-1-2 may serve as a shared target of the Gpmk1 MAPK pathway and the VeA complex

Microscopic observation indicates that Gip1 regulates the earlier stages of sexual development compared to the mating type genes (Fig. 1c, d). This suggests that the mating type genes might be regulated by Gip1. By analyzing the protein sequence of Mat proteins, we identified a potential MAPK phosphorylation site (PGS273P matching the consensus sequence PxS*P) in the Mat1-1-2 protein (Supplementary Fig. 11a). This putative MAPK phosphorylation site is highly conserved among Mat1-1-2 orthologs in Sordariomycetes species. To investigate the effect of the potential phosphorylation event on the function of Mat1-1-2, we generated the MAT1-1-2S273A construct and transformed it into the mat1-1-2 deletion mutant. Similar to the mat1-1-2 deletion mutant, transformants expressing MAT1-1-2S273A were defective in perithecium development (Supplementary Fig. 11b). Under the same conditions, the mat1-1-2/MAT1-1-2 complementation transformant was normal in sexual reproduction (Supplementary Fig. 11b). These results suggest that S273 in Mat1-1-2 is crucial for its function in sexual development. Given that MAPK signaling is downstream of Gip1, Gip1 may regulate the phosphorylation of Mat1-1-2 by activating the MAPK pathway.

As a mating type gene, MAT1-1-2 showed reduced transcription levels in the gip1 mutant (Supplementary Fig. 12), but its expression was partially restored by mutations in FgVeA (Supplementary Fig. 11c). In the promoter region of MAT1-1-2, a CTGGAGCAGAC sequence located 478 bp upstream from the ATG (181 bp upstream of the TSS) closely resembled the known VeA binding site (CTGGCCAAGGC) identified in Aspergillus nidulans brlA30 (Supplementary Fig. 11d). The recovered expression of MAT1-1-2 by mutations in FgVeA, combined with the presence of a putative FgVeA-binding motif in the promoter region of MAT1-1-2, further indicates that FgVeA may be involved in the transcriptional regulation of MAT1-1-2. Since FgVeA regulates the transcription of MAT-1-1-2 during the sexual development stage, its binding to the MAT-1-1-2 promoter may require stage-specific protein modifications. The exact mechanism still requires further investigation. Therefore, Mat1-1-2 may serve as a shared target of both Gip1 and FgVeA, either through stage-specific phosphorylation or transcriptional regulation.

Discussion

In ascomycetous yeasts that form naked asci, pheromone receptors play a pivotal role in cell recognition and act as key regulators of sexual reproduction2. For filamentous ascomycetes that develop complex fruiting bodies, earlier studies have shown the involvement of additional GPCRs, such as GprM and GprI in A. nidulans31, Gpr-1 in Neurospora crassa32, and Gia1 and Gip1 in F. graminearum16. In this study, we showed that Gip1, a non-pheromone GPCR receptor, spatiotemporally regulates two distinct differentiation processes during perithecial morphogenesis (Fig. 7). The gip1 mutant was blocked in the formation of PIs, which could be partially suppressed by hyperosmotic stress and wheat straws. However, those conditions failed to suppress the defects of the gip1 mutant in perithecium maturation (differentiation of the peridium layer, enlargement, and lacked ascogenous tissues). Therefore, unlike Gia1, its paralog, that specifically regulates ascosporogenesis after karyogamy16, Gip1 appears to regulate two earlier developmental stages during sexual reproduction, the transition from vegetative hyphae to PIs and development from PIs to young perithecia. Consistent with these observations, we identified two kinds of gip1 suppressor strains with mutations in FgVeA. Whereas suppressor S1 produced only a few melanized PIs, the other nine suppressors could form fertile perithecia with ascospores on CA plates, indicating that the suppressor mutation in S1 could only rescue PI formation but suppressor mutations in the other suppressors could also rescue further perithecium development.

In the homothallic fungus F. graminearum, the initiation of sexual structures commences with perithecium initials (PIs). These PIs gradually develop into young perithecia, further advancing into mature perithecia, ultimately resulting in the continuous release of ascospores. Whereas Gia1 serves a stage-specific role via the Gpmk1 pathway in meiosis and ascosporogenesis within developing asci, Gip1 senses distinct ligands for the regulation of two earlier developmental stages in sexual reproduction: the transition from vegetative hyphae to PIs and from PIs to young perithecia. Gip1 exerts control over the formation of PIs through the cAMP-PKA pathways, while the development of perithecia and the differentiation of peridia and ascogenous tissues rely on Gpmk1-mediated signaling. Mutations in the velvet protein FgVeA bypassed the requirement of Gip1 during the two-stage process of perithecial morphogenesis. P peridium, AT ascogenous tissue, O ostiole, AP apical paraphyses, C crozier.

In F. graminearum, the cAMP-PKA pathway is known to regulate perithecium formation12. In this study, we found that deletion of the PDE1 cAMP phosphodiesterase gene13 partially bypassed the requirement for GIP1 and facilitated PI formation in the gip1 mutant. Interestingly, the defects of the gip1 mutant in PI formation were also partially rescued by expressing FgPBS2DA to hyperactivate FgHog1. Because GIP1 encodes a typical GPCR but the HOG pathway is typically activated via the two-component histidine kinase system33,34, the elevated intracellular cAMP level in the gip1 FgPBS2 DA transformants suggested that suppressive effects of FgPBS2DA on PI formation may be related to cross-talking between these two signaling pathways. Cross-talking between the cAMP-PKA and HOG pathways has been reported in S. cerevisiae and other fungi34,35. We also showed that the gip1 FST7 DA transformants had no PI development on CA mating plates but formed some fertile perithecia on wheat straws. These findings suggest that the Fst11-Fst7-Gpmk1 MAPK pathway may act downstream of Gip1 to control perithecium maturation, while Gip1 operates upstream of the cAMP-PKA pathway to regulate PI formation (Fig. 7). Consistent with this observation, FgSte12, a homeodomain protein activated by the Gpmk1 MAPK pathway, plays a crucial role in perithecium maturation and ascospore formation36. The Fgste12 mutant, like the mat1-1-1 mutant, forms young perithecia (small, sterile perithecia) that have the peridium and limited ascogenous tissues but lack asci and ascospores. Therefore, GIP1 functions upstream from both the cAMP-PKA and Gpmk1 pathways to regulate two different differentiation processes in F. graminearum. In Magnaporthe oryzae, the cAMP-PKA pathway regulates the initiation of appressorium formation on hydrophobic surfaces but subsequent stages of appressorium maturation and penetration rely on the Pmk1 MAPK pathway37,38. The nematode-trapping fungi utilize multiple GPCRs to trigger downstream signaling pathways that promote trap development39,40. Interestingly, the same GPCR can also activate distinct downstream pathways at various differentiation stages, potentially due to the involvement of different subunits of trimeric G-proteins. In the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, once activated, the disassociated Gα and Gβγ subunits can activate the downstream cAMP signaling and Kss1 MAPK cascade, respectively41. F. graminearum may use similar strategies to relay intracellular signaling with both activated Gpa1 and Gβγ, which may explain why expressing the dominant active GPA1 allele failed to rescue the defects of the gip1 mutant in sexual reproduction16.

In an earlier study, the Fst11-Fst7-Gpmk1 MAP cascade was found to function downstream from Gia1 for regulating meiosis and ascosporogenesis16. Therefore, unlike in S. cerevisiae in which the pheromone response MAPK pathway is only activated by the recognition of pheromones by pheromone receptors, the Gpmk1 pathway i`s activated by stage-specific ligands recognized by Gip1 and Gia1 GPCRs to regulate genes important for two different sexual developmental processes in F. graminearum. It is likely that other Sordariomycetes have similar stage-specific functions of this well-conserved MAPK pathway during sexual reproduction, responding to stage-specific ligands. In F. graminearum, ~61% of the GIP1 transcripts exhibited an A-to-I mRNA editing event21, resulting in the S448G missense mutation in the C-terminal region that was found to be important for Gip1-specific intracellular signaling. Therefore, it is also possible that this stage-specific editing of Gip1 may affect downstream signaling specificities.

Interestingly, all ten spontaneous suppressor strains had mutations in FgVeA, a key component of the highly conserved Velvet complex42. Notably, suppressor mutations were not identified in FgVelB and FgLaeA, the other two key subunits of the Velvet complex, suggesting a special functional relationship between GIP1 and FgVeA. In A. nidulans, the GprH GPCR regulates sexual development via the cAMP-PKA and light-responsive VeA pathways31. Moreover, the Fus3 MAPK (the ortholog of Gpmk1) phosphorylates VeA, and the formation of VeA-VelB complex is reduced in the absence of AnFUS343. However, the functional relationship between FgVeA and the cAMP signaling and Gpmk1 MAPK pathways is not clear in F. graminearum. Suppressor S1 with a frameshift mutation in FgVeA formed PIs but no mature perithecia. This frameshift mutation leads to the truncation of the C-terminal region of VeA, which is known to interact with LaeA for protein modification and stability in A. nidulans44. The other nine suppressors with missense mutations in the Velvet domain formed fertile perithecia on CA plates although at a significantly reduced rate in comparison with the wild type. These results indicate that suppressor mutations in FgVeA could inefficiently bypass the requirement of Gip1-mediated cAMP-PKA signaling for PI formation and Gpmk1 signaling for perithecium maturation. Among the nine missense mutations, only three of them, P39L, L127H, and Y135C, are not in the SAKKFPGL region of the Velvet domain. Nevertheless, all of the mutations are localized within a groove in the tertiary structure predicted by AlphaFold2, which potentially participates in DNA binding. In A. nidulans, VeA demonstrated a robust binding affinity to the brlA probe that was not recognized by the VelB protein, implying that VeA acts as a direct DNA-binding protein to the brlA promoter30. In F. graminearum, these suppressor mutations in the Velvet domain may influence the DNA-binding capacity of the FgVeA protein, which is known to function as a global regulator governing the expression of genes involved in a diverse array of biological processes45,46,47.

In the budding yeast, the expression of pheromone precursor and receptor genes is under the control of transcription factors (TFs) in the mating type (MAT) locus48. In filamentous ascomycetes, MAT TFs are essential for mating in heterothallic species49. In F. graminearum, a homothallic species, the mat mutants form small, sterile perithecia because MAT TFs are important for post-mating processes, including ascogenous hyphal differentiation and growth50. However, the exact functions of MAT TFs in various differentiation processes and molecular mechanisms regulating their expressions are not clear. We found that the gip1 mutant was blocked in earlier sexual developmental processes than mutants deleted of MAT genes. Interestingly, Gip1 had the highest expression at 3 dpf, preceding the peak expression of MAT1-1-2 and MAT1-1-3 at 4 dpf16. Furthermore, orthologs of GIP1 and MAT1-1-2 are unique to Sordariomycetes. Deletion of MAT1-1-2 in Podospora anserina, Sordaria macrospora, and F. graminearum resulted in a full cessation of perithecium development before the formation of ascogenous hyphae50. In the gip1 mutant, MAT1-1-2 expression was down-regulated, which was partially rescued by suppressor mutations in FgVeA. In addition, S273 of Mat1-1-2 is a putative MAPK phosphorylation site (in the PxS273P motif) and the S273A mutation abolishes the function of Mat1-1-2, suggesting that, besides transcriptional regulation, Mat1-1-2 and possibly other MAT TFs may be phosphorylated by MAPK functioning downstream from Gip1 to regulate the expression of genes important for perithecium development. Indeed, among the 435 genes down-regulated in both the mat1-1(mat1-1-1\mat1-1-2\mat1-1-3) and mat1-2-1 mutants51, 153 of them were also down-regulated in the gip1 mutant, including a number of genes are unique to Sordariomycetes and important for the differentiation of ascogenous tissues52. Taken together, Gip1 may be functionally related to the MAT TFs in the regulation of perithecium maturation in F. graminearum and similar functional relationship may be conserved in other Sordariomycetes.

Methods

Strains and culture conditions of F. graminearum

The wild-type strain PH-153 and transformants generated in this study were routinely cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates at 25 °C. The growth on PDA plates was assayed as described19. For selfing, aerial hyphae of 7-day-old CA cultures or wheat straws agar cultures were pressed down with 600 μl of sterile 0.1% Tween 2019. For outcrossing, CA cultures of gip1 mutant were fertilized with 600 μl of conidium suspensions of H1-GFP transformant of the wild type54. Mating cultures were incubated under a black light lamp at 25 °C and examined for perithecium formation, ascus development, and ascospore discharge as described55. Protoplast preparation and PEG-mediated transformation were performed as described previously56. For selection in transformations, hygromycin B (CalBiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA), geneticin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and floxuridine (HY-B0097, MCE, USA) were added to the final concentration of 300, 200, and 10 μg ml−1, respectively.

Microscopic examinations

Perithecia and PIs were collected and fixed with 4% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) overnight at 4 °C and then dehydrated in a series of ethanol consisting of 30, 50, 70, 80, 90, and 100% (vol/vol). For SEM examinations, the dehydrated samples were coated with gold-palladium and examined with a JEOL 6360 scanning electron microscope (Jeol) as described previously17. For thick sections, the samples were embedded in Spurr resin and processed into 1 μm sections as described17,18. After staining with 0.5% (wt/vol) toluidine blue, thick sections were examined by an Olympus BX-53 microscope for ascogenous tissues and perithecium structures.

Generation of the FgPBS2 DA, FgMKK2 DA, and FST7 DA transformants

The S451D T455E mutations57 were incorporated into FgPBS2 by overlapping PCR58 with primers (Supplementary Data 2) carrying the corresponding mutations. The resulting PCR products were cloned into vector pFL2 as described59 to generate the FgPBS2DA construct. Similar approaches were applied to introduce the T197D T203E and S209D T213E mutations60,61 into FgMKK2 and FST7, respectively. The resulting FgPBS2DA, FgMKK2DA, and FST7DA constructs were verified through sequencing and were subsequently transformed into the gip1 or gip1 pde1 mutant. Transformants displaying resistance to geneticin were confirmed via PCR and assessed for perithecia formation.

Generation of transformants expressing chimeric GIP1 alleles

To express chimeric GIP1 alleles at the endogenous position, we initiated by creating the gip1 gene replacement construct using the hgh-tk cassette. This cassette involved the fusion of the hygromycin phosphotransferase (hph) cassette with the thymidine kinase (tk) gene62. Following the transformation of the wild-type strain PH-1, hygromycin-resistant transformants were verified by PCR for the deletion of GIP1. To generate the GIP1CTp allele, the CT region of GIP1 was replaced with the CT of GIA1 by overlapping PCR58. The PCR products containing flanking sequences of GIP1 were utilized for the transformation of protoplasts derived from the gip1 mutant previously generated using hph-tk. Subsequently, floxuridine-resistant transformants were isolated, screened via PCR, and further verified by sequencing to confirm the expression of the GIP1CTp allele. Similar approaches were used to generate the GIP1IR3p, GIP1NTp, GIP1EL1p, GIP1EL2p, and GIP1EL3p constructs and transformants. At least three independent gene replacement transformants (Supplementary Table 1) were generated for each construct. All the primers used to generate fragments and verification of transformants are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Generation of chimeric PRp27-GIP1-GFP transformants

To determine the stability of the chimeric GIP1CTp protein, the GIP1CTp-GFP construct under the control of the RP27 promoter were generate and transformed with XhoI-digested pFL2 into yeast strain XK1-25 by gap repair59. The resulting PRp27-GIP1CTp-GFP chimeric construct carrying the geneticin-resistant marker was transformed into the wild-type stain PH-1. The resulting transformants were screened by PCR and confirmed by examination for green fluorescent protein (GFP) signals. Similar approaches were used to generate the PRp27-GIP1-GFP, PRp27-GIP1NTp-GFP, PRp27-GIP1EL3p-GFP, PRp27-GIP1C88A-GFP, and PRp27-GIP1C167A-GFP constructs and transformants. All the primers used in the generation of site-directed mutagenesis strains are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Generation of GIP1 C88A, GIP1 C167A, and MAT1-1-2 S273A site-directed mutagenesis strains

For site-directed mutagenesis of GIP1C88A, the C88A amino-acid changes were introduced into GIP1 by overlapping PCR58. The PCR products containing flanking sequences of GIP1 were utilized for the transformation of protoplasts derived from the gip1 mutant previously generated using hph-tk. Subsequently, floxuridine-resistant transformants were isolated, screened via PCR, and further verified by sequencing to confirm the expression of the GIP1C88A allele. The same approach was used to generate the GIP1C167A and MAT1-1-2S273A site-directed mutagenesis strains. All the primers used in the generation of site-directed mutagenesis strains are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Generation of the FgVeA P39L, FgVeA G199S, and FgVeA S479fs transformants

To generate the FgVeAP39L allele, two PCR fragments were amplified from the wild-type strain using primers (FgVeA-1F/FgVeAP39L-2R and FgVeAP39L-3F/FgVeA-8R) (Supplementary Data 2). These fragments were subsequently fused as previously described58. The PCR products obtained were introduced into the protoplasts of the FgVeA mutant that was previously generated using hph-tk. Subsequently, isolates displaying resistance to floxuridine were collected, subjected to PCR screening, and further validated through sequencing to confirm the expression of the FgVeAP39L allele. Similar approaches were used to generate the FgVeAG199S and FgVeAS479fs transformants. For each strain, a minimum of two independent gene replacement transformants were generated.

Generation and characterization of gene deletion mutants

All the gene replacement constructs were generated with the split-marker approach27. For each gene, 0.7–1.2 kb upstream and downstream flanking sequences were amplified with primers listed in Supplementary Data 2 and connected to hph-tk by overlapping PCR. After the transformation of the resulting PCR products into protoplasts of the wild type, hygromycin-resistant transformants were isolated and screened for gene deletion mutants by PCR as described58 (Supplementary Fig. 13). To generate the gip1 pde1 mutants, the flanking sequences of PDE1 were amplified and connected to hph-tk by overlapping PCR58. After the transformation of the resulting PCR products into protoplasts of the GIP1NTp strain, hygromycin-resistant transformants were isolated and screened for gene deletion mutants by PCR (Supplementary Fig. 13). Similar approaches were used to generate the gip1 FgVeAP39L, gip1 FgVeAG199S, and gip1 FgVeAS479fs transformants (Supplementary Fig. 13). Two independent gene replacement mutants for each gene were identified and listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Western blot and MAPK phosphorylation assays

Total proteins were isolated from vegetative hyphae harvested from 12 h YEPD cultures with protein lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously63. After separation on 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a nylon membrane, the expression of chimeric GIP1-GFP proteins and MAPKs were detected with related antibodies. The expression of chimeric GIP1-GFP proteins was assayed with a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). MAPKs have conserved dual phosphorylation sites for activation (TEY or TGY). Antibodies for detecting phosphorylation-specific MAPKs (anti-TpEY and anti-TpGY antibodies) are commercially available and used in this study to detect MAPK phosphorylation. Whereas we used the Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (TpEY) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) to detect the phosphorylation of Mgv1 and Gpmk1 MAPKs in F. graminearum with expected sizes of 47 and 41 kDa, respectively63, the Phospho-p38 MAPK (TpGY) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) was used for the detection of FgHog1 (with an expected size of 41 kDa) phosphorylation. The expression of Mgv1, Gpmk1, and FgHog1 was assayed with the anti-Mgv1/anti-Gpmk1/anti-FgHog1 antibodies (Hangzhou HuaAn Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Detection with a monoclonal anti-Tubulin2 antibody (Hangzhou HuaAn Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) or anti-GAPDH antibody (Hangzhou HuaAn Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used as the internal control64.

Assays for intracellular cAMP levels

Freshly hyphae of the gip1 mutant and gip1 FgPBS2DA strain were harvested from 12 h YEPD cultures for cAMP assays. Intracellular cAMP extraction was followed as previously described65 with additional modifications. Briefly, lyophilized fungal biomass was individually ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and equal weights of the fine powder was re-suspended in 200 ml of chilled 6% Trichloro acetic acid (TCA) and incubated on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation at 8000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected and extracted four times with five volumes of water-saturated diethyl ether to remove the TCA. The remaining aqueous extract was lyophilized and dissolved in the assay buffer. High-performance liquid chromatography was used to assay for cAMP levels and analytical standards of cAMP (SA8900) were purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). The operating conditions were as follows: the mobile phase consisted of 0.1 M dihydrogen phosphate (pH 4.0): acetonitrile (97:3, vol/vol); the flow rate was 1.0 ml min−1; the DAD detector was set to a wavelength of 254 nm; and the column temperature was 40 °C. Data from three independent replicates were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation.

RNA-seq analysis

RNA samples were isolated from both hyphae and perithecia formed on CA plates of the wild type and gip1 mutant at 3-dpf, and used for RNA extraction with TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA). After treatment with RNase-free DNase I, Poly(A)+mRNA was isolated with the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England Biolabs) following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Strand-specific RNA-seq libraries were constructed for two independent biological replicates of each strain with the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs) and sequenced by Illumina HiSeq 2500 with the 2 × 150-base-pair paired-end read mode at Novogene Bioinformatics Technology (Beijing, China). The resulting RNA-seq reads were mapped onto the reference genome of F. graminearum wild-type strain PH-128,53 by HISAT266. The number of reads (count) mapped to each gene was calculated by featureCounts67. Differential expression analysis of genes was performed using the edgeRun package68 with the UCexactTest function. Genes with log2FC (log2 fold change) greater than 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) less than 0.05 were regarded as DEGs. GO enrichment analysis was performed with Blast2GO69. The P-values were adjusted with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure70 by controlling the FDR to 0.05. All the Perl, R, and Shell scripts used in this study for sequencing and other analysis were available on GitHub as described71.

Infection assays with flowering wheat heads

The pathogenicity of each strain on flowering wheat heads was evaluated as described previously17. In brief, conidia from 5-day-old CMC cultures were freshly collected, resuspended to 105 spores/ml in sterile double-distilled wate, and used for inoculation. The florets in the central spikelet of 6-week-old flowering wheat heads from the XiaoYan 22 cultivar were inoculated with 10 μl of the conidial suspension, while control heads were inoculated with 10 μl of sterile water. The inoculated wheat heads were covered with a plastic bag for 48 h to maintain high humidity. Spikelets displaying typical wheat scab symptoms were examined at 14 or 20 dpi. A minimum of ten wheat heads were analyzed for each strain.

Developing a yeast reporter strain for screening ligand(s) recognized by Gip1

Construction of the yeast reporter system and ligand screening were performed using established protocols16. Briefly, the N-terminal extracellular region (NT) and three extracellular loops (EL1, EL2, and EL3) of yeast Ste2 were replaced with those of Gip1 to generate the chimeric STE2 CH allele by gene fragment synthesis (Sangon Biotech, China). The STE2 gene was replaced by the resulting STE2 CH allele in yeast strain BY4741 (MATa his3 leu2 met15 ura3) that was transformed with the P FUS1-GFP reporter construct was generated by cloning GFP behind the promoter of FUS1 (a yeast pheromone inducible gene). For the preparation of crude extracts, perithecia collected from the mating plate were ground into a powder using liquid nitrogen and then divided into four aliquots. Each aliquot was mixed with 1.5 ml of extract solution (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF) and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. For the yeast treatment, cells harvested from an overnight YPD culture were mixed with 50 µl of crude perithecial extract and cultured at 30 °C for 6 h before being examined using epifluorescence microscopy. To test sensitivity to protein degradation, protease K was added to the crude extracts at a final concentration of 100 µg/ml. The mixtures were incubated at 55 °C for 1 h, followed by heating at 95 °C for 10 min to inactivate the protease K.

Spontaneous suppressor strains of the gip1 mutant and whole genome re-sequencing analysis

The center section of small clusters of perithecia of the gip1 mutant were transferred with sterile toothpicks to fresh PDA plates. After single spore isolation, all the spontaneous suppressors were assayed for defects in growth, sexual reproduction, and plant infection17,72. To identify mutations in selected suppressor strains (S1, S5 and S7), DNA isolated from 12 h hyphae of gip1 mutant and three selected suppressor strains were sequenced by Illumina HiSeq-2500 at Novogene Bioinformatics Institute (Beijing, China) to 50x coverage with pair-end libraries. The sequence reads were mapped onto the reference genome of the wild-type strain PH-128,53 by Bowtie 2.2373, and variants were called by SAMtools with the default parameters74. Annotation of the mutation sites was performed with a Variant Effect Predictor (VEP)75.

Assays for the expression level of DEGs down-regulated genes by qRT-PCR

RNA samples were isolated from vegetative hyphae at 12 h YEPD cultures, and both hyphae and perithecia formed on CA mating plates at 3-dpf of the wild type, gip1 mutant, suppressor strains S2 and S7. The total RNA of each strain was isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with Fast Quant RT Kit (TIANGEN, China) before performing qRT-PCR assays with the CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-RAD, USA). Relative expression levels of DEGs down-regulated genes were assayed by qRT-PCR with the FgACTIN gene (FG4G14550) as the internal control17. The relative expression level of individual genes or transcripts was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method76. Data from three independent replicates were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation.

Bioinformatic analysis

Multiple sequence alignments were performed with Clustal X 2.177 and visualized with the Jalview (version 2.11.1.0)78. Tertiary structures of Gip1, Gia1, VeA, and VelB were predicted with AlphaFold v2 (colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb) and visualized with the UCSF Chimera tool79. Phosphorylation sites were predicted by NetPhos-3.180 with default settings. Expression data of DEGs down-regulated genes were retrieved from FgBase28 and visualized by bioinformatics (www.bioinformatics.com.cn).

Statistics and reproducibility

All data were presented as means ± standard deviation. The number of biologically independent samples (n) was indicated in the figure legends. Statistical significance tests were performed with GraphPad Prism version 8.0.0.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. The RNA-seq and DNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database under accession codes PRJNA1261486 and PRJNA1261822, respectively. The reference genome of F. graminearum strain PH-1 used in this study is available in the NCBI GenBank database under accession code PRJNA782099. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Sieber, B., Coronas-Serna, J. M. & Martin, S. G. A focus on yeast mating: From pheromone signaling to cell-cell fusion. Semin. Cell Developmental Biol. 133, 83–95 (2023).

Versele, M., Lemaire, K. & Thevelein, J. Sex and sugar in yeast: two distinct GPCR systems. EMBO Rep. 2, 574–579 (2001).

Bardwell, L., Cook, J. G., Thorner, J., Chang, E. C. & Cairns, B. R. Signaling in the yeast pheromone response pathway: specific and high-affinity interaction of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases Kss1 and Fus3 with the upstream MAP kinase kinase Ste7. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 3637–3650 (1996).

Kim, H. & Borkovich, K. A. A pheromone receptor gene, pre-1, is essential for mating type-specific directional growth and fusion of trichogynes and female fertility in Neurospora crassa. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 1781–1798 (2004).

Lord, K. M. & Read, N. D. Perithecium morphogenesis in Sordaria macrospora. Fungal Genet. Biol. 48, 388–399 (2011).

Moonjely, S. et al. Update on the state of research to manage Fusarium head blight. Fungal Genet. Biol. 169, 103829 (2023).

Goswami, R. S. & Kistler, H. C. Heading for disaster: Fusarium graminearum on cereal crops. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5, 515–525 (2004).

Johns, L. E., Bebber, D. P., Gurr, S. J. & Brown, N. A. Emerging health threat and cost of Fusarium mycotoxins in European wheat. Nat. Food 3, 1014–1019 (2022).

Chen, Y., Kistler, H. C. & Ma, Z. Fusarium graminearum trichothecene mycotoxins: biosynthesis, regulation, and management. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 57, 15–39 (2019).

Guenther, J. C. & Trail, F. The development and differentiation of Gibberella zeae (anamorph: Fusarium graminearum) during colonization of wheat. Mycologia 97, 229–237 (2005).

Ren, J. et al. Deletion of all three MAP kinase genes results in severe defects in stress responses and pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Stress Biol. 2, 6 (2022).

Hu, S. et al. The cAMP-PKA pathway regulates growth, sexual and asexual differentiation, and pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 27, 557–566 (2014).

Jiang, C. et al. TRI6 and TRI10 play different roles in the regulation of deoxynivalenol (DON) production by cAMP signalling in Fusarium graminearum. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 3689–3701 (2016).

Lee, J., Leslie, J. F. & Bowden, R. L. Expression and function of sex pheromones and receptors in the homothallic ascomycete Gibberella zeae. Eukaryot. Cell 7, 1211–1221 (2008).

Kim, H.-K., Lee, T. & Yun, S.-H. A putative pheromone signaling pathway is dispensable for self-fertility in the homothallic ascomycete Gibberella zeae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45, 1188–1196 (2008).

Ding, M. et al. A non-pheromone GPCR is essential for meiosis and ascosporogenesis in the wheat scab fungus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2313034120 (2023).

Jiang, C. et al. An expanded subfamily of G-protein-coupled receptor genes in Fusarium graminearum required for wheat infection. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1582–1591 (2019).

Zheng, Q. et al. The MAT locus genes play different roles in sexual reproduction and pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS ONE 8, e66980 (2013).

Wang, C. et al. Functional analysis of the kinome of the wheat scab fungus Fusarium graminearum. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002460 (2011).

Brown, N. A., Schrevens, S., Dijck, P. V. & Goldman, G. H. Fungal G-protein-coupled receptors: mediators of pathogenesis and targets for disease control. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 402–414 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Genome-wide A-to-I RNA editing in fungi independent of ADAR enzymes. Genome Res. 26, 499–509 (2016).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Shin, J. Y. et al. Functional characterization of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases in the cereal head blight fungus Fusarium graminearum. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 2053–2067 (2017).

Kim, D.-W. et al. FgPKS7 is an essential player in mating-type-mediated regulatory pathway required for completing sexual cycle in Fusarium graminearum. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 1972–1990 (2020).

Lee, Y., Son, H., Shin, J. Y., Choi, G. J. & Lee, Y.-W. Genome-wide functional characterization of putative peroxidases in the head blight fungus Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 715–730 (2018).

Kim, W. et al. Transcriptional divergence underpinning sexual development in the fungal class sordariomycetes. mBio 13, e0110022 (2022).

Catlett, N. L., Yoder, O. & Turgeon, G. B. Split-marker recombination for efficient targeted deletion of fungal genes. Fungal Genet. Newslett 50, 9–11 (2003).

Lu, P. et al. Landscape and regulation of alternative splicing and alternative polyadenylation in a plant pathogenic fungus. N. Phytologist 235, 674–689 (2022).

Keller, N. P. Fungal secondary metabolism: regulation, function and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 167–180 (2018).

Ahmed, Y. L. et al. The velvet family of fungal regulators contains a DNA-binding domain structurally similar to NF-κB. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001750 (2013).

Reis, T. F. D. et al. GPCR-mediated glucose sensing system regulates light-dependent fungal development and mycotoxin production. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008419 (2019).

Krystofova, S. & Borkovich, K. A. The predicted G-protein-coupled receptor GPR-1 is required for female sexual development in the multicellular fungus Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 5, 1503–1516 (2006).

Jiang, C., Zhang, X., Liu, H. & Xu, J.-R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plant pathogenic fungi. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006875 (2018).

Bahn, Y.-S. et al. Sensing the environment: lessons from fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 57–69 (2007).

Cai, E. et al. Histidine kinase Sln1 and cAMP/PKA signaling pathways antagonistically regulate Sporisorium scitamineum mating and virulence via transcription factor Prf1. J. Fungi 7, 610 (2021).

Son, H. et al. A phenome-based functional analysis of transcription factors in the cereal head blight fungus, Fusarium graminearum. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002310 (2011).

Xu, J.-R. & Hamer, J. E. MAP kinase and cAMP signaling regulate infection structure formation, and pathogemc growth in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe gnsea. Genes Dev. 10, 2696–2706 (1996).

Osés-Ruiz, M., Cruz-Mireles, N. & Martin-Urdiroz, M. Appressorium-mediated plant infection by Magnaporthe oryzae is regulated by a Pmk1-dependent hierarchical transcriptional network. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 1383–1397 (2021).

Kuo, C.-Y. et al. The nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora detects prey pheromones via G protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 1738–1751 (2024).

Hu, X. et al. GprC of the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys flagrans activates mitochondria and reprograms fungal cells for nematode hunting. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 1752–1763 (2024).

Dohlman, H. G. & Thorner, J. Regulation of G protein-initiated signal transduction in Yeast: paradigms and principles. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 703–754 (2001).

Bayram, O. Z. R. et al. VelB/VeA/LaeA complex coordinates light signal with fungal development and secondary metabolism. Science 320, 1504–1506 (2008).

Bayram, Ö et al. The Aspergillus nidulans MAPK module AnSte11-Ste50-Ste7-Fus3 controls development and secondary metabolism. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002816 (2012).

Bayram, O. Z. S. et al. LaeA control of velvet family regulatory proteins for light-dependent development and fungal cell-type specificity. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001226 (2010).

Merhej, J. et al. The velvet gene, FgVe1, affects fungal development and positively regulates trichothecene biosynthesis and pathogenicity in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 363–374 (2012).

Jiang, J., Liu, X., Yin, Y. & Ma, Z. Involvement of a velvet protein FgVeA in the regulation of asexual development, lipid and secondary metabolisms and virulence in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS ONE 6, e28291 (2011).

Cea-Sánchez S., Martín-Villanueva S., Gutiérrez G., Cánovas D., Corrochano L. M. VE-1 regulation of MAPK signaling controls sexual development in Neurospora crassa. mBio, e0226424 (2024).

Heitman, J., Sun, S. & James, T. Y. Evolution of fungal sexual reproduction. Mycologia 105, 1–27 (2017).

Bennett, R. J. & Turgeon, B. G. Fungal sex: the ascomycota. Microbiol. Spectr. 4, 3637–3650 (2016).

Debuchy, R., Berteaux-Lecellier, V. & Silar, P. Mating systems and sexual morphogenesis in ascomycetes. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 33, 501–535 (2010).

Kim, H.-K. et al. A large-scale functional analysis of putative target genes of mating-type loci provides insight into the regulation of sexual development of the cereal pathogen Fusarium graminearum. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005486 (2015).

Trail, F., Wang, Z., Stefanko, K., Cubba, C. & Townsend, J. P. The ancestral levels of transcription and the evolution of sexual phenotypes in filamentous fungi. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006867 (2017).

Cuomo, C. A. et al. The Fusarium graminearum genome reveals a link between localized polymorphism and pathogen specialization. Science 317, 1400–1402 (2007).

Chen, D. et al. Sexual specific functions of Tub1 beta-tubulins require stage-specific RNA processing and expression in Fusarium graminearum. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 4009–4021 (2018).

Cavinder, B., Sikhakolli, U., Fellows, K. M. & Trail, F. Sexual development and ascospore discharge in Fusarium graminearum. J. Visualized Exp. 61, e3895 (2012).

Hou, Z. et al. A mitogen-activated protein kinase gene (MGV1) in Fusarium graminearum is required for female fertility, heterokaryon formation, and plant infection. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 15, 1119–1127 (2002).

Nakic, Z. R., Seisenbacher, G., Posas, F. & Sauer, U. Untargeted metabolomics unravels functionalities of phosphorylation sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Syst. Biol. 10, 104 (2016).

Yu, J.-H. et al. Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41, 973–981 (2004).

Zhou, X., Li, G. & Xu, J.-R. Efficient approaches for generating GFP fusion and epitope-tagging constructs in filamentous fungi. Methods Mol. Biol. 722, 199–212 (2011).

Zhao, X., Kim, Y., Park, G. & Xu, J.-R. A mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade regulating infection-related morphogenesis in Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell 17, 1317–1329 (2005).

Zhang, X., Liu, W., Li, Y., Li, G. & Xu, J.-R. Expression of HopAI interferes with MAP kinase signalling in Magnaporthe oryzae. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 4190–4204 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. A phosphorylated transcription factor regulates sterol biosynthesis in Fusarium graminearum. Nat. Commun. 10, 1228 (2019).

Zhang, X., Bian, Z. & Xu, J.-R. Assays for MAP kinase activation in Magnaporthe oryzae and other plant pathogenic fungi. Methods Mol. Biol. 1848, 93–101 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Stage-specific functional relationships between Tub1 and Tub2 beta-tubulins in the wheat scab fungus Fusarium graminearum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 132, 103251 (2019).

Ramanujam, R. & Naqvi, N. I. PdeH, a high-affinity cAMP phosphodiesterase, is a key regulator of asexual and pathogenic differentiation in Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000897 (2010).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360 (2015).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Dimont, E., Shi, J., Kirchner, R. & Hide, W. edgeRun: an R package for sensitive, functionally relevant differential expression discovery using an unconditional exact test. Bioinformatics 31, 2589–2590 (2015).

Conesa, A. et al. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676 (2005).

Ghosh, D. Wavelet-based Benjamini-Hochberg procedures for multiple testing under dependence. Math. Biosci. Eng. 17, 56–72 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. Characterization of the two-speed subgenomes of Fusarium graminearum reveals the fast-speed subgenome specialized for adaption and infection. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 140 (2017).

Gao, X. et al. FgPrp4 kinase is important for spliceosome B-complex activation and splicing efficiency in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005973 (2016).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

McLaren, W. et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics 26, 2069–2070 (2010).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. Multiple Sequence Alignment Using ClustalW and ClustalX. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics, 2.3.1-2.3.22 (2003).

McLaren, W. et al. Alignment of Biological Sequences with Jalview. Methods Mol. Biol. 2231, 203–224 (2021).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021).

Blom, N., Sicheritz-Pontén, T., Gupta, R., Gammeltoft, S. & Brunak, S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 4, 1633–1649 (2004).

Acknowledgments

We thank Guoyun Zhang from the State Key Laboratory for Crop Stress Resistance and High-Efficiency Production for SEM examination. We also thank Zhe Tang, Jie Yang, Yuhan Zhang, Yutong Ma, and Xiaofei Zhao for assistance with sample preparation and microscopic observation. We also thank Dr. Qinhu Wang and Ming Xu for fruitful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1304400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32172378, 32372503, and 32402334), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2024QC033), and the Open Project Program (SKLCSRHPKF2025014) of State Key Laboratory for Crop Stress Resistance and High-Efficiency Production of NWAFU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J., M.D. and J.-R.X. conceived and designed the experiments; M.D., W.W., Y.W., P.H., A.X., D. X. and G.W. performed the experiments; M.D., H.L., H.C. and C.J. contributed materials/analysis tools and analyzed the data; C.J., M.D. and J.-R.X. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information