Abstract

Viral invasion of the host cell causes some of the most dramatic changes in biology. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) extensively remodels host cells, altering nuclear shape and generating a cytoplasmic viral-induced assembly compartment (vIAC). How these striking morphology changes occur in the context of host gene regulation is still emerging. Histone variant macroH2A1 is both important for maintaining nuclear integrity and functions to promote herpes simplex virus infection. Therefore, we hypothesized it may also function in cytomegalovirus infection. Here, we discovered that macroH2A1 is necessary for HCMV-induced cellular reorganization and formation of infectious progeny. Using RNA-seq in infected cells, we find that while all viral genes are highly expressed in the absence of macroH2A1, many HCMV-induced host genes are not. Remarkably, hundreds of these HCMV-induced macroH2A1-dependent host genes are associated with a neuronal signature. Further, we find that HCMV immediate early protein, IE1, is both necessary and sufficient to induce these neuronal genes, providing a mechanism of activation. Together, our findings demonstrate that HCMV hijacks a dormant neuronal secretory pathway through chromatin manipulation for efficient virion maturation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a ubiquitous herpesvirus with seropositivity ranging from 65 to 100%1,2. In immunocompetent individuals, HCMV is typically asymptomatic or results in mild cold-like symptoms3. In contrast, congenital HCMV infection is one of the leading causes of infectious birth defects affecting about 1 in every 200 live births4. Additionally, cytomegalovirus is a chief cause of morbidity and mortality in both solid organ and stem cell transplant recipients5 and individuals with poorly controlled HIV6.

HCMV infection of the host cell induces large scale cellular remodeling7. The host nucleus forms a characteristic kidney-bean shape while host chromatin becomes polarized to one side8 and large-scale cytoskeletal rearrangement causes the nucleus to spin8,9. Simultaneously, the Golgi, endosome, and other cellular membranes are reorganized during HCMV infection to form the viral-induced assembly compartment (vIAC)10. Viral replication occurs in the nucleus, after which progeny capsids exit from the nucleus and pass through the vIAC for tegumentation and final maturation11,12,13. Importantly, unlike other lytic herpesvirus infections, HCMV does not shut down host transcription14, though how host gene expression is altered by HCMV remains actively under investigation.

Cellular remodeling is closely controlled by host gene expression, which in turn is regulated by histone modifications and histone variants15,16,17. MacroH2A1 is a histone variant that can replace the core histone H2A. MacroH2A1 was initially discovered on the inactive X chromosome associated with transcriptional repression18,19. In contrast, macroH2A1 is also required for gene activation in several contexts including serum starvation response19, smooth muscle differentiation20, and neuronal differentiation21. We previously showed how macroH2A1-dependent heterochromatin is critical for herpes simplex (HSV-1) egress from the nuclear compartment22. Therefore, we hypothesized that macroH2A1 may also function in cytomegalovirus infection.

Here, we demonstrate that macroH2A1 is necessary for HCMV-induced cellular reorganization by immunofluorescence and electron microscopy, and formation of infectious progeny by plaque assay and mass spectrometry of purified virions. We further show that HCMV predominantly upregulates hundreds of host genes in a macroH2A1-dependent manner, driven by viral immediate early IE1. We find that many of the genes that are HCMV-induced and macroH2A1-dependent are associated with a neuronal signature. We further demonstrate that IE1, which directly interacts with macroH2A1, is both necessary and sufficient to induce these neuronal genes. This upregulation of neuronal-specific genes is essential for efficient HCMV infectious progeny production and defines a previously unknown mechanism wherein HCMV has evolved to control host gene expression to promote progeny maturation and viral spread.

Results

MacroH2A1 is required for production of infectious HCMV progeny

Due to the importance of macroH2A1 in lytic HSV-1 infection22 and the observation that macroH2A1 mRNA levels increase during lytic HCMV infection23, we hypothesized that macroH2A1 is also necessary for efficient HCMV lytic infection. To investigate this hypothesis, we infected wild-type human foreskin fibroblast cells (WT HFF-T) and our established macroH2A1 CRISPR knock-out cells (macroH2A1 KO HFF-T)22 with HCMV (Towne or TB40E) and measured infectious viral progeny. We found that HCMV grown in macroH2A1 KO cells produced approximately 30-fold fewer infectious progeny, than HCMV grown in control cells (Fig. 1A, Sup Fig. 1A).

HCMV (A) Infectious progeny produced from HCMV infected WT and macroH2A1 KO HFF-T cells quantified by plaque assay at days post infection (dpi) as indicated. Viral yield is the percent yield compared to wild type, with errors bars representing SEM. **** at 4 hpi denotes p = 7.2 × 10−8 and at 6 hpi p = 1.1 × 10−7 by two-way ANOVA with follow up Šídák multiple comparisons test. n = 3 biological replicates. B Representative western blots of viral proteins in cells as in (A) during HCMV infection at hours post infection (hpi) compared to mock (M) as indicated. Vinculin is shown as loading control. C Heat map of viral genes measured by RNA sequencing at 4, 16, 24, 48, and 72 hpi compared to mock (M). n = 3 biological replicates. D Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) quantification of HCMV genomes extracted from infected WT and macroH2A1 KO cells at 4 h (input), 4, and 6 dpi. Bar graphs show the mean with error bars indicating SEM. n = 3 biological replicates. No significance at any time point by two-way ANOVA with follow up Šídák multiple comparisons test. E ddPCR quantification of HCMV genomes released from cells as in (D) and isolated from supernatants (sups) after nuclease treatment, indicating encapsidated genomes. Error bars represent the SEM of three biological replicates. No significance at any time point by two way ANOVA with follow up Šídák multiple comparisons test. F Representative immunofluorescence images of WT and macroH2A1 KO cells during HCMV infection at mock and 72 hpi. DAPI is shown in cyan, and viral protein pp28 is shown in magenta. Scale bar represents 10 µm. G Quantification of the volume of viral induced assembly compartments (vIACs) measured by pp28 fluorescence. Bar graphs show mean with error bars indicating SEM. * denotes p = 2.12×10−2 by unpaired T-test with n = 42 in WT and n = 50 in KO. H Quantification of nuclear volume of HCMV-infected cells at 72 hpi. Bar graphs show mean with error bars indicating SEM. *** denotes p = 5.7×10−4 by unpaired T-test with n = 44 in WT and n = 49 in KO.

We next asked whether macroH2A1 loss affected viral protein and RNA accumulation. We measured viral protein levels by western blot of representative immediate early (IE1/2), early (UL44), late tegument (pp28 and pp65), and late envelope (gB) proteins. We found that all measured viral proteins were robustly expressed at earlier time points, and to a stronger degree in macroH2A1 KO cells for the duration of the time course to 96hpi (Fig. 1B).

To determine whether other viral genes not measured by western blot might explain the decrease in infectious progeny produced, we next measured the viral transcriptome by RNA sequencing. We performed bulk RNA sequencing of HCMV-infected WT and macroH2A1 KO cells at 4, 16, 24, 48, and 72 h post infection (hpi). We found that in macroH2A1 KO cells, early gene expression was initiated by 4 hpi and that immediate early viral genes were expressed at a higher level compared to their levels in WT cells. By 16 hpi, many late viral transcripts were already expressed in macroH2A1 KO cells, while late transcripts were not expressed in WT control cells until 48 hpi (Fig. 1C, Sup Fig. 1B, C). Thus, HCMV transcripts and proteins were expressed earlier and to a higher level in macroH2A1 KO cells compared to WT cells.

As increased protein and RNA expression in macroH2A1 KO cells did not explain the strong reduction in infectious progeny, we next investigated genome replication. We found that within cells there was no significant change in viral genomes between WT and macroH2A1 KO cells measured by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), though early viral replication was faster in macroH2A1 KO cells (Fig. 1D, Sup Fig. 1D). Similarly, we found no significant change in nuclease-resistant genomes released into the supernatant (Fig. 1E), indicating that the reduction in infectious progeny is not due to replication or egress defects but rather that viral progeny grown in macroH2A1 KO cells are defective.

MacroH2A1 is required for nuclear rearrangement and vIAC formation

Proper maturation of HCMV progeny occurs in the vIAC. Therefore, we hypothesized that the loss of macroH2A1 results in a viral maturation defect due to a defective vIAC. We used immunofluorescence to visualize infected cells. Strikingly, we found that the vIACs were significantly smaller in macroH2A1 KO cells (Fig. 1F, G, Sup Fig. 1E), the nuclei did not expand as expected, and the nuclei did not form the characteristic kidney-bean shape (Fig. 1F, H, Sup Fig. 1F). Furthermore, we observed that infected macroH2A1 KO cells also retained the centrosomes and tubulin boundary between cells, suggesting that HCMV-induced syncytia are malformed in infected macroH2A1 KO cells compared to infected WT cells (Sup Fig. 1G). Our findings demonstrate that macroH2A1 plays a key role in HCMV-induced cellular remodeling and formation of vIACs.

HCMV rearranges host cytosolic structures in a macroH2A1-dependent manner

To determine if the structural rearrangements that are required for vIAC formation occur in the absence of macroH2A1, we investigated cellular organization using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). We found that while the overall cellular structure was comparable in mock-treated WT and macroH2A1 KO cells (Fig. 2A), at 4 days post infection (dpi) HCMV infected cells exhibited dramatically different cytoplasmic structures. We observed that the measurable length of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) regions was significantly shorter in WT cells compared to macroH2A1 KO cells (Fig. 2B, Sup Fig. 2A–D). Our findings suggest that without macroH2A1, HCMV is unable to disrupt the host ER.

A Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of mock-treated WT and macroH2A1 KO HFF-T cells showing the uninfected state of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). B Representative TEM images at 4 days post infection (dpi) with HCMV. C Representative TEM images of viral-induced assembly compartments (vIAC) at 4dpi as indicated. Below: Zooms with annotated versions to the right. Scale bars as indicated. D Quantification of vIAC subcompartment area. Violin plot depicts median, and upper, and lower quartiles as dotted lines. *** denotes p < 0.001 or p = 4.3×10−4 by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with n = 143 for WT and n = 138 for KO. E Scatter plot of HCMV viral proteins identified by LC-MS in virion preparations from WT- and macroH2A1 KO-infected cells. Enriched proteins (fold change [FC] ≥ 1) in macroH2A1 KO virion preparations are shown as gray dots, while depleted proteins (FC ≤ −1) are highlighted in orange (n = 3 technical replicates), envelope proteins in red. The identified HCMV viral proteome was normalized to the major capsid protein (MCP, UL86), which exhibited consistent abundance across all conditions. See Sup Fig. 3 and Sup Data 1 for further details.

Moreover, by TEM we observed further differences in vIAC formation. In WT cells we observed the vIAC was made up of large subcompartments, consistent with previous findings24. Each subcompartment was surrounded by a heterogeneous population of dense bodies, which are non-infectious HCMV particles comprised of enveloped viral proteins25,26. In contrast, the HCMV-infected macroH2A1 KO cells rarely formed these distinct large subcompartments (Fig. 2C, D, Sup Fig. 2E, F). In the macroH2A1 KO cells, the largest observable subcompartments, whose area was significantly smaller than those formed in WT cells, were rarely surrounded by dense bodies (Fig. 2D). The dense bodies in the infected macroH2A1 KO cells were largely homogenous individual structures distributed throughout the cytosol, compared to the heterogenous and conglomerated dense bodies in infected WT cells. Furthermore, virus particles observed in macroH2A1 KO cells frequently appeared malformed, consistent with the finding that macroH2A1 KO cells produce defective progeny (Fig. 2C, arrowhead). Taken together, these results support our hypothesis that macroH2A1 plays a major role in HCMV-induced cellular remodeling and viral maturation.

To investigate the hypothesis that vIAC differences observed by IF and TEM we associated with changes in virion composition, we next performed mass-spectrometry on HCMV virions. Supernatant from HCMV-infected WT and macroH2A1 KO cells was purified using a sucrose gradient to harvest virions and dense bodies. These samples were then analyzed in technical triplicates by liquid chromatography-tandem mass-spectrometry (LC-MS). In all samples, the protein abundance of the Major Capsid Protein (MCP, or UL86) was similar (Sup Fig. 3A). Thus, MCP was used to normalize the other protein levels. We found that numerous envelope proteins, including glycoproteins gO and gL, as well as various tegument proteins involved in secondary envelopment and antagonism of the innate immune system were significantly less abundant in virions grown in macroH2A1 KO cells compared to those grown in WT cells (Fig. 2E, Sup Fig. 3B). Furthermore, many viral and host proteins associated with transcription and viral genome replication, but not normally detected in virions, were more abundant in macroH2A1 KO-grown virions (Fig. 2E, Sup Fig. 3B–G). Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that the tegumentation and secondary envelopment of HCMV is reduced in macroH2A1 KO cells, supporting the observations from TEM that virions are malforming.

Loss of macroH2A1 prevents activation of neuronal genes during HCMV infection

To profile changes in host gene expression that might lead to the observed phenotypic effects on HCMV infection upon loss of macroH2A1, we analyzed the host transcriptomes of WT and macroH2A1 KO cells during the course of HCMV infection. Principal component analysis of our RNA-seq data showed all replicates clustering close to each other, indicating reproducibility. PC1 captured the time course of infection whereas PC2 captured the genotype (Sup Fig. 4A). We first identified a superset of genes that significantly changed in either one of the time points and/or one of the genotypes and then performed k-means (k = 4) clustering of Z-scores of gene expression across time and genotype. This analysis captured both time-dependent and genotype-dependent changes in gene expression during HCMV infection (Fig. 3A). Cluster 1 contained genes that had mixed to low expression in mock-treated cells but steadily increased in expression over the course of infection, peaking at 72 hpi in WT but remained low in the macroH2A1 KO cells (Sup Fig. 4F). Genes in this cluster were highly enriched for macroH2A1 and heterochromatin marker H3K27me3 in uninfected cells in our previously published CUT&Tag data set22 (Sup Fig. 4B–E). Clusters 2-4 captured time-dependent changes in expression that were mostly similar between WT and macroH2A1 KO conditions (Sup Fig. 4G–I). Cluster 2 contained genes that were activated at 48-72 hpi and expectedly included genes involved in DNA repair and metabolic processes, which have previously been reported to increase during infection27,28,29 (Sup Fig. 4K). Cluster 3 contained genes that were activated at 16-24 hpi before returning to low expression. Also as expected, this cluster contained genes associated with immune response and transcription (Sup. Figure 4L). Cluster 4 contained genes that were repressed throughout infection and contains genes associated with cellular reorganization and protein trafficking within the cell (Sup Fig. 4M). In striking contrast to clusters 2-4, cluster 1 genes were highly enriched for neuronal genes belonging to several Gene Ontology categories that highlighted neuronal function (Fig. 3B, Sup Fig. 4J). Notably, cluster 1 genes strikingly had significantly lower expression in macroH2A1 KO cells, with large fold changes, especially at 72 hpi (Fig. 3C). Cluster 1 genes, which are the most affected by the loss of macroH2A1, suggest that HCMV induces a neuronal-like transcriptional profile that increases over the course of infection.

A K-means clustering (k = 4) of gene expression changes over 72 hours of infection shown as a heatmap. Z-scores were calculated for each gene from its normalized count across the time course of CMV infection for WT and macroH2A1 KO cells. B The -log10(FDR) value for enrichment of neuronal GO categories in Cluster 1. C Volcano plot where the Log2(Fold Change) for WT vs. macroH2A1 KO is plotted against -log10(FDR) for genes in Cluster 1. Genes with Log2(Fold Change) > 1 and FDR ≤ 0.05 are marked in red. Neuronal genes selected for further characterization are labeled in blue. D Matrix of Euclidean distance between normalized expression profiles of CMV infection time course for WT and macroH2A1 KO, and other cell types. Gene expression datasets for other cell types were obtained from ENCODE. E PCA plot showing PC1 and PC3 for the same expression profiles plotted in (D).

To test the hypothesis that HCMV induces a neuronal-like phenotype that is blunted by the loss of macroH2A1, we compared our gene expression profiles to those of different cell types from ENCODE30,31. From ENCODE, we included expression profiles of IMR90 fibroblast cells, similar to our HFF cells, and cells differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells to form cells in the neuronal, muscle, and liver lineages. We first generated a distance matrix and observed that IMR90 clustered with all macroH2A1 KO time points and WT mock and early time points. However, WT cells at 48 and 72 hpi cluster with the other lineages we included in the analysis (Fig. 3D). This suggests that later time points of HCMV infection cause a transition of HFF cells to a non-fibroblast identity, and this transition is suppressed in the absence of macroH2A1. To explore this further, we performed a principal component analysis of the expression matrix comprising genes from Cluster 1. PC1 captures the differences between fibroblast and non-fibroblast lineages, whereas PC3 captures the differences between neuronal and non-neuronal lineages (Fig. 3E). We found PC1 and PC3 to capture the infection time course. WT mock-infected cells had similar values to IMR90 in PC1 and PC3. We observed an increase in PC1 and PC3 loadings with increasing time of infection in the direction toward neural cells. A similar trend is observed in macroH2A1 KO cells, but the starting time points (mock and 4 hpi) have much lower PC1 and PC3 loadings such that by the final time point, PC1 and PC3 values for macroH2A1 KO cells are similar to that of mock-infected WT cells. Thus, an increase in both PC1 and PC3 observed over the course of infection captures the loss of fibroblast identity and a gain of neuronal identity in WT cells. Interestingly, in macroH2A1 KO cells, the starting point is much lower in PC1 and PC3, suggesting an inability of macroH2A1 KO cells to transition from fibroblast to neuronal identity over the course of infection. In summary, our gene expression analysis highlights the profound effect of macroH2A1 on transcriptional upregulation of many host genes during HCMV infection and that this upregulation transitions infected cells away from a fibroblast expression profile and towards a neuronal expression profile.

As macroH2A1 frequently colocalizes with H3K27me3 and cluster 1 was also enriched for H3K27me3 (Sup Fig. 4D, E), we used the small molecule tazemetostat (an EZH2 inhibitor)32, to deplete H3K27me3 prior to HCMV infection. We found that although H3K27me3 depletion caused a significant reduction in titer, the reduction was modest compared to that induced by loss of macroH2A1 (Sup Fig. 5A). Furthermore, H3K27me3 depletion did not impact nuclear rearrangement or vIAC formation (Sup Fig. 5B–D). We also investigated by western blot the induction of cluster 1 gene KIF1A, a kinesin motor for axonal transport in neurons33, and found that its induction was not diminished significantly by the depletion of H3K27me3 (Sup Fig. 5E). Our results suggest that while H3K27me3 is likely also important for HCMV infection, its role on cluster 1 genes appears less significant for HCMV infection than that of macroH2A1.

Knockdown of several macroH2A1-dependent genes reduced HCMV spread and vIAC formation

We next sought to determine if the transition from a fibroblast to neuronal expression profile is essential for HCMV infectivity. Following the observation that many of the genes differentially expressed in HCMV infection between WT and macroH2A1 KO cells were associated with axon formation and neurotransmitter trafficking, we hypothesized that HCMV hijacks these pathways for progeny maturation and spread. To test this hypothesis, we designed a targeted siRNA screen selecting 12 genes with low FDRs and large fold changes in expression between WT and macroH2A1 KO cells induced by HCMV at 72 hpi.

Following infection of WT cells with HCMV tagged with GFP, we transfected siRNAs to dampen the induction of these target genes later in infection (Fig. 4A). We confirmed that all siRNA targeted transcripts were reduced by at least 50% compared to their levels at 4 dpi in the condition treated with a non-targeting control (NC) siRNA (Fig. 4B, C). We also validated that at a higher MOI of 3, selected genes in this panel still increased in a macroH2A1-dependent manner. The higher MOI therefore rules out the possibility of potential delayed induction due to a slower infection in macroH2A1 KO cells (Sup Fig. 6A–E). Upon initial infection, representative HCMV RNA and protein levels did not differ among any conditions (Sup Fig. 6G, H). This indicates viral transcription and translation were not impacted by the siRNA treatment. We used supernatants harvested from the siRNA-treated HCMV-infected cells to set up GFP foci assays and measure plaque size. We found that several siRNA knockdowns caused a reduction in GFP foci to 40–70% of control levels though these groups did not reach significance (Sup Fig 7A). Knockdown of WWC1, however, did significantly reduce GFP foci. Interestingly, we also noted that several of the knockdown conditions produced viral progeny that generated smaller plaque sizes compared to the control. To investigate this observation, we imaged crystal violet plaques and quantified the area of these plaques (Sup Fig 7B). We found that five of our target genes, IFI27, KIF1A, LAMA1, NPTX2, and WWC1, had significantly smaller plaques compared to control (Fig. 4D, E), highlighting their importance to infection. Next, we investigated whether depletion of these five targets impacted HCMV-induced cellular remodeling and vIAC formation. We found that IFI27 and KIF1A KD cells had smaller nuclei and significantly smaller vIACs compared to control. Additionally, LAMA1, NPTX2, and WWC1 KD resulted in vIACs that were malformed with either a hollow or nonspherical appearance (Sup Fig 7C–H). Taken together, our results from this screen demonstrate that cells unable to induce these genes to a high level are unable to produce viral progeny that can spread efficiently, underscoring the significance of these genes in HCMV spread.

A Schematic of targeted siRNA screen. (B) RT-qPCR quantification of RNA levels of target genes during HCMV infection. These genes include APOE, a lipoprotein associated with Alzheimer’s disease and synaptic vesicle release67,68; CNTFR, a ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor that supports motor neuron axons69; DOC2B a calcium sensor that promotes synaptic vesicle release70; ERC1, a cellular scaffolding protein71; IFI27, an interferon-induced gene expressed in the cerebellum in response to viral CNS infection72; KIF1A, a neuronal kinesin33; LAMA1, a laminin essential for neurite growth73,74; LRRC4B, a transmembrane protein that regulates synapse formation75; MYO5B, a myosin associated with polarity and axon development76; NPTX2 (formerly NARP), a small molecule released in excitatory synapses77; SOX11, a transcription factor associated with neuron development78; and WWC1, a synaptic scaffolding protein79. Knockdown of each gene is normalized to its expression in cells treated with the non-targeting control (NC) at 4 dpi. Bar graphs show mean with error bars indicating SEM. n = 3 biological replicates. P-values by unpaired t-test as follows: APOE**** p = 7.4×10−5, CNTFR* p = 1.14×10−3, ERC1* p = 3.83×10−2, IFI27* p = 1.62×10−2, KIF1A** p = 4.09×10−3, LRRC4B*** p = 9.3×10−4, MYO5B* p = 1.62×10−2, NPTX2**** p = 1.5×10−5, SOX11* p = 3.80×10−2, WWC1* p = 1.62×10−2. C Representative western blot of siRNA knockdown of KIF1A in WT cells during HCMV infection at 4 dpi compared to mock (M). Asterisk indicates a non-specific band. Tubulin is shown as loading control and pp28 is shown as infection control. D Quantification of plaque area produced from supernatant harvested from cells treated with siRNA indicated. Those that reach statistical significance are bolded. Bar graphs show mean with error bars indicating SEM. * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, *** denotes p < 0.001 by one way ANOVA with follow up Dunnett’s test as follows: NC/IFI27*** p = 9.5×10−4, NC/KIF1A* p = 2.52×10−2, NC/LAMA1* p = 4.3×10−2, NC/NPTX2** p = 8.12×10−3, NC/WWC1*** p = 3.2×10−4, and n values: NC n = 652, APOE n = 593, CNTFR n = 863, DOC2B n = 599, ERC1 n = 591, IFI27 n = 332, KIF1A n = 455, LAMA1 n = 478, LRRC4B n = 546, MYO5B n = 408, NPTX2 n = 514, SOX11 n = 651, WWC1 n = 459. E Representative images of plaque sizes for those with significant differences as indicated. Yellow dashed line frames plaque example. Scale bar indicates 150 µm.

HCMV IE1 is necessary and sufficient to drive expression of macroH2A1-dependent genes

Next, we investigated the mechanism of activation of these macroH2A1-dependent genes. HCMV immediate early protein IE1 directly binds the acidic patch on the nucleosome. This interaction is thought to be mediated by a region in its C-terminus called the chromatin-tethering domain (CTD) that specifically interacts with the host histone H2A34. Because this region of H2A and the responsible amino acids are highly conserved between canonical H2A and macroH2A135 (Fig. 5A, underlined residues), we hypothesized that HCMV IE1 may also bind macroH2A1 in this region. Further, because HCMV IE1 is sufficient to drive expression of several interferon stimulated genes36, we hypothesized that through interacting with macroH2A1, IE1 may be responsible for the activation of neuronal genes that we observed. To test this hypothesis, we co-expressed IE1 and GFP-tagged macroH2A1.1 or GFP-tagged macroH2A1.2 in 293 T cells. With GFP expression as a negative control, we pulled down the GFP tag and assayed for the presence of IE1 by western blot. We found that IE1 was only detected when either isoform of macroH2A1 was present, indicating an interaction between IE1 and macroH2A1 (Fig. 5B)

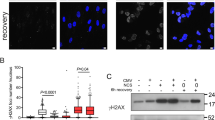

A H2A and macroH2A1 homology. Residues that facilitate binding of IE1 are in red in H2A and underlined in macroH2A1. B Co-immunoprecipitation western blot of IE1 and macroH2A1 in 293 T cells co-transfected with IE1 and GFP, macroH2A1.1-GFP, or macroH2A1.2-GFP or GFP alone as indicated. C RT-qPCR quantification of levels of IE1/2 in doxycycline (dox) inducible cell lines at 48 h normalized to luciferase (Luc). Bar graph shows mean, error bars indicate SEM. P values by one way ANOVA with follow up Dunnett’s test as follows: Luc/IE1*** p = 4.4 × 10−8, Luc/dCTD**** p = 4.6×10−8, and Luc/IE2** p = 2.4×10−7. n = 3 biological replicates. D Representative western blot of proteins in cell types upon dox addition as indicated. H3 is shown as a loading control. E Z-scores for each gene from its normalized count across cells expressing IE1, IE1ΔCTD, IE2, Luciferase, and control cells. The distribution of Z-scores for genes in cluster 1 (from Fig. 3A) are shown as a boxplot where the lower and upper hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles. Pairwise comparisons that yield p < 0.05 by Wilcoxon Rank Sum test are indicated by asterisk (*). P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Benjamini & Hochberg correction. See Methods for more details. F Volcano plot where the Log2(Fold Change) for IE1 vs. Luciferase ectopic expression is plotted against -log10(FDR). Genes with Log2(Fold Change)>1 and FDR ≤ 0.05 are in red. Genes with Log2(Fold Change)<−1 and FDR ≤ 0.05 are in blue. Neuronal genes selected for further characterization are labeled in blue. G Same as (F) for IE1ΔCTD vs. Luciferase. H Same as (F) for IE2 vs. Luciferase. I RT-qPCR quantification of RNA levels of IFI27 in WT and macroH2A1 KO cells infected with HCMV Towne or IE1-null (CR208), normalized to 18S rRNA. Bar graph shows mean with error bars indicating SEM. N = 3 biological replicates. P values by two-way ANOVA with follow up Šídák multiple comparisons test as indicated. J Same as (I) for KIF1A. K Same as (I) for LAMA1. L Same as (I) for NPTX2. M Same as (I) for WWC1.

To determine whether IE1 is sufficient to induce macroH2A1-dependent genes, we next investigated host gene expression in the presence of IE1. To do this, we expressed HCMV IE1, a mutant IE1 missing the CTD (IE1ΔCTD), or luciferase as a control using a doxycycline inducible promoter in MRC5 fibroblast cells34,36. We confirmed that doxycycline (dox) treatment drove robust expression of inducible IE1, IE1ΔCTD, or IE2 by 48 h (Fig. 5C). Further, we investigated the protein levels of KIF1A, which was robustly induced by IE1 expression but was undetectable upon expression of IE1ΔCTD (Fig. 5D).

To examine host gene expression globally, we carried out RNA-seq upon doxycycline inducible expression of IE1, IE1ΔCTD, IE2, or Luciferase in MRC5 cells. RNA-seq was performed in biological triplicate and gene expression was quantified in the same way as before. To assess if genes in cluster 1 overall have higher mRNA levels upon IE1 expression, we calculated Z-scores of the normalized count for each gene across IE1, IE1ΔCTD, IE2, Luciferase, and control untreated MRC5 cells. For cluster 1, we observed a clear trend of IE1 having significantly higher Z-scores followed by IE1ΔCTD, and IE2. Thus, IE1 partially induces the gene expression changes observed upon infection (Fig. 5E). This trend was not seen in cluster 2-4 (Sup Fig 8A–L)

We found that expression of IE1 leads to upregulation of 515 genes in cluster 1. Nine out of the 12 genes that were selected for further analysis were upregulated just upon expression of IE1 (Fig. 5F, Sup Fig 8P). IE1ΔCTD partially phenocopies IE1 with 418 genes in cluster 1 upregulated (Fig. 5G). IE2 has a much weaker effect on MRC5 gene expression, with only 136 genes in cluster 1 upregulated upon IE2 expression (Fig. 5H). Interestingly, although IE1ΔCTD expression did lead to an increase in KIF1A mRNA levels, we were unable to detect KIF1A by western blot in these cells, indicating that the lower transcript levels induced by IE1ΔCTD were not sufficient for protein expression of KIF1A.

From our analysis, it appears that macroH2A1 is required for poising genes in cluster 1 in mock conditions, and that IE1 by itself can partially induce genes in cluster 1. Thus, we next interrogated the overlap of the effects of macroH2A1 and IE1 on host gene expression. We determined the extent of overlap between genes that are upregulated in WT compared to macroH2A1 KO in the mock condition and 72hpi and genes upregulated upon expression of IE1. Of the 645 genes that were only upregulated in HCMV infected WT cells, 178 genes that were upregulated in by IE1 alone (Sup Fig 8M) and 128 were upregulated by the expression of IE1ΔCTD (Sup Fig 8N). Strikingly, only 25 were upregulated by IE2 (Sup Fig 8O). Thus, IE1 has the strongest impact on upregulation of genes in cluster 1 compared to IE1ΔCTD and IE2. Taken together, these results demonstrate that IE1 is sufficient to drive expression of a significant portion of the cluster 1 genes, likely through an interaction of the IE1 CTD with host histone macroH2A1.

To further elucidate the role of the HCMV immediate early protein IE1 in activating macroH2A1-dependent gene expression during infection, we analyzed the expression profiles of 12 neuronal genes in WT HFFs and macroH2A1 KO cells infected with either HCMV WT or the IE1-deficient mutant virus CR208 (ΔIE1)37 at an MOI of 1 for 72 h (Sup Fig 9A). Western blot analysis confirmed the absence of the IE1 protein in CR208-infected cells, while IE2 and UL44 expression levels remained intact (Sup Fig 9A). Notably, WT HCMV infection led to increased viral protein expression in macroH2A1 KO cells, whereas the CR208 mutant did not exhibit a similar pattern, suggesting that IE1 may differentially influence viral gene expression dynamics in the absence of macroH2A1. Several genes, including DOC2B, MYO5B, and NPTX2 showed a strong dependence on IE1 for their induction, with minimal upregulation observed in IE1-null-infected cells (Fig. 5I–L, Sup Fig 9A–H). In contrast, genes such as CNTFR, KIF1A, and LRRC4B (Fig. 5J, Sup Fig 9C, F) maintained partial upregulation in IE1-null-infected cells, suggesting that additional viral components beyond IE1 contribute to their activation during infection. Interestingly, IFI27, a known interferon-stimulated gene (ISG), displayed higher expression levels in IE1-null-infected cells compared to WT HCMV (Fig. 5I), consistent with the established role of IE1 as a suppressor of ISG pathways38. APOE also showed increased expression in IE1-null-infected cells (Sup Fig 9B), but rather than being an ISG, APOE is upregulated under mitochondrial stress conditions39. The absence of IE1 in CR208 may trigger such stress responses, leading to APOE upregulation. Consistent with previous findings, we did not observe significant induction of neuronal genes in macroH2A1 KO HFFs, regardless of infection with WT HCMV or CR208, highlighting the essential role of macroH2A1 in facilitating gene activation during infection. Taken together, these results indicate that IE1 is necessary to robustly induce dormant macroH2A1-dependent genes.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that human cytomegalovirus induces expression of numerous neuronal genes involved in synapse formation and neurotransmitter vesicle trafficking in a macroH2A1-dependent manner driven by viral IE1. We further showed that macroH2A1 and several of these induced neuronal genes are crucial to HCMV maturation and spread (Fig. 6). Previous reports demonstrated that the HCMV protein IE1 can directly bind the acid patch of the canonical nucleosome34,40, which is highly conserved in macroH2A141. Here, we found that IE1 is necessary and sufficient to drive expression of many macroH2A1-dependent genes, demonstrating a mechanism of action and suggesting that IE1 also binds to macroH2A1-containing nucleosomes. Importantly, because IE1 is an immediate early gene, this suggests that it is critical for the activation of macroH2A1-dependent genes to occur rapidly upon establishment of infection to promote cellular remodeling and infection success. Our findings indicate that viral reprogramming of the host cell is dependent on host chromatin-controlled changes and uncovers previously unappreciated pathway critical for HCMV infection.

Interestingly, our work supports the idea that the vIAC, while important for maturation of virions, does not play a role in the virion release. During HCMV infection the formation of the vIAC largely remodels the host cells. MacroH2A1 is important for nuclear structure integrity, as we and others have previously observed22,42,43. In macroH2A1 KO cells, we observed minimal remodeling with a largely intact ER, despite the formation of small vIACs. This suggests that cellular remodeling through macroH2A1 is essential for functional vIACs to release infectious virus. The formation of a vIAC and kidney-bean shaped nucleus was thought to be an exclusive feature of HCMV infection, however, these changes have also been observed in HSV-1 infection of neuron-like cells44. In fact, one of our identified neuronal genes important for HCMV maturation, KIF1A, a kinesin motor protein involved in axonal transport, was shown to be important for the spread of HSV-1 and pseudorabies virus (PRV)45. These observations raise an interesting question about whether HCMV hijacking of neurotransmitter trafficking pathways is a retained evolutionary feature of many viruses or a novel pathway exploited specifically by HCMV. MacroH2A1 is also highly conserved and not rapidly evolving46, suggesting that it is more likely to be HCMV that evolved to hijack this histone. Future work into the evolution of HCMV will uncover how these mechanisms of chromatin manipulation have developed.

Murine CMV was recently reported to control large scale transcriptional profiles and alter the identity of infected macrophages to escape innate immune response and increase spread47. Our work builds on this finding in HCMV, suggesting that betaherpesviruses may drive cellular reprogramming for infection spread in various cell-type specific ways. Importantly, we find primarily structural genes associated with terminal differentiation to be upregulated during HCMV infection, as opposed to developmental genes. Taken together with the recent findings on murine CMV, our work suggests that HCMV cellular reprogramming is not limited to a particular set of genes, but rather is controlled through chromatin mechanisms. Furthermore, our discovery that HCMV upregulates genes associated with synapse formation and neurotransmitter trafficking for efficient spread provides a functional context for the previous findings wherein HCMV virions resemble synaptic-like vesicles in their lipid content48.

It is important to note that these neurotransmitter pathways are dormant in uninfected fibroblast cells. Thus, there are no normal neuronal secretory functions that the virus must compete with, nor are there specific neuronal immune defenses to subvert. While limitations in available antibodies prevented us from examining more neuronal gene products by western blot, our overlapping gene set analysis has narrowed down the group of genes likely targeted by macroH2A1 from the initial ~3500 in cluster 1, to a smaller subset that is also IE1-dependent (Sup Figure 8). Taken together with our mass spectrometry analysis of virions, these results suggest that the large-scale maturation defects observed in marcoH2A1 KO-grown virus are likely driven by a combination of many macroH2A1 and IE1 controlled gene products. Nevertheless, the virions produced from macroH2A1 KO cells are able to egress out of the cell, indicating that maturation and egress are separately controlled processes. New screening methods may also uncover unknown strategies for chromatin manipulation through other factors to promote viral maturation49,50, though targeted approaches for chromatin may be required. Given our findings that HCMV induces expression of neuronal genes through chromatin manipulation, it is likely that many additional mechanisms of chromatin hijacking by viruses have yet to be uncovered.

Methods

Cells and viruses

hTERT-immortalized HFFs, and hTERT-immortalized macroH2A1 knockout HFFs generated as previously described22, were cultured using standard methods with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin as previously described51. Cells were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination.

MRC5 cells with doxycycline inducible IE1, IE1 ΔCTD, or Luciferase were a kind gift from the lab of M. Nevels and used as previously described 34,36. Briefly, cells were grown in DMEM with 10% tetracycline negative FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. Confluent plates were seeded and after 3 days, the media was changed then cells were undisturbed for 7 days. After these 7 days, 2 µg/mL doxycycline was added to plates and refreshed every 24 h. Cells were harvested at 48 h and RNA was extracted using the NEB Total RNA kit and RT-qPCR was performed as described below.

The lab-adapted strain of HCMV Towne52 was used for all experiments at an MOI of 1 unless otherwise noted. GFP-Towne53, TB40E-GFP54, or CR208 (Towne IE1-null)37 were used for experiments indicated. The IE1-deficient mutant virus CR208 was propagated in complementing HFF cells expressing IE1 as previously described37. Monolayers of cells were infected for 1 h at 37 °C as previously described55. Cells were collected at 4, 16, 24, 48,72, 96 hpi for western blot and RNA-sequencing. The supernatant was collected at 4 and 6 dpi for plaque assays. Virus stock was grown by infecting WT HFF cells at an MOI of 0.0001. The virus was harvested ∼16–20 dpi and titered on HFF cells to determine stock plaque-forming units per ml (PFU/ml). Experimental plaque assays were set up in WT HFF cells. Plaque assays were set up as serial 10-fold dilutions in serum-free DMEM. The virus was left on the cells for 1 h and then aspirated. Cells were washed with 1× PBS (pH 7.46) and 2% methylcellulose overlay in DMEM with 2% FBS, and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin was added to wells. Plaques were fixed with 0.2% crystal violet at 14 dpi and plaques were counted by hand. All plaque assays were set up with two technical replicates.

In the case of GFP-tagged viruses, foci were read at 7 dpi using the Cy-5 filter on a Typhoon Trio Imager and quantified using FIJI is Just ImageJ version 2.1.0: Java 1.8.0_172 [64-bit].

Infections with tazemetostat pretreatment

HFFs were treated with DMSO or 10 µM of tazemetostat (HY-13803; MedChem) in DMSO for 3 d prior to infection as previously described22. Cells were then infected at an MOI of 1, and after 1 h of incubation with the virus, fresh media with 10 µM tazemetostat was added to previously treated cells. Control samples were treated with equivalent volumes of DMSO. Samples were harvested as above.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described51. Briefly, cells were counted, pelleted, resuspended in 1× NuPAGE lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer (NP007; Thermo Fisher Scientific) + 5% β-mercaptoethanol at 300,000 cells per 200 µl, and boiled for 15 min. Protein lysates were separated by 13.5% SDS-PAGE gels using 1× NuPAGE MOPS buffer (NP0001; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 75 V for 30 min, then 110 V for 100 min, and then wet transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) at 100 V for 70 min using Transfer Buffer (25 mM Tris Base, 100 mM glycine, 20% methanol). Membranes were ponceau stained and imaged. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST) for 1 h and then probed with primary antibody overnight (Table 1). Membranes were washed with TBST for 30 min, incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (α-mouse or α-rabbit; 1:5,000) at room temperature for 1 h, washed with TBST for 30 min, and detected using Clarity Western ECL Substrate (1705061; Bio-Rad) and Chemidoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Images were formatted using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator.

Quantification of HCMV genomes by droplet digital (ddPCR)

Quantification was carried out as previously described22. In brief, cells were harvested at the indicated times after infection by trypsinization, washed with 1× PBS, and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 2 min. Pellets were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until processed. HCMV DNA within cells was isolated from frozen pellets using QIAamp DNAMini Kit (51304; Qiagen).

Supernatants were harvested at the indicated times after infection, centrifuged at >3500 × g, and filtered through 40 µm sterile syringe filters. DNA on the exterior of filtered capsids was digested for 1 h at 25 °C with 20.3 units DNase (79254; Qiagen) supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2. DNase was inactivated at 75 °C for 10 min followed by vortexing. Capsids were then digested with 3 mg/ml proteinase K (BP1700; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 100 mM KCl, 25 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, and 1% Igepal for 1 h at 50 °C. HCMV genomes from digested capsids were isolated using QIAamp DNAMini Kit.

A duplexed droplet digital PCR was performed to measure the levels of cellular or supernatant HCMV genomes on the QX100 droplet digital PCR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using a primer/probe set specific to HCMV UL55. Cell numbers were determined using a primer/probe set specific to human Beta-globin, a reference gene that exists at two copies per cell. The ddPCR reaction mixture consisted of 12.5 µl of a 2× ddPCR Supermix for Probes no dUTP (1863024; Bio-Rad), 1.25 µl of each 20× primer-probe mix (Table 2), and 10 µl of template DNA. 20 µl of each reaction mixture was loaded onto a disposable plastic cartridge (1864008; Bio-Rad) with 70 µl of droplet generation oil (1863005; Bio-Rad) and placed in the droplet generator (Bio-Rad). Droplets generated were transferred to a 96-well PCR plate (12001925; Bio-Rad), and PCR amplification was performed on a Bio-Rad C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler with the following conditions: 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, and 60 °C for 1 min, followed by 98 °C for 10 min, and ending at 4 °C. After amplification, the plate was loaded onto the droplet reader (QX200; Bio-Rad) and the droplets from each well of the plate were automatically read with droplet reader oil (186–3004; Bio-Rad) at a rate of 32 wells per hour. Data were analyzed with QuantaSoft analysis software and the quantitation of target molecules presented as copies per microliter of the PCR reaction. HCMV genome values were standardized to cellular β-globin levels. Experiments were completed in biological triplicate and statistical analysis was performed as indicated in figure legends using Prism v10 (GraphPad Software).

Preparation of purified viral particles for mass spectrometry analysis

All chemicals used for preparation of mass spectrometry samples were of at least sequencing grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO), unless otherwise stated. The sucrose cushion purified HCMV viral particles were lysed in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer, pH 8.5 by tip-probe sonication on ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was used for further analysis. The 1% SDS detergent and lipids were removed from samples prior mass spectrometry analysis by precipitation using chloroform (CHCl3)-methanol (MeOH) precipitation56. The protein pellet from CHCl3-MeOH precipitation was resuspended in 6 M urea and 2 M thiourea in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0. Protein concentration was determined using Bradford assay kit (ThermoScientific) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Protein reduction was carried out using 10 mM DTT for 1 h at room temperature followed by alkylation with 30 mM iodoacetamide in the dark at room temperature for 40 min. After alkylation, proteins were digested first with endopeptidase Lys-C (Wako, mass spectrometry grade) for 3 h, after which the solution was diluted 10 times with 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0. Subsequently, samples were digested with trypsin (Promega) at an enzyme to substrate ratio of approximately 1:50 for 12 h at room temperature. The samples were acidified with 5% formic acid (FA) to a pH ≤ 3 and desalted using Poros Oligo R3 RP columns (PerSeptive Biosystems) packed in a P200 stage tip with C18 3 M plug (3 M Bioanalytical Technologies). Purified peptide samples were dried by lyophilization and stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Due to challenges in obtaining a sufficient amount of purified viral material, proteomic analysis was conducted using a single biological replicate per condition. To enhance analytical reproducibility and increase proteome coverage, the sample was divided into three technical replicates, each processed independently through the entire MS sample preparation workflow and analyzed by separate LC-MS injections (n = 3 technical replicates per condition). While the absence of biological replicates limited statistical analysis, technical reproducibility was evaluated across these replicates using the coefficient of variation (CV) to confirm the consistency of protein identification (Sup Data 1).

Enzymatic deglycosylation

Tryptic peptides were resuspended in 100 µl of 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH = 7.5 before adding 500 U PNGase F (NewEngland Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) for 12 h at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by acidification using 1% final concentration of formic acid and the peptides desalted as described above.

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Samples were dissolved in buffer A (0.1% formic acid; FA) and analyzed using an LC-MS/MS system consisting of an Ekspert NanoLC 425 chromatograph (Eksigent, Redwood City, CA, USA) coupled to an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). The samples were separated on a 30 cm fused silica capillary analytical column (75 µm ID). All columns were homemade and packed with ReproSil-Pur C18 AQ 3 μm reversed-phase material (Dr. Maisch, Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany). The peptides were eluted using 120 min gradients from buffer B (100% Acetonitrile (ACN), 0.1% FA) and introduced into the MS instrument via nano-electrospray. A full MS scan in the mass area of 300–1200 Da was performed in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 120,000 FWHM (200 m/z), an AGC target value of 1×106, and a maximum injection time of 100 ms. For each full scan, the settings for the higher energy collision dissociation (HCD) were as follows: AGC target value of 5×104, maximum injection time of 22 ms, isolation window of 1.6 m/z, normalized collision energy of 30, and a dynamic exclusion window of 60 s. Raw MS files were analyzed by PEAKS Studio (v11.5) software platform (Bioinformatics Solutions Inc). MS/MS spectra were searched against the UniProt-human and HCMV (Towne) database (Version January 2024, 20,585 entries). For all searches, MS1 and HCD MS2 mass tolerances were set to 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively. Cysteine carbamidomethylation was set as fixed, while methionine oxidation and acetylation (protein N-term) were set as variable modifications, with a maximum of two variable modifications per peptide. Only peptides containing 6–45 residues and up to 2 missed trypsin cleavages were considered. Each protein quantification value was log2 transformed and subsequently normalized by the HCMV MCP (UL86) protein abundance within each run. Cellular Component association analysis was performed using the STRING database (v12.0) with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 1%. Each GO term was ranked based on the STRING strength score (represents the confidence level of functional associations between proteins or gene ontology (GO) terms, derived from integrated evidence sources such as experimental data, text mining, co-expression, and curated databases, with higher scores indicating stronger enrichment or interaction reliability57.

RNA sequencing

Three biological replicates per time point were obtained from independent infections. Cells were harvested at the indicated times after infection by trypsinization, washed with PBS, and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 2 min. RNA was harvested using New England BioLabs Monarch® Total RNA Miniprep Kit (T2010S) as per kit instructions.

RNA was quantified by Nanodrop and integrity was analyzed with the 4200 Tapestation Bioanalyzer system (Agilent). 500 ng of total RNA with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 9.5 were used to prepare sequencing libraries with the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (20020594; Illumina). Library concentrations were measured with Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Q32854; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then analyzed with Agilent High Sensitivity D5000 ScreenTape System and pooled. Libraries were sequenced with 100-bp paired-end reads on an Illumina NextSeq 2000 sequencer at the Fred Hutch Genomics Core Facility.

RNA-seq analysis

A concatenated fasta file was created using cDNA sequences from release 110 of Ensembl for the human genome and Towne-HCMV genome generated from sequencing map in Murphy et al. 200359 and genbank sequences, which was then used to construct a Salmon index60. Expression for each transcript was quantified from raw reads using Salmon v1.9 with libType set as automatic. DESeq261 (v1.30.1) in R (v4.0.3) was used first to perform all pairwise comparisons for WT and macroH2A1 KO both across time points and between the two genotypes. There were six time points each in biological triplicates, resulting in 36 datasets: six time points compared against each other for each genotype (15 × 2) and six time points compared between WT and macroH2A1 KO (6) A superset of genes was made by combining lists of genes with adjusted p-value ≤0.05 from each comparison. The expression matrix across genotypes and time points was transformed using the “rlog” function in DESeq2, and then the expression values for the superset of genes were extracted. The normalized read count for each gene was averaged across replicates, Z-transformed across time points and genotypes, and then the matrix of Z-scores was subjected to k-means clustering (k = 4). Raw reads for ENCODE datasets were obtained and quantified with Salmon in the same manner as the CMV samples. CMV samples and ENCODE samples were loaded together in DESeq2 as a single DESeq dataset and transformed using the “rlog” function. Normalized expression values for genes in cluster 1 were then extracted to plot the distance matrix and principal components. The distance matrix was calculated using the “dist” function in R and plotted using the pheatmap package. Principal component analysis was performed using the “prcomp” function in R and plotted using ggplot2. GO enrichment analysis was performed with WebGestalt62. MacroH2A1 and H3K27me3 enrichment at genes from different clusters were performed using published data for WT and macroH2A1 KO HFF cells. Enrichment was calculated across the whole gene (Gene start and Gene end definitions from Ensembl). In all boxplots presented, the lower and upper hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles. The upper whisker extends from the hinge to the largest value no further than 1.5xIQR (IQR - inter-quartile range). The lower whisker extends from the hinge to the smallest value at most 1.5xIQR of the hinge. Data beyond the ends of whiskers are “outliers” and individually plotted. In a notched boxplot, the notches extend 1.58xIQR/sqrt(n). This gives roughly a 95% confidence interval for comparing medians.

Targeted siRNA screen

HFFs were plated in 6-well plates and infected at MOI of 1 with HCMV-GFP Towne as described. Cells were transfected at 12 and 24 h post infection with 25 pmol/well siRNA (Silencer select, Ambion distributed by Thermo Fisher) (Table 3) using lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher). Non-targeting “Negative Control #1” (Cat. 4390843) was used as siRNA control. At 4 days post infection, supernatants were collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for GFP-foci and plaque assay. Cells were pelleted and split, 75:25 for protein lysate and RNA respectively. Cells for protein lysate were lysed as previously described. Cell pellets for RNA extraction were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

RT-qPCR

RNA was extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen) and cDNA was generated using Iscript Reverse Transcription kit (Bio-Rad). RT-qPCR was performed using a CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) and iTaq Universal SYBR Green One-Step kit (Bio-Rad). Primers for RT-qPCR are described in Table 3.

Immunofluorescence

As previously described8, in brief: Cells were plated on poly-L coated glass coverslips the day prior to infection. Cells were then infected with HCMV at an MOI of 1 and collected at 72 hpi. For harvest, cells were fixed with cold 4% PFA in 1× PBS for 15 min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X in 1× PBS for 15 min, then blocked in 10% human serum in 1× PBS for 1 h, incubated with primary antibody (diluted as noted in Table 1) in 10% human sera in 1× PBS for 1 h. Slides were incubated with secondary antibodies at a dilution of 1:300 in 3% BSA in 1× PBS for 1 h. Coverslips were fixed to microscope slides with Invitrogen ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant or Vectashield (Tubulin stain). Images were taken on Leica Stellaris Confocal with 63× oil objective at room temperature. Images were formatted using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator.

Images were analyzed using Bitplane Imaris v9.1.1. Labeled nuclei and vIACs were segmented using the Surfaces tool on DAPI and pp28 stains respectively, and average volumes, sphericity and mean fluorescence intensities were reported for each field.

Co-Immunoprecipitation

10 cm plates of 293 T cells were transfected with 2 µg IE-163 and 2 µg GFP control, mH2A1.1-CT-GFP, or mH2A1.2-CT-GFP64 using Attractene transfection reagent. After 48 hours cells were harvested and lysed in “EA buffer” (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4,110 mM KOAc, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20, 0.5% Triton-X 100, 200 mM NaCl, 1 Pierce™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Mini Tablets added fresh to 10 mL buffer). 2 µg of protein lysate was incubated with 20 µL of GFP-Catcher magnetic beads (Antibodies Online) for 1 hr at 4 °C. Beads were then washed 3 times with EA buffer. Protein was eluted from beads in 40 µL of 1X LDS Sample Buffer incubating at 95 °C for 15 min. Samples were then analyzed by WB as above.

Plaque area quantification

Once plaque assays were fixed (as per Cells and Virus section), plates were imaged on a Molecular Devices ImageXpress Micro high-content imaging system equipped with a Nikon 4x/0.2 Plan Apo objective. To provide a quantitative measurement of staining intensity, we acquired fluorescence images with a Cy5 (647 nm excitation) filter set. Twenty-four overlapping fields were imaged per well, providing 73% coverage of the total well area.

Using FIJI is Just ImageJ version 2.1.0: Java 1.8.0_172 [64-bit] threshold was set to top 8% of pixel intensity (to account for well-to-well variation in crystal violet staining). The image was converted to binary and “analyze particles” feature was used to acquire area for particles over 1000 pixel units squared (Sup Figure 7B).

We also acquired transmitted light images of selected samples on a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope equipped with a Nikon 4x/0.2 Plan Apo objective. Images were acquired on a Photometrics Prime BSI Express sCMOS camera through an orange (580-610 nm) filter. This wavelength range was chosen to match the absorbance spectrum of crystal violet, thus maximizing staining contrast and ensuring high dynamic range.

Electron microscopy

Cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) at 4 °C. Fixed cells were rinsed briefly in 1% sucrose in 50 mM cacodylate (pH 7.2), then postfixed on ice for 30 min in a solution of 1% osmium tetroxide (RT19152; EM Sciences) and 0.8% potassium ferricyanide in 50 mM cacodylate (pH 7.2). Cell pellets were washed twice briefly at 25 °C in 1% sucrose in 50 mM cacodylate (pH 7.2) and then washed in three changes of 50 mM cacodylate (pH 7.2) for 5 min each. Cell pellets were treated with 0.2% tannic acid (1401-55-4; Sigma-Aldrich) in 50 mM cacodylate (pH 7.2) for 15 min at 25 °C and then rinsed several times in water. Cells were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and embedded in Epon 12 resin (18010; Ted Pella). 70 nm thin sections were cut using an Ultracut UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica Mikrosysteme) and collected on 200 mesh formvar/carbon coated copper grids (01800; Ted Pella). Sections were stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate and Reynolds lead citrate. Cell pellet sections were imaged using a Talos L120C microscope operated at 120 kV with a Ceta-16 M (4,096 × 4,096) camera (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

All data were collected at spot size 5 with a 100-µm C2 aperture and 70-µm objective aperture. Images were formatted using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator.

Image analysis was done using FIJI is Just ImageJ version 2.1.0: Java 1.8.0_172 [64-bit]. For analysis 2.5 micron by 2.5 micron grids were drawn on non-overlapping regions of cytosol. “Freehand line tool” was used to trace all lengths of ER in the field of view and length of line was measured with ImageJ “Measure” function (Sup Fig. 2D). Macro code for vIAC subcompartments can be found at: https://zenodo.org/records/15770354 (Sup Fig. 2F).

Statistical analysis

Graphs were generated and statistical analysis were run as marked in figure legends using GraphPad Prism v 9.1.2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

RNA-sequencing data can be found at GSE272267 and GSE291064. Mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository58 with the dataset identifier PXD061284 or at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD061284. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Macro code for quantifying vIAC subcompartments can be found at: https://zenodo.org/records/15770354.

References

Cannon, M. J., Schmid, D. S. & Hyde, T. B. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev. Méd. Virol. 20, 202–213 (2010).

Fowler, K. et al. A systematic literature review of the global seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus: possible implications for treatment, screening, and vaccine development. BMC Public Heal 22, 1659 (2022).

Zanghellini, F., Boppana, S. B., Emery, V. C., Griffiths, P. D. & Pass, R. F. Asymptomatic Primary Cytomegalovirus Infection: Virologic and Immunologic Features. J. Infect. Dis. 180, 702–707 (1999).

Manicklal, S., Emery, V. C., Lazzarotto, T., Boppana, S. B. & Gupta, R. K. The “Silent” Global Burden of Congenital Cytomegalovirus. Clin. Microbiol Rev. 26, 86–102 (2013).

Azevedo, L. S. et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients. Clinics 70, 515–523 (2015).

Christensen-Quick, A., Vanpouille, C., Lisco, A. & Gianella, S. Cytomegalovirus and HIV Persistence: Pouring Gas on the Fire. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 33, S-23–S-30 (2017).

Alwine, J. C. The Human Cytomegalovirus Assembly Compartment: A Masterpiece of Viral Manipulation of Cellular Processes That Facilitates Assembly and Egress. Plos Pathog. 8, e1002878 (2012).

Procter, D. J., Furey, C., Garza-Gongora, A. G., Kosak, S. T. & Walsh, D. Cytoplasmic control of intranuclear polarity by human cytomegalovirus. Nature 587, 109–114 (2020).

Procter, D. J. et al. The HCMV Assembly Compartment Is a Dynamic Golgi-Derived MTOC that Controls Nuclear Rotation and Virus Spread. Dev. Cell 45, 83–100.e7 (2018).

Tandon, R. & Mocarski, E. S. Viral and host control of cytomegalovirus maturation. Trends Microbiol 20, 392–401 (2012).

Severi, B., Landini, M. P. & Govoni, E. Human Cytomegalovirus morphogenesis: an ultrastructural study of the late cytoplasmic phases. Arch. Virol. 98, 51–64 (1988).

Pignatelli, S. et al. Cytomegalovirus Primary Envelopment at Large Nuclear Membrane Infoldings: What’s New? J. Virol. 81, 7320–7322 (2007).

Tooze, J., Hollinshead, M., Reis, B., Radsak, K. & Kern, H. Progeny vaccinia and human cytomegalovirus particles utilize early endosomal cisternae for their envelopes. Eur. J. cell Biol. 60, 163–178 (1993).

Walsh, D., Perez, C., Notary, J. & Mohr, I. Regulation of the Translation Initiation Factor eIF4F by Multiple Mechanisms in Human Cytomegalovirus-Infected Cells. J. Virol. 79, 8057–8064 (2005).

Jenuwein, T. & Allis, C. D. Translating the Histone Code. Science 293, 1074–1080 (2001).

Lee, J.-S., Smith, E. & Shilatifard, A. The Language of Histone Crosstalk. Cell 142, 682–685 (2010).

Talbert, P. B. & Henikoff, S. Histone variants at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 134, jcs244749 (2021).

Costanzi, C. & Pehrson, J. R. Histone macroH2A1 is concentrated in the inactive X chromosome of female mammals. Nature 393, 599–601 (1998).

Gamble, M. J., Frizzell, K. M., Yang, C., Krishnakumar, R. & Kraus, W. L. The histone variant macroH2A1 marks repressed autosomal chromatin, but protects a subset of its target genes from silencing. Gene Dev. 24, 21–32 (2010).

Dell’Orso, S. et al. The Histone Variant MacroH2A1.2 Is Necessary for the Activation of Muscle Enhancers and Recruitment of the Transcription Factor Pbx1. Cell Rep. 14, 1156–1168 (2016).

Ma, H. et al. MacroH2A1.2 deficiency leads to neural stem cell differentiation defects and autism-like behaviors. EMBO Rep. 22, e52150 (2021).

Lewis, H. C. et al. HSV-1 exploits host heterochromatin for nuclear egress. J. Cell Biol. 222, e202304106 (2023).

Albright, E. R. et al. Human cytomegalovirus lytic infection inhibits replication-dependent histone synthesis and requires stem loop binding protein function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2122174119 (2022).

Craighead, J. E., Kanich, R. E. & Almeida, J. D. Nonviral Microbodies with Viral Antigenicity Produced in Cytomegalovirus-Infected Cells. J. Virol. 10, 766–775 (1972).

Pepperl, S., Münster, J., Mach, M., Harris, J. R. & Plachter, B. Dense Bodies of Human Cytomegalovirus Induce both Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses in the Absence of Viral Gene Expression. J. Virol. 74, 6132–6146 (2000).

Büscher, N., Paulus, C., Nevels, M., Tenzer, S. & Plachter, B. The proteome of human cytomegalovirus virions and dense bodies is conserved across different strains. Méd. Microbiol. Immunol. 204, 285–293 (2015).

Shenk, T. & Alwine, J. C. Human Cytomegalovirus: Coordinating Cellular Stress, Signaling, and Metabolic Pathways. Virol 1, 355–374 (2014).

Chaurushiya, M. S. & Weitzman, M. D. Viral manipulation of DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoints. DNA Repair 8, 1166–1176 (2009).

Smolarz, B., Wilczyński, J. & Nowakowska, D. DNA repair mechanisms and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection. Folia Microbiol 60, 199–209 (2015).

Dunham, I. et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74 (2012).

Luo, Y. et al. New developments on the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) data portal. Nucleic Acids Res 48, D882–D889 (2019).

Lue, J. K. & Amengual, J. E. Emerging EZH2 Inhibitors and Their Application in Lymphoma. Curr. Hematol. Malig. R. 13, 369–382 (2018).

Kondo, M., Takei, Y. & Hirokawa, N. Motor Protein KIF1A Is Essential for Hippocampal Synaptogenesis and Learning Enhancement in an Enriched Environment. Neuron 73, 743–757 (2012).

Mücke, K. et al. Human Cytomegalovirus Major Immediate Early 1 Protein Targets Host Chromosomes by Docking to the Acidic Pocket on the Nucleosome Surface. J. Virol. 88, 1228–1248 (2014).

Chakravarthy, S. et al. Structural Characterization of the Histone Variant macroH2A. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 7616–7624 (2005).

Knoblach, T., Grandel, B., Seiler, J., Nevels, M. & Paulus, C. Human Cytomegalovirus IE1 Protein Elicits a Type II Interferon-Like Host Cell Response That Depends on Activated STAT1 but Not Interferon-γ. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002016 (2011).

Greaves, R. F. & Mocarski, E. S. Defective Growth Correlates with Reduced Accumulation of a Viral DNA Replication Protein after Low-Multiplicity Infection by a Human Cytomegalovirus ie1 Mutant. J. Virol. 72, 366–379 (1998).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Consecutive Inhibition of ISG15 Expression and ISGylation by Cytomegalovirus Regulators. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005850 (2016).

Wynne, M. E. et al. APOE expression and secretion are modulated by mitochondrial dysfunction. eLife 12, e85779 (2023).

Nitzsche, A., Paulus, C. & Nevels, M. Temporal Dynamics of Cytomegalovirus Chromatin Assembly in Productively Infected Human Cells. J. Virol. 82, 11167–11180 (2008).

Luger, K., Mäder, A. W., Richmond, R. K., Sargent, D. F. & Richmond, T. J. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature 389, 251–260 (1997).

Douet, J. et al. MacroH2A histone variants maintain nuclear organization and heterochromatin architecture. J. Cell Sci. 130, 1570–1582 (2017).

Kozlowski, M. et al. MacroH2A histone variants limit chromatin plasticity through two distinct mechanisms. Embo Rep. 19, e44445 (2018).

White, S., Kawano, H., Harata, N. C. & Roller, R. J. Herpes Simplex Virus Organizes Cytoplasmic Membranes To Form a Viral Assembly Center in Neuronal Cells. J. Virol. 94, e00900–20 (2020).

Scherer, J. et al. A kinesin-3 recruitment complex facilitates axonal sorting of enveloped alpha herpesvirus capsids. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1007985 (2020).

Guberovic, I., Farkas, M., Corujo, D. & Buschbeck, M. Evolution, structure and function of divergent macroH2A1 splice isoforms. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 135, 43–49 (2023).

Baasch, S. et al. Cytomegalovirus subverts macrophage identity. Cell 184, 3774–3793.e25 (2021).

Liu, S. T. H. et al. Synaptic vesicle-like lipidome of human cytomegalovirus virions reveals a role for SNARE machinery in virion egress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 108, 12869–12874 (2011).

Finkel, Y. et al. A virally encoded high-resolution screen of cytomegalovirus dependencies. Nature 1–8 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07503-z (2024).

Moreno, I., Rodríguez-Sánchez, I., Schafer, X. & Munger, J. Human cytomegalovirus induces neuronal enolase to support virally mediated metabolic remodeling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2205789119 (2022).

Lynch, K. L. et al. A viral histone-like protein exploits antagonism between linker histones and HMGB proteins to obstruct the cell cycle. Curr. Biol. 31, 5227–5237.e7 (2021).

Kemble, G., Duke, G., Winter, R. & Spaete, R. Defined large-scale alterations of the human cytomegalovirus genome constructed by cotransfection of overlapping cosmids. J. Virol. 70, 2044–2048 (1996).

Marchini, A., Liu, H. & Zhu, H. Human Cytomegalovirus with IE-2 (UL122) Deleted Fails To Express Early Lytic Genes. J. Virol. 75, 1870–1878 (2001).

Sampaio, K. L., Cavignac, Y., Stierhof, Y.-D. & Sinzger, C. Human Cytomegalovirus Labeled with Green Fluorescent Protein for Live Analysis of Intracellular Particle Movements. J. Virol. 79, 2754–2767 (2005).

Kim, E. T. et al. SAMHD1 Modulates Early Steps during Human Cytomegalovirus Infection by Limiting NF-κB Activation. Cell Rep. 28, 434–448.e6 (2019).

Wessel, D. & Flügge, U. I. A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal. Biochem. 138, 141–143 (1984).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D605–D612 (2020).

Vizcaíno, J. A. et al. The Proteomics Identifications (PRIDE) database and associated tools: status in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 41, D1063–D1069 (2012).

Murphy, E. et al. Coding potential of laboratory and clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 100, 14976–14981 (2003).

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Liao, Y., Wang, J., Jaehnig, E. J. & Shi, Z. & Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2019: gene set analysis toolkit with revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Res 47, W199–W205 (2019).

Biegalke, B. J. & Geballe, A. P. Sequence requirements for activation of the HIV-1 LTR by human cytomegalovirus. Virology 183, 381–385 (1991).

Chadwick, B. P. & Willard, H. F. Histone H2A variants and the inactive X chromosome: identification of a second macroH2A variant. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 1101–1113 (2001).

Lee, E.-G. et al. Redefining transcriptional regulation of the APOE gene and its association with Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 15, e0227667 (2020).

Arend, K. C., Ziehr, B., Vincent, H. A. & Moorman, N. J. Multiple Transcripts Encode Full-Length Human Cytomegalovirus IE1 and IE2 Proteins during Lytic Infection. J. Virol. 90, 8855–8865 (2016).

Lane-Donovan, C. & Herz, J. ApoE, ApoE Receptors, and the Synapse in Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 28, 273–284 (2017).

Dumanis, S. B., DiBattista, A. M., Miessau, M. & Moussa, C. E. H. & Rebeck, G. W. APOE genotype affects the pre-synaptic compartment of glutamatergic nerve terminals. J. Neurochem. 124, 4–14 (2013).

DeChiara, T. M. et al. Mice lacking the CNTF receptor, unlike mice lacking CNTF, exhibit profound motor neuron deficits at birth. Cell 83, 313–322 (1995).

Groffen, A. J. et al. Doc2b Is a High-Affinity Ca2+ Sensor for Spontaneous Neurotransmitter Release. Science 327, 1614–1618 (2010).

Sala, K., et al. The ERC1 scaffold protein implicated in cell motility drives the assembly of a liquid phase. Sci. Rep. 9, 13530 (2019).

Lucas, T. M., Richner, J. M. & Diamond, M. S. The Interferon-Stimulated Gene Ifi27l2a Restricts West Nile Virus Infection and Pathogenesis in a Cell-Type- and Region-Specific Manner. J. Virol. 90, 2600–2615 (2016).

Ichikawa-Tomikawa, N. et al. Laminin α1 is essential for mouse cerebellar development. Matrix Biol. 31, 17–28 (2012).

Flanagan, L. A., Rebaza, L. M., Derzic, S., Schwartz, P. H. & Monuki, E. S. Regulation of human neural precursor cells by laminin and integrins. J. Neurosci. Res. 83, 845–856 (2006).

Kim, S. et al. NGL family PSD-95–interacting adhesion molecules regulate excitatory synapse formation. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1294–1301 (2006).

Liu, Y., et al. Myosin Vb controls biogenesis of post-Golgi Rab10 carriers during axon development. Nat. Commun. 4, 2005 (2013).

Chang, M. C. et al. Narp regulates homeostatic scaling of excitatory synapses on parvalbumin-expressing interneurons. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1090–1097 (2010).

Bergsland, M., Werme, M., Malewicz, M., Perlmann, T. & Muhr, J. The establishment of neuronal properties is controlled by Sox4 and Sox11. Genes Dev. 20, 3475–3486 (2006).

Ji, Z. et al. Kibra Modulates Learning and Memory via Binding to Dendrin. Cell Rep. 26, 2064–2077.e7 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Avgousti lab, M. Lagunoff, S. Parkhurst, S. Tapscott, L. Goo and M. Weitzman for their insightful comments. We thank the Electron Microscopy (EMSR), and Genomics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource Facilities at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center for help with sequencing and data analysis. We thank H. West-Foyle, L. Schroeder, and the Cellular Imaging Shared Resource (CISR) for their help with image analysis. We thank E. S. Mocarski for providing the CR208 virus to Jin-Hyun Ahn. We also thank A. Kentsis for the mass spectrometry resources. This research was supported by the Electron Microscopy Shared Resource, RRID:SCR_022611. The EMSR, CISR, and Genomics core are supported in part by the Fred Hutch/University of Washington Cancer Consortium (P30 CA015704). This study was also supported by start-up funds from the RNA Bioscience Initiative at the University of Colorado School of Medicine (S. Ramachandran), the Fred Hutch and the University of Miami (D.C. Avgousti), National Institutes of Health funding to J.R.S. (AI007509) E.A. Arnold (AI083203), A.P. Geballe (AI145945), S. Ramachandran (GM133434), and D.C. Avgousti (GM133441), the University of Washington Magnuson Scholarship to L.E. Kelnhofer-Millevolte, and National Research Foundation of Korea under grants funded by the Korean Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2024-00352590) and the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00270936) to E. T. Kim.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.E.K.M.- Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing- Original Draft, Writing- Review and Editing, Visualization, Supervision. J.R.S.- Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing- Review and Editing, Visualization. D.H.N.- Investigation, Data Curation, Writing- Review and Editing, Visualization. L.S.W.- Investigation, Data Curation, Writing- Review and Editing. HCL- Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing- Review and Editing. E.A.A.- Investigation, Writing- Review and Editing. M.R.B.- Investigation, Writing- Review and Editing. K.S.- Investigation, Data Curation. J.H.A.- Investigation, Resources, Supervision. E.T.K.- Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Review and Editing, Resources, Supervision. K.K.- Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Review and Editing, Resources, Supervision. A.P.G.- Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Review and Editing, Resources, Supervision. S.R.- Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, Data Curation, Writing- Original Draft, Writing- Review and Editing, Visualization, Supervision. D.C.A.- Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing- Original Draft, Writing- Review and Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions