Abstract

Heat barrier, the unrestricted increase in airplane or rocket speeds caused by aerodynamic heating, which—without adequate provisions for cooling the exposed surfaces—can lead to the loss of a hypersonic vehicle’s reusability, maneuverability, and cost-effectiveness. To date, indirect thermal protection methods, such as regenerative cooling, film cooling, and transpiration cooling, have proven to be complex and inefficient. Here, we propose a direct liquid cooling system to mitigate the heat barrier, utilizing a blunt-sharp structured thermal armor (STA)—a recently proposed material [36] to elevate the Leidenfrost point. The fiber-metal nano-/micro-STA withstands rigorous simulated hypersonic aerodynamic heating using butane and acetylene flames, ensuring effective temperature management in scenarios where flame temperatures reach up to 3000 °C—far exceeding the melting point of the STA substrate. Systematic cycling and durability tests further confirm the STA’s exceptional tolerance and robustness under extreme conditions. This work offers an efficient thermal protection method for hypersonic vehicles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the mid-20th century, humans overcame the sound barrier through the introduction of jet aero-engines and aerodynamic design. Since then, humanity has always struggled to overcome the heat barrier. This term refers to the extreme heat experienced by a hypersonic aircraft or spacecraft when it travels at a high speed (Mach number Ma >51,2) through the Earth’s atmosphere as shown in Fig. 1a or when re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere as shown in Fig. 1b. This is due to the aerodynamic heating effect, where friction between the air and the vehicle’s surface generates significant heat, resulting in very high temperatures. The stagnation temperature of the hypersonic vehicle’s nose reaches above 1300 °C when the vehicle travels at Ma of above 53. The temperature increases exponentially to around 2500 °C when it operates at Ma of 7. In addition, high temperatures (above 2000 °C) are also generated in the hypersonic vehicle’s scramjet and combustion chamber4. During the past two decades, there have been many ongoing projects aimed at developing hypersonic vehicles capable of reaching Ma of 20 where such high temperatures far exceed the long-term endurance of current aviation materials5. It can cause the disintegration of the aircraft, posing catastrophes to the safety of the aircraft and internal personnel. For instance, The Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere due to the penetration of hot atmospheric gases.

To date, the challenges associated with the heat barrier have not been fully resolved, thereby preventing the realization of sustained hypersonic flight. The NASA X-43, an experimental hypersonic aircraft, reached approximately Ma of 9.6 for only 10 seconds in November 20046. A relatively long duration of hypersonic flight was achieved by the Boeing X-51 Waverider7 in 2013. It maintained a Ma of 5.1 for approximately 210 seconds. Despite recent claims of successful hypersonic vehicle tests, such as the USA’s AGM-183A8 and Russia’s Zircon9, none have managed to achieve sustained hypersonic flight. This is primarily due to the extreme temperatures generated during flight, which can easily cause the vehicle to disintegrate. Due to safety concerns, no current hypersonic vehicles are capable of accommodating human occupants, despite the ongoing priority to develop manned hypersonic vehicles.

The thermal protection system (TPS) of a vehicle is engineered to absorb and dissipate extreme heat during hypersonic flight, thereby safeguarding the vehicle from overheating. This complex system utilizes both passive and active thermal protection strategies. Passive strategies encompass ablative heat shields10,11, thermal insulating materials12,13,14, and heat-resistant composites15,16,17, aerogel materials18, while active strategies include regenerative cooling19, film cooling20, and transpiration cooling21,22. Ablative heat shields, conceived in the 1960s, are the most mature thermal protection technology among passive strategies. However, as reusability, maneuverability, and cost-effectiveness become increasingly important in the development of hypersonic vehicles2, ablative heat shields are becoming less favorable. Other passive thermal protection strategies, such as insulating and heat-resistant materials, are still at the research and development stage. These materials are also of interest for high-temperature battery applications and electronic thermal management systems23,24,25 to prevent thermal runaway26,27. However, no significant breakthroughs have yet been achieved in the battery thermal management field, and even fewer advancements have been made in the hypersonic vehicle thermal protection field, which impose more stringent requirements in terms of temperature tolerance, durability, weight, complexity, and safety.

Active cooling strategies are more promising, but the current methods (regenerative, film, and transpiration cooling) can only be classified as indirect cooling methods, which have drawbacks such as heavy and complex cooling structures, low cooling efficiency, coolant waste, fuel coking, and deposition28,29. Direct liquid phase-change cooling, such as spray cooling30,31, microchannel cooling32, and jet cooling33, is believed to be impossible under such extreme thermal conditions due to the occurrence of the Leidenfrost effect34. This phenomenon frequently occurs when liquids come into contact with a hot surface exceeding 150 °C35 where a continuous vapor film is formed between the cold liquid and hot surface, impeding efficient heat dissipation. The main reason direct cooling strategies are seldom applied to the TPS of supersonic vehicles is that the Leidenfrost effect significantly reduces cooling efficiency when the aircraft skin is exposed to extremely high temperatures. Delaying the Leidenfrost point is crucial to adopting direct cooling and achieving efficient cooling for sustained hypersonic flight under aerodynamic heating conditions.

Most recently, Jiang et al. reported a hybrid nano-/micro-structured surface, known as the fiber-metal-based structured thermal armor (STA)36, that can elevate the Leidenfrost point to above 1000 °C, showing great application potential in the TPS of hypersonic vehicles. However, no related follow-up studies have been reported to date. Herein, based on our recent work37, we further optimized the surface with rougher structures, which improves liquid spreading and enhances nucleate boiling heat transfer. Adopting recognized ground-based aerodynamic heating simulation technology (above 3000 °C) on existing hypersonic blunt structures, we experimentally demonstrate the material’s exclusive advantage in aerospace thermal protection. Durability, tolerance, cycling, and mechanical property tests were also implemented to manifest its great potential in practical aerospace industries. Meanwhile, material failure mechanism and corresponding mitigation approaches are offered. Inspired by Jiang et al.’s solution36, this paper shows the STA’s huge application potential in hypersonic vehicle industries, promoting the development of reusable light-weight aerospace TPSs.

Results

Material design and characterization for butane flame experiments

The STA employed is a multi-textured composite incorporating a metal-based micro-pillared substrate and an embedded super-hydrophilic porous fiber membrane, as depicted in the schematics of Fig. 2a. Two holes on either side of the substrate (Fig. 2a, b) allow for the insertion of thermocouples to measure the temperature at the substrate’s center region. The protruding edge facilitates clamping the STA in thermal experiments. SEM images (Fig. 2c) validate the width (a = 300 µm) and spacing (b = 300 µm) of the pillars and reveal U-shape structures between pillars. Such a design enables the Leidenfrost delay38. Compared to Jiang et al.‘s work36, our pillar surfaces are rougher with Rmax = 2.13 µm and Ra = 0.158 µm (Supplementary Note 1), increasing surface energy and wettability37,39,40, while providing more nano-scale nucleation sites41, and thus, enhancing two-phase boiling heat transfer. Figure 2d displays the digital image of the fabricated STA, with its SEM characterization in Fig. 2e, showing the well-embedded SiO2 nanofibrous membrane. Figure 2f presents multi-scale magnified SEM images, revealing the micro-/nano-structural features of the SiO2 nanofibrous membrane, with a mean pore diameter dpore of approximately 5.4 µm (Supplementary Note 236) and fiber diameter between 200–300 nm. The membrane’s parameter is well within the STA’s work range36. Vapor delivery channels (Fig. 2g) are visible due to the substrate-membrane embedding effect. The pillar’s height (h = 650 µm) is greater than Jiang et al.‘s (400 µm), creating wider vapor channels and larger solid-liquid contact areas, further enhancing boiling heat transfer. The designed small aluminum alloy plate is adopted for butane flame experiments.

a Design of the micro-pillared substrate (length: width: thickness = 25 mm: 25 mm: 2 mm). The protruding edge is designed for convenient STA fixture in thermal experiments. b Digital image of the fabricated micro-pillared substrate. c SEM images of the fabricated micro-pillared substrate. The width and spacing of the pillars are a = 300 µm and b = 300 µm. d Digital image of the fabricated STA. e SEM images of the fabricated STA. f SEM images of the SiO2 nanofibrous membrane, presented with multiple magnifications to detail its structural characteristics. g Cross-sectional SEM images of the fabricated STA. The height of the pillar h = 650 µm and the thickness of the membrane α = 100 µm.

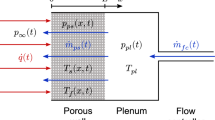

Ground-based thermal protection experiments using butane flame

Adopting the as-fabricated STA (characterized in Fig. 2), ground-based thermal protection experiments were conducted. Figure 3a, b display photographic and schematic views of the utilized experimental platform, respectively. In this experiment, a butane flame gun was utilized to simulate the aerodynamic heating effect, which can creates a temperature of up to 1200 °C42,43. Here, the flame temperatures of both single flame and dual flames modes were measured using thermocouples as demonstrated in Supplementary Movie 1. Results from the movie show that the flame temperature can be above 1400 °C (sufficient to simulate the effects of hypersonic aerodynamic heating), which exceeds the temperature measurement range. From Supplementary Movie 1, we can also observe that the generated heat from dual flames is higher than that of the single flame as temperature rise rate in the dual flames was significantly larger than that of the single flame. A deionized water jet flow was generated through a syringe needle (27 G) and a syringe pump for thermal protection. The fabricated STA was utilized as the front end of a hypersonic vehicle skin. An experimental bracket fixed the STA with its front side facing the butane flame gun (90 ± 1 mm from the front side to the gun nozzle) and its back side aligned to the jet needle for jet cooling, where the STA’s front side acted as a stagnation point. As shown in Fig. 3b, two thermocouples were inserted into the center of the STA to detect the STA’s temperature. One thermocouple (T1) was connected to the data acquisition system for temperature data storage, and another thermocouple (T2) was connected to a temperature meter for real-time temperature display. Considering the high temperature generated during the experiment, mica sheets, shown in Fig. 3a, were adopted to protect the thermocouple wires and the bracket’s clamp. The liquid-solid cooling dynamics were captured by a high-speed camera. During the thermal protection experiment, the jet flow’s volumetric flow rate was set to be 5 mL/min, reaching a steady state in 4 s (Fig. 3c). Please see Supplementary Movie 2 for the dynamics of the jet flow. In order to measure the generated heat flux during the thermal experiment, falling liquid from the target STA was collected by a container which was placed on an electronic balance. Therefore, the utilized water mass for liquid-vapor two-phase cooling can be derived by \({m}_{l-v}^{{\prime} }={\rho }V{-}M/{\tau }\), where ρ is the water density, V is the jet flow’s volumetric flow rate, M is the mass of collected water during the time duration τ.

Thermal protection performance comparisons between the micro-pillared substrate and the STA are displayed in Fig. 4. As shown in Fig. 4a, the micro-pillared substrate rapidly disintegrated when exposed to the butane flame even though jet cooling was initiated. Its temperature quickly increased and remained approximately 600 °C (as the material’s melting range is in that range). Despite the jet cooling, the temperature hardly decreased until it disintegrated, indicating an ineffective cooling mechanism. Figure 4c displays the reason where the liquid impacted the substrate without wetting, broke into droplets, and finally bounced away, indicating the Leidenfrost phenomenon. It experimentally shows the traditional direct liquid cooling hardly functions under the super-overheating state of a hypersonic vehicle. (Please see Supplementary Movie 3 for the Leidenfrost and disintegration processes using the micro-pillared substrate). On the contrary, the utilized STA experienced an instant temperature drop under the identical situation as shown by the blue curve line plots. Figure 4b shows the digital image of the thermal protection processes during the experiments. At 26 seconds, it shows that the mica-sheets were on fire, demonstrating the super-high temperature as the mica’s ignition point is as high as above 800 °C. There was a large, wetted area on the cooling side and the temperature was maintained at approximately 109 °C while being burned in the butane flame. STA’s initial wetting processes were displayed in Fig. 4d using high-speed imaging technology. In the absence of the Leidenfrost effect, the composite membrane-micropillar structure exhibited a rapid wetting phenomenon, which was accompanied by a swift temperature decrease. At the moment of t = 17.740 s, the SiO2 nanofibrous membrane began to break under the continuous impact of the jet flow. However, the cooling efficiency was not impacted by the ruptured membrane, as shown in Supplementary Movie 4, because the temperature at that location was significantly lower than the Leidenfrost point. Consequently, efficient cooling could still be achieved even without the membrane. The heat flux at the thermally stable phase, derived by \(q=\frac{{h}_{{lv}}{m}_{l-v}^{{\prime} }+{{cm}}_{l-v}^{{\prime} }\Delta T}{{A}_{{STA}}}\) (hlv is the latent heat of water, c is the specific heat of water, ΔT is the temperature difference between room temperature and water saturation temperature, and ASTA is the area of the STA), was calculated to be 2.0 ± 0.1 MW/m2, virtually equivalent to Jiang et al.’s work36. The STA after the one-time thermal protection experiment is shown in the inset, marked by the black dotted lines in Fig. 4a. It shows the liquid-solid contact location of the membrane was completely broken. As manifested in Supplementary Movie 4, the thermal protection experiment here is just a short-term one. Please refer to Fig. 5 in the following for long-term cycling thermal protection results.

a Temperature curves for two utilized structures. The red curve represents the temperature trend for the micro-pillared structure. Its temperature breaks because the structure disintegrates as shown in the inset marked by red dotted line. b Digital images of the jet cooling upon the continuously heated STA for various experimental moments. The time here is coherent with that in (a). c Liquid impact dynamics upon micro-pillared substrate at above 600 °C. d Liquid impact dynamics upon the STA at above 600 °C. The moment of t = 0 in (c) and (d) represents the moment the syringe pump began to work. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

a Temperature variation tendencies during nine consecutive thermal protection experiments. Insets show the typical states of the experiments. Starting from the seventh cycling experiment, dual flames instead of one flame was adopted for simulating the aerodynamic heating effect. b Liquid-solid contact dynamics during the second thermal protection experiment. c Liquid-solid contact at the right-hand side of the STA during the third thermal protection experiment. d Liquid-ash contact patterns during the last thermal protection experiment. The moment of t = 0 in (b), (c), and (d) represents the moment the syringe pump began to work in each cycle. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To test the durability and tolerance properties of the STA, cycling tests were conducted, as shown in Fig. 5. Figure 5a plots the thermal protection experimental results from nine cycles using the same STA. As marked by the green lines, the membrane center location ruptured after the first thermal protection experiment. At the beginning of the second experiment, we kept the jet cooling location unchanged, and the liquid-solid contact patterns are displayed in Fig. 5b. Before 14.978 s, there was no wetting phenomenon as the liquid impacted the metal substrate directly due to the damaged area of the membrane. The first three images in Fig. 5b show a droplet bouncing away, indicating a Leidenfrost phenomenon, which is similar as displayed in Fig. 4c. We expected the STA to soon disintegrate. At that moment, we slightly moved the syringe needle to the right, as shown in Supplementary Movie 5 and the image labeled “t = 21.918 s.” The liquid impacted the membrane again, and a large wetting area quickly formed, causing a swift temperature decrease. A sustained cooling was also achieved with a side-wetting phenomenon as displayed in the inset, marked in blue, in Fig. 5a. A stable temperature was also maintained approximately 110 °C. It is interesting that sustained cooling was achieved in the following third (its wetting and liquid-solid contact dynamics are displayed in Fig. 5c), fourth, fifth, and sixth cycles without changing jet flow location, as shown in Supplementary Movie 5. It means that locating the liquid-solid contact point on the membrane’s edge region enhances the membrane’s durability in thermal protection (See Supplementary Note 3 for the reason). Beginning from the seventh cycle, dual flames, as shown in the red-marked inset, was adopted to increase the difficulty of the cooling task using the STA with a broken membrane. A sustained cooling was still acquired, demonstrating a high durability and tolerance properties of the STA.

After completing seventh test, the STA surface adjacent to the clamp became covered with a layer of burning ashes, as shown in the purple-marked inset in Fig. 5a and the first image in Fig. 5d. To test STA’s anti-dust property, the jet flow location was moved to the ash-covered side in the eighth and ninth tests. Figure 5d displays the initial liquid-ash contact patterns in the eighth test. Before 14.340 s, the impact liquid was deflected without wetting. However, when the time reached 15.080 s, the ashes were washed away by the continuous impact of the liquid, resulting in wetting, as displayed in the image labeled “t = 16.936 s.” Consequently, an effective cooling was achieved without STA disintegration in the last two tests. The orange-marked inset in Fig. 5a shows the photographic view of the STA’s complete back side (cooling side) after these nine thermal protection experiments. Please also review Supplementary Note 4 for the front side of the STA after the test. Despite the ruptured membrane, it is expected that the employed STA can still endure additional tests, which is conducive to achieving the reusability of modern aerospace vehicles. Please refer to Supplementary Movie 5 for the entire process of the cycling thermal protection experiments using the butane flame. Table 1 lists the duration of the STA’s exposure to simulated aerodynamic heating and the corresponding heat flux in each test cycle. It can be seen that the heat fluxes from the dual flames were clearly higher than the single flame mode but the STA’s temperature, as plotted in Fig. 5a, did not experience an obvious rise, which indicates that STA’s cooling capability has not yet reached its limiting value.

Experiments show the exclusive function of the SiO2 nanofibrous membrane. However, embedding the membrane into the micro-pillared substrate is relatively complicated (See “Methods”). A potential substitute substrate was designed and fabricated as seen in Fig. 6a, b where a smooth surface instead of a micro-pillared surface was obtained. The surrounding edge was designed to hold the membrane during the experiment. Figure 6b displays the smooth surface with and without the membrane but Fig. 6c shows that both surfaces disintegrate when confronting the butane flame. Figure 6d, e shows the high-speed liquid-solid contact dynamics for both surfaces. Leidenfrost phenomena without wetting were observed for both surfaces, indicating the irreplaceable role of the micro-pillars, functioning as membrane fixer and heat transport bridges. Please refer to Supplementary Movies 6, 7 for thermal protection experiments of the smooth surface and smooth surface with membrane.

a Design of the smooth substrate (length: width: thickness = 25 mm: 25 mm: 2 mm). b Digital image of the fabricated smooth surfaces with and without the membrane. For the surface with the membrane, the membrane is placed upon the smooth surface naturally as shown in the right hand side. c Temperature curves for both surfaces. d Liquid-solid contact dynamics on the smooth surface. e Liquid-solid contact dynamics on the smooth-membrane surface. During the middle of the experiment, a metal tool was used to slightly sweep the membrane to make it tighter with the smooth surface as shown in the image labeled “t = 4.334 s.” Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Materials design and fabrication for acetylene flames

The experiments conducted above highlight the exclusive role of the STA. However, the temperature of the butane flame is relatively low (~1400 °C), and the STA employed, shown in Fig. 2, is not representative of the typical structures found in aerospace vehicles. Acetylene flames can effectively simulate aerodynamic heating conditions at significantly higher temperatures (exceeding 3000 °C),44 and blunt bodies are characteristic structures of hypersonic vehicles45,46. Therefore, in subsequent stages, the blunt body integrated with the STA structure was subjected to acetylene flame exposure. This design approach is to demonstrate the high compatibility of the STA within existing hypersonic aerospace systems.

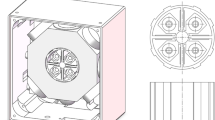

Figure 7a shows the overall diameter of the blunt body is 120 mm with a 14 mm thickness. There are three 1.1 mm holes for inserting thermocouples. As displayed in Fig. 7a, TB1 and TB2 were arranged vertically along the centerline of the blunt body to detect the vertical temperature gradient inside the blunt body, and TB3 was inserted into the same horizontal layer as the TB2. The vertical distance between TB1 and TB2 lB1-B2 is 3 mm and the distance between TB2 and TB3 is 3 mm. The distance between TB1 and the back side of the blunt body is 1.3 mm. In the center of the blunt body’s back side, there is a 20 mm × 20 mm micro-pillar structure for fabricating the STA. The actual fabricated blunt body and the magnified view of the 20 mm × 20 mm STA in the blunt body’s back side are shown in Fig. 7b. The microscopic architecture and dimensions of the STA presented herein are congruent with those depicted in Fig. 2.

Ground-based thermal protection experiments using acetylene flames

For details of the acetylene flame system, please refer to Supplementary Note 5. In this experiment, a neutral acetylene flame, estimated from 3050 °C to 3150 °C, was utilized to simulate the hypersonic aerodynamic heating effect. Given the absence of equipment capable of accurately measuring such extreme temperatures, supporting evidence is provided in Supplementary Note 6 and Supplementary Movie 8, demonstrating the efficacy of the acetylene flame through its capability to rapidly (in seconds) melt and damage materials with high melting points, such as stainless steel (melting point: 1450 °C) and titanium alloy (melting point: 1660 °C). In contrast, a butane flame, which was previously used, failed to significantly damage even stainless steel. For visual documentation of the acetylene flame, please also refer to Supplementary Movie 8.

As depicted in Fig. 8a, the fabricated blunt body was suspended using fixtures attached to two holders. Given that the fixtures are positioned in close proximity to the acetylene flame (4.7 ± 0.1 mm from acetylene flame nozzle to the center of the blunt body outer front side surface) during the thermal protection experiment, aluminosilicate ceramic fibers were employed to insulate the fixtures, ensuring uninterrupted continuation of the acetylene flame-based experiment. Two additional thermocouples (TB4 and TB5) were affixed to the back surface of the blunt body near the STA to monitor cooling-side temperatures during the experiment (refer to Supplementary Note 7 for detailed locations of these thermocouples). Similar to the setup used in butane flame experiments, thermocouple TB3 was connected to a temperature meter for real-time temperature monitoring. Using the same jet flow generation equipment as Fig. 3b, an 8.0 mL/min deionized water jet flow was set to impact the center of the STA with an angle of 30° (refer to Supplementary Note 8 for detailed selection of this impact angle), expected to dissipate the simulated aerodynamic heat. Figure 8b illustrates the front side of the blunt body, which is exposed to the acetylene flame. The image confirms that the aluminosilicate ceramic fibers effectively protect the fixtures from the high-temperature environment. Together with the observations presented in Fig. 8c, it is evident that the structural integrity of the blunt body was maintained throughout the harsh thermal protection experiment (nearly 400 s), showing the high survivability of the STA under extreme thermal environments. Figure 8d presents the temperature profiles recorded throughout the 400-second thermal protection experiment. It shows that all the detected temperatures could be maintained stable under the jet flow cooling. TB2, closest to the acetylene flame, remained below 1200 °C, well beneath the melting point of the material. The temperature difference between TB1 and TB2, as presented in Fig. 8d, was approximately 327 °C, indicating that the heat flux was 2.99 MW/m2 (almost 50% increase compared to Jiang et al.’s work36), derived by \(q={{\lambda }}_{{ss}}\frac{{T}_{B2}- {T}_{B1}}{{l}_{B1- B2}}\) where λss is 27.5 W/(m · K) which is the heat conductivity of the stainless steel. Please refer to Supplementary Note 9 for the determination of this heat conductivity. Overserved from the inset (ii) in Fig. 8d, the membrane maintained its integrity after the experiment, primarily due to the 30° impact angle. Figure 8e illustrates the liquid-solid contact phenomena observed on the STA, demonstrating rapid wetting dynamics and indicating efficient cooling in the absence of the Leidenfrost effect. Please refer to Supplementary Movie 9 for the entire process of the nearly 400-second acetylene flame-based thermal protection experiment.

a Digital images of the experimental platform. The inset magnified view reveals that the acetylene flame gun nozzle is precisely aligned with the center of the blunt body’s frontal surface. b The blunt body is directly exposed to the acetylene flame during the thermal protection experiment. c Digital image of the blunt body after the thermal protection experiment. d Temperature (TB1, TB2, TB4, and TB5) curves during the first-round thermal protection experiment. The jet flow’s volumetric flow rate was set to be 8 mL/min. (i.) Observation from the back cooling side of the blunt body at 262 s of the experiment. (ii.) the STA after the 400-second thermal protection experiment. e Liquid-solid contact dynamics during the thermal protection experiment. The moment t = 0 in (e) represents the moment the high-speed camera began to work. f Temperature (TB1 and TB2) curves during the second-round thermal protection experiment with the jet flow’s volumetric flow rate of 16 mL/min. g SEM images of the micro-pillared substrate following two rounds of thermal protection experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Following the initial acetylene flame-based experiment, the STA membrane was removed using a brush as shown in Supplementary Note 14. Subsequently, a new membrane was inserted with the aid of a mold, depicted in Supplementary Fig. 13, in preparation for the second-round thermal experiment. The successful deployment of this membrane indicates that the micro-pillars experienced no deformation after the first acetylene flame test. For the second thermal experiment, the volumetric flow rate of deionized water jet was set to 16 mL/min. Temperature profiles (TB1 and TB2) are plotted in Fig. 8f, showing that TB2 was maintained just above 1000 °C, while the difference between TB1 and TB2 under stable thermal conditions was approximately 781 °C, as highlighted in the same figure. Therefore, the obtained heat flux was 7.16 MW/m2 (258% increase compared to Jiang et al.’s work36). Figure 8g presents SEM images of the micro-pillars located on the cooling side at the back of the blunt body after the experiment, demonstrating that the dimensions of the micro-pillars remained consistent with their original size after two rounds of thermal experiments. It guarantees a high reusability of this proposed STA-based thermal protection strategy.

Detailed comparisons between the solids (aluminum alloy and stainless steel) before and after the thermal protection experiments are presented in Supplementary Note 10.

Discussion

To examine STA’s exceptional potential in mitigating hypersonic heat barriers, this paper presents small-scale ground-based tests using both butane and acetylene flames to simulate aerodynamic heat effects. The results indicate that the previous Leidenfrost-induced ineffective cooling, which results in final disintegration, can be transformed into sustained cooling, which maintains structural integrity even when exposed to an acetylene flame exceeding 3000 °C. Also, the gained heat flux value here has been comparable with those from traditional ground-based hypersonic aerodynamic heating experiment (7.16 MW/m228), which validates its huge practical value in hypersonic thermal protection. A qualitative conceptual sketch delineating the scalable design of the STA, which can be found in Supplementary Note 11. This sketch advocates for the incorporation of multiple small SiO2 nanofibrous membranes into the internal surface of the forefront of hypersonic vehicles. Given its substantial cooling area, spray cooling technology47,48 is proposed as an effective cooling method for managing the thermal loads encountered by the frontal sections of such vehicles. Future investigations should concentrate on providing more rigorous technical justifications and detailed quantitative analyses regarding the scalability and efficiency of this cooling approach in hypersonic vehicle design.

Considering the economy of the experiment, the blunt body, exposed to the acetylene flame, was made by the 430 stainless steel. From the experimental results and properties of common aerospace materials, the stainless steel can be safely replaced by the more popular aircraft skin material titanium alloy as the titanium alloy has a higher melting point compared with the stainless steel.

While the current study provides valuable insights into the heat transfer characteristics and potential materials for use in hypersonic flight applications, it is important to acknowledge several limitations that may impact the applicability and scalability of the findings. Firstly, the experiments were conducted at atmospheric pressure, whereas hypersonic flight typically occurs at much lower pressures. This discrepancy could influence the behavior of phase change phenomena and the structural integrity of the materials being tested, potentially leading to different results under actual flight conditions. Secondly, although the current experimental setup can produce certain concentrations of dissociated oxygen, it falls short of replicating the high levels observed during atmospheric re-entry or hypersonic flight. Dissociated oxygen plays a critical role in the chemical and thermal responses of materials, influencing phenomena such as surface oxidation and heat transfer. The lack of dissociated oxygen in the experimental conditions may limit the direct correlation between laboratory results and real-world performance, potentially affecting the accuracy of material response predictions under extreme environments. Thirdly, the heat fluxes observed in this study, while representative of certain flight conditions, do not encompass the full range of conditions encountered during a hypersonic flight. Variations in heat flux can occur due to changes in flight altitude, velocity, and angle of attack, as well as the specific geometry. These factors can significantly alter the thermal environment and, consequently, the material’s response. Fifth, Despite the preservation of geometry and mass after exposure to butane and acetylene flames, the mechanical properties of the STA undergo significant alterations. These changes exhibit a complex dependency on both the material composition, the operating temperature and duration. While some materials demonstrate improved mechanical properties post-exposure, others experience degradation. This variability underscores the importance of material selection and optimization for specific operational conditions. Furthermore, this paper only demonstrates the effectiveness of the STA in blunt geometries, such as flat plates and blunt bodies. The performance of the STA when integrated into hypersonic sharp leading edges49 remains unaddressed.

Future investigations should focus on the aforementioned six aspects to ensure practical STA application in real-world hypersonic flight scenarios. To overcome these above limitations, more ground-based vacuum experiments and real high-altitude tests are urgently required for its actual application.

In summary, this paper proposes a direct cooling approach to mitigating the hypersonic heat barrier using the developed blunt-shaped nano-/micro- STA, thereby revolutionizing the current state-of-the-art hypersonic thermal protection technology. Our approach demonstrates improved liquid cooling efficiency against high solid temperatures (created by both butane and acetylene flames) with a heat flux as high as 7.16 MW/m2, protecting the solid from disintegration. Cycling tests show the excellent durability and tolerance properties of the proposed STA, which meets the reusability demand of current aerospace vehicles. Derived from our experimental results, aluminum alloy materials can be utilized for the fuselage of supersonic aircraft with leading edge temperatures not exceeding 1400 °C. For hypersonic aircraft where leading edge temperatures do not surpass 3150 °C, titanium alloys are suitable for the airframe construction. However, despite the preservation of geometry and mass, the mechanical properties of the adopted STA exhibit significant alterations. These changes depend on the material, temperature, and exposure duration, highlighting that substantial efforts are still required to achieve a more reliable STA-based thermal protection solution.

Combined with the STA and easy liquid cooling method, this strategy marks a substantial evolution in contemporary aerospace design and engineering. Our proposal challenges the current aerospace TPSs with a lighter material and easier cooling strategy, enhancing modern hypersonic vehicles’ reusability, maneuverability, and cost-effectiveness. Besides hypersonic thermal protection, this nano-micro approach has wide applications for TPSs in other applications, such as solar probes50, international thermonuclear experimental reactors (ITER) / experimental advanced superconducting tokamak (EAST)51, and volcano detectors52.

Methods

Materials and surface fabrication. In the butane flame-based thermal experiment, the micro-pillared substrate, as displayed in Fig. 2b, was made from 6000 series aluminum alloy, which is a common aircraft skin material (melting point: ~600 °C). The periodic micro-pillar pattern was fabricated by the wire cutting as demonstrated in Supplementary Note 12. The high temperature during the wire cutting generated local melting of the aluminum alloy, which led to the rough surface of the micro-pillared substrate.

The blunt body in the acetylene flame-based experiment was made from 420 stainless steel. The micro-pillar pattern on the back side of the blunt body was also fabricated by the wire cutting.

The SiO2 nanofibrous membrane with an average pore size of approximately 5.4 μm was fabricated using the electrospinning method53. The PVA precursor solution (12 wt%) was prepared by dissolving PVA (Mw = 88,000 g mol–1) in deionized water at 80 °C and stirring continuously for 24 h. The silane sol was obtained by stirring the tetraethoxysilane aqueous solution with H3PO4 as the hydrolysis catalyst at room temperature for 10 h. The molar ratio of tetraethoxysilane:H3PO4:H2O was 1:0.01:10. Then, 12 g of the silane sol was added to an equal weight of PVA precursor solution and stirred for an additional 4 h until a homogenous solution was obtained. The precursor solution was loaded into a syringe equipped with a 18 G needle and injected at a flow rate of 1 ml/h using a syringe pump. Electrospinning was carried out under a voltage of 18 kV, with an aluminum foil-covered grounded metallic rotating roller serving as the collector. The as-spun composite fibers were dried for 2 h at 80 °C and then calcined for 2 h at 600 °C in air. Please refer to Supplementary Movie 10 for the fabrication process of the SiO2 nanofibrous membrane.

The utilized STA was obtained by embedding the SiO2 nano-fibrous membrane into the micro-pillared surface. First, the membrane was carefully placed onto the micro-pillared substrate. Then, a specially designed mold with square hole to embed each STA substrate’s pillar was fabricated, and last, the mold was pressed (Supplementary Note 13) to obtain the as-fabricated STA, as shown in Fig. 2d.

In order to reuse the STA micro-pillared substrate when the membrane was broken, a brush, as shown in Supplementary Note 14, was used to remove the broken membrane.

For detailed model type of utilized experimental and characterization instruments, please refer to Supplementary Note 15.

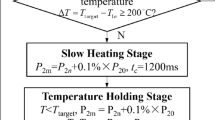

Experimental methods. Prior to the butane flame-based thermal protection experiment, several experimental procedures should be followed: (1). Install experimental equipment as shown in Fig. 3a; (2). Ensure the jet flow needle and the ejected flame align to the center region of the STA; (3). Power on the data acquisition system, real-time temperature meter, syringe pump, and high-speed camera (set the frame rate to be 500 fps); (4). Adjust the syringe pump to a desired volumetric flow rate, initiate the data acquisition system and real-time temperature meter, ignite the butane gun, and wait until the STA’s temperature reaches 500 °C; (5). Initiate the syringe pump and high-speed imaging system at the same time and wait until the experiment in this cycle is finished; (6). Extinguish the butane flame and almost simultaneously, power off the syringe pump; (7). Wait until the system returns to room temperature and prepare for the next cycle of the experiment. For both the single flame and dual flames, the oxygen-butane mass ratio remained to be 1: 24. In the single flame mode, the fuel mass flow rate was 1.76 g/min and that doubled in the dual flames mode.

In the acetylene flame-based experiment, detailed experimental procedures before the thermal protection test are as follows: (1). Install experimental equipment as shown in Fig. 8a; (2). Adjust the jet flow needle and ensure a 30° impact angle; (3). Power on the data acquisition system, real-time temperature meter, syringe pump, and high-speed camera (set the frame rate to be 250 fps); (4). Adjust the syringe pump to a desired volumetric flow rate and open the pressure-regulating valves on the oxygen and acetylene cylinders to initiate gas flow; (5). Adjust the working pressures of the oxygen and acetylene to 0.5 MPa and 0.05 MPa, respectively; (6). Initiate the data acquisition system and real-time temperature meter; (7). Initiate the syringe pump and Ignite the acetylene flame gun simultaneously, and wait until the STA’s temperature reaches stable; (8). Initiate the high-speed imaging system, and wait until the high-speed camera finishes recording; (9). Close the valves on the oxygen and acetylene cylinders to extinguish the acetylene flame when the thermal protection experiment lasts for nearly 400 s; (10). Power off the syringe pump until the temperature of the blunt body returns to room temperature. For the acetylene flame experiment, the oxygen-acetylene volume ratio was 1:1. The acetylene volumetric flow rate was controlled to be 10 L/min.

Please refer to Supplementary Note 16 for detailed flame angles in the butane flame-based and acetylene flame-based thermal protection experiments.

Data availability

The data are provided in this article and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code and mathematical algorithm is not deemed central to the conclusions. Calculation methods in this study are available within the paper and its supplementary files.

References

Curran, E. Scramjet engines: the first forty years. J. Propul. Power 17, 1138–1146 (2001).

Zhang, S. et al. Research progress on active thermal protection for hypersonic vehicles. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 119, 100646 (2020).

Petley, D. H. & Jones, S. C. Thermal management for a Mach 5 cruise aircraft using endothermic fuel. J. Aircr. 29, 384–389 (1992).

Nakaya, S., Tsue, M., Kono, M., Imamura, O. & Tomioka, S. Effects of thermally cracked component of n-dodecane on supersonic combustion behaviors in a scramjet model combustor. Combust. Flame 162, 3847–3853 (2015).

Wang, D., Pan, K., Liu, Y., Wang, L. & Liu, Z. Research on the cooling performance of the discontinuous transpiration surface structure for the leading edge of a hypersonic vehicle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 241, 122324 (2024).

Voland, R. T., Huebner, L. D. & McClinton, C. R. X-43A hypersonic vehicle technology development. Acta Astronaut 59, 181–191 (2006).

Tadjdeh, Y. & Harper, J. Hypersonic missiles. Natl Def. 104, 28–31 (2019).

De Weck, O. L. & Cummings, R. Editorial: sixty years of the journal of spacecraft and rockets. J. Spacecr. Rockets 60, 1–2 (2023).

Lv, C., Lan, Z., Ma, T., Chang, J. & Yu, D. Hypersonic vehicle terminal velocity improvement considering ramjet safety boundary constraint. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 144, 108804 (2024).

Mansour, N. N., Panerai, F., Lachaud, J. & Magin, T. Flow mechanics in ablative thermal protection systems. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 56, 549–575 (2024).

Filatyev, A. S. et al. Research and development of aerospace vehicles with air breathing electric propulsion: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 136, 100877 (2023).

Guo, J. et al. Hypocrystalline ceramic aerogels for thermal insulation at extreme conditions. Nature 606, 909–916 (2022).

Chang, X. et al. Multiscale interpenetrated/interconnected network design confers all-carbon aerogels with unprecedented thermomechanical properties for thermal insulation under extreme environments. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308519 (2024).

Su, L. et al. Strong yet flexible ceramic aerogel. Nat. Commun. 14, 7057 (2023).

Zeng, Y. et al. Ablation-resistant carbide Zr0.8Ti0.2C0.74B0.26 for oxidizing environments up to 3000 °C. Nat. Commun. 8, 15836 (2017).

Gu, D. et al. Material-structure-performance integrated laser-metal additive manufacturing. Science 372, eabg1487 (2021).

Su, L. et al. Anisotropic and hierarchical SiC@ SiO2 nanowire aerogel with exceptional stiffness and stability for thermal superinsulation. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay6689 (2020).

Fu, X. et al. Gradient all-nanostructured aerogel fibers for enhanced thermal insulation and mechanical properties. Nat. Commun. 16, 2357 (2025).

Urzay, J. Supersonic combustion in air-breathing propulsion systems for hypersonic flight. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 50, 593–627 (2018).

Li, Z., Zhang, K., Li, K. & Li, J. Effects of mid-passage gap with a variable surface angle on a turbine vane endwall’s aerothermal and film cooling performances. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 37, 20–37 (2024).

Chen, B., Tian, X. & Yi, S. Numerical study of a composite cooling method for hypersonic aircraft. Phys. Fluids 36, 016125 (2024).

Hermann, T. & McGilvray, M. Analytical solution of flows in porous media for transpiration cooling applications. J. Fluid Mech. 915, A38 (2021).

Wang, J.-X., Mao, Y. & Miljkovic, N. Nano-enhanced graphite/phase change material/graphene composite for sustainable and efficient passive thermal management. Adv. Sci. 11, 2402190 (2024).

Wang, J.-X. et al. A nano-sheet graphene-based enhanced thermal radiation composite for passive heat dissipation from vehicle batteries. Nano Mater. Sci. 6, 443–455 (2024).

Hao, G. et al. Microfluidic-encapsulated phase change fibers with graphene coating for passive thermal management. Small 21, e2500839 (2025).

Zhang, S. et al. Nonflammable electrolyte with low exothermic design for safer lithium-based batteries. Nano Energy 114, 108639 (2023).

Song, I. T. et al. Thermal runaway prevention through scalable fabrication of safety reinforced layer in practical Li-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 8294 (2024).

Zhu, Y., Peng, W., Xu, R. & Jiang, P. Review on active thermal protection and its heat transfer for airbreathing hypersonic vehicles. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 31, 1929–1953 (2018).

Benrabah, R. et al. Experimental study of the impact of alcohols on the oxidation stability of a surrogate jet-fuel. Fuel 361, 130750 (2024).

Wang, J.-X. et al. Enhanced interfacial boiling of impacting droplets upon vibratory surfaces. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 658, 748–757 (2024).

Wang, J.-X., Guo, W., Xiong, K. & Wang, S. N. Review of aerospace-oriented spray cooling technology. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 116, 100635 (2020).

Van Erp, R., Soleimanzadeh, R., Nela, L., Kampitsis, G. & Matioli, E. Co-designing electronics with microfluidics for more sustainable cooling. Nature 585, 211–216 (2020).

Xu, Z. et al. Liquid-superspreading-boosted high-performance jet-flow boiling for enhancement of phase-change cooling. Adv. Mater. 35, 2210557 (2023).

Leidenfrost, J. G. De aquae communis nonnullis qualitatibus tractatus. (Ovenius, 1756).

Edalatpour, M., Colón, C. L. & Boreyko, J. B. Ice quenching for sustained nucleate boiling at large superheats. Chem 9, 1910–1928 (2023).

Jiang, M. et al. Inhibiting the Leidenfrost effect above 1000 °C for sustained thermal cooling. Nature 601, 568–572 (2022).

Wang, J.-X. et al. Machine-assisted quantification of droplet boiling upon multiple solid materials. Nano Energy 125, 109560 (2024).

Zhou, Y. & Zhu, P. A paradigm shift in liquid cooling by multitextured surface design. Innovation 3, 100222 (2022).

Puckett, S. D., Taylor, E., Raimondo, T. & Webster, T. J. The relationship between the nanostructure of titanium surfaces and bacterial attachment. Biomaterials 31, 706–713 (2010).

Wang, J.-X. et al. Investigation on a gas-atomized spray cooling upon flat and micro-structured surfaces. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 161, 106751 (2021).

Cho, H. J., Preston, D. J., Zhu, Y. & Wang, E. N. Nanoengineered materials for liquid–vapour phase-change heat transfer. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 1–17 (2016).

Yang, J., Wang, D., Li, M., Ji, C. & Wang, B. Thermal response and pyrolysis behavior of carbon fiber/phthalonitrile composites under one-sided butane flame heating: Experimental and numerical analysis. Compos. Part A – Appl. Sci. Manuf. 175, 107788 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Hollow-grained “Voronoi foam” ceramics with high strength and thermal superinsulation up to 1400 °C. Mater. Today 46, 35–43 (2021).

Alekseev, V. A. et al. High-temperature oxidation of acetylene by N2O at high Ar dilution conditions and in laminar premixed C2H2 + O2 + N2 flames. Combust. Flame 238, 111924 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Mach reflection and pressure/heating loads on V-shaped blunt leading edges with variable cross-sections and crotches. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 38, 103163 (2025).

Luckring, J. M. & Rizzi, A. Prediction of concentrated vortex aerodynamics: Current CFD capability survey. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 147, 100998 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Recent active thermal management technologies for the development of energy-optimized aerospace vehicles in China. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 34, 1–27 (2021).

Wang, J.-X., Li, Y. Z., Li, G. C., Xiong, K. & Ning, X. Investigation of a gravity-immune chip-level spray cooling for thermal protection of laser-based wireless power transmission system. Int. J. Heat. Mass Trans. 114, 715–726 (2017).

Peters, A. B. et al. Materials design for hypersonics. Nat. Commun. 15, 3328 (2024).

Uyanna, O. & Naiafi, H. Thermal protection systems for space vehicles: a review on technology development, current challenges and future prospects. Acta Astronaut 176, 341–356 (2020).

Juarez, R. et al. ITER full model in MCNP for radiation safety demonstration. Nat. Commun. 15, 8563 (2024).

Di Genova, D. et al. In situ observation of nanolite growth in volcanic melt: A driving force for explosive eruptions. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb0413 (2020).

Mao, X. et al. Silica nanofibrous membranes with robust flexibility and thermal stability for high-efficiency fine particulate filtration. RSC Adv. 2, 12216–12223 (2012).

Acknowledgments

This work is co-sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under the grant 12404500 to Dr. Yufeng Mao, Sichuan Natural Science Foundation under the grant 24NSFSC5165 to Dr. Ji-Xiang Wang, Shanghai Pujiang Program under the grant 24PJD104 to Dr. Ji-Xiang Wang, Shanghai Leading Talent Program (Overseas) to Dr. Ji-Xiang Wang, Young Talent Support Program of Jiangsu, China under the grant JSTJ-2024-619 to Dr. Ji-Xiang Wang, and Taizhou Talent Nurturing Initiative to Dr. Ji-Xiang Wang. The authors would like to extend their appreciation to Professor Yongping Chen from Southeast University and Mr. Jian Qian from Yangzhou University for their helps in conducting the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-X.W. and H.W. conceived the research. J.-X.W., M.Z., and H.W. designed the research. J.-X.W., M.Z., J.-X.L., and H.W. carried out the experiments. J.-X.W., S.W. and J.B. characterize the materials. J.-X.W. and Y.M. collected data and conducted image analysis. J.-X.W., M.Z., J.-X.L., Y.M., and H.W. contributed to data analysis. All the authors wrote the manuscript and agreed on its final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Stefano Mungiguerra, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, JX., Zhong, M., Li, JX. et al. Mitigating hypersonic heat barrier via direct cooling enhanced by leidenfrost inhibition. Nat Commun 16, 6931 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62120-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62120-2

This article is cited by

-

Temperature-Dependent Infrared Engineering for Extreme Environments: All-Dielectric Thermal Photonic Metamaterials Stable at 1873 K in Air

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)

-

Research progress of the application of microchannels, bionic structures and nanofluids in the thermal management of electronic components

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (2026)