Abstract

Childhood brain development involves dynamic remodeling shaped by genetic influences contributing to long-term neurodevelopmental variation. Here we report integrative analyses of over 8600 children, using 7 brain imaging-derived phenotype (IDP) modalities, polygenic scores (PGS) of 33 complex traits, and 266 cognitive and psychological phenotypes. Most brain IDPs show low-to-moderate SNP-based heritability, lower than typically observed in adults. Sparse generalized canonical correlation analysis reveals positive associations between cognitive-related PGS and structural MRI features (e.g., total grey matter and ventral diencephalon volumes) and N-back task-related activation, while PGS for ADHD, depression, and neuroticism showed negative associations. Cognitive PGS also correlates positively with diffusion MRI metrics (streamline counts, fractional anisotropy in subcortical-frontal tracts and inferior parietal–subcortical tracts), whereas health-risk PGS (e.g., BMI, ADHD) correlates negatively. This study delineates key gene–brain–behavior associations in preadolescence, providing a multivariate dissection of the polygenic architecture underlying neurodevelopment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preadolescent childhood is a critical developmental period characterized by substantial neurobiological changes. During this period, white matter volume increases substantially, and grey matter undergoes region-specific growth, peaking in the frontal and parietal lobes1,2. This dynamic interplay between genetics and environment not only shapes the maturing brain but also influences the course of cognitive abilities and mental wellness in later life. Studies show that genetic factors play a pivotal role in these developmental processes, with neural and genetic markers of psychiatric vulnerability potentially present at this early stage, prior to the onset of behavioral symptoms3,4,5.

Cognitive functions and psychiatric disorders share common genetic and neurological roots6. The heritability of cognitive and psychological traits generally increases with age. For instance, genetics accounts for less than 25% of the variability in cognition in infancy, but up to 70% in adolescence7. Similarly, the heritability of various psychopathologies, including externalizing behaviors, depression, and anxiety, also appears to rise with age8. This evolving genetic influence may be attributed to developmental changes in gene expression or neuroanatomical alterations that render the brain more susceptible or resistant to genetic and environmental inputs at different life stages9. Given these substantial genetic influences, elucidating the genetic basis of neural and cognitive development is imperative to advance our understanding of the neurobiological foundations of cognition and psychopathology.

The joint analysis of multimodal genetic and brain imaging data could offer valuable insights into the relationships between genetic variation and brain imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs), and their relationship to cognitive and behavioral processes. Advances in high-throughput data generation have made computational approaches linking genetics and neuroimaging central to biological systems research. Identifying brain structures or functions associated with polygenic signals may improve our understanding of their biological relevance to cognitive and psychological development. However, existing studies have often overlooked the developmental stage of preadolescence10. While prior works have demonstrated significant connections between the brain and genomic components11,12, no studies have yet examined the polygenic influences on specific brain IDPs and behavioral outcomes during preadolescence.

We depart from traditional analyses to employ sparse generalized canonical correlation analysis (SGCCA)13,14, an advanced multivariate technique optimized for high-dimensional data characteristic of neuroimaging and genetic datasets. SGCCA achieves this by enforcing sparsity through penalization, effectively reducing the feature space by assigning zero weights to less relevant variables while retaining the most informative ones. This ensures that key genetic variants or brain imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs) are prioritized, thereby enhancing interpretability. Moreover, SGCCA introduces regional specificity by focusing on distinct brain regions or networks of interest, addressing a critical limitation of earlier canonical correlation analysis methods, which often lacked the capacity to capture localized patterns in IDPs10,11,12,15.

In this work, we utilize a comprehensive suite of polygenic scores (PGS) across a diverse range of 33 behavioral, cognitive, and psychological traits to test the functional genetic associations with brain IDPs and behavioral phenotypes, which could provide interpretable and informative insights into trait variability. Also, this methodology contrasts with prior studies that relied on a narrow spectrum of PGS and could not capture the full genetic architecture influencing trait development11. With the novel application of this multivariate method to the genetic and brain imaging data, we aimed to reveal the interconnected variations of genetic signals, the brain, and cognitive and psychological outcomes in the preadolescent brain. Our estimates of genetic heritability for multimodal brain features set the stage for SGCCA, enabling us to explore the covariation between IDPs and polygenic scores across traits, potentially transforming our comprehension of the genetic orchestration of brain, cognitive, and behavioral development.

Results

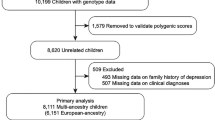

Participants

From the initial cohort of 11,875 participants in the ABCD study, 6555 European-ancestry participants passed quality control (QC) for brain imaging and genetic data and were included in the analysis (8620 multi-ancestry participants for exploratory analysis) (Table 1). We compared the estimated Ps between European-ancestry and non-European-ancestry individuals, and PGS showed no significant differences across ancestries except for the educational attainment (P = 0.006) and IQ PGS (P = 0.0018) (Supplementary Data 4).

SNP-Based heritability

We quantified the heritability of brain imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs) and psychological measures using imputed autosomal SNPs. Out of 7963 IDPs tested in 6555 children of European ancestry, 1237 showed significant heritability, ranging from 19% to 27% (Fig. 1A and Table 2). The average heritability for brain IDPs (23%) was higher than for non-brain measures (19%) (Fig. 1C). Structural MRI IDPs accounted for the largest proportion of heritable traits (63.2%), followed by diffusion MRI measures such as fractional anisotropy (33.9%), diffusion count (14.1%), and task-based fMRI measures (2.7%–4.1%). Resting-state fMRI (3.4%) and SST fMRI (0.8%) showed the lowest proportions of heritable IDPs.

A Estimated SNP heritability of brain imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs) (Vg/Vp), where O denotes significant estimates and X denotes non-significant estimates. B Estimated SNP heritability of behavioral phenotypes, with colored bars representing significant heritability estimates and unfilled bars representing non-significant estimates. C Bars show mean ± SE SNP heritability for all significant brain imaging (n = 1237 IDPs) and behavioural phenotypes (n = 34 traits; FDR < 0.05). Dots mark the individual point estimates for each phenotype. SNP-based heritability reflects the proportion of variance in a trait explained by genetic variations, specifically single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). In the ABCD youth sample, heritability was estimated using a linear mixed model framework, fitting all common SNPs as random effects to quantify their contribution to trait variance. IDP imaging-derived phenotype, SE standard error, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, FDR false-discovery rate.

Within structural MRI, cortical volume exhibited the highest heritability (27%), while curvature showed the lowest (22%). Structural MRI IDPs also displayed higher heritability than diffusion MRI IDPs (19%–22%), suggesting greater genetic influence on grey matter compared to white matter in this age group. This pattern contrasts with findings from adult datasets, such as the UK Biobank8, where white matter heritability typically exceeds that of grey matter. Task-based fMRI traits showed moderate heritability, with estimates of 25% for SST, 24% for N-back, and 22% for MID.

Neurocognition related phenotypes exhibited the highest heritability among psychological measures, averaging 29% (Fig. 1B). Key traits with heritability exceeding 30% included the Flanker Inhibitory Control Test, Oral Reading Recognition, and Total Intelligence Composite Score. Behavioral measures, including externalizing problems and anxious or depressed behaviors, showed significant heritability, averaging 16–18%. Specific traits such as Anxious/Depressed Syndrome Scale, rule-breaking behavior and externalizing problems exceeded 20%. Mental health conditions, including generalized anxiety disorder, eating disorders, and suicidal behaviors, also displayed significant heritability.

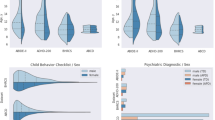

Bivariate association of PGS with cognitive, behavioral, and psychological outcomes

Bivariate correlation of PGS with Cognitive, Behavioral, and Psychological Outcomes were tested. Cognitive-related PGS (e.g., cognitive performance, IQ) showed strong effects, explaining up to 18% of variance in crystalized intelligence scores (β = 0.286, P < 0.0001). BMI PGS accounted for 13% of BMI variance (β = 0.299, P < 0.0001), while PGS for ADHD, depression, and PTSD explained up to 3% of their respective traits. Notably, PGS for brain volume exhibited weaker associations (e.g., Total Brain Volume PGS R² = 2.8%). Detailed results, including findings for multi-ancestry samples, are available in Supplementary Data 5 and Supplementary Information.

Bivariate correlation between PGS and brain IDPs

Significant associations between 33 PGS and brain IDPs were mainly found in structural metrics, such as morphometric measures and dMRI (streamline count, FA) (P < 0.049; FDR correction) (Supplementary Data 6). Total brain volume, PGS and cognitive-related PGS (e.g., cognitive performance, IQ) were linked to widespread brain regions. Except for N-back fMRI, functional metrics (e.g., resting-state fMRI) showed no significant associations, highlighting the stability of structural measures in detecting genetic influences. Advanced multivariate methods like CCA are recommended to capture complex genetic-brain relationships and provide deeper insights into cognition and behavior.

Multivariate associations among PGS, Phenotypes, and Brain IDPs

Multivariate associations among PGS, brain IDPs, and behavioral phenotypes were analyzed using SGCCA. Significant covariation patterns were observed between PGS and brain phenotypes, particularly structural MRI (component (comp) 1, 2, 4 and 5), diffusion MRI (streamline count, comp 1, 2, 3 and 5; FA, comp 1), and N-back task-based fMRI (comp 1). Resting-state and other task-based fMRI modalities showed fewer significant components. Triadic relationships explored through 3-block SGCCA revealed consistent positive loadings for cognitive-related PGS (e.g., educational attainment, IQ) and negative loadings for PGS linked to behavioral and mental health risks (e.g., depression, ADHD). These findings highlight the genetic underpinnings linking cognitive and psychopathological traits with neural phenotypes. Full results are provided in Supplementary Data 10 and 11 and Supplementary Information.

Brain morphometry (sMRI)

We explored the covariation patterns between PGS, brain morphometric data (sMRI), and behavioral phenotypes using 2-block and 3-block CCA analyses (Fig. 2). In the 2-block CCA, four significant components were identified, with Component 1 showing the strongest association between cognitive-related PGS (e.g., IQ, educational attainment) and increased brain volumes and surface areas. Other components highlighted tissue-specific genetic influences, including a white-grey matter dichotomy and distinct associations between risk-related PGS and brain shape metrics (e.g., curvature, thickness). In the 3-block CCA, cognitive-related PGS were linked to positive cognitive outcomes and brain morphometry, while risk-related PGS were negatively associated with behavioral and health variables. Full details, including component loadings and detailed metrics, are provided in Supplementary Data 12, Supplementary Data 13, and Supplementary Information.

Heat-maps show significant loadings of cortical and subcortical morphometric measures and PGS across canonical components from the two-block CCA of PGS versus structural MRI (sMRI). A Surface area, (B) volume, (C) thickness, (D) mean curvature, (E) subcortical volumes, (F) white-matter measures, (G) PGS. Colour scale (right) ranges from – 1 (blue) to + 1 (orange-red). Regions significant in both two-block and three-block analyses are outlined and marked with an asterisk (*). Significance was set at FDR-corrected P < 0.05. sMRI structural magnetic-resonance imaging, PGS polygenic score.

Diffusion MRI (dMRI)

Streamline count

We investigated the covariation patterns between PGS, streamline count, and behavioral phenotypes using 2-block and 30-block CCA analyses. In the 2-block CCA, we identified four significant components. Component 1 linked cognitive-related PGS (e.g., IQ, educational attainment) to streamline counts in subcortical and frontal regions. Component 2 revealed opposing genetic influences, with white matter volume positively associated with motor-sensory connectivity, while mental health risk PGS were inversely associated with frontal-temporal connectivity (Fig. 3). Components 3 and 5 highlighted associations with physical health and well-being, emphasizing distinct connectivity patterns in subcortical and temporal regions. The 3-block CCA analysis extended these findings, linking cognitive-related PGS to posterior cingulate cortex pathways and crystallized intelligence scores. Full results are provided in Supplementary Data 14, 15, and Supplementary Information.

A Significant components (1, 2, 3, 5) from CCA of streamline count (top) and PGS (bottom). B Significant component 1 from CCA of fractional anisotropy (FA; left) and PGS (right). Colour scale ranges from – 1 (blue) to + 1 (red). Connections significant in both two-block and three-block analyses are outlined and marked with an asterisk (*). FDR-corrected P < 0.05. dMRI diffusion MRI, FA fractional anisotropy, PGS polygenic score.

Fractional anisotropy (FA)

In the 2-block PGS-dMRI fractional anisotropy (FA), CCA identified only one significant component of covariation. In particular, cognitive-related PGS (e.g., educational attainment, IQ) were positively associated with FA connectivity patterns involving the inferior parietal gyrus (IPG) and subcortical regions, while health-related PGS (e.g., BMI, ADHD) exhibited negative loadings. In the 3-block CCA, IPG-centered FA pathways were strongly linked to cognitive-related PGS and performance measures, such as crystallized intelligence, while health and behavioral traits showed inverse associations. Full results, including loadings and detailed connectivity patterns, are available in Supplementary Data 16, 17, and Supplementary Information.

Resting-state fMRI

Two significant components of covariation between PGS and rsfMRI data were identified in the 2-block CCA. Component 1 linked cognitive-related PGS (e.g., IQ, educational attainment) to connectivity patterns in retrosplenial-temporal, auditory, and cingulo-opercular networks, while mental health-related PGS (e.g., depression, neuroticism) showed negative associations. Component 2 revealed modest associations with eating disorder PGS and negative correlations with subjective well-being traits. The 3-block CCA extended these findings, linking cognitive-related PGS and rsfMRI connectivity to cognitive performance and favorable environmental factors, while mental health and behavioral risks negatively influenced these associations. Full results, including connectivity patterns, are provided in Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 18, 19, and Supplementary Information.

A Significant resting-state functional connection. B Significant PGS identified from the PGS–rsfMRI CCA. Colour scale as in Fig. 3. Connections significant in both two-block and three-block analyses are outlined and marked with an asterisk (*). FDR-corrected P < 0.05. rsfMRI resting-state functional MRI, PGS polygenic score.

Task-based fMRI

In the 2-block CCA analysis, only the N-back task-based fMRI yielded a significant component, while the 3-block CCA revealed significant associations across all task-based modalities (N-back, MID, SST). These significant associations linked cognitive-related PGS (e.g., IQ, cognitive performance) to activation patterns in key brain regions and behavioral phenotypes. N-back fMRI highlighted cognitive performance and emotional stability, while MID and SST tasks revealed associations with reward processing and inhibitory control, respectively. Behavioral challenges and adverse environmental factors were inversely linked to task-based activation patterns. Full results, including brain-behavior relationships, are detailed in Fig. 5, Supplementary Data 20–22, and Supplementary Information.

This figure illustrates significant task reactivity identified in the first component of the PGS-N -Back fMRI CCA. Heat-map of genome-wide PGS (rows) showing significant loadings across canonical components for five brain-imaging modalities (columns): structural MRI (sMRI), diffusion MRI streamline count (dMRI-Count), diffusion MRI fractional anisotropy (dMRI-FA), resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI), and task-based N-Back fMRI. Colour scale – 1 (blue) to + 1 (red). Only components with significant correlations are displayed. PGS polygenic score, IDP imaging-derived phenotype.

Phenotypes

The 2-block CCA identified four significant components linking PGS to behavioral phenotypes. Component 1 associated cognitive-related PGS (e.g., IQ, cognitive performance) with neurocognitive strengths and socioeconomic advantages but inversely with behavioral challenges. Component 2 linked risk-related PGS to elevated behavioral symptoms, while Component 4 focused on physical traits (e.g., height) and emotional traits. Component 5 reflected cognitive and physical PGS alongside socioeconomic and behavioral risks. These results emphasize the intricate interplay between genetic predispositions, behavioral phenotypes, and environmental influences. Full results are provided in Fig 6, Supplementary Data 23 and Supplementary Information.

Heat-map shows the significant loadings of genome-wide PGS (rows) on the four significant CCA components (columns 1, 2, 4, 5) linking PGS and behavioural phenotypes. Component significance was established by 2000 permutations (FDR-corrected P < 0.05). Loading significance was assessed by 2000 bootstraps; loadings whose 95% confidence interval excluded zero were retained and FDR-corrected. Colour scale – 1 (blue) to + 1 (red). Corresponding behavioural-phenotype loadings are in Supplementary Fig. 2. PGS polygenic score, CI confidence interval, FDR false-discovery rate.

Predictive performance of the PGS-based models

We evaluated machine learning models incorporating genomic polygenic scores (PGS) to predict mental health outcomes. PGS-based models demonstrated statistically significant improvements in predictive performance for several outcomes when compared to covariate-only models (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Information).

White bars indicate the covariate-only baseline, and blue bars indicate the PGS + covariate model. Bars show mean ± SD across 30 independent repetitions using the same test subjects; dots plot the performance from each run. A Classification task (n = 9 outcomes); metric = accuracy. B Regression tasks (n = 10 outcomes); metric = explained variance (R²). PGS polygenic score, SD standard deviation.

Discussion

In this study, we leveraged genetics, multimodal brain imaging, and detailed environmental and behavioral data from a large cohort of preadolescent children to investigate the multivariate relationships underlying neurodevelopment. Using genome-wide polygenic scores (PGS) and canonical correlation analyses (CCA), we identified three key findings. First, SNP-based heritability analyses revealed significant genetic contributions to both brain and behavioral phenotypes, with brain phenotypes exhibiting higher heritability than behavioral traits, underscoring the genetic basis of neurodevelopmental trajectories. Second, integrative analyses with SGCCA linked PGS for educational attainment and IQ to robust positive associations across multiple brain imaging modalities, including structural MRI (sMRI), diffusion MRI (dMRI), and task-based fMRI, while PGS for depression, neuroticism, and BMI showed consistent negative associations (Fig. 8). These patterns highlight the interconnected genetic influences shaping cognitive abilities and mental health during development. Third, machine learning models trained on the 33 PGS demonstrated moderate to robust prediction of cognitive outcomes but showed lower performance for psychopathologies.

Heat-map of genome-wide PGS (rows) showing significant loadings across canonical components for five brain-imaging modalities (columns): structural MRI (sMRI), diffusion MRI streamline count (dMRI-Count), diffusion MRI fractional anisotropy (dMRI-FA), resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI), and task-based N-Back fMRI. Colour scale –1 (blue) to + 1 (red). Only components with significant correlations are displayed. IDP imaging-derived phenotype, sMRI structural MRI, dMRI-Count, diffusion MRI streamline count, dMRI-FA diffusion MRI fractional anisotropy, rsfMRI resting-state functional MRI, PGS polygenic score.

Our heritability analysis identified numerous brain IDPs in preadolescent children that exhibit significant genetic associations with different neuroimaging modalities. While these findings align with prior studies in adults that demonstrate substantial genetic contributions to cortical, subcortical regions, and functional connectivity16,17,18, they also revealed developmental distinctions. Specifically, the heritability of brain structure and function appeared lower in children compared to adults, suggesting that genetic influences on neurodevelopment are dynamic and evolve with age, potentially due to increasing gene-environment interactions during maturation8,19. Notably, in contrast to adults—where white matter microstructure exhibits greater heritability than morphometric features10—children displayed stronger genetic influences on morphometric phenotypes, particularly volumetric measures. This developmental divergence aligns with longitudinal MRI studies that demonstrate distinct trajectories for grey and white matter: white matter volume increases steadily throughout childhood and adolescence, reflecting progressive myelination, while grey matter volume follows a more dynamic, region-specific pattern, peaking in certain areas before declining due to synaptic pruning1,20. These findings underscore the importance of considering developmental trajectories and age-specific genetic contributions to better understand the mechanisms underlying neurodevelopment.

Our SGCCA delineated several notable patterns of multivariate covariation among PGS of cognitive and mental health traits, brain IDPs of structural MRI, diffusion MRI (FA) and N-back task-based fMRI, and cognitive and behavioral phenotypes. Importantly, the brain features that emerged as significant in the SGCCA were predominantly those with higher heritability, such as total grey volume (heritability in European ancestry, 0.23) and white surface area (right: 0.37, left: 0.35). Cognitive-related PGS consistently showed robust, modality-general covariation patterns with cognitive ability phenotypes, marked by consistently positive loadings. Conversely, PGS linked to psychiatric conditions (e.g., BMI, neuroticism, smoking status, ADHD) and behavioral issues reported by children and parents (e.g., CBCL total problems, ASR parental behavioral problems) exhibited negative loadings across both the 2-block and 3-block SGCCA for all neuroimaging modalities. These findings underscore the complex, interrelated gene-brain-behavior dynamics that shape cognitive abilities and psychopathologies in children, emphasizing the critical role of genetic contributions in early neurodevelopment.

While previous studies have established associations between PGS, brain imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs), and behavioral or cognitive phenotypes, often within specific neuroimaging modalities11,15, the broader question of how these factors covary across multiple modalities has received limited attention. Specifically, there has been a lack of research detailing the strength of these correlations, the extent of variance explained, and the identification of consistent patterns across different neuroimaging techniques. Our study directly addresses this gap by systematically examining these relationships across seven different neuroimaging modalities, encompassing structural MRI, diffusion MRI, resting-state fMRI, and three task-based fMRI paradigms. We found that PGS exhibited a greater number of significant components in brain structure modalities (sMRI, dMRI streamline count), followed by resting state fMRI connectivity (rsfMRI), and N-back task fMRI. This multi-modal framework provides a nuanced understanding of the covariation patterns, emphasizing the relative contributions of genetic predispositions to brain features and phenotypic expression at multiple levels of brain organization.

Across seven neuroimaging modalities, PGS for educational attainment, IQ, and depression significantly covaried with brain measures, a pattern consistently observed in both 2-block and 3-block SGCCA. Notably, higher PGS for educational attainment were linked to greater brain volume and surface area in 2-block SGCCA, replicating previous findings11,21,22. In contrast, PGS for internalizing traits, such as neuroticism and depression, displayed significant inverse relationships with these brain measures, representing an insight into how genetic risk for emotional dysregulation may manifest in structural brain features during preadolescence.

Extending a recent CCA study using the ABCD dataset linked PGS for psychopathologies (e.g., bipolar disorder, MDD, OCD, schizophrenia, and ASD) to brain measures11, our SGCCA approach, incorporating a broader spectrum of 33 PGS that encompasses diverse genetic liabilities in children, identified covariation patterns. These included covariation patterns between PGS for psychological traits (e.g., ADHD, depression, and neuroticism), physical traits (e.g., brain volume and height), and brain structural morphometry features. For instance, we observed a negative association between the depression PGS and total grey matter volume—a finding not identified in previous studies focused solely on clinical diagnoses. This underscores the importance of integrating a comprehensive range of genetic variables, spanning clinical and dimensional phenotypes, to elucidate the complex interplay between polygenic factors and brain structure during preadolescent development.

White matter microstructure demonstrated significant genetic associations, marking a contribution of this study. The proportion of variance in diffusion MRI (dMRI) IDPs explained by SNPs was slightly lower than that for structural MRI (sMRI) morphometry (mean heritability: dMRI = 19–22%, sMRI = 22–27%). This contrasts with findings in adults, where white matter microstructure heritability often exceeds that of other modalities10. These results underscore that genetic influences on white matter microstructure differ across developmental stages, reflecting both maturational changes and the increasing role of gene-environment interactions over the lifespan.

PGS showed distinct bidirectional associations with brain connectivity, reflecting both positive and negative genetic influences. Cognition-related PGS, such as those for educational attainment, cognitive performance, and IQ, showed positive associations, whereas PGS associated with health-risk traits, including BMI, smoking, and ADHD, demonstrated negative associations. On white matter connectivity, significant associations were observed in subcortical regions, such as the putamen and thalamus, as well as cortical and frontal-temporal connections. These findings highlight the potential dual role of genetic influences in shaping critical brain development, as both positive and negative genetic factors contribute to evolving connectivity patterns during childhood and adolescence. The refinement of subcortical-cortical pathways during childhood supports the functional specialization of the cortex, enabling increasingly complex cognitive and behavioral functions23. In addition, the significant covariance between PGS and fronto-temporal connections highlights their critical role in brain development. Specifically, the uncinate fasciculus and arcuate fasciculus undergo substantial refinement during childhood and adolescence, with the uncinate fasciculus facilitating emotional and social information processing24 and the arcuate fasciculus supporting increasingly complex language comprehension and production25. The maturation of these pathways aligns with the emergence of advanced social, communicative, and cognitive abilities, underscoring their importance for adaptive developmental outcomes26.

The comparison of 2-block and 3-block SGCCA results for dMRI streamline count revealed a key distinction. While the 3-block PGS-brain-phenotype analysis showed non-significant associations with subcortical-frontal pathways, the 2-block PGS-brain analysis identified significant associations with PGS. In addition to the cognition-related PGS, PGS for brain volume showed positive loadings, while PGS for health-risk traits, such as ADHD, BMI, and mental health conditions, displayed negative loadings. These findings indicate that white matter development, particularly in subcortical-frontal pathways, may influence how behavioral and cognitive functions mature across development. Future longitudinal studies could clarify whether genetic predispositions contribute to structural connectivity changes that align with specific cognitive and behavioral outcomes over time. This divergence indicates that genetic predispositions may shape subcortical and cortical connectivity early in development, potentially establishing structural foundations for later behavioral outcomes--even before these influences manifest in observable phenotypes during preadolescence27,28. These findings align with the concept of endophenotypes, measurable biological markers that serve as intermediates between genes and behavior29,30. By identifying subtle variations in brain structure that are correlated with genetic risk, even in the absence of overt behavioral differences, we gain valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms that may link genes to observable behaviors30. Our study lays the foundation for future longitudinal research to explore how these brain regions develop over time and to uncover their role in shaping cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

The emotional N-back task fMRI results revealed significant positive loadings for fusiform gyrus activation during the 0-back, 2-back, and emotion conditions with cognitive performance and IQ PGS, alongside negative loadings with neuroticism and smoking status PGS. These findings align with prior research emphasizing the fusiform gyrus’s role in working memory tasks, particularly its interaction with dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation as a key determinant of individual working memory capacity31. Our SGCCA results suggest a solid genetic basis for this association, implying that the relationship of the educational attainment PGS with fusiform gyrus activation during working memory tasks may be indicative of broader brain circuitry involvement. It is essential to recognize that the fusiform gyrus’s functional representation is intricately connected to its anatomical pathways extending throughout the brain32 (perhaps applicable to other functional domains and circuits33). Furthermore, the covariation patterns observed between the educational attainment PGS and widespread brain structure and connectivity indicate that genetic influences on cognitive abilities may shape the broader neural architecture, subsequently impacting fusiform gyrus activation. This proposed mechanism, while requiring further exploration, underscores the critical role of genetic factors in shaping brain function during cognitive tasks.

Our findings highlight distinct gene-brain-behavior associations that differ between structural and functional properties of the developing brain in children. Structural brain IDPs (e.g., sMRI volumes, dMRI FA, and streamline count) exhibited significant positive associations with cognitive performance (e.g., NIH Toolbox) and negative associations with psychopathology symptoms (e.g., CBCL). These findings are consistent with previous studies suggesting that structural brain anatomy is important for cognitive development and mental health risk during childhood34,35.

In comparison, functional MRI estimates demonstrated similar associations with cognition and psychopathology but exhibited greater associations with environmental adversity compared with structural IDPs. Functional MRI indices exhibited significant negative associations with parental psychopathology (ASR scores), negative socioeconomic environment (e.g., low median family income, higher ADI rates indicating poverty), and familial history of mental illness —findings that concur with prior developmental studies36,37. Notably, smaller functional connectivity within the default mode network (DMN) and lower task-based activation, particularly in the MID and N-back tasks, were observed in children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds with higher parental depression scores. Such heightened sensitivity suggests that functional brain networks may serve as dynamic markers responsive to environmental stressors, potentially related to the trajectory of cognitive and emotional development over time.

The functional MRI findings further lend support to a gene-by-environment (G × E) interaction framework, highlighting the interplay of genetic predispositions and environmental contexts in shaping neurodevelopmental outcomes. Our 3-way CCA results suggest that children with genetic risks for depression and neuroticism show reduced activation during the emotional N-back task—particularly in regions such as the inferior parietal cortex—and that these associations become more pronounced under adverse conditions, including prenatal tobacco exposure. This correlational pattern also aligns with lower cognitive and behavioral performance, pointing to a potential G×E mechanism that selectively impacts cortical functioning in affective memory contexts. Although these data do not imply causality, they extend prior findings linking specific SNPs (e.g., 5-HTTLPR), environmental adversity, and alterations in prefrontal–limbic circuits38,39. Future longitudinal and multi-omic (e.g., transcriptomic, epigenetic) investigations could help clarify whether, and how, these genetic susceptibilities interact with environmental stressors to shape children’s emotional and cognitive development over time.

Our findings also underscore the importance of nurturing environmental factors—such as positive parenting, supportive social relationships, and stable community settings—in shaping functional brain measures implicated in emotion perception and reward processing40,41. We identified multiple contextual variables—such as planned pregnancy, higher maternal age, and higher median income (0.532 in emotional N-back fMRI, 1st component)—that positively correlated with functional brain estimates. These results imply that supportive environmental contexts are linked to beneficial functional brain characteristics, indicating an avenue for further exploration into how such contexts foster healthier neurodevelopmental trajectories.

Our findings reveal distinct gene-brain-behavior associations based on brain structure and function. Brain structural measures, including sMRI, dMRI FA, and dMRI streamline count, exhibited positive associations with cognitive scores (e.g., NIH Toolbox), while negative associations were found with children’s psychopathology symptoms (CBCL). This pattern supports the view that brain structure, particularly during childhood, provides a foundational scaffold for cognitive abilities, while deviations from typical structural development may increase vulnerability to psychopathology42,43. In contrast, for brain function (rsfMRI, task fMRI: N-back, MID, SST), positive associations emerged with cognitive scores and socio-economic factors, such as median family income, median monthly mortgage, and the proportion of highly educated individuals in the region. Negative associations were found not only with children's psychopathology (CBCL) but also with parental psychopathology (ASR), poverty indicators (e.g., ADI rate below 138% poverty level), and family history of mental illness. This suggests that brain function, while influenced by genetic factors, is also highly malleable and susceptible to a wider range of environmental influences, including socioeconomic status, family environment, and exposure to adversity44,45,46. Notably, these negative associations with parental mental health issues and community-level socio-economic factors were significant only in relation to brain function, not brain structure. This distinction perhaps arises from the greater plasticity of brain function compared to structure, particularly during childhood, allowing for more dynamic adaptation to environmental influences47,48. These findings highlight the interplay between genetics, brain activity, and environmental factors in shaping cognitive and mental health outcomes, emphasizing the need for a multi-level perspective that encompasses both biological and contextual influences.

In predicting mental illness variables, PGS contributed minimally. Recent studies have cast doubt on the prognostic value of PGS for psychopathologies in adults49,50,51, also in children, where psychiatric symptoms are not yet fully developed52. Our results similarly indicated that PGS did not significantly improve the prediction of most psychiatric outcomes, except for youth-reported depression, which showed a modest 3% improvement in performance. Notably, IQ, PTSD, and smoking status were among the top predictors in the depression model. It warrants further investigation to understand the developmental trajectory of PGS-psychopathology associations.

While PGS models exhibit modest predictive power for individual traits, their broader utility lies in uncovering genetic contributions to complex brain-behavior relationships and facilitating the modeling of gene-by-environment interactions. By leveraging CCA, our study highlighted the ability of PGS to identify modality-spanning genetic influences and their interaction with environmental factors, emphasizing their relevance in examining developmental trajectories and context-dependent effects. PGS are particularly effective in stratifying populations into genetic risk groups53,54, providing a foundation for exploring how genetic predispositions interact with socioeconomic, environmental, or lifestyle variables. Furthermore, the predictive strength of PGS is enhanced when integrated with complementary datasets55, such as neuroimaging, behavioral, or environmental metrics, allowing for more nuanced modeling of the dynamic interplay between genes and context. These findings underscore the potential of PGS not only as a tool for understanding brain phenotypes but also for advancing research on the intricate interactions that shape cognitive and mental health outcomes.

Limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, the gene-brain-behavior relationships we examined are likely non-linear, yet our approach primarily relied on linear models, which may not adequately capture the intricate and dynamic nature of these interactions. Future research should explore advanced analytical frameworks, such as non-linear or machine learning-based approaches, to better model these complexities. Second, while polygenic scores (PGS) provide a robust summary of genetic predisposition by aggregating allele effects across SNPs, they may fail to capture broader patterns involving post-genomic modifications, including transcriptomic, epigenomic, or proteomic influences. Incorporating these factors would enable a more comprehensive understanding of the biological pathways underlying the observed relationships. Finally, the cross-sectional design of our study limits our ability to infer causality or investigate developmental changes in gene-brain-behavior associations over time. Longitudinal studies are essential to unravel the temporal dynamics and causal pathways connecting genetic variation, brain phenotypes, and cognitive or behavioral outcomes. Addressing these limitations in future work will deepen our understanding of neurodevelopment and advance the field’s capacity to model complex genetic and environmental influences.

Methods

Participants

This study complied with all relevant ethical regulations. The Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development (ABCD) study received ethical approval from the institutional review boards at all participating sites, coordinated by the University of California, San Diego. The secondary analysis of ABCD data conducted in this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants' parents or legal guardians, and assent was obtained from the children themselves. Participants received monetary compensation according to the original ABCD study protocol.

We used multimodal neuroimaging, DNA genotype data, and cognitive and behavioral metrics of 11,875 multi-ancestry children (47.8% female, mean age 9.9 years) from the ABCD study. Participants' sex information was obtained through parental self-report. The ABCD study is a nationwide longitudinal cohort study to investigate the normative brain and cognitive development of preadolescent youths from ages 9 to 10 from 21 sites across the United States56,57. The study provides a rich repository of multimodal biomedical datasets such as DNA genotype, multimodal neuroimaging data, and matched cognitive, behavioral and clinical data. As our analysis aimed to investigate general neural correlates without specific hypotheses regarding sex differences, sex-specific analyses were not performed.

Genetic data

The ABCD study collected and genotyped the participants' saliva samples at Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository (RUCDR) using the Affymetrix SmokeScreen Array consisting of 733,293 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). We applied standard PLINK filters for genotype call rate (<95% removed), sample call rate (<95% removed), and minor allele frequency (MAF <1% removed). Genotypes were imputed toward the 1000 Genome phase3 reference panel12 using the Michigan Imputation Server58, and the output was phased with Eagle v2.414 (a total of 12,046,090 SNPs). After imputation, we additionally removed any inferior SNPs with low imputation score (INFO score < 0.4), genotype call rate <95%, Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium p-value < 1E-20 for diverse ancestral population, sample missingness >5%, minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.5%, and extreme heterozygosity (over three standard deviations of the population mean). After this step, 11,221,810 variants remained.

Relatedness inference

Since the ABCD study participants have diverse ancestral backgrounds and genetic ancestries, we performed an additional quality control (QC) process to thoroughly address potential population stratification due to genetic relatedness and ancestry admixture. To remove potential confounds of the family structure, we identified genetically unrelated individuals and computed the ancestrally informative principal components (PCs) of their genotype data using the SNPRelate R package58. Two rounds of principal component analysis (PCA) were conducted using the PC-Air algorithm that is robust to familial or cryptic relatedness. We first obtained initial estimates of pairwise kinship coefficients using the KING-robust algorithm, using a pruned set of independent genetic variants using an LD threshold of R2 < 0.1. We identified genetically related individuals with closer than 3rd degree relatives (kinship threshold = 2(−9/2), which defines anyone less than first cousins as ‘unrelated’) and only retained one individual per related pair and kept the excluded individual as an independent validation set (n = 1814). PC-Air identified the unrelated set of 8845 individuals based on the pairwise kinship estimates, and systematically computed the PC of their genotype data. PC-Relate was used to compute new kinship estimates adjusting for ancestry, which is robust to population structure and admixture in estimating genetic relatedness. The 2nd round of PC-Air computed accurate PCs with the modified unrelated set. We further excluded 88 participants whose projected PCs had the Mahalanobis distances greater than 6SDs from further analysis. In conclusion, the final set of 8620 unrelated individuals was used for the main analysis. The excluded 1814 individuals from the relatedness analysis were additionally assessed for their 3rd degree relatedness, and the final unrelated set of 1579 individuals were kept for the independent validation set for PGS optimization.

Construction of Genome-Wide Polygenic Scores (PGS)

To estimate polygenic liability of complex traits for each individual, we constructed 33 different cognitive, psychological, and psychiatric traits: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)59, cognitive performance (CP)60, educational attainment (EA)60, major depressive disorder (MDD)61, insomnia61, snoring62, intelligence quotient (IQ)63,64, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)62, depression65, body mass index (BMI)63,64, height66, alcohol dependence (alcohol use)67, autism spectrum disorder (ASD)68, automobile speeding propensity (ASP)69,70, bipolar disorder71, cannabis during lifetime (cannabis use)72, ever smoker (smoking status)65, shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders (cross disorder)73, alcoholic consumption per week (drinking)65, eating disorder67, neuroticism74, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)68, first principal components of four risky behaviors (PC of risky behaviors)65, general risk tolerance65, schizophrenia75,76, worrying74, subjective wellbeing77, general happiness, general happiness for health (happiness-health), meaningful life (happiness-life), grey matter volume (GM)78, white matter volume (WM)78, and total brain volume (TBV)78. We collected the GWAS summary statistics of 33 complex traits from publicly available resources listed in Supplementary Data 1. For better cross-population polygenic prediction, PRS-CSx (June 4, 2021 release)79, a recently developed Bayesian polygenic modeling technique, was used to construct the PGS for our multi-ancestry study participants. The method is known for its effective posterior inference algorithm, considering population-specific allele frequencies and LD patterns by adopting a shared continuous shrinkage prior. The LD reference panel of European (EUR), Admixed Americans (AMR), African (AFR), East Asian (EAS), and South Asian (SAS) from the 1000 Genome Project phase 3 was utilized in accordance with the discovery GWAS sample for PGS construction. Though PRS-CSx could automatically estimate the parameter, we applied a small-scale grid search of the global shrinkage parameter for whose target phenotype is available within the study dataset for better performance.

Validation of Genome-Wide Polygenic Scores (PGS)

To estimate the optimal PGS, we manually tuned the best-performing global shrinkage hyperparameter to maximize the explained variance of the PGS on the corresponding phenotype available in the ABCD datasets. For example, the ADHD behavioral measure of the ABCD study was used to choose the best version of the PGS of ADHD with optimal hyperparameters. In this way, we optimized PGS of 17 traits by choosing the optimal global shrinkage hyperparameter (φ, phi) in an independent held-out validation set of 1579 unrelated participants, which were removed during the QC process of relatedness analysis. We examined the effect size and significance of the PGS variable in a linear regression model with different phi values, results from the small-scale grid search (φ = 1e-6, 1e-4, 1e-2, 1). Each target outcome variable was regressed on the relevant PGS, sex, top 10 principal components (PCs) of genotype data, and genetic ancestry. We chose the final φ value of the regression model, maximizing the effect size (β coefficient) of the PGS and R2 of the model. For example, when the φ value is 1, the regression model would be:

For six complex traits (i.e., BMI, PTSD, depression, schizophrenia, alcohol dependence, and height), whose GWAS summary statistics were available in both European- and non-European-ancestry participants, we built multi-ancestry PGS combining the GWAS summary statistics of two or more ancestries by learning the optimal linear combination of the ancestry-specific PGS that were used as predictors. For example, when the φ value of European-ancestry-based PGS is 1, and that of Admixed-American-based PGS is 1e-2, the regression model would be:

After optimal PGS were built, we assessed the validity of the final PGS in 8620 participants, the sample for our main analysis, adjusting for sex, age, and study site. Genetic ancestry was added as an additional covariate in tuning the multi-ancestry PGS. For the 16 GWAS traits that have sufficient discovery GWAS sample or do not have target outcome variables in the ABCD study, we performed pseudo-validation using PRS-CS-auto, in which the hyperparameter φ is automatically selected from data with a fully Bayesian approach80.

Neuroimaging data

We used different modalities of neuroimaging data available from the ABCD study, including structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI), diffusion connectivity measures (dMRI), resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI), and task functional MRI data (task fMRI). For structural MRI (sMRI), we processed T1-weighted (T1w) 3D images using FreeSurfer v6.0 (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). The gradient nonlinearity distortion correction, non-uniformity correction using tissue segmentation and sparse spatial smoothing were performed. The resampled data is aligned to 1 mm isotropic voxels. After excluding global brain measures (i.e., total intracranial volume (TIV)), we used cortical and subcortical surface area, volume, thickness, and mean curvature in the analysis. The Desikan-Killiany atlas was used to extract brain regions. For diffusion-weighted imaging (dMRI), we used preprocessed diffusion spectrum images from the ABCD study and applied MRtrix3 to estimate whole-brain white matter tracts and create individualized connectomes81. We corrected for motion and distortion using standard methods, including B0 distortion and gradient nonlinearity corrections82. We performed noise reduction, bias correction, and probabilistic tractography to map the brain’s white matter pathways. A whole-brain connectome matrix for each participant was generated based on their neuroanatomy using FreeSurfer. Connectivity was assessed using streamline counts and fiber integrity metrics. For the resting-state functional MRI acquisition, we used pair-wise correlation coefficients between each cortical and subcortical region of interest (ROI) and network. For task fMRI, we used three tasks: the emotional version of N-back (N-back)83, the monetary incentive delay task (MID)84, and the stop-signal task (SST)84,85. To ensure data quality, we excluded individuals who had more than 10% missing data in any of the neuroimaging modalities, resulting in the removal of 559 children from the analysis. In addition, we removed low-frequency variables that exhibited zero variance or had less than 100 observations among the participants.

Non-imaging measures and data processing

We examined the baseline non-imaging measures of mental and physical health, neurocognition, culture and environment factors in ABCD participants to explore their links with polygenic liability86. For assessing the mental wellbeing of the children87, we used a parent version of Kiddie-Structured Assessment for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for DSM-5 (KSADS-5) and Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL), which assess a wide range of emotional and behavioral aspects of the youths in the previous six months, including their mood, psychosis, anxiety, suicidality, behavioral and sleep problems. We also used Parent General Behavioral Inventory – mania (PGBI), Prodromal Psychosis Scale (PPS), Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Approach System (BIS/BAS) scales, and UPPS Impulsive Behavioral scale for children (UPPS-P). For assessing physical well-being, we retrieved a lifetime medical history, head injury experiences, developmental medical records of the youth, experiences about sleep problems, pain, and exercises. For assessing neurocognition, we used the NIH Toolbox measurement, which consists of seven domain-specific tasks assessing episodic memory, executive function, attention, working memory, processing speed, and language and vocabulary abilities of the children88,89. We used age-uncorrected task scores of the NIH Toolbox and included age as a covariate for further analysis. Also, we considered school attributes, population density, neighborhood walkability, and area deprivation indices of the children’s households and neighborhood as part of the culture and environment phenotype block, which were reported directly by the youth or parent/caregiver. The description of all phenotypic variables included in our analyses is in Supplementary Data 2.

Except for a few mental health phenotypes, the average missingness in the non-imaging phenotype block was around 3%. Missing values were manually imputed using the mode for categorical variables and the median for continuous variables (Supplementary Data 3). We also left bothering scales of prodromal psychosis not imputed, coded only when one has at least one prodromal psychotic symptom. We identified and removed any non-imaging variables with high correlation with other variables (Pearson’s r > 0.95) or zero variance, resulting in the removal of 6 variables related to mental well-being and 1 cultural variable.

SNP-Based heritability

We estimated the SNP-based heritability of imaging and non-imaging phenotypes and the genetic correlation among these traits in children. The genetic relationship matrix (GRM) was generated from imputed and autosomal SNPs using GCTA v1.93, quantifying addictive genetic relatedness between pairs of participants. GCTA’s Restricted Maximum Likelihood algorithm used the GRM to estimate the variance explained by all SNPs for each trait. The significance of the estimates was determined using a likelihood ratio test, which compared the likelihood of the alternative to that of the null hypothesis.

During the preprocessing step, we identified and excluded features with zero variance and outliers greater than 5 median absolute deviations (MAD) from the median. All the phenotype data were quantile transformed.

In testing heritability, we included age, sex, age², age*sex, age²*sex, self-reported ethnicity, genetic-based ancestry, the first ten principal components (PCs) of genotype data, and study site as covariates for each phenotype10. We also applied additional imaging modality-specific covariates for the different modality of brain IDPs: (1) For structural MRI, signal-to-noise ratio of T1 and T2 brain mask across all OK scans, (2) For diffusion MRI, signal-to-noise ratio of b = 0 image for all OK scans, mean intensity within brain mask averaged across all OK scans, the total number of censored slices in all frames for all OK scans, (3) For resting-state fMRI, signal to noise ratio within the brain of all OK scans, mean framewise displacement in mm, (4) For task-based fMRI (SST, N-back, MID): signal to noise ratio within the brain of all OK scans, average framewise displacement in mm. To validate the reliability of our results, we performed the analysis in the participants with European and multi-ancestry, respectively.

Sparse generalized canonical correlation analysis (SGCCA)

SGCCA is a useful approach to explore the multivariate associations between high dimensional datasets and identify key canonical variables from each block that significantly influence their correlation with other blocks90,91. This approach is particularly suitable for genomic-brain studies, as it effectively handles the challenges posed by high-dimensionality, multicollinearity, and overfitting92.

The sparsity assumption in SGCCA aligns with the biological plausibility observed in genetic studies, where only a subset of genetic variants typically has meaningful impacts on complex traits like brain structure and function93. SGCCA assumes that a limited number of variables drive the most significant associations, which enables the model to provide stable and interpretable insights into genomic contributions to IDP (imaging-derived phenotypes) variation94 This sparsity-based approach not only enhances interpretability by isolating key associations but also effectively addresses the high degree of multicollinearity among SNPs and IDPs, a limitation often encountered in traditional CCA models.

In SGCCA, datasets are organized into blocks, where each block represents a set of variables observed on the same individuals. We conducted SGCCA between the genomic block comprising the PGS of 33 traits on the one hand, and each of seven neuroimaging data modality blocks (sMRI, dMRI (streamline count, FA), resting-state fMRI, and task fMRI (MID, SST, N-back)) and a non-imaging phenotype block on the other hand.

To adjust for potential confounding effects, we took the residuals of the outcome variables after regressing out the baseline age, sex, age2, age*sex, age2*sex, self-reported ethnicity and study site. The primary analyses were conducted on European-ancestry individuals with both imaging and DNA genotype data, comprising 7143 for dMRI (streamline count), 7068 for dMRI (FA), 6792 for sMRI, 6855 for MID tfMRI, 6749 for SST tfMRI, 6690 for Nback tfMRI, and 7782 for resting-state fMRI. Supplementary analyses extended to multi-ancestry participants, with increased sample size including 9122 for dMRI (streamline count), 9016 for dMRI (FA), 8582 for sMRI, 8646 for MID tfMRI, 8522 for SST tfMRI, 8438 for Nback tfMRI, and 7782 for resting-state fMRI.

The analysis is performed using the RGCCA R package (Regularized Generalized Canonical Correlation Analysis)91. First, regularization (sparsity) was tuned using permutation testing (100 permutations) by randomly shuffling the participant data to determine the optimal level of sparsity for each modality. This regularization reduces overfitting by selecting only the most relevant variables, addressing the challenge of multicollinearity among SNPs and IDPs. After tuning, SGCCA analyses were conducted, generating five canonical components per block. This number was chosen after preliminary experiments to maximize the cumulative variance explained across imaging and non-imaging modalities.

To assess the statistical significance of each component, we conducted a permutation test with 1000 permuted datasets. The p-values of each component were estimated based on the number of permuted datasets having covariance greater than the covariance from the original dataset. All p-values were adjusted with FDR correction. Covariance and Pearson correlation coefficients between blocks were presented in the results section.

We calculated the loadings of the PGS variables and corresponding variables (e.g., phenotypes). To examine the reliability of loadings estimated from SGCCA, the bootstrap approach was used (bootstrap n = 1000) to evaluate the mean, variance, and confidence intervals of the estimates across the bootstrap samples. To generate stable results, we averaged the canonical weights across ten folds. The statistical significance (p-value) of each loading was estimated based on the following null hypothesis: Fisher transformation of loading will follow normal distribution of N(0, σ2), where σ is the estimated standard deviation of Fisher-transformed loading from bootstrap samples. To assess the cross-population generalizability of our findings, we repeated the analysis in the entire participants with multiple genetic ancestries, that mostly includes individuals of European-ancestry, but also the subjects of Asian-ancestry (n = 112, 1.34%) and African-ancestry (n = 1361, 16.3%). Genetic ancestry was additionally included as a covariate for multi-ancestry analysis.

PGS-based prediction of phenotypes using machine learning

We evaluated the prognostic utility of the PGS on cognitive and mental health outcomes at baseline and at the 2-year follow-up in 6555 European-ancestry and 8620 multi-ancestry participants using several machine learning techniques. We employed an XGBoost model (version 2.1.3) in Python95 to construct prediction models. We manually chose nine psychological outcomes for our machine learning-based prediction models based on the results from the preceding CCA analysis, including nine psychiatric conditions (i.e., KSADS-5 ADHD, parent and child reports of any psychiatric disorders, any depressive disorders, any anxiety disorders, and suicidal behaviors).

The data were split into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets using stratified sampling to preserve outcome distributions. Stratified 5-fold cross-validation validated the model, with quartile binning for continuous outcomes and stratification for binary outcomes. Missing data were imputed using the mode for categorical variables and the median for continuous variables, with records missing age excluded. Continuous variables were adjusted to maintain similar distributions across subsets, and binary variables were stratified to preserve proportional outcome proportions. To enhance robustness, each variable underwent 30 repeated experiments using the same subject samples, ensuring consistency in the results. Cognitive outcomes with over 80% of values concentrated in a single category were excluded from regression analysis (i.e., nihtbx_cardsort_uncorrected_2yr, nihtbx_list_uncorrected_2yr, nihtbx_fluidcomp_uncorrected_2yr, and nihtbx_totalcomp_uncorrected_2yr).

Hyperparameter tuning for the XGBoost model was performed using grid search, focusing on five parameters: learning rate, maximum depth, minimum child weight, subsample, and column sampling by tree. Model performance was evaluated using AUC for binary outcomes, with early stopping to enhance validation. Feature importance, derived from the gbtree booster, highlighted input variable contributions.

Basic demographic variables (i.e., sex, age, household income, parental education, marital status, and study site) were used as input features of the baseline model in European-ancestry analysis, and we included genetic ancestry information as an additional covariate for multi-ancestry prediction. We evaluated the predictive performance of the PGS-based model in comparison to the baseline model fitted with demographic variables.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study via the National Institute of Mental Health Data Archive (NDA; https://nda.nih.gov/abcd/request-access) upon formal application and approval by the ABCD consortium. Individual-level genotype and imaging data cannot be publicly shared due to privacy protection, conditions stipulated by the ABCD data-use agreement, and compliance with federal privacy regulations for protecting personally identifiable information. Synthetic data mimicking the cohort structure, consisting of 100 randomly sampled participants, are provided for demonstration purposes and can be downloaded from the following external repository: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1M-uzD1k1IiEXAbrHxE_vYVaWtiq4AHx2?ths=true. The discovery GWAS summary statistics used to derive the PGS are available through the original publications cited in Supplementary Data 1.

Code availability

The code used for genetic data processing, polygenic score construction, heritability estimation, and multivariate analyses is available at https://github.com/Transconnectome/abcd-gps/tree/main. The repository includes sample scripts for reproducibility and analysis workflows using synthetic data.

References

Giedd, J. N. et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 861–863 (1999).

Bethlehem, R. A. et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature 604, 525–533 (2022).

Hughes, D. E. et al. Genetic patterning for child psychopathology is distinct from that for adults and implicates fetal cerebellar development. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 959–969 (2023).

Ohi, K. et al. Polygenic risk scores for major psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders contribute to sleep disturbance in childhood: Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. Transl. Psychiatry 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01308-8 (2021).

Wainberg, M., Jacobs, G. R., Voineskos, A. N. & Tripathy, S. J. Neurobiological, familial and genetic risk factors for dimensional psychopathology in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 2731–2741 (2022).

Maglanoc, L. A. et al. Brain connectome mapping of complex human traits and their polygenic architecture using machine learning. Biol. Psychiatry 87, 717–726 (2020).

Plomin, R. & von Stumm, S. The new genetics of intelligence. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 148–159 (2018).

Bergen, S. E., Gardner, C. O. & Kendler, K. S. Age-related changes in heritability of behavioral phenotypes over adolescence and young adulthood: a meta-analysis. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 10, 423–433 (2007).

Brouwer, R. M. et al. Genetic influences on individual differences in longitudinal changes in global and subcortical brain volumes: Results of the ENIGMA plasticity working group. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38, 4444–4458 (2017).

Elliott, L. T. et al. Genome-wide association studies of brain imaging phenotypes in UK Biobank. Nature 562, 210–216 (2018).

Fernandez-Cabello, S. et al. Associations between brain imaging and polygenic scores of mental health and educational attainment in children aged 9–11. NeuroImage 263, 119611 (2022).

Auton, A. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

Conomos, M. P., Miller, M. B. & Thornton, T. A. Robust inference of population structure for ancestry prediction and correction of stratification in the presence of relatedness. Genet. Epidemiol. 39, 276–293 (2015).

Conomos, M. P., Reiner, A. P., Weir, B. S. & Thornton, T. A. Model-free estimation of recent genetic relatedness. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 127–148 (2016).

Modabbernia, A., Janiri, D., Doucet, G. E., Reichenberg, A. & Frangou, S. Multivariate patterns of brain-behavior-environment associations in the adolescent brain and cognitive development study. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 510–520 (2021).

Baaré, W. F. et al. Quantitative genetic modeling of variation in human brain morphology. Cereb. Cortex 11, 816–824 (2001).

Roshchupkin, G. V. et al. Heritability of the shape of subcortical brain structures in the general population. Nat. Commun. 7, 13738 (2016).

Shen, K.-K. et al. Investigating brain connectivity heritability in a twin study using diffusion imaging data. NeuroImage 100, 628–641 (2014).

Schmitt, A., Malchow, B., Hasan, A. & Falkai, P. The impact of environmental factors in severe psychiatric disorders. Front. Neurosci. 8, 19 (2014).

Mills, K. L. et al. Structural brain development between childhood and adulthood: Convergence across four longitudinal samples. Neuroimage 141, 273–281 (2016).

Merz, E. C. et al. Educational attainment polygenic scores, socioeconomic factors, and cortical structure in children and adolescents. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 4886–4900 (2022).

Judd, N. et al. Cognitive and brain development is independently influenced by socioeconomic status and polygenic scores for educational attainment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 12411–12418 (2020).

Park, S. et al. A shifting role of thalamocortical connectivity in the emergence of cortical functional organization. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 1609–1619 (2024).

Von Der Heide, R. J., Skipper, L. M., Klobusicky, E. & Olson, I. R. Dissecting the uncinate fasciculus: disorders, controversies and a hypothesis. Brain 136, 1692–1707 (2013).

Brauer, J., Anwander, A. & Friederici, A. D. Neuroanatomical prerequisites for language functions in the maturing brain. Cereb. Cortex 21, 459–466 (2011).

Lebel, C. & Beaulieu, C. Longitudinal development of human brain wiring continues from childhood into adulthood. J. Neurosci. 31, 10937–10947 (2011).

Saygin, Z. M. et al. Connectivity precedes function in the development of the visual word form area. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1250–1255 (2016).

Giedd, J. N. et al. Anatomic magnetic resonance imaging of the developing child and adolescent brain and effects of genetic variation. Neuropsychol. Rev. 20, 349–361 (2010).

Miller, G. A. & Rockstroh, B. Endophenotypes in psychopathology research: where do we stand?. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 177–213 (2013).

Lenzenweger, M. F. Thinking clearly about the endophenotype-intermediate phenotype-biomarker distinctions in developmental psychopathology research. Dev. Psychopathol. 25, 1347–1357 (2013).

Neta, M. & Whalen, P. J. Individual differences in neural activity during a facial expression vs. identity working memory task. Neuroimage 56, 1685–1692 (2011).

Saygin, Z. M. et al. Anatomical connectivity patterns predict face selectivity in the fusiform gyrus. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 321–327 (2012).

Cha, J. et al. Circuit-wide structural and functional measures predict ventromedial prefrontal cortex fear generalization: implications for generalized anxiety disorder. J. Neurosci. 34, 4043–4053 (2014).

Jansen, A. G., Mous, S. E., White, T., Posthuma, D. & Polderman, T. J. What twin studies tell us about the heritability of brain development, morphology, and function: a review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 25, 27–46 (2015).

Geng, X. et al. White matter heritability using diffusion tensor imaging in neonatal brains. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 15, 336–350 (2012).

Tomasi, D. & Volkow, N. D. Effects of family income on brain functional connectivity in US children: associations with cognition. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 4195–4202 (2023).

Achterberg, M. et al. Distinctive heritability patterns of subcortical-prefrontal cortex resting state connectivity in childhood: A twin study. Neuroimage 175, 138–149 (2018).

van der Meer, D. et al. The interaction between 5-HTTLPR and stress exposure influences connectivity of the executive control and default mode brain networks. Brain Imaging Behav. 11, 1486–1496 (2017).

Gee, D. G. et al. Maternal buffering of human amygdala-prefrontal circuitry during childhood but not during adolescence. Psychol. Sci. 25, 2067–2078 (2014).

Kopala-Sibley, D. C. et al. Early childhood parenting predicts late childhood brain functional connectivity during emotion perception and reward processing. Child Dev. 91, 110–128 (2020).

Chaplin, T. M., Mauro, K. L. & Niehaus, C. E. in Neuroscience of Social Stress, 341–372 (2021).

Shaw, P. et al. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature 440, 676–679 (2006).

Gogtay, N. et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 8174–8179 (2004).

Hackman, D. A., Farah, M. J. & Meaney, M. J. Socioeconomic status and the brain: mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 651–659 (2010).

Luby, J. et al. The effects of poverty on childhood brain development: the mediating effect of caregiving and stressful life events. JAMA Pediatr. 167, 1135–1142 (2013).

McEwen, B. S. & Gianaros, P. J. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1186, 190–222 (2010).

Knudsen, E. I. Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 16, 1412–1425 (2004).

Kolb, B., Mychasiuk, R., Muhammad, A. & Gibb, R. Brain Plasticity in the Developing Brain. Prog. Brain Res 207, 35–64 (2013).

Wray, N. R. et al. From basic science to clinical application of polygenic risk scores: a primer. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 101–109 (2021).

Krapohl, E. et al. Multi-polygenic score approach to trait prediction. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 1368–1374 (2018).

Landi, I. et al. Prognostic value of polygenic risk scores for adults with psychosis. Nat. Med. 27, 1576–1581 (2021).

Solmi, M. et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 281–295 (2022).

Mavaddat, N. et al. Polygenic risk scores for prediction of breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet 104, 21–34 (2019).

Kullo, I. J. et al. Polygenic scores in biomedical research. Nat. Rev. Genet 23, 524–532 (2022).

Dudbridge, F., Pashayan, N. & Yang, J. Predictive accuracy of combined genetic and environmental risk scores. Genet Epidemiol. 42, 4–19 (2018).

Garavan, H. et al. Recruiting the ABCD sample: Design considerations and procedures. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 16–22 (2018).

Casey, B. J. et al. The adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study: imaging acquisition across 21 sites. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 43–54 (2018).

Zheng, X. et al. A high-performance computing toolset for relatedness and principal component analysis of SNP data. Bioinformatics 28, 3326–3328 (2012).

Demontis, D. et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Genet. 51, 63–75 (2019).

Lee, J. J. et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat. Genet. 50, 1112–1121 (2018).

Wray, N. R. et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 50, 668–681 (2018).

Jansen, P. R. et al. Genome-wide analysis of insomnia in 1,331,010 individuals identifies new risk loci and functional pathways. Nat. Genet. 51, 394–403 (2019).

Locke, A. E. et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 518, 197–206 (2015).

Akiyama, M. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 112 new loci for body mass index in the Japanese population. Nat. Genet. 49, 1458–1467 (2017).

Karlsson Linnér, R. et al. Genome-wide association analyses of risk tolerance and risky behaviors in over 1 million individuals identify hundreds of loci and shared genetic influences. Nat. Genet. 51, 245–257 (2019).

Yengo, L. et al. A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature 610, 704–712 (2022).

Walters, R. K. et al. Transancestral GWAS of alcohol dependence reveals common genetic underpinnings with psychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1656–1669 (2018).

Grove, J. et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Genet. 51, 431–444 (2019).

Howard, D. M. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 343–352 (2019).

Shen, H. et al. Polygenic prediction and GWAS of depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation/self-harm in a Peruvian cohort. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 1595–1602 (2020).

Stahl, E. A. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nat. Genet. 51, 793–803 (2019).

Pasman, J. A. et al. GWAS of lifetime cannabis use reveals new risk loci, genetic overlap with psychiatric traits, and a causal influence of schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1161–1170 (2018).

Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, C Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet 381, 1371–1379 (2013).

Nagel, M. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat. Genet. 50, 920–927 (2018).

Bipolar, D. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Cell 173, 1705–1715 (2018).

Lam, M. et al. Comparative genetic architectures of schizophrenia in East Asian and European populations. Nat. Genet. 51, 1670–1678 (2019).

Okbay, A. et al. Genetic variants associated with subjective well-being, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism identified through genome-wide analyses. Nat. Genet. 48, 624–633 (2016).

Zhao, B. et al. Genome-wide association analysis of 19,629 individuals identifies variants influencing regional brain volumes and refines their genetic co-architecture with cognitive and mental health traits. Nat. Genet. 51, 1637–1644 (2019).

Ruan, Y. et al. Improving polygenic prediction in ancestrally diverse populations. Nat. Genet. 54, 573–580 (2022).

Ge, T., Chen, C. Y., Ni, Y., Feng, Y. A. & Smoller, J. W. Polygenic prediction via Bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nat. Commun. 10, 1776 (2019).

Tournier, J. D. et al. MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. Neuroimage 202, 116137 (2019).

Kim, K. et al. The sexual brain, genes, and cognition: A machine-predicted brain sex score explains individual differences in cognitive intelligence and genetic influence in young children. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 3857–3872 (2022).

Cohen, A., Conley, M., Dellarco, D. & Casey, B. The impact of emotional cues on short-term and long-term memory during adolescence. In Proceedings of the Society for Neuroscience. (2016).

Knutson, B., Westdorp, A., Kaiser, E. & Hommer, D. FMRI visualization of brain activity during a monetary incentive delay task. Neuroimage 12, 20–27 (2000).