Abstract

Catalytic multicomponent carbonylation reactions with high regio- and chemoselectivity represent one of the long-pursued goals in C1 chemistry. We herein disclose a practical cobalt-catalyzed divergent radical alkene carbonylative functionalization under 1 atm of CO at 23 °C. The leverage of the tridentate NNN-type pincer ligand is the key to avoid the formation of catalytically inert Co0(CO)n species and overcome the occurrence of oxidative carbonylation of organozincs, selectively tuning the catalytic reactivity of cobalt center for dictating a full cobalt-catalyzed four-component carbonylation. Moreover, direct use CO2 as the C1 source in the multicomponent alkene carbonylative couplings can be achieved under a tandem electro-thermo-catalysis, thus allowing us to rapidly and reliably construct unsymmetric ketones with ample scope and excellent functional group compatibility. Remarkably, our protocol encompasses a broader of polyhaloalkanes as the electrophiles, which underwent radical-relay couplings in a completely regio- and chemoselective fashion. Finally, facile modifications of drug-like molecules demonstrate the synthetic utility of this method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition-metal-catalyzed carbonylation that enables straightforward access to carbogenic skeletons containing carbonyl-derived functional groups is a vital component of the synthetic toolkit, given the prevalence of such scaffolds and their widespread applications in organic synthesis, medicinal chemistry and material science1,2,3. Thus far, direct use carbon monoxide (CO) as the abundant and low-cost C1 source to the development of carbonylative synthetic methods have witnessed considerable progress during the past decades1,2,3,4,5. Whereas the noble metals (Pd, Rh, Ir, or Ru complexes) have showed good catalytic activities in various carbonylative reactions6,7,8,9, the development of catalysts based on the naturally abundant and cost-efficient 3 d transition metals represents an attractive alternative10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Among them, the industrial friendly cobalt complexes possessing versatile potential in homogeneous catalysis19,20,21,22, have received special recent attention. Since cobalt complexes showed important applications in the hydroformylation23,24 and Pauson−Khand reaction25, significant contributions have been made to further expand the cobalt-catalyzed carbonylative transformations with readily accessible starting materials. Thus far, diverse coupling reactions between the in situ formed cobalt-carbonyl intermediate I and N- or O-based nucleophiles have been well developed. Strategies including cobalt-catalyzed aminocarbonylative functionalization of alkenes26,27,28, amino- and alkoxycarbonylation of electrophiles29,30,31, as well as oxidative C − H carbonylation32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 have obtained significantly attentions by offering straightforward methods to the synthesis of amides and esters (Fig. 1a). However, the paucity of unsymmetric ketone synthesis via carbonylation between electrophiles and cobalt-carbonyl intermediate II, which formed by selective 1,1-insertion of CO with carbon-based nucleophiles, is certainly striking10,11,12. The reasons can be ascribed to the following two major challenges: i) carbon monoxide trends to coordinate with cobalt metal tightly to form catalytically inert Co0-carbonyl species (III); ii) intermediate II prefers to undergo oxidative cross-coupling process to furnish symmetric ketone41. Therefore, the use of abundant CO gas in cobalt-catalyzed carbonylation between carbon-based nucleophiles and electrophiles for unsymmetric ketone synthesis remains a challenging topic (Fig. 1b).

In recent years, direct use of CO gas in the catalytic multicomponent carbonylative reactions (MCRs)42,43,44 via radical relay pathway have emerged as an innovative strategy to rapidly synthesis value-added carbonyl compounds from simple chemical feedstocks45,46,47,48,49,50. Among them, the four-component alkylcarbonylation reaction of alkenes to the synthesis of unsymmetric ketones under nickel catalysis was only recently developed by Zhang51,52. However, due to the aforementioned issues, cobalt-catalyzed radical-relay alkene carbonylative functionalization to access versatile ketones have unfortunately thus far proven elusive. Therefore, this underdeveloped area leaves a unique chance for developing new synthetic strategy while expanding this highly rewarding scenario. To achieve this goal, we herein disclose the realization of cobalt-catalyzed divergent radical relay alkene carbonylative functionalization under 1 atm of CO at 23 °C. Indeed, the use of tridentate NNN-type pincer ligand is the key to avoid the formation of catalytically inert Co0(CO)n and overcome the occurrence of oxidative carbonylation of organozincs, thereby selectively tuning the catalytic reactivity of cobalt for steering a rapid radical relay coupling with the in situ formed acyl-cobalt intermediate.

Notably, we have also designed a practical tandem electro-thermo-catalysis, which enables directly replace CO with CO2 in this multicomponent carbonylative coupling reaction to afford a variety of functionalized ketones. Among them, a quite number of polyhalogenated electrophiles can be assigned as the radical precursors, occurring radical-relay alkene carbonylation with excellent regio- and chemoselectivity. Moreover, the salient features of our protocol include synthetic simplicity, ample substrate scope and high efficiency (Fig. 1c).

Results

Given the important role of sulfone moieties to optimize the stability, liposolubility and metabolism of various molecules with activities of relevance to medicinal chemistry53, we became interested in the development of cobalt-catalyzed alkene carbonylative sulfonylation with readily accessible tosyl chloride (1a), p-tolylzinc pivalate (3a) under 1 atm of CO. To achieve this multicomponent carbonylation reaction, our investigation was focused on the ligands screening (Fig. 2a). Initially, the utilization of representative bis(pyridine)s ligands L1‒L6, as well as tridentate nitrogen-based ligands L7‒L16 only gave trace amount of the desired product 4, while more than 90% of the symmetric ketone was detected. These results demonstrated that the addition of these ligands is inapposite to suppress the competing oxidative carbonylation of arylzincs10,41. Remarkably, significant breakthroughs were made by the further evaluations of other tridentate pincer-ligands of type L17‒L23. Among them, 2,6-bis(N-pyrazolyl)pyridine ligand (bpp, L17), which has seen wide application in the nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions54,55 while rather rare application in cobalt catalysis, gave the optimal results for cobalt-catalyzed four-component carbonylation by overcoming a series of side pathways, such as oxidative carbonylation of arylzincs, sulfonylation of organozincs, alkene 1,2-arylsulfonylation, β-hydride elimination have been totally prohibited56,57. The desired unsymmetric ketone 4 was obtained in 75% yield under 23 °C within 2 h. Notably, switching from p-tolylzinc pivalate to other anion-supported p-tolylzinc reagents, which prepared by transmetalation reactions of p-tolylmagnesium chloride with ZnX2 (X = Cl, Br, I, OAc, OAd), resulted in significantly decreased yields of the product 4 (Fig. 2b). Generally, the arylzinc reagents prossessing more electron-rich carboxylate anions showed superior reactivity than the halide-supported organozincs. These unique paradigms of anion-effects stand as a treatment to tune the reactivity of organozinc reagents and extend their applications in coupling reactions58,59,60,61,62,63.

a, b Optimization studies. c Substrate scope investigation. Reaction conditions: radical electrophile (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv), alkene (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), (hetero)aryl‒ZnOPiv (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv), CoI2 (10 mol %), bpp (L17, 11 mol %), CO (1 atm), 1,4-dioxane, @ 23 °C, 2 h. [a] Ar‒ZnOPiv (3.0 equiv). Note: The yields of symmetric ketone are in parentheses.

With the optimized pincer-cobalt catalyst in hand, we next turned our attention to its versatility in the cobalt-catalyzed alkene carbonylative sulfonylation reaction. As shown in Fig. 2c, the substrate scope was largely insensitive to the electronic and steric changes on the para-, meta-, and ortho-substituted aryl alkenes (4‒20). Indeed, vinylarenes bearing acetal (14), lactam (15), heteroarene (16), as well as aryl halides (17‒20) posed no problems. Notably, no Negishi-type reactions were observed in the latter under the limits of detection. Likewise, the pincer-cobalt catalysis also showed excellent compatibility toward a large chemical space of both electron-rich and electron-poor arylzinc pivalates substituents at the para-, meta-, and ortho-positions (21‒36). It is noteworthy that a range of valuable functional groups, including silyl moiety (22), thiomethyl (23), trifluoromethyl (27), ester (28), nitrile (29), dioxole (31‒32), and halogens (25, 26, 33‒36) were well tolerated under the mild conditions. Moreover, arylzinc pivalate possessing a vinylarene-moiety was identified as viable nucleophile, smoothly underwent highly regioselective carbonylsulfonylation process across the double bond of 4-methylstyrene (2a). While the olefin motif derived from arylzinc pivalate side remained untouched, thus affording the ketone 37 as the sole product. Gratifyingly, the quinolone-, dibenzofuran-, and dibenzothiophene-based ketones (38‒40) were obtained in 51‒56% yields using the corresponding heteroarylzinc pivalates as the nucleophiles. Next, the current carbonylative sulfonylation reaction can be conducted with various sulfonyl chlorides. As shown, sulfonyl chlorides in particularly those bearing aryl halides (42‒44), alkyl halides (45), cyclopropyl (46), as well as the primary alkyl iodide (47) could be coupled in moderate to high yields. Again, our pincer-cobalt catalyst showed excellent chemoselectivity to differentiate SO2‒Cl from other reactive Csp2‒Cl, Csp2‒Br and Csp2‒I bonds, selectively occurring cascade alkene sulfonylcarbonylation.

Intrigued by the efficient catalytic activity of the pincer cobalt catalysis, we sought to unravel the reaction mode of action. To this end, the control experiments with stoichiometric amount of representative radical scavengers were performed (Fig. 3a). Among them, a significantly reduced yields of ketone 4 was observed when employing 1,1-diphenylethene as the additive, while the multicomponent reaction was completely suppressed in the presence of 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperinedinyloxy (TEMPO). A further radical-clock experiment with α-cyclopropyl styrene afforded both sulfonylcyclized product and ring-opened sulfonyl-carbonylated product (see SI, Fig. S10). These results strongly consistent with the EPR spin-trapping experiments using tosyl chloride (1a) or tert-butyl 2-iodoacetate (1j) as the radical precusors. Notably, regardless of the absence or presence of alkene, the same sulfonyl- or carbon-centered radical intermediates 48a (AN = 13.81 G, AH = 18.61 G) and 48b (AN = 14.21 G, AH = 20.21 G) were captured by 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-1-oxide (DMPO), thereby confirming the radical’s role in this pincer cobalt-catalyzed multicomponent carbonylative functionalization (Fig. 3b)59,64.

a, b Radical evidences. c, d Control experiments with pincer cobalt complex 49. e, f DFT calculations for the mechanistic studies. The computed energy profiles depict the most favorable spin states of the species, while the energies of the less favorable spin states are detailed in the Supporting Information (see Figs. S27 and S28).

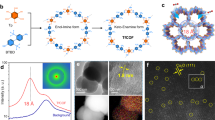

To better elucidate the structure and properities of the pincer-cobalt species relevant to the catalytic reactivity, a dark green crystal of bpp-ligated CoII-complex 49 was prepared from CoI2 and bpp with 1:1 ratio. A single-crystal X-ray diffraction study demonstrated that 49 adopts a triclinic geometry,(“The structure of 49 was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Deposition Number 2413440 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. This data is provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.”) which showed high catalytic reactivity in the alkene sulfonylcarbonylation reaction, leading to the desired product 4 in 72% yield. Notably, the 1.0 equiv of CoII(bpp) 49 initially reacted with phenylzinc pivalate (3b) under 1 atm of CO for 2 min, followed by transferring the resulting solution into a divided reaction mixture consisting of tosyl chloride 1a and alkene 2c under N2 atmosphere, delivering the desired unsymmetric ketone 21 in 63% yield (Fig. 3c). These findings demonstrated that the relatively more electron-rich property of bpp enables a mild reduction of CoII(bpp) by arylzincs to avoid the formation of Co0-species65, selectively leading to the formation of CoI(bpp) for multicomponent radical relay coupling reaction.

Moreover, in order to understand the mode of pincer-cobalt mediated 1,1-insertion of CO we subsequently devised a step-wise operation (Fig. 3d). A mixture of phenylzinc pivalate and different amounts of CoI2 and bpp under CO atmosphere at 23 °C for 2 min could in situ form the acyl-cobalt species 50, which was further confirmed by HR-MS analysis. Similarly, the solution was transferred into a divided reaction mixture consisting of tosyl chloride 1a and alkene 2c under N2 atmosphere, the ketone 21 (8% or 21%) was obtained in near 1:1 equiv ration to that of CoI2-bpp (10% or 25%), respectively. These findings demonstrated a rapid 1,1-insertion of CO to the formation of acyl-CoII species.

Thereafter, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted to disclose the kinetic model of this process in detail (Fig. 3e). In our calculations, the 1,1-insertion between the quartet pincer CoII-aryl complex 4I and CO could occur rapidly via transition state 2TS1 to furnish the acyl-CoII-species 4II. The calculated free energy barrier is 9.4 kcal/mol, revealing a favorable process as compared to the radical-type oxidation (20.5 kcal/mol) and radical-type substitution (14.9 kcal/mol) between 4I and benzylic radical (see SI, Fig. S26). This is the key to suppression of three-component competing reaction without the insertion of CO.

Subsequently, the reaction between the acyl-CoII complex 4II and the benzylic radical could proceed via either a radical-type oxidation or a radical-type substitution pathway. DFT calculations indicate that the radical-type oxidation involves a high-energy transition state 3TS3 (∆G‡ = 15.8 kcal/mol) to form the triplet intermediate 3IV. In contrast, the radical-type substitution of its connected acyl-moiety with the benzylic radical proceeds through the triplet transition state 3TS2 with a lower free energy barrier of 12.9 kcal/mol. These results suggested that the generation of a high valent CoIII-complex (like 3IV) and its subsequent reductive elimination pathway could be excluded as the mechanism for the final C − C bond formation (Fig. 3f).

Based on our mechanistic studies, a plausible catalytic cycle for this cobalt-catalyzed four-component carbonylative reaction is proposed in Fig. 4. Initially, due to the suitable stereoelectronic property of pincer ligand and relatively lower reducibility of OPiv-supported arylzincs57,59, the reduction of CoII(bpp) A by stioichimetric arylzinc pivalates uniquely dictates the formation of CoI(bpp) B, rather than Co0-complex, thereby inhibiting the generation of catalytically inert Co0(CO)n. Subsequently, CoI(bpp) B promotes the halogen atom transfer (HAT) with radical precursors (1) to afford the radical C and releases CoII(bpp) A. Transmetalation reaction between A and arylzinc pivalates furnishes the aryl-CoII(bpp) species D, which undergoes a fast 1,1-insertion with CO to generate the acyl-CoII(bpp) intermediate E. Alternatively, automatically radical addition of C into alkene (2) forms a benzyl radical F. A radical-type substitution between E and F affords the final product via the transition state G, and regenerates the CoII(bpp) complex B.

The in situ formed CoI(bpp) B is proposed as the catalytically active catalyst for the halogen atom transfer step to afford the CoII(bpp)-species A. Sequence transmetalation and CO insertion with A generate the key acyl-CoII(bpp) intermediate E, and a subsequent radical type substitution between E and F furnishes the product and regenerate intermediate B.

Encouraged by the high efficacy of pincer-cobalt catalysis in alkene carbonylsulfonylation reaction, we wondered whether it would be possible to directly replace CO with CO2 under tandem electro-thermo-catalysis, which includes CO2 electro-reduction to CO, coupled with cobalt-catalyzed alkene carbonylative functionalization (Fig. 5). Importantly, a commercial available silver powder was tested in a customized flow cell and exhibited satisfactory CO2-to-CO conversion at an average rate of 3.73 mmol h-1 for over 40 h, providing a product gas mixture of CO/H2 with >90/10 ratio. The gas can be collected for tandem reactions after a scrubbing process with concentrated NaOH to remove the unreacted CO2 carrier gas (see SI, Fig. S17)66,67,68. To our delight, the residual H2 had no influence for the cascade pincer-cobalt catalysis, thus giving the desired product 4 in 74% yield within equal efficacy to using CO gas. Likewise, other sulfonylcarbonylated compounds 51 − 53 were easily within reach under the tandem catalysis using CO2 as the initial C1 synthon. Hence, the upgrading of CO2 into valuable organic molecules should prove instrumental for potential applications of our tandem electro-thermo catalysis.

Reaction conditions: Sulfonyl chloride or alkyl halides (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv), Ar‒ZnOPiv (0.6 mmol, 3.0 equiv), alkene (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), CoI2 (10 mol %), bpp (L17, 12 mol %), CO:H2 ( > 90:10, 1 atm), 1,4-dioxane, @ 23 °C, 2 h. † Yields in parentheses are obtained under 1 atm of CO gas. [a] 2.0 mmol scale.

It is noteworthy that our tandem catalysis could be extended to achieve alkene carbonylative multicomponent functionalization with a variety of alkyl halides other than sulfonyl chlorides, thus allowing us to rapidly construct complex carbogenic skeletons via insequence C − C bonds formation. As shown, primary alkyl halides accommodating functionalities such as ester (47), trifluoromethyl (54 − 55), and sulfone (56 − 57) were proved to be viable substrates, furnishing the desired alkylcarbonylated products in 47 − 73% yields. Driven by the dramatic effects of organofluorinated compounds in medicinal chemistry69,70, we investigated the possibility of our protocol for direct access to versatile fluorinated ketones. A wide range of fluoroalkyl halides, such as those containing sulfone (58), phosphate (59), perfluoroalkyl (60, 64), phenoxy (61), alkyl bromide (62 − 63) and chloride (65) proved compatible coupling partners, thereby leading to the desired alkylfluorinated ketones in moderate to good yields. Indeed, the success with dibromodifluoromethane for alkene carbonylative fluoromethylation (62 − 63) inspired us whether our protocol could be extended to the regio- and chemoselective transformation with polyhalogenated electrophiles. Intriguingly, trichloromethyl derivatives can also be successfully engaged in this alkene carbonylative alkylation through selective mono Csp3 − Cl bond cleavage fortunately without compromising the catalytic efficiency, led to the alkylchlorinated ketones 66 − 70 in satisfied yields. Furthermore, extensions to those alkylbromides containing multiple reactive Csp3 − Br/Cl bonds were also examined under otherwise identical reaction conditions. Particularly interesting was the unique mono Csp3 − Br bond activation to afford the polyhalo-genated ketones 71 − 78 with complete control of regio-, and chemoselectivity. Notably, the excellent selectivity control of our tandem catalysis toward both Csp3 − X and Csp2 − X (X = Br, Cl), as well as wide functional group compatibility leave ample opportunities for increasing functional molecular complexity via late-stage diversifications.

To illustrate the synthetic utility of our tandem electro-thermo-catalysis to drug discoveries in medicinal chemistry, the advanced synthetic alkenes derived from drug-like molecules, such as canagliflozin (79), febuxostat (80), isoxepac (81), fenofibrate (82), salicin (83), atomoxetine (84), indomethacin (85), pyriproxyfen (86), probenecid (87), ibuprofen (88), were able to incorporate the sulfonyl and carbonyl fragments across the double bond in moderate to high yields with excellent functional group compatibility. As expected, the more challenging polyhalogenated Csp3-electrophiles were smoothly employed under the catalytic system to afford the polyhalogenated derivatives 89‒93 with complete control of regio-, and chemoselectivity. These results should prove the robustness and synthetic application of our protocol towards the construction of highly functionalized molecules in a streamline and diversified fashion, thereby providing a versatile tool for medicinal chemists in their drug-discovery setting (Fig. 6).

To showcase the synthetic utilizations of this cobalt-catalyzed multicomponent carbonylative functionalization reaction in creating high-value carbogenic skeletons, a series of derivatizations with the resulting functionalized ketones were conducted. Firstly, the halogenated ketones could be easily subjected to the intramolecular mono-dehalogenation process, giving the gem-dihalogenated cyclopropanes 94‒96 in excellent yields. In particular, the substrates 77 and 69 possessing multiple reactive Csp3 − X (X = Br or Cl) bonds, selectively underwent mono Csp3 − Cl bond cleavage to afford the halogenated cyclopropanes 97‒98 as the sole products with moderate to high diastereoselectivity (Fig. 7a–i). It is worth noting that various polyhalogenated alkanes, along with arylzinc pivalate under 1 atm of CO gas, are capable of the alkylative carbonylation of indene and delivering 99‒100 in good yields and diastereoselectivities. Follow-up monodehalogenation process provided an expedient route to the3,5-bicyclic ketones 101‒102 in 73‒76% yields (Fig. 7a-ii). Importantly, this multicomponent transformation can be easily scaled up to gram scale, yielding the product 32 with equal efficiency. The newly formed ketone functionality of 32 could be reduced in the presence of NaBH4 to afford alcohol 103 in excellent diastereoselectivity (dr >20:1). Moreover, facile desulfonylation process allowed for synthesis of α,β-unsaturated ketone 104, which could be further modified by copper-catalyzed silylation or Friedel-Crafts reaction to produce the products 105 and 106 (Fig. 7b), respectively.

a Access to halogenated cyclopropanes via monodehalogenation. b Scale up synthesis and diverse transformations. Reaction conditions: [a] Cs2CO3 (3.0 equiv), DMSO, @ 25 or 65 °C, 12 h. [b] NaBH4 (2.0 equiv), MeOH, @ 23 °C, 4 h. c Me2PhSi−ZnOPiv (1.2 equiv), CuI (10 mol %), THF, @ 23 °C, 4 h. d con. H2SO4, DCM-EtOH, @ 0 − 23 °C, 1 h.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that an industrial-friendly cobalt catalysis for the divergent carbonylative functionalization of alkenes under 1 atm of CO gas. Herein, the use of tridentate NNN-type pincer ligand is the key to tune the catalytic reactivity of cobalt for selectively dictating a full multi-component radical relay carbonylation reaction. Importantly, direct use CO2 as the C1 source in the multicomponent carbonylation reaction can be achieved under a tandem electro-thermo-catalysis, thus allowing us to rapidly and reliably construct unsymmetric ketones with ample substrate scope of alkenes, organozinc reagents, as well as sulfonyl and alkyl radical precursors, particularly in a regio- and chemoselective fashion. Moreover, the synthetic utility of this approach was well illustrated by the late-stage modifications of bioactive molecules and the facile transformations of the resulting ketones.

Methods

General procedure for cobalt-catalyzed alkene carbonylation under 1 atm of CO

An oven-dried tube was charged with CoI2 (10 mol %), L17 (12 mol %), sulfuryl chloride 1 (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv). Then the tube was evacuated and backfilled with CO (three times, 1 atm, balloon). Anhydrous 1,4-dioxane (1.0 mL) was added and stirred for 10 minutes vigorously. Alkene 2 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added. Then arylzinc pivalates 3 (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv) resolved in 1,4-dioxane (0.5 mL) was added dropwise over 5 minutes. The reaction mixture was stirred at 23 °C for 2 h. When the reaction was completed, the resulting residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (petroleum ether/EtOAc) to yield products.

General procedure for cobalt-catalyzed alkene carbonylation Using CO2 as the C1 source

An oven-dried tube was charged with CoI2 (10 mol %), L17 (12 mol %). Then the tube was evacuated and backfilled with the gas mixture of CO:H2 ( > 90:10 ratio, three times, 1 atm, balloon). Anhydrous 1,4-dioxane (1.0 mL) was added and stirred for 10 minutes vigorously. Radical source 1 (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv) and alkene 2 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv) were addded. Then arylzinc pivalates 3 (0.6 mmol, 3.0 equiv) resolved in 1,4-dioxane (0.5 mL) was added dropwise over 5 minutes. The reaction mixture was stirred at 23 °C for 2 h. When the reaction was completed, the resulting residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (petroleum ether/EtOAc) to yield products.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization are available within the article and the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this pape. The X-ray crystallographic data for structure 49 used in this study are available in the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC 2413440) and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service (www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures). All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Beller, M. Catalytic Carbonylation Reactions, 1-272, (Springer, 2006).

Modern Carbonylation Methods (Ed.: László, K.), Wiley, Hoboken, (2008).

Cai, B., Cheo, H. W. & Wu, J. Light-promoted organic transformations utilizing carbon-based gas molecules as feedstocks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18950–18980 (2021).

Carbon Monoxide in Organic Synthesis-Carbonylation Chemistry (Ed.: Gabriele, B.), (Wiley-VCH 2021).

The Chemical Transformations of C1 Compounds (Eds.: Wu, X.-F., Han, B., Ding, K., Liu, Z.), (Wiley-VCH, 2022).

Brennführer, A., Neumann, H. & Beller, M. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylation reactions of aryl halides and related compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 4114–4133 (2009).

Wu, X.-F., Neumann, H. & Beller, M. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylative coupling reactions between Ar–X and carbon nucleophiles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 4986–5009 (2011).

Sumino, S., Fusano, A., Fukuyama, T. & Ryu, I. Carbonylation reactions of alkyl iodides through the interplay of carbon radicals and Pd catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1563–1574 (2014).

Wu, X.-F. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylative transformation of aryl chlorides and aryl tosylates. RSC Adv. 6, 83831–83837 (2016).

Peng, J.-B., Wu, F.-P. & Wu, X.-F. First-row transition-metal-catalyzed carbonylative transformations of carbon electrophiles. Chem. Rev. 119, 2090–2127 (2019).

Li, Y., Hu, Y. & Wu, X.-F. Non-noble metal-catalysed carbonylative transformations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 172–194 (2018).

Xu, J.-X., Wang, L.-C. & Wu, X.-F. Non-noble metal-catalyzed carbonylative multi-component reactions. Chem. Asian J. 17, e202200928 (2022).

Ai, H.-J. et al. Iron-catalyzed alkoxycarbonylation of alkyl bromides via a two-electron transfer process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211939 (2022).

Wang, C., Wu, X., Li, H., Qu, J. & Chen, Y. Carbonylative cross-coupling reaction of allylic alcohols and organoalanes with 1 atm CO enabled by nickel catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210484 (2022).

Wang, L.-C., Chen, B., Zhang, Y. & Wu, X.-F. Nickel-catalyzed four-component carbonylation of ethers and olefins: direct access to γ-oxy esters and amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202207970 (2022).

Weng, Y. et al. Nickel-catalysed regio- and stereoselective acylzincation of unsaturated hydrocarbons with organozincs and CO. Nat. Synth. 2, 261–274 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Nickel-catalyzed carbonylative Negishi cross-coupling of unactivated secondary alkyl electrophiles with 1 atm CO Gas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7921–7978 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Teng, B.-H. & Wu, X.-F. Copper-catalyzed trichloromethylative carbonylation of ethylene. Chem. Sci. 15, 1418–1423 (2024).

Gosmini, C., Begouin, J.-M., Moncomble, A. Cobalt-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Commun. 28, 3221–3233 (2008).

Cahiez, G. & Moyeux, A. Cobalt-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 110, 1435–1462 (2010).

Lutter, F. H. et al. Cobalt-catalyzed cross-couplings and electrophilic aminations using organozinc pivalates. ChemCatChem 11, 5188–5197 (2019).

Guérinot, A. & Cossy, J. Cobalt-catalyzed cross-couplings between alkyl halides and Grignard reagents. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1351–1363 (2020).

Hebrard, F. & Kalck, P. Cobalt-catalyzed hydroformylation of alkenes: generation and recycling of the carbonyl species, and catalytic cycle. Chem. Rev. 109, 4272–4282 (2009).

Zhang, B., Kubis, C. & Franke, R. Hydroformylation catalyzed by unmodified cobalt carbonyl under mild conditions. Science 377, 1223–1227 (2022).

Khand, I. U., Knox, G. R., Pauson, P. L., Watts, W. E. A cobalt induced cleavage reaction and a new series of arenecobalt carbonyl complexes. J. Chem. Soc. D 36a (1971).

Faculak, M. S., Veatch, A. M. & Alexanian, E. J. Cobalt-catalyzed synthesis of amides from alkenes and amines promoted by light. Science 383, 77–81 (2024).

Wang, Y., Wang, P., Neumann, H. & Beller, M. Cobalt-catalyzed multicomponent carbonylation of olefins: efficient synthesis of β-Perfluoroalkyl Imides, Amides, and Esters. ACS Catal. 13, 6744–6753 (2023).

Wang, L.-C., Yuan, Y., Zhang, Y. & Wu, X.-F. Cobalt-catalyzed aminoalkylative carbonylation of alkenes toward direct synthesis of γ-amino acid derivatives and peptides. Nat. Commun. 14, 7439–7448 (2023).

Sargent, B. T. & Alexanian, E. J. Cobalt-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of alkyl tosylates: stereospecific synthesis of amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9533–9536 (2019).

Veatch, A. M. & Alexanian, E. J. Cobalt-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of (hetero)aryl halides promoted by visible light. Chem. Sci. 11, 7210–7213 (2020).

Veatch, A. M., Liu, S. & Alexanian, E. J. Cobalt-catalyzed deaminative amino- and alkoxycarbonylation of aryl trialkylammonium salts promoted by visible light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202210772 (2022).

Liu, Y., Chen, Y.-H., Yi, H. & Lei, A. An update on oxidative C–H carbonylation with CO. ACS Catal. 12, 7470–7485 (2022).

Grigorjeva, L. & Daugulis, O. Cobalt-catalyzed direct carbonylation of aminoquinoline benzamides. Org. Lett. 16, 4688–4690 (2014).

Williamson, P., Galvan, A. & Gaunt, M. J. Cobalt-catalysed C–H carbonylative cyclisation of aliphatic amides. Chem. Sci. 8, 2588–2591 (2017).

Zeng, L. et al. Cobalt-catalyzed intramolecular oxidative C(sp3)–H/N–H carbonylation of aliphatic amides. Org. Lett. 19, 2170–2173 (2017).

Zeng, L. et al. Cobalt-catalyzed electrochemical oxidative C–H/N–H carbonylation with hydrogen evolution. ACS Catal. 8, 5448–5453 (2018).

Sau, S. C., Mei, R., Struwe, J. & Ackermann, L. Cobaltaelectro-catalyzed C–H activation with carbon monoxide or isocyanides. ChemSusChem 12, 3023–3027 (2019).

Wang, L.-C., Chen, B. & Wu, X.-F. Cobalt-catalyzed direct aminocarbonylation of ethers: efficient access to α-amide substituted ether derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202203797 (2022).

Lu, L., Qiu, F., Alhumade, H., Zhang, H. & Lei, A. Tuning the oxidative mono- or double-carbonylation of alkanes with CO by choosing a Co or Cu catalyst. ACS Catal. 12, 9664–9669 (2022).

Teng, M.-Y. et al. Cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective C–H carbonylation towards chiral isoindolinones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318803 (2024).

Devasagayaraj, A. & Knochel, P. Preparation of polyfunctional ketones by a cobalt(II) mediated carbonylation of organozinc reagents. Tetrahedron Lett. 36, 8411–8414 (1995).

Shen, C. & Wu, X.-F. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylative multi-component reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 2973–2987 (2017).

Zhang, S., Neumann, H. & Beller, M. Synthesis of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds by carbonylation reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 3187–3210 (2020).

Cheng, L.-J. & Mankad, N. P. Copper-catalyzed carbonylative coupling of alkyl halides. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 2261–2274 (2021).

Yang, H., Yang, S., Wu, X.-F. & Chen, F. Light-induced perfluoroalkylative carbonylation of unactivated alkenes with a recyclable photocatalyst. Green. Synth. Catal. 6, 81–85 (2025).

Wang, Q., Zheng, L., He, Y.-T. & Liang, Y.-M. Regioselective synthesis of difluoroalkyl/perfluoroalkyl enones via Pd-catalyzed four-component carbonylative coupling reactions. Chem. Commun. 53, 2814–2817 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Geng, H.-Q. & Wu, X.-F. Palladium-catalyzed perfluoroalkylative carbonylation of unactivated alkenes: access to β-perfluoroalkyl esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 24292–24298 (2021).

Gatlik, B. & Chaładaj, W. Pd-catalyzed perfluoroalkylative aryloxycarbonylation of alkynes with formates as CO surrogates. ACS Catal. 11, 6547–6559 (2021).

Song, Y., Wei, G., Quan, Z., Chen, Z. & Wu, X.-F. Palladium-catalyzed four-component difluoroalkylative carbonylation of aryl olefins and ethylene. J. Catal. 413, 163–167 (2022).

Kuai, C.-S., Teng, B.-H. & Wu, X.-F. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylative multicomponent fluoroalkylation of 1,3-enynes: concise construction of diverse cyclic compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318257 (2024).

Zhou, M., Zhao, H.-Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, X. Nickel-catalyzed four-component carbocarbonylation of alkenes under 1 atm of CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 18191–18199 (2020).

Rao, N., Li, Y.-Z., Luo, Y.-C., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, X. Nickel-catalyzed multicomponent carbodifluoroalkylation of electron-deficient alkenes. ACS Catal. 13, 4111–4119 (2023).

Ertl, P., Altmann, E. & McKenna, J. M. The most common functional groups in bioactive molecules and how their popularity has evolved over time. J. Med. Chem. 63, 8408–8418 (2020).

Arendt, K. M. & Doyle, A. G. Dialkyl ether formation by nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of acetals and aryl iodides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9876–9880 (2015).

Andersen, T. L., Donslund, A. S., Neumann, K. T. & Skrydstrup, T. Carbonylative coupling of alkyl zinc reagents with benzyl bromides catalyzed by a nickel/NN2 pincer ligand complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 800–804 (2018).

Engl, S. & Reiser, O. Copper-photocatalyzed ATRA reactions: concepts, applications, and opportunities. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 5287–5299 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Anion-tuning of organozincs steering cobalt-catalyzed radical relay couplings. ACS Catal. 13, 9254–9263 (2023).

Hernán-Gómez, A. et al. Organozinc pivalate reagents: segregation, solubility, stabilization, and structural insights. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2706–2710 (2014).

Cheng, X. et al. Organozinc pivalates for cobalt-catalyzed difluoroalkylarylation of alkenes. Nat. Commun. 12, 4366 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Salt-stabilized silylzinc pivalates for nickel-catalyzed carbosilylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202379 (2022).

Lin, J. et al. Salt-stabilized alkylzinc pivalates: versatile reagents for cobalt-catalyzed selective 1,2-dialkylation. Chem. Sci. 14, 8672–8680 (2023).

Hu, Y. et al. Stereoselective C–O silylation and stannylation of alkenyl acetates. Nat. Commun. 14, 1454 (2023).

Luo, D. et al. Bench-stable carbamoylzinc pivalates for modular access to amides, ureas, and thiocarbamates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 32238–32248 (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Synthetic exploration of sulfinyl radicals using sulfinyl sulfones. Nat. Commun. 12, 5244 (2021).

Luo, X. et al. Valve turning towards oncycle in cobalt-catalyzed Negishi-type cross-coupling. Nat. Commun. 14, 4638 (2023).

Song, et al. recent advances in carbonylation of C–H bonds with CO2. Chem. Commun. 56, 8355–8367 (2020).

Ma, M., Trzesniewski, B. J., Xie, J. & Smith, W. A. Selective and efficient reduction of carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide on oxide-derived nanostructured silver electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 9748–9752 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Synchronous recognition of amines in oxidative carbonylation toward unsymmetrical ureas. Science 386, 776–782 (2024).

Muller, K., Faeh, C. & Diederich, F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science 317, 1881–1886 (2007).

Feng, Z., Xiao, Y.-L. & Zhang, X. Transition-metal (Cu, Pd, Ni)-catalyzed difluoroalkylation via cross-coupling with difluoroalkyl halides. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2264–2278 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22322108 to J.L.), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20231521 and BK20221355 to J.L.) and Science and Technology Program of Suzhou (ZXL2024399 to J.L.) for financial supports. We also thank Hefei Advanced Computing Center for computational support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. conceived and directed the project and wrote the manuscript by all the other authors; S.G., Z.C., and L.P. developed and performed the catalytic methods and the synthetic applications. S.G., K.C., Z.C., and S.D. performed the mechanistic studies; Y.H. and L.H. designed the CO2-to-CO conversion methods; G.L. designed and directed the DFT calculations; X.W. performed the DFT calculations; S.G. and Z.C. prepared the starting materials, C.N. analyzed the crystal structures, all the authors were involved in interpretation of the results presented in the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ge, S., Cui, Z., Peng, L. et al. Pincer-cobalt boosts divergent alkene carbonylation under tandem electro-thermo-catalysis. Nat Commun 16, 8803 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63875-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63875-4