Abstract

Dysregulation of MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor (MYC) represents a common yet mechanistically unresolved driver of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). While MYC remains an elusive therapeutic target, developing strategies to promote its degradation emerges as a promising alternative approach. Here we show that vaccinia-related kinase 2 (VRK2) functions as a direct MYC-interacting kinase that stabilizes the oncoprotein through phosphorylation at Serine (Ser)281/293. This phosphorylation enables VRK2 to compete with the Skp1-Cullin-F-box protein complex containing FBXO24 (SCF-FBXO24) E3 ligase, thereby blocking MYC polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. The stabilized MYC-VRK2 complex amplifies transcriptional activation of protumorigenic programs, including the immune checkpoint programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and VRK2 itself, establishing a self-reinforcing oncogenic circuit. Therapeutic inhibition of VRK2 in HCC models reduces MYC protein levels, suppresses tumor progression, and synergizes with anti- programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) immunotherapy. Our results reveal VRK2-mediated stabilization of MYC as a critical nexus linking hepatocarcinogenesis to immune evasion, proposing VRK2 kinase inhibition as a mechanism-based therapeutic strategy for MYC-driven HCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks as the fourth most common cancer and second leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally1,2,3. Clinically, HCC is often diagnosed at advanced stages, leaving patients with few treatment options. Recently, the application of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), using monoclonal antibodies that target programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), has become a promising therapeutic approach for HCC4. Nevertheless, the distinctive hepatic environment significantly diminishes HCC’s responsiveness to ICB therapy5. Despite the widespread use of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatments, their efficacy is limited due to frequent resistance, resulting in overall benefit rates of only 15–20% among HCC patients. Combination therapies are a promising strategy to overcome resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 and to increase response rates6,7,8. However, clinical trials combining anti-PD-1/PD-L1 with other antitumor drugs, without a strong mechanistic rationale, have not shown synergistic effects9,10. Therefore, there is an urgent need for innovative combination therapies that not only include anti-PD-1/PD-L1 ICB but also incorporate markers for predicting efficacy.

MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor (MYC), also called c-Myc, is a nucleus-located transcription factor belonging to the essential helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper family. It governs cell growth, death, differentiation, and metabolism11. MYC governs numerous target genes by recognizing E-box sequences (5’-CACGTG-3’) in the genome. This regulatory mechanism contributes to controlling the hallmark pathological functions of tumors12. In mouse, the MYC gene often undergoes mutations and overexpression, particularly in various types of cancer, including liver cancer13,14. Simultaneously, post-translational modifications of MYC proteins play a pivotal role in tumorigenesis15. However, attempts to directly disrupt MYC function have met with limited success, partly due to its “undruggable” protein structure16. The expression of MYC is intricately regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system17. Therefore, the direct targeting of protein-interacting factors is crucial for regulating MYC’s function. The degradation process involves the continuous phosphorylation of two pivotal residues, serine 62 (S62) and threonine 58 (T58). Phosphorylation of S62 leads to MYC stability18. In contrast, phosphorylation of MYC at T58 by GSK3β initiates recognition by the E3 ubiquitin ligase FBXW7 and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome19,20. Dysregulation of signaling proteins associated with MYC phosphorylation is common in tumor cells21,22. Thus, dysfunction of the MYC degradation pathway is a crucial mechanism for the carcinogenic activation of MYC in human cancers and a critical focus for therapeutic intervention.

Vaccine-associated kinase 2 (VRK2), identified as a putative serine/threonine kinase, has been shown to play a significant role in apoptosis, cell growth, and immune response. Furthermore, reports indicate substantial overexpression of VRK2 in various cancers, underscoring its involvement in a range of biological functions23,24,25. For instance, VRK2 promotes breast cancer invasion by phosphorylating NFAT124. Additionally, VRK2 phosphorylates PLK1 in pancreatic cancer, which disrupts the Chfr-PLK1 interaction and inhibits PLK1 ubiquitination26. Moreover, VRK2 can phosphorylate multiple transcription factors, thereby altering gene transcription. Additionally, it can also exert its effects independently of its kinase activity27,28. In HCC, VRK2 promotes phosphorylation of Bcl-2, which enhances the dissociation of Bcl-2 from Beclin-1 and promotes the formation of the Beclin-1-Atg14-Vps34 complex, which promotes autophagy. In addition, phosphorylation of Bcl-2 in turn promotes the interaction of Bcl-2 with BAX, thereby inhibiting apoptosis. This two-sided effect leads to reduced sensitivity to sorafenib in HCC29. The findings from these studies contribute to elucidating the role of VRK2 in pathological conditions, particularly in cancer. Despite extensive research, the mechanisms underlying the upregulation of VRK2 expression in HCC remain unclear, specifically how the augmented VRK2 levels contribute to the cellular reprogramming that promotes cancer progression.

Here we show that VRK2 stabilizes MYC by phosphorylating Ser281/293, blocking Skp1-Cullin-F-box protein complex containing FBXO24 (SCF-FBXO24) -mediated K323 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This MYC-VRK2 axis activates PD-L1 transcription and establishes an immunosuppressive niche. Targeting VRK2 with the selective inhibitor AZD7762 destabilizes MYC, enhances cytotoxic T cell infiltration, and synergizes with anti-PD-1 therapy in HCC models. Our findings position VRK2 as both a predictive biomarker and therapeutic target for overcoming ICB resistance in MYC-driven HCC.

Results

Identification of VRK2 as a MYC binding partner and an oncogene associated with poor prognosis in patients with HCC

Due to the challenge of directly targeting the MYC oncoprotein in cancer therapy, we aimed to identify key interactors that could be targeted. We began by conducting a mass spectrometry analysis to identify potential binding proteins of MYC in the HCC cell line MHCC97H, which stably expresses Flag-tagged MYC. The proteins were resolved by Western blot and visualized using silver staining (Fig. 1a). Next, we selected protein kinases from the TCGA database that have a prognostic marker effect on HCC for further screening (Fig. 1b). Ultimately, we identified VRK2, a putative serine/threonine kinase (Fig. 1c). We then performed exogenous and endogenous co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays to confirm the interaction between VRK2 and MYC (Fig. 1d and Fig. s1a, b). We further performed GST-Pulldown to determine at the in vitro level that wild-type VRK2 (VRK2 WT) can directly bind to MYC, while the mutant VRK2 K168E (VRK2 MUT) cannot (Fig. s1c). Immunofluorescence also confirmed the co-localization of VRK2 with MYC in the nucleus (Fig. 1e and Fig. s1d). To investigate the specific region that VRK2 interacts with MYC, we conducted deletion mutations in the functional domain of MYC, followed by co-IP. We observed a significant reduction of the interaction between VRK2 and MYC when the functional domain of MBII, which is crucial for MYC’s transcriptional activity, was deleted (Fig. s1e). Additionally, we conducted truncated co-IP assays and observed that VRK2 did not interact with the C-terminus of MYC, and similarly, MYC did not interact with the C-terminus of VRK2 (Fig. s1f, g). Next, we noticed that VRK2 expression was higher in cancerous tissues (Tumor, T) than in adjacent non-cancerous liver tissues (Paracancerous, P) in both the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)—liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) and Liver Cancer Research Institute of RIKEN (LIRI-JP) datasets (Fig. s2a). We then confirmed this pattern of VRK2 expression across 21 online datasets associated with HCC. In three paired datasets and 18 unpaired tumor and non-tumor datasets, VRK2 expression was consistently higher in HCC compared to paracancerous liver tissues (Fig. s2b, c). Further subgroup analysis within various HCC datasets, stratified by liver disease profiles, revealed VRK2 expression was also higher in HCC patients with tumor node metastasis classification (TNM) stages 2–4 than in stage 1 patients (Fig. 1f, g). Additionally, we observed a significant increase in VRK2 expression specifically in the cancerous tissues of HCC patients, as opposed to liver tissues from healthy individuals. In our subgroup analysis of the TCGA-LIHC cohort individuals with poorly differentiated HCC (Edmondson G3-4) exhibited higher VRK2 expression in cancer tissues than patients with highly- to moderately-differentiated HCC (Edmondson G1-2). Moreover, compared to patients without vascular invasion (VI-), patients with vascular invasion (VI+) had higher levels of VRK2 expression in their cancer tissues (Fig. 1h). While VRK2 expression remained unchanged in benign liver diseases, including chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and paraneoplastic tissues, we discovered that VRK2 was upregulated in liver tissues with high-grade dysplasia (HGDN), indicating that higher VRK2 expression could be an early indicator of HCC formation (Fig. s2d). The aforementioned findings indicate a possible link between VRK2 expression and key processes such as proliferation, metastasis, and dedifferentiation during the development of HCC.

a Sliver-stained SDS-PAGE gel of the Co-IP products (n = 3 independent experiments). b Pearson’s correlation analysis of p-values of kinases in mass spectrometry and prognostic scores of kinases in TCGA. c The peptide fragment of VRK2 as determined by mass spectrometry. d Immunoprecipitation assay of interaction between endogenous MYC and VRK2 in MHCC97H cells were harvested for western blotting with the indicated antibodies (n = 3 independent experiments). e The co-localization analysis for MYC and VRK2 in MHCC97H cells. Scale bar: 20 μm. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (n = 3 independent experiments). f, g The mRNA level of VRK2 in LIHC tumor stage and normal tissues in a TCGA-LIHC (RNA-seq data) (f) and LIRI-JP dataset (RNA-seq data) (g). h The mRNA level of VRK2 in LIHC was grouped according to pathological differentiation, vascular invasion in a TCGA-LIHC (RNA-seq data). i Representative IHC images of VRK2 staining of clinical HCC and paracancerous tissues (n = 123). Scale bar: 100 μm (left)/25 μm (right) (n = 3 independent experiments). j VRK2 differentially expressed in HCC and paracancerous tissues from cohort 2 (n = 120) for western blotting with the indicated antibodies, and Relative VRK2 protein level in HCC tissues (T) by comparing to their counterpart paracancerous tissues (P) after normalizing to GAPDH expression (n = 3 independent experiments). k Overall survival according to VRK2 mRNA levels expression in the TCGA-LIHC cohort, LIRI-JP cohort and Tongji cohort 1. l Progression-free survival according to VRK2 mRNA levels expression in the TCGA-LIHC cohort, LIRI-JP cohort and Tongji cohort 1. m Heatmap (left) of clinicopathologic characteristics of TCGA-LIHC HCC patients grouped by VRK2 expression (left panel). Forest plot (right panel) of the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards model for overall survival. For Western blot experiments, GAPDH was used as a loading control (j). f–h P values were calculated using a student’s unpaired t-test (two-tailed). Data were presented as the mean ± SD. i, j P values were calculated using a student’s paired t-test (two-tailed). k, l P values were calculated using a Kaplan–Meier test (two-tailed). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We elevated VRK2 expression in an HCC patient cohort (Supplementary Table 1) from our center (Ethical Approval No. TJ-IRB20210935) using real-time PCR (RT-PCR) (Fig. s2e), immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1i), and western blot (WB) (Fig. 1j) to validate the bioinformatics analysis from online datasets. We observed that VRK2 expression was generally higher in tumor tissues compared to paracancerous liver tissues. Furthermore, we investigated the correlation between VRK2 expression and the prognosis of HCC patients. Patients with high VRK2 expression exhibited poorer prognosis, both overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), as demonstrated by survival analyses in the TCGA-LIHC and LIRI-JP cohorts and our HCC patient cohort (Fig. 1k, l). A multi-factorial Cox regression analysis showed that high VRK2 expression was an independent risk factor for poorer overall survival in HCC patients (corrected HR (95% CI): 1.567 (1.045–2.330), P = 0.026) (Fig. 1m). In summary, these results provide compelling evidence that VRK2 is a genuine MYC interaction partner and a critical gene in HCC, closely associated with poor patient prognosis.

VRK2 promotes HCC tumorigenesis and progression

Since VRK2 physically binds with oncoprotein MYC and is frequently upregulated in human HCC, we were prompted to investigate its functional role. We elevated both mRNA and protein expression levels of VRK2 in HCC cell lines (Fig. s3a, b and Supplementary Table 3). Based on the results of RT-PCR and WB for VRK2 expression across various HCC cell lines, we initially established Hep3B and HLF cell lines with stable VRK2 expression through lentiviral infections. Concurrently, we utilized the CRISPR/Cas9 system to generate VRK2 knockouts in MHCC97H and HepG2 cells. The process for constructing these knockout cells is detailed below (Fig. s3c). We also performed VRK2 knockout, as well as VRK2 WT and VRK2 MUT rescue assays in the knockout cells, to set the stage for further exploration of VRK2’s role (Fig. s3d–k).

In vitro assays, including the CCK-8 assay, cloning formation assay, and EdU assay, were conducted on HCC cell lines with either overexpression or knockout of VRK2. The results showed that overexpression of VRK2 in Hep3B and HLF cells significantly increased their proliferative ability (Fig. s4a, b, e, h, k, n), while VRK2 knockout in MHCC97H and HepG2 cells substantially reduced their proliferation. Notably, this reduction was only reversed by the overexpression of VRK2 WT, not the MUT variant (Fig. s4c, d, f, g, i, j, l, m, o, p). Additionally, a cell cycle assay revealed that overexpression of VRK2 in Hep3B and HLF cells significantly promoted the G1-S phase transition (Fig. s5a–c). Conversely, knockout of VRK2 in MHCC97H and HepG2 cells led to a notable arrest at the G1-S phase of the cell cycle, which was specifically alleviated by VRK2 WT overexpression (Fig. s5d–f). The above results suggest that VRK2 WT, but not the MUT variant, can stimulate the proliferative capacity of HCC cells in vitro.

Next, confirmed the oncogenic potential of VRK2 in vivo using subcutaneous tumor models (Fig. 2a, b) and liver implantation models (Fig. 2c–e). Subcutaneous tumor model showed that overexpression of VRK2 WT significantly increased the tumor volume and weight, whereas VRK2 MUT caused this effect less markedly than VRK2 WT. Liver implantation model showed that overexpression of VRK2 significantly increased the tumor volume. In contrast, VRK2 knockdown resulted in the opposite effect. Importantly, the suppressive effect of VRK2 knockdown was selectively reversed by the overexpression of VRK2 WT, not the MUT variant. To further elucidate the role of VRK2 amplification in the formation and development of HCC, we developed an oncogene-driven HCC model in C57BL/6 J mice using two plasmid combinations: Myc+sgTp53. We then injected hydrodynamically grouped VRK2 WT, VRK2 MUT, and vector control plasmids (Fig. 2f). After 4 weeks of the models reaching the tumorigenic, it was observed that overexpression of VRK2 WT significantly induced the formation of liver tumors (Fig. 2g), increased liver/body weight ratio and fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2h). In contrast, the control and VRK2 MUT groups showed only mild liver injury. In addition, we also counted the overall survival of the model, and found that the survival of the mice injected with VRK2 WT was significantly shorter than that of the other two groups (Fig. 2i). Additionally, we investigated the loss-of-function effect of VRK2 on HCC development using a hepatocyte-specific conditional knockout mouse. Tumorigensis was induced by DEN/CCl4 induction (Fig. 2j). MRI and H&E staining revealed that vrk2 f/f+alb-cre mice had significantly reduced tumor proliferation and smaller tumor sizes, liver/body weight ratio, and tumor volume compared to control vrk2 f/f mice (Fig. 2k, l), and found that the survival of vrk2 f/f mice was significantly shorter than that of the other one groups (Fig. 2m). These results indicated that VRK2 promotes the tumorigenesis and progression of HCC.

a Xenograft tumors from Hep3B cells (vector/VRK2-WT/VRK2-MUT) via subcutaneous injection in mice (n = 5 mice in each group). Scale bar: 1 cm. b Xenograft tumors from MHCC97H cells (sgCON/sgVRK2/sgVRK2 + VRK2 WT/sgVRK2 + VRK2 MUT) via subcutaneous injection in mice (n = 5 mice in each group). Scale bar: 1 cm. Tumor volume growth curves (middle), and tumor weight (bottom) were also quantified and compared. c Liver orthotopic models (n = 5 mice in each group) with Hep3B cells (vector/VRK2-WT/VRK2-MUT) and MHCC97H cells (sgCON/sgVRK2/sgVRK2±WT/MUT). Showing bioluminescence, gross liver/tumor images, and H&E-stained sections. Gross image Scale bar: 1 cm, H&E image Scale bar: 200 μm (left)/50 μm (right). d Bioluminescence intensity statistics of a nude mouse liver orthotopic transplantation model (n = 5 mice in each group). e Tumor volume of liver orthotopic transplantation models (n = 5 mice in each group). f Schematic diagram of different combinations (NC/VRK2 WT/VRK2 MUT) of oncogenic plasmids with luciferase injected into mice. g HTVi models (n = 7 mice in each group) showing bioluminescence imaging, gross liver/tumor images, and H&E-stained liver sections. Gross image Scale bar: 1 cm, H&E image Scale bar: 200 μm (up)/50 μm (bottom). h Liver/body weight ratio in the HTVi model (up). Bioluminescence intensity statistics of HTVi models (bottom) (n = 7 mice in each group). i Survival statistics of HTVi models. j Schematic representation of the DEN/CCL4 HCC development model induced in VRK2 liver-specific knockout C57BL/6 J mice. k DEN/CCl4-induced HCC models (n = 7 mice in each group) showing MRI, gross liver/tumor images, and H&E-stained liver sections. Gross image Scale bar: 1 cm, H&E image Scale bar: 200 μm (up)/50 μm (bottom). l Liver/body weight ratio in the DEN/CCL4 model (up). Tumor volume of DEN/CCL4 models (bottom) (n = 7 mice in each group). m Survival statistics of DEN/CCL4 models (n = 7 mice in each group). a, b, d, e, h, l P values were calculated using a student’s unpaired t-test (two-tailed). Data were presented as the mean ± SD. i, m P values were calculated using a Kaplan–Meier test (two-tailed). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

VRK2 enhances MYC transcriptional activity by directly mediating phosphorylation of MYC at S281 and S293

To delve deeper into the mechanisms behind VRK2’s role in promoting HCC progression, we conducted RNA sequencing assays followed by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). The results showed that the group with high VRK2 expression had a higher enrichment in relevant signaling pathways of transcription factors, including MYC, E2F, and other pathways (Fig. 3a, b). This finding aligns with our mass spectrometry data (Fig. 1a). Additionally, we performed a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay using HCC cell lines with either overexpressed or knocked-out VRK2. The results indicated a significant increase in the E-BOX activity o with VRK2 overexpression and a decrease with VRK2 knockout (Fig. 3c, d and Fig. s6a, b). We also examined the impact of VRK2 on cell cycle-related proteins by WB, and the results showed that the overexpression of VRK2 led to a notable increase in the expression of these proteins and a shortening of the cell cycle. (Fig. 3e and Fig. s6c). Considering VRK2’s role as a kinase and its interaction with MYC, sought to determine if VRK2 could induce MYC phosphorylation. We employed phosphoaffinity immunoblotting and treated samples with CIAP, a calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase used to attenuate the degree of phosphorylation of MYC. We observed that MYC phosphorylation decreased with increased CIAP treatment duration (Fig. 3f), suggesting that MYC undergoes phosphorylation. To identify VRK2-induced phosphorylation sites on MYC, we utilized mass spectrometry. We identified four sites: T58, S62, S281, and S293, with T58 and S62 being well-known MYC phosphorylation sites (Fig. 3h), located at the N-terminus of the MYC protein. Although the functions of these sites have been extensively studied, the S281 and S293 sites, located at the C-terminus, have not been as extensively reported. These sites are highly conserved across species (Fig. 3g) and thus garnered our interest. Molecular docking results confirmed that VRK2 induces phosphorylation modifications (Fig. 3i). We then inactivated and mutated the identified phosphorylation sites—T58, S62, S281, and S293—and performed co-IP. The results indicated that the mutations S281A and S293A did not affect VRK2-induced pan-phosphorylation of MYC, regardless of VRK2’s presence (Fig. 3j). This suggests that VRK2 can indeed phosphorylate these sites, which was further validated by in vitro kinase assays (Fig. 3k). After identifying these two phosphorylation sites for modification, we developed custom phosphorylation-specific antibodies to detect them. We conducted antibody specificity assays and confirmed the antibodies’ effectiveness in MHCC97H cells. The results demonstrated that the custom antibodies specifically recognized phosphorylated MYC at the S281 and S293 sites (Fig. s6d). Furthermore, the reduction of the phosphorylation levels of these two sites was detectable after VRK2 expression was inhibited using small interfering RNA (siRNA) in MHCC97H cells (Fig. 3l). These findings indicate that VRK2 enhances MYC transcriptional activity by directly mediating MYC phosphorylation at S281 and S293.

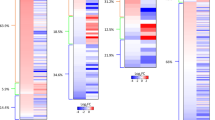

a sgCON or sgVRK2 MHCC97H cells were harvested for RNA-seq analysis and pathway analysis. Differentially regulated genes with more than twofold change were included in this pathway analysis (n = 3 independent experiments). b VRK2-related gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). c, d E-box activity changes in Hep3B, HLF, MHCC97H, and HepG2 cells after VRK2 overexpression or knockout (n = 3 independent experiments). e HLF and MHCC97H cells after VRK2 overexpression or knockout were harvested for western blotting with the indicated antibodies (n = 3 independent experiments). f Phos-tagTM SDS-PAGE analysis of MYC extracted from MHCC97H cells treating with CIAP (n = 3 independent experiments). g LC-MS/MS spectrum showing the phosphorylation of MYC S281 and S293. h Schematic diagram showing the phosphorylation site of MYC detected by LC-MS/MS (up), and the MYC amino acidic sequence near S281 and S293 from various species (bottom). i Molecular docking model of VRK2 and MYC. j Immunoprecipitation assay of interaction between mutant HA-MYC and Flag-VRK2 in HEK293T cells with MG132 were harvested for western blotting with the indicated antibodies (n = 3 independent experiments). k Vitro kinase assay of the protein interaction between GST-MYC WT, GST- MYC S281A or GST- MYC S293A, and Flag-VRK2 WT or Flag-VRK2 MUT. GST coding sequences were cloned onto the N-terminus of MYC. Followed by Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies (n = 3 independent experiments). l MHCC97H cells with interference with VRK2 expression using siRNA. were harvested for western blotting with the indicated antibodies (n = 3 independent experiments). For Western blot experiments, GAPDH was used as a loading control (e, j, i). a P values were calculated using standard accumulative hypergeometric statistical test. c, d P values were calculated using a student’s unpaired t-test (two-tailed). Data were presented as the mean ± SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

VRK2 reduces polyubiquitination degradation of the MYC by directly mediated phosphorylation of MYC at S281 and S293

Once we established that that VRK2 could directly promote MYC phosphorylation, we aimed to determine its impact on MYC expression. WB and RT-PCR analyses revealed that VRK2 influences MYC expression at the protein level, not the mRNA level (Fig. s7a, b), This indicates that VRK2 regulates MYC post-transcriptionally. Furthermore, we treated HEK293T cells and HCC cells with cycloheximide (CHX), which were either overexpressing or knocking out VRK2. The results indicated that MYC’s half-life was extended with VRK2 WT overexpression and unaffected by VRK2 MUT. Conversely, VRK2 knockout shortened MYC’s half-life. (Fig. 4a, b and Fig. s7c).

a, b CHX chase assays in Hep3B (VRK2 overexpression) and MHCC97H (VRK2 knockout) cells treated with CHX (20 μM). Quantified MYC levels normalized to GAPDH (bottom). c Co-IP of VRK2, MYC, and Ub in HLF cells overexpressing VRK2 and transfected with MYC-tagged Ub plasmids, with MG132 (10 μM, 4 h). d Co-IP of Flag-VRK2, HA-MYC, and MYC-tagged Ub K48 in HEK293T cells (MG132-treated). e Western blot analysis of HA-MYC in HEK293T were transfected with Flag-FBXO24 WT, Flag-FBXO24ΔF-box and HA-MYC plasmids. f, g Immunoprecipitation assay of interaction among MYC, VRK2, or FBXO24 in HLF (up) and MHCC97H cells (bottom). h Co-localization analysis of MYC and FBXO24 in MHCC97H cells. Scale bar: 20 μm. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (n = 3 independent experiments). i Western blot analysis of VRK2, MYC, and FBXO24 in knockout VRK2 MHCC97H cells with interference with FBXO24 expression using siRNA. j Co-IP of MYC, VRK2, or FBXO24 in HEK293T with CIAP treatment. k Co-IP of Flag-VRK2, HA-FBXO24, and MYC-tagged MYC in HEK293T (MG132-treated). l Co-IP of VRK2, FBXO24, and MYC in HLF cells overexpressing oe-VRK2 WT/MUT (MG132-treated). m Co-IP of VRK2, FBXO24, and MYC in MHCC97H cells with sgCON/sgVRK2 (MG132-treated). n–p Co-IP of Flag-FBXO24, MYC-tag Ub, HA-MYC WT or HA-MYC S281A/S281D (n) or HA-MYC S293A/S293D (o) or HA-MYC S281A + S293A(2SA)/S281D + S293D(2 SD) (p) in HEK293T cells and incubated with MG132 (10 μM) for 4 h. For Western blot experiments, GAPDH was used as a loading control (a–e, i–p). The cells involved in the above experiments were harvested for western blotting with the indicated antibodies (n = 3 independent experiments). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further explore how VRK2 regulates MYC protein levels, we treated MHCC97H cells with VRK2 knockout with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, the autophagy-lysosome inhibitor CQ, the caspase inhibitor QVD, and a negative control, DMSO, to block protein degradation pathways. Our results indicated that MYC protein levels significantly increased with MG132 treatment, while the other inhibitors had no effect on MYC degradation (Fig. S7d). This suggests that VRK2 regulates MYC protein expression by modulating the proteasomal degradation pathway. Subsequent co-IP assays revealed that VRK2 overexpression reduced MYC ubiquitination levels, and conversely, VRK2 knockout increased them (Fig. 4c and Fig. s7e, f). Further analysis showed that this effect is due to VRK2 mediating K48-linked polyubiquitination of MYC, not K63-linked polyubiquitination (Fig. 4d and Fig. s7g).

Given that VRK2 is not an E3 ubiquitination ligase, the ubiquitination and degradation of MYC must involve an E3 ligase. We identified three candidate E3 ubiquitination ligases—FBXO24, FBXO16, and TRIM28—from the mass spectrometry data. Initially, we employed a gradient transfection method to determine if MYC protein levels would change with increasing ligase expression. The results indicated that MYC protein levels decreased only with increasing FBXO24 levels. This effect was abolished after the deletion of the F-Box domain of FBXO24, suggesting that MYC protein expression is regulated by FBXO24’s ligase activity (Fig. 4e and Fig. s8a, b). Next, we conducted co-IP assays to investigate the interaction between FBXO24 and MYC. The findings revealed that FBXO24 interacts with MYC, but not with VRK2 (Fig. 4f, g and Fig. s8c, d).

Immunofluorescence assays further confirmed the interaction between FBXO24 and MYC (Fig. 4h and Fig. s8e). We then investigated the potential relationship among VRK2, MYC, and FBXO24. In HCC cells with VRK2 knockout, FBXO24 expression was downregulated using siRNA. We found that FBXO24 deletion significantly restored MYC protein expression (Fig. 4i and Fig. s8f). In HEK293T cells, the addition of CIAP to dephosphorylate MYC led to a stronger interaction with FBXO24 (Fig. 4j). These results suggest that the interaction between FBXO24 and MYC is enhanced when VRK2 is absent or when MYC phosphorylation is decreased. Additionally, we performed co-IP assays with FBXO24 using MYC deletion and truncation mutants as described earlier (Fig. s1g–i). We discovered that FBXO24 did not interact with MYC segments 1–144 and 221–345 (Fig. s1h), and MYC did not interact with the C-terminus of FBXO24 (Fig. s1h, i).

We then investigated the specific sites on MYC that are affected by FBXO24-mediated ubiquitination. We transfected HEK293T cells with plasmids expressing different truncated segments of MYC and treated them with MG132. The results indicated that the protein expression of the MYC segment spanning amino acids 221–345 was most significantly restored (Fig. s9a). Additionally, in ubiquitination-IP assays with these truncated segments, the ubiquitination level of the 221–345 segment increased most markedly in the presence of FBXO24 (Fig. s9b). These findings suggest that FBXO24 can influence the ubiquitination of this truncated protein, even though it does not directly interact with the 221–345 region. We next predicted ubiquitination sites within the 221–345 segment and identified eight potential sites. After mutating these sites, we performed ubiquitination-IP assays. The results revealed that FBXO24’s regulation of ubiquitination was abolished when the K323 site was mutated (Fig. s9c), indicating that FBXO24 mediates MYC ubiquitination at the K323 site. We also treated MYC-K323R and MYC WT with CHX and found that the half-life of MYC was extended upon mutation of this site, thereby increasing its protein stability (Fig. s9d).

Next, we conducted competitive co-IP assays in HEK293T cells and in cells with stable overexpression or knockout of VRK2. We found that as VRK2 WT levels increased, it led to a weakening of the interaction between FBXO24 and MYC, while VRK2 MUT had no effect. Conversely, VRK2 knockout enhanced the interaction between FBXO24 and MYC (Fig. 4k–m). As we previously established that VRK2 can phosphorylate two specific MYC sites, we directly explored whether phosphorylation mutations at these sites could affect MYC protein stability. CHX assays showed that MYC protein stability was significantly increased after activating mutations at both sites, and the opposite effect was observed with inactivating mutations (Fig. s10a). We further performed ubiquitination-IP assays on mutated MYC and demonstrated that activating mutations at both sites significantly reduced FBXO24 binding to MYC, along with the level of ubiquitination (Fig. 4n–p and Fig. s10b). This suggests that these two phosphorylation sites can indeed influence MYC protein stability. In summary, VRK2 reduces FBXO24-mediated polyubiquitination and degradation of MYC at K323 by activating phosphorylation at both S281 and S293.

VRK2 regulates MYC target genes and promotes HCC progression dependent on phosphorylation of MYC at S281 and S293

After establishing VRK2’s role in the post-transcriptional regulation of MYC, we examined the effects of phosphorylation at the S281 and S293 sites on MYC target genes. We divided MHCC97H WT cells into two groups and transfected them with si-VRK2 and si-MYC, respectively. We then performed RNA sequencing and CUT-Tag sequencing, focusing on the overlap of differentially expressed genes. The results showed a significant correlation between the differentially expressed genes in the si-VRK2 and si-MYC groups when compared to the control group. Thirteen genes were commonly affected, and we selected six well-known MYC pathway genes for further correlation analysis, which confirmed a strong positive correlation with VRK2 levels (Fig. 5a and Fig. s11a). Next, we transfected MHCC97H and HepG2 cells with si-NC, si-VRK2, si-MYC, si-MYC + HA-MYC WT, si-MYC + HA-MYC S281A, si-MYC + HA-MYC S281D, si-MYC + HA-MYC S293A, and si-MYC + HA-MYC S293D. The other group we transfected MHCC97H and HepG2 cells with WT, sgVRK2, sgVRK2 + HA-MYC WT, sgVRK2 + HA-MYC S281A, sgVRK2 + HA-MYC S281D, sgVRK2 + HA-MYC S293A, and sgVRK2 + HA-MYC S293D. We verified the transfections by RT-PCR (Fig. 5b and Figs. s11b, s12a, b). The results showed that knocking down VRK2 or MYC expression inhibited the mRNA expression of six downstream target genes. Activating mutations at the two MYC phosphorylation sites (S281D and S293D) significantly enhanced target gene expression, while inactivating mutations (S281A and S293A) had the opposite effect (Fig. 5b and Figs. s11b, s12a, b). The TSS enrichment plot from CUT-Tag sequencing revealed a significant reduction in MYC-enriched target genes following VRK2 or MYC interference. In contrast, activating the MYC phosphorylation sites increased the number of MYC-enriched target genes, and inactivation decreased it (Fig. 5c, d and Fig. s12c, d). Integrative genomics viewer (IGV) visualizations of PD-L1 and CCND1 genes confirmed our observations (Fig. 5e and Fig. s12e). According to the above two grouping forms, we also performed CUT-RUN assays to verify the changes of the above six target genes by RT-PCR in MHCC97H and HepG2 cells. The results showed that the change levels of the six target genes in the two groupings were indeed consistent, as shown by CUT-Tag (Fig. s11c, d and Fig. s12f, g). Notably, VRK2 was among the differentially expressed genes identified in the si-MYC RNA-seq analysis. This discovery led us to hypothesize that MYC functions as a transcription factor for VRK2, upregulating its expression at the transcriptional level. To test this hypothesis, we manipulated MYC expression in HCC cells by overexpression and knockdown, resulting in corresponding increases and decreases in VRK2 expression at both the RNA and protein levels (Fig. s13a–h). These findings confirmed that MYC indeed enhances VRK2 expression at the transcriptional level.

a Venn plots of RNA-seq and CUT-Tag shows the number of differential gene results for si-VRK2 and si-MYC in MHCC97H cells. b qRT-PCR analysis of MYC targets genes in MHCC97H cells after gradient transfection of the si-NC, si-VRK2, si-MYC, si-MYC + MYC WT, si-MYC + MYC S281A, si-MYC + MYC S281D, si-MYC + MYC S293A or si-MYC + MYC S293D siRNA or plasmids (n = 3 independent experiments). c, d Heatmaps (c) and averaged plots (d) of MYC CUT-tag signal intensities (normalized against spike-in control and sequencing depth) around peak centers in MHCC97H cells. e IGV views of MYC at PD-L1 (left) and CCND1 (right) in MHCC97H cells. f Luciferase activities of VRK2 promoter reporter vectors in MHCC97H cells after MYC overexpression or silence (n = 3 independent experiments). g CUT-RUN assays followed by qRT-PCR and analysis was conducted in MHCC97H cells (n = 3 independent experiments). h Schematic diagram of different combinations (MYC WT/ MYC S281A/ MYC S281D/ MYC S293A/ MYC S293D) of oncogenic plasmids (Myc/sgTp53/SB100) with luciferase injected into C57BL/6 J mice (n = 7 mice in each group). i Representative images are presented that show the liver with tumor images. Gross image Scale bar: 1 cm, H&E image Scale bar: 200 μm. j Tumor numbers of HTVi models (n = 7 mice in each group). b, f, j P values were calculated using a student’s unpaired t-test (two-tailed). Data were presented as the mean ± SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further identified three potential MYC binding sites in the VRK2 promoter and conducted deletion and truncation mutations on the promoter, followed by reporter gene assays (Fig. 5f). The results indicated that MYC binds to the E-box-3 region of the VRK2 promoter, which was further validated by CUT-RUN analysis (Fig. 5g). To explore the impact of phosphorylation at the S281 and S293 MYC sites on tumor growth, we injected MYC (WT, S281A/D, and S293A/D) into C57B6/J mice using the HTVi model (Myc/sgTp53) (Fig. 5h). The overexpression of S281D and S293D mutants significantly promoted HCC growth (Fig. 5i, j). These findings suggest a positive feedback mechanism between VRK2 and MYC. VRK2 can directly increase the phosphorylation of MYC at S281 and S293, enhancing the transcriptional activity of MYC. This, in turn, leads to increased expression of oncogenic target genes, including VRK2 itself, thereby promoting HCC progression.

Targeting VRK2 can reduce PD-L1 levels and reduce HCC progression

Given VRK2’s critical role in stabilizing MYC and promoting HCC progression, we hypothesized that targeting VRK2 could be a therapeutic strategy for HCC. To explore this possibility preclinically, we sought to identify VRK2 inhibitors. Through virtual screening, we identified AZD7762 as a potential VRK2 inhibitor. Molecular docking studies, using the crystal structure of VRK2, showed a strong affinity of AZD7762 for key VRK2 residues (Fig. 6a and Fig. s14a). To confirm this interaction, we performed IC50 assays, which revealed IC50 values of 9.957 nm for the control group and 29.37 nm for the VRK2 knockdown group in MHCC97H cells (Fig. 6b).

a Molecular docking of AZD7762 with VRK2 (PDB:2V62). b IC50 assay demonstrated high inhibitory potency and selectivity of AZD7762 for VRK2 (n = 6 independent experiments). c Enzyme activity assay confirmed VRK2 selectivity (n = 6 independent experiments). d In vitro kinase assay showed AZD7762 inhibited MYC phosphorylation, proteins were harvested for western blotting with the indicated antibodies (n = 6 independent experiments). e CCK-8 assays in VRK2-knockout MHCC97H cells treated with DMSO/AZD7762 for 12 h (n = 6 independent experiments). f Representative images of colony formation and quantification (left/right panel) post-treatment (n = 6 independent experiments). g Representative EdU assay image of MHCC97H cells after VRK2 knockout, which were treated with DMSO or AZD7762 for 12 h and quantification (left/right panel) post-treatment (n = 6 independent experiments). h qRT-PCR analysis of PD-L1 expression, which was treated with DMSO or AZD7762 for 12 h (n = 3 independent experiments). i Western blot analysis of PD-L1 expression, which were treated with DMSO or AZD7762 for 12 h, cells were harvested for western blotting with the indicated antibodies (n = 3 independent experiments). j Flow cytometry analysis of PD-L1 expression, which was treated with DMSO or AZD7762 for 12 h (n = 3 independent experiments). k Schematic of DEN/CCL4-induced HCC model in WT C57BL/6J mice (n = 7 mice in each group) and dosing strategy. l Liver tumor images: H&E, Oil Red, Ki67, PD-L1 and CD8 staining of isolated liver tissues. Gross image Scale bar: 1 cm, IHC image Scale bar: 200 μm. m Western blot analysis in mice HCC tissues. After prophylactic and therapeutic of AZD7762, cells were harvested for western blotting with the indicated antibodies (n = 3 independent experiments). n Tumor volume of the indicated models (n = 7 mice in each group). o Tumor numbers of indicated models (n = 7 mice in each group). p, q Serum AST/ALT levels in models (n = 7 mice in each group). r Body weight measured. After prophylactic and therapeutic of AZD7762 indicated models (n = 7 mice in each group). For Western blot experiments, GAPDH was used as a loading control (i, m). c, e, g, h, n–r P values were calculated using a student’s unpaired t-test (two-tailed). Data were presented as the mean ± SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

These findings highlight the high specificity of AZD7762 for VRK2. Given the essential role of ATP binding in VRK2’s kinase activity, we hypothesized that AZD7762 might act as an ATP mimetic. Both in vitro enzyme activity and kinase assays showed that AZD7762 significantly inhibited ATP consumption by VRK2, resulting in reduced enzymatic activity (Fig. 6c) and subsequent inhibition of MYC phosphorylation by VRK2 (Fig. 6d). Furthermore, HLF and MHCC97H cells were treated with AZD7762 in a time-dependent manner (Fig. s14b). The results indicated that AZD7762 did not affect VRK2 protein levels over time but consistently reduced MYC protein levels and phosphorylation, consistent with our previous findings.

Next, we evaluated the effect of AZD7762 on HCC cells in vitro using various proliferation assays, including CCK-8, cloning formation, and EdU, on MHCC97H cells in both control and VRK2 knockout groups, with DMSO as a negative control. The results showed a significant inhibitory effect of AZD7762 on the proliferation of control cells, while VRK2 knockout cells were unaffected (Fig. 6e–g). This indicates that AZD7762 inhibits HCC cell proliferation only in the presence of VRK2. As presented above, VRK2 enhances the transcription of MYC target genes, including PD-L1 (Fig. 5b). This led us to explore whether AZD7762 could reduce PD-L1 expression by inhibiting VRK2 activity. We used MHCC97H cells with VRK2 knockout and their controls, as well as HLF cells overexpressing VRK2 and their controls. We evaluated PD-L1 expression at the mRNA, protein, and membrane protein levels. In HCC cells, although MYC overexpression can increase PD-L1 expression, we have difficulty detecting this change in the absence of external stimuli. We therefore added IFN-γ, a strong inducer of PD-L1, to increase its expression level and thus facilitate detection. The findings revealed a substantial increase in PD-L1 expression with VRK2 WT overexpression, whereas VRK2 MUT did not have this effect. Knocking out VRK2 led to reduced PD-L1 expression at the mRNA, protein, and membrane protein levels (Fig. s14c–h). Additionally, AZD7762 treatment reduced PD-L1 expression in control cells but had no effect in VRK2 knockout cells (Fig. 6h–j). CUT-Tag assays in MHCC97H cells revealed a significant decrease in the enrichment of MYC target genes after AZD7762 treatment. Furthermore, the enrichment of MYC at the PD-L1 promoter region was substantially reduced (Fig. s14i–k).

Building on this foundation, we investigated the potential association between VRK2 expression and immune cell infiltration, as well as immune-related signals in the HCC microenvironment. Using the TCGA-LIHC dataset, we analyzed the correlation among immune responses, immune-related signaling activation, and immune cell infiltration as indicated by the reported characteristics (Fig. s15a). The findings revealed a significant association between VRK2 expression and immune response, immune-related signaling activation, as well as immune cell infiltration. Furthermore, the expression levels of various immune checkpoints showed a correlation with VRK2 expression (Fig. s15b). Additionally, we performed an analysis of immune cell infiltration using published single-cell datasets, categorizing them based on high and low VRK2 expression (Fig. s15c, d). The results indicated that high expression of VRK2 downregulates the degree of T cell infiltration in the immune microenvironment of HCC. Therefore, the use of AZD7762 may enhance the efficacy of ICB.

To evaluate the impact of AZD7762 on tumorigenesis, we administered intraperitoneal injections of AZD7762 at a dose of 25 mg/kg to mice every two days for a total of 14 injections, using the DEN/CCl4 HCC model (Fig. 6k). The findings revealed a significant reduction in tumor burden in both the prophylactic and therapeutic groups compared to the control group. AZD7762 treatment also reduced the levels of MYC protein and its phosphorylation in the tumors of mice (Fig. 6m). Oil Red staining confirmed the consistency of the model, while H&E and Ki67 staining demonstrated that AZD7762 significantly suppressed tumor proliferation (Fig. 6l). Additionally, AZD7762 inhibited PD-L1 expression and enhanced CD8+ T cell infiltration in the HCC microenvironment (Fig. 6l). Furthermore, it reduced both tumor volume and the incidence of tumor formation (Fig. 6n, o). Notably, these effects were not observed in the group of vrk2 f/f+alb-cre mice. Crucially, AZD7762 significantly reduced serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (Fig. 6p) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (Fig. 6q) levels, nor did it affect the body weight of the mice (Fig. 6r). This indicated that AZD7762 treatment does not cause liver damage. Therefore, AZD7762 appears to be a promising inhibitor for the safe and effective prevention and treatment of HCC through targeting VRK2 kinase.

Combining VRK2 inhibitor with anti-PD-1mAb enhances T cell-mediated antitumor response in a mouse model of HCC

Given that AZD7762 treatment in vivo suppresses tumor growth by reducing PD-L1 expression, we first constructed HTVi models of sg-vrk2 and its control mice. When the mice were grown to 28 days, we randomly divided each group into two groups. One group received anti-PD-1 treatment, while the other group was given isotype IgG as a control. The treatment cycle was two weeks, with the drug administered twice a week, and the mice were eventually executed and samples collected at 45 days (Fig. s16a). We first performed WB assays on the collected mice liver tumor tissues to verify the efficiency of sg-vrk2 (Fig. s16b). Meanwhile, we measured the tumor volume and liver/body weight ratio to assess the tumor growth (Fig. s16c). In addition, we performed immunohistochemical experiments and counted the IHC scores (Fig. s16g–i). The results showed that anti-PD-1 treatment significantly reduced the liver/body weight ratio (Fig. s16d) and tumor volume (Fig. s16e) in mice in both the sg-vrk2 group and the control group. In the control group, anti-PD-1 treatment significantly prolonged the survival time of mice (Fig. s16f), whereas in the sg-vrk2 group, although a decrease in the immunohistochemical score of PD-L1 was observed (Fig. s16g), no significant prolongation of survival time was observed (Fig. s16f), which might be related to the insufficient observation time. In addition, we found that anti-PD-1 treatment was able to increase the proportion of CD8+ T cells (Fig. s16h) and the secretion level of GZMB (Fig. s16i) in the sg-vrk2 group, suggesting that anti-PD-1 treatment may have a better therapeutic effect in the sg-vrk2 group. Taken together, our findings suggest that anti-PD-1 therapy may produce superior therapeutic effects by modulating the immune microenvironment and enhancing the antitumor activity of T cells in the context of sg-vrk2. Then we hypothesized that AZD7762 could enhance the therapeutic effectiveness of anti-PD-1 blockade. To test this hypothesis, we generated two mouse models using DEN/CCl4 (Fig. 7a) and HTVi (Myc+sgTp53) (Fig. 7c) to induce HCC. Upon confirming tumor formation, we used IgG isotype as the negative control for Anti-PD-1mAb (100 μg/mouse) and saline as the negative control for AZD7762 treatment (25 mg/kg). Mice were then randomly assigned to four groups: Vehicle + IgG (negative control), AZD7762 alone (AZD7762), anti-PD-1mAb alone (Anti-PD-1), and combined treatment with AZD7762 and Anti-PD-1mAb (Combined) (Fig. 7b, d). Based on MRI and bioluminescence imaging, AZD7762 showed therapeutic efficacy in both models. However, Combined treatment demonstrated significantly superior therapeutic outcomes compared to AZD7762, anti-PD-1mAb alone, or the negative control (Fig. 7b, d). To further validate our findings, we performed IHC and WB assays on mouse HCC tissues, and the IHC results showed that the combination therapy significantly reduced tumor load and decreased PD-L1 expression while increasing immune cell infiltration (Fig. 7b, d and Fig. s17a–f). The WB results showed that the Combination therapy reduced the protein expression of PD-L1, MYC, and the phosphorylation level of MYC, but did not affect the phosphorylation level of VRK2 itself (Fig. s18a, b). This superiority is evident in liver appearance, H&E staining (Fig. 7b, d), and the combination treatment extended the survival time of mice to some extent (Fig. s18c, d). Liver/body weight ratio (Fig. s18e, g), and tumor number (Fig. s18f, h). Throughout the treatment, the body weight of each mouse group (Fig. s18i, m) and the creatinine (Fig. s18j, n), ALT (Fig. s18k, o) and AST (Fig. s18l, p) in mice serum remained within the normal range, indicating the potential safety of this combined treatment approach in future clinical trials.

a Schematic representation of the DEN/CCL4 HCC development model induced in WT C57BL/6J mice (n = 5 mice in each group) and drug delivery strategy. b DEN/CCL4 model in C57BL/6J mice with representative images are presented that show the MRI images, liver with tumor images and H&E, Oil Red, Ki67, PD-L1, and CD8 staining of isolated liver tissues. Gross image Scale bar: 1 cm, IHC image Scale bar: 200 μm. c Schematic representation of the HTVi HCC development model (Myc/sgTp53) induced in WT C57BL/6J mice (n = 5 mice in each group) and drug delivery strategy. Gross image Scale bar: 1 cm, IHC image Scale bar: 200 μm. d HTVi model in C57BL/6J mice with representative images are presented that show the bioluminescence, liver with tumor images and H&E, Oil Red, Ki67, PD-L1, and CD8 staining of isolated liver tissues. e, f Flow cytometry analysis of CD3+, CD8+, CD69+CD8+, IFN-γ+CD8+, and PD-1+CD8+ in TILs from DEN/CCL4 model or HTVi model tumors tissues in C57BL/6J mice (n = 5 mice in each group). e, f P values were calculated using a student’s unpaired t-test (two-tailed). Data were presented as the mean ± SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We also performed flow cytometry to detect differences in lymphocyte infiltration among various subgroups of mice. Our findings revealed that AZD7762 treatment led to a decrease in PD-1 expression on the surface of T cells in both groups of models, suggesting that the immune microenvironment of mice HCC tumors is modulated by AZD7762. Consequently, AZD7762 could be combined with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy to achieve a synergistic effect. Although the efficacy of Anti-PD-1mAb alone in treating mouse HCC tumors is limited, AZD7762 combined with Anti-PD-1mAb therapy induced robust immune responses, This included an increase in the number of T cells, specifically an increase in the proportion of CD8+ cells, an increase in the proportion of CD69+ CD8+ cells, and an elevation in IFN-γ levels (Fig. 7e, f Fig. s17g, h). The functionality of these immune cells was enhanced, thereby reducing the tumor burden in mouse HCC. In conclusion, these results strongly indicate that VRK2 inhibition enhances CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor immunity by regulating PD-L1 expression, making it a promising target for combination immunotherapy in mouse.

VRK2 expression is associated with higher MYC, PD-L1 and lower CD8 CTL levels in HCC

To validate our hypothesis, we initially confirmed the expression relationship of VRK2, MYC, FBXO24, p-MYC S281, and p-MYC S293 using HCC patient tissue protein samples (Cohort 3). Our analysis revealed that there was a positive correlation between VRK2 and MYC (Pearson r = 0.7629, p < 0.0001) as well as the expression of p-MYC S281 (Pearson r = 0.7682, p < 0.0001), p-MYC S293(Pearson r = 0.6774, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 8a, b), but FBXO24 was a negative correlation between p-MYC S281 (Pearson r = −0.3249, p = 0.0213), p-MYC S293(Pearson r = −0.2175, p = 0.0129) (Fig. s19a, b). Concurrently, we investigated the correlation between VRK2, MYC, and PD-L1 in tissue microarrays (TMA) of HCC patients (Cohort 1). The r TMA analysis demonstrated that the expression of MYC & PD-L1 (R2 = 0.4222, p < 0.0001) and VRK2 & PD-L1 (R2 = 0.3966, p < 0.0001), were all positively correlated (Fig. 8c–e). Furthermore, we analyzed the expression relationships among VRK2, MYC, PD-L1, CD8, and GZMB in TMA using multicolor immunohistochemistry (mIHC). The mIHC results also showed that the expression of VRK2 and MYC were all positively correlated with the expression of PD-L1 (Fig. 8f). Additionally, the levels of VRK2 and PD-L1 were found to correlate with the activity of CD8+ T cells, and the infiltrating GZMB+CD8+ T cell activity was negatively correlated (Fig. 8f). These findings are consistent with the results of in vitro and in vivo studies. To investigate the role of VRK2 in tumorigenesis and whether it is dependent on MYC, we applied the HTVi model (Akt+Nras) in mice for the replication experiments. The assays aimed to observe whether the pro-tumorigenic effect of VRK2 and its influence on the immune microenvironment needed to be realized through MYC. For this purpose, we divided the mice into four groups: the negative control (NC) group, the vrk2 WT group, the vrk2 WT+ sgCON group and the vrk2 WT+sg-myc group. And the relevant samples were harvested at 54 days (Fig. s19c).

a Western blot analysis o in 50 HCC and paracancerous tissues from cohort 3 patients, cells were harvested for western blotting with the indicated antibodies (n = 3 independent experiments). b Correlation analysis of the MYC, p-MYC S281, p-MYC S293, and VRK2 protein levels in HCC cohort 3. c Representative IHC images of VRK2, MYC and PD-L1 staining of clinical HCC cohort 1. Scale bar: 100 μm (left)/25 μm (right). d, e IHC staining score of PD-L1, MYC, and VRK2 has a high correlation in HCC cohort 1. f mIHC staining analysis of PD-L1, MYC, VRK2, CD8, and GZMB has a high correlation in HCC cohort 1. Scale bar: 100 μm (left)/25 μm (right). g–j Kaplan–Meier analysis of OS (g, h) and PFS (i, j) for different VRK2/MYC expressions in TCGA-LIHC datasets and Cohort 1. For Western blot experiments, GAPDH was used as a loading control (a). b, e P values were calculated using a Spearman correlation analysis (two-tailed). g–j P values were calculated using a Kaplan–Meier test (two-tailed). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the collected mouse liver tumor tissues, we performed IHC to assess the efficiency of MYC knockdown (Fig. s19d, g). In addition, we measured liver/body weight ratio to quantitatively assess the tumor growth. To further understand the immune response in the tumor microenvironment, we also performed immunohistochemical experiments and counted the immunohistochemical scores (Fig. s19c). The experimental results revealed that in the sg-myc group, we observed a significant reduction in the liver/body weight ratio (Fig. s19e) of mice, as well as a significant prolongation of survival time (Fig. s19f). In addition, we found that the expression of PD-L1 was decreased (Fig. s19h), and the proportion of CD8+ T cells (Fig. s19i) and the secretion level of GZMB (Fig. s19j) were increased in the sg-myc group, suggesting that the immune microenvironment might have been regulated by knockdown of myc, which enhanced the antitumor activity of T cells. Taken together, our results suggest that the pro-tumorigenic effect of VRK2 may be partially dependent on MYC. by knocking down MYC, we were able not only to inhibit tumor growth, but also to improve antitumor immune responses by enhancing the function of immune cells.

Furthermore, patients with high expression levels of both VRK2 and PD-L1/VRK2 and MYC exhibited the poorest OS and PFS in the prognostic analyses conducted in both the TCGA database and our patient cohort 1 (Fig. 8g–j). These results suggest that VRK2 and MYC have similar expression patterns in HCC, and that high expression of VRK2 and MYC is indicative of a poor prognosis. The results imply that VRK2 holds potential clinical significance and could serve as a biomarker for HCC diagnosis and prognosis.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified a critical link between increased VRK2 expression in HCC and the stability of the MYC protein. Our findings reveal that VRK2 enhances MYC protein stability, thereby activating MYC downstream target genes, including oncogenes such as PD-L1. This discovery not only illuminates the role of VRK2 in HCC progression but also paves the way for a therapeutic strategy. Specifically, our study suggests that combining VRK2 inhibition with anti-PD-1 therapy could represent a potential breakthrough in HCC treatment.

Over the past three decades, chromosomal rearrangements and genetic mutations have been identified as key contributors to a variety of human malignancies, associated with the dysregulation and dysfunction of proteolipid kinases and inactivated phosphatases30,31. Beyond oncological implications, kinase dysregulation has been observed in diverse human diseases, including immune, neurological, and infectious disorders32,33,34,35. VRK2, an active kinase initially recognized in 1997 as a putative serine/threonine kinase, bears structural resemblance to the cowpox virus B1R kinase36,37. Initially identified in highly proliferating cells such as the testis, thymus, and fetal liver, its expression has since been confirmed throughout the human brain’s life cycle38,39. Recent studies have shown that VRK2 activates TKT in hepatocellular carcinoma by promoting Thr287 phosphorylation of TKT and increases PD-L1 expression through the ROS-mTOR signaling axis, leading to immune escape and tumor metastasis40. Meanwhile, VRK2 also promotes tumor formation and metastasis in HCC in male mice by phosphorylating the Ser151 site of GAPDH, recruiting FBXW10 to reduce its ubiquitination, activating the NF-kB signaling pathway, and increasing PD-L1 and AR-VRK2 expression41. Our study reveals that overexpression of VRK2 accelerates the progression of various mouse HCC models, while the deletion of VRK2 impedes HCC development in mouse. These findings underscore the pivotal role of VRK2 in HCC development.

Numerous studies have underscored the critical role of MYC in HCC, indicating MYC as a promising therapeutic target42,43,44. However, direct targeting of MYC presents significant challenges, leading researchers to seek alternative proteins that could regulate MYC expression indirectly14,16. MYC’s oncogenic potential is attributed to its interactions with a multitude of proteins, forming a complex protein interactome. A promising strategy has been to disrupt MYC’s function by inhibiting its interactions with target proteins or blocking their association with MYC has emerged as a promising strategy14. Various approaches have been explored, including inhibiting MYC’s binding to its co-factors45,46, suppressing its expression47, and inducing synthetic lethality through MYC overexpression48,49, have been explored. Despite these efforts, no compounds have been identified that are suitable for clinical testing. Targeted protein degradation (TPD) has recently emerged as a therapeutic strategy, offering the potential to target previously undruggable proteins50. Moreover, small molecules that promote MYC degradation are being considered as potential treatments for MYC-driven malignances51.

Ubiquitination, a highly regulated post-translational modification, governs numerous cellular pathways crucial for cellular homeostasis. Ubiquitin ligases recruit substrates and facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin to the target, which can either induce proteasomal degradation or modulate non-degradation signaling pathways. Ubiquitination is involved not only in protein degradation but also influences protein activity and localization52. In this study, we report that the overexpressed VRK2 in HCC acts as a kinase targeting MYC, leading to the phosphorylation of MYC at the S281 and S293 sites. Phosphorylation of target proteins by VRK2 induces changes in their ubiquitylation levels, influencing cellular processes and potentially contributing to the initiation of tumorigenesis. For example, VRK2 phosphorylates MSX2, promoting its binding to FBXW2 and subsequent ubiquitination and degradation of MSX237. Next, we clarified that VRK2 induces phosphorylation of the MYC S281 and S293 sites, which inhibits FBXO24-mediated ubiquitination of the MYC K323 site and enhances MYC protein stability. This stabilization reinforces the oncogenic potential to drive HCC development. VRK2 enhances the binding of MYC to the promoters of target genes, including SLC1A5, VEGFA, PD-L1, CDK4, and CCND1, which are closely associated with HCC progression53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61. In the mouse model of HCC, activation of MYC at S281 and S293 significantly enhances tumor growth. Although VRK2 is most well-known for its role in tumorigenesis, the mechanisms underlying its function in tumor immunotherapy require further clarification. Silencing of VRK2 could reduce PD-L1 levels and enhance antitumor immunity by boosting T cell cytotoxicity and diminishing the immunosuppressive capacity of tumor cells. We propose a combinatorial therapeutic strategy targeting both VRK2 and the PD-1 pathway for HCC treatment in mouse. Inhibition of VRK2 in mouse HCC tumors, in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy, synergistically suppresses tumor growth and promotes T cell infiltration. This, in turn, reinvigorates IFN-γ and GZMB in CD8+ T cells. In summary, our study demonstrates that VRK2 enhances the protein stability of MYC and activates MYC downstream target genes by phosphorylating the S281 and S293 sites. Furthermore, VRK2 reduces ubiquitination at the K323 site by FBXO24. By orchestrating the creation of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in HCC, VRK2 enriches suppressor CD8+ T cells, thereby facilitating HCC progression (Fig. 9). Our research also suggests a potential therapeutic strategy for HCC, which involves targeting VRK2 in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy. However, this study has certain limitations: The limitations of the in vitro kinase assay and ubiquitination assay, as they may not fully represent the complex in vivo modification scenarios, necessitating further investigation. Although AZD7762 effectively inhibits the development and progression of the mouse HCC model and shows synergy with anti-PD-1, its clinical application has not yet been established. Therefore, it is imperative to discover VRK2 inhibitors with potential clinical utility and liver-specific activity for the future clinical treatment of HCC AZD7762, which is capable of degrading MYC, exhibits a strong inhibitory effect on tumor growth. While our study concentrates on HCC, additional research is needed to determine the broad anticancer efficacy of AZD7762 across different cancer types. Consequently, this study provides insights into cancer targeting and immunotherapy strategies for HCC. Given that MYC is amplified in my cancer types, it deserves to be examined for the potential effect in other cancers.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital (HUST, Wuhan, China), and informed consent was obtained from all the patients regarding the use of tissue samples (approval no. TJ-IRB20211163). Clinical data of HCC patients who underwent curative hepatectomy in Tongji Hospital were collected. All participants provided written informed consent. None of the HCC patients received neoadjuvant therapy, and their tumor tissue sections were obtained from the Hepatic Surgery Center, Tongji Hospital.

All animal experiments were approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital, HUST. According to the guidelines (GB/T35892-2018), the ethics committee specified that the maximal tumor burden is no more than 10% of the body weight of animals and the average diameter is less than 20 mm. During the experiment, the tumor sizes of the mice complied with the regulations. This study adhered to the guidelines outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The gender of the mice used in the experiment was all male.

Clinical tissue samples

Three independent cohorts of HCC patients were recruited from the Hepatobiliary Center of Tongji Hospital, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST), Wuhan, China. All samples were stored at −80 °C. Cohort 1 comprised 109 pairs of HCC tissue samples (91 men and 18 women) collected from patients who underwent primary HCC resection at the Hepatic Surgery Center of Tongji Hospital (HUST), Wuhan, China. Samples from this cohort were used to construct microarrays for immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays. Cohort 2 comprised 120 pairs of HCC tissues (pairs consisting of tumor tissue and adjacent tissue from the same patient (85 men and 35 women) for Western blot detection of the VRK2 protein. Cohort 3 included 40 pairs of HCC samples (32 men and 8 women) for Western blot analysis of the VRK2 and MYC proteins. No patient in Cohort 1, Cohort 2, or Cohort 3 received any other HCC treatment before surgery. Each specimen underwent histological and pathological examination and grading by two experienced pathologists. Sex/gender was not considered in the study design and analysis because this study was not designed to detect sex differences.

IHC

Slides were rehydrated in xylene and ethanol after being deparaffinized for IHC. Following a 30-min incubation period with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide, antigen retrieval was carried out using citrate buffer for 15 min at a temperature below the boiling point, and the reaction was blocked for 60 min with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). After that, the slides were then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (specified in the Supplementary Table 6). After that, the sections were incubated for color development using an IHC kit (PV6000/ZLI-9019, ZSGB-Bio, China) and for nuclear counterstaining using hematoxylin. The program Case-Viewer (3DHISTECH, Budapest, Hungary) or a regular microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used to obtain the images. Staining intensity and area of staining were then independently scored by two pathologists who were unaware of the patient’s clinical information.

Immunoblotting assay

For immunoblotting, cells were lysed with cell lysis buffer (P0013, Beyotime, China) supplemented with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, 20104ES03, Yeasen, China), protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (HY-K0013, Med Chem Express, NJ, USA), and then boiled in 4X SDS loading buffer for 10 min. About 10 µl of protein was injected into each well of the Tris SDS/PAGE gel (PAGE Gel Quick Preparation Kit, 20325ES62, Yeasen, China) for electrophoresis, and the gel was transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies, as described in the Supplementary Table 6, overnight at 4 °C and then exposed to species-matched secondary antibodies (GB23303/ GB23301, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) for 60 min at 37 °C. Bands were visualized using a chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Super ECL Detection Reagent, 36208ES76, Yeasen, China) and an electrogenerated chemiluminescence (ECL) imaging system (Bio-Rad, MA, USA).

qRT-PCR

Using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), total RNA was extracted for qRT-PCR, and the reverse transcription kit (R233-01, Vazyme, China) was used for reverse transcription. A spectrophotometer was used to determine the amount and density of RNA. Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix kit (Q711-02, Vazyme, China) was used for qRT-PCR in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Supplementary Table 2 contains a list of primers utilized in qRT-PCR). The 2-ΔΔCt technique was utilized to estimate the relative gene expression after these tests were performed a minimum of three times.

Cell line

The China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC, Wuhan, China) and American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) provided the human HCC cell lines HLF, Huh7, Hep3B, LM3, MHCC97H, HepG2, and PLC/PRF/5 as well as the normal liver cell line THLE3. From the Shanghai Branch Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China), the human embryonic kidney cell line 293 T (HEK293T) was obtained. All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), 10% fetal bovine serum was added, and the temperature was kept at 37 °C in a humid incubator with 5% CO2. All of the cell lines used for this study were also rigorously examined to ensure that mycoplasma was not present, and their authenticity was verified using short-tandem repeat analysis. All the cell lines were authenticated by STR profiling and confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination (Supplementary Table 3 contains a list of cell lines information).

Plasmid construction

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, Lentivirus vectors Plenti-CMV were used for producing recombinant lentiviruses. For example, the overexpressed lentivirus plasmid of VRK2, Flag-tagged full-length VRK2 cDNA (NM_001130480.2), was amplified using PCR and cloned into the vector of Plenti-CMV-3 × flag-Puro. The constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. After transfection, the cells with suitable expression were screened with 2.5 μg/mL puromycin (HY-B1743, Med Chem Express, NJ, USA). Then, the transfection efficiency was verified using qRT-PCR and immunoblotting.

CRISPR/Cas9

The VRK2 gene knockout MHCC97H cell line was generated with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. The single-guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence (supplementary Table 4) was cloned into the lentiCRISPR v2 vector (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA). The plasmid was transfected into MHCC97H cells and selected with 2.5 μg/mL puromycin. A single colony was then selected, expanded, and verified by Sanger sequencing and immunoblotting.

CCK-8

About 1000 cells/100 μL DMEM were seeded in each well of a 96-well flat-bottomed plate. At each time point, discard the supernatant, and 100 μL CCK-8 solution (A311-01, Vazyme, China) was added into the sextuplicate wells. Then the plate was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, and the optical density was measured at 450 nm using a multimode microplate reader. The obtained data were presented as a line chart.

Colony formation

Each well of a six-well flat-bottomed plate is inoculated with 1000 cells/2 mL DMEM and incubated at 37 °C for 7–10 days. The medium was refreshed every 5 days, and fixation and crystal violet staining were performed after the colonies grew to a suitable size. The data obtained is displayed in the form of a bar chart.

5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay

DNA replication cells were detected by EdU assay kit (C0078S, Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to represent cell proliferation activity. In brief, 5000 cells were inoculated in 24-well plates in complete DMEM until 70–80% confluent. DMEM medium containing 50 μM EdU was added and incubated for 2 h, and PBS was washed one to two times. After 4% paraformaldehyde fixation and 0.5% Trixon treatment, 100 μL 1 × Apollo solution was added and incubated for 30 min. Finally, 1 × Hoechst33342 was used for DNA staining and observed under the microscope. Each assay was repeated at least three times.

Cell cycle-flow cytometry

The cells were grown to the logarithmic stage and then plated in 6-well plates. The adherent cells were treated with trypsin without EDTA for 24 h, followed by a PBS wash and a 16-h immobilization period in 75% ethanol at 4 °C. After that, the cells were handled with Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Analysis Kit (C1052, Beyotime, China) for 30 min at 25 °C in the dark, and flow cytometry was used to identify them. At least three repetitions of each assay were conducted.

Animal models

BALB/c nude mice (4–5 weeks, male), wild-type C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks, male) were purchased from the GemPharmatech (Nanjing, China). For hepatocyte-specific Vrk2 knockout, Vrk2f/f mice which purchased from the Cyagen Biosciences (Suzhou, China) were crossed to C57BL/6. Cg-Tg (Alb-Cre)21 Mgn/J mice, which were purchased from the Jax laboratory (USA) to establish Vrk2f/f /alb-cre mice, which were confirmed by PCR genotyping. All animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility in the Laboratory Animal Center of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Wuhan, China). All animals were handled strictly according to the Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal assays were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

To establish subcutaneous tumor xenograft models, BALB/c nude mice were randomly divided into different subgroups (n = 5 mice in each group). Mice were injected with MHCC97H and Hep3B (1 × 106 cells resuspended in 100 μL DMEM) in the left back. Tumor growth was monitored every seven days, and the mice were euthanized after 21 days using pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg). The tumor volume was measured using the following formula: 0.5 × (larger diameter) × (smaller diameter)2.

To establish orthotopic tumor xenograft models, BALB/c nude mice were randomly divided into different subgroups (n = 7 mice in each group). Tumors from subcutaneous tumor tissues (1 cm3) were minced into 1 mm3 cubes and transplanted to the livers of BALB/c nude mice. Tumor growth was monitored with bioluminescence. Upon euthanasia with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg), the tumors were recovered, and the volume of each tumor was determined.

To establish hydrodynamic tail vein injection (HTVi) models, C57BL/6 mice were randomly divided into different subgroups (n = 7 mice in each group). pT3-myr-Akt1-IRES-luciferase (20 μg)/pT3-Nras (20 μg)/ pT3 -Myc-IRES-luciferase (10 μg)/ px458-sgTp53 (10 μg) pT3-vector (20 μg)/ pT3-VRK2 WT (20 μg)/pT3-VRK2 MUT (20 μg) and SB transposase plasmids (1/25 of the total plasmid mass) were dissolved in 2 mL saline. Then, 2 ml of the plasmid mixture was rapidly delivered (6–8 s) through the tail vein to the liver in vivo. Tumor growth was monitored with bioluminescence. Upon euthanasia with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg), the weight of each mouse was determined, and the tumors were recovered; the weight and volume of each tumor was determined.

To establish the DEN models, vrk2 f/f and vrk2 f/f+alb-cre mice (n = 10 mice in each group) were injected intraperitoneally with the chemical carcinogen DEN (25 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich) at the age of 15 days to induce tumorigenesis, then injected with CCl4 (25 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich) at 4 weeks until 16 weeks of age, and sacrificed at 28 weeks. At sacrifice, performing small animal MRI imaging, then whole livers were weighed, and tumors were counted and measured. Tumoral and non-tumoral tissues were harvested for subsequent analysis or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

According to the guidelines (GB/T35892-2018), the ethics committee specified that the maximal tumor burden is no more than 10% of the body weight of animals and the average diameter is less than 20 mm. During the experiment, the tumor sizes of the mice complied with the regulations. All animal care and research were conducted in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals of the National Institutes of Health and approved by the ethics committee of Tongji Hospital (No. TJH-202110029).

LC-MS/MS

Flag-Vector and Flag-MYC plasmids were transiently transfected into 293 T cells. Immunoprecipitates were processed with SDC/TCEP/CAA buffer for reduction, alkylation, and elution (repeated twice). Combined eluates were digested overnight with trypsin, desalted, concentrated by vacuum centrifugation, and stored at −80 °C prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. Proteins were identified using an Orbitrap Exploris 480 LC-MS system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were processed via MaxQuant (v1.6.2.10) with MaxLFQ quantification.

RNA-Seq

For MHCC97H cells requiring RNA-seq, we seeded 500,000 cells in six-well plates and transfected small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting VRK2 (si-VRK2), MYC (si-MYC) and control (si-NC) via Lipofectamine 3000 (Supplementary Table 4 contains a list of sequences). RNA was collected approximately 48 h after the medium was changed. After TRIzol treatment, the cells were sent to Biomarker Technologies Corporation for RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing. Libraries with 300 ± 50 bp insert sizes were constructed and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (LC-Bio Technology) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Reads were aligned to the human genome (Ensembl v96) via HISAT2, assembled into transcripts using StringTie, and annotated with Gffcompare. Transcript quantification (TPM) was calculated using the Ballgown R package. Differential expression analysis was conducted with DESeq2 (adjusted p < 0.05). Pearson correlation identified VRK2-associated coding genes in TCGA-LIHC (cutoffs: p < 0.05, Pearson’s r > 0). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and Gene Ontology (GO) were performed using clusterProfiler, with 50 cancer hallmark gene sets ranked by VRK2 expression correlation. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Co-IP

For the Co-IP assay, cells were collected using the IP lysis buffer supplemented with PMSF, protease, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails. After removing precipitation by centrifugation at 12,000 × g, the supernatant was precleared by protein A/G-magnetic beads (L-1004, Biolinkedin, China). Then, precleared lysates were incubated with primary antibodies (supplementary Table 5, 6) overnight at 4 °C. Protein A/G-magnetic beads were then added to the lysates for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed with IP lysis buffer five times, resuspended in SDS-PAGE loading buffer, boiled, and loaded onto 10% gradient gels. Subsequent immunoblots were probed with corresponding antibodies, and bands were visualized using a chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Super ECL Detection Reagent, 36208ES76, Yeasen, China) and an electrogenerated chemiluminescence (ECL) imaging system (Bio-Rad, MA, USA).

GST-Pulldown assay

For the GST pull-down assay, GST-NC and GST-MYC plasmids were transfected into the Escherichia coli BL21 strain (DE3). After overnight cultures, the bacterial cells were lysed, and GST fusion proteins were captured by Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads at 4 °C for 1 h. The protein G-agarose beads were then washed, boiled in loading buffer, and detected using SDS-PAGE. To investigate the interaction between MYC and VRK2, equal amounts of GST or GST-MYC fusion protein beads were incubated with in vitro-translated VRK2. After washing with ice-cold washing buffer, the proteins were eluted from the beads and detected using immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence