Abstract

Herpesvirales are an ancient viral order that causes lifelong infections in species from mollusks to humans. They export their capsids from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by a noncanonical nuclear egress route that involves capsid budding at the inner nuclear membrane followed by fusion of this temporary envelope with the outer nuclear membrane. Here, using a whole-genome CRISPR screen, we identify ER protein CLCC1 as important for the fusion stage of nuclear egress in herpes simplex virus 1. We also find that the genomes of Herpesvirales that infect mollusks and fish encode CLCC1 genes acquired from host genomes by horizontal gene transfer. In uninfected cells, loss of CLCC1 causes a nuclear blebbing defect, suggesting a role in host nuclear export. We hypothesize that CLCC1 facilitates an ancient cellular membrane fusion mechanism that Herpesvirales have hijacked or co-opted for capsid export and propose a mechanistic model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Herpesvirales are large, enveloped viruses that infect much of the animal kingdom. The order is divided into three families: Malacoherpesviridae infect mollusks, Alloherpesviridae infect fish and amphibians, and Orthoherpesviridae, commonly known as herpesviruses, infect mammals, birds, and reptiles, and cause lifelong infections in most of the world’s population1. The family Orthoherpesviridae is further subdivided into three subfamilies, Alpha-, Beta-, and Gamma-herpesvirinae1. Nine human herpesviruses from these three subfamilies cause diseases ranging from skin lesions to life-threatening eye ailments, encephalitis, cancer, and developmental abnormalities. Prophylactic options are very limited, and current therapeutic strategies are not curative.

Despite substantial sequence divergence across Herpesvirales, key replication steps are conserved, one being nuclear egress. Herpesvirales replicate their double-stranded DNA genomes and package them into capsids within the nucleus. Genome-containing capsids are then exported into the cytoplasm for maturation into infectious virions. Many eukaryotic viruses that replicate their genomes within the nucleus, such as HIV, influenza, and papillomaviruses, escape this double-membraned organelle via the canonical export pathway through the nuclear pore complex (NPC)2. But the ~40–50-nm opening of the nuclear pore3 is too small to accommodate the ~125-nm capsids of herpesviruses. Instead, Herpesvirales use a different, more complex nuclear export route termed nuclear egress4. First, capsids dock and bud at the inner nuclear membrane (INM), forming perinuclear enveloped virions (PEVs) (budding, or envelopment stage). PEVs then fuse their temporary envelopes with the outer nuclear membrane (ONM), releasing unenveloped capsids into the cytoplasm (fusion, or de-envelopment stage).

The budding stage is mediated by the virally encoded UL31 and UL34 proteins that form the heterodimeric nuclear egress complex (NEC). The NEC has an intrinsic ability to deform and bud membranes by forming a hexagonal membrane-bound scaffold5. UL31 and UL34 are essential for nuclear egress across Orthoherpesviridae6,7,8,9,10,11,12, and their homologs are found in all family members4. By contrast, proteins that facilitate the fusion stage have not yet been identified. Viral entry glycoproteins gB and gH have been proposed to mediate the fusion stage in HSV-1, but their individual knockouts have mild, if any, phenotypes in HSV-113 and the closely related pseudorabies virus14.

This raised the possibility that herpesviruses might use the host fusion machinery during the fusion stage. Host processes that involve membrane fusion of the nuclear envelope include the NPC insertion during interphase and nuclear budding used to export large mRNA/protein complexes or misfolded proteins [reviewed in refs. 15,16]. However, the fusogen that mediates these processes has not yet been identified. If herpesviruses hijacked this process during nuclear egress, identifying host factors involved in herpesvirus nuclear egress could, potentially, reveal the fusogen mediating fusion of the nuclear envelope.

Towards this goal, we developed a quantitative flow-cytometry-based assay to measure capsid nuclear egress in the prototypical human alphaherpesvirus 1 (herpes simplex virus 1 or HSV-1) and used it in conjunction with a whole-genome CRISPR-Cas9 screen. The top hit in our screen was CLCC1, a gene product previously proposed to encode an ER chloride channel17,18. Here, we show that CLCC1 promotes the fusion stage of HSV-1 nuclear egress. CLCC1 may be broadly important for nuclear egress because its loss decreased viral titers not only in HSV-1 but also in the closely related human alphaherpesvirus 2 (herpes simplex virus 2 or HSV-2) and suid alphaherpesvirus 1 (pseudorabies virus or PRV). Intriguingly, CLCC1 homologs are encoded in the genomes of Malacoherpesviridae and Alloherpesviridae, which infect mollusks and fish, respectively. Phylogenetic and phylogenomic analyses reveal that these viral CLCC1 homologs were acquired from metazoan host genomes through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) in three separate events. This convergence of independent gene acquisition further supports the importance of CLCC1 function for herpesviral replication across the entire order Herpesvirales.

Beyond viruses, CLCC1 also appears important for nuclear envelope fusion in the host. Indeed, we found that loss of CLCC1 induced a nuclear blebbing phenotype associated with a defect in NPC insertion or nuclear export. We hypothesize that CLCC1 mediates an ancient cellular membrane fusion mechanism important for nuclear envelope morphogenesis that has been co-opted or horizontally acquired by the Herpesvirales for capsid nuclear egress. Bioinformatic analysis and structural modeling suggests that CLCC1 can interact with a target membrane, oligomerize, and undergo a conformational change that could promote membrane deformation and fusion. Our findings set a stage for the mechanistic exploration of CLCC1-mediated membrane fusion in health and disease.

Results

A custom flow-cytometry-based assay quantifies HSV-1 nuclear egress

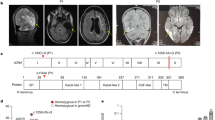

Herpesvirus nuclear egress is typically quantified by manual capsid counting in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of infected cells. To increase the scale and throughput, we developed a flow-cytometry-based nuclear egress assay. To detect cytoplasmic capsids, infected HeLa cells were first treated with digitonin to permeabilize the plasma membrane but not the nuclear envelope. Cells were then incubated with a primary antibody 8F5, which has been shown to bind the HSV-1 major capsid protein VP5 on capsids but not free VP519, and subsequently, incubated with an Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibody (Fig. 1a). To ensure that analyzed cells were infected, we used an HSV-1 F strain encoding an NLS-tdTomato transgene20. We monitored two fluorescence channels: tdTomato, for the detection of HSV-1 infection, and Alexa488, for the detection of capsids. Detection of double-positive tdTomato + /Alexa488+ cells served as a readout for nuclear egress. We also generated a HSV-1 mutant lacking UL34 gene, which encodes an NEC component, to be used as a negative control because loss of UL34 causes a large defect in nuclear egress9. In the WT HSV-1, ~90% cells were tdTomato+ /Alexa488+ whereas in the ΔUL34 mutant, only ~6% of cells were tdTomato+ /Alexa488+ (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. S1a). To rule out defects in capsid production, infected cells were treated with Triton X-100 to permeabilize both the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope. In the fully permeabilized WT or ΔUL34 HSV-1, ~95% or ~73% of cells are tdTomato+ /Alexa488+ (Supplementary Fig. S1a). The phenotypes observed by flow cytometry were also confirmed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. S1b).

a Schematic of the nuclear egress assay. HeLa cells are infected with HSV-1 encoding tdTomato, permeabilized, and stained with the capsid-specific primary antibody and Alexa-488-conjugated secondary antibody. Infected cells with nuclear egress have capsids in the cytoplasm are stained, whereas cells without nuclear egress will lack staining due to capsid retention in the nucleus. b Flow cytometry readouts from the validation of the nuclear egress assay. HeLa cells were infected with HSV-1 F GS3217-d34 (dUL34 HSV-1) or HSV-1 F GS3217 (WT HSV-1). Uninfected HeLa cells served as a control. The y-axis (red, tdTomato) indicates HSV-1 infection, and the x-axis (green, Alexa-488) indicates the presence of capsids. Each image is representative of three replicates. c Immunofluorescence images from validation of the nuclear egress assay. Experimental conditions are the same as in (b). Scale bar = 10 µm. Each image is representative of three biological replicates. d Schematic of the genome-wide CRISPR screen. HeLa-Cas9 cells were transduced with Gattinara library lentivirus, cells were subsequently infected with HSV-1 F GS3217, stained and sorted by flow cytometry. e Representative flow data from the genome-wide CRISPR screen. Graph is from one of the six sorting rounds, where two independently generated Gattinara library HeLa cells were each infected with HSV-1 on three independent occasions. f Volcano plot of the genome-wide CRISPR screen. Each dot represents a specific gene. The x-axis shows the average log2 fold change (FC) of the specific gene. The y-axis shows the significance score plotted as -log(p-value). The dotted line at y = 3 is the threshold for p-value = 0.001 [−log10(p-value) = 3). The dashed line at y = 1.3 is the threshold for p-value = 0.05 [−log10(p-value) = 1.3). Red: top hit, CLCC1. Green: genes known to contribute to HSV-1 nuclear egress. High-confidence hit, EMD, is labeled. Light gray: non-site targeting sgRNAs. Dark gray: intergenic site targeting sgRNAs. The statistics were calculated using two-side paired t-text without correction for multiple comparisons and converted to the −log10(p-value). Source data are provided in Source Data 1–4 and Supplementary Data 1. Figure 1a: Schematic of the nuclear egress assay. Created in BioRender. Dai, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/s1ge6ad. Figure 1d: Schematic of the genome-wide CRISPR screen. Created in BioRender. Dai, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/99sttvr.

CRISPR-Cas9 screens of nuclear egress identify CLCC1 as a top positive regulator

To identify host factors involved in nuclear egress, we performed a CRISPR-Cas9 screen in HeLa cells. A Cas9-expressing HeLa cell line was transduced with the Gattinara sgRNA library composed of ~40,000 sgRNAs targeting the whole human genome (two sgRNAs/gene) (Fig. 1d). Transduced cells were infected with WT HSV-1, fixed, partially permeabilized, stained, and sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Fig. 1d). The tdTomato + /Alexa488- cell population (no nuclear egress) was analyzed for potential hits, whereas the tdTomato + /Alexa488+ cell population (nuclear egress) was used as a control (Fig. 1e).

Genomic DNA was isolated from the sorted populations and sequenced. Two independent Gattinara library transductions were done (2 biological replicates), each with three independent HSV-1 infections (3 technical replicates). The log-normal reads from the screen were combined based on the gene name and visualized as a volcano plot (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Data 1). The screen yielded 41 candidate regulators with a p-value < 0.001 [−log10(p-value) >3], including 9 positive regulators (decreased nuclear egress when the gene is depleted) and 32 negative regulators (increased nuclear egress when the gene is depleted) (Table S1). Most of these have no known roles in nuclear egress and do not localize to nuclear envelope, suggesting that they could represent false positives. However, one negative regulator, EMD (Fig. 1f, Table S1), encodes emerin, a component of the nuclear lamina that helps maintain nuclear envelope integrity. Phosphorylation of emerin during HSV-1 infection promotes lamina disruption, which facilitates capsid nuclear egress21,22. Additionally, five other host factors reported to contribute to HSV-1 nuclear egress [reviewed in ref. 23], LMNA, SLC35E124, CHMP4C, PRKCB, and PRKD2, were among candidate genes with p-values < 0. 05 [3 > −log10(p-value) > 1.3] (Table S2). Their presence among the screen hits supports the validity of our screening approach. The rest of the host factors reported to contribute to HSV-1 nuclear egress [25 and reviewed in ref. 23] had p-values > 0.05 [−log10(p-value) <1.3] as not significant hits in the screen. (Table S2 and Supplementary Data 1). To better analyze the hits, we also generated a network map from the top 414 genes with p-values < 0.01 [−log10(p-value) > 2] (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Pathway analysis identified metabolism of RNA as the most enriched pathway, with RNA splicing and pre-mRNA processing also enriched (Supplementary Fig. S2b). These processes are not directly linked to nuclear egress, however. Instead, disruption of RNA synthesis may generally influence viral replication.

Next, we focused on the strongest hit by far, CLIC-like 1 chloride channel (CLCC1) gene, which was present in all the replicates and with both sgRNAs (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). CLCC1 is an ER channel17,18 proposed to mediate chloride efflux from the ER to neutralize charge imbalance caused by calcium release17. It plays a role in the ER stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR)17,26,27. In humans, mutations in the CLCC1 gene are associated with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)17 and autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa28. However, with no evidence connecting it to the nuclear envelope or vesicular trafficking, it was unclear how CLCC1 could be involved in nuclear egress.

Loss of CLCC1 causes a defect in HSV-1 capsid nuclear egress

To validate the defect in nuclear egress due to CLCC1 depletion, we generated CLCC1 knockouts in HeLa, Hep2, and HFF cell lines with CLCC1-targeting sgRNAs from both the original Gattinara library (sgRNA CLCC1-1) and a different Brunello library (sgRNAs CLCC1-3 and CLCC1-6) (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. S3a). As a negative control, a HeLa cell line was transduced with an sgRNA targeting an intergenic region (Int_bulk) (Fig. 2a). All CLCC1-KO cell lines had defects in HSV-1 nuclear egress as measured by the flow cytometry assay (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. S3b) and confirmed by confocal microscopy in CLCC1-KO HeLa cells (Supplementary Fig. S3c).

a Western blots confirm CLCC1 depletion in CLCC1-KO (cko3 and cko6) and single-cell CLCC1-KO (cko3_2, cko3_4, cko6_1, and cko6_2) cell lines. Representative images are from one of at least two biological replicates, panels from the same gel were grouped together, actin served as a loading control. b Nuclear egress defect in CLCC1-KO (cko3, cko3_2, cko3_4, cko6, cko6_1 and cko6_2) cell lines infected with HSV-1 F GS3217, normalized to HeLa cells. HeLa cells infected with HSV-1 F GS3217-d34 served as a positive control. Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with a multiple comparison to the HeLa group, n = 3. Bars represent mean values, and the error bars represent SEM. ****: p < 0.0001; NS: not significant, p > 0.05 (p values from left to right: 0.9991, 0.9879, 0.999). c Western blots confirm CLCC1 expression in CLCC1 rescue cell lines. CLCC1 was expressed exogenously in single-cell CLCC1-KO cell lines under control of EF1a (cko3_4_EF1a and cko6_1_EF1a), hPGK1 (cko3_4_hPGK1, cko6_1_hPGK1, and their respective single clones cko3_4_R_1 and cko6_1_R_1). CRISPR-resistant (CR) CLCC1 was expressed under control of hPGK1 (cko3_4_CR and cko6_1_CR). Representative images are from at least two biological replicates, panels from the same gel were grouped together, actin served as a loading control. d Nuclear egress rescue in CLCC1 rescue cell lines infected with HSV-1 F GS3217, normalized to Int_4 cells. Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA analysis with a multiple comparison to Int_4, cko3_4 or to cko6_1, n = 3. Bars represent mean values, and error bars represent SEM. ****: p < 0.0001; ***: p < 0.001 (p value 0.0008); *: p < 0.05 (p value 0.0171); NS: not significant, p > 0.05 (p values from left to right 0.0706, 0.9981, 0.9807, 0.4136, 0.1496). e Multiple-step growth curves of single-clone CLCC1-KO and single-clone CLCC1 rescue cell lines infected with HSV-1 F GS3217, HSV-2 186, or PRV GS7741. Plaque assay was performed in Vero cells. The y-intercept is set to 100 at time 0. Each symbol represents the average of three biological replicates. Error bars represent SEM. Uncropped blots and source data for graphs are provided in Source Data 9.

From the heterogenous (bulk) pools of CLCC1-KO HeLa cell lines (cko3_bulk and cko6_bulk), four single-cell clones (cko3_2, cko3_4, cko6_1, and cko6_2) were selected (Fig. 2a). Two single-cell clones (Int_3 and Int_4) were also selected from the control Int_bulk cell line (Fig. 2a). The single-cell CLCC1-KO cell lines had even stronger defects in HSV-1 nuclear egress than the bulk cell lines (Fig. 2b). Three single-cell CLCC1-KO clones (cko3_4, cko6_1, and cko6_2) showed the strongest defects in nuclear egress, <20%, which was comparable to that of the control UL34-null HSV-1 mutant, whereas cko3_2 had a more modest defect, ~40% (Fig. 2b). Two of the single-cell CLCC1-KO cell lines, cko3_4 and cko6_1, were chosen for further characterization, with Int_4 chosen as a negative control. These data validated CLCC1 as a host gene required for efficient HSV-1 capsid nuclear egress across several cell lines.

The defects in nuclear egress due to loss of CLCC1 are rescued by expression of CLCC1 in trans

To confirm that the defects in nuclear egress and viral replication in CLCC1-KO cell lines were specific to the loss of CLCC1, we performed a CLCC1-KO rescue experiment by expressing CLCC1 in trans. We tested three in-trans stable-expression strategies. First, we expressed WT CLCC1 under the control of a strong EF1α promoter. This led to very high CLCC1 protein levels (Fig. 2c) but poorly rescued the nuclear egress defect (~15–38%) in CLCC1-KO cell lines (cko3_4_EF1α, cko6_1_EF1α) (Fig. 2d) and even reduced HSV-1 nuclear egress in the control cell line expressing endogenous CLCC1 (Int_4_EF1α) (~50%) (Fig. 2d). This expression strategy was not used further.

We then expressed WT CLCC1 under the control of a weaker hPGK1 promoter. In this case, CLCC1 protein was undetectable by Western Blot (Fig. 2c), at least in bulk, presumably due to degradation by the active CRISPR/Cas9. Nonetheless, even at levels below detection, this expression strategy partially rescued nuclear egress (~30–60%) in CLCC1-KO cell lines (cko3_4_hPGK1, cko6_1_hPGK1) (Fig. 2d) and had no deleterious effect on nuclear egress in the Int_4 cell line (Int_4_hPGK1) (Fig. 2d). Two single-cell clones isolated from the bulk CLCC1 hPGK1 rescue (R) pools (cko3_4_R_1 and cko6_1_R_1) had CLCC1 expressed at protein levels close to endogenous (Fig. 2c)—possibly, due to the loss of Cas9 activity or a functional repair after the Cas9 cleavage in individual cells—and fully rescued the CLCC1-KO nuclear egress defect (> 90%) (Fig. 2d). These single-cell CLCC1 rescue clones were used in subsequent validation experiments (except for the mutant rescue experiment) because they produced CLCC1 at the endogenous levels and fully rescued CLCC1-KO.

Finally, we also expressed a CRISPR-resistant (CR) CLCC1, which contains silent mutations designed to destroy the target sites for 6 CLCC1 sgRNAs (2 from Gattinara and 4 from Brunello libraries), under the control of the hPGK1 promoter (cko3_4_CR and cko6_1_CR). Although CRISPR-resistant CLCC1 was expressed at above-the-endogenous protein levels (Fig. 2c), it fully rescued the CLCC1-KO nuclear egress defect in bulk (> 90%) (Fig. 2d). This rescue strategy using CRISPR-resistant CLCC1 was used in the subsequent mutant rescue experiments, which were done in bulk.

Loss of CLCC1 causes defects in viral replication in HSV-1 and two related Alphaherpesvirinae that are rescued by expression of CLCC1 in trans

To examine the defects in viral replication due to loss of CLCC1, we measured HSV-1 titers using multiple-step growth curves. HSV-1 replication in either cko3_4 or cko6_1 cell lines resulted in a ~1000-fold drop in titer (Fig. 2e). The strong defect in virion production due to the loss of CLCC1 is consistent with the strong defect in nuclear egress, which is an essential step in virion morphogenesis. To determine if CLCC1 were important for replication in other members of the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily of the family Orthoherpesviridae, we tested HSV-2 and pseudorabies virus (PRV). Replication of HSV-2 and PRV in both CLCC1-KO cell lines resulted in ~1000-fold drop in titer (Fig. 2e). Viral titers of HSV-1, HSV-2, and PRV were rescued nearly to the WT levels in these single-cell CLCC1 rescue cell lines (Fig. 2e). These results confirmed the importance of CLCC1 in viral replication across the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily.

The CLCC1 role in nuclear egress is unrelated to ER stress and UPR

CLCC1 has been linked to ER stress and an unfolded protein response (UPR)17,26,27. To evaluate the role of ER stress in the HSV-1 nuclear egress, we measured levels of BiP, a mediator of UPR and an ER stress marker29. In uninfected HeLa or single-cell CLCC1-KO (cko6_1) cell lines, BiP levels were higher upon treatment with a chemical ER stress inducer, dithiothreitol (DTT) (Supplementary Fig. S4a). CLCC1-KO cell lines might also be more sensitive to DTT than HeLa cells, judging by their slightly lower viability (Supplementary Fig. S4b). However, during HSV-1 infection, BiP (an ER stress marker) levels were similarly low in the presence or absence of DTT, in both HeLa and CLCC1-KO cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S4a). HSV-1 is known to suppress UPR30,31. Importantly, HSV-1 nuclear egress was not inhibited by DTT in HeLa cells (Supplementary Fig. S4c). Therefore, neither ER stress nor UPR could explain the HSV-1 nuclear egress defect due to the loss of CLCC1.

PEVs accumulate in the perinuclear space of HSV-1-infected cells in the absence of CLCC1

To determine the stage in nuclear egress blocked in the absence of CLCC1, we examined single-clone CLCC1-KO (cko3_4 and cko6_1) and CLCC1 rescue (cko6_1_R_1) cell lines infected with HSV-1 by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In the control HSV-1-infected Int_4 cell line, single PEVs were observed (Fig. 3c). However, in the HSV-1-infected CLCC1-KO cell lines, multiple PEVs accumulated in the PNS (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Fig. S5), suggesting a defect at the fusion stage of nuclear egress, also known as de-envelopment. Expression of CLCC1 in trans in the CLCC1 rescue cell line rescued the single-PEV phenotype (Fig. 3d). PEVs were quantified in Fig. 3e. We hypothesize that the loss of CLCC1 blocks the fusion stage of capsid nuclear egress.

a–d TEM images of cell lines infected with HSV-1. a Int_4, b single-clone CLCC1-KO (cko3_4), c single-clone CLCC1-KO (cko6_1), and d single-clone CLCC1 rescue (cko6_1_R_1). Scale bar = 500 nm. Up-close views of accumulated PEVs are shown in insets (a1, a2, b1, and b2), scale bar = 100 nm. Representative images are from one of at least two individual experiments. Additional images are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. e Quantification of PEVs in infected cells. Data were combined from at least two biological replicates. Each dot represents the number of events in a single cell. Bars represent mean values, and error bars represent SEM. ****: p < 0.0001; NS: not significant, p > 0.05 (p value 0.9987). Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons to Int_4. n = 10 for Int_4, cko3_4 and cko6_1, and n = 5 for cko6_1_R_1, where n is the cell number. f TEM image of a HeLa cell infected with US3 K220A HSV-1, scale bar = 500 nm. Up-close views of accumulated PEVs are shown in insets (f1 and f2), scale bar = 100 nm. The image is representative of two individual experiments. Source data for graphs are provided in Source Data 9.

PEV accumulation has been previously observed in cells infected with HSV-1 or PRV mutants with an inactive US3 kinase32,33,34,35,36,37. To compare the two phenotypes, we imaged HeLa cells infected with HSV-1 US3-K220A (inactive kinase) mutant (Fig. 3f). Whereas in HSV-1-infected CLCC1-KO cell lines, PEV-containing areas of PNS protrude into the cytoplasm (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Fig. S5), in cells infected with the HSV-1 US3-K220A mutant, PEVs instead accumulate in “pockets” that protrude into the nucleus (Fig. 3f). These phenotypic differences could be due to defects at distinct stages in nuclear egress. US3 phosphorylates UL3138,39, a component of the NEC, which deforms and buds INM around the capsid during nuclear egress. Phosphorylation of UL31 has been proposed to inhibit the membrane-budding activity of the NEC40. PEV accumulation in the absence of a functional US3 kinase suggests that PEVs accumulate whenever US3 cannot phosphorylate UL31. While this has been attributed to the importance of UL31 phosphorylation during de-envelopment39, PEV accumulation could be alternatively caused by PEV overproduction due to disregulated, excessive capsid budding.

Loss of CLCC1 in uninfected cells causes formation of nuclear blebs, possibly due to a defect in NPC insertion

Upon examining the uninfected CLCC1-KO cell lines (cko3_4 and cko6_1) by TEM, we observed spherical vesicles in the PNS, or nuclear blebs (NBs) (Fig. 4a, b, Supplementary Fig. S6). Although empty vesicles were sometimes also observed in HSV-1-infected cells (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Fig. S5), the NBs in the uninfected CLCC1-KO cell lines had a distinct appearance. They did not cluster but were, instead, distributed along the nuclear envelope, in a beads-on-a-string manner (Fig. 4a, b, Supplementary Fig. S6). Further, the NBs did not appear empty and ranged in size from ~80 to ~260 nm. No NBs were found in the control Int_4 (Fig. 4c) and CLCC1 rescue cell lines (cko3_4_R_1 and cko6_1_R_1) (Fig. 4d). NBs were quantified in Fig. 4e.

a–d TEM images of uninfected cell lines. a single-clone CLCC1-KO (cko3_4), b single-clone CLCC1-KO (cko6_1), c Int_4, d single-clone CLCC1 rescue (cko6_1_R_1). Scale bar = 500 nm. In (a) and (b), NBs are indicated with green arrowheads. Close-up views NBs are shown in insets (c1, c2, d1, and d2), scale bar = 100 nm. Necks connecting some NBs with the INM are indicated with white arrowheads. Images are representative of at least one individual experiments. Additional images are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6. e Quantification of NBs in uninfected cells. Data were combined from two biological replicates. Each dot represents the number of events in a single cell. Bars represent mean values, and the error bars represent SEM. ***: p < 0.001 (p value 0.0001); NS: not significant, p > 0.05 (p values from left to right 0.1653 and >0.9999). Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA, with multiple comparisons, n = 5 for Int_4 and cko6_1_R_1, n = 4 for cko3_4 and cko6_1. Source data for graphs are provided in Source Data 9.

Up-close examination revealed that some NBs had necks and appeared connected to the INM (Fig. 4a1, b2). Morphologically similar NBs have been observed in cells depleted of the Torsin ATPase or its cofactors LAP1 and LULL141,42. This phenotype was attributed to a defect in NPC insertion during interphase caused by a defect in the fusion of the inner and outer nuclear membranes41. Myeloid leukemia factor 2 (MLF2) has been identified as a component of the NB lumen41. To test for the presence of MLF2 in the blebs formed in CLCC1-KO cell lines, we overexpressed an MLF2-GFP reporter construct. MLF2 localized to puncta along the nuclear envelope in CLCC1-KO cell lines (cko3_4 and cko6_1) but not in the control HeLa and Int_4 or the CLCC1 rescue cell lines (cko3_4_R_1 and cko6_1_R_1) (Fig. 5). Thus, loss of CLCC1 recapitulated the nuclear blebbing phenotype previously observed in cells depleted of Torsin and attributed to a defect in NPC insertion. We hypothesize that CLCC1 may promote not only HSV-1 nuclear egress but also, potentially, nuclear pore biogenesis.

Confocal images of control HeLa, Int_4, single-clone CLCC1-KO (cko3_4 and cko6_1), and single-clone CLCC1 rescue (cko3_4_R_1 and cko6_1_R_1) cell lines overexpressing MLF2-GFP (green). Nuclei stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 10 mm. Close-up views of the boxed regions are shown on the right. Images are representative of two biological replicates.

Viral CLCC1 homologs share similar sequence and structure with cellular CLCC1 counterparts

There are >900 CLCC1 homologs across the animal kingdom. Unexpectedly, we discovered viral homologs of CLCC1 (vCLCC1) encoded in the genomes of several members of the Malacoherpesviridae, including Ostreid herpesvirus 1 (OsHV-1), Malaco herpesvirus 1 (MLHV1), Abalone herpesvirus (AbHV-1), and Chlamys acute necrobiotic virus (CanV); and several members of the Alloherpesviridae, including Ictalurid herpesvirus 1 (IcHV-1), Black bullhead herpesvirus (BbHV), Silurid herpesvirus 1 (SHV-1), and Anguillid herpesvirus 1 (AngHV-1) (Figs. 6a,b and 7a, b, Supplementary Data 2).

a Domain architecture of three cCLCC1 homologs [human, channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus (IctaPu), pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas (CraGi)] and two vCLCC1 homologs (IcHV1 ORF16a and OsHV-1 ORF57). Structural elements and domains were assigned based on structural predictions and secondary structure assignments and are colored as follows: signal sequence (SS, gray), transmembrane helix 1 (TM1, blue), TM2 (deep teal), fist domain (FD, magenta), amphipathic helix (AH, orange), and TM3 (teal). S-S = predicted disulfide bond (purple). Transmembrane domains were predicted by TMHMM 2.0 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/). b Sequence alignment of human (Homo), mouse (MusMus), Zebrafish (DanRe), African clawed frog (XenoLa), Pacific oyster (CraGi), Blacklip abalone (HaliRu), Channel catfish (IctaPu), American eel (AngRo) CLCC1 and the viral homologs OsHV1 ORF57, AbHV1 ORF90, IcHV1 ORF16A, AngHV1 ORF112 in the conserved core region (compared to human 117-348). Alignment was generated using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/clustalo) and visualized using Espript 3.0 (https://espript.ibcp.fr). Similar residues are colored yellow and conserved residue are colored red. Secondary structure elements and domains were assigned based on Alphafold 3.0 and TMHMM2.0 predictions. c Ribbon diagrams of AlphaFold3 models of human CLCC1, IctaPu CLCC1, CraGi CLCC1, IcHV1 ORF16a, and OsHV-1 ORF57. Structural models were generated using the AlphaFold 3.0 online server (https://alphafoldserver.com/) and displayed using Pymol. Structural elements and domains are colored as in (A) and labeled. d An AlphaFold model of human CLCC1 cartoon representation. Structural elements and domains are colored as in (c) and labeled. Residues 365-539 were unstructured and excluded for clarity. 10 residues that are invariant across 8 representative animal and 4 herpesviral homologs in b are shown in sphere representation and colored in red, except cysteines, which are shown in purple. Figure 6c: Ribbon diagrams of AlphaFold3 models of human CLCC1, IctaPuCLCC1, CraGi CLCC1, IcHV1 ORF16a, and OsHV-1 ORF57. Created in BioRender. Dai, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/bies72m.

a Phylogenomic distribution of CLCC1 homologs across Herpesvirales. Filled boxes indicate presence of a protein in the indicated viral species. The phylogenetic tree of herpesviruses was generated based on DNA polymerase proteins found in all herpesvirus genomes (see also Supplementary Fig. S9) and is consistent with previously a published herpesvirus phylogeny74. Unlike DNA polymerase, we only observe CLCC1 homologs in the genomes of three distinct lineages (filled blue, red, and purple boxes) of herpesviruses, consistent with multiple separate host-to-virus HGT events. b Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of metazoan and viral CLCC1 protein homologs. Bootstrap branch support values for monophyletic viral CLCC1 clades are indicated by asterisks (** = 100% support). Viral CLCC1 sequences are depicted as shaded triangles using colors as in (a). Abbreviated viral species names of the vCLCC1 clades are adjacent to the pertinent clade and colored to match colors in (a). The remaining sequences are from metazoan species. Complete tree, with all branch supports, is found in Supplementary Data 3. c Phylogenetic trees of metazoan and viral CLCC1 protein homologs were generated with three diverse tree building software (IQ-TREE, FastTree, and RAxML) as described in the methods. For each analysis, branch support values for monophyletic viral CLCC1 clades are shown (coloring of rows matches coloring for clades depicted in Fig. 7a, b). For IQ-TREE and RAxML, support values are derived from bootstrap replicates, will a maximum value of 100. For FastTree, support values are derived from the Shimodaira–Hasegawa (SH) test, with a maximum value of 1. See Supplementary Data 3 for complete phylogenetic trees with branch supports. The last row indicates the number of HGT events as determined by the distinct grouping of vCLCC1 homologs with cCLCC1 homologs with bootstrap support values of >80 and SH values > 0.8 in all tests rather than grouping to each other. d Consensus sequence from 897 cellular CLCC1 (cCLCC1) homologs from diverse metazoans (top) and of 12 viral CLCC1 (vCLCC1) homologs (bottom). Shown is part of the fist domain (FD, magenta as in (B), highlighting the predicted disulfide bond (S-S, purple) and demonstrating conserved residues amongst the cCLCC1 and vCLCC1 proteins.

The vCLCC1s are shorter than cellular CLCC1s (cCLCC1) by ~150 amino acid residues—due to shorter N and C termini—but share a highly conserved ~180 amino acid “core” region (Fig. 6a, b). AlphaFold43 predicts similar structural folds for the cores of cCLCC1 homologs [e.g., Homo sapiens (human) CLCC1, Ictalurus punctatus (channel catfish) CLCC1, and Crassostrea gigas (pacific oyster) CLCC1] and vCLCC1 homologs from Alloherpesviridae (e.g., IcHV1 ORF16a) and Malacoherpesviridae (e.g., OsHV-1 ORF57) (Fig. 6c) that do not resemble any known structures44. A prior study suggested that the N and C termini of CLCC1 face the ER lumen and the cytoplasm, respectively17. The AlphaFold-predicted core fold consists of three transmembrane (TM) helices, TM1-3 (Fig. 6c, d). TM1 and TM2 are adjacent and form an antiparallel hairpin, whereas TM3 is separated and tilted in respect to TM1/TM2 (Fig. 6c, d). TM2 is followed by an ER-facing fist-shaped domain (FD) composed of 4 helices of variable length, FDh1-FDh4 (Fig. 6c, d). Two highly conserved cysteines, C254 and C279 (Fig. 6b), are predicted to form a disulfide that likely stabilizes the FD (Fig. 6d). Of note, helix FDh2 (the “knuckle” part of the fist) is amphipathic and juts outward from the membrane (Fig. 6c, d). The FD is followed by a long, bow-shaped amphipathic helix (AH) flanked by highly conserved prolines (Fig. 6c, d). Another highly conserved proline in the middle of AH gives it its bow shape (Fig. 6d). TM1/TM2, AH, and TM3 form a triangular chair shape, with AH positioned to interact peripherally with the membrane (Fig. 6c).

The TM1-TM2-FD-AH-TM3 core is conserved in sequence (Fig. 6a, b) and predicted secondary and tertiary structure (Fig. 6b, c) across cCLCC1 and vCLCC1 homologs. Moreover, it contains several highly conserved residues in TM2, FD, and AH, including 4 prolines and 2 cysteines (Fig. 6b, d). High sequence conservation suggests that the TM2-FD-AH is an essential, structurally conserved element in CLCC1.

Members of the order Herpesvirales have acquired host CLCC1 genes on three separate occasions

Based on the sequence and structural similarity of vCLCC1 homologs with cCLCC1 homologs, we next wished to determine the evolutionary origin of vCLCC1 homologs. Specifically, we considered that vCLCC1 homologs may have been co-opted by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from viral hosts, as this is a known mechanism by which viruses can acquire new genetic material and functional proteins45,46,47. To begin, we assessed the phylogenomic distribution of vCLCC1 homolog proteins in the order Herpesvirales. We only identified vCLCC1 homologs in the Alloherpesviridae and Malacoherpesviridae families, but not in the Orthoherpesviridae. Interestingly, we only identified vCLCC1 homologs in certain members of these viral families, even though we easily identified viral DNA polymerase proteins from a wide diversity of Alloherpesviridae and Malacoherpesviridae (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Fig. S7, Supplementary Data 2). These phylogenomic observations, which revealed that only certain subsets of related Herpesvirales encode vCLCC1s, whereas other Herpesvirales lack obvious vCLCC1 homologs, provided initial evidence suggesting that these homologs may have arisen by multiple HGT events from host genomes rather than vertical inheritance from a common ancestor to all of the analyzed Herpesvirales.

We next performed phylogenetic analyses with vCLCC1s and cCLCC1 protein homologs from diverse metazoan species. These analyses revealed the presence of three distinct, well-supported clades of vCLCC1 proteins corresponding to homologs from Malacoherpesviridae, homologs from AngHV-1 (within the Alloherpesviridae), and the remaining vCLCC1 homologs within the Alloherpesviridae (Fig. 7b, Supplementary Data 2). Importantly, each of these phylogenetically and phylogenomically distinct clades of vCLCC1 homologs groups more closely with cCLCC1 homologs than with each other, indicating that each viral clade of vCLCC1s arose by HGT from an independent cCLCC1 source. Together, these data indicate that there were three distinct HGT events that gave rise to three phylogenetically distinct clades of vCLCC1 homologs. Moreover, we observed that the two clades of Alloherpesviridae vCLCC1 homologs, which are only found in members of fish-infecting members of this viral family, phylogenetically group with fish cCLCC1 proteins, consistent with a model in which vCLCC1 homologs were acquired by HGT from the hosts that these viruses infect, although the exact host is difficult to resolve with confidence (Fig. 7b, Supplementary Fig. S8). Similarly, the Malacoherpesviridae vCLCC1 homologs group with invertebrate cCLCC1 proteins (Fig. 7b, Supplementary Fig. S8). Again, the exact host species that gave rise to the vCLCC1 homologs is difficult to resolve, which is commonly seen with ancient HGT events. To confirm the robustness of our inferences of three different HGT events, we performed analyses using three different maximum-likelihood tree building algorithms, IQ-TREE, RAxML, and FastTree. In all cases, we observe three distinct clades of proteins that each group more closely with cCLCC1 homologs than other vCLCC1 homologs, as well as consistent grouping of Alloherpesviridae vCLCC1 homologs with fish cCLCC1s and Malacoherpesviridae vCLCC1 homologs with invertebrate cCLCC1s (Fig. 7c, Supplementary Fig. S8). Taken together, our phylogenetic and phylogenomic analyses indicate that vCLCC1 homologs have been recurrently acquired from host organisms by HGT.

Finally, we used these expanded groups of vCLCC1 and cCLCC1 homologs to determine the degree to which critical residues within the proteins were conserved. Consistent with our initial alignments (Fig. 6b), we find that critical disulfide-forming cysteines and several residues in FDh3 and FDh4 are well conserved within the >900 cCLCC1 and >10 vCLCC1 homologs (Fig. 7d). These data further support the inference that vCLCC1 homologs were acquired from genes encoding functional cCLCC1 proteins and have retained critical structural and functional residues.

The CLCC1 channel activity does not appear important for HSV-1 nuclear egress

To help define the mechanistic role of CLCC1 in HSV-1 nuclear egress, we asked if its reported ion channel activity were important for nuclear egress. A prior study on human and mouse CLCC117 reported several mutations that altered its conductivity in vitro and caused changes in ER morphology and ER stress in vivo (Fig. 8a). D25E and D181R, which target a putative Ca2+-binding site, made CLCC1 channel conductivity in vitro less sensitive to Ca2+ inhibition and reduced Ca2+ binding in vitro17. D25E is also associated with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa28. S263R and W267R reduced channel conductivity in vitro and are associated with ALS17. K298E reduced channel potentiation by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2)17. We generated these mutants (Fig. 8a) and tested their ability to rescue the nuclear egress defect caused by the loss of CLCC1. As controls, we also generated double mutants D152R/D153R and E175R/D176R that did not affect channel conductivity in vitro17 (Fig. 8a). All mutations were introduced into the CRISPR-resistant gene variant of CLCC1 (CLCC1-CR) (Fig. 2c, d). To perform the CLCC1 rescue experiment, WT CLCC1 or CLCC1 mutants were expressed in trans in the CLCC1-KO (cko3_4, cko6_1), HeLa, or control cell line (Int_4) under the control of the hPGK1 promoter. All CLCC1 mutants were expressed at higher than the endogenous levels (Supplementary Fig. S9).

a A ribbon diagram of an AlphaFold model of human CLCC1. Structural elements and domains are colored as in Fig. 6d and labeled. Mutated residues are shown in sphere representation and are colored as in the right panel. Functions of mutated residues (if known) are also listed in the right panel. Residues 365-539 were removed for clarity. Nuclear egress assay of CLCC1-KO b or control c cells mock-transfected (M), transfected with CRISPR-resistant CLCC1 (CR), or transfected with CLCC1 mutants listed in a in the CRISPR-resistant background (D25E, D25E/D181R, D152R/D153R, E175R/D176R, W209A, S224A, C254A, C254A/C279A, S267R, W267R, D277R, Y282A, K298E), and then infected with HSV-1 F GS3217. Nuclear egress was normalized to the average percent nuclear egress in Int_4 mock condition. Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA, with multiple comparisons to the mock for each cell line. Bars represent mean values, and the error bars represent SEM. Experiments were done in triplicate except for HeLa 254 and cko3_4 254, which were done in duplicate. ****: p < 0.0001; ***: p < 0.001 (p values from left to right 0.0004, 0.0004, 0.0002, and 0.0002); *: p < 0.05 (p values from left to right 0.0172, 0.0199 for (b), 0.0387, 0.0121 for (c); NS: not significant, p > 0.05 (p values from left to right 0.1925, 0.9945, 0.9959, 0.7840, 0.7926, 0.8281, >0.9999, 0.2684, >0.9999, 0.2721, >0.9999, 0.1257, 0.6708 for (b), 0.6872, >0.9999, 0.9031, >0.9999, >0.9999, 0.8217, >0.9999, 0.9007, >0.9999, 0.9973, >0.9999, 0.9972, >0.9999, 0.9999, 0.9980, 0.9228, >0.9999, 0.9760, 0.8607, >0.9999, >0.9999, >0.9999, 0.8809, 0.9994, 0.9484, >0.9999 for (c). The color scheme is as in a. Source data for graphs are provided in Source Data 9.

Expression of CLCC1 mutants that reduce chloride channel conductivity in vitro (S263R and W267R) or reduce Ca2+ binding (D181R, D25E/D181R) rescued the HSV-1 nuclear egress defect either fully or partially in both CLCC1-KO cell lines (Fig. 8b). Therefore, CLCC1 channel activity and Ca2+ binding do not appear very important for nuclear egress. By contrast, expression of the K298E mutant did not rescue the nuclear egress defect (Fig. 8b), implicating a role for K298 in nuclear egress. K298 has been postulated to interact with PIP217. Indeed, in the AlphaFold CLCC1 model, K298 is located at one end of the long amphipathic helix AH that is optimally positioned to interact with the CLCC1-containing membrane (Figs. 6c and 8a). Unexpectedly, control mutants had opposite rescue effects. Whereas E175R/D176R rescued the nuclear egress defect, D152R/D153R did not (Fig. 8b). Collectively, the reported channel conductivity phenotypes of the CLCC1 mutants were discordant with their ability to rescue the HSV-1 nuclear egress defect in CLCC1-KO cell lines. Therefore, the channel function of CLCC1 does not appear important for nuclear egress.

Highly conserved residues in CLCC1 are important for HSV-1 nuclear egress

To probe the roles of residues that are highly conserved across cCLCC1 and vCLCC1 homologs (Figs. 6b, d and 7d), we generated a panel of mutants targeting highly conserved residues in TM2 (W209A, S224A) or in the ER-facing FD (C254A, C254A/C279A, D277R, and Y282A) (Fig. 8a). All CLCC1 mutants were expressed at higher than the endogenous levels (Supplementary Fig. S9). S224A, C254A, C254A/C279A, and D277R did not rescue the nuclear egress defect (Fig. 8b), suggesting that the TM2 and FD play important roles in nuclear egress. S224 is located in the middle of TM2, whereas C254 and C279 are found in nearly all CLCC1 homologs and are predicted to form a disulfide that could stabilize the fist shape of the FD (Fig. 8a). Collectively, our mutational analysis implicates the importance of FD and TM2 in HSV-1 nuclear egress.

The nearby D277 is interesting because D277R mutant not only did not rescue the nuclear egress defect in the CLCC-KO cells (Fig. 8b) but also reduced nuclear egress in cells expressing endogenous CLCC1 (HeLa, Int_4) (Fig. 8c). The dominant-negative effect of the D277R mutation suggested that D277 could be located at the CLCC1 oligomeric interface.

Both native and recombinant CLCC1 (human or mouse) can form oligomers of unclear stoichiometry17,48,49. AlphaFold predicts that human CLCC1 forms stacks (< 10 CLCC1 copies) or rings (> 10 CLCC1 copies) (Fig. 9a, b). OsHV-1 ORF57 is likewise predicted to form oligomeric stacks or rings (Fig. 9c). In the models of human CLCC1 oligomers, D277 is predicted to form an inter-molecular salt bridge (Fig. 9d–f). Thus, we hypothesize that CLCC1 oligomerization is critical for its role in membrane fusion.

a AlphaFold models of the core region of human CLCC1 (residues 161-360, shown schematically at the top) as a hexamer (left), decamer (middle), or hexadecamer (right). Structural elements and domains are colored as in Fig. 6: TM1 (blue), TM2 (deep teal), FD (magenta), AH (orange), and TM3 (teal). b ipTM scores for AlphaFold models of the core region of human CLCC1 (residues 161-360) with number of copies from 2 to 22. c AlphaFold models of the core region of OsHV-1 ORF57 (residues 66-268, shown schematically at the top) as a hexamer (left), decamer (middle), or hexadecamer (right). Structural elements and domains are colored as in (a). d Tilted view of the AlphaFold-generated hexadecameric model of human CLCC1 (residues 161-360) in surface representation. Structural elements and domains are colored as in Fig. 6: TM1 (blue), TM2 (deep teal), FD (pink), AH (orange), and TM3 (teal). FD h2 is shown in magenta. The conserved residue D277 is shown in green. The rest of the residues are shown in wheat. e Cross-section view of the hexadecameric model in (D) in cartoon and semitransparent surface representation. Colors are as in (d). f Up-close view of D277 (green), predicted to form a salt bridge with residue K246 (white) in the adjacent protomer in the model of the human CLCC1 hexadecamer. Colors are as in (d). Source data for graphs are provided in Source Data 9.

Discussion

Nuclear egress is a non-canonical nuclear export process that is independent of the NPC. Instead, the cargo is exported by budding at the INM followed by fusion of the resulting enveloped vesicles with the ONM. For decades, this process was thought to be specific to Herpesvirales until the discovery that Drosophila uses a topologically similar mechanism to export large mRNA/protein complexes during embryonic development50,51. This non-canonical nuclear export pathway, referred to as nuclear envelope budding (NEB) among others, has also been proposed to export protein aggregates52 in response to stress53. A similar nuclear blebbing (NB) phenotype was observed in cells depleted of the Torsin ATPase41,42. This phenotype was attributed to a defect in NPC insertion during interphase nuclear pore biogenesis caused by a defect in the fusion of the INM and ONM41. The NEB/NB-like phenotypes have been reported in organisms spanning the range from yeast to sea urchins to mammals [reviewed in refs. 15,16] as early as 196554.

Despite morphological resemblance, it was unclear whether herpesvirus nuclear egress and NEB/NB in eukaryotes shared any mechanistic similarities. Their budding stages use distinct mechanisms. In herpesviruses, the budding stage of nuclear egress is mediated by the virally encoded NEC composed of UL31 and UL34 proteins [reviewed in ref. 4] that have no known homologs outside of Orthoherpesviridae. Conversely, Torsin ATPase is essential for the budding stage of the NEB in Drosophila50 and NPC insertion in mammalian cells41 yet dispensable for HSV-1 nuclear egress55. Here, we showed that loss of CLCC1, an ER protein, caused defects during capsid nuclear egress in HSV-1-infected cells and a nuclear blebbing phenotype associated with a defect in NPC morphogenesis in uninfected HeLa cells. While this manuscript was in preparation, a similar nuclear blebbing phenotype was reported in CLCC1-KO Huh7 and U-2 OS cells48. Therefore, CLCC1 participates in both capsid nuclear egress in HSV-1-infected cells and NPC morphogenesis in uninfected cells, linking nuclear envelope deformation processes in infected and uninfected cells.

The nuclear egress process is found across the entire order Herpesvirales. Our work suggests that CLCC1 is important for nuclear egress across Herpesvirales. While most of our work was done with HSV-1, we also showed that loss of CLCC1 reduced viral titers in the closely related Alphaherpesvirinae HSV-2 and PRV. Importantly, we discovered viral homologs of CLCC1 in four Malacoherpesviridae that infect mollusks (oysters, snails, abalone, and scallops) and four Alloherpesviridae that infect fish (Fig. 7a). These vCLCC1 homologs were acquired from the host genomes as a result of three separate HGT events and have retained critical residues for function. Convergence of HGT of the same host gene into three distinct viral lineages further suggests the functional importance of CLCC1 for replication in Herpesvirales. Intriguingly, these viruses have acquired and retained these vCLCC1 homologs even though their hosts encode their own cCLCC1 homologs, for example, Crassostrea gigas (pacific oyster) and Ictalurus punctatus (channel catfish), the respective hosts of OsHV-1 and IcHV-1 (Fig. 6a, b, c). vCLCC1 homologs are shorter (Fig. 6a), however, and could have distinct functions, or else the timing or expression level of vCLCC1 homologs may be more advantageous for viral replication than relying on host cCLCC1 homologs. Notably, we have not found any vCLCC1 homologs in Orthoherpesviridae, which infect mammals, birds, and reptiles. Given that we identified vCLCC1 and cCLCC1 homologs from a very wide range of viruses and metazoan species (Fig. 7b), Orthoherpesviridae may have simply not acquired these genes by HGT. Regardless, the existence of vCLCC1s suggests that CLCC1, be it encoded by the host or the virus, is important for herpesviral replication across the entire order Herpesvirales.

Our work suggests that CLCC1 promotes the fusion of INM and ONM during herpesviral and cellular processes because in its absence, viral PEVs or nuclear blebs accumulate in the PNS, seemingly unable to fuse. Purified CLCC1 has a chloride channel activity that is inhibited by calcium17. Yet, our mutational data suggest that CLCC1 chloride channel function may not be very important for HSV-1 nuclear egress. Indeed, CLCC1 does not resemble its namesakes, the chloride channel (CLC) proteins56, or any other ion channels in sequence or structural predictions. Therefore, CLCC1 may promote nuclear envelope fusion by a different mechanism.

Membrane fusion is typically mediated by membrane-anchored protein fusogens that overcome the energy barrier by bringing the apposed membranes into proximity, which causes them to fuse (reviewed in refs. 57,58). Viral and some cellular fusogens are anchored in one membrane by a transmembrane anchor and have membrane-binding spans enriched in aromatic and aliphatic residues – called fusion peptides or loops – that engage the target membrane. In contrast, heterotypic/homotypic fusion requires cellular fusogens to be present on both membranes: for example, SNAREs (reviewed in ref. 59), ER GTPase atlastin60, mitochondrial mitofusins (reviewed in ref. 61), and C. elegans EFF-1/AFF1 (reviewed in ref. 58). In all cases, fusogens undergo large conformational rearrangements.

HSV-1 gB, which functions as a membrane fusogen during entry, has been proposed to act as a fusogen during nuclear egress13. However, its knockout has a mild, if any, phenotype in HSV-113 and the closely related pseudorabies virus14. Although we have not yet formally ruled out the possibility that CLCC1 regulates the fusogenic activity of gB, given that CLCC1-KO reduces replication not only of HSV-1 but also HSV-2 and PrV, we hypothesize that CLCC1 could be directly involved in the fusion process.

CLCC1 does not resemble any known membrane fusogens in sequence or structure. Yet, our structural analysis suggests that CLCC1 may share key properties of fusogens: the ability to interact with two membranes and undergo conformational changes. First, anchored in the membrane by three predicted TMs, CLCC1 has two conserved amphipathic helices, AH and FDh2. AH is positioned to interact peripherally with the CLCC1-containing membrane of ER or ONM (Fig. 6c, d). By contrast, the FDh2 – the knuckle of the fist domain – juts outward and is positioned to interact with the opposing membrane (Fig. 6c, d). The outer face of FDh2 has several conserved aromatic residues, W260, W265, F268, and W272 (Fig. 10a), reminiscent of helical fusion peptides of class I fusogens57. Additionally, just as fusion peptides of some viral fusogens, e.g., Ebola virus GP [reviewed in ref. 57], helix FDh2 is stabilized by a disulfide57. Therefore, we hypothesize that FDh2 could engage the target membranes.

a Ribbon diagram of CLCC1 FD h2. Aromatic residues (canary yellow) and predicted disulfide bond (purple) are shown in space-filled representation. b Ribbon diagrams comparing the predicted conformations of the CLCC1 monomer and CLCC1 protomer from a hexadecameric model. c Proposed model: monomeric CLCC1 uses FD h2 to interact with the opposing membrane. Interactions with positive membrane curvature cause CLCC1 to leading to oligomerize and induce positive membrane curvature in the CLCC1 containing membrane. This membrane remodeling facilitates membrane fusion by CLCC1 itself or a partner protein. Figure not made to scale. (Left) CLCC1 is involved in the nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of herpesviral capsids (d) and nuclear cargo e, NPC formation (f), and LD biogenesis (g). (Right) Depletion of CLCC1 results in the accumulation of capsid-containing PEVs, nuclear-cargo-containing NEBs, defects in NPC formation, and retention of enlarged lipid droplets in the ER. In (c–g), different components are not shown on the same scale for better visualization. Created in BioRender. Dai, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/gpx6e6p.

Second, structural models of monomeric and oligomeric CLCC1 show conformational differences that imply the ability to manipulate membrane curvature. Whereas in monomeric CLCC1, TM1-3 and AH are positioned in a flat membrane (Figs. 6c and 10b, c), within an oligomeric assembly, their relative orientations are more compatible with a curved membrane (Figs. 9d, e and 10b, c). The relative orientation of the FDh2 also changes from flat to tilted, and in the oligomer, the FDh2 helices line up along the rim positioned to interact with a curved membrane (Figs. 9d, e and 10b, c).

Putting these together, we hypothesize that CLCC1 promotes membrane fusion by a mechanism that combines interaction with target membranes, oligomerization, and membrane deformation that leads to fusion (Fig. 10c). As an ER membrane protein, CLCC1 can access the ONM, which is contiguous with the ER. The ER-facing FDh2 helix would then face the PNS where it could interact with an INM-derived PEV (Fig. 10c). Binding of individual FDh2 helices to the curved PEV membrane could promote CLCC1 oligomerization with a concomitant conformational change that would induce positive membrane curvature in the CLCC1-containing ONM membrane (Fig. 10b, c). This would bring the membranes of the PEV and the ONM into proximity and facilitate membrane fusion by CLCC1 itself or a yet unknown partner protein (Fig. 10c). In addition to its role in membrane fusion, CLCC1 could function as a receptor for PEVs at the ONM. In this latter role, CLCC1 would act to promote fusion of PEVs with the ONM—and thus translocation of capsids into the cytoplasm—thereby avoiding a counterproductive “back-fusion” with the INM that could release capsids back into the nucleus (Fig. 10d). In the absence of CLCC1, PEVs accumulate in the PNS (Fig. 10d).

We hypothesize that CLCC1 could also facilitate nuclear export of nuclear cargo such as large mRNA/protein complexes50,51 or protein aggregates52 (Fig. 10e). While this manuscript was in preparation, a recent study48 uncovered structural similarities between CLCC1 and yeast proteins Brf1p and Brr6p, which are involved in NPC insertion. Our proposed mechanism of CLCC1 can accommodate a role in NPC formation, whereby the CLCC1 membrane interactions, oligomerization, and conformational changes would lead to the fusion of the INM and ONM (Fig. 10f). In CLCC1-KO cells, the INM still buds, but does not fuse with the ONM, disrupting pore formation (Fig. 10f). The same study47, along with another recent study48, also found that CLCC1 plays an important role in lipid droplet biogenesis. In hepatocytes lacking CLCC1, large lipid droplets accumulate in the ER lumen. This may suggest that lipid droplets form in the ER lumen, and CLCC1 is involved in their fusion with the ONM during lipid lens formation, which ultimately results in release of the lipid droplets into the cytoplasm (Fig. 10g). This process could use a mechanism similar to the one proposed here given that the ER lumen is contiguous with the perinuclear space and lipid droplets are surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer.

One limitation of this study is that the nuclear blebbing phenotype seen in uninfected CLCC1-KO cells might be not only due to disrupted NPC morphogenesis but could be partially due to disrupted non-canonical nuclear export of large cargo. However, this would not invalidate our findings that CLCC1 is important for cellular processes that require the fusion of the INM and ONM. Another limitation of this study is that whether CLCC1 can promote fusion by itself is still unclear. Our CRISPR-Cas9 screens did not yield any strong positive regulators of nuclear egress (other than CLCC1) that could be fusogen candidates. However, a nuclear envelope fusogen could be encoded by an essential gene, and if so, would be lost from the CRISPR library during passaging. Lastly, our structural analysis of CLCC1 is limited to AlphaFold-generated models because no experimentally determined structural information is available yet.

In conclusion, our study has identified CLCC1 as an important host factor involved in herpesviral nuclear egress. Loss of CLCC1 resulted in the accumulation of PEVs in the PNS and a large reduction in viral titer in infected cells, as well as the accumulation of NBs in uninfected cells. Combing with other reports have implicated CLCC1 in host processes, including nuclear pore complex formation and lipid droplet biogenesis. We propose that CLCC1 promotes membrane fusion in these processes by interacting with target membranes, oligomerizing, and deforming membranes. While the precise mechanism by how CLCC1 promotes fusion of the nuclear envelope remains undiscovered, collectively, our findings illuminate an ancient cellular membrane fusion mechanism important for nuclear envelope morphogenesis that herpesviruses hijack or co-opt for capsid nuclear egress. The discovery of the key cellular player mediating an essential step in replication that is conserved across all herpesviruses could present opportunities for the exploration of pan-herpesviral therapeutic strategies.

Methods

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal antibody 8F519 was produced by Cell Essentials, Inc. from a hybridoma generated by Dr. Jay Brown (University of Virginia) and provided by the University of Virginia Stem Cell Core Facility. Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody was purchased from Thermo Scientific (A28175). Rabbit anti-CLCC1 polyclonal antibody was purchased from Sigma (HPA009087). Rabbit anti-beta-actin monoclonal antibody was purchased from ABclonal (AC026). Rabbit anti-Bip polyclonal antibody was purchased from Proteintech (11587-1-AP). IRDye-800 conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody was purchased from Li-Cor (926-32211).

Cell culture and maintenance

HeLa, Vero, HEK293T, Hep2, HFF, and PK15 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, CCL-2, CCL-81, CCL-23, SCRC-1041, CCL-33). All the cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM)(Cytiva, SH30285.02) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S)(Cytiva, SV30010) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)(Biowest, S1680-500; Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10438026). Vero UL34 complementing cells (tUL34CX)62 (a gift from Richard Roller, University of Iowa) were grown under the same conditions as Vero cells but were supplemented with 400 mg/mL G418 (Selleck Chemicals, S3028) every other passage. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Viruses

HSV-1 strain GS3217 is a strain F derivative that encodes an NLS-tdTomato transgene under the control of a CMV immediate-early (IE) promoter in place of the envelope glycoprotein gJ20. PRV strain GS7741 is a strain pBecker3 derivative that encodes an mCherry-NLS transgene under control of an MCMV IE promoter in place of the US2 gene63. HSV-2 strain 186 was isolated from a genital lesion in 1960s64. These viral strains were gifts from Greg Smith (Northwestern University). HSV-1 strain F US3-K220A, containing an inactivating point mutation (K220A) in the US3 kinase gene65, was a gift from Richard Roller (University of Iowa).

Generation of UL34-null HSV-1 strain

The bacterial artificial chromosome plasmid (BACmid) of HSV-1 with a UL34 deletion (BAC_GS3217-d34) was generated by En Passant Mutagenesis66. A start and stop codon (5’-ATGTAA-3’) flanked kanamycin resistance gene was PAR-amplified using the UL34 depletion primers with GS1439 as the template. Then, the PCR product was electroporated into the E. coli GS1789 harboring the HSV-1 F GS3217 BACmid (a gift from Greg Smith, Northwestern University). The first recombination occurred though heat induction. The bacteria were then inoculated onto kanamycin-containing plates to select for colonies with successful insertion. These colonies underwent a secondary arabinose-induced recombination to remove the kanamycin resistance gene, leaving the UL34 fully replaced by the start and stop codons. The BACmid was first checked by restriction enzyme digestion, then the UL34 deletion site was verified by PCR-amplifying the mutant region using the UL34 checking primers, and sequencing to confirm the complete removal of UL34.

Next, UL34 complementing cells (Cre_tUL34CX) were seeded into a 6-well plate and infected with Ad5CMVCre-eGFP(UI Viral Vector Core, VVC-U of Iowa-1174) at an MOI of 10. The BAC_GS3217-d34 was transfected using the GenJet transfection reagent (SignaGen Laboratories, SL100489), and the cells were overlaid with 0.75% methylcellulose-containing medium (Sigma). 50 μL of virus-containing supernatant was collected from a single visible plaque ~5 days post-transfection and stored at −80 °C for future usage.

Virus titration

For HSV-1 F strain GS3217 and HSV-2, plaque assays were performed with HeLa (for nuclear egress assay) and Vero (for propagation and growth curve) cells. For HSV-1 F strain GS3217-d34, plaque assays were performed with Cre_tUL34CX cells (for propagation). For HSV-1 US3-K220A strain, plaque assays were performed with Vero cells (for nuclear egress assay and propagation). For PRV strain GS7741, plaque assays were performed in HeLa (for nuclear egress assay) and PK15 (for propagation and growth curve) cells. Briefly, for all virus strains, HeLa, Vero, Cre_tUL34CX, or PK15 cells were seeded into 12-well plates on day 1 at 200,000 cells/well. On day 2, cells were incubated for 1 h with a serial dilution of either stock virus or supernatant collected from viral growth curves. After the incubation, the media was replaced with growth media containing 0.75% methylcellulose. 3 days post infection, media was aspirated out, and cells were fixed and stained with 1% crystal violet (Sigma, C0775) in a 1:1 methanol (Fisher Scientific, A411-4):water solution. Plaques were quantified and used to calculate plaque forming units per mL (PFU/mL).

For HSV-1 F strain GS3217-d34, for nuclear egress assay, the titration was performed by seeding HeLa cells into a 96-well plate on day 1 at 15,000 cells/well. On day 2, the virus was serially diluted and added to cells. On day 3, tdTomato+ cells were counted using a fluorescence microscope, and the titer was calculated by counting tdTomato positive cells and expressed as infectious units per mL (IU/mL).

Virus propagation

For virus propagation, Vero (for HSV-1 F GS3217, HSV-2 186, HSV-1 US3-K220A), Cre_tUL34CX (for HSV-1 F GS3217-d34) or PK15 (for PRV GS7741) cells were seeded in a T175 flask at 1 × 107 cells per flask on day 1. On day 2, cells were infected at MOI 0.01, and supernatant was harvested once the cytopathic effect (CPE) reached 100%, typically 72 h post infection. The virus was pelleted by centrifugation at 41,000 g for 40 min at 4 °C, resuspended in Opti-MEM (Gibco, 31985088) containing 10% glycerol (Chem-Impex, 30144), and stored at −80 °C for future use.

Generation of the HeLa-Cas9 cell line

Lentiviral vectors pXPR_111 (Cas9), pXPR_047 (GFP and sgGFP), and pRosettav2 (antibiotic control) were provided by the Genetic Perturbation Platform group at the Broad Institute. To determine the correct antibiotic selection conditions, HeLa cells were first infected with pRosettav2 or left uninfected, then selected with different concentrations of blasticidin for 2 weeks or puromycin for 1 week. A concentration of each antibiotic that killed all uninfected cells was used for future selections (10 µg/mL blasticidin; 2 µg/mL puromycin).

To generate HeLa-Cas9 cells, 1.5 million HeLa cells were infected with 200 µL of pXPR_111 (Cas9) in the presence of 4 µg/mL polybrene. Starting 24 h post infection, cells were selected with 10 µg/mL blasticidin for 2 weeks.

Cas9 activity was tested by infecting HeLa and HeLa-Cas9 cells with pXPR_047 (GFP and sgGFP) using the same conditions as the pXPR_111 infection, then selecting with 2 µg/mL puromycin for 1 week. After selection, uninfected HeLa cells, pXPR_047 infected HeLa cells, and pXR_047 infected HeLa-Cas9 cells were collected and assessed by flow cytometry. The GFP+ populations in infected HeLa and infected HeLa-Cas9 cells were compared, with the uninfected HeLa cells serving as a control for background signal. Infected HeLa cells were 95% GFP + , while infected HeLa-Cas9 cells were <25% GFP + .

Generation of the Gattinara library HeLa cells

Lentiviral sgRNA Gattinara library (CP0073) targeting the whole genome (19,993 target genes, and a total of 40,964 sgRNAs) was provided by the Genetic Perturbation Platform group at the Broad Institute. The viral titer of the library was 7.21 × 107 viral particles (VPs)/mL.

To determine the amount of virus to use for infection, Gattinara library lentivirus was titrated on HeLa-Cas9 cells. Briefly, lentivirus was first serially diluted. Next, 1 mL of diluted virus was mixed with 1 mL of 1.5 × 106 HeLa-Cas9 cells in the presence of 4 μg/mL polybrene. Subsequently, the 2 mL mixtures were put into 12-well plates and spun down at 900 g for 1.5 h. The next day, 2 μg/mL of puromycin was used for selection. 7 days post selection cells were collected, and a cell viability assay was performed. The amount of lentivirus that resulted in a 30% cell survival rate when compared with non-infected and non-selected cells was used for library cell generation. To achieve a good coverage of the sgRNAs in the whole library, Gattinara library HeLa cells were generated by infecting a total of 1.5 × 108 HeLa-Cas9 cells with the desired amount of lentivirus. After the selection, cells were maintained in the presence of 2 µg/mL puromycin-containing medium until further use, and cells with a passage number higher than 7 were discarded due to the loss of sgRNAs in the library.

Flow cytometry-based nuclear egress assay

HeLa, Hep2, or HFF cells were seeded in 6-well plates on day 1 at 400,000/well. On day 2, cells were infected with the desired virus (HSV-1 strain GS3217 at MOI of 5, HSV-1 strain GS3217-d34 at MOI of 10). 24 h post infection, cells were trypsinized with 0.05% trypsin (Cytiva, SH30236.01) and collected by centrifuging at 500 g for 5 min. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Thermo Scientific, J19943K2) for 1 h at room temperature before permeabilization for 20 min at room temperature with either 40 μg/mL digitonin (to permeabilize only the plasma membrane) or 0.2% TritonX-100 (to permeabilize all membranes) in PBS (Invitrogen, BN2006). Next, cells were blocked with 0.5% BSA (Fisher Scientific, BP1600100) for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated with capsid-specific 8F5 primary antibody (1:2000) for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. The cells were then washed with PBS and incubated with an Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclear egress was measured by flow cytometry and quantified as the double-positive population (tdTomato+ indicating infection and Alexa488+ indicating capsids in the cytosol) in the digitonin permeabilized samples relative to the double positive population in the Triton X-100-permeabilized samples. Gating was based on cells infected with HSV-1 F strain GS3217-d34, which has a nuclear egress defect, in which most cells are tdTomato+ /Alexa488-, or control cells infected with HSV-1 F strain GS3217, in which most cells are tdTomato+ /Alexa488 + . Percent nuclear egress was calculated as (% digitonin-treated double-positive cells)/(% Triton X-100-treated double-positive cells) * 100% and then normalized to the average percent nuclear egress in desired control conditions (typically in HeLa or Int_4 cells) to calculate normalized nuclear egress percent as follows: (% nuclear egress of sample)/(% nuclear egress of averaged control) * 100%.

Whole-genome CRISPR screens

1.5–2.5 × 108 Gattinara library HeLa cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes at 1 × 107 cells/dish. On day 2, Gattinara library HeLa cells were infected with HSV-1 F strain GS3217 at an MOI of 5. Following infection, the cells were treated according to the flow-cytometry-based nuclear egress assay procedure outlined above. Approximately 5–10% of Gattinara library HeLa cells were tdTomato + /Alexa488- (no nuclear egress), and ~70–85% were tdTomato + /Alexa488+ (had nuclear egress). As a control for the nuclear egress assay, 1 × 107 HeLa cells were infected with HSV-1 F strain GS3217-d34, which has a nuclear egress defect, at an MOI of 10, and ran in parallel.

DNA was isolated from both populations of Gattinara library HeLa cells using the Qiagen Blood DNA kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol, except that fixed cells were incubated with proteinase K at 65 °C overnight instead of at 70 °C for 10 min. The extracted DNA was sent to the Broad Institute for sequencing. Two independent Gattinara library transductions of HeLa-Cas9 cells were done (2 biological replicates), each with three independent HSV-1 infections (3 technical replicates), for a total of 6 experiments.

To generate a volcano plot of the results, the log-normal reads were obtained from the Broad Institute. The reads were combined by gene name using R, and a paired t-test was performed in PRISM. The p-value and log2 fold change (LFC) for each gene were collected, and a volcano plot was generated in R with the ggplot2 package.

Generation of CLCC1 knockout HeLa, Hep2, and HFF cell lines

Lentiviruses encoding sgRNAs targeting genes of interest or intergenic regions as controls were generated using three plasmids of either pRDA_118 or LentiCRISPRv2 (sgRNA-containing plasmid), psPAX2 (packaging plasmid), and pMD2.G (VSV-G envelope protein plasmid). pRDA_118 and pMD2.G were provided by the Genetic Perturbation Platform group at the Broad Institute. LentiCRISPR v2 and psPAX2 were gifts from Dr. Alexei Degterev (Tufts University, Addgene 52961 and 12260). sgRNAs used to knockout CLCC1 were sgRNA1: 5’-CATGTGCTGAGACATATAGG-3’, sgRNA3: 5’-AGCTGTGGACATATGTACGT-3’, and sgRNA6: 5’-TGTGTGCCAAAAAGATGGAC-3’. The control intergenic site targeting sequence was 5’-ACAAAGGACCCCGGCGAAAG-3’. SgRNAs were inserted by either Golden gate assembly (sgRNA1 and sgRNA3) into LentiCRISPR v2 to make the plasmids (LentiCRISPRV2_sgCLCC1_1 and LentiCRISPRV2_sgCLCC1_3), or Gibson assembly (sgRNA3, sgRNA6, and sgInt) into the pRDA-118 backbone to make the plasmids (pRDA118_sgCLCC1_3, pRDA118_sgCLCC1_6, and pRDA118_sgInt).

Lentiviruses were generated by transfecting HEK293T cells with three plasmids (sgRNA-containing, packaging, and VSV-G envelope protein) using GenJet transfection reagent. After 48 h the lentivirus-containing supernatant was collected and stored at −80 °C for future use.

Bulk CLCC1 knockout cells (cko3_bulk, cko6_bulk) and bulk intergenic site targeting cells (Int_bulk) were generated by infecting HeLa-Cas9 cells with lentivirus targeting CLCC1 (from pRDA118_sgCLCC1_3 or pRDA118_sgCLCC1_6) or an intergenic-site (from pRDA118_sgInt), followed by selection with 2 μg/mL puromycin for 1 week, and maintenance in puromycin containing medium. Single-cell clones (cko3_2, cko3_4, cko6_1, cko6_2, Int_3, Int_4) were selected by collecting single cells from the bulk population using single-cell sorting with a flow cytometer, followed by expanding them.

For HeLa, Hep2 and HFF cells, bulk CLCC1 knockout cells were generated by infecting HeLa, Hep2 and HFF cells with the lentivirus containing sgCLCC1 and sgCLCC13 (generated with plasmid LentiCRISPRv2_sgCLCC1_1 and LentiCRISPRv2_sgCLCC1_3) or mock infected, followed by selection with 2 μg/mL puromycin for 1 week. Cell lines were maintained in puromycin containing medium.

Generation of CLCC1 rescue cells

pSB_CLCC1_EF1α plasmid was generated by inserting a Kozak consensus sequence 5′-GCCACC-3′ followed by CLCC1 gene synthesized by GenScript with the following sequence changed (5′-CATAGTTAAGCATGTCTGTG-3′ to 5′-CGTAATTCAGCATATCGGTC-3′, 5′-ATTATATGGATCCACTCCAA-3′ to 5′-GTTGTACGGGTCAACGCCGA-3′) into pSBbi-Hyg (Addgene, 60524) with the restriction site of SfiI. pSB_CLCC1_hPGK1 plasmid was generated by switching the EF1α promoter from the pSB_CLCC1_EF1α to hPGK1 promoter through GenScript services.

Bulk CLCC1 rescue cell lines (Int_4_EF1α, Int_4_hPGK1, cko3_4_EF1α, cko3_4_ hPGK1, cko6_1_EF1α, cko6_1_hPGK1) were generated by co-transfecting 1 μg of pSB_CLCC1_EF1α or pSB_CLCC1_hPGK1 with 100 ng of pCMV (CAT) T7-SB100 into cko3_4 or cko6_1 cells using GenJet transfection reagent. Cells were selected for 2 weeks with 300 μg/mL hygromycin. Single clones (cko3_4_R_1, cko3_4_R_6, cko6_1_R_1, cko6_1_R_6) were selected by collecting single cells from the bulk population using single-cell sorting with a flow cytometer, followed by expanding them.

Generation of CRISPR-resistant-CLCC1 plasmid and CRISPR-resistant point-mutation cells

pSB_CLCC1_CR plasmid was generated by replacing the CLCC1 sgRNA targeting sequence from the pSB_CLCC1_hPGK1 as follows: (5′-CATGTGCTGAGACATATAGG-3′ to 5′-CACGTTCTTCGTCACATTGG-3′, 5′-AGCTGTGGACATATGTACGT-3′ to 5′-AACTTTGGACCTACGTGCGC-3′, 5′-GCATATTGGAAAAGGAACTG-3′ to 5′-ACACATCGGCAAGGGCACCG-3′, and 5′-TGTGTGCCAAAAAGATGGAC-3′ to 5′-TTTGCGCGAAGAAAATGGAT-3′).

All point mutations, D25E, D25E/D181R, D152R/D153R, E175R/D176R, W209A, S224A, C254A, C254A/C279A, S263R, W267R, D277R, K298E were generated in the pSB_CLCC1_CR backbone using GenScript services.

CRISPR-resistant-CLCC1 cells or point mutation cell lines were generated by co-transfecting 1 μg of pSB_CLCC1_CR or point mutation plasmids (D25E, D25E/D181R, D152R/D153R, E175R/D176R, W209A, S224A, C254A, C254A/C279A, S263R, W267R, D277R, K298E) with 100 ng of pCMV (CAT) T7-SB100 into HeLa, Int_4, cko3_4 or cko6_1 cells using GenJet transfection reagent and selecting cells for 2 weeks with 300 μg/mL hygromycin. Cell lines were maintained in hygromycin-containing media.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed with cold PBS, lysed with RIPA buffer, and the lysates were spun at 14,000 g. Supernatants were collected, and the total protein concentration was measured by BCA assay and normalized across samples for each experiment. Next, samples were mixed with SDS sample buffer, incubated at 95 °C for 5 min, and loaded into SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, 456-1086). The proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare, 10600002) using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad). The blot was then blocked with 5% milk in TBST buffer for 1 h at room temperature, incubated with primary antibody (anti-CLCC1 1:2000; anti-Bip 1:1000; anti-actin 1:1,000,000) overnight at 4 °C, washed with TBST 3 times, and incubated with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature. Images were recorded using an Odyssey LI-COR imager.

Confocal microscopy

For visualizing nuclear egress, HeLa/Int_4/cko3_bulk cells were seeded at 75,000 cells/well in a 24-well plate (Greiner Bio-One, 662160) with a glass coverslip in each well (Chemglass, CLS-1760-012). The next day, cells were infected by either HSV-1 F GS3217 at MOI of 5 or HSV-1 F GS3217-d34 at MOI of 10. At 24 h post infection, cells were fixed with 4% PFA at room temperature for 20 min and either partially permeabilized by incubation in 40 μg/mL digitonin in PBS or fully permeabilized by 0.2% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature. Cells were subsequently blocked with 0.5% BSA for 1 h, incubated with 8F5 primary antibody (1:2000) overnight at 4 °C, washed 3 times with PBS, incubated with Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature, washed 3 times with PBS, and stained with DAPI (1 µg/mL) for 5 min at room temperature. The coverslips were mounted onto glass slides using prolong antifade mountant (Invitrogen, P36930).