Abstract

Cu-based nanocatalysts hold promise for the reverse water–gas shift (RWGS) reaction. However, irreversible sintering of the Cu catalyst for deactivation remains a persistent challenge under thermal or photothermal processes. In this study, we develop an anti-sintering catalyst using CuNiMgAl layered-double-hydroxide (LDH)-derived hydroxyl engineering to anchor ultrafine CuNi nanoparticles, achieving stable photothermal RWGS conversion. For Cu3Ni-MA, the oxyphilic Ni dopants facilitate the formation of hydroxyl-coordinated Cu2+–Ni2+ species during the calcination of LDH-derived materials; meanwhile, the Ni incorporation enhances the plasmonic effect of CuNi nanocatalysts to drive H2 spillover for hydroxyl replenishment under light irradiation, which is diverged from conventional Cu3Ni alloy-based catalysts. This Cu3Ni-MA achieves a CO production rate of 339.8 mmol g−1 h−1 with 98% selectivity, outperforming thermal catalysis by 3.5-fold in RWGS conversion. Notably, the catalyst exhibits robust photothermal CO2 hydrogenation stability, preserving >99% of its original activity and CO selectivity during 30 d of intermittent start–stop cycles and 280-h continuous testing. This study offers alternative perspectives for designing anti-sintering catalysts for photothermal catalytic systems by coupling dynamic hydroxyl regulation with plasmonic activation mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The reverse water–gas shift (RWGS) reaction is gaining prominence for CO production and as a versatile building block in tandem catalytic systems to develop downstream chemicals1. Cu-based catalysts for the RWGS reaction were widely used in industrial processes, which uniquely enable selective CO2 activation while suppressing methane formation2,3,4. However, their practical deployment faces critical challenges, including rapid deactivation under high-temperature conditions and trade-offs between catalytic activity and long-term stability5,6,7,8. The low Taman temperature (407 °C) of Cu-based nanocatalysts and the endothermic nature of the RWGS reaction result in sintering and eventual deactivation of the catalysts under industrial operating temperatures (>500 °C)9. In this context, solar-driven photothermal processes have recently emerged as ideal alternatives to decrease the operating temperatures by utilizing light to reduce the activation energy10 while simultaneously leveraging the photogenerated hot carriers to enhance the adsorbed reactant activation and intermediate transformation kinetics11,12. Current design strategies of photothermal catalysts, such as catalyst support engineering through the introduction of oxygen vacancies, hydroxyl groups, or heteroatoms3,13, nanostructural dimensional control4,14, and light-trapping architecture optimization15,16, primarily focus on the photothermal conversion efficiency of RWGS. Specifically, Ding et al. demonstrated that boron doping modulates the electronic state of Cu to facilitate charge transfer for achieving a CO yield of 124.7 mmol g−1 h−1 under light irradiation; however, the catalytic stability exhibited a substantial decline within 10 hours5. Although these strategies improve the reaction kinetics, the irreversible and progressive sintering of the Cu nanostructure remains insurmountable in the photothermal catalytic RWGS reaction.

To mitigate Cu nanoparticle (NP) migration, the atomization–sintering dynamic equilibrium in metal catalysts under high-temperature operation offers an intrinsic stabilization pathway17,18,19,20, as has been demonstrated by the thermal atomization of Pd NPs via thermodynamically stabilized Pd–N coordination at 900 °C19. For Cu-based systems, analogous phase dynamics are observed under milder conditions. Specifically, hydroxylated Cu2+ species can spontaneously redistribute into atomic-scale clusters on hydroxyl-rich supports under ambient humidity9, where hydroxyl groups coordinate to mobile Cu species in a similar manner to Pd–N coordination. Bao et al. demonstrated that hydroxyl groups function as dynamic stabilizers of metal active sites in water-containing reactant atmospheres, enabling self-repairing capability through the reverse Ostwald ripening process21. However, the atmosphere-dependent (e.g., oxygen- or water-dependent) dynamic hydroxyl-mediated stabilization poses practical limitations for Cu-based RWGS catalysts. Under operational conditions, H2 readily reduces hydroxylated Cu2+ species to metallic Cu without hydroxyl regeneration, thereby accelerating sintering. Consequently, sustaining hydroxyl-mediated dynamic stabilization with hydroxyl replenishment under reducing environments remains a critical challenge.

Recent studies in CO2/CO hydrogenation have demonstrated a synergistic interplay between the strong hydroxyl binding capability of supports and the H2 spillover effects, enabling a dynamic interfacial hydroxyl regeneration22,23. Although Cu exhibits weak H2 activation capacity, photothermal excitation generates hot carriers that populate the H2 antibonding orbitals, effectively weakening the H–H bonds and enhancing their dissociation12. Strategically introducing oxyphilic dopants in catalysts can enhance the oxygen affinity24,25,26, providing a potential approach to regulate the surface oxygen species of Cu-based catalysts. Ni, as an oxyphilic metal, exhibits a substantial hydroxyl adsorption energy of 314.1 kJ mol−1 on its surface, stabilizing hydroxyl intermediates through its strong binding capability27. Beyond its conventional application as a catalytic dopant to modulate electronic/geometric configurations for enhanced plasmonic effects, Ni enables the dynamic modulation of hydroxyl adsorption by virtue of its strong hydroxyl affinity. This synergistic combination can be expected to facilitate H2 spillover–induced hydroxyl regeneration in Ni-doped Cu catalysts under photothermal conditions. However, this strategy has not been reported to date.

Herein, we describe the construction of ultra-fine CuNi bimetallic NPs supported on hydroxyl-engineered substrates derived from an LDH precursor under a reductive atmosphere, where oxyphilic Ni dopants spontaneously induce hydroxyl-coordinated Cu2+–Ni2+ moieties, differing from conventional alloying approaches. This configuration modulates the electronic structure of Cu, enhances the plasmonic effect, and strengthens the hydroxyl affinity. The optimized nanocatalyst enables hydroxyl replenishment to maintain dynamic ligands surrounding the metal surface via hot carrier–driven H2 spillover, while substantially reducing the energy barriers of the rate-limiting CO2 hydrogenation step to carboxylate. As a result, a highly efficient photothermal RWGS performance is achieved, with a CO production rate of 339.8 mmol g−1 h−1 with 98% selectivity and approaching thermodynamic equilibrium, which represents a considerable enhancement over thermal catalysis. Furthermore, stability assessments revealed that the high activity and CO selectivity (>98%) were preserved during 30-d start–stop cycling and 280-h continuous operation under illumination. This work establishes a nanocatalyst design paradigm that integrates hydroxyl engineering with plasmonic activation, effectively resolving the activity–stability dichotomy in photothermal catalysis.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and characterization of nanocatalysts

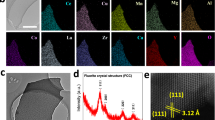

LDH precursors are efficient for the construction of hydroxyl-engineering catalysts owing to the retained stability of the surface hydroxyl groups, which could further mitigate the high-temperature hydroxyl loss in a reducing atmosphere28,29. Thus, a CuNiMgAl LDH precursor with a certain atomic ratio was prepared and then thermally reduced to obtain hydroxylated CuNi–MgAl catalysts (Fig. 1a). The percentages of Cu and Ni in the catalysts were measured by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (Supplementary Table S1). Unless otherwise stated, the Cu and Ni contents in CuNi–MgAl were 17.07 and 7.72 wt% (denoted as Cu3Ni-MA), respectively. Compared with Cu-MA and Ni-MA (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2), Cu3Ni-MA primarily comprised CuNi bimetallic NPs and amorphous alumina supported on two-dimensional (2D) MgO nanosheets, as revealed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Supplementary Fig. S3). High-resolution TEM confirmed the presence of highly dispersed CuNi bimetallic NPs on MgO (Fig. 1b), with 0.208 nm lattice fringes corresponding to CuNi (111) planes (Fig. 1c). The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping revealed that the transformation of the LDH precursor was accompanied by a successful mixing of CuNiMgAl (Fig. 1d). To further investigate the microstructure of CuNi bimetallic NPs, aberration corrected high-angle annular dark field scanning TEM (AC-HAADF-STEM) imaging was performed. AC-HAADF-STEM imaging and EDS elemental mapping provided visual evidence for the high dispersion of ultra-fine CuNi bimetallic NPs with an average size of 2.82 ± 1.3 nm (Fig. 1e, f). High-resolution EDS elemental maps and lines reveal precise spatial overlap between Cu/Ni signals and nanoparticle contours in AC-HAADF-STEM images, confirming the retention of bimetallic integrity (Fig. 1g, h, and Supplementary Fig. S4). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of controlled Cu/Ni ratios showed that the diffraction peaks of CuNi(111) phase shifted monotonically to higher angles compared with Cu (111) due to the atomic radius-driven lattice contraction (Fig. 1i). For the diffraction peak near 63°, its shift with Ni content aligns with the lattice contraction trend. The CuNiO (220) peak moves from 62.5° in Cu3.9Ni0.1-MA to 62.8° in Cu2Ni2-MA, until approaching the NiO (220) peak at 62.9° in Ni-MA. The in situ XRD patterns revealed the structural changes from the LDH precursor to CuNi bimetallic NPs anchored on the MgAl support (Supplementary Fig. S5). Moreover, the physicochemical properties of the bimetallic nanocatalysts with different molar ratios were investigated via Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) measurements and are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. The results suggested that the obtained Cu, Ni, and CuNi nanocatalysts possessed similar surface area due to the LDH-derived 2D nanosheet structure.

a Synthesis route of the hydroxylated CuNi-MA catalyst. b TEM and c HRTEM image and the corresponding fast Fourier transform patterns (inset). d Mg, Al, Cu and Ni elemental mapping images of Cu3Ni-MA. e AC-HAADF-STEM images and particle size distribution (inset). f–h AC-HAADF-STEM image and the corresponding EDS mapping/line scan (inset). The ultra-fine CuNi nanoparticles (NPs) as shown in white circles. The scale bars in b–d, f–h are 20 nm, 2 nm, 200 nm, 10 nm, 3 nm, 5 nm, respectively. i XRD pattern and partial enlargement (right side) of Cu-MA, Cu3.9Ni0.1-MA, Cu3.5Ni0.5-MA, Cu3Ni-MA, Cu2Ni2-MA and Ni-MA. j, k Cu 2p and Ni 2p XPS spectra of Cu3Ni-MA, Cu-MA and Ni-MA.

Ex-situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and X-ray adsorption near-edge structure spectroscopy (XANES) were conducted to explore the surface chemical state and electronic structure of the fresh nanocatalysts. XPS characterization showed the Cu0/Cu+ 2p3/2 peak of the bimetallic nanocatalyst shifted towards a lower binding energy compared with the Cu-MA catalyst (Fig. 1j). Similarly, compared with the Ni-MA nanocatalyst, a positive binding energy shift of the Ni2+ peak in the bimetallic nanocatalyst suggested an electron redistribution between the Cu and Ni atoms30 (Fig. 1k). These findings were corroborated by the XANES spectra. A slight negative shift in the Cu K-edge and a positive shift in the Ni K-edge were observed for the bimetallic NPs compared to the monometallic samples, with the white line intensity changes paralleling these shifts (Fig. 2a, b). For the Fourier transformed extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) curve of Cu K-edge, the difference between the Cu-Ni (~2.2 Å) characterizing the Cu3Ni-MA and the Cu-Cu (~2.3 Å) characterizing Cu foil demonstrated Ni atoms were dispersed in a Cu lattice (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S6)31,32. The coordination number (CN) of Cu-Ni (2.2) on Cu3Ni-MA was lower than Cu-Cu (12) on Cu foil, indirectly evidencing the ultrasmall size of CuNi NPs (Supplementary Table S2). The Ni K-edge FT-EXAFS spectra demonstrated the small magnitude of the peak at ~2.4 Å (phase-uncorrected) corresponding to Ni-O-Cu bonds that was longer than the Ni-O-Ni at ~2.6 Å in NiO reference (Fig. 2d). The bond length difference between Ni–O–Cu and Ni–O–Ni aligns with atomic radii differences (Supplementary Table S2), which is consistent with the result of XRD. The presence of Cu-Ni and Ni-O-Cu bonds was further confirmed via a wavelet transform EXAFS (WT-EXAFS) analysis compared with Cu-Cu and Ni-O-Ni bonds in Cu foil and NiO reference (Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Fig. S7), indicating that a strong interaction between Cu and Ni. Additionally, the fitted CN of the Ni-promoted Cu3Ni-MA catalyst showed increased metal-oxygen coordination compared to monometallic catalysts, reflecting the greater hydroxylated surface coverage on the Ni-promoted catalysts33. Theoretical simulation studies were also performed to clarify the electronic structure of Cu3Ni-MA. The charge density difference of Cu3Ni-MA showed that the introduction of Ni affected the electronic structure of Cu (Supplementary Fig. S8). Despite the relatively minor yet beneficial influence of hydroxyl groups on the electronic structure, Ni incorporation induced pronounced changes in the d-band states compared to hydroxylated Cu-MA. This was evidenced by a significant upshift of the d-band center from −1.99 eV (Cu-MA) to −1.48 eV (Cu3Ni-MA) in projected density of states (PDOS) calculations (Supplementary Fig. S9). As reported, the d-band center model is an effective descriptor for adsorbate–metal interactions34,35, which suggests the potential of Cu3Ni-MA for the catalytic CO2 hydrogenation.

a Cu K-edge XANES spectra of the Cu-MA and Cu3Ni-MA. b Ni K-edge XANES spectra of the Ni-MA and Cu3Ni-MA. c FT-EXAFS of the Cu K-edge of the Cu-MA and Cu3Ni-MA. d FT-EXAFS of the Ni K-edge of the Cu-MA and Cu3Ni-MA. e, f WT-EXAFS of Cu K-edge signal for the Cu3Ni-MA and Cu foil, respectively. g EPR spectra of Cu-MA and Cu3Ni-MA. h TGA curve of Cu-MA, Ni-MA and Cu3Ni-MA.

The Cu 2p3/2 XPS spectra of Cu-MA and Cu3Ni-MA showed two peaks at approximately 932.4 eV and 934.4 eV (Fig. 1j), which can be respectively assigned to Cu0/Cu+ and Cu-OH species9,36,37. Compared with Cu-MA, Cu3Ni-MA increased the kinetic energy of the Cu LMM Auger peaks at 916.6 and 914.4 eV (Supplementary Fig. S10), which was assigned to Cu-OH species9. The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) technique was employed to clearly identify the Cu-OH species in Cu3Ni-MA. Since Cu-OH species with an unpaired electron in the dx²–y² orbital are active in EPR, whereas Cu2+ ions in crystalline CuO exhibit no EPR signal owing to pronounced antiferromagnetic interactions38,39. As shown in Fig. 2g, a large EPR signal was observed for Cu3Ni-MA and Cu-MA, further indicating the presence of Cu-OH species in the sample. Therefore, the Cu 2p3/2 peak at 934.4 eV and the Cu LMM Auger peak at 914.4 eV indicated that the Cu2+ species in Cu3Ni-MA were mainly in the form of hydroxylated Cu (Cu–OH) species. The proportion of Cu–OH species relative to the total Cu species in Cu3Ni-MA (26.1%) was higher than that in Cu-MA (17.1%) (Fig. 1j). The Ni 2p3/2 peak at 855.8 eV could be identified as Ni-OH species rather than NiO for both Cu3Ni-MA and Ni-MA, as reported by previous literatures40,41. The proportion of Ni-OH species increased for Cu3Ni-MA samples (Fig. 1k). These indicate that the addition of Ni increased the amount of hydroxyl-coordinated Cu2+-Ni2+ species, because of the high hydroxyl affinity of Ni species. Furthermore, the O 1 s spectra of the Cu3Ni-MA revealed the presence of surface oxygen species, including hydroxyl groups and surface-adsorbed water42. The ratio of surface oxygen species to lattice oxygen increased from 65.9% in Cu-MA to 72.7% in Cu3Ni-MA, showing a similar enhancement trend to that of the Cu–OH species (Supplementary Fig. S11). The relative density of the surface hydroxyl groups in the Cu3Ni-MA was further estimated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)43,44. As expected, after doping Ni2+ species into Cu, the density of the surface hydroxyl groups on Cu3Ni-MA increased from 119.6 to 159.4 OH nm−2 (Fig. 2f). The coverage of surface hydroxyl species was known to affect the material's affinity for water molecules. Increasing surface hydroxyl content can enhance the hydrophilicity. The instantaneous contact angle of a water droplet on the surface of Cu3Ni-MA and Cu-MA was determined to be 16.1° and 31.6°, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S12). The infiltration of water droplets into the support occurred in 0.82 s for Cu3Ni-MA, whereas it required 2.44 s for Cu-MA. This indicated that Cu3Ni-MA had better hydrophilicity than Cu-MA, aligning with the strong hydroxyl binding property of Ni. Therefore, the engineered CuNi bimetallic NPs not only exhibited a high-affinity hydroxylated surface but also pronounced synergistic interactions between Cu and Ni, which were crucial for the photothermal activity and stability.

Photothermal catalytic performance of CO2 hydrogenation

Solar-driven CO2 hydrogenation measurements were performed using a homemade continuous gas flow reaction system (Supplementary Fig. S13) at ambient pressure under full-spectrum light irradiation (300 W xenon lamp). Generally, rational reactor design dictates photothermal catalytic efficiency by governing mass transfer dynamics, localized temperature control, and long-term stability45. Therefore, our homemade flow reactor employed a swirl gas inlet technique to improve the mass transfer efficiency (Supplementary Fig. S14), achieving a substantially more uniform gas velocity distribution compared with the single-point gas inlet method. This approach promoted the formation of a uniform reaction environment on the nanocatalyst surface, stabilized the internal temperature of the reactor, and maintained the dynamic equilibrium of the catalytic system, thereby underpinning the reaction stability. As shown in Fig. 3a, Cu3Ni-MA exhibited a high CO production rate of 339.8 mmol g−1 h−1 with 98% selectivity, while with the individual Cu-MA or Ni-MA only had a CO yield of 131.9 mmol g−1 h−1 and 91.2 mmol g−1 h−1, respectively. This indicated that the introduction of Ni greatly enhanced the photothermal catalytic performance of Cu-based catalysts. Further increasing the Ni content decreased the CO selectivity (Supplementary Fig. S15). Thus, optimizing the amount of Ni doping was essential to enhance the activity of the Cu-based material in the RWGS reaction. Additionally, the optimized Cu/Ni ratio supported on SiO2 exhibited a significant decrease in photothermal RWGS activity and stability, indicating the crucial role of hydroxyl groups formed in the LDH precursor synthesis (Supplementary Fig. S16). Furthermore, the CO production rates under light irradiation were consistently much higher than those without illumination in the temperature range examined (Fig. 3b). Meanwhile, Cu3Ni-MA exhibited activation energies of 98.2 and 47.2 kJ mol−1 under thermal and photothermal conditions, respectively. This reduction in the energy barrier, together with the corresponding non-parallel plots, demonstrated a synergy between hot carriers and thermal energy46. The generation of hot carriers by the CuNi bimetallic NPs was primarily due to plasmonic effects47, which can be examined using ultraviolet–visible–infrared absorption spectroscopy. The progressively enhanced visible-to-NIR absorption observed in Ni-incorporated Cu systems with increasing Ni content (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. S17), in which the typical LSPR absorption peak of catalysts occurs at approximately 600 nm. To gain further insight into the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect, the distribution of light-induced localized electric fields around the CuNi bimetallic NPs with the appropriate size was simulated using the finite difference time domain method. As shown in Fig. 3d, the electric field intensity considerably increased upon Ni doping into the Cu NPs, revealing that the addition of Ni species could dramatically enhance the hot carrier generation and the plasmon–photon coupling effect. Therefore, the photothermal activity of the RWGS reaction was substantially increased by enhancing the plasmonic effect via Ni doping.

a CO evolution rate over Cu3Ni-MA, Cu-MA, and Ni-MA. Reaction conditions: H2/CO2 ratio = 1:1, 50 sccm, 50 mg catalyst,t and full-spectrum with 1.4 W cm-2 light intensity without external heat. b Comparison of the CO evolution rates at different temperatures under light and dark conditions, and the corresponding Arrhenius plots with apparent activation energy (Ea) (inset). The error bars represent the s.d. of three independent measurements of the same catalyst. c UV-vis-NIR absorption spectra of Cu-MA, Cu3.9Ni0.1-MA, Cu3.5Ni0.5-MA, Cu3Ni-MA, Cu2Ni2-MA, and Ni-MA. d Simulated electric fields according to the actual distribution of Cu and Cu3Ni NPs supported on MgO. e Long-term stability test of Cu3Ni-MA and Cu-MA nanocatalysts under the same reaction conditions for catalytic performance tests. f Cu and g Ni K-edge XANES spectra of fresh and spent Cu3Ni-MA.

To further explore the photothermal catalytic potential of the light-induced electric field around the ultra-fine CuNi bimetallic NPs, a series of tests was performed under various light intensities. As the light intensity increased from 0.6 to 1.4 W cm−2, the CO2 conversion rate and CO yield were considerably enhanced, with only a slight decrease in the CO selectivity (Supplementary Fig. S18). This intensity balances efficient hot carrier generation at the LSPR frequency of 600 nm with controlled thermal contributions, thereby justifying its selection for high efficiency of light energy conversion to chemical energy (Supplementary Fig. S19). In addition, Cu3Ni-MA features a combination of high effectiveness and stability, positioning it as a competitive candidate among the Cu-based photothermal catalysts reported to date3,4,5,8,13,14,48,49,50 (Supplementary Table S5). To assess the feasibility of the photothermal RWGS reaction powered by natural sunlight, the reaction was performed using a fixed reactor and concentrated sunlight using a Fresnel lens (Supplementary Fig. S20). When sunlight was focused onto the Cu3Ni-MA nanocatalyst during the winter season 1 h before noon, the photothermal RWGS reaction was initiated. After seven consecutive days of outdoor experiments, the same batch of Cu3Ni-MA exhibited a CO2 conversion rate of approximately 40% and nearly 100% selectivity for CO, demonstrating the potential applications of the nanocatalyst for natural light-driven RWGS reactions. Apart from its photothermal catalytic activity, the stability of the Cu3Ni-MA nanocatalyst was evaluated as a critical factor in determining its overall performance. A long-term stability test was conducted for Cu3Ni-MA and Cu-MA under photothermal conditions at 320 °C. Notably, after 280 h of photothermal RWGS reaction, the activity fluctuation of the Cu3Ni-MA nanocatalyst was less than 1%, whereas Cu-MA suffered a 74.7% activity loss under identical conditions (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, Cu3Ni-MA demonstrated notable stability during one month of start–stop cycling tests, suggesting its potential for integration with intermittent renewable H2 systems (Supplementary Fig. S21). To confirm the stability of the nanocatalyst, the spent catalyst recovered after the long-term stability test was subjected to an XRD analysis, which revealed a slight decrease in the diffraction peaks without any evidence of crystallographic phase change, thus confirming the operational stability of this material (Supplementary Fig. S22). The XPS spectra of Cu3Ni-MA after the stability experiment also showed negligible changes in the chemical states, with increased hydroxyl signals likely attributable to pre-test ambient humidity exposure, demonstrating the high hydroxyl affinity of the nanocatalyst (Supplementary Fig. S23). The XANES spectrum at the Cu/Ni K-edge for the fresh and spent Cu3Ni-MA demonstrated minimal energy shifts and nearly unchanged WL intensities, excluding significant valence changes or dissolution (Fig. 3f, g). The FT-EXAFS curves of Cu/Ni K-edge exhibited the critical path (Cu-O, Cu-Ni, Ni-O, and Ni-O-Cu) retain identical scatter peak, confirming the robustness of Cu-Ni interfaces (Supplementary Fig. S24). Meanwhile, the TEM and AC-HAADF-STEM images of the spent nanocatalyst after the stability test did not demonstrate discernible alterations compared with those of the fresh nanocatalyst and demonstrated that it remained homogeneously distributed (Supplementary Figs. S25 and 26). In addition, Cu3Ni-MA suffered a 63% activity loss under dark conditions but regained activity upon 1-h H2 treatment under illumination, demonstrating that light irradiation was indispensable for maintaining the catalytic stability (Supplementary Fig. S27). Therefore, to clarify the relation between stability and the presence of hydroxyl groups, the relative density of surface hydroxyl groups on the spent nanocatalyst was investigated via TGA. Cu3Ni-MA retained a relatively high density of hydroxyl groups after the photothermal stability test (Supplementary Fig. S28), indicating that the surface hydroxyl groups may be an effective strategy for anchoring active metal sites under steady-state operation conditions. To confirm these results, the photothermal catalytic stability of the nanocatalyst was further clarified by performing a mechanistic study.

Study of the mechanism of the photothermal RWGS reaction

The adsorption processes on the catalyst surface govern the photothermal catalytic activity22. Therefore, CO2 temperature-programmed desorption (CO2-TPD) experiments were performed to determine the CO2 adsorption capacity of the CuNi bimetallic NPs. The CO2-TPD analysis indicated that Cu3Ni-MA had a stronger adsorption capacity for CO2 than the Cu/Ni monometal nanocatalysts (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, H2 temperature-programmed desorption (H2-TPD) was conducted to investigate the adsorption of H2, which was a key factor in evaluating the hydrogenation mechanism and catalytic activity of Cu3Ni-MA. The H2-TPD profiles showed that the H2 desorption peaks of Cu3Ni-MA were broad, more intense, and shifted to lower temperatures compared with those of Cu-MA and Ni-MA (Fig. 4b), revealing an easier H2 activation on the bimetallic nanocatalyst. CO temperature-programmed desorption (CO-TPD) experiments were also performed to assess the CO adsorption characteristics. Compared with Cu-MA and Ni-MA, the CO-TPD profile of Cu3Ni-MA showed no notable CO desorption peaks within the range of strong CO adsorption peaks, suggesting weak surface binding of CO (Fig. 4c). These results demonstrated that the Cu3Ni-MA nanocatalyst exhibited strong CO2 adsorption and H2 activation capacities with suppressed CO poisoning, collectively contributing to its enhanced photothermal catalytic activity and stability.

To further reveal the dynamic correlation between surface adsorption and reaction activity, in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) was conducted to monitor the evolution of the surface intermediates. After continuously flowing a mixed atmosphere of CO2 and H2 for 30 min without illumination, peaks ascribable to bicarbonate51 appeared at 1673 and 1303 cm−1, which can be attributed to the interaction of CO2 with the surface hydroxyl groups (Fig. 4d). These peaks were considerably stronger for Cu3Ni-MA than for Cu-MA (Supplementary Fig. S29), which is in agreement with its higher hydroxyl density as revealed by the TGA results. When exposed to full-spectrum illumination, the in situ DRIFT spectra of Cu3Ni-MA under the reaction atmosphere showed peaks at 1627 and 1294 cm−1, corresponding to carboxylate (COOH), and a peak at 1456 cm−1, corresponding to polydentate carbonate (p-CO32−)52,53. Cu-MA showed the same reaction intermediates, except for the bidentate carbonate (Fig. 4e). This difference also indirectly indicated the successful introduction of the CuNi bimetallic NPs, since the signal of polydentate carbonate typically suggests the interaction of CO2 with multiple metal centers. With prolonging the irradiation time, the bicarbonate signal gradually decreased as the COOH species and gas-phase CO formed. In contrast, under dark conditions, the formation of COOH species and gas-phase CO was much lower than that under light irradiation (Supplementary Figs. S29 and S30), which confirmed the enhancement of the RWGS activity under illumination. In addition, formate species (HCOO, 2897 and 2942 cm−1) and bridge CO species (1955 cm−1) were only observed in the spectrum of the Ni-MA catalyst44,54 (Supplementary Fig. S31). Thus, Cu3Ni-MA and Cu-MA presented the same reaction pathway (carboxyl mechanism) involving the key intermediate COOH, whereas the formate pathway was dominant in Ni-MA, indicating that hydroxylated Ni2+ species enhanced the activity by optimizing the surface chemical environment rather than by pathway switching.

The chemical state and surface compositions of the nanocatalyst were monitored during the reaction conditions using quasi in situ XPS characterization. Initially, H2-pre-treated Cu3Ni-MA showed a Cu0/Cu+ binding energy decrease from 932.4 to 932.3 eV, which was accompanied by a downward shift of the Ni2+ binding energy (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. S32). Upon light irradiation, the further negative shift of the Cu0/Cu+ binding energy from 932.28 to 931.89 eV reflected an increase in the electron density at the Cu sites of CuNi NPs. The photoinduced enhancement of the local electric field contributed to the accumulation of photogenerated hot carriers12. In addition, the peak for Ni2+ in the Ni 2p XPS spectra was slightly shifted to lower energy, further demonstrating the migration of hot carriers to the surface CuNi sites55. This interfacial charge behavior was also evidenced by both Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) and Photoluminescence (PL) measurements (Supplementary Fig. S33). In contrast, the Cu 2p XPS spectra of Cu-MA exhibited a slightly negative shift under illumination (Supplementary Fig. S34), which can be ascribed to the weak localized electric field without Ni doping. Under dark conditions, the negative shift of the Cu0/Cu+ binding energy for Cu3Ni-MA was substantially lower than that under light irradiation, confirming the presence of photogenerated hot carriers. In addition, the C 1s spectra of Cu3Ni-MA exhibited a signal of surface bicarbonate species at 288.5 eV after the adsorption of the reaction gas (Fig. 5b)56. Under illumination, this peak decreased and partially transformed into a COOH peak at 289.8 eV57, aligning with the results of in situ DRIFTS. In darkness, the peak intensity of the bicarbonate species decreased without intermediate formation, which allows linking the reaction rate reduction to the absence of illumination. This suggested that light promoted the CO2 hydrogenation capacity, which can be attributed to the strengthened local electric field.

The variations in the oxygen species throughout the reaction process were also noteworthy. In Cu3Ni-MA, the proportion of hydroxylated Cu2+ species decreased from 26.1% to 12.7% after H2 pre-treatment but regenerated to 18.7% under illumination, while remaining unchanged in darkness (Fig. 5a). However, this recovery was not observed in Cu-MA. The stable Ni–OH bonding energy, which remained unchanged under all conditions, provided robust anchoring for the adsorption of oxygen species, synergistically driving the reversible evolution of surface oxygen species in Cu3Ni-MA, which increased from 48.2% to 85.2% under light but remained static in darkness (Fig. 5c). In contrast, Cu-MA exhibited no light-responsive oxygen species dynamics (Supplementary Fig. S35), which demonstrates the direct correlation of Ni incorporation with hydroxyl regeneration. Notably, light irradiation was another key factor for the regeneration of hydroxyl groups. Meanwhile, in situ XPS confirmed the accumulation of hot carriers on the CuNi sites, which could effectively weaken the H–H bonds to drive H2 dissociation. Previous studies have reported that H2 spillover facilitated the migration and stabilization of active H2 at the metal–support interface for promoting the formation of hydroxyl groups on the support surface22,23. Thus, the regeneration of hydroxyl groups could be associated with H2 spillover on Cu3Ni-MA. The H2 spillover effect was examined by treating a mixture of yellow WO3 powder and Cu3Ni-MA with H2 under light and dark conditions. As expected, the mixture of Cu3Ni-MA and WO3 exhibited a darker blue color after H2 pre-treatment under illumination, whereas a lighter blue color was observed in the absence of light (Supplementary Fig. S36), implying that the photothermal process enhanced the mobility of H2 species58.

To identify the relationship between hydroxyl regeneration and H2-spillover, quasi in situ H-D exchange occurring on the surface hydroxyl groups was used to quantify hydroxyl content under pre-treatment in different reaction conditions. Prior to the H-D exchange experiments, H2-pretreated Cu3Ni-MA catalyst was exposed to the reaction atmosphere for 10 h under various conditions. Additionally, H-D signals from the fresh sample (without in situ pre-treatment)were collected. Figure 5d demonstrated that the HD signal intensities from H-D exchange on the sample treated with full-spectrum and Vis irradiation were nearly identical to those of the fresh reference. Nevertheless, the HD signal intensities were greatly decreased under specific wavelength regions (UV and IR) illumination and dark conditions at 320 °C (Fig. 5e). Without Ni species, the HD signal intensities were also decreased even under full-spectrum illumination (Supplementary Fig. S37). To investigate whether H2-spillover exhibited analogous wavelength dependency, we further conducted in-situ H-D exchange experiments for Cu3Ni-MA in a mixed H2-D2 atmosphere to elucidate the impact of different wavelengths in H2 dissociation. The rate of HD formation normalized by specific surface area was as follows: Full-spectrum (100) > Vis (93) > IR (61) > Dark (55) > UV (48), indicating that Vis has a much higher ability in the H2 dissociation than UV, IR, and dark conditions (Supplementary Fig. S38). Consequently, both hydroxyl regeneration and hydrogen spillover exhibit wavelength dependency, with visible light dominantly facilitating these two processes. This reveals that H2 spillover is critical for hydroxyl group generation under photothermal conditions. To further confirm the real-time formation and stability of hydroxyl groups during reaction conditions, H–D exchange experiments were conducted to elucidate the H2 spillover–driven dynamics of hydroxylation under photothermal RWGS conditions. After pre-processing and background elimination, CO2 and D2 were introduced for adsorption 30 minutes before photoirradiation. Upon the photothermal process, a gradual reduction in the signal of the surface -OH groups was observed, whereas the peak at 2611 cm−1 corresponding to -OD on the carrier surface increased progressively (Fig. 5f)59, confirming the occurrence of H2 spillover–driven hydroxyl group generation under photothermal conditions. In summary, the Ni-modified hydroxyl-engineered nanocatalyst not only exhibits optimized surface adsorption and electronic structure under illumination but also achieves dynamic stabilization of active sites via light-driven H2 spillover–enhanced interfacial hydroxyl regeneration, offering an effective strategy for the design of highly sintering-resistant photothermal catalysts.

Elucidation of the catalytic mechanism via theoretical calculations

To gain insight into the mechanism governing the enhanced activity and stability of the Cu3Ni-MA nanocatalyst, density functional theory calculations were conducted. The introduced Ni species modulated the Cu electronic structure and enhanced the LSPR, thus promoting the illumination-activated H2 spillover–driven regeneration of the surface hydroxyl groups for an efficient and stable RWGS photothermal reaction. Therefore, to investigate the stable hydroxyl-mediated RWGS process under illumination, a hydroxylated environment comprising water molecules and hydroxyl groups was simulated. Additionally, for simplicity, we assume that surface hydroxyl groups in the hydroxylated model, after reacting and releasing hydrogen atoms, regenerate through H2 spillover. Moreover, considering that the surface hydroxyl groups were continuously consumed until depleted without illumination, non-hydroxylated models were also simulated. The hydroxylated Cu3Ni-MA model facilitated an enhanced H2 adsorption with a more negative Gibbs free energy (ΔG = −0.6 eV) compared with non-hydroxylated Cu3Ni-MA and Cu-MA (Supplementary Fig. S39). This enhanced adsorption, as supported by the H2-TPD results, was associated with the H2 spillover on the hydroxylated Cu3Ni-MA, which was enhanced by the surface hydroxyl groups60. DFT calculation was further used to identify the ability of hydrogen-species migration between CuNi NPs and the MgO-Al2O3 LDO support in the hydroxylated and non-hydroxylated Cu3Ni-MA model. The ΔG at the CuNi/ MgO-Al2O3 interface decreased from 2.12 to 1.90 eV in the hydroxylated model, indicating that the CuNi/MgO-Al2O3 interface may act as a hydrogen-transportation channel with a low hydrogen-migration barrier (Supplementary Fig. S40). Meanwhile, the strongest CO2 adsorption performance was achieved by introducing Ni species and hydroxylated surfaces (Fig. 6a), as evidenced by the results of CO2-TPD and in situ DRIFTS. Notable variations in the subsequent CO2 hydrogenation were observed among hydroxylated Cu3Ni-MA, non-hydroxylated Cu3Ni-MA, and hydroxylated Cu-MA. Figure 6b, c demonstrated that the hydroxylation of Cu3Ni-MA reduced the activation barrier for CO2 protonation to 1.23 eV from the values of 2.45 eV for hydroxylated Cu-MA and 1.51 eV for non-hydroxylated Cu3Ni-MA, which was the rate-determining step in the whole CO2 hydrogenation processes. Simulations confirmed that the Ni species and surface hydroxyl groups effectively promoted the formation of the COOH* intermediate through H2 spillover–mediated proton transfer, consistent with the DRIFTS results. For the subsequent elementary step, the activation energy for the dehydroxylation of *COOH to generate *CO on Cu3Ni-MA and Cu-MA was determined to be 0.6 and 0.73 eV, respectively. The results showed that *CO preferentially evolved on the Cu3Ni-MA catalyst, which is in accord with its enhanced performance in the photothermal RWGS reaction.

a Calculated CO2 adsorption energy. b Free energy of hydroxylated and non-hydroxylated Cu3Ni-MA. c Free energy of hydroxylated Cu3Ni-MA and Cu-MA. Energies of the transition states (TS) with respect to CO2 hydrogenation are shown, along with the corresponding calculated models (inset). d Schematic of the proposed mechanism. The grey, blue, yellow, red, pink, and brown balls represent Ni, Cu, Mg, O, H, and C atoms, respectively.

According to the spectroscopic and theoretical results, the mechanism depicted in Fig. 6d can be proposed for the photothermal catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 over Cu3Ni-MA. The oxyphilic Ni species not only effectively modulates the electronic structure of Cu to construct a nanocatalyst with high hydroxyl affinity but also facilitates the LSPR and H2 spillover effect. Hot carrier accumulation at the CuNi sites enhances the H2 spillover–driven hydroxyl regeneration for maintaining the hydroxylated surfaces while simultaneously reducing the barrier energy for the CO2 hydrogenation process. Without illumination, the surface hydroxyl groups are gradually consumed until depleted, resulting in poor activity and poor stability. Conversely, the photothermally activated Cu3Ni-MA nanocatalyst can create a stable hydroxylated environment on its surface, facilitating the RWGS reaction and enhancing the robust nature of the CO2 conversion process.

In summary, we develop a highly active and stable hydroxyl-engineered CuNi bimetallic nanocatalyst for the photothermal RWGS reaction based on the self-replenishment of hydroxyl groups derived from an enhanced H2 spillover effect. Ni doping generates surfaces with high hydroxyl affinity and Cu–Ni synergistic interactions, which induce the formation of hydroxylated Cu2+–Ni2+ species and promote photogenerated hot carriers accumulation under illumination. These plasmon-induced carriers facilitate the interfacial H2 spillover, dynamically regenerating hydroxyl groups to stabilize the active sites during prolonged photothermal RWGS operation. This architecture achieves a high CO production rate of 339.8 mmol g−1 h−1 with 98% selectivity, demonstrating a 3.5-fold increase compared with thermal catalysis. Notably, the nanocatalyst maintained >99% of its initial activity during 280 h of continuous operation and 30-d start–stop cycling, rendering it compatible with intermittent renewable hydrogen systems. The illumination-driven stability of the photocatalytic activity is of paramount importance to extend the catalyst lifetime and enhance the practical applicability of photothermal catalysis.

Methods

Chemical

Hexamethylenetetramine (HMT, 98%), Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (99%), Al(NO3)3·9H2O (99%), Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (98%) and Mg(NO3)2·6H2O (99%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. and were used without any further purification. The water used in the synthesis of all catalysts was deionized (DI) with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm.

Preparation of catalysts

Depending on the desired Ni/Cu molar ratio in the catalysts, appropriate amounts of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O and Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (Supplementary Table 1) were dissolved together with 9 mmol Mg(NO3)2·6H2O and 3 mmol Al(NO3)3·9H2O in deionized water (60 ml) to make the metal-salt precursor solution under magnetic stirring. Then, 0.02 M HMT was added to the mixture. After stirring for 30 minutes, the light blue solution was sealed into a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 120 °C for 24 hours. The resulting solid slurry was dried under vacuum. The dry precursor was packed into a tube furnace, with a ramp rate of 5°C min-1 and held for 1 h in 50 sccm H2/Ar (10/90, v/v) to obtain hydroxyl-engineer CuNi nanocatalysts.

Catalytic activity trials

The photothermal catalytic activity of the as-synthesized sample towards CO2 conversion was conducted in a home-made flow reactor (70 ml) connected with a gas chromatograph (GC, Agilent 7890B). Typically, 50 mg of the catalyst was uniformly spread as a thin layer on the quartz fiber filter membrane (diameter 47 mm, pore size 0.22 μm) with a circular area of 12.56 cm2. Before the test, the sample was pretreated with 10 sccm H2 (ultrahigh purity, 99.999%) at 300 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, a stream of syngas (CO2/H2/He = 40/40/20, 99.999%) flowed at a rate of 50 sccm into the reaction chamber. The reactor was initially held in darkness to achieve an adsorption-desorption equilibrium of the reactant gases on the surface of the catalyst, after which the full-spectrum Xe lamp (Beijing China Education Au-Light Co., Ltd.) was illuminated. The temperature of the photothermal process was detected by the infrared (IR) camera (Supplementary Fig. S41). The outlet gas products were quantified by a GC (7890B, Agilent) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and flame ionization detectors (FID). CO, CO2, and CH4 were analyzed by using a carbon molecular sieve column (TDX-1) with TCD. CH4, hydrocarbon,s and oxygenates were analyzed by using a PoraBOND Q PT column (CP73531PT) with FID. During the photothermal RWGS reaction, no side products, apart from CO and CH4, were detected. The CO2 conversion (\({S}_{C{O}_{2}}\)), CO selectivity (\({S}_{CO}\)), and CO evolution rate were calculated as follows:

The light-to-thermal conversion efficiency was evaluated by observing the temperature variation of the sample exposed to light within a reaction atmosphere. The infrared camera was adjusted for accuracy, with a reflectance value set to 0.95. The temperature changes during the reaction process at a consistent distance were monitored using an infrared camera. The catalyst’s surface temperature was the average of its central peak temperatures recorded by infrared imaging.

Material characterization

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the materials were obtained on a Bruker D8 advanced powder X-ray diffractometer using Cu Kα irradiation (40 kV, 40 mA). The morphologies and EDS mapping images were observed using a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (JEOL, JEM-2100F) and high-angle annular dark field-scanning transmission electron microscopy (JEM-ARM200F), which were operated at 200 kV. The UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) were characterized by a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Cary 5000) with BaSO4 as the internal reflectance standard. BET surface area and pore diameter distribution of the photocatalysts were carried out using a Micromeritics TriStar II 3020 surface area analyzer, employing nitrogen adsorption at 77 K. The thermogravimetric analyses of used catalysts were carried out on Netzsch STA 449 F3 thermogravimetric analyzer, and the thermal treatment protocol was set as follows: under a nitrogen atmosphere, the sample was heated from 25 °C to 120 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, maintained at 120 °C for 10 min to eliminate physically adsorbed water, and subsequently heated to 600 °C at 20 °C/min. Water contact angle tests were obtained by a Drop shape analyser (KRUSS-DSA25)

TPD measurements

The temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) was performed with the Micromeritics Autochem 2910 instrument. For CO2-TPD, approximately 100 mg of the catalyst was loaded in a U-shaped quartz reactor. The sample was pretreated with 10% H2/He gas at 300 °C for 1 hour. Then, as the tube cooled down to room temperature, the gas was switched to He gas for 30 min (to remove the physically adsorbed H2). After 60 minutes of purging with 30 mL/min CO2 gas and then 30 minutes of purging with Ar gas (to remove the physically adsorbed CO2), the tube was heated up to 550 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. For H2-TPD and CO-TPD, the measurements followed similar procedures, except that the CO2 gas was replaced with H2 or CO gas.

In situ XPS characterization

Quasi in-situ XPS characterization was collected on a Thermo Escalab 250Xi photoelectron spectrometer, using non-monochromatized Al-Kα X-ray with a photon energy of 1486.6 eV as the excitation source. During the in-situ XPS experiment, the sample stage was illuminated with full-spectrum light from a 300 W Xe lamp. The light irradiation was channeled into the analysis chamber via an observation window. The catalysts were held on the sample holder and activated with illumination in the pretreatment chamber under CO2 + H2 (1:1) conditions. After stabilizing under specific reaction conditions, the sample was moved to an ultrahigh-vacuum chamber for room-temperature XPS measurements. To explore electron transfer dynamics, in situ collections of O 1 s, Ni 2p, and Cu 2p spectra were conducted under both dark and light conditions, with binding energy adjustments based on the C 1 s spectra at 284.8 eV.

In situ XRD characterization

In situ XRD experiments were conducted on a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer equipped with Cu Kα radiation operated at an accelerated voltage of 40 kV and 40 mA detector current, using an XRK-900 high-temperature cell. The catalyst was loaded and heated to target temperatures (30, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 °C) at a ramping rate of 7.5 °C min−1 under a 10% H2/Ar atmosphere, with XRD patterns collected at each temperature point. The sample was held at 500 °C for 1 h for additional measurements.

In situ DRIFTS characterization

In-situ diffuse reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (DRIFTS) measurements were performed through a Bruker VERTEX 80 v Fourier transform spectrometer equipped with an MCT detector cooled by liquid nitrogen and a commercial reaction chamber from Harrick Scientific (Supplementary Fig. S42). The sample was pretreated with H2 at 300 °C for 1 h, then cooled to the ambient temperature. The background spectrum was recorded under the Ar atmosphere to subtract the interference of the catalyst spectrum. During in-situ photothermal characterization, the catalysts were exposed to a continuous flow of CO2/H2 gas, using a 300 W xenon lamp as the light source for DRIFTS. Without illumination, the CO2/H2 mixture was fed into the chamber for DRIFTS as the temperature was raised to 320 °C and held constant for 30 minutes.

H-D exchange characterization

A quasi in situ H-D exchange experiment was performed in a homemade reaction cell integrated with a modified TPD-MS (Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920), enabling real-time irradiation (Supplementary Fig. S43). Prior to the H-D exchange experiments for the distinction and quantification of hydroxyl groups, the samples were exposed for 10 h under the reaction atmosphere with specific conditions, including dark at 320 °C and illumination under various wavelengths. The reaction temperature under irradiation was monitored in real-time using a thermocouple and an infrared camera. After stopping the reaction, the catalyst was purged with He for 1 h to remove physically adsorbed species. Subsequently, it was heated under D2 atmosphere for monitoring the HD signal (m/z = 3)via mass spectrometry.

In situ H-D exchange experiments were also employed to assess the dissociation ability of hydrogen under the photoirradiation process. The samples were firstly pre-treated with H2 (10 sccm) at 300 °C, followed by cooling to room temperature. The reaction atmosphere was maintained with H2 (10 sccm). Under irradiation with specific spectral conditions, including full-spectrum, UV, Vis, and IR, the temperature was controlled at 320 °C. Under dark conditions, the sample was heated up to 320 °C after pretreatment. After that, the D2 with a fixed amount (10 sccm) was injected into the H2 stream. The signals of H2 (m/z = 2), D2 (m/z = 4), and HD (m/z = 3) were analyzed by mass spectrometry.

H–D isotope exchange DRIFT spectra were obtained using a similar procedure. The catalyst was pre-reduced with H2 under specific conditions and then cooled to 50 °C. To monitor hydroxyl group regeneration during photothermal operation, the catalyst was pretreated and background spectra acquired in argon flow prior to introducing CO₂ and D₂ co-adsorption for 30 min. The spectra were collected under prolonged illumination

Electrochemical measurement

Electrochemical measurements are carried out with an Autolab (PGSTAT302N, Metrohm) workstation using a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell with a working electrode. A platinum foil (GaossUnion, 99.99%) is used as the counter electrode, and a saturated Ag/AgCl electrode (GaossUnion) as the reference. A sodium sulfate solution (Aladdin, 99.5%) is used as the electrolyte. The fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) glass working electrode was prepared by ultrasonic cleaning in absolute ethanol for 2 hours and subsequent drying at 60 °C overnight. A homogeneous ink was made by dispersing 5 mg of the powder in 1 mL of DMF (Aladdin, 99.5%) under ultrasonication. Then, 10 μL of this ink was drop-cast onto the conductive surface of the FTO glass (which had a section masked with tape) and was dried naturally. The photocurrent measurement was conducted at 0.6 V versus RHE using a 150 W xenon lamp with light chopping every 20 s.

Finite Difference Time Domain (FDTD) simulations

To investigate the electric field enhancement behind the structure, Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) simulations were carried out using FDTD Solutions software (Lumerical Co. Ltd). For simulation, the metal NPs were modeled as spheres of 4 nm in diameter. We modeled 3 NPs at a distance of 1.0 nm from each other. The metal NPs were placed on an MgO sheet. This model was chosen to mimic Cu3Ni-MA and Cu-MA, in which the metal NPs are located close to each other. An x-polarized total-field scattered-field (TFSF) source having a wavelength range of 200 nm to 1100 nm was used as the excitation source to mimic the photocatalysis conditions. The perfect match layer (PML) boundary was used along the x-axis, y-axis, and z-axis. The mesh size was set to 1 nm for the structure during FDTD simulations.

DFT calculation details

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional were performed to analyze the reaction mechanism61,62. The projected augmented wave (PAW) method was used to describe the ionic cores, while the valence electrons were treated with a plane-wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 400 eV. The convergence criteria were set to 10−5 eV for the electronic energy and 0.05 eV Å−1 for the forces. The 8.38 Å \(\times\) 12.58 Å supercell of Mg (100) was constructed as the support basis. Due to computational cost limitations, Cu6Ni3 and Cu4 clusters are loaded on the surface to mimic larger nanoparticles with H2 dissociation capability. For the model with water and hydroxyl, six water molecules, two hydroxyl and four hydrogen atoms are placed on the surface. The atomic coordinates of the optimized computational models have been provided in supplementary data 1. The free energy was calculated using the equation:

where \({E}_{{DFT}}\) represents the ground-state energy obtained from DFT. The vibrational frequencies of adsorbed species were computed within the harmonic approximations using the finite difference method to account for vibrational entropies (\({S}_{vib}\)) and zero-point energies (\({E}_{EPZ}\)) corrections to the Gibbs free energy. The CI-NEB method was used to calculate the kinetic barrier of the transition state with five images between the initial state and the final state. While our DFT calculations provide valuable insights, we note the inherent challenge in modeling the exact dynamic structure of the catalyst under operating conditions, which presents an opportunity for future, more sophisticated simulations.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the main text and Supplementary information. Extra data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Khoshooei, M. A. et al. An active, stable cubic molybdenum carbide catalyst for the high-temperature reverse water-gas shift reaction. Science 384, 540–546 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Develop high-performance Cu-based RWGS catalysts by controlling oxide-oxide interface. ACS Catal. 15, 3475–3486 (2025).

Wan, L. et al. Cu2O nanocubes with mixed oxidation-state facets for photocatalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Nat. Catal. 2, 889–898 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Cu-based high-entropy two-dimensional oxide as stable and active photothermal catalyst. Nat. Commun. 14, 3171 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Boron-doped Cu-Co catalyst boosting charge transfer in photothermal carbon dioxide hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. Energy 352, 124045 (2024).

Zhao, Y.-F. et al. Insight into methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation on Cu(111): Complex reaction network and the effects of H2O. J. Catal. 281, 199–211 (2011).

Chen, C. S., Cheng, W. H. & Lin, S. S. Study of iron-promoted Cu/SiO2 catalyst on high temperature reverse water gas shift reaction. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 257, 97–106 (2004).

Yue, X. et al. Visible light-regulated thermal catalytic selectivity induced by nonthermal effects over CuNi/CeO2. Chem. Eng. J. 458, 141491 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. Water-assisted oxidative redispersion of Cu particles through formation of Cu hydroxide at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 15, 3046 (2024).

Xin, Y. et al. Copper-based plasmonic catalysis: recent advances and future perspectives. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008145 (2021).

Luo, S., Ren, X., Lin, H., Song, H. & Ye, J. Plasmonic photothermal catalysis for solar-to-fuel conversion: current status and prospects. Chem. Sci. 12, 5701–5719 (2021).

Brongersma, M. L., Halas, N. J. & Nordlander, P. Plasmon-induced hot carrier science and technology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 25–34 (2015).

Deng, B., Song, H., Peng, K., Li, Q. & Ye, J. Metal-organic framework-derived Ga-Cu/CeO2 catalyst for highly efficient photothermal catalytic CO2 reduction. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 298, 120519 (2021).

Li, Y. F. et al. Cu atoms on nanowire Pd/HyWO3x, bronzes enhance the solar reverse water gas shift reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 14991–14996 (2019).

Yang, Z. et al. Visible light-assisted thermal catalytic reverse water gas reaction over Cu-CeO2: The synergistic of hot electrons and oxygen vacancies induced by LSPR effect. Fuel 315, 123186 (2022).

Ni, W. et al. Visible light enhanced thermocatalytic reverse water gas shift reaction via localized surface plasmon resonance of copper nanoparticles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 361, 131514 (2025).

Nie, L. et al. Activation of surface lattice oxygen in single-atom Pt/CeO2 for low-temperature CO oxidation. Science 358, 1419–1423 (2017).

Matsubu, J. C., Yang, V. N. & Christopher, P. Isolated metal active site concentration and stability control catalytic CO2 reduction selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3076–3084 (2015).

Wei, S. et al. Direct observation of noble metal nanoparticles transforming to thermally stable single atoms. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 856–861 (2018).

Ye, R. et al. Design of catalysts for selective CO2 hydrogenation. Nat. Synth. 288–302 (2025).

Li, R. et al. Dynamically confined active silver nanoclusters with ultrawide operating temperature window in CO oxidation. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 64, e202416852 (2025).

Kang, H. et al. Generation of oxide surface patches promoting H-spillover in Ru/(TiOx)MnO catalysts enables CO2 reduction to CO. Nat. Catal. 6, 1062–1072 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Engineering ZrO2-Ru interface to boost Fischer-Tropsch synthesis to olefins. Nat. Commun. 15, 5143 (2024).

Jalil, A. et al. Nickel promotes selective ethylene epoxidation on silver. Science 387, 869–873 (2025).

Tu, W., Ghoussoub, M., Singh, C. V. & Chin, Y.-H. C. Consequences of surface Oxophilicity of Ni, Ni-Co, and Co clusters on methane activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 6928–6945 (2017).

Kim, J. et al. Tailoring binding abilities by incorporating oxophilic transition metals on 3D nanostructured ni arrays for accelerated alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 1399–1408 (2021).

Zhao, W., Carey, S. J., Mao, Z. & Campbell, C. T. Adsorbed Hydroxyl and Water on Ni(111): heats of formation by Calorimetry. ACS Catal. 8, 1485–1489 (2018).

Liu, P., Zheng, C., Liu, W., Wu, X. & Liu, S. Oxidative Redispersion-derived single-site Ru/CeO2 catalysts with mobile Ru complexes trapped by surface hydroxyls instead of oxygen vacancies. ACS Catal. 14, 6028–6044 (2024).

Wright, C. M. R., Ruengkajorn, K., Kilpatrick, A. F. R., Buffet, J.-C. & O’Hare, D. Controlling the surface hydroxyl concentration by thermal treatment of layered double hydroxides. Inorg. Chem. 56, 7842–7850 (2017).

Lou, Y.-Y. et al. Phase-dependent electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to Ammonia on Janus Cu@Ni Tandem Catalyst. ACS Catal. 14, 5098–5108 (2024).

Wang, L.-X. et al. Dispersed nickel boosts catalysis by copper in CO2 hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 10, 9261–9270 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Cu-Ni alloy nanocrystals with heterogenous active sites for efficient urea synthesis. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 343, 123577 (2024).

Zhang, B., Xiang, S., Frenkel, A. I. & Wachs, I. E. Molecular design of supported MoOx catalysts with surface TaOx promotion for Olefin metathesis. ACS Catal. 12, 3226–3237 (2022).

Gorzkowski, M. T. & Lewera, A. Probing the Limits of d-Band center theory: electronic and electrocatalytic properties of Pd-shell-Pt-core nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 18389–18395 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Tailoring the d-band centers enables Co4N nanosheets to be highly active for hydrogen evolution catalysis. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 57, 5076–5080 (2018).

Deroubaix, G. & Marcus, P. X-Ray Photoelectron-Spectroscopy analysis of copper and zinc-oxides and sulfides. Surf. Interface Anal. 18, 39–46 (1992).

McIntyre, N. S. & Cook, M. G. X-ray photoelectron studies on some oxides and hydroxides of cobalt, nickel, and copper. Anal. Chem. 47, 2208–2213 (1975).

Weder, J. E. et al. Anti-inflammatory dinuclear copper(II) complexes with indomethacin.: Synthesis, magnetism and EPR spectroscopy.: Crystal structure of the N,N-dimethylformamide adduct. Inorg. Chem. 38, 1736–1744 (1999).

Liu, A. et al. Controlling Dynamic Structural Transformation of Atomically Dispersed CuOx Species and Influence on Their Catalytic Performances. ACS Catal. 9, 9840–9851 (2019).

Lian, K., Thorpe, S. J. & Kirk, D. W. Electrochemical and surface characterization of electrocatalytically active amorphous Ni-Co alloys. Electrochim. Acta 37, 2029–2041 (1992).

Venezia, A. M., Bertoncello, R. & Deganello, G. X-Ray Photoelectron-Spectroscopy Investigation of Pumice-supported Nickel Catalytsts. Surf. Interface Anal. 23, 239–247 (1995).

Ye, R. et al. Boosting low-temperature CO2 hydrogenation over Ni-based catalysts by tuning strong metal-support interactions. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 63, e202317669 (2024).

Mueller, R., Kammler, H. K., Wegner, K. & Pratsinis, S. E. OH surface density of SiO2 and TiO2 by thermogravimetric analysis. Langmuir 19, 160–165 (2003).

Zhao, D. et al. Surface modification of TiO2 by phosphate: Effect on photocatalytic activity and mechanism implication. J. Phys. Chem. C. 112, 5993–6001 (2008).

Brust D., Wullenkord M., Gómez H. G., Albero J. & Sattler C. Experimental investigation of photo-thermal catalytic reactor for the reverse water gas shift reaction under concentrated irradiation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, (2024).

Zhai, J. et al. Photo-thermal coupling to enhance CO2 hydrogenation toward CH4 over Ru/MnO/Mn3O4. Nat. Commun. 15, 1109 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Plasmonic Cu Nanoparticles for the Low-temperature Photo-driven Water-gas Shift Reaction. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 62, e202219299 (2023).

Robatjazi, H. et al. Plasmon-induced selective carbon dioxide conversion on earth-abundant aluminum-cuprous oxide antenna-reactor nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 8, 27 (2017).

Guo, J. et al. High-performance, scalable, and low-cost copper hydroxyapatite for photothermal CO2 reduction. ACS Catal. 10, 13668–13681 (2020).

Chen, Y., Hong, H., Cai, J. & Li, Z. Highly efficient CO2 to CO transformation over Cu-based catalyst derived from a CuMgAl-Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH). Chemcatchem 13, 656–663 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Shifting CO2 hydrogenation from producing CO to CH3OH by engineering defect structures of Cu/ZrO2 and Cu/ZnO catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 475, 146102 (2023).

Hill, I. M., Hanspal, S., Young, Z. D. & Davis, R. J. DRIFTS of probe molecules adsorbed on Magnesia, Zirconia, and Hydroxyapatite catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 9186–9197 (2015).

Huang, H. et al. Noble-metal-free high-entropy alloy nanoparticles for efficient solar-driven photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313209 (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Disclosing support-size-dependent effect on ambient light-driven photothermal CO2 hydrogenation over Nickel/Titanium Dioxide. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 63, e202318166 (2024).

Wan, X. et al. A nonmetallic plasmonic catalyst for photothermal CO2 flow conversion with high activity, selectivity and durability. Nat. Commun. 15, 1273 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Efficient thermal management with selective metamaterial absorber for boosting photothermal CO2 hydrogenation under sunlight. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311957 (2024).

Zhao, B. et al. Photoinduced reaction pathway change for boosting CO2 hydrogenation over a MnO-Co catalyst. ACS Catal. 11, 10316–10323 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Product selectivity controlled by nanoporous environments in zeolite crystals enveloping rhodium nanoparticle catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8482–8488 (2019).

Yamasaki, T., Iimura, S., Hosono, H. & Yamaguchi, S. Surface hydroxyl-ion diffusion and hierarchical structure of adsorbed water on hydrated layered double hydroxides. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127, 6045–6053 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Highly efficient hydrogenation of Nitrobenzene to Aniline over Pt/CeO2 catalysts: the shape effect of the support and key role of additional Ce3+ Sites. ACS Catal. 10, 10350–10363 (2020).

Mathew, K., Kolluru, V. S. C., Mula, S., Steinmann, S. N. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit self-consistent electrolyte model in plane-wave density-functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 234101 (2019).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21872030 and 22272025 to W.X.D), the Key Program of Qingyuan Innovation Laboratory (Grant No. 00121001 to W.X.D), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20241500 to X.Y.Y), and the Science & Technology Key Plan Project of Fujian Province (No.2021YZ037005 to W.X.D).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.J.W. proposed the project, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript; Y.M.Z., W.K.N., J.F.L. assisted in analyzing the experimental data; W.X.D., X.Y.Y., Z.Z.Z., and X.Z.F. co-supervised the whole project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the overall scientific interpretation and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chun-Hong Kuo and the other anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Zhou, Y., Ni, W. et al. Stable hydroxyl-anchored CuNi nanocatalysts from CuNiMgAl-LDH thermal reduction for efficient photothermal CO2 conversion. Nat Commun 16, 10497 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65537-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65537-x