Abstract

While the static theory for understanding defect properties in semiconductors in equilibrium has been established for decades, it fails to identify the crucial defects in nonequilibrium, such as under irradiation. In this paper, we develop a robust ab initio-driving multiscale modeling framework to identify deep-level defects in irradiated semiconductors with multidimensional defect properties. It overcomes two challenges unsolved in the past studies, that is, unambiguous nonequilibrium defect identification and exact deep-level transient spectroscopy (DLTS) simulation. Our method, verified by identifying the well-known deep-level defects in neutron-irradiated Si, is successfully applied to identify the controversial deep levels in neutron-irradiated wide-bandgap semiconductor, 4H-SiC, contributing to solving the half-century mystery of their atomic origin. Furthermore, we discover that defect origins of the same DLTS peaks vary significantly with annealing temperature, due to different defect types with distinct dynamic behaviors, breaking the long-lasting belief derived from the static defect theory. Our study not only expands the understanding of nonequilibrium defect physics of semiconductors, but also lays a solid foundation for controlling targeted crucial defects to improve material properties and device performances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The needs of deep-space exploration and nuclear-energy application for the future of mankind continue to explosive growth. Semiconductor devices are essential in space and nuclear equipment like spacecrafts and nuclear-power plants, which will be inevitably exposed to the irradiation of energetic particles like electrons, ions, and neutrons1,2. Energetic particles could knock atoms from the lattice and cause displacement damages to form various defects3,4, which would induce extra energy levels within the bandgap of semiconductors. These defect levels could act as carrier trapping, generation or recombination centers, leading to the performance degradation and even permanent failure of devices3. To eliminate the detrimental effects of defects4,5 and improve device radiation resistance, a long-standing goal is to unambiguously identify the crucial nonequilibrium defects in semiconductors. This is not only an important interdisciplinary study between nuclear physics and material science, but is also of great interest to the development of the semiconductor industry.

Defect-identification in semiconductors is always a great challenging issue, plaguing the researchers for more than half a century. While tracking defect formation and evolution is highly challenging in experiments, the existing static defect theories would fail to capture the complex defect properties like structures, charge states and densities in semiconductors, under nonequilibrium conditions like growth, irradiation, ion implantation, or annealing conditions. Thus, without a breakthrough in computational methods, identifying the crucial nonequilibrium defects in semiconductors is like looking for a needle in a haystack. One typical example is the defect identification in 4H-SiC, a crucial wide-bandgap semiconductor in the post-Si age. Among the detected deep-defect levels including EH1, Z1/2, EH3, EH4, EH5, EH6/7, S1 and S2 in 4H-SiC6,7,8, only Z1/2 and EH7 have been tacitly recognized as VC(=/0) and VC(+/0), respectively9,10 after decades of intensive efforts, leaving other defect levels largely unclear.

Among all the existing defect detection/characterization techniques11,12, the deep-level transient spectroscopy (DLTS)13 is probably the most widely used technique for non-destructive detection of crucial deep levels that affect device performances. It can detect the important properties of defects like electrical nature (donors or acceptors), level positions and carrier capture cross-sections14,15. Unfortunately, it cannot tell us the defect origins of DLTS peaks. Currently, defect types are commonly inferred using available identification methods that rely on single-dimensional defect property parameters like defect levels16,17,18,19. However, according to the principle of DLTS, the unambiguous defect identification requires the three-dimensional defect parameters including defect-level position, carrier capture cross-section, and defect concentration, especially for very close levels related to the superimposed DLTS signals. In the past decades, many theoretical studies20,21,22,23,24 have attempted to simulate DLTS but failed, mainly due to the following two challenges: (1) Accurate calculations of multidimensional defect properties, especially under different temperatures, are difficult when using existing methods25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32; (2) It is very hard to accurately solve the complex intra-cascade electrostatic potential24 induced by the carrier capture/emission of defects that plays a key role in renormalizing the Fermi level and thus regulates defect properties33,34,35.

In this paper, we have successfully solved the two challenges mentioned above, which allows us to innovatively develop a multiscale modeling framework for the unambiguous identification of deep-level defects in semiconductors at different temperatures. First, the modeling framework is validated by the identification of deep-level defects in the collector of a 2N2222 n-p-n type Si bipolar transistor33 (see sample details in Fig. S2a) under pulse neutron irradiation. Secondly, we have conducted the DLTS experiment and simulation of a 4H-SiC Schottky Barrier diode (SBD) (see sample details in Fig. S2b) after neutron irradiation and annealing, which are consistent with each other. Two overwhelming advantages of our method are presented over previous ones. Finally, by simulating the DLTS of neutron-irradiated 4H-SiC and comparing them with the experimental ones from 4H-SiC Junction Barrier Schottky (JBS) diodes after neutron irradiation and annealing at different temperatures, we unambiguously identified all typical deep levels in 4H-SiC, a key step to further improve device performance via precise defect passivation. Moreover, this work expands the understanding of defect physics of semiconductors far from equilibrium.

Results

Multiscale modeling framework

The developed modeling framework is shown in Fig. 1. First (Fig. 1a), the parameters of basic defect properties, that is, energy levels, carrier capture cross-sections and migration energies, are mainly obtained by density functional theory (DFT) calculations (see DFT calculations in “Methods” section). Secondly (Fig. 1b), based on these defect parameters, long-term (fs-year) defect generation and evolution are simulated in a large system (up to μm) to obtain time/temperature-dependent concentrations of surviving deep-level defects after irradiation and annealing, by coupling the Monte Carlo (MC) and object kinetic MC (OKMC) methods (see Irradiation and annealing simulations in “Methods” section). Here, defect generation under irradiation is simulated with our self-developed open-source MC code, IM3D25, using the energy spectrum of primary knock-on atoms (PKAs) calculated by Geant436 as inputs. For defect evolution, we consider defects and impurities with different charge states and their corresponding dynamic processes. Thirdly (Fig. 1c), based on the obtained multidimensional defect properties, the DLTS of semiconductor devices are obtained by simulating carrier capture and emission of crucial deep-level defects in the sensitive area at different temperatures, using our improved rate theory model based on the Shockey-Read-Hall (SRH) theory37,38 (see DLTS simulations in “Methods” section). More importantly, based on the annealed defect spatial distributions, we have constructed an effective polarized region model to obtain the improved intra-cascade electrostatic potential without adjustable parameters to correct carrier densities in the rate equations39. Finally (Fig. 1d), defect identification is achieved by using our proposed peak-level matching (PLM) algorithm (see Peak-level matching algorithm in “Methods” section).

a Calculation of defect parameters including formation energies, energy levels, carrier capture cross-sections and migration energies by the density functional theory. The orange and light blue regions represent the conduction and valence bands, respectively. b Irradiation and annealing simulations by combining our self-developed Monte Carlo (MC) and object kinetic MC methods to acquire annealed defect concentrations. The inset shows the complex dynamic processes of defects and carriers (electrons and holes) in semiconductors under irradiation, including the migration and drift of mobile defects and carriers, the generation of self-interstitials (Is) and vacancies (Vs), the I-V and electron-hole recombination, the formation and break-up of impurity-point-defect pairs, the trapping and detrapping of I/V clusters and their complex clusters with impurities, and the electron/hole capture and emission of charged defects. The unfilled, black filled and red filled circles are represented by vacancies, self-interstitials and impurities, respectively. c Deep-level transient spectroscopy (DLTS) simulations by our improved rate theory model based on the Shockey-Read-Hall theory. t1 and t2 are determined by the rate window of DLTS experiments. d Determination of crucial deep-level defects through matching simulated and experimental DLTS peaks using our self-developed peak-level matching algorithm (Experimental data is reproduced from ref. 33). FWHM represents the Full Width at Half Maximum of a DLTS peak.

Modeling framework verification: neutron-irradiated Si

Si is a benchmark semiconductor with sufficient theoretical and experimental investigations. The typical deep-level defects under irradiation have been clearly determined in previous research. Among them, divacancies (V2) often act as the most important carrier recombination/generation centers, causing the decrease in gain of bipolar transistors and the increase in leakage current of detectors5,40. Here, we present the general process of defect identification and verify our multiscale modeling framework, through simulating the DLTS of neutron-irradiated Si and then matching it with the experimental base-collector of a 2N2222 n-p-n type Si bipolar transistor (see Fig. S2a) after pulsed neutron irradiation with the fluence of 1014 cm–2 at 300 K and thermal annealing at 350 K33.

The overall process of identification of deep-level defects in neutron-irradiated Si is shown in Fig. 2. First, staring from the PKA energy spectrum35, we performed MC and OKMC simulations of neutron irradiation and thermal annealing to acquire the evolution of different types of defects (Fig. 2a). Remarkably, the main surviving defects after annealing are defect complexes rather than single-point defects, including VO, I2, V2, I3, V3, OI and CI, with their numbers decreasing in order. The concentrations of these defect complexes in unirradiated Si are negligible, even below the intrinsic carrier density, indicating that the static defect theory is very challenging to catch the key defects in non-equilibrium. The spatial distributions of different types of surviving defects in the steady state are shown in Fig. 2b. Interestingly, opposite to the common assumption of a uniform distribution of defects in the system, the distributions of surviving defects are strongly inhomogeneous. They form separated defect-aggregation regions. The carrier capture of aggregated defects will cause the formation of the electrostatic potential energy barrier to hinder the transport of free carriers, thus resulting in changes in semiconductor electrical properties.

a Evolution in numbers of different types of defects during neutron irradiation at 300 K (the shaded region) and annealing at 350 K (the unshaded region). b Defect spatial distribution in a one-micrometer cube in the steady state after neutron irradiation and annealing. c Energy levels and surviving numbers per cascade of the concerned deep-level defects after neutron irradiation and annealing. d Time-dependent charge-state conversion ratios (solid lines) and potential energy barriers (the red dashed line) by electron capture in Process Ⅱ (the light green region), and time-dependent charge-state conversion ratios (solid lines) by electron emission in Process Ⅲ (the light yellow region) at different temperatures for V2(=/−). The dashed lines between two color regions indicate the time break. e Simulated and experimental DLTS of the base-collector of the Si bipolar transistor after neutron irradiation and annealing (Experimental data is reproduced from ref. 33). The explanations of all defect notations can be found in Irradiation and annealing simulations in “Methods” section.

Secondly, according to the numbers of these surviving defects and their energy levels, we obtained the concerned defect levels (Fig. 2c) that may contribute to DLTS signals including CI(−/0), VO(−/0), V2(−/0), V2(=/−), V3(−/0) and V3(=/−). The electron capture and emission for these concerned levels in Processes Ⅱ and Ⅲ (see DLTS simulations in “Methods” section) are simulated, taking the time-dependent charge-state conversion ratios for V2(=/−) as an example (Fig. 2d). The V2(=/−) level is not completely occupied by electrons, due to the existing electrostatic potential energy barrier (see the dashed line in Fig. 2d). The incomplete occupation of V2(=/−) will cause the decrease in initial defect concentration in Process Ⅲ and thus the decrease in intensity of the DLTS signal of V2(=/−), resulting in the stronger DLTS signal of EC − 0.44 eV than that of EC − 0.24 eV33,41,42. It also strongly indicates the important role of the accurate intra-cascade electrostatic potential in describing DLTS, which is largely underestimated in previous research22,23,24. Finally, according to the experimental rate window (232 s−1)33, t1 and t2 were taken as 2.08 × 10–4 and 2.08 × 10–3 s, respectively, as shown by the black dashed line. We thus calculated the DLTS signals of all defect levels (the dashed line in Fig. 2e) according to Eq. (1) in “Methods”. Summing the signals of all levels, we eventually obtained the simulated DLTS of the base-collector of Si bipolar transistor after neutron irradiation and annealing (solid-line in Fig. 2e). Overall, the simulated DLTS is well consistent with the experimental one33 (circles in Fig. 2e). The five experimental peaks can thus be clearly identified as CI(−/0), VO(−/0), V2( = /−), V3(=/−), and the superposition of V2(−/0) and V3(−/0), respectively. It is consistent with the current understanding43,44, indicating that our method can achieve unambiguous identification of crucial deep-level defects in Si without any biased assumptions.

Modeling framework advantages: neutron-irradiated 4H-SiC

SiC is widely recognized as one of the most important wide-bandgap semiconductors for applications in high-temperature, high-frequency, high-power, and extreme irradiation conditions. However, in 4H-SiC, one of the most superior polytypes of SiC, many crucial defect levels have been under debate for decades, preventing the improvement of device performances via defect engineering. Here, the advantages of our modeling framework are given by identifying the crucial deep-levels in a 4H-SiC SBD (Fig. S2b) after 14 MeV neutron irradiation with the fluence of 7.28 × 1012 cm-2 and annealing at 300 K.

Similarly, based on the C and Si-PKA energy spectra (Fig. S3a), we obtained the evolution behaviors (Fig. 3a) and spatial distributions (Fig. 3b) of different types of defects at a typical time of months in 4H-SiC during neutron-irradiation and annealing at 300 K. The annealed defects mainly include mono-interstitials, di-interstitials, mono-vacancies, di-vacancies, and anti-site defects. According to DFT calculations, the concerned deep levels are shown in Fig. 3c. Then, we simulated electron capture and emission for these concerned levels in Processes Ⅱ and Ⅲ (see DLTS simulations in “Methods” section) of DLTS experiments, respectively. Due to very small electron capture cross-sections (Table S3), CI(−/0), CI(=/−), CICI(−/0) and CICI(=/−) levels are almost unoccupied in Process Ⅱ, not contributing to any DLTS signals. The capture and emission of other levels in 4H-SiC behave similarly as the levels except for the partially occupied V2(=/−) in Si, thus not presented here. Finally, according to the experimental rate window of 4.1 s-1, we obtained the DLTS signals (the dashed line in Fig. 3d) of all concerned levels in neutron-irradiated 4H-SiC. Summing the output signals of all these levels, we obtained the simulated DLTS of neutron-irradiated 4H-SiC (the black solid line in Fig. 3d). The positions of three simulated peaks slightly deviate from the experimental ones, which is mainly caused by neglecting the temperature-dependence of energy levels and capture cross-sections. By comparing the simulated DLTS with the experimental one, we achieved the identification of deep levels in 4H-SiC, which is one of the key steps to improve device performance via accurate defect passivation in the future. Meanwhile, our method exhibits two advantages over previous ones:

-

1).

Unambiguous identification of typical deep levels. The first advantage is the power of unambiguous identification of typical deep levels. Through DLTS experiments (see Experiments section), we can detect four DLTS peaks at about 200, 300, 370 and 425 K corresponding to EH1/S1, Z1/2, EH3/S2, and EH4 levels6,7,8, respectively. Previously, through numerous experimental and theoretical studies, Z1/2 was assigned as VC( = /0), EH1/S1 and EH3/S2 were assigned as the different levels of the same defect like VSi or CI45,46,47, and EH4 was assigned as the divacancy or CSiVC (CAV)48,49. Here, we identified Z1/2 as VC( = /0), which is consistent with previous research9. In addition, we newly identified EH1/S1, EH3/S2, and EH4 levels as VCVC( = /−), VCVC(−/0) and VSi(=/−), respectively. Due to much smaller electron capture cross-sections (Table S3) of interstitial-type defects (< 10-20 cm2) than those of vacancy-type defects (>10-15 cm2), interstitial-type defects could not be detected by DLTS. Moreover, due to the relatively small threshold displacement energy for the C atom, less than half of that for the Si atom50, more C-relative defects like VC, CI and VCVC than Si-relative defects should form in irradiated 4H-SiC, which proves our identification.

-

2).

Prediction of high-temperature DLTS peaks. The second advantage is the prediction ability of peaks that are not detected by DLTS at high temperatures. Here, four DLTS peaks have been detected below 500 K. Using our modeling framework, we can predict one new DLTS peak (green dashed line in Fig. 3d) at about 570 K that is out of the experimental temperature range. This peak is also detected by other DLTS experiments, which corresponds to the EH6 level6,51 with the activation energy of about 1.55 eV. Our simulations showed that EH6 should be contributed by VSiVC(=/0), which is consistent with the current speculation that the EH6 level is associated with a complex involving VC47,52,53, respectively. The unambiguous identification of this level will be presented in the following part.

a Evolution in numbers of different species of defects during neutron-irradiation and annealing at 300 K. b Defect spatial distribution in a one-micrometer cube at the time scale consistent with the experiment. c Energy levels and numbers per cascade of the concerned deep-level defects. d Simulated and experimental DLTS of the 4H-SiC SBD after neutron irradiation and annealing, acquired by our modeling framework and experimental measurements, respectively. The explanations of all defect notations can be found in Irradiation and annealing simulations in methods section.

Multidimensional identification of deep levels in semiconductors

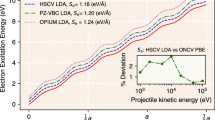

Again, taking 4H-SiC as an example, we further applied our modeling framework to understand deep-level defects in semiconductors in equilibrium and various nonequilibrium conditions with multidimensional parameters. In equilibrium, the dominating deep level in 4H-SiC is commonly considered as Z1/2. With two-dimensional parameters \((\Delta E,\sigma )\) of the defect level and carrier capture cross-section, we can simulate DLTS peaks of 4H-SiC in equilibrium (Fig. 4a). The dominating deep level of VC( = /0) corresponding to VC with the low formation energy of 1.3 eV is the origin of Z1/2 (see Column Ⅰ in Table 1).

DLTS of 4H-SiC in equilibrium (a) and nonequilibrium (b) with two-dimensional parameters of \((\Delta E,\sigma )\). c,d DLTS of a 4H-SiC JBS diode after 1 MeV neutron irradiation with the fluence of 6.6×1013 cm-2 and annealing at 300 K with three-dimensional parameters of \((\Delta E,\sigma,C)\) (c) at 623 K with the extra dimensional parameter of T (d). Here, the experimental DLTS of the 4H-SiC JBS diode is taken from ref. 7. Defect evolution during annealing at 300 (e) and 623 K (f). Two stages of evolution occur for both temperatures: (Ⅰ) athermal defect reactions, including I-V recombination and cluster formation like VCVC and VSiVC, and (Ⅱ) thermal defect reactions, including I-V recombination and clustering. An extra stage (Ⅲ) of defect evolution occurs at 623 K, that is, the formation of antisite defects including CSi and CSiVC (CAV). The thicker dashed lines are used to highlight the defects that appear (CSi and CAV) or disappear (VSi) at the higher annealing temperature. The explanations of all defect notations can be found in Irradiation and annealing simulations in “Methods” section.

Assuming the normalized concentrations of different types of defects, we can simulate a group of possible DLTS peaks with \((\Delta E,\sigma )\) in nonequilibrium states (Fig. 4b). Compared to that in equilibrium, much more peaks would appear in DLTS. In particular, some peaks overlap with each other, causing great difficulties in the identification of deep-level defects (see Column Ⅱ in Table 1).

To unambiguously pick out crucial deep levels in nonequilibrium from the large defect-level group shown in Fig. 4b, a new dimension of defect concentration (C) must be introduced to determine the intensities of different DLTS peaks. Therefore, we further simulated the DLTS of neutron-irradiated 4H-SiC after annealing at 300 K with \((\Delta E,\sigma,C)\), as shown in Fig. 4c. Compared to the peaks in Fig. 4b, some peaks corresponding to the levels like CAV(−/0) and SiCVSi (−/0) vanish in the simulated DLTS, due to their very low concentrations. The left peaks with different intensities are contributed by other crucial deep levels with different concentrations. Overall, the simulated DLTS is consistent with the experimental one. By using the PLM algorithm, the deeper EH6 level mentioned above can be unambiguously identified as VSiVC(=/0) (see Column Ⅲ in Table 1).

However, the S1, S2, and EH5 levels are still not determined due to their low defect concentrations and thus weak intensities of DLTS peaks. It is found that the intensities of DLTS peaks corresponding to these levels rely on irradiation and annealing conditions, especially for annealing temperatures (T). To clarify the influence of annealing temperatures on the intensities of DLTS peaks, we further simulated the DLTS of neutron-irradiated 4H-SiC after annealing at 623 K (Fig. 4d). Interestingly, the pattern of DLTS after annealing at 623 K is similar to that at 300 K (Fig. 4c), but the defect origins contributing to these DLTS peaks vary obviously. S1, S2, and EH5 levels appear due to the appearance of CAV and disappearance of VSi, which are contributed by CAV(=/−), CAV(−/0) and CAV(0/+), respectively, while the EH4 level contributed by VSi(=/−) disappears. We thus unambiguously identify all typical deep levels in 4H-SiC, including EH1/S1, Z1/2, EH3/S2, EH4, EH5, and EH6. All these deep levels that appear in the DLTS of 4H-SiC devices are thus determined unambiguously, as listed in Column IV of Table 1. Clearly, our multidimensional DLTS modeling framework for unambiguous defect identification is necessary to determine deep levels in complex semiconductors under different growth, irradiation or annealing conditions.

Expanded understanding of defect physics in nonequilibrium

Based on the above discussion, we can eventually expand understandings of defect properties in nonequilibrium in two aspects, dramatically differing from those in equilibrium. First, for defect properties in nonequilibrium, it is generally thought that the dominating crucial deep-level defects should still be the ones with relatively low formation energies in equilibrium. However, our results show that the crucial deep-level defects in 4H-SiC under irradiation (a typical nonequilibrium state) include not only point defects with relatively low formation energies like VC (<5.0 eV) but also vacancy-type clusters with much high formation energies like VCVC, VSiVC and CAV (up to 10 eV). Again, it indicates great limitations of the static defect theory when applied to nonequilibrium states.

Secondly, it is generally thought that the types of crucial deep-level defects remain almost the same at different growth, irradiation, and annealing conditions18,49,54. However, our simulation results show that the types and concentrations of crucial defects in neutron-irradiated 4H-SiC vary significantly at different annealing temperatures. Especially, CAV is almost absent at 300 K, while it appears at 623 K, mainly caused by different defect evolution stages. At 300 K, there are two stages, athermal and thermal, leading to I-V recombination and cluster formation (see Fig. 4e). Whereas there are three stages at 623 K (see Fig. 4f), with an extra formation process of CAV. The details of defect evolution at 300 and 623 K can be found in Fig. S4. Moreover, VSi exists at 300 K but vanishes after annealing at 623 K (see Fig. 4e, f), due to the more violent I-V recombination at the higher temperature. Therefore, annealing at different temperatures will cause the significant difference in defect properties including type, concentration and dynamic behavior.

Discussion

A multiscale modeling framework has been constructed for the unambiguous identification of deep-level defects, through matching the simulated DLTS with the experimental ones. In this framework, a multiscale method is developed by coupling DFT for the calculations of defect parameters with MC and OKMC for the simulation of long-term (up to year) and large-scale (up to μm) radiation damage in semiconductors. In addition, a rate theory model is improved based on the SRH theory for accurate DLTS simulations with multidimensional defect properties. Our modeling framework thus presents two advantages of unambiguous identification of typical deep-levels and prediction of high-temperature DLTS peaks. In addition, we note that our multiscale modeling cannot involve different configurations for cluster defects, although the KMC method used here has been one of the most effective approaches for simulating long-term defect dynamics evolution in large-scale systems after irradiation and annealing. But we still considered all configurations of cluster defects in DFT calculations and tried to take into account all the key defects and clusters as completely as possible by introducing their most stable configurations into KMC modeling of defect evolution.

Using this modeling framework, we are able to identify all typical deep-levels that are highly either unknown or controversial in 4H-SiC detected by DLTS. We found that besides point defects with relatively low formation energies, the crucial deep-level defects with relatively high formation energies can also form in 4H-SiC under irradiation. The crucial deep-level defects are mainly vacancy-related defects in neutron-irradiated Si and 4H-SiC. In practice, the device radiation resistance can be improved by removing these key defects. For example, it can be achieved through increasing I-V recombination by reducing defect migration energies and annihilating vacancies by introducing harmless impurities. Our defect identification will provide a foundation for the precise defect passivation in the future. Moreover, we found that the change in defect type due to different defect dynamic behaviors at different annealing temperatures can result in various defect origins for the same DLTS peak. These findings break the long-standing understanding of defect behaviors in nonequilibrium.

The proposed modeling framework is of good scalability and universality for the identification of deep-level defects in more complex semiconductors like gallium nitride and gallium oxide. The unambiguous identification of deep-level defects is the indispensable step to further improve device performances for specific applications like deep-space exploration, nuclear energy, or semiconductor fabrication. In practice, our model could also be applied to capture the evolution of nitrogen-vacancy in diamond55 under different irradiated conditions, providing a basis for designing controllable quantum qubits. Moreover, based on our modeling framework, the crucial semiconductor parameters like minority carrier lifetime can be calculated accurately. More spectroscopy related to defects like photoluminescence spectroscopy could also be replicated. Our modeling framework and findings can bridge the gap between the microscopic defect behaviors and macroscopic material properties, promoting the development of defect theories in nonequilibrium.

Methods

DFT calculations

For the DFT calculations of 4H-SiC, the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)56 was employed. The exchange-correlation energy was treated with the screened HSE06 hybrid density functional57,58. The plane-wave cutoff for the wavefunction expansion was set to 400 eV. A sufficient k-points were selected for integrations over the Brillouin zone for the 4 × 4 × 1 supercell (128 atoms). During the structural relaxations, a conjugate-gradient algorithm was used until the force on each atom was lower than 0.01 eV Å−1, and the total energy was converged to 1.0 × 10–5 eV. Moreover, the spin-polarized calculations were considered for all the defects in 4H-SiC. The Climbing Image Nudged Elastic Band method59 was adopted to calculate the migration energies. The total energy and the force on each atom converged to <1.0 × 10−5 eV and <0.02 eV Å−1, respectively.

We note that given the substantial computational cost associated with defect pairs in SiC, we initially perform structural relaxations using the GGA-PBE functional with a 2 × 2 × 2 k-point grid. Subsequently, static calculations of total energy and eigenvalue are carried out using the HSE hybrid functional at the single Γ-point. This approach effectively reduces errors in formation energies and transition levels caused by the bandgap underestimation while keeping the overall computational cost affordable60.

For the electron/hole capture cross-section calculations, the newly developed theoretical calculation method with multi-phonon emissions30,31 and static approximations59 was used. It has been implanted in PWmat60,61, in which force constant matrices, phonon density of states, and electron–phonon coupling coefficients can be calculated to obtain the carrier capture rate constants.

Irradiation and annealing simulations

DLTS experiments generally characterize the properties of the deep-level defects in the sensitive area of semiconductor junctions (such as p-n or Schottky junctions), not in the whole device13,14. For simplification, in the simulation of defect generation and evolution during neutron irradiation and annealing, we thus focus on the sensitive area instead of a complete semiconductor device. The sensitive area is the collector for the base-collector of the n-p-n type Si bipolar transistor and the semiconductor side for the Schottky diodes, as illustrated in DLTS simulations.

Using the energy spectra of primary knock-on atoms (PKAs) as input, the generation of primary point defects under neutron irradiation is simulated with our self-developed open-source MC code, IM3D25, with high accuracy (close to that of Molecular Dynamics) and efficiency (4 orders of magnitude higher than that of SRIM62). The PKA energy spectra are taken from the work of Myers et al.35 for Si and calculated by Geant436 for 4H-SiC, respectively. The PKA energy spectra for 4H-SiC under 14 and 1 MeV neutron irradiation can be found in Fig. S3a and Fig. S3b, respectively. Primary recoil atoms were randomly sampled from the PKA energy spectra, placed in the center of the IM3D simulation box with random directions, and then traced their detailed cascade trajectories. The 3D spatial distributions of primary point defects can thus be acquired through the ‘Full Cascade’ option with the displacement threshold energy of 20 eV for Si63, and that of 20 eV (C) and 35 eV (Si) for 4H-SiC50,64. The spatial distributions of primary point defects are thus provided as an initial database of collision cascades for subsequent modeling of defect evolution.

For defect evolution, the defects in Si include the intrinsic point defects (self-interstitial I and vacancy V), and their clusters (In, Vn and InVm), the substitutional dopant (phosphorus P) and impurities (carbon C and oxygen O), impurity-point-defect pairs (PI, PV, CI, CV, VO and OI), and the complexes of carbon atoms and interstitials (CnIm). The typical structures and properties of these defects can be found elsewhere35,65,66,67,68. The defects in 4H-SiC include the intrinsic point defects (carbon vacancy VC, carbon interstitial CI, silicon vacancy VSi, silicon interstitial SiI, silicon anti-site SiC and carbon anti-site CSi), their typical double-defect clusters (VCCI, VSiSiI, VCSiI, VSiCI, VCVC, VSiVC, VSiVSi, CICI, SiICI, SiISiI, CSiVC, CSiCI, CSiSiI, SiCVSi, SiCCI, SiCSiI, and SiCCSi) and the dopant (substitutional and interstitial nitrogen, NC and NI). The structures of all these defects can be found in Figure S1. Defect parameters mainly include energy levels, carrier capture cross-sections, migration energies of mobile defects and binding energies of defect clusters. Defect reaction events mainly include I-V recombination, defect-pair formation and break-up, and cluster growth and dissociation. Defect parameters and reaction events for Si and 4H-SiC are listed in Tables S1–S4. Based on these parameters, the evolution of charged defects and carriers is simulated with the open-source OKMC code, MMonCa69, using the spatial distributions of primary point defects as the database of initial collision cascades. The initial collision cascades were placed at the center of the MMonCa simulation box. The dopant and impurities were randomly placed into the simulation box in the substitutional form according to the measured concentrations (3.0 × 1017 cm–3 for O, 3.0 × 1016 cm–3 for C and 9.0 × 1014 cm–3 for P in Si as well as 1.439 × 1014 cm–3 for N in 4H-SiC). More specifically, a uniform random number between 0 and 1 in each sampling is generated to obtain the position of the dopant and impurities in the simulation box, according to the size of the box. If the position obtained from one sampling coincides with that of the previous positions, resampling is performed until no overlap occurs. Only one cascade was randomly sampled and modeled at each simulation for simplification, because radiation-induced collision cascades nearly do not overlap under the relatively low neutron fluences here. Thousands of cascades are simulated and statistically averaged to reduce errors.

DLTS simulations

According to the principle of DLTS13,14, charge carriers (electrons or holes) can occupy defect energy levels within the bandgap (carrier capture), and can also be emitted from them to the conduction or valence band (carrier emission). When conducting a DLTS experiment, a constant reverse bias voltage and a constant periodic forward pulse voltage are applied to a semiconductor junction (p-n or Schottky junction) with deep-level defects, at different temperatures. Thus, three processes will happen in the semiconductor junction circularly: (Process Ⅰ) The semiconductor junction is in the reverse bias state, and defect energy levels are almost empty. (Process Ⅱ) The forward voltage is applied to the semiconductor junction, and then carriers rapidly occupy defect energy levels. (Process Ⅲ) The forward voltage is released, and then carriers are gradually emitted from defect energy levels and expelled from the junction due to the existing reverse voltage, causing changes in the junction capacitance. When the forward voltage is applied and released circularly, the carrier capture and emission of deep-level defects will also be cycled in the junction. With increasing temperature, deeper defect energy levels will be activated and detected. DLTS experiments measure temperature-dependent differences in junction capacitances between two moments t1 and t2 (t1 < t2) that are determined by the experimental rate window in Process Ⅲ. For a one-sided abrupt p-n junction or Schottky junction under a reverse bias voltage, carrier capture and emission mainly occur in the sensitive area, that is, the space charge region on the side of the semiconductor junction with a high Fermi level. This space charge region is the n-type side for the p-n junction and the semiconductor side for the Schottky junction. Therefore, the output signal of DLTS corresponding to a defect energy level can be generally given by ref. 70,

Here \(\Delta {C}_{12}^{\pm }(T)\) is the difference in capacitance at t1 and t2 after releasing the forward voltage for the minority (+) and majority (–) carrier traps at temperature T, respectively. \({C}_{0}\) is the junction capacitance at the steady state after releasing the forward voltage. \({N}_{{{{\rm{dop}}}}}\) is the dopant concentration in the lightly doped side for a p-n junction or in the semiconductor side for a Schottky junction. \({N}_{{{{\rm{def}}}}-{{{\rm{o}}}}}(t,T)\) is the concentration of the concerned defect in the sensitive area whose energy levels are occupied by carriers at time t and temperature T in Process III. The only unknown \({N}_{{{{\rm{def}}}}-{{{\rm{o}}}}}(t,T)\) can be determined by simulating the carrier capture and emission of different types of deep-level defects at different temperatures in Processes Ⅱ and Ⅲ. The carrier capture and emission can be generally described by the rate equation based on the SRH theory that37,38,

Here, \({{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}}\) and \({{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1}\) represent the defect X with the charges of j and \({{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1\), respectively. N represents the defect concentration. \({\nu }_{{{{\rm{th}}}}}={(3{k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T/{m}{\ast })}^{1/2}\) is the thermal velocity of carriers with the Boltzmann constant kB, the temperature T and the effective mass \({m}{\ast }\). \({\sigma }_{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}}}\) is the carrier capture cross-section of the defect \({{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}}\). n is the carrier density. \({N}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}/{{{\rm{V}}}}}=2{(2 \pi {{m}\ast}_{\!\!\!{{{\rm{e}}}}/{{{\rm{h}}}}}{k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T/{h}^{2})}^{3/2}\) is the effective density of states in the conduction/valence band with the electron/hole effective mass \({{m}\ast}_{\!\!\!{{{\rm{e}}}}/{{{\rm{h}}}}}\) and the Planck constant h. \(\Delta {E}_{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1}}\) represents the activation energy of carrier emission of the defect \({{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1}\).

Here, based on Eq. (2), we developed an improved model to simulate carrier capture and emission in Processes Ⅱ and Ⅲ for DLTS simulations. In Process Ⅱ, the rate of carrier capture is larger than that of carrier emission. As mentioned above, the carrier capture (net capture) of deep-level defects within localized cascades will cause the formation of a complex time-dependent surrounding electrostatic potential. A time-dependent electrostatic potential energy barrier \({E}_{{{{\rm{peb}}}}}(t)\) thus form, which can inhibit the carrier capture and cause incomplete occupation of defect energy levels, eventually affecting the intensities of simulated DLTS signals. In previous studies, there are many shortcomings in solving the complex electrostatic potential33,35. Here, we have acquired an improved intra-cascade electrostatic potential without adjustable parameters, via a proposed effective polarized region model based on the more reasonable annealed defect distributions from OKMC simulations39. We have introduced the improved intra-cascade electrostatic potential to correct the carrier density in Eq. (2), that is, \(n(t)={n}_{0}\exp (-{E}_{{{{\rm{peb}}}}}(t)/{k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T)\), where \({n}_{0}\) is the carrier density in unirradiated semiconductors. The improved rate equation describing the charge state transition of the defect X from j to \({{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1\) by hole (+)/electron (–) capture at different temperatures is thus given by ref. 39,

Here \({N}_{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}}}^{{{{\rm{cap}}}}}\) and \({N}_{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1}}^{{{{\rm{cap}}}}}\) represent the average concentrations of the defect X with j and \({{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1\) charges within cascades, respectively.

In Process Ⅲ, carrier capture can be ignored because carriers can almost be expelled from the semiconductor junction, as mentioned above. Thus, Eq. (2) can be simplified to describe carrier emission as,

where \({N}_{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1}}^{{{{\rm{emi}}}}}\) represents the concentrations of the defect X within cascades with \({{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1\) charges, which equals \({N}_{{{{\rm{def}}}}-{{{\rm{o}}}}}\) in Eq. (1). Generally, the duration of the forward pulse voltage is long enough to reach the equilibrium state of carrier capture. Thus, the initial value of defect concentration in Eq. (4) can be set as \({N}_{{{{{\rm{X}}}}}^{{{{\rm{j}}}}\pm 1}}^{{{{\rm{cap}}}}}(t\to \infty )\) that can be obtained by solving Eq. (3).

Here, based on the improved model for DLTS simulations mentioned above, we have developed a module of C code, IRadMat-DLTS, to simulate DLTS of semiconductors. The lsoda solver71 of the C version was employed for the rate equations. The charge state transitions of the concerned defect energy levels by carrier capture and emission for Si and 4H-SiC were simulated one by one with the temperature interval of 5 K. The simulated DLTS was thus acquired by summing DLTS intensities of all energy levels for Si or 4H-SiC.

Peak-level matching algorithm

In our modeling framework, a peak-level matching algorithm is used to match defect levels with the experimental DLTS peaks for defect-identification. The fundamental flow for the algorithm is as follows:

-

1).

Read the data of experimental DLTS and the property parameters (position, carrier capture cross-section and concentration) of all defect levels.

-

2).

Determine the position, Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) and intensity of each experimental DLTS peak.

-

3).

Give the confidence intervals for all property parameters to determine the confidence intervals of position, FWHM and intensity for each simulated DLTS peak.

-

4).

Give a search scheme to select possible defect levels matching with one experimental DLTS peak, and a match criterion to determine whether the total DLTS peak summed by the simulated sub-peaks of possible levels is consistent with the experimental one.

-

5).

Search for possible match defect levels for each experimental peak from low to high temperatures according to the search scheme. If only one level matches with one experimental peak, this level is determined to be the only contribution to this peak. Otherwise, an extra most-close defect level is added to the list of possible levels.

-

6).

Calculate the total DLTS peak according to the property parameters of possible levels. If the match criterion is satisfied for this experimental peak, both of these possible levels contribute to this experimental peak. Otherwise, another most-close level is added to the list of possible levels and the new total DLTS peak is recalculated until the match criterion is satisfied. If the match criterion is still not satisfied when all possible levels have been added, adjust the search scheme and match criteria and repeat steps 5–6.

-

7).

Repeat steps 5–6 until the matching of all experimental DLTS peaks is finished.

Based on the peak-level matching algorithm, we have developed a module of C code, IRadMat-PealMat. In this code, the self-developed IRadMat-DLTS (see DLTS simulations section) is used to obtain the simulated DLTS peak according to the property parameters of defect levels.

Experiments

4H-SiC SBD fabrication

The 4H-SiC Schottky Barrier diode (SBD) was fabricated of unintentional doping epitaxial 4H-SiC material with the nitrogen (N) doping concentration of 1.439 × 1014 cm–3 determined by capacitance-voltage measurements. The epitaxial 4H-SiC material is grown by Chemical Vapor Deposition on commercial 4H-SiC N+ conducting substrate wafers. The front Schottky electrode is a nickel (Ni) electrode made by thermal vacuum evaporation. Silica and silicon nitride are used to protect the Schottky barrier. The back ohmic contact electrode is Ni/Au and annealed at 900 °C in a N2 atmosphere. The schematic diagram of the 4H-SiC SBD can be found in Fig. S2b.

Neutron irradiation

The 4H-SiC SBD was irradiated by Deuterium-Tritium fusion neutrons with the energy of 14 MeV on the K600 neutron generator in China Institute Atomic Energy (CIAE) in Beijing at room temperature. The total irradiation fluence reaches 7.28 × 1012 n/cm2 with the irradiation dose rate of about 7.78 × 107 n/(cm2·s).

DLTS measurements

The DLTS measurement was performed on one neutron-irradiated 4H-SiC SBD sample by using the Semetrol DLTS test system with the test temperatures from 50 to 500 K. The reverse bias VR and the filling pulse voltage Vf were set as –3.5 and 1 V, respectively. The filling pulse duration was set as 50 μs to ensure saturation filling of traps. Prior to the measurements, the 4H-SiC SBD sample was cooled down from room temperature to 50 K without the applied bias. Then, the temperature of the sample was increased slowly with the temperature ramp rate of 2 K/min. The capacitance transient measurement was performed with the temperature interval of about 5 K.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article or from the corresponding authors upon request. The atomic coordinates of defects after structure optimization by DFT calculations and after annealing by KMC modeling are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30052528.v2. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes and software used for DFT calculation including VASP and PWmat are openly available online from the corresponding developer and maintainer. The open-source code, MMonCa, is available at https://github.com/MMonCa/MMonCa.git. The self-developed codes in this work are available at http://physics.issp.ac.cn/IM3D or from the corresponding authors upon request.

Change history

05 February 2026

In the version of this article initially published, the grants listed in the Acknowledgements did not lead with thanks to the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Acknowledgements inadvertently omitted Tianhe-JK at CSRC, as is now amended in the HTML and PDF versions of the article.

References

Prinzie, J., Simanjuntak, F. M., Leroux, P. & Prodromakis, T. Low-power electronic technologies for harsh radiation environments. Nat. Electron. 4, 243–253 (2021).

Huang, Q. & Jiang, J. An overview of radiation effects on electronic devices under severe accident conditions in NPPs, rad-hardened design techniques and simulation tools. Prog. Nucl. Energy 114, 105–120 (2019).

Srour, J. R. & Palko, J. W. Displacement damage effects in irradiated semiconductor devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 60, 1740–1766 (2013).

Queisser, H. J. & Haller, E. E. Defects in semiconductors: Some fatal, some vital. Science 281, 945–950 (1998).

Moll, M. Displacement damage in silicon detectors for high energy physics. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 65, 1561–1582 (2018).

Alfieri, G., Monakhov, E. V., Svensson, B. G. & Hallén, A. Defect energy levels in hydrogen-implanted and electron-irradiated n-type 4H silicon carbide. J. Appl. Phys. 98, 113524 (2005).

Hazdra, P., Záhlava, V. & Vobecký, J. Point defects in 4H–SiC epilayers introduced by neutron irradiation. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 327, 124–127 (2014).

Sasaki, S., Kawahara, K., Feng, G., Alfieri, G. & Kimoto, T. Major deep levels with the same microstructures observed in n-type 4H–SiC and 6H–SiC. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 013705 (2011).

Son, N. T. et al. Negative-U system of carbon vacancy in 4H-SiC. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 187603 (2012).

Alfieri, G. & Kimoto, T. Laplace transform deep level transient spectroscopy study of the EH6/7 center. Mater. Sci. Forum 740-742, 645–648 (2013).

Alkauskas, A., McCluskey, M. D. & Van de Walle, C. G. Tutorial: Defects in semiconductors—Combining experiment and theory. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 181101 (2016).

Tuomisto, F. & Makkonen, I. Defect identification in semiconductors with positron annihilation: Experiment and theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1583–1631 (2013).

Lang, D. V. Deep-level transient spectroscopy: A new method to characterize traps in semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 45, 3023 (1974).

Peaker, A. R., Markevich, V. P. & Coutinho, J. Tutorial: Junction spectroscopy techniques and deep-level defects in semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 123, 161559 (2018).

Bathen, M. E. et al. Characterization methods for defects and devices in silicon carbide. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 140903 (2022).

Wickramaratne, D. et al. Defect identification based on first-principles calculations for deep level transient spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 192106 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Effect of electron irradiation and defect analysis of β-Ga2O3 Schottky barrier diodes. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 71, 1676–1680 (2024).

Polyakov, A. Y. et al. Deep level defect states in β-, α-, and ɛ-Ga2O3 crystals and films: Impact on device performance. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 40, 020804 (2022).

Farzana, E., Chaiken, M. F., Blue, T. E., Arehart, A. R. & Ringel, S. A. Impact of deep level defects induced by high energy neutron radiation in β-Ga2O3. APL Mater. 7, 022502 (2019).

Scheinemann, A. & Schenk, A. TCAD-based DLTS simulation for analysis of extended defects. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 211, 136–142 (2014).

Lauwaert, J. Technology computer aided design based deep level transient spectra: simulation of high-purity germanium crystals. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 55, 085101 (2022).

Kuhnke, M. The long-term annealing of the cluster damage in high resistivity n-type silicon. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 49, 2599–2604 (2002).

Nyamhere, C. et al. Electrical characterisation and predictive simulation of defects induced by keV Si+implantation in n-type Si. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 184508 (2013).

Xu, X. et al. To define nonradiative defects in semiconductors: An accurate DLTS simulation based on first-principle. Comput. Mater. Sci. 215, 111760 (2022).

Li, Y. G. et al. IM3D: A parallel Monte Carlo code for efficient simulations of primary radiation displacements and damage in 3D geometry. Sci. Rep. 5, 18130 (2015).

Hehr, B. D. Analysis of radiation effects in silicon using kinetic Monte Carlo methods. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 61, 2847–2854 (2014).

Wampler, W. R. & Myers, S. M. Model for transport and reaction of defects and carriers within displacement cascades in gallium arsenide. J. Appl. Phys. 117, 045707 (2015).

Martin-Bragado, I., Borges, R., Balbuena, J. P. & Jaraiz, M. Kinetic Monte Carlo simulation for semiconductor processing: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 92, 1–32 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ionization-induced annealing of pre-existing defects in silicon carbide. Nat. Commun. 6, 8049 (2015).

Shi, L. & Wang, L. W. Ab initio calculations of deep-level carrier nonradiative recombination rates in bulk semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 245501 (2012).

Shi, L., Xu, K. & Wang, L.-W. Comparative study of ab initiononradiative recombination rate calculations under different formalisms. Phys. Rev. B 91, 205315 (2015).

Freysoldt, C. et al. First-principles calculations for point defects in solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 253–305 (2014).

Fleming, R. M. et al. Effects of clustering on the properties of defects in neutron irradiated silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 102, 043711 (2007).

Gossick, B. R. Disordered regions in semiconductors bombarded by fast neutrons. J. Appl. Phys. 30, 1214 (1959).

Myers, S. M., Cooper, P. J. & Wampler, W. R. Model of defect reactions and the influence of clustering in pulse-neutron-irradiated Si. J. Appl. Phys. 104, 044507 (2008).

Agostinelli, S. et al. Geant4—a simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 506, 250–303 (2003).

Hall, R. N. Electron-hole recombination in germanium. Phys. Rev. 87, 387 (1952).

Shockley, W. & Read, W. T. Statistics of the recombinations of holes and electrons. Phys. Rev. 87, 835–842 (1952).

Liu, J. et al. Carrier capture dynamics of deep-level defects in neutron-irradiated Si with improved intracascade potential. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 70, 113–122 (2023).

Fleming, R. M., Seager, C. H., Lang, D. V., Bielejec, E. & Campbell, J. M. A bistable divacancylike defect in silicon damage cascades. J. Appl. Phys. 104, 083702 (2008).

Vines, L., Monakhov, E. V., Jensen, J., Kuznetsov, A. Y. & Svensson, B. G. Effect of spatial defect distribution on the electrical behavior of prominent vacancy point defects in swift-ion implanted Si. Phys. Rev. B 79, 075206 (2009).

Monakhov, E. V., Wong-Leung, J., Kuznetsov, A. Y., Jagadish, C. & Svensson, B. G. Ion mass effect on vacancy-related deep levels in Si induced by ion implantation. Phys. Rev. B 65, 245201 (2002).

Markevich, V. P. et al. Trivacancy and trivacancy-oxygen complexes in silicon: Experiments andab initiomodeling. Phys. Rev. B 80, 235207 (2009).

Radu, R. et al. Investigation of point and extended defects in electron irradiated silicon—Dependence on the particle energy. J. Appl. Phys. 117, 164503 (2015).

Hornos, T., Gali, A. & Svensson, B. G. Large-scale electronic structure calculations of vacancies in 4H-SiC Using the Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof screened hybrid density functional. Mater. Sci. Forum 679-680, 261–264 (2011).

Bathen, M. E. et al. Electrical charge state identification and control for the silicon vacancy in 4H-SiC. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 111 (2019).

Alfieri, G. & Mihaila, A. Isothermal annealing study of the EH1 and EH3 levels in n-type 4H-SiC. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 465703 (2020).

Karsthof, R., Bathen, M. E., Galeckas, A. & Vines, L. Conversion pathways of primary defects by annealing in proton-irradiated n-type 4H-SiC. Phys. Rev. B 102, 184111 (2020).

Brodar, T. et al. Depth profile analysis of deep level defects in 4H-SiC introduced by radiation. Crystals 10, 845 (2020).

Li, W. et al. Threshold displacement energies and displacement cascades in 4H-SiC Molecular dynamic simulations. AIP Adv. 9, 055007 (2019).

Hemmingsson, C. et al. Deep level defects in electron-irradiated 4H SiC epitaxial layers. J. Appl. Phys. 81, 6155 (1997).

Alfieri, G. & Kimoto, T. Resolving the EH6/7 level in 4H-SiC by Laplace-transform deep level transient spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 152108 (2013).

Booker, I. D. et al. Donor and double-donor transitions of the carbon vacancy related EH6/7 deep level in 4H-SiC. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 235703 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Characteristic of displacement defects in n-p-n transistors caused by various heavy ion irradiations. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 64, 976–982 (2017).

Deák, P., Aradi, B., Kaviani, M., Frauenheim, T. & Gali, A. Formation of NV centers in diamond: A theoretical study based on calculated transitions and migration of nitrogen and vacancy related defects. Phys. Rev. B 89, 075203 (2014).

Kresse, G. & Furthmu¨ller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207 (2003).

Paier, J. et al. Screened hybrid density functionals applied to solids. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 154709 (2006).

Pässler, R. Description of nonradiative multiphonon transitions in the static coupling scheme. Czech. J. Phys. 24, 322–339 (1974).

Jia, W. et al. The analysis of a plane wave pseudopotential density functional theory code on a GPU machine. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 9–18 (2013).

Jia, W. et al. Fast plane wave density functional theory molecular dynamics calculations on multi-GPU machines. J. Comput. Phys. 251, 102–115 (2013).

Ziegler, J. F., Ziegler, M. D. & Biersack, J. P. SRIM – The stopping and range of ions in matter (2010). Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 268, 1818–1823 (2010).

Miller, L. A., Brice, D. K., Prinja, A. K. & Picraux, S. T. Displacement-threshold energies in Si calculated by molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 49, 16953 (1994).

Zinkle, S. J. & Kinoshita, C. Defect production in ceramics. J. Nucl. Mater. 251, 200–217 (1997).

Pichler, P. Intrinsic Point Defects, Impurities, and Their Diffusion in Silicon. Springer (2004).

Larsen, A. N. et al. E center in silicon has a donor level in the band gap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 106402 (2006).

Aboy, M., Santos, I., Pelaz, L., Marqués, L. A. & López, P. Modeling of defects, dopant diffusion and clustering in silicon. J. Comput. Electron. 13, 40–58 (2013).

Deak, P., Udvarhelyi, P., Thiering, G. & Gali, A. The kinetics of carbon pair formation in silicon prohibits reaching thermal equilibrium. Nat. Commun. 14, 361 (2023).

Martin-Bragado, I., Rivera, A., Valles, G., Gomez-Selles, J. L. & Caturla, M. J. MMonCa: An object Kinetic Monte Carlo simulator for damage irradiation evolution and defect diffusion. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 2703–2710 (2013).

Ferrari, E. F., Koehler, M. & Hümmelgen, I. A. Capacitance-transient-spectroscopy model for defects with two charge states. Phys. Rev. B 55, 9590–9597 (1997).

Petzold, L. Automatic selection of methods for solving stiff and nonstiff systems of ordinary differential equations. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput 4, 136–148 (1983).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12375277, W2511008, 12088101, and 11975018), Science Challenge Project (Grant No. TZ2025013), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2308085J04), Outstanding member of Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (Grant No. Y202087), and Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No.726 XDA0410000). Our calculations were performed at the Center for Computational Science of CASHIPS, Tianhe-JK at CSRC, the ScGrid of Supercomputing Center, and the Computer Network Information Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and B.H. designed this project. Y.L., B.H., and Z.Z. supervised the study. Y.L. and J.L. developed the multiscale modeling framework. J.L. and Y.G. performed simulations including defect generation and evolution as well as theoretical DLTS. X.Y. performed DFT calculations. L.L. conducted neutron irradiation and DLTS experiments. All authors contributed to data analysis, result discussion. J.L., Y.L., and B.H. wrote the manuscript with the help from other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Łukasz Gelczuk and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Gao, Y., Yan, X. et al. Multidimensional defect identification of semiconductors in nonequilibrium. Nat Commun 16, 10684 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65718-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65718-8