Abstract

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5 viruses have recently been documented in mammals including humans, posing a major threat to global public health. To prevent a potential H5 pandemic, it is critical to elucidate the antigenic evolutionary pattern and identify key drivers underlying its evolution. In this work, we construct a comprehensive antigenic map of H5 influenza viruses spanning their evolutionary history and classified three antigenic clusters with no cross-neutralization. The first corresponds to ancestral clades, the second to 2.3.4.4* clades being predominant since 2010, and the third to 2.3.4.4 h clade. Despite the gradually increasing genetic distances from ancestral to 2.3.4.4* to 2.3.4.4 h, their antigenic evolution does not follow the same progressive pattern: the antigenic distance between 2.3.4.4 h and ancestral is smaller than that between 2.3.4.4* and ancestral. This divergence is associated with two distinct mutation patterns at six key amino acid positions: (1) persistent mutations at positions 88 (N > R > S), 199 (D > N > S), and 205 (K > N > D), and (2) reversible mutations at positions 131 (Q > L > Q), 139 (S > P > S), and 289 (N > H > N). These findings not only reveal the antigenic evolution mechanism of H5 influenza, but also provide important guidance for vaccine strain selection and broad-spectrum vaccine development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the emergence of the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus A/Goose/Guangdong/1/1996(GD/96), this subtype has rapidly spread through wild bird populations in Europe, Africa, North America, and Asia, with several lineages evolving1,2,3. Clade 2.3.4.4b, first detected in wild birds in Europe and Asia, caused multiple spillover events among poultry and mink at the end of 20214, followed by subsequent spread to wild mammals such as water rails, sea lions, red foxes and striped skunks5,6,7,8. In late March 2024, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported an outbreak of H5N1 virus in dairy cattle. More concerningly, a case of H5N1 infection in a dairy farm worker was reported in Texas in the same month9. Since then, clade 2.3.4.4b has expanded to 15 states, resulting in dozens of infections and one death in humans10,11. The expanding pattern of zoonotic transmission underscores the risk that continued viral evolution could enable sustained human-to-human transmission and potentially precipitate an influenza pandemic.

In response to the potential threat of pandemic H5 viruses, nearly 30 vaccine stockpiles have been established globally, including A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (clade 1), A/Indonesia/05/2005 (clade 2.1), and more recently A/Astrakhan/3212/2020 (clade 2.3.4.4b)12,13,14,15. However, the protective efficacy of these stockpile vaccines against currently prevalent strains has yet to be evaluated. Given that the protective efficacy of vaccines is largely determined by the degree of antigenic match between vaccine strains and circulating viruses16,17,18, delineating the antigenic relationships of H5 viruses and identifying the key amino acid substitutions driving their antigenic evolution is essential for assessing the effectiveness of existing vaccines and informing future vaccine strain selection.

Previous studies on H5N1 antigenic evolution have primarily focused on variations within individual clades. For example, Koel et al. demonstrated that antigenic variation of clade 2.1 H5N1 virus is determined by 129, 133, 151, 183, 185 and 189, which are immediately adjacent to the receptor binding site19. Zhong et al. showed that three substitutions in antigenic region B, especially D205K, are the major contributors to the antigenic drift of the novel branch of clade 2.3.420. Li et al. revealed an evident impact of mutations at sites 88, 156, 205, 208, 239 and 289 to the HA antigenicity and highlighted that the combined mutations at sites 205 and 208, were the major antigenic determinant of clade 2.3.4.421. Zhang et al. examined eight antigenic sites (115, 120, 124, 126, 140, 151, 156, and 185) that determine the antigenic differences between two H5 vaccine strains, H5-Re8 (clade 2.3.4.4 g) and H5-Re11 (clade 2.3.4.4 h)2. Besides, several studies have characterized the antigenic evolution of H5 influenza viruses. Thi et al. constructed an antigenic map of H5 viruses spanning from 2001 to 201422. Kok et al. systematically characterized the global antigenic evolution landscape of H5 viruses and engineered immunogenic and antigenically central vaccine HA antigens23. However, the antigenic transition pattern during long-term evolution of H5 viruses and the key amino acid substitutions driving their antigenic transitions remain to be elucidated.

In this work, we establish an H5 pseudotyped virus library containing different clades and obtained sera from guinea pigs immunized with vaccine-recommended strains. Through systematic neutralization assays, we construct a comprehensive antigenic map spanning the evolutionary history of H5 influenza viruses, reveal substantial differences between their antigenic and genetic evolution, and identify the amino acid substitutions associated with transitions between adjacent antigenic clusters. Additionally, we assess the neutralizing capacity of stockpile vaccine-induced serum against clade 2.3.4.4b, 2.3.2.1a, 2.3.2.1c and 2.3.4.4 h viruses. These findings not only advance our understanding of H5 influenza virus antigenic evolution, but also provide insights for vaccine strain selection and broad-spectrum vaccine development.

Results

Antigenic evolution of H5 influenza virus

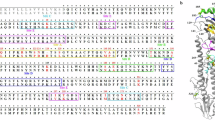

Following evolutionary analysis and intensive sampling of three H5 influenza viruses (H5N1, H5N6, and H5N8), 135 strains were selected to establish the H5 pseudotyped virus library (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Table 2). High-throughput neutralization assays were conducted using sera from guinea pigs immunized with 28 strains (24 vaccine strains and four representative strains) to systematically characterize the antigenic properties of H5 viruses. Based on the neutralization heatmap of H5 vaccine-immunized serum against representative strains, we identified three antigenic clusters of H5 viruses that do not cross-neutralize each other (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 2). The first corresponds to ancestral clades (including 0 ~ 9, 2.1*, 2.2*, 2.3.2*, 2.3.4*), the second to 2.3.4.4* clades (including 2.3.4.4, 2.3.4.4b, 2.3.4.4c, 2.3.4.4e, and 2.3.4.4 g) being predominant since 2010, and the third to 2.3.4.4 h clade. Similar antigenic classification was observed across different NA subtypes, including H5N1, H5N6, and H5N8 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

a Molecular clock evolutionary tree of representative H5 viruses and heatmap of neutralization titers of corresponding pseudoviruses. In the phylogenetic tree, the blue, red, and green areas indicate ancestral clades, 2.3.4.4*, and 2.3.4.4 h, respectively. The vertical coordinates in the heatmap indicate the abbreviation of each vaccine strain and clade. Values in the heatmap indicate the logarithm (log10) of the neutralization titer ratio between the representative strain and the vaccine strain. The results are based on 2-3 technical replicates. Three-dimensional genetic map (b) and antigenic map (c) of H5 viruses, with their two-dimensional projections shown in the x-y, y-z, and x-z planes. d The average genetic and antigenic distances among three antigenic clusters. e Cross-neutralization assays of immunized sera against different antigens. The figure shows cross-neutralization of seventeen ancestral-immunized sera against forty-nine 2.3.4.4* antigens and nine 2.3.4.4 h antigens (0.042 ± 0.048 vs. 0.056 ± 0.058), seven 2.3.4.4*-immunized sera against seventy-seven ancestral antigens and nine 2.3.4.4 h antigens (0.050±0.062 vs. 0.062±0.083), and four 2.3.4.4h-immunized sera against seventy-seven ancestral antigens and forty-nine 2.3.4.4* antigens (0.047 ± 0.103 vs. 0.050 ± 0.040), with all statistical comparisons performed using two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests without adjustment for multiple comparisons. The definitions of the minimum, maximum, center, box and whisker bounds, and percentiles for the box plot are provided in Supplementary Table 3. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The genetic map (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 4.) showed that the three antigenic clusters presented a sequential distribution in genetic space, with the genetic distance gradually increasing from ancestral to 2.3.4.4* to 2.3.4.4 h (Fig. 1d), consistent with the topology of the phylogenetic tree. However, the antigenic map (Fig. 1c) revealed that the antigenic evolution does not follow the same progressive pattern: the antigenic distance between 2.3.4.4 h and ancestral is smaller than that between 2.3.4.4* and ancestral (Fig. 1d). Based on the average titer calculations against different antigens, ancestral-immunized sera exhibited significantly higher neutralization against 2.3.4.4 h versus 2.3.4.4* (P = 0.0004), 2.3.4.4*-immunized sera showed stronger neutralization against 2.3.4.4 h than ancestral (P = 0.0727) and 2.3.4.4h-immunized sera exhibited significantly higher neutralization against 2.3.4.4* versus ancestral (P = 0.0022) (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 5). Therefore, between ancestral and 2.3.4.4 h, there is a larger genetic distance but a smaller antigenic distance, suggesting a non-linear relationship between antigenic and genetic evolution of H5 influenza viruses.

Epidemiology of the main human-infected clades and the protective effect of existing vaccines

Epidemiological data showed that ancestral clades were predominant before 2010, with clades 0 ~ 9, 2.1*, 2.2*, 2.3.2*, and 2.3.4* emerging successively. Around 2010, 2.3.4.4* clades emerged and gradually replaced ancestral clades, with clade 2.3.4.4b becoming predominant. 2.3.4.4 h was a small clade detected in limited regions and outcompeted by clade 2.3.4.4b after 2020 (Fig. 2a). The clades with documented human infections since 2021 included 2.3.2.1a, 2.3.2.1c, 2.3.4.4b, and 2.3.4.4 h. Based on available sampling data, although 2.3.2.1a, 2.3.2.1c, and 2.3.4.4 h had fewer sampled strains, they exhibited higher proportions of documented human infections (0.68%, 7.09%, and 8.89%, respectively) compared to the most frequently sampled strain 2.3.4.4b (0.19%) (Fig. 2a, b). This observation indicates that low-prevalence strains may have a high zoonotic potential and epidemiological surveillance needs to focus on the clades 2.3.2.1a, 2.3.2.1c, and 2.3.4.4 h. Clades 2.3.2.1a, 2.3.2.1c, and 2.3.4.4 h exhibit geographically restricted distributions, primarily concentrated in Asian countries. Among them, 2.3.2.1a and 2.3.2.1c are H5N1-specific, and 2.3.4.4 h is H5N6-specific. Unlike the three clades above, the most widespread clade, 2.3.4.4b, is distributed across multiple continents and includes H5N1, H5N6, and H5N8 (Fig. 2b).

a Epidemiology of different clades of the H5 influenza virus antigenic cluster. The figure depicts the epidemiology of each clade over time, the distribution of human infections across the various clades, and the proportion of documented human infections in each clade since 2021. b Geographical distribution of clades 2.3.2.1a, 2.3.2.1c, 2.3.4.4b, and 2.3.4.4 h and the composition of different NA subtypes and hosts. c Analysis of the neutralization of clade 2.3.2.1a, 2.3.2.1c, 2.3.4.4b, and 2.3.4.4 h strains by of 28 immunized serum. The dotted line represents a neutralizing antibody titer of 1000. Strains from different clades are shown in different colors. Circles in the columns indicate the different strains in the clade (n = 3 (clade 2.3.2.1a), 10 (clade 2.3.2.1c), 29 (clade 2.3.4.4b) and 9 (clade 2.3.4.4 h)). Values were shown as geometric means with geometric standard deviations (SD). The results are based on 2-3 technical replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further analyzed the neutralizing ability of vaccine strains from clades 2.3.4.4b, 2.3.4.4 h, 2.3.2.1a, and 2.3.2.1c (Fig. 2c). The vaccine strains recommended by WHO for 2.3.4.4b in the past two years are CR21 and AS20, both of which showed high neutralization activity against clade 2.3.4.4b viruses, with titers range 1000–10,000. Additionally, we observed that TE24 (bovine-origin human isolate)-immunized serum exhibited slightly higher neutralization titers against clade 2.3.4.4b viruses compared to AS20 and CR21. The vaccine strain for clade 2.3.2* neutralized 2.3.2.1c better than it did 2.3.2.1a. We also note that the remaining vaccine strains within ancestral clades, such as VI04 and CA07, can achieve a neutralization level of approximately 1000 for these two clades. The vaccine strain GD18 and the representative strain GX17 for clade 2.3.4.4 h neutralized most of the 2.3.4.4 h viruses with antibody levels of approximately 10,000. The remaining two representative strains were relatively poorly immunogenic. The vaccine strains of ancestral and 2.3.4.4* clades both had neutralization titers below 1000 against the 2.3.4.4 h strains. In summary, the immunized serum elicited by WHO-recommended candidate vaccine strains demonstrate substantial protection against viruses of corresponding clades.

Transition mechanisms between adjacent antigenic clusters

Between ancestral and 2.3.4.4* clades, six substitutions N88R, Q131L, S139P, D199N, K205N, and N289H were identified (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 6). We then evaluated the antigenic escape of these mutations, both individually and in various combinations, using site-directed mutagenesis (Supplementary Fig. 7a). In the forward validation, ancestral+6 M (six mutations based on ancestral) and ancestral+K205N showed an approximately 10-fold escape from ancestral-immunized serum, comparable to 2.3.4.4* (Fig. 3b). The reverse validation results showed 2.3.4.4*-6M (six mutations based on 2.3.4.4*) had an approximately 50-fold escape from 2.3.4.4*-immunized serum, comparable to ancestral (Fig. 3b), but 2.3.4.4*-K205N did not lead to escape. Based on the bidirectional validation results, we concluded that the antigenic difference between ancestral and 2.3.4.4* clades is associated with the six substitutions (N88R, Q131L, S139P, D199N, K205N and N289H).

a Detailed mutation information of 6 M and 6′M. b Identification of key mutations determining antigenic difference between ancestral and 2.3.4.4* clades. Ancestral (forward) and 2.3.4.4* (reverse) was used as template for mutational modifications to assess the escape from ancestral (n = 2 biological samples) and 2.3.4.4*-immunized serum (n = 3 biological samples). Values were shown as geometric means with geometric standard deviations (SD). c Identification of key mutations determining antigenic difference between 2.3.4.4* clades and 2.3.4.4 h clade. 2.3.4.4* (forward) and 2.3.4.4 h (reverse) was used as template for mutational modifications to assess the escape from 2.3.4.4* and 2.3.4.4h-immunized serum (n = 3 biological samples). d Distribution of positions 88, 131, 139, 199, 205, and 289 across epitopes on the H5 HA protein, using the H3 epitope classification as a reference. e Evolutionary trajectories of positions 88, 131, 139, 199, 205, and 289. Dashed lines separate ancestral, 2.3.4.4*, and 2.3.4.4 h, and the different colors represent various amino acids. The results are based on 3 technical replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Between 2.3.4.4* and 2.3.4.4 h, we identified amino acid substitutions at the same six positions: 88, 131, 139, 199, 205, and 289. Specifically, 88 R, 199 N, and 205 N were mutated to 88S, 199S, and 205D, while 131 L, 139 P, and 289H reverted to 131Q, 139S, and 289 N (Fig. 3a). Further, we evaluated the antigenic escape of these mutations, both individually and in various combinations, using site-directed mutagenesis (Supplementary Fig. 7b). 2.3.4.4* + 6′M (six mutations based on 2.3.4.4*) and 2.3.4.4* + L131Q + P139S caused approximately 10-fold escape from 2.3.4.4*-immunized serum (Fig. 3c). The reverse validation results showed 2.3.4.4h-6′M (six mutations based on 2.3.4.4 h) had an approximately 20-fold escape from 2.3.4.4h-immunized serum, comparable to 2.3.4.4*(Fig. 3c), but 2.3.4.4h-L131Q-P139S did not lead to significant escape. Based on the bidirectional validation results, the antigenic difference between 2.3.4.4* and 2.3.4.4 h is associated with six substitutions (R88S, L131Q, P139S, N199S, N205D and H289N).

As a result, we identified that six amino acid positions 88, 131, 139, 199, 205 and 289 play important roles in antigenic difference between three antigenic clusters. These six positions are distributed across multiple antigenic epitopes (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 8). Positions 139, 199, and 205 are located within antigenic region B, 289 maps to region C, and positions 88 and 131 are situated near regions E and A, respectively. Importantly, these six sites exhibit two mutation patterns, persistent mutations at positions 88 (N > R > S), 199 (D > N > S), and 205 (K > N > D), and revertant mutations at positions 131 (Q > L > Q), 139 (S > P > S), and 289 (N > H > N) (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 9a). The revertant mutations may explain the antigenic reversion observed in 2.3.4.4 h despite its continued genetic evolution.

Mechanisms underlying antigenic differences among ancestral clades

Ancestral clades included clades 0 ~ 9, 2.1*, 2.2*, 2.3.2*, and 2.3.4*. Among them, the vaccine strains in clade 0 ~ 9 and 2.3.4* are usually able to neutralize most of strains contained in ancestral clades (Fig. 4a, b). In contrast, vaccine strains in clades 2.1*, 2.2*, and 2.3.2* only neutralize their corresponding clade strains (Fig. c-d), indicating some degree of antigenic drift in 2.1*, 2.2*, and 2.3.2*. Further, we sought to identify amino acid substitutions responsible for these antigenic drifts.

a–b Neutralizing capacity of vaccine strains from clades 0 ~ 9 and 2.3.4* against all clades within ancestral (n = 17 (clade 0 ~ 9), 13 (clade 2.1*), 8 (clade 2.2*), 11 (clade 2.3.2*), and 13 (clade 2.3.4*)). Values were shown as geometric means with geometric standard deviations (SD). c–d Neutralizing capacity of vaccine strains from clades 2.1*, 2.2*, and 2.3.2* against all clades within ancestral. e Phylogenetic topology among clades within ancestral and amino acid substitutions in clades 2.1*, 2.2*, and 2.3.2* compared to GD96. f Identification of mutations contributing to antigenic difference between GD96 and 2.1*. GD96 (forward) and 2.1* (reverse) was used as template for mutational modifications to assess the escape from GD96 and 2.1*-immunized serum. Modifications included 7 M, various mutation combinations (n = 3 biological samples). g Identification of mutations contributing to antigenic difference between GD96 and 2.2*. GD96 (forward) and 2.2* (reverse) was used as template for mutational modifications to assess the escape from GD96 and 2.2*-immunized serum. Modifications included 8 M, various mutation combinations (n = 3 biological samples). h Identification of mutations contributing to antigenic differences between GD96 and 2.3.2*. The clade 2.3.2* (reverse) and GD96 (forward) was used as a template for revertant mutation to assess the escape from clade 2.3.2* and GD96-immunized serum. Modifications included 10 M, various mutation combinations (n = 3 biological samples). i Distribution of positions 61, 69, 110, 140, 142, 145, 149, 154, 157, 171, 172, 205, 228, 243, and 285 across epitopes on the H5 HA protein surface, using the H3 epitope classification as a reference. The results are based on 3 technical replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Between GD96 and clade 2.1*, seven mutations (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 6), N61D, N140D, D142E, S157P, A172T, K205R, and E228K were identified. In the forward validation, GD96 + 7 M (seven mutations based on GD96) and GD96 + N61D + D142E + S157P + E228K showed more than 30-fold escape from GD96-immunized serum, comparable to clade 2.1* (Fig. 4f). The reverse validation also demonstrated that the 2.1*-7M and 2.1*-N61D-D142E-S157P-E228K exhibited escape from 2.1*-immunized serum at levels comparable to GD96 (Fig. 4f). Other combinations and single mutation exhibited only partial or minimal immune escape (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). Thus, we conclude that four substitutions (N61D, D142E, S157P, and E228K) drove the antigenic difference between GD96 and clade 2.1*.

Between GD96 and clade 2.2*, eight mutations (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 6), N61D, D110N, N140D, D142E, H154Q, S171N, K205R, and E228K were identified. In the forward validation, GD96 + 8 M (eight mutations based on GD96) and GD96 + N61D + D142E + E228K showed approximately 60-fold escape from GD96-immunized serum, comparable to clade 2.2* (Fig. 4g). However, the reverse validation showed that 2.2*-8M (eight mutations based on 2.2*) and 2.2*-N61D-D142E-E228K exhibited approximately 5-fold escape from 2.2*-immunized serum, which is slightly less than that of GD96 (Fig. 4g). Other combinations and single mutation exhibited only partial or minimal immune escape (Supplementary Fig. 10c–d). Thus, we conclude that three substitutions (N61D, D142E, and E228K) were related to the antigenic difference between GD96 and clade 2.2*, but some unvalidated sites may also play certain roles.

Between GD96 and clade 2.3.2*, ten mutations (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 6), R69K, D110N, N140D, S145L, S149A, H154Q, S171N, K205R, E243D, and L285V were identified. In the reverse validation, 2.3.2*-10M (ten mutations based on 2.3.2*), 2.3.2*-N140D-K205R, 2.3.2*-D110N-H154Q-S171N, and 2.3.2*-R69K-S145L- S149A-E243D-L285V showed more than 10-fold escape from 2.3.2*-immunized serum, comparable to GD96 (Fig. 4h). However, the forward validation showed that these combinations did not lead to escape. The asymmetric results between forward and reverse validation suggest a complex antigenic relationship between GD96 and clade 2.3.2*. The antigenic difference may be associated with all ten mutations, while other unvalidated sites might also contribute to some extent.

These results suggest that the antigenic differences within ancestral clades were determined by concerted mutations at multiple positions (Supplementary Fig. 9b). The evolutionary trajectories of these positions showed that most positions underwent only two amino acid substitutions, whereas positions 140 and 205 experienced more than three amino acid changes (Supplementary Fig. 11). Structural analysis (Fig. 4i, Supplementary Fig. 8) revealed that these mutations were mainly concentrated in five epitopes, especially in epitopes A (140, 142, 154, 157) and B (171, 172, 205), suggesting that these regions were hotspots for antigenic variation in H5 viruses.

Discussion

The hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay is a classical and reliable method in the antigenicity studies of influenza viruses. However, the use of chicken erythrocytes has been shown to measure the relative insensitivity of the human response to the avian influenza virus H5N124,25,26. The pseudovirus-based neutralizing antibody assay is more sensitive, convenient, and safer to operate, and has been validated to correlate well with classical HI assay27. Based on the pseudovirus system, we constructed the comprehensive antigenic map of H5 influenza viruses spanning their evolutionary history.

Although H5 viruses evolved into multiple genetic clades, they can be clearly divided into three major antigenic clusters based on their antigenic properties. The three antigenic clusters exhibit characteristic patterns in their NA subtypes, host ranges, and geographic distributions. The first corresponded to ancestral clades, which focused on H5N1 subtypes, and were concentrated in several Asian countries. The five clades within ancestral were endemic in different regions during the same period (2005 ~ 2012). The second corresponded to 2.3.4.4* clades, which encompasses H5N6 and H5N8 subtypes in addition to H5N1. Notably, clade 2.3.4.4b emerged in the Middle East and became the predominant clade across Asia, Europe, and Africa28,29,30. Its host range and cross-species transmission potential have further expanded following persistent outbreaks in U.S. dairy populations31. 2.4.4.4 h clade, introduced by migratory birds in 2018, was classified as the third antigenic cluster in our study. This clade showed considerable antigenic difference from the vaccine strain H5-Re8 (clade 2.3.4.4 g), leading to the development of a new, antigenically matched vaccine designated H5-Re112,32.

The currently globally concerning clade 2.3.4.4b belonged to the second antigenic cluster. In response to its threat, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed two candidate vaccine strains (CVVs): A/Astrakhan/3212/2020 (AS20) and A/American Wigeon/South Carolina/USDA-000345-001/2021 (CR21). Recent studies demonstrated that A/Texas/37/2024 (TE24), isolated from a farm worker in Texas, showed cross-reactivity with the CVVs and was effectively neutralized by ferret antisera induced by CVVs33. Our study also confirms that TE24-immunized guinea pig sera exhibit comparable or even higher neutralization levels against the 2.3.4.4b strain compared to AS20 and CR21. In addition, other vaccine strains within the 2.3.4.4* clades also showed effective neutralization.

In this study, we identified a unique non-linear transition pattern among the three antigenic clusters, where antigenic distance is decoupled from genetic distance of H5 influenza virus. Phylogenetically, ancestral to 2.3.4.4* to 2.3.4.4 h represents a linear progression with sequentially increasing genetic distances. However, antigenically, the distance between ancestral and 2.3.4.4 h was smaller than that between ancestral and 2.3.4.4*, indicating nonlinear divergence. This unique non-linear antigenic evolution pattern differs from that observed in H3N2 and H1N1 subtypes. Smith et al.34 identified 11 antigenic clusters that characterized the antigenic profile of H3N2 viruses from 1968 to 2003, demonstrating a remarkable correspondence between antigenic and genetic evolution. Liu et al.35 developed PREDAC-H1, a computational method for predicting antigenicity of human influenza A (H1N1) viruses, which systematically mapped the antigenic patterns and evolution of human H1N1 viruses, revealing a stepwise linear evolutionary relationship in the H1N1 subtype. These results indicated the diverse patterns of antigenic evolution among different influenza virus subtypes.

Further, we found the nonlinear antigenic evolution is associated with two distinct mutation patterns at six key amino acid positions: (1) persistent mutations at positions 88 (N > R > S), 199 (D > N > S), and 205 (K > N > D), and (2) reversible mutations at positions 131 (Q > L > Q), 139 (S > P > S), and 289 (N > H > N). Structurally, the six key sites exhibit diverse distribution characteristics on the HA protein. Positions 205 and 199 are located in the top of antigenic region B, directly exposed to immune recognition; position 139 lies within region A; positions 131 and 88 are situated on the lateral surface; and position 289 is positioned near the stem region within region C.

The progressive mutation at position 88 (N > R > S) progressively altered the surface charge distribution, potentially affecting antibody binding, such as with H5M9 and 100F436. For position 199, the D > N > S substitution may facilitate immune escape to some antibodies (20A11, 16F13, 13D4) by altering glycosylation patterns37. The mutation K > N > D at 205 position may alter surface charge distribution, which has been validated to affect the binding with many antibodies, such as AVFLuIgG03, VN04-(2, 8, 9), 20A11, 16F13, 13D4, 3B1, 3H11, 4C2, 2D9, and so on36,37. These results indicated the import role of position 205 in the H5 virus antigenic evolution.

Reversions suggest a trade-off between immune escape and structural-functional constraints. The reversion at site 139 (S > P > S), may help restore the conformational flexibility essential for this region, as the rigidity introduced by proline could impair protein function38,39. The reversion at site 131 (L > Q > L), may help preserve the appropriate hydrophobicity and spatial structure in this area. Meanwhile, the reversion at site 289 (N > H > N) is likely important for maintaining the original glycosylation pattern, which plays a critical role in viral stability and immune evasion40,41. These reversion mutations suggest that while the virus acquires immune escape capabilities, it is necessary to preserve fundamental structural stability and biological function.

Due to substitutions N88R, Q131L, S139P, D199N, K205N and N289H, 2.3.4.4* achieved substantial immune escape from ancestral clades and became the dominant strain after 2010. In contrast, although 2.3.4.4 h continued to evolve at the same six positions, revertant mutations at positions 131, 139, and 289 have increased its antigenic similarity to ancestral. This unexpected structural reversion likely reduced its competitive advantage in hosts with pre-existing immunity, leading to its replacement by 2.3.4.4* after limited regional circulation. It is worth noting that structural and immunological analyses cannot fully explain the antigenic convergence and reversion. Further biochemical and phenotypic studies will be essential to clarify the precise role of these sites in viral fitness and transmission.

In the ancestral clades, vaccine strains from clades 0 ~ 9 and 2.3.4* showed broad neutralization ability against all clades within ancestral, whereas vaccine strains from clades 2.1*, 2.2*, and 2.3.2* provided protection only against their respective clades. The antigenic specificity of three clades was related with the synergistic effects of “N61D, D142E, S157P, E228K”, “N61D, D142E, E228K”, and “R69K, D110N, N140D, S145L, S149A, H154Q, S171N, K205R, E243D, L285V”, respectively. Several of these positions have been previously reported in other studies, such as key positions126, 141, 156, and 189 (corresponding to 142, 157, 172, and 205 in our numbering system) identified by Zhang et al.2; positions 129, 133, 183, and 189 (corresponding to positions 145, 149, 199, and 205 in our numbering system) determined by Koel et al.19. Additionally, Li et al.21 identified positions and 205 as crucial antigenic determinant positions.

During the validation of key positions, we observed some inconsistencies in bidirectional verification results. For instance, when bidirectionally testing the 6 M and 6’M mutants, the results deviated from initial expectations (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Fig. 7). We propose that other positions likely contribute as well, potentially through strain-specific functional adaptations, although these six key residues can cause the antigenic change. Similar inconsistencies emerged during validation between GD96 and 2.1*, GD96 and 2.2*, as well as GD96 and 2.3.2* (Fig. 4f–h, Supplementary Fig. 10), indicating other unvalidated sites might also contribute to some extent. We acknowledge that our screening process could not comprehensively cover all variant sites due to the substantial workload involved, representing a limitation of our validation approach. Therefore, the key positions identified in this study should be interpreted with the understanding that uncharacterized sites may also contribute to the observed phenotypes.

In this study, we established a comprehensive antigenic map of H5 influenza virus, systematically elucidated its non-linear antigenic evolutionary pattern, and identified the amino acid substitutions being related with antigenic evolution. Most identified antigenic sites are located in the HA head domain, resembling immune escape mutation distribution observed in human influenza viruses H3N2 and H1N142,43,44,45. For H3 and H1 subtypes, studies have shown they experience relatively weaker immune pressure from avian hosts compared with human46. Since H5 viruses currently circulate primarily in avian species and only sporadically infect humans without sustained human-to-human transmission capability, we hypothesize that their exposure to human immune selection pressure remains relatively low. However, should H5 viruses acquire efficient human-to-human transmissibility, their antigenic evolution patterns may change. For example, certain mutations could alter receptor-binding specificity10,47 (shifting from α2,3- to α2,6-sialic acid preference). Under human population immune pressure, immune escape may accelerate, potentially increasing HA mutation rates. Additionally, reassortment with seasonal influenza strains could introduce novel antigenic combinations. Therefore, continuous monitoring of H5 antigenic variation is imperative. Although clade 2.3.4.4b currently predominates, clades 2.3.2.1a and 2.3.2.1c are also actively circulating. Given that no current vaccine offers broad protection against these epidemic clades, we recommend establishing comprehensive surveillance systems while developing broadly protective vaccines.

Methods

Cells

MDCK (Canis familiaris, kidney, RRID: CVCL-0422) and 293 T (Homo sapiens, embryonic kidney, RRID: CVCL-0063) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, high glucose; HyClone, Cat#SH30243.01) with 100 U/ml of penicillin-streptomycin solution (GIBCO, Cat#15140163), and 10% fetal bovine serum (TransGen Biotech, Cat#FS201) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Vaccine and representative strain selection

A total of 135 experimental strains were used in this study, including 24 vaccine strains, and 111 representative strains (Supplementary Tables 1–2). The vaccine strains were recommended by the WHO for 2024–2025 (https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/ vaccines/who-recommendations/zoonotic-influenza-viruses-and-candidate-vaccine-viruses). The 111 sequences were selected as follows. As of 29 May 2024, 17,591, 2623 and 3571 HA protein sequences were downloaded from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) database for H5N1, H5N6 and H5N8, respectively. Taking H5N1 as an example, sequences from the human host were deduplicated using a similarity threshold of 0.98, resulting in 40 sequences; sequences from other mammalian hosts (excluding humans) were deduplicated using a similarity threshold of 0.99, resulting in 24 sequences; and sequences from avian hosts were deduplicated using a similarity threshold of 0.96, resulting in 12 sequences. Therefore, a total of 76 sequences were selected as representative H5N1 strains. Using the same strategy, 27 and 8 sequences were selected as representative strains for H5N6 and H5N8, respectively. In total, 111 H5 influenza virus strains, 24 vaccine strains were selected for subsequent pseudotyped virus construction. These representative strains covered all clades of H5 viruses and showed even distribution across the phylogenetic tree of H5, demonstrating their representativeness (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Phylogenetic tree construction

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT v7.505 with the A/Goose/Guangdong/1/96 (H5N1) (GD/96) strain as the reference sequence. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed with FastTree v2.1.11 using the optimal amino acid substitution model. For evolutionary parameter estimation, divergence time and evolutionary rate were estimated within a Bayesian framework using BEAST v2.7.7 with an uncorrelated relaxed molecular clock model assuming a lognormal distribution. The Blosum62 substitution model was employed with gamma-distributed rate heterogeneity and a proportion of invariant sites. The MCMC chain was run for 50 million generations with sampling every 1,000 generations. The MCMC results were analyzed using Tracer v1.7.2 to ensure effective sample sizes greater than 200. Finally, a maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree was generated using TreeAnnotator with 20% burn-in and node heights set to posterior mean values.

Site-directed mutagenesis

The HA and NA protein sequences listed in Supplementary Tables 1–2 were downloaded from GISAID. PcDNA3.1-HA and pcDNA3.1-NA recombinant plasmids were constructed by inserting the codon-optimized HA and NA sequences of H5 viruses into pcDNA3.1. The entire sequence was synthesized on the backbone plasmid pcDNA3.1(+) using General Biological System (Anhui, China). The pcDNA3.1-HA plasmid was used as the template to generate the plasmid harboring specific mutations of HA. Following site-directed mutagenesis PCR, the template chain was digested using DpnI restriction endonuclease (NEB, USA). Afterwards, the PCR product was directly used to transform E. coli DH5a competent cells, after which single colonies were selected and the construct sequenced.

Pseudotyped virus production

On day 1, 293 T cells were resuspended to a concentration of 5 ~ 7 × 105 cell/ml and seeded into a T75 culture flask (15 mL cell suspension per flask). Cells were incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂. On day 2, 293 T cells were co-transfected with the HA plasmid, NA plasmid and HIV backbone plasmid (pSG3Δenv-FlucΔnef) at a mass ratio of 1:1:2 using transfection reagent LipofectamineTM 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). These cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 6 hours, after which the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS). At 48 hours post-transfection, the virus-containing supernatant was collected, filtered through a 0.45-μm pore-size polyethersulfone membrane (Millipore, Cat# SLHP033RB), aliquoted into 2 mL cryovials, and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Production of immunized sera

Animal experiments were conducted in strict accordance with the institutional animal care and use guidelines of the Institute of Medical Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College (IMBCAMS, Yunnan, China). The experimental protocol received formal approval from the IMBCAMS Animal Ethics Committee (Approval No. DWSP20240616). 24 vaccine strains and four representative strains, including TE24 (A/Texas/37/2024), GX17 (A/Guangxi/13486/2017), FJ19 (A/duck/China/FJ1914/2019), and GX21 (A/GX-hechi/01/2021), were used to immunize guinea pigs. Twenty-eight experimental groups (n = 3 female guinea pigs per group; body weight 200–220 g) received intramuscular electroporation-mediated delivery of 200 µg pcDNA3.1-HA plasmid constructs (28 distinct variants, one plasmid per group) on days 0, 14, and 28. Immunization was repeated three times at two-week intervals, and serum samples were obtained two weeks after the third immunization. Serum samples were stored at −20 °C, then thawed and heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min before use.

Neutralization assay

Immunized sera were diluted to an appropriate initial concentration and then subjected to a three-fold serial dilution. Subsequently, 100 μL of each serum dilution was added into a 96-well plate. The resulting dilutions were mixed with 50 μL of pseudotyped viruses at a concentration of 1300 TCID50/ml and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Afterwards, MDCK cells were added into the plates (2 × 104 cells/100 μL per well). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 48 h, after which the chemiluminescence signals were detected using the Britelite plus reporter gene assay system (PerkinElmer, Ensight). The pseudovirus neutralization titer was calculated using the Reed-Muench method in PerkinElmer Ensight software. The results are based on 2-3 replicates unless specified otherwise.

Construction of antigenic and genetic maps

The antigenic map was constructed based on pseudotyped virus neutralization titer data. Firstly, the raw data were log-transformed and normalized to convert the exponential differences between titers into a linear relationship. The T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding algorithm was chosen for dimensionality reduction to maintain the local structural relationships of the data to more accurately show the complex antigenic differences among viral strains. In cluster analysis, hierarchical clustering was performed using Ward’s method to form compact clusters by minimizing the within-cluster variance, which allowed us to discover virus groups with similar antigenicity. The genetic map was constructed based on the HA amino acid sequences of H5 viruses. After performing multiple sequence alignment, genetic diversity was quantified by calculating the proportion of variant sites between sequences. The same downscaling and clustering strategy was subsequently used to ensure methodological consistency between antigenic and genetic analyses. All data analyses were performed using Python, relying on the Biopython, scipy, and sklearn scientific computing libraries.

Data analysis and processing

GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Values were shown as geometric means with geometric standard deviations (SD).

Data availability

The dataset that supports the findings of this study are available in Figshare with the identifier [data (s) “https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29517866”]. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Gao, F. et al. Pandemic preparedness of effective vaccines for the outbreak of newly H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Virol. Sin. 39, 981–985 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. A broad-spectrum vaccine candidate against H5 viruses bearing different sub-clade 2.3.4.4 HA genes. NPJ Vaccines 9, 152 (2024).

Tian, J. et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus (H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Introduced by Wild Birds, China, 2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29, 1367–1375 (2023).

Koopmans, M. P. G. et al. The panzootic spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 sublineage 2.3.4.4b: a critical appraisal of One Health preparedness and prevention. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, e774–e781 (2024).

Xie, R. et al. The episodic resurgence of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5 virus. Nature 622, 810–817 (2023).

Peacock, T. P. et al. The global H5N1 influenza panzootic in mammals. Nature 637, 304–313 (2025).

Plaza, P. I. et al. Pacific and Atlantic sea lion mortality caused by highly pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) in South America. Travel Med Infect. Dis. 59, 102712 (2024).

Alkie, T. N. et al. Characterization of neurotropic HPAI H5N1 viruses with novel genome constellations and mammalian adaptive mutations in free-living mesocarnivores in Canada. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 12, 2186608 (2023).

Uyeki, T. M. et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Infection in a Dairy Farm Worker. N. Engl. J. Med 390, 2028–2029 (2024).

Good, M. R. et al. A single mutation in dairy cow-associated H5N1 viruses increases receptor binding breadth. Nat. Commun. 15, 10768 (2024).

CDC. First H5 Bird Flu Death Reported in United States https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2025/m0106-h5-birdflu-death.html (2025).

WHO. Zoonotic Influenza: Candidate Vaccine Viruses and Potency Testing Reagentshttps://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/vaccines/who-recommendations/zoonotic-influenza-viruses-and-candidate-vaccine-viruses (2024).

Khurana, S. et al. Licensed H5N1 vaccines generate cross-neutralizing antibodies against highly pathogenic H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b influenza virus. Nat. Med. 30, 2771–2776 (2024).

Khurana, S. et al. Vaccines with MF59 adjuvant expand the antibody repertoire to target protective sites of pandemic avian H5N1 influenza virus. Sci. Transl. Med 2, ra15–15ra15 (2010).

Beigel, J. H. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of multiple and higher doses of an inactivated influenza A/H5N1 vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 200, 501–508 (2009).

Chen, L. M. et al. Biosafety risk assessment for production of candidate vaccine viruses to protect humans from zoonotic highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 14, 215–225 (2020).

Okoli, G. N. et al. Variable seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness across geographical regions, age groups and levels of vaccine antigenic similarity with circulating virus strains: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence from test-negative design studies after the 2009/10 influenza pandemic. Vaccine 39, 1225–1240 (2021).

Uyeki, T. M. et al. Influenza. Lancet 400, 693–706 (2022).

Koel, B. F. et al. Antigenic variation of clade 2.1 H5N1 virus is determined by a few amino acid substitutions immediately adjacent to the receptor binding site. mBio 5, e01070–01014 (2014).

Zhong, L. et al. The antigenic drift molecular basis of the H5N1 influenza viruses in a novel branch of clade 2.3.4. Vet. Microbiol. 171, 23–30 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Amino acid substitutions in antigenic region B of hemagglutinin play a critical role in the antigenic drift of subclade 2.3.4.4 highly pathogenic H5NX influenza viruses. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 67, 263–275 (2020).

Thi et al. Antigenic characterization of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses with chicken and ferret antisera reveals clade-dependent variation in hemagglutination inhibition profiles. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 7, 1–15 (2018).

Kok, A. et al. A vaccine antigen central in influenza A(H5) virus antigenic space confers subtype-wide immunity. bioRxiv (2024).

Temperton, N. J. et al. A sensitive retroviral pseudotype assay for influenza H5N1-neutralizing antibodies. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 1, 105–112 (2007).

Prabakaran, M. et al. Development of epitope-blocking ELISA for universal detection of antibodies to human H5N1 influenza viruses. PLoS One 4, e4566 (2009).

Tsai, C. et al. Measurement of neutralizing antibody responses against H5N1 clades in immunized mice and ferrets using pseudotypes expressing influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. Vaccine 27, 6777–6790 (2009).

Alberini, I. et al. Pseudoparticle neutralization is a reliable assay to measure immunity and cross-reactivity to H5N1 influenza viruses. Vaccine 27, 5998–6003 (2009).

Lee, D. H. et al. Evolution, global spread, and pathogenicity of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5Nx clade 2.3.4.4. J. Vet. Sci. 18, 269–280 (2017).

Lee, D. H. et al. Novel reassortant Clade 2.3.4.4 avian influenza A(H5N8) virus in wild aquatic birds, Russia, 2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 359–360 (2017).

Li, M. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N8) virus in wild migratory birds, Qinghai Lake, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 637–641 (2017).

Mostafa, A. et al. Avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in dairy cattle: origin, evolution, and cross-species transmission. mBio 15, e0254224 (2024).

Zeng, X.-Y. et al. Protective efficacy of an H5/H7 trivalent inactivated vaccine produced from Re-11, Re-12, and H7-Re2 strains against challenge with different H5 and H7 viruses in chickens. J. Integr. Agricult. 19, 2294–2300 (2020).

Garg, S. et al. Outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses in U.S. dairy cattle and detection of two human cases - United States, 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 73, 501–505 (2024).

Smith, D. J. et al. Mapping the antigenic and genetic evolution of influenza virus. Science 305, 371–376 (2004).

Liu, M. et al. Antigenic patterns and evolution of the human influenza A (H1N1) Virus. Sci. Rep. 5, 14171 (2015).

Zuo, T. et al. Comprehensive analysis of antibody recognition in convalescent humans from highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 infection. Nat. Commun. 6, 8855 (2015).

Wu, W. L. et al. Antigenic profile of avian H5N1 viruses in Asia from 2002 to 2007. J. Virol. 82, 1798–1807 (2008).

Qiao, H. et al. Specific single or double proline substitutions in the “spring-loaded” coiled-coil region of the influenza hemagglutinin impair or abolish membrane fusion activity. J. Cell Biol. 141, 1335–1347 (1998).

Sanders, R. W. & Moore, J. P. Virus vaccines: proteins prefer prolines. Cell Host Microbe 29, 327–333 (2021).

Shi, K. et al. N-glycosylation on hemagglutinin head reveals inter-branch antigenic variability of avian influenza virus H5-subtypes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 273, 132901 (2024).

Gu, C. et al. Glycosylation and an amino acid insertion in the head of hemagglutinin independently affect the antigenic properties of H5N1 avian influenza viruses. Sci. China Life Sci. 62, 76–83 (2019).

Wiley, D. C., Wilson, I. A. & Skehel, J. J. Structural identification of the antibody-binding sites of Hong Kong influenza haemagglutinin and their involvement in antigenic variation. Nature 289, 373–378 (1981).

Broecker, F. et al. Immunodominance of antigenic site B in the hemagglutinin of the current H3N2 influenza virus in humans and mice. J. Virol. 92, e01100-18 (2018).

Popova, L. et al. Immunodominance of antigenic site B over site A of hemagglutinin of recent H3N2 influenza viruses. PLoS One 7, e41895 (2012).

Wu, N. C. et al. Major antigenic site B of human influenza H3N2 viruses has an evolving local fitness landscape. Nat. Commun. 11, 1233 (2020).

Trovão, N. S. et al. Comparative evolution of influenza A virus H1 and H3 head and stalk domains across host species. mBio 15, e0264923 (2024).

Lin, T. H. et al. A single mutation in bovine influenza H5N1 hemagglutinin switches specificity to human receptors. Science 386, 1128–1134 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the authors from the originating and submitting laboratories where genetic sequence data were generated and shared via GISAID, enabling this research. This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2023-I2M-2-001 and 2022-I2M-3-001, to Y.W.), Yunnan Provincial Major Science and Technology Projects (202402AA310024, to Y.W.), Major Project of Guangzhou National Laboratory (GZNL2024A01015, to A.W. and Q.L.), Science and Technology Leading Talent Program of Yunnan Province (202405AB350002, to Y.W.), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC2307900, to Y.W.), State Key Laboratory Special Fund (2060204, to A.W.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82372225, to A.W., 32370703, to X.D.), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2021-I2M-1-061, 2022-I2M-2-004, and 2023-PT330-01, to A.W., 2022-I2M-1-021, to X.D), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025M772719, to L.Q.), Suzhou Applied Basic Research Program (General Program in Medical and Health Sciences) (SYW2024065, to X.D.), NCTIB Fund for R&D Platform for Cell and Gene Therapy and High-performance Computing Platform of Suzhou Institute of Systems Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L., A.W. and Y.W. conceived, designed, and supervised the experiments; M.Z., Z.L. and Q.H. immunized the animals; L.Q., M.Z., Y.M. and C.B. selected and constructed the representative pseudotyped virus library; M.Z., Z.L., J.C., J.T., H.L. and R.B. performed the neutralization assays; L.Q., M.Z. and J.L. analyzed the experimental data; X.D. and W.H. were supervision; M.Z. and L.Q. wrote the manuscript; All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Vijaykrishna Dhanasekaran and Michael Lassig, for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Qin, L., Li, Z. et al. Dominant substitutions underlying the antigenic evolution of H5 influenza virus. Nat Commun 16, 10708 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65730-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65730-y