Abstract

Stress/strain-temperature sensors are capable of sensing both stress/strain and temperature stimuli, and are widely used in biological health monitoring and human-machine interaction. Conventional stress/strain-temperature sensors are prepared by stacking two single sensors, which have complex structures and often require external power to drive, making long-term stable monitoring challenging. Herein, we demonstrate a flexible single-channel multimodal sensor based on the combined thermoelectric and piezoelectric effects of tellurium nanowires. Based on the tilt-grown reticulated nanowire structure, the sensor can simultaneously sense strain/strain rate and temperature in a single channel of a single active layer of nanowire. The sensor exhibits a record-high strain/strain rate sensing performance with a strain sensing sensitivity of 0.454 V and a strain rate sensing sensitivity of 0.0154 V s, surpassing previous study benchmarks. Additionally, it showcases significant temperature-sensing performance with a sensitivity of 225.1 μV K−1. The origin of the piezoelectric effect of the sensor is attributed, by experimental and computational evidence, to the change in atomic charge when the Te nanowires are bent, and it can be modulated by external electric fields, such as a thermoelectric potential. Our results provide insights for designing and fabricating high-performance flexible single-channel multimodal sensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, advancements in intelligent electronic devices designed for biological health monitoring and human–machine interaction have been remarkable, particularly in terms of increased flexibility, miniaturization, and multifunctional integration1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Among these, flexible stress/strain-temperature sensors, which are capable of perceiving tactile and temperature stimuli simultaneously, have garnered significant attention for their crucial role in the development of electronic skin8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. The most widely developed strategy for designing stress/strain-temperature sensors involves integrating two different materials with stress/strain and temperature sensing capabilities (thermoelectric/pyroelectric and piezoelectric/piezoresistive effects, etc.) into a stacked structure device12,13,14,15,16. For example, Han et al. combined a laser-induced graphene/silicone rubber pressure-sensing layer with a NiO temperature-sensing layer to create a pressure-temperature bimodal sensor, achieving accurate object classification15. Similarly, Chai et al. developed a bimodal sensor to detect vibration and temperature signals by integrating core−sheath piezoelectric nanofibers and pyroelectric nanocomposite films16. However, these kinds of devices typically operate in a one-to-one mode (each sensing signal derived from one functional material), and the complexity of device fabrication and data acquisition limits their widespread application. In comparison, it is more conducive to integration and miniaturization by constructing multimodal sensors based on a single active material with multiple functional properties. Especially when the multiple sensing signals can be simultaneously output through a single channel (one pair of electrodes), this advantage can be further amplified. The single-channel multimodal sensors made from materials that exhibit both pyroelectric and piezoelectric effects have been extensively studied18,19,20. For example, Li et al. developed a flexible hybrid NG based on a PAN/TMAB composite nanofiber film for self-power multifunctional sensors monitoring human physiological signals18. However, since both the pyroelectric and piezoelectric effects arise from the displacement of internal dipoles in the material under external stimuli, which produced alternating stress/strain and temperature sensing signals with similar characteristics. Thus, it is difficult to distinguish these two signals, and the above sensors can only sense strain and temperature separately. Achieving high-precision simultaneous sensing is still a great challenge. Until now, only Song et al. have successfully realized simultaneous pressure-temperature sensing based on the pyro-piezoelectric effect of barium titanate by controlling the difference in response time for these two effects (response time of pyroelectric and piezoelectric voltages were 8.6 s and 0.24 s, respectively)21. This type of sensor, operating in a one-to-multitude mode, inherently features a simplified structure and lower cost. However, its longer response time for temperature sensing and the bulk nature of the active layer hinder its application in flexible electronics.

In comparison, temperature sensors based on thermoelectric effect can realize temperature sensing by using the change of electric potential difference between two ends of thermoelectric material caused by temperature difference. Moreover, the principle of thermoelectric signal generation and the signal characteristic are completely different from those of the pyroelectric signal, which makes it much easier to distinguish between thermoelectric and piezoelectric signals. Therefore, constructing stress/strain-temperature sensors based on a suitable active material with both thermoelectric and piezoelectric effects should have more advantages. Tellurium (Te), an emerging semiconductor material, possesses excellent thermoelectric22,23,24,25,26,27 and piezoelectric properties28,29,30,31,32 simultaneously, which makes it an ideal candidate for developing single-channel stress/strain-temperature sensors. Previous studies have reported that Te nanowires (NWs) exhibit the piezoelectric effect due to piezoelectric polarization when subjected to external stress in the radial direction. For instance, Wang et al. successfully fabricated piezoelectric devices using monolayer nanowires oriented parallel to the substrate surface, generating a piezoelectric signal in the out-of-plane direction28. Meanwhile, when there is a temperature difference between the two ends of the Te NWs, a thermoelectric signal is generated along the Te NWs direction due to the directional transport of carriers. However, the aforementioned Te NWs device, oriented parallel to the substrate surface faces challenges in establishing a stable radial temperature difference out-of-plane due to its small diameter (material thermal resistance generally proportional to the heat-diffusion route length10,13,33,34), thus impeding the generation of a stable thermoelectric signal in the same direction as piezoelectricity through a single channel. Conversely, Li et al. reported the development of thermoelectric devices with an out-of-plane direction by arranging Te NWs arrays perpendicular to the substrate surface. In this configuration, however, the piezoelectric signal cannot be generated in the out-of-plane direction due to the internal electronic polarizations to cancel each other out8. Furthermore, most studies on strain sensing tend to ignore the role of strain rate (the rate of applied strain), which is a key factor in dynamic scenarios. Even under identical strain magnitudes, variations in strain rate significantly influence material responses due to the coupled nature of strain and strain rate. In fact, not only is it difficult to achieve simultaneous outputs of stress/strain-temperature sensing signals through a single channel based on the combination of thermoelectric and piezoelectric effects for Te NWs, but there have also been no reports of this being achieved in other materials.

Here, we present a flexible single-channel strain/strain rate-temperature multimodal sensor (FSSMS) based on the combined thermoelectric and piezoelectric (thermo-piezoelectric) effects of Te NWs. The piezoelectric and thermoelectric signals can be output simultaneously in the out-of-plane direction of the single active layer Te NWs due to the tilt-grown reticulated Te NWs structure. The sensor has a record-high strain/strain rate sensing performance with a strain sensing sensitivity of 0.454 V and a strain rate sensing sensitivity of 0.0154 Vs, which exceeds the benchmarks of previous studies. In addition, it also has a concurrent temperature sensing sensitivity of 225.1 μV K−1 that is highly advantageous among comparable multimodal sensors. Combined with first-principles calculations, we demonstrated that the piezoelectric effect of the sensor originates from the change in the charge of the Te atoms and can be modulated by an external electric field, such as a thermoelectric potential. In addition, we have demonstrated the ability of the sensor to accurately recognize subtle differences in human breathing states. We believe that the thermo-piezoelectric effects are likely existed in nanomaterials of the same type, and the universal design strategy not only provides a new idea for building flexible single-channel multimodal sensors, but is also applicable to the preparation of coupled nanogenerators.

Results

Device fabrication and sensing mechanism

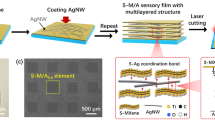

Figure 1a displays the fabrication procedure and multilayer structure of the FSSMS. Te NWs, act as the active component of the sensor, are encapsulated with flexible polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) to prevent short circuits between the top and bottom electrodes as well as to curtail charge leakage29,35,36. Figure 1b and c depict the surface and cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the Te NWs, respectively. As observed, Te NWs are grown on the flexible substrate at an oblique angle and intertwined with each other to form a reticulated structure, providing for excellent flexibility of the device. And the high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscope (HAADF-STEM) image of the Te NWs and the corresponding elemental mapping further illustrate the structure of the device (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Fabrication procedure and multilayer structure of the sensor. ITO stands for indium tin oxide, and PI stands for polyimide. b The top-view and (c) cross-section SEM image of the Te NWs. d The TEM image, (e) high-resolution HAADF-STEM image and (f) SAED pattern of a Te NW. g Crystal structure and (h) cross-sectional view of a Te NW. i The XRD spectrum of the Te NWs. Each micrograph obtained similar results in three independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As shown in Fig. 1d–f, transmission electron microscopy image, high-resolution HAADF-STEM atomic spacing and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern demonstrate the growth of Te NWs along the [001] direction. Along this direction, Te atoms are connected by covalent bonds along their longitudinal 120° helical chains37,38, with weak van der Waals forces between different helical chains and a radially asymmetric central structure(Fig. 1g, h). Furthermore, Fig. 1i presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the Te NWs, which indicated a pure hexagonal phase without any impurity phase.

As shown in Fig. 2a, we observed a distinct thermoelectric voltage when applying a temperature stimulus to the upper surface of the device (Supplementary Fig. 2), which would disappear with the withdrawal of the temperature stimulus. Then, positive piezoelectric signals can be observed when the strain applied to the device and the corresponding negative peaks appeared when the strain is released due to the release of accumulated polarized charges, as depicted in Fig. 2b. Meanwhile, when the electrodes of the device are connected in reverse, the polarity of the output voltage completely reversed (Supplementary Fig. 3a), which also occurs when the external stress changes from tensile to compressive (Supplementary Fig. 3b). These results clearly indicate that the output voltage of the FSSMS under the external stress resulting from piezoelectric effect of the Te NWs. Furthermore, when the device was stimulated by both stress and temperature, we observed the simultaneous output of piezoelectric and thermoelectric voltages in single-channel of single active layer Te NWs, as shown in Fig. 2c.

Measured output voltage signals of the sensor under: (a) temperature stimuli, (b) stress stimuli and (c) stress and temperature stimuli. Simplified charge distribution models for (d) straight Te NW and those bent in the (e) positive ([110]) and (f) negative ([\(\bar1\,\bar10\)]) piezoelectric directions. (g–i) Illustration of the sensor’s sensing mechanism in (a–c). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the above three cases, the mechanism of thermoelectric voltage generation is clearer, while the mechanism of piezoelectric voltage generation in the tilt-grown reticulated Te NWs may be different from that of the ordered arrangement of Te NWs28. To explore the underlying mechanism, the changes of the charge centers of the nanowires before and after bending in different bending directions were calculated and analyzed based on first-principles. Detailed information about the theoretical simulation process is provided in Supplementary Note 1. As shown in Fig. 2d, in the initial state, the positions of the positive and negative charge centers in the radial direction [110] of the nanowires are overlapped. When the nanowire is bent, the charges and positions of Te atoms change, altering the charge distribution and the geometric structure of the positive and negative charge triangles (Supplementary Fig. 4). This breaks the equilibrium between the positive and negative charge centers of the entire nanowire, resulting in their separation, as shown in Fig. 2e. The offset of the charge centers due to the geometric structure changes during nanowire-bending is minimal and can be negligible (Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, the separation of positive and negative charge centers primarily arises from the changes in atomic charge during nanowire-bending. In addition, when changing the bending direction, we found that the positive charge center consistently shifts towards the inner side of the bending, while the negative charge center shifts towards the outer side, as shown in Fig. 2f. Thus, the direction of piezoelectric potential generated by Te NWs with different orientations are the same when bending, resulting in piezoelectric potentials induced between the top and bottom electrodes of the sensor.

Based on the above experimental phenomena and theoretical calculations, we established a simplified Te NWs model to investigate the source of output signals in FSSMS. When the device is subjected to temperature stimuli (Fig. 2g), the holes carrier will diffuse along the Te NWs from the hot end to the cold end, leading to the accumulation of hole carriers at the cold end and generating a thermoelectric potential. Furthermore, when the device is subjected to an external force (Fig. 2h), the Te NWs bend slightly, leading to the separation of the positive and negative charge centers and generating a potential difference between the two ends due to piezoelectric polarization. Once the external force is removed, the piezoelectric polarization disappears, resulting in a reverse pulse signal39,40,41,42. Additionally, when the device is exposed to both stress and temperature stimuli (Fig. 2i), piezoelectric and thermoelectric potentials are generated simultaneously in the out-of-plane direction. Consequently, the sensor enables simultaneous sensing of both temperature and stress/strain.

Strain/strain rate sensing performance of the FSSMS

To illustrate the strain/strain rate sensing performance, the key parameters of the sensor like sensing sensitivity, response time, and stability are systematically investigated. Detailed calculations regarding the device’s strain assessment are elucidated in Supplementary Note 2. As depicted in Fig. 3a, as the applied strain varies from 0.044% to 0.308% (strain rate = 4.3% s−1), the output voltage increases in positive correlation from 0.31 mV to 1.01 mV, this trend is verified in the calculation (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 6). And the stable output voltage across three repeated tests at each strain demonstrates robust sensing reproducibility, the slight variation in the piezoelectric sensing signals over cycles can be attributed to errors in the mechanical drive system. Further study shows that the output voltage is also related to the strain rates. As shown in Fig. 3b, the output voltage increases from 0.59 mV to 1.10 mV as the strain rate increases from 1.72% s−1 to 5.59% s−1 (strain = 0.264%). This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the strain determines the extent of piezoelectric polarization while the strain rate influences the accumulation time of polarized charges. According to Ohm’s law \(U={IR}=\frac{Q}{t}R\), where U is the voltage, I is the current, R is the resistance, Q is the charge, and t is the time required for the charge Q to pass, the charge Q is proportional to the peak area (the integral of voltage over time). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, two piezoelectric outputs with identical strain magnitudes but different strain rates exhibit consistent peak areas, indicating that the charge Q depends solely on strain. Therefore, larger strains induce greater piezoelectric polarization, resulting in higher charge Q (larger peak area), while higher strain rates shorten the charge accumulation/release time t (narrower peak width), and thus the peak voltage (peak height) depends on both strain and strain rate39,40,41,42.

Measured output voltage signals under (a) different strain with a fixed strain rate of 4.3% s−1 and (b) different strain rate with a fixed strain of 0.264%. Strain-dependent statistic voltage under different strain rates (c) (V1 = 1.72% s−1, V2 = 2.15% s−1, V3 = 2.58% s−1, V4 = 3.01% s−1, V5 = 3.44% s−1, V6 = 3.87% s−1, V7 = 4.3% s−1, V8 = 4.73% s−1, V9 = 5.16% s−1 and V10 = 5.59% s−1) and strain rate-dependent voltage under different strain (d). The error bars (mean ± standard deviation) were obtained based on three independent tests. Stability depending on the (e) cycle and (f) frequency of the device. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The relationship between different strain/strain rate and piezoelectric output voltage was further studied (Supplementary Fig. 8). Figure 3c plot the change in the output voltage with varying strains under different strain rates. As strain increases, the voltage signals first increase and then tend to be stable. This may be due to the fact that the piezoelectric polarization approaches saturation when the strain is large, and further increase in strain leads to a decrease in the polarization growth rate. The region where the output voltage varies linearly with the strain is defined as the effective sensing region of the device and the strain sensing sensitivity is defined as the output voltage per unit strain43. As the strain rate increases from 1.72% s−1 to 5.59% s−1, the strain sensing sensitivity increases from 0.337 V to 0.454 V, which is ~5 times larger than the recently reported values43. Simultaneously, the strain sensing region expands from 0.044% - 0.176% to 0.044% - 0.308%, resulting the sensitivity in the large strain region from 0.176% to 0.308% increases from 0 V to 0.158 V. The increase in strain sensing sensitivity and region can be attributed to the fact that the increment in output voltage with variation strain is different for different strain rates, which is greater at higher strain rates (shorter polarization charge accumulation time)44. Figure 3d plot the change in output voltage with varying strain rates under different strains. As the strain rate increases, there’s a concurrent rise in the voltage signals. Strain rate sensing sensitivity, defined as the output voltage per unit strain rate, ascends from 0.0022 V s to 0.0154 V s as the strain increases from 0.044% to 0.396%. This increase aligns with the larger output voltage increments observed at higher strain rates under increasing strain conditions, corroborating the trend in strain sensing sensitivity with increasing strain rate.

Beyond sensing sensitivity, both response time and stability are pivotal for practical device applications. The FSSMS exhibits a rapid piezoelectric response of approximately 0.1 s at 0.264% strain and 4.3% s−1 strain rate (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Furthermore, the device’s output voltage was not deteriorated across 1000 test cycles, as well as not significantly affected when the driving frequency increased from 0.4 Hz to 1.8 Hz, as shown in Fig. 3e, f. The slight decrease in output signal observed under the action of 1.8 Hz may be attributed to the inability of piezoelectric charge realignment to keep pace with the rapidly varying external stimulation as bending frequency increases17,45. The piezoelectric output performance of three independent sensors was compared (Supplementary Fig. 10a), and the standard deviation of their output voltages was less than 5%, indicating that the sample-to-sample variation between sensors and across batches was very small. And there was no decrease in the output voltage of the sensors after 6 months and 1 year under the same strain conditions (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Meanwhile, due to the encapsulation of the sensor, general environmental changes will not affect its sensing performance (Supplementary Fig. 11). This shows that the FSSMS has excellent stability in strain/strain rate sensing performance.

Due to the coupling between strain and strain rate, the effect of strain rate in strain sensing is obviously an issue that cannot be ignored. In order to illustrate its ability to effectively detect external stimuli under unknown conditions, a decouple strategy between strain and strain rate was further investigated as follows:

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12a, we counted the peak areas at different strain rates and different strains, so by fitting the relationship between peak area and strain we can determine the strain magnitude from the peak area of the output signal. Secondly, although the piezoelectric signal itself does not directly reflect the strain rate, it can be analyzed under specific conditions with the signal characteristics. It can be found from Figs. 3c, d that the sensor is insensitive to small strain rate of 1.72% s−1 - 2.58% s−1 under the small strain of 0.044% - 0.132%, and large strain (> 0.132%) under the small strain rate of 1.72% s−1 - 2.58% s−1, and therefore the strain rate can be determined directly from the output voltage in these ranges. Then in the large strain rate range (2.58% s−1 - 5.59% s−1), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 12b, the response time decreases linearly with increasing strain rate. Thus, the strain rate can be determined by measuring the response time of the piezoelectric signal.

Temperature sensing performance of the FSSMS

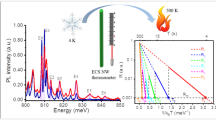

Figure 4a shows the sensing performance with three on/off cycles for each temperature difference. It can be observed that the output voltage increases as temperature difference increases from 0.4 K to 6.3 K. However, the signal of the device cannot be immediately recovered under a large temperature difference (ΔT ≥ 2.5 K), which is different from the change under small temperature difference. Due to the slow thermal diffusion of PDMS (α ≈ 0.1 mm²/s) and PI (α ≈ 0.1 mm²/s) in the multilayer structure, the heat input from a large temperature difference takes a longer time to dissipate, resulting in a longer overall thermal equilibrium time, which is manifested as a delay in signal recovery10,17,46. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 13, the recovery time of temperature sensing is significantly shortened when the sensor is equipped with a heat sink, which confirms this mechanism. The heat sink enhances the overall heat dissipation effect of the device and shortens the time it takes for the temperature difference between the upper and lower surfaces of the device to reach equilibrium.

a Measured output voltage signals under different temperature difference. b Representative voltage values of the device under the different temperature difference. The red line is the fitted curve, exhibiting a sensitivity of 225.1 µV K−1. The R-squared value for the linear fit is 0.99933. The error bars (mean ± standard deviation) were obtained based on three independent tests. c Minimum detectable temperature difference of 0.1 K. d The time-resolved response of the device, with the red and blue zones corresponding to the response and relaxation time, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, the three test cycles at every temperature difference demonstrate stable voltage output, indicating excellent sensing repeatability. Fig. 4b shows that the output voltage linearly increased with increasing temperature difference across the FSSMS. The calculated temperature sensing sensitivity is about 225.1 μV K−1 based on the equation \(S=\Delta V/\Delta T\), where ∆V is thermoelectric voltage and ∆T is the temperature difference across the device. This value is slightly lower than the in-plane Seebeck coefficient (Supplementary Table 1, ~260 μV K−1) of the fabricated Te NWs, but surpasses the previous similar temperature-stress/strain dual sensor studies12,13,17. To further illustrate the advantages of the devices in terms of sensing performance, a comprehensive comparison with recent temperature-pressure and strain/strain rate sensors was performed, as shown in Supplementary Table 2. There is still room for improving sensor performance by adjusting the growth parameters of Te NWs. Te NWs with varying morphologies were synthesized by adjusting growth temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 14). While vertically aligned Te NWs exhibit enhanced temperature sensitivity (Supplementary Fig. 14a, d), the piezoelectric signals were difficult to obtain due to the internal electronic polarizations to cancel each other out8. Therefore, the tilted Te NWs prepared at 623 K in this paper are the optimal configuration to obtain simultaneous thermoelectric and piezoelectric signals in the out-of-plane direction. In addition, Fig. 4c illustrates that the device can detect a minimum temperature difference of 0.1 K at room temperature. The temperature sensing of the sensor is stable at large temperature differences of 20 K (Supplementary Fig. 15).

The response time is a key parameter to evaluate the temperature sensing performance of the sensor. Owing to the out-of-plane structure design, the device shows an immediate response to the applied temperature stimuli. The temperature response and recovery time measured at ∆T = 1.4 K are 1.69 s and 3.58 s, respectively (Fig. 4d), which are consistent with those of many commercial and previously reported temperature sensors11,26. It is worth noting that both the sensitivity and response time of the FSSMS can meet the requirements of many artificial intelligent systems.

Strain/strain rate-Temperature sensing performance of the FSSMS

To investigate the temperature and strain/strain rate simultaneous sensing capability of the FSSMS, a series of experiments have been designed under different strain/strain rate and temperature conditions. The slight baseline shift in temperature sensing may be attributed to the very low heat diffusion rate of the polymer in the multilayer film structure and the temperature fluctuations that occur in the bending process due to radiant heating47. Figure 5a and b respectively, show the output voltage depending on the applied strain (strain rate = 4.3% s−1) and strain rate (strain = 0.264%) at ∆T = 2.5 K. Due to the apparently independent operating processes of the thermoelectric and piezoelectric effects, their output signal types are direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC) pulse signals, respectively. The thermo-piezoelectric effect enhances the electrical output performance of the device, and the DC thermoelectric signals are superimposed with the AC piezoelectric signals. The magnitudes of these two signals are comparable, making it easier to distinguish between them and facilitating multimodal sensing in our device. The peak voltage of the thermoelectric signal reflects the magnitude of the temperature difference between the upper and lower surfaces of the device, while the difference between the peak voltage of the piezoelectric signal and the peak voltage of the thermoelectric signal reflects the magnitude of the applied strain/strain rate under the corresponding temperature difference.

Measured output voltage signals of different strain under 4.3% s−1 strain rate (a) and different strain rate under 0.264% strain (b) when ΔT = 2.5 K. Statistic voltage values of different temperature difference and different strain under 4.3% s−1 strain rate (c) and different strain rate under 0.264% strain d. The error bars (mean ± standard deviation) were obtained based on three independent tests. e Effect of external electric field on the positions of positive and negative charge centers in a bent nanowire. (i) Schematic model of the bent Te NW. Distribution of positive and negative charge centers: (ii) without an electric field, (iii) with an electric field aligned with the piezoelectric direction of bending, and (iv) with an electric field opposite to the piezoelectric direction of bending. f Electric dipole moment along the [110] lattice direction of bent Te NW under an external electric field. 1 a.u. = 1 Hartree/e/Bohr = 51.4 V/ang. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In order to further investigate the performance of the thermo-piezoelectric effect in the device, the variations in the piezoelectric signal component under different temperature differences in response to strain and strain rate were studied. These results are presented in Fig. 5c and d, with additional details available in Supplementary Fig. 16. The corresponding measurement process is recorded in Supplementary Movie 1. Under different temperature differences, both strain and strain rate sensing exhibit effective positive correlation, and there is no observed change in response time (Supplementary Fig. 9). It should be mentioned that the piezoelectric signals show a slight decrease in sensitivity compared to that at 0 K temperature difference condition, which can be attributed to the influence of thermoelectric potential generated by a temperature difference on the displacement of positive and negative charge centers within the Te NWs. Fig.5e simulated the changes in the displacement of positive and negative charge centers within the Te NW under an external electric field. As the Fig. 5e(iii) show, when the electric direction aligns with the piezoelectric potential direction during bending, the displacement of the positive and negative charge centers decreases, leading to a reduction in the piezoelectric potential. And this suppression effect becomes more pronounced with increasing external electric field strength (Supplementary Fig. 17). Conversely, when the direction of the external electric field opposes the piezoelectric potential generated during bending (Fig. 5e(iv)), the displacement of the charge centers increases, resulting in an enhancement of the piezoelectric potential. As shown in Fig. 5f, the effect of the external electric field on the piezoelectric potential increases as the degree of bending increases, which is why the greater the strain under the thermoelectric potential in Fig. 5c, the greater the degree of decrease in the piezoelectric voltage. Moreover, our experimental observations reveal that merely altering the direction of the piezoelectric potential (the bending direction) can lead to a notable increase in the piezoelectric potential (Supplementary Fig. 18). Remarkably, even with a temperature difference as high as 6.3 K, it still maintains a remarkable high strain sensing sensitivity of 0.313 V at 4.3% s−1 strain rate (0.022% - 0.132% strain), while the strain rate sensing exhibits a sensitivity of 0.0101 V s under 0.264% strain. Furthermore, due to the difference in the nature of the thermoelectric signal and the piezoelectric signal, when strain/strain rate sensing under temperature coupling is required, we can decouple the temperature and strain/strain rate sensing by fitting the strain and strain rate sensing data under different temperature differences separately, as shown in Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 19. We also verified the effectiveness of the decoupling strategy when the temperature and strain/strain rate varied simultaneously over a wide range (Supplementary Fig. 20), as shown in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4. The 20% error in strain sensing arises from experimental error and discrepancies between the derived equation for reference strain and the decoupling equation for sensing strain. This error level is within reasonable limits compared to literature values and can be reduced in the future by refining the strain decoupling function44,48,49,50,51,52. This not only indicates that the FSSMS has high strain/strain rate sensing sensitivity and fast response time at different temperatures, thus ensuring the simultaneous strain/strain rate and temperature sensing ability, but also provides a new idea for regulating the piezoelectric output.

The potential applications of the FSSMS as a self-powered physiological signal sensor are further explored by monitoring various human breathing states. The device’s output voltage during normal and deep breath of an adult male at room temperature (302.9 K) is shown in Supplementary Fig. 21a and b. Comparing normal and deep breaths reveals nuances: slower and more consistent exhalation during deep breathing results in a slightly weaker piezoelectric signal. And according to the results in Fig. 3b for a room temperature of about 302.9 K, it can be inferred that the measured temperature peaks for normal breath and deep breath of the air in the human lungs were approximately 305.1 K and 306.6 K respectively, which is consistent with the actual temperature measured by the thermocouple (Supplementary Fig. 22). The corresponding measurement process is recorded in Supplementary Movie 2. Furthermore, when the device is directly exposed to sunlight, only positive thermoelectric signals are achieved without any piezoelectric signal. (Supplementary Fig. 21c). This result not only confirms that the piezoelectric signal during breath indeed arises from the strain exerted on the device by the exhaled air, but also suggests the device’s potential for photothermoelectric sensing applications. We also tested the electric output when the electrodes of the device were reverse connected during the demonstration experiments, providing evidence of signal authenticity (Supplementary Fig. 21d–f).

In order to more visually demonstrate the unique advantages of the sensor’s temperature-strain/strain rate multimodal sensing, we provide a conceptual demonstration of breath-monitoring by integrating the sensor into a gas mask, as shown in Fig. 6a and b. This enables health status monitoring in extreme working environments where masks are required due to stringent protective requirements. As shown in Fig. 6c–f, our device can monitor breathing patterns and rate through the thermoelectric and piezoelectric effects, respectively. The results demonstrate four breathing states like deep breathing, normal breathing, rapid breathing and slow breathing. When the sensor detects an accelerated breathing rate and an increased frequency of deep breathing, it may indicate an abnormal physiological condition and trigger an alarm. Thus, we can utilize the sensor’s powerful strain/strain rate and temperature sensing capabilities to monitor human breathing status and differentiate between other stimuli in real time and accurately.

a Demonstration of practical sensing. b Optical photo of the sensor integrated into a gas mask. Measured output voltage signals under (c) normal slow breathing, (d) normal rapid breathing, (e) deep slow breathing, and (f) deep rapid breathing. The inset shows the amplification of the piezoelectric signal; the red zone represents the response time. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In summary, we developed a strategy to fabricate flexible single-channel multimodal sensors using tilt-grown reticulated Te NWs to realize the combination of thermoelectric and piezoelectric effects, thus enabling simultaneous sensing of strain/strain rate and temperature within a single channel. We also verified that piezoelectric polarization in Te NWs during bending primarily arises from changes in atomic charge and can be modulated by external electric fields, such as thermoelectric potential. In addition, we demonstrate that the sensor possesses the ability to monitor different breathing states in humans. It is reasonable to believe that the thermo-piezoelectric effect is also present in other nanomaterials of the same type, such as selenium nanowires and zinc oxide nanowires, and thus, this design strategy is generalizable. Our work not only paves the way for the design and fabrication of flexible single-channel multimodal sensors but also has important implications for the development of coupled nanogenerators.

Methods

Materials and device preparation

A SiO2 layer was deposited on an ITO/ PI substrate using electron beam evaporation, which had been pre-cleaned sequentially with acetone, alcohol, and deionized water and then dried with a stream of air. Te NWs were prepared through a thermal evaporation process in a tube furnace. High-purity Te powder (99.99%, 200 mesh) served as the evaporation source. The temperature was ramped from room temperature to 573 K at a rate of 15 K/min and then further increased to 623 K at a rate of 5 K/min, with a 20 min dwell time at 623 K. High-purity Ar gas (40 sccm) was used as a carrier gas, maintaining a pressure of 20 - 30 Pa. The substrate, after masking, was placed on a glass slide in the insulating zone of the tube furnace, at a distance of 28 cm from the evaporation source. Subsequently, the sample was cooled as the furnace temperature decreased. A PDMS (ratio of 10:1) layer was spin-coated and cured. A Au layer was deposited as the top electrode using magnetron sputtering. Finally, the masking tape was removed, completing the fabrication of the sensor. No formal approval for the experiments involving human volunteers in Fig. 6 was required, which was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Metal Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences. A 25-year-old male volunteer took part following informed consent.

Measurement of the film and the sensor

The microstructures of the samples were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SU-70, Hitachi), X-ray diffraction (D8 Discover, Bruker), and a double spherical aberration corrected transmission electron microscope (Spectra 300, Thermoscientific). The in-plane Seebeck coefficient, α, and electrical conductivity, σ, were measured by a Netzsch SBA-458 system under Ar + H2 (5%) gas protection. For the electrical measurements, two Au wires were connected to conductive electrodes as leads. During the strain and strain rate sensing test, the ac servo motor (MHMF012L1U2M, Panasonic) was employed to drive displacement. During the temperature sensing test, a Source Meter (Keithley 2450) and PID control (SET-217, Shenzhen Fanyuhang Automation Equipment Co., Ltd.) were employed to control the temperature of the heater. The temperature is read by a digital thermometer (AZ8852, AZ instrument). The Seebeck and piezoelectric voltage generated by the sensor was recorded using a Keithley 6500 digital multimeter. The sunlight testing from the illumination of a solar simulator (Newport 94021 A). The strain/strain rate-temperature sensing performance measurements were all performed using lab-built test equipment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Yang, Y. Hybridized and coupled nanogenerators: design, performance, and applications vol. 1 overview Ch. 1 (Wiley-VCH GmbH, 2020).

He, Y., Cheng, Y., Yang, C. & Guo, C. F. Creep-free polyelectrolyte elastomer for drift-free iontronic sensing. Nat. Mater. 23, 1107–1114 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ultrafast piezocapacitive soft pressure sensors with over 10 kHz bandwidth via bonded microstructured interfaces. Nat. Commun. 15, 3048 (2024).

Kim, S. et al. Synergetic enhancement of the energy harvesting performance in flexible hybrid generator driven by human body using thermoelectric and piezoelectric combine effects. Appl. Surf. Sci. 558, 149784 (2021).

Zhang, H., Li, H. & Li, Y. Biomimetic electronic skin for robots aiming at superior dynamic-static perception and material cognition based on triboelectric-piezoresistive effects. Nano Lett. 24, 4002–4011 (2024).

Wang, L., Qi, X., Li, C. & Wang, Y. Multifunctional tactile sensors for object recognition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2409358, 10.1002/advs.202402705 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Flexible temperature sensor with high reproducibility and wireless closed-loop system for decoupled multimodal health monitoring and personalized thermoregulation. Adv. Mater.2407859, 10.1002/adma.202407859 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Dual sensing signal decoupling based on tellurium anisotropy for VR interaction and neuro-reflex system application. Nat. Commun. 13, 5975 (2022).

He, C. et al. An ionic assisted enhancement strategy enabled high performance flexible pressure–temperature dual sensor. Nano Lett. 24, 7040–7047 (2024).

Yu, H. et al. Flexible temperature-pressure dual sensor based on 3D spiral thermoelectric Bi2Te3 films. Nat. Commun. 15, 2521 (2024).

Zhang, F., Zang, Y., Huang, D., Di, C. & Zhu, D. Flexible and self-powered temperature–pressure dual-parameter sensors using microstructure-frame-supported organic thermoelectric materials. Nat. Commun. 10 10.1038/ncomms9356 (2015).

Zhu, P. et al. A flexible active dual-parameter sensor for sensitive temperature and physiological signal monitoring via integrating thermoelectric and piezoelectric conversion. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 8258–8267 (2019).

Zhu, P. et al. Flexible 3D architectured piezo/thermoelectric bimodal tactile sensor array for e-skin application. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001945 (2020).

Ma, X. et al. Bimodal tactile sensor without signal fusion for user-interactive applications. ACS Nano 16, 2789–2797 (2022).

Han, S. et al. All resistive pressure–temperature bimodal sensing E-skin for object classification. Small 2301593, 10.1002/smll.202301593 (2023).

Chai, B. et al. Integrated piezoelectric/pyroelectric sensing from organic–inorganic perovskite nanocomposites. ACS Nano 18, 25216–25225 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. 3D geometrically structured PANI/CNT-decorated polydimethylsiloxane active pressure and temperature dual-parameter sensors for man–machine interaction applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 15167–15176 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Flexible piezoelectric and pyroelectric nanogenerators based on PAN/TMAB nanocomposite fiber mats for self-power multifunctional sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 46789–46800 (2022).

Wang, K., Liu, Q., Zhang, Q., Xiang, Y. & Hu, X. Display integrated flexible and transparent large-area pyroelectric gesture recognition/piezoelectric touch control sensor array based on in-situ polarized PVDF-TrFE films. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 357, 114406 (2023).

Yin, R. et al. High-temperature flexible electric piezo/pyroelectric bifunctional sensor with excellent output performance based on thermal-cyclized electrospun PAN/Zn(Ac)2 nanofiber mat. Nano Energy 124, 109488 (2024).

Song, K., Zhao, R., Wang, Z. L. & Yang, Y. Conjuncted pyro-piezoelectric effect for self-powered simultaneous temperature and pressure sensing. Adv. Mater. 31, 1902831 (2019).

Lin, S. et al. Tellurium as a high-performance elemental thermoelectric. Nat. Commun. 7, 10287 (2016).

Bhuiyan, M., Sobhan, K. M. A., Ali, M. & Khan, K. A. Temperature effect of the electrical properties of tellurium thin films. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 1, 57–60 (2000).

Qiu, G. et al. Thermoelectric performance of 2D tellurium with accumulation contacts. Nano Lett. 19, 1955–1962 (2019).

Gao, Z., Tao, F. & Ren, J. Unusually low thermal conductivity of atomically thin 2D tellurium. Nanoscale 10, 12997–13003 (2018).

Yang, Y., Lin, Z.-H., Hou, T., Zhang, F. & Wang, Z. L. Nanowire-composite based flexible thermoelectric nanogenerators and self-powered temperature sensors. Nano Res 5, 888–895 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of van der Waals tellurium via vacancy engineering. Mater. Today Phys. 18, 100379 (2021).

Lee, T. I. et al. High-power density piezoelectric energy harvesting using radially strained ultrathin trigonal tellurium nanowire assembly. Adv. Mater. 25, 2920–2925 (2013).

Kou, J. et al. Nano-force sensor based on a single tellurium microwire. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 32, 074001 (2017).

Selamneni, V., Akshaya, T., Adepu, V. & Sahatiya, P. Laser-assisted micropyramid patterned PDMS encapsulation of 1D tellurium nanowires on cellulose paper for highly sensitive strain sensor and its photodetection studies. Nanotechnology 32, 455201 (2021).

Apte, A. et al. Piezo-response in two-dimensional α-tellurene films. Mater. Today 44, 40–47 (2021).

Gao, S., Wang, Y., Wang, R. & Wu, W. Piezotronic effect in 1D van der Waals solid of elemental tellurium nanobelt for smart adaptive electronics. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 32, 104004 (2017).

Landry, E. S. & McGaughey, A. J. H. Effect of film thickness on the thermal resistance of confined semiconductor thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 107, 013521 (2010).

Subramani, S. & Devarajan, M. Thermal resistance of high power LED influenced by ZnO thickness and surface roughness parameter. Microelectron. Int. 33, 15–22 (2016).

Zhou, J. et al. Flexible piezotronic strain sensor. Nano Lett. 8, 3035–3040 (2008).

Wu, J. M., Lee, C. C. & Lin, Y. H. High sensitivity wrist-worn pulse active sensor made from tellurium dioxide microwires. Nano Energy 14, 102–110 (2015).

Mohanty, P., Kang, T., Kim, B. & Park, J. Synthesis of single crystalline tellurium nanotubes with triangular and hexagonal cross sections. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 791–795 (2006).

Oliveira, J. F., Enderlein, C., Fontes, M. B. & Baggio-Saitovitch, E. The pressure-dependence of the band gap of tellurium. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1609, 012013 (2020).

Qiu, Y. et al. Flexible piezoelectric nanogenerators based on ZnO nanorods grown on common paper substrates. Nanoscale 4, 6568 (2012).

Yang, R., Qin, Y., Dai, L. & Wang, Z. L. Power generation with laterally packaged piezoelectric fine wires. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 34–39 (2009).

Chang, C., Tran, V. H., Wang, J., Fuh, Y.-K. & Lin, L. Direct-write piezoelectric polymeric nanogenerator with high energy conversion efficiency. Nano Lett. 10, 726–731 (2010).

Jeong, C. K. et al. Nanowire-percolated piezoelectric copolymer-based highly transparent and flexible self-powered sensors. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 25481–25489 (2019).

Song, J. et al. Stretchable strain and strain rate sensor using kirigami-cut PVDF film. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2201112 (2023).

Qiu, Y. et al. The frequency-response behaviour of flexible piezoelectric devices for detecting the magnitude and loading rate of stimuli. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 584–594 (2021).

Hu, M. et al. Machine learning-enabled intelligent gesture recognition and communication system using printed strain sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 51360–51369 (2023).

Hu, R., Li, J., Wu, F., Lu, Z. & Deng, C. A dual function flexible sensor for independent temperature and pressure sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 491, 152135 (2024).

Kim, S., Hyeon, D. Y., Lee, D., Bae, J. H. & Park, K.-I. Fully flexible thermoelectric and piezoelectric hybrid generator based on a self-assembled multifunctional single composite film. Materials Today Physics 101103, 10.1016/j.mtphys.2023.101103 (2023).

Bernini, R. et al. Identification of defects and strain error estimation for bending steel beams using time domain Brillouin distributed optical fiber sensors. Smart Mater. Struct. 15, 612–622 (2006).

Li, S., Liu, G., Wang, L., Fang, G. & Su, Y. Overlarge gauge factor yields a large measuring error for resistive-type stretchable strain sensors. Adv. Elect. Mater. 6, 2000618 (2020).

Li, W., Huang, Y., Liu, Z. & Liu, L. Study on influencing factors of synergistic deformation between built-in strain sensor and asphalt mixture. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01993 (2023).

Yang, H. et al. Computational design of ultra-robust strain sensors for soft robot perception and autonomy. Nat. Commun. 15, 1636 (2024).

Moriche, R., Jiménez-Suárez, A., Sánchez, M., Prolongo, S. G. & Ureña, A. Sensitivity, influence of the strain rate and reversibility of GNPs based multiscale composite materials for high sensitive strain sensors. Compos. Sci. Technol. 155, 100–107 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant 2017YFA0700702 to K.P.T.); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 52073290 to K.P.T.); Liaoning Province Key Research and Development Program Project (2025JH2/102800016 to K.P.T.); Liaoning Province science and technology plan project (2025-MS-077 to Z.Y.); Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of Liaoning Province (2023JH6/100500004 to K.P.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z., Z.X., Z.Y., and K.P.T. designed the research project and supervised the experiment. H.Z. and Z.Y. carried out experiments and analysed data. H.Z. wrote the manuscript. W.H.L., J.T.W., and N.G. conducted the simulations. T.X., J.T., H.L.Y., J.H., Y.J.S., S.Q.L., D.Y.Z. and Y.Z. contributed to samples preparation or characterizations. All authors discussed, revised, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jian-Wei Liu, Jianwei Zhang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, H., Li, W., Wang, J. et al. Simultaneous strain, strain rate and temperature sensing based on a single active layer of Te nanowires. Nat Commun 16, 10771 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65815-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65815-8