Abstract

Sustaining malaria control in Africa is imperilled by the rapid evolution of insecticide resistance in the major vector Anopheles gambiae. Although current genomic and transcriptomic approaches map known resistance alleles, they often lack predictive power to anticipate liabilities to new insecticides. We present a predictive functional chemoproteomic framework integrating competitive activity-based protein profiling with functional validation to identify enzyme-mediated resistance mechanisms before they arise in field populations. Applied to a susceptible Anopheles gambiae strain, fluorophosphonate probe profiling with pirimiphos-methyl-oxon, the bioactive metabolite of the organophosphate pirimiphos-methyl, revealed 18 active serine hydrolases. The carboxylesterase Coeae6g was selected for further functional analysis because it had previously been shown to be associated with pyrethroid and carbamate resistance. Functional assays confirmed Coeae6g confers resistance to pirimiphos-methyl and mediates cross-resistance to malathion, bendiocarb, and permethrin. These findings bridge genotype–phenotype gaps, align with emerging field genomic signatures, and establish a scalable framework to complement genomic surveillance and guide insecticide management in malaria vector control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria is a deadly mosquito-borne disease that caused an estimated 263 million cases and 597,000 deaths in 2023, with the majority occurring in sub-Saharan Africa1. Frontline control measures, such as pyrethroid-treated bed nets, are increasingly threatened by widespread and rising pyrethroid resistance in major vectors like Anopheles gambiae1,2. This escalating resistance crisis underscores the urgent need for alternative, resistance-informed vector control strategies1,3. One such alternative is pirimiphos-methyl (PM), an organophosphate (OP) insecticide used in Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) formulations such as Actellic® 300CS, which has gained widespread deployment due to its prolonged residual activity and historically low resistance levels in Anopheles populations4,5,6. However, emerging reports from West Africa indicate increasing resistance to PM. The development of such resistance is likely accelerated by the extensive genetic diversity within An. gambiae populations, which facilitates rapid adaptation to insecticide pressure7,8. Early identification of resistance mechanisms, combined with proactive surveillance, is therefore essential to contain the spread of resistance and sustain the efficacy of current interventions.

PM is a pro-insecticide requiring bio-activation by cytochrome P450 enzymes, monooxygenases (P450s), a large detoxification enzyme family, into its toxic metabolite, pirimiphos-methyl oxon (PMO). PMO irreversibly inhibits acetylcholinesterase (AChE), encoded by the Ace1 gene, an enzyme essential for neurotransmission9,10,11. Resistance arises through multiple mechanisms, including mutations and duplications in Ace1 and the overexpression of detoxifying enzymes8,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. P450s detoxify organophosphates through oxidative metabolism. Carboxylesterases (CCEs) either hydrolyze ester bonds to inactivate the insecticide or sequester organophosphates through phosphorylation of the enzyme active site, thereby neutralizing their activity.

In An. gambiae, members of the CCE family (containing greater than 50 genes) have been strongly associated with resistance to organophosphates and carbamates, and in some cases, pyrethroids. Understanding the specific enzymatic interactions involved in resistance to PM and PMO is critical for developing effective resistance management strategies.17,23,24,25.

Conventional strategies for elucidating resistance mechanisms predominantly rely on transcriptomic and genomic profiling of resistant mosquito populations to identify candidate genes, followed by downstream functional validation26,27,28. While informative, these approaches are intrinsically retrospective, offering mechanistic insights only after resistance has become established. To address this, there is a critical need for more proactive functionally driven methodologies capable of detecting early resistance liabilities in phenotypically susceptible populations before they become widespread. In this study, we developed and implemented a chemoproteomics approach leveraging activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) to functionally map resistance-associated enzymes in An. gambiae before the onset of detectable resistance phenotypes (Fig. 1). Specifically, we employed fluorophosphonate (FP) probes that covalently label active serine hydrolases (SHs), enabling competitive displacement by PM and its oxidized metabolite PMO. This enabled direct profiling of functional insecticide targets and enzyme activity in the native PM-susceptible proteome, revealing early resistance drivers. Among the enzymes identified, we prioritized the carboxylesterase Coeae6g to investigate its role in PM resistance, as its function beyond known association with pyrethroid/carbamate resistance was unclear29. Corroborating our ABPP findings, subsequent biochemical validation and over-expression in transgenic mosquito strains confirmed that Coeae6g confers resistance to PM and mediates cross-resistance to malathion and additional insecticide classes. Together, these findings highlight ABPP as a robust and predictive platform that complements genomic approaches. By enabling early detection of resistance mechanisms, ABPP strengthens the foundation for targeted, evidence-based vector control strategies in malaria-endemic regions.

a Homogenates from insecticide-susceptible An. gambiae (Kisumu strain) are prepared and centrifuged to obtain lysates. Samples are preincubated with the active organophosphate metabolite pirimiphos-methyl oxon (PMO), followed by treatment with a desthiobiotin-conjugated fluorophosphonate (FP) probe. FP-labelled active and heat-denatured homogenates serve as positive and negative controls, respectively. b SH labelling mechanism: FP probes target the conserved catalytic triad (Ser-His-Asp) of serine hydrolases (SHs), irreversibly binding to the nucleophilic serine residue. FP-labelled proteins from PMO-treated and control groups are enriched, purified, and on-bead digested for downstream peptide analysis. Proteins are analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for identification and quantification. The resulting PMO-specific protein targets are validated by comparison of intensity signals in PMO-treated samples versus FP treatment and heat desaturated controls. c Chemical structures of FP probes and d organophosphate inhibitors, including pirimiphos-methyl (PM) and pirimiphos-methyl oxon (PMO). Created with BioRender (Ismail, H. (2025); https://BioRender.com/y61m555) and chemical structures of probes and inhibitors were created using ChemOffice version 22.0.

Results

Cross validation of FP probes for profiling An. gambiae serine hydrolase activity

We employed a dual-probe ABPP strategy to profile serine hydrolase (SH) activity in the insecticide-susceptible An. gambiae Kisumu strain (Fig. 2). A TAMRA-tagged fluorophosphonate (T-FP) probe enabled in-gel fluorescence detection, while a desthiobiotin-FP probe facilitated affinity enrichment and MS-based target identification. T-FP labelling revealed strong, activity-dependent signals in mosquito homogenates, which were abolished to minimal background level by heat denaturation and absent in DMSO controls (Fig. 2a). Prominent bands at ~62–70 kDa, consistent with esterases, were markedly reduced upon pre-incubation with PM or its bioactive metabolite PMO at both 10 and 100 µM, indicating shared target engagement. Although differences between the two concentrations were subtle, dose–response analysis confirmed PMO’s higher potency (IC₅₀ ~0.83 µM) relative to PM (IC₅₀ ~10.55 µM; Supplementary Fig. 1). Notably, PMO also diminished a distinct ~90 kDa band not affected by PM, suggesting unique target binding. The desthiobiotin-FP probe effectively competed with T-FP at both 1× and 5× concentrations, validating its use for proteomic enrichment, although minor differences in ~28–38 kDa bands were observed. These findings demonstrate the robustness and complementarity of both probes for SH profiling in An. gambiae.

a Fluorescent gel image showing TAMRA-FP (tetramethylrhodamine fluorophosphonate) probe labelling of An. gambiae adult female lysates under various conditions. Lanes 1–12 represent treatments with DMSO (control), a non-fluorescent control probe desthiobiotin-conjugated FP probe (2 or 10 μM), competitive inhibitors (PM or PMO at 10 or 100 μM), or heat-denatured lysates subsequently labelled with 2 μM TAMRA-FP at 30 °C. Mosquito homogenate preparations and subsequent ABPP analyses were independently repeated twice with similar results (Source data file 1); one representative fluorescence image is shown. Red brackets highlight proteins affected by PMO pretreatment, while red arrowheads indicate proteins band where labelling was specifically inhibited by PMO but not PM. Blue arrowheads mark proteins unaffected by pretreatment with the desthiobiotin-conjugated FP probe. Controls include DMSO-treated sample (lane 1) and heat-denatured homogenates (Δ, lane 2), confirming the FP probe’s specificity for active homogenates. Molecular weight markers (kDa) are shown on the left. Coomassie blue staining (bottom panel) confirms equal protein loading across all samples. b Volcano plot showing differential protein enrichment in FP-treated samples relative to boiled controls. Each protein is represented by a dot, with the x-axis showing the log₂ fold change (FC) and the y-axis displaying the adjusted p-value. Serine hydrolases (SHs) are highlighted in red. Proteins enriched (log₂ fold change > 1, p < 0.05, two-sided t-test) are shown in black, negatively enriched proteins in yellow. c Scatterplot comparing mean abundance of proteins in FP-treated versus heat-denatured (Heat_FP) controls, showing a strong enrichment of SHs in active (non-boiled) samples. d Donut plot summarizing the proportion of FP-enriched proteins identified as serine hydrolases (24.5%, 73/298). e Protein domain enrichment analysis (InterPro) of the top 20 enriched serine hydrolases grouped by conserved functional domains to identify enzyme families that are disproportionately represented. Carboxylesterases, phospholipases, and acetylcholinesterases were the most represented, enzyme classes known organophosphate targets. The right panel lists top SHs by gene ID and domain type, providing functional context. The right panel lists the corresponding top-ranking SHs by gene ID and domain type, providing a functional context for the identified targets.

Proteomic profiling reveals diverse serine hydrolase activity in An. gambiae

To profile active serine hydrolases (SHs) in An. gambiae, we performed affinity enrichment using a fluorophosphonate (FP) probe, followed by LC-MS/MS and label-free quantification (LFQ) using a data-dependent acquisition approach. Streptavidin-enriched proteomes were analyzed under three conditions: active labelling (FP), heat-inactivated control (Heat_FP), and competitive inhibition (PMO_FP). LFQ analysis identified 380 proteins across conditions (Supplementary Data S9). Quality control metrics confirmed high reproducibility and condition-specific profiles (Supplementary Fig. 2). Comparing active samples to heat-inactivated controls revealed 298 proteins significantly enriched by the FP probe (adjusted p ≤ 0.05, log2 fold change (FC) ≥ 1), confirming activity-dependent labelling (Fig. 2b, c). Manual annotation based on functional keywords (e.g., hydrolase activity (KW-0378), exopeptidase, endopeptidase)30, identified 73 of these enriched proteins as SHs, representing 24.5% of the FP-labelled proteome (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Data 9). Network analysis of 283 significantly enriched proteins highlighted a densely interconnected cluster associated with cellular amide metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Furthermore, InterPro analysis identified the Alpha/Beta hydrolase fold (IPR029058), common feature of insecticide-metabolizing enzymes, in 32 of the positively enriched proteins (Fig. 2e). Crucially, known OPs targets including AChE1/29,16, various CCEs17,20,21,22, lysophospholipases31,32,33,34, and fatty acid synthases31,32,33,34, were identified, demonstrating the utility of FP probe for functionally relevant SHs to PM within the An. gambiae proteome.

Competitive ABPP identifies pirimiphos-methyl targets including key carboxylesterases

Having established the active SH profile, we next specifically analysed the competitive inhibition arm of the experiment to identify direct molecular targets of PM insecticide. We performed competitive ABPP by comparing FP probe labelling in proteomes pre-incubated with the bioactive form of the insecticide, PMO, versus those without pre-incubation (active samples). This analysis identified 23 proteins, including 18 putative SHs, with significantly reduced FP labelling upon PMO treatment (log₂FC ≥ 1, adjusted p ≤ 0.05; Fig. 3a). These targets were generally less abundant than other probe-reactive proteins, ranging from low to moderate expression levels (Supplementary Fig. 4). Notably, the established toxicity targets AChE1 and AChE2 were strongly inhibited9. PMO also targeted eight CCEs; four of these-Coeae5g, Coebe2o, Coe09916, and Coeae6g-showed the most profound inhibition, approaching background levels (Fig. 3b). Network analysis illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3b, contextualized these interactions, revealing several inhibited enzymes, including AChE1/2 and the CCEs Coeae5g, Coeae6g, and Coebe2o, as central hubs with predicted links to diverse insecticides and metabolites. Among these, Coeae6g protein warranted further investigation, as its role in OPs resistance remained unclear, particularly given that field populations carrying Ace1 mutations and overexpressing Coeae6g gene remain susceptible to malathion29. We therefore prioritized Coeae6g orthologs from An. coluzzii and An. gambiae for functional validation to assess their contribution to PM resistance and potential cross-resistance to malathion, carbamate, and pyrethroid insecticides.

a The volcano plot illustrates changes in protein abundance between An. gambiae samples treated with fluorophosphonate (FP) and those exposed to PMO. Each protein is represented by a dot, with the x-axis showing the log₂ fold change (FC) and the y-axis displaying the adjusted p-value. Proteins with significantly reduced (Pos: positive enrichment) labelling upon PMO exposure (log₂ fold change > 1, p < 0.05, two-sided t-test) are highlighted in red, indicating potential direct targets of PMO toxicity. b Among the 23 proteins inhibited by PMO, 23 were mapped to VectorBase software (release 68), and 18 of these, classified as SHs, are displayed in the dot plots. The dot plots illustrate the log₂ intensity values for these 18 SHs across three conditions: FP treatment, PMO FP (PMO treatment following FP labelling), and Heat FP (heat-inactivated sample with FP labelling). Log₂ intensity reflects the abundance of probe-labelled (i.e., active) protein detected by mass spectrometry; a decrease in signal after PMO treatment indicates target engagement and inhibition. Each dot represents an individual replicate, with colours indicating the number of replicates (n = 3). Statistically significant differences between conditions are marked by asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, two-sided t-test). The SHs identified in the dot plots are shown in red, with esterases denoted by an asterisk (*). Other SHs are labelled with their respective protein names, manually retrieved from VectorBase, and displayed in each box. Proteins with longer names are abbreviated using their initials, such as Adcp-12 (abhydrolase domain-containing protein 12) and VCPLP (vitellogenic carboxypeptidase-like protein).

Coeae6g is localized in the cytoplasm

Computational tools (TargetP-2.0, Phobius, MitoFates, iPSORT), predicted a mitochondrial localization for Coeae6g protein. To investigate this, we performed crude subcellular fractionation from thoracic tissues of female An. gambiae mosquitoes. The tissue was selected as flight muscles, involved in energy intensive processes, are located there, thus total mitochondrial mass is expected to be higher, compared to other tissues35,36,37. Isolated fractions were analysed by Western blot using antibodies against Coeae6g enzyme (Supplementary methods), a mitochondrial marker (anti-ATP5A), and a cytosolic marker (anti-alpha-tubulin). Coeae6g signals were much stronger in the cytosolic fraction, contradicting computational predictions and indicating localization in a cytoplasmic compartment (Fig. 4). Control antibodies gave the expected pattern, albeit with low cross-contamination of mitochondria in the cytosolic fraction as picked up by the anti-ATP5A antibody. This cytoplasmic localization aligns with its role in insecticide detoxification, consistent with xenobiotic metabolism occurring mainly outside of mitochondria38,39,40.

ATP5A and alpha-tubulin are used as mitochondrial and cytosolic markers, respectively. Approximately 30 μg of total protein deriving from the same experiment were loaded from each fraction, in two separates, simultaneously processed, 10% SDS gels, and immuno-blotted against the three protein targets; a single nitrocellulose membrane was stained initially against Coeae6g and, after mild stripping using a low pH glycine solution and re-blocking, it was re-blotted against alpha-tubulin. Mitochondria isolation experiments and subsequent western blot analyses were independently repeated twice, yielding similar findings.

Inhibition kinetics of recombinant Coeae6g with different insecticides

The protein sequences of Coeae6g from An. gambiae and An. coluzzii are highly homologous (93.8% identity), carrying nine amino acid substitutions, of which two are non-conservative (Supplementary Fig. 5). These mutations do not lie in the conserved catalytic triad. We chose the An. coluzzii Coeae6g to express in Sf9 insect cells, using the baculovirus system. Successful expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6). Resuspended cell pellets expressing Coeae6g enzyme displayed 8-12-fold increased esterase activity towards the model substrates α-naphthyl acetate (α-NA), β- naphthyl acetate (β-NA) and p-nitrophenyl acetate (p-NPA), compared to YFP-expressing and uninfected Sf9 cells (Supplementary Table 1). The kinetic parameters for α- NA and β- NA were determined as: Km 68.49 μΜ (95% CI: 57.19–81.73) and Vmax 307.7 nmol min−1 mg total protein−1 (95% CI: 297.3–318.3); and Km 369.4 μΜ (95% CI: 306.0–446.5) and Vmax 253.0 nmol min−1 mg total protein−1 (95% CI: 238.2–269.3), respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

Activity inhibition assays towards α- NA, having shown higher affinity to Coeae6g than β-NA, were then performed to quantify the interaction of a number of insecticides (and their activated forms) with recombinant Coeae6g (Table 1). PMO displayed the strongest inhibition (IC50 of 0.03 μΜ (95% CI: 0.024–0.031)), followed by malaoxon (0.24 μΜ (95% CI: 0.23–0.25)). No inhibition was detectable by their pro-insecticide forms, PM and malathion. Two carbamate insecticides were shown to act as lower affinity inhibitors, bendiocarb had an IC50 value of 7.27 μΜ (95% CI: 6.43–8.19) and propoxur an IC50 of 3.52 μΜ (95% CI: 3.06–4.05). Lastly, permethrin exhibited a very low inhibitory effect (IC50 129.7 μΜ; 95% CI: 127.5–131.9), while no inhibition was observed by deltamethrin.

In vivo functional validation of the role of Coeae6g gene in insecticide resistance

Establishment of UAS-Coeae6g An. gambiae responder lines

The functional expression of Coeae6g gene in An. gambiae was performed in two independent labs using the GAL4 system. The coding sequence of the gene was amplified from two strains: an insecticide-susceptible An. gambiae (Kisumu) and an insecticide-susceptible An. coluzzii (NGousso). Responder lines carrying the An. gambiae (UAS-AngCoeae6g) or An. coluzzii (UAS-AncCoeae6g) Coeae6g coding regions under UAS control and marked with YFP (under the 3 × P3 promoter), were established by integrase-mediated transgene exchange into the genomic sites of docking lines Ubi-GAL441 and A11 (previously described in Lynd et al.)42, respectively, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 7.

Coeae6g is highly expressed in transgenic An. gambiae lines

The UAS-Coeae6g responder lines were crossed with Ubi-GAL4, a driver/docking line expressing GAL4 under the An. gambiae polyubiquitin promoter, that directs widespread tissue expression. Coeae6g transcription levels were assessed in the progeny and compared to the native expression levels in the respective docking lines by qPCR (Supplementary methods). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8a similar levels of overexpression were observed for the An. gambiae (71-fold) and An. coluzzii (81-fold) Coeae6g genes compared to controls (p < 0.01). An. coluzzii and An. gambiae Coeae6g protein abundance was additionally verified by Western blot analysis in whole transgenic female mosquito homogenates (Supplementary methods; Supplementary Fig. 8b, c), whereas total carboxylesterase activity was assayed in whole extracts from An. gambiae Coeae6g overexpressing mosquitoes and shown to be significantly higher against both standard esterase substrates, p-NPA (2.9-fold, p < 0.0001) and β-NA (2.3-fold, p < 0.0001) than control parental mosquitoes (Supplementary methods; Supplementary Table 2).

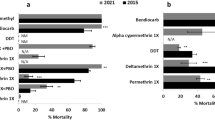

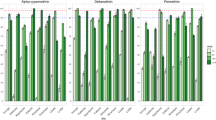

Coeae6g over-expressing An. gambiae are resistant to PM

Initially standard WHO tube diagnostic bioassays43 were used to assess the impact of Coeae6g over-expression on resistance against PM. PM resistance was observed in both transgenic lines (An. gambiae gene 67% mortality and An. coluzzii gene 79% mortality) (Fig. 5). To further quantify the level of PM resistance conferred by Coeae6g over-expression, we performed dose dependent or time dependent assays to calculate relative resistance ratios (RRs) for the An. gambiae and An. coluzzii gene over-expressing progeny, respectively (Table 2). Very similar RRs for PM exposure of 8.6 and 7.6 were observed for the two lines. Further work was performed with the AncCoeae6g line to investigate cross-resistance to other insecticides.

Insecticide sensitivity was assessed in WHO discriminating doses upon 1 h exposure, comparatively between a GAL4/UAS-An. gambiae (Ang)- Coeae6g and the control docking line Ubi-GAL4; and b GAL4/UAS-An. coluzzii (Anc)- Coeae6g and the control docking line A11. Individual values from n = 3 to 7 biological replicates (20–25 randomly picked females, from different batches) are shown and bars represent SEM n. Asterisk (*) denotes statistical significance between mortality rates of the two lines, estimated by Welch’s t-test (two-tailed), as: a p = 0.027; and b p = 0.046. Statistically non-significant differences are not indicated. The red dotted line corresponds to the 90% mortality WHO threshold indicating resistance. PM Pirimiphos methyl.

An. coluzzii Coeae6g over-expressing mosquitoes show cross-resistance to carbamates and the pyrethroid permethrin

One hour exposure caused 95–100% mortality for GAL4/UAS-AncCoeae6g and the control line for bendiocarb, propoxur, malathion and deltamethrin, while confirmed resistance was shown against permethrin (81.8% mortality) (Fig. 5b). Although Coeae6g overexpression did not confer resistance to the WHO discriminating dose and exposure time for the insecticides bendiocarb, propoxur and malathion, we tested the response of mosquitoes at shorter exposure times and observed clear differences between the GAL4/UAS-AncCoeae6g and the control line. To quantify the level of cross-resistance we performed time response assays and estimated the resistance ratios (RR50), which ranged between 2.2 and 4.6-fold (Table 3). For permethrin, where resistance was observed to the discriminating dose, a RR of 3 was observed. No resistance occurred against deltamethrin (exposure for 10 and 15 min resulted in 100% mortality for both strains, three replicates each).

Discussion

This study establishes a chemoproteomic framework for interrogating insecticide–protein interactions in insecticide-susceptible malaria vectors, advancing resistance biology beyond the retrospective scope of conventional genomic and transcriptomic approaches. While sequencing-based methods remain indispensable for cataloguing known resistance alleles, they often fail to capture dynamic and functionally relevant changes at the protein level, particularly those mediated by post-transcriptional regulation or enzyme activity modulation44,45,46. By directly probing the active proteome of a susceptible An. gambiae population with ABPP, we provide a forward-looking strategy to uncover mechanistic liabilities to new chemistries before resistance emerges in the field.

Our previous work demonstrated that ABPP using pyrethroid-mimetic probes could capture pyrethroid-metabolizing enzymes in rat liver microsomes and selectively label recombinant mosquito P450s47. In the present study, this approach was extended to intact mosquitoes, applying FP-based ABPP directly to An. gambiae to map active serine hydrolases within the native proteome. Using fluorophosphonate probes in an insecticide-susceptible strain, we systematically mapped catalytically active SH enzymes and identified enzymes with direct interactions with PM. This expands the application of ABPP beyond its established roles in pharmacology and toxicology30,31,48,49,50,51,52 into vector biology and resistance surveillance.

In-gel analyses of the insecticide-susceptible An. gambiae Kisumu strain confirmed selective and efficient labelling of active proteome, consistent with previous FP-based applications30,50,53, and validated the probe’s specificity in intact mosquitoes. Building on this validation, downstream pulldown proteomics resolved a baseline inventory of 73 catalytically active SHs, representing ~19% of the predicted repertoire. Because FP probes selectively label only catalytically active and accessible enzymes, shaped by tissue distribution, expression levels, and active-site conformation, this dataset provides a functional view of the enzyme landscape of which some are relevant to PM toxicity and resistance, such as AChEs and CCEs30,49. Competitive profiling with PMO narrowed SHs landscape to 18 proteins, including canonical OP insecticides targets such as AChE1/29,16, various CCEs17,20,21,22, lysophospholipases31,32,33,34, and fatty acid synthases31,32,33,34. Although lysophospholipases17,54,55,56 and fatty acid synthases are not classical detoxification enzymes like CCEs17,20,21,22, they have emerging roles in resistance: lysophospholipases share activity with neuropathy target esterases55,56, a known organophosphate target55,56,57, while fatty acid synthases modulate lipid metabolism31,32,33,34, membrane composition, and stress adaptation.

Among CCEs, Coeae6g enzyme emerged as a high-priority candidate, showing strong probe reactivity and PMO sensitivity. Although previously associated with pyrethroid and carbamate resistance, its role in PM resistance has remained unresolved, particularly as some field populations overexpressing Coeae6g remain susceptible to malathion despite carrying Ace1 mutations29. Here, we provide direct functional evidence of its contribution. In vitro assays with heterologously expressed An. coluzzii Coeae6g enzyme revealed strong binding affinity for the toxic oxon forms of PM (PMO) and malathion, but not their thio-phosphate precursors, suggesting a sequestration mechanism, providing a plausible biochemical basis for resistance. In vivo, transgenic overexpression of Coeae6g orthologs from both An. gambiae and An. coluzzii conferred PM resistance above WHO thresholds and reproduced cross-resistance phenotypes to permethrin and bendiocarb, consistent with observations from West African field populations29. These data offer mechanistic validation for recent genomic reports linking copy number variations (CNVs) spanning the Coeae2g–Coeae6g cluster to PM resistance58,59.

Although Coeae6g overexpression conferred only low-to-moderate resistance under our experimental conditions, its impact in the field could be amplified through synergy with other mechanisms, particularly target-site mutations (field populations overexpressing Coeae6g carry additional resistance mechanisms, like the G119S mutation on the Ace129. This remains a hypothesis that needs further testing, but it is supported by field observations, such as in Burkina Faso, where rising Coeae2g-Coeae6g cluster CNVs coincided with increased frequencies of Ace1 and vgsc target-site resistance mutations, a combination expected to drive significantly higher overall resistance levels to both OPs and pyrethroid, respectively60,61,62. Beyond Coeae6g, our profiling also identified additional CCEs; Coebe2o, Coeae5g, Coeae1f, and Coeae2f, as potential PMO targets. Several of these have been linked to resistance through transcriptomic or CNV studies, with Coeae1f and Coeae2f genes associated with both PM and pyrethroid resistance8. Their detection with FP-ABPP underscores that PM–pyrethroid cross-resistance may be more widespread than currently recognized, highlighting the need for systematic monitoring of SHs activities in vector populations.

Together, these findings establish ABPP as a functional framework with predictive power for identifying enzyme-mediated resistance liabilities before they emerge. The species-agnostic design of ABPP makes it adaptable across mosquito strains, tissues, and developmental stages, enabling mechanistic insights into resistance processes that transcend genomic or transcriptomic associations. Specifically, the identification of Coeae6g-mediated cross-resistance highlights the operational relevance of this framework and its potential to inform insecticide rotation and dual-chemistry net strategies in malaria vector control. Importantly, ABPP can also capture the functional consequences of single-nucleotide polymorphisms or altered protein expression that modify enzyme activity-features that may be missed by sequence-based surveillance. Thus, ABPP can complement existing WHO bioassays and genomic monitoring by providing direct functional evidence of enzyme vulnerabilities before resistance becomes widespread.

While this study establishes ABPP as a proof-of-concept platform for predictive resistance profiling, its demonstrated capacity remains limited to serine hydrolase activity in a laboratory-susceptible strain. Validation across genetically diverse and field-derived mosquito populations will be essential to determine whether FP-ABPP can robustly capture the dynamics of these resistance determinants under operational conditions. Beyond this initial demonstration, the framework provides a basis for comparative and longitudinal analyses to elucidate the broader contributions of serine hydrolases and other enzyme families to metabolic resistance-an area currently under active investigation. Looking ahead, ABPP can be extended to resistant populations, additional developmental stages, and specific tissues, leveraging subclass-specific probes to construct a comprehensive atlas of serine hydrolase activity and to explore other biological processes relevant to malaria transmission, including vector–parasite interactions48,63,64,65. Moreover, tailored probes targeting additional resistance-relevant enzyme classes such as P450s and GSTs have already been validated in other systems47,66,67,68, offering a realistic pathway to expand this approach across metabolic networks in mosquitoes.

In conclusion, this study establishes a predictive chemoproteomic framework for the early detection of insecticide resistance by functionally profiling active enzymes within the native mosquito proteome of a susceptible population. Using FP-based ABPP, the work identifies both established and previously unrecognized metabolic enzymes associated with resistance, including potential indicators of cross-resistance. By capturing functional protein activity, ABPP complements existing genomic approaches, bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype. Although focused on esterases, the platform is adaptable to other enzyme classes and vector species, providing a scalable tool for mechanism-based resistance monitoring across vector control programs and beyond.

Methods

In vitro labelling and gel-based analysis of PM targets in An. gambiae homogenates

Mosquito homogenate preparation and probe treatment

Twenty individuals of 3–5-day-old female An. gambiae (Kisumu strain) were homogenized in 500 µl of 1× DPBS (Invitrogen, UK) buffer and centrifuged at 21130 × g (Eppendorf 5425 R Centrifuge) for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay69 and normalized to 1 mg/ml using 1× DPBS. Aliquots (48 µl) of the normalized homogenate were then incubated with 1 µl of inhibitors pirimiphos-methyl (10 or 100 µM final concentration), pirimiphos-methyl oxon (10 or 100 µM final concentration), desthiobiotin-fluorophosphonate probe (FP) probe (2 or 10 µM final concentration), or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, control) for 1 h at 30 °C with shaking at 1200 rpm. Subsequently, 1 µl of T-FP probe (100 µM) was added to each sample to give 2 µM final concentration, except for the negative control, which received 1 µl of DMSO70. Heat-denatured homogenates treated with 2 µM final concentration of T-FP served as negative controls to confirm activity-dependent labelling of SHs. Incubation continued for an additional 1 h, then 50 µl of 1x-SDS page Gel loading buffer was added to each sample, mixed gently, and heated at 85 °C for 2–3 min, followed by a brief centrifugation.

Gel electrophoresis and analysis

Samples (20 µL) and 5 µL of protein marker were resolved on NuPAGE™ Bis-Tris Mini Gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 4–12% gradient) using NuPAGE MOPS SDS Running Buffer for medium-to-large proteins. Electrophoresis was performed at 200 V for 50 min. Gels were imaged using the iBright FL1500 Imaging System (ThermoFisher Scientific, UK) with a tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) filter, followed by destaining in acid-methanol for 1 h. Gels were then stained with colloidal stain, destained with water, and re-imaged.

Proteomic analysis of pirimiphos-methyl oxon targets in An. gambiae using FP-ABPP

FP Probe treatment

Homogenates from insecticide-susceptible female An. gambiae mosquitoes (Kisumu strain) were used to study protein interactions with the active organophosphate metabolite pirimiphos-methyl oxon (Sigma-Aldrich, UK). Each 500 µL homogenate sample (2 mg/mL protein) was pre-incubated with 10 µL of 5 mM pirimiphos-methyl oxon for 1 h at 30 °C with shaking. Subsequently, 10 µL of 100 µM ActivX™ Desthiobiotin-FP Serine Hydrolase Probe (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) was added, resulting in final concentrations of 100 µM PMO and 2 µM FP probe. Probe concentration was initially optimized for binding saturation, with 2 µM selected in line with ABPP published protocol70, and inhibitor dose–response confirmed near-saturating competition and robust target detection (Supplementary Fig. 1). The samples were incubated for an additional hour at 30 °C with shaking. Control samples, including both active and heat-denatured homogenates treated with the FP probe, served as positive and negative controls, respectively. All treatments, including the PMO-treated groups and controls, were performed in triplicate to ensure reliability and reproducibility. After incubation, samples were chilled on dry ice and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Removal of excess reagents and protein precipitation

Frozen samples were thawed on ice, then centrifuged to pellet the proteins at 21130 × g (Eppendorf 5425R Centrifuge, UK) for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and pellets were washed thrice with cold methanol, using sonication for resuspension between centrifugations. Next, 0.65 mL of 2.5% SDS in Ca- and Mg-free D-PBS was added to each pellet, followed by sonication and heating steps to solubilize proteins. Samples were centrifuged again, and the supernatant discarded. Additional heating and sonication were applied when precipitate still visible to ensure complete protein solubilization. Finally, the samples were adjusted to 3.5 mL with D-PBS (reaching 0.5% SDS) and frozen overnight.

Streptavidin enrichment of FP-labelled proteins

The SDS-solubilized proteins were diluted with calcium- and magnesium-free Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (D-PBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK) to achieve a final SDS concentration of 0.2%. Pre-washed streptavidin beads (Invitrogen, UK) were added to the samples, which were rotated to enrich for FP-labelled proteins. After centrifugation, most of the supernatant was removed, and the remaining beads were transferred to a new tube. The beads were sequentially washed with 1% SDS (Sigma-Aldrich), 6 M urea (Sigma-Aldrich), and Ca- and Mg-free D-PBS, with centrifugation and supernatant removal between each wash.

On-bead reduction, alkylation, and digestion

The washed beads were resuspended in 500 µL of 6 M urea in Ca- and Mg-free D-PBS. Next, 25 µL of 200 mM dithiothreitol (DTT, Sigma-Aldrich, UK) was added to achieve a final concentration of 10 mM, and the samples were heated at 65 °C for 15 min. Following reduction, 25 µL of 500 mM iodoacetamide (IAA, Sigma-Aldrich, UK) was added, reaching a final concentration of 25 mM, and the samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. The beads were centrifuged at 1400 × g for 2 min, and the supernatant was removed. The beads were washed once with 1 mL of Ca- and Mg-free D-PBS. For trypsin digestion, the beads were resuspended in 200 µL of 2 M urea in Ca- and Mg-free D-PBS, 2 µL of 100 mM calcium chloride (CaCl₂, Sigma-Aldrich, UK) to achieve a final concentration of 1 mM, and 4 µL of 0.5 mg/mL trypsin (2 µg total; Promega, UK). The samples were incubated overnight at 37 °C with gentle agitation.

Elution of tryptic peptides

After digestion, the samples were centrifuged at 1400 × g for 2 min, and the supernatant containing the tryptic peptides was transferred to a clean microcentrifuge tube (Fisherbrand™ Premium Microcentrifuge Tubes, Thermo Fisher Scientific). To recover any remaining peptides, 100 µL of Ca- and Mg-free D-PBS was added to the beads, and the resulting solution was combined with the initial supernatant for a final volume of 300 µL. The peptide solution was acidified with 17 µL of 90% formic acid (Fisher Chemical, UK) to reach a final concentration of 5%. The samples were either prepared for immediate mass spectrometry (MS) analysis or stored at −80 °C for future use.

LC-MS/MS analysis for protein identification and quantification

Tryptic peptides generated from on-bead digestion were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) at the FingerPrints Proteomics Facility, College of Life Sciences, University of Dundee. Peptides were resuspended in 1% formic acid (FA, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and purified using Empore Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges, C18 (#41155D, 3 M). Samples were dried using a SpeedVac (Thermo Scientific) and resuspended in 50 µl of 1% formic acid. The resuspended peptides were centrifuged, and the supernatant was transferred to HPLC vials, with 8 µl of the sample analyzed directly on a chromatography-mass spectrometry system. Peptides were separated and analyzed using an Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano system (Thermo Scientific) coupled to an Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Samples were injected and washed on an Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 trap column (100 µm × 2 cm, Thermo Scientific) with 2% Buffer B for 5 min before applying a gradient using Buffer A (0.1% formic acid) and Buffer B (80% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid). The separation was performed on an Easy-Spray PepMap RSLC C18 analytical column (75 µm × 50 cm, Thermo Scientific) under gradient conditions starting with 2% Buffer B, held for 5 min, followed by a linear increase to 35% Buffer B over 125 min, reaching 98% Buffer B after a further 2 min, and maintained for 10 min, before re-equilibration to 35% Buffer B after 1 min. The flow rate was maintained at 0.3 µl/min throughout the run, and the sample was transferred to the mass spectrometer via an Easy-Spray source set to 50 °C with a source voltage of 3.0 kV and capillary temperature of 250 °C. A scan cycle comprised a MS1 scan (m/z range 335–1800, ion injection time of 25 ms, resolution 60,000 and automatic gain control of 3.0 × 106 acquired in profile mode, followed by 20 sequential dependent MS2 scans (resolution, 15,000) of the most intense ions fulfilling predefined selection criteria (AGC 5 × 103, maximum ion injection time 40 ms, isolation window of 1.4 m/z). The HCD collision energy was set to 27%. Mass accuracy was checked before the samples were run.

Data processing and analysis

The LC-MS/MS RAW data were processed with MaxQuant version 2.1.1.0. and peptides were identified from the MS/MS spectra searched against the Anopheles gambiae reference proteome (UniProtKB, proteome ID UP000007062, downloaded from https://www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000007062 on 23 February 2022). Cysteine carbamidomethylating was used as a fixed modification, and methionine oxidation, asparagine/glutamine deamidation, methionine/tryptophan dioxidation, glutamine to pyro-Glu and N-term acetylation. The false discovery rate was set to 0.01 at the protein level & peptide-spectrum match (PSM) level. The match between runs option was enabled, and protein grouping was achieved by selecting a unique and razor peptides mode that calculates ratios from unique and razor peptides (razor peptides were uniquely assigned to protein groups). Other parameters were used as pre-set in the software. The built-in label-free quantification algorithm (MaxLFQ) was used to perform the LFQ experiments in MaxQuant software71. MaxLFQ allows comparative analysis of high-resolution MS data generated from two biological samples by comparing peptide peak intensities. For statistical analysis and bioinformatics, Protein Groups file processed using LFQ-Analyst, an interactive web-platform designed for analyzing and visualizing proteomics data pre-processed with MaxQuant72. LFQ data were log₂-transformed, and missing values imputed using the “Missing Not At Random” (MNAR) method, drawing from a left-shifted Gaussian distribution (mean shift: 1.8 standard deviations; width: 0.3). Significantly differentiated proteins were identified based on an adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg correction) and an absolute log₂ fold change ≥ 1. Pearson correlation coefficients compared protein labelling intensities across replicates and treatment conditions, visualized in a correlation matrix. Hierarchical clustering was performed on Z-score normalized; log₂-transformed LFQ intensities.

Processed data, including the complete dataset and quantitative proteomic results, are provided in the Supplementary Data Files (S1–S6) as detailed in the Data Availability section.

Crude sub-cellular fractionation from mosquito thoraxes

Mitochondria were isolated from the other cell compartments, i.e., nuclei and cytoplasm, as described in Njiru et al. 202273, using approximately 40 mg thoraxes (~ 80 thoraxes, after removal of the wings and the legs) of 3–5 days old female mosquitoes of the docking line A11, homogenized in 1 ml of freshly-prepared, iced-cold Phosphate- free sucrose MOPS buffer pH 8.0, containing 440 mM sucrose, 20 mM MOPS, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM PMSF and 1 mM protease inhibitors (SIGMAFAST tablets, Sigma), using Dounce homogenizer. The suspension was centrifuged twice at 1000 × g for 10 min, at 4 °C, to separate carcass and nuclei (pellet) from mitochondria and cytosol (supernatant). Afterwards, the supernatant was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min, at 4 °C, to sediment mitochondria and leave cytoplasm in the supernatant. A small amount of each fraction was kept and stored at −80 °C, for subsequent Western blot analysis. Approximately 30 μg of total protein were loaded from each fraction, in two separate 10% SDS acrylamide gels, and immuno-blotted against three protein targets: Coeae6g (rabbit anti-Coeae6g, Davids Biotechnologie, dilution 1/1.000 in 2% milk/1× TBST; Supplementary Methods), alpha-tubulin (serving as cytosolic marker; mouse anti-alpha-tubulin, DSHB #12G10, dilution 1/2.000 in 2% milk/1× TBST) and ATP5A (serving as mitochondrial marker; mouse anti-ATP5A, Abcam 15H4C4, dilution 1/1.000 in 2% milk/1× TBST). Antibody binding was detected using goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling; #7074) and goat anti-mouse IgG (Merck; #12-349), both horse-radish peroxidase (HRP)-linked, at dilutions 1/5.000 in 2% milk/1× TBST, and ECL substrates (Thermo Scientific; SuperSignal West Pico Plus).

Baculovirus-mediated expression of recombinant Coeae6g in Sf9 cells

The An. coluzzii Coeae6g coding region was cloned into the pFastBac/ CT-TOPO vector (Bac-to-Bac TOPO Cloning Kit; Gibco), using primers Coeae6g Forw and Rev (Supplementary Data S7). DH10Bac competent E. coli cells were transformed to generate bacmid DNA, using the Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus Expression System (Gibco). Colonies with recombinant bacmids were selected on kanamycin/tetracycline/gentamycin plates by blue-white selection, and the presence of the Coeae6g coding sequence was verified with PCR (pUC/M13 Forward -M13 Reverse primer pair) and via Sanger sequencing (GENEWIZ, Azenta Life Sciences, Germany), using primers pUC/M13 Forward and M13 Reverse, and Coeae6g Fin and Rin (Supplementary Data S7). Recombinant baculovirus expressing YFP was also generated and used as a negative control in all experiments henceforth.

To obtain esterase expression, fresh Sf9 cells (Gibco, Cat. Number 11496015) at 106 cells/mL were infected for 72 h\ with baculovirus stock at a multiplicity of infection of 5 (virus stocks were titrated using the baculoQUANT ALL-IN-ONE Kit, Oxford Expression Technologies Ltd) in SF-900 II SFM (Gibco) medium, supplemented with 10% FBS and 10% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco). Uninfected Sf9 cells were included as control. Harvested and washed with 1× ice-cold Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)- cell pellets were resuspended in 0.02 M Sodium Phosphate Buffer pH 7.2, disrupted by mild sonication, and then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min, at 4 °C, to remove cell debris. Supernatants were subjected to Western blot analysis, to verify successful Coeae6g expression (Supplementary methods; Supplementary Fig. 6), prior biochemical assays.

Biochemical assays and inhibition kinetics in Sf9 cells expressing Coeae6g

Recombinant An. coluzzii Coeae6g esterase activity was assessed against the model substrates, α-naphthyl acetate (α-ΝΑ), β-naphthyl acetate (β-NA) (both diluted in methanol) and p-nitrophenyl acetate (p-NPA) (diluted in acetonitrile) using a SpectraMax-M2 multimode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Berkshire, UK). The reaction mixture for α-ΝΑ and β-NA consisted of 10 μl of cell homogenate, containing approximately 10 μg of protein, and 200 μl of 300 μΜ substrate in 0.02 M SPB pH 7.2. Reactions were incubated for 20 min, at room temperature upon which 50 μl of 3 mg/ ml Fast Blue dye were added per well. Formation of the naphthol—Fast Blue RR dye complex was measured endpoint at 570 nm. Standard curves of α-naphthol and β-naphthol were used to convert initial slopes into specific activities. For p-NPA, the substrate was diluted in 50 mM SPB and the rate of p-nitrophenol formation (kinetics) was monitored at 405 nm, at 20 s intervals during a 2 min period. P- nitrophenol concentration was determined based on the absorbance and using a molecular extinction coefficient of 18,000 M−1 cm−1,74. Control reactions using protein homogenates from Sf9 expressing YFP, as well as uninfected Sf9, were included for all substrates.

Recombinant Coeae6g kinetics against α-ΝΑ were determined by using a range of final substrate’s concentrations (1 μM to 1 mM). Km and Vmax values were defined using non-linear regression in GraphPad Prism 8.0.2. Eight different insecticide compounds were tested for their potential to inhibit recombinant Coeae6g activity against α-ΝΑ, including pirimiphos-methyl (Dr. Ehrenstorfer), malathion (PESTANAL Sigma-Aldrich) and their toxic oxon analogs, pirimiphos-methyl oxon (ChemService) and malaoxon (PESTANAL Sigma-Aldrich), respectively, bendiocarb (PESTANAL Sigma-Aldrich), propoxur (ChemService), permethrin (PESTANAL Sigma-Aldrich), and deltamethrin (PESTANAL Sigma-Aldrich). Insecticide stock solutions were prepared in 5% acetonitrile. 10 μg of Sf9 expressing Coeae6g homogenates were incubated with 10 μl of each compound concentration for 10 min, prior the 20 min incubation with α-ΝΑ, at a concentration equal to the Km value. Half-maximal inhibitory concentration values (IC50), corresponding to the concentration of each insecticide required to inhibit Coeae6g activity against α-ΝΑ by 50%, were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2.

Mosquito rearing

All mosquitoes were maintained under standard insectary conditions, at temperature 26 °C ± 2 °C and relative humidity 70% ± 10%, under L12:D12 hour photoperiod. All larval stages were fed on ground fish food (Tetramin tropical flakes, Tetra, Blacksburg, VA, USA), and adults were provided with 10% sucrose solution. Details of mosquito strains, including colony origin, generation history, and rearing conditions, are provided in Supplementary Data S8.

Construction of UAS-Coeae6g responder plasmids and creation of UAS-Coeae6g An. gambiae transgenic lines by ΦC31- mediated cassette exchange

The Coeae6g coding regions were amplified from cDNA of the An. gambiae Kisumu and An. coluzzii NGousso laboratory colonies using Phusion HF DNA polymerase (NEB) with primer pairs, Ang006727forRI: Ang006727revNheI and Coeae6gForwNheI: Coeae6gRevXhoI (Supplementary Data S7), respectively. These fragments were then either subcloned and sequence verified (AngCoeae6g) in pJET before cloning into a YFP-marked UAS plasmid (pSL* attB:3 × P3-eYFP:gyp-UAS14i-gyp:attB, previously described in Lynd et al.42), or directly cloned (AncCoeae6g) into the same UAS plasmid and then sequenced using primers Coeae6g NheI For, Coeae6g Fin, Coeae6g XhoI Rev, and Coeae6g Rin (Supplementary Data S7), as well as the universal primers Hsp70 and SV40 polyA.

Embryos of the Ubi-GAL4 (for AncCoeae6g) or A11 (for AngCoeae6g) docking line (previously described in Adolfi et al. and Lynd et al., respectively)42,75, bearing attP sites and marked with 3 × P3-eCFP (Supplementary Fig. 7), were microinjected with a mix of 350 ng/μl of responder UAS- Coeae6g plasmid and 150 ng/μl of an integrase helper plasmid (pKC40) encoding the phiC31 integrase76 following standard procedures (Poulton et al.)77. Emerging F0 larvae, with transient YFP expression, were selected using fluorescent stereomicroscopy and outcrossed with wild type G3 individuals of the opposite sex. The G1 larvae expressing only eYFP and no eCFP, in their nerve cord and eyes (denoting successful cassette exchange), were identified by fluorescence microscopy using YFP and CFP filters (Leica) and inter-crossed. The colony was maintained as a mixed stock of homozygotes (UAS- Coeae6g / UAS- Coeae6g) and heterozygotes (UAS- Coeae6g/+) but enriched with fluorescent progeny in each generation.

Driver × Responder line crosses

To promote the expression of Coeae6g, individuals of both Ang and Anc UAS-Coeae6g responder lines (marked eYFP) were crossed with opposite sex individuals from Ubi-GAL4 driver line (generated in Adolfi et al., 201841, that carries the GAL4 factor under the control of the An. gambiae polyubiquitin promoter and is marked with eCFP) (Supplementary Fig. 7). Transheterozygous Ubi-GAL4/UAS- Coeae6g progeny were selected by screening pupae positive for both eYFP and eCFP.

Insecticide resistance profile of the GAL4/UAS progeny

Susceptibility to insecticides in the progeny of the cross Ubi-GAL4 × UAS- Coeae6g, as well as the parental docking lines, were assessed using WHO tube bioassays and insecticide discriminating doses43. These doses are fixed at twice the lethal concentration that kills 99% of the susceptible mosquitoes 24 h after 1 h of exposure, and mortality of less than 90% is the threshold to define diagnostic resistance (98–100% mortality shows susceptibility, while 90–97% indicates the possibility of upcoming resistance)43. A minimum of three replicates of 20–25 female mosquitoes, 3–5 days old, were conducted for each insecticide. Statistical significance between the mortality percentages of the GAL4/UAS and the parental lines was assessed using Welch’s t-test. The LD50 (lethal dose 50; exposure dose resulting in 50% mortality) was performed as described by Lees et al. 2020 in at least two replicates for a range of PM dilutions in acetone covering 0.0001%–0.01%. The LT50 (lethal time 50; exposure time resulting in 50% mortality) was determined using WHO insecticide-impregnated papers and varying the exposure time. Test values were calculated using Polo Plus 2.0.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data generated in this study have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository under the dataset identifier PXD060698. The Anopheles gambiae reference proteome used for MaxQuant searches is available in UniProtKB under proteome ID UP000007062 (downloaded on 23 February 2022). Processed data, including the complete dataset and quantitative results, are available in the Supplementary Files and Supplementary Datasets provided with this paper. These include: Source data for graphs, quantitative analyses, and uncropped blots are provided in the Source Data file 1. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The computational workflows used for proteomic data processing and quantitative analysis were implemented using the open-source software MaxQuant (version 2.1.1.0) [https://maxquant.org] and LFQ-Analyst [https://bioinformatics.erc.monash.edu/apps/LFQ-Analyst/]. All parameters and settings applied in these analyses are described in the “Methods” section. Supplementary File S6 contains the RData output generated from LFQ-Analyst, including the protein groups and experimental design used for downstream statistical analysis and visualization. No custom code was developed for this study.

References

World malaria report 2024: addressing inequity in the global malaria response. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (World Health Organization (WHO), 2024).

Hancock, P. A., Ochomo, E. & Messenger, L. A. Genetic surveillance of insecticide resistance in African Anopheles populations to inform malaria vector control. Trends Parasitol. 40, 604–618 (2024).

Sherrard-Smith, E. et al. Systematic review of indoor residual spray efficacy and effectiveness against Plasmodium falciparum in Africa. Nat. Commun. 9, 4982 (2018).

Agossa, F. R. et al. Efficacy of various insecticides recommended for indoor residual spraying: pirimiphos methyl, potential alternative to bendiocarb for pyrethroid resistance management in Benin, West Africa. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 108, 84–91 (2014).

Oxborough, R. M. Trends in US President’s Malaria Initiative-funded indoor residual spray coverage and insecticide choice in sub-Saharan Africa (2008-2015): urgent need for affordable, long-lasting insecticides. Malar. J. 15, 146 (2016).

Dengela, D. et al. Multi-country assessment of residual bio-efficacy of insecticides used for indoor residual spraying in malaria control on different surface types: results from program monitoring in 17 PMI/USAID-supported IRS countries. Parasit. Vectors 11, 71 (2018).

Anopheles gambiae Genomes, C. et al. Genetic diversity of the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Nature 552, 96–100 (2017).

Nagi, S. C. et al. Parallel evolution in mosquito vectors-A duplicated esterase locus is associated with resistance to pirimiphos-methyl in Anopheles gambiae. Mol. Biol. Evol. 41 https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msae140 (2024).

Kim, Y. H. & Lee, S. H. Which acetylcholinesterase functions as the main catalytic enzyme in the Class Insecta?. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 47–53 (2013).

Feyereisen, R. Insect P450 inhibitors and insecticides: challenges and opportunities. Pest Manag. Sci. 71, 793–800 (2015).

Del Carlo, M. et al. Determining pirimiphos-methyl in durum wheat samples using an acetylcholinesterase inhibition assay. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 381, 1367–1372 (2005).

Djogbenou, L. et al. Evidence of introgression of the ace-1(R) mutation and of the ace-1 duplication in West African Anopheles gambiae s. s. PLoS ONE 3, e2172 (2008).

Assogba, B. S. et al. An ace-1 gene duplication resorbs the fitness cost associated with resistance in Anopheles gambiae, the main malaria mosquito. Sci. Rep. 5, 14529 (2015).

Assogba, B. S. et al. The ace-1 locus is amplified in all resistant anopheles gambiae mosquitoes: fitness consequences of homogeneous and heterogeneous duplications. PLoS Biol. 14, e2000618 (2016).

Grau-Bove, X. et al. Resistance to pirimiphos-methyl in West African Anopheles is spreading via duplication and introgression of the Ace1 locus. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009253 (2021).

Cheung, J., Mahmood, A., Kalathur, R., Liu, L. & Carlier, P. R. Structure of the G119S mutant acetylcholinesterase of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae reveals basis of insecticide resistance. Structure 26, 130–136 e132 (2018).

Ranson, H. et al. Evolution of supergene families associated with insecticide resistance. Science 298, 179–181 (2002).

Adedeji, E. O. et al. Anopheles metabolic proteins in malaria transmission, prevention and control: a review. Parasit. Vectors 13, 465 (2020).

Prasad, K. M., Raghavendra, K., Verma, V., Velamuri, P. S. & Pande, V. Esterases are responsible for malathion resistance in Anopheles stephensi: a proof using biochemical and insecticide inhibition studies. J. Vector Borne Dis. 54, 226–232 (2017).

Ross, M. K., Streit, T. M. & Herring, K. L. Carboxylesterases: dual roles in lipid and pesticide metabolism. J. Pestic. Sci. 35, 257–264 (2010).

Cruse, C., Moural, T. W. & Zhu, F. Dynamic roles of insect carboxyl/cholinesterases in chemical adaptation. Insects 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14020194 (2023).

Hopkins, D. H. et al. Structure of an insecticide sequestering carboxylesterase from the disease vector Culex quinquefasciatus: what makes an enzyme a good insecticide sponge?. Biochemistry 56, 5512–5525 (2017).

David, J. P. et al. The Anopheles gambiae detoxification chip: a highly specific microarray to study metabolic-based insecticide resistance in malaria vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4080–4084 (2005).

Wu, X. M. et al. Identification of carboxylesterase genes associated with pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles sinensis (Diptera: Culicidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 74, 159–169 (2018).

Zoh, M. G. et al. Deltamethrin and transfluthrin select for distinct transcriptomic responses in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Malar. J. 22, 256 (2023).

Cattel, J. et al. A genomic amplification affecting a carboxylesterase gene cluster confers organophosphate resistance in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: from genomic characterization to high-throughput field detection. Evol. Appl. 14, 1009–1022 (2021).

Grigoraki, L. et al. Functional and immunohistochemical characterization of CCEae3a, a carboxylesterase associated with temephos resistance in the major arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 74, 61–67 (2016).

Poulton, B. C., Colman, F., Anthousi, A., Sattelle, D. B. & Lycett, G. J. Aedes aegypti CCEae3A carboxylase expression confers carbamate, organophosphate and limited pyrethroid resistance in a model transgenic mosquito. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 18, e0011595 (2024).

Wipf, N. C. et al. Multi-insecticide resistant malaria vectors in the field remain susceptible to malathion, despite the presence of Ace1 point mutations. PLoS Genet. 18, e1009963 (2022).

Kumar, K., Mhetre, A., Ratnaparkhi, G. S. & Kamat, S. S. A superfamily-wide activity atlas of serine hydrolases in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochemistry 60, 1312–1324 (2021).

Ahn, K., Johnson, D. S. & Cravatt, B. F. Fatty acid amide hydrolase as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of pain and CNS disorders. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 4, 763–784 (2009).

Tan, Q. Q., Liu, W., Zhu, F., Lei, C. L. & Wang, X. P. Fatty acid synthase 2 contributes to diapause preparation in a beetle by regulating lipid accumulation and stress tolerance genes expression. Sci. Rep. 7, 40509 (2017).

Moriconi, D. E., Dulbecco, A. B., Juarez, M. P. & Calderon-Fernandez, G. M. A fatty acid synthase gene (FASN3) from the integument tissue of Rhodnius prolixus contributes to cuticle water loss regulation. Insect Mol. Biol. 28, 850–861 (2019).

Xin, T. et al. Fatty acid synthase regulates lipid metabolism in Panonychus citri (McGregor) (Acari: Tetranychidae) and its potential for mite control. Pest Manag.Sci. 81, 4382–4392 (2025).

Bretscher, H. & O’Connor, M. B. The role of muscle in insect energy homeostasis. Front. Physiol. 11, 580687 (2020).

Sogl, B., Gellissen, G. & Wiesner, R. J. Biogenesis of giant mitochondria during insect flight muscle development in the locust, Locusta migratoria (L.). Transcription, translation and copy number of mitochondrial DNA. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 11–17 (2000).

Watanabe, M. I. & Williams, C. M. Mitochondria in the flight muscles of insects. I. Chemical composition and enzymatic content. J. Gen. Physiol. 34, 675–689 (1951).

Ketterman, A. J., Jayawardena, K. G. & Hemingway, J. Purification and characterization of a carboxylesterase involved in insecticide resistance from the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus. Biochem. J. 287, 355–360 (1992).

Yang, X. Q. Gene expression analysis and enzyme assay reveal a potential role of the carboxylesterase gene CpCE-1 from Cydia pomonella in detoxification of insecticides. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 129, 56–62 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. A Drosophila systems approach to xenobiotic metabolism. Physiol. Genomics 30, 223–231 (2007).

Adolfi, A. et al. Functional genetic validation of key genes conferring insecticide resistance in the major African malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25764–25772 (2019).

Lynd, A. et al. Development of a functional genetic tool for Anopheles gambiae oenocyte characterisation: application to cuticular hydrocarbon synthesis. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/742619v2 (2019).

WHO. Manual for monitoring insecticide resistance in mosquito vectors and selecting appropriate interventions. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/356964. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (2022).

Muthu Lakshmi Bavithra, C., Murugan, M., Pavithran, S. & Naveena, K. Enthralling genetic regulatory mechanisms meddling insecticide resistance development in insects: role of transcriptional and post-transcriptional events. Front. Mol. Biosci. 10, 1257859 (2023).

Boolchandani, M., D’Souza, A. W. & Dantas, G. Sequencing-based methods and resources to study antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 356–370 (2019).

Feder, M. E. & Walser, J. C. The biological limitations of transcriptomics in elucidating stress and stress responses. J. Evol. Biol. 18, 901–910 (2005).

Ismail, H. M. et al. Pyrethroid activity-based probes for profiling cytochrome P450 activities associated with insecticide interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 19766–19771 (2013).

Porta, E. O. J., Isern, J. A., Kalesh, K. & Steel, P. G. Discovery of leishmania druggable serine proteases by activity-based protein profiling. Front. Pharm. 13, 929493 (2022).

Nomura, D. K. & Casida, J. E. Activity-based protein profiling of organophosphorus and thiocarbamate pesticides reveals multiple serine hydrolase targets in mouse brain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 2808–2815 (2011).

Correy, G. J. et al. Overcoming insecticide resistance through computational inhibitor design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 21012–21021 (2019).

Jutras, P. V. et al. Activity-based proteomics reveals nine target proteases for the recombinant protein-stabilizing inhibitor SlCYS8 in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 1670–1678 (2019).

Ruby, M. A. et al. Human carboxylesterase 2 reverses obesity-induced diacylglycerol accumulation and glucose intolerance. Cell Rep. 18, 636–646 (2017).

Bachovchin, D. A. et al. Superfamily-wide portrait of serine hydrolase inhibition achieved by library-versus-library screening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 20941–20946 (2010).

Flieger, A., Neumeister, B. & Cianciotto, N. P. Characterization of the gene encoding the major secreted lysophospholipase A of Legionella pneumophila and its role in detoxification of lysophosphatidylcholine. Infect. Immun. 70, 6094–6106 (2002).

Quistad, G. B., Barlow, C., Winrow, C. J., Sparks, S. E. & Casida, J. E. Evidence that mouse brain neuropathy target esterase is a lysophospholipase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 7983–7987 (2003).

Greiner, A. J., Richardson, R. J., Worden, R. M. & Ofoli, R. Y. Influence of lysophospholipid hydrolysis by the catalytic domain of neuropathy target esterase on the fluidity of bilayer lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1798, 1533–1539 (2010).

Hou, W. Y. et al. The alteration of the expression level of neuropathy target esterase in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells disrupts cellular phospholipids homeostasis. Toxicol. Vitr. 86, 105509 (2023).

Kientega, M. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of major malaria vectors reveals the evolution of new insecticide resistance variants in a longitudinal study in Burkina Faso. Malar. J. 23, 280 (2024).

Lucas, E. R. et al. Copy number variants underlie major selective sweeps in insecticide resistance genes in Anopheles arabiensis. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002898 (2024).

Edi, C. V. et al. CYP6 P450 enzymes and ACE-1 duplication produce extreme and multiple insecticide resistance in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004236 (2014).

Samantsidis, G. R. et al. What I cannot create, I do not understand’: functionally validated synergism of metabolic and target site insecticide resistance. Proc. Biol. Sci. 287, 20200838 (2020).

Grigoraki, L. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 modified An. gambiae carrying kdr mutation L1014F functionally validate its contribution in insecticide resistance and combined effect with metabolic enzymes. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009556 (2021).

Faucher, F., Bennett, J. M., Bogyo, M. & Lovell, S. Strategies for tuning the selectivity of chemical probes that target serine hydrolases. Cell Chem. Biol. 27, 937–952 (2020).

Davison, D., Howell, S., Snijders, A. P. & Deu, E. Activity-based protein profiling of human and Plasmodium serine hydrolases and interrogation of potential antimalarial targets. iScience 25, 104996 (2022).

Wang, C., Abegg, D., Dwyer, B. G. & Adibekian, A. Discovery and evaluation of new activity-based probes for serine hydrolases. Chembiochem 20, 2212–2216 (2019).

Wright, A. T. & Cravatt, B. F. Chemical proteomic probes for profiling cytochrome p450 activities and drug interactions in vivo. Chem. Biol. 14, 1043–1051 (2007).

Wright, A. T., Song, J. D. & Cravatt, B. F. A suite of activity-based probes for human cytochrome P450 enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 10692–10700 (2009).

Stoddard, E. G. et al. Activity-based probes for isoenzyme- and site-specific functional characterization of glutathione S-transferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16032–16035 (2017).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Liu, Y., Patricelli, M. P. & Cravatt, B. F. Activity-based protein profiling: the serine hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14694–14699 (1999).

Cox, J. & Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol 26, 1367–1372 (2008).

Shah, A. D. Goode, R. J. A., Huang, C., Powell, D. R. & Schittenhelm, R. B. LFQ-Analyst: An Easy-To-Use Interactive Web Platform To Analyze and Visualize Label-Free Proteomics Data Preprocessed with MaxQuant. J. Proteome. Res. 19, 204–211 (2020).

Njiru, C. et al. A H258Y mutation in subunit B of the succinate dehydrogenase complex of the spider mite Tetranychus urticae confers resistance to cyenopyrafen and pyflubumide, but likely reinforces cyflumetofen binding and toxicity. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 144, 103761 (2022).

Zhou, B. & Zhang, Z. Y. Mechanism of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-3 activation by ERK2. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35526–35534 (1999).

Adolfi, A., Pondeville, E., Lynd, A., Bourgouin, C. & Lycett, G. J. Multi-tissue GAL4-mediated gene expression in all Anopheles gambiae life stages using an endogenous polyubiquitin promoter. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 96, 1–9 (2018).

Ringrose, L. Transgenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Methods Mol. Biol. 561, 3–19 (2009).

Poulton, B. C. et al. Using the GAL4-UAS system for functional genetics in Anopheles gambiae. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/62131 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Medical Research Council (MRC) under grant number MR/V001264/1, awarded to M.J.I.P., D.W., G.L and H.M.I. This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Gates Foundation grant INV-062098 (H.M.I.). The conclusions and opinions expressed in this work are those of the author(s) alone and shall not be attributed to the Foundation. Additional support was provided by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (H.F.R.I.) through the following grants: “Basic Research Financing (Horizontal Support for All Sciences)” under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (Greece 2.0, Project Number: 016044); the “3rd Call for H.F.R.I. Research Projects to Support Post-Doctoral Researchers” (Project Number: 7406); and the “3rd Call for H.F.R.I. PhD Fellowships” awarded to S.B. (Fellowship Number: 11078). Gates Foundation grant INV-062098 (H.M.I.). We thank Dr. Yang Wu for assistance with western blotting of the An. gambiae samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M.I., M.J.I.P., D.W., G.L., and J.V. conceptualized the study; S.B., L.G., F.O., and F.C. performed research; H.M.I., G.L., D.W., and M.J.I.P. secured funding; H.M.I. analyzed the chemical proteomic data, while S.B., L.G., and G.L. analyzed functional validation data; and H.M.I. S.B. and L.G. wrote the original draft of the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kailash (C) Pandey and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balaska, S., Grigoraki, L., Lycett, G. et al. Predictive chemoproteomics and functional validation reveal Coeae6g-mediated insecticide cross-resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Nat Commun 16, 10772 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65827-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65827-4