Abstract

Liquid biopsies enable non-invasive monitoring and characterization of metastatic cancer, primarily through circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in blood. The representativeness of all metastatic sites in these liquid biopsies and the clinical relevance of other body fluids remain uncertain. We performed low-pass whole genome sequencing on 216 liquid and 745 metastatic tissue samples from 20 autopsied female patients with metastatic breast cancer to assess ctDNA detection, fraction, and site representativeness in seven body fluids (blood, ascites, cerebrospinal fluid, pericardial fluid, pleural fluid, saliva, and urine). Complementarily, whole exome sequencing on 86 liquid samples from 11 patients explored mutational information. ctDNA was detected in all fluids, but most frequently in blood, followed by ascites, pleural fluid, and cerebrospinal fluid. Phylogenetic reconstruction indicated that site representativeness varies by fluid type. Mutational and gene-level copy number analyses revealed clinically relevant information unique to non-blood fluids. These findings suggest a multi-fluid approach could enhance metastatic cancer monitoring and characterization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most frequent cancer in women1. Of the patients diagnosed with breast cancer, approximately 6% present with metastases at diagnosis and up to 30% will develop metastases later in their disease course2. Although recent therapeutic advances have increased the survival rate of patients with metastatic breast cancer, treatment resistance ultimately arises3,4,5,6. Tumor heterogeneity, both between and within metastases, is a key player of treatment failure7. Capturing this heterogeneity is challenging as performing a metastatic biopsy requires the lesion to be accessible and the risk of complications to be low. Also, this biopsy may not fully represent the entire metastasis from which it has been taken, nor the other metastases present in the body8,9.

Liquid biopsies, and especially plasma circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), offer opportunities to capture this heterogeneity. Plasma ctDNA is the part of plasma cell-free DNA that comes from both normal and tumor cells. These DNA fragments are released into the bloodstream through apoptosis, necrosis or secretion10. Liquid biopsies have shown promising results in cancer diagnosis11,12, evaluation of prognosis13,14,15, identification of treatment targets and markers of treatment resistance16,17,18, monitoring of disease burden and residual disease19,20 and monitoring of treatment efficacy21,22, as summarized in recent reviews10,23,24,25,26. Liquid biopsies are already part of daily clinical practice for treatment selection in patients with metastatic breast cancer, where the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the detection of PIK3CA and ESR1 mutations to prescribe the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors alpelisib and inavolisib and the selective estrogen receptor degraders elacestrant and imlunestrant, respectively. While less frequent, PTEN and AKT1 mutations are also targetable with the pan-AKT inhibitor capivasertib, and HER2-activating mutations with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor neratinib, both approved by the FDA26. Regarding disease monitoring, liquid biopsies recently showed a clinical benefit in driving treatment decision. For instance, the PADA-1 study (NCT0307901118) demonstrated the superiority of an early treatment switch from aromatase inhibitor to fulvestrant based on a rising ESR1 mutation in blood in patients with hormone receptor positive (HR-positive)/ Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 negative (HER2-negative) breast cancer18, similar results were observed with elacestrant in SERENA-6 (NCT0496493427,28). Other studies keep exploring the relevance of monitoring or characterizing the disease through liquid biopsy such as the c-Track TN trial (NCT03145961) in patients with triple-negative breast cancers29, plasmaMATCH (NCT03182634) in metastatic breast cancer17, DARE (NCT04567420) for patients with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive/HER2-negative breast cancers, and the future SURVIVE study (NCT05658172) for all breast cancer patients30. Taken together, these studies have exalted plasma ctDNA monitoring to the status of preferred approach for detecting genomic alterations to guide treatment.

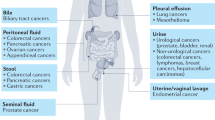

The aforementioned studies and most of the efforts in the liquid biopsy field focus on blood31, but cell free DNA, a prerequisite for ctDNA detection, has also been described in ascites32, urine33,34, pleural fluid32,35, pericardial fluid36, saliva37 and cerebrospinal fluid38,39. A few studies have shown that blood may not capture the full heterogeneity of the disease12,39 and the relevance of alternative body liquids has been acknowledged by clinical guidelines such as those from ESMO40 and in the literature41. However, the contribution and representativeness of each body liquid with regard to the overall intra- and inter-metastasis heterogeneity remain open questions. While highly relevant, addressing these issues is challenging as metastatic biopsies are limited to a few accessible organs, and as single tissue biopsies may not fully represent the intra- and inter-metastasis heterogeneity. Post-mortem tissue donation programs, frequently referred to as rapid autopsy programs, can overcome these challenges by allowing extensive collection of both body liquids and metastatic tissue samples shortly after death42,43,44.

In this study, we aimed at answering four open questions regarding liquid biopsies in patients with metastatic breast cancer. First: is ctDNA present in the different body liquids? Second, if ctDNA is detected in body liquids, is it representative of the different metastases present in the patient? Third: what are the most representative body liquids for each metastatic site? And finally, can we identify the same somatic alterations, both gene-level mutations and copy number changes, across all body fluids from the same patient? To answer these questions, we applied low-pass whole genome sequencing (lpWGS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES) to metastases and body liquids obtained in the context of our rapid tissue donation program UPTIDER (NCT0453169645).

Results

UPTIDER allows extensive sampling of metastases and body liquids from patients with metastatic breast cancer

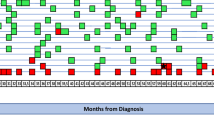

Twenty patients were included in our rapid tissue donation program between December 2020 and September 2022 (Fig. 1). The clinicopathological characteristics of their primary tumors are described in Fig. 2A, B and Supplementary Data 1. Four patients were de novo metastatic, while the others relapsed later after the primary diagnosis. The median time between primary diagnosis and death was 7.25 years (range: 1.25–35.58). The primary tumors of these patients were mainly hormone receptor-positive (HR-positive)/HER2-negative (n = 16), with only 3 being triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), and one HR-positive/HER2-positive. The main histotype was invasive breast carcinoma of no special type (IBC-NST, n = 10), followed by invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC, n = 5), then by mixed IBC-NST and ILC (n = 3 with one primary tumor having both histotypes, n = 1 with two distinct primaries harboring each a distinct histotype) and then with mixed IBC-NST and metaplastic squamous cell carcinoma (n = 1). A median of 46 tumor and liquid samples (range: 22–85) were collected per patient. The anatomical distribution of the collected tumor tissue samples is depicted in Fig. 2C. In the pre-mortem setting, the median number of tumor tissue and liquid samples per patient was 6 (range: 1–17) and 4 (range: 1–7), respectively. In the post-mortem setting, the median number of tumor and liquid samples per patient was 27 (range: 9–59) and 7 (range: 5–13), respectively. A complete overview of the available samples is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Twenty patients underwent a rapid autopsy within our post-mortem tissue donation program UPTIDER (NCT04531696). The list of body liquids is presented. Peripheral blood is sampled from a peripheral vein. Central blood is taken within the right atrium of the heart (at autopsy) or through a port-a-cath (pre and post-mortem). Liquid samples are collected during the metastatic disease, at post-inclusion and at autopsy. Of note, a few samples were also available at primary breast cancer diagnosis. Post-inclusion sampling occurs first upon signature of the informed consent form, second whenever possible when sampling is required for the treatment of the patient. Tumor tissue samples available during life of the patient are retrospectively collected and tumor tissue lesions are extensively collected at autopsy. The copy number profile obtained by the low-pass whole genome sequencing allows to determine the ploidy of the sample. If the profile is not diploid, ctDNA is considered present. Samples containing tumor are used to build phylogenetic reconstructions. Part of the liquid samples taken at autopsy are further processed with whole exome sequencing to obtain mutational data. Created in BioRender. Created in BioRender. Desmedt, C. (2025). https://BioRender.com/fldnmsf. ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, Met metastatic.

A Survival data for each patient: time from initial breast cancer diagnosis to first metastasis diagnosis (dark purple) and time between first metastasis diagnosis to patient’s death (light purple). Four patients were de novo metastatic. B Pathological data for the primary breast tumor of each patient. C Tissue sample distribution for each patient, considering all timepoints of collection. Total number of tissue samples per patient is reported on top of each bar. D Left panel: ctDNA detection status, based on lpWGS, for each liquid biopsy at the different timepoint of collection. If multiple samples were taken from the same liquid biopsy at the same timepoint, ctDNA was considered detected if it was found in at least one of the samples. In the pre-mortem setting blood can be either peripheral or central. Cases where the collection was not performed are indicated in light gray. Samples that did not pass the quality checks are indicated in dark gray. Of note, Pt2002 had a ventriculoperitoneal shunt and the ascites of Pt2025 was caused by portal hypertension. Blood at primary diagnosis was available for Pt2006, Pt2007, Pt2009, Pt2011, Pt2016, Pt2018, Pt2023, all samples passed QC, but none had ctDNA detected. Right panel: bar plot reporting the proportions observed in the collected samples. Top labels indicate the number of cases where ctDNA is detected out of the number of cases where at least one sample passed the QC. Corresponding percentages are also reported. ASC ascites, BL broad ligaments, bonesSpines vertebral bones, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, CT connective tissue, ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, Dx diagnosis, ER estrogen receptor, HER2 human epithelial growth receptor 2, IBC-NST invasive breast carcinoma of nonspecial type, ILC invasive lobular carcinoma, LN lymph node, lpWGS low-pass whole genome sequencing, Met metastatic, MSCC metaplastic squamous cell carcinoma, PeriC pericardial fluid, periph peripheral, PFL pleural fluid, PR progesterone receptor, QC quality check, Sintestine small intestine, ST soft tissue, URN urine.

ctDNA was detected in the seven types of body liquids

We evaluated the presence of ctDNA in the following 7 body liquids: ascites (also referred as peritoneal fluid), blood (peripheral and central), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), pericardial fluid, pleural fluid (left and right), saliva, and urine (Fig. 1). Regarding blood, peripheral and central samples are taken from a peripheral vein or the right atrium of the heart, respectively. The latter can be done either by direct puncture (at autopsy) or through a port-a-cath (pre or post-mortem). Three timepoints of collection were considered. First, during the metastatic disease (blood) for 11 patients who had consented to a longitudinal blood sampling in the context of the institutional blood biobank for breast cancer research at UZ Leuven. In this context, 7 blood samples were also collected at primary diagnosis. Second, post-inclusion in the UPTIDER program (peripheral blood, saliva, urine): once after signing the informed consent form and then with possible repetition in case of progression and/or treatment switch. Additional samples, such as CSF, pleural fluid or ascites, were collected only in case of a clinically indicated drainage. Of note, collection of other fluids than blood was only possible after amendment of the UPTIDER protocol on the 9th of March 2022. Third, at autopsy, shortly after death (all liquids but saliva due to sampling difficulty). The median time between death and start of the autopsy was 2.94 h (range: 1.80–5.87). Importantly, the liquid samples were always taken first, at the beginning of the autopsy, to maximize their quality in the downstream processing and analysis. ctDNA detection was considered positive if the low-pass whole genome data passed the quality checks (QC) and if the copy number profile was different from a diploid profile (cfr. Patients and Methods). The proportion of body liquids with at least one sample passing the QC for a given patient at a given time point was high overall (150/179 = 84%, Fig. 2D, total of greens vs. dark gray). This proportion varied by patient ranging from 36% to 100% but could not be associated to a peculiar patient/tumor trait (age at death, Odds Ratio (OR): 1.027, 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI) = 0.995–1.059, p = 0.095; histotype, OR = 0.599, 95%CI = 0.152–2.363, p = 0.464; molecular subtype, OR = 1.068, 95%CI = 0.319, 3.571, p = 0.915). The proportion of liquids passing the QC was 100%, 84% and 82% for samples taken during the metastatic disease, post-inclusion, and at autopsy, respectively. Of note, no association between sample specific post-mortem interval (ssPMI) and samples passing the QCs was found (OR = 1, 95%CI = 0.996, 1.004, p = 1). Regarding peripheral blood, the most common source of liquid biopsy, samples were available in 50% (10/20), 80% (16/20), and 100% (20/20) of the patients during the metastatic disease, post-inclusion, and at autopsy, respectively, with proportions passing the QCs being of 100% (10/10), 81% (13/16), and 80% (16/20), respectively (Fig. 2D, left panel). Among blood samples that passed the QCs, ctDNA was detected in 50% (5/10) of patients during metastatic disease, 69% (9/13) later at post-inclusion, and 75% (12/16) at autopsy, highlighting the dynamic nature of the disease and ctDNA status (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B).

At the post-inclusion timepoint, the ctDNA detection rate was 100% (2/2) in ascites, 69% (9/13) in blood, 18% (2/11) in urine and 8% (1/12) in saliva. At autopsy, the ctDNA detection rate was 92% (12/13) in ascites, 80% (12/15) in pleural fluid, 75% (12/16) in peripheral blood, 67% (10/15) in CSF, 63% (10/16) in central blood, 36% (5/14) in pericardial and 27% (3/11) in urine. Of note, patient Pt2025 was the only patient for whom ctDNA was not detected in the ascites collected at autopsy. This could be explained by the fact that the presence of ascites in this patient was caused by portal hypertension, which was diagnosed pre-mortem because of the high serum ascites albumin gradient. At autopsy still, ctDNA detection status in peripheral and central blood was different in 7% (1/14) of the patients for whom both were available. Also at autopsy, in the 8 patients (40%) for whom peripheral blood was uninformative (either because ctDNA could not be detected (4 patients) or because samples failed the QCs (4 other patients)), ctDNA was detected in one or more of the other body liquids as follows: 6 times in ascites (75%), 6 times in pleural fluid (75%), 4 times in CSF (50%), 2 times in pericardial fluid (25%), once in central blood (13%). Taken together, these results show that ctDNA can be detected in alternative body liquids than peripheral blood. Indeed, ctDNA was detected at least once in the 6 alternative body liquids tested in our study.

ctDNA fraction in body liquids is mostly high and not necessarily associated with the presence of metastases in the surrounding organs

The ctDNA fraction is defined as the ratio of circulating DNA originating from tumor cells over the total quantity of cell free DNA and allows to go beyond the binary presence/absence of ctDNA detection. We looked at the ctDNA fraction defined as the cancer DNA fraction estimated by ABSOLUTE (Patients and Methods, Fig. 3A). When detected, ctDNA fraction was high in all body liquids with a median of 54% (range: 16–95%). They were ranked as follows, considering all the timepoints of collection and by increasing median ctDNA fraction: saliva, central blood, peripheral blood, pleural fluid, ascites, CSF, pericardial fluid, and urine (Fig. 3A). Of note, per patient, and considering only liquid samples at autopsy, ascites and CSF often showed the highest ctDNA fractions (Supplementary Fig. 3).

A Violin plots describing the distribution of the ctDNA fraction per body liquids, 95 samples are considered. All timepoints of collection are considered together, all pre-mortem blood samples are reported in the peripheral blood category. Body liquids are ranked by increasing median ctDNA fraction. B–E Violin plots representing the ctDNA fraction in each fluid according to the presence of metastases in the surrounding organs. Four liquids are considered: pleural fluid (B, 14 samples), CSF (C, 15 samples), ascites (D, 12 samples), and urine (E, 10 samples) with regards to metastases in the pleura, the central nervous system (brain, meninges, and/or spinal cord), the peritoneum and the bladder, respectively. In case of multiple samples available for the same body liquid in a patient, the one having the highest ctDNA fraction is kept. Only samples obtained at autopsy are considered and a paired Wilcoxon test is performed in each case for which the two-sided p-value is reported in the plot. A–E In all boxplots the box delineates Q1, median and Q3, while the whisker ranges from Q1-1.5*IQR to Q3+1.5*IQR. Samples are biological replicates. Data are derived from the lpWGS. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. ASC ascites, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, CNS central nervous system, CT connective tissue, ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, IQR inter quartile range, lpWGS low-pass whole genome sequencing,Met metastatic, PeriC pericardial fluid, periph peripheral, PFL pleural fluid, Q1 first quartile, Q3 third quartile, URN urine.

ctDNA detection and fraction were also analyzed by molecular subtype and histotype, considering the unique clinical and biological features associated with these entities3,46. While the ctDNA fraction remained high overall, some variations in ctDNA detection were observed according to the subtypes (Supplementary Figs. 4–5). However, the small sample sizes in these subgroup analyses prevented any definitive conclusions.

We hypothesized that the ctDNA fraction in a particular body liquid could increase when the tumor was present in the surrounding organs. We therefore investigated the association between ctDNA fraction in different body liquids and the presence of tumor in the surrounding organs. We considered only the liquid samples collected at autopsy to compare with tumor information derived at the same timepoint. Presence of tumor in the organs was evaluated by considering the most recent images available for the patient as well as by a rigorous microscopic inspection after the autopsy. ctDNA fraction tended to be higher in pleural fluid and CSF when pleura and central nervous system (CNS: brain, meninges, or spinal cord) metastases were present, respectively (Fig. 3B, C). In contrast, no evidence of association with peritoneal and bladder invasion was observed for ctDNA fractions in ascites and urine, respectively (Fig. 3D, E). This suggests that these liquids could provide a valuable source of ctDNA, especially (as for pleural fluid, and CSF), but not solely (as for ascites and urine) for the metastases in proximity with the liquid.

Metastatic site representativeness assessed by phylogenetic reconstruction varies across body liquids

We showed that ctDNA was not only detectable in blood but also in other body liquids and demonstrated an association between ctDNA fraction and the presence of tumor in the surrounding tissues for some liquids. We then wanted to address if all the body liquids are conveying the same information or if some of them are more representative of certain metastatic sites. To measure the representativeness of each body fluid with respect to the metastatic sites, we used the phylogenetic distance between liquid and solid samples, which was based on the somatic copy number variation identified in the lpWGS data. As illustrated in Fig. 4 and in Supplementary Fig. 6-25, a phylogenetic tree was built using MEDICC2 for each patient including all solid and liquid samples where tumor DNA was detected and of sufficient purity (Patients and Methods). In MEDICC2, the phylogenetic distance is defined as the “minimum-event distance” which is the minimum number of evolutionary events needed to transform one genome into another47. Then, for each liquid, its pairwise distances with all the other samples of the tree were extracted and normalized into a Z-score to allow comparison between patients (Patients and Methods). The smaller the Z-score, the smaller the distance between the samples in the pair, relative to the other pairwise distances observed in the patient’s tree. By definition, a Z-score of zero indicates a phylogenetic distance equal to the average pairwise distances observed in the patient’s tree and will be used as a cutoff to distinguish relatively small distances (Z-score<0) from relatively long distances (Z-scores>=0). Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed for the 20 patients. The phylogenetic trees included a sample from the primary (taken at diagnosis) in 15 (75%) patients and contained a median of 31 samples (range: 11–64). Of note, despite the extensive sample collection, some metastatic sites, such as gallbladder, thyroid, lower limb muscle or cervix, remained rarely represented due to their low prevalence in patients with metastatic breast cancer. These are, however, still included in the trees and further description of the results but require caution for their interpretation.

A, C Clinical courses of patients Pt2003 and Pt2024 respectively. The main steps of the disease are reported. Metastatic and liquid samples taken in the metastatic setting are reported by dots. Created in BioRender. Desmedt, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/r3ic3w5, Desmedt, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/21lpe7w respectively. B, D Phylogenetic reconstructions computed using MEDICC2 based on the copy number events observed on low-pass whole genome sequencing data. Trees are rooted to a diploid ancestor. All liquid and tissue samples that passed the QC and contained tumor are included in the phylogenetic reconstructions, time point of collection is indicated in the first part of the label and can be premortem (DxS: Surgery at diagnosis, MD: metastatic disease) or postmortem (AD: after death). On each branch, genetic distances are reported in red, bootstrap value in blue. Color code is given according to the anatomical position of the tissue samples. Liquid samples are reported in cyan and their label ends by “_Liq”. When multiple samples of the same lesion are taken then a suffix “RgX” or “nX” is added. When samples different tumor of the same area are taken a suffix “LsX” is added. Data are derived from the lpWGS. ASC ascites, CT connective tissue, LN lymph node, L left, liq liquid, LL lower lobe, LN lymph node, lpWGS low-pass whole genome sequencing, P parietal, PFL pleural fluid, QC quality check, R right, RT radiotherapy, SCNA somatic copy number alteration, SLND sentinel lymph node biopsy, ST soft tissue, Th thoracic vertebra, UL upper lobe.

Regarding the peripheral blood, we found that it was relatively close (Median Z-score <0) to 9 metastatic sites and 4 body liquids (Fig. 5A). The 3 closest metastatic sites to peripheral blood were pancreas, lower limb muscle and adrenal glands. The 3 relatively closest body liquids to peripheral blood were CSF, pericardial fluid and central blood. On the contrary, peripheral blood was found distant (median Z-score >=0) from 22 metastatic sites and 2 body liquids. The 2 farthest body liquids from peripheral blood were urine and pleural fluid suggesting that they may not convey the same information. The 4 farthest metastatic sites from peripheral blood were the soft tissue of the neck, the cervix, the soft tissue of the thoracic wall and the thoracic lymph nodes. For these 4 metastatic sites that were not well represented in the peripheral blood, alternative liquids such as ascites, pericardial fluid, pleural fluid and CSF were found at least once to be more representative than peripheral blood (Supplementary Fig. 26, Supplementary Data 9–12). Indeed, each of the 6 alternative body liquids showed a unique representativeness profile as demonstrated in Fig. 5B–G. Central blood was close to 16 metastatic sites and 4 body liquids, and while being close to peripheral blood it seemed to better reflect fallopian tube, ovary and spleen (Fig. 5B). Ascites was close to 14 metastatic sites (stomach and connective tissue of the pelvic region especially) and 3 body liquids (Fig. 5C). Pleural fluid was close to 16 metastatic sites (especially gallbladder, lymph nodes from the neck, and soft tissue from the thoracic wall) and 5 body liquids (Fig. 5D). CSF was close to 18 metastatic sites and 6 body liquids. It was distant from only thyroid, bone, lung, and spleen (Fig. 5E). Pericardial fluid was close to 15 metastatic sites (especially kidney, fallopian tube, and ovary) and 5 body liquids (Fig. 5F). Urine was close to 11 metastatic sites (especially bladder and uterus) and 2 liquids but globally poorly represented in our series (Fig. 5G).

Violin plots describing the distribution of the Z-scores derived from the phylogenetic reconstructions of the 20 patients when considering all pairs of samples involving one body liquid at a time according to all other sample types (one panel per body liquid). Sample types are ordered by increasing median Z-score levels. A dashed line at 0 indicates the cutoff to distinguish between relative short (Z-score <0) and long distance (Z-score>=0). On the right, number of metastatic sites and body liquid falling in these two categories are reported below and above the line respectively. Only samples taken at autopsy are considered, samples from the lung are grouped irrespectively of their lobe of origin, and samples from the liver are grouped irrespectively of their segment of origin. In case of multiple samples available for the same body liquid in a patient, the one having the highest purity is chosen. The distribution is shown for peripheral blood (A, 369 samples), central blood (B, 292 samples), ascites (C, 387 samples), pleural fluid (D, 374 samples), CSF (E, 263 samples), pericardial fluid (F, 171 samples), and urine (G, 61 samples). In all boxplots the box delineates Q1, median and Q3, while the whisker ranges from Q1-1.5*IQR to Q3+1.5*IQR. Samples are biological replicates. Data are derived from the lpWGS. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. ASC ascites, BL broad ligament, bonesSpines vertebral bones, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, CT connective tissue, IQR inter quartile range, LN lymph node, lpWGS low-pass whole genome sequencing, PeriC pericardial fluid, periph peripheral, PFL pleural fluid, Q1 first quartile, Q3 third quartile, Sintestine small intestine, ST soft tissue, URN urine.

Of note, a high Z-score variability was often observed within each tissue/liquid type compared to a specific body liquid (Fig. 5), suggesting that the representativeness of the body liquids with regards to these tissue/liquid types may vary from one patient to another. A formal comparison of the distributions focusing on their medians and variances is provided for each fluid in Supplementary Data 2–8. A distinctive representativeness pattern and Z-score variability was also observed in the samples taken pre-mortem (Supplementary Fig. 27 and Supplementary Data 13–16).

In summary, we have shown that representativeness of the ctDNA in a body liquid with regard to the metastatic sites can be body liquid specific. Although peripheral blood reflects the state of many metastatic sites at a given time, other body liquids can provide complementary information.

Not all metastatic sites are equally represented in body fluids, with some having a specific body liquid correlate

After having considered each body fluid separately, we switched our focus towards metastatic sites to: (i) characterize what the overall representation of each metastatic site is in body liquids; (ii) identify the most suitable body liquids for detecting both common and less common metastatic sites. Indeed, distant relapses in patients with breast cancer are commonly observed in bones (67%), liver (41%) and lungs (36%)3. It also recurs in rarer, but difficult to characterize, metastatic sites, such as the brain (12%). We therefore investigated whether alternative body liquids could be more representative than blood at autopsy using the same phylogenetic approach as explained above (Fig. 6). First, considering all body liquids together for the different metastatic sites, it appears that metastases in some organs such as peritoneum and liver can be relatively well captured by liquids while metastases in other organs such as bones and lungs are less well captured (Fig. 6A). Second, with regards to common metastatic sites in breast cancer, it appears that in bones, liver and brain, at least one body liquid was more representative than peripheral blood. For bone metastases, focusing on vertebral metastases, CSF, ascites, pleural fluid, central blood, and pericardial fluid were genomically closer to these metastases than peripheral blood (Fig. 6B). For liver metastases, ascites, CSF and pericardial fluid were closer than peripheral blood (Fig. 6C). For brain metastases, CSF, ascites and pericardial fluid were closer than peripheral blood (Fig. 6D). For lung metastases, however, central and peripheral blood were equally close (Fig. 6E) and closer than the other fluids, but all showed relatively high Z-scores indicating a poor representativity of the metastatic site. A formal comparison of the distributions focusing on their medians and variances is provided in Supplementary Data 17–21. Taken together, these results show that not all metastatic sites are equally well represented in body liquids. They also suggest that alternative body liquids might provide complementary information to peripheral blood and that some metastatic sites can be closer to a specific body liquid.

A Violin plots describing the distribution of the Z-scores derived from the phylogenetic reconstructions of the 20 patients when considering pairs of samples involving a body liquid and a distant metastatic site. Metastatic sites are ordered by increasing median Z-score level. 577 samples are considered. Z-score distribution for all pairs of samples involving vertebral bones (B, 47 samples), liver (C, 170 samples), lung (D, 29 samples), brain (E, 29 samples), and a body liquid. In all boxplots the box delineates Q1, median and Q3, while the whisker ranges from Q1–1.5*IQR to Q3+1.5*IQR. Samples are biological replicates. Data are derived from the lpWGS. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. ASC ascites, BL broad ligament, bonesSpines vertebral bones, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, CT connective tissue, IQR inter quartile range, LN lymph node, PeriC pericardial fluid, periph peripheral, PFL pleural fluid, Q1 first quartile, Q3 third quartile, Sintestine small intestine, ST soft tissue, URN urine.

Exploratory analysis of gene level alterations highlights the potential of interrogating non-blood liquids

Precision oncology often relies on the detection of specific genomic alterations such as ESR1 mutations for selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD) or PIK3CA mutations for the inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT pathway. We therefore explored whether such alterations could be found in the different body liquids collected for a patient. To this end, we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) on the liquid samples collected at autopsy from 11 patients. In total, 86 liquid samples and their 11 matched normal controls were sequenced. All normal samples passed quality control (QC), and 81 out of 86 (94%) liquid samples met QC criteria (Supplementary Fig. 28) with a median coverage of 67X. Notably, we were able to rescue 11 of the 12 liquid samples that initially failed QC using lpWGS. One sample passed QC with lpWGS but failed WES, likely due to insufficient input material remaining after the initial lpWGS run.

Considering at least one Tier1 oncogenic mutation for ctDNA positivity (see Methods), detection rates were 64% for peripheral blood, 56% for ascites, 55% for central blood, 50% for pleural fluid, 30% for CSF, 44% for pericardial fluid, and 25% for urine (Supplementary Fig. 28). The list of mutations occurring in the genes of interest (oncogenic genes or genes related to endocrine resistance or resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors; see Methods) is available in Supplementary Data 22.

At the mutational level, private mutations to non-blood fluids were identified in all 11 patients analyzed (Fig. 7A, Supplementary Figs. 29–39). This is exemplified in patient Pt2003, in whom the highest mutational burden was detected in ascites and pleural fluid (Fig. 7B). Notably, only one mutation was shared across all liquid types (Fig. 7C). Of particular interest, the E885K PIK3CA mutation was detected exclusively in ascites and urine. In patient Pt2005, the H1047L PIK3CA mutation was detected only in pericardial and pleural fluid, not in blood (Supplementary Fig. 39). For patient Pt2006, the H1047L PIK3CA mutation was found only in ascites (Supplementary Fig. 40). In patient Pt2001, the H1047L PIK3CA mutation was present in blood, but also in ascites, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and pleural fluid. Additionally, the Q48H MYC mutation was found only in the CSF (Fig. 7D,E).

Only samples taken at autopsy are included. Only exonic and non-synonymous variants occurring in the genes of interest are considered (oncogenic genes or genes related to endocrine resistance or resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors; see Methods). A Bar plot showing the number of mutations detected in both blood (peripheral or central) and non-blood liquids (ascites, CSF, pericardial fluid, pleural fluid and urine), as well as private mutations to either blood or non-blood liquids, for each patient. 81 samples are considered. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. B, D Heatmaps showing the mutations detected in at least one liquid for patients Pt2001 (8 samples) and Pt2003 (7 samples), respectively. The numbers in the heatmaps indicate coverage in the given sample for the given mutation. The colors indicate the VAF of the mutation in gradient blue or the absence of coverage in gray. In case multiple samples of the same body liquids were available the maximal VAF is taken. C, E Upset plots showing the mutations found in the liquids of patients Pt2001 and Pt2003, respectively. The bar plot on the bottom left shows the total number of mutations per liquid. The bar plot at the top shows the size of the intersection defined by the black dots in the matrix at the bottom. A unique dot in a column indicates the number of unique alterations for the selected liquid. ASC ascites, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, del deletion, max maximal, PeriC pericardial fluid, periph peripheral, PFL pleural fluid, URN urine, UTR untranslated region, VAF variant allele frequency.

At the copy number level, gene level events, derived from lpWGS, were more consistent between liquids. Nonetheless, private somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) specific to non-blood fluids were observed in 15 out of 20 (75%) patients (Supplementary Figs. 40–60). In patient 2003, amplifications in CCND1, FGF3 and ERBB2 were detected in ascites and pleural fluid while ctDNA could not be detected with the lpWGS in other fluids (Supplementary Fig. 41). In patient 2004, FGFR1 amplification was detected in CSF and pericardial fluid but not blood, in patient 2006 FGF3 amplification and RB1 deletion were detected in both blood and non-blood fluids (Supplementary Fig. 46). In patient 2008, RB1 deletion was private to pleural fluid, CCNE2 amplification was private to ascites and pleural fluid (Supplementary Fig. 48). In patient 2009, FGFR1 and MYC amplifications as well as PTEN, RB1 and TP53 deletion were consistently seen in both blood and CSF (Supplementary Fig. 49).

Collectively, these findings indicate that non-blood fluids frequently capture alterations that are not observed in blood, some of which may have potential clinical relevance.

Discussion

In this study, using samples from our post-mortem tissue donation program UPTIDER (NCT0453169645), we investigated the presence and the fraction of ctDNA in 7 body liquids in female patients with metastatic breast cancer. We also questioned the representativeness of each of these liquids for different metastatic sites and explored the representation of each metastatic site in body liquids. Finally, we showed that clinically relevant genomic alterations could be private to non-blood liquids. Our findings are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 61.

We showed that ctDNA is not only detected in blood but also in ascites, CSF, pericardial fluid, pleural fluid, saliva, and urine. In addition to blood, ascites, pleural fluid, and CSF showed high detection rates. Importantly, in 40% (8/20) of the cases, peripheral blood was not contributive (either low quality sample or no ctDNA detected), but ctDNA could be detected in alternative body liquids. This is still the case for the different molecular and histological subtypes, though further validation is needed given the relatively small number of samples for some subtypes. When ctDNA was detected, ctDNA fraction was high overall, and it did not seem to be associated with tumor in the surrounding organs for ascites and urine. Of note, samples in this series were taken in the late stages of the disease, often while the patients were receiving palliative care. This could potentially explain the relatively high ctDNA fractions.

Pleural fluid and ascites have been reported in 7–11%48 and 3%49 of patients with breast cancer, respectively. Of note, ascites can be more prevalent in patients with lobular breast cancers given the high proportion of progression in the gastrointestinal tract in these patients3,50. Since these fluids can already be punctured for diagnosis or drained for comfort, they could be used as an alternative source of ctDNA in the clinic. Urine and saliva showed lower detection rates but remain of potential interest for clinical monitoring given their easy and minimally invasive sampling. The added value of non-blood liquids is not limited to breast cancer. Pleural fluid recently showed a complementary approach to blood in detecting lung cancer51. Urine recently showed promising results in detecting HPV positive oropharyngeal cancer52 and ascites showed higher sensitivity than blood in detecting peritoneal metastases in colorectal cancer53.

The representativeness of the different metastatic sites was not equal among the different body liquids. For instance, it seems that the representativeness of peripheral and central blood differed from each other at autopsy. This could be attributed to the fact that central blood is drawn from the right atrium of the heart, which is at the end of the general blood flow, whereas peripheral blood is collected from more upstream locations. We also showed that peripheral blood effectively represented the pancreas and adrenal glands, but was less effective in capturing the reproductive organs, soft tissues from the neck, and the thoracic wall. Of note, the incidence of ovarian metastasis ranges between 13% and 47% in patients with metastatic breast cancer54. For those organs, ascites, pleural fluid, pericardial fluid, and CSF were better liquid biopsy candidates than peripheral blood. This was confirmed when looking at the representation of each metastatic site individually, often showing a variability in the representativeness of each body liquid. We also found that CSF was genomically the closest fluid to brain metastases, as previously suggested by Fitzpatrick et al.39, but also that ascites was the closest liquid to the liver metastases. Our analysis also revealed that lung metastases were the most difficult to capture irrespective of the liquid biopsy source. So far, we have always been collecting central blood from the right atrium, which collects blood from the general circulation. It remains to be investigated whether collecting blood from the left atrium of the heart, which collects blood directly from the lungs, would increase the representativeness of central blood for lung metastases.

At the mutation and copy number level, we showed that alterations private to non-blood fluids could be observed. Especially, we showed that ESR1 and PIK3CA mutations could be private to non-blood fluids. Since treatments for breast cancer, such as elacestrant and imlunestrant (for ESR1 mutations), alpelisib or inavolisib (for PIK3CA mutations), capivasertib (for AKT1, PIK3CA, and PTEN mutations), neratinib (for HER2 mutations), or trastuzumab deruxtecan and trastuzumab emtansine (for ERBB2 amplifications among others), rely on detecting specific genetic alterations, our study suggests that analyzing other body liquids in addition to blood could improve the chances of finding these mutations. This could increase the number of patients who would be candidates for such treatments.

Altogether, these results reinforce the need for considering additional body liquids besides blood. Importantly, considering additional body liquids than blood is relevant independently of the primary site of cancer as long as metastases are observed in distant organs which is true for more than 50 cancer types55.

While promising, the prognostic clinical utility of a liquid biopsy-based monitoring, potentially including multiple liquid biopsy sources, is still to be proven. It is currently under investigation in patients with breast cancer within the SURVIVE study (NCT05658172) where an intensive blood-based ctDNA monitoring is compared to a standard monitoring. We are also developing a proof-of-concept study for a multi-fluid approach in the clinical setting for lobular breast cancer. The psychological burden imposed on patients by such monitoring should also be considered in future clinical applications and included in the risk-benefit analysis of these tests56, preferably after thorough discussions with patient advocacy groups.

Our study has several limitations. First, the use of lpWGS may not provide the most sensitive approach for ctDNA detection, but our samples are taken from patients with advanced disease where the tumor burden and thus the ctDNA fraction is expected to be high. Moreover, lpWGS has already been successfully applied for ctDNA detection, not only in the metastatic but also in the early setting in patients with breast cancer57,58. Secondly, lpWGS does not capture the mutational information which can be critical for breast cancer research59. This limitation is partially addressed with the use of WES on liquids from 11 patients. Expanding the sequencing to more patients and to the solid samples is an ongoing effort. Thirdly, the study is limited to 20 patients, which means it can only capture the disease scenarios present in these individuals. Consequently, the representativeness of each fluid is restricted to these 20 specific scenarios depicted by samples mainly taken at autopsy. Nevertheless, the number of samples per patient allows an unprecedented description of the metastatic disease. Future studies with a larger patient population are needed to elaborate on the current findings.

In conclusion, our study highlights the importance of exploring different sources of liquid biopsy in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Although more research is needed, it provides insights and hypotheses about which fluids might best reflect specific metastatic sites. A multi-liquid biopsy source approach could offer new, personalized options for diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment. We believe our findings are also relevant to the wider field of oncology.

Methods

Elements relative to the conduct of the UPTIDER program and the sample collection and management have been extensively described by Geukens et al.45. Key elements are reported here for clarity of the manuscript.

Sample collection and processing

Detailed protocols are provided in Supplementary Methods, including sample collection at inclusion, sample collection during the tissue donation procedure, cfDNA isolation from body liquids, DNA isolation from fresh frozen tissue and blood, as well as DNA isolation from FFPE tissue. Samples are conserved at the UZ/KU Leuven biobank and can be shared for future use pending material transfer agreement and ethical committee approval. For any requests, please contact the corresponding author.

Bioinformatics analysis – low-pass whole genome - mapping and copy number calling

All extracted cfDNA (supernatant) and tumor tissue samples, together with the 20 matched germline DNA (buffy coat) samples underwent lpWGS (0.1X coverage). Fastq files were mapped to the human reference genome (hg38) using bwa-mem60 and annotated using GENECODE61. Log2 coverage ratios were computed with CNVkit62 (0.9.8) and profiles with median absolute pairwise deviation < 0.35 were co-segmented per patient using the copynumber (1.1.1) R package63. Purity and ploidy were assessed by ABSOLUTE64 (1.0.6) ran with the following set of parameters: sigma.p=0.005, max.sigma.h=0.005, min.ploidy=1, max.ploidy=7, primary.disease="Breast Cancer". The solutions were then manually reviewed as follows: (i) for each patient, a sample showing a clear genomic profile was manually selected and considered as the “patient reference sample” (PRS); (ii) each sample was manually reviewed and an ABSOLUTE solution was manually selected (the default or a different one); (iii) when the manually selected solution was different from the default solution they were tested against the PRS, the one giving the best concordance was kept as being considered the most probable. In step (ii) if the genomic profile is too flat then copy numbers are not called and tumor is considered not detected (Supplementary Fig. 62). Then sample quality was established using 4 tiers: (i) samples with purity >30% were considered as Tier1, (ii) samples with a genomic profile concordant (CCC>0.6) with the PRS or any other Tier1 profile were considered Tier2 and Tier3 respectively, (iv) all the remaining liquid samples were considered Tier4. All Tier1-4 samples were kept for downstream analysis. For gene-level copy number, the Log2 ratio thresholds for detecting deletions and amplifications were set to -0.4 and 0.9, respectively.

Bioinformatics analysis—phylogenetic reconstruction

Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed using MEDICC247 (1.1.2) for each patient. All samples for which copy number could be called were added to the reconstruction independently of the timepoint of collection. The tree was rooted to a diploid state. Default parameters were used, and a bootstrap value was set to 50 iterations. In each patient, pair-wise distances were extracted and converted into Z-scores. Phylogenetic trees were then parsed and plotted using treeio (v1.24.3) and tidytree (0.4.5) R packages.

Bioinformatics analysis—whole exome—mapping

Raw paired-end reads were first trimmed to remove sequencing adapters and low-quality bases using Trimmomatic (v0.35), then aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using bwa-mem (v0.7.5)65,66. PCR duplicates were identified with Picard MarkDuplicates (v3.3.0), and base quality score recalibration (BQSR) was performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, v4.6.1)67,68.

Bioinformatics analysis—whole exome—mutation calling and oncogenic definition

Somatic variant calling was conducted using Mutect2 in multi-sample mode, where samples of a patient are jointly analysed to increase sensitivity for low-frequency variants69. Parameters were kept as default. Following variant calling, variant quality filtering was performed using GATK’s FilterMutectCalls function68. Only high-confidence somatic variants were kept (FILTER=PASS) and annotated using Funcotator (GATK) with COSMIC's Cancer Gene Census (CGC)68,70, OncoKB, and Variant Effect Predictor (VEP, v111.0; Ensembl)71,72. Finally, mutations were considered in Tier1 if the depth was sufficient for their VAF according to predetermined cutoffs73. Variants were classified as oncogenic if they met one of the following criteria: (i) listed in the CGC database; (ii) listed in OncoKB with known oncogenicity; (iii) located in a breast cancer driver gene classified by VEP as a high-impact variant in a tumor suppressor gene, or as moderate/modifier impact in an oncogene74. Breast cancer driver genes were retrieved from IntoGen75 and Nik-Zainal et al. 201659. Samples were passing the quality checks if the median coverage was equal to or greater than 10X or if at least one somatic mutation was detected. ctDNA positivity was defined as having one Tier 1 oncogenic mutation.

Bioinformatics analysis—genomic alterations visualization

Regarding the heatmap visualizations, all alterations observed in a gene considered as a driver in Nik-Zainal et al.59, or associated with CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance or endocrine resistance in literature76,77,78, were retained. For mutations, oncogenic mutations described above, were added to the list. Only exonic and non-synonymous variants were shown. For copy numbers, all deletions and amplifications were displayed.

Statistics and reproducibility

Overall survival was estimated as the time between diagnosis of the primary breast cancer and death. Associations between quality check status (event = QC passed) and phenotypic traits (age at death (continuous), histotype (NST vs other), molecular subtype (HR-positive vs TNBC) and sample specific post-mortem interval (continuous) were assessed with a mixed effects logistic regression with a random effect on patient ID. Associations between continuous variables (e.g., ctDNA fraction) and different times of collection (pre vs post-mortem) or different locations (peripheral vs central blood) were assessed by paired Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Associations between organ involvement and ctDNA fraction were assessed by Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Median comparison between z-score distributions were performed with a Wilcoxon-rank-sum test, while variance comparison was performed with a Fisher test. P-values were two-sided, correction for multiple testing was performed using the Benjamini & Hochberg procedure. All analyses were performed in R Statistical Software (v4.3; R Core Team 2023). No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Inclusion & ethics: the UPTIDER program

UPTIDER is a monocentric post-mortem tissue donation program for patients with end-stage breast cancer (NCT04531696, local ethics number: S64410, approval 30th November 2020). All adult patients, regardless of sex and gender, with metastatic breast cancer (either de novo or secondary metastasized) in their last line(s) of treatment are eligible for inclusion, if they are either treated at University Hospitals Leuven or referred to it specifically for the project. Gender is not captured. Exclusion criteria are the presence of transmissible diseases that can form a risk to the health of researchers handling the body samples (e.g., HIV, HCV, tuberculosis), and place of residence outside the area covered by the transport company. Here, all patients are females as noted in their electronic health record.

Data availability

The clinical, histological and processed DNA sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in a code capsule in the CodeOcean repository under the accession code: https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.7526782.v1. Additionally, the raw sequencing data (FASTQ files for the lpWGS and the WES) have been deposited in the EGA repository under the accession codes: EGAS50000001302 (lpWGS) [https://ega-archive.org/studies/EGAS50000001302] and EGAS50000001303 (WES) [https://ega-archive.org/studies/EGAS50000001303]. Data access requests should be submitted through the EGA portal, which will inform the relevant DAC (dac@uzleuven.be, of which FR and CD are members). The DAC will then request a project proposal, which will undergo internal validation. If approved, the data will be released upon ethical committee approval and the signing of a data transfer agreement. The entire process is a matter of weeks. Consent for publication of the clinical data was obtained at the time of study inclusion through the signing of the informed consent form. In addition, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) does not apply to deceased patients. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The R code along with the processed data required to reproduce the analysis is provided in a code capsule in the CodeOcean repository (https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.7526782.v1).

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Courtney, D. et al. Breast cancer recurrence: factors impacting occurrence and survival. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 191, 2501–2510 (2022).

Harbeck, N. et al. Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 5, 66 (2019).

Miglietta, F., Bottosso, M., Griguolo, G., Dieci, M. V. & Guarneri, V. Major advancements in metastatic breast cancer treatment: when expanding options means prolonging survival. ESMO Open 7, 100409 (2022).

Al Sukhun, S. et al. Systemic treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer: ASCO resource–stratified guideline. JCO Glob. Oncol. 10, e2300285 (2024).

Gennari, A. et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1475–1495 (2021).

McGranahan, N. & Swanton, C. Clonal heterogeneity and tumor evolution: past, present. Future Cell 168, 613–628 (2017).

Geukens, T. et al. Intra-patient and inter-metastasis heterogeneity of HER2-low status in metastatic breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 188, 152–160 (2023).

Yates, L. R. et al. Subclonal diversification of primary breast cancer revealed by multiregion sequencing. Nat. Med. 21, 751–759 (2015).

Wan, J. C. M. et al. Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 223–238 (2017).

Sozzi, G. et al. Detection of microsatellite alterations in plasma DNA of non-small cell lung cancer patients: a prospect for early diagnosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 5, 2689–2692 (1999).

Batool, S. M. et al. The liquid biopsy consortium: challenges and opportunities for early cancer detection and monitoring. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 101198 (2023).

Swisher, E. M. et al. Tumor-specific p53 sequences in blood and peritoneal fluid of women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 193, 662–667 (2005).

Dickinson, K. et al. Circulating tumor DNA and survival in metastatic breast cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2431722 (2024).

Bettegowda, C. et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 224ra24–224ra24 (2014).

Kimura, H. et al. Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in serum as a predictor of the response to gefitinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 3915–3921 (2006).

Turner, N. C. et al. Circulating tumour DNA analysis to direct therapy in advanced breast cancer (plasmaMATCH): a multicentre, multicohort, phase 2a, platform trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1296–1308 (2020).

Bidard, F.-C. et al. Switch to fulvestrant and palbociclib versus no switch in advanced breast cancer with rising ESR1 mutation during aromatase inhibitor and palbociclib therapy (PADA-1): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 23, 1367–1377 (2022).

Dawson, S.-J. et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1199–1209 (2013).

Tie, J. et al. Circulating tumor DNA as an early marker of therapeutic response in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 26, 1715–1722 (2015).

Rossi, G. & Ignatiadis, M. Promises and pitfalls of using liquid biopsy for precision medicine. Cancer Res. 79, 2798–2804 (2019).

Siravegna, G. et al. How liquid biopsies can change clinical practice in oncology. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1580–1590 (2019).

Ignatiadis, M., Sledge, G. W. & Jeffrey, S. S. Liquid biopsy enters the clinic—implementation issues and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 297–312 (2021).

Hofman, P., Heeke, S., Alix-Panabières, C. & Pantel, K. Liquid biopsy in the era of immuno-oncology: is it ready for prime-time use for cancer patients? Ann. Oncol. 30, 1448–1459 (2019).

Lawrence, R., Watters, M., Davies, C. R., Pantel, K. & Lu, Y.-J. Circulating tumour cells for early detection of clinically relevant cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 487–500 (2023).

Xi, J., Ma, C. X. & O’Shaughnessy, J. Current clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA testing in breast cancer: a practical approach. JCO Oncol. Pract. 20, 1460–1470 (2024).

Turner, N. et al. Design of SERENA-6, a phase III switching trial of camizestrant in ESR1—mutant breast cancer during first-line treatment. Future Oncol. 19, 559–573 (2023).

Turner, N. C. et al. Camizestrant + CDK4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i) for the treatment of emergent ESR1 mutations during first-line (1L) endocrine-based therapy (ET) and ahead of disease progression in patients (pts) with HR+/HER2– advanced breast cancer (ABC): Phase 3, double-blind ctDNA-guided SERENA-6 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 43, LBA4 (2025).

Turner, N. C. et al. Results of the c-TRAK TN trial: a clinical trial utilising ctDNA mutation tracking to detect molecular residual disease and trigger intervention in patients with moderate- and high-risk early-stage triple-negative breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 34, 200–211 (2023).

Mergel, F. et al. Abstract PO1-20-05: SURVIVE study – a multicenter, randomized, controlled phase 3 superiority trial, evaluating liquid biopsy guided intensified follow-up surveillance in women with intermediate-to high-risk early breast cancer. Cancer Res 84, 20–05 (2024).

Xie, W., Suryaprakash, S., Wu, C., Rodriguez, A. & Fraterman, S. Trends in the use of liquid biopsy in oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 612–613 (2023).

Husain, H. et al. Cell-free DNA from ascites and pleural effusions: molecular insights into genomic aberrations and disease biology. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16, 948–955 (2017).

Botezatu, I. et al. Genetic analysis of DNA excreted in urine: a new approach for detecting specific genomic DNA sequences from cells dying in an organism. Clin. Chem. 46, 1078–1084 (2000).

Chan, K. C. A., Leung, S. F., Yeung, S. W., Chan, A. T. C. & Lo, Y. M. D. Quantitative analysis of the transrenal excretion of circulating EBV DNA in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 4809 (2008).

Sriram, K. B. et al. Pleural fluid cell-free DNA integrity index to identify cytologically negative malignant pleural effusions including mesotheliomas. BMC Cancer 12, 428 (2012).

Yang, S. R. et al. Targeted deep sequencing of cell-free DNA in serous body cavity fluids with malignant, suspicious, and benign cytology. Cancer Cytopathol. 128, 43–56 (2020).

Mithani, S. K. et al. Mitochondrial resequencing arrays detect tumor-specific mutations in salivary rinses of patients with head and neck cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 7335–7340 (2007).

De Mattos-Arruda, L. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid-derived circulating tumour DNA better represents the genomic alterations of brain tumours than plasma. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–6 (2015).

Fitzpatrick, A. et al. Assessing CSF ctDNA to improve diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic monitoring in breast cancer leptomeningeal metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 1180–1191 (2022).

Pascual, J. et al. ESMO recommendations on the use of circulating tumour DNA assays for patients with cancer: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 33, 750–768 (2022).

Tivey, A., Church, M., Rothwell, D., Dive, C. & Cook, N. Circulating tumour DNA—looking beyond the blood. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 600–612 (2022).

Geukens, T. et al. Research autopsy programmes in oncology: shared experience from 14 centres across the world. J. Pathol. 263, 150–165 (2024).

Hessey, S., Fessas, P., Zaccaria, S., Jamal-Hanjani, M. & Swanton, C. Insights into the metastatic cascade through research autopsies. Trends Cancer 9, 490–502 (2023).

Iacobuzio-Donahue, C. A. et al. Cancer biology as revealed by the research autopsy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 19, 686–697 (2019).

Geukens, T. et al. Rapid autopsies to enhance metastatic research: the UPTIDER post-mortem tissue donation program. NPJ Breast Cancer 10, 31 (2024).

Van Baelen, K. et al. Current and future diagnostic and treatment strategies for patients with invasive lobular breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 33, 769–785 (2022).

Kaufmann, T. L. et al. MEDICC2: whole-genome doubling aware copy-number phylogenies for cancer evolution. Genome Biol. 23, 241 (2022).

Hirata, T. et al. Efficacy of pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions in breast cancer patients. Eur. Respir. J. 38, 1425–1430 (2011).

Ayantunde, A. A. & Parsons, S. L. Pattern and prognostic factors in patients with malignant ascites: a retrospective study. Ann. Oncol. 18, 945–949 (2007).

Switzer, N. et al. Case series of 21 patients with extrahepatic metastatic lobular breast carcinoma to the gastrointestinal tract. Cancer Treat. Commun. 3, 37–43 (2015).

Lin, Y., Ji, S., Jiang, Y. & Wang, T. Comparative analysis of the mutation detection using malignant pleural effusion and blood cell-free DNA samples in lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, e20518–e20518 (2023).

Bhambhani, C. et al. ctDNA transiting into urine is ultrashort and facilitates noninvasive liquid biopsy of HPV+ oropharyngeal cancer. JCI Insight 9, e177759 (2024).

Erve, I. et al. Detection of tumor-derived cell-free DNA from colorectal cancer peritoneal metastases in plasma and peritoneal fluid. J. Pathol. Clin. Res 7, 203–208 (2021).

Akizawa, Y. et al. Ovarian metastasis from breast cancer mimicking a primary ovarian neoplasm: a case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 15, 135 (2021).

Nguyen, B. et al. Genomic characterization of metastatic patterns from prospective clinical sequencing of 25,000 patients. Cell 185, 563–575.e11 (2022).

Hamilton, J. G., Watsula-Morley, A. & Latham, A. Psychosocial issues related to liquid biopsy for ctDNA in individuals at normal and elevated risk. in Psycho-Oncology (ed Jacobsen, P. B.) 116–118 (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Prat, A. et al. Circulating tumor DNA reveals complex biological features with clinical relevance in metastatic breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 1157 (2023).

Garcia-Murillas, I. et al. Whole genome sequencing-powered ctDNA sequencing for breast cancer detection. Ann. Oncol. 36, 673–681 (2025).

Nik-Zainal, S. et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature 534, 47–54 (2016).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Frankish, A. et al. GENCODE 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D916–D923 (2021).

Talevich, E., Shain, A. H., Botton, T. & Bastian, B. C. CNVkit: Genome-wide copy number detection and visualization from targeted DNA sequencing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004873 (2016).

Nilsen, G. et al. Copynumber: efficient algorithms for single- and multi-track copy number segmentation. BMC Genom. 13, 1–16 (2012).

Carter, S. L. et al. Absolute quantification of somatic DNA alterations in human cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 413–421 (2012).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114 (2014).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Picard Tools - By Broad Institute. https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/.

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Benjamin, D. et al. Calling Somatic SNVs and Indels with Mutect2 https://doi.org/10.1101/861054.

Sondka, Z. et al. The COSMIC Cancer Gene Census: describing genetic dysfunction across all human cancers. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 696–705 (2018).

Chakravarty, D. et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis. Oncol. 1–16 https://doi.org/10.1200/po.17.00011 (2017).

McLaren, W. et al. The ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 1–14 (2016).

Frampton, G. M. et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013 31, 1023–1031 (2013).

Nik-Zainal, S. Landscape of Somatic Mutations in 560 Breast Cancer Whole-Genome Sequences https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17676.

Martínez-Jiménez, F. et al. A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 555–572 (2020).

Wander, S. A. et al. The genomic landscape of intrinsic and acquired resistance to cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors in patients with hormone receptor–positive metastatic. Breast Cancer Cancer Discov. 10, 1174–1193 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. INK4 tumor suppressor proteins mediate resistance to CDK4/6 kinase inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 12, 356–371 (2022).

Ghosh, A. et al. Genomic hallmarks of endocrine therapy resistance in ER/PR+HER2- breast tumours. Commun. Biol. 8, 207 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients participating in this program, as well as their families who supported them. We thank healthcare staff and researchers who have been supportive of this project from the very beginning. We want to thank Els Tuerlinckx and colleagues for their relentless support at the morgue, Stefan Ghysels and colleagues for performance of the MRIs at unconventional hours, the Laboratory for Experimental Oncology for helping us to set up our laboratory work and standard operating procedures, the department of general medical oncology, gynecology, and palliative care for their support and help with included patients, Nicole Hensmans and Nancy Trolin for their administrative and logistical support, the pathologists and technicians at the department of pathology for their support with the procurement and analysis of samples. This study was funded by the Klinische Onderzoeks- en Opleidingsraad (KOOR) of University Hospitals Leuven (Uitzonderlijke Financiering 2020), C1 of KU Leuven (C14/21/114), the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO G082524N), the Stichting tegen Kanker foundation (STK C/2022/2046) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF, nr 1328136). Additionally, T.G., F.R., H.W. and G.F. are funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO: 1S76522N, 1297322N, 1802222N, 1800125N, respectively), M.D.S., and M.M. by the Luxemburg Cancer Foundation, M.D.S., K.V.B., K.B., J.V.C., C.C. by the fund Nadine de Beauffort, F.R., C.D., M.M. and H.-L.N. by the European Research Council (ERC, FAT-breast cancer 101003153), F.R., M.M., K.V.B. by a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (Award ID = BCRF-24-212), K.V.B. by the ASCO/Lobular Breast Cancer Alliance Young Investigator Award, and S.L. by the Belgian Cancer Foundation (2020-103), G.F. is recipient of post-doctoral mandate sponsored by the KOOR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.R., C.D. Patient inclusion: P.N., H.W., K.B., T.G., K.V.B., J.V.C. Sample collection: F.R., M.M., K.B., K.V.B., J.V.C., G.Z., T.G., M.D.S., A.M., H.L.N., A.P., S.L., H.I., I.B., C.C., S.H., M.N., P.V., P.N., W.D.B., G.F. DNA-seq: F.R., A.M, E.R., E.V., T.V.B., M.N., B.B., D.L. Data curation: F.R., M.M., K.B., K.V.B., J.V.C., G.Z., T.G., M.D.S., A.M., H.L.N., A.P., S.L., H.I., C.C., S.H., M.N. Data analysis: F.R., M.M., E.B., J.D., C.D. Original draft: F.R, C.D. Review and editing: all authors. Funding acquisition: F.R., M.M., H.W., G.F., C.D. Supervision: C.D.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Cherie Blenkiron and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Richard, F., Maetens, M., Van Baelen, K. et al. ctDNA detectability and representativeness in seven body liquids from patients with metastatic breast cancer. Nat Commun 16, 10826 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65838-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65838-1