Abstract

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a common metabolic disorder in pregnancy, but the underlying mechanism has not been fully clarified. Using metabolomic profiling of second-trimester saliva, serum, and urine, we identify 54 metabolites altered in GDM that converge on key metabolic pathways. Fifty GDM biomarkers independently associated with abnormal maternal glucose and insulin resistance are selected to construct GDM discriminant models (internal test AUC: 0.868; real-world test: 0.796). These GDM biomarkers are also associated with clinical profiles and adverse outcomes, thereby predicting maternal and neonatal risks (internal test AUC: 0.764 and 0.838; real-world test: 0.726 and 0.792, respectively). Eleven GDM biomarkers are already altered in the first trimester, which can be used for the early prediction of GDM (internal test AUC: 0.767; real-world test: 0.744). In this work, changes and interactions of metabolites in saliva, serum, and urine in the second trimester are first identified in GDM, providing insights into its pathogenesis and potential early prediction and prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a metabolic disorder characterized by increased insulin resistance and islet β-cell dysfunction, resulting in hyperglycemia first recognized in pregnancy1. GDM is one of the most common complications of pregnancy, with a global prevalence as high as 14.0%2. It has been shown that GDM is associated with adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes, such as preeclampsia, cesarean section, preterm delivery, macrosomia, and stillbirth3,4. Furthermore, the metabolic abnormalities underlying GDM may persist from pregnancy to the postpartum period, increasing the long-term risks of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other metabolic diseases for both the mother and infant5. Therefore, early prediction and prognostic assessment are essential for pregnant women with GDM. Although studies have proposed several metabolic pathways that may contribute to insulin resistance and GDM onset, such as amino acid metabolism disorder6, mitochondrial dysfunction7, oxidative stress8, etc, the underlying metabolic pathogenesis remains controversial and insufficiently explored, warranting further investigation.

Metabolomics is the qualitative or quantitative analysis of water-soluble small molecule metabolites (MW < 1000 Da), which directly reflects the activities that are occurring or have occurred in the body. Compared to other omics, metabolomics is characterized by the characteristics of easy detection, showing functional information in biological pathways, and common study techniques. Therefore, it is now widely used in GDM research9. As the metabolome is the final downstream product of gene transcription, it can reflect some epigenetic and genetic interactions in the pathogenesis of GDM10. Metabolomics can also characterize normal physiological and pathological states, and thus identify underlying biological phenomena associated with GDM9. Several studies have demonstrated significant alterations in metabolites in the serum, plasma, urine, feces, and breast milk of pregnant women with GDM in comparison with healthy pregnant women. These alterations were involved in the disorder of multiple metabolic pathways in GDM, such as amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids, and purines11,12,13. Although these studies demonstrated the universality and diversity of metabolomics in GDM, they were only performed in single biofluid samples (most commonly plasma or serum), making it difficult to obtain a more holistic view of metabolic changes in GDM from multiple perspectives.

Saliva is a biofluid sample that can be obtained noninvasively, and it is suitable for human metabolomics studies due to its high water content, limiting interference from lipid molecules14. Thousands of molecules that reflect biological metabolism can be extracted from saliva, which has therefore been used to explore the occurrence and development of diseases15. A salivary metabolomics study showed a significant increase in the acetic acid level in type 1 diabetes16. Our group also found disturbances of amino acid metabolism, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and purine metabolism in the saliva of patients with type 2 diabetes using nanostructure-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (NALDI-TOF-MS)17. The advantages of this technique for reliable and high-throughput metabolic profiling have been reported18,19, but there have been no studies on the salivary metabolomics of GDM. To date, only one study, which included nine cases of GDM, has used LC-MS/MS-based untargeted metabolomic analysis to explore differences in salivary metabolites and their association with gingivitis20. However, due to the small sample size, its results need to be further verified. Studies are required to examine whether the metabolic profile is altered in the saliva, as well as whether the metabolic profiles of saliva, serum, and urine are correlated in pregnant women with GDM.

In this observational study, we compare the metabolic profiles of saliva, serum, and urine between GDM and non-GDM patients in the second trimester using NALDI-TOF-MS for the first time. The changes and interactions of metabolites are analyzed to explore the metabolic characteristics and pathogenesis of GDM. GDM biomarkers are further identified to construct GDM discriminant models and adverse outcome prediction models. In addition, first-trimester changes in these GDM biomarkers and their association with the risk of GDM are also investigated.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A flow diagram of the study protocol is shown in Fig. 1. The baseline characteristics of the cohort 1 and cohort 2 are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were observed in maternal age, gravidity, parity, education status, body mass index (BMI), and gestational weeks (GW) at sample collection between GDM and non-GDM patients in each cohort. However, family history of diabetes, blood glucose, including fasting blood glucose (FBG), blood glucose after 1 h (1h-BG), blood glucose after 2 h (2h-BG), and HbA1c, and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) were significantly higher in GDM patients than in non-GDM patients (P < 0.05).

Altered metabolic profiling of second-trimester multivariate samples in GDM

Metabolic profiles of quality control (QC) samples were analyzed, which demonstrated the stability and reliability of the detection platform (Supplementary Fig. 1). In saliva, serum, and urine, 370 metabolites were identified, of which 14 were present in all three samples (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To explore the changes in metabolic profiles of second-trimester multivariate samples in GDM, differentially expressed metabolites were initially identified in the cohort 1 and verified in cohort 2 (see Supplementary Data for secondary identification). The metabolites in saliva, serum, and urine significantly differed between GDM and non-GDM patients. In both the cohort 1 and cohort 2, seven saliva metabolites (e.g., oxalacetic acid, pimelic acid, 2-naphthol were decreased; l-glutamine, dimethylethanolamine, and taurine were increased., 40 serum metabolites (e.g., l-3-hydroxykynurenine, jasmonic acid, l-homocystine were decreased; lysylglycine, 1-salicylate glucuronide, and asymmetric dimethylarginine were increased., and seven urine metabolites (e.g., taurine, pyridoxamine, and thiodiacetic acid were decreased) were significantly altered, known as differential metabolites. These differential metabolites were enriched in alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, pyrimidine metabolism, and other metabolic pathways, which may synergistically lead to glucose metabolism disorders in GDM (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3).

a Venn diagram showed that seven saliva metabolites, 40 serum metabolites, and seven urine metabolites were significantly altered in both the cohort 1 and cohort 2, which were considered differential metabolites. b Diagram of metabolic pathway disorder mechanism. Arrows indicated the flow of differential metabolites. Blue nodes represented metabolites with significant changes in saliva, red nodes represented metabolites that have significantly changed in serum, and yellow nodes represented metabolites with significant changes in urine. The arrows next to metabolite names indicate their trend of change in GDM. The dark blue nodes represented key metabolites of metabolic pathways that can act as mediators linking differential metabolites. Source data were provided as a Source Data file.

The common changes and interactions of differential metabolites in saliva, serum, and urine of GDM patients were also analyzed. Of the above 54 differential metabolites, taurine was significantly increased in saliva but decreased in urine, whereas 5-methylfuran-2-carboxylic acid was significantly decreased in both serum and urine of GDM patients; no differential metabolites were found in both saliva and serum (Fig. 3a and 3b). Moreover, correlation analysis between differential metabolites of saliva, serum, and urine showed that six saliva metabolites, 20 serum metabolites, and five urine metabolites were related to each other. In saliva, the l-glutamine level was significantly associated with ten serum metabolites, whereas dimethylethanolamine was positively associated with five serum metabolites. Serum bisnorbiotin was negatively associated with the saliva oxalacetic acid and four urine metabolites. Urine xanthine was significantly associated with eight serum metabolites (Fig. 3c).

a Venn diagram of differential metabolites in second-trimester multivariate samples showed one common differential metabolite in saliva and urine, one common differential metabolite in serum and urine, but no common differential metabolites in saliva and serum. b Boxplots showed relative intensities of common differential metabolites in GDM (red, n = 50) and non-GDM (blue, n = 50) groups. Each box represented the 25th (Q1), median (Q2) and 75th (Q3) percentiles, and the whiskers extended to 1.5×IQR. Each point represented an individual sample. Statistical significance between groups was assessed using the two-sided Mann-Whitney U test with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. c Correlation analysis of differential metabolites in saliva, serum, and urine indicated that six saliva metabolites, 20 serum metabolites, and five urine metabolites were related to each other. Blue nodes represented differential metabolites in saliva, red nodes represented differential metabolites in serum, and yellow nodes represented differential metabolites in urine. Blue arrows indicated the negative correlations, and purple arrows indicated the positive correlations. Source data were provided as a Source Data file.

GDM biomarkers from second-trimester multivariate samples associated with abnormal maternal glucose values and insulin resistance in GDM

To identify GDM biomarkers, we analyzed the associations between 54 differential metabolites and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) glucose values and HOMA-IR. Six differential metabolites in saliva, 37 in serum, and seven in urine demonstrated significant associations with at least one index among FBG, 1h-BG, 2h-BG, and HOMA-IR, and were regarded as GDM biomarkers. There were 16, 44, 45, and three metabolites in the multivariate samples associated with FBG, 1h-BG, 2h-BG, and HOMA-IR, respectively. However, only serum tyrosol 4-sulfate was positively associated with all OGTT glucose values and HOMA-IR, whereas 14 serum metabolites (e.g., asymmetric dimethylarginine, lysylglycine, malic acid, pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid, tyramine-O-sulfate, 5-methylfuran-2-carboxylic acid, mevalonic acid) were associated with all three OGTT glucose values (Fig. 4).

The string diagram showed the significant association of GDM biomarkers and the OGTT glucose values and HOMA-IR. Blue nodes represented GDM biomarkers in saliva, red nodes represented GDM biomarkers in serum, and yellow nodes represented GDM biomarkers in urine. Blue dashed arrows indicated the negative correlations and red solid arrows indicated the positive correlations. Source data were provided as a Source Data file.

Models based on GDM biomarkers constructed to distinguish GDM and non-GDM

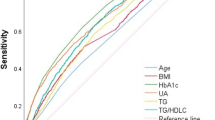

Utilizing the 50 GDM biomarkers, we constructed seven discriminant models to evaluate their abilities to distinguish between GDM and non-GDM. A total of three metabolite features in saliva, eight in serum, three in urine, ten in saliva and serum, eight in saliva and urine, ten in serum and urine, and 13 in multivariate sample metabolomics were screened out to construct the seven discriminant models (Supplementary Table 1). Among them, GDM discriminant model constructed with multivariate samples exhibited superior performance, achieving an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) value of 0.868 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.781–0.955), with sensitivity and specificity of 82.9% and 80.0%, respectively. Notably, models constructed using binary noninvasive samples (saliva and urine) demonstrated better diagnostic performance (AUC value, 0.836, 95%CI, 0.738–0.933) than those constructed with single invasive samples (serum, AUC value, 0.779, 95%CI, 0.670–0.888) (Fig. 5a). The GDM discriminant model constructed using multivariate samples was further verified externally in the cohort 3, achieving an AUC value of 0.796 (95%CI, 0.695–0.897) with sensitivity of 80.0% and specificity of 75.8% (Fig. 5b).

a Seven discriminant models were constructed using selected features from GDM biomarkers in saliva, serum, and urine. Their performances in the internal test set were shown. The optimal GDM discriminant model was constructed from multivariate samples with an AUC value of 0.868 (95%CI, 0.781–0.955), followed by the binary samples models (saliva+serum: 0.842 [0.744–0.940], saliva+urine: 0.836 [0.738–0.933], serum+urine: 0.861 [0.761–0.956]) and the single sample models (saliva: 0.773 [0.605–0.942], serum: 0.779 [0.670–0.888], urine: 0.747 [0.565–0.928]). b In the external test set, the AUC value of GDM discriminant model constructed with saliva, serum, and urine was 0.796 (95%CI, 0.695–0.897). Source data were provided as a Source Data file.

The predictive ability of GDM biomarkers for prognostic risk of GDM

The associations between the above 50 GDM biomarkers and adverse outcomes and clinical profiles in GDM are shown in Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 4. This indicates that GDM biomarkers in serum were mainly associated with maternal uric acid levels and fetal head circumference at GW 30-32 and 36-38, as well as the risks of cesarean section and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. GDM biomarkers in saliva were mainly associated with maternal FBG at GW 36-38 and the risk of neonatal hypoglycemia, whereas GDM biomarkers in urine were mainly associated with maternal systolic blood pressure at GW 36-38. Notably, several GDM biomarkers, such as l-glutamine, bisnorbiotin and thiodiacetic acid, were associated with multiple adverse outcomes or clinical profiles. To further explore the predictive utility of GDM biomarkers in the prognosis of GDM, we screened metabolite features and constructed two adverse outcome prediction models (Supplementary Table 2). Both adverse maternal and neonatal outcome prediction models showed good performance, with AUC values of 0.764 (95%CI, 0.579–0.950) and 0.838 (95%CI, 0.696–0.978) in the internal test set (Fig. 6b), as well as 0.726 (95%CI, 0.627-0.826) and 0.792 (95%CI, 0.720–0.863) in the external test set, respectively (Fig. 6c).

a The GDM biomarkers were significantly associated with adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Red and blue squares indicate positive and negative associations, respectively. Pairwise associations were assessed using two-sided t-tests with FDR correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was indicated as *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. LGA, large for gestational age; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit admission; NRDS, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. b The AUC values of the adverse maternal and neonatal outcome prediction models in the internal test set were 0.764 (95%CI, 0.579–0.950) and 0.838 (95%CI, 0.696–0.978), respectively. c The AUC values of the adverse maternal and neonatal outcome prediction models in the external test set were 0.726 (95%CI, 0.627–0.826) and 0.792 (95%CI, 0.720–0.863), respectively. Source data were provided as a Source Data file.

GDM biomarkers altered in the first trimester and associated with the risk of GDM

In this study, we also examined another prospective cohort (cohort 4) to determine whether the above 50 GDM biomarkers were altered in the first trimester in GDM patients. In total, 11 metabolites including one GDM biomarker in saliva, nine in serum, and one in urine were significantly altered as early as the first trimester in GDM (Fig. 7a). We compared the average abundances of these 11 biomarkers in GDM and non-GDM in the first and second trimesters, and found that they showed consistent change trends from the first to second trimester in both groups (Supplementary Fig. 5). Compared to non-GDM, six biomarkers increased in both the first and second trimesters in GDM patients: dimethylethanolamine in saliva; and asymmetric dimethylarginine, lysylglycine, malic acid, tyramine-O-sulfate, uridine in serum (Fig. 7b). Further correlation analysis suggested that the increases in saliva dimethylethanolamine (odds ratio [OR], 2.97, 95% CI, 1.85–4.91), serum asymmetric dimethylarginine (OR, 1.25, 95% CI, 1.00–2.33) and serum tyramine-O-sulfate (OR, 3.58, 95% CI, 1.07–13.05) levels in the first trimester were closely related to the increased risk of GDM in the second trimester (Fig. 7c). In order to better evaluate the utility of these GDM biomarkers in early diagnosis of GDM, an early prediction model for GDM was also constructed using 11 metabolite features in multivariate samples (Supplementary Table 3), with AUC values of 0.767 (95%CI, 0.611–0.923) in the internal test set and 0.744 (95%CI, 0.655–0.822) in the external test set (cohort 5) (Fig. 7d).

a The clustering heat map showed 11 GDM biomarkers with significant differences in the first trimester, including one saliva metabolite, nine serum metabolites, and one urine metabolite. b Analysis of content changes showed that dimethylethanolamine in saliva, and asymmetric dimethylarginine, lysylglycine, malic acid, tyramine-O-sulfate, and uridine in serum were increased in GDM in both the first and second trimesters. Glucosamine 6-phosphate, paracetamol sulfate, pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid, and S-cysteinosuccinic acid in serum, and thiodiacetic acid in urine showed different content changes between GDM and non-GDM in the first and second trimesters. c Forest plot showed correlations between GDM biomarkers in the first trimester and the risk of GDM (GDM group, n = 50 and non-GDM group, n = 50). Blue nodes represented GDM biomarkers in saliva, red nodes represented GDM biomarkers in serum, and yellow nodes represented GDM biomarkers in urine. The ORs were estimated using logistic regression, and 95% CIs were obtained via bootstrap resampling. The height of each bar represented the OR, and the error bars indicated the corresponding 95% CIs. P-values were shown to indicate the statistical significance of each association. d The early prediction model for GDM constructed by first-trimester GDM biomarkers had AUC values of 0.767 (95%CI, 0.611–0.923) in the internal test set and 0.744 (95%CI, 0.655–0.822) in the external test set. Source data were provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In this prospective nested case-control study, we combined the metabolic profiles of multivariate samples (saliva, serum, and urine) acquired by high-throughput mass spectrometry to comprehensively investigate the metabolic characteristics of GDM for the first time. We identified 54 metabolites that were altered in the second trimester in GDM; we found that differential metabolites in saliva, serum, and urine interact with each other and jointly participate in metabolic pathway disruption, ultimately leading to GDM. Based on these observations, 50 second-trimester GDM biomarkers independently associated with abnormal maternal glucose values and insulin resistance in GDM were identified. The combination of GDM biomarkers in multivariate samples could better distinguish GDM patients from non-GDM patients, and could also effectively predict the occurrence of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in GDM. We also found that several GDM biomarkers were altered as early as the first trimester and were closely related to the risk of GDM, which could also be an important tool for early prediction of GDM.

Abnormalities of various metabolites in biological samples are central to the disturbance of metabolic pathways observed in GDM10, offering a better understanding of is pathogenesis. Previous studies have found that amino acid metabolism disorders influence GDM onset by contributing to insulin resistance21. However, some studies have indicated that there might be a bidirectional mechanism between them. Zakaria et al. 22 demonstrated that insulin resistance could lead to an increase in branched-chain amino acids, which activated the mTOR signaling pathway, thereby aggravating insulin resistance and continuous accumulation of branched-chain amino acids. Our study also found significant fluctuations in various amino acids and their derivatives, which were mainly enriched in alanine, aspartate, and glutamate, and cysteine and methionine as well as in the D-amino acid metabolism. Specifically, increased glutamine may indicate that the compensatory mechanism of gluconeogenesis has been activated by insulin resistance. Meanwhile, changes in sulfur-containing amino acids and in D-amino acids influence insulin secretion regulation23, further affecting insulin sensitivity. This is evidence of the bidirectional mechanism between amino acid metabolism and insulin resistance. Furthermore, we also observed significant disruptions in several key metabolites of the tricarboxylic acid cycle: oxaloacetic acid and pimelic acid levels in saliva decreased, while malic acid level in serum increased, implying a blockage in mitochondrial energy metabolism, which can lead to insulin resistance7. Oxidative stress is also considered closely related to insulin resistance in GDM, but further evidence at the metabolic level is still needed24. The significant decrease in serum homocysteine and urine pyridoxamine was detected in our study could result in cells being exposed to a more intense oxidative stress environment and impair the body’s antioxidant reserves25. Thus, we speculate that disruption of mitochondrial energy metabolism, downstream metabolic network imbalance, and impaired antioxidant defense mechanisms may jointly drive the development of insulin resistance in GDM. In addition, we found associations among l-glutamine, bisnorbiotin, xanthine and other differential metabolites in multivariate samples; they jointly play important roles in the disordered metabolism within GDM. Our study revealed both similarities and heterogeneity in metabolic information in different biofluid samples. Similarity may result from abnormally expressed metabolites in tissues circulating through blood into other biofluid samples. Notably, oral microorganisms may significantly alter salivary metabolite profiles through their role in disease pathogenesis26, while renal impairment can disrupt urinary metabolic profiles27. Overall, our study supplements and expands the current understanding of the pathogenesis of GDM at the level of multivariate samples and metabolites. However, further experiments are needed to elucidate the potential metabolic mechanisms involved and their causal relationships.

The diagnostic gold standard for GDM is OGTT performed at GW 24-28, which is also an external manifestation of the abnormal glucose metabolism in GDM. Insulin resistance is widely recognized as an important pathogenic mechanism in GDM. Therefore, as GDM biomarkers, we identified differential metabolites related to OGTT values and HOMA-IR. Intriguingly, we found that most GDM biomarkers were associated with abnormal post-loading glucose, whereas only a few were associated with FBG. This distinction may be explained by differences in pathogenesis. A high FBG is thought to be associated with hepatic insulin resistance and early reduced insulin secretion, whereas pregnant women with high post-loading glucose are more likely to have muscle insulin resistance and more severe pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in GDM28,29. Several GDM biomarkers, such as asymmetric dimethylarginine, lysylglycine, and tyramine-O-sulfate, were simultaneously correlated with FBG, 1h-BG, and 2h-BG. It was notable that these GDM biomarkers were also found in the first-trimester serum, and were therefore highly likely to be key factors in the pathogenesis of GDM. Based on these GDM biomarkers, we developed the discriminant models for GDM with AUC values of 0.868 in the internal test set and 0.796 in the real-world cohort, demonstrating relatively high diagnostic efficacy. Since OGTT in pregnant women is time-consuming and can cause adverse events such as nausea and stress30, our models could improve patients’ comfort and convenience. At the same time, more metabolic information can be obtained from the multivariate samples to better distinguish between GDM and non-GDM, in both our study and previous reports. Serum metabolites can distinguish GDM with an AUC value of 0.7731, while the model based on gut microbiota has an AUC value of 0.8432. Wang X et al. reported a combinatorial marker panel with urine and fecal metabolites that could identify GDM with higher accuracy than separate metabolic biomarkers11. More interestingly, the efficiency of our model based on the metabolomics of noninvasive samples (saliva and urine) was higher than that of one based on a single invasive sample (serum), although the addition of serum further enhanced the model performance. This implies the possibility of a shift towards using non-invasive samples for GDM diagnosis in the future, although validation of our approach in larger cohorts and more advanced model-building methods are necessary.

Metabolic characteristics may not only affect the physiological state during pregnancy but also have a profound impact on pregnancy outcomes in GDM. We found that GDM biomarkers in saliva, serum, and urine from GW 24-28 were correlated with clinical characteristics, including blood glucose and fetal growth in the third trimester, as well as the occurrence of adverse outcomes, such as cesarean section, neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and neonatal hypoglycemia. Previous studies have also shown that maternal metabolites may be potential biomarkers for predicting adverse outcomes in GDM patients33,34, as our study confirms. We utilized GDM biomarkers from multivariate samples to construct the models that effectively predict the occurrence of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. The predictive efficacy of these models was also verified in a real-world cohort, which was not previously achieved. Our results suggest that GDM biomarkers can help to explain the relationships of GDM and its complications. A novel combination of metabolic biomarkers may be a promising alternative method that can not only be used to diagnose or screen pregnant women at high risk of GDM but also serve as a reliable tool for predicting the prognosis of GDM. Early intervention could improve the health of GDM mothers and their infants at the source. Of course, further large-scale and prospective cohort studies incorporating more maternal and neonatal outcomes are warranted to clarify the causal relationship between these metabolic alterations and adverse outcomes.

GDM does not occur or progress suddenly. The disturbed metabolism and abnormal clinical manifestations may occur before the clinical diagnosis35,36. In our study, we validated 11 GDM biomarkers that also differed between the GDM and non-GDM groups in the first trimester. These GDM biomarkers showed consistent trends before and after a clinical diagnosis of GDM; some showed greater changes in amplitude during the second trimester than during the first trimester, suggesting the appearance of a metabolic disorder as early as the first trimester. As is known to all, GDM typically clinically diagnosed during middle or late pregnancy, by which time these metabolic disorders have already damaged the body; it is therefore necessary to screen for and diagnose GDM as early as possible. Thus, we performed correlation analysis to identify GDM biomarkers that could facilitate early diagnosis of GDM, and discovered for the first time that a high level of saliva dimethylethanolamine in the first trimester was associated with an increased risk of GDM. Besides, multiple metabolites in serum in the first trimester can also be used for early GDM screening37,38, consistent with our findings. We found that asymmetric dimethylarginine and tyramine-O-sulfate in serum in the first trimester were positively associated with GDM. It was reported that pregnant women with GDM had elevated asymmetric dimethylarginine levels39, which were closely related to glucose tolerance deterioration40 and endothelial dysfunction41. Detection of these GDM biomarkers in first-trimester pregnant women could be used to predict the occurrence of GDM to some extent. The early prediction model for GDM constructed using these first-trimester GDM biomarkers also confirmed this potential. However, the performance of the early prediction model was inferior to that of the GDM discriminant model using second-trimester GDM biomarkers. Since metabolomics reflects biological activities that are currently occurring or have already occurred9, some metabolic biomarkers may be involved in the pathogenesis of GDM only in the first trimester. This was not fully explored in our study and requires further investigation in subsequent studies. In addition, the AUC values of our predictive models constructed using metabolomics were similar to that of the traditional clinical risk factors42,43, especially in the real-world cohort. Taking into account affordability and convenience, the current clinical application values of these metabolic biomarkers may not be superior to clinical factors. In the future, we plan to utilize metabolomics in early pregnancy to provide more comprehensive information on metabolism in GDM, which will also advance the diagnostic window and allow early diagnosis and intervention.

This study had several unique advantages, including its large sample prospective design, inclusion of real-world cohorts for external testing, application of NALDI-TOF-MS, first identification of GDM biomarkers from saliva, and comprehensive exploration of the roles of GDM biomarkers from multivariate samples in the diagnosis and prognostic assessment of GDM. However, the study still had some limitations. First, all three samples were not always collected from the same participants (e.g., cohort 1), but we validated differential metabolites and performed subsequent analyses in all three-sample cohorts (cohort 2–5) to minimize confounding bias. In addition, samples should ideally be collected longitudinally from the same participants, from the first trimester to the second trimester, which will be possible in our future studies. Second, this was a single-center study conducted in a hospital. However, this center is the leading obstetrics and gynecology hospital in China, and it accepts pregnant women from all of Zhejiang Province and elsewhere in China, so the population is representative. Of course, deficiencies in racial/ethnic diversity are still unavoidable, and future multicenter studies in different countries are required to better explore the metabolic characteristics of GDM. Third, although we adjusted for some clinical factors, such as whether pregnant women with GDM had received any intervention, and whether their blood glucose levels were well-controlled, there were still some unknown factors. Future studies can conduct detailed subgroup analyses, such as GDM subtypes (A1 vs A2) and BMI stratification, which will be of clinical relevance and generalization. Furthermore, postpartum follow-up can also provide us with more comprehensive information. Finally, this study could not demonstrate causal relationships between GDM biomarkers and GDM and its adverse outcomes; further animal or cell experiments are needed to explore how GDM biomarkers affect the onset of GDM and its complications.

In conclusion, metabolomics analyses in saliva, serum, and urine samples were performed for the first time to explore the metabolic characteristics of GDM from multiple perspectives and to identify new metabolic biomarkers. These GDM biomarkers revealed possible mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of GDM; they also have the potential to predict the risk and prognosis of GDM. Although they have not shown significant superiority over those straightforward and affordable methods in clinical application, our findings provide a new research direction for understanding the pathogenesis of GDM, as well as early diagnosis and prediction of prognosis, which are important for efforts to improve health in mothers with GDM and their infants.

Methods

Study design and population

This prospective nested case-control study was derived from the ongoing observational study “Clinical Study of a New Technology System for Early Diagnosis and Screening of GDM Based on Multiomics” (NCT05386927). The study population consisted of pregnant women treated at the Women’s Hospital School of Medicine Zhejiang University according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria: (1) maternal age was 20-49 years; (2) singleton pregnancy; (3) complete clinical data; (4) OGTT was completed at GW 24-28; (5) any biofluid samples of saliva, serum, or urine were collected as required; (6) routine prenatal examinations and gave birth in our hospital; (7) excluded women with diseases that affect metabolic function or even threaten the life of the mother and fetus before pregnancy, such as diabetes, heart disease, liver and kidney disease, etc; 8) excluded fetuses with a known deformity or genetic defect. The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (IRB-20210293-R) and China’s Ministry of Science and Technology (2022SQCJ4524), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The second-trimester cohort included 1241 pregnant women, whose biofluid samples (saliva, serum or urine) were collected on the same day as the 75 g OGTT during GW 24-28. They were divided into GDM and non-GDM groups according to results of OGTT, with FBG, 1h-BG, and 2h-BG levels of 5.1, 10.0, and 8.5 mmol/L, respectively44. After excluding unqualified biofluid samples, 173 GDM and 821 non-GDM patients with 1-2 biofluid samples, and 50 GDM and 197 non-GDM patients with all three biofluid samples were included. With 1:1 matching for maternal age, BMI, and GW at sample collection, the saliva, serum, and urine sets (cohort 1) consisted of equal numbers of GDM and non-GDM patients, with 104, 116, and 58, respectively, were performed to screen for differential metabolites. And the cohort 2 consisted of 50 each GDM and non-GDM patients, with saliva, serum, and urine samples, were established to verify and analyze differential metabolites, identify GDM biomarkers and determine their diagnostic and prognostic ability. In addition, we conducted a real-world cohort of 143 pregnant women in the second trimester, with all three biofluid samples used as an external test set (cohort 3). These patients were examined at baseline, followed until delivery, and their clinical data and adverse outcomes were collected.

We also recruited 425 pregnant women in the first trimester whose biofluid samples were collected during GW 9-13; these women were followed until the OGTT. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and methods used for sample collection and matching were the same as those for the second-trimester cohort. Accordingly, the cohort 4 consisted of 50 each GDM and non-GDM patients with first-trimester saliva, serum, and urine samples, were performed to investigate first-trimester changes in GDM biomarkers and their potential for early diagnosis. Another 167 pregnant women in the first trimester, with all three biofluid samples were also included in cohort 5 as an external test set to evaluate the real-world model performance.

Sample collection

Biofluid samples were collected on the same day as the OGTT during GW 24-28 or in the first trimester at GW 9-13. Saliva was collected as previously described17. Briefly, saliva was collected between 7:30 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. using a specific device called SalivaGetinTM after an overnight fast. Prior to collection, volunteers rinsed their mouths with purified water and waited for 5 minutes to minimize residual water. Unstimulated saliva (~0.5 mL) was then collected by passive drooling into a SalivaGetinTM device. The sample was then passed through the device’s integrated dual-layer membrane to remove oral debris and bacteria, and subsequently stored at -80 °C in a sterile tube. Saliva mixed with gingival bleeding or other conditions were excluded (normal samples should be transparent and clear). Serum samples were collected from participants following an overnight fast between 7:30 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. Blood was drawn from the arm vein into vacuum tubes and allowed to clot at room temperature for 30–60 minutes. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes to separate the serum. The clear supernatant was carefully harvested, and the cellular precipitate was discarded. All processed serum samples were immediately frozen and stored at -80 °C until further metabolomic analysis. Serum showing hemolysis was excluded. The midstream of first-morning urine was collected by the pregnant women themselves in the morning using sterile containers. Immediately after collection, the samples were transported on ice to the laboratory. Upon arrival, they were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C to remove cellular debris. The resulting supernatant was then transferred to a new polypropylene tube and stored at −80 °C until use. Urine showing redness was excluded.

Clinical data collection

Pregnant women in the second-trimester cohort underwent a baseline examination at enrollment; clinical data were collected, including maternal age, gravidity, parity, education, family history of diabetes, OGTT values, HbA1c, and fasting insulin levels. HOMA-IR was calculated by fasting insulin (μU/dL) × fasting blood glucose (mmol/L)/22.5. These women were followed; blood pressure (systolic and diastolic), blood glucose (fasting blood glucose and HbA1c), blood lipids (total cholesterol, triglyceride, and high- and low-density lipoprotein), liver function (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase), kidney function (creatinine, urea, and uric acid), and other clinical indicators were determined at GW 30-32 and GW 36-38. These indicators were tested in the hospital’s biochemical laboratory according to clinical requirements. Ultrasound data pertaining to fetal growth at GW 30-32 and GW 36-38 were also collected, including biparietal diameter, femur length, head circumference, and abdominal circumference, all of which were measured by senior physicians in the ultrasound department. We also collected data on adverse maternal outcomes (pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia, premature rupture of membranes, fetal distress, cesarean section, premature birth) and neonatal outcomes (large for gestational age, admission to neonatal intensive care unit, neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal septicemia, neonatal hypoglycemia, neonatal intracranial hemorrhage) as judged by obstetricians and neonatologists. In addition, blood glucose levels (both fasting and post-meal) during hospitalization were collected to valuate glucose control for GDM, as well as drug intervention (including insulin and metformin) and gestational weight gain.

Sample metabolite extraction

Saliva

The salivary metabolome was extracted using a protein precipitation (PPT) method. An aliquot of 40 μL of acetonitrile/methanol (1:1) solution was first added to 20 μL of saliva sample, thawing on ice, and the mixture was shaken at 1500 rpm for 5 min and centrifuged at 8045 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh centrifuge tube, and 5 μL of ultrapure water was added. Then, 0.8 μL of the mixture was deposited onto the Met-Si Array® chip (Well Healthcare Technologies Co., Ltd) via the liquid handing platform (ASSIST PLUS, INTEGRA, Switzerland). Samples were subsequently dried for 30–40 min under the controlled humidity of 40–50% for further MS detection.

Serum

The serum metabolome was extracted using a sequential protocol involving PPT followed by liquid-liquid extraction method. Serum samples were thawed on ice, and 20 μL of serum sample was mixed with 80 μL of acetonitrile/methanol (1:1) solution. The mixture was shaken at 1500 rpm for 5 min and centrifuged at 8045 × g for 10 min. Then, 15 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a fresh centrifuge tube for subsequent extraction and regarded as solution A. Subsequently, 50 μL of ultrapure water was added to the remaining mixture, sonicated for 10 s, and then shaken (1500 rpm, 5 min) and centrifuged (8045 × g, 10 min) after the addition of 150 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether solution to divide the mixture into upper and lower layers. Then, 50 μL of the upper solution was removed and dried under a stream of nitrogen gas to obtain a dry powder, which was then resuspended by adding 10 μL of IPA/H2O (1:1) solution and vortex mixed for 15 s. Subsequently, 5 μL of the resuspended solution was mixed with 5 μL of solution A and shaken at 1500 rpm for 5 min. Then, 0.8 μL of the mixture was deposited onto the Met-Si Array® chip by the automatic liquid handing platform and dried for 30-40 min under the controlled humidity of 40–50% for further MS detection.

Urine

The urinary metabolome was extracted using a tip-contact extraction method without the use of organic solvents18. After thawing on ice, a 20-μL aliquot of urine was dropped onto the ITO glass. Then, the nanostructured surface of a 4 mm × 4 mm FEP@VSiNWs chip was brought into contact with the surface of the solution and maintained for 20 min to extract the metabolites. After extraction, the residual urine droplet was further removed under a stream of nitrogen gas. The obtained chips were preserved in a desiccator for further MS detection.

Metabolite detection and identification by NALDI-TOF-MS

In this study, metabolomic detection and analysis were performed on saliva, serum and urine samples. QC samples of saliva, serum and urine were prepared by pooling equal volumes from 50 individual samples. Blank controls were ultrapure water samples which have passed through the sample pretreatment process in the same way as a biological sample but with no biological sample included. Metabolites from individual saliva, serum, and urine samples as well as QC and blank samples were extracted and deposited onto the Met-Si Array® chip45 (Well Healthcare Technologies Co., Ltd, China) and FEP@VSiNWs chip46, which were placed onto custom-made plates and inserted into a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Autoflex Max, Bruker Daltonics, USA) for metabolite profiling. Autoflex Max mass spectrometer was equipped with a 355-nm Nd:YAG laser (pulse energy < 500 μJ, pulse width 3 ns). The diameter of the laser spot was set to 80–100 μm. The relative laser energy was set to 55%–63% of the maximum energy. The ions produced by a 100-ns pulse ion extraction were subjected to an electric field of 19.18 kV (ion source 1) and 16.92 kV (ion source 2), and analyzed in reflective negative mode. The generated spectra were obtained after 1250 laser shots of the spot over the mass range of 50–400 Da, following MS calibration. Metabolic profiling of cohort samples was carried out in an automatic batch mode. MS/MS fragmentation of salivary features was performed using the LIFT mode. Each analytical batch comprised 96 samples, including 88 individual samples, 4 QC samples, and 4 blank controls. All individual samples were prepared without technical replicates (n = 1) and analyzed following a randomized order.

Metabolite characteristic fragmentation information was acquired by mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) values of primary MS spectra and fragment ions of MS/MS spectra by the Autoflex Max MS spectrometer. The data were used to search the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB, http://www.hmdb.ca/) for matching features to identify metabolite molecules. The relative error of the primary mass spectrometry m/z values was set to 50 ppm. Annotation of metabolites was restricted exclusively to the [M-H]⁻ and [M-H₂O-H]⁻ adduct ions.

Data analysis

The metabolomics raw data were first exported as ASCII data in the flexanalysis software (ver. 3.4, Bruker Daltonics Inc.). Then they were processed using a custom-developed software called as HJ Cloud® (Well-healthcare Technologies Co., Ltd, HangZhou, China, Software Copyright Registration No. 2022SR1403956). The processing steps included smoothing, baseline correction, intensity normalization, alignment, peak detection, and peak binning. The total ion current method was applied for the intensity normalization. A total of 1667 peaks with S/N > 6, which was expressed in over 80% of the samples was selected. After peak annotation using HMDB database, the molecular matrix including the normalized intensities of each metabolite was subjected to all statistical analyses with R software (http://www.R-project.org, ver. 4.3.1) unless otherwise noted. Continuous and categorical variables were compared using the t-test and chi-square analyses as appropriate. The cubic spline method was used for data normalization; log transformation and min-max scaling were implemented for data standardization. To evaluate the differences between groups, principal component analysis and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis were performed using the stats and ropls packages. Differential metabolites were sorted using the Mann-Whitney U test and false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Correlation analysis was based on Spearman’s correlation analysis. Linear regression models were constructed with the lme4 package to address covariate influences, including family history of diabetes, HbA1c, drug intervention, glucose control, and gestational weight gain, in the correlation analysis between GDM biomarkers and adverse outcomes. LightGBM algorithm and weighted voting ensemble approach were performed to construct GDM discriminant models, adverse outcome prediction models and early prediction model for GDM, which were tuned and optimized by five-fold cross-validation in the training set (70%). Feature selection was performed based on LightGBM’s built-in feature importance scores, which quantify the contribution of each variable to model prediction. To retain the most clinically relevant predictors, features with importance scores below a predefined threshold were excluded. The performance was analyzed in the internal test set (30%) and the cohort 3 or cohort 5 external test sets based on the AUC. Hierarchical clustering analysis and visualization were conducted using the pheatmap package. ORs and CIs were calculated using the stats package. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis was performed using the cluster Profiler package. Metabolic pathways were analyzed on the KEGG and MetaboAnalyst website. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The metabolomics datasets generated in this study have been deposited in the Metabolomics Workbench database under accession code ST004139, ST004140, ST004141. Processed data matrices and metadata are provided in the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper. Raw MALDI-TOF/MS files (including mzML formats) can be accessed upon request to the Metabolomics Workbench Data Access Committee. Prospective users must: (1) register for a Metabolomics Workbench account and agree to its data-use policies; (2) submit a brief research proposal outlining aims and required datasets; (3) obtain any necessary ethics or institutional approvals for secondary use of human data; (4) agree to sign a Data Use Agreement specifying confidentiality and proper citation of the data; and (5) perform all analyses within the Metabolomics Workbench cloud environment or a local secure computing environment approved by the Data Access Committee. For more information: https://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The analysis and modeling in this paper used R v.4.4.0 and the tidyverse v.1.3.2, caret 6.0-94, glmnet 4.1-8, ggplot2 v.3.5.1, lightgbm v.4.5.0, magrittr v.2.0.3, pROC v.1.18.5, stats 4.4.0 R packages, all of which are freely available. Code [https://zenodo.org/records/17438713?token=eyJhbGciOiJIUzUxMiJ9.eyJpZCI6Ijk2YzZiNWMzLTdjYmEtNGZiZS1hMTY0LWE0OTU4MWQ5YmNkOCIsImRhdGEiOnt9LCJyYW5kb20iOiI4NmFjNDAyM2NmOTY1OTgyZTIzNDM4MTc4NzgwM2Y2ZCJ9.oUr2KzPHxU-yhvqOOimXr68aBtWzW5RPkVs0qiuJpOICuMpZO9rV1unPN1XWoT2qWkAvMx0ufE2Sjv6jPlFytw].

References

McIntyre, H. D. et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 5, 47 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Estimation of global and regional gestational diabetes mellitus prevalence for 2021 by International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group’s Criteria. Diab. Res. Clin. Pract. 183, 109050 (2022).

Catalano, P. M. et al. The hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome study: associations of GDM and obesity with pregnancy outcomes. Diab. Care 35, 780–786 (2012).

Farrar, D. et al. Hyperglycaemia and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clin. Res. ed.) 354, i4694 (2016).

Daly, B. et al. Increased risk of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus, a target group in general practice for preventive interventions: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 15, e1002488 (2018).

Bentley-Lewis, R. et al. Metabolomic profiling in the prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 58, 1329–1332 (2015).

Sergi, D. et al. Mitochondrial (Dys)function and insulin resistance: from pathophysiological molecular mechanisms to the impact of diet. Front. Physiol. 10, 532 (2019).

Sun, C. et al. The impact of environmental and dietary exposure on gestational diabetes mellitus: a comprehensive review emphasizing the role of oxidative stress. Front. Endocrinol. 16, 1393883 (2025).

Wang, Q. Y., You, L. H., Xiang, L. L., Zhu, Y. T. & Zeng, Y. Current progress in metabolomics of gestational diabetes mellitus. World J. Diab. 12, 1164–1186 (2021).

Alesi S., Ghelani D., Rassie K., Mousa A. Metabolomic Biomarkers in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Altered gut bacterial and metabolic signatures and their interaction in gestational diabetes mellitus. Gut Microbes 12, 1–13 (2020).

Tian, M. et al. Serum metabolites as an indicator of developing gestational diabetes mellitus later in the pregnancy: a prospective cohort of a Chinese Population. J. Diab. Res. 2021, 8885954 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus-associated changes in the breast milk metabolome alters the neonatal growth trajectory. Clin. Nutr. 40, 4043–4054 (2021).

Zhang, C. Z. et al. Saliva in the diagnosis of diseases. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 8, 133–137 (2016).

Bessonneau, V., Pawliszyn, J. & Rappaport, S. M. The saliva exposome for monitoring of individuals’ health trajectories. Environ. Health Perspect. 125, 077014 (2017).

de Oliveira, L. R. et al. Salivary metabolite fingerprint of Type 1 Diabetes in young children. J. Proteome Res. 15, 2491–2499 (2016).

Jiang, X. et al. Perfluorinated polymer modified vertical silicon nanowires as ultra low noise laser desorption ionization substrate for salivary metabolites profiling. Talanta 225, 122022 (2021).

Jiang, X. et al. Ultrasensitive and high reproducible detection of urinary metabolites using the tip-contact extraction method coupled with negative LDI-MS. J. Proteome Res. 20, 4022–4030 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Hepatocarcinoma discrimination by ratiometric lipid profiles using tip-contact sampling/ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 91, 10376–10380 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Untargeted metabolomics of saliva in pregnant women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus and healthy non-pregnant women. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1206462 (2023).

Zhou, Q. et al. Phenylalanine impairs insulin signaling and inhibits glucose uptake through modification of IRβ. Nat. Commun. 13, 4291 (2022).

Zakaria N. F., Hamid M., Khayat M. E. Amino acid-induced impairment of insulin signaling and involvement of G-protein coupling receptor. Nutrients 13, (2021).

Roychaudhuri, R. et al. Mammalian D-Cysteine controls insulin secretion in the pancreas. Mol. Metab. 90, 102043 (2024).

Saucedo R. et al. Role of oxidative stress and inflammation in gestational diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants 12, (2023).

Ramis R. et al. How does Pyridoxamine inhibit the formation of advanced glycation end products? The role of its primary antioxidant activity. Antioxidants 8, (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. Alterations in the salivary microbiome and metabolism in patients with carotid atherosclerosis from rural Northeast China. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e034014 (2024).

Sharma K. et al. Endogenous adenine mediates kidney injury in diabetic models and predicts diabetic kidney disease in patients. J. Clin. Investig. 133, (2023).

Chow, E. Y. K. & Chan, J. C. N. Insulin resistance versus β-cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: where public and personalised health meet. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 8, 92–93 (2020).

Wu, Q. et al. The heterogeneous associations between gestational weight gain and adverse pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes mellitus according to abnormal glucose metabolism. Nutr. Diab. 13, 10 (2023).

Gayet-Ageron, A. et al. Specific information about the WHO guidelines for gestational diabetes screening improves clinical practices. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 14, 36–42 (2008).

McBride, N. et al. Do nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based metabolomics improve the prediction of pregnancy-related disorders? Findings from a UK birth cohort with independent validation. BMC Med. 18, 366 (2020).

Ye, D. et al. Integrative metagenomic and metabolomic analyses reveal gut microbiota-derived multiple hits connected to development of gestational diabetes mellitus in humans. Gut Microbes 15, 2154552 (2023).

Diboun, I. et al. Metabolic profiling of pre-gestational and gestational diabetes mellitus identifies novel predictors of pre-term delivery. J. Transl. Med. 18, 366 (2020).

Luo, M. et al. The mediating role of maternal metabolites between lipids and adverse pregnancy outcomes of gestational diabetes mellitus. Front. Med. 9, 925602 (2022).

Xie, J., Li, L. & Xing, H. Metabolomics in gestational diabetes mellitus: A review. Clin. Chim. Acta; Int. J. Clin. Chem. 539, 134–143 (2023).

Sovio, U., Murphy, H. R. & Smith, G. C. Accelerated fetal growth prior to diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study of nulliparous women. Diab. Care 39, 982–987 (2016).

Zhu, Y. et al. Predictive metabolomic markers in early to mid-pregnancy for gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective test and validation study. Diabetes 71, 1807–1817 (2022).

Borges Manna, L. et al. First-trimester nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomic profiling increases the prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 233, 71.e71–71.e14 (2025).

Tiong, P., Kosmider, L., Lassi, Z. S., Arstall, M. A. & Andraweera, P. H. Asymmetric dimethylarginine and gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 80, 283–291 (2023).

Mittermayer, F. et al. Elevated concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine are associated with deterioration of glucose tolerance in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Intern. Med. 261, 392–398 (2007).

Poniedziałek-Czajkowska, E., Mierzyński, R., Szymula, D., Leszczyńska-Gorzelak, B. & Oleszczuk, J. Intercellular Adhesion Molecule and Endogenous NOS Inhibitor: Asymmetric Dimethylarginine in Pregnant Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diab. Res. 2016, 1342643 (2016).

Mustaniemi, S. et al. Serum ceramides in early pregnancy as predictors of gestational diabetes. Sci. Rep. 13, 13274 (2023).

Niu, Z. R., Bai, L. W. & Lu, Q. Establishment of gestational diabetes risk prediction model and clinical verification. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 47, 1281–1287 (2024).

Metzger, B. E. et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diab. Care 33, 676–682 (2010).

Lin, S. et al. Rapid and noninvasive early detection of lung cancer by integration of machine learning and salivary metabolic fingerprints using MS LOC platform: a large-scale multicenter study. Adv. Sci. 12, e2416719 (2025).

Jiang, X. et al. Integration of metabolomics and peptidomics reveals distinct molecular landscape of human diabetic kidney disease. Theranostics 13, 3188–3203 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Hongliang Ge from Hangzhou Medthinking Technology Co., Ltd for technical guidance. This work is supported by the Key R&D Program of Zhejiang Province under Grant 2022C03058 (L.Z.X.), Medical and Health Technology Program of Zhejiang Province under Grant WKJ-ZJ-2324 (L.Z.X.), 4 + X Clinical Research of Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University under Grant ZDFY2022-4XB101 (L.Z.X.), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant ZCLQN25H0402 (W.Q.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Q., W.Y.H., Z.S.Q., T.Y.B., Z.L.X., T.J.Y., C.Q., H.L.Y., Z.P.Y., F.X.L., C.J.H., C.S., C.D.Q., and L.Z.X. were involved in the conception, design, and conduct of the study and the analysis and interpretation of the results. W.Q. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors edited, reviewed, and approved the final version of the manuscript. L.Z.X. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Fabio Facchinetti and Elina Keikkala for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Q., Wu, Y., Zhu, S. et al. Metabolomics of saliva, serum, and urine for pathogenesis, diagnosis, and prognosis in gestational diabetes mellitus. Nat Commun 16, 11070 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65992-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65992-6