Abstract

Activating the lattice oxygen of catalysts can accelerate the oxygen evolution reaction. However, a fundamental understanding of the lattice oxygen dynamics remains insufficient, which ultimately impairs catalyst development. Herein, we show that a CO32--containing electrolyte can substantially alter the reactivity and redox stability of lattice oxygens. In particular, for CoOOH and NiCoOOH, which feature high lattice oxygen reactivity, higher degrees of CO32- intercalation deactivate lattice oxygen, shifting the reaction pathway from the lattice oxygen mechanism to the adsorbate evolution mechanism. Operando spectroscopic and spectrometric analyses coupled with 18O isotopic labeling corroborate the decreased metal‒oxygen bond covalency and hindered lattice oxygen release caused by the intercalation of CO32-. Importantly, the catalysts with a fine-tuned degree of CO32- intercalation maintain high activity and stability owing to the dynamic equilibrium between lattice oxygen release and refilling, demonstrating negligible degradation in an alkaline water electrolyzer after 5000 h of operation at 0.5 A cm-2. This work reveals the intricacy of lattice oxygen dynamics, offering opportunities for designing high-performance electrocatalysts for real-life applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrochemical reactions are essential for the storage and conversion of renewable energy. The anodic oxygen evolution half-reaction (OER), which plays a pivotal role in various scenarios, including green hydrogen production, CO2 electrolysis, nitrogen fixation and electrosynthesis, is particularly important1,2,3,4. However, this four-proton/electron transfer process is intrinsically sluggish, which often causes high overpotential loss and impairs the energy efficiency of the device5,6,7. In many cases, a series of substeps involving multiple O-containing intermediates must take place consecutively on the catalyst surface to enable the generation of diatomic oxygen8,9. The activity of catalysts following such an adsorbate evolution mechanism (AEM) is heavily limited by the scaling relationship. Theoretically, the minimum overpotential (η) is ~370 mV when the binding energies of all intermediates are ideal10,11. This thermodynamic constraint can be overcome when other reaction pathways are developed. For example, in the lattice oxygen-mediated mechanism (LOM), where the lattice oxygens (LOs) of catalysts participate in redox chemistry, higher intrinsic OER activity (η«370 mV) is experimentally observed and well explained12,13,14. These advancements in mechanistic understanding offer compelling guidelines for the design and development of better OER catalysts.

Although high metal‒oxygen bond covalency and strong hybridization of oxygen nonbonding states are believed to be descriptors of catalysts that activate the OER via LOM15,16,17, the mechanistic understanding of the dynamic behavior of LOs remains inadequate. For example, rapid LO exchange during the OER often creates an amorphous catalytic surface through reconstruction, which might be heavily affected by, in addition to the intrinsic physicochemical properties of catalysts, many extrinsic factors, such as the potential bias, pH value and ions in the electrolyte8,18,19,20. In fact, intercalated species such as PO43- and SeO42- have been reported to activate the lattice oxygen of oxyhydroxide OER catalysts21,22. This ill-defined scenario makes the establishment of a structure‒LO reactivity relationship rather challenging. Discrepancies in the reaction pathways of various metal oxide and hydroxide (e.g., Co3O4 and NiFe hydroxide) OER catalysts are thus noted in the literature15,23,24,25. Another common challenge is associated with understanding the LO release and refilling processes during LO exchange. The governing factors that manipulate the rates of these substeps remain ambiguous. In many cases, the much faster LO release rate leads to the generation of a substantial number of oxygen defects and the sequential dissolution of adjacent metal cations, eventually causing the collapse of the crystal structure during catalysis26,27,28. Hence, state-of-the-art catalysts featuring LOM often suffer from rapid performance deterioration within 100 h, which is too far from industrial applications27,29. Approaches such as weakening the metal‒O bond covalency by doping can indeed deactivate lattice oxygens; however, the reaction pathway is then transformed to an AEM with inherently greater polarization loss. The doping element might also dilute the active site on the surface30,31,32. Finding catalysts with ideal lattice oxygen reactivity and stability remains an uneasy task.

In this work, we show that carbonate ions, which are common anions in electrolytes, can greatly manipulate the reactivity and redox stability of LOs during the OER in classic oxyhydroxide catalysts comprising NiOOH, NiCoOOH and CoOOH. The distinct effects of adsorbed and intercalated CO32- species are elucidated via customized electrochemical looping experiments. The dynamic behavior and mechanism of LOs in response to interfacial CO32- are revealed by various ex situ and operando spectroscopic and spectrometric analyses coupled with 18O-isotopic labeling. This fundamental understanding enables the rational manipulation of LO stability via CO32- intercalation, achieving a dynamic equilibrium between LO release and refilling. The application of the fine-tuned OER catalyst in an alkaline water electrolyzer is also discussed.

Results

Distinct responses to carbonate ions

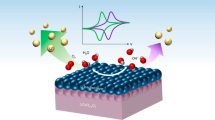

The possible interactions between oxyhydroxide OER catalysts and carbonate ions in the electrolyte are depicted in Fig. 1a, which might include, among others, the chemisorption of CO32- on the surface and the intercalation of CO32- into the interlayer spacing of the catalyst33,34. To probe this interfacial phenomenon, we selected three classic oxyhydroxide catalysts comprising NiOOH, CoOOH and NiCoOOH and designed a “CO32--looping” experiment (denoted as CL), where linear sweep voltammograms (LSVs) were sequentially recorded in 0.1 M KOH with a stepwise increase in the CO32- concentration (0 M, 0.01 M, 0.05 M, 0.1 M, 0.2 M and 0.4 M, denoted as the “forward scan”) followed by a stepwise decrease back to 0 M (denoted as the “backward scan”; see Fig. S1 for the voltammograms with/without iR correction and the experimental details in the SI). Figure 1b shows the relationship between the CO32- concentration (Ccarb) and the OER overpotential at 10 mA cm-2 (η10). For NiCoOOH and CoOOH, essentially identical η10 values are maintained in both the forward and back scans, yet a higher Ccarb leads to a slight increase in η10. Conversely, the η10 of NiOOH clearly negatively correlates with Ccarb, which decreases rapidly in the region with a low Ccarb and then slowly stabilizes when Ccarb reaches 0.2 M. The maximum change in η10 (Δηm), which quantitatively shows the maximum impact on OER activity caused by the looping test, reaches 133 mV, suggesting that the introduction of CO32- can substantially boost the OER activity. Interestingly, a hysteresis loop is observed in all plots, as η10 cannot be fully resumed at the designated Ccarb in the backward scan. This results in the change in η10 in 0.1 M KOH measured before and after the looping test (Δηl). Thus, Δηl can quantitatively reflect the electrochemical performance reversibility during the looping test.

a Schematic illustration showing the wide application of carbonate-containing electrolytes in renewable energy conversion and storage and the possible interaction of carbonate cations with the classic oxyhydroxide anode; η10 (the overpotential at 10 mA cm−2) of classic oxyhydroxide OER catalysts in b “CO32--looping” and c and “CO32--CV-looping” tests in 0.1 M KOH solutions with varying CO32- concentrations. All measurements were conducted at 25 °C with a scan rate of 5 mV s−1. The error bars represent the standard deviations from six independent experiments.

To examine whether the lagging effect is caused by interfacial nonequilibrium, we performed a modified looping experiment, named “CO32--CV-looping” (denoted as CCL, see Fig. S2 for the voltammograms with/without iR correction and the experimental details in the SI), where 100 cycles of cyclic voltammetry (CVs, 0.85 ~ 1.77 V vs. RHE at 10 mV s−1) were performed in each designated electrolyte before recording the LSVs. The new plots in Fig. 1c show substantially altered behaviors of all model catalysts compared with those in the CL test. In the forward scan, Ccarb has a much stronger influence on the η10 values of CoOOH and NiCoOOH, where Δηm exceeds 133 mV and 127 mV, respectively. Its effect on NiOOH activity is similar to that observed in the CL test. In the backward scan, the change in η10 becomes completely irreversible, resulting in prominent hysteresis loops for all catalysts. The value of Δηl is in the range of 118–125 mV. A detailed summary of the key kinetic parameters is included in Table S1. Notably, the current density in all LSVs is normalized to the electrochemical surface area (ECSA), which does not vary significantly during both looping tests, as shown by the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) in Fig. S3.

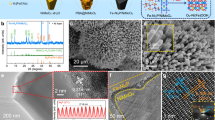

To understand the contrasting catalytic behaviors of oxyhydroxides in CO32--containing electrolytes, we characterized the spent catalysts in detail. According to the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns in Fig. S4, the crystallographic structure after both the CL and CCL tests is sustained in comparison with that of the pristine sample. However, the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) micrographs show expanded d-spacings along the c-direction for the samples after the CCL tests (see Fig. 2a–c and S5). As displayed in Fig. 2d, the average interplanar spacings for pristine CoOOH (003), NiCoOOH (006), and NiOOH (006) are 0.419 nm, 0.360 nm, and 0.340 nm, respectively, which agrees well with the literature20,35. After the CCL test, these d-spacings expand to 0.510 nm, 0.376 nm, and 0.367 nm, respectively. We attributed this change to the intercalation of CO32- into the interlayer spaces. This speculation is further supported by elemental analysis via energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX, see Fig. S6), where the elemental mappings reveal that a carbon-rich shell with a thickness of ~4 nm forms on the surface. In contrast, this carbon shell is not observed in the TEM results of CoOOH after the CL test, reconfirming that CO32- intercalation is unlikely in this scenario (see Fig. S7).

a–c Inverse fast Fourier transform of HRTEM images of CoOOH, NiCoOOH and NiOOH before and after the CCL test; d interplanar distance obtained from HRTEM images; e segments of C 1 s core-level XPS spectra as a function of etching time for CoOOH after the CCL test; operando SEIRAS spectra obtained in (f) 0.1 M KOH + 0.1 M CO32- as a function of potential and (g) 0.1 M KOH + 0.5 mM CO32- as a function of time at a constant potential of 1.32 V vs. RHE.

We then obtained the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) depth profile of the spent catalysts after the CL and CCL tests. Figure 2e shows the segments of C 1 s signals in CoOOH after the CCL test as a function of etching time. The carbonate peak, located at ~289 eV, weakens progressively with increasing depth. It completely disappears at 5200 s, which corresponds to a depth of ~5 nm (see Fig. S1). Conversely, this carbonate peak of CoOOH after the CL test disappears much earlier at 1200 s. This depth corresponds to ~1.1 nm, suggesting the presence of surface-adsorbed carbonate ions (see Figs. S9 and S10). To understand the effect of potential bias on the surface enrichment of CO32-, we carried out operando surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS, see Fig. S11 for experimental details)36. In 0.1 M KOH + 0.1 M CO32-, the peaks at 1500 cm-1 and 1680 cm−1 correspond to the C–O and C=O stretching vibrations of interfacial CO32-, respectively37,38. They intensify gradually as the potential increases from 1.22 to 1.62 V vs. RHE (see Fig. 2f and S12). Such electrosorption is also evident under potentiostatic conditions even at low CO32- concentrations (0.5 mM), as shown in Fig. 2g and S12b. These potential-dependent characteristics are also observed in NiCoOOH and NiOOH, as shown in Fig. S13.

We thus can conclude that the anodic potential bias during the OER accelerates CO32- electrosorption and interfacial intercalations in all oxyhydroxide catalysts. The CL and CCL tests successfully separate the influence of electrosorbed and intercalated CO32- species on the OER activity. As shown by the CL test, the electrosorbed CO32- species play a dominant role in manipulating the catalytic activity of NiOOH by optimizing the electronic structure of the active sites and facilitating proton transfer among the adsorbed intermediates, as documented in the literature34,39. These compounds have negligible effects on the activity of CoOOH or NiCoOOH. A small or no hysteresis loop is recorded, plausibly due to the reversible electrosorption‒deposition of CO32-. In comparison, in the CCL test where CO32- intercalation occurs, a large hysteresis loop is observed since the deintercalation of CO32- takes much time. These intercalated species thus govern the activity deterioration of CoOOH and NiCoOOH. Yet, the effects of these species on the activity of NiOOH, which is superimposed on that of the electrosorbed species, are negligible (see the summary in Table S2). This seems to contradict most findings in the literature, which show that the enlarged interlayer spacings of oxyhydroxide by intercalated CO32- lead to enhanced OER activity due to increased surface area and/or accelerated mass transport40,41. This discrepancy occurs because the electrosorbed CO32- species are also present on the surface, and the combined effect of these intercalated and adsorbed CO32- remains strongly positive for the OER activity (vide infra).

Mechanistic investigations

On the basis of the conclusions above, a fundamental question arises: why do these classic oxyhydroxide OER catalysts have contrasting responses to intercalated carbonate ions? To further understand the specific behaviors among different oxyhydroxides, we created a well-defined system by preparing a series of model catalysts with increased degrees of intercalation (denoted as TMOOH-xCO32-, TM is Ni, Co or NiCo). They are synthesized by soaking pristine TMOOH in 0.1 M KOH aqueous solutions containing 0.01 M CO32-, 0.05 M CO32-, 0.1 M CO32- and 0.2 M CO32-, respectively, for 24 h, as shown in Fig. 3a. The XRD patterns in Fig. S14 confirm successful and complete intercalation after the anion exchange process, as the corresponding interplanar distance increases progressively from that of the pristine samples to the most heavily intercalated samples. The bulk properties are in accordance with the surface characterization results revealed by XPS and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), as shown in Figs. S15 and S16. For example, the surface concentration of carbonate (Fig. S15a), corresponding to a binding energy of ~289 eV from the deconvoluted C 1 s core-level spectra, is 0%, 3.3%, 5.2%, 8.8% and 9.6% for CoOOH, CoOOH-1CO32-, CoOOH-2CO32-, CoOOH-3CO32- and CoOOH-4CO32-, respectively. The same trend is also observed for NiOOH-xCO32- as shown in Fig. S15b. The FTIR peaks corresponding to the C-O and C = O stretching vibrations are also prominent among the model catalysts after intercalation (Fig. S16).

a Schematic illustration of all TMOOH-xCO32- model catalysts; b comparison of the onset potential and Tafel slope of TMOOH-xCO32- obtained from LSV and MSLSV; c–e comparison of the η10 (the overpotential at 10 mA cm−2) values for pristine TMOOH-xCO32- and those after being soaked in 0.1 M KOH aqueous solution with and without bias at 1.6 V vs. RHE for 12 h. All measurements were conducted in 0.1 M KOH at 25 °C with a scan rate of 5 mV s-1 and a solution resistance (Rs) of 12.2 ± 0.5 Ω. Box plots display the median (centerline), the interquartile range (IQR; box bounds from the 25th to the 75th percentile), and the whiskers encompassing 1.5× IQR from the quartiles. All points outside the whiskers are defined as outliers.

The OER test is performed in a purified 0.1 M KOH electrolyte without carbonate. Figure S17 compares the LSVs and Tafel slopes of various model catalysts. Owing to the potential window overlap between the OER and metal oxidation, we also used differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) to accurately determine the onset potential and Tafel slope from the MSLSVs, as shown in Fig. 3b and S18. Notably, a higher degree of intercalation indeed worsens the OER performance of CoOOH and NiCoOOH. Compared with those of the pristine sample, the onset potential and Tafel slope of the most heavily intercalated sample increase by >100 mV and ~60 mV dec-1, respectively. Conversely, the OER performance of all intercalated NiOOH catalysts is greatly improved compared with that of the pristine. This is in fact, not due to CO32- intercalation but is attributable to the presence of surface-adsorbed CO32- (see the FTIR spectra in Fig. S16c and the computational simulation below). Interestingly, the OER activity manipulation by the intercalated CO32- can be fully reversible. Figures 3c–e and S19 show the recovery behaviors of model catalysts after soaking in 0.1 M KOH aqueous solution (1) with bias at 1.6 V vs. RHE for 12 h, which is fully irreversible, and (2) without bias at 1.6 V vs. RHE for 12 h, which is fully reversible. This implies that potential bias might suppress the deintercalation of CO32-.

To explore the OER pathway, we performed 18O isotopic labeling for all model catalysts and carried out operando DEMS studies42,43. The incorporation of 18O isotopes into the catalyst lattice is achieved through galvanostatic electrolysis (4 mA cm-2, 12 h) in 0.1 M KOH using H218O as the solvent. The subsequent DEMS study of these labeled catalysts is carried out in 0.1 M KOH using H216O as the solvent, where the 18O from the evolved diatomic oxygen can be traced to the labeled lattice oxygens. Figure 4a shows the MS signals when the catalysts are biased between 0.86 and 1.66 V vs. RHE via cyclic voltammetry. In NiOOH-xCO32- and NiOOH, only the 32O2 signal is recorded, suggesting the AEM pathway of the OER. Its peak intensity increases gradually with increasing degree of intercalation, which is consistent with the increased OER activity shown above. In contrast, signals of both 32O2 and 34O2 are recorded in the pristine and moderately intercalated Co and NiCo samples including TMOOH-1CO32-, TMOOH-2CO32- and TMOOH-3CO32-, implying the presence of reactive LOs for OER catalysis44,45. This conclusion aligns with the pronounced pH-dependent OER activity (Figs. S20-22)8,46,47. The progressively decreased 34O2/32O2 ratio and proton reaction order in Fig. 4b reflect the decrease in LO reactivity. Conversely, no 34O₂ signal is observed in TMOOH-4CO32-, whereas the proton reaction order decreases to less than 0.37. This proves that LO is completely deactivated with the disappearance of the LOM pathway.

a Spectrometric signals of 32O2 and 34O2 recorded in the cyclic voltammetric scan between 0.86 and 1.66 V vs. RHE for various model catalysts in 0.1 M KOH solution with a scan rate of 1 mV s−1; b comparison of 34O2/32O2 and proton reaction order among model catalysts; c spectrometric signals of 32O2 and 34O2 recorded in pristine catalysts biased at 1.66 V vs. RHE; the CO32- concentration in the 0.1 M KOH electrolyte is sequentially switched from 0 M to 0.01 M, 0.05 M, 0.10 M, and 0.20 M under operando conditions.

We also examined the dynamic behavior of TMOOH in response to CO32--containing electrolytes via DEMS, as shown in Fig. 4c. The 18O-labeled CoOOH, NiCoOOH, and NiOOH catalysts are initially biased at 1.66 V vs. RHE in 0.1 M KOH which is sequentially changed to the ones including 0.01 M CO32-, 0.05 M CO32-, 0.10 M CO32-, and 0.20 M CO32- under operando conditions. The diatomic oxygen signal increases for NiOOH but decreases for CoOOH and NiCoOOH when the carbonate concentration in the electrolyte increases. This result is consistent with that obtained in the CCL test. The 34O2 signal is only observed in CoOOH and NiCoOOH, which gradually decreases upon the introduction of CO32-, confirming the deactivation of the lattice oxygens. It recovers when the electrolyte is changed back to a pure 0.1 M KOH solution. This trend is further supported by the investigation of LO dynamics in different potential windows using 18O-labeled model catalysts, as shown in Fig. S23a. Two model reactions were selected: the sulfite (SO32-) oxidation reaction (SOR) features a direct chemical reaction between the oxyhydroxide and SO32- (i.e., at the open-circuit potential), which is an ideal process for studying the chemical reactivity of LO; ethylene glycol oxidation (EGOR) occurs simultaneously with Ni2+/Ni3+ conversion (~1.3 V vs. RHE; see Fig. S24–26 for more details), which is substantially lower than the OER potential.

Structure‒mechanism relationships and practical implications

To establish the relationship between the intercalated model catalysts and the distinctive reaction pathway evolution, we used X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to explore their electronic structure changes upon intercalation. The X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra of the Co and Ni K-edges, as shown in Fig. 5a, b, reveal a negative shift in the photon energy upon carbonate ion intercalation, suggesting a reduction in the average oxidation state of both Co and Ni cations. Concurrently, the increase in white line intensity after intercalation suggests a decrease in geometrical distortion of the MO6 octahedron and Co/Ni 3d - O 2p orbital hybridization (M-O bond covalency)48,49, which is in accordance with the theoretical understanding of LO reactivity50,51.

a, b Co and Ni K-edge XANES spectra; c Fourier transforms of K3-weight Co and Ni K-edge FT-EXAFS spectra; d wavelet transforms for the K3-weight Co and Ni K-edge EXAFS signals; e the fitting bond length data; f Ov (oxygen vacancy) formation energy of CoOOH and NiCoOOH with different degrees of carbonate ion intercalation.

To discern the dominant factor influencing the electronic structure change and LO reactivity, we performed a detailed analysis of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and wavelet transform (WT). The Co and Ni K-edge k³χ(k) oscillation curves in Fig. S27 show notable peak shifts, confirming the increase in the average M‒O bond length after intercalation. This is further corroborated by the Fourier transform EXAFS (FT-EXAFS) spectra and WT analysis (Fig. 5c, d). Two peaks in the FT-EXAFS spectra located at ~1.5 and ~2.5 Å are assigned to the Co-O/Ni-O and Co-Co/Ni-M bonds, respectively. A positive correlation between the Co-Co/Ni-M peak intensity and the degree of ion intercalation is observed, confirming that the CoO6/NiO6 in CoOOH/NiCoOOH-2CO32- is the least distorted. The fitted Co-O/Ni-O and Co-Co/Ni-M bond lengths of all the model catalysts are summarized in Fig. 5e and Tables S3 and S4. Apparently, the longer Co-O and Ni-O bond lengths in CoOOH-2CO32- and NiCoOOH-2CO32- and reduced octahedral distortion might reflect the difficulty of forming covalent bonds, pinpointing the decreased M-O covalency and eliminated LO reactivity52,53.

On the basis of the characterization results, we established carbonate ion-intercalated TMOOH models and performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations, with a focus on the oxygen vacancy (Ov) formation energy (EOv), which is a key descriptor of LO reactivity48,54,55. The results shown in Fig. 5f indeed show that EOv increases drastically upon the insertion of carbonate ions. Notably, the adsorbed carbonate ions might be also detrimental to the LO reactivity (see Fig. S28 for details). We also evaluated the M-O bond covalency of model catalysts, which can be quantified by the charge transfer energy between the unoccupied metal 3d- and occupied O 2p-band centers (Δε)55. The schematic relationship between M-O covalency and LO reactivity is illustrated in Fig. S29. Pristine CoOOH and NiCoOOH have the lowest Δε, which is consistent with the highest degree of M-O covalency and correlates with their high experimentally observed LO reactivity during the OER (see Table S5). With increasing degrees of intercalation, Δε rises up progressively, eventually leading to the diminish of LO reactivity. In contrast, the intrinsically higher Δε of pristine NiOOH aligns with the absence of LO reactivity. Carbonate intercalation increases Δε further, thereby disfavoring the activation of lattice oxygens.

We then examined the effect of CO32- intercalation on the structural change of NiOOH. The XANES data in Fig. S30 and Table S6 reveal that NiOOH undergoes similar electronic structure changes where CO32- intercalation reduces the Ni oxidation state and the degree of distortion in the NiO6 octahedron. The free energy changes of the OER elementary steps via the AEM for NiOOH, CO32--adsorbed NiOOH, and CO32--intercalated NiOOH are also calculated (see Fig. S31). The deprotonation of *OH serves as the rate-determining step (RDS) for all catalysts. Both carbonate adsorption and intercalation lower the theoretical energy barrier of this step. The more substantial barrier reduction in the adsorbed model suggests that adsorbed carbonates are likely the primary contributor to the enhanced OER activity observed in NiOOH, particularly when both adsorbed and intercalated species are present34,39.

In light of the abovementioned results and analyses, the distinct impacts of carbonate ions on different types of oxyhydroxide OER catalysts are illustrated in Fig. S32. In principle, carbonate ions from the electrolyte can be easily adsorbed onto the anode surface and inserted into the interlayer spacings because of the fast ion exchange rate35,56. For NiOOH without reactive LO, chemisorbed CO32- is crucial for increasing OER activity. Such activity modulation is reversible once the carbonate anions are removed from the electrolyte. In contrast, for oxyhydroxides with reactive LO, there is a strong negative correlation between the OER activity and the degree of CO32- intercalation. When a sufficient number of ions are inserted, the decreased metal‒oxygen bond covalency leads to suppressed LO reactivity, resulting in gradual evolution of the OER pathway from the LOM to the AEM and worsening OER activity. This transition, together with the LO dynamics, is also fully reversible when CO32- is removed from the interlayer spacings.

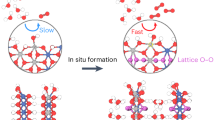

Understanding such effects has strong practical implications for developing highly active yet robust OER catalysts featuring reactive LO. We examined the performance of all model catalysts under industrially relevant conditions in a zero-gap alkaline water electrolyzer (see Fig. S33)57. All electrolyzers show reasonable performance, as demonstrated by the polarization curves in Fig. S34. For example, at the benchmark voltage of 2 V, the electrolyzer employed with a CoOOH anode delivers a high current density of 766 mA cm−2. However, their stability varies substantially under galvanostatic electrolysis at 500 mA cm-2 in a 6 M KOH solution, as shown in Fig. 6a. No voltage degradation is observed in either NiOOH or NiOOH-2CO32- cells. The higher activity of the NiOOH-2CO32- electrode is indeed maintained in the carbonate-free electrode under potential bias, which is in line with the model catalyst study above. Neither the CoOOH nor the NiCoOOH cell is stable, the performance of which deteriorates rapidly within 100 h. In contrast, both the CoOOH-2CO32- and NiCoOOH-2CO32- cells have low electrolysis voltages with negligible voltage decay even after 5000 h (<0.16 mV per 100 h, see Fig. 6b).

a Stability test of alkaline water electrolyzers with different anode catalysts in a 6 M KOH solution at 25 °C, the inset shows the photograph of an assembled zero-gap alkaline water electrolyzer; b potential loss for different anode catalysts after the stability test; c operando Raman spectra of model catalysts biased at 1.6 V (vs. RHE) in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte using H218O or H216O as the solvent; d plots of the Ni3+-O Raman peak position as a function of time during the lattice-oxygen incorporation and release steps; e schematic illustration of the dynamic equilibrium between the lattice-oxygen release and refilling steps caused by CO32- intercalation during OER catalysis via the LOM pathway.

Interestingly, adding 0.2 M CO32- to the electrolyte does not affect the performance of the CoOOH-2CO32- and NiCoOOH-2CO32- electrodes, as shown in Fig. S35, suggesting that the potential bias might be beneficial in suppressing carbonate deintercalation in a pure KOH solution. A longevity test at 1 A cm-2 is also carried out to examine the catalyst stability at a higher anodic potential. No apparent performance degradation is observed over the testing period (see Fig. S36). The DEMS study, combined with the isotopic labeling of the spent catalysts in Fig. S37 implies that the LO reactivity is sustained. The electrocatalytic stability is also reflected by the structural integrity: the inductively coupled plasma‒mass spectrometry (ICP‒MS) results in Fig. S38 show the relatively low leaching rate of transition metals from the catalysts to the electrolyte. Thus, both CO32--intercalated oxyhydroxides are rather durable while featuring the LOM pathway in the OER. A detailed comparison with the literature is shown in Table S7.

To understand the high stability of CO32--intercalated TMOOH with sustained LO reactivity, we designed an operando experiment by combining Raman spectroscopy and 18O isotopic labeling to investigate the kinetics of LO release and incorporation. In the LO incorporation step, the spectrum is collected every 10 min while the catalyst is biased at a constant potential of 1.6 V vs. RHE in the H218O electrolyte. After 80 min, an identical procedure is executed to examine the LO release process while the electrolyte is replaced with H216O solution. As shown in Fig. 6c, in NiOOH, the peaks at 486 and 545 cm-1 correspond to Eg bending and A1g stretching vibrations of Ni3+-O vibrations, respectively58,59. It does not show any shift throughout the entire process, implying no incorporation of 18O into the lattice. Conversely, the peaks of both the NiCoOOH and NiCoOOH-2CO32- catalysts clearly redshift by 38 cm−1 during the 18O incorporation step, confirming the formation of Ni3+-18O bonds60,61. They blueshift during the 18O release step, suggesting the gradual removal of lattice 18O. When the 18O exchange is complete, no further shift is recorded.

Therefore, the peak shift rate becomes a reasonable descriptor for evaluating the kinetics of lattice oxygen release and refilling processes. Figure 6d shows the plot of the shift in the Ni3+-O A1g Raman stretching vibration as a function of time for both processes. CO32- intercalation does not significantly affect the LO incorporation rate since the absolute value of the slope in the linear region for NiCoOOH-2CO32- (0.76 cm−1 min−1) is similar to that of NiCoOOH (0.84 cm−1 min−1). However, the LO release rate is greatly suppressed by CO32- intercalation, and the slope drastically decreases from 1.40 cm−1 min−1 in NiCoOOH to 0.80 cm−1 min−1 in NiCoOOH-2CO32-. This results in essentially identical LO release and refilling rates, which are beneficial for increasing the structural stability during LO exchange in catalysis. It also demonstrates that CO32- intercalation has a stronger effect on suppressing LO release and the sequential formation of oxygen vacancies, therefore enabling the dynamic equilibrium between LO release and LO refilling (see Fig. 6e). This dynamic equilibrium effectively inhibits the net production of abundant oxygen vacancies and the sequential dissolution of metal centers. Therefore, while catalyzing the OER via the LOM pathway, NiCoOOH-2CO32- is more stable among the controls.

Discussion

In this work, we show that carbonate cations in an electrolyte can greatly affect the LO dynamics of typical oxyhydroxide catalysts during the OER. For NiOOH, which shows no LO reactivity, there is a strong positive correlation between the amount of adsorbed CO32- and the OER activity, yet the intercalated CO32- can hardly alter the activity. In comparison, for CoOOH and NiCoOOH, which feature high LO reactivity, the adsorbed CO32- does not much affect the OER activity. Yet, the increasing degree of CO32- intercalation progressively decreases the LO reactivity and OER activity, shifting the reaction pathway from the lattice oxygen mechanism to the adsorbate evolution mechanism. CO32- intercalation offers a viable strategy for manipulating the release rate of LO during the OER, enabling the development of robust and active catalysts with sustained LO reactivity.

More studies should be conducted regarding the interplay between the LO and the surrounding environment to deepen the fundamental understanding. Besides, it is also likely that the synthetic procedure and storage conditions might introduce impurities to the catalysts in different ways (e.g, surface adsorption and intercalation), altering the reaction pathways via manipulating the lattice oxygen reactivity. This work offers an example that reveals the intricacy of LO dynamics, demonstrating opportunities for designing high-performance electrocatalysts for real-life applications.

Methods

Materials synthesis procedure

Materials and reagents

Chemical reagents, including Co(NO3)2, Ni(NO3)2, NaClO, KOH, K2CO3, Na2SO3, and ethylene glycol (EG), were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. with analytical grade purity and were used without purification. The porous separator was the wet-laid nonwoven fabric offered by the NewCom energy material store. The electrolyte for each catalytic reaction was prepared by dissolving the corresponding reagents in deionized (DI) water before each measurement.

Preparation of TMOOH

We first prepared transition metal (TM, Ni, Co, and Ni0.9Co0.1) hydroxide via electrodeposition. For instance, to prepare Co(OH)2, the carbon cloth, Pt plate (1 cm × 1 cm), and Hg/HgCl electrode were used as the working electrode (cathode), counter electrode, and reference electrode, respectively. The electrolyte was a 0.2 M Co(NO3)2 solution. Electrodeposition was carried out at a current density of 10 mA cm-2 for 600 s. Then, the deposited Co(OH)2 was removed from the carbon cloth and washed with deionized water several times. To convert hydroxide to oxyhydroxide, we followed a well-established method via chemical oxidation62,63. Specifically, 0.1 g of Co(OH)2 and 30 mL of NaClO (5 wt%) solution were added to a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, and the pH was adjusted to 13 with a 0.1 M KOH solution. The autoclave was heated to 100 °C, which was maintained for 9 h to yield a black powder that was retrieved via centrifugation. The CoOOH powder was washed with DI water at least three times and then dried in a vacuum drying oven. The synthesis of other TMOOHs followed the same procedure.

Preparation of CO3 2--intercalated TMOOH

To obtain TMOOH-1CO32-, TMOOH-2CO32-, TMOOH-3CO32- and TMOOH-4CO32− model catalysts, pristine TMOOH powder (0.1 g) was soaked in 0.1 M KOH solutions with 0.01 M, 0.05 M, 0.10 M and 0.2 M K2CO3, respectively, for 12 h. The retrieved powder was washed with DI water at least three times and then dried in a vacuum drying oven.

Materials characterization

The X-ray diffraction patterns of the samples were obtained via a Cu-Kα X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku Smartlab). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed with an ESCALab 250Xi (Thermo Scientific) spectrometer. To obtain the depth profile, Ar+ sputter etching was used to remove the surface layer. Transmission electron microscopy analysis was carried out via an aberration-corrected JEM-ARM200CF microscope operated at 200 kV with a Schottky cold-field emission gun. A high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) detector and an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) detector were used to obtain dark field micrographs and elemental information, respectively. A Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, Bruker, Invenior, 1200–4000 cm−1) equipped with a liquid-nitrogen-cooled MCT (HgCdTe) detector was used to collect the FTIR spectrum. X-ray absorption spectroscopy was performed using an easyXAFS300+ spectrometer.

Procedure of operando spectroscopic and spectrometric studies

Operando surface-enhanced IR absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS) analysis was carried out using the same FTIR spectrometer. In the homemade in situ electrochemical cell mounted on the PIKE VeeMAX III ATR accessory (see Fig. S11), the working electrode was a silicon crystal (2 cm diameter). For each experiment, the silicon crystal was polished and then coated with a gold film via electroless deposition. The catalyst was drop-casted onto the gold film via an ink containing 5 mg of catalyst, 20 μL of 5 wt% Nafion solution (DuPont), 320 μL of ethanol, and 160 μL of DI H2O. The counter electrode was platinum, and the reference electrode was Hg/HgO (in 0.1 M KOH). The volume of used electrolyte was ~20 mL.

Operando Raman spectra were obtained with a confocal micro-Raman system (XploRA Plus, Horiba). All measurements were conducted with a He-Ne laser at a wavelength of 638 nm. A calibration using the silicon wafer was carried out before each experiment. The in situ electrochemical Raman experiments were carried out in a custom Raman cell (see Fig. S39), which employed a Pt wire as the counter electrode and Hg/HgO (in 0.1 M KOH) as the reference electrode. The electrolyte volume was ~5 mL.

Differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) was carried out via a PFEIFFER QAS100 Quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a turbopump (HIPACE 80, PFEIFFER). The electron energy and emission current were set at 70 eV and 2000 μA, respectively. The homemade DEMS cell (see Fig. S40) contained a 40 μm-thick gold-coated porous PTFE film (porosity of 50%, pore size of 20 nm; Shanghai LingLu Instrument Corp., Ltd., China) interface that separates the aqueous electrolyte from the vacuum. The catalyst ink was drop-casted on a porous gold film, which functioned as the working electrode. A Pt wire and a Hg/HgO electrode were used as the counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. The electrolyte volume was ~2 mL. To switch the electrolyte under operating conditions, a circulating electrolyte system was applied.

Electrochemical measurement and procedure

Basic procedures

All the electrochemical measurements were carried out with a CHI660 electrochemical workstation. In a typical three-electrode setup, a platinum plate (1 cm × 1 cm) and a Hg/HgO electrode were used as the counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. The Hg/HgO reference electrode was calibrated against a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) in the same electrolyte. Briefly, a clean Pt wire was used as the working electrode in H₂-saturated 0.1 M KOH, and the potential at which the hydrogen oxidation/reduction current crossed zero was recorded. The potential of the Hg/HgO electrode was then calculated via the equation E(Hg/HgO) = E(RHE) - 0.926 V, and all reported potentials were adjusted accordingly. The catalyst served as the working electrode and was fabricated by drop-casting an ink onto a carbon cloth (1 cm × 1 cm). The ink was prepared by dispersing 5 mg of the catalyst in a mixture of 920 μL of ethanol, 50 μL of DI water, and 30 μL of a 5 wt% Nafion solution (DuPont). The resulting catalyst loading was 2 mg cm−2. Other than specified, all electrochemical measurements were conducted at pH = 13 ± 0.1 in a 0.1 M KOH solution. In the study of the sulfite oxidation reaction (SOR), 0.1 M KOH + 0.1 M Na2SO3 was used as the electrolyte, yet the reaction was carried out at the open-circuit potential (OCP). For ethylene glycol oxidation (EGOR), 0.1 M KOH + 0.3 M EG was used as the electrolyte. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed at 1.46 V vs. RHE, employing a frequency range from 10−2 to 105 Hz under a sinusoidal potential perturbation with an amplitude of 5 mV. In a typical voltammetric experiment, the scan rate was 5 mV s−1. Post-iR compensation was applied at 90% of the solution resistance for all reported potentials, which were converted to a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) via the following equation:

The electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) calculation

The ECSA was evaluated through double-layer capacitance (Cdl) measurements. First, CV scans were conducted in a non-Faradaic potential window (0.86–0.96 V vs. RHE) at 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 mV s−1. The capacitive current at a central potential was subsequently plotted as a function of the scan rate. The Cdl was obtained from the linear fit of this plot. Finally, the ECSA was calculated via the following formula:

where Cs is the specific capacitance per unit area. The Cs value is 0.040 mF cm−2 in this work.

The “CO3 2--looping” experiment (CL)

In the forward scan, linear sweep voltammograms (LSVs) of pristine TMOOH were sequentially obtained in 0.1 M KOH solution with increasing carbonate ion concentrations (0 M, 0.01 M, 0.05 M, 0.10 M, 0.20 M, and 0.40 M). Then, the backward scan started immediately, where the LSVs of the same electrode were sequentially obtained in 0.1 M KOH solution with stepwise decreases in carbonate ion concentrations (0.40 M, 0.20 M, 0.10 M, 0.05 M, 0.01 M, and 0 M). The corresponding K2CO3 solution was used to adjust the carbonate ion concentration. For each catalyst, the CL test was conducted >6 times with the materials prepared from 3 batches. All the obtained data points were used in the plot for statistical analysis to minimize the effect caused by artifacts.

The “CO3 2--CV-looping” experiment (CCL)

In the forward scan, linear sweep voltammograms (LSVs) of pristine TMOOH were also sequentially obtained in 0.1 M KOH solution with increasing carbonate ion concentrations (0 M, 0.01 M, 0.05 M, 0.10 M, 0.20 M, and 0.40 M). However, before the LSV was recorded, 100 cycles of cyclic voltammetry (CV, 0.85 ~ 1.77 V vs. RHE at 10 mV s−1) were applied to the electrode in each designated electrolyte. Then, the backward scan started immediately, where the LSVs of the same electrode were sequentially obtained in 0.1 M KOH solution with stepwise decreases in carbonate ion concentrations (0.40 M, 0.20 M, 0.10 M, 0.05 M, 0.01 M, and 0 M). Again, 100 cycles of cyclic voltammetry (CV, 0.85~1.77 V vs. RHE at 10 mV s−1) were applied to the electrode in each designated electrolyte before the LSV was recorded. For each catalyst, the CL test was conducted >6 times with the materials prepared from 3 batches. All the obtained data points were used in the plot for statistical analysis to minimize the effect caused by artifacts.

Study of TMOOH-xCO3 2- model catalysts

LSVs of TMOOH-xCO32- model catalysts were obtained in a 0.1 M KOH solution. For the soaked samples, TMOOH-xCO32- model catalysts were first soaked in 0.1 M KOH solution with or without bias at 1.6 V vs. RHE for 12 h before the LSVs were recorded in 0.1 M KOH solution. For each catalyst, this test was conducted >6 times with the materials prepared from 3 batches. All the obtained data points were used in the plot for statistical analysis to minimize the effect caused by artifacts.

18O isotopic labeling experiment

Other than specified, 18O isotopic labeling of the catalyst was carried out in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte using H218O (98% H218O, Energy Chemical) at a constant anodic current density of 4 mA cm−2 for 12 h. After that, the catalysts were soaked in H216O DI water for 10 min before being washed with H216O DI water >3 times to remove the surface-adsorbed H218O.

OER experiment. The 18O-labeled catalyst was assembled into a DEMS cell and subjected to cyclic voltammetry between 0.86 and 1.66 V vs. RHE to drive the oxygen evolution reaction. The ionic current signals of the evolved oxygen species were monitored in real time by a mass spectrometer. To distinguish the signal from the natural abundance of ¹⁸O, the ionic current signals of 34O2 and 32O2 were collected for both the ¹⁸O-labeled and unlabeled NiCoOOH and CoOOH catalysts via DEMS. The resulting data, including the integrated area ratio of ³⁴O₂ to ³²O₂, are presented in Fig. S41.

SOR experiment. The 18O-labeled catalysts were soaked in 0.1 M KOH + 0.1 M K2SO3 for 12 h with H216O as the solvent to enable spontaneous SOR. No potential bias was applied in this chemical reaction. The resulting electrolyte was heated to remove all water, and the retrieved solid powder was analyzed by time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS, Tescan AMBER).

EGOR experiment. The 18O-labeled catalysts were biased at a constant potential of 1.45 V (vs. RHE) in 0.1 M KOH + 0.3 M EG electrolyte for 24 h with H216O as the solvent. After electrolysis, the electrolyte was concentrated and acidified with an HCl solution. Finally, the acidified solution was mixed with acetone for gas chromatography‒mass spectrometry (GC‒MS, Agilent 8890 GC‒7000E system, USA).

Lattice oxygen incorporation and release experiments

This experiment was carried out via operando Raman spectroscopy. First, the 18O incorporation step took place by biasing the pristine catalyst at 1.65 V vs. RHE in a 0.1 M KOH electrolyte with H218O as the solvent. The spectrum was collected every 10 min. After 80 min, the electrolyte was replaced with 0.1 M KOH with H218O as the solvent, and then an identical procedure was executed to obtain the Raman spectrum.

Alkaline water electrolyzer assembly and test

The alkaline water electrolyzer (AWE) used in this study features a zero-gap configuration that comprises endplates, gaskets, Ti current collectors, an anode electrode (1 cm × 1 cm), a 130 μm-thick porous separator (3 cm × 3 cm, wet-laid nonwoven fabric by polyolefin, purchased from NewCom Energy Material Store), and a cathode electrode (see Fig. S33). Prior to use, the porous separator was immersed in a 6 M KOH solution for 48 h. Transition metal hydroxyl oxides were synthesized directly onto nickel foam (NF, 1 cm × 1 cm) as an anode via electrodeposition. TMOOH was subsequently formed under an anodic potential bias during the test. To prepare the carbonate ion-intercalated electrode, the TMOOH electrode was soaked in the designated solution for 12 h and then rinsed with DI water three times. The circulating electrolyte was a 6 M KOH solution stored in a gas-tight container. Electrolyte flow was enabled by a peristaltic pump.

Computational simulation procedure

Our density functional theory (DFT) calculation is based on the Cambridge Serial Total Energy Package (CASTEP) module. Within this framework, the electron-ion interactions were modeled with ultrasoft pseudopotentials, and the exchange-correlation effects were treated using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) formulation of the generalized gradient approximation (GGA). A plane-wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 400 eV was employed for all surface models. The Brillouin zones for the CoOOH and NiCoOOH systems were sampled at the Gamma point using a 1 × 1 × 1 k-point mesh. Structural optimizations were considered converged upon meeting the following criteria: an energy tolerance of 2.0 × 10⁻⁵ eV/atom, a maximum force of 0.05 eV/Å, a stress below 0.1 GPa, and a maximum displacement of 0.002 Å64. The CoOOH (110) and NiCoOOH (110) surface models with two-layer slabs were constructed on the basis of the optimized CoOOH and NiCoOOH crystal cells. The surface model was constructed with a substantial vacuum thickness of 15 Å along the non-periodic direction. This ensures that the interactions between periodic replicas of the slab are negligible. The files of the optimized computational models in CIF format are given in Supplementary Data 1.

The formation energy of an oxygen vacancy in charge state q was calculated for the CoOOH, CoOOH-CO32-, NiCoOOH, and NiCoOOH-CO32- systems using the following equation:

In this equation, \({E}_{T}\left({defect}:q\right)\) and \({E}_{T}\left({perfect}\right)\) denote the total energies of the charged defective and pristine supercells, respectively. \({E}_{{VBM}}\) represents the valence band maximum energy. \({\mu }_{O}\) is the oxygen chemical potential, and \({\varepsilon }_{F}\) is the Fermi energy referenced to the \({E}_{{VBM}}\). We considered charge states q from 0 to +2 for the oxygen vacancy. For charged defects, a compensating background charge was applied to maintain overall supercell neutrality. To ensure consistent band alignment, the electrostatic potential of atoms in the pristine supercell was used as a reference for the defective supercell. The Fermi level \({\varepsilon }_{F}\) was varied over the computational band gap to determine the thermodynamically stable charge state. EVBM is evaluated via the following equation:

where \({E}_{{VBM}}^{{perfect}}\) refers to the valence band maximum energy of the perfect supercell. The terms \({V}_{{aV}}^{{defect}}\) \({{{\rm{and}}}}\) \({V}_{{aV}}^{{perfect}}\) correspond to the average electrostatic potentials in the defect and perfect supercell, respectively. \({E}_{T}\left({perfect}:0\right)\) and \({E}_{T}\left({perfect}:+2\right)\) represent the total energies of the perfect supercell at neutral and +2 charge states, respectively.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and Supplementary Information file, and are also provided in the Source Data file. Other relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

McCrory, J. et al. Benchmarking hydrogen evolving reaction and oxygen evolving reaction electrocatalysts for solar water splitting devices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4347–4357 (2015).

Wang, X. et al. Efficient electrically powered CO2-to-ethanol via suppression of deoxygenation. Nat. Energy 5, 478–486 (2020).

Jiang, X. Y. et al. Integrating hydrogen utilization in CO2 electrolysis with reduced energy loss. Nat. Commun. 15, 1427–1439 (2024).

Leech, C. M. et al. A practical guide to electrosynthesis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 275–286 (2022).

Zhao, Z. L. et al. Boosting the oxygen evolution reaction using defect-rich ultrathin ruthenium oxide nanosheets in acidic media. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 5143–5151 (2020).

Song, F. et al. Transition metal oxides as electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction in alkaline solutions: an application-inspired renaissance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7748–7759 (2018).

Chen, D. et al. Nonstoichiometric oxides as low-cost and highly-efficient oxygen reduction/evolution catalysts for low-temperature electrochemical devices. Chem. Rev. 115, 9869–9921 (2015).

Grimaud, A. et al. Activating lattice oxygen redox reactions in metal oxides to catalyse oxygen evolution. Nat. Chem. 9, 457–465 (2017).

Koper, M. T. M. Theory of multiple proton-electron transfer reactions and its implications for electrocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 4, 2710–2723 (2013).

Halck, B. N. et al. Beyond the volcano limitations in electrocatalysis - oxygen evolution reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 13682–13688 (2014).

Kanan, W. M. et al. In situ formation of an oxygen-evolving catalyst in neutral water containing phosphate and Co2+. Science 321, 1072–1075 (2008).

Assat, G. et al. Fundamental understanding and practical challenges of anionic redox activity in Li-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 3, 373–386 (2018).

Aydinol, K. M. et al. Ab initio study of lithium intercalation in metal oxides and metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 56, 1354–1365 (1997).

Ceder, G. et al. Identification of cathode materials for lithium batteries guided by first-principles calculations. Nature 392, 694–696 (1998).

Sun, Y. M. et al. Covalency competition dominates the water oxidation structure-activity relationship on spinel oxides. Nat. Catal. 3, 554–563 (2020).

Hong, W. T. et al. Charge-transfer-energy-dependent oxygen evolution reaction mechanisms for perovskite oxides. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 2190–2200 (2017).

Hwang, J. et al. Perovskites in catalysis and electrocatalysis. Science 358, 751–756 (2017).

Rountree, S. E. et al. Potential-dependent electrocatalytic pathways: controlling reactivity with pKa for mechanistic investigation of a nickel-based hydrogen evolution catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13371–13380 (2015).

Yang, C. Z. et al. Phosphate ion functionalization of perovskite surfaces for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 3466–3472 (2017).

Jia, H. N. et al. Unveiling the electrolyte cations dependent kinetics on CoOOH-catalyzed oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313886 (2023).

Li, Y. X. et al. Codecoration of phosphate and iron for improving oxygen evolution reaction of layered Ni(OH)2/NiOOH. ACS Catal. 14, 4807–4819 (2024).

Zhang, Y. J. et al. Selenate oxyanion-intercalated NiFeOOH for stable water oxidation via lattice oxygen oxidation mechanism. J. Energy Chem. 101, 676–684 (2025).

Cai, M. M. et al. Formation and stabilization of NiOOH by introducing α-FeOOH in LDH: Composite electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution and urea oxidation reactions. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209338–2209348 (2023).

Amin, M. A. H. et al. Role of lattice oxygen in the oxygen evolution reaction on Co3O4: Isotope exchange determined using a small-volume differential electrochemical mass spectrometry cell design. Anal. Chem. 91, 12653–12660 (2019).

Zhang, N. et al. Lattice oxygen activation enabled by high-valence metal sites for enhanced water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 11, 4066–4077 (2020).

Wu, F. Y. et al. Engineering lattice oxygen regeneration of NiFe layered double hydroxide enhances oxygen evolution catalysis durability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202413250 (2024).

Chung, Y. D. et al. Dynamic stability of active sites in hydr(oxy)oxides for the oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Energy 5, 222–230 (2020).

Klyukin, K. et al. Iron dissolution from goethite (α-FeOOH) surfaces in water by ab initio enhanced free-energy simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 16086–16091 (2018).

Sun, H. et al. Self-supported transition-metal-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen and oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 32, 1806326 (2020).

Gao, T. G. et al. Switchable acidic oxygen evolution mechanisms on atomic skin of ruthenium metallene oxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 4159–4166 (2025).

Wu, Z. Y. et al. Non-iridium-based electrocatalyst for durable acidic oxygen evolution reaction in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Nat. Mater. 22, 100–108 (2023).

Hao, S. et al. Dopants fixation of ruthenium for boosting acidic oxygen evolution stability and activity. Nat. Commun. 11, 5368–5379 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Molecular dynamics modeling of the structures and binding energies of α-nickel hydroxides and nickel-aluminum layered double hydroxides containing various interlayer guest anions. Chem. Mater. 18, 4405–4414 (2006).

Hunter, B. M. et al. Effect of interlayer anions on [NiFe]-LDH nanosheet water oxidation activity. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 1734–1743 (2016).

Yan, P. et al. Deeply reconstructed hierarchical and defective NiOOH/FeOOH nanoboxes with accelerated kinetics for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 15586–15594 (2021).

Li, L. J. et al. In situ investigation of interfacial water in the hydrogen evolution reaction: A comparative study unraveling the impact of oxide impurity. ACS catal. 14, 15665–15674 (2024).

Markevich, E. et al. Very stable lithium metal stripping-plating at a high rate and high areal capacity in fluoroethylene carbonate-based organic electrolyte solution. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1321–1326 (2017).

Zhou, T. T. et al. Effect of fluoride on the morphology and electrochemical property of Co3O4 nanostructures for hydrazine detection. Materials 11, 207–223 (2018).

Menezes, W. P. et al. Facile access to an active γ-NiOOH electrocatalyst for durable water oxidation derived from an intermetallic nickel germanide precursor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 133, 4690–4697 (2020).

Zhang, S. M. et al. Cobalt carbonate hydroxide superstructures for oxygen evolution reactions. Chem. Commun. 53, 8010–8013 (2017).

Zheng, T. T. et al. CoFe hydroxide nanospheres for enhanced alkaline water splitting and seawater oxidation: anion doping effects of fluorine and carbonate. Chem. Eur. J. 31, e202403628 (2025).

Zhao, K. et al. Operando studies of electrochemical denitrogenation and its mitigation of N-doped carbon catalysts in alkaline media. ACS catal. 13, 2813–2821 (2023).

Zhao, K. et al. Recent development and applications of differential electrochemical mass spectrometry in emerging energy conversion and storage solutions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 6917–6959 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Unlocking lattice oxygen on selenide-derived NiCoOOH for amine electrooxidation and efficient hydrogen production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 27090–27099 (2024).

Moysiadou, A. et al. Mechanism of oxygen evolution catalyzed by cobalt oxyhydroxide: cobalt superoxide species as a key intermediate and dioxygen release as a rate-determining step. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11901–11914 (2020).

Wang, X. P. et al. Understanding of oxygen redox in the oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107956–2107982 (2022).

Wang, L. Q. et al. Modulating the covalency of Ru-O bonds by dynamic reconstruction for efficient acidic oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun. 16, 3502–3512 (2025).

Zhang, N. et al. Lattice oxygen redox chemistry in solid-state electrocatalysts for water oxidation. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4647–4671 (2021).

Tyler Mefford, J. et al. Water electrolysis on La1-xSrxCoO3-δ perovskite electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 7, 11053–11063 (2016).

Fu, Q. et al. In Operando synchrotron diffraction and in Operando X‑ray absorption spectroscopy investigations of orthorhombic V2O5 nanowires as cathode materials for Mg-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2305–2315 (2019).

Chen, M. et al. Boosting the proton intercalation via crystal plane optimization of TiS2 for cycling-stable aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400724–2400734 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Lanthanide-regulating Ru-O covalency optimizes acidic oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 4974–4982 (2024).

Jensen, P. M. et al. Comparison of covalency in the complexes of trivalent actinide and lanthanide cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 9870–9877 (2019).

Rong, X. et al. A fundamental relationship between reaction mechanism and stability in metal oxide catalysts for oxygen evolution. ACS Catal. 6, 1153–1158 (2016).

Song, J. J. et al. A review on fundamentals for designing oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 2196–2214 (2020).

Liu, H.-M. et al. DFT study on MgAl-layered double hydroxides with different interlayer anions: Structure, anion exchange, host–guest interaction and basic sites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 2521–2529 (2020).

Yan, X. Y. et al. A membrane-free flow electrolyzer operating at high current density using earth-abundant catalysts for water splitting. Nat. Commun. 12, 4143–4151 (2021).

Michael, D. J. et al. Alkaline electrolyte and Fe impurity effects on the performance and active-phase structure of NiOOH thin films for OER catalysis applications. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 11475–11481 (2015).

Bo, X. et al. Operando Raman spectroscopy reveals Cr-induced-phase reconstruction of NiFe and CoFe oxyhydroxides for enhanced electrocatalytic water oxidation. Chem. Mater. 32, 4303–4311 (2020).

He, Z. Y. et al. Activating lattice oxygen in NiFe-based (oxy)hydroxide for water electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 13, 2191–2202 (2022).

Lee, S. et al. Deciphering iron-dependent activity in oxygen evolution catalyzed by nickel-iron layered double hydroxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 8072–8076 (2020).

Huang, J. H. et al. CoOOH nanosheets with high mass activity for water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 137, 8846–8851 (2015).

Kashani Motlagh, M. M. et al. Structural properties of nickel hydroxide/oxyhydroxide and oxide nanoparticles obtained by microwave-assisted oxidation technique. Powder Technol. 237, 562–568 (2013).

Tanaka, T. et al. First-principles study on structures and energetics of intrinsic vacancies in SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 68, 205213–205220 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52272233), the Dutch Research Council (NWO) Vidi personal grant (VI.Vidi.192.045), and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515011161). We also thank Dr. Li Lei from the Core Facility of Wuhan University for his assistance with TEM analysis and open sharing subsidies for large-scale instruments and equipment at Wuhan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.K. performed the material synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical tests and wrote the original manuscript. Y. W., X. J. and X. W. conducted the ToF-SIMS and GC‒MS analyses. K. Z. and Y. W. assisted in the calculations. N.Y. conceived the idea, supervised the project and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Chan Woo Lee and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ke, L., Wang, Y., Jiang, X. et al. Carbonate electrolytes manipulate lattice oxygen dynamics of oxyhydroxides toward efficient and durable water oxidation. Nat Commun 16, 11241 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66076-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66076-1