Abstract

Synovitis has recently been shown to be a critical early stage in development of osteoarthritis (OA), and inhibiting synovitis significantly alleviates OA symptoms. Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting RANKL, previously developed for osteoporosis. Here, we report the effect of denosumab on fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLSs), attenuating synovitis and consequently OA progression. We first demonstrate that RANKL is highly expressed in the knee synovium of OA mice, as well as in patients. Next, we show that denosumab, injected systemically, accumulates in the synovium and effectively reduces synovitis through RANK/TRAF6/FSTL1 signalling in post-traumatic, inflammatory, and aged OA murine models and a beagle dog OA model, delaying OA progression. Finally, a single-arm clinical trial with primary endpoints of VAS and OKS scores, and secondary endpoints of WOMAC score and adverse events rate, shows that denosumab alleviates synovitis and pain, improving joint function in knee OA patients. These findings provide a translational basis for using denosumab to treat knee OA in the clinic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common degenerative joint diseases and a major cause of pain and disability1, affecting an estimated 250 million people worldwide2. Knee OA is a whole-joint disorder characterized by articular cartilage destruction, subchondral bone sclerosis, osteophyte formation and inflammation of the synovial membrane3,4,5,6. Despite extensive research, the complex pathological mechanisms underlying the onset and development of OA remain unknown. Consequently, no disease-modifying drugs are available, and current treatments are limited to painkillers such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) until the joint deteriorates to the stage where surgery is necessary. However, NSAIDs can cause gastrointestinal and cardiovascular side effects7, while surgery carries risks of infection and other complications. Therefore, new drugs are urgently needed to treat knee OA in the early stages.

Recently, we and others have found that synovial inflammation (synovitis), characterized by synovial lining hyperplasia, infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes, neoangiogenesis and fibrosis, is strongly associated with cartilage degeneration, abnormal subchondral bone remodelling and osteophyte formation8. Many studies have demonstrated that synovitis is associated with pain and poor function, and it is thus considered to play a critical role in radiographic OA onset and structural progression4,9,10. Both mechanical and non-mechanical factors can transform FLSs to an activated, pathological states during OA, whereupon they secrete various pro-inflammatory and chondrocyte catabolic cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukins (ILs), receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) family members. These factors contribute to joint damage, pain, and OA progression11,12. Therefore, targeting synovitis is a promising therapeutic strategy for OA.

Denosumab is used to treat osteoporosis (OP) and giant cell tumour of bone, acting by downregulating the RANKL/RANK signalling pathway thereby inhibiting the maturation of monocyte–macrophage–osteoclast lineage cells13, which play a significant role in synovial inflammation and potentially OA progression. Although denosumab has been shown to attenuate OA progression in mouse models of post-traumatic OA by modifying subchondral bone remodelling14, the detailed mechanisms remain largely uncharacterized. Furthermore, its efficacy in OA patients requires further validation, as rodent joint biomechanics and physiology differ significantly from those of humans15.

In this work, we use three different murine OA models–post-traumatic, inflammatory and aged OA, and a beagle dog knee OA model to validate the effects of denosumab on synovitis and OA progression. Following this, we conduct a single-arm clinical trial, and find that denosumab attenuates synovitis, reduces joint pain and improves joint function in OA patients. These effects are likely mediated by the RANK/TRAF6/FSTL1 signalling pathway in FLSs.

Results

Expression of RANK and RANKL in healthy and pathological joint tissues

We first investigated the expression levels of RANK and RANKL in OA progression in a mouse model at 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-destabilisation of the medial meniscus (DMM) in mice. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that RANK and RANKL expression in articular cartilage (AC) were not significantly different from the sham groups, but both were markedly increased in synovial membrane (SM) of DMM-induced mice at 4 weeks. Furthermore, expression levels of RANK and RANKL in AC and SM gradually increased over 8 and 12 weeks post-DMM and were more enriched in SM than AC (Fig. 1A–C). Next, we assessed the expression level of RANKL in human healthy and OA joint fluid using ELISA. Results showed that RANKL expression was significantly increased in OA joint fluid compared to healthy joint fluid (Fig. 1D). We then obtained normal human AC and SM tissues from thigh amputation or hemipelvectomy and OA-affected AC and SM tissues from knee arthroplasty of patients at the Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College (Wuhan, China), for western blot and PCR analyses. The results confirmed that, compared with normal AC and SM, the expression levels of RANK and RANKL were significantly increased in OA AC and SM, particularly in the OA SM (Fig. 1E, F). To further consolidate our conclusion, mouse chondrocytes, FLSs and macrophages were isolated from AC or SM and incubated with IL-1β for 24 h to induce inflammation. In line with the previous data, the expression of RANK and RANKL was markedly higher in IL-1β-induced chondrocytes and macrophages and especially in IL-1β-induced FLSs (Fig. 1G). PCR assay of RANK and RANKL in IL-1β-induced chondrocytes, macrophages and FLSs showed the same result (Fig. 1H). Previous studies have identified ColVI as a marker for FLSs11,16. Therefore, we performed co-immunofluorescence staining of RANK or RANKL with ColVI to mark FLSs. As shown in Fig. 1I and Supplementary Fig. 1A, RANK+ cells, RANKL+ cells and ColVI+ cells were all obviously increased in OA synovium (Fig. 1J and Supplementary Fig. 1B). Strikingly, assessment of the proportions of the cell population revealed a change in percentage from 40% to 65% of RANKL+ ColVI+ / ColVI+ (Fig. 1K) and 33% to 55% of RANK+ ColVI+ / ColVI+ (Supplementary Fig. 1C) at 8 weeks after DMM surgery, indicating that FLSs expressing RANK and RANKL greatly expanded under OA conditions. In summary, these data suggest that FLSs with higher expression of RANK and RANKL are strongly associated with OA initiation and progression.

A, B Immunostaining of RANK or RANKL in AC and SM of sham and DMM mice at 4, 8 and 12 weeks after surgery. Scale bar = 50 μm. AC, articular cartilage; SM, synovial membrane. Representative images are from six independent experiments. C The percentages of RANK+ or RANKL+ cells within AC and SM at 4, 8 and 12 weeks post-DMM were quantified (n = 6, biological replicates). D RANKL expression level in the joint fluid among normal and OA patients (n = 6, biological replicates). E, F Western blot and RT-PCR analysis of RANK and RANKL in human articular cartilage and synovial membrane (n = 3, biological replicates). G, H Western blot and RT-PCR analysis of RANK and RANKL in mouse chondrocytes, FLSs and macrophages treated with IL-1β (10 ng/mL) compared with vehicle. CH, chondrocytes; FLSs, fibroblast-like synoviocytes (n = 3, biological replicates). I Representative co-immunostaining of ColVI (red) and RANKL (green) in synovial membrane of sham and DMM mice, counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm. J, K Percentage of ColVI+, RANKL+ and ColVI+; RANKL+ over ColVI+ were calculated (n = 6, biological replicates). Source data and P values are provided in the Source Data file. Data are presented as median with interquartile range. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired two-tailed t-test (J, K) or two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test (D) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (C,E,F,G,H) for multiple comparisons. ns = not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Denosumab ameliorated OA progression in post-traumatic, inflammatory and aged OA models

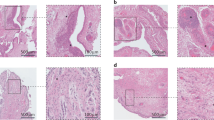

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting RANKL, so we first sought to study its effects in a DMM-induced mouse post-traumatic OA model. Safranin-O/Fast Green staining revealed that cartilage erosion was mild in both femoral condyle and tibial plateau of DMM knees at 4 weeks post-surgery but aggravated at 8 and 12weeks post-surgery. However, in denosumab-treated DMM mice, there was a significant retention of proteoglycan and a marked reduction in the thickness of calcified cartilage areas at 8 and 12 weeks compared to DMM controls (Fig. 2A). Further analysis demonstrated that denosumab reduced the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) score to 28.6% and 29.5% at 8 and 12 weeks, respectively, in OA progression compared with DMM controls (Fig. 2A). We next performed haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of synovium and found abundant inflammatory cell infiltration and synovial hyperplasia at 4, 8 and 12 weeks post-DMM. Treatment with denosumab significantly inhibited these inflammatory effects and reduced the synovitis score (Fig. 2B–E). Micro-CT analysis to evaluate subchondral bone remodelling revealed that DMM caused significant subchondral bone resorption. However, this detrimental effect was effectively reversed by denosumab treatment (Fig. 2G). The results were further confirmed by quantitative analysis of structural parameters, including BV/TV and thickness of subchondral bone plates (SBP. Th) (Fig. 2H). Furthermore, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining revealed hyperactivity of osteoclasts in the DMM group, which was inhibited after denosumab treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Osteophytes, one of the main radiographic features of OA, have significant clinical implications and can be a cause of pain and loss of function1,17. At 8 weeks post-DMM, we observed osteophyte formation and radiological focal defects in both the medial tibial plateau and femoral condyle of mice in the DMM group. Denosumab treatment significantly reduced both osteophyte formation and OA grades compared to the DMM group (Fig. 2F, H and Supplementary Fig. 2B). Since osteophytes are possibly derived from GDF5-lineage cells in synovium18,19, we performed IHC staining of GDF5. Consistent with previous studies, we found a large number of GDF5+ cells in the region where the synovium attached to the edge of the AC in the 8-week post-DMM mice. Intriguingly, GDF5+ cells were markedly reduced in the denosumab-treated mice compared with DMM mice (Supplementary Fig. 2C, D), indicating that denosumab inhibited osteophyte formation by reducing the numbers of osteophyte-derived cells. Markers of cartilage matrix degradation, MMP-13 and ADAMTS5, were also significantly reduced, whereas Col2a1 and Aggrecan were correspondingly increased in denosumab-treated DMM knees (Supplementary Fig. 2E, F). Moreover, the von Frey assay revealed that the paws of DMM mice were sensitive to the stimulus, whereas denosumab improved the paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) compared with control DMM mice (Fig. 2I), suggesting that denosumab heightens mechanical pain sensitivity after DMM.

A Safranin O/Fast green staining of knee joints in the indicated mouse groups at 4, 8 and 12 weeks after DMM surgery. Scale bar = 200 μm. The OA severity of knee joints was evaluated using the OARSI score (n = 6, biological replicates). B–D H&E staining images showing the infiltration of inflammatory cells and thickness of the synovium (dashed lines) in the indicated groups at 4, 8 and 12 weeks after DMM surgery. Magnified images of the boxed areas are shown in the panel on the right. Scale bar = 500 μm (left image); 100 μm (right image). Representative images are from six independent experiments. E Synovitis scores were measured (n = 6, biological replicates). F Representative views of the anterior of the knee joints in the indicated mouse groups derived from micro-CT analysis at 8 weeks after DMM surgery. Red arrowheads indicate osteophyte formation. G Three-dimensional μCT images of the sagittal view of medial tibial subchondral bone at 8 weeks after DMM surgery. (H) Quantification of the grade of OA change and tibial subchondral bone: BV/TV, thickness of subchondral bone plate (SBP. Th) (n = 6, biological replicates). I Pain analysis was performed using the von Frey assay to assess paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) at 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8 weeks after DMM surgery (n = 6, biological replicates). Source data and P values are provided in the Source Data file. Data are presented as median with interquartile range. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons (A, E, H, I). ns = not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

There are several types of OA, which may be the main reason for the heterogeneous response to drugs20. We further evaluated the therapeutic effects of denosumab on a mono-iodoacetate (MIA)-induced inflammatory OA rat model. Histology showed that intra-articular injection of MIA resulted in an irregular surface and a focal area of cartilage loss and degeneration, while denosumab greatly attenuated this phenotype (Fig. 3A), due to reduced levels of ADAMTS5 and MMP-13 (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). H&E staining showed that obvious inflammatory cell infiltration and hyperplasia in MIA synovium were significantly alleviated by denosumab treatment (Fig. 3B). Denosumab also produced an elevation in the PWT in MIA-treated rats compared with vehicle-treated MIA rats, consistent with the DMM model (Supplementary Fig. 3C).

A Safranin O/Fast green staining of knee joints from vehicle, MIA and MIA + denosumab rats. Scale bar = 200 μm. The OA severity of the knee joints was evaluated using the OARSI score (n = 6, biological replicates). B H&E staining of synovium in vehicle, MIA and MIA + denosumab rats. Scale bar = 100 μm. Synovitis scores were measured (n = 6, biological replicates). C Safranin O/Fast green staining of knee joints in young (3-month-old), old (18-month-old) and old + denosumab mice. Scale bar = 200 μm. The OA severity of the knee joints was evaluated using the OARSI score (n = 6, biological replicates). D H&E staining of synovium in the young, old and old + denosumab mice. Scale bar = 100 μm. Synovitis scores were measured (n = 6, biological replicates). Source data and P values are provided in the Source Data file. Data are presented as median with interquartile range. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons (A–D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Moreover, we also investigated the effect of denosumab in an age-induced OA model. In line with other studies, mice displayed moderate cartilage degradation at 18 months of age, while administration of denosumab caused a partial but significant reduction in cartilage degeneration and OARSI scores (Fig. 3C). Synovial hyperplasia analysed by H&E staining was observed in 18-month-old mice and was attenuated after treatment with denosumab (Fig. 3D). IHC results further confirmed that the expression of MMP-13 and ADAMTS5 was upregulated in old mice, but both were downregulated in denosumab-treated old mice (Supplementary Fig. 3C, D).

Finally, denosumab treatment did not alter the body weight, mechanical pain sensitivity, microscopic morphology of the main organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and knee joint), or liver and kidney function, spontaneous locomotor activity, nor did it induce anxiety-like behaviours in mice (Supplementary Fig. 4). Taken together, all these results demonstrated the therapeutic effect of denosumab in delaying synovitis and OA progression, and confirmed that this treatment was harmless in vivo.

Denosumab alleviated RANKL/RANK-mediated synovitis in FLSs

As OA is a complex disease involving multiple tissues of the whole joint, we next tried to identify the main tissues and specific cell type responding to denosumab. We first investigated the distribution of denosumab in vivo. Mice were injected subcutaneously with denosumab, fluorescently labelled with CY5.5 dye (red), and this revealed that denosumab primarily distributed in the synovium, compared to other tissues of the joint (Supplementary Fig. 5A, B).

We next harvested cells from the whole joint of sham, DMM and DMM + denosumab groups at 4 weeks after DMM surgery for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), including cartilage, subchondral bone, meniscus, and synovium (Fig. 4A). Based on the expression of marker genes (Supplementary Table 5), uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) identified 14 distinct single-cell clusters: fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLSs), chondrocytes, seven groups of immune cells (neutrophils, basophils, macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells, T cells, and B cells), haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), endothelial cells, Schwann cells, pericytes and erythrocytes (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, among all the clusters with increased cell proportions after DMM, FLSs showed the most dramatic decrease in cell proportion after denosumab treatment (Fig. 4C). Consequently, we explored the intercellular communication among FLSs, chondrocytes and macrophages, contributing to cartilage erosion and joint inflammation. Interestingly, we identified that FLSs, as the dominant communication “hub”, dramatically increased the number and strength of communications with the other two cell types during OA. However, these effects were strongly inhibited by denosumab treatment (Fig. 4D), indicating that FLSs were the main denosumab-responsive cells. Next, we analysed the detailed changes in the outgoing and incoming signals among FLSs, chondrocytes and macrophages. We found that in the DMM group, FLSs were the dominant contributors to the outgoing inflammatory signals, including TNF, IL6, CCL, CSF and MIF (Supplementary Fig. 6A). On the other hand, the communication patterns of incoming signals revealed that chondrocytes were the main receivers of the inflammatory signals secreted by FLSs, both of which were significantly inhibited by denosumab treatment (Supplementary Fig. 6B). These data suggested that in the early stages of OA, activated OA FLSs are the main contributors to the propagation of inflammation and destruction of the cartilage matrix, acting by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines and proteolytic enzymes. Denosumab markedly blocked the pro-inflammation mediators secreted by FLSs, thereby alleviating the structural progression of OA.

A Design of scRNA-seq experiment. Created in BioRender. Hu, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/esd3e6h. B Visualization of UMAP plot pooled from 14 cell clusters isolated from knee joints of Sham, DMM and DMM + denosumab mouse single-cell transcriptomes. C Percentage of each cell type within knee joints among Sham, DMM and DMM + denosumab mice based on the UMAP distribution. D Number and strength of intercellular communication among the FLS, chondrocyte and macrophage cell populations in the indicated groups. The edge width is proportional to the indicated number or strength of intercellular communication. E Western blot of MMP-13 and TNF-α in vehicle-, RANKL- and RANKL + denosumab-treated FLSs (n = 3, biological replicates). F Western blotting of Col2a1 and Col10a1 in chondrocytes incubated with conditioned medium collected from FLSs treated with RANKL or RANKL + denosumab (n = 3, biological replicates). G Western blotting of Arg1 and CD86 in macrophages incubated with conditioned medium collected from FLSs treated with RANKL or RANKL + denosumab (n = 3, biological replicates). H Safranin O/Fast green staining of knee joints in all groups at 4 weeks after RANKL or RANKL + denosumab injection. Scale bar = 200 μm. I The OA severity of the knee joints was evaluated using the OARSI score (n = 6, biological replicates). J Representative H&E staining images showing the infiltration of inflammatory cells and thickness of the synovium (dashed lines) in the indicated group at week 4. Magnified images of the boxed areas are shown in the panel below. Scale bar = 500 μm (upper image); 100 μm (lower image). K Quantification of synovitis score (n = 6, biological replicates). Source data and P values are provided in the Source Data file. Data are presented as median with interquartile range. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (E–G, I, K). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

To verify the effects of RANKL and denosumab on FLSs, mouse FLSs were incubated with RANKL or denosumab for 24 h before RNA was extracted for mRNA sequencing. We identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that were upregulated in RANKL-treated FLSs but were significantly inhibited after denosumab treatment, including MMP-13, MMP-9, ADAMTS5, ADAMTS4 and TNF-α, shown as a heatmap (Supplementary Fig. 6C). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that these DEGs were enriched in the TNF signalling pathway, the NF-κB signalling pathway and the IL-17 signalling pathway (Supplementary Fig. 6D). Furthermore, GO analysis revealed that these DEGs were strongly associated with inflammatory response, osteoclast differentiation, cellular response to interleukin-1 and extracellular matrix catabolic enzymes (Supplementary Fig. 6E), indicating that denosumab significantly attenuated RANKL-mediated inflammatory reaction in FLSs. Further western blot and PCR analyses also confirmed that MMP-13 and TNF-α expression levels in mouse FLSs were significantly increased by RANKL, while these changes were abolished in denosumab-treated FLSs (Fig. 4E and Supplementary Fig. 7A). Interestingly, when we treated chondrocytes directly with RANKL, we found that RANKL induced modest but not significant catabolic effects on chondrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 7B–D). Therefore, we speculated that RANKL, and consequently denosumab, are more likely to influence chondrocytes in an indirect manner through FLSs. We harvested conditioned medium (CM) from FLSs after RANKL treatment (RANKL-CM) without or with denosumab (RANKL + denosumab-CM) treatment. Western blotting and PCR demonstrated that RANKL-CM markedly reduced anabolic gene expression (Col2a1) and increased catabolic gene expression (Col10a1) in chondrocytes, while RANKL + denosumab-CM significantly reversed these changes (Fig. 4F and Supplementary Fig. 7E). In addition, RANKL-CM significantly increased CD86 expression and reduced Arg1 expression to induce M1 macrophage polarisation. Similarly, these effects were markedly reversed by RANKL + denosumab-CM, as demonstrated by western blotting and immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 4G and Supplementary Fig. 7F). Meanwhile, a transwell assay also showed that RANKL-CM induced the migration ability of macrophages, which was substantially inhibited by RANKL + denosumab-CM (Supplementary Fig. 7G). To further consolidate our conclusion in vivo, we injected RANKL with or without denosumab into the mouse knee joints once a week for 4 weeks. Safranin-O/Fast Green staining showed mild cartilage surface erosion in the RANKL-treated knees, a typical sign of early OA, but this was attenuated by denosumab treatment, in line with changes in the OARSI score (Fig. 4H, I). H&E staining showed that the synovial lining layer was thickened and had higher synovitis scores in RANKL-treated knees but not in denosumab-treated knees compared to vehicle (Fig. 4J, K).

In conclusion, we validated the proinflammatory function of RANKL on FLSs, which possibly indirectly induces chondrocyte catabolism and M1 macrophage polarisation, thereby promoting OA progression. These effects were significantly attenuated by denosumab.

FSTL1 expression in FLSs was strongly associated with DMM-induced OA progression but was significantly down-regulated by denosumab treatment

Next, we focused on the DEGs in the FLS cluster. We identified DEGs that were upregulated in the DMM group but were significantly inhibited after denosumab treatment. GO analysis showed that these DEGs were inflammation-related functional genes, such as regulation of inflammatory response, leucocyte migration involved in inflammatory response, leucocyte aggregation, chronic inflammation response and leucocyte cell−cell adhesion (Fig. 5A). Among them, follistatin-like protein 1 (FSTL1) was the most significantly expressed gene in the FLS cluster (Fig. 5B–D). IHC staining confirmed the presence of higher amounts of FSTL1 on the SM of DMM-induced mice compared to the sham group, while this increase was significantly attenuated by denosumab treatment (Supplementary Fig. 8). Furthermore, co-immunofluorescence staining of FSTL1 with the FLS marker ColVI revealed that the percentage of FSTL1+ ColVI+ / ColVI+ was significantly reduced in the DMM + denosumab group compared to DMM controls (Fig. 5E). Previous studies demonstrated that FSTL1 is a biomarker of joint damage in OA patients21, and the levels of this protein correlate with OA severity (assessed by Kellgren–Lawrence [KL] and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities arthritis index [WOMAC] scores)22. In our work, we found that FSTL1 markedly upregulated proinflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β, MMP-13, ADAMTS5) in FLSs and cartilage catabolic factors (Col10a1, MMP-13, ADAMTS5) in chondrocytes, but these were both significantly attenuated by denosumab (Supplementary Fig. 9A–D). Moreover, FSTL1 significantly enhanced macrophage migration, which was substantially blocked by denosumab (Supplementary Fig. 9E). In summary, these data suggest that FSTL1 expression in FLSs is positively correlated with OA progression and confirmed that denosumab rescues OA cartilage degeneration by targeted downregulation of FSTL1 in FLSs.

A GO analysis of the DEGs in FLS clusters, based on scRNA-seq. GO enrichment analysis was identified using a two-sided hypergeometric test. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Terms with an adjusted P-value (FDR) < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. B Heatmap depicting the DEGs in FLS clusters among the Sham, DMM and DMM + denosumab groups, based on scRNA-seq. C Violin plots showing the expression levels of FSTL1 in each cell cluster among the Sham, DMM and DMM + denosumab groups. D Cells are coloured in the UMAP map according to FSTL1 gene expression levels. E Representative co-immunostaining of ColVI (red) and FSTL1 (green) in synovial membrane of sham, DMM and DMM + denosumab mice, counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm. Representative images are from three independent experiments.

Denosumab inhibited activation of RANKL-induced TRAF6/NF-κB pathways in FLSs

To further clarify the mechanism by which denosumab regulates FSTL1 expression in FLSs, KEGG pathway enrichment was performed. Results showed that DEGs in FLSs were highly enriched in the TNF and NF-κB signalling pathways (Fig. 6A), which play important roles in synovitis and OA pathobiology23,24. Therefore, we focused on the expressions of these key factors involved in the NF-κB and TNF signalling pathways after RANKL or RANKL + denosumab treatment. Notably, the expression of FSTL1, TRAF6 and phosphorylated IκBα were significantly increased after stimulation with RANKL (Fig. 6B). Additionally, RANKL increased the expression of p50 and p65 in the SM (Supplementary Fig. 10A). Moreover, incubation of FLSs with RANKL in vitro upregulated the expression of total p50 and p65 and their nuclear co-localisation (Fig. 6B, C). However, denosumab treatment reversed all these effects of RANKL induction. To demonstrate whether denosumab participated in TRAF6 interaction with RANK after stimulation with RANKL, Co-IP experiments were performed. As shown in Fig. 6D, TRAF6 was clearly bound to RANK after stimulation of FLSs with RANKL; however, this effect was abolished by denosumab treatment. Thus, we speculated that denosumab prevents RANKL from binding to the RANK–TRAF6 receptor complex, thereby inhibiting FSTL1 expression in FLSs via the NF-κB pathway.

A KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs, based on scRNA-seq. KEGG pathway enrichment was identified using a two-sided hypergeometric test. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Terms with an adjusted P-value (FDR) < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. B Western blot analysis of FSTL1, TRAF6, IκB, phosphorylated IκB, p65 and p50 proteins in FLSs. Cells were stimulated with RANKL or RANKL + denosumab for 24 h (n = 3, biological replicates). C Western blot analysis of p65 and p50 proteins in the cytoplasm and nucleus of FLSs. Cells were stimulated with RANKL or RANKL + denosumab for 24 h. Cyto, cytoplasm; Nuc, nucleus (n = 3, biological replicates). D Representative co-immunoprecipitation analyses. Protein lysates of FLSs were immunoprecipitated with anti-TRAF6 or non-specific (ns) IgG after stimulation with RANKL, or RANKL + denosumab. The pulldown was subjected to immunoblotting analysis against RANK of the coimmunoprecipitated protein and equal amounts of the total protein lysates (input). Representative images are from three independent experiments. E Western blot analysis of FSTL1, TRAF6, IκB, phosphorylated IκB, p65 and p50 proteins in the indicated FLSs (n = 3, biological replicates). F Western blot analysis of p65 and p50 proteins in the cytoplasm and nucleus of indicated FLSs (n = 3, biological replicates). G Schematic diagram of RANK/TRAF6/FSTL1-mediated NF-κB signalling regulated by RANKL. Created in BioRender. Hu, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/vva2i57. H Representative immunofluorescence images of p65 (green) and p50 (red) in the indicated FLSs. Blue: DAPI showing total FLSs. Scale bar = 100 μm. Representative images are from three independent experiments. I Western blotting analysis of ADAMTS5, MMP-13 and TNF-α in the indicated FLSs (n = 3, biological replicates). Source data and P values are provided in the Source Data file. Data are presented as median with interquartile range. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons (B, C, E, F). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

In order to verify the function of this signalling pathway, TRAF6 siRNA and BAY11-7082, an NF-κB inhibitor, were introduced to FLSs. We found that the expression of TRAF6 was significantly downregulated by TRAF6 siRNA compared with NC siRNA (Supplementary Fig. 10B, C) and either TRAF6 siRNA or BAY11-7082 markedly suppressed the expression of FSTL1 and phosphorylated IκBα induced by RANKL (Fig. 6E). Moreover, RANKL-induced total p50 and p65 expression and nuclear translocation were also substantially inhibited by TRAF6 siRNA and BAY11-7082 (Fig. 6E, F, H and Supplementary Fig. 10D). These results indicated that RANKL-regulated FSTL1 expression depended exclusively on RANK/TRAF6/NF-κB signalling, which was abolished by denosumab (Fig. 6G).

To further clarify the pro-inflammatory and chondrocyte catabolic effects of the TRAF6/FSTL1 axis, we knocked down the expression of TRAF6 and FSTL1 in FLSs, which were subsequently incubated with RANKL (Supplementary Fig. 11A, B). The results revealed that downregulation of TRAF6 or FSTL1 strongly attenuated the expression of chondrocyte catabolic (MMPs and ADAMTSs) and inflammatory (TNF-α) cytokines induced by RANKL in FLSs (Fig. 6I and Supplementary Fig. 11C).

Together, these results led to the conclusion that the effects of RANKL are mediated via the RANK/TRAF6/NF-κB axis, which upregulates FSTL1, promoting synovitis and chondrocyte catabolism, and thereby inducing OA progression. Denosumab downregulates this signalling axis, thereby attenuating synovial inflammation and subsequent OA development.

Denosumab alleviated synovitis in a larger animal (Beagle) OA model

Based on the therapeutic efficacy of denosumab observed in vitro and in vivo in mice, we used surgical anterior cruciate ligament transection (ACLT)-induced OA in the beagle dog knee as a large animal model (Fig. 7A), which is more comparable to humans25. According to the OARSI canine OA scoring system26, OA-like lesions were grossly observed in the femoral condyle at 2 months after ACLT surgery in a macroscopic view. In contrast, administration of denosumab inhibited AC damage in beagle dogs after ACLT surgery, as shown by a smooth surface and a reduced cartilage score (Fig. 7B). MRI analysis showed that treatment with denosumab protected against cartilage loss as well as the formation of articular hydrops, demonstrated by higher cartilage thickness and reduced effusion-synovitis scores observed in denosumab-treated beagle dogs at 2 months after ACLT surgery (Fig. 7C, D). Safranin-O/Fast Green staining demonstrated that compared with the sham group, the tibial plateau exhibited obvious cartilage damage and proteoglycan loss in the ACLT group. However, the denosumab-treated tibial plateau displayed only minor signs of degeneration and preserved cartilage integrity, effectively alleviating cartilage wear (Fig. 7E, F). H&E staining further showed that denosumab treatment alleviated synovitis, demonstrated by decreased synovial hyperplasia and infiltration of inflammatory cells, when analysed by synovitis scoring in denosumab-treated beagle dogs (Fig. 7E, F). Similarly, we did not observe any obvious morphologic changes in heart, liver, spleen, lung or kidney in denosumab-treated beagle dogs (Supplementary Fig. 12). Because denosumab attenuates OA progression in larger animals, these findings suggest that denosumab has the potential to be used clinically to treat patients with OA.

A Schematic illustration of the surgery and treatment plan in the ACLT-induced OA canine model. Created in BioRender. Hu, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/pbs6sij. B Representative macroscopic images of anterior views of the knee joint isolated from the indicated dog groups at 2 months after ACLT surgery. Yellow arrows indicate articular cartilage damage. Macroscopic cartilage scoring was quantified based on the OARSI scoring system (n = 6, biological replicates). C Representative MRI images of knee joints at 2 months after ACLT surgery in the indicated beagle dogs. Red arrows indicate the effusion of joint cavity and suprapatellar bursa. SAG, the sagittal MRI view of the knee joint. TRA, the transverse axis MRI view of the knee joint. D The medial articular cartilage thickness and effusion-synovitis score were quantified using MRI images (n = 6, biological replicates). E Representative Safranin O/Fast green staining of tibial plateau and H&E staining of synovium among Sham, ACLT and ACLT + denosumab dog groups. Magnified images of the boxed areas are shown in the panel below. Scale bar = 500 μm (upper image); 100 μm (lower image). F Mankin score, OARSI score, and Synovitis score were quantified (n = 6, biological replicates). Source data and P values are provided in the Source Data file. Data are presented as median with interquartile range. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons (B, D,F). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Denosumab alleviated synovitis in OA patients

A randomised placebo-controlled phase 2a trial published in Nature Medicine by Wittoek et al. demonstrated that denosumab delayed hand OA progression27. However, the anatomy of the knee joint is different from that of the hand, so we explored whether denosumab exerted any effects on synovitis by a single-arm clinical trial on knee OA patients. In line with Wittoek et al., we found that OKS, WOMAC and VAS scores decreased gradually after injection compared with baseline, with the most significant improvement observed at the final follow-up (Supplementary Fig. 13A). Moreover, MRI showed that, at baseline, the synovium was obviously thickened and there was a large amount of effusion in the joint cavity and suprapatellar bursa, whereas the manifestations of synovitis were significantly improved at 6 months after systemic injection of denosumab, with significant improvements in Hoffa-synovitis and effusion-synovitis scores (Supplementary Fig. 13B, C). In addition, OA patients who needed total knee arthroplasty were injected with denosumab three weeks before surgery. The synovium near the femoral condyle was then harvested for H&E, IHC staining and western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 14A). Notably, H&E staining demonstrated that the layers of lining cells were remarkably increased, showing villous hyperplasia in OA synovium, whereas only a slight increase of lining cells was observed in denosumab-treated synovium (Supplementary Fig. 14B). Further IHC staining and western blotting confirmed that the release profiles of RANKL, FSTL1, proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) and collagenases (MMP-13, ADAMTS5) within OA synovium were higher than those in OA + denosumab synovium (Supplementary Fig. 14C, D). These data further confirmed our findings in animal models, indicating an important role of FLS-mediated synovitis in OA treatment by denosumab.

Discussion

OA is a complex disease characterized by pathological changes in all joint tissues, including cartilage, subchondral bone, ligaments, menisci, joint capsules, and synovium28,29. A study published in 2020 by Di Chen demonstrated that synovial inflammation is a critical event during the pathological changes of OA in the entire joint12. It is not only the starting factor of joint inflammation, but also causes lesions in other joint tissues such as cartilage and subchondral bone. Consistent with Professor Di Chen, we clearly observed that synovial inflammation at 4 weeks after DMM surgery and this was aggravated over time, occurring earlier than the observed cartilage degradation at 4 weeks and osteophyte formation at 8 weeks post-surgery. Furthermore, by analysing cell–cell interaction based on single-cell RNA sequencing, we found that at 4 weeks after DMM surgery, FLSs were the dominant communication “hub” acting by releasing bone and cartilage-damaging factors such as TNF, IL6, CCL, CSF and MIF. These factors further aggravated cartilage damage and the local inflammatory response. Collectively, our results suggest that synovial inflammation is a critical event in the development of OA, and that FLSs could be a potential target for early clinical intervention.

RANKL is reported to be highly expressed on synovial fibroblasts and induces osteoclasts to resorb bone, as well as expressing MMPs that accelerate cartilage degradation30,31,32. However, it has never been reported that RANKL directly drives synovial inflammation. In the present study, we found that RANKL is mostly upregulated in synovium compared to other joint tissues. Specifically, stimulation of FLSs with pro-inflammatory IL-1β showed that RANKL secretion by FLSs was markedly increased upon stimulation with pro-inflammatory cytokines. On the other hand, stimulation of FLSs with RANKL also modulated the production of inflammatory mediators, suggesting an association between pro-inflammatory cytokines and RANKL in the initiation of OA pathogenesis. Based on this, we directly injected RANKL into mouse knee joints and found that RANKL induced synovitis. Together, our results suggest that the molecular and pathological changes in the synovium during OA progression, including enhanced expression of inflammatory cytokines and development of inflamed, hypertrophied synovial tissues, promote RANKL expression in the synovium, which then induces cartilage-damaging mediators to cause cartilage degeneration.

Previous studies have reported that certain OP treatments attenuate cartilage damage and OA progression in several animal models33,34,35. However, the results of clinical trials using OP treatment have not shown any consistent disease-modifying improvement36,37. Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits bone resorption by binding to RANKL and preventing it from activating NF-κB in monocyte–macrophage–osteoclast lineage cells38. Thus, it is used to treat diseases related to abnormal activation of osteoclasts, such as OP and giant cell tumour of bone39. Recently, it has been reported that denosumab ameliorates abnormal subchondral bone remodelling and thus delays OA progression in a DMM-induced mouse model, as well as improving joint function in hand OA14,27. Consistent with the previous study, our data here proved that denosumab treatment effectively suppressed osteoclast activation and abnormal subchondral bone remodelling in a DMM model. More importantly, denosumab also significantly inhibited synovitis in OA murine models, which is another therapeutic mechanism. Although the temporal relationship between the synovitis and abnormal subchondral bone remodelling is still not known, we suggest that the dual effects of denosumab in inhibiting abnormal subchondral bone remodelling and synovitis are responsible for the protective effect on OA. However, different OA subtypes exhibit different pathologies and respond to treatments differently40. Additionally, confirmation in larger animals is necessary, since their joint structures and loading conditions are more similar to humans.

In this study, we demonstrated that denosumab significantly delayed OA progression in DMM-induced, MIA-induced and aging-induced OA murine models. To further determine the role of denosumab in OA treatment, we used a larger animal model and found that denosumab also exerted a chondroprotective effect in beagle dogs. In addition, MRI showed that, at 1 month after systemic injection of denosumab, the manifestation of synovitis was somewhat alleviated, whereas synovitis significantly improved at 2 months after systemic injection of denosumab. Lastly, we designed a single-arm clinical trial and found that denosumab relieved synovial inflammation and knee joint pain, thus improving the joint function of patients with knee OA. All these effects were mediated via FLS-induced synovitis.

Our results showed that denosumab inhibited synovitis and OA via TRAF6/NF-κB pathway-induced FSTL1. FSTL1 is a secreted extracellular glycoprotein that was first identified as a transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)-inducible protein41. Previous studies have reported that FSTL1 is involved in diverse biological processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation, wound healing, inflammatory response, skeletal muscle growth and fibrosis42,43,44. However, conflicting reports exist regarding the function of FSTL1 in OA. Chaly et al. reported that FSTL1 played an important role in maintaining cartilage homoeostasis by enhancing cell proliferation, survival and anabolic activity in articular chondrocytes44, whereas Hu et al. found that FSTL1 was a serum biomarker that reflected the severity of joint damage and secreted MMPs and inflammatory factors in chondrocytes45. Consistent with the findings reported by Hu et al., our work here demonstrated that FSTL1 markedly upregulated cartilage catabolic and proinflammatory factors such as Col10a1, MMP-13, and ADAMTS5 in chondrocytes and FLSs. Interestingly, stimulation of FLSs with RANKL activated the TRAF6-mediated NF-κB signalling pathway and increased the expression of FSTL1. Furthermore, denosumab, siTRAF6 or siFSTL1 all largely blocked the elevation of FSTL1 and activation of the TRAF6/NF-κB pathway, thereby inhibiting the release of cartilage-damaging and inflammatory mediators induced by RANKL. Thus, we identify FSTL1 as an important downstream effector of the RANK/TRAF6/NF-κB signalling pathway in OA progression.

In conclusion, in this study, we explored the effects and mechanisms of denosumab in knee OA progression. Denosumab could be a viable option for the treatment of OA as well as OP, and FSTL1 is a potential therapeutic target for OA. We found that RANKL is highly expressed in OA FLSs, which then produce degrading enzymes and pro-inflammatory cytokines by activating the RANK/TRAF6/FSTL1-mediated NF-κB pathway, inducing comprehensive effects on the other components of the joint, and contributing to cartilage degradation, synovial hyperplasia, subchondral sclerosis, and OA pain. Denosumab, by targeting RANKL in FLSs, thus attenuates OA progression (Fig. 8). However, tissue-specific knockout animal models, such as RANKL-specific deletion in FLSs using ColVI-Cre RANKLflox/flox or FSTL1-specific deletion in FLSs using ColVI-Cre FSTL1flox/flox, are needed to further elucidate the actions of this pathway and its role in cartilage destruction and synovial inflammation during OA progression. Additionally, based on a randomised placebo-controlled phase 2a trial on the treatment of hand OA with denosumab27, we designed a single-centre prospective study on the treatment of knee OA with denosumab, which is also a single-arm trial. The patients screened were primarily those with degenerative knee OA. While this increases the likelihood of observing targeted therapeutic effects, it limits the generalisability of the results to knee OA patients without inflammatory signs. Furthermore, due to the long half-life of denosumab, which maintains its effect for over six months, the follow-up period for this study was set at six months to adequately observe the clinical efficacy throughout the treatment process. However, whether the symptoms of knee OA patients will remain similarly improved after the blood concentration of denosumab decreases beyond six months requires further long-term follow-up studies. Another limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size, so we opted for pairwise comparisons between time points rather than longitudinal analysis, which introduces certain limitations and may lead to potential biases. In addition, the study population was mainly female (89%), reflecting the situation in the wider patient population, because women are known to be more susceptible than men to the onset and development of OA46. Additionally, compared to male OA patients, female patients often exhibit higher levels of joint inflammation and clinical pain, and more severe joint mobility problems47. While denosumab has historically been used for the treatment of OP in postmenopausal women, it was approved for use in male OP patients in 2023. Combined with our animal data, which included only male mice, rats, and beagles, we conclude that the efficacy of denosumab is not sex specific. However, a large-scale clinical trial recruiting more male patients is needed to strengthen the evidence supporting the beneficial and sex-specific effects of denosumab in knee OA patents.

Methods

Animals

This study does not involve sex-based analysis and sex was not considered in study design, Therefore, in order to control variables, we used only male mice in this study. Approximately one hundred male C57BL/6 J mice at 12 weeks old, twelve male C57BL/6 J mice at 12 months old and eighteen male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (weight 200–225 g) were used as experimental animals, purchased from Beijing SPF Biotechnology Co. Ltd. Animals were housed under standard animal feeding conditions (22 ± 2 °C, 50 ± 10% humidity, 12-hour light/dark cycle) with free access to a conventional rodent chow and autoclaved water. For aging OA mouse models, 12-month-old male C57BL/6 J mice were kept until 18 months of age. Twelve male dogs (beagles), with a mean body weight of 10.0 ± 1.5kg, were purchased from Wuhan Xinzhou Wanqianjiahe Experimental Animal Breeding Farm Co., Ltd. and housed on the first floor of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology Tongji Medical College Laboratory Animal Centre in an open environment.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The levels of RANKL in the joint fluid were measured using a Human TRANCE/TNFSF11/RANKL ELISA Kit (Abclonal, RK00341) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

OA induction and treatment

DMM surgery was performed to create an OA mouse model in C57BL/6 J male mice at 12 weeks of age48. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with pentobarbitalsodium (50 mg/kg), and a longitudinal skin incision was made on the medial side of the right knee. The medial meniscal tibial ligament was transected under a surgical microscope. Mice which underwent the incision without meniscal tibial ligament transection formed the sham group.

Rats were subjected to mono-iodoacetate (MIA; Sigma, MO, USA) to induce OA49. Briefly, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium and received a single intra-articular injection of 3.0 mg/50 μL MIA (in PBS) into the right knee joint using a 31 G insulin syringe. The control group received an equal volume of 0.9% sterile saline into the left knee.

For the canine model, OA was induced by surgical anterior cruciate ligament transection (ACLT)50. Under standard anaesthetic conditions, the anterior cruciate ligament of the right knee joint was transected using a pair of curved scissors and a sham operation was performed on the left knee joint. Bleeding and soft tissue damage were minimised as much as possible. After surgery, the synovium, fasciae, and skin were each sutured in sequence. The contralateral knee served as an internal control. The animals received analgesics and antibiotics during the first 3 days after surgery. Starting 2 days after surgery, the dogs were allowed out every day for 10 min on the patio for daily exercise.

Animals in the treatment group were injected subcutaneously with denosumab (10 mg/kg/week). Meanwhile, animals in the RANKL group were injected subcutaneously with sRANKL (1 mg/kg). The sham group received an equivalent volume of vehicle. All experimental mice were euthanised 4, 8 or 12 weeks after surgery for further analysis.

OA pain analysis

Mouse knee pain was measured using von Frey fibres at 0, 2, 4, and 8 weeks after DMM surgery. Before the test, each mouse was acclimatised on an individual 4 × 3 × 7 cm metal grid (Shanghai Yuyan Instrument Co., LTD., Shanghai, China) for 20 min. Von Frey fibres (Shanghai Yuyan Instrument Co., LTD.) in the range 0.008 to 300 g were used for this assay. According to the “up-down method“51, the plantar surface of the hind paw of each mouse was stimulated with each fibre until the fibre bent for 3 s. X indicates a withdrawal response and O indicates no response. The formula shows that the threshold force causing paw contraction is expressed as the 50% paw contraction threshold: (10[Xr + kδ])/10,000 (Xr = value of the last von Frey fibre used in the sequence (expressed in logarithmic units), k = table value, δ = mean difference of forces between fibres).

Open-field test

Mice were tested in the open field to measure their spontaneous locomotor activity and anxiety-like behaviours. Briefly, each mouse was gently put into an open field box (50 × 50 × 50 cm3), the bottom of the box was mapped by the system. The mice were placed in the central area, habituated to the experimental environment for 30 min before the test and then allowed to move freely for 5 min. Afterwards, the total distance travelled, walking speed, and time duration in the central area were recorded and calculated.

Micro-CT analysis

Mouse knee joints were harvested at 8 weeks after DMM surgery and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 48 h. Micro-CT analyses were performed using a high-resolution micro-CT scanner (Bruker SkyScan 1176, Karlsruhe, Germany) at 9 μm resolution, with a 1 mm aluminium filter, 90 kV voltage, and 273 μA current. NRecon reconstruction software and CT-VOX 3D reconstruction analysis software provided by SkyScan were used for volumetric reconstruction and 3D image generation. The grade of OA progression was analysed based on the micro-CT images52.

Histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC)

After performing micro-CT scanning, knee joints were immersed in 4% PFA overnight, decalcified with 10% EDTA for 4 weeks, and then embedded in paraffin. After embedding, the specimens were sectioned at a thickness of 7 μm from the medial side to the cruciate ligament junction. Safranin O/fast green, H&E and TRAP staining were performed. The Mankin Score or OARSI score was used to evaluate the severity and progression of OA after safranin-O staining53. Factors affecting synovitis score included thickening of the entire synovial membrane, activation of resident cells/synovial stroma and aggregation of inflammatory cells, revealed by H&E staining54. For IHC staining, slides were incubated with primary antibodies: anti-RANK (1:100, Abclonal, A13382), anti-RANKL (1:100, Proteintech, 23408-1-AP), anti-Col2a1 (1:100, Abcam, ab34712), anti-Aggrecan (1:100, Abcam, ab315486), anti-MMP-13 (1:100, Proteintech, 18165-1-AP), anti-ADAMTS-5 (1:100, Boster, A02802-1), anti-FSTL1 (1:100, Proteintech, 20182-1-AP), anti-GDF5 (1:100, Abclonal, A13167). After rinsing twice, sections were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies and photographed under an optical microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan; IX73P1 F).

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescent staining, frozen sections were rewarmed to room temperature, permeabilized with 3‰Triton X-100 at room temperature for 15 minutes, then blocked in 5% bovine serum. After rinsing, slides were incubated with primary antibodies against RANKL (1:100, Proteintech, 23408-1-AP), RANK (1:100, Abclonal, A13382), or ColVI (1:100, Proteintech, 17023-1-AP) overnight at 4°C, then sections were labelled with secondary antibody for 1 h in the dark, and counterstained with DAPI for 10 min and then imaged under a confocal microscope (Nikon A1).

Cells cultured on slides were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature then incubated with a primary antibody against p50 (1:100, Proteintech, 14220-1-AP) or p65 (1:100, Proteintech, 10745-1-AP), CD86 (1:100, Proteintech, 13395-1-AP) or Arg1 (1:100, Affinity Biosciences, DF6657), overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the cells were incubated with a fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody for 1h. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI for 10 min in the dark. Images were acquired under a confocal microscope (Nikon A1).

Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq)

Articular tissues of mice in the sham, DMM and DMM + denosumab treatment groups were isolated and dissociated into single cell suspensions with 100 μg/mL of the enzyme mixture Liberase™ (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 μg/mL DNase I (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA)55. Briefly, a single-cell RNA-Seq library kit v3 was used for cDNA amplification and chromium library construction (10 × Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA). cDNA libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6,000 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with a reading length of 150 bp by the Wuhan Biobank Co. Ltd. The R package Seurat (Version 3.0.2) was used to perform data analysis56. Briefly, a single-cell suspension of 1.8 × 104 cells was examined and filtered (nFeature 6,000, nCount 10,000, percent_mt 0.25) for downstream analysis. Cells were visualised using the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were defined by a P value threshold < 0.05 and log FC > 0.25.

mRNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

Total RNA was isolated from mouse FLSs of Veh, RANKL and RANKL + denosumab treatment groups using Trizol (TaKaRa Bio) and evaluated using an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). An RNA sequencing library was prepared and sequenced by CapitalBio Technology (Beijing, China). The DESeq2 package was used to identify DEGs between groups, and the threshold of adjusted P value was 0.05. Gene ontology (GO) analysis, and Kyoto encyclopaedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis for DEGs were visualized and analysed using the DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8.

Cell isolation, treatment and transfection

FLSs were harvested from 8-week-old mouse knee joints. After euthanising mice, the synovium tissue was dissected and digested in 0.25% trypsin for 30 min, followed by digestion with 0.2% collagenase Type 2 for 6 h57. Then cells were centrifuged and filtered, plated into T25 flasks and cultured with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), and supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ mL) and streptomycin (100 g/mL).

Chondrocytes were harvested from the knee joint articular cartilage of 3-day-old mice. Cartilage samples were harvested, cut up into pieces using a sterile scalpel under a dissection microscope and digested in 0.25% trypsin for 30 min. Then the pieces of cartilage were further digested with 900 U/mL collagenase Type I for 2 h. Dissociated cells were centrifuged and resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ mL) and streptomycin (100 g/mL).

For chondrogenesis, 4.0 × 105 chondrocytes were centrifuged into pellets and then cultured in chondrogenic medium (high-glucose DMEM containing 40 mg/mL L-proline, 0.1 mM dexamethasone, 1% penicillin/ streptomycin, 100 mg/mL sodium pyruvate, 50 mg/mL ascorbate-2-phosphate, 1% ITSp Premix). Before chondrogenic induction, 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) was freshly added to the differentiation medium, which was changed every 3 days. After culturing for 2 weeks, the cell pellets were fixed in 4% PFA and then embedded in paraffin. To evaluate collagen deposition, paraffin sections were stained with alcian blue.

FLSs were cultured in a 6-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well, then transfected with TRAF6 siRNA (siTRAF6) or FSTL1 siRNA (siFSTL1) sequences (GenePharma Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After transfection for 36 h, the culture medium was changed, and the cells were treated with RANKL (50 ng/mL) or denosumab (1 μg/mL) for 24 h.

Conditioned medium

FLSs were seeded into a 6-well plate and incubated with RANKL or RANKL + denosumab for 24 h. The next day, the cells were washed three times with PBS, and the culture medium was changed to serum-free DMEM. After another 24 h, the conditioned medium was collected for further experiments.

Migration assay

To evaluate migration, 1 × 104 RAW 264.7 macrophages (American Type Culture Collection, TIB-71, Manassas, VA, USA) in 150 μL growth medium were plated into the upper chamber of a 24-well Transwell™ plate. RANKL-CM or RANKL + denosumab-CM was added to the lower chamber. After incubating for 12 h, cells in the upper chamber were removed using a swab and cells on the bottom surface of each Transwell™ were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with crystal violet. The number of macrophages that had migrated was observed and quantified under a microscope.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells or tissues using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and cDNA was reverse transcribed using a reverse transcription kit (TaKaRa Bio). TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa Bio) was used for RT-PCR detection. Expression levels were normalised to GAPDH which was used as the internal reference. All primer sequences for RT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Western blotting and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Total protein was harvested from cells or tissues using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) supplemented with phosphatase and proteinase inhibitors, and the concentration was determined by the BCA assay (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Proteins were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a 0.45 μm polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies against the following proteins: RANK (1:1,000, Abclonal, A13382), RANKL (1:1,000, Proteintech, 23408-1-AP), MMP-13 (1:1,000, Proteintech, 18165-1-AP), ADAMTS-5 (1:1,000, Boster, A02802-1), Col2a1 (1:1,000, Bioss, bs-0709R), Col10a1 (1:1,000, Abcam, ab182563), TNF-α (1:1,000, Abclonal, A11534), IL-1β (1:1,000, Affinity Biosciences, AF5103), CD86 (1:1,000, Proteintech, 13395-1-AP), Arg1 (1:1,000, Affinity Biosciences, DF6657), FSTL1 (1:1,000, Proteintech, 20182-1-AP), TRAF6 (1:1,000, Santa Cruz, sc8409), IκB-α (1:2,000, Proteintech, 10268-1-AP), p-IκB-α (1:1000, CST, 2859 T), p-65 (1:1,000, Proteintech, 10745-1-AP), p-50 (1:1,000, Proteintech, 14220-1-AP) and H3 (1:1,000, ab32356, Abcam); GAPDH (1:3,000, Proteintech, 60004-1-Ig) was used as the internal reference. After washing with TBS containing 0.01% Tween 20 (TBST) three times, HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Signals on the membrane were visualized using ECL chemiluminescence.

For immunoprecipitation, cell lysate was precipitated with 5 μL of anti-TRAF6 antibody (Santa Cruz, sc8409) or control IgG for 24 h using magnetic beads. Then the immune complexes were separated by magnetic adsorption and washed twice with PBS. Finally, the immune complexes were boiled for further western blot assays to detect the expression of RANK.

Clinical study design and collection of human synovium samples

The clinical study was performed between August 2021 and December 2025 in Wuhan Union Hospital. The protocol was registered on the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (www.chictr.org.cn, number ChiCTR2200060412), and ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT06357741) and was approved prior to patient recruitment by the Institutional Review Board according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients included in this study signed a written informed consent form and volunteered for the collection and use of their tissue samples (cartilage, synovium, and synovial fluid) in scientific research. In addition, publication of any potentially identifiable images or data, as approved by the Ethics Committee of Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Ethical approval number: 2025-0423). It was designed as a 3 + 3 single-arm Phase I study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of denosumab injection in knee OA patients with OP. This study does not involve sex-based analysis and sex was not considered in the study design. Therefore, for human participants, we did not assign a particular sex. Nine patients were enroled and followed up over three distinct study visits of 1, 3 and 6 months after systemic denosumab injection. The demographic characteristics and clinical status of these patients are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Fifty-six percent of the patients had a high BMI.

Human synovium samples were collected from patients with knee OA who received total knee replacement at the Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College (Wuhan, China) (Supplementary Table 3). We obtained informed consent from all participants in this study, and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed throughout.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS) for knee pain and the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) for knee function. The secondary outcome was the WOMAC for knee function and the rate of adverse events (AEs). WOMAC consists of three sub scores, pain, comprising five items; stiffness, with two items; and functionality, with 17 items. AEs were recorded at each follow-up and described in terms of symptoms, incidence, severity, and relatedness according to the World Health Organization-Uppsala Monitoring Centre causality assessment system58. The severity of AEs was divided into five levels according to the National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE)59. No serious adverse events (AEs), or cases of permanent disability, septic arthritis, or neoplasia were reported at any of the follow-up visits. All AEs were mild and no patients discontinued the trial due to AEs (Supplementary Table 4).

Radiologic outcomes were analysed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) according to the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS), which is a validated semi-quantitative tool to describe OA progression over time60. Thus, the knee is divided into 14 subregional divisions (tibia–medial and lateral, anterior/central/posterior; femoral–medial and lateral, trochlea/central/posterior; patella–medial and lateral) with each region achieving a corresponding score for features of OA. The features assessed in this study were articular cartilage, synovitis and bone marrow lesions (BMLs). All data were collected at intervals of baseline, 1, 3 and 6-months follow-up by an orthopaedic physician with no knowledge of the treatment group.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times and only data from a representative experiment are presented. Data are represented as the median with interquartile range and all statistical analyses and mapping were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). We employed unpaired two-tailed t-test or two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test for statistical analysis between two groups and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test or Kruskal–Wallis test with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. n indicates the number of biologically independent samples, animals per group, or human specimens. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Ethics approval

All animal study designs were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Ethical approval number: 3852).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data of all figures and RNA-seq data of this study are provided in the Source Data File. The scRNA-seq data of this study are provided and accessible through National Genomics Data Center (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix/release/OMIX011832). The study protocol and the information of the volunteers enrolled in the clinical trial are available within the article and its supplementary files. Any additional requests for information can be directed to, and will be fulfilled by the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Glyn-Jones, S. et al. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 386, 376–387 (2015).

Yao, Q. et al. Osteoarthritis: pathogenic signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 56 (2023).

Weinans, H. et al. Pathophysiology of peri-articular bone changes in osteoarthritis. Bone 51, 190–196 (2012).

Scanzello, C. R. & Goldring, S. R. The role of synovitis in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Bone 51, 249–257 (2012).

Cho, Y. et al. Disease-modifying therapeutic strategies in osteoarthritis: current status and future directions. Exp. Mol. Med. 53, 1689–1696 (2021).

Kaneko, H. et al. Synovial perlecan is required for osteophyte formation in knee osteoarthritis. Matrix Biol. 32, 178–187 (2013).

Malfait, A. M. & Schnitzer, T. J. Towards a mechanism-based approach to pain management in osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 9, 654–664 (2013).

Mathiessen, A. & Conaghan, P. G. Synovitis in osteoarthritis: current understanding with therapeutic implications. Arthritis Res Ther. 19, 18 (2017).

Sellam, J. & Berenbaum, F. The role of synovitis in pathophysiology and clinical symptoms of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 6, 625–635 (2010).

Hasegawa, T. et al. Identification of a novel arthritis-associated osteoclast precursor macrophage regulated by FoxM1. Nat. Immunol. 20, 1631–1643 (2019).

Bartok, B. & Firestein, G. S. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol. Rev. 233, 233–255 (2010).

Liao, L. et al. Acute Synovitis after trauma precedes and is associated with osteoarthritis onset and progression. Int J. Biol. Sci. 16, 970–980 (2020).

Lacey, D. L. et al. Bench to bedside: elucidation of the OPG-RANK-RANKL pathway and the development of denosumab. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 401–419 (2012).

Shangguan, L., Ding, M., Wang, Y., Xu, H. & Liao, B. Denosumab ameliorates osteoarthritis by protecting cartilage against degradation and modulating subchondral bone remodeling. Regenerative Ther. 27, 181–190 (2024).

Bendele, A. M. Animal models of osteoarthritis. J. Musculoskelet. neuronal Interact. 1, 363–376 (2001).

Waltereit-Kracke, V. et al. Deletion of activin A in mesenchymal but not myeloid cells ameliorates disease severity in experimental arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 81, 1106–1118 (2022).

van der Kraan, P. M. & van den Berg, W. B. Osteophytes: relevance and biology. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15, 237–244 (2007).

Roelofs, A. J. et al. Joint morphogenetic cells in the adult mammalian synovium. Nat. Commun. 8, 15040 (2017).

Roelofs, A. J. et al. Identification of the skeletal progenitor cells forming osteophytes in osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79, 1625–1634 (2020).

Schäfer, N. & Grässel, S. Targeted therapy for osteoarthritis: progress and pitfalls. Nat. Med. 28, 2473–2475 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Follistatin-like protein 1: a serum biochemical marker reflecting the severity of joint damage in patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 13, R193 (2011).

Ni, S. et al. The involvement of follistatin-like protein 1 in osteoarthritis by elevating NF-kappaB-mediated inflammatory cytokines and enhancing fibroblast like synoviocyte proliferation. Arthritis Res Ther. 17, 91 (2015).

Napetschnig, J. & Wu, H. Molecular basis of NF-kappaB signaling. Annu Rev. Biophys. 42, 443–468 (2013).

Rigoglou, S. & Papavassiliou, A. G. The NF-kappaB signalling pathway in osteoarthritis. Int. J. Biochem. cell Biol. 45, 2580–2584 (2013).

Deng, R. et al. Chondrocyte membrane-coated nanoparticles promote drug retention and halt cartilage damage in rat and canine osteoarthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadh9751 (2024).

Cook, J. L. et al. The OARSI histopathology initiative – recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the dog. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 18, S66–S79 (2010).

Wittoek, R., Verbruggen, G., Vanhaverbeke, T., Colman, R. & Elewaut, D. RANKL blockade for erosive hand osteoarthritis: a randomized placebo-controlled phase 2a trial. Nat. Med. 30, 829–836 (2024).

Loeser, R. F., Collins, J. A. & Diekman, B. O. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 12, 412–420 (2016).

Zhen, G. et al. Inhibition of TGF-β signaling in mesenchymal stem cells of subchondral bone attenuates osteoarthritis. Nat. Med. 19, 704–712 (2013).

Komatsu, N. & Takayanagi, H. Mechanisms of joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis - immune cell-fibroblast-bone interactions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 18, 415–429 (2022).

Takayanagi, H. Osteoimmunology: shared mechanisms and crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 292–304 (2007).

Croft, A. P. et al. Distinct fibroblast subsets drive inflammation and damage in arthritis. Nature 570, 246–251 (2019).

Kadri, A. et al. Inhibition of bone resorption blunts osteoarthritis in mice with high bone remodelling. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1533–1538 (2010).

Jones, M. D. et al. In vivo microfocal computed tomography and micro-magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of antiresorptive and antiinflammatory drugs as preventive treatments of osteoarthritis in the rat. Arthritis rheumatism 62, 2726–2735 (2010).

Strassle, B. W. et al. Inhibition of osteoclasts prevents cartilage loss and pain in a rat model of degenerative joint disease. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 18, 1319–1328 (2010).

Bingham, C. O. 3rd et al. Risedronate decreases biochemical markers of cartilage degradation but does not decrease symptoms or slow radiographic progression in patients with medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee: results of the two-year multinational knee osteoarthritis structural arthritis study. Arthritis rheumatism 54, 3494–3507 (2006).

Garnero, P. et al. Relationships between biochemical markers of bone and cartilage degradation with radiological progression in patients with knee osteoarthritis receiving risedronate: the Knee Osteoarthritis Structural Arthritis randomized clinical trial. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 16, 660–666 (2008).

McClung, M. R. et al. Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 821–831 (2006).

Ferrari, S. & Langdahl, B. Mechanisms underlying the long-term and withdrawal effects of denosumab therapy on bone. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 19, 307–317 (2023).

Lv, Z. et al. Molecular classification of knee osteoarthritis. Front. cell developmental Biol. 9, 725568 (2021).

Shibanuma, M., Mashimo, J., Mita, A., Kuroki, T. & Nose, K. Cloning from a mouse osteoblastic cell line of a set of transforming-growth-factor-beta 1-regulated genes, one of which seems to encode a follistatin-related polypeptide. Eur. J. Biochem. 217, 13–19 (1993).

Sundaram, G. M. et al. See-saw’ expression of microRNA-198 and FSTL1 from a single transcript in wound healing. Nature 495, 103–106 (2013).

Chaly, Y., Marinov, A. D., Oxburgh, L., Bushnell, D. S. & Hirsch, R. FSTL1 promotes arthritis in mice by enhancing inflammatory cytokine/chemokine expression. Arthritis rheumatism 64, 1082–1088 (2012).

Chaly, Y. et al. Follistatin-like protein 1 regulates chondrocyte proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 1467–1473 (2015).

Hu, P. F., Ma, C. Y., Sun, F. F., Chen, W. P. & Wu, L. D. Follistatin-like protein 1 (FSTL1) promotes chondrocyte expression of matrix metalloproteinase and inflammatory factors via the NF-κB pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23, 2230–2237 (2019).

Prieto-Alhambra, D. et al. Incidence and risk factors for clinically diagnosed knee, hip and hand osteoarthritis: influences of age, gender and osteoarthritis affecting other joints. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 1659–1664 (2014).

Boer, C. G. et al. Deciphering osteoarthritis genetics across 826,690 individuals from 9 populations. Cell 184, 4784–4818.e4717 (2021).

Glasson, S. S., Blanchet, T. J. & Morris, E. A. The surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) model of osteoarthritis in the 129/SvEv mouse. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15, 1061–1069 (2007).

Park, E. H. et al. TissueGene-C induces long-term analgesic effects through regulation of pain mediators and neuronal sensitization in a rat monoiodoacetate-induced model of osteoarthritis pain. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 31, 1567–1580 (2023).

Marijnissen, A. C., van Roermund, P. M., TeKoppele, J. M., Bijlsma, J. W. & Lafeber, F. P. The canine ‘groove’ model, compared with the ACLT model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 10, 145–155 (2002).

Chaplan, S. R., Bach, F. W., Pogrel, J. W., Chung, J. M. & Yaksh, T. L. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J. Neurosci. methods 53, 55–63 (1994).

Chan, W. P. et al. Osteoarthritis of the knee: comparison of radiography, CT, and MR imaging to assess extent and severity. Ajr. Am. J. Roentgenol. 157, 799–806 (1991).

Pritzker, K. P. et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 14, 13–29 (2006).

Krenn, V. et al. Grading of chronic synovitis–a histopathological grading system for molecular and diagnostic pathology. Pathol., Res. Pract. 198, 317–325 (2002).

Zhang, F. et al. Defining inflammatory cell states in rheumatoid arthritis joint synovial tissues by integrating single-cell transcriptomics and mass cytometry. Nat. Immunol. 20, 928–942 (2019).

Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F. & Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 495–502 (2015).

Futami, I. et al. Isolation and characterization of multipotential mesenchymal cells from the mouse synovium. PloS one 7, e45517 (2012).

Mouton, J. P., Mehta, U., Rossiter, D. P., Maartens, G. & Cohen, K. Interrater agreement of two adverse drug reaction causality assessment methods: A randomised comparison of the Liverpool Adverse Drug Reaction Causality Assessment Tool and the World Health Organization-Uppsala Monitoring Centre system. PloS one 12, e0172830 (2017).

Basch, E. et al. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: results of a questionnaire-based study. Lancet Oncol. 7, 903–909 (2006).

Hunter, D. J. et al. Evolution of semi-quantitative whole joint assessment of knee OA: MOAKS (MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score). Osteoarthr. Cartil. 19, 990–1002 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to all patients who participated in this trial. We thank Ling Qin (University of Pennsylvania) and Xianrong Zhang (Southern Medical University) for thoughtful discussion; Ke Zhang for technical assistance; Qi Wang (School of Public Health, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology) for statistical analysis. This work was supported by funds from the Department of Science and Technology of Hubei Province (No. 2023BCB089) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82372465 to W.T., No. 82402818 to W.L., No. 81672235 to H.T., No. 82002300 to Z.D.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.T. and H.T. designed and supervised the project and revised the manuscript. Y.H. and C.M. performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. W.C. and S.L. analysed and interpreted data. D.X., H.X., and H.L. collected the clinical data. D.S., W.L., Z.D., J.W., Z.H., W.X., Z.S. and Y.L. verified the underlying data. All authors reviewed and approved the final document.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions