Abstract

The oxygen incorporation and evolution reactions (OIR/OER) at air electrodes are key challenges limiting the performance of reversible solid oxide cells (SOCs). Surface modification using binary oxides has emerged as a promising strategy to enhance OIR/OER kinetics, with PrOx as a popular choice of the modification layer. However, the mechanisms behind this improvement of reaction kinetics remain unclear. In this study, we combine insights from electrochemical measurements and operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy to reveal that interfacial charge transfer plays a pivotal role in enhancing the OIR/OER activity in La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3−δ (LSCF) with PrOx surface modification. The charge transfer increases the hole concentration in LSCF, which can be quantitatively correlated with accelerated OIR/OER kinetics (up to ~70 times enhancement) over a broad range of oxygen chemical potential. We further demonstrate this mechanism in realistic SOCs devices, showing enhanced performance in both fuel cell and electrolysis modes. Our work provides critical insights into the role of interfacial charge transfer and defect chemistry in surface-modified SOCs electrodes, offering a pathway to optimize SOCs performance through surface modifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solid oxide cells (SOCs) have garnered significant attentions as a promising candidate for sustainable electrochemical energy conversion, offering potential pathways to cleaner energy solutions1,2.However, oxygen incorporation/evolution reactions (OIR/OER) at the air electrodes remain as one of the key bottlenecks, limiting the performance of high-efficiency SOCs3,4. To effectively enhance OIR/OER kinetics, surface modification with binary oxides has been developed as a useful strategy to accelerate reaction kinetics and improve the overall device efficiency5,6,7. However, the specific mechanisms responsible for the enhanced kinetics remain elusive, which leaves most of the optimization efforts still largely empirical8,9. This lack of understanding significantly hinders the development of guiding principles for leveraging surface modification to enhance the performance of SOCs. Establishing a mechanistic framework is essential to unlock the full potential of surface engineering in advancing SOCs technology.

Previously, several studies have proposed the changes in vacancy formation energies and surface band bending as the key reason for enhanced surface kinetics from the surface modification10,11,12. To evaluate the effectiveness of surface modification on various binary oxides, Nicollet et al. pioneeringly introduced the concept of the Smith acidity of surface oxides as a descriptor for the magnitude of induced effects12. Furthermore, Siebenhofer et al.13 discovered that acidic adsorbates on electrode surfaces induce surface dipoles on the surface, which alters the work function of electrodes and influences OIR/OER performance14. Therefore, it is now widely believed that performance improvements from surface modification are primarily attributed to alterations in the electronic structure of electrodes. However, how these changes in electronic structure or defect chemistry directly affect the OIR/OER kinetics and reaction mechanisms of electrodes remains an open question. Specifically, a key challenge is to quantify changes in electronic structure under various operating conditions and to establish a direct, quantitative relationship between defect chemistry (i.e., oxygen vacancy concentration) and surface kinetics. Moreover, in most of the previous studies, the defect chemistry of the surface modification layer itself was assumed to be invariant, which is not true for some binary oxides that show a superior enhancement effect. For example, PrOx has been widely used as a promising candidate material that can greatly enhance the OIR/OER kinetics15,16, while our previous study has shown that PrOx can undergo large change in defect concentrations in response to electrochemical driving forces17. Therefore, we believe that it is also important to take into account the potential effect of interfacial defect chemical equilibrium for understanding the mechanisms of surface modifications in enhancing oxygen exchange kinetics.

To systematically elucidate the mechanism of OIR/OER kinetics enhancement induced by surface modifications, in this work, we combined insights from carefully-designed electrochemical measurements and operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and paid special attention to the role of interfacial charge transfer. Using well-controlled thin film model systems with simplified microstructures, we use La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3-δ (LSCF) as an example of SOCs air electrode and PrOx as the surface modification layer. Contrary to previous understanding, we find that the surface modification layer itself can change its defect chemistry in response to varying oxygen chemical potential. However, no matter how the defect chemistry of PrOx changes, we can pinpoint the electron transfer from LSCF to PrOx as the main factor responsible for improved OIR/OER kinetics in a wide range of oxygen chemical potential. The interfacial charge transfer effectively increases the hole concentration in LSCF, which can be quantitatively correlated with enhanced OIR/OER kinetics. The applicability of this mechanism was further validated in realistic reversible SOCs devices, where PrOx surface modifications led to significant performance improvements in both fuel cell and electrolysis modes. Interestingly, the extent of performance enhancement varied depending on the operational atmosphere and/or operation mode, which can be attributed to differences in interfacial charge transfer modulated by the oxygen chemical potential at the air electrode. Our findings conclude that interfacial charge transfer is the key to activity enhancement via surface modification, offering a new framework for optimizing SOCs air electrodes to boost both efficiency and operational flexibility.

Results and discussion

LSCF modified with PrOx thin films as a model electrocatalyst

To investigate the effects of the surface modification on OIR/OER mechanisms, we fabricated model thin film cells using epitaxial thin films of LSCF as working electrodes. PrOx then was deposited onto the surface of the LSCF thin film as the surface modification layer. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) results show that the deposited PrOx surface modification layer has uniform morphology, which most likely forms a conformal coating on the LSCF surfaces (Fig. S1 in Supplementary Information (SI)). We also used X-ray diffraction (XRD) to confirm that the crystal structure of LSCF was not largely affected by the PrOx surface modification layers (Fig. S4 in SI). As described in our previous work17, the thin film working electrodes were contacted via an underlying platinum grid to promote a uniform oxygen chemical potential (\({\mu }_{O}\)) under bias, and a platinum reference electrode defined the reference potential for \({\mu }_{O}\). The structure of the model electrochemical cells is shown in Fig. 1a. With this model electrochemical cell, we can simultaneously control the ambient oxygen partial pressure (pO2) and the applied bias (η), both of which fundamentally influence the defect concentration in the material (via the change of oxygen chemical potential \({\mu }_{O}\)). The oxygen chemical potential in the electrode, relative to 1 bar of oxygen, is given by the Nernst equation:

which the \({p{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{2}^{0}\) is the standard oxygen pressure (1 bar), while symbols \({k}_{B}\) and \(T\) represent the Boltzmann constant and temperature, respectively.

a Nyquist plot of LSCF modified with a 1 nm PrOx thin film, with a schematic of the electrochemical model. b Area specific resistance and (c) chemical capacitance of LSCF (100 nm) and PrOx (80 nm), as well as LSCF modified with 1 nm, 5 nm, and 10 nm of PrOx under 0.21 atm pO2 with different biases at 700 °C. d Calculated chemical capacitance of LSCF modified with 1 nm, 5 nm, and 10 nm of PrOx, based on a linear combination of the volumetric chemical capacitance of PrOx and LSCF. The lines represent calculated results, while the dots depict experimental test results. Error bars are obtained from the standard variation from three measurements on different electrodes.

We conducted electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements and analyzed the results using the equivalent circuit model shown in Fig. 1a. We show that the interfacial capacitance is negligible compared with the chemical capacitance (Cchem) of the LSCF/PrOx electrodes, which means that the possible effect of interfacial space charge layers may be negligible (Fig. S5 and S6 in SI)18. Fig. 1b shows the area specific resistance (ASR) of LSCF (100 nm) and PrOx (80 nm), as well as LSCF modified with 1 nm, 5 nm, and 10 nm of PrOx with different \({\mu }_{O}\) at 700 °C (details of EIS fitting procedure are shown in Fig. S5 and Fig. S6 in SI). We found that ASR decreases as the PrOx surface modification thickness increases, regardless of the variation in oxygen chemical potential. The ASR measured under varying pO2 conditions and temperatures shows that despite a reduction in the absolute ASR values following the modification, the apparent activation energy remained largely unaffected (Fig. S7 in SI), although we would like to stress that this is not the “true” activation energy under fixed defect concentration19. Nevertheless, we observed an increase in activation energy with increasing pO2, consistent with previously reported results14,20,21. Fig. 1c shows the values of chemical capacitance from EIS (Fig. S5 in SI), which provided a direct measure of defect concentrations22. Compared to the unmodified LSCF thin film, modifying the LSCF electrode with PrOx of varying thicknesses shows a different dependence on the oxygen chemical potential, where the phase transition point at ~−0.1 eV can be seen for thick PrOx layers17. This change occurs because the defect concentrations in both PrOx and LSCF contribute to the overall chemical capacitance. Therefore, we attempted to quantify the overall chemical capacitance by linearly combining the chemical capacitance per unit volume of PrOx and LSCF, as shown below:

where \({C}_{i}^{V}\) and \({V}_{i}\) (i = LSCF, PrOx or LSCF/PrOx), represent volumetric chemical capacitance and the volume in the thin film of species \(i\), respectively.

The calculated results (lines) are highly consistent with the experimental results (dots), as shown in Fig. 1d. Therefore, after the surface modification, the chemical capacitance reflects the combined contribution of defect species from both LSCF and PrOx. In LSCF, the capacitance is primarily governed by electron holes at low effective pO2, and by oxygen vacancies at high effective pO2. In PrOx, it is likely dominated by holes under reducing conditions, and by oxygen interstitials under oxidizing conditions, consistent with the observed phase transition of PrOx17. This finding already suggests that we need to consider the defect chemistry of the surface modification itself, which might have a strong impact on the OIR/OER kinetics.

Changes in reaction orders of OIR/OER as indicators of modification effects

We measured the current density, which directly reflects the OIR/OER kinetics, of LSCF, PrOx and LSCF electrodes modified with PrOx at various applied biases (−0.2 to 0.2 V) under different oxygen partial pressures at 700 °C (Fig. S8 in SI). Following our previous work17 as well as the previous work by Fleig et al.23,24 and Guan et al.25,26, the current density j of OIR/OER electrochemical reactions can be understood using the equation below,

where the \({j}_{0}\) is the pre-factor of the current density. \({\nu }_{a}\) and \({\nu }_{p}\) represent the “true” reaction order associated with oxygen activity \({a{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{2}\) (which is related to \({\mu }_{O}\)) and pO2, respectively, decoupling the effects of \({a{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{2}\) and pO2. χ represents the surface potential at the oxide/gas interfaces. For most perovskites, such as La0.6Sr0.4FeO3-δ and La0.6Sr0.4CoO3-δ, χ remains relatively stable under varying biases and pO2 in an oxygen atmosphere24,27. Additionally, our previous work showed that the surface potential of PrOx barely changed with biases and pO217. Therefore, in this study, we simplify Eq. (3) by assuming that the χ is relatively unaffected by changes in bias and pO2. In our analysis, we assume that χ is insensitive to variations in oxygen chemical potential, which is supported by the AP-XPS results (Fig. S15 in SI). Therefore, χ influences only the intercept but not the slope of the logarithmic form of Eq. (3). Consequently, the specific value of χ does not affect the extraction of kinetic orders.

After excluding the influence of surface potential, we focus on disentangling this complex reaction mechanism by analyzing the independent effects of defect concentration and pO2 on surface kinetics. To assess the impact of each factor separately, we first fix \({\mu }_{O}\) values and examine the influence of pO2 on surface kinetics. Specifically, we evaluate the effect of pO2 on surface kinetics at \({\mu }_{O}\) = −0.2 eV (corresponding to the SOFC mode or under a cathodic bias) and 0.2 eV (corresponding to the SOEC mode or under an anodic bias), as shown in Fig. 2a. The slope of log j vs log pO2 plot represents the reaction order with respect to pO2 (denoted as \({\nu }_{p}\)), reflecting the sensitivity of surface kinetics to the changes in pO2. We applied the same procedure across different \({\mu }_{O}\) ranges (Fig. S7 and S8 in SI) and summarized the results in Fig. 2b. Under cathodic bias, \({\nu }_{p}\) increased from around 0.5 to roughly 1 after modification, indicating an enhanced influence of pO2 on surface kinetics.

a Oxygen pressure dependence of current density of LSCF and LSCF modified with PrOx electrodes with fixed oxygen chemical potentials of −0.2 and 0.2 eV. b Reaction order of oxygen partial pressure pO2 obtained by the fitting results in (a) and the oxygen pressure dependence of current density at fixed oxygen chemical potential range of −0.6 ~ −0.1 eV in Fig. S10 and −0.1 ~ 0.3 eV in Fig. S11 in SI. c Oxygen activity dependence of current density of LSCF and LSCF modified with PrOx electrodes with a fixed oxygen pressure of 1 bar at 700 °C. The symbols indicate experimental data, while the dotted lines represent linear fitting results. (d) The reaction order of oxygen activity obtained by using the fitting results in (c) and the oxygen activity dependence of current density at fixed pO2 range of 0.1 ~ 1000 mbar in Fig. S9 in SI. Red shading indicates the fuel cell mode, and blue shading indicates the electrolysis mode.

Such a change in reaction order can imply a shift in the underlying reaction mechanism. Based on the interpretations of the “true” reaction order under isolated pO2 variation reported in the literature, a value of 1/2 corresponds to a mechanism where the rate-determining step (RDS) occurs twice in the overall surface exchange process, whereas a reaction order of 1 suggests that the RDS occurs only once17,26. Therefore, the increase of \({\nu }_{p}\) from 0.5 to 1 reflects a reduced number of RDS repetitions. On the contrary, under anodic bias, the modification has a negligible effect on \({\nu }_{p}\), which remains around zero. Therefore, we reach the conclusion that the PrOx surface modification primarily affects the dependence of surface kinetics on pO2 under cathodic bias. In the case of anodic bias, pO2 has minimal impact on the effects of surface modification, with defect concentration changes predominantly governing the changes in surface kinetics. This analysis contrasts with conventional methods that directly correlate current or impedance with pO2, where the influence of defect concentration cannot be decoupled. By fixing \({\mu }_{O}\), the approach we used above can isolate the effect of pO2, enabling a more physically meaningful interpretation of the kinetic response. To analyze the influence of defect chemistry, we employed a similar method to investigate the relationship between oxygen activity and current density at a fixed pO2 of 1 bar, as shown in Fig. 2c. The slopes of the curves in this figure indicate the reaction order of oxygen activity \({\nu }_{a}\). We also applied the same procedure under different pO2 conditions (Fig. S9 in SI) and summarized the results in Fig. 2d. For the bare LSCF electrode, \({\nu }_{a}\) remains essentially unchanged regardless of the pO2 variation. However, with the increasing thickness of the surface PrOx modification layer, \({\nu }_{a}\) increases, which is more appreciable at high pO2. The change of reaction order related to oxygen chemical potential means that after PrOx modification, the influence of defect concentration on surface kinetics can be amplified, particularly under the oxygen partial pressure conditions that are typical of SOCs air electrodes (for both SOFC and SOEC modes, i.e., under both cathodic and anodic biases). This finding suggests that the mechanisms responsible for the enhancement of OIR/OER kinetics must involve the alteration of defect concentration induced by PrOx surface modification. Based on the previous work of Schmid et al.24,28, the hole/oxygen vacancy concentration is in particular important for the OER/OIR activity of perovskite-based electrodes. Therefore, the results from electrochemical measurements inspire us to take a deep dive into the change of bulk defect concentrations of the LSCF/PrOx electrode compared with the pristine LSCF electrode. It is highly likely that the key defect concentration (e.g., holes or oxygen vacancies) can be greatly changed upon a surface modification layer being deposited on LSCF electrodes.

Quantifying charge transfer between PrOx and LSCF

To further investigate the effects of surface modification on the defect concentration and potential changes in the electronic structures, we conducted operando XAS to directly measure the valence state of Pr as a function of oxygen chemical potential. The details of the operando XAS testing system can be found in Fig. S12 of SI.

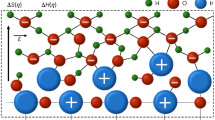

Fig. 3a shows the operando XAS results for a single phase PrOx electrode (with 80 nm thickness) and a LSCF electrode (100 nm) modified with 5 nm of PrOx, measured at 700 °C under an oxygen partial pressure of 1 mbar, with different anodic and cathodic biases. For PrOx grown directly on YSZ substrates, anodic biases readily induce the formation of more oxidized Pr4+, while cathodic biases favor the reduction to Pr3+, consistent with our previous findings17. Interestingly, for the LSCF thin film electrode surfaces modified with PrOx, Pr predominantly exists in the reduced Pr3+ state even at 0 V, i.e., without applying any cathodic bias. This reduced state persists even with a significant anodic bias of 0.5 V, while under cathodic biases nearly all Pr cations were converted to Pr3+. This behavior clearly demonstrates that using PrOx as a surface modification layer behaves differently compared to single-phase PrOx, which highlights the potential interface charge transfer between LSCF and PrOx, i.e., electrons (negative charge) transfer from LSCF to the PrOx surface modification layer. We quantified the Pr oxidation state at different oxygen chemical potentials, as shown in Fig. 3b, by reconstructing the spectra at intermediate biases through a linear combination of those obtained under the most negative and positive biases, as described in the reference29. These changes in the Pr oxidation state directly reflect changes in the defect concentrations within PrOx, confirming that charge transfer occurs between PrOx and LSCF. Specifically, electrons transfer from LSCF to PrOx leads to a more reduced state of PrOx deposited on the LSCF surface. This charge transfer can be quantified by quantifying the difference in Pr oxidation states between single-phase PrOx and LSCF/PrOx bi-layer. We emphasize that this comparison is not between bare LSCF and PrOx-modified LSCF, but rather between single-phase PrOx and LSCF/PrOx bilayers. The difference in Pr oxidation state between the two configurations directly reflects the extent of electron transfer from the underlying LSCF to the PrOx surface layer. It is evident that the amount of this charge transfer varies with changes in the oxygen chemical potential, with more charge transfer occurring under more cathodic bias.

a Operando Pr M4,5-edge XAS spectra of a single-phase PrOx (80 nm) and an LSCF (100 nm) modified with 5 nm PrOx thin film electrode measured under different applied biases at 700 °C and with an atmospheric oxygen pressure of 1 mbar. b Fraction of Pr3+ in LSCF modified with PrOx and single-phase PrOx electrodes calculated using the linear combination of reference spectra of Pr3+ and Pr4+29. c The hole concentration in LSCF and the first 5 nm from the LSCF/PrOx interface in PrOx modified LSCF at various oxygen chemical potentials is calculated under the assumption that charge transfer impacts only the first 5 nm from the interface and is uniformly distributed within this region. The gray dashed line represents the change in the hole concentration after modification which is calculated from (b). d Current density versus electron hole concentration. The hole concentration of LSCF was calculated based on the defect chemistry model of LSCF bulk (as shown in Fig. S14a in SI), while the hole concentration of LSCF modified with PrOx was calculated by equation (4).

To quantitatively determine the concentration changes in LSCF caused by charge transfer, it is first necessary to identify the thickness range affected in LSCF. If charge transfer impacts the entire bulk of LSCF, changing LSCF thickness should inevitably lead to varying performance enhancement, with increasing enhancement for the thinner LSCF samples. However, previous studies have reported significant performance enhancement regardless of the thickness of the modified material, ranging from millimeter-scale bulk materials12 to nanometer-scale thin films14. This observation suggests that the charge transfer likely affects only a limited region near the LSCF/PrOx interface. While it is difficult to accurately determine the exact thickness in LSCF affected by charge transfer, we estimate the region influenced by charge transfer may be confined to the near-interface region of LSCF with the same thickness of the PrOx layer (in this case, the first 5 nm of LSCF). To quantify the defect concentration in this localized region, we again assume it is uniformly distributed within the interface region with a thickness of 5 nm (denoted as \({t}_{{LSCF}}\) below). To evaluate the sensitivity of this assumption, we further examined varying thickness of effective region in LSCF (as shown in Fig. S24 in SI), with the results indicating that although the absolute values of the calculated hole concentrations vary with the assumed thickness, the dependence of current density on hole concentration remains largely unchanged. Therefore, while the assumed value of \({t}_{{LSCF}}\) can effectively capture the localized nature of charge transfer and provides a qualitatively valid basis for analysis. This assumption is also consistent with the finding in Fig. 2c that a thicker PrOx surface modification layer leads to more enhancement of OIR/OER activity. The change of hole concentration in LSCF then can be described using the following equation,i.e.,

where the \({\triangle \left[{e}^{{\prime} }\right]}_{\Pr {O}_{x}}\) and \({\triangle \left[{h}^{\cdot }\right]}_{{LSCF}}\) denote the change in electron concentration in PrOx and hole concentration in LSCF per nanometer, respectively. \({t}_{{LSCF}}\) represents the depth of charge transfer within LSCF and \({t}_{\Pr {O}_{x}}\) denotes the thickness of PrOx thin film (i.e., \({t}_{{LSCF}}\) = \({t}_{\Pr {O}_{x}}\) = 5 nm).

Therefore, \({\triangle \left[{h}^{\cdot }\right]}_{{LSCF}}\) at different oxygen chemical potential can be quantified by using the \({\triangle \left[{e}^{{\prime} }\right]}_{\Pr {O}_{x}}\) values from Fig. 3b. To reiterate, we assume that only the defect concentration within the first 5 nm from the LSCF/PrOx interface changes, while the defect concentration beyond this region remains consistent with the theoretical values calculated from the Brouwer diagram (Fig. S14a in SI). Fig. 3c illustrates the hole concentration in LSCF and the first 5 nm from the LSCF/PrOx interface in LSCF modified with PrOx at various oxygen chemical potentials under this assumption. We analyzed the effects of defect concentration on surface kinetics and established the relationship between the hole concentration and current density of LSCF, as well as LSCF modified with PrOx at various pO2, as shown in Fig. 3d. The current density exhibits a power-law dependence on the hole concentration. In addition to the sharp increase in hole concentration in the surface region of LSCF caused by charge transfer, which significantly enhances surface kinetics, we observed a stronger dependence of current density on hole concentration. This indicates that surface kinetics became markedly more sensitive to defect concentration after modification, aligning with the conclusions from Fig. 2d. Furthermore, we also investigated the role of oxygen vacancies in determining OIR activity (Fig. S14b in SI). We found that after the modification, the oxygen vacancy concentration in LSCF decreased, but the overall OIR performance was still enhanced significantly. This could be potentially attributed to the increased electron concentration (more Pr3+) as well as oxygen vacancy concentration in PrOx induced by interfacial charge transfer.

The mechanisms underlying the performance enhancement caused by charge transfer induced by PrOx surface modification can be highly complex, since charge transfer also influences the interfacial charge distribution and the surface adsorption of gas molecules. Therefore, here we discuss two possible mechanisms of the OIR/OER reactivity enhancement induced by interfacial charge transfer. Firstly, the performance improvement may be attributed to the changes in the electronic structure of PrOx and LSCF induced by charge transfer. Interfacial charge transfer increases the surface electron concentration within the PrOx layer, leading to surface band bending and reducing the barrier for electron transfer to adsorbed oxygen species30. This enhanced electron transfer can accelerate the adsorption, dissociation, and activation of oxygen molecules, significantly improving the kinetics of oxygen exchange reactions. Additionally, charge transfer leads to an increase in the hole concentration in LSCF, and this concentration change induced by charge transfer can alter the coefficient of oxygen exchange reaction31. For certain oxygen electrode materials, such as La0.4Sr0.6FeO3-δ, the OER performance is even directly proportional to the hole concentration24. Therefore, the increase in hole concentration is likely to enhance the kinetics of oxygen exchange reactions. The other mechanism for the enhancement of surface reactivity might be due to the change in surface adsorption of oxygen molecules. The increase in surface electron concentration elevates the concentration of adsorbed oxygen molecules, which in turn facilitates their dissociation and activation, further enhancing the catalytic activity of the electrode13. Overall, the change in electronic structures of PrOx and LSCF as well as potential modifications of the surface adsorption states contribute to the accelerated OIR and OER processes.

Realistic SOCs devices measurements as a demonstration of performance enhancement from surface modification

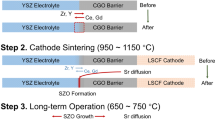

To explore the role of charge transfer in enhancing OIR/OER kinetics through surface modifications, we employed commercial cells as a demonstration to validate the proposed mechanism. The selected cell consisted of LSCF as the air electrode, YSZ as the electrolyte, Ni/YSZ as the fuel electrode, and Gd0.1Ce0.9O2-δ (GDC) as an interlayer between the LSCF and YSZ, as illustrated in Fig. 4a. PrOx was introduced onto the LSCF backbone via the conventional infiltration method, resulting in PrOx particles loaded within the porous backbone, as typically observed in the form of nanoscale to microscale particles (Fig. S22 and Fig. S23 in SI).

a Cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image showing the structure of a Ni-YSZ/YSZ/GDC/LSCF anode-supported cell. b, c Distribution of relaxation time (DRT) plots of (b) the pristine cell and (c) after infiltration with PrOx. d Typical I-V-P curves of bare cells with LSCF and the LSCF modified with PrOx electrodes under different oxygen pressures in fuel cell mode at 700 °C with H2 fuel (200 sccm). e Maximum power density versus the oxygen partial pressure at the air electrode obtained from (b). f Typical I-V curves of the cells under electrolysis mode at 700 °C with 50% H2O and 50% H2 as the fuel electrode gas.

We first conducted EIS tests under open-circuit voltage (OCV) conditions (Fig. S14a,b in SI). To further evaluate the influence of pO2, we analyzed the EIS data by using the distribution of relaxation time (DRT) technique32, as shown in Figs. 4b and c. We categorized the DRT features into three regions: low-frequency (LF, ≤102 Hz), middle-frequency (MF, 102–103 Hz), and high-frequency (HF, >103 Hz), following previous reports in the literature33. In such a complex system, assigning each peak in the DRT data to a specific process can be challenging34. To gain mechanistic insight, we now proceed to analyze each of the three regions individually and in detail. Although the LF response is complex and generally considered to involve multiple steps such as oxygen dissociative adsorption/desorption and charge transfer, these processes are all essential components of surface oxygen exchange. The resistance in the LF region decreased significantly after PrOx surface modification, indicating a clear enhancement in surface reaction kinetics. Therefore, the substantial reduction in LF resistance provides direct experimental evidence that the PrOx modification enhances the surface reaction rate of the LSCF electrode. This observation is consistent with the improvement in OIR/OER activity observed in electrochemical measurements, further supporting the role of interfacial charge transfer in modulating surface reactivity. The interpretation of the MF region remains ambiguous, which may involve multiple concurrent mass transport processes. Nam et al., analyzed this region using a transmission line model (TLM) and proposed that it may reflect oxygen ion conduction within the electrode material33. From our DRT results, we also find that the MF peak is sensitive to pO2—its intensity decreases as pO2 increases—which suggests a possible connection to oxygen ion transport within the electrode. Furthermore, the MF feature is reduced after surface modification with PrOx, consistent with previous literature. Nevertheless, we emphasize that this assignment is not definitive, which means the MF response may also involve oxygen ion transport through YSZ or other interfacial contributions. In contrast, the resistance in the HF region remains nearly unchanged after modification, suggesting that the PrOx layer does not significantly affect the high-frequency process related to charge transfer on the electrode/electrolyte interface35,36. Therefore, although the responses in the MF and HF regions provide useful insights into bulk electrode properties and interfacial transport behavior, the core mechanism governing OIR activity is primarily reflected in the changes observed in the LF region. The significant reduction in LF resistance directly indicates the enhancement of surface reaction kinetics induced by PrOx surface modification.

To explore surface modification on performance enhancement under practical operating conditions, we tested both pristine cells and treated cells with PrOx surface modification layers in both SOFC and SOEC modes. The goal of this approach is to validate the conclusions derived from the thin film model electrode system and to see if the enhancement follows the same trend (as a function of pO2 and oxygen chemical potential) in realistic cells. Figure 4d shows the voltage-current (and power density) curves of both pristine cells and treated cells with PrOx surface modification layers operating in SOFC mode at 700 °C. It can be seen that the performance of cells in SOFC mode can be enhanced by PrOx surface modification. Interestingly, the extracted maximum power density at different pO2, as shown in Fig. 4e, increases with increasing pO2 (i.e., the atmosphere at the air electrode) in SOFC mode, which is consistent with the results observed in the thin film model system (Fig. 2a, b). Under the highest pO2 tested (1 bar), adding PrOx surface modification increases the maximum power density from 0.68 W/cm2 to 1.56 W/cm2, which means that the performance is doubled by using this approach. At the same time, we evaluated the enhancement in SOEC mode of the modified cells, as shown in Figure 5 d. At an electrolysis voltage of 1.5 V, the maximum electrolysis current density increased from 0.64 A/cm2 to 1.17 A/cm2. Therefore, the strategy of using PrOx as a surface modification layer can effectively enhance the performance of real SOFCs and SOECs, while the enhancement can be tuned by experimental parameters such as the pO2 of the air electrode or the operating mode of cells. Despite the significant improvement in cell performance achieved through surface modification, the performance of realistic cells remains far below that of thin-film model systems. This discrepancy may stem from a combination of factors, including differences in microstructures between thin films and real air electrodes. Due to the dense structure and nanoscale thickness of thin film electrodes, the effects of processes such as gas adsorption and ionic diffusion are minimal and can largely be neglected. However, these processes may not be overlooked in realistic cells. Therefore, in realistic cells, gas adsorption and ionic diffusion processes are likely to remain slow, even after surface modification. This is most likely due to the fact that realistic cells possess a structure that is markedly different from that of the thin-film model system. In particular, they typically consist of porous, much thicker electrodes, which provide a significantly larger effective surface area for gas adsorption. This structural difference may lead to distinct adsorption and diffusion behaviors compared to the dense, planar geometry of thin films.

Another potential difference between model thin film electrodes and real cells is that the fuel electrode where hydrogen evolution and reduction reactions take place can also affect overall performance. Although the oxygen electrode is typically considered the rate determining step, the significant enhancement in the reaction kinetics of the oxygen electrode after surface modification may cause the kinetics of the fuel electrode reactions to become comparable to or even slower than those of the oxygen electrode, potentially making the fuel electrode reactions also rate-limiting. The combined results from realistic cells and thin film model electrochemical systems demonstrate that surface modification can enhance the oxygen exchange processes at the oxygen electrode. The insight gained from this combined approach provides potential strategies for designing SOCs with improved performance. Our findings also highlight the role of external experimental parameters (including the environmental pO2 and the oxygen chemical potential in the air electrode) in determining the microscopic process such as interfacial charge transfer, which can strongly impact the surface kinetics.

In summary, we combined insights from carefully-designed electrochemical measurements and operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy to unravel the mechanisms behind OIR/OER performance enhancement induced by surface modifications. By employing well-controlled thin-film model systems with simplified microstructures, we investigated LSCF as a model SOC air electrode and PrOx as a surface modification layer. We discovered that the defect chemistry of PrOx dynamically responds to changes in the oxygen chemical potential, which complements the prior understanding that assumes unchanged stoichiometry of the modification layers. We identified electron transfer from LSCF to PrOx as the key driving force for the enhanced OIR/OER kinetics, over a broad range of oxygen chemical potentials. This electron transfer mechanism effectively elevates the electron hole concentration in LSCF, which directly correlates with increased current density. Moreover, we validated the applicability of this mechanism in realistic SOCs devices, where PrOx surface modifications significantly boosted performance in both fuel cell and electrolysis modes. Interestingly, the extent of performance enhancement depends on the atmosphere of the air electrode and operation mode, which are closely linked to the modulation of interfacial charge transfer controlled by the oxygen chemical potential. This study offers several advances beyond prior works on PrOx-modified oxygen electrodes. Unlike previous studies that primarily inferred mechanisms from theoretical calculations or indirect electrochemical signatures, we directly visualized the interfacial charge transfer process and its impact on defect states using operando XAS. Moreover, we quantitatively correlated hole concentration with electrochemical performance, examined the oxygen potential dependence of the modification effect, and validated the findings across both model systems and practical SOC devices. Leveraging this characteristic, one can potentially optimize the charge transfer behavior by adjusting operating conditions, which might be another way of achieving enhanced performance. These findings provide critical insights into the mechanisms of surface modification in oxygen electrodes. Central to this understanding is the pivotal role of charge transfer in oxygen exchange reactions at oxide surfaces, which extends beyond SOCs. This knowledge has broad implications for a range of technologies where surface oxygen exchange processes are crucial, including oxygen permeation membranes37, gas sensors38 and electrocatalysis and energy storage39. By enabling precise manipulation of charge transfer processes, surface engineering can emerge as a powerful and versatile tool for advancing these applications.

Methods

Thin film model system preparation

Single-crystal YSZ (001) substrates (10 ×10 ×0.5mm3), polished on one side (MTI Corp.), were employed as both the substrate and electrolyte in the fabrication of model thin film electrochemical cells. Nanoporous La0.4Sr0.6CoO3‑δ was deposited as the counter electrode on the backside of YSZ substrates via pulsed laser deposition (PLD) at 450 °C, in 100 mTorr O2, at a laser fluence of 1.2 J/cm2 and frequency of 5 Hz (Nano PLD, PVD Products). LSC was chosen as the counter electrode due to its significantly faster surface kinetics compared to the working electrode, making the influence of LSC negligible, as shown in Fig. S6. A reference electrode was fabricated by applying Pt paste to the side of the substrate, ensuring that the oxygen chemical potential remains constant in this setup. On the polished side of the YSZ, 50 nm Pt current collector grids with a width of 10 μm and a spacing of 40 μm were patterned using photolithography and magnetron sputtering (Fig. S21 in SI). LSCF thin film electrodes were prepared by using PLD at 800 °C, in vacuum ( ~ 10-7 mbar), 1 J/cm2 laser fluence and a frequency of 5 Hz. All PrOx thin film electrodes and PrOx surface modifiers were deposited at 700°C under an oxygen partial pressure of 100 mTorr, using the same laser energy density as that used for LSCF. The film thickness was controlled by the number of laser pulses, as detailed in Table S1 of SI. While the PrOx films used in different measurements (e.g., Figs. 1b and 3a) are not from the same batch, they were prepared under identical deposition conditions. The final structure obtained is a thin film working electrode/YSZ electrolyte/porous LSC counter electrode, with Pt on the side of YSZ as the reference electrode. The thin films include LSCF, PrOx, and LSCF modified with PrOx.

Thin film electrochemical measurements

EIS measurements were performed by using a Solartron SI 1260 frequency response analyzer. Measurements were conducted over a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 1 MHz, with an amplitude of 10 mV. The potentiostatic measurements were recorded by using a Solartron 1287 potentiostat. The atmospheric pO2 was monitored using an oxygen sensor. Different gas environments were established by mixing high-purity O2 (99.999%), N2 (99.999%), and an N2-O2 mixture (99.999%). Gas flow rates were precisely regulated with mass flow controllers.

Single cell fabrication and measurements

The commercial cells consist of Ni-YSZ fuel electrode support, YSZ electrolyte, GDC interlayer and LSCF air electrode were purchased from Suzhou Huatsing Jingkun New Energy Technology Co., Ltd. The button cell has a radius of 0.5 cm, with an electrolyte layer of YSZ approximately 15 μm, a GDC interlayer of about 5 μm, an anode of about 400 μm, and a cathode of approximately 25 μm. Pr(NO3)3·6H2O dissolved in deionized water (0.5 mol/L) was used for LSCF infiltration. The infiltrated cells were then subjected to a pressure of 0.1 mbar for 30 seconds. This process was repeated multiple times, after which the cells were annealed in air at 600 °C for 2 hours. The NiO-YSZ anode was in-situ reduced by exposing it to 10 sccm (standard cubic centimeters per minute) of dry H2 for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were tested under a flow of 100 sccm of dry H2. The oxygen pressure at the air electrode was monitored and controlled by mixing N2 (99.999%) and O2 (99.999%).

Microstructure and phase structure characterizations

AFM of the thin film surface was performed in tapping mode (Oxford Instruments, Jupiter XR). Analytical SEM of the single cell section was conducted by using a field emission scanning electron microscope (Gemini 450, Zeiss). High-resolution X-ray diffraction was performed to characterize the phase structure of thin films by using an X-ray diffractometer (D8 Discover, Bruker) with monochromatic Cu Kα1 X-ray.

Operando ambient-pressure X-ray photoemission/absorption spectroscopy (AP-XPS/XAS) measurements

Operando AP-XPS/XAS measurements were conducted at the BL02B01 beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). The bending magnet beamline provides soft X-rays with a photon flux of approximately 1 × 1011 photons/s at E/ΔE = 3700. The photon energy ranges utilized for X-ray adsorption spectra of Pr M4,5-edge (915–965 eV), Co L2,3-edge (770–800 eV), Fe L2,3-edge (700–720 eV) and O K-edge (520–545 eV). The XPS measurement for the O1s was carried out at a photon energy of 1300 eV. The sample temperature was monitored by measuring the conductivity of YSZ substrates. The environmental oxygen partial pressure was maintained at 0.1 mbar.

Data availability

Source data file available as supplementary material. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Steele, B. C. H. & Heinzel, A. Materials for fuel-cell technologies. Nature 414, 345–352 (2001).

Irvine, J. T. S. et al. Evolution of the electrochemical interface in high-temperature fuel cells and electrolysers. Nat. Energy 1, 15014 (2016).

Graves, C., Ebbesen, S. D., Jensen, S. H., Simonsen, S. B. & Mogensen, M. B. Eliminating degradation in solid oxide electrochemical cells by reversible operation. Nat. Mater. 14, 239–244 (2015).

Shao, Z. & Haile, S. M. A high-performance cathode for the next generation of solid-oxide fuel cells. Nature 431, 170–173 (2004).

Chen, Y. et al. A robust and active hybrid catalyst for facile oxygen reduction in solid oxide fuel cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 964–971 (2017).

Rupp, G. M., Opitz, A. K., Nenning, A., Limbeck, A. & Fleig, J. Real-time impedance monitoring of oxygen reduction during surface modification of thin film cathodes. Nat. Mater. 16, 640–645 (2017).

Ding, D., Li, X., Lai, S. Y., Gerdes, K. & Liu, M. Enhancing SOFC cathode performance by surface modification through infiltration. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 552–575 (2014).

Shin, S. S. et al. Vapor-mediated infiltration of nanocatalysts for low-temperature solid oxide fuel cells using electrosprayed dendrites. Nano Lett. 21, 10186–10192 (2021).

Hendriksen, P. V. et al. Improving oxygen electrodes by infiltration and surface decoration. ECS Trans. 91, 1413–1424 (2019).

Tsvetkov, N., Lu, Q., Sun, L., Crumlin, E. J. & Yildiz, B. Improved chemical and electrochemical stability of perovskite oxides with less reducible cations at the surface. Nat. Mater. 15, 1010–1016 (2016).

Chen, Y. et al. A highly efficient multi-phase catalyst dramatically enhances the rate of oxygen reduction. Joule 2, 938–949 (2018).

Nicollet, C. et al. Acidity of surface-infiltrated binary oxides as a sensitive descriptor of oxygen exchange kinetics in mixed conducting oxides. Nat. Catal. 3, 913–920 (2020).

Siebenhofer, M. et al. Engineering surface dipoles on mixed conducting oxides with ultra-thin oxide decoration layers. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–10 (2024).

Riedl, C. et al. Surface decorations on mixed ionic and electronic conductors: effects on surface potential, defects, and the oxygen exchange kinetics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 26787–26798 (2023).

Yang, T., Kollasch, S. L., Grimes, J., Xue, A. & Barnett, S. A. La0.8Sr0.2)0.98MnO3-δ-Zr0.92Y0.16O2-δ:PrOx for oxygen electrode supported solid oxide cells. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 306, 121114 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. An in situ formed, dual-phase cathode with a highly active catalyst coating for protonic ceramic fuel cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1–7 (2018).

Yang, K. et al. Differentiating oxygen exchange reaction mechanisms across phase boundaries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 25806–25814 (2023).

Xiao, C., Wang, H., Usiskin, R., van Aken, P. A. & Maier, J. Unification of insertion and supercapacitive storage concepts: Storage profiles in titania. Science 386, 407–413 (2024).

Siebenhofer, M. et al. Investigating oxygen reduction pathways on pristine SOFC cathode surfaces by in situ PLD impedance spectroscopy. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 2305–2319 (2022).

Seo, H. G., Staerz, A., Kim, D. S., LeBeau, J. M. & Tuller, H. L. Tuning surface acidity of mixed conducting electrodes: recovery of Si-induced degradation of oxygen exchange rate and area specific resistance. Adv. Mater. 35, 208182 (2023).

Riedl, C. et al. Performance modulation through selective, homogenous surface doping of lanthanum strontium ferrite electrodes revealed by in situ PLD impedance measurements. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 2973–2986 (2022).

Huang, R., Carr, C. G., Gopal, C. B. & Haile, S. M. Broad applicability of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to the measurement of oxygen nonstoichiometry in mixed ion and electron conductors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 19629–19643 (2022).

Fleig, J., Rupp, G. M., Nenning, A. & Schmid, A. Invited) Towards an improved understanding of electrochemical oxygen exchange reactions on mixed conducting oxides. ECS Meet. Abstr. MA 2017, 1589–1589 (2017).

Schmid, A., Rupp, G. M. & Fleig, J. How to get mechanistic information from partial pressure-dependent current-voltage measurements of oxygen exchange on mixed conducting electrodes. Chem. Mater. 30, 4242–4252 (2018).

Guan, Z., Chen, D. & Chueh, W. C. Analyzing the dependence of oxygen incorporation current density on overpotential and oxygen partial pressure in mixed conducting oxide electrodes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 23414–23424 (2017).

Chen, D. et al. Constructing a pathway for mixed ion and electron transfer reactions for O2 incorporation in Pr0.1Ce0.9O2−x. Nat. Catal. 3, 116–124 (2020).

Nenning, A. et al. Ambient pressure XPS study of mixed conducting perovskite-type SOFC cathode and anode materials under well-defined electrochemical polarization. J. Phys. Chem. C. Nanomater Interfaces 120, 1461–1471 (2016).

Schmid, A. & Fleig, J. The current-voltage characteristics and partial pressure dependence of defect controlled electrochemical reactions on mixed conducting oxides. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, F831–F846 (2019).

Lu, Q. et al. Surface defect chemistry and electronic structure of Pr0.1Ce0.9O2-δ revealed in operando. Chem. Mater. 30, 2600–2606 (2018).

Metlenko, V., Jung, W., Bishop, S. R., Tuller, H. L. & De Souza, R. A. Oxygen diffusion and surface exchange in the mixed conducting oxides SrTi1-: YFeyO3-. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 29495–29505 (2016).

Lenser, C., Lu, Q., Crumlin, E., Bluhm, H. & Yildiz, B. Charge Transfer Across Oxide Interfaces Probed by in Situ X-ray Photoelectron and Absorption Spectroscopy Techniques. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 4841–4848 (2018).

Wan, T. H., Saccoccio, M., Chen, C. & Ciucci, F. Influence of the Discretization Methods on the Distribution of Relaxation Times Deconvolution: Implementing Radial Basis Functions with DRTtools. Electrochim. Acta 184, 483–499 (2015).

Nam, S. et al. Revitalizing oxygen reduction reactivity of composite oxide electrodes via electrochemically deposited PrOx nanocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307286 (2024).

Maradesa, A. et al. Advancing electrochemical impedance analysis through innovations in the distribution of relaxation times method. Joule 8, 1958–1981 (2024).

Seo, H. G. et al. Degradation and recovery of solid oxide fuel cell performance by control of cathode surface acidity: Case study – Impact of Cr followed by Ca infiltration. J. Power Sources 558, 232589 (2023).

Yang, K. et al. Machine-learning-assisted prediction of long-term performance degradation on solid oxide fuel cell cathodes induced by chromium poisoning. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 23683–23690 (2022).

Zhu, J. et al. Unprecedented perovskite oxyfluoride membranes with high-efficiency oxygen ion transport paths for low-temperature oxygen permeation. Adv. Mater. 28, 3511–3515 (2016).

Ramamoorthy, R., Dutta, P. K. & Akbar, S. A. Oxygen sensors: materials, methods, designs and applications. J. Mater. Sci. 38, 4271–4282 (2003).

Huang, Z. F. et al. Chemical and structural origin of lattice oxygen oxidation in Co–Zn oxyhydroxide oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Nat. Energy 4, 329–338 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant No. 52202148 and 523B2012) and School of Engineering Dean Special Projects Fund (SOE-DSPF), Westlake University. This work used shared facilities at the Instrumentation and Service Centers for Physical Science of Westlake University and Westlake Center for Micro/Nano Fabrication. Part of the work was performed at Beamline 02B of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility, which is supported by ME2 project from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11227902). The authors would like to thank Dr. Xiaohe Miao, staff scientist of the Instrumentation and Service Center for Molecular Sciences of Westlake University, for her valuable advice on XR-XRD analysis. We also thank Dr. Rui Wang (Westlake University) for discussions on surface microstructure of the thin film samples. K.Y. acknowledges Prof. Markus Kubicek (TU Wien) and Dr. Matthäus Sibenhofer (TU Wien) for valuable and helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y. and Q.L. conceived and designed the project. K.Y. performed the sample fabrications, performance measurements, and basic characterizations. K.Y., J.Z., Y.L. and Z.Z. performed the AP-XPS/XAS characterization and analyzed the data. H.Z. and Z.L. provided supervision and suggestions for the AP-XPS/XAS experimental. Q.L. provided continuous supervision throughout the project. All authors revised and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bryan Eigenbrodt, WooChul Jung, Peng Qiu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, K., Zheng, J., Lu, Y. et al. Elucidating the role of interfacial charge transfer on the oxygen incorporation/evolution reactions for solid oxide cells. Nat Commun 16, 11472 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66361-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66361-z