Abstract

The fabrication of 3D soft material architectures is essential for advancing fields such as soft robotics, wearable technologies, and biological engineering. However, conventional embedded 3D printing is constrained by rheological complexity and nozzle-dependent structural limitations. Here, we introduce transformable embedded ink writing (TEIW), a 3D printing strategy that bypasses these issues by triggering rapid, autonomous self-assembly of 2D-printed patterns into predefined 3D structures. TEIW employs yield-stress inks within a Newtonian-like fluid bath, where net gravitational-buoyancy forces drive the filaments to go upward or downward. Through tailored density contrasts, controlled viscosity, and mechanical coupling between structural elements, complex shape transformation is directed with physical intelligence embedded in the printed structure itself, requiring no external intervention. This strategy demonstrates broad compatibility with materials including silicone elastomers, acrylate-based resins, and hydrogels, enabling applications spanning customizable microelectronics, perfusable networks, and cryptographically encoded devices. Furthermore, TEIW’s ability to integrate various components in a single print establishes a platform for next-generation systems requiring spatiotemporal multi-material control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fundamental principle of “form follows function” underscores the importance of 3D structures, where the material’s architecture directly dictates its performance and unlocks untapped possibilities for functional applications across scales. This design philosophy is particularly significant in the realm of soft materials, which underpin innovations in emerging fields such as soft robotics1,2, smart wearables3, and advanced medical devices4. In recent years, extrusion-based 3D printing, particularly direct ink writing (DIW), has emerged as a powerful tool for rapid prototyping of customizable soft systems5,6,7,8,9. In a typical DIW process, viscoelastic ink is extruded through a nozzle onto a substrate in ambient air to build the designed structure10. Although conventional DIW is cost-effective and highly scalable, its layer-by-layer printing manner often requires auxiliary structures to support overhang or complex geometries, complicating the fabrication process. Moreover, structural integrity relies on the ink’s ability to solidify rapidly, which limits material choices, especially for silicone elastomers that typically exhibit slow curing kinetics11,12. To overcome these challenges, embedded ink writing (EIW) has been developed, wherein inks are extruded into a liquid bath instead of directly into air13,14,15,16. The supporting bath is typically a yield-stress liquid, which can locally fluidize under shear from the moving nozzle and rapidly transition back to a solid state once the shear is released17,18. In this way, it provides omnidirectional support and enables freeform fabrication. As a result, EIW has demonstrated versatility across diverse applications, including strain sensors19, pneumatic actuators8, vascular networks20, and cell-laden scaffolds fabrication21.

Nevertheless, the EIW method introduces its own challenges. Firstly, the process demands careful rheological compatibility between the ink and the bath material. Mismatches in yield stress or viscosity could cause filament irregularities22,23,24. Moreover, the use of a yield-stress bath in turn requires the ink to possess even higher yield stress to maintain structural fidelity25. The incorporation of rheological modifiers (e.g., nanoparticles) further complicates ink formulation and may impair the material’s properties. Secondly, the EIW process remains heavily dependent on the extrusion nozzle26,27. The printable height is constrained by the nozzle length. Longer nozzles are prone to deflection due to resistance from the support fluid, compromising printing accuracy. In addition, when printing near or across previously deposited ink filaments, the nozzle can induce mechanical disturbances in the bath, making it difficult to achieve high geometric fidelity.

Aiming to address these challenges, this work presents a printing strategy termed transformable embedded ink writing (TEIW), which enables the fabrication of 3D structures through the self-assembly of 2D-printed patterns via a net gravitational-buoyant force. This density-driven mechanism enables printed filaments to ascend in regions of higher buoyancy or sink under greater gravity, thereby autonomously transforming planar precursor patterns into preprogrammed 3D architectures within seconds to minutes. TEIW operates within a Newtonian-like fluid support bath, which reduces the strictness of rheological compatibility requirements in conventional ink-bath systems. Once the ink is released from the nozzle, TEIW circumvents the structural height limitations imposed by nozzle length and avoids the need for complex 3D trajectory control. Moreover, the self-assembly nature of the process inherently avoids distortions caused by nozzle interference. In contrast to externally stimulated 4D printing28 or magnet-assisted morphing strategy29, our approach requires no specialized responsive materials and accommodates a broader spectrum of soft materials, including elastomers, hydrogels, photocurable resins, and polymer composites. Building on this material generality, we demonstrate applications spanning customizable microelectronics, perfusable vascular networks, and cryptographically encoded functional devices. This strategy thus offers a simple and versatile route to fabricating delicate multifunctional 3D structures, opening avenues in soft material manufacturing.

Results

Principle of TEIW

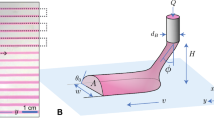

The TEIW process is predicated on direct writing of 2D planar patterns within a Newtonian-like fluid medium, followed by autonomous 3D shape transformation governed by buoyancy-gravity interactions (Fig. 1a). This contrasts fundamentally with conventional embedded ink writing (CEIW), which relies on viscoelastic yield-stress fluids to stabilize deposited filaments (Fig. 1b). In CEIW, the support bath exhibits shear-thinning behavior, which flows under nozzle-induced shear stress and behaves as a solid once the stress is removed. Its pairing with higher yield-stress inks enables the maintenance of filament geometry and position, wherein the bath’s yield stress defines the maximum force exerted on the ink filaments17,18,23,25,30. In TEIW, the support medium is a Newtonian-like fluid with constant viscosity and density within the operating range. When an ink is extruded into the bath, each filament segment experiences the gravity \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}={\rho }_{{ink}}g{{{\rm{\pi }}}}{r}^{2}L\) and buoyancy \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}={\rho }_{{bath}}g{{{\rm{\pi }}}}{r}^{2}L\), where ρink and ρbath are the density of the ink and bath, g is the acceleration of gravity, r and L are the radius and length of the ink filament, respectively. The net driving force \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{drive}}}}}={{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}-{{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}\) determines vertical motion of the ink filament: positive Fdrive causes sinking, while negative values result in flotation. By systematically adjusting printing parameters (extrusion pressure P and nozzle velocity v), discrete filament segments with tailored Fdrive can be generated. For example, continuously extruding a high-density ink (ρink > ρbath) horizontally into a Newtonian-like bath with varying volumetric flow rates (Q1 < Q2 < Q3 < Q4) produces four distinct segments with differential axial weight distribution (Fig. 1c). Over time scales of seconds to minutes, these segments migrate to their target depths, guided by their respective Fdrive, to self-assemble into the desired 3D architectures. This transformation is then rapidly stabilized (typically within a minute) by initiating solidification via IR-induced thermal curing or photoinitiation, effectively locking the structure in place. The TEIW platform supports four fabrication modalities (Fig. 1d). (ⅰ) Freestanding structures: After shape transformation, the support medium is removed, leaving intact 3D constructs. (ⅱ) Integral structures: Ink and bath components are co-cured to form a monolithic 3D structure. (ⅲ) Hollow architectures: Sacrificial inks are selectively dissolved to create microfluidic channels. (ⅳ) Hybrid printing: This modality relies on the coexistence of different stabilization mechanisms within a single bath. A fine-scale ink (e.g., hydrogel) is first deposited and stabilized in situ, analogous to CEIW processing, owing to its minimal buoyancy-gravity forces and intrinsic rheology. Subsequently, a second ink (e.g., conductive elastomer) with tailored properties to undergo programmed TEIW is deposited, which autonomously assembles around or within the pre-formed structure. This approach enables the seamless integration of different materials and printing mechanisms without requiring bath exchange or complex sequential processing.

a Schematic illustration of the TEIW platform. b Rheological comparison between (i) CEIW and (ii) TEIW, including the comparison of storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G”), with their relative position evolvement influenced by gravitational force (Fg) and buoyant force (Fb). c Dynamic 2D-to-3D self-assembly driven by buoyancy-gravity interplay, where the moving distance is controlled by the volumetric flow rates. d Printing modalities enabled by TEIW: (i) freestanding structures via bath removal, (ii) integral structures through co-curing, (iii) hollow architectures using sacrificial inks, (ⅳ) hybrid printing of multi-materials via sequential steps.

Transformation dynamics governed by material physics

In embedded 3D printing systems, the intricate interplay of the rheology of the extruded ink and its surrounding bath governs the filament morphology and structural supporting capability. A comprehensive investigation involving a diverse set of ink-bath combinations was systematically conducted. The detailed formulations, material properties, and designations of all inks and baths used throughout this study are documented in Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1. To ensure structural integrity, all inks formulated for this study were yield-stress fluids. The position change of ink filaments in the z-axis is investigated using 700 µm-diameter Ink-1 filaments printed at ~3 mm below the liquid surface (Supplementary Fig. 2). In a conventional EIW process, the yield stress of the bath (Bath-0) stabilizes the deposited filament at its printed position (Fig. 2a). The density differentials exhibit negligible effects compared to dominant rheological parameters. In the TEIW process, Newtonian-like fluids serve as the support bath. The Newtonian nature of these baths is confirmed by their linear shear stress-shear rate relationships, and their storage modulus (G’) is consistently lower than their loss modulus (G’’). To elucidate the impact of density differentials (Δρ = ρink – ρbath) on filament behavior, ink-bath pairs were selected with varying density contrasts. For Ink-2 (0.990 g/cm³) and Bath-1 (0.998 g/cm³), the ink filament exhibited upward migration behavior (Fig. 2b). It ascended 2.3 mm in 4 min due to positive buoyancy (Δρ = −0.008 g/cm³), with no lateral displacement. Conversely, when ρInk-1 (1.016 g/cm³) exceeds ρBath-2 (0.998 g/cm³), a gravity-driven descent transformation occurred. Under this moderate density contrast (Δρ = +0.018 g/cm³), a 1 mm displacement was observed over 9 min (Fig. 2c). Images illustrating this sinking behavior, along with results from other ink-bath combinations, are provided in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4. A direct correlation was revealed between the magnitude of the density difference and the extent of vertical displacement within a given time frame. For instance, with a larger density mismatch of Δρ = +0.050 g/cm³ (ρInk-1 = 1.016 g/cm³, ρBath-3 = 0.966 g/cm³), a 4.6 mm vertical translation was achieved within 5 min (Fig. 2d).

a Static behavior in conventional bath (Ink-1, Bath-0), b buoyancy-driven ascent (Ink-2, Bath-1), c gravity-driven descent with low density contrast Δρ (Ink-1, Bath-2), and d gravity-driven descent with high density contrast (Ink-1, Bath-3). Each row, from left to right, sequentially presents time-dependent vertical movement of the ink filament, shear stress-shear rate curve of the bath with inset optical micrographs of the filament cross-sections (scale bar: 100 μm), storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G”) curves for ink and bath, and density of the materials. All data are presented as mean values ± s.d. from n = 4 independent replicates.

To quantitatively understand the correlation between density contrast and displacement dynamics, the driving force for filament motion (Fdrive) is given by:

where d and L are the filament diameter and length, respectively. Under low Reynolds number conditions prevalent in this system (Re ≈ 3.33×10-6 ≪ 1), this motion is resisted by a viscous drag force Fdrag. Given the finite aspect ratio characteristic of the printed filament (L/d ~ 50), the drag force must be described by a modified form of Stokes’ law that accounts for its non-spherical geometry and end effects31. Such filaments can be approximated as slender cylinders. For transversely moving (axis perpendicular to motion) finite-length cylinders in viscous fluids, the hydrodynamic drag force Fdrag is described by:

where η is the dynamic viscosity of the bath, and \({v}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}\) is the terminal velocity. The logarithmic term ln(L/d) accounts for length-to-diameter ratio effects on drag resistance, while the constant term Cconst is derived from experimental corrections for end effects. At terminal velocity (vt), the filament reaches dynamic equilibrium, where the driving force is balanced by the viscous drag force (Fdrive = Fdrag). Substituting the expressions for both forces yields the terminal velocity:

It reveals that while density contrast dictates the direction of motion, both the density contrast and the bath viscosity conjointly govern the motion kinetics. Figure 2c, d show that the settling time for a 1 mm displacement can be drastically reduced by 89%, from 9 min to 1 min, achieved through the synergistic effect of decreasing bath viscosity from 9.20 Pa·s to 4.18 Pa·s while increasing the density contrast. The inverse dependence of velocity on bath viscosity is further supported by the additional systems provided in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6. This rate amplification is crucial for time-sensitive materials, as it significantly accelerates the overall printing process, enabling rapid stabilization before material solidification. Experimental observations confirm that the terminal velocity is attained within 150 ms. Therefore, vt can be regarded as the characteristic deposition speed. The above analysis confirms that the modified Stokesian framework can offer quantitative guidelines for selecting bath viscosity (ηbath) and density contrast (Δρ) to match deposition kinetics with material-specific solidification constraints.

Optical micrographs show that the cross-sections of ink filaments preserved a circular morphology after transformation and solidification (inset of Fig. 2). This well-defined shape is primarily maintained by the ink’s own yield-stress and viscoelastic properties immediately upon deposition, with the Newtonian-like bath providing negligible resistance to flow and thus minimal mechanical stress on the filament. Furthermore, by employing silicone-based ink-bath pairs with a near-zero interfacial tension (γ ≈ 0 mN/m), filament shrinkage and deformation did not occur. In contrast, systems with higher interfacial tension (e.g., γ ≈ 20 mN/m in epoxy-silicone systems) induced Plateau-Rayleigh instability, causing ink filaments to break up into droplets within seconds (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8)32,33. Notably, these droplets also underwent gravity-driven descent (Supplementary Fig. 9), suggesting potential for droplet-embedded patterning and an alternative deposition modality for functional composites34,35.

Printing parameters regulation

With density and viscosity fixed in the system, the filament diameter (d) is a key determinant of deposition velocity, as described by Eq. (3). This diameter is governed by the volumetric flow rate (Q), which can be controlled through extrusion pressure (P) and nozzle velocity (v), according to the Hagen-Poiseuille law (\(Q={{{\rm{\pi }}}}{r}^{4}\varDelta P/8\eta L\)) and fluid continuity principle (\(Q=\pi {\left(\frac{d}{2}\right)}^{2}v\))36. It leads to the predictive relation \(d=2\sqrt{Q/{{{\rm{\pi }}}}v}\). Experiments using a 610 µm nozzle and Ink-1/Bath-1 as a model system showed that the filament diameter increased from 360 µm to 600 µm as P was raised from 40 to 80 psi at a constant v of 5 mm/s (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). Conversely, at a fixed P of 60 psi, decreasing v from 13 to 3 mm/s resulted in a diameter increase from 400 to 620 µm. These results are consistent with the theoretical framework. Since the terminal velocity vt∝d2, this ability to precisely control diameter via P and v provides direct regulation over the kinematic behavior of filaments (Supplementary Fig. 10c, d), enabling programmable 3D transformation without the need for mechanical nozzle changes.

Filament diameters and morphology as functions of a extrusion pressure P and b nozzle speed v. c Terminal sinking velocity vt as a function of filament diameter d. d Deposition distance versus time of a 660 µm ink filament. Synchronized deposition of 640 µm and 680 µm filaments, e achieving the same depth by introducing a time delay Δt and f creating a designed depth difference ΔD. All experiments were conducted using Ink-1/Bath-1 and a 610 μm nozzle. All data are presented as mean values ± s.d. from n = 3 independent replicates.

In the current model system, filament curling occurred under low extrusion pressure (P ≤ 55 psi) or high nozzle speed (v ≥ 7 mm/s) when using a 610 µm nozzle (Fig. 3a, b). This instability arose from the ink’s inability to fully recover its microstructure after rapid shear thinning37. The Newtonian-like bath, lacking a yield stress, did not provide any stabilizing confinement, thereby allowing this inherent ink instability to appear as free-form curling. Notably, switching to a finer nozzle within the same ink-bath system produced thinner filaments that exhibited reduced disturbance and improved stability (Supplementary Fig. 11)38. More importantly, it enabled access to a distinct low-velocity deposition regime. When the filament diameter falls below 270 µm, the corresponding settling velocity drops below 0.1 mm/min (Fig. 3c). Within this low-velocity regime, defined here as the “static zone”, the filament can be stabilized rapidly via curing (~1 min) before significant displacement occurs (Supplementary Fig. 12), enabling precise shape retention analogous to conventional EIW.

Based on the above framework, the temporal evolution of the filament’s z-position can be quantitatively predicted. Given that the ink filament sinks at an essentially uniform velocity, the deposition distance D is effectively approximated by \(D={v}_{t}\times t\), where t is the duration. This predictive capability was validated by the close agreement between the experimental data and the theoretical prediction for a 660 µm diameter filament, as shown in Fig. 3d. Furthermore, this model enables synchronization control. By deliberately delaying printing by a time Δt of a thinner filament to compensate for its slower sinking rate, two filaments with a 40 µm diameter difference were synchronized to reach the same depth simultaneously (Fig. 3e). Conversely, printing 680 µm and 640 µm filaments simultaneously resulted in a pronounced vertical offset of 1.5 mm (Fig. 3f). These results show that the filament diameter variations, encoded via printing parameters, can be translated into time-dependent deposition differences.

Experiments with non-uniform and curved filaments reveal that the sinking velocity is dictated by fluid-structure interactions arising from their geometry (Supplementary text and Fig. 13). A heterogeneous filament sinks more slowly than a uniform filament of the same maximum diameter, as the mechanical coupling between segments of different diameters restrains the overall motion. Similarly, greater filament curvature leads to a slower descent. These findings form the basis for a rational workflow proposed to guide the optimization of the TEIW printing process by addressing key factors such as the ink-bath system and printing parameters (Supplementary Fig. 14).

3D structural construction

Through a combination of printing parameters (P, v) and path geometry, predictable transformation of 2D patterns into complex 3D architectures can be achieved. Demonstrations include curvilinear structure, double helix, tetrahedron, and bifurcation structure, with experimental details provided in Supplementary Fig. 15 and Supplementary Table 1. With reference to computer-aided design (CAD) blueprints, a 3D helix was fabricated via printing a planar spiral pattern with graded printing pressures (P4 > P3 > P2 > P1), which induces diameter variations along the continuous filament (Fig. 4a). Thicker, high-pressure segments sank faster than thinner, low-pressure regions, establishing a continuous curvature gradient along the spiral. The deformation arose from the relative motion between adjacent turns. The faster-sinking outer segments dragged the slower inner segments downwards, while the slower-sinking inner sections restrained the outer ones, resulting in smooth, continuous helical geometries. Similarly, by alternating the nozzle velocity, a segmented linear filament transformed into a waveform pattern (Fig. 4b). The faster-sinking segments descended ahead of the slower-sinking ones, forcing the straight filament to buckle periodically in the vertical plane, transforming it into a stable, undulating 3D structure.

a–d Structural fabrication workflows. (i) CAD-derived 2D patterns, (ii) pressure/velocity-gradient-driven dynamic transformation processes, (iii) resulting 3D architectures, (iv) photographs of the 3D structures. a Graded-spiral, b curvilinear, c double-helical, d tetrahedral. e Branched vascular structures. (i) 2D pattern, (ii) printed planar pattern, (iii) schematic illustration of the designed 3D vascular networks, (iv) biomimetic vascular architecture via TEIW. Scale bar: 1 cm.

Dual helical structures were realized by printing a continuous filament in a serpentine pattern with programmed flow rate variations (Fig. 4c). Each section of the pattern exhibited a high-flow side (blue) and a low-flow side (gray), and adjacent sections had this orientation reversed. During transformation, the high-flow side descended faster, thereby generating a localized torque at the junctions and lifting the low-flow side upward. The systematic reversal of the force gradient along the path caused these torques to alternate in direction, prompting the entire structure to twist and coil into a stable, double-helical morphology. The rapid self-assembly (≤10 s) demonstrates programmable kinetic control through filament-level force modulation.

The tetrahedral structure, a closed three-dimensional architecture, was achieved via velocity-graded triangular motifs (Fig. 4d). The central high-flow-rate region (v3 = 3 mm/s) exhibited a larger diameter and higher driving force compared to the peripheral low-flow-rate segments (v1, v2, v4 = 7, 5, 10 mm/s). This systematic heterogeneity established an asymmetric force distribution across the triangular pattern. During sinking, the high-drive central region experienced preferential descent, but its motion was constrained by mechanical connectivity to the slower peripheral arms. This constraint converted the vertical force imbalance into a distributed bending moment, triggering simultaneous upward folding along three pre-defined edges. The entire structure underwent coordinated large deformation, evolving into a stable tetrahedron within 5 min. Structural integrity was maintained through dynamic force equilibrium during the transformation, without nozzle-induced disturbances affecting the structure.

To explore bioprinting potential, CAD-designed 2D bifurcation patterns were printed using colored Ink-1 (Fig. 4e). By assigning different printing velocities, differential deposition between slow trunk segments and fast terminal branches introduced a controlled force imbalance. This programmed kinematic imbalance drove spontaneous 3D vascularization, inducing out-of-plane bending to yield vessel-like structures that mimic natural arteriovenous branching networks. This mechanism overcomes filament interference challenges inherent in conventional 3D branched printing. The z-axis fidelity of the above structures was quantified by comparing the as-printed heights with the theoretical depths predicted by Eq. (3) for straight filaments, yielding values from 86.48% to 98.16% (Supplementary Fig. 16a). The observed variance stems from geometric and interfacial factors beyond this simplified model. For a direct comparison, 3D structures were also printed using the conventional EIW method in a reported yield-stress support bath25 (Supplementary Fig. 16), whereas TEIW demonstrated higher geometric accuracy while maintaining a comparable preparation time (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Material versatility and functionality

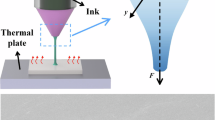

The versatility of the TEIW strategy is demonstrated through its application to three material systems, each representing a different printing mode, including bulk curing of silicone elastomers to form monolithic structures, printing of discrete, self-supporting structures with photocurable resins, and direct writing of perfusable microchannels using sacrificial hydrogels. All three systems utilized Bath-3 and were based on yield-stress inks. The printing of a CAD-designed flower structure, employing velocity gradients (vmax = 10 mm/s, vmin = 5 mm/s), was performed in the three systems to induce differential deposition between petal tips and the central region (Fig. 5a). The silicone elastomer bulk structure was fabricated using the Ink-2/Bath-3 system with a positive density contrast of 0.024 g/cm³ (Fig. 5b). Programmed velocity gradients between petal segments drove controlled trajectory divergence through differential Stokesian settling, enabling autonomous 3D shaping. The process comprised three steps, including 60 s for 2D printing, 250 s of post-printing transformation, and 60 s for complete solidification under infrared light. The curing kinetics of the silicone elastomer in this work were tailored using additives. An inhibitor secured a minimum 24-h printing window at room temperature, while an added platinum catalyst facilitated infrared-induced curing within 1 min to ensure printing accuracy.

a Design and transformation schematic of a flower structure. b–d Characterization and printing results of three material systems. b Silicone elastomer, c photocurable resin, d hydrogel. Each systems show (ⅰ) ink rheology, (ⅱ) ink/bath density comparison (Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. from n = 4 independent measurements), (ⅲ) predicted and measured deposition displacement at petal tip and flower center (Data are presented as mean values ± s.d. from n = 3 independent replicates), (ⅳ) schematic of the printed mode, (ⅴ) optical images showing the states at different times after printing. Scale bars: 5 mm. The inset in d (ⅴ) shows the channel is refilled with water.

A high-density photocurable ink, composed of acrylic resin and silicone elastomer precursor, was printed within Bath-3 (Fig. 5c). The significant density mismatch enabled ultrafast deposition, completing 2D-to-3D transformation within 20 s. The resulting structure was then stabilized by UV curing for 10 s. The cured flower structure was directly picked up from the bath, preserving the bath’s reusability. The 3D channels in Fig. 5d were fabricated using Pluronic F-127 hydrogel as a sacrificial ink. The printed filaments, with diameters ranging from 710 μm to 1010 μm, were printed at room temperature within 40 s. With a density of 1.020 g/cm³, the ink sank and formed the 3D structure within 120 s. The bath was then cured via infrared irradiation, and sacrificial ink was removed via cold deionized water flushing. Perfusion with dyed water verified the channels’ interconnectivity and structural integrity. These demonstrations highlight the TEIW strategy’s robust adaptability, enabling precise spatiotemporal control over 3D structure formation across elastomeric, photocurable, and hydrogel systems while maintaining process scalability and mechanical fidelity.

Carbon-based conductive inks (1.450 g/cm³) were directly printed into a silicone support bath, with the ink ultimately embedded within the cured elastomeric matrix (Fig. 6a). The bath’s optical transparency enables visual confirmation of 3D circuit geometries, while its inherent mechanical robustness protects embedded structures from external forces, such as compressive loads. Results show that 3D circuits embedded in the support bath maintained continuous conductivity when subjected to a compressive load ranging from 0 to 500 g, with a resistance variation of less than 0.5%. This performance arises from the bath’s elastomeric encapsulation, which uniformly distributes mechanical stress and prevents structural failure of the conductive pathways.

a Resistive response of the embedded conductive circuitry under 0–500 g compressive loads. b Heterogeneous integration of a 3D channel and a helical circuit. c Validation of 3D channels via dyed fluid perfusion. d Embedded helical wires powering a green LED. e–g A stimuli-responsive encryption system. e Infrared thermography of the thermochromic elastomer during heating (25–75 °C). f Optical transparency changes of the thermochromic layer. g Visualization of fluorescent pattern under UV light. Scale bar: 1 cm.

A key advantage of the TEIW strategy is its capability for hybrid multi-material printing by synergistically combining distinct deposition mechanisms within a single process. This is demonstrated by sequentially printing two functional materials into the same support bath (Fig. 6b). First, a Pluronic F-127 sacrificial hydrogel filament was deposited. Due to its small diameter (480 μm) and small density contrast with the bath (Δρ = +0.054 g/cm³), the filament experienced negligible buoyancy-driven motion, remaining stabilized in its predesigned position, a behavior analogous to conventional EIW and effectively creating a static reference structure. Subsequently, a conductive ink filament (220 μm diameter) with a significant positive density contrast (Δρ = +0.484 g/cm³) was printed adjacent to the hydrogel structure. This second ink actively underwent TEIW, with programmed velocity gradients driving its autonomous 2D-to-3D transformation into a helical architecture within 1 min. This hybrid approach achieved seamless dual-material integration without cross-interference. After thermal curing of the bath and removal of the sacrificial hydrogel, the resulting structure contained perfusable microchannels alongside fully functional helical conductive circuits, as confirmed by dyed fluid perfusion (Fig. 6c) and powering an LED (Fig. 6d). The helical circuits also function as thermal sensors, with fluid circulation in the adjacent channels inducing real-time resistance changes (Supplementary Fig. 18). The parallel use of static and dynamic mechanisms within the same bath significantly expands the utility of the technique for creating integrated, multi-functional devices. Furthermore, this strategy supports conventional layer-by-layer stacking on the bath substrate, enabling the fabrication of dense, volumetric objects (Supplementary Fig. 19).

TEIW enabled the direct embedment of a 3D fluorescent “grass” pattern within a bulk thermochromic pigment (TC-P)-doped support bath, creating a monolithic, dual-functional optical system. This one-step integration ensures fine interfacial contact between the hidden pattern and the responsive matrix. Upon gradient heating (28.4°C–74.1 °C), the TC-P layer decolorizes from the top down, while UV light penetrates to reveal the progressively unmasked fluorescence from the embedded grass pattern (Fig. 6e, f). This spatially and thermally regulated transition demonstrated reversible encryption over 50 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 20), showing promise for high-grade anti-counterfeiting and confidential data display.

Discussion

This study presents a TEIW method that utilizes planar printing of yield-stress inks and their automatic assembly within Newtonian-like fluid baths. By applying a modified Stokesian framework that quantitatively couples the net buoyancy force arising from density contrast with the viscous drag force governed by bath viscosity, TEIW achieves precise control over filament deposition through simple printing parameter adjustments, effectively bridging the gap between the simplicity of 2D patterns and the complexity of 3D structures. Furthermore, it allows for concurrent assembly of functional components such as fluidic, electrical, and structural elements within a single printing session, opening a route toward next-generation integrated systems with spatiotemporal material control. Future enhancements aimed at the development of a multi-physics simulation, alongside the integration of computational algorithms for predictive control and a multi-inlet system for real-time density control, will further expand the precision and compositional versatility of TEIW. This strategy could pave the way for the on-demand fabrication of increasingly sophisticated and intelligent devices.

Methods

Materials

SE 1700 and Sylgard 184 were purchased from Dow Corning. Ecoflex 00-10, Ecoflex 00-30, Ecoflex 00-50, THIVEX, Silicone Thinner, and pigment were purchased from Smooth-on. Fumed silicone dioxide (15 nm), 1-ethynyl-1-cyclohexane (99%,) and tertiary butanol (GR, ≥99.5%) were obtained from Shanghai Macklin. Pluronic-F127 (Mw: ~12,600 g/mol) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and UV-curing acrylic resin U10 was acquired from AILIKE. A platinum catalyst (Karstedt’s catalyst, Platinum(0)-1,3-diethenyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethyldisiloxane complex, Pt ~2000 ppm) was bought from Zhenjiang Jusheng New Energy Co., Ltd. Graphite conductive ink (DT-7837) was purchased from Taizhou Tongjie Technology Co., Ltd. A commercial microencapsulated thermochromic powder (leuco dye-based) was obtained from Shenzhen Dongfang Jubao Industrial Co., Ltd. Fluorescent powder (SrAl₂O₄: Eu, Dy) was purchased from Tai’an Jinzhi New Materials Co., Ltd. All the chemicals were used as received.

Ink preparation

For silicone inks, an inhibitor composed of 1-ethynyl-1-cyclohexane and tertiary butanol in a weight ratio of 1:38.75 was used to extend the printing window to 48 h. For Ink-1, the SE 1700 base was mixed with its curing agent at a weight ratio of 10:1, using a planetary mixer (SpeedMixer DAC 150.1 FVZ-K) at 2500 rpm for 3 min, then 1 wt% of inhibitor was added to the total mixture and mixed at 2500 rpm for 3 min. For Ink-2, 2 g of Ecoflex 00-30 Part B and 0.02 g of the inhibitor were mixed at 2500 rpm for 2 min. Then 0.2553 g of silica was added and mixed at 3000 rpm for 4 min. The mixed components were cooled in a refrigerator at -18 °C for 5 min. The same cooling process was repeated after each mixing step. Subsequently, 2 g of Ecoflex 00-30 Part A was added and mixed at 3000 rpm for 4 min. The mixture was blended three times, with cooling after each cycle. For the sacrificial hydrogel ink, 3.33 g of PF-127 powder was dissolved in 10 ml of deionized water at 4°C to prepare a 25 wt% solution, and restored to room temperature to achieve the corresponding hydrogel. The photocurable ink was prepared by mixing U10 and SE 1700 (the base and curing agent pre-mixed at a 10:1 ratio as described above) in a weight ratio of 7:3 at 1600 rpm for 30 s. To enhance the visibility of print filament, 1 wt% of pigment was added to the total ink mixture after blending, and the mixture was then mixed at 2500 rpm for 3 min. For the conductive ink, no further treatment was performed. It was directly loaded into a black light-proof syringe. For the fluorescent ink, Sylgard 184 and its curing agent were first blended at a 10:1 weight ratio, and after adding 1 wt% of inhibitor to the total mixture, it was homogenized at 2500 rpm for 3 min. Subsequently, 6 wt% of silica was incorporated into the silicone mixture and mixed at 3000 rpm for 3 min three times, with the mixture being cooled in the refrigerator for 5 min after each mixing. Then, 1 wt% fluorescent powder was added, followed by three sequential mixing cycles at 2000 rpm for 30 s each. All the mixed inks were transferred to a 10 cc syringe and degassed at 2800 rpm for 3 min to remove air bubbles.

Bath preparation

For Bath-0, 10 g of Ecoflex 00-30 Part B and 0.1 g of inhibitor were mixed at 2500 rpm for 2 min. Then, 10 g of Part A and 0.2 g of THIVEX were mixed at 2500 rpm for 2 min. After carefully scraping the mixture remaining at the bottom of the mixing tank and on the walls with a spatula, the mixture was blended again at 2500 rpm for 3 min. Finally, the two mixtures were mixed at 3000 rpm for 3 min, with three cycles of mixing and cooling. For Bath-1, 10 g of Ecoflex 00-30 Part B and 0.1 g of inhibitor were mixed at 2500 rpm for 2 min, then 10 g of Part A was added and mixed at 3000 rpm for 3 min and cooled, then repeated twice. Bath-2 was prepared in the same procedure as Bath-1 using Ecoflex 00-10. For Bath-3, the base and curing agent of Sylgard 184 were mixed at a weight ratio of 10:1, then 1 wt% of inhibitor was added to the total mixture. The mixture was mixed at 3000 rpm for 3 min and cooled, then repeated twice. For the thermochromic support bath, Sylgard 184 base and curing agent were first mixed at a weight ratio of 10:1. Then, 0.5 wt% of THIVEX, 0.1 wt% of thermochromic powder, and 1 wt% of the catalyst were sequentially added and blended at 2500 rpm for 3 min. After all the support bath mixtures were completed, they were transferred to a customized acrylic container and vacuum degassed for 30 min.

Rheology

Rheological tests were performed using an Anton Paar MCR 302 rheometer at room temperature, equipped with a 25 mm diameter parallel plate geometry measurement system with a 1.0 mm gap between the parallel plates. The apparent shear viscosity was obtained by performing logarithmic scan steady state flow tests using angular frequency ranging from 0.1 to 100 rad/s. In the frequency scan tests, the storage and loss modulus of the materials were measured in the linear viscoelastic range, through an angular frequency range with a strain amplitude of 0.5%, from 0.1 to 10,000 rad/s. To characterize the yield stress of the support matrix, stress sweeps were performed from 0.1 to 100 Pa at an oscillatory frequency of 1 Hz.

3D printing

Direct ink writing was performed on a dispensing system (F4200N.1 Compact Benchtop Robot). The extrusion pressure was controlled by a DC200 digital dispenser (Fisnar) with a vacuum compression pump, and the pressure was set at 10 psi -80 psi. Stainless-steel nozzles with inner diameters of 160, 210, 420, 520, and 610 µm was used. The printing speed was set at 1–20 mm/s, depending on the properties of the material and the requirements of the print pattern. During the printing process, the nozzle was immersed in a support bath at a depth of ~3 mm. After printing, the nozzle was removed from the support bath at a speed of 1 mm/s. The whole process was carried out at room temperature.

After 3D printing and transformation of the architecture, the system underwent solidification. For silicone elastomer systems, immediate thermal curing was conducted using a 250 W infrared lamp positioned 10 cm vertically above the support bath. Complete crosslinking of both ink and bath was achieved within 10 min.

The channeled system was printed using a needle with an inner diameter of 420 µm, at a printing pressure of 40 psi and a printing speed of 1 mm/s, to extrude the PF-127 hydrogel into the Sylgard 184 support bath. The curing protocol was then applied in the same manner as for silicone elastomer systems. Then, samples were immersed in an ice-water bath for 5 min to liquefy the sacrificial hydrogel. The liquefied ink was then removed via aspiration, followed by three rinsing cycles with ice-cold water.

For the UV photocurable systems, the photocurable ink, prepared by mixing U10 and SE 1700 in a 7:3 weight ratio, was extruded into the Sylgard 184 support bath. Using a needle with an inner diameter of 520 µm, the ink was printed at a pressure of 20 psi and a printing speed of 5 mm/s to print the designed 2D pattern. For solidification, the bath system was placed in a UV curing chamber (3535KXD, UVGO) and exposed to 365 nm, 240 W ultraviolet light for 15 s. The cured 3D architectures were then extracted from the support bath, wiped with a lint-free wipe to remove residual bath material, and cleansed with an anionic surfactant-based detergent solution.

The conductive system used graphite conductive ink printed into the Sylgard 184 support bath that additionally contains 1 wt% platinum catalyst. A needle with an inner diameter of 210 µm was used to print a planar spiral with a minimum radius of 18 mm, a maximum radius of 2.5 mm, and consisting of 3 turns. The printing process was conducted at a printing speed of 4 mm/s and a pressure of 10–40 psi. After 3D printing and shape transformation, the structure was immediately thermally cured using a 250 W infrared lamp positioned 10 cm vertically above the support bath. The crosslinking of the support bath was completed within 1 min, and the conductive ink solidified through solvent evaporation.

For dual-material printing, PF-127 sacrificial ink was first extruded through a 210 µm inner diameter nozzle under 40 psi to construct 3D helical scaffolds with a uniform radius of 10 mm, a height of 6 mm, and four turns within the support bath. Subsequently, graphite conductive ink was extruded through a 160 µm nozzle with a dispensing pressure of 20 psi −50 psi, forming a planar spiral with an outer radius of 7 mm, an inner radius of 1.5 mm, and three turns, at a depth of 2 mm in the support bath. After 1 min, the planar spiral configuration spontaneously transformed into a 3D architecture driven by the density contrast. The solidification and removal of the sacrificed ink followed the protocol mentioned above.

For the encrypted system, a 3D biomimetic “grass” structure comprising five radially arranged blades was printed, using the fluorescent ink within a Sylgard 184 support bath containing thermochromic pigments. Each blade was 6 mm long and presented a 72° outward inclination angle from the central axis. The printing used a 210 µm inner diameter nozzle and 4 mm/s speed, with varying pressures of 20 psi, 20 psi, 20 psi, 30 psi, and 40 psi for each blade. After printing, the support bath was infrared cured following the same curing steps as for Sylgard 184.

The detailed 3D printing settings are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Imaging

The position variations of the filaments and the structure transform process were recorded by an industrial camera (Basler ace acA800-510uc) installed on the side of the printer. Imaging was performed with an optical magnification of 20× using a macro lens configuration. To minimize the inaccuracy caused by the disturbance generated by the nozzle entering and leaving the support bath process, each filament was printed 3 times, and the middle section of the print filament was recorded. Images were captured at 1 min intervals. The ImageJ software was used to measure the diameter of print filaments and the deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Due to the high reproducibility, error bars may be smaller than the symbols. Full statistical data are available in the Supplementary Information. Printed filament cross-sections were obtained by slicing with a blade, imaged, and analyzed by optical microscopy (Eclipse Ni-U, Nikon).

Physical properties measurement

The density of all inks and support baths was measured using a densitometer (SJ-300GY, Shuju), with three measurements conducted for each sample (5 g per measurement).

The electrical resistance was measured by using a digital source meter (Keithley 2450) with a four-probe configuration. Copper wires (diameter: 100 µm) were inserted into the two terminals of the conductive structure, forming a closed circuit with an LED bulb powered by a programmable DC power supply (Zhaoxin RXN-305D). For the encrypted visualization, the sample was heated on a hot stage from 28.4 °C to 74.1 °C to realize a visible chromatic transition. Then the illuminated patterns were observed under UV light (365 nm) in complete darkness. Surface temperature was recorded by an infrared thermal imager (E6390, FLIR).

Data availability

The main data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information, other data presented in this manuscript are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Aygül, C., Guven, C., Frunzi, S. A., Katz, B. J. & Nemitz, M. P. A framework for soft mechanism driven robots. Nat. Commun. 16, 1426 (2025).

Zhang, C. et al. Flexible electro-hydraulic power chips. Nat. Commun. 16, 1404 (2025).

Zhang, B. et al. A three-dimensional liquid diode for soft, integrated permeable electronics. Nature 628, 84–92 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Magnetic soft microfiberbots for robotic embolization. Sci. Robot. 9, eadh2479 (2024).

Kim, E. et al. Magnetically reshapable 3D multi-electrode arrays of liquid metals for electrophysiological analysis of brain organoids. Nat. Commun. 16, 2011 (2025).

Zhao, T. et al. Modular chiral origami metamaterials. Nature 640, 931–940 (2025).

Cui, H. et al. Design and printing of proprioceptive three-dimensional architected robotic metamaterials. Science 376, 1287–1293 (2022).

Truby, R. L. et al. Soft somatosensitive actuators via embedded 3D printing. Adv. Mater. 30, e1706383 (2018).

Weeks, R. D., Truby, R. L., Uzel, S. G. M. & Lewis, J. A. Embedded 3D printing of multimaterial polymer lattices via graph-based print path planning. Adv. Mater. 35, e2206958 (2023).

Ho, M. et al. Direct ink writing of conductive hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2415507 (2025).

Herzberger, J., Sirrine, J. M., Williams, C. B. & Long, T. E. Polymer design for 3D printing elastomers: recent advances in structure, properties, and printing. Prog. Polym. Sci. 97, 101144 (2019).

Liravi, F. & Toyserkani, E. Additive manufacturing of silicone structures: a review and prospective. Addit. Manuf. 24, 232–242 (2018).

Eom, W. et al. Fast 3D printing of fine, continuous, and soft fibers via embedded solvent exchange. Nat. Commun. 16, 842 (2025).

Hua, W. et al. High-speed embedded ink writing of anatomic-size organ constructs. Adv. Sci. 12, 2405980 (2025).

Muth, J. T. et al. Embedded 3D printing of strain sensors within highly stretchable elastomers. Adv. Mater. 26, 6307–6312 (2014).

Alioglu, M. A. et al. 3D embedded printing of microfluidic devices using a functional silicone composite support bath. Addit. Manuf. 70, 103566 (2023).

Hua, W. et al. Fluid bath-assisted 3D printing for biomedical applications: from pre- to postprinting stages. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 7, 4736–4756 (2021).

Thareja, P., Swarupa, S., Ahmad, S. & Jinugu, M. E. Hydrogel-based inks for extrusion 3D printing: a rheological viewpoint. Curr. Opin. Colloid. Interface Sci. 77, 101918 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Multi-material embedded 3D printing for one-step manufacturing of multifunctional components in soft robotics. Addit. Manuf. 85, 104178 (2024).

Fang, Y. et al. Expanding embedded 3D bioprinting capability for engineering complex organs with freeform vascular networks. Adv. Mater. 35, e2205082 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Dissecting the interplay mechanism among process parameters toward the biofabrication of high-quality shapes in embedded bioprinting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313088 (2024).

Friedrich, L. M. & Woodcock, J. W. Filament disturbance and fusion during embedded 3D printing of silicones. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 10, 6690–6710 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. Freeform 3D printing of soft matters: recent advances in technology for biomedical engineering. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 10, 453–479 (2020).

Friedrich, L. M. & Seppala, J. E. Simulated filament shapes in embedded 3D printing. Soft Matter 17, 8027–8046 (2021).

Grosskopf, A. K. et al. Viscoplastic matrix materials for embedded 3D printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 23353–23361 (2018).

Zhao, J. & He, N. A mini-review of embedded 3D printing: supporting media and strategies. J. Mater. Chem. B 8, 10474–10486 (2020).

Zeng, X. et al. Embedded bioprinting for designer 3D tissue constructs with complex structural organization. Acta Biomater. 140, 1–22 (2022).

Ding, A., Tang, F. & Alsberg, E. 4D printing: a comprehensive review of technologies, materials, stimuli, design, and emerging applications. Chem. Rev. 125, 3663–3771 (2025).

Xie, R. et al. Magnetically driven formation of 3D freestanding soft bioscaffolds. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl1549 (2024).

Zhou, S. et al. Embedded 3D printing of microstructured multi-material composites. Matter 7, 668–684 (2024).

Jayaweera, K. O. L. F. & Mason, B. J. The behaviour of freely falling cylinders and cones in a viscous fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 22, 709–720 (1965).

Wu, Q. et al. Embedded extrusion printing in yield-stress-fluid baths. Matter 5, 3775–3806 (2022).

O’Bryan, C. S. et al. Self-assembled micro-organogels for 3D printing silicone structures. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602800 (2017).

Zhu, J. & Cai, L.-H. All-aqueous printing of viscoelastic droplets in yield-stress fluids. Acta Biomater. 165, 60–71 (2023).

Nelson, A. Z., Kundukad, B., Wong, W. K., Khan, S. A. & Doyle, P. S. Embedded droplet printing in yield-stress fluids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 5671–5679 (2020).

Duraivel, S. et al. A silicone-based support material eliminates interfacial instabilities in 3D silicone printing. Science 379, 1248–1252 (2023).

Yuk, H. & Zhao, X. A new 3D printing strategy by harnessing deformation, instability, and fracture of viscoelastic inks. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704028 (2018).

Hua, W. et al. Filament formation mechanisms in yield-stress fluid-enabled embedded ink writing. Addit. Manuf. 91, 104353 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A2074, L.Z.; 22075015, L.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft. T.P.: investigation, validation. Z.S.: investigation, validation. X.L. (Li): investigation, validation. J.W.: formal analysis, visualization. X.L. (Lin): resources. F.G.: conceptualization, resources. M.G.: conceptualization, Resources. D.W.: conceptualization, resources. L.Z.: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing— review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Pang, T., Sun, Z. et al. Up-and-down transformable embedded ink writing strategy for soft 3D architectures. Nat Commun 16, 11348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66418-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66418-z