Abstract

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) establishes a latent infection in neurons, periodically reactivating to cause disease. Neuronal conditions, including immune signaling, during initial HSV-1 infection, impact later reactivation. Type I interferon (IFNα) exposure during initial infection results in promyelocytic leukemia nuclear-body (PML-NB) formation and subsequent restriction of reactivation, via mechanisms that were unknown. Here we find that PML-NB formation results in the recruitment of histone chaperones to the viral genome and increased enrichment of the repressive heterochromatin mark, histone H3 lysine 9 tri-methylation (H3K9me3), and its reader, ATRX (alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation, X-linked). ATRX is highly abundant in neurons and prevents reactivation from H3K9me3-bound latent genomes by remaining associated with viral chromatin. Therefore, we demonstrate how immune signaling during initial infection results in an epigenetic memory on HSV-1 genomes and identify ATRX as a neuronal restriction factor against HSV-1 reactivation, elucidating a new potential target for inhibiting HSV-1 reactivation and subsequent human disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) establishes a lifelong latent infection in neurons, allowing the virus to persist in its host for extended periods and evade immune surveillance. The DNA virus genome persists in the nucleus of an infected neuron and is subjected to heterochromatin-based silencing1,2,3. It is thought that epigenetic silencing mechanisms promote and maintain latency and need to be remodeled for reactivation to occur. However, studies investigating the contribution of heterochromatin to HSV-1 latency are complicated by the heterogeneous nature of the latent viral epigenome. For example, there is evidence of heterogeneity in the subnuclear distribution of viral genomes and levels of viral gene expression and reactivation4,5,6,7,8. How different epigenetic structures form and whether they differentially contribute to reactivation competencies is unknown. Understanding heterogeneity in the context of HSV-1 is essential, as reactivation is associated with a variety of diseases, including cold sores, herpes simplex keratitis, and encephalitis. Further, studying HSV-1 in neurons informs on epigenetics in this specialized cell type.

The state of cells at the time of initial infection could impact latency and future reactivation competency. For example, neuronal stress or immune signaling during initial infection has been shown to modulate later reactivation9,10. The mechanisms underlying cell-intrinsic long-term memory during HSV-1 latency, triggered by short-term external stimuli, remain unknown. In the case of innate immune stimuli, type I interferon (IFNα) exposure at the time of primary infection restricts later reactivation. This restriction is dependent on Promyelocytic leukemia-nuclear body (PML-NB) formation in neurons10. PML-NBs are membrane-less nuclear organelles composed of the scaffolding protein PML and various stably and transiently associated proteins11. PML-NBs compartmentalize proteins within eukaryotic cells and play a role in the intrinsic repression of productive herpesvirus replication12,13,14,15. A subpopulation of HSV genomes colocalizes with PML-NBs during latency5. However, the mechanism underlying PML-NB-dependent restriction remains unclear, specifically whether it is due to changes in epigenetic silencing or the physical entrapment of viral genomes within PML-NBs.

The latent HSV-1 genome is known to be associated with repressive histone modifications. However, the intersection between extrinsic stimuli and the latent epigenome, both in the context of latency establishment and reactivation, are unknown. Latent viral genomes are enriched with H3K9me2, H3K9me3, and H3K27me31,2,3. H3K9me3 is viewed as a long-term, constitutive form of heterochromatin, whereas H3K27me3 is known to mark regions of facultative heterochromatin on the host, which can potentially more readily convert to active chromatin for gene expression16. However, during HSV-1 infection of a terminally differentiated neuron, it is unknown whether certain histone post-translational modifications give rise to genomes that are differentially capable of reactivating. Furthermore, investigating heterogeneity is challenging as most techniques analyze populations of genomes. To investigate heterochromatin marks on a single genome, we developed a tool (NucSpotA) to quantify the immunofluorescent stain at a single viral genome that is then standardized to the stain throughout the nucleus. This tool has enabled us to quantify subpopulations of genomes that display distinct marks17. We hypothesized that interferon-induced PML-NBs increase the subpopulation of latent genomes with H3K9me3 silencing. This hypothesis is based on previous studies showing that PML-NBs impact H3K9me3 deposition on cellular chromatin18 and viral DNA during lytic infection19. It remains uncertain how an increase in the percentage of viral genomes with H3K9me3 would lead to a more repressive state of latency.

H3K9me3 represses chromatin through its interaction with histone readers, including HP1 family proteins20,21,22, alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation, X-linked (ATRX)23,24, CHD425, TRIM6626, PHRF126, UHRF127, TNRC1828, MPP829, and Tip6030, whereas the Polycomb family of protein complexes reads H3K27me331. The diversity in reader proteins increases the potential complexity of viral genome silencing. The readers associated with the latent HSV-1 genome remain unidentified, but understanding their role in silencing is crucial, as reader-based silencing would need to be overcome for reactivation to occur. HSV-1 reactivation is biphasic6,32,33,34,35 and the first phase of reactivation involves phosphorylation of serine 10 neighboring H3K9me3 (H3K9me3pS10). This phosphorylation evicts many H3K9me3 readers, allowing for transcription without the removal of repressive methylation marks. Importantly, ATRX is an H3K9me3 reader that is resistant to eviction following S10-phosphorylation24. We investigated whether ATRX restricts HSV-1 reactivation and found that ATRX inhibits reactivation from H3K9me3-enriched genomes. This inhibitory effect was further amplified by IFN treatment, which increases ATRX enrichment at the latent viral genome, suggesting a mechanism by which IFN treatment restricts reactivation.

Results

PML does not maintain IFNα-restricted HSV-1 latency

Previously, using an in vitro model system of HSV-1 latent infection, we reported that PML-NBs form in peripheral sympathetic and sensory neurons following exposure to IFNα. We also observed that the HSV-1 genome co-localizes and is maintained at PML-NBs only when initial infection occurs concurrently with IFNα exposure10. IFNα treatment during initial infection also resulted in repression of reactivation that could be overcome by PML depletion before infection. To determine the mechanism of PML-based restriction, we asked whether PML was required for both the initiation and maintenance of the repressive reactivation phenotype. Primary neurons from the superior cervical ganglia (SCG) of postnatal mice were dissected and infected with Stayput-GFP (MOI 5 PFU/cell)6. Stayput-GFP expresses a Us11-GFP and is also defective in cell-to-cell spread, permitting the quantification of individual reactivating neurons (Fig. 1A). Neurons were also treated with 600 IU/μl of IFNα for 18 h prior to infection. Acyclovir (ACV) was added for the first 8 days post-infection to promote latency establishment and then washed out. Reactivation was triggered 10 days post-infection using the PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, as described previously6,32,33,36,37 (Fig. 1A). To deplete PML, neurons were transduced with lentivirus expressing Pml shRNA five days before or after infection with HSV-1 (Supplementary Fig. 1A–D). Consistent with our previous study10, we found PML depletion prior to infection resulted in enhanced reactivation of IFNα-treated neurons to levels comparable to the untreated neurons (Fig. 1B). However, depletion of PML after latency had already been established did not impact reactivation in IFNa-treated neurons (Fig. 1C). This phenotype was confirmed using knockout in PML-floxed SCG neurons induced post-infection via adeno-associated virus (AAV)-delivered Cre (Supplementary Fig. 1E–G). We found that PML knockout post-infection did not impact reactivation in IFNα-treated neurons (Supplementary Fig. 1H). These findings suggest that the presence of PML-NBs during initial infection contributes to the restrictive phenotype initiated by IFNα treatment during infection, but PML-NBs are not required to maintain IFNα-induced silencing at later timepoints.

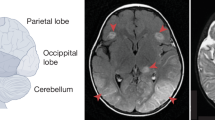

A Schematic of the primary neuronal model of HSV-1 latency and reactivation using sympathetic neurons isolated from post-natal murine superior cervical ganglia (SCG). Created in BioRender. Cliffe, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/au8f3tn. B HSV-1 reactivation quantified by Us11-GFP positive neurons at 2 days post-reactivation. PML was depleted using lentivirus-mediated shRNA depletion five days pre-infection and treated with 600 IU/ml IFNα for 18 h before infection and 24 h post-infection. Reactivation was induced using LY294002 (20 μM). Individual repetitions (N = 9; wells containing approximately 5000 neurons) from 3 independent dissections. Analysis with Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison (*p = 0.038; **p = 0.0058). C HSV-1 reactivation quantified by Us11-GFP positive neurons at 2 days post-reactivation. Neurons were treated IFNα before infection as in (B) and depleted of PML using lentivirus-mediated shRNA depletion five days post-infection. N = 9 biological replicates from 3 independent dissections. Analysis with Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison (**p = 0.0016). D Representative images of sympathetic neurons cultured in atmospheric (21% Oxygen) or physioxia (5% oxygen) conditions and fixed at either 18 h post-treatment with IFNα (or 0 h post-infection) or 7 days post-infection. Immunofluorescence was done for PML and cells co-stained with Hoechst. Scale bar, 10 μm. E Percentage of neurons with detectable PML-NBs in their nuclei and F detectable PML puncta per nuclei at 18 h post-treatment with IFNα or 7 days post-infection in either atmospheric or physioxia conditions. N > 50 cells from 3 biological replicates. Analysis with two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons (*p = 0.0419; **p = 0.003; ****p < 0.0001). G Neurons treated with IFNα at the time of infection were infected with HSV-1 EdC/EdA and fixed at 1- or 10-days post-infection. The viral genome was visualized using click chemistry, and immunofluorescence was done for PML. White arrows point to location of viral genome. Scale bar, 10 μm. H Signal intensity of PML at the viral genome at 1- or 10-days post-infection. Each data point represents one viral genome. Percentages indicate the proportion of genomes with NucSpotA intensity ratios above the denoted co-localization threshold (dashed line). N > 125 cells from 3 biological replicates. Analysis with two-tailed Mann–Whitney (****p < 0.0001). Data represent the mean ± SEM.

The contribution of PML to the maintenance of the restrictive phenotype differed from our previous study, where PML depletion after latency was established, resulted in increased reactivation. In our original study, neurons were cultured in atmospheric conditions. However, we have since changed the culturing conditions to a physiological oxygen concentration (5% O2) for peripheral neurons38,39, which improves neuronal health40. We investigated whether the change in oxygen impacted the formation of PML-NBs at the time of infection (18 h post IFNα stimulus) and persistence of PML-NBs during infection (Fig. 1D). Here, we used a latent timepoint of 7 days post-infection, as compared to 10 days, which is used throughout this manuscript, to compare with the previous study where PML-NBs were only cultured in hyperoxic conditions10. We found that IFNα-treated neurons cultured in physiologic oxygen had fewer PML-NBs per neuron (Fig. 1E) and decreased PML-NB persistence than those cultured in atmospheric oxygen (Fig. 1F). These data suggest that the oxygen concentration in vitro affects neuronal response to innate immune signals. Although PML initially co-localized with HSV-1 following IFNα treatment in both atmospheric and physiological oxygen concentrations, after 10 days, the co-localization was lost under physioxia (Fig. 1G). We quantified this phenotype over multiple latent neurons using NucSpotA17 (Fig. 1H) and observed 81.5% of genomes co-localized at 1 day in contrast to 29% at 10 days. The percentage of genomes co-localizing was determined by setting a signal intensity threshold based on visual inspection of 50 genomes. Together, our data indicate that PML associates with the viral genome during initial infection and initiates silencing, but PML-NBs do not persist during latency and are not required to maintain the restrictive phenotype of IFNα.

IFNα-induced restriction is DAXX-dependent

Our observation that PML was not required to maintain the silent state induced by IFNα treatment argued against a role for the PML protein in directly contributing to genome inaccessibility in latently infected neurons. Instead, we hypothesized restriction was due to PML-dependent altered epigenetic structures. Therefore, we investigated PML-NB components that have known roles in heterochromatin targeting, particularly Death Domain Associated Protein (DAXX), because it is a constitutive component of PML-NBs and plays a role in the deposition of histones at regions of heterochromatin. Further, previous studies have found that DAXX represses HSV-1 lytic infection15,41,42 via its role as an H3.3 chaperone43,44,45,46. The function of DAXX during HSV latency is unknown. Using two independent shRNAs, DAXX knockdown pre-infection (Supplementary Fig. 2) recovered IFNα-restricted reactivation (Fig. 2A, B). Consistent with the data on PML, the viral genome also co-localized with DAXX in IFNα-treated neurons at early time points (1 day post-infection) (Fig. 2C) but not at latent time points, arguing against a role for DAXX in maintaining restriction during latency (Fig. 2D, E). Additionally, we investigated whether PML was required for the observed enrichment of DAXX. We found that depletion of PML before infection significantly reduced the association of viral genomes with DAXX (from 80.5% of genomes co-localized with DAXX to 0.18%) (Fig. 2F), demonstrating DAXX contributes to the repressive effects of IFNα and is recruited to viral genomes in a PML-dependent manner.

A, B Sympathetic neurons were infected with Stayput HSV-1 in the presence or absence of IFNα and depleted of DAXX using shRNAs at 5 days pre-infection using two independent shRNAs. Reactivation was quantified based on the numbers Us11-GFP expressing neurons following addition LY294002. Data represent the mean ± SEM. N = 9 biological replicates from 3 independent dissections. Statistical comparisons were made using an Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison (A: *p = 0.0328; *p = 0.0267; ***p = 0.0001. B: *p = 0.0101; ****p < 0.0001). C, D Representative images of sympathetic neurons untreated or treated with 600 IU/ml of IFNα cultured in 5% oxygen. Neurons were infected with EdC/EdA-labeled HSV-1 and depleted of PML or DAXX at 5 days pre-infection. Cells were fixed at 1 day (C) and 10 days (D) post-infection. The viral genome was visualized using click chemistry, and immunofluorescence was carried out for DAXX. White arrows indicate viral genome. Scale bar, 10 μm. E, F NucSpotA was used to quantify the signal intensity of DAXX at the viral genome 1- or 10-days post-infection. Each data point represents one viral genome. Percentages indicate the proportion of genomes with NucSpotA intensity ratios above the denoted co-localization threshold (dashed line). N > 60 cells from 3 biological replicates. Statistical comparisons were made using E two-tailed Mann–Whitney (****p < 0.0001) and F Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison (*p = 0.0122; ****p < 0.0001).

IFNα increases H3K9me3 enrichment on the viral genome

Previous studies have demonstrated that PML-NBs contribute to increased enrichment of H3K9me3 on cellular chromatin18 and HSV-1 DNA during lytic infection17. Additionally, DAXX has been associated with the formation of heterochromatin characterized by H3K9me347, which is known to be enriched on populations of HSV-1 genomes during quiescent infection1,44,48. We hypothesized that IFNα exposure alters the epigenetic silencing of the latent HSV-1 genome via increased H3K9me3 in a DAXX- and PML-dependent manner.

To test this hypothesis, we carried out immunofluorescence to determine the colocalization of H3K9me3 with the viral genome once latency was established (Fig. 3A). To overcome problems in quantifying the co-localization of nuclear proteins with viral genomes and take into account the heterogeneity of histone enrichment at different viral genomes in a population, we used NuncSpotA17. We identified a subpopulation of viral genomes that co-localized with H3K9me3 in untreated neurons (49.3%), which increased significantly in the IFNα treatment to 75.3% (Fig. 3B). Depletion of either PML or DAXX prior to infection significantly reduced the proportion of viral genomes co-localized with H3K9me3 as compared to interferon-treated neurons, where PML and DAXX were not depleted (30.2% for PML depletion and 33.3% for DAXX depletion vs. 75.3% in IFNα non-depletion control neurons). In comparison to interferon-treated shRNA control transduced neurons, we did not observe a significant difference in H3K9me3 enrichment when PML or DAXX depletion occurred after latency had been established (55.9% in PML-depleted and 51.5% in DAXX-depleted neurons vs. 75.3% in IFNα non-depletion control neurons). These data indicate the population of genomes associated with H3K9me3 increases with IFNα treatment. This increase was PML and DAXX-dependent during early infection, but these proteins were not required for the mark to persist at later time points.

A Representative images of SCGs untreated or treated with 600 IU/ml of IFNα cultured in 5% oxygen. Neurons were infected with EdC/EdA-labeled HSV-1 and depleted of PML or DAXX at 5 days pre-infection or 5 days post-infection. Cells were fixed at 10 days post-infection. The viral genome was visualized using click chemistry, and immunofluorescence was done for H3K9me3. White arrows point to location of viral genome. Scale bar, 10 μm. B Signal intensity of H3K9me3 at the viral genome 10-days post-infection. Each data point represents one viral genome. Percentages indicate the proportion of genomes with NucSpotA intensity ratios above the denoted co-localization threshold (dashed line). N > 60 cells from 3 biological replicates. Analysis with repeated Measure One-way ANOVA (A, B *p = 0.035; A–D *p = 0.0125; A–F *p = 0.0267; B, C *p = 0.0451; C, D *p = 0.0167; C–F *p = 0.0352; D, E *p = 0.0195; E, F *p = 0.0431). C Sympathetic neurons were infected Stayput-GFP HSV-1 at an MOI of 10 PFU/cell in the presence or absence of IFNα. CUT&Tag was performed at 10 days post-infection using an H3K9me3 antibody. Fragments were sequenced and aligned to the viral genome. The sum of coverage at the defined gene body and promoter regions were used to calculate the enrichment of H3K9me3. The average enrichment sum of all viral gene bodies is plotted, with a line connecting the mock and IFNα treatments for individual viral open reading frames. N = 2 biological replicates. D Plot of gene bodies with a log fold change of greater than 0.5 or less than −0.5 across both replicates. Immediate early genes (purple), early genes (orange), and late genes (teal) are shown. E The average enrichment sums of all viral gene promoters. The line connects the same viral promoter in mock and IFNα-treated cultures. N = 2 biological replicates. F Plot of gene promoters that had a log fold change of greater than 0.5 or less than −0.5 across both replicates. Immediate early genes (purple), early genes (orange), and late genes (teal) are shown.

To further validate the increased H3K9me3 association upon IFNα treatment and investigate where on viral genomes H3K9me3 was enriched, we performed Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) for H3K9me3 on latently infected neurons. We first determined, in accordance with other studies1, that H3K9me3 is enriched on the viral genome during latent infection. We assessed duplication rates using Picard and found that duplication was significantly higher in IgG samples as compared to H3K9me3 samples, indicating a difference in library complexities (Supplementary Fig. 3A). For this reason, IgG duplicates were removed as recommended49. Spearman correlation analysis of normalized viral read coverage across the genome revealed a strong similarity between biological replicates (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Linear regression analyses of viral read distribution in both mock-treated (Supplementary Fig. 3C) and IFNα-treated (Supplementary Fig. 3D) conditions further confirmed reproducibility across datasets. We then used Integrative Genomics Viewer (Supplementary Fig. 3E) to visualize the entire viral genome and found broad distribution of H3K9me3 is broadly distributed across the HSV-1 genome. We then sought to determine the differences in H3K9me3 enrichment in our two conditions.

Consistent with our immunofluorescence results, IFNα treatment increased the sum of H3K9me3 enrichment over viral gene bodies (excluding promoter regions) (Fig. 3C, D) and promoters (Fig. 3E, F). Viral gene bodies and promoters were quantified because H3K9me3 enrichment at both cellular promoters and cellular gene bodies has been correlated with epigenetic repression and transcriptional silencing50. Genes that had at least a twofold increase in H3K9me3 over two replicates were plotted. We concluded that there were consistent regions of the genome with increased H3K9me3 in IFNα-treated neurons. These findings suggest that IFNα promotes H3K9me3 enrichment on the genome and that this mark persists during latency and correlates with a decrease in reactivation.

ATRX restriction of HSV-1 reactivation is enhanced by IFNα

Given our observation that PML and DAXX contributed to the initiation of IFNα-mediated repression via H3K9me3, we set out to investigate ATRX. ATRX can be a component of PML-NBs and complexes with DAXX to deposit H3.3. The ATRX-DAXX complex represses lytic HSV-1 infection in human fibroblasts41,43. ATRX can also function as an H3K9me3 reader23 and has been shown to maintain the enrichment of H3K9me3 on lytically replicating viral genomes42. During HSV-1 lytic infection of non-neuronal cells, the role of ATRX and DAXX is PML-NB dependent41,42. Yet, on cellular chromatin, ATRX is multifaceted and can also function independently of PML and DAXX51. The role of ATRX in HSV-1 gene silencing during latency is unknown. We hypothesized that ATRX may have DAXX- and PML-dependent and -independent functions in neurons. Since ATRX can be a component of PML-NBS, we hypothesize that nuclear body formation and colocalization with the viral genome may lead to an increase in ATRX enrichment. To test these hypotheses, we depleted ATRX prior to HSV infection and once latency had been established using two independent shRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 4A–D). We found ATRX depletion prior to infection resulted in enhanced reactivation of IFNα-treated neurons (Fig. 4A, B). In contrast to PML and DAXX, the depletion of ATRX after latency was established (Fig. 4C, D), also resulted in significantly enhanced reactivation in IFNα-treated neurons. This phenotype was confirmed using knockout in ATRX-floxed SCG neurons induced post-infection via AAV-delivered Cre (Supplementary Fig. 1E–G). We found that PML knockout post-infection did not impact reactivation in IFNa-treated neurons (Supplementary Fig. 4H). These finds indicate that unlike PML and DAXX, ATRX is required for maintaining the restrictive phenotype in IFNα-treated neurons.

A, B HSV-1 reactivation quantified by Us11-GFP positive neurons at 2 days post-reactivation. ATRX depleted using two independent shRNAs five days pre-infection and treated IFNα for 18 h before infection and 24 h post-infection. Reactivation induced using LY294002 (20 μM). A N = 9 from 3 independent dissections. B N = 12 from 4 independent dissections. Analysis with Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison (A: *p = 0.0328; *p = 0.0423; **p = 0.0018. B: ***p = 0.0004; **p = 0.0024). C, D HSV-1 reactivation quantified by Us11-GFP positive neurons at 2 days post-reactivation. SCGs treated with IFNα 18 h pre-infection and 24 h post-infection. ATRX depleted using two independent shRNAs five DPI. Reactivation induced using LY294002. N = 9 from 3 independent dissections. Analysis with Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison (C: **p = 0.0016; *p = 0.0135. D: **p = 0.0016; **p = 0.0017; ****p < 0.0001). E SCGs untreated or IFNα-treated and cultured in 5% oxygen. Neurons were infected with EdC/EdA-labeled HSV-1 and depleted of PML at 5 days pre-infection or 5 DPI. Fixation at 10 days post-infection. The viral genome was visualized using click chemistry, and immunofluorescence was done for ATRX. White arrows point to the viral genome. Scale bar, 10 μm. F Signal intensity of ATRX at the viral genome 10-days post-infection. Each data point represents one viral genome. Percentages indicate the proportion of genomes with NucSpotA intensity ratios above the denoted co-localization threshold (dashed line). N > 60 cells from 3 biological replicates. Analysis with Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison (****p < 0.0001). G Signal intensity of ATRX at the viral genome 10 days post-infection in mock-treated neurons. 180 rotated control (CTRL). Each data point represents one viral genome. Percentages indicate the proportion of genomes with NucSpotA intensity ratios above the denoted co-localization threshold (dashed line). N > 60 cells from 3 biological replicates. Analysis with unpaired two-tailed t-test (****p < 0.0001). H HSV-1 reactivation quantified by Us11-GFP positive neurons at 2 days post-reactivation. PML, DAXX, or ATRX were depleted using shRNAs five days post-infection. Reactivation was induced using LY294002. N = 9 from 3 independent dissections. Analysis with Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison (**p = 0.0024; *p = 0.0253). Data represent the mean ± SEM.

Supporting a role for ATRX in maintaining the repressive nature of HSV-1 latency, we found that unlike DAXX and PML, ATRX co-localization with the viral genome is maintained during latency, with detectible co-localization with ATRX at 10 days post-infection (Fig. 4E). This colocalization significantly increased with IFNα treatment (from 43% of genomes co-localized with ATRX to 75%) (Fig. 4F). Notably, this association level was similar to the proportion also associated with H3K9me3, as shown in Fig. 3B (49.3% in untreated and 75.3% IFNα treated). We then determined whether PML was required for the observed increase in ATRX enrichment. We found that depletion of PML before infection significantly reduced the association of viral genomes with ATRX (from 75% of genomes co-localized to 47.1%) in IFNα-pretreated neurons. However, depletion of PML after infection did not impact ATRX enrichment. Therefore, the IFNα-dependent increase in ATRX association with the viral genome was dependent on PML only during initial infection. These data further support that IFNα-induced PML-NBs enact long-lasting epigenetic changes that are maintained independently of the bodies themselves during latency.

In contrast to PML and DAXX, we found that ATRX co-localized viral genomes even in the untreated neurons (43%), albeit to lower levels than IFNα-treated neurons (Fig. 4F). To determine whether this association occurred at levels above those obtained for random co-localization, we compared the co-localization values to those of a 180° rotated control (for random placement of the viral genome in the nucleus17) and found that ATRX was significantly enriched on the viral genome (Fig. 4G). This prompted us to investigate the role of ATRX in neurons that had not been treated with IFNα. ATRX, unlike PML and DAXX, is highly abundant in neurons of the central nervous system52. We investigated the relative levels of ATRX in murine (SCG) and human (HD10.653) peripheral neurons in contrast to murine (primary dermal fibroblasts) and human (human foreskin fibroblasts) fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. 4I). We chose to quantify by measuring immunofluorescence staining because of the challenges of normalizing cell numbers between vastly distinct cell types and problems carrying out Western blotting for ATRX in neurons where cell numbers are low. Consistent with previous studies, we observed higher staining intensity of ATRX in neuronal cell nuclei compared to non-neuronal cells (Supplementary Fig. 4J). These results indicate that ATRX is highly abundant in neurons of the peripheral nervous system even without IFNα stimulation.

We investigated the impact of ATRX in repressing reactivation in untreated neurons. When ATRX was depleted after latency was established, we observed a significant increase in HSV-1 reactivation. We did not observe the same increase in reactivation following the depletion of PML or DAXX (Fig. 4H), again consistent with ATRX restricting HSV-1 reactivation in a manner independent of both PML and DAXX. We also observed a slight increase in the numbers of GFP-positive neurons following ATRX depletion alone in the absence of the addition of the reactivation trigger (Supplementary Fig. 4K). This increase in GFP-positive neurons was small (from an average of 1.7 to 4) and was lower than the numbers observed with a reactivation trigger. The increase in GFP could be blocked by an inhibitor of the DLK-dependent neuronal cell stress pathway, suggesting that the increase in GFP reflects an increase in spontaneous reactivation as a result of low levels of stress in the neuronal cultures as opposed to ATRX depletion directly inducing reactivation. In summary, our data indicate ATRX plays a role in limiting HSV reactivation, and its accumulation on viral genomes increases in IFNα-pretreated neurons in a manner reliant on PML-NB formation.

ATRX is maintained on viral genomes with H3K9me3

As ATRX functioned to inhibit HSV-1 reactivation in both mock and IFNα-treated conditions and ATRX enrichment levels mirrored those for H3K9me3, we hypothesized that ATRX restricted HSV-1 reactivation through its ability to read H3K9me3. To test this hypothesis, we performed immunofluorescence to assess the co-enrichment of ATRX and H3K9me3 on the viral genome during latency at the single genome level (Fig. 5A). By using NucSpotA with the previously defined cut-offs for positive co-localization, we could determine the co-enrichment values for H3K9me3 and ATRX. We found that treatment with interferon at the time of infection increased the population of neurons co-enriched with ATRX and H3K9me3 from 36% in untreated to 61% in IFNα pulsed (Fig. 5B). In both mock and interferon conditions, there was small population of neurons with only H3K9me3 (14% in both conditions) or only ATRX (12% in mock and 16% in interferon pulsed). Genomes positively co-localized with one tend to be co-localized with both. This pattern implies that the presence or absence of one factor may influence or depend on the other, reflecting interdependence or cooperative roles for ATRX and H3K9me3. These data imply ATRX functions as an H3K9me3 reader on a subset of viral genomes and with interferon treatment, this subset increases. Depleting ATRX either before or after infection did not significantly alter the proportion of viral genomes co-localized with H3K9me3, which remained comparable to levels observed in interferon-treated neurons (Supplementary Fig. 5A). These findings support our conclusion that ATRX does not affect H3K9me3 deposition but instead likely acts downstream as a reader of this histone mark to help maintain latency.

A SCGs untreated or IFNα-treated were infected with EdC/EdA-labeled HSV-1. Fixation at 10DPI. The viral genome visualized using click chemistry, and immunofluorescence for H3K9me3 and ATRX. White arrows indicate viral genome. Scale bar, 10 μm. B Signal intensity of H3K9me3 and ATRX at the viral genome 10 DPI. Percentage of genomes above or below the co-localization threshold (H3K9me3 = 1.1 and ATRX = 1.5) represented as a bar graph. N > 60 cells from 3 biological replicates. C, D Infected SCGs untreated (C) or IFNα-treated (D) were depleted of ATRX using shRNAs at 5 DPI. RNA collected 18 h following LY294002. RT-qPCR used to quantify IE (ICP27), E (ICP8), and L (gC) viral gene expression. Analysis with two-tailed t test or Mann–Whitney test (C: ****p < 0.0001, D: **P = 0.0072; **p = 0.0017; ***p = 0.0003). C N = 9 from 3 independent dissections. D N = 12 from 4 independent dissections. E, F Infected SCGs untreated (E) or IFNα-treated (F) were depleted of ATRX using shRNA at 5 DPI. HSV-1 reactivation quantified by Us11-GFP positive neurons 2 days after LY294002 and DMSO or ML-324 (10 μM; KDM4 inhibitor) treatment. E N = 15 from 5 independent dissections. F N = 9 from 3 independent dissections. Analysis with two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test (E; ***0.0003; F: *p = 0.0115). G Model of (E, F) mechanism. ML-324 Inhibits KDM4. Created in BioRender. Whitford, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/04la4oh. H SCGs untreated or IFNα-treated were infected with EdC/EdA-labeled HSV-1. Fixation at 18 h post-reactivation stimulus. Viral genome visualized using click chemistry, and immunofluorescence done for H3K9me3S10p and ATRX. White arrows indicate viral genome. Scale bar, 10 μm. I Signal intensity of ATRX at the viral genome 10 DPI or 18 h post-reactivation stimulus. Each data point represents one viral genome. Percentages indicate proportion of genomes with NucSpotA intensity ratios above the co-localization threshold (dashed line). N > 60 cells from 3 biological replicates. Analysis with Mann–Whitney. J Signal intensity of H3K9me3S10p and ATRX at the viral genome 18 h post-reactivation stimulus. The percentage of genomes above or below the co-localization threshold (H3K9me3S10p = 1.5 and ATRX = 1.5) are represented as a bar graph. N > 60 cells from 3 biological replicates. Data represent the mean ± SEM.

We investigated the enrichment of ATRX at viral genomes following a reactivation stimulus. Previous studies6,32,33,34 have established that reactivation of HSV-1 occurs in two distinct phases. During Phase I, a stress stimulus leads to a JNK-dependent phosphorylation of the serine residue adjacent to lysine 9 on histone H3 (H3K9me3S10ph)33,35. This “methyl/phospho switch” occurs on cellular chromatin during stress, resulting in the eviction of some H3K9me3 readers that are unable to remain bound after S10ph, allowing for transcription without the removal of post-translational modifications. However, ATRX exhibits the capability to bind to H3K9me3 even in the presence of S10ph, maintaining cellular heterochromatic silencing24. Thus far, we have determined the effect of ATRX on Phase II of reactivation via GFP assay. We sought to determine if ATRX prevents entry into Phase I (instead of the progression from Phase I to Phase II). Depletion of ATRX after latency was established resulted in increased viral lytic gene expression in all viral gene classes (ICP27, ICP8, and gC) at Phase I (18 h post-reactivation). This ATRX-dependent increase was observed in both mock-treated (Fig. 5C) and IFNα pre-treated neurons (Fig. 5D) and was independent of DAXX as depletion of DAXX after latency had been established did not impact Phase I (Supplementary Fig. 5B). Therefore, ATRX acts independently of DAXX to prevent the exit of latent genomes into Phase I gene expression following a reactivation stimulus.

Phase II of reactivation involves repressive PTM removal, replication of viral DNA, and virus production. The removal of histone PTMs H3K27me3 and H3K9me2 is required for Phase II of reactivation6,32,33,34. However, we found that the removal of H3K9me3 does not contribute to reactivation, as the use of a H3K9me3 demethylase (KDM4) inhibitor (ML-324) had no effect on reactivation in both mock (Fig. 5E) and IFNα (Fig. 5F) treated neurons. Yet, when ATRX was depleted before reactivation, we found that the histone demethylase inhibitor decreased reactivation. This suggests that when ATRX is not present, H3K9me3 removal contributes to Phase II of reactivation (Fig. 5G). This supports the hypothesis that ATRX functions as a reader of H3K9me3 on latent genomes, preventing H3K9me3-associated genomes from reactivating.

To investigate the mechanism by which ATRX prevents H3K9me3-associated genomes from reactivating, we asked whether H3K9me3-enriched genomes were phosphorylated during Phase I when associated with ATRX. We performed immunofluorescence on HSV-1-infected neurons, either untreated or IFNα-treated, during initial infection (Fig. 5H). ATRX enrichment on the viral genome was not significantly different at latent and Phase I time points (Fig. 5I). Furthermore, quantification of both ATRX and H3K9me3pS10 at viral genomes using NucSpotA revealed that ATRX and H3K9me3S10p are co-enriched on 25% of genomes in untreated neurons and 59% of IFNα-treated neurons during Phase I (Fig. 5J). These data suggest ATRX genomes are still capable of becoming phosphorylated even when bound by ATRX, but ATRX association is not lost upon following a phospho/methyl switch during Phase I. Together, our data indicate that ATRX functions as a restriction factor against HSV-1 reactivation by remaining bound to viral genomes even following the initial epigenetic changes known to occur during Phase I of reactivation (a phospho/methyl switch) and prevents Phase I lytic gene expression. Further, ATRX and H3K9me3 association is increased in IFNα-treated neurons, showing the innate immune memory response in neurons that restricts HSV-1 reactivation.

Discussion

It was known that different histone post-translation modifications, including H3K9me2, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3, are enriched on the latent viral genome1,2,3. However, how histone post-translational modifications arise and whether epigenetic heterogeneity impact reactivation competency was unknown. The restriction of latency is affected by neuronal states such as stress and immune signaling9,10, but whether these processes impacted the viral epigenetics was unclear. Here, we demonstrate that immune signaling at the time of infection impacts viral heterochromatin by promoting more H3K9me3 association and restricting reactivation. Furthermore, we demonstrate mechanistically how this form of heterochromatin is refractory to reactivation via the epigenetic reader ATRX (Fig. 6). Importantly, this data demonstrate that certain epigenetic structures on the latent viral genome are more silenced and can be induced by IFNα during initial infection.

Model depicting latent HSV-1 infection. Under mock conditions (top panel), a population of viral genomes are enriched with H3K9me3 and ATRX, but there also exists a population (almost 40%- Fig. 5) that have neither. When neurons are treated with type I IFN at the time of infection (bottom panel), there is an increase in the population of genomes enriched with H3K9me3 (from 50% to 75%) that is dependent on PML and DAXX. When both mock and interferon-treated neurons are stimulated with a reactivation trigger, ATRX restricts H3K9me3-bound genomes from reactivating. Created in BioRender. Cliffe, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/z25g307.

Prior to this study, there was little information describing the nature of histone readers that are maintained at latent HSV-1 genomes. We demonstrate ATRX is an important H3K9me3 reader associated with the viral genome. In the future, work should investigate the impact of other H3K9me3 readers on latency and reactivation. ATRX is highly abundant in neurons and displays a differential localization in comparison to non-neuronal cells. Our observations confirm a previous study, demonstrating ATRX remains bound following histone phosphorylation, maintains heterochromatin in neurons in times of cell stress24. Our data extends this role for ATRX during viral reactivation. ATRX maintains heterochromatin silencing on the HSV-1 genome independently of DAXX, as DAXX depletion at latent time points had no impact on Phase I of reactivation. This contrasts with lytic infection of HSV-1, where ATRX and DAXX function together41, showing that mechanism of ATRX during HSV-1 infection in neurons is distinct. This distinct role for ATRX may help explain why HSV-1 latency is exclusively established in neurons. While our findings demonstrate a role for ATRX in maintaining HSV-1 latency, it has not been determined whether ATRX also contributes to the establishment of silencing during HSV-1 neuronal infection and, if so, whether it acts independently of DAXX and PML. Future work should expand upon our in vitro observations with a singular stimulus to investigate the more complex neuronal environments of in vivo models, for example, using neuronal-specific knock-out of the type I IFN receptor, or Daxx and Atrx. These experiments would validate our findings, confirming a role for ATRX restriction of reactivation in vivo, and open new avenues of investigation for additional immune and stress stimuli.

PML-NBs are typically abundant in non-neuronal cells but are much less abundant in the mouse nervous system, with Pml mRNA and protein levels significantly downregulated in post-mitotic neurons54,55. PML-NBs are undetectable in post-natal and adult primary neurons cultured in vitro from the superior cervical and trigeminal ganglia10. Consistently, others report subpopulations of neurons have variability and even lack PML signals5,56. We show oxygen conditions also impact the formation of PML-NBs. PML-NBs can be formed as a response to oxidative stress, and the nucleation of these nuclear bodies is mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced oxidation of PML proteins57. Furthermore, interferon signaling can induce the accumulation of ROS in neurons58, suggesting a possible mechanism by which PML-NB formation may be distinct in different oxygen culturing conditions. Here we find that PML-NBs are only formed for a short period after IFNα stimulation and do not persist, nor colocalize with the latent viral genome, during latency when neurons are cultured in biologically relevant oxygen conditions. Other studies have observed at latency in vivo, the HSV-1 genome and PML were co-localized with DAXX5. Differences in prior studies may reflect variable exposure to signaling molecules like interferons. Regardless, using our pared-down model, we determine PML-NBs can modulate epigenetics during latency establishment and that ATRX can restrict HSV-1 reactivation in genomes that were once, but no longer, associated with PML-NBs.

Viral genomes enriched with H3K9me3 and ATRX are prevented from entering Phase I of HSV-1 reactivation. The signaling cascade that initiates Phase I of reactivation results in a JNK-dependent methyl/phospho switch and a burst of lytic gene expression6,33,34,35. This burst then allows for the expression of viral proteins, such as the viral transactivator VP16, that are then hypothesized to promote full viral gene expression and Phase II of reactivation32. In this study, we observe that the methyl/phospho switch occurs on genomes during Phase I of reactivation, but ATRX remains bound and inhibits Phase I transcription, thereby inhibiting VP16 expression and Phase II of reactivation. IFNα-treated neurons have an increased population of genomes associated with ATRX and H3K9me3 and a decreased population of reactivation-competent genomes. In mock conditions, we observe few genomes independently enriched with either ATRX or H3K9me3. In these independently enriched populations, it is possible that an alternative H3K9me3 reader, such as HP1, is displaced via a methyl/phospho switch, facilitating the transition to Phase I. In both the mock and interferon treatments, the subset of latent genomes lacking both ATRX and H3K9me3 may represent the reactivation-competent population. For example, it is possible for H3K27me3, a mark observed on latent viral genomes1,2, has a methyl/phospho switch (H3K27me3S28p)59, although this mark has yet to be identified on the reactivating HSV-1 genome. Future work should explore the other forms of heterochromatin present in the heterogeneous pool of genomes and whether other forms of chromatin are more reactivation-competent.

Full reactivation using a PI3K inhibitor or forskolin in primary neuronal models of reactivation6,32,33,35,60 as well as ex vivo models34 requires the activities of H3K9me2 and H3K9me2/3 demethylases. KDM4 (also known as JMJD2 or JHDM3), a histone demethylase with a preference for H3K9me3, also promotes HSV-1 gene expression during axotomy-induced reactivation induced61. We find that inhibiting KDM4 did not affect Phase II of reactivation in vitro. Only when ATRX was depleted did inhibiting H3K9me3 removal contribute to reactivation. This supports the hypothesis that ATRX functions as a reader of H3K9me3 on latent genomes, preventing H3K9me3-associated genomes from reactivating. The variation in KDM4 inhibition during reactivation triggered by different stimuli suggests that the kinetics of reactivation may vary depending on the type of stimulus. Previously, differential kinetics have already been observed with axotomy, with rapid recruitment of transcription factors62,63, earlier occurrence of Phase I34, and reactivation occurring independently of the viral transactivator, VP1664,65. This implies that distinct stimuli could influence the timing, dynamics, viral and host (restriction) factors involved in reactivation. Understanding these differences could provide insights into how specific factors modulate viral latency and reactivation, potentially leading to new therapeutic strategies.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of long-lasting epigenetic changes to neurons in response to an immune stimulus. Immune memory may serve as a mechanism through which a persistent virus modulates latency and its potential to reactivate. By altering the chromatin structure of the viral genome, immune memory can suppress reactivation under certain conditions, effectively limiting viral spread. However, this same mechanism might also enable the virus to remain latent while evading immune detection, ensuring its long-term survival within the host. Memory of previous immune stimulation in a long-lived and non-replenishing cell type, could also impact the regulation of host genes, potentially modulating neuronal function over time. Therefore, more work is needed to determine the implications for immune memory in long-term inflammation in the nervous system and the development of neuropathologies, including neurodegenerative diseases or chronic pain syndromes.

Methods

Reagents

The reagents used in this study are described in the table below (Supplementary Table 1):

Preparation of HSV-1 virus stocks

Stayput-GFP virus was made and titered using gH-complementing Vero F6 cells as described previously6. The Vero F6 cells were obtained from Gary Cohen (University of Pennsylvania) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco), supplemented with 10% FetalPlex (Gemini Bio-Products) and 250 μg/mL of G418/Geneticin (Gibco).

Primary neuronal cultures

Sympathetic neurons from the SCG of post-natal day 0–2 (P0–P2) CD1 Mice (Charles River Laboratories) were dissected as previously described33. Rodent handling and husbandry were carried out under animal protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia, protocol number 4134. Ganglia were briefly kept in Leibovitz’s L-15 media with 2.05 mM L-glutamine before dissociation in collagenase type IV (1 mg/ml) followed by trypsin (2.5 mg/ml) for 20 min each at 37 °C. Dissociated ganglia were triturated, and approximately 10,000 neurons per well were plated onto rat tail collagen in a 24-well plate. Sympathetic neurons were maintained in CM1 (Neurobasal® Medium supplemented with PRIME-XV IS21 Neuronal Supplement (Irvine Scientific), 50 ng/ml Mouse NGF 2.5S, 2 mM L-Glutamine, and Primocin). Aphidicolin (3.3 µg/ml) was added to the CM1 for the first five days post-dissection to select against proliferating cells.

Latent HSV-1 infection in primary neurons

Latent HSV-1 infection was established in P6-8 sympathetic neurons from the SCG. Neurons were cultured for at least two days without antimitotic agents prior to infection. Where indicated, neurons were pre-treated for 18 h and then infected in the presence of IFNα (600 IU/ml) as previously described10. The cultures were infected with Stayput Us11-GFP at an of MOI 5 PFU/cell (assuming 10,000 cells per well) in Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline + CaCl2 + MgCl2 supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum, 4.5 g/L-glucose, and 10 μM ACV for 4 h at 37 °C. The inoculum was replaced with CM1 containing 50 μM ACV. 8 days post-infection, ACV was washed out and replaced with CM1 alone. Reactivation was initiated 10 days post-infection by adding Reactivation media [BrainPhys with 10% fetal bovine serum, Mouse NGF 2.5S (50 ng/ml)] and 20 μM LY294002 (Tocris). Reactivation was quantified by counting GFP-positive neurons 48 h after the reactivation trigger was added.

Culturing and differentiation of HD10.6 cells

The human dorsal root sensory ganglion (HD10.6) cell line was a gift from the Triezenberg Lab and cultured as previously described66. HD10.6 cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and passaged in proliferation media (advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with glutaMAX, B-27 supplement, prostaglandin, and bFGF). Proliferating HD10.6 cells were grown on Nunc flasks coated with human fibronectin. HD10.6 cells destined for differentiation were plated onto German Glass coverslips (Cat. #72290, Electron Microscopy Science) coated with PLO and human fibronectin at a concentration of 50,000 cells/ well. 18 h after plating, maturation media [Neurobasal® Medium supplemented with PRIME-XV IS21 Neuronal Supplement, NGF, L-Glutamine, Primocin, ciliary neurotrophic factor, glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor, and neurotrophin-3] containing doxycycline was added to induce differentiation. Following the addition of doxycycline, half-volume medium changes were performed every 3 days until cells were fixed 10 days post-differentiation for immunofluorescence.

Analysis of mRNA expression by RT-qPCR

To assess relative expression of HSV-1 lytic mRNA, total RNA was extracted from approximately 1.0 × 104 neurons using the Quick-RNA™ Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) with an on-column DNase I digestion. Following extraction, mRNA underwent a reverse transcription reaction using Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) (Fisher Scientific) and random hexamers for first-strand synthesis to produce cDNA. Equal amounts of RNA (20–30 ng/reaction) were used per cDNA reaction. qPCR was carried out using Power SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The relative mRNA was determined using the comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method, normalized to mRNA levels in control samples. Viral mRNAs were normalized to mouse reference gene 18S. All samples were run in duplicate on an Applied Biosystems™ QuantStudio™ 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System and the mean fold change compared to the reference gene calculated. Primers used are described in Supplementary Table 2.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed in a solution containing 1.8% methanol-free formaldehyde in CSK buffer (10 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 300 mM Sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA) with 0.5% Triton ×-100 and 1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride for 10 min. Following fixation, cells were washed three times with PBS and were then blocked for one hour using 3% bovine serum albumin. Cells were then incubated for one hour with primary antibody at room temperature with concentrations specified in Supplementary Table 2. Following the primary antibody treatment, the neurons were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488-, 555-, and 647-conjugated secondary antibodies for one hour. To visualize the nuclei, cells were incubated in Hoechst stain for 30 min. After all incubation times, cells were washed three times with PBS.

Images were captured using a Zeiss LSM900 microscope with Airyscan capabilities at 60x. Images were processed using the ZenBlue software and then further analyzed and processed using ImageJ.

Click Chemistry

SCGs were infected with EdC/EdA virus at an MOI of 7. Labeled virus was prepared using a previously described method67. Click chemistry was carried out as described previously10. Following fixation protocol described for immunofluorescence, samples were incubated in samples from Click-iT EdU Alexa Flour 555 Imaging Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, C10638) following the manufacturers instructions using AFDye 555 Azide Plus. Samples were incubated in this solution for thirty minutes then washed ×3 in PBS. Following the click reaction, the immunofluorescence protocol was performed.

NucSpotA analysis

NucSpotA is part of the Mitogenie suite and was used as previously described17. Rotation control images were generated from original channel combination images using FIJI, prior to analysis with NucSpotA. The stated co-localization thresholds were blindly calibrated by eye.

Preparation of lentiviral vectors

Lentiviruses expressing shRNA against PML (TRCN0000314605- validated previously10), DAXX (DAXX-1 TRCN0000218672, DAXX-2 TRCN0000225715), ATRX (ATRX-1 TRCN0000302074, ATRX-2 TRCN0000081910), or a control lentivirus shRNA (pLKO.1 vector expressing a non-targeting shRNA control) were prepared by co-transfection with psPAX2 and pCMV-VSV-G68 using the 293LTV packaging cell line (Cell Biolabs). Supernatant was harvested at 40- and 64-h post-transfection and filtered using a 45 μM PES filter. Sympathetic neurons were transduced overnight in neuronal media containing 8 μg/ml protamine sulfate and 50 μM ACV.

Knockout in floxed SCG neurons

Sympathetic neurons from the SCG of post-natal transgenic floxed mice were dissected and processed as above. These SCGs were used to specifically knock-out ATRX52 and PML69 in floxed neurons in vitro using peripheral neuron targeting AAV from UNC GTC Vector core for delivery of control (rAAV2/hSyn-mcherry) or CRE (rAAV2/hSyn-mcherry-CRE). Sympathetic neurons were infected overnight in neuronal media containing 8 μg/ml protamine sulfate and 50 μM ACV.

CUT&Tag

CUT&Tag was carried out on latent neuronal cultures (approximately 1.2 × 105 neurons per reaction) using the Epicypher CUTANA CUT&Tag Kit and workflow (14-1102). Antibodies used for CUT&RUN are included in Supplementary Table 3. Dual-indexed DNA libraries were prepared using the same kit. Pair-ended, partial lane sequencing and de-multiplexing were carried out using NovaSeq (Novogene). Data analysis was performed using Galaxy, command line, and R code, and workflow, adapted from the cited tutorial. The Rivanna high-performance computing environment (UVA Research Computing) was used for the command line data processing. Data was aligned to mouse (mm39) and viral [SC16; KX94697070] genomes using Bowtie2. Cutadapt was used to trim i5 and i7 adapters. Bam files were converted to Bed files using samtools. Bed files were converted to Bedgraph files using bedtools. Bedgraph files were normalized to total mapped reads for host (mouse), virus (SC16), and the K Met Stat panel. Bedgraph files were visualized in Integrative Genome Viewer viewer, exported as SVG files, and made into figures using Inkscape. CUT&Tag experiments were repeated twice for a total of 2 biological replicates. The sum of enrichment at viral promoters and genes was used using bedtools map. To compare mock-treated and interferon-treated samples, each interferon-treated replicate was normalized by dividing it by its corresponding mock-treated replicate. Promoters and genes showing a twofold or greater increase or decrease in the enrichment sum were considered consistent. In Galaxy, Bam files were visualized using DeepTools bamcoverage with a bin size of 1 to generate bigwig files. Bigwig files were normalized to total mapped reads for host (mouse), virus (SC16), and the K Met Stat panel. Bigwig files were used for multiBigwigSummary to generate heatmaps. Spearman correlation analysis was performed using deeptools plotCorrelation on multiBigwigSummary.

Statistical analysis

Power analysis was used to determine the appropriate sample sizes for statistical analysis. All statistical analysis was performed using Prism V10. The normality of the data was determined with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Specific analyses are included in the figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare (10.1101/2025.01.28.633013). The CUT&Tag dataset generated and analyzed in the current study is available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE306427). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Cliffe, A. R., Garber, D. A. & Knipe, D. M. Transcription of the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript promotes the formation of facultative heterochromatin on lytic promoters. J. Virol. 83, 8182–8190 (2009).

Kwiatkowski, D. L., Thompson, H. W. & Bloom, D. C. The polycomb group protein Bmi1 binds to the herpes simplex virus 1 latent genome and maintains repressive histone marks during latency. J. Virol. 83, 8173–8181 (2009).

Wang, Q. Y. et al. Herpesviral latency-associated transcript gene promotes assembly of heterochromatin on viral lytic-gene promoters in latent infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16055–16059 (2005).

Maroui, M. A. et al. Latency entry of herpes simplex virus 1 is determined by the interaction of its genome with the nuclear environment. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005834 (2016).

Catez, F. et al. HSV-1 genome subnuclear positioning and associations with host-cell PML-NBs and centromeres regulate LAT locus transcription during latency in neurons. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002852 (2012).

Dochnal et al. DLK-dependent biphasic reactivation of herpes simplex virus latency established in the absence of antivirals. J. Virol. 96, e0050822 (2022).

Sawtell, N. M. & Thompson, R. L. Comparison of herpes simplex virus reactivation in ganglia in vivo and in explants demonstrates quantitative and qualitative differences. J. Virol. 78, 7784–7794 (2004).

Ma, J. Z., Russell, T. A., Spelman, T., Carbone, F. R. & Tscharke, D. C. Lytic gene expression is frequent in HSV-1 latent infection and correlates with the engagement of a cell-intrinsic transcriptional response. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004237 (2014).

Dochnal, S. A. et al. c-Jun signaling during initial HSV-1 infection modulates latency to enhance later reactivation in addition to directly promoting the progression to full reactivation. J. Virol. 98, e0176423 (2024).

Suzich, J. B. et al. PML-NB-dependent type I interferon memory results in a restricted form of HSV latency. EMBO Rep. 22, e52547 (2021).

Lallemand-Breitenbach, V. & de The, H. PML nuclear bodies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000661 (2010).

Everett, R. D. & Murray, J. ND10 components relocate to sites associated with herpes simplex virus type 1 nucleoprotein complexes during virus infection. J. Virol. 79, 5078–5089 (2005).

Everett, R. D. et al. The disruption of ND10 during herpes simplex virus infection correlates with the Vmw110- and proteasome-dependent loss of several PML isoforms. J. Virol. 72, 6581–6591 (1998).

Everett, R. D., Sourvinos, G., Leiper, C., Clements, J. B. & Orr, A. Formation of nuclear foci of the herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein ICP4 at early times of infection: localization, dynamics, recruitment of ICP27, and evidence for the de novo induction of ND10-like complexes. J. Virol. 78, 1903–1917 (2004).

Alandijany, T. et al. Distinct temporal roles for the promyelocytic leukaemia (PML) protein in the sequential regulation of intracellular host immunity to HSV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006769 (2018).

Dochnal, S. A., Francois, A. K. & Cliffe, A. R. De novo polycomb recruitment: lessons from latent herpesviruses. Viruses 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13081470 (2021).

Francois, A. K. et al. Single-genome analysis reveals a heterogeneous association of the herpes simplex virus genome with H3K27me2 and the reader PHF20L1 following infection of human fibroblasts. mBio 15, e0327823 (2024).

Delbarre, E. et al. PML protein organizes heterochromatin domains where it regulates histone H3.3 deposition by ATRX/DAXX. Genome Res. 27, 913–921 (2017).

Lee, J. S., Raja, P. & Knipe, D. M. Herpesviral ICP0 protein promotes two waves of heterochromatin removal on an early viral promoter during lytic infection. mBio 7, e02007–e02015 (2016).

Jacobs, S. A. et al. Specificity of the HP1 chromo domain for the methylated N-terminus of histone H3. EMBO J. 20, 5232–5241 (2001).

Bannister, A. J. et al. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410, 120–124 (2001).

Lachner, M., O’Carroll, D., Rea, S., Mechtler, K. & Jenuwein, T. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature 410, 116–120 (2001).

Dhayalan, A. et al. The ATRX-ADD domain binds to H3 tail peptides and reads the combined methylation state of K4 and K9. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 2195–2203 (2011).

Noh, K. M. et al. ATRX tolerates activity-dependent histone H3 methyl/phos switching to maintain repetitive element silencing in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6820–6827 (2015).

Mansfield, R. E. et al. Plant homeodomain (PHD) fingers of CHD4 are histone H3-binding modules with preference for unmodified H3K4 and methylated H3K9. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11779–11791 (2011).

Jain, K. et al. Characterization of the plant homeodomain (PHD) reader family for their histone tail interactions. Epigenetics Chromatin 13, 3 (2020).

Nady, N. et al. Recognition of multivalent histone states associated with heterochromatin by UHRF1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24300–24311 (2011).

Zhao, S. et al. TNRC18 engages H3K9me3 to mediate silencing of endogenous retrotransposons. Nature 623, 633–642 (2023).

Chang, Y., Horton, J. R., Bedford, M. T., Zhang, X. & Cheng, X. Structural insights for MPP8 chromodomain interaction with histone H3 lysine 9: potential effect of phosphorylation on methyl-lysine binding. J. Mol. Biol. 408, 807–814 (2011).

Sun, Y. et al. Histone H3 methylation links DNA damage detection to activation of the tumour suppressor Tip60. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1376–1382 (2009).

Cao, R. et al. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 298, 1039–1043 (2002).

Kim, J. Y., Mandarino, A., Chao, M. V., Mohr, I. & Wilson, A. C. Transient reversal of episome silencing precedes VP16-dependent transcription during reactivation of latent HSV-1 in neurons. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002540 (2012).

Cliffe, A. R. et al. Neuronal stress pathway mediating a histone methyl/phospho switch is required for herpes simplex virus reactivation. Cell Host Microbe 18, 649–658 (2015).

Whitford, A. L. et al. Ex vivo herpes simplex virus reactivation involves a dual leucine zipper kinase-dependent wave of lytic gene expression that is independent of histone demethylase activity and viral genome synthesis. J. Virol. 96, e0047522 (2022).

Cuddy, S. R. et al. Neuronal hyperexcitability is a DLK-dependent trigger of herpes simplex virus reactivation that can be induced by IL-1. Elife 9, e58037 (2020).

Camarena, V. et al. Nature and duration of growth factor signaling through receptor tyrosine kinases regulates HSV-1 latency in neurons. Cell Host Microbe 8, 320–330 (2010).

Kobayashi, M., Wilson, A. C., Chao, M. V. & Mohr, I. Control of viral latency in neurons by axonal mTOR signaling and the 4E-BP translation repressor. Genes Dev. 26, 1527–1532 (2012).

Zochodne, D. W. & Ho, L. T. Unique microvascular characteristics of the dorsal root ganglion in the rat. Brain Res. 559, 89–93 (1991).

Erecinska, M. & Silver, I. A. Tissue oxygen tension and brain sensitivity to hypoxia. Respir. Physiol. 128, 263–276 (2001).

Dochnal, S. A., Krakowiak, P. A., Whitford, A. L. & Cliffe, A. R. Physiological oxygen concentration during sympathetic primary neuron culture improves neuronal health and reduces HSV-1 reactivation. Microbiol. Spectr. 12, e0203124 (2024).

Lukashchuk, V. & Everett, R. D. Regulation of ICP0-null mutant herpes simplex virus type 1 infection by ND10 components ATRX and hDaxx. J. Virol. 84, 4026–4040 (2010).

Cabral, J. M., Oh, H. S. & Knipe, D. M. ATRX promotes maintenance of herpes simplex virus heterochromatin during chromatin stress. Elife 7, e40228 (2018).

Cabral, J. M., Cushman, C. H., Sodroski, C. N. & Knipe, D. M. ATRX limits the accessibility of histone H3-occupied HSV genomes during lytic infection. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009567 (2021).

Cohen, C. et al. Promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies (NBs) induce latent/quiescent HSV-1 genomes chromatinization through a PML NB/Histone H3.3/H3.3 chaperone axis. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1007313 (2018).

Lewis, P. W., Elsaesser, S. J., Noh, K. M., Stadler, S. C. & Allis, C. D. Daxx is an H3.3-specific histone chaperone and cooperates with ATRX in replication-independent chromatin assembly at telomeres. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14075–14080 (2010).

Drane, P., Ouararhni, K., Depaux, A., Shuaib, M. & Hamiche, A. The death-associated protein DAXX is a novel histone chaperone involved in the replication-independent deposition of H3.3. Genes Dev. 24, 1253–1265 (2010).

Voon, H. P. et al. ATRX plays a key role in maintaining silencing at interstitial heterochromatic loci and imprinted genes. Cell Rep. 11, 405–418 (2015).

Roubille, S. et al. The HUSH epigenetic repressor complex silences PML nuclear body- associated HSV-1 quiescent genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2412258121 (2024).

Henikoff, S., Henikoff, J. G., Kaya-Okur, H. S. & Ahmad, K. Efficient chromatin accessibility mapping in situ by nucleosome-tethered tagmentation. eLife 9, e63274 (2020).

Lee, M. Y. et al. Epigenome signatures landscaped by histone H3K9me3 are associated with the synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell 19, e13153 (2020).

Valenzuela, M., Amato, R., Sgura, A., Antoccia, A. & Berardinelli, F. The multiple facets of ATRX protein. Cancers (Basel) 13, 2211 (2021).

Berube, N. G. et al. The chromatin-remodeling protein ATRX is critical for neuronal survival during corticogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 258–267 (2005).

Raymon, H. K. et al. Immortalized human dorsal root ganglion cells differentiate into neurons with nociceptive properties. J. Neurosci. 19, 5420–5428 (1999).

Gray, P. A. et al. Mouse brain organization revealed through direct genome-scale TF expression analysis. Science 306, 2255–2257 (2004).

Regad, T., Bellodi, C., Nicotera, P. & Salomoni, P. The tumor suppressor Pml regulates cell fate in the developing neocortex. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 132–140 (2009).

Hall, M. H. et al. Localization and regulation of PML bodies in the adult mouse brain. Brain Struct. Funct. 221, 2511–2525 (2016).

Sahin, U. et al. Oxidative stress-induced assembly of PML nuclear bodies controls sumoylation of partner proteins. J. Cell Biol. 204, 931–945 (2014).

Alboni, S. et al. N-acetyl-cysteine prevents toxic oxidative effects induced by IFN-alpha in human neurons. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16, 1849–1865 (2013).

Gehani, S. S. et al. Polycomb group protein displacement and gene activation through MSK-dependent H3K27me3S28 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell 39, 886–900 (2010).

Hu, H. L. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics identifies Gadd45b as a regulator of herpesvirus-reactivating neurons. EMBO Rep. 23, e53543 (2022).

Liang, Y. et al. Targeting the JMJD2 histone demethylases to epigenetically control herpesvirus infection and reactivation from latency. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 167ra165 (2013).

Whitlow, Z. & Kristie, T. M. Recruitment of the transcriptional coactivator HCF-1 to viral immediate-early promoters during initiation of reactivation from latency of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 83, 9591–9595 (2009).

Kristie, T. M., Vogel, J. L. & Sears, A. E. Nuclear localization of the C1 factor (host cell factor) in sensory neurons correlates with reactivation of herpes simplex virus from latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1229–1233 (1999).

Sears, A. E., Hukkanen, V., Labow, M. A., Levine, A. J. & Roizman, B. Expression of the herpes simplex virus 1 alpha transinducing factor (VP16) does not induce reactivation of latent virus or prevent the establishment of latency in mice. J. Virol. 65, 2929–2935 (1991).

Steiner, I. et al. A herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant containing a nontransinducing Vmw65 protein establishes latent infection in vivo in the absence of viral replication and reactivates efficiently from explanted trigeminal ganglia. J. Virol. 64, 1630–1638 (1990).

Thellman, N. M., Botting, C., Madaj, Z. & Triezenberg, S. J. An immortalized human dorsal root ganglion cell line provides a novel context to study herpes simplex virus 1 latency and reactivation. J. Virol. 91, e00080–17 (2017).

McFarlane, S. et al. The histone chaperone HIRA promotes the induction of host innate immune defences in response to HSV-1 infection. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1007667 (2019).

Stewart, S. A. et al. Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA 9, 493–501 (2003).

Guarnerio, J. et al. A non-cell-autonomous role for Pml in the maintenance of leukemia from the niche. Nat. Commun. 9, 66 (2018).

Rastrojo, A., Lopez-Munoz, A. D. & Alcami, A. Genome sequence of herpes simplex virus 1 strain SC16. Genome Announc. 5, e01392–16 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01NS135166 (A.R.C.), T32AI007046 (A.L.W.), MRC awards MC_UU_12014/5 and MC_UU_00034/2 (C.B.), and Canadian Institutes of Health Research PJT165994 (D.J.P.). psPAX2 and pMD2.G were gifts from Didier Trono (Addgene plasmid #s12260; http://n2t.net/addgene:12260; RRID:Addgene_12260 and 12259; http://n2t.net/addgene:12259; RRID:Addgene_12259). The Pml floxed mice were provided by Pier Paolo Pandolfi (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.W. and A.R.C.; experimentation, A.L.W.; analysis, A.L.W., G.A., A.K.F., C.M., and S.D.; artwork, A.L.W.; Resources: D.J.P., C.B., A.R.C., writing—original draft, A.L.W. and A.R.C.; writing—review & editing, A.L.W., S.D., and A.R.C.; funding acquisition, A.L.W. and A.R.C.; supervision, A.R.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Whitford, A.L., Auguste, G., Francois, A.K. et al. Interferon dependent immune memory during HSV-1 neuronal latency via increased H3K9me3 and restriction by ATRX. Nat Commun 17, 34 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66477-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66477-2