Abstract

Perturbed DNA replication can lead to incompletely replicated DNA when cells enter mitosis and can interfere with chromosome segregation. Cells therefore require mechanisms to resolve these lesions during mitosis. The CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex is described to tether fragmented DNA molecules during mitosis. Whether CIP2A also functions in processing of incompletely replicated DNA remained unclear. We show that CIP2A-TOPBP1 form large filamentous structures at sites of incomplete DNA replication during mitosis, and that CIP2A-TOPBP1 facilitate the recruitment of SMX tri-nuclease complex members SLX4, MUS81 and XPF-ERCC1. These structures form in proximity to sites of mitotic DNA synthesis, although CIP2A is not required for mitotic DNA synthesis. In addition to its globular and coiled-coil domain, the unstructured C-terminal domain of CIP2A is essential for CIP2A-TOPBP1 filamentous structure formation and recruitment of the SMX complex. BRCA1-/- and BRCA2-/- cells have increased mitotic DNA lesions that recruit CIP2A and SLX4. We show that the C-terminal part of CIP2A is required for survival of BRCA2-/- cells. Moreover, SLX4 is crucial for genome stability in BRCA2-/- cells. Combined, we demonstrate that CIP2A-TOPBP1 recruits the SMX complex during mitosis, which is required to resolve mitotic DNA lesions, allows faithful chromosome segregation and maintain viability of BRCA2-/- cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DNA replication is a vital process in all biological systems. To faithfully duplicate the entire genome, DNA replication adheres to a strict temporal and spatial program1. Even under physiological conditions, DNA replication is challenged by intrinsic properties of some genomic regions that are difficult to replicate2, while also chemical modifications of DNA can perturb replication3,4,5. In cancer cells, however, many additional processes lead to perturbed DNA replication6,7. For instance, oncogene activation leads to uncoordinated firing of replication origins, causing collisions between the transcription and replication machinery8 and depletion of the nucleotide pool9,10. In addition, cancer-associated DNA repair defects also disrupt DNA replication. Specifically, mutations in DNA repair genes BRCA1, BRCA2 and FANCD2 cause instability of stalled replication forks and incomplete replication11,12,13,14.

Cells are equipped with several mechanisms to deal with perturbed DNA replication. For instance, when replication forks cannot progress, dormant replication origins in the vicinity of the stalled replication fork are fired to complete replication15. In addition, translesion synthesis (TLS) polymerases can replace the replicative polymerases to continue replication16. Finally, cell cycle checkpoints prevent mitotic entry when cells have extensive amounts of incompletely replicated DNA or unrepaired DNA lesions17. Nevertheless, despite the presence of these protective mechanisms, cancer cells frequently enter mitosis with incompletely replicated DNA12,18,19.

After cells have entered mitosis, several mechanisms are available to resolve incompletely replicated DNA. First, DNA replication can be completed during mitosis by ‘mitotic DNA synthesis’ (MiDAS), which involves a dedicated DNA polymerase complex, and resembles RAD52-dependent break-induced replication (BIR)20,21. Second, several DNA endonucleases are activated during mitosis (e.g., SLX1, MUS81, XPF)22, or get access to chromosomes upon mitotic breakdown of the nuclear membrane (i.e. GEN1)23. These endonucleases can separate joint DNA molecules, allowing faithful chromosome segregation and completion of mitosis24,25. Third, incompletely replicated DNA fragments that persist into anaphase form ‘ultrafine DNA bridges’ (UFBs), marked by the recruitment of the PICH DNA translocase during anaphase26,27.28. In turn, PICH recruits the BLM-TopoIII-RMI1/2 complex26,27 and RIF129. UFBs originating from incompletely replicated DNA are subsequently converted into single-stranded DNA bridges29,30, which likely facilitates UFB breakage and allows chromosome segregation at the cost of genome instability30. The molecular regulation of these various mechanisms remains largely elusive, and it is unclear whether these pathways act in parallel or consecutively, and whether these mechanisms are part of an integrated response to incompletely replicated DNA.

The CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex was recently demonstrated to be recruited to mitotic DNA lesions31,32. The CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex tethers the two ends of double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) and prevents mis-segregation of acentric chromosome fragments31,32,33,34. Importantly, CIP2A is essential for survival of BRCA1/2 mutant cells31, which accumulate mitotic DNA lesions12,19. Interestingly, whereas TOPBP1 can be recruited to DNA lesions both during interphase and mitosis35,36,37,38, CIP2A is sequestered in the cytoplasm during interphase, and is only recruited to DSBs upon nuclear envelop breakdown during mitosis31,32. Recruitment of CIP2A and TOPBP1 to mitotic DSBs depends on the γH2AX adaptor protein MDC139, however DNA lesions induced by the replication polymerase inhibitor aphidicolin (APH) appear to be MDC1-independent31,32, showing that multiple mechanisms exist for CIP2A-TOPBP1 recruitment. APH treatment induces mitotic DNA lesions, including joint DNA molecules that likely require additional processing when compared to mitotic DSBs. However, it is currently unclear if the CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex has functions beyond the tethering of DNA ends, and functions in processing of mitotic DNA lesions induced by perturbed replication.

In this study, we used Stimulated Emission Depletion (STED) super-resolution microscopy and structure-function analysis of CIP2A to study mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 structure formation. We find that the CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex mediates recruitment of the SMX tri-nuclease complex to sites of replication-associated DNA lesions during mitosis. Recruitment of the SMX complex, facilitated by CIP2A-TOPBP1, allows for processing of DNA lesions induced by perturbed replication, and is essential for genome stability in BRCA2–/– cells.

Results

Perturbed DNA replication and irradiation result in similar CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures during mitosis

Analysis of the cellular response to mitotic DNA damage is frequently studied using irradiation of mitotic cells to induce DSBs. Since transfer of late-stage replication intermediates into mitosis is a cancer cell-intrinsic source of mitotic DNA damage, we compared CIP2A recruitment to replication stress-induced and irradiation-induced mitotic DNA damage. To this end, hTERT immortalized human retinal pigmented epithelial RPE1 TP53–/– cells were treated with the polymerase inhibitor aphidicolin (APH) or with irradiation (IR). Analysis of mitotic foci formation of CIP2A in response to low-dose APH (200 nM) or low-dose IR (0.25 Gy) confirmed that the majority of CIP2A foci co-localizes with γH2AX in mitosis, and that CIP2A recruitment to mitotic DNA lesions occurs independently of the source of DNA damage (Fig. 1a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 1A)31,32. To examine the effects of CIP2A inactivation on the response to mitotic DNA damage, RPE1 TP53–/– CIP2A–/– clones were established using CRISPR-Cas9 (Supplementary Fig. 1B). CIP2A loss prevented TOPBP1 localization at DNA selectively during mitosis, which verifies the lack of functional CIP2A expression, and allowed us to selectively study the role of the mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex (Supplementary Fig. 1B–D)31,32. Of note, mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 foci formation is not a specific feature of p53-defective cells, as CIP2A-TOPBP1 is also recruited to mitotic foci in RPE1 TP53-wt cells (Supplementary Fig. 1E, F). We observed elevated baseline levels of CIP2A-TOPBP1 foci in p53-defective cells, possibly caused by increased DNA damage or impaired cell cycle checkpoint function. In line with previous studies, CIP2A–/– cells showed elevated levels of micronuclei, already in untreated conditions31,32,33. Importantly, the amount of micronucleated CIP2A–/– cells strongly increased upon APH and IR treatment (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1G), showing that CIP2A prevents missegregation of chromosome fragments into micronuclei in response to various sources of mitotic DNA damage.

a RPE1 TP53–/– cells were treated with aphidicolin (APH, 200 nM, 20 h) or ionizing radiation (IR, 0.25 Gy). Representative wide-field images of cells stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (green) and γH2AX (red) are shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. b Quantification of co-localizing CIP2A and γH2AX foci per mitotic cell for cells described in panel a. Individual values and medians per condition are shown from one biological replicate. c RPE1 TP53-/- cells and CIP2A-/- clones were treated with APH (200 nM, 24 h) or IR (3 Gy). Bars represent means and standard error of the mean (SEM) of micronuclei per cell of at least three biologically independent experiments. Two-tailed unpaired t-test was used. RPE1 TP53–/– cells were treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h, panel d) or IR (0.25 Gy, panel e). Representative images of three classes of mitotic structures are shown. Left: confocal overview images; right: STED images of CIP2A-TOPBP1 complexes. Cells were stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (green) and TOPBP1 (red). Scale bar: 5 µm (confocal) or 500 nm (STED). f Quantification of CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures per cell per mitotic phase for data in panel (d). Bars represent means and SEM of three biologically independent experiments. g Quantification of CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures per cell per mitotic phase for data in panel (e). Bars represent means and SEM of three biologically independent experiments. ‘n’ in panels (b/c/f/g) represents total number of cells across experiments. h Quantification of indicated structures per mitotic phase for indicated treatments for data from panels d and e. Percentages compared to the total structures are indicated. Mean and SEM are shown per mitotic phase and per treatment. i Quantification of the size of indicated structures per mitotic phase for indicated treatments for data from panels d and e. Median values and SEM are plotted (line graph), along with raw data (individual dots) for both IR- and APH-treated cells. ‘n’ in panels (h/i) represents total number of observed structures per mitotic phase from three biologically independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We subsequently explored the role of the ATM and ATR DNA damage response (DDR) kinases in CIP2A recruitment. ATR activity was not required for APH-induced induction of mitotic CIP2A foci, nor was it required for CIP2A foci formation in untreated cells (Supplementary Fig. 1H). Rather, ATR inhibition elevated the number of CIP2A foci in untreated cells, suggesting that ATR inhibition leads to increased transmission of DNA lesions into mitosis (Supplementary Fig. 1H). ATM inhibition did not influence the number of CIP2A foci in either untreated or APH-treated cells. However, ATM inhibition reduced the number of IR-induced CIP2A foci (Supplementary Fig. 1H). These results show that CIP2A marks different types of lesions, with differential upstream DNA damage signaling requirements.

To obtain a more detailed view of mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures, we employed Stimulated Emission Depletion (STED) microscopy. This type of super-resolution imaging offers a spatial resolution of 30–50 nm, compared to confocal microscopy with a resolution of around 250 nm40,41. STED microscopy revealed three distinct classes of CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures: unstructured complexes, loop-containing structures and filamentous structures (Fig. 1d, e). These three classes of structures occurred both in response to APH or IR treatment, which all showed a high degree of CIP2A and TOPBP1 co-localization within these structures, indicating that these proteins are less than 30 nm apart, although areas with differences in spatial distribution were observed (Fig. 1d, e, Supplementary Fig. 2A). Quantification of the total number of CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures per mitotic phase showed a clear reduction during mitotic progression, in both APH- and IR-treated cells (Fig. 1f, g, Supplementary Fig. 2B). No obvious differences in prevalence of total number of CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures between APH or IR treatment was observed. Instead, the prevalence of the distinct classes of structures correlated with the mitotic stage (Fig. 1h). Whereas the majority of the CIP2A-TOPBP1 complexes in prophase and prometaphase showed an unstructured morphology (45–55%), in metaphase the loop-containing structures were more prevalent (51%) (Fig. 1h). While the filaments only constituted a constant minor fraction of the total amount of structures (15%), during anaphase their prevalence strongly increased (31%). In telophase, the remaining CIP2A-TOPBP1 complexes mostly showed an unstructured morphology (Fig. 1h). Examination of the structure size was done by measuring the length of the longest axis within a structure (as exemplified in Supplementary Fig. 2C). The median size of unstructured forms ranged from 505 to 656 nm in prophase to 453–472 nm in telophase (Fig. 1i), with IR-induced structures being slightly larger than APH-induced structures. The median size of loop-containing structures ranged from 827 to 903 nm, with no obvious difference between APH or IR-induced structures. Filamentous structures showed a median size range between 730 and 870 nm in prophase to 724–825 nm in telophase, with no obvious difference between IR and APH conditions (Fig. 1i). Of note, whereas the median size of loop-containing and filamentous structures was similar between APH- and IR-treated cells and between the different mitotic stages, the size range of these structures became larger in later mitotic stages (e.g., range of IR-induced filamentous structures in anaphase: 389–3388 nm). Examination of the elongation (the ratio between the longest and shortest axis) of the loop-containing structures (as exemplified in Supplementary Fig. 2C) showed that there were no significant changes in the elongation between different mitotic stages or treatment conditions (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Combined, these analyses illustrate the emergence of large CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures, that show similar morphologies despite being formed in response to different sources of DNA damage (Fig. 1i, Supplementary Fig. 2D).

To determine whether the observed CIP2A-TOPBP1 filamentous structures could represent ultra-fine bridges (UFBs) in anaphase, we assessed their co-localization with the DNA translocase PICH, an established marker of UFBs27,42. While the majority of CIP2A structures in anaphase were positive for PICH (Supplementary Fig. 2E–G), only a subset of PICH-positive UFBs showed CIP2A co-localization (Supplementary Fig. 2G, left panel). Of note, filamentous CIP2A structures occasionally overlapped with parts of PICH-decorated UFBs (Supplementary Fig. 2F), whereas the majority of filamentous CIP2A structures involved CIP2A localization at or in between PICH foci (Supplementary Fig. 2G). Combined, these data show that although CIP2A frequently co-localizes with PICH, CIP2A filaments do not per se reflect UFB structures.

Complex formation between CIP2A and SMX complex members upon perturbed replication

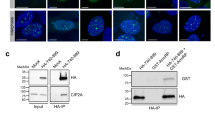

Although APH and IR treatment both resulted in micronuclei formation in CIP2A–/– cells and induced the formation of similar CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures, the underlying DNA lesions differ and likely require differential processing during mitosis. To explore if the CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex has differential interacting partners upon APH versus IR treatment, endogenous CIP2A was immunoprecipitated in parental RPE1 TP53-/- or CIP2A-/- cells and associated proteins were analyzed. Previously established (in)direct CIP2A interactors TOPBP131,32 and MDC132 were identified by western blot analysis, validating the approach (Supplentary Fig. 3A). Mass spectrometry analysis of CIP2A immunoprecipitations identified several additional associated proteins (Fig. 2a, b, Supplementary Fig. 3B, C). We identified the XPF endonuclease (also called ERCC4) to be present in our mass spectrometry analysis after both IR and APH treatment, and specifically enriched in APH treatment conditions (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 3B, C; Supplementary Data 1). In line with the mass spectrometry analysis, XPF co-localized with CIP2A at APH-induced foci (Fig. 2c). In line with XPF being enriched in APH-treated conditions in our proteomics analysis, in untreated and IR-treated conditions most CIP2A foci were XPF-negative, whereas a large fraction ( ~ 50%) of APH-induced CIP2A foci were XPF-positive (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 3D). However, all mitotic XPF foci were CIP2A-positive, regardless of the treatment setting (Supplementary Fig. 3E). Because the XPF nuclease operates in complex with its co-factor ERCC143, we also analyzed ERCC1 co-localization with CIP2A. Like XPF, also ERCC1 was found to co-localize with CIP2A, which was increased upon APH treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3F). These findings imply that complex formation of CIP2A-TOPBP1 with XPF depends on the type of DNA lesion. Importantly, CIP2A was required to recruit XPF to APH-induced DNA lesions, as XPF foci were absent in CIP2A–/– cells (Fig. 2d, e). Based on these findings, we further focused on APH-induced mitotic DNA lesions.

a, b Mass spectrometry analysis of mitotic CIP2A interactors in RPE1 TP53–/– parental versus CIP2A–/– cl#1 cells upon treatment with IR (panel a, 5 Gy) or with APH (panel b, 200 nM, 20 h). Proteins highlighted in red are enriched after IR or APH treatment. Proteins highlighted in black: known CIP2A interactors or SMX complex members that were not enriched after treatment. Two-sided Significance Analysis of Microarrays t-test was performed on three technical replicates. c Left panel: representative wide-field images of RPE1 TP53–/– cells stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (green) and XPF (red) in either untreated conditions, or upon treatment with APH (200 nM, 20 h) or IR (0,25 Gy). Right: quantification of the percentage of CIP2A foci of the total number CIP2A foci per mitotic cell that co-localize with XPF. Bar represents the median and 95% confidence interval of three biological independents experiments. Two-tailed unpaired t-test on the medians per experiment was used. d–k Imaging and quantification of mitotic XPF, SLX4, MUS81, ERCC1 foci for RPE1 TP53–/– and CIP2A–/– cl#1 cells either untreated or treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h). Panel d: Representative wide-field images of treated cells stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (green) and XPF (red). f Representative wide-field images of treated cells stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (red) and SLX4 (green). h Representative wide-field images of treated cells stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (red) and MUS81 (green). j Representative wide-field images of treated cells stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (red) and ERCC1 (green). Panels e/g/i/k: Quantification of mitotic foci of XPF (Panel e), SLX4 (panel g), MUS81 (panel i) or ERCC1 (panel k). Individual values, medians and interquartile range of three biologically independent experiments are plotted. Two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparisons test was used on median values per experiment. Throughout the figure, ‘n’ represents the total number of cells measured across experiments, and scalebars represent 10 µm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

During mitosis, the structure-specific XPF/ERCC1 nuclease is part of the SMX complex, which further consists of the SLX4 scaffold and the other structure-specific nuclease SLX1 and MUS81-EME144. The SMX complex has been described to resolve joint DNA molecules, including stalled replication forks and HR intermediates such as Holliday junctions, to enable proper chromosomes segregation in anaphase24,44,45,46,47. We hypothesized that CIP2A might be in complex with XPF/ERCC1 as part of the SMX complex. This notion was strengthened by the observation that other components of the SMX complex (SLX4, MUS81, EME1, ERCC1) were also identified in our mass spectrometry analysis of CIP2A immuno-precipitations (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 3B, C; Supplementary Data 1). Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis confirmed that other components of the SMX complex (i.e., SLX4, MUS81 and ERCC1) also co-localized with CIP2A (Fig. 2f–k). Importantly, like XPF/ERCC1, mitotic foci formation of SLX4 and MUS81 was significantly increased upon APH treatment, and largely absent in CIP2A-/- cells (Fig. 2f–k). Of note, loss of SLX4, MUS81, and XPF foci was not explained by lower expression levels of these proteins in CIP2A–/– cells (Supplementary Fig. 3G). In line with this notion, SLX4 foci formation during interphase was unaffected in CIP2A-/- cells (Supplementary Fig. 3H), demonstrating that CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex is required for recruitment of the SMX complex specifically during mitosis. To confirm that CIP2A facilitates recruitment of the SMX complex rather than its components individually, we tested co-localization of SMX complex members validated at sites of CIP2A foci. Indeed, virtually all XPF foci co-localized with SLX4 and with MUS81 at CIP2A foci (Supplementary Fig. 3i, j). In line with CIP2A being required for recruitment of the SMX members as a complex, SLX4, MUS81, or XPF depletion did not affect CIP2A foci formation (Supplementary Fig. 4A–F), whereas depletion of the SMX scaffold SLX4 prevented the recruitment of both MUS81 and XPF to CIP2A foci (Supplementary Fig. 4G–J). Conversely, depletion of MUS81 did not affect XPF recruitment (Supplementary Fig. 4I, J), nor did XPF depletion affect MUS81 recruitment (Supplementary Fig. 4K, L). Combined, these data show that CIP2A-TOPBP1 acts upstream of SLX4 recruitment, and SLX4 is subsequently required for the recruitment of other SMX complex members during mitosis.

CIP2A-TOPBP1 forms a mitotic scaffold for the SMX complex at sites of perturbed DNA replication

To investigate how the SMX complex is locally positioned at mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures, STED microscopy analysis of SLX4, ERCC1, and MUS81 was performed. SLX4, ERCC1, and MUS81 showed a punctate localization pattern onto CIP2A structures, with locally enriched recruitment (Fig. 3a–c). Of note, the SMX complex members SLX4, ERCC1 and MUS81 all located at CIP2A structures (ranging between 82 and 92% of all CIP2A structures), independently of CIP2A organization (ranging between 77 and 97% of unstructured forms, loop-containing or filamentous CIP2A structures) at APH-induced DNA lesions (Fig. 3d–f, Supplementary Fig. 5A). Line profile analysis showed that SMX complex members localize along the entire CIP2A structure, with some SMX complex members occasionally found at regions with lower CIP2A intensity (Supplementary Fig. 5B). Combined, these data suggest that the mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures form a scaffold that recruits and localizes the SMX complex to sites of DNA lesions.

RPE1 TP53–/– cells were treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h) and stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (green) and SLX4 (red, panel a), ERCC1 (red, panel b), MUS81 (red, panel c). Representative image of each of the indicated CIP2A structure organizations are shown. Scale bar: 5 µm (confocal) or 500 nm (STED). Left: confocal overview images. Right: STED images. Quantification of the percentage of mitotic CIP2A structures that co-localized with SLX4 (panel d), ERCC1 (panel e) or MUS81 (panel f) for each of the indicated CIP2A structure organizations for data from panels a-c. Bars represent means and SEM. g RPE1 TP53–/– cells were treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h) and stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (green) and γH2AX (red). Scale bar:5 µm (confocal) or 500 nm (STED). Left: confocal overview images. Right: STED images. h RPE1 TP53–/– cells were treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h), pulsed with EdU during mitotic entry and stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (green) and EdU (red). Scale bar: 5 µm (confocal) or 500 nm (STED). Left: confocal overview images. Right: STED images. i Quantification of mitotic CIP2A structures that are positive for γH2AX for data from panel g. Bars represent means and SEM. j Quantification of mitotic CIP2A structures that are either negative (0 foci) or positive for 1, 2 or more than 2 EdU foci for data from panel h. Pie chart represents the means. Throughout figure, ‘n’ represents the total number of structures measured across three biological independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next analyzed whether CIP2A structures formed at sites of ongoing DNA replication at mitotic entry. To this end, cells were pulsed with the synthetic nucleotide analog EdU during mitotic entry, and incorporated EdU was visualized along with γH2AX and/or CIP2A. For unstructured CIP2A, CIP2A co-localized with γH2AX, with γH2AX appearing as a cloud surrounding CIP2A structures (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 5C). Conversely, filamentous CIP2A structures were mostly adjacent to γH2AX clouds and loop-containing CIP2A structures predominantly showed γH2AX staining enclosed inside the CIP2A loops (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 5C). CIP2A structures were mostly observed in close proximity to EdU foci, with EdU localizing to those parts of the CIP2A structures that showed lower CIP2A intensity (Fig. 3h, Supplementary Fig. 5D). The large majority of CIP2A structures were positive for both γH2AX and EdU (Fig. 3i, j). To further define the spatial relationship between EdU, γH2AX and CIP2A localization, simultaneous imaging of γH2AX (by confocal microscopy) and EdU/CIP2A (at STED resolution) was performed (Supplementary Fig. 6A). We observed that EdU foci were frequently located in regions with reduced γH2AX signal, in line with EdU marking sites of replication, along with histone eviction at replication forks. Additionally, these data show that in case CIP2A forms extended structures away from γH2AX (e.g., a filamentous structure), EdU localizes along the CIP2A structure, not necessarily close to γH2AX (Supplementary Fig. 6A). Again, in these extended structures EdU appears adjacent to CIP2A rather than co-localized. Also, γH2AX was only sparsely present at filamentous CIP2A structures, suggesting local chromatin remodeling. Consistent with our findings that both IR and APH induced similar classes of CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures, CIP2A structures were also observed that were devoid of EdU (Supplementary Fig. 6B).

Of note, filamentous CIP2A structures occasionally bridged two EdU foci (Fig. 3h). For approximately half of APH-induced CIP2A structures (48.2%), we identified one EdU focus in close proximity, whereas a smaller percentage (24.0%) of CIP2A structures assembled in the vicinity of two EdU foci (Fig. 3j). Together, these data reveal intricate structures of a CIP2A-containing macromolecular scaffold that facilitates the recruitment of the SMX complex, and forms at sites of DNA damage in the vicinity of mitotic DNA synthesis.

CIP2A is not required for mitotic DNA synthesis

Previous studies showed mitotic DNA synthesis at sites of under-replicated DNA in a process called MiDAS21. As CIP2A localizes to sites of EdU incorporation, we investigated if CIP2A was required for MiDAS. Analysis of mitotic EdU foci in parental RPE1 TP53–/– cells, CIP2A–/– cells, and CIP2A–/– cells reconstituted with full length V5-tagged CIP2A (Supplementary Fig. 7A) showed that CIP2A is not required for MiDAS in RPE1 TP53–/– cells (Fig. 4a, b). To corroborate these finds, we observed that RAD52, a previously reported key factor in MiDAS18,20, still formed mitotic foci in RPE1 TP53–/– CIP2A–/– cells, indicating that loss of CIP2A does not impair RAD52 recruitment (Supplementary Fig. 7B). Previously, short-term depletion of MUS81, SLX4 or EME1 in U2OS cells was reported to impair MiDAS21, however studies in RPE1 TP53–/– cells showed that MUS81 was not required for MiDAS induced by APH28. In line with our finding that CIP2A is not essential for MiDAS, we confirmed that depletion of MUS81 did not affect APH-induced MiDAS in RPE1 TP53–/– cells (Supplementary Fig. 7C). To extend these findings to other cell line models, CIP2A was depleted in a panel of triple-negative breast (TNBC) cell lines. Specifically, CIP2A was edited using CRISPR/Cas9- in MDA-MB-231 and HCC38 cells (Fig. 4c–e, Supplementary Fig. 7D, E), or depleted by shRNA in BT549 cells (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 7F). CIP2A inactivation prevented mitotic SLX4 foci formation (Fig. 4c, d). In contrast, in all cell lines tested, CIP2A inactivation did not prevent EdU foci formation in response to APH treatment (Fig. 4d, e). Combined, these data show that CIP2A is not essential for MiDAS.

a RPE1 TP53–/–, CIP2A–/– cl#1 cells and CIP2A–/– cl#1 cells reconstituted with full-length CIP2A-V5 were treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h), pulsed with EdU during mitotic entry. Representative wide-field images of cells stained for DAPI (blue) and EdU (red). Scare bar:10 µm. b Quantification of EdU foci per mitotic cell for data from panel (a). Individual values, medians, and interquartile range of three biologically independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparisons test was used on median values per experiment. c Wildtype or CIP2A-/- MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h) and pulsed with EdU during mitotic entry. Representative wide-field images of MDA-MB231 cells stained for DAPI, CIP2A, SLX4, EdU are shown. Scale bar: 10 µm. d Quantification of EdU and SLX4 foci per mitotic cell for data from panel c. Individual values, medians, and interquartile range of three biologically independent experiments are plotted. Two-tailed unpaired t-test was used on the medians per experiment. e Wildtype or CIP2A-/- HCC38 cells were treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h), and pulsed with EdU during mitotic entry. Quantification of EdU foci per mitotic cell in HCC38 is shown. Individual values, medians, and interquartile range of three biologically independent experiments are plotted. Two-tailed unpaired t-test was used on the medians per experiment. f BT549 cells with doxycycline-indicated inducible shRNAs were treated as in panel E. Quantification of EdU foci per mitotic cell is shown. Individual values, medians and interquartile range of three biologically independent experiments are plotted. Two-tailed unpared t-test was used on the medians per experiment. Throughout the figure, ‘n’ represents the total number of cells measured across experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The C-terminal domain of CIP2A is required for the formation of mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures and SMX complex recruitment

The CIP2A protein structure analysis showed three distinct domains: an N-terminal globular domain (aa 1-617), an alpha-helical coiled-coil domain (aa 618-876), and a conserved C-terminal unstructured domain (aa 877-905). AlphaFold predicted CIP2A to form a stable homodimer, with a coiled-coil shaft with an uncertain—and possibly flexible - position of the N-terminal globular domain onto the coiled-coil shaft (Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. 8A, B). AlphaFold predictions further suggested that a CIP2A homodimer binds to two TOPBP1 proteins (Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. 8A). Consistent with previous interaction mapping studies31,32, this CIP2A-TOPBP1 interaction involves residues 755-860 of TOPBP1, which likely interact with both the globular domain and coiled-coil of CIP2A (Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. 8B).

a CIP2A is predicted to form a stable homodimer, involving a globular domain and a long coiled-coil. Two predicted TOPBP1-binding sites and the possibly flexible position of the N-terminal regions onto the coiled-coil shaft are indicated. b Cartoon and surface representation of the predicted CIP2A:CIP2A dimer structure with two copies of TOPBP1 755-860. Predicted TOPBP1:CIP2A binding interfaces are magnified. c Schematic representation of full length (1-905) CIP2A (WT) and schematic representation of V5-tagged CIP2A variants. Quantification of V5 foci and TOPBP1 foci per mitotic cell (d) or micronuclei per cell (e) in RPE1 TP53–/– CIP2A–/– cl#1 cells reconstituted with indicated CIP2A-V5 variants treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h). Individual values, medians, and interquartile range of three (d) or at least three (e) biologically independent experiments are plotted. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparisons test (d) or Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (e) on medians per experiment. f–l CIP2A–/– cells reconstituted with CIP2A-WT, CIP2A-S904A or CIP2A-ΔC were treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h). Panel f: representative wide-field images of cells stained for DAPI (blue), V5 (red), SLX4 (green). Scale bar:10 µm. Quantification of foci of SLX4 (g), MUS81 (h) or XPF (i) per mitotic cell in CIP2A–/– cl#1 reconstituted with indicated mutants. Individual values, medians and interquartile range of three biologically independent experiments are plotted. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparisons test on the medians per experiment. ‘n’ in panels (d, e, g–i) represents the total number of cells across experiments. Left: confocal overview images. Right: representative STED microscopy images of DAPI (blue), V5 (green) and TOPBP1 (red) structures in CIP2A–/– cells reconstituted with CIP2A-WT (j) or CIP2A-ΔC (k) for indicated structure classes after APH treatment (200 nM, 20 h). Scale bar: 5 µm (confocal) or 500 nm (STED). l Quantification of indicated structures for data from panel (j and k). Bars represent means and SEM, and ‘n’ represents the total number of observed structures, of three biologically independent experiments. Two-tailed unpaired t test was used. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To investigate which domains of CIP2A are required for complex formation of CIP2A-TOPBP1 and for SMX complex recruitment, a panel of CIP2A deletion mutants was analyzed. CIP2A–/– cells were reconstituted with either full length CIP2A (WT: CIP2A 1-905-V5), a deletion mutant lacking the C-terminal unstructured region (ΔC: CIP2A 1-876-V5), a mutant only having the globular domain (Glob: CIP2A 1-617-V5), a mutant lacking the coiled-coil domain (ΔCC: CIP2A Δ623-871-V5), and a mutant lacking the globular domain (ΔGlob: CIP2A 618-905-V5) (Fig. 5c). Additionally, we included the CIP2A L533E mutant that was previously reported to interfere with CIP2A dimerization48, and a S904A mutant to disrupt a previously reported putative PLK1 phosphorylation site (Supplementary Fig. 8C)49. Full length CIP2A and the S904A, L533E and ΔC CIP2A mutants showed clear expression, while Glob and ΔCC mutants were expressed at lower levels compared to full length CIP2A (Supplementary Fig. 7A). CIP2A ΔGlob was not effectively expressed, and was therefore excluded from further experiments (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis demonstrated that CIP2A-WT, CIP2A-S904A, and CIP2A-L533E formed clear mitotic foci, which co-localized with TOPBP1. No CIP2A-TOPBP1 foci were observed in cell lines expressing the CIP2A Glob and ΔCC mutants (Fig. 5d). This could be either caused by lower expression levels of these mutants or could indicate that the coiled-coil is required for CIP2A-TOPBP1 foci formation. The latter would be in line with our AlphaFold predictions that TOPBP1 interacts with both the globular and coiled-coil domain of CIP2A. Strikingly, cells expressing CIP2A-ΔC only formed very faint CIP2A-TOPBP1 foci, when compared to cells expressing CIP2A-WT (Supplementary Fig. 9A, B).

To explore the functional consequences of these CIP2A mutants, micronuclei formation after APH treatment was investigated. CIP2A deletion increased micronuclei formation in RPE1 cells, which was rescued upon expression of CIP2A-WT, S904A and L533E, whereas expression of CIP2A-ΔC, or the mutants that failed to support CIP2A-TOPBP1 foci formation, did not rescue this phenotype (Fig. 5e). We next tested whether the reduced CIP2A-TOPBP1 foci formation of CIP2A-ΔC expressing cells coincided with defective SLX4, MUS81 and XPF recruitment. In these analyses, CIP2A-S904A was included as S904 resides in the 29 aa C-terminal region that is lacking in CIP2A-ΔC. Whereas SLX4, MUS81 and XPF foci formation was only modestly and non-significantly decreased in cells expressing CIP2A-S904A, foci formation was strongly reduced in cells expressing CIP2A-ΔC (Fig. 5f–i, Supplementary Fig. 9C, D). Combined, these observations show that the unstructured C-terminal tail of CIP2A is required for the formation of higher order CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures, for SMX complex recruitment and to suppress micronuclei formation.

STED microscopy was subsequently used to analyze the role of the C-terminal tail of CIP2A in mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 structure formation. Expression of CIP2A-ΔC in CIP2A-/- cells resulted in the formation of low intensity CIP2A structures that co-localized with TOPBP1 (Fig. 5j, k, Supplementary Fig. 9A, B). However, formation of loop-containing and filamentous CIP2A-ΔC structures was rare, and the loop-containing and filamentous structures that did form in CIP2A-ΔC expressing cells appeared less ordered than CIP2A-WT structures (Fig. 5j–l). Taken together, these data indicate that the C-terminal tail of CIP2A is required for correct organization of mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures and subsequent SMX complex recruitment.

Mitotic CIP2A-SLX4 foci formation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutant cells

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutant cells were shown to have increased CIP2A foci in mitosis and loss of BRCA1/2 is synthetic lethal with CIP2A inactivation31. This prompted us to investigate mitotic CIP2A foci in isogenic RPE1 and DLD1 cell line panels with WT or mutant BRCA1/2. We observed elevated levels of CIP2A foci in BRCA1–/– (Fig. 6a, b) and BRCA2–/– cells (Fig. 6c, d). Importantly, approximately 65% of CIP2A foci in BRCA2–/– cells was positive for SLX4 (Fig. 6d), whereas only approximately 30% of the CIP2A foci in BRCA1–/– cells was positive for SLX4 (Fig. 6b). To exclude a role for BRCA1 in SLX4 recruitment to mitotic CIP2A foci, we analyzed SLX4 recruitment to CIP2A foci. APH treatment of BRCA1–/– cells resulted in a significant increase in mitotic SLX4 foci (Supplementary Fig. 10A). We also observed that in BRCA1–/– cells, although not all CIP2A foci are SLX4 positive, all SLX4 foci are recruited to CIP2A sites (Supplementary Fig. 10B)

Imaging and quantification of RPE1 RPE1 TP53–/– PAC–/– cells and RPE1 TP53–/– PAC–/– BRCA1–/– cells (a, b) or DLD1 WT cells and DLD1 BRCA2–/– cells (c, d) left untreated or treated with APH (200 nM, 20 h). Panel a, c: Representative wide-field images of cells stained for DAPI (blue), CIP2A (red), SLX4 (green). Panel b, d: Quantification of CIP2A and SLX4 foci per mitotic cell. Individual values, medians and interquartile range of three biologically independent experiments are plotted. Two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparisons test was used on the medians per experiment. Quantification of percentages of CIP2A foci of total number CIP2A foci co-localizing with SLX4. Median values per experiment are plotted. Bars represent the mean and SD of three biologically independent experiments. e Representative images of clonogenic survival assays of doxycycline-treated parental RPE1 TP53–/– and CIP2A–/– cl#1 and CIP2A–/– cl#1 cells, reconstituted with CIP2A-WT or CIP2A-ΔC with doxycycline-inducible luciferase (shLUC) or BRCA2 (shBRCA2) shRNA. f Quantification of colony survival for data from panel (e), normalized to doxycycline-treated shLUC-expressing cell lines. Bars represent mean survival and SD of three biologically independent experiments. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used. Quantification of micronuclei and nucleoplasmic bridges per cell for RPE1 TP53–/– PAC–/– cells and RPE1 TP53–/– PAC–/– BRCA1–/– cells (g) or DLD1 WT and DLD1 BRCA2–/– cells (h), transfected with indicated siRNAs. Bars represent the mean with SEM of eight biologically independent experiments (g) or six biologically independent experiments (h). Two-tailed unpaired t-test was used. i, j Representative wide-field images of DLD1 BRCA2–/– cells transfected with indicated siRNAs and stained for DAPI. Arrows indicate either micronuclei (i), or nucleoplasmic bridges (j). Throughout the figure, ‘n’ represents the total number of cells measured per condition and scale bars represent 10 µm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

BARD1 was previously described to be required for the stability and function of BRCA150,51. In line with this function, BARD1 degradation in HCT116 BARD1AID/AID cells resulted in BRCA1 depletion (Supplementary Fig. 10C), and caused elevated levels of mitotic CIP2A and SLX4 foci (Supplementary Fig. 10D). Importantly, SLX4 recruitment was lost in CIP2A-/- cells (Supplementary Fig. 10D, E). Of note, we observed that the percentage of mitotic CIP2A foci that were positive for SLX4 in BARD1-depleted cells was approximately 40%, which was lower than observed upon APH treatment (Supplementary Fig. 10F), similar to observations in BRCA1–/– cells (Fig. 6d). Taken together, these data indicate that a substantial fraction of mitotic CIP2A foci recruit SLX4 in BRCA1–/–, BRCA2–/– and BARD1AID/AID cells, and suggest that mitotic SMX complex recruitment is involved in DNA lesion processing and survival in these cells.

As BRCA2–/– cells showed an increased number of mitotic CIP2A foci, which were positive for SLX4, we investigated if expression of CIP2A-ΔC, which precluded SMX complex recruitment, is synthetic lethal with BRCA2 loss. To this end, we depleted BRCA2 using doxycycline-inducible shRNAs in parental RPE1 TP53–/– cells, CIP2A–/– cells, or CIP2A–/– cells reconstituted with CIP2A-WT or CIP2A-ΔC (Supplementary Fig. 10G). In line with a previous report31, inactivation of CIP2A resulted in a strong inhibition of clonogenic outgrowth of BRCA2-depleted RPE1 TP53–/– cells (Fig. 6e, f). Importantly, viability of BRCA2 depleted cells was rescued by expression of full-length CIP2A, but not by expression of CIP2A-ΔC (Fig. 6e, f). Clearly, full length CIP2A, which is able to form higher order CIP2A-TOPBP1 complexes and facilitate SMX complex recruitment, is required to resolve the mitotic DNA lesions in BRCA2 mutant cells.

SLX4 loss phenocopies CIP2A loss in BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient cells

Next, we aimed to investigate whether mitotic recruitment of the SMX complex, like CIP2A, is required for genome stability of BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient cells. To assess this, we depleted either SLX4 or CIP2A in BRCA1- or BRCA2 proficient and deficient cells (Supplementary Fig. 10H, I) and quantified micronuclei formation as a marker of mitotic defects. A significant and similar increase in micronuclei formation was observed in BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient cells upon depletion of either SLX4 or CIP2A (Fig. 6g–i, Supplementary Fig. 10J), whereas no significant changes were observed in BRCA1- or BRCA2-proficient cells (Fig. 6g, h). These findings indicate that SLX4 prevents mitotic errors in BRCA1- or BRCA2-deficient cells, to a similar extent as CIP2A.

We further hypothesized that depletion of SLX4 or CIP2A in BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient cells disrupts the processing of under-replicated DNA lesions, resulting in persistent DNA connections following the completion of mitosis. To test this, we quantified the number of nucleoplasmic bridges in BRCA1- or BRCA2-proficient and BRCA1- or BRCA2-deficient cells upon SLX4 or CIP2A depletion. Consistent with a role for CIP2A and SLX4 in processing joint molecules that result from perturbed replication, we observed a significant increase in nucleoplasmic bridges upon loss of SLX4 or CIP2A in BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient cells (Fig. 6g, h, j, Supplementary Fig. 10K), but not in BRCA1- and BRCA2-proficient cells (Fig. 6g, h). Combined, our results show that SLX4, of which mitotic recruitment requires CIP2A-TOPBP1, is crucial for preventing excessive genome deterioration in BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient cells.

Discussion

In this study, we describe the formation of CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures in response to DNA damage during mitosis. Importantly, we find that the CIP2A-TOPBP1 scaffold facilitates the recruitment of the SMX complex to sites of under-replicated DNA. Formation of mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures requires a highly conserved short C-terminal domain of CIP2A, which is also required for SMX recruitment and viability of BRCA2 mutant cancer cells. Combined, these results demonstrate that the CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex functions beyond DNA damage tethering and is required for mitotic DNA lesion processing.

We observed that both perturbed DNA replication and irradiation lead to CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures with similar morphology. However, the upstream signaling required for CIP2A-TOPBP1 foci formation was different. ATM activity is required for the formation of IR-induced CIP2A-TOPBP1 mitotic structures, but not for formation of APH-induced CIP2A-TOPBP1 mitotic structures. This requirement aligns with a role for MDC1 in TOPBP1 recruitment upon mitotic DSB generation31,32,39. Moreover, these data show that replication-mediated DNA lesions likely recruit CIP2A-TOPBP1 in a MDC1-independent fashion.

We also find a differential composition of CIP2A-TOPBP1 complexes upon IR compared to APH treatment. Our proteomic analysis uncovered that the SMX complex is a mitotic interactor of the CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex. In line with our proteomic results, APH-treated cells showed SMX complex localization to the majority of mitotic CIP2A structures, whereas the majority of IR-induced mitotic CIP2A foci remained SMX complex-negative. This suggests that not all mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures are formed equally and that ancillary factors or post-translational modifications, instructed by the nature of the DNA lesion, will determine the composition of these mitotic DNA response complexes.

SMX complex members were previously shown to resolve joint DNA molecules in a cell cycle-dependent fashion. Specifically, Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) and Polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) promote the activity of MUS81-EME152,53,54,55,56,57 and promote assembly of the SMX complex58. In addition, studies in yeast showed that the SLX4 scaffold of the SMX complex associates with the TOPBP1 orthologue Dpb11, promoted by CDK1-mediated phosphorylation of Thr126059. Our data show that CIP2A is essential for the recruitment of SLX4 and associated SMX complex components during mitosis. The observed complete loss of mitotic TOPBP1 recruitment upon disruption of CIP2A likely prevents SLX4 and SMX complex recruitment in CIP2A–/– cells. Similarly, a CIP2A mutant lacking the C-terminal 29 amino acids (CIP2A-ΔC) supports initial recruitment of TOPBP1, but does not form higher-order CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures and is defective for SLX4, MUS81 and XPF recruitment. Although the exact function of the unstructured C-terminus of CIP2A remains elusive, based on our data one could hypothesize that the C-terminus facilitates filament formation between CIP2A homodimers. Mutation of the PLK1 phosphorylation site S904 only partially phenocopied the CIP2A-ΔC mutant, suggesting that other functional domains reside in the C-terminus. Previously reported structural studies involved a truncated CIP2A construct (1-560) due to instability of the full-length protein48, which precluded analysis and positioning of the C-terminal domain. However, this truncation may have compromised the CIP2A-TOPBP1 interaction. Cryo-EM analysis of full-length CIP2A in combination with TOPBP1 is warranted to uncover insights into the formation and architecture of this complex.

Based on the different CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures we observed at the various stages of mitosis, it is tempting to speculate that the loop-containing CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures reflect repair intermediates, involving chromatin alterations to allow processing of the DNA lesions. In line with this notion, the observed co-localization of CIP2A and γH2AX at unstructured CIP2A complexes, which occur most in early mitosis, was lost at loop-containing and filamentous structures, which occur in later mitotic stages, suggesting ongoing processing of DNA lesions, involving local chromatin remodeling (Fig. 7).

Filamentous CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures, which were predominantly observed in later stages of mitosis, co-localized with the UFB component PICH in anaphase, in agreement with a previous report demonstrating localization of TOPBP1 to UFBs in DT40 cells60,61. However, CIP2A only co-localized with a subset of UFBs, and the filamentous CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures are thus distinct from UFBs.

The observation that the number of CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures gradually decreases during the course of mitotic progression already suggested that DNA lesions are actively processed during mitosis, rather than DNA ends being tethered for repair after mitosis. One form of mitotic DNA lesion processing is MiDAS, which we show does not require CIP2A. This observation contributes to an ongoing debate regarding the molecular requirements for MiDAS. In RPE1 TP53–/– cells, our data align with a previously reported study that MUS81 is not required for MiDAS induced by APH28. Conversely, our previous work demonstrated that MUS81 is required for MiDAS induced by Cyclin E1 overexpression in RPE1 TP53–/– cells18. Similarly, short-term depletion of MUS81, SLX4 or EME1 in U2OS cells was reported to impair MiDAS21. These contradictory results about the role of the SMX complex in MiDAS18,21,46 suggest that MiDAS has context-dependent requirements. Potentially, complex DNA lesions such as those involving oncogene-induced R-loops, may require additional processing when compared to under-replicated DNA induced by APH in this study. Our finding that CIP2A is not required for MiDAS in RPE1 TP53–/– cells also aligns with reported synthetic lethal interactions31. A strong synthetic lethal interaction was observed between CIP2A and BRCA1/2 in RPE1 TP53-/- cells. However, RAD52, which is essential for MiDAS in RPE1 TP53–/– cells, does not show profound synthetic lethality with BRCA1/2 in these cells31. Combined, these findings argue against a major role for MiDAS underlying the synthetic lethality between CIP2A and BRCA1/2.

The mechanism by which SMX complex-mediated DNA breaks at under-replicated DNA are repaired during mitosis remains largely unclear. However, recent studies have demonstrated a role for CIP2A-TOPBP1 in the regulation of microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) during mitosis via RHINO and POLQ62,63. Combined with our finding that the CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex recruits the SMX complex, a model emerges in which SMX complex-mediated breaks in under-replicated regions are repaired by POLQ-mediated microhomology-mediated end-joining (Fig. 7)64. Of note, SMX complex components only co-localized with a subset of CIP2A foci in BRCA1, BRCA2 or BARD1 inactivated cells, suggesting that these cells also accumulate mitotic DNA damage which is distinct from underreplicated DNA. Hence, the synthetic lethal effects of CIP2A loss in these cells is explained by a defect in repair of multiple types of mitotic DNA damage.

Methods

Cell culture

All cell lines were grown in a humified incubator at 37 degrees Celsius in 5% CO2 and 20% O2. Human hTERT immortalized retinal pigmented epithelial RPE1 cells (CRL-4000) and human embryonic kidney HEK293T cells (CRL-3216) were obtained via the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). DLD1 wildtype and DLD1 BRCA2–/– human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells were obtained from Horizon (Cambridge, UK). RPE1 TP53-/- PAC-/- cells and RPE1 TP53–/– PAC–/– BRCA1–/– cells were previously described65. HCT116 BARD1AID/AID were described previously51. HEK293T, MDA-MB231 and RPE1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Thermofisher) complemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% penicillin and 1% streptomycin (Gibco). HCC38, BT549, and DLD1 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI, Thermofisher), complemented with 10% (v/v) FCS, 1% penicillin and 1% streptomycin (Gibco). HCT116 BARD1AID/AID cells were cultured in DMEM (Thermofisher) complemented with 10% (v/v) FCS, 1% penicillin, 1% streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco).RPE1 TP53-/- PAC-/- cells and RPE1 TP53-/- PAC-/- BRCA1-/- cells that were transfected with siRNAs were grown in a humified incubator at 37 degrees Celsius, 5% CO2 and 3% O2.

Mutagenesis

RPE1 cells harboring a TP53 mutation in exon 4 were described previously18,66. To generate the CIP2A knockout cell lines, a sgRNA (5’-ATCGGTTTGCTGTCTCAACT-3’) targeting exon 3 was cloned into pSpCas9(BB)−2A-GFP (px458), kindly provided by Feng Zhang (Addgene #48138)67. All oligonucleotides were purchased from Eurogentec. Upon transient transfection using Fugene HD transfection, GFP-positive cells were sorted with a Sony SH800S cell sorter at 48 h after transfection. Lack of CIP2A expression in RPE1 TP53-/- clones (CIP2A-/- cl#1 and cl#2), HCT116 BARD1AID/AID clones (CIP2A-/- cl#1 and cl#2), MDA-MB321 and HCC38 clones was confirmed by Western blot and immunofluorescence. CIP2A mutations in the two RPE1 TP53-/- clones were also confirmed with Sanger sequencing (cl#1: −1 deletion and +1 insertion, cl#2: +1 insertion).

Cloning

Full length CIP2A was cloned from pcDNA3.1/CIP2A(1-905) WT V5 His (Addgene #119287), which was a gift from Jukka Westermarck48, into retroviral pMSCV-blast which was a gift from David Mu (Addgene #75085)68, and subsequently different CIP2A mutations were generated in this pMSCV plasmid. For CIP2A ΔCC (Δ623-871-V5), amino acids from both sides of the coiled coil were kept as spacer between the globular domain and C-terminal unstructured domain to allow for flexibility. To establish cell lines expressing doxycycline inducible short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against scrambled (5’-CAACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAA-3’), luciferase (5’-AGAGCTGTTTCTGAGGAGCC-3’), BRCA2 (5’-AACAACAATTACGAACCAAACTT-3’), and CIP2A (5’-GCTAGTAGACAGAGAACATAA-3’), DNA oligos were cloned as previously described into Tet-pLKO-puro vector (Addgene #21915)69. This Tet-pLKO-puro vector was a gift from Dmitri Wiederschain70.

Short interfering RNA interference

Cells were seeded 24 h before transfection with short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for the negative control (SR-CL-000-005, Eurogentec), siMUS81 (#1: CAGCCCUGGUGGAUCGAUA and #2: CAUUAAGUGUGGGCGUCUA), siXPF (Silencer® Select, s4801 #4392420, ThermoFisher), siCIP2A (GACAACUGUCAAGUGUACCACUCUU) and siSLX4 (AAACGUGAAUGAAGCAGAA). Cells were once or twice transfected with siRNAs using OligofectamineTM transfection reagent (Thermofisher) or Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) as previously described18,65. Cells were either harvested for Western blot or fixed for immunofluorescence 48 h after siRNA transfection.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were seeded on glass coverslips in 6-well or 12-well plates at 48 h prior to indicted treatments. Cells were fixed for 15 min using 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS. After fixation, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X in PBS for 10 min. For MiDAS, EdU Click-IT reaction was performed for 30 min at room temperature according to protocol Click-ITTM EdU Cell Proliferation Kit for Imaging (Invitrogen). HCT116 BARD1AID/AID were seeded in presence of doxycycline (2 µg/mL) and when indicated treated after 24 h with indole-3-acetic acid (auxin, IAA, 1 mM, 72 h, Sigma). Further details are provided in Supplementary Methods. Detailed methodology for Airyscan microscopy is provided in the Supplementary Methods.

STED microscopy

Detailed methodology is provided in the Supplementary Methods section. STED microscopy slide preparation was performed largely as previously described for fixed HEK293T cells71. STED imaging of fixed samples was performed on a STED microscope (Abberior Expert Line) with a 100× oil immersion objective (Olympus Objective UPlanSApo 100×/1.40 oil). During imaging, z-stacks of cells were made at confocal resolution and all CIP2A foci in each cell were subsequently selected manually and individually imaged at STED resolution using a custom Python script adapted from Mol and Vlijm72. Whereas other microscopy techniques often require reference measurements and corrections to determine the relative localization between different color channels, the use of a single STED depletion donut for both excitation colors counteracts potential wavelength dependent optical effects, resulting in almost perfect coalignment of both excitation channels73. The numbers of CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures per telophase in Fig. 1f and 1G may be an overestimation of the actual number, as only cells with CIP2A-TOPBP1 structures were measured.

Mass spectrometry

For on-bead digestion of immunoprecipitated proteins, bead mixtures were subjected to cysteine reduction followed by alkylation, and trypsin (Promega) digestion. Details are provided in the Supplementary Methods section. The mass spectrometry proteomics data generated in this study have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository under the accession code PXD059881 [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD059881].

In silico protein prediction

To predict the structure of CIP2A and TOPBP1, we used Alphafold Multimer (AF2 multimer v3)74,75 run on ColabFold76 with standard settings (pair mode: unpaired, paired, 5 models with 3 or 10 recycles). Models were ranked according to their predicted template modeling (pTM) scores and top-ranked models were analyzed and visualized in ChimeraX77. pAE plots were generated with ChimeraX77, and were annotated using Adobe Illustrator.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data generated in this study have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository under the accession code PXD059881. All raw STED data generated in this study have been deposited on DataverseNL (https://doi.org/10.34894/O3KAFO). The AlphaFold models generated in this study are available in ModelArchive with the accession number ma-qrg0q [https://www.modelarchive.org/doi/10.5452/ma-qrg0q]. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The interactive Wiener Filter used for deconvolution of STED images using Jupyter Notebook can be found at GitHub (https://github.com/Vlijm-Lab/Wiener_filter) and Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/15075206)78.

References

Benkovic, S. J., Valentine, A. M. & Salinas, F. Replisome-mediated DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem 70, 181–208 (2001).

Glover, T. W., Wilson, T. E. & Arlt, M. F. Fragile sites in cancer: More than meets the eye. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 489–501 (2017).

Zeman, M. K. & Cimprich, K. A. Causes and consequences of replication stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 2–9 (2014).

De, S. & Michor, F. DNA secondary structures and epigenetic determinants of cancer genome evolution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 950–955 (2011).

Hodskinson, M. R. et al. Alcohol-derived DNA crosslinks are repaired by two distinct mechanisms. Nature 579, 603–608 (2020).

Halazonetis, T. D., Gorgoulis, V. G. & Bartek, J. An oncogene-induced DNA damage model for cancer development. Science 319, 1352–1355 (2008).

Schoonen, P. M., Guerrero Llobet, S. & van Vugt, M. A. T. M. Replication stress: Driver and therapeutic target in genomically instable cancers. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 115, 157–201 (2019).

Macheret, M. & Halazonetis, T. D. Intragenic origins due to short G1 phases underlie oncogene-induced DNA replication stress. Nature 555, 112–116 (2018).

Jones, R. M. et al. Increased replication initiation and conflicts with transcription underlie Cyclin E-induced replication stress. Oncogene 32, 3744–3753 (2013).

Bester, A. C. et al. Nucleotide deficiency promotes genomic instability in early stages of cancer development. Cell 145, 435–446 (2011).

Schlacher, K. et al. Double-strand break repair-independent role for BRCA2 in blocking stalled replication fork degradation by MRE11. Cell 145, 529–542 (2011).

Schoonen, P. M. et al. Progression through mitosis promotes PARP inhibitor-induced cytotoxicity in homologous recombination-deficient cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 8, 15981 (2017).

Chaudhuri, A. R. et al. Replication fork stability confers chemoresistance in BRCA-deficient cells. Nature 535, 382–387 (2016).

Heijink, A. M. et al. BRCA2 deficiency instigates cGAS-mediated inflammatory signaling and confers sensitivity to tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat. Commun. 10, 100 (2019).

Ge, X. Q., Jackson, D. A. & Blow, J. J. Dormant origins licensed by excess Mcm2-7 are required for human cells to survive replicative stress. Genes Dev. 21, 3331–3341 (2007).

Prakash, S., Johnson, R. E. & Prakash, L. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: Specificity of structure and function. Annu Rev. Biochem. 74, 317–353 (2005).

Sørensen, C. S. & Syljuåsen, R. G. Safeguarding genome integrity: The checkpoint kinases ATR, CHK1 and WEE1 restrain CDK activity during normal DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 477–486 (2012).

Audrey, A. et al. RAD52-dependent mitotic DNA synthesis is required for genome stability in Cyclin E1-overexpressing cells. Cell Rep. 43, 114116 (2024).

Laulier, C., Cheng, A. & Stark, J. M. The relative efficiency of homology-directed repair has distinct effects on proper anaphase chromosome separation. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 5935–5944 (2011).

Bhowmick, R., Minocherhomji, S. & Hickson, I. D. RAD52 Facilitates Mitotic DNA Synthesis Following Replication Stress. Mol. Cell 64, 1117–1126 (2016).

Minocherhomji, S. et al. Replication stress activates DNA repair synthesis in mitosis. Nature 528, 286–290 (2015).

Wyatt, H. D. M., Sarbajna, S., Matos, J. & West, S. C. Coordinated actions of SLX1-SLX4 and MUS81-EME1 for holliday junction resolution in human cells. Mol. Cell 52, 234–247 (2013).

Chan, Y. W. & West, S. C. Spatial control of the GEN1 Holliday junction resolvase ensures genome stability. Nat. Commun. 5, 4844 (2014).

Naim, V., Wilhelm, T., Debatisse, M. & Rosselli, F. ERCC1 and MUS81-EME1 promote sister chromatid separation by processing late replication intermediates at common fragile sites during mitosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 1008–1015 (2013).

West, S. C. et al. Resolution of recombination intermediates: Mechanisms and regulation. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 80, 103–109 (2016).

Baumann, C., Körner, R., Hofmann, K. & Nigg, E. A. PICH, a Centromere-Associated SNF2 Family ATPase, Is Regulated by Plk1 and Required for the Spindle Checkpoint. Cell 128, 101–114 (2007).

Chan, K. L., North, P. S. & Hickson, I. D. BLM is required for faithful chromosome segregation and its localization defines a class of ultrafine anaphase bridges. EMBO J. 26, 3397–3409 (2007).

Mocanu, C. et al. DNA replication is highly resilient and persistent under the challenge of mild replication stress. Cell Rep. 39, 110701 (2022).

Hengeveld, R. C. C. et al. Rif1 is required for resolution of ultrafine DNA bridges in anaphase to ensure genomic stability. Dev. Cell 34, 466–474 (2015).

Chan, Y. W., Fugger, K. & West, S. C. Unresolved recombination intermediates lead to ultra-fine anaphase bridges, chromosome breaks and aberrations. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 92 (2018).

Adam, S. et al. The CIP2A–TOPBP1 axis safeguards chromosome stability and is a synthetic lethal target for BRCA-mutated cancer. Nat. Cancer 2, 1357–1371 (2021).

De Marco Zompit, M. et al. The CIP2A-TOPBP1 complex safeguards chromosomal stability during mitosis. Nat. Commun. 13, 4143 (2022).

Lin, Y. F. et al. Mitotic clustering of pulverized chromosomes from micronuclei. Nature 618, 1041–1048 (2023).

Trivedi, P., Steele, C. D., Au, F. K. C., Alexandrov, L. B. & Cleveland, D. W. Mitotic tethering enables inheritance of shattered micronuclear chromosomes. Nature 618, 1049–1056 (2023).

Kumagai, A., Lee, J., Yoo, H. Y. & Dunphy, W. G. TopBP1 activates the ATR-ATRIP complex. Cell 124, 943–955 (2006).

Wardlaw, C. P., Carr, A. M. & Oliver, A. W. TopBP1: A BRCT-scaffold protein functioning in multiple cellular pathways. DNA Repair 22, 165–174 (2014).

Pedersen, R. T., Kruse, T., Nilsson, J., Oestergaard, V. H. & Lisby, M. TopBP1 is required at mitosis to reduce transmission of DNA damage to G1 daughter cells. J. Cell Biol. 210, 565–582 (2015).

Ummethum, H., Li, J., Lisby, M. & Oestergaard, V. H. Emergingroles of the CIP2A-TopBP1 complex in genome integrity. NAR Cancer 5, zcad052 (2023).

Leimbacher, P. A. et al. MDC1 Interacts with TOPBP1 to Maintain Chromosomal Stability during Mitosis. Mol. Cell 74, 571–583 (2019).

Hell, S. W. & Wichmann, J. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 19, 780 (1994).

Sahl, S. J., Hell, S. W. & Jakobs, S. Fluorescence nanoscopy in cell biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 685–701 (2017).

Stok, C. et al. FIRRM/C1orf112 is synthetic lethal with PICH and mediates RAD51 dynamics. Cell Rep. 42, 112668 (2023).

Dehé, P. M. & Gaillard, P. H. L. Control of structure-specific endonucleases to maintain genome stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 315–330 (2017).

Wyatt, H. D. M., Laister, R. C., Martin, S. R., Arrowsmith, C. H. & West, S. C. The SMX DNA repair tri-nuclease. Mol. Cell 65, 848–860 (2017).

Muñoz, I. M. et al. Coordination of structure-specific nucleases by human SLX4/BTBD12 is required for DNA repair. Mol. Cell 35, 116–127 (2009).

Fekairi, S. et al. Human SLX4 is a holliday junction resolvase subunit that binds multiple DNA repair/recombination endonucleases. Cell 138, 78–89 (2009).

Svendsen, J. M. et al. Mammalian BTBD12/SLX4 assembles a holliday junction resolvase and is required for DNA repair. Cell 138, 63–77 (2009).

Wang, J. et al. Oncoprotein CIP 2A is stabilized via interaction with tumor suppressor PP 2A/B56. EMBO Rep. 18, 437–450 (2017).

Leem, J., Kim, J. S. & Oh, J. S. Oocytes can repair DNA damage during meiosis via a microtubule-dependent recruitment of CIP2A-MDC1-TOPBP1 complex from spindle pole to chromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 4899–4913 (2023).

McCarthy, E. E., Celebi, J. T., Baer, R. & Ludwig, T. Loss of Bard1, the Heterodimeric Partner of the Brca1 Tumor Suppressor, Results in Early Embryonic Lethality and Chromosomal Instability. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 5056–5063 (2003).

Becker, J. R. et al. BARD1 reads H2A lysine 15 ubiquitination to direct homologous recombination. Nature 596, 433–437 (2021).

Matos, J., Blanco, M. G., Maslen, S., Skehel, J. M. & West, S. C. Regulatory control of the resolution of DNA recombination intermediates during meiosis and mitosis. Cell 147, 158–172 (2011).

Matos, J., Blanco, M. G. & West, S. C. Cell-cycle kinases coordinate the resolution of recombination intermediates with chromosome segregation. Cell Rep. 4, 76–86 (2013).

Szakal, B. & Branzei, D. Premature Cdk1/Cdc5/Mus81 pathway activation induces aberrant replication and deleterious crossover. EMBO J. 32, 1155–1167 (2013).

Gallo-Fernández, M., Saugar, I., Ortiz-Bazán, M. Á, Vázquez, M. V. & Tercero, J. A. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the nuclease activity of Mus81-Eme1/Mms4. Nucleic Acids Res 40, 8325–8335 (2012).

Domínguez-Kelly, R. et al. Wee1 controls genomic stability during replication by regulating the Mus81-Eme1 endonuclease. J. Cell Biol. 194, 567–579 (2011).

Duda, H. et al. A Mechanism for Controlled Breakage of Under-replicated Chromosomes during Mitosis. Dev. Cell 39, 740–755 (2016).

Payliss, B. J. et al. Phosphorylation of the DNA repair scaffold SLX4 drives folding of the SAP domain and activation of the MUS81-EME1 endonuclease. Cell Rep. 41, 111537 (2022).

Gritenaite, D. et al. A cell cycle-regulated Slx4-Dpb11 complex promotes the resolution of DNA repair intermediates linked to stalled replication. Genes Dev. 28, 1604–1619 (2014).

Germann, S. M. et al. TopBP1/Dpb11 binds DNA anaphase bridges to prevent genome instability. J. Cell Biol. 204, 45–59 (2014).

Martin, P. R. et al. The mitotic CIP2A-TOPBP1 axis facilitates mitotic pathway choice between MiDAS and MMEJ. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.12.621593 (2024).

Brambati, A. et al. RHINO directs MMEJ to repair DNA breaks in mitosis. Science 381, 653–660 (2023).

Ceccaldi, R. et al. Homologous-recombination-deficient tumours are dependent on Polθ -mediated repair. Nature 518, 258–262 (2015).

van Vugt, M. A. T. M. & Tijsterman, M. POLQ to the rescue for double-strand break repair during mitosis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 1828–1830 (2023).

van de Kooij, B. et al. EXO1 protects BRCA1-deficient cells against toxic DNA lesions. Mol. Cell 84, 659–674.e7 (2024).

Kok, Y. P. et al. Oncogenesis Overexpression of Cyclin E1 or Cdc25A leads to replication stress, mitotic aberrancies, and increased sensitivity to replication checkpoint inhibitors. Oncogenesis 9, 88 (2020).

Ran, F. A. et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308 (2013).

Kendall, J. et al. Oncogenic cooperation and coamplification of developmental transcription factor genes in lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 16663–16668 (2007).

Heijink, A. M. et al. Sister chromatid exchanges induced by per-turbed replication can form independently of BRCA1, BRCA2 and RAD51. Nat. Commun. 13, 6722 (2022).

Wiederschain, D. et al. Single-vector inducible lentiviral RNAi system for oncology target validation. Cell Cycle 8, 498–504 (2009).

de Lange, E. M. F. & Vlijm, R. Super-Resolution imaging of peroxisomal proteins using STED nanoscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2643, 65–84 (2023).

Mol, F. N. & Vlijm, R. Automated STED nanoscopy for high-throughput imaging of cellular structures. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.29.510126 (2022).

Göttfert, F. et al. Coaligned dual-channel STED nanoscopy and molecular diffusion analysis at 20 nm resolution. Biophys. J. 105, L01–L03 (2013).

Evans, R. et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.04.463034 (2021).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022).

Goddard, T. D. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 27, 14–25 (2018).

Mol, F. N. & Vlijm, R. Interactive Wiener Filter. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15075206 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The work described in this study was financially supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant #12911 to M.A.T.M.v.V) and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO VICI #09150182110019 to M.A.T.M.v.V, OCENW.M #21.106 to R.V.). P.J.H. acknowledges funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF - PAT1893225). J.R.C. was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC, UK) project grant MR/R017549/1 and MRC Molecular Hematology Unit grants MC_UU_00016/19 and MC_UU_00029/2. We thank Simona Smolková and the Max Perutz Labs BioOptics facility for microscopy support. We thank dr. Manual Stucki, dr. Andrew Blackford, dr. Wojciech Niedzwiedz and dr. Peter Martin for constructive discussions and discussing unpublished work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.T.M.v.V. conceived the project. L.d.H, A.G-L., D.R., P.M., H.R.d.B, F.J.B., M.E., and B.v.d.K. performed and analyzed wet lab experiments. S.J.D., F.N.M., and R.V. designed and carried out STED imaging and line profile analysis. S.J.D., H.W,. and L.d.H. analyzed STED images. H.R.d.B. conducted and analyzed proteomics analysis. P.J.H. performed structure analysis. P.M. and P.J.H. performed and analyzed Airyscan imaging. J.R.S. provided reagents. L.d.H. and M.A.T.M.v.V. wrote the manuscript. All authors provided input on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.A.T.M.v.V. has acted on the Scientific Advisory Board of RepareTX and Nodus Oncology, unrelated to this work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Maarten W. Paul and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Haan, L., Dijt, S.J., García-López, A. et al. CIP2A mediates mitotic recruitment of SLX4/MUS81/XPF to resolve replication stress-induced DNA lesions. Nat Commun 17, 13 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66549-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66549-3