Abstract

Biosynthesis of all androgens and estrogens from cholesterol requires CYP11A1 and CYP17A1. There is no known pathway in humans or other vertebrates that circumvents CYP17A1 for androgen or estrogen biosynthesis in physiology or disease. However, CYP17A1 inhibition cannot completely inhibit androgen biosynthesis in prostate cancer. Here, we identify a surprising role for CYP51 in androgen biosynthesis that bypasses the requirement for CYP17A1. We find that an oxysterol is converted to androgens, which we confirmed with synthesis of a deuterium-labeled oxysterol precursor. Of 57 human cytochrome P450 enzymes tested, only CYP51A1 is capable of circumventing CYP17A1. Genetic studies using stable isotope tracing demonstrate that CYP51A1 is essential for biosynthesis of 13C-testosterone from 13C-cholesterol. Other vertebrate orthologs of human CYP51A1 also synthesize androgens. CYP51A1 knockout suppressed androgen-regulated genes in vitro and in vivo in prostate cancer xenografts. These findings have broad implications for sex steroid physiology and pharmacologic therapies for steroid-dependent diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Steroid receptors appear in evolution alongside the arrival of vertebrates1. The biosynthetic pathways of steroids presumably co-evolved to accompany their respective receptors for development of hormonal and physiological processes. Androgens are a class of steroids that are required for male sexual differentiation, progression of steroid-dependent cancers (e.g., prostate cancer), and serve as a requisite precursor for the biosynthesis of estrogens and their respective functions2.

The biosynthesis of all androgens from cholesterol in humans and other vertebrates requires two cytochrome P450 enzymes3,4. First, cytochrome P450 11A1 (CYP11A1) cleaves 6 carbons from the side chain of 27-carbon cholesterol to make 21-carbon pregnenolone (Fig. 1A). Second, in a 2-step process, cytochrome P450 17-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase (CYP17A1) cleaves carbons 20 and 21 from pregnanes to make 19-carbon androgens, e.g., conversion from pregnenolone to dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). The identification of this pathway eventually led to the development of CYP17A1 pharmacologic inhibitors for the treatment of prostate cancer5,6. However, CYP17A1 inhibition does not completely abolish androgen biosynthesis and thus suggests the possibility of a CYP17A1-independent pathway7. To our knowledge, no biochemical pathways that circumvent CYP17A1 have been identified in humans or other vertebrates that result in androgen or estrogen biosynthesis2,3,8.

A Steroid biosynthesis and canonical requirement for the CYP17A1 enzyme to synthesize 19-carbon androgens. B Intracellular testosterone and DHT levels in charcoal-stripped serum-starved or serum-free starved C4-2 prostate cancer cells cultured for 5 days. From n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples. C Intracellular androgen levels in parental and HSD3B1 knockout (KO) C4-2 cells. Also shown are the metabolic consequences of blocking HSD3B1 (encoding 3βHSD1) on the steroid A/B ring for testosterone and DHT biosynthesis. From n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples. N.D. not detectable. D Chromatography of 13C3-testosterone and the levels of intracellular 13C3-testosterone in ethanol- or 15 µM 13C3-cholesterol -treated wild-type or HSD3B1 KO C4-2 cells. Cell pellets were collected after 5 days. 13C3-Testosterone was measured by LC-MS/MS. From n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples except n = 4 for control treated with 13C3-cholesterol samples. The chromatogram displays detection of 13C3-testosterone. E Intracellular androgens in C4-2 cells treated with ethanol (EtOH) or the CYP17A1 inhibitors, TAK700 or ASN001. From n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples. All steroid measurements were performed using LC-MS/MS and are presented as mean +/− SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Here, we report the discovery of a CYP17A1-independent pathway of androgen biosynthesis. The pathway utilizes 17α,20-dihydroxycholesterol (DHC) and requires 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 (3βHSD1 encoded by HSD3B1) for conversion of the 3β-OH and Δ5-steroid A/B ring structures of cholesterol and DHEA to the 3-keto structures of testosterone and 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Surprisingly, cytochrome P450 51A1 (CYP51A1) (the human ortholog of CYP51) is the only cytochrome P450 out of 57 tested that synthesizes DHEA, resulting in the production of testosterone and DHT from an oxysterol independent of CYP17A1. Furthermore, expression of aromatase enables conversion of oxysterol-derived androgens to estrogens. Stable isotope tracing studies confirm this pathway. The preserved androgen biosynthesis activity of CYP51 orthologs from other vertebrates suggests that DHEA biosynthesis is present in organisms that biosynthesize steroids. Finally, CYP51A1 KO in a mouse xenograft model of prostate cancer shows loss of AR signaling in mice that have undergone castration. Together, our findings identify a biochemical pathway of androgen and estrogen biosynthesis that excludes the requirement for CYP17A1 and point toward an entirely unexpected cytochrome P450 enzyme in regulating steroid hormone physiology across vertebrates and in cancer.

Results

Androgen biosynthesis does not require CYP17A1

A simplified diagram of canonical androgen biosynthesis and its requirement for CYP17A1 is shown in Fig. 1A. The human-derived C4-2 prostate cancer cell line model synthesizes testosterone and DHT, which we find are detectable in cell pellets by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) after 5 days of culture in charcoal-stripped serum (CSS) or serum-free medium (Fig. 1B). However, androgens are undetectable in CSS. Additionally, CYP11A1 protein, CYP17A1 protein, and CYP17A1 activity are undetectable in C4-2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). Intracellular testosterone and DHT are also detected in two other human prostate cancer cell line models that are either deficient in androgen glucuronidation activity or when the enzymes that catalyze steroid glucuronidation are deleted9 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Intracellular biosynthesis of testosterone and DHT is lost with CRISPR KO of HSD3B1, thus demonstrating the requirement for the same downstream enzymatic machinery for transformation of the steroid A/B rings using 3βHSD1 that normally occurs with CYP17A1-dependent androgen biosynthesis (Fig. 1C). C4-2 cells harbor the adrenal-permissive HSD3B1 allele and thus are known to have robust 3βHSD1 metabolic activity10,11. Stable isotope tracing studies with 13C3-cholesterol show intracellular conversion to 13C3-testosterone and the requirement for 3βHSD1 (Fig. 1D). Two steroidal CYP17A1 inhibitors, abiraterone and galeterone, along with their metabolites, are also known inhibitors of 3βHSD1 and thus cannot be used to isolate the effects of CYP17A1 on testosterone and DHT biosynthesis because 3βHSD1 inhibition stops metabolism at DHEA, which is a substrate of 3βHSD1 (Fig. 1C)12,13,14. We therefore tested the effects of pharmacologic inhibition using the non-steroidal CYP17A1 inhibitors ASN001 and TAK70015, which showed intracellular testosterone and DHT biosynthesis was unaffected by CYP17A1 blockade in C4-2 cells (Fig. 1E). Similarly, CRISPR knockout (KO) of CYP17A1 or CYP11A1 does not affect intracellular testosterone or DHT levels in C4-2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Selective oxysterol conversion to androgens and estrogens

Cholesterol oxidation yields multiple types of oxysterols. C4-2 cells were treated with the oxysterols in Fig. 2A, cell pellets were harvested after the designated incubation times, and LC-MS/MS was performed for androgen quantitation. Of the oxysterols tested, only DHC was an apparent substrate for the biosynthesis of DHEA, testosterone, and DHT (Supplementary Fig. 4). C4-2 cells showed increased biosynthesis of DHEA in response to DHC in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B) and time-dependent biosynthesis of testosterone and DHT (Fig. 2C). Genetic knockout of HSD3B1 inhibits testosterone and DHT biosynthesis from DHC because metabolism stops at DHEA (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, androgen biosynthesis from DHC treatment induces expression of androgen-regulated genes in parental C4-2 cells (Fig. 2E). Androgen-regulated gene expression is reversed with genetic ablation of HSD3B1 (Fig. 2F). Finally, DHC treatment results in the generation of both estrone and estradiol in JEG3 placental choriocarcinoma cells that were used because they have robust endogenous 3βHSD1 and aromatase activity (Supplementary Fig. 5). Together, these data show oxysterol-selective and CYP17A1-independent androgen and estrogen biosynthesis, which require steroid A/B ring transformation by 3βHSD1 to make both types of sex steroids.

A Structures of cholesterol, (20 R)−17α,20-dihydroxycholesterol (DHC), and other tested oxysterols. B, C Androgen levels (B) and time course (C) of DHC-treated C4-2 cells. Cells were harvested at the indicated times, and intracellular androgen levels were measured by LC-MS/MS. From n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples. Data are presented as Mean +/− SD. D Androgen levels in DHC-treated (100 nM) parental or HSD3B1 knockout (KO) C4-2 cells. Cells were harvested and intracellular androgen levels were measured by LC-MS/MS. From n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples. Data are presented as mean +/− SD. E Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using gene expression data from wild-type C4-2 cells treated with either vehicle (ethanol) or 100 nM DHC for 4 days. n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples per group. The enriched pathway was identified by an adjusted p-value, using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. F FKBP5 expression levels in parental and HSD3B1 KO C4-2 cells. Cells were starved, treated with ethanol or 100 nM DHC, and harvested at the indicated times. FKBP5 mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR and normalized to RPLP0. From n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples. Data are presented as Mean +/− SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Androgen biosynthesis from DHC is independent of CYP17A1

The conversion of DHC to DHEA and testosterone was not blocked by CYP17A1 inhibitor treatment (Fig. 3A). The non-steroidal CYP17A1 inhibitors do not affect the generation of DHEA and testosterone, whereas the consequences of treatment with the steroidal drug galeterone indicate known off-target inhibition of 3βHSD114, which is observed experimentally as accumulation of DHEA and modest depletion of testosterone (Fig. 3A). To definitively track DHC metabolism, we synthesized deuterium-labeled DHC (DHC-C7-d2; d2-DHC) (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 6) and observed conversion to d2-DHEA, d2-testosterone and d2-DHT (Fig. 3C). Intracellular biosynthesis of d2-testosterone and d2-DHT was reduced by treatment with abiraterone or ketoconazole. d2-DHEA increased with abiraterone, which is consistent with no effect of CYP17A1 blockade alongside 3βHSD1 inhibition (Fig. 3C). In contrast, ketoconazole, which blocks multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes including CYP51A116,17, lowered all androgens. Additional androgens are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Together, these data are consistent with a role for androgen biosynthesis that necessitates a cytochrome P450 enzyme other than CYP17A1.

A Intracellular DHEA, testosterone, and DHT levels in charcoal-stripped serum starved or serum-free starved C4-2 cells. Cells were starved, treated with 100 nM DHC with or without CYP17A1 inhibitors, and harvested after 5 days. From n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples. Shown are pathway consequences of galeterone blockade of 3βHSD1. B Structure of deuterium-labeled (20 R)−17α,20-dihydroxycholesterol (DHC). C Intracellular deuterium-labeled androgens or DHEA levels in ethanol-, abiraterone-, or ketoconazole-treated C4-2 cells. Cells were starved, treated with 100 nM deuterium-labeled DHC with or without CYP17A1 inhibitors, and harvested after 5 days. From n = 3 biological intra-assay replicate samples. All measurements were done by LC-MS/MS and are presented as mean +/− SD. Shown are pathway consequences of abiraterone blockade of 3βHSD1 and ketoconazole blockade of an unknown cytochrome enzyme. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

CYP51A1 is required for CYP17A1-independent androgen biosynthesis

To identify a potential alternative cytochrome enzyme, we expressed all 57 human cytochrome P450 enzymes (Supplementary Table 2) individually in C4-2 cells, treated cells with DHC, and measured intracellular DHEA by LC-MS/MS. Only CYP51A1 enabled the biosynthesis of DHEA (Fig. 4A). Neither CYP17A1 nor CYP11A1 expression resulted in DHEA biosynthesis from DHC. CYP11A1 and CYP1A1 activities were measured to show that the cytochromes are successfully transfected with expected activity (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). Treatment of CYP51A1-overexpressing C4-2 cells and LNCaP with d2-DHC also led to biosynthesis of d2-DHEA, d2-testosterone, and d2-DHT (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 9). In 293 T cells overexpressing CYP51A1, d2-DHEA biosynthesis is reversible with ketoconazole but not CYP17A1-specific pharmacologic inhibitors (Fig. 4C). Purified human CYP51A1 from an Escherichia coli expression system generated DHEA in a DHC-dependent manner (Fig. 4D, E and Supplementary Fig. 10). Finally, human CYP51A1 orthologs from mouse, xenopus and zebrafish, all synthesized DHEA from DHC (Fig. 4F, Supplementary Fig. 11, and Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, CYP51 orthologs from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and plant Arabidopsis thaliana did not synthesize DHEA from DHC. Together, these data demonstrate the unique role of CYP51A1 among all the cytochromes for androgen biosynthesis from oxysterols and that the biochemical activity is conserved across vertebrates that are generally known to utilize steroids in physiologic processes.

A All 57 CYP enzymes were individually expressed in C4-2 cells, and then the cells were treated with 500 nM DHC. Intracellular DHEA levels were analyzed after 96 h. B Intracellular deuterium-labeled androgen levels from deuterium-labeled DHC (d2-DHC) in control or CYP51A1-overexpressing (OE) C4-2 cells. C Effects on d2-DHEA biosynthesis with or without abiraterone, ASN001, or ketoconazole in CYP51A1 overexpressing 293 T cells. Cells were starved, treated with indicated compounds, and harvested after 5 days. Shown are pathway consequences of abiraterone blockade of 3βHSD1 and ketoconazole blockade of CYP51A1. D In vitro reaction of recombinant human CYP51A1 enzyme with 25 µM DHC. Recombinant CYP51A1, NADPH, and DHC were combined as indicated and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. DHEA levels were measured by LC-MS/MS. A proposed mechanism is shown. E Steady-state kinetics of CYP51A1 following treatment with DHC (0–100 µM). The estimated kcat is 3.74 ± 0.08 × 10−3 min−1 and Km value of 12.4 ± 0.8 µM for DHC. F CYP51 enzymes from different species were expressed in 293 T cells, which then were treated with 500 nM DHC for 5 days. All steroid measurements were performed using LC-MS/MS and are presented as mean +/− SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

CYP51A1 and androgen signaling in prostate cancer

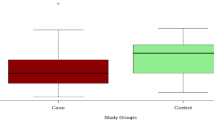

C4-2 cells with CYP51A1 CRISPR KO and control cells were treated with or without DHC (100 nM) and signaling consequences were assessed by RNA-seq methods (Fig. 5A). Canonical androgen-responsive genes were induced by DHC in a CYP51A1-dependent manner. We were unable to detect endogenous DHC in prostate cancer cell lines, human blood or prostate tissue (Supplementary Fig. 12). This is possibly due to (1) insufficient sensitivity for DHC detection, (2) the transient nature of endogenously produced DHC (which is likely rapidly converted in cells to DHEA), or (3) an alternative intermediate oxysterol is utilized by CYP51A1 for androgen biosynthesis. To resolve this issue related to the question of CYP17A1-independent androgen biosynthesis from endogenous precursors, we assessed CYP51A1-dependent androgen biosynthesis via 13C3-cholesterol. CYP51A1 KO in two independent clones suppressed biosynthesis of 13C3-testosterone from 13C3-cholesterol (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that intracellular conversion from cholesterol to an intermediate oxysterol metabolite precedes CYP51A1-dependent biosynthesis of androgens. Next, to further interrogate this issue in vivo, C4-2 prostate cancer xenografts with or without CYP51A1 expression in two independent KO clones were grown in orchiectomized mice to assess androgen signaling in the absence of gonadal testosterone. Tumor growth was significantly delayed in both CYP51A1 KO clone 1 (p < 0.0001) and CYP51A1 KO clone 2 (p = 0.004) compared to control xenograft (Fig. 5C). Xenograft tissue from both CYP51A1 KO xenografts showed loss of PSA mRNA and protein (Fig. 5D, E). Together, these data show that CYP51A1 utilizes endogenously generated sterols to elicit androgen signaling through a bypass pathway around CYP17A1 (Fig. 6).

A Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed to evaluate the androgen response hallmark in control and CYP51A1 knockout cells. Both cell groups were treated with 100 nM DHC for 4 days. The androgen response hallmark was subsequently analyzed in both conditions. n = 3 biological intra-assay replicates samples per group. The enriched pathway was identified by an adjusted p-value, using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. B Intracellular 13C3-testosterone levels in control or CYP51A1 knockout (KO) C4-2 cells. Cells were treated with 13C3-cholesterol and harvested after 5 days. 13C3-testosterone was measured by LC-MS/MS. From n = 4 biological intra-assay replicate samples. The data are presented as mean +/− SD. C Control or CYP51A1 KO C4-2 cells were injected subcutaneously in castrated NSG mice, and tumor volume was measured by ultrasound imaging. Tumor growth over time in the groups were compared by two-way ANOVA. The data are presented as mean +/− SEM. D mRNA and protein levels of PSA in control and CYP51A1 KO C4-2 xenografts. Six control and five CYP51A1 KO xenografts were stained using a PSA antibody, and PSA expression was analyzed by real-time-PCR. Groups were compared by two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. CYP51A1 KO xenografts had lower levels of mRNA (control v. KO1 p = 0.0158; control v. KO2 p = 0.002) and protein (control v. KO1 p = 0.0108; control v KO2 p = 0.0348). E Representative PSA immunohistochemistry images are shown for each group (n = 3 xenograft experiments). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

CYP17A1 catalyzes at least 13 different reactions and is known to be required for androgen biosynthesis from 21-carbon precursors18. The study of humans with CYP17A1 loss-of-function first led to the discovery of the biochemical basis for loss of sex steroid biosynthesis19. These discoveries and an understanding of sex steroid biosynthesis in turn spurred the development of CYP17A1 inhibitors for prostate cancer therapy5. The persistence of androgens despite CYP17A1 inhibition inspired the search for an alternative enzyme in the body of work presented here.

The known function of CYP51A1 is 14α-demethylation of lanosterol, a critical step in the pathway of cholesterol biosynthesis20,21. Our unbiased expression screen unexpectedly revealed a role for CYP51A1 in androgen biosynthesis from oxysterols that clearly stood out from all the other CYP enzymes expressed. The same activity does not occur with CYP17A1. Our data suggest that CYP51A1 expression in the prostate cancer cells is utilized for cell-autonomous synthesis of DHEA and other androgens. However, it is also possible that CYP51A1 activity outside prostatic tissues also contributes to androgen biosynthesis. This should be an area for further investigation.

Physiologically, cholesterol is processed to a diverse array of metabolites, including steroids, oxysterols, and bile acids. Depending on their identity, the detection of oxysterols is challenging because of hydrophobicity, poor ionization in mass spectrometry, and the presence of very closely related chemical structures22. Although DHC has been described previously23,24, we were unable to definitively identify endogenous DHC in blood or prostate tissue. Nevertheless, our isotope tracing experiments very clearly demonstrate that 13C3-cholesterol is metabolized to androgens in a CYP51A1-dependent manner and that genetic ablation of CYP51A1 leads to loss of androgen signaling in vivo in the absence of exogenously delivered substrates. Together, these data suggest that either DHC is a transiently generated metabolite from cholesterol or that CYP51A1 utilizes an alternative oxysterol for the CYP17A1-independent biosynthesis of androgens. While we demonstrate estrogen biosynthesis from DHC, our data on estrogens are much more limited compared with the data we present on androgens and require additional study in vivo.

The conserved androgen biosynthesis activity of CYP51 orthologs in vertebrates appears to accompany the evolution of steroid receptors in the same animals25. This activity suggests that this biochemical activity of CYP51 occurred alongside the evolution of steroid physiology. Our data clearly point toward a CYP17A1-independent role for sex steroid biosynthetic activity that is conserved across multiple species. However, the data suggest that the efficiency of androgen biosynthesis by CYP51A1 is much lower than CYP17A1. The role of CYP51A1 in androgen biosynthesis probably becomes most relevant with CYP17A1 inhibition in prostate cancer. Nevertheless, we believe these data open the door to the possibility of previously unknown physiologic consequences of steroid regulation across multiple organisms, which we think should be studied further.

Materials and methods

Cloning and plasmids

Constructs of CRISPR targeting CYP51A1 (5′-ATCATCTTACCAGCTCCAAA-3′) and HSD3B1 (5′-GAAGGTTTCTGTCCTAATCAT-3′) were purchased from Genscript (Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). Lentiviral-expressing cytochrome P450 plasmids were purchased from DNASU Plasmid Repository(Tempe, Arizona, USA), synthesized from Vectorbuilder (Chicago, Illinois, USA), or subcloned into lentiviral expression vectors in house. The CYP51A1 orthologs were codon-optimized for human expression, inserted into lentiviral vectors, and tagged at the C-terminus with a FLAG tag, followed by a 2A peptide sequence and GFP by Vectorbuilder.

Immunoblots

Antibodies: Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CYP51A1(1:2000, NBP2-48733) were purchased from Novus (Centennial, Colorado, USA). Mouse monoclonal antibodies 3βHSD1 (1:1000, ab55268) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Androgen receptor (AR N-20, 1:2000, sc-816) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CYP17A1 (1:500, LS-B14227-200) were purchased from LifeSpan BioSciences (Newark, California, USA). Rabbit recombinant monoclonal antibodies V5 tag (1:1000, 13202S), CYP11A1 (1:500, 14217S), and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against β-actin (1:3,000, 3700S) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, Massachusetts, USA).

For immunoblots, total cellular protein was extracted with ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) containing protease inhibitors (Roche, Pleasanton, California, USA). Protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Proteins (30–100 µg) were separated by 4–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (4568085, Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA). After incubating overnight at 4 °C with the antibodies, the appropriate secondary antibody was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. A chemiluminescent detection system (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) was used to detect the bands with peroxidase activity. β-Actin was used as a control for sample loading.

Chemicals and reagents

Chemicals

[3H]-labeled DHEA was purchased from PerkinElmer, Shelton, Connecticut, USA; DHC (TRC-D450180) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals, Vaughan, Ontario, Canada; and the other oxysterols were purchased from Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. ASN001 is a gift from Asana Biosciences, Lawrenceville, New Jersey, USA. Other CYP17 inhibitors were purchased from Selleck, Houston, Texas, USA, and steroids were purchased from Steraloids, Newport, Rhode Island, USA.

Reagents

Puromycin (A1113803) was bought from ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA. DNA transfection reagent FuGENE HD (E2311) was purchased from Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Dideuterated 17,20-DHC synthesis

Acetic anhydride (Ac2O) was utilized to protect the secondary hydroxyl group at C3 position in the standard DHC. Subsequently, Co(OAc)2 was employed to catalyze the oxidation process, resulting in the formation of a carbonyl group at the C7 position. The final reduction by LiAlD4 provided the d2-DHC with a 48% yield.

DHC (50 mg) and 0.6 mg of tosylic acid (TsOH) monohydrate were added to 71 µL of acetic anhydride (Ac2O) and 0.45 mL of pyridine. The reaction was completed after 16 h, yielding 52 mg of acetylated DHC in 85% yield. The subsequent oxidation was facilitated by 1 mol% cobalt(II) acetate (Co(OAc)2), 10% N-Hydroxyphthalimide as co-catalysts, 13.8 mg of acetylated DHC, and 400 mol% of tert-butyl hydroperoxide as the oxidant were introduced into 1 mL of acetone at ambient temperature. After 12 h, it produced 11.1 mg of the 7-oxidized product, achieving a yield of 78%. The final dideuterated (DHC) was produced using a reduction process involving 720 mol% of LiAlD4 and 2240 mol% of AlCl3 in ether:THF under reflux conditions, yield 48%.

Cell lines

LNCaP, C4-2, and JEG3 cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) with 10% FBS (Geminibio, West Sacramento, California, USA). LAPC4 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Charles Sawyers (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA) and grown in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) with 10% FBS. The cells were authenticated by short tandem repeat analysis at LabCorp (Burlington, North Carolina, USA). We checked all cell lines for mycoplasma contamination routinely.

To generate the CYP51A1 or HSD3B1 knockout C4-2 stable cell lines by using a lentiviral system, 293 T cells (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA) were co-transfected for 48 h with 10 µg each of the constructed plasmid, pMD2.G, and psPAX2 vector to package the virus. Next, LNCaP or C4-2 cells were infected with the concentrated virus for 24 h with 10 µg/mL polybrene (Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA) and then selected with puromycin (2 µg/mL).

To screen the CYP enzymes, lentiviral-expression plasmids were co-transfected into 293 T cells with pMD2.G and psPAX2 for 48 h to generate lentiviral particles. Subsequently, C4-2 or 293 T cells were transduced with the lentivirus for 24 h with 10 µg/mL polybrene (Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA). CYP expressions were verified by Western blot analysis using V5 or flag tag. Transduced cells were then seeded into 6-cm dishes, serum starved 5 days upon reaching confluence and treated with 500 nM DHC for 4 days. Following treatment, cells were harvested by scraping, and intracellular androgen levels were quantified.

To evaluate the activity of CYP51A1 orthologs, their plasmids were transfected into 293 T cells for lentivirus production. Stable 293 T and C4-2 cell lines expressing these orthologs were established, and their activities were subsequently assessed.

Steroid metabolism and mass-spectrometry analysis

To measure endogenous intracellular androgen levels, cells were grown to confluence in 10 cm dishes using RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were then starved with RPMI 1640 medium with 10% charcoal-stripped FBS (CSS medium) for 5 days or 5 days in CSS medium followed by an additional 5 days in 0.1% CSS medium (serum-free medium).

To test oxysterol conversions, cells were first starved for 5 days using 10% CSS medium. Subsequently, they were treated with a specific concentration of oxysterols suspended in fresh 10% CSS medium. In the inhibitory experiments, 50 µM of TAK700, 16 µg/mL of ASN001, 5 µM ketoconazole, and 10 µM of either abiraterone or galeterone were used.

To trace 13C3-labeled androgen production from 13C3-cholesterol (Cholesterol-2,3,4-13C3, 749478, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), cells were starved with CSS medium for 5 days. They were then loaded with 15 µM of 13C3-cholesterol using methyl-β-cyclodextrin (C4555, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) according to a specific protocol26.

The cell pellets were scraped and centrifuged at 2000 × g after the treatments. The cell membranes were disrupted using freeze-thaw cycles, and the steroids were extracted by methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The extracted steroids were subsequently analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Wild-type and UGT-KO LNCaP samples were treated with β-glucuronidase (1000 units; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) for 3 h before extraction as mentioned previously. C4-2 samples were extracted without β-glucuronidase treatment because C4-2 cells do not have UGT activity.

Freshly collected cells were stored at −80 °C until analysis. Frozen cells were thawed and subjected to 6 freeze-thaw cycles, followed by spiking with an internal standard mix (androstene-3,17-dione-2,3,4-13C3, 5α-dihydrotestosterone-16,17,17-d3, pregnenolone-17,21,21,21-d4, 17β-estradiol-2,3,4-13C3, and cortisol-9,11,12,12-d4). Steroids were extracted using liquid-liquid extraction with MTBE. The steroid fraction was collected, dried, and reconstituted in 50% methanol for LC-MS/MS analysis.

The following parameters were optimized for LC-MS/MS analysis in positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode to detect DHEA, T, and DHT using an AB Sciex 6500+ system.

The transitions represent the precursor-to-product ion pairs monitored in multiple reaction monitoring mode under ESI+ conditions. Delustering Potential (DP), Entrance Potential (EP), Collision Energy (CE), and Collision Cell Exit Potential (CXP) were optimized for each analyte to maximize sensitivity and specificity.

General mass spectrometry parameters

Mass spectrometry was performed under the following general parameters: the curtain gas (CUR) was set to 40 psi, and the collision gas (CAD) was maintained at medium pressure. The IonSpray voltage (IS) was 4800 V, with a source temperature (TEM) of 450 °C. Ion Source Gas 1 (GS1) and Ion Source Gas 2 (GS2) were set to 40 psi and 60 psi, respectively.

Compound-specific mass spectrometry parameters

For DHEA, the parent to daughter transition monitored was m/z 271.1 → 213.3, with a DP of 62.0 V, EP of 7.2 V, CE of 25.0 V, and CXP of 24.0 V. For testosterone (T), the parent to daughter transition was m/z 289.1 → 97.0, with a DP of 56.5 V, EP of 8.0 V, CE of 31.2 V, and CXP of 9.0 V. For DHT, the parent to daughter transition was m/z 291.2 → 255.2, with a DP of 60.0 V, EP of 6.6 V, CE of 22.0 V, and CXP of 20.0 V.

Accuracy and precision of the analytical method were evaluated using quality control (QC) samples prepared by spiking CSS media with known standards. Each analytical batch included duplicate calibration curves (one at the start and one at the end) with concentrations of 19.5, 39.1, 156, 625, 1250, and 2500 pg/mL for DHEA, testosterone (T), and DHT. The lower limit of detection (LLOD) and lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) were determined for each analyte, with relative errors (%RE) calculated to assess accuracy. For DHEA, the LLOD was 19.5 pg/mL with a %RE of 3.29%, and the LLOQ was 39.1 pg/mL with a %RE of 2.83%. For testosterone (T), the LLOD was 1.25 pg/mL with a %RE of 6.40%, and the LLOQ was 1.95 pg/mL with a %RE of 5.51%. For DHT, the LLOD was 4.88 pg/mL with a %RE of 0.07%, and the LLOQ was 9.77 pg/mL with a %RE of 0.27%.

Lower limits of detection (LLOD) and quantification (LLOQ), with relative errors (%RE)

Intraday (n = 3) and interday (n = 6) precision and accuracy were assessed at three concentration levels (0.039, 0.156, and 12,500 pg/mL) for each analyte. Precision was expressed as the coefficient of variation (CV, %), and accuracy was reported as relative error (%RE).

For DHEA, intraday accuracy and precision at 0.039 pg/mL were 3.29% RE and 7.70% CV, respectively, and interday values were 0.96% RE and 11.5% CV. At 0.156 pg/mL, intraday values were 12.2% RE and 2.76% CV, while interday values were 0.71% RE and 14.2% CV. At 12,500 pg/mL, intraday results were 0.60% RE and 2.45% CV, and interday values were 1.08% RE and 2.22% CV.

For testosterone (T), the 0.039 pg/mL concentration yielded intraday values of 4.18% RE and 1.84% CV, and interday values of 2.21% RE and 3.98% CV. At 0.156 pg/mL, intraday accuracy and precision were 7.22% RE and 7.83% CV, and interday values were 3.42% RE and 13.4% CV. At 12,500 pg/mL, intraday results were 0.15% RE and 3.10% CV, and interday values were 0.45% RE and 2.72% CV.

For DHT, the 0.039 pg/mL level produced intraday values of 1.34% RE and 5.64% CV, and interday values of 6.00% RE and 7.17% CV. At 0.156 pg/mL, intraday accuracy and precision were 11.9% RE and 7.74% CV, and interday values were 0.03% RE and 14.1% CV. At 12,500 pg/mL, intraday values were 0.12% RE and 1.48% CV, while interday results were 0.32% RE and 1.48% CV.

To measure endogenous androgens or DHC in xenograft tissues and patient tissues, 30–40 mg tumor tissue was homogenized with 500 μL liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry–grade H2O (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) using a homogenizer. The mixture was then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was transferred to a glass tube, followed by the addition of 25 μL internal standard (d3-T). DHC from human serum was extracted with 2 mL n-hexane followed by 2 mL MTBE in the presence of 1 M methanolic potassium hydroxide. The organic layer was evaporated to dryness under nitrogen and then reconstituted with 200 μL 50% methanol.

Samples were analyzed on a Shimadzu UPLC system using a Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 3.5 μm, Agilent, California, USA) coupled to a Sciex 6500+ QTrap mass spectrometer. Data acquisition and processing were performed using Sciex OS (Version 3.3.1.43). The LLOQ of DHC is 0.2 ng/mL.

In vitro CYP51A1 enzymatic reactions

Human cytochrome P450 51A1 (CYP51A1) was recombinantly expressed in E. coli and purified as described27,28. Rat NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) was also expressed in E. coli and purified as described29.

Assays with recombinant CYP51A1 were generally conducted as described20 but with several modifications. Briefly, CYP51A1 (0.45 µM), rat NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (2 µM), and L-α-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (100 µM) were reconstituted in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) containing 10% glycerol (v/v) on ice. Sterol solutions (prepared as 500 µM solutions in 45% (w/v) (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin) were diluted (1:20) in the enzyme mixture to the working concentration (25 µM). Reactions were preincubated (5 min, 37 °C) prior to initiation with a NADPH-regenerating system [0.5 mM NADP+, 10 mM glucose 6-phosphate, and 2 μg/mL glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase30, which brought the reactions to their final volume (0.5 mL) and all reaction components to their final concentrations. Reactions were allowed to proceed (60 min, 37 °C) prior to quenching and extraction of products into dichloromethane (5 mL). The quenched reaction mixtures were centrifuged (1000 × g, 5 min) to separate layers, the majority (4 mL) of the bottom (organic) layer was transferred to fresh vials, and the solvent was removed under a steady stream of nitrogen gas. The dried residue was reconstituted in methanol (0.1 mL) and was transferred to autosampler glass vials for analysis.

Steady-state kinetics of P450 51A1 and 17,20-dihydroxycholesterol were performed generally as described above, with the modification that the sterol concentration was varied. A dilution series of 17,20-dihydroxycholesterol (starting with a 2 mM solution in 45% (w/v) HPCD) was prepared (in HPCD) to yield working solutions of concentrations 20-fold greater than their desired final concentrations. This ensured a variable sterol concentration and a fixed HPCD concentration throughout the experiment. Reaction conditions and sample analysis were performed as previously described. Control reactions (run without NADPH initiation) were performed at each sterol concentration and any product (DHEA) detected in these samples was subtracted from the initiated reactions. Rates are reported as pmol DHEA formed per minute per pmol of P450 51A1. Data were fit to a Michaelis-Menten hyperbolic equation.

Estimation of P450 51A1 K d value

The sterol binding constant to P450 51A1 was estimated by difference spectroscopy as described previously20. Briefly, P450 51A1 (1.0 µM) was prepared in potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4) containing HPCD (~2.25%, w/v). The sample was split between glass cuvettes and a baseline was recorded (350–500 nm). 17,20-Dihydroxycholesterol (in ethanol) was added to the sample cuvette, the reference cuvette received ethanol, and the cuvettes were mixed and spectra were recorded. The rationale for adding a high concentration of HPCD directly to the P450 solution rather than titrating (small volumes of) HPCD-sterol complexes into the enzyme mixture was to prevent sterol precipitation during the experiment, as the binding of 17,20-dihydroxycholesterol to the enzyme was expected to be weak and thus a high concentration of sterol was required in the experiment.

Gene expression assay

Total RNA was extracted with the GenElute Mammalian Total RNA miniprep kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), and 1 µg RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA with the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). An ABI 7500 real-time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, Massachusetts, USA) was used to perform quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis, using iTaq Fast SYBR Green Supermix with ROX (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) in 96-well plates at a final reaction volume of 10 µL. The qPCR analysis was carried out in triplicate with the following primer sets:

FKBP5:

5′-CCCCCTGGTGAACCATAATACA-3′ (forward),

5′-AAAAGGCCACCTAGCTTTTTGC-3′ (reverse);

RPLP0(large ribosomal protein P0, a housekeeping gene),

5′-CGAGGGCACCTGGAAAAC-3′ (forward),

5′-CACATTCCCCCGGATATGA-3′ (reverse).

The FKBP5 mRNA level was normalized to RPLP0 and to vehicle-treated controls. All gene expression experiments were repeated in at least three independent experiments.

Measuring CYP17A1 activity

HEK293T cells were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected with either a control plasmid or a CYP17A1 expression plasmid. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were treated with tritium-labeled pregnenolone for 24 h. The culture media were subsequently collected and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Measuring CYP11A1 activity

HEK293T cells, either control or stably expressing CYP11A1, were treated with 13C3-labeled cholesterol as described above. After a 72-h treatment period, intracellular levels of 13C3-pregnenolone were quantified using mass spectrometry.

Measuring CYP1A1 activity

293 T cells were seeded in opaque white 96 well plates with phenol red-free media and transfected with 0.1 μg of empty vector or CYP1A1 plasmid. CYP1A1 activities from control and CYP1A1 overexpression were measured 3 days after transfection using P450-Glo CYP1A1 Assay kit (Promega V8751, Wisconsin, U.S.A.).

RNA-seq analysis

To investigate the hormonal activity of DHC, we first starved the parental C4-2 cells in CSS media for 3 days. Then the cells were treated with either ethanol or 100 nM DHC for 4 days to determine if DHC induces AR target genes.

To test if CYP51A1 is required for the conversion of DHC to DHEA and subsequently induces AR, both parental and CYP51A1 KO cells were treated in parallel with ethanol or 100 nM DHC for 4 days. The KO cell line was mixed by two CYP51A1 single knockout colonies.

Cells were then harvested, and RNAseq was performed by Genewiz, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA. The resulting data were analyzed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) by fgsea (ver 1.34.2) to investigate the enrichment of AR-dependent gene signatures. The androgen response gene set was cited from GSEA’s hallmark androgen response31,32.

Mouse xenograft studies

Male NSG mice, 8 weeks old, were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (RRID:IMSR_JAX:005557, Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). The mice were castrated by the Jackson Laboratory prior to the study and were allowed to acclimate following delivery. Animals were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle (6:00 AM–6:00 PM) with ambient temperature maintained between 68 and 74° Fahrenheit and humidity maintained below 70 percent. Experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the University of Miami Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (UM IACUC protocol 23-072). Maximum tumor size permitted was 2000 mm3 and was not exceeded. Animals were injected subcutaneously with 106 wild-type or CYP51A1 KO C4-2 cells (n = 15 mice/group). On the day of xenograft implantation, the cells were harvested at 70%–80% confluency and suspended in sterile PBS and kept on ice. The cell suspension was mixed with Matrigel (Corning 356234) 1:1 and 100 μL were injected into the mouse dorsal fat pad using 1 mL insulin syringes with a 27-gauge needle. Mice were weighed twice per week and tumor volume (TV) was measured by ultrasound (Vevo 3100, VisualSonics) with a predetermined survival endpoint of TV ≥ 2000 mm3. At endpoint, tumors were excised, grossly assessed, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen or placed 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis. Mice in which tumors did not successfully engraft (TV ≥ 30 mm3) by the end of the study were euthanized and not included in subsequent analysis. Tumor growth was analyzed by two-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA). Significance was determined at P < 0.05.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tumors were grossed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 48 h. Once fixed, the tissues were processed overnight on a Leica ASP 300S Processor (Leica Biosystems, GmbH, Nußloch, Germany) and embedded in paraffin. Slides were sectioned at 5 µm and stained using a Leica Bond RXm automated research stainer (Leica Biosystems, GmbH, Nußloch, Germany). Slides were baked (60 °C), deparaffinized (BOND Dewax deparaffinization solution), and then underwent epitope retrieval (BOND Epitope Retrieval Solution 1) followed by staining with anti-PSA (Leica PA0431, RTU) in combination with the BOND Polymer Refine HRP Plex Detection kit (Leica DS9914), and counterstained with hematoxylin. Whole slide images were captured using the Leica Aperio AT2 System (Leica Biosystems, GmbH, Nußloch, Germany) and representative images were taken using Aperio ImageScope; signal intensity was quantified using ImageJ. Scale bars for 40× images: 60 μm.

Ethics

The research using human biological specimens was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent was obtained from patients before inclusion in the study. Animal experiment procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of Miami.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The RNAseq data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession code PRJNA1273928. The statistical data generated in this study is provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper. All data supporting the findings of the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Baker, M. E. Steroid receptors and vertebrate evolution. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 496, 110526 (2019).

Auchus, R. J. & Sharifi, N. Sex hormones and prostate cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 71, 33–45 (2020).

Miller, W. L. & Auchus, R. J. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr. Rev. 32, 81–151 (2011).

Dai, C., Heemers, H. & Sharifi, N. Androgen signaling in prostate cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 7, a030452 (2017).

Attard, G. et al. Selective inhibition of CYP17 with abiraterone acetate is highly active in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 3742–3748 (2009).

Ryan, C. J. et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 138–148 (2013).

Mostaghel, E. A. et al. Resistance to CYP17A1 inhibition with abiraterone in castration-resistant prostate cancer: induction of steroidogenesis and androgen receptor splice variants. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 5913–5925 (2011).

Dai, C., Dehm, S. M. & Shari fi, N. Targeting the androgen signaling axis in prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 4267–4427 (2023).

Zhu, Z. et al. Loss of dihydrotestosterone-inactivation activity promotes prostate cancer castration resistance detectable by functional imaging. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 17829–17837 (2018).

Chang, K. H. et al. A gain-of-function mutation in DHT synthesis in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cell 154, 1074–1084 (2013).

Freitas, P. F. S., Abdshah, A., McKay, R. R. & Shari fi, N. HSD3B1, prostate cancer mortality and modifiable outcomes. Nat. Rev. Urol. 22, 313–320 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Conversion of abiraterone to D4A drives anti-tumour activity in prostate cancer. Nature 523, 347–351 (2015).

Li, Z. et al. Redirecting abiraterone metabolism to biochemically fine tune prostate cancer anti-androgen therapy. Nature 533, 547–551 (2016).

Alyamani, M. et al. Steroidogenic Metabolism of Galeterone Reveals a Diversity of Biochemical Activities. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 825–832.e826 (2017).

Wrobel, T. M. et al. Non-steroidal CYP17A1 inhibitors: discovery and assessment. J. Med. Chem. 66, 6542–6566 (2023).

Patel, V., Liaw, B. & Oh, W. The role of ketoconazole in current prostate cancer care. Nat. Rev. Urol. 15, 643–651 (2018).

Nebert, D. W. & Russell, D. W. Clinical importance of the cytochromes P450. Lancet 360, 1155–1162 (2002).

Yoshimoto, F. K. & Auchus, R. J. The diverse chemistry of cytochrome P450 17A1 (P450c17, CYP17A1). J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 151, 52–65 (2015).

Auchus, R. J. The genetics, pathophysiology, and management of human deficiencies of P450c17. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am 30, 101–119 (2001). vii.

McCarty, K. D. et al. Processive kinetics in the three-step lanosterol 14α-demethylation reaction catalyzed by human cytochrome P450 51A1. J. Biol. Chem. 299, 104841 (2023).

Friggeri, L., Hargrove, T. Y., Wawrzak, Z., Guengerich, F. P. & Lepesheva, G. I. Validation of human sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) druggability: structure-guided design, synthesis, and evaluation of stoichiometric, functionally irreversible inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 62, 10391–10401 (2019).

Chen, W., Chen, G., Head, D. L., Mangelsdorf, D. J. & Russell, D. W. Enzymatic reduction of oxysterols impairs LXR signaling in cultured cells and the livers of mice. Cell Metab 5, 73–79 (2007).

Shimizu, K. Metabolism of cholest-5-ene-3β, 20α-diol-7α-3H and of cholest-5-ene-3β, 17, 20α-triol-7α-3H by human adrenal tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 240, 1941–1945 (1965).

Burstein, S., Kimball, H. L., Chaudhuri, N. K. & Gut, M. Metabolism of 17α, 20β-dihydroxycholesterol and 17α, 20β-dihydroxy-20-isocholesterol by guinea pig adrenal preparations. Formation of 3β, 17α-dihydroxypregn-5-en-20-one from these sterols and from cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 4417–4425 (1968).

Thornton, J. W. Evolution of vertebrate steroid receptors from an ancestral estrogen receptor by ligand exploitation and serial genome expansions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5671–5676 (2001).

Mahammad, S. & Parmryd, I. Cholesterol depletion using methyl-β-cyclodextrin. Methods Mol. Biol. 1232, 91–102 (2015).

Hargrove, T. Y. et al. Human sterol 14α-demethylase as a target for anticancer chemotherapy: towards structure-aided drug design. J. Lipid Res. 57, 1552–1563 (2016).

Stromstedt, M., Rozman, D. & Waterman, M. R. The ubiquitously expressed human CYP51 encodes lanosterol 14α-demethylase, a cytochrome P450 whose expression is regulated by oxysterols. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 329, 73–81 (1996).

Hanna, I. H., Teiber, J. F., Kokones, K. L. & Hollenberg, P. F. Role of the alanine at position 363 of cytochrome P450 2B2 in influencing the NADPH- and hydroperoxide-supported activities. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 350, 324–332 (1998).

Guengerich, F. P. In Hayes’ Principles and Methods of Toxicology (eds Hayes, A.W. & Kruger, C. L.) 1905–1964 (CRC Press-Taylor & Francis, 2014).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Mootha, V. K. et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 34, 267–273 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lina Schiffer, Ph.D., and Nikou Fotouhi, Ph.D. who provided insightful discussions, and Cassandra Talerico, Ph.D., and David Rowland, Ph.D., for review of the manuscript. Research reported in this publication was performed in part at the Cancer Modeling Shared Resource (CMSR) of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami, RRID: SCR_022891, which is supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number P30CA240139. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This material is also based in part upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work is supported in part by the Prostate Cancer Foundation. National Institutes of Health grant R01CA261995 (N.S.). National Institutes of Health grant R01CA172382 (N.S.). National Institutes of Health grant R01CA249279 (S.H., N.S.). National Institutes of Health grant R35 GM151905 (K.D.M., F.P.G.). National Science Foundation Grant No. 1937963 (K.D.M.). National Institutes of Health grant R35 GM151876 (T.Y.H., G.I.L.). National Institutes of Health grant R01GM086596 (R.J.A.)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Z.Z., N.S. Methodology: Z.Z., Y.M.C., M.A., Y.D., K.D.M., E.R., G.I.L., F.P.G., R.J.A., N.S. Investigation: Z.Z., Y.M.C., M.A., Y.D., K.D.M., E.R., S.S., J.L., X.L., E.M.G., C.Z., J.S., R.A.B., T.Y.H., G.I.L., F.P.G., R.J.A., N.S. Visualization: Z.Z., Y.M.C., M.A., Y.D., E.R., E.M.G., N.S. Writing–original draft: Z.Z., N.S. Writing–review & editing: Z.Z., Y.M.C., M.A., Y.D., K.D.M., E.R., S.S., J.L., X.L., E.M.G., C.Z., J.S., R.A.B., T.Y.H., G.I.L., F.P.G., R.J.A., N.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Matti Poutanen, Karl-Heinz Storbeck, Maria Parr, and Neelanjan Mukherjeet for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Z., Chung, YM., Alyamani, M. et al. A bypass gateway from cholesterol to sex steroid biosynthesis circumnavigates CYP17A1. Nat Commun 16, 10611 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66558-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66558-2