Abstract

Patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR + )/HER2- breast cancer may benefit from neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) plus chemotherapy. The effect of chemotherapy or ICI run-in before combination therapy in this population is unexplored. In this randomized pilot trial, patients with HR + /HER2- breast cancer received two weeks of neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel or pembrolizumab, with baseline and post-run-in tumor biopsy, followed by combined nab-paclitaxel/pembrolizumab. The primary endpoint was PD-L1 expression change between biopsies. Tumor whole exome/RNA sequencing were performed. Of 29 patients, 72% were node-positive. Residual cancer burden (RCB) 0-1 rate was 28% (inclusive of patients receiving additional neoadjuvant adriamycin/cyclophosphamide). No significant change in PD-L1 expression occurred following nab-paclitaxel or pembrolizumab run-in, thus the primary endpoint was not met. Other secondary outcome measures included overall response rate of 80% to the neoadjuvant regimen, and 3-year event-free survival of 86% (95% CI 69-100%); there were no unexpected safety signals. In exploratory biomarker analyses, higher baseline PD-L1 expression and inflammatory gene signatures were associated with favorable response (RCB 0-1); higher expression of estrogen response genes, with unfavorable response (RCB 2-3). Clinical Trial Number: NCT02999477

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative (HR + /HER2-) breast cancer comprises approximately 60-70% of invasive breast cancer cases1. Compared to other breast cancer subtypes, it is poorly immunogenic, with lower levels of Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression2, fewer tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)3,4, and lower tumor mutational burden (TMB)5,6. These features suggest that immunotherapy may not be an optimal treatment approach.

Nevertheless, data from several randomized trials have suggested that a subset of patients with early-stage HR + /HER2- breast cancer may benefit from an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) in combination with chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting. The randomized phase II I-SPY2 trial revealed an average pathologic complete response (pCR) rate of 30% in HR + /HER2- patients with breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy, compared with 13% among patients treated with chemotherapy alone7. The pCR rate in the pembrolizumab-containing treatment arm varied by molecular subtype, reaching 69% in patients with basal-type or immune-enriched tumors8. In the phase III KEYNOTE-756 trial, patients with high-risk, high grade, early-stage HR + /HER2- breast cancer were randomized to receive chemotherapy plus or minus pembrolizumab9. The pCR rate was significantly higher on the pembrolizumab arm (24.3% versus 15.6%; p < 0.01). Finally, in the CheckMate 7FL randomized phase III trial, a similar patient population with high-risk early-stage HR + /HER2- breast cancer were randomized to receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus or minus nivolumab. Results demonstrated a significantly higher pCR rate of 24.5% with nivolumab (versus 13.8% with placebo)10.

Despite these positive pCR endpoint results in HR + /HER2- breast cancer, many questions remain regarding patient selection for ICIs in the neoadjuvant setting. Notably, in the randomized phase II GeparNuevo trial, patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer were randomized to receive neoadjuvant durvalumab or placebo plus chemotherapy. A subset of patients received a two-week window of durvalumab monotherapy or placebo before starting chemotherapy (with or without durvalumab). Among patients in the window cohort, the pCR rate was significantly higher for those who received run-in durvalumab versus placebo11. These findings suggest that the order of administration of chemotherapy versus ICI may be important in the neoadjuvant setting. However, this has not been investigated in patients with HR + /HER2- breast cancer.

In this work, to explore the efficacy of chemotherapy plus ICI and understand the biological impacts of an initial chemotherapy versus ICI monotherapy run-in, we conducted a prospective study of neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel with pembrolizumab in patients with stage II and III HR + /HER2- breast cancer. Participants were randomized 1:1 to receive a two-week window of either nab-paclitaxel or pembrolizumab, with pre- and post-window breast biopsies. Subsequently, all participants received a combination of neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel and pembrolizumab, followed by assessment of response at surgery. The primary hypothesis of the trial was that we would observe a significant increase in PD-L1 expression following initial window treatment with either nab-paclitaxel or pembrolizumab. This hypothesis was based on the premise that either chemotherapy or ICI run-in may enhance anti-tumor immune activity12,13,14, thereby priming the tumor microenvironment to respond more favorably to the combination regimen.

Results

Patients enrolled and treatment received

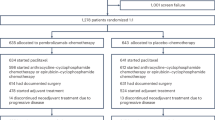

A total of 32 patients were enrolled between June 2, 2017 and March 9, 2022. The trial was originally designed to enroll 50 patients but was closed early due to slow accrual. Two patients withdrew before receiving study therapy and one was found to be ineligible due to HER2-positivity after receiving one dose of pembrolizumab. The remaining 29 patients were included in the efficacy analyses, and all 30 patients who received at least one dose of study therapy were included in the safety analyses (Fig. 1A shows trial schema and biospecimen collection timepoints/analyses; Supplementary Fig. 1 shows CONSORT diagram).

On all plots, baseline timepoint is prior to initiation of neoadjuvant therapy; week 3 day 1 (W3D1) timepoint follows run-in of nab-paclitaxel monotherapy (Arm A) or pembrolizumab monotherapy (Arm B); week 7 day 1 (W7D1) timepoint follows combination therapy with nab-paclitaxel plus pembrolizumab. Of note, many biopsies at W7D1 were inevaluable due to insufficient tumor presence, therefore evaluable results from that timepoint may be biased toward a population of less favorable responders. A Trial schema and biospecimen collection detail. B PD-L1 CPS distribution across all timepoints measured. Numbers in the middle of each plot show median (range) of PD-L1 CPS at each timepoint. The boxes range from quartile 1 to quartile 3 (Q1 to Q3) with a line at the median, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme points within 1.5 × interquartile range (IQR) from the box edges. Individual values outside the whiskers are considered outliers. C Changes in PD-L1 CPS over time, by patient; only patients with at least two consecutive timepoints measured are shown. D TILs distribution across all timepoints measured. Numbers in the middle of each plot show median (range) of TILs at each timepoint. The boxes range from quartile 1 to quartile 3 (Q1 to Q3) with a line at the median, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme points within 1.5 × interquartile range (IQR) from the box edges. Individual values outside the whiskers are considered outliers. E Changes in TILs over time, by patient; only patients with at least two consecutive timepoints measured are shown. IHC immunohistochemistry, TILs tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, WES whole exome sequencing, RNAseq whole transcriptome sequencing, PD-L1 Programmed death-ligand 1, CPS Combined Positive Score.

The baseline patient and disease characteristics among all 29 patients in the efficacy analyses are shown in Table 1. The median age was 42 years old (range: 31 to 70). 69% of patients had clinical stage II breast cancer, 72% had clinically node-positive breast cancer, 48% had grade 2 tumors, 41% had grade 3 tumors, and 76% of tumors had pure ductal histology. 17% of tumors (5/29) were categorized as HR low-positive (HR low + ; see definition in Table 1); the remainder were HR+.

Among the 29 patients in the efficacy analysis, 20 (55%) received all 12 planned doses of neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel, and an additional 5 patients (17%) received 10-11 doses of neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel. Reasons for early discontinuation were toxicity (8 patients) and physician decision (1 patient). 48% of patients received all 5 planned doses of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab, with reasons for early discontinuation being toxicity (12 patients) and physician decision (3 patients; Supplementary Table 1). Additional non-protocol neoadjuvant therapy, which was allowed in case of incomplete clinical response to nab-paclitaxel plus pembrolizumab, was administered to 15 patients (52%), all of whom received 4 cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC; one with ongoing pembrolizumab; Table 1).

PD-L1 and TILs: landscape and correlation with treatment response

The primary objective of the protocol was to characterize changes in PD-L1 expression after treatment with either nab-paclitaxel (Arm A) or pembrolizumab (Arm B) monotherapy, i.e., to evaluate changes in PD-L1 levels between breast biopsy tissue at baseline and at week 3 day 1 (W3D1). It was pre-specified that PD-L1 expression for the primary endpoint evaluation would be measured by tumor cell H-score, since measures such as PD-L1 Combined Positive Score (CPS) did not exist at the time of trial design. The trial hypothesis was that both nab-paclitaxel and pembrolizumab monotherapy would cause an increase in PD-L1 expression. Twenty-three patients had evaluable PD-L1 scoring at baseline and W3D1 and were therefore included in the primary endpoint calculation (the remaining patients had insufficient and/or unpaired tissue). There was no significant change in PD-L1 tumor cell H-score between baseline and W3D1, in either Arm A (chemotherapy first) or Arm B (immunotherapy first), considering H-score as both a binary and a continuous variable. Specifically, all patients were PD-L1 negative by H-score (H-score <100) at baseline. At W3D1, one patient (4%; this was a patient in Arm A) had converted to PD-L1 positive (H-score ≥100; p = 1.00 in both Arm A and Arm B for change in PD-L1 H-score by McNemar’s test) (Supplementary Table 3). Using PD-L1 CPS in the same calculations, there was again no significant change in PD-L1 between baseline and W3D1 in either arm, or in the overall trial population (Supplementary Table 4).

PD-L1 CPS and stromal TILs were evaluated on baseline breast biopsies, on-treatment breast biopsies at multiple timepoints (following monotherapy run-in and following combination therapy), and on surgical tissue in patients with residual disease (Fig. 1B, D). At baseline, median PD-L1 CPS was 1 (range 0–100), and median TILs were 7.5% (range 1–90%). Of 26 patients with baseline tissue evaluable for these biomarkers, 18/26 (69%) patients had baseline PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1, 7/26 (27%) patients had baseline PD-L1 CPS ≥ 10, and 13/26 (50%) patients had baseline TILs ≥10%.

Changes in PD-L1 staining and TIL levels across neoadjuvant timepoints for each evaluable patient are depicted in Fig. 1C, E. There were no obvious visual patterns of change in either biomarker over the course of therapy, with levels starting and remaining low in most patients, though substantial increases and decreases in both PD-L1 and TILs were seen in some patients.

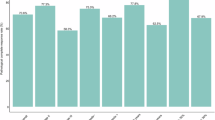

Figure 2 shows pCR rates according to baseline PD-L1 CPS. In the overall population, pCR rate was 0% (0/8 patients) among patients with baseline CPS < 1, 28% (5/18 patients) among patients with baseline CPS ≥ 1, and 43% (3/7 patients) among patients with baseline CPS ≥ 10. Histologic and biomarker characteristics of the five patients who experienced pCR on trial are shown in Supplementary Table 5. Three pCR patients were evaluable for BluePrint and MammaPrint (estimating risk of distant recurrence) signatures; all three were basal (BluePrint) and High2 (MammaPrint).

A pCR rate according to PD-L1 CPS, using CPS cut-off of <1 (negative) vs >/=1 (positive). B pCR rate according to PD-L1 CPS, using CPS cut-off of <10 (negative) vs >/=10 (positive). In both panels, results are shown for the overall population (black column, n = 26 patients evaluable for PD-L1 CPS on baseline tissue) and for patients who did not (red column) versus who did (green column) receive neoadjuvant AC. AC was administered to patients with incomplete clinical response to neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel plus pembrolizumab per physician discretion. Only the 26 patients evaluable for baseline PD-L1 CPS are shown in both panels. AC Adriamycin + cyclophosphamide, PD-L1 Programmed death-ligand 1, CPS Combined Positive Score.

Efficacy

Evaluation of pCR rate, overall response rate, and event-free survival were secondary objectives. pCR was experienced by 5/29 (17%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 8–35%) of participants overall, including 3/14 patients (21%, 95% CI 8–48%) who received nab-paclitaxel plus pembrolizumab only, and 2/15 patients (13%, 95% CI 4–38%%) who received additional neoadjuvant AC (which was administered in case of incomplete clinical response to nab-paclitaxel plus pembrolizumab). Comparing patients treated on Arm A (chemotherapy first) versus arm B (immunotherapy first), there were no evident numerical differences between pCR rates or residual cancer burden (RCB) score distribution, and the proportion of patients by arm who received additional neoadjuvant AC was approximately equivalent (Table 2).

Fifteen patients across both arms were evaluable for RECIST response to the nab-paclitaxel plus pembrolizumab portion of neoadjuvant therapy, based on breast magnetic resonance imaging. Overall radiographic response rate to nab-paclitaxel plus pembrolizumab was 80% (20% complete response, 60% partial response), and no patients experienced progressive disease by RECIST during nab-paclitaxel plus pembrolizumab (Supplementary Table 2).

Median follow-up was 36.1 months. Three-year event-free survival was 86% (95% CI 69-100%) and 3-year overall survival was 93% (95% CI 80-100%). One patient died due to breast cancer.

Safety and tolerability

Evaluation of safety and tolerability was a secondary objectives. Among 30 patients who received at least one dose of study therapy, treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) of grade 2 or higher occurred in 97% of patients, and 50% of patients experienced at least one TRAE of grade 3 or higher (Table 3). There were no grade 5 AEs. TRAEs of any grade that occurred in ≥20% of patients were peripheral sensory neuropathy (50% of patients), alopecia (33%), diarrhea (30%), neutrophil count decreased (27%), and fatigue (23%), reflecting known toxicities of nab-paclitaxel. The most common immune-related AE was hypothyroidism (in 4 patients, 13%). Grade 3-4 immune-related AEs occurred in 4 patients: pneumonitis (1 patient, grade 4), colitis (2 patients, both grade 3), and alanine aminotransferase increase (1 patient, grade 3). There were no evident differences in toxicity according to treatment arm. A comprehensive listing of all TRAEs, in the overall study population and broken down by arm, is in Supplementary Data 1.

Genomic landscape of the trial population

Further biomarker objectives were exploratory. 28 patients had a baseline breast biopsy available for whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq). The baseline genomic features of the cohort are summarized in Fig. 3. Individual tumor WES and RNA-Seq data characteristics are detailed in the Supplementary Data Files (Supplementary Data 2 and 3). The most commonly altered individual gene (considering nonsynonymous mutations and indels) was TP53 (12/28 patients, 43%). Common HR+ breast cancer genes GATA3 and PIK3CA were altered in 5/28 (18%) and 4/28 (14%) of patients, respectively. For 14 patients, RNA expression analyses for the MammaPrint and BluePrint signatures were performed at Agendia, Inc, showing 7/14 (50%) luminal B type, 5/14 (36%) basal type, and 2/14 (14%) luminal A type.

Genomic overview of all baseline breast biopsy samples. Each column represents a single biospecimen. Tumors are ordered by RCB response and treatment arm. Nonsynonymous mutational burden is subdivided into clonal (purple) and subclonal (pink) mutational load. Mutational signatures indicate proportion of detected mutational signatures present in the tumor. The only mutational signatures shown on the figure are those observed as dominant in at least one patient. HR status considered positive if ER or PR > 10%. Otherwise, considered HR low-positive. Tumor type represents molecular subtype evaluated by BluePrint plus MammaPrint RNA expression signatures. Somatic mutations in genes commonly mutated in breast cancer are shown for each tumor and are ordered by their mutation frequency; the top 15 most frequently mutated genes in the cohort are shown. Source data provided in Supplementary Data file 2. HR hormone receptor, RCB residual cancer burden, APOBEC apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide, DSB double-strand breaks, ER estrogen receptor, PR progesterone receptor, WES whole exome sequencing, TMB tumor mutational burden.

Genomic features associated with treatment response and resistance in the overall population

To identify genomic features associated with treatment response assessed at surgery, we considered patients with evaluable genomic data and known RCB response on trial, comparing patients with favorable response (RCB 0-I; n = 6 patients) to those with unfavorable response (RCB II-III; n = 20 patients). Of note, this analysis included patients treated with neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel and pembrolizumab, both with and without neoadjuvant AC. When we excluded patients who received neoadjuvant AC, the top pathways enriched among favorable responders remained consistent with those identified when considering all patients.

We first investigated the association between features of the tumor whole exome and treatment response. In an unbiased analysis, no single-gene nonsynonymous somatic variant was associated with response, which was unsurprising in this small and therefore underpowered cohort. Likewise, there was no significant association between TMB, tumor purity, tumor ploidy, or tumor heterogeneity and response (Supplementary Fig. 2).

We used gene set and gene signature analysis to identify key biological programs associated with favorable treatment response. Using the Enricher15 program investigating 50 Hallmark oncology genesets, we found that four gene sets (interferon alpha response, interferon gamma response, allograft rejection, and TNF-alpha signaling via NF-kB) were significantly enriched in patients with favorable response in the overall population (Fig. 4A). Follow-up single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA), which was performed considering only genes in the four hallmark genesets associated with favorable response in the overall population, similarly showed enrichment of individual genes in the allograft rejection, TNF-alpha signaling via NF-kB, and interferon gamma response signatures among patients with favorable response (Fig. 4B). This further supports a link between interferon gamma response, allograft rejection, and TNF alpha signaling pathways (recovered via ssGSEA analysis herein) and favorable response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus pembrolizumab in our overall population.

A Gene sets associated with favorable versus unfavorable response in hallmark gene set analysis. The four genesets significantly enriched in favorable responders (RCB 0-I; n = 6 patients) are in green; the two gene sets significantly enriched in unfavorable responders (RCB II-III; n = 19 patients) are in pink. Statistical significance was defined as false discovery rate q values < 0.01. B, C Gene sets associated with favorable versus unfavorable response in ssGSEA analysis. ssGSEA on baseline tumor tissue using a non-parametric MWW test identified three gene sets significantly higher among patients with favorable response (RCB 0-I; n = 6 patients; panel C and two gene sets significantly higher among patients with unfavorable response (RCB II-III; n = 19 patients; panel D. Top row: ssGSEA score (y-axis) by response status. Bottom row: ssGSEA score of the same gene sets by response status and treatment. Unadjusted MWW p-values are above each group. Statistical significance was defined as p-value < 0.05. D Estrogen signaling negatively correlates with antigen presentation and processing. The relationship between estrogen signaling by ssGSEA (y-axis) and antigen processing and presentation by ssGSEA (x-axis) in baseline tumors showed a significant negative correlation (Spearman coefficient -0.41, p = 0.042 by two-sided t-test). E Immune cell types associated with response. CIBERSORT estimated tumor-infiltrating level of CD8 + T cell, M1 Macrophage, and memory CD4 T cells are higher in patients with favorable (RCB 0-I, n = 6 patients) vs. unfavorable (RCB II-III, n = 19 patients) response. Comparisons performed using non-parametric MWW test, with unadjusted p-values. F Cytokine types associated with response. Heatmap of cytokine activity score estimated by CytoSig. Color indicates cytokine score from lowest (blue) to highest (red) activity. Each column is a tumor arranged first by response, then treatment arm. Tumors with favorable response had enrichment for pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL1A and IL1B (significance calculated without multiple testing correction). ICI immune checkpoint inhibitor, RCB residual cancer burden, ssGSEA single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, MWW Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon, ER estrogen receptor. Source data provided in Supplementary Data file 3.

In the converse analysis, we used gene expression data to identify biological programs associated with unfavorable treatment response. The only two Hallmark gene sets significantly enriched in patients with unfavorable response were the estrogen response early and late genesets (Fig. 4A). Follow-up ssGSEA, considering genes in the estrogen response early and estrogen response late genesets, showed that higher levels of estrogen response gene expression were significantly associated with unfavorable response to treatment (Fig. 4C). Prior work by our group16 and others17 demonstrated that diminished antigen presentation could be one of the immune resistance strategies adopted by tumors with a high estrogen signaling level. Therefore, we sought to explore whether decreased antigen processing and presentation may correlate with higher levels of estrogen response genes in this trial cohort, as well. Consistent with this hypothesis, using ssGSEA, we found a negative correlation (Spearman coefficient −0.41, p = 0.04) between estrogen signaling pathway gene expression and antigen processing/presentation gene expression (Fig. 4D). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4D, tumors with a favorable response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus pembrolizumab tended to cluster with an estrogen signaling-low and antigen processing/presentation-high profile.

Immune cells and cytokine activity associated with treatment response in the overall population

We used immune cell deconvolution analysis (CIBERSORT18) of bulk RNA-seq data to identify cell types associated with response to therapy. Of the 22 distinct immune cell types evaluable, higher levels of CD8 + T cells, CD4+ memory activated T cells, and anti-tumor M1-like macrophages were all significantly associated with favorable treatment response (Fig. 4E). This finding suggests that favorably responding tumors harbor higher levels of cytotoxic effector and type-I inflammatory anti-tumor immune infiltrates compared to unfavorable responders.

Forty-three cytokines were evaluated, of which 6 (interleukin-1 [IL-1] alpha and beta, interleukin-27, leukemia inhibitor factor, TNF-alpha, and epidermal growth factor) were significantly associated with favorable treatment response (significance calculated without multiple testing correction in this hypothesis-generating analysis). IL-1 and TNF-alpha are pro-inflammatory cytokines, and IL-27 also has pro-inflammatory functions19, overall suggesting that a pro-inflammatory microenvironment promotes therapy response.

Genomic features associated with treatment response by trial arm

When the population was broken down by treatment arm, the profiles of genesets significantly associated with treatment response differed between the two arms (Supplementary Fig. 3). Likewise, when looking at individual genes within the genesets of interest, individual genes that correlated with favorable versus unfavorable response differed between the two arms (Supplementary Fig. 4). Specifically, genes significantly expressed in favorable responders who received initial run-in with nab-paclitaxel were immune checkpoint, antigen presentation, and cell cycle genes, including IDO1, CD274 (encoding PD-L1), antigen peptide transporters (TAP1/2), MHC class I gene HLA-B and MHC class II gene HLA-DRA expressed by antigen-presenting cells, ICAM1 and CXCL10 (known for regulating leukocyte recruitment from circulation to sites of inflammation), CDKN2A (which promotes blood vessel endothelial cell migration), and IFNG/STAT1, reflecting the enrichment of anti-tumor activities (and nearly all of which are known interferon-responsive transcripts). In contrast, genes significantly expressed in favorable responders who received initial run-in with pembrolizumab were genes primarily expressed in immune cells, such as BANK1, CD40, CD8A, and FGL2. These findings suggest that the immune biology associated with treatment response may differ depending on whether the chemotherapy or the immune checkpoint inhibitor agent is administered first.

The gut microbiome and response to neoadjuvant therapy

The evolution of the gut microbiome during neoadjuvant chemotherapy or checkpoint inhibitor, and features of the microbiome that correlated with response to neoadjuvant therapy, were evaluated. Fecal samples were successfully sequenced at baseline in 17 patients, and following monotherapy with either nab-paclitaxel or pembrolizumab in 18 patients (9 patients per arm). Due to the small number of specimens evaluated for microbiome features in each arm, these results require further validation. Each of three types of microbiome features (bacterial species, pathways, and enzymes) were analyzed for change from the baseline to on-treatment timepoint in each arm. These analyses were not paired by patient. The relative abundance of microbial fatty acid biosynthesis pathways decreased significantly during chemotherapy run-in (Fig. 5A) but not during checkpoint inhibitor run-in (Fig. 5B), indicating that the bacterial capacity to make fatty acids goes down during chemotherapy, but not during immunotherapy. Evidence of other significant changes in the microbiome, including alpha and beta diversity, during chemotherapy or immunotherapy run-in was not identified.

Relative abundances of microbial fatty acid biosynthesis genes at baseline (Timepoint 01; n = 17 patients) versus following monotherapy treatment (Timepoint 02) with nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy (Arm A, n = 9 patients, panel A or pembrolizumab immunotherapy (Arm B, n = 9 patients, panel B. For each metadata variable and/or stratification of the data, every pathway present in the filtered relative abundance table is tested for an association, and raw p-values are adjusted for false discovery across all pathways, using the Benjamini-Hochberg method (q-values). Associations with q < 0.25 are considered significant. C A heatmap showing the microbial pathways (assessed at baseline timepoint, n = 17 patients) significantly associated with RCB (q < 0.25). D Of all microbial pathways assessed, the arginine synthesis pathway was most strongly associated with RCB (RCB 0, n = 3 patients; RCB II, n = 6 patients; RCB III, n = 6 patients). For all box plots, the boxes range from quartile 1 to quartile 3 (Q1 to Q3), with the median value indicated by the line within the box. The whiskers extend to the most extreme points within 1.5 × interquartile range (IQR) from the box edges. Individual values outside the whiskers are considered outliers. RCB residual cancer burden, FDR false discovery rate.

The association between key gut microbial pathways and response to therapy was also evaluated. A number of pathways displaying significant association with RCB were identified and are shown in Fig. 5C. Many of these pathways relate to nucleotide synthesis. The arginine synthesis pathway displayed the highest absolute value coefficient of correlation with RCB (Fig. 5D), with lower levels of gut microbiome arginine synthesis genes corresponding to more favorable RCB scores. There was no correlation between overall alpha or beta diversity and RCB score, indicating that RCB status was not associated with changes in the complexity of the microbial community or overall changes in microbiome composition.

Discussion

In the present study, the combination of neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel (followed by neoadjuvant AC in some cases) yielded a pCR rate of 17% among patients with early-stage HR + /HER2- breast cancer. While the regimen was overall tolerable and common toxicities mirrored those seen typically with nab-paclitaxel, 4/30 patients (13%) experienced a grade 3-4 immune-related adverse event, and just over half of patients discontinued neoadjuvant pembrolizumab early, mostly for toxicity.

Serial on-treatment assessment of PD-L1 and TILs did not reveal significant changes in either biomarker following treatment with nab-paclitaxel, pembrolizumab, or the combination. There were many baseline features that correlated with favorable response to the neoadjuvant regimen, including higher PD-L1 CPS and multiple pro-inflammatory immune gene signatures and cell types. The only significant gene expression predictor of unfavorable response to the neoadjuvant regimen was higher estrogen signaling.

Our cohort’s pCR rate is somewhat lower than the pCR rates recently reported from randomized phase III trials of neoadjuvant ICIs plus chemotherapy in patients with HR + /HER2- breast cancer. In the randomized phase III KEYNOTE-756 trial, the pCR rate was 24.3% among patients treated with neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy20. In the CheckMate 7FL trial, the pCR rate was 24.5% among patients randomized to receive neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy21. However, all patients on those trials received anthracycline plus taxane chemotherapy, whereas only half of the patients in this trial received neoadjuvant anthracycline. Moreover, the phase III trials almost exclusively enrolled patients with grade III disease, whereas grade III patients only accounted for 41% of participants on our trial. In prior studies, high tumor grade has been associated with improved pCR rates22,23,24,25. We also enrolled 14% of patients with pure lobular histology, who were excluded from the larger phase III trials.

The prevalence of PD-L1 positivity in our patient cohort was comparable to the KEYNOTE-756 and CheckMate 7FL trial populations. At baseline, 40.1% of patients in KEYNOTE-756 had PD-L1 CPS ≥ 10, as determined using the 22C3 antibody20. In CheckMate 7FL, 18% of patients had PD-L1 CPS ≥ 10, as determined using the 28-8 antibody21. In our study, 7/26 evaluable patients (27%) had baseline PD-L1 CPS ≥ 10 by 22C3. We found that pCR rates increased numerically with increasing PD-L1 CPS, with pCR rates of 0%, 28%, and 43% for patients with baseline PD-L1 CPS of <1, ≥1, and ≥10, respectively. This is in agreement with the randomized phase III KEYNOTE-756 and CheckMate 7FL trials, in which pCR rates correlated with baseline PD-L1 expression, regardless of whether ICI was used20,21.

Our molecular findings mirror predictors of clinical benefit to chemotherapy plus ICI in metastatic HR + /HER2- breast cancer patients. In a randomized phase II trial of eribulin with or without pembrolizumab for patients with HR + /HER2- metastatic breast cancer (which showed no benefit to adding pembrolizumab, in the overall population)26,27, patients who benefitted from the combination had tumors enriched for gene signatures of immune infiltration, allograft rejection, inflammatory response, and interferon-gamma, interferon-alpha, and IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling pathways. In contrast, estrogen signaling and tumor heterogeneity were associated with resistance27. Similarly, patients in the present study who had favorable response to the combination of pembrolizumab with nab-paclitaxel had evidence of immune activation present at baseline: enrichment of allograft rejection, interferon alpha/gamma, and TNF-alpha signaling gene signatures, and enrichment of inflammatory immune cells such as CD8 + T cells and anti-tumor M1-like macrophages. In contrast, patients with unfavorable response to the combination had increased expression of estrogen response early and late genes, which correlated with decreased expression of genes involved in antigen processing and presentation. Taken together, these findings suggest that similar features may be associated with response and resistance to ICIs with chemotherapy in the early-stage and metastatic settings. Particularly, we hypothesize that highly estrogen-driven tumors may downregulate expression of antigen processing and presentation to escape immune-mediated destruction. This is supported by other data showing a negative association between estrogen receptor and HLA gene expression28. Overall, there is evidence of complex interplay between estrogen signaling and both innate and adaptive immunity, and many mechanisms by which estrogen signaling could impact response to ICI-containing regimens29.

In the GeparNuevo trial, improvement in pCR rates with durvalumab added to chemotherapy was observed only among patients who received an initial run-in with durvalumab as a single agent11. This raised the intriguing possibility that specific sequencing of chemotherapy and ICI may impact the clinical efficacy of combination regimens. Furthermore, while results from GeparNuevo (which compared neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus ICI to neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone) showed that predictive and prognostic gene sets differed significantly between the ICI and non-ICI arms30, the relationship between gene sets and response to chemotherapy plus ICI based on treatment sequencing has not been elucidated. Neoadjuvant ICI has been shown to induce expansion of PD1-expressing T cells in HER2-negative breast cancer (both triple-negative and HR + ), and this effect appears consistent whether tumors are treatment-naïve or chemotherapy-exposed at the time of ICI initiation14. At the same time, chemotherapy is immunogenic in breast cancer12,13, motivating our hypothesis that a chemotherapy run-in could also be biologically beneficial prior to ICI.

Though our trial did not show a difference in pCR rates between the chemotherapy-first and ICI-first arms, we did find that the gene sets and individual genes associated with response differed between the two treatment arms. Among patients treated with nab-paclitaxel first, favorable responders had enrichment of genes involved in immune checkpoints, antigen presentation, and the cell cycle. In the pembrolizumab run-in group, favorable responders had enrichment of genes primarily expressed in immune cells, such as BANK1, CD40, CD8A, and FGL2. These findings support the idea that mechanisms of treatment response may differ depending on whether the chemotherapy or the ICI agent is administered first, and deserve further investigation in other cohorts.

Several studies have suggested that the baseline composition of the intestinal microbiota can affect the response to chemotherapy31,32 and immunotherapy33,34,35,36,37 in solid tumor patients. These effects are likely mediated, at least in part, by the influence of intestinal microorganisms on the immune system. In a mouse sarcoma model, administration of cyclophosphamide compromised the intestinal epithelium. This allowed the translocation of intestinal bacteria into secondary lymphoid organs, where they enhanced the development and proliferation of anti-tumor immune cells38. In mouse models of HR+ breast cancer, antibiotic-mediated induction of intestinal dysbiosis led to increased levels of intratumorally macrophages and inflammatory chemokines, which facilitated dissemination of tumors cells into the circulation39. In our analysis of the gut microbiome, arginine and nucleotide synthesis pathways were the strongest predictors of response to neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel and pembrolizumab, with lower levels of gut microbial arginine biosynthesis genes, and higher levels of nucleotide biosynthesis genes, corresponding to more favorable RCB scores. One potential biochemical explanation for this association is that lower availability of arginine in the host (due to tumor utilization or immune activation)40 causes compensatory nucleotide biosynthesis from the gut microbiome. Arginine deficiency has been previously described in breast cancer cell lines41. The interplay of intestinal microbiota and response to chemo- and immunotherapies in breast cancer remains an area for future research.

This study has several limitations. The sample size was small and not all patients had tissue available for all biomarker assessments. Therefore, in genomic analyses, only six patients were in the favorable response (RCB 0-1) subgroup. In genomic analyses, all patients who received nab-paclitaxel plus immunotherapy were analyzed together, regardless of whether they went on to receive additional neoadjuvant anthracycline. However, sensitivity analyses performed to re-examine key results while excluding patients who received neoadjuvant AC were qualitatively consistent with results of the combined groups. Serial neoadjuvant biopsies (after nab-paclitaxel alone, after pembrolizumab alone, and after the combination) were obtained in all patients and analyzed genomically, including by single-cell RNA technology. These data will offer a unique opportunity to understand the evolution of the tumor and its microenvironment over the course of different neoadjuvant systemic therapies. While those results are not the focus of this manuscript, they have been evaluated in subsequent analyses that incorporate single-cell data alongside the WES and bulk RNA-seq42.

We have presented a detailed analysis of tumor-intrinsic and tumor-extrinsic mechanisms of response and resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus checkpoint inhibition in early-stage HR + /HER2- breast cancer. These results are of high clinical relevance, given multiple recent randomized phase III trials showing improved pCR rates with the addition of neoadjuvant ICI to chemotherapy in this patient population. While long-term follow-up from those trials is still maturing, the results to date suggest that neoadjuvant ICI may become a standard future treatment approach for some HR + /HER2- breast cancer patients. Here we show that more estrogen-driven tumor biology is the major predictor of unfavorable response to neoadjuvant therapy. Conversely, a more inflamed tumor microenvironment predicts more favorable response, as has been shown in many other cohorts. We identify decreased antigen processing and presentation as one biological pathway that may underlie the less-inflamed microenvironment of strongly estrogen-driven tumors. Ongoing work should continue to dissect the immune biology of HR + /HER2- breast cancer, in order to maximize the clinical benefit of immunotherapy approaches in this common patient population.

Methods

Patient population

This was a randomized, open-label study that enrolled patients with non-metastatic breast cancer with a primary tumor 2 cm or greater in diameter, with or without nodal involvement. All participants had HR + /HER2- breast cancer (estrogen receptor ≥1% or progesterone receptor ≥1%, and HER2-negative per 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology / College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) guidelines43). Eligible patients had not received any systemic therapy for their breast cancer, and had not received prior anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in any context. All participants were at least 18 years old, with an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1, and provided written informed consent prior to engaging in any study procedures. The study (NCT02999477) was approved by the institutional review board of Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (DF/HCC), and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The full trial protocol, including statistical analysis plan, is included in Supplementary Note 1. The CONSORT checklist is also included in the Supplementary Information file.

Randomization and Treatment Procedures

Participants were randomized 1:1 to receive an upfront two-week window of nab-paclitaxel (Arm A) or pembrolizumab (Arm B). The random allocation sequence used for randomization was generated by the study statistician, shared independently with the DF/HCC Office of Data Quality, and then implemented via central computer. All study personnel were blinded to the allocation sequence. Patients randomized to Arm A received nab-paclitaxel 125 mg/m2 via intravenous (IV) infusion once per week for two weeks. Patients randomized to Arm B received one dose of pembrolizumab 200 mg via IV infusion. After the two-week window, all patients in Arms A and B received weekly nab-paclitaxel 125 mg/m2 in combination with pembrolizumab 200 mg once every 3 weeks, for a total planned neoadjuvant therapy course of 12 doses of weekly nab-paclitaxel 125 mg/m2 and 5 doses of pembrolizumab 200 mg administered once every 3 weeks for all patients, regardless of arm. Additional neoadjuvant chemotherapy was allowed at investigator discretion in cases of incomplete clinical response to protocol therapy with nab-paclitaxel plus pembrolizumab.

Collection of research biospecimens

All participants underwent a research biopsy of the primary tumor at baseline (within 14 days before the initiation of window monotherapy), just prior to Week 3 Day 1 (W3D1; after the completion of window monotherapy, before the initiation of combination therapy), and just prior to Week 7 Day 1 (W7D1; following 3-4 weeks on combination therapy). Tumor tissue was also collected prior to additional neoadjuvant therapy, for patients who received additional neoadjuvant therapy off-trial (denoted as pre-AC biopsy), and at the time of surgery for research purposes.

Stool samples for analysis of the intestinal microbiome were collected from all patients using home-based kits at the following 3 timepoints: baseline; after 1 week of window monotherapy with either nab-paclitaxel or pembrolizumab; and after exposure to both nab-paclitaxel and pembrolizumab combined (Week 4 Day 1).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and quantification of TILs

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor slides were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for evaluation of stromal TILs according to the guidelines published in 2014 by the International TILs Working Group (where stromal TILs percentage is calculated as the area of the stromal compartment occupied by mononuclear inflammatory cells, over the total stromal area within the borders of the invasive tumor)44. IHC was performed centrally by Discovery Life Sciences on FFPE tumor samples to evaluate expression of PD-L1 using the 22C3 pharmDx test on the Dako/Agilent Autostainer Link 48 IHC staining platform. PD-L1 was quantified by (1) tumor cell H-score, which is the product of the intensity of PD-L1 staining (quantified as 0, 1, 2, or 3, from 0=no staining to 3=strong staining) and the percentage of tumor cells showing positive staining (from 0-100%); and (2) CPS which includes PD-L1 staining on tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating mononuclear inflammatory cells.

Statistical methods

The primary endpoint was the change in tumor cell PD-L1 expression by IHC from the baseline biopsy to the W3D1 biopsy, assessed as a dichotomous variable (H-score ≥ 100 versus 0-99) using an exact McNemar’s test. A key secondary endpoint was the change in PD-L1 expression from the baseline to the W3D1 biopsy as a continuous variable (absolute change in H-score) using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Both tests used a one-sided alpha = 0.05. To achieve 80% power to assess this primary endpoint in each arm (assuming a 20% baseline PD-L1 positivity rate, and 50% post-window PD-L1 positivity rate, and 15% PD-L1 IHC assay failure rate), the trial was originally designed to enroll 50 patients (25 patients per arm) but was closed early due to slow accrual.

Prespecified clinical efficacy endpoints included pCR (defined as RCB 045), overall response rate (ORR) assessed radiographically by RECIST 1.146, and disease-free survival (DFS). The full trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are supplied as an appendix to this manuscript.

Whole exome sequencing (WES) library construction and sequencing

Following similar procedures in our previous study27, an aliquot of genomic DNA (100-250 ng in 50 μL) was used as the input into DNA fragmentation (aka shearing). Shearing was performed acoustically using a Covaris focused-ultrasonicator, targeting 150 bp fragments. Library preparation was carried out using the KAPA HyperPrep Kit with Library Amplification (product KK8504) from KAPA Biosystems and duplex UMI adapters from IDT. Unique 8-base dual index sequences embedded within the p5 and p7 primers (purchased from IDT) were added during the PCR process. Enzymatic clean-ups were performed using Beckman Coulter AMPure XP beads, with elution volumes reduced to 30 μL to maximize library concentration.

Subsequently, quantification was performed using the Invitrogen Quant-It broad-range dsDNA quantification assay kit (Thermo Scientific Catalog: Q33130) with a 1:200 PicoGreen dilution. Each library is then normalized to a concentration of 35 ng/μL using 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. All steps were performed during the library construction. Quantification processes are performed on the Agilent Bravo liquid handling system.

Next, hybridization and capture were conducted using the relevant components of IDT’s XGen hybridization and wash kit, following the manufacturer’s suggested protocol with a few modifications. 12-plex pre-hybridization pools were created by pooling equal volumes of the normalized libraries, Human Cot-1, and IDT XGen blocking oligos. These pre-hybridization pools were then lyophilized using the Biotage SPE-DRY. After lyophilization, custom exome bait from TWIST Biosciences and a hybridization mastermix were added to the lyophilized pool before resuspension. The samples were incubated overnight. Library normalization and hybridization setup were performed on a Hamilton Starlet liquid handling platform, while target capture was carried out on the Agilent Bravo automated platform. Following capture, a PCR was performed to amplify the captured material.

Then, the library pools were quantified using qPCR (automated assay on the Agilent Bravo) with a kit from KAPA Biosystems that includes probes specific to the ends of the adapters. Based on the qPCR quantification results, the pools were normalized using a Hamilton Starlet to the required loading concentration. Up to 24 samples were sequenced per lane on Illumina’s NovaSeq S4 sequencing technology.

Cluster amplification of library pools was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina) using Exclusion Amplification cluster chemistry and NovaSeq S4 flowcells. Flowcells were sequenced on Sequencing-by-Synthesis chemistry for NovaSeq S4 flowcells using paired 151 bp runs.

Whole exome sequences (WES) data analysis

WES were captured using Illumina technology. The sequence data processing and analysis were performed using Picard and GATK pipelines on Terra (https://terra.bio/). The Picard pipeline (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) produced a BAM file with aligned reads. This includes aligning the GRCh37 human reference sequence using BWA and estimating and recalibrating the base quality score with the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK)47,48,49. Somatic alterations for tumor samples were called using a customized version of the Getz Lab CGA WES Characterization pipeline developed at the Broad Institute. Briefly, the MuTect v1.1.6 algorithm50 was used to identify somatic mutations. Somatic mutation calls were filtered using a panel of normals (PoN) which was generated by combining normals samples from TCGA51 and the trial cohort. Then oxoG filter, and an FFPE filter, was used to remove artifacts introduced during the sequencing or formalin fixation process. Small somatic insertions and deletions were detected using the Strelka algorithm52. Somatic mutations were annotated using Oncotator53. Recurrently altered mutations were identified using MutSig2CV54. Mutation burden was calculated as the total number of mutations (non-synonymous) detected for a given sample divided by the total genomic target region length captured with appropriate coverage from whole exome sequencing. Tumor heterogeneity was defined as the proportion of mutations in each sample that were inferred to be subclonal. As per our prior work27, subclonal mutations were identified as those having a cancer cell fraction <0.8. Using the validated COSMIC version 3.4 signatures, the python package SigProfilerAssignment55 was applied to identify mutational signatures of individual tumor samples. To define somatic copy ratio profiles, we used GATK CNV. To generate allele-specific copy number profiles and assess tumor purity and ploidy, we used ABSOLUTE56 and FACETS57. Final segmentation calls were taken from ABSOLUTE, except for the X chromosome, which was taken from FACETS. We utilized GISTIC2.058 to identify significantly recurrent amplification and deletion peaks. We assessed the absolute allelic copy numbers of the segment containing each gene to determine allele-specific copy number alterations.

WES data quality control

All 88 samples have successfully completed the whole exome library construction and sequencing. DeTiN59 was applied to samples to estimate the amount of tumor contamination in the normal samples; samples with TiN (tumor in normal) > 0.3 were excluded. The contEst and CalculateContamination from the GATK pipeline47,48,49 were applied to measure the cross-sample contamination in samples, and samples with contamination >0.04 were excluded. Based on these thresholds, no sample was excluded (Supplementary Fig. 5A). A table of samples with quality control metrics for each sample can be found in the Supplementary Data (Supplementary Data 2).

RNA-Seq copy DNA (cDNA) library construction and sequencing

Total RNA was assessed for quality using the Caliper LabChip GX2. The software calculated the percentage of fragments with a size greater than 200nt (DV200). Next, we followed the procedures as previously described60. Briefly, an aliquot of 200 ng of RNA was used as the input for first-strand cDNA synthesis with Illumina’s TruSeq RNA Access Library Prep Kit. This was followed by the synthesis of the second strand of cDNA and indexed adapter ligation. Subsequent PCR amplification enriched the adapted fragments. The amplified libraries were quantified using an automated PicoGreen assay. Each cDNA library, excluding controls, was combined into 4-plex pools with 200 ng of each. Capture probes targeting the exome were added and hybridized for the recommended duration. Following hybridization, streptavidin magnetic beads were used to capture the library-bound probes. Two wash steps were performed to remove any nonspecifically bound products. This hybridization, capture, and wash process was repeated to ensure high specificity. A second round of amplification enriched the captured libraries. After enrichment, the libraries were quantified using qPCR with the KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina Sequencing Platforms and then pooled equimolarly. The entire process was conducted in a 96-well format, with all pipetting performed by Agilent Bravo or Hamilton Starlet.

The pooled libraries were normalized to 2 nM and denatured using 0.1 N NaOH before sequencing. Flow cell cluster amplification and sequencing were carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocols using HiSeq 2000 or 2500. Each run consisted of 76 bp paired-end reads with an eight-base index barcode read. Data were analyzed using the Broad Picard Pipeline, which included de-multiplexing and aggregation.

RNA-Seq data quality control and analysis

Of 88 available samples, two failed at library construction. RSeQC61,62 was applied to the RNA-Seq data to measure the transcript integrity number (TIN) which assesses RNA degradation. Based on the prior cross-site concordance study63, samples with a median TIN of less than 50 and DV200 of less than 25% were excluded. Fortunately, samples with successful library construction and sequencing all passed the pre-defined thresholds (Supplementary Fig. 5B). A table of samples with quality control metrics for each sample can be found in the Supplementary Data (Supplementary Data 2).

The differential gene expression (DEG) analysis was performed using the DESseq264 method, including all expressed genes. No batch variable was included in the DEG analysis, as no significant bias from the sequencing batch was observed (Supplementary Fig. 5C). Gene pathway expression was evaluated with GSEApy65 using the 50 hallmark gene sets from the Molecular Signature Database66 on detected DEGs with false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P value < 0.05. Also, the ssGSEA function from the GSEApy python package was performed to generate nonparametric hallmark gene set scores for individual samples. Tumor immune cell composition was determined with the TIMER267, inputting the log-transformed RNA-seq TPM matrix from the cohort. We applied the CytoSig68 to the log-transformed RNA-seq TPM value to estimate the cytokine stimulation level per sample.

Statistical analysis of genomic data

Continuous molecular variables were compared between favorable responders and unfavorable responders using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon (MWW) test with the Python stats.mannwhtneyu function from scipy package. The association between the gene mutation and status and response was computed by logistic regression with purity as a covariable.

MammaPrint and BluePrint signatures

The MammaPrint 70-gene signature (which produces a result of high or low risk of distant recurrence)69 and BluePrint 80-gene signature (which classifies tumors as Luminal-type, HER2-type, or Basal-type)70 were performed at Agendia, Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA) on RNA extracted from FFPE tumor tissue. Luminal-type tumors were sub-classified as Luminal A (Luminal-type plus MammaPrint low risk) or Luminal B (Luminal-type plus MammaPrint high risk).

DNA and RNA sequencing of intestinal microbiota from stool samples

DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing were performed by the Sequencing and Analysis Core at Baylor College of Medicine. Stool DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing libraries were constructed using NEBnext Ultra II FS library kits, and 2 ×150 bp paired-end sequencing was performed using a NovSeq. Sequencing reads were processed using the bioBakery meta’omics workflow71 following the standard pipeline with default parameters. Briefly, this comprised three fundamental steps: 1) KneadData v0.12.0 for read-level quality control (removal of human reads and trimming of low-quality reads); 2) taxonomic profiling using MetaPhlAn v4.0.372; 3) functional potential profiling with HUMAnN v3.6.1. Statistical analyses were performed in the R 4.3.0 environment. In particular, vegan https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan} was used for ecological diversity measurements, tests, and visualizations and MaAsLin273 was used for linear modeling frameworks. Among each of the comparison types generated, multiple comparisons are adjusted using a Benjamini and Hochberg procedure using the p.adjust function in R, and FDR adjusted p-values of 0.25 or lower are reported as significant, following the MaAsLin2 default parameters.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Individual de-identified participant data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request, to be used for research purposes, for as long as is necessary to address research questions. The data are not publicly available in order to protect patient privacy. All sequencing data (WES and RNAseq) are deposited in dbGaP (accession # phs002419.v2; https://dbgap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/beta/study/phs002419.v2.p1/) and can be obtained by requesting authorized access on dbGaP. Source data, including all PD-L1 and TILs scoring, and full study protocol including statistical analysis plan, are also provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Preprocessing and analytic steps can be found on the Github repository: https://github.com/jingxinfu/primary_hr_brca_io_treated_genomic_analysis. The Zenodo link for code is: https://zenodo.org/records/17398655. The DOI is: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17398655.

References

Howlader, N. et al. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst 106 https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju055 (2014).

Muenst, S. et al. Expression of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) is associated with poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 146, 15–24 (2014).

Denkert, C. et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: a pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol. 19, 40–50 (2018).

Stanton, S. E., Adams, S. & Disis, M. L. Variation in the incidence and magnitude of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer subtypes: A Systematic Review. JAMA Oncol. 2, 1354–1360 (2016).

Xu, J. et al. Elevated tumor mutation burden and immunogenic activity in patients with hormone receptor-negative or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 18, 449–455 (2019).

Barroso-Sousa, R. et al. Prevalence and mutational determinants of high tumor mutation burden in breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 31, 387–394 (2020).

Nanda, R. et al. Effect of pembrolizumab plus neoadjuvant chemotherapy on pathologic complete response in women with early-stage breast cancer: An analysis of the ongoing phase 2 adaptively randomized I-SPY2 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 6, 676–684 (2020).

Huppert, L. A. et al. Pathologic complete response (pCR) rates for HR+/HER2- breast cancer by molecular subtype in the I-SPY2 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 504–504 (2022).

Cardoso, F. et al. KEYNOTE-756: Randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study of pembrolizumab vs placebo combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant endocrine therapy for high-risk, early-stage estrogen receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative (ER+/HER2−) breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, TPS601–TPS601 (2019).

Loi, S. et al. A phase III trial of nivolumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant endocrine therapy in ER+/HER2- primary breast cancer: CheckMate 7FL. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, TPS604–TPS604 (2020).

Loibl, S. et al. A randomised phase II study investigating durvalumab in addition to an anthracycline taxane-based neoadjuvant therapy in early triple-negative breast cancer: clinical results and biomarker analysis of GeparNuevo study. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1279–1288 (2019).

Carson, W. E. et al. Cellular immunity in breast cancer patients completing taxane treatment. Clin. Cancer Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 10, 3401–3409 (2004).

Zitvogel, L., Galluzzi, L., Smyth, M. J. & Kroemer, G. Mechanism of action of conventional and targeted anticancer therapies: reinstating immunosurveillance. Immunity 39, 74–88 (2013).

Bassez, A. et al. A single-cell map of intratumoral changes during anti-PD1 treatment of patients with breast cancer. Nat. Med 27, 820–832 (2021).

Xie, Z. et al. Gene set knowledge discovery with Enrichr. Curr. Protoc. 1, e90 (2021).

Keenan, T. E., Burke, K. P. & Van Allen, E. M. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Med 25, 389–402 (2019).

Mostafa, A. A. et al. Activation of ERα signaling differentially modulates IFN-γ induced HLA-class II expression in breast cancer cells. PLoS one 9, e87377 (2014).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 12, 453–457 (2015).

Kim, D. et al. Cutting edge: IL-27 attenuates autoimmune neuroinflammation via regulatory T Cell/Lag3–dependent but IL-10–independent mechanisms in vivo. J. Immunol. 202, 1680–1685 (2019).

Cardoso, F. et al. Pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in high-risk, early-stage, ER(+)/HER2(-) breast cancer: a randomized phase 3 trial. Nat. Med 31, 442–448 (2025).

Loi, S. et al. Abstract GS01-01: Biomarker results in high-risk estrogen receptor positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative primary breast cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy ± nivolumab: An exploratory analysis of checkmate 7FL. Cancer Res. 84, GS01-01–GS01-01 (2024).

Liedtke, C. et al. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 1275–1281 (2008).

von Minckwitz, G. et al. Impact of treatment characteristics on response of different breast cancer phenotypes: pooled analysis of the German neo-adjuvant chemotherapy trials. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 125, 145–156 (2011).

Baron, P. et al. Impact of tumor size on probability of pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 23, 1522–1529 (2016).

Goorts, B. et al. Clinical tumor stage is the most important predictor of pathological complete response rate after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 163, 83–91 (2017).

Tolaney, S. M. et al. Effect of eribulin with or without pembrolizumab on progression-free survival for patients with hormone receptor-positive, ERBB2-negative metastatic breast cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 6, 1598–1605 (2020).

Keenan, T. E. et al. Molecular correlates of response to eribulin and pembrolizumab in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 12, 5563 (2021).

Lee, H. J. et al. Differential expression of major histocompatibility complex class I in subtypes of breast cancer is associated with estrogen receptor and interferon signaling. Oncotarget 7 (2016).

Corti, C. et al. Estrogen signaling in early-stage breast cancer: Impact on neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 132, 102852 (2025).

Denkert, C. et al. Molecular adaptation to neoadjuvant immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Rep. Med 5, 101825 (2024).

Iida, N. et al. Overuse of antianaerobic drug is associated with poor postchemotherapy prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J. Cancer 145, 2701–2711 (2019).

Zhao, Z. et al. Metagenome association study of the gut microbiome revealed biomarkers linked to chemotherapy outcomes in locally advanced and advanced lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 12, 66–78 (2021).

Matson, V. et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 359, 104–108 (2018).

Routy, B. et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 359, 91–97 (2018).

Gopalakrishnan, V. et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 359, 97–103 (2018).

Chaput, N. et al. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Ann. Oncol. 28, 1368–1379 (2017).

Zheng, Y. et al. Gut microbiome affects the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 7, 193 (2019).

Daillere, R. et al. Enterococcus hirae and barnesiella intestinihominis facilitate cyclophosphamide-induced therapeutic immunomodulatory effects. Immunity 45, 931–943 (2016).

Buchta Rosean, C. et al. Preexisting commensal dysbiosis is a host-intrinsic regulator of tissue inflammation and tumor cell dissemination in hormone receptor–positive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 79, 3662–3675 (2019).

Nüse, B., Holland, T., Rauh, M., Gerlach, R. G. & Mattner, J. L-arginine metabolism as pivotal interface of mutual host-microbe interactions in the gut. Gut Microbes 15, 2222961 (2023).

Qiu, F. et al. Arginine starvation impairs mitochondrial respiratory function in ASS1-deficient breast cancer cells. Sci. Signal 7, ra31 (2014).

Fu, J. et al. Cellular reprogramming during anti-PD-1 and chemotherapy treatment in early-stage primary hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66659-y (2025).

Wolff, A. C. et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: american society of clinical oncology/college of american pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 3997–4013 (2013).

Salgado, R. et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann. Oncol.: Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. / ESMO 26, 259–271 (2015).

Symmans, W. F. et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 25, 4414–4422 (2007).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

DePristo, M. A. et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43, 491–498 (2011).

McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Van der Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to high-confidence variant calls: the genome analysis toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 43, 11.10. 11–11.10. 33 (2013).

Cibulskis, K. et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 213–219 (2013).

Weinstein, J. N. et al. The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 45, 1113–1120 (2013).

Kim, S. et al. Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nat. methods 15, 591–594 (2018).

Ramos, A. H. et al. Oncotator: cancer variant annotation tool. Hum. Mutat. 36, E2423–E2429 (2015).

Lawrence, M. S. et al. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature 505, 495–501 (2014).

Diaz-Gay, M. et al. Assigning mutational signatures to individual samples and individual somatic mutations with SigProfilerAssignment. Bioinformatics 39, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btad756 (2023).

Carter, S. L. et al. Absolute quantification of somatic DNA alterations in human cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 413–421 (2012).

Shen, R. & Seshan, V. E. FACETS: allele-specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic acids Res. 44, e131–e131 (2016).

Mermel, C. H. et al. GISTIC2. 0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 12, 1–14 (2011).

Taylor-Weiner, A. et al. DeTiN: overcoming tumor-in-normal contamination. Nat. methods 15, 531–534 (2018).

Liu, D. et al. Evolution of delayed resistance to immunotherapy in a melanoma responder. Nat. Med 27, 985–992 (2021).

Wang, L., Wang, S. & Li, W. RSeQC: quality control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics 28, 2184–2185 (2012).

Wang, L. et al. Measure transcript integrity using RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinforma. 17, 1–16 (2016).

Zeng, Z. et al. Cross-site concordance evaluation of tumor DNA and RNA sequencing platforms for the CIMAC-CIDC network. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 5049–5061 (2021).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 1–21 (2014).

Fang, Z., Liu, X. & Peltz, G. GSEApy: a comprehensive package for performing gene set enrichment analysis in Python. Bioinformatics 39, btac757 (2023).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Li, T. et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res 48, W509–W514 (2020).

Jiang, P. et al. Systematic investigation of cytokine signaling activity at the tissue and single-cell levels. Nat. methods 18, 1181–1191 (2021).

Cardoso, F. et al. 70-gene signature as an aid to treatment decisions in early-stage breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 717–729 (2016).

Krijgsman, O. et al. A diagnostic gene profile for molecular subtyping of breast cancer associated with treatment response. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 133, 37–47 (2012).

Beghini, F. et al. Integrating taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of diverse microbial communities with bioBakery 3. Elife 10, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.65088 (2021).

Blanco-Míguez, A. et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1633–1644 (2023).

Mallick, H. et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput Biol. 17, e1009442 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an NCI DF/HCC SPORE in Breast Cancer (P50 CA168504) grant for correlative analyses; by a Susan G. Komen Leadership Grant for tumor sequencing (SAC21204 to EAM); and by funding from Merck for the overall trial. BluePrint and MammaPrint RNA signature testing was funded by Agendia. The sponsors played no role in the design or conduct of the study. EAM acknowledges the Rob and Karen Hale Distinguished Chair in Surgical Oncology. The authors acknowledge Timothy Erick, PhD, for writing assistance and Valerie Hope Goldstein for editorial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.A.M. and S.M.T. served as supervising senior authors on this manuscript. Study design: A.G.W., J.F., I.E.K., and S.M.T. Data gathering: A.G.W., J.F., B.B.K., T.M.K., A.P., E.W., J.A., M.D., S.C., A.M.-A., and X.M. Data analysis: A.G.W., J.F., X.C., T.L., T.M.K., Y.S., D.Y., K.M., B.R., J.P., M.K., W.A., X.M., N.T., E.M.V., D.A., and R.J. Manuscript writing: A.G.W. and J.F. Critical review of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.G.W. reports consulting or advisory roles for AstraZeneca and AMBRX; speaker’s honoraria from AstraZeneca; and research support (to institution) from Genentech, Gilead, Macrogenics, and Merck. J.B. reports research support from Genentech/Roche and Incyte Corporation; has received advisory board payments from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Mallinckrodt; and is an inventor on patents regarding immunotherapy targets and biomarkers in cancer. M.K. and W.A. are employees of Agendia. B.R. reports having institutional patents filed on methods for clinical interpretation. E.A.M. reports compensated service on scientific advisory boards for AstraZeneca, BioNTech, and Merck; uncompensated service on steering committees for Bristol Myers Squibb and Roche/Genentech; speakers honoraria and travel support from Merck Sharp & Dohme; and institutional research support from Roche/Genentech (via SU2C grant) and Gilead. EAM also reports research funding from Susan Komen for the Cure for which she serves as a Scientific Advisor, and uncompensated participation as a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Board of Directors. S.M.T. reports consulting or advisory roles for Novartis, Pfizer/SeaGen, Merck, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Eisai, Bristol Myers Squibb/Systimmune, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Blueprint Medicines, Reveal Genomics, Sumitovant Biopharma, Artios Pharma, Menarini/Stemline, Aadi Bio, Bayer, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Natera, Tango Therapeutics, eFFECTOR, Hengrui USA, Cullinan Oncology, Circle Pharma, Arvinas, BioNTech, Launch Therapeutics, Zuellig Pharma, Johnson&Johnson/Ambrx, Bicycle Therapeutics, BeiGene Therapeutics, Mersana, Summit Therapeutics, Avenzo Therapeutics, Aktis Oncology, Celcuity, Boehringer Ingelheim, Samsung Bioepis, Olema Pharmaceuticals, Tempus, and Boundless Bio; research funding from Genentech/Roche, Merck, Exelixis, Pfizer, Lilly, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, NanoString Technologies, Gilead, SeaGen, OncoPep, Daiichi Sankyo, Menarini/Stemline, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Olema Pharmaceuticals; and travel support from Lilly, Gilead, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Arvinas, and Roche. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Gong Tang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Waks, A.G., Fu, J., Chu, X. et al. Efficacy, safety, and predictive biomarkers of neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel and pembrolizumab in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: A randomized pilot trial. Nat Commun 16, 10705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66667-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66667-y