Abstract

Sulfoquinovose (SQ) and sulfoquinovosyl glycerol (SQGro) are derived from abundant membrane sulfolipids termed sulfoquinovosyl diacylglycerols (SQDG) and produced by photosynthetic organisms, serving as sources of carbon and sulfur for bacteria. The conversion processes of these sulfoquinovosyl compounds within marine ecosystems, and their quantitative contributions to the marine organic matter pool, are poorly understood. Here, we identify Alteromonas macleodii, a marine bacterium capable of metabolizing SQ and SQGro through a sulfoquinovosidase. This enzyme converts SQGro to SQ and is a member of a clade within glycoside hydrolase family 31, distinct from other sulfoquinovosidases. The ubiquitous presence of sulfoquinovosidases and their transcripts throughout marine environments implicates active metabolism of sulfoquinovose glycosides, particularly in the sunlit surface ocean. We further demonstrate that marine algae produce significant quantities of cellular SQGro, and we estimate the annual turnover of SQGro using field samples from coastal and open ocean environments. Together with SQDG and SQ, these sulfoquinovosyl compounds constitute a substantial portion of the marine organic carbon turnover, estimated at around 1.5 petagrams of carbon per annum. These findings reveal a vast, previously unappreciated pool of organosulfonates within the microbial food web that contributes significantly to the marine carbon and sulfur cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic matter flows through the marine microbial food web, facilitating nutrient and energy exchange between autotrophs and heterotrophs, and sustaining ecosystem function1. Annual net primary production consists of 1.3 billion tons of sulfur fixed by phytoplankton in the global ocean, and forms the foundation of the ocean’s organic sulfur pool2. Organosulfur compounds provide marine microorganisms with protein building blocks (cysteine and methionine)3, photosynthetic membrane lipids4, and molecules that play crucial roles as cell osmolytes5, redox balancers6, predator deterrents7, and hydrostatic pressure protectants8. Bacteria can catabolize various organosulfur compounds from the exudates, detritus, and viral lysates of phytoplankton. The canonical elemental ratio of sulfur to carbon in marine phytoplankton biomass is approximately 1:959,10. Organosulfur compounds produced by phytoplankton, such as dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), provide a vital sulfur source for bacteria10. Furthermore, these compounds also supply carbon for heterotrophic bacteria, as exemplified by molecules like organosulfonates11,12. Abundant organosulfonates serve as ecologically important metabolic currencies between phytoplankton and heterotrophic bacteria, forming a metabolic network in the surface ocean13. Consequently, organosulfur compounds function as key molecular links between the marine sulfur and carbon cycles.

Marine organosulfonates include a range of simple C2 (e.g., taurine, isethionate) and C3 carbon species (e.g., 2,3-dihydroxypropane-1-sulfonate (DHPS))14,15, as well as the C6 sulfosugar sulfoquinovose (SQ; 6-deoxy-6-sulfo-D-glucose) (Supplementary Fig. 1a)16. Marine algae generate SQ (10–27,000 μM), which is metabolized by marine Roseobacteraceae and Oceanospirillaceae bacteria through three distinct but related pathways: the sulfolytic SQ monooxygenase (sulfo-SMO), a variant of SQ Embden−Meyerhof−Parnas (sulfo-EMP2), and the sulfolytic SQ dioxygenase (sulfo-SDO) pathways17,18,19. Sulfoquinovosyl diacylglycerol (SQDG) (Supplementary Fig. 1a), a precursor of SQ, is widespread in the membranes of various photosynthetic organisms, where it plays a crucial role in chloroplast and photosynthesis development and function20,21,22. Its annual production in the biosphere has been estimated to be on the order of 10 billion tons23. Available evidence suggests that SQDG biosynthesis involves UDP-SQ synthase and UDP-SQ: diacylglycerol glycosyltransferase, however, these enzymes have not been studied within marine algae. Marine diatoms and cyanobacteria, responsible for approximately 40% and 25% of ocean net primary productivity, respectively24,25, can increase their SQDG production to compensate for phospholipid deficiencies in oligotrophic environments26,27. In the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana, SQDG contributes around 9% of its cellular sulfur pool14. For cyanobacteria, SQDG content varies between 50% and 60% of their total polar membrane lipids26. SQDG can be detected throughout the water column, from the upper ocean to the deep sea, and is a potential vector for vertical carbon transport in the ocean28,29.

Sulfoquinovosyl glycerol (SQGro) (Supplementary Fig. 1a), the delipidated form of SQDG, was first described in the freshwater alga Chlorella ellipsoidea30. Terrestrial and gut microorganisms harbor sulfoquinovosidases belonging to subfamily 13 of glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 31 that can hydrolyse SQGro into SQ31. These enzymes have not been found in marine bacteria. However, the recent discovery of a dedicated family of sulfoquinovosidases (family GH188), which also hydrolyze SQGro to release SQ, revealed that these enzymes are widespread in marine Roseobacteraceae and marine algae18. However, SQGro itself has not been identified in the ocean. Furthermore, the role of sulfoquinovosyl compounds in marine carbon flux remains poorly understood, particularly regarding their conversions and contributions to the organic matter pool.

In this work, we identify common marine bacteria capable of metabolizing SQ and SQGro, and characterize a previously undescribed sulfoquinovosidase defining an unexpected trait within a distinct clade of GH31 sulfoquinovosidases. We quantify the distribution of sulfoquinovosyl compounds in representative algae, showing that they are ubiquitous and can be metabolized by GH188 sulfoquinovosidases. By analyzing field samples, we estimate the total amount of marine sulfoquinovosyl compounds. These findings, combined with metagenomic and transcriptomic data from the ocean, suggest a potentially vast flow of carbon based on organosulfonates within the microbial food web, that likely fuels the marine carbon cycle.

Results

Identification of SQ-catabolizing bacteria within diatom-associated microbial communities

DNA stable-isotope probing (DNA-SIP) analysis of bacteria isolated from a non-axenic culture of Thalassiosira pseudonana 220 showed that bacteria belonging to the Alteromonadaceae and Roseobacteraceae families incorporated 13C from 13C6-SQ added to the media (Fig. 1a, b), indicating the capacity of some genera within these two families to metabolize SQ. Within Alteromonadaceae, only the genus Alteromonas demonstrated a 16S rRNA gene abundance exceeding 1% of the total community and showed significant 13C assimilation, with an atom-fraction excess of 13C up to 0.62 (Supplementary Data 1). PacBio sequencing results indicated that the exogenously added 13C6-SQ stimulated the growth of Alteromonadaceae with an increasing population fraction from 0.4% to 40.9%, wherein it became the dominant taxa in the system (Fig. 1c). A. macleodii exhibited the highest abundance, accounting for 74% of the Alteromonas species and 30.4% of the total bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences (Fig. 1d), suggesting that this species may play a key role in SQ metabolism. In contrast, the Roseobacteraceae demonstrated greater diversity, and included Roseobacter denitrificans and Dinoroseobacter shibae (Fig. 1e). Our previous research showed that Roseobacter denitrificans OCh 114 and Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL 12 are SQ-metabolizing species19.

a, b The normalized distribution of 16S rRNA gene copies in CsCl density gradients for two bacterial taxa (Alteromonadaceae and Roseobacteraceae) with added 12C-SQ or 13C6-SQ. c Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the bacterial community before and after addition of 13C6-SQ to the culture media was performed using PacBio. Pie charts show the percentage of relative abundance of different bacterial community sequences before and after cultivation. d, e Percentages of relative abundance of sequences in Alteromonadaceae and Roseobacteraceae after cultivation. f Growth curve of A. macleodii ATCC 27126 on SQ. Optical density of the medium (blue), and concentrations of SQ (red), sulfate (orange), and sulfite (green) in the medium. Data represent means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). g Scatter plot of comparative proteomic analysis of A. macleodii ATCC 27126 cultured with SQ + yeast extract vs. yeast extract. Red dots represent proteins that are significantly increased in abundance (p < 0.05, t-test, two-sided) in SQ + yeast extract growth conditions, whereas blue dots represent those proteins that are significantly decreased in abundance (p < 0.05, t-test, two-sided). The proteins labelled with gene locus are increased in abundance at least tenfold. The protein IDs (WP_014951127.1, WP_014951128.1, WP_014951129.1, WP_014951130.1, WP_014951131.1, WP_014951132.1, WP_014951133.1, WP_014951134.1, WP_014951135.1, WP_014951136.1 and ANG62935.1, ANG62936.1, ANG62937.1, ANG62938.1, ANG62939.1, ANG62940.1, ANG62941.1) correspond to the gene locus tags (MASE_17990-18035 and Ga0133504_112202-112208). The statistical details are provided in Supplementary Data 2. h Formation of sulfite was detected at an absorbance of 580 nm in the SQ-containing reaction, both with and without AmSqoD, using a colorimetric Fuchsin assay. i The gene cluster encoding proteins involved in SQGro and SQ metabolism in A. macleodii ATCC 27126 and M. aestuarii ST58-10, with gene site tags and annotations. The AmsqgH gene of A. macleodii ATCC 27126 is co-located with genes involved in SQ catabolism through the sulfo-SDO pathway, in which SQ is cleaved via C-S bond to produce sulfite and 6-dehydroglucose. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We studied A. macleodii ATCC 27126 and demonstrated its ability to utilize SQ as a growth substrate. After 36 h of cultivation, the strain consumed approximately 64% of the SQ in the media, accompanied by the production of sulfate and sulfite (Fig. 1f). Comparative proteomic analysis revealed a cluster of eight proteins in A. macleodii ATCC 27126 that were present at significantly increased abundance during growth with SQ compared to without (locus tags: MASE_17990-18035; fold-change > 2, p < 0.05) (Fig. 1g). Among the identified proteins, MASE_18005 (named AmSqoD) was 58-fold more abundant during growth with SQ (Supplementary Data 2). It exhibited 34% sequence identity to MaSqoD from Marinobacterium aestuarii ST58-10, an Fe2+ dependent α-ketoglutarate (α-KG): SQ dioxygenase in the sulfo-SDO pathway (Fig. 1i)17. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that AmSqoD and MaSqoD cluster together, suggesting a close evolutionary relationship (Supplementary Fig. 1b and Supplementary Data 3). Furthermore, they share similar predicted 3D structures with a root-mean-square deviation of 1.3 Å and possess conserved catalytic and binding residues (H121, E123, and H313 in AmSpoD, H115, E117, and H308 in MaSqoD) as determined by mutation analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). Incubation of SQ and α-KG with recombinantly expressed and purified AmSqoD led to the release of sulfite as detected by a colorimetric Fuchsin assay (Fig. 1h), indicating that AmSqoD can catalyze the cleavage of SQ17. The product of the reaction was derivatized with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) and then analyzed by LC-MS, which revealed a peak at m/z (-ve) 357.0318, indicating the formation of the DNP-hydrazone of 6-dehydroglucose (Supplementary Fig. 1e, f). The relevant gene cluster in A. macleodii ATCC 27126 exhibits distinct features for SQ metabolism compared to M. aestuarii ST58-10 (Fig. 1i). It includes MASE_17995 and MASE_17990, which were present at higher abundance in the comparative proteomics data and are predicted to encode a two-component sulfite dehydrogenase, and MASE_18000, predicted to encode a sulfate transporter (Fig. 1i). Additionally, a TonB-dependent receptor (MASE_18030), potentially facilitating SQ uptake, exhibits a dramatic 107-fold higher abundance (Supplementary Data 2). These findings reveal A. macleodii ATCC 27126 as a marine bacterium capable of metabolizing SQ. Evolutionary analysis indicated that most of the A. macleodii strains (22/24) contain the sulfo-SDO pathway responsible for SQ metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Growth of marine bacteria on SQ glycosides: discovery of a novel sulfoquinovosidase in A. macleodii ATCC 27126

R. denitrificans OCh 114 can grow using SQGro (Fig. 2a). This bacterium encodes a family GH188 protein located upstream of the previously identified sulfo-SMO gene cluster of R. denitrificans OCh 11419. Analysis of the recombinant protein, RdSqgA, revealed it to be an NAD+-dependent sulfoquinovosidase that acts on SQGro to form SQ (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Growth experiments conducted with A. macleodii ATCC 27126 showed that it consumed 77% of SQGro within 36 h (Fig. 2b), producing sulfite and sulfate, suggesting it contains an SQase capable of cleaving SQGro to give SQ, which is metabolized through a sulfo-SDO pathway. Proteins within the SQ-metabolizing gene cluster of A. macleodii ATCC 27126 that are of higher abundance when cultured on SQ are also significantly increased in abundance (2-223 fold change, p < 0.01) when cultured in the presence of SQGro (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Data 2). MASE_18025 (named AmSqgH) shares low protein sequence identities of 27.9% with sulfoquinovosidase EcYihQ from Escherichia coli K-12 and 28% with sulfoquinovosdiase AtSQase from Agrobacterium fabrum C5831,32. LC-MS analysis of the reaction mixture containing SQGro and recombinant AmSqgH revealed a peak at m/z 243.0170 that co-eluted with authentic SQ (Fig. 2d, e). Recombinant AmSqgH was highly active on p-nitrophenyl sulfoquinovoside (PNPSQ) (Fig. 2f), with Michaelis–Menten parameters kcat = 119 ± 19 s−1, KM = 13.0 ± 2.2 mM, and kcat/KM = 9170 ± 1490 M−1 s−1 (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 3c). These results establish that AmSqgH is a sulfoquinovosidase.

a Growth curve of R. denitrificans OCh 114 on SQGro (A600 represents optical density, concentration refers to SQGro). A600 (C1) (orange) indicates a control group with only bacteria added and no SQGro. A600 (C2) (black) represents a control group containing SQGro and no bacteria, with concentration of SQGro shown by SQGro (C) (blue). A600 (T) (red) represents the experimental group with both SQGro and bacteria, with concentration of SQGro shown by SQGro (T) (green). Data represent means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). b Growth curve of A. macleodii ATCC 27126 on SQGro. Optical density of the medium (orange), SQGro concentration in the medium (purple), sulfate concentration in the medium (green), and sulfite concentration in the medium (blue). Data represent means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). c Scatter plot of comparative proteomic analysis of A. macleodii ATCC 27126 cultured with SQGro + yeast extract vs. yeast extract. Red dots represent proteins that are increased in abundance (p < 0.05, t-test, two-sided) in SQGro + yeast extract growth conditions, whereas blue dots represent those proteins that are significantly decreased in abundance (p < 0.05, t-test, two-sided). The proteins marked by gene locus are increased in abundance at least tenfold. The protein ID (WP_014951134.1) corresponds to the gene locus tag (MASE_18025). The statistical details are provided in Supplementary Data 2. d Enzymatic activity assay measured for AmSqgH catalyzed hydrolysis of SQGro. LC-MS extracted ion chromatograph of SQ with m/z 243.0170 after the reaction. e MS-MS fragmentation of SQ product showing HSO3−, C4H7O6S−, and C3H5O5S− ions. f Enzyme activity measured for AmSqgH catalyzed hydrolysis of PNPSQ. Data represent means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). g Activity plot for PNPSQ hydrolysis by AmSqgH from A. macleodii ATCC 27126 showing fit to Michaelis–Menten equation. Data represent means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). h Predicted 3D structure of AmSqgH (green) superimposed on that of EcYihQ (pink, PDB code: 5AEE) and AtSQase (purple, PDB code: 5OHS) and expansion showing β-sheet connection within EcYihQ and AtSQase. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

AmSqgH, EcYihQ, and AtSQase share a common (a,b)8-barrel fold with an additional β-sheet domain33. However, EcYihQ and AtSQase have additional connecting β-sheets absent in AmSqgH (Fig. 2h). Despite sharing a conserved catalytic dyad (Asp-Asp) comprising the catalytic nucleophile and general acid-base for glycoside cleavage, 3D modelling, docking and mutational analyses reveal significant divergence in the amino acid residues responsible for substrate binding (Supplementary Fig. 3d). The important Q/E-RWY motif (Q288(E270), R301/R283, W304/W286 and Y508/Y491) found in EcYihQ and AtSQase for the structural recognition of the side chains and sulfonate group of SQGro is not conserved in AmSqgH (Supplementary Fig. 3d). AlphaFold2 analysis predicts that AmSqgH uses a distinct set of residues (R302, T377, K412, F513) to recognize and bind SQGro (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). AmSqgH and RdSqgA, like EcYihQ, exhibit SQDG cleavage activity (Supplementary Fig. 3f, g). The absence of a signal peptide in these sulfoquinovosidases suggests an intracellular localization. This is consistent with the observation that R. denitrificans OCh 114 cannot utilize exogenously added SQDG (Supplementary Fig. 3h), suggesting that SQDG cannot be directly imported into the cell. However, the presence of a TRAP transporter and substrate binding protein in the gene cluster suggests that R. denitrificans OCh 114 can import SQ/SQGro (Supplementary Fig. 3i–k). Therefore, SQGro is likely the natural substrate for these bacterial intracellular sulfoquinovosidases.

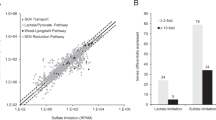

AmSqgH homologs (SqgH) were identified in marine gammaproteobacteria, including Alteromonadaceae, Pseudoalteromonadaceae, Colwelliaceae, Arenicellaceae, and Cellvibrionaceae, and share similar predicted structures and possess conserved catalytic and binding residues (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 4a, and Supplementary Data 4). These gammaproteobacteria harbor gene clusters containing both sqgH and sulfo-SDO pathway genes (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The gene cluster compositions closely resemble that found in A. macleodii ATCC 27126, although some, such as those in Pseudoalteromonas, lack genes associated with sulfite metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The metabolic potential encoded by these gene clusters is exemplified by Alteromonas stellipolaris R10SW13 and Pseudoalteromonas marina ECSMB 14103, which are both capable of metabolizing SQGro and SQ (Supplementary Fig. 4c–f). A. macleodii F12, which lacks this gene cluster or any others associated with SQ metabolism, exhibited no evidence of SQGro or SQ metabolism in feeding experiments (Supplementary Fig. 4g, h).

Phylogenetic tree (constructed using IQ-TREE) of selected species containing examples of all predicted GH31 subfamily protein sequences (shown at right). The predicted sulfoquinovosidase function of SqgH clade and GH31_13 subfamily protein sequences were annotated according to the proposed SQ metabolic pathway for the gene cluster in which they are located. Numbers at nodes correspond to bootstrap support for major nodes over 60%. Insert: AmSqgH, as well as proteins from GH31_3 (named GH31_3, from E. coli K-12, gene locus: Ga0198492_01_4502455_4504773) and GH31_6 (named GH31_6, from Achromobacter aegrifaciens, gene locus: RA224_28300) subfamily were used to test catalytic activity on PNPSQ. AmSqgH were used to test catalytic activity on PNPXyl and PNPGlc, and SDS-PAGE analyses of the purified GH31_3 and GH31_6. Data represent means ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). Pathway abbreviations: sulfo-EMP sulfoglycolytic Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas, sulfo-EMP2 a variant of the sulfo-EMP pathway, sulfo-ED sulfoglycolytic Entner-Doudoroff, sulfo-TK sulfoglycolytic sulfoquinovose transketolase, sulfo-TAL sulfoglycolytic transaldolase pathways96. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

SqgH belongs to a distinct clade of family GH31

Phylogenetic analysis of AmSqgH and its close homologs revealed that they form a distinct clade separate from the previously classified 20 subfamilies within GH31 (Fig. 3). Previously characterized GH31 sulfoquinovosidases, such as EcYihQ and AtSQase, are members of subfamily GH31_13 and are associated with various SQ degradation pathways, excluding the sulfo-SDO pathway (Fig. 3). Despite their close phylogenetic relationship to the SqgH clade, GH31_3 and GH31_6 subfamily proteins exhibit no detectable activity on PNPSQ (Fig. 3). GH31_3 possesses activity towards 4-nitrophenyl α-D-xylopyranoside (PNPXyl) or 4-nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside (PNPGlc)34, while AmSqgH, similar to GH31_13 members (EcYihQ and AtSQase)33, shows no detectable activity towards these two substrates (Fig. 3). The SqgH clade and GH31_13 subfamily appear to be examples of convergent evolution, with each independently arising from a common ancestor within family GH31, and developing the catalytic capacity for SQGro in marine and non-marine environments, respectively. While phylogenetic analysis of the AmSqgH homologues highlights that they form a clade distinct from subfamilies 3 and 6, application of the CAZy classification methodology based on hidden Markov models results in formal assignment into subfamily 3 (Supplementary Data 5).

Ubiquitous distribution of sulfoquinovosidase and SQ-catabolizing genes in marine environments

Gene abundances of sqgH and sqgA homologs were investigated in sequences stemming from the Tara Oceans expeditions35 and coastal stations (Bohai Sea and Jiulongjiang Estuary)36 and were compared with those for sqoD in sulfo-SDO and smoC in sulfo-SMO (encoding SQ monooxygenase). The sqgH, sqoD, sqgA, and smoC genes are widely expressed in the global ocean (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 6–8). The abundance of prokaryotic sqgH transcripts (median: 0.09%) was almost equal to that of sqoD (median: 0.11%), while sqgA transcript abundance (median: 0.88%) was slightly lower than that of smoC (median: 1.60%) (Fig. 4a). This suggests that prokaryotic sqgH and sqoD, as well as sqgA and smoC, collaborate for heterotrophic metabolism of SQGro and SQ in the ocean. A positive relationship between chlorophyll a concentration and abundance was found for sqgH, sqgA, sqoD, and smoC, in both metagenomes and metatranscriptomes (Fig. 4b, c), suggesting that active bacterial metabolism of SQGro occurs in the global ocean, particularly in regions of high photosynthetic productivity. Regions with high chlorophyll a values (>2 mg/m3) coincided with high-latitude zones (60–90° N and 60–90° S), such as the Arctic and Southern Oceans (Fig. 4d, e and Supplementary Data 7). These areas harbor thriving communities of photosynthetic organisms, potentially acting as abundant sources of SQGro for epipelagic consumers. Among all Tara Oceans stations, bacterial sqgH metagenomics, transcript and sqoD transcript abundances were slightly lower in the epipelagic zone (depth, <200 m) compared to the mesopelagic zone (depth, 200–1000 m) (Fig. 4f). The metagenomics abundance of bacterial sqgA and smoC, along with their transcript levels, was significantly higher in the epipelagic zone compared to the mesopelagic zone (Mann–Whitney test, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4f). This indicated that the metabolic activity for SQGro and SQ is widely distributed across the epipelagic and mesopelagic ocean. Additionally, sqgA genes are also present marine gammaproteobacteria, particularly Oceanospirillaceae (Supplementary Fig. 5). These SqgA proteins exhibit sulfoquinovosidase activity (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c). However, transcripts of sqgA and the sulfo-SDO pathway gene sqoD from Oceanospirillaceae were rarely detected in Tara Oceans samples. These findings suggest that Alteromonadaceae and Roseobacteraceae bacteria are the principal consumers of SQGro and SQ in the global ocean.

a Comparison of gene abundance and transcription abundance of sqgH and sqoD, sqgA and smoC in the Tara Oceans prokaryotic database. The upper whisker extends from the upper hinge to the largest value that is no more than 1.5 × IQR (inter-quartile range) from the upper hinge, and the lower whisker extends from the lower hinge to the smallest value that is no further than 1.5 × IQR from the lower hinge. Correlation between the abundance of sqgH, sqgA, and chlorophyll a concentration in the b metagenome (MG) and c metatranscriptome (MT) of the Tara Oceans prokaryotic database. Linear regression analysis of log10 transformed gene/transcript abundance vs chlorophyll a concentration. In the MG (b) (sample size, sqgH n = 180, R2 = 0.144, p = 0.019; sqgA n = 180, R2 = 0.339, p = 1.2 × 10−15) and MT (c) (sqgH n = 145, R2 = 0.045, p = 0.549; sqgA n = 190, R2 = 0.354, p = 4.5 × 10−10). sqgH (green), sqgA (orange). 95% confidence intervals are shown by dashed lines. ∗∗, p < 0.01. ∗∗∗, p < 0.001 (Spearman’s correlation), full statistical details can be found in the Source Data file. Distribution of d sqgH and e sqgA in prokaryotes in Tara Ocean database. The circle size indicates the relative abundance of gene transcripts normalized by 10 single-copy genes. f Gene abundance and transcription abundance of sqgH, sqoD, sqgA, and smoC in the epipelagic ocean (<200 m) and mesopelagic ocean (200–1000 m). (sample size, MG, epipelagic: sqgH n = 142, sqoD n = 142, sqgA n = 142, smoC n = 142, mesopelagic: sqgH n = 38, sqoD n = 38, sqgA n = 38, smoC n = 38. MT, epipelagic: sqgH n = 123, sqoD n = 121, sqgA n = 167, smoC n = 168, mesopelagic: sqgH n = 22, sqoD n = 22, sqgA n = 23, smoC n = 15.). ∗∗, p < 0.01. ∗∗∗, p < 0.001, ns not significant (Mann–Whitney test, two-sided). Abundance (% abundance relative to the median abundance of 10 single-copy core genes) of sqgH, sqoD, sqgA, and smoC. Gene transcripts were undetectable at some sites, which is represented by an omission of data points. The upper whisker extends from the upper hinge to the largest value that is no more than 1.5 × IQR (inter-quartile range) from the upper hinge, and the lower whisker extends from the lower hinge to the smallest value that is no further than 1.5 × IQR from the lower hinge. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Abundances of sulfoquinovosyl compounds in culturable algae

SQDG, SQGro, and SQ were detected within all investigated cyanobacteria and algae, including diatoms, coccolithophore, flagellates, dinoflagellates, green algae, Prochlorococcus, and Synechococcus (Table 1). SQGro concentrations in cultured algae ranged from 40 to 1870 μM, while SQ concentrations ranged from 8 to 242 μM (Table 1). The lowest cellular concentrations of SQ and SQGro were measured in the dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense, whereas the highest concentrations were measured in the diatom Skeletonema costatum. Among algae, diatoms exhibited SQGro concentrations nearly tenfold higher than SQ. Coccolithophore and flagellates of haptophyta species also showed significantly higher SQGro than SQ (Table 1). In contrast, cyanobacteria exhibit higher intracellular SQ concentrations than SQGro (Table 1). SQDG was present at millimolar cellular concentrations in all investigated algae, with concentrations two to three orders of magnitude higher than SQGro (Table 1). SQGro was detected in extracellular metabolite pools of all investigated marine algae cultures (Table 1), suggesting that this compound can be released from photosynthetic organisms into seawater in marine environments.

Abundance of organosulfonates in the ocean

We conducted field investigations on sulfoquinovosyl compounds and DHPS from marine particulates (Fig. 5a). These compounds have a widespread distribution throughout the euphotic layer in coastal and open ocean environments (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Data 9). The concentrations observed are positively correlated with chlorophyll a: SQDG (Pearson’s r = 0.77, p = 7.5 × 10−8), SQGro (r = 0.61, p = 1.4 × 10−4), and SQ (r = 0.70, p = 1.5 × 10−5) and DHPS (r = 0.35, p = 6 × 10−2), respectively (Fig. 5c–f). Particulate organic carbon (POC) also showed a positive correlation with chlorophyll a (r = 0.82, p = 3.9 × 10−9) (Fig. 5g). This indicates a primarily photosynthetic origin for these organosulfur compounds in the ocean. Geographical patterns indicate that coastal environments exhibit significantly higher concentrations of sulfoquinovosyl compounds compared to the open ocean (Supplementary Data 9). SQDG was present at significantly higher concentrations than SQGro (Tukey’s test, p = 3.3 × 10−12) and SQ (p = 3.0 × 10−10) (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Data 9). The concentrations of SQGro and SQ are comparable to that of DHPS, widely recognized as an important species in the marine organosulfonate metabolic network (Fig. 5b). SQDG in all survey stations was mainly composed of medium-chain fatty acids with a total of 28–32 carbon atoms in the fatty acid chains (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The median molar C:S ratio in the marine environment reaches up to 42:1 (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Compared with SQ, SQGro, and DHPS (median: 0.11%, 0.01%, 0.01%), SQDG contributed more to POC (median: 5.5%), which was similar to the proportion of 4.2% POC (mean value) contributed by SQDG in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean (Supplementary Data 9)29. While these sulfoquinovosyl compounds represent only 5.3% of coastal POC, their contribution can reach up to 7.4% of POC in the open ocean, potentially enhancing surface water carbon export in the global open ocean.

a Map of sampling stations of the coastal environments and central North Pacific Ocean, which are distinguished by different symbols. b Particulate concentrations of SQDG, SQGro, SQ, and DHPS (3–200 µm) from marine environment (sample size, SQDG n = 34, SQ n = 30, SQGro n = 34, DHPS n = 30). Box plots show median values (central black line), the upper and lower hinges correspond to the first and third quartiles. The upper whisker extends from the upper hinge to the largest value that is no more than 1.5 × IQR (inter-quartile range) from the upper hinge, and the lower whisker extends from the lower hinge to the smallest value that is no further than 1.5 × IQR from the lower hinge. ∗∗∗, p < 0.001 (Tukey HSD, two-sided), full statistical details can be found in the Source Data file. c–g Correlation analysis of SQDG, SQ, SQGro, DHPS, POC, and chlorophyll a. Linear regressions of log10 transformed organosulfonates (SQDG, SQ, SQGro, DHPS) vs. chlorophyll a concentration are shown (solid lines) together with 95% CI (dashed lines). Sample size, SQDG n = 34, r = 0.77, p = 7.5 × 10−8; SQ n = 30, r = 0.70, p = 1.5 × 10−5; SQGro n = 30, r = 0.61, p = 1.4 × 10−4; DHPS n = 30, r = 0.35, p = 6 × 10−2; POC n = 34, r = 0.82, p = 3.9 × 10−9 (Pearson’s correlation), full statistical details can be found in the Source Data file. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Bacteria possessing sqgH or sqgA sulfoquinovosidase genes are primarily found in marine environments, including coastal regions, the open ocean, and in association with phytoplankton (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 10). Our 13C6-SQ incubation experiments suggest that SQ catabolism occurs within phycosphere-associated microbial communities. Among identified Roseobacteraceae genera containing sqgA sulfoquinovosidase genes, 23 out of 94 were isolated from niches associated with phytoplankton, such as diatoms, dinoflagellates, and red algae (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 10). Besides inhabiting the phycosphere, Alteromonadaceae species are also known to interact closely with cyanobacteria, influencing their growth, survival, and metabolic processes37. Alteromonadaceae and Roseobacteraceae bacteria are often opportunistic, utilizing phytoplankton-derived carbon sources abundant in surface waters38,39. Analysis of cultures with added SQ showed a shift in dominant populations, with Alteromonadaceae surpassing the previously dominant Roseobacteraceae populations (Fig. 1c). Alteromonas bacteria are ubiquitous in marine environments, thriving in waters spanning from polar to tropical regions and from the surface to the deep ocean40. They assist in remineralizing sinking marine particles, such as algal aggregates, and contribute significantly to global carbon cycling41. Additionally, Pseudoalteromonas is commonly found within marine particle-associated microbial communities42. Consequently, these organisms have potential to utilize sulfoquinovosyl compounds present in POC. Sulfoquinovosyl compounds on POC exhibited a dramatic decline with increasing seawater depth in the Central North Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 7b), indicating that most sulfoquinovosyl compounds are readily metabolized by bacteria in the sunlit surface ocean.

This study provides updated estimates of the total annual production of SQDG, SQ, SQGro, and DHPS in the sunlit surface ocean. Based on the correlation between sulfoquinovosyl compounds and chlorophyll a and assuming steady-state kinetics, using the median values, their relative contributions to the POC pool were combined with net primary productivity (53 Pg C/year (yr), 1 Pg = 1 petagram = 1015 × g) and the proportion of algal POC used for heterotrophic consumption (50%) to estimate the total amounts of these organosulfonates43,44. Previous studies considered the variability in bacterial assimilation of organic matter (ranging from 30% for glycolate to 80% for amino acids, with an average of 50%) and combined with bacterial assimilation of marine fixed carbon of 5–25%, leading to an estimated 10–50% range of marine fixed carbon consumed heterotrophically in both coastal and open ocean environments45,46,47. Our estimation adopts a conservative 50% value, consistent with previous estimates evaluating laminarin abundance in the ocean47. This approach yielded annual production estimates of 1.5 Pg C/yr for SQDG (median, 25% quartile, 0.5 Pg C/yr; 75% quartile, 2.1 Pg C/yr), 28.4 Tg C/yr for SQ (25% quartile, 8.7 Tg C/yr; 75% quartile, 72.1 Tg C/yr) (1 Tg = 1 teragram = 1012 × g), 3.9 Tg C/yr for SQGro (25% quartile, 1.3 Tg C/yr; 75% quartile, 7.3 Tg C/yr), and 3.0 Tg C/yr for DHPS (25% quartile, 1.4 Tg C/yr; 75% quartile, 8.6 Tg C/yr) in the ocean. Previous estimates of SQDG were based on terrestrial sources and relied on various assumptions, including the sulfur content of sulfolipids being equal to half the sulfur content of total leaf protein23. This estimation method based on sulfur content is not applicable in the ocean, as we show that the sulfur content of SQDG in marine algae varies greatly from 0.5 to 19% of the total organic sulfur (Supplementary Data 11). An earlier estimate of SQDG production in the biosphere was around 36 Pg/yr (corresponding to roughly 22 Pg C/yr)23. However, this value seems excessively high considering that the total net primary production on Earth is only around 105 Pg C/yr, with roughly equal contributions from land and ocean24.

Our estimates suggest that SQDG may be the most abundant organosulfonate in the ocean. These vast quantities of SQDG serve as a source of SQGro and SQ through biodegradation processes. A lipase capable of degrading SQDG to SQGro was described in the alga Scenedesmus obliquus48. Similarly, a galactolipase in Chlorella kessleri exhibits broad substrate specificity, allowing it to hydrolyze the fatty ester bonds in galactolipids and SQDG49. Recent studies have reported that marine bacteria isolated from marine particles can degrade SQDG50, suggesting the involvement of unidentified extracellular enzymes that might generate SQGro or SQ and allow utilization of the fatty acid content of SQDG by diverse bacteria. This study extends the known presence of SgqA from bacteria to eukaryotic algae through functional validation18. Phylogenetic analysis of SqgA sequences indicates that diatom SqgA cluster with gammaproteobacterial homologs, and other algal SqgA also cluster with gammaproteobacterial Marinomonas hwangdonensis and Granulosicoccus antarcticus (Supplementary Fig. 8). Further analysis strengthens the hypothesis that the eukaryotic sqgA originated from gammaproteobacteria. In contrast to earlier findings that detected YihQ homologues in a limited number of algal species51, this study reveals the widespread presence of SqgA across various marine algal groups, including diatoms, coccolithophores, dinoflagellates, and red algae. Although these homologs exhibited low amino acid identity (31-47%) with RdSqgA (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Data 12), they maintain the same conserved catalytic acid/base and nucleophilic residues (K98, H183, Y127, R156, L160, K162, and E179 in RdSqgA) and exhibit an overall 3D structure consistent with the crystal structure of the RdSqgA, which was resolved at a diffraction resolution of 1.8 Å. These homologs have sulfoquinovosidase activity, allowing the liberation of SQ from marine algae derived SQDG or SQGro (Supplementary Figs. 9–11). By contrast, we could not identify any SqgH clade sulfoquinovosidases with conserved residues in marine algae (Supplementary Fig. 12). Metagenomic data and transcripts from eukaryotic organisms in Tara Oceans database show that they express sqgA, with higher expression levels observed in coastal regions (Supplementary Fig. 13a, b and Supplementary Data 13 and 14). In these regions, the Roseobacteraceae typically comprise upwards of 20% of coastal bacterial taxa52,53. However, the absence of SqgA homologues in algae like Chlorella species and cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, along with the lack of other SQGro hydrolyzing enzymes from family GH31, suggests the existence of alternative pathways for SQDG degradation in these organisms.

This work reveals that SQGro and SQ concentrations within diatoms and coccolithophore are one-to-two orders of magnitude lower than that previously reported for DHPS14. The concentrations of DHPS in marine algal cells are comparable to that of another ecologically important organosulfur compound, DMSP13. However, DHPS has a limited distribution, and is found only in diatoms and coccolithophores14. Although SQGro has the same order of magnitude of abundance as DHPS in marine environment (Fig. 5), sulfoquinovosyl compounds are more widely distributed across algae (Table 1).

While our work shows that the annual production of SQDG is comparable to that of oceanic DMSP (3.8 Pg C/yr), SQDG has a higher ratio of carbon to sulfur compared to DMSP54. This is reflected in the total sulfur content of SQDG (102 Tg S/yr), which is 20-fold less than that of DMSP (2.0 Pg S/yr)2. In aerobic ocean environments, marine bacteria rely on DMSP for 30-100% of their sulfur needs55,56, and while they can also utilize sulfite derived from sulfoquinovose for biosynthesis of essential sulfur-containing molecules (e.g., cysteine, methionine, cofactors, and vitamins), most of this sulfite is oxidized to sulfate for energy generation and to avoid toxicity19,57. In contrast, the sugar and glycerol moieties, along with the fatty acids liberated from sulfoquinovosyl compound degradation, provide community carbon sources and supply metabolic needs57,58. Consequently, sulfoquinovosyl compounds primarily contribute carbon to the microbial food web, with minimal contribution of their sulfur. Marine bacteria similarly catabolize low carbon-sulfur ratio organosulfonates (e.g., taurine, DHPS, sulfolactate, isethionate) into usable carbon (C2 and C3 molecules) and sulfite14,59,60. This “sulfonate-based network” allows utilization of carbon from algae for energy and central carbon metabolism by cleaving the carbon-sulfur bond in these compounds13,61. The sulfite released is then mineralized into sulfate.

Marine algae, major producers of the sulfoquinovosyl compounds SQ and SQDG, also harbor significant quantities of SQGro. Collectively, these compounds constitute a significant fraction of the oceanic organic matter pool, estimated at about 1.5 Pg carbon annually. Marine bacteria metabolizing SQ and SQGro are a key microbial link in the sulfonate-based carbon flow, and their widespread expression of diverse sulfoquinovosidases points to their active participation in the hydrolysis of sulfoquinovose glycosides, enabling catabolism of the released sulfosugar and fueling the oceanic microbial food web (Supplementary Fig. 14). Collectively, these findings underscore a potentially critical link between these abundant organosulfonate species and the essential carbon cycle that sustains marine ecosystems.

Methods

DNA-SIP experiments

13C6-SQ was synthesized using 13C6-glucose as raw material according to the method of Abayakoon et al.62. T. pseudonana 220 (CCMA-220) was from the Center for Collections of Marine Algae (Xiamen University, China), and was cultured in f/2 (with Na2SiO3) medium at 20 °C with an irradiance of 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 until the algal cell abundance was about 105 cells/mL. The attached bacteria were separated by gentle ultrasound, and the T. pseudonana was removed by filtration through a sterile 3-μm polycarbonate filter (47 mm, Millipore, USA). The filtrate was filtered through a sterile 0.2-µm polycarbonate membrane (47 mm, Merck Millipore). The microbial cells collected on the filter membrane were re-inoculated into 1L of sterile aged seawater sourced from the Xiamen offshore (water depth: ~1 m), which had been filtered through a 0.2-µm filter membrane and sterilized by high-pressure steam. The seawater contained 100 μM 13C6-SQ for the experimental group and 100 μM 12C-SQ for the control group, and was incubated in the dark at 25 °C in a static state. Three replicates were set up for both the experimental and control groups. A volume of 1 mL samples was collected every 24 h to quantify the changes in SQ. After 3.5 days, the concentration of SQ in the system decreased by 87%. Microbial cells incubated for 3.5 days were collected through a polycarbonate membrane for subsequent DNA-SIP and bacterial community structure analysis.

DNA Extraction and density centrifugation

DNA from microbial cells captured on filter membranes was extracted using the FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil following the manufacturer’s instructions (MP Biomedicals, USA). DNA concentrations were quantified fluorometrically using the Qubit dsDNA Assay Kit and Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (both from Invitrogen, USA). Approximately 2 μg of DNA from each sample was added to a CsCl solution to a final density of 1.723–1.725 g·mL−1 and transferred into 5.1 mL Quick-Seal™ centrifuge tubes (Backman Coulter, USA). Ultracentrifugation was conducted using an Optima L-100 XP ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, USA) equipped with a VTi 65.2 vertical rotor at 140,000 × g for 72 h. Following centrifugation, mineral oil was layered onto the gradient using a syringe pump (Braintree Scientific, USA). The gradient was divided into 15 fractions, and the refractive index of each fraction was measured using a refractometer (Brix/Rl-Chek, Reichert) for density calculation63. DNA was precipitated by adding two volumes of PEG solution (30% PEG 6000, w/v, 1.6 M NaCl, and 20 μg of glycogen) and then resuspended in 35 μL of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). These purified DNA served as templates for qPCR and 16S rRNA gene PCR for Illumina sequencing.

The qPCR of density fractions

The abundance of bacterial 16S rRNA gene in each gradient fraction was quantified using qPCR with bacterial universal primers 338 F and 518 R on a CFX 96™ real-time system (BIO-RAD)64. Reaction conditions and cycling parameters followed the protocol described by Deng et al. 65. Each 20 μL reaction contained 1 μL of template DNA, 0.5 μM of each primer, 10 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara Bio, Japan), and 5 μg of bovine serum albumin. The amplification protocol consisted of an initial enzyme activation at 95 °C for 105 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. All reactions were run in triplicate, and non-template controls were included in each run to ensure the absence of contamination, and the standard curve was generated using a purified target DNA fragment from E. coli P1065.

Illumina DNA sequencing

Based on the abundance of 16S rRNA genes across density fractions, DNA from 10 selected fractions per sample was used for amplicon sequencing. The V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA genes were amplified using barcoded universal primers 343 F and 798 R on an ABI GeneAmp® 9700 thermal cycler (Thermo, USA) (Supplementary Data 15)66. PCR products were visualized by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, USA), and quantified with a Qubit®3.0 fluorimeter (Life Invitrogen). Twenty-four amplicons with distinct barcodes were pooled in equimolar amounts to construct an Illumina paired-end (PE) sequencing library. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina PE250 platform at Shanghai Biozeron Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Raw sequencing data in FASTQ format were preprocessed using Trimmomatic67, with demultiplexing performed based on sample-specific barcode sequences. Low-quality reads—defined as those with an average quality score below 20 within a 10 bp sliding window were discarded. Paired-end reads with overlapping regions longer than 10 bp were assembled based on sequence overlap. Quality-filtered sequences were then processed using the QIIME pipeline68. Following merging and chimera removal, amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were identified, and taxonomic classification of each ASV was performed using the UCLUST algorithm (https://github.com/topics/uclust) against the SILVA reference database (https://www.arb-silva.de/), applying a confidence threshold of 80%.

PacBio sequencing

Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing of bacterial communities cultured before and after the addition of 13C6-SQ was performed using the PacBio Sequel II platform. The V1–V9 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified using universal primers 27 F and 1492 R (Supplementary Data 15)69, each tagged with sample-specific PacBio barcode sequences. PCR products were visualized on 2% agarose gels, purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen, USA), and quantified using a Qubit®3.0 fluorimeter (Life Invitrogen). SMRTbell libraries were prepared from the amplified DNA using SMRTbell prep kit 3.0 (PacBio, USA). Purified SMRTbell libraries from the pooled and barcoded samples were sequenced on a single PacBio Sequel II system at Shanghai Biozeron Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Raw PacBio reads were processed using SMRT Link Analysis Software v11.0. Demultiplexing and removal of barcode and primer sequences were performed using the lima pipeline (Pacific Biosciences, https://lima.how/). Quality-filtered sequences were further analyzed using QIIME68. Trimming and filtering were applied with a maximum expected error rate of two per read (maxEE = 2). ASVs were assigned taxonomic classifications using the UCLUST algorithm (https://github.com/topics/uclust) against the SILVA reference database (https://www.arb-silva.de/) using confidence threshold of 80%.

Determination of 13C-labeling between unlabeled and labeled density fractions

The distribution curves of bacterial 16S rRNA gene abundance along the CsCl density gradient were analyzed based on the density, 16S rRNA gene copy numbers obtained by qPCR and bacterial 16S rRNA gene abundance of the CsCl fractions from each sample (Supplementary Data 16 and 17). The density of labeled (WLABi) and unlabeled (WLIGHTi) DNA is calculated for each taxon by integrating the 16S rRNA gene abundances of ASVs within the same genus and the 16S rRNA gene copy numbers obtained via qPCR according to Hungate’s et al.70. To minimize biases introduced by baseline variability, only the major peak of DNA was integrated. All fractions that contained >20% of the maximum observed quantity were hence integrated according to Connelly et al.71. Only genera with 16S rRNA gene abundances exceeding 1% of the total abundance were retained for analysis (Supplementary Data 1).

Bacterial and phytoplankton culture

A. macleodii ATCC 27126 was obtained from the Collection Center of Marine Bacteria (Xiamen University, China). R. denitrificans OCh 114 (DSM 7001) was obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH (Braunschweig, Germany). R. denitrificans OCh 114, A. stellipolaris R10SW13, P. marina ECSMB 14103, and A. macleodii F12 were cultured in modified sterile artificial seawater culture medium (pH 8.2, with 1 g/L yeast extract) containing either 222 μM SQGro or 333 μM SQ. Additional culture experiments with SQDG (46.5 µM) were performed for strain R. denitrificans OCh 114. SQDG was first dissolved in methanol, filtered, and added to a medium containing 1% Tween-20 (final volume of methanol is 1% of the medium). An aliquot of 2% of a pre-adapted culture of bacteria was used to inoculate a 5 mL culture and incubated at 28 °C for growth. Bacterial density (A600) was measured using a plate reader (Tecan M200, Männedorf, Switzerland). All bacteria were cultured separately. Samples from each culture were collected and stored at −80 °C for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis.

All algae (Table 1) were from the Center for Collections of Marine Algae (Xiamen University, China). Diatoms (f/2 media with Na2SiO3), dinoflagellates, coccolithophore, flagellates and cholorophyta (f/2 media) were cultured at 20 °C in an incubator with an irradiance of 100 μmol photons m−2 s−172. Pro99 media and SN media were used for cyanobacteria cultivation in an incubator with an irradiance of 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 at 20 °C73,74. Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, New Jersey, USA) and a microscope was used to track the cell abundance of algae. Each culture contained three independent replicates. Algal cells were collected in exponential phase through 0.7-μm GF/F filter membrane (47 mm, Whatman, USA) for SQGro, SQ, SQDG, and total organic sulfur detection. The liquid of the culture filtered by 0.2-μm polycarbonate membrane (Merck Millipore) was used for the detection of extracellular SQGro. All samples were stored at −80 °C until further extraction. Total organic sulfur of the cultured samples was detected by elemental analyzer (vario EL Cube, Elementar, Germany). Before analysis, the sample was washed with 3.2% ammonium formate to remove sulfate75.

Proteomic analysis of A. macleodii ATCC 27126

A. macleodii ATCC 27126 was cultured in modified sterile artificial seawater culture medium (pH 8.2, supplemented with 1 × g/L yeast extract) containing either 333 μM SQ or 222 μM SQGro. Medium containing only 1 × g/L yeast extract was used as a control. Triplicate samples from each growth condition were harvested after centrifugation and digested with trypsin76. The peptides from the digested samples were desalted using a C18 cartridge. After freeze-drying, the peptides were re-dissolved in 40 µL of 0.1% formic acid solution. Data independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry was performed using an Astral high-resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Data were analyzed using DIA-NN software77 with the following parameters: trypsin as the enzyme, a maximum of one missed cleavage site, carbamidomethyl (C) as a fixed modification, and oxidation (M) and acetylation (protein N-terminus) as dynamic modifications. Proteins identified by database retrieval were filtered using a false-discovery rate threshold of <1%. Differential expression analysis was performed using a volcano plot generated with the Chiplot online tool (https://www.chiplot.online) based on fold change and p-value (t-test) for each comparison group.

Gene synthesis, expression, and purification

All genes were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Sangon, Shanghai, China). The synthesized genes were cloned into the plasmid pET28a and heterologously expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). These genes include AmsqoD (gene locus tag: MASE_18005) and AmsqgH (gene locus tag: MASE_18025) of A. macleodii ATCC 27126, GH31_3 (gene locus tag: Ga0198492_01_4502455_4504773) of E. coli K-12, GH31_6 (gene locus tag: RA224_28300) of Achromobacter aegrifaciens, RdsqgA (gene locus tag: RD1_2308) and RddctP (gene locus: RD1_2315) of R. denitrificans OCh 114, GasqgA (gene locus tag: Ga0210579_114280) of G. antarcticus IMCC3135, MasqgA (gene locus tag: Ga0133504_112207) of M. aestuarii ST58-10, MhsqgA (gene locus tag: Ga0365646_2468) of M. hwangdonensis HDW-15, CtsqgA (gene locus tag: CTEN210_14965) of Chaetoceros tenuissimus NIES-3715, PpsqgA (gene locus tag: FVE85_4141) of Porphyridium purpureum CCMP 1328, SpsqgA+SpsqoD (gene locus tag: SPIL2461_LOCUS1475) of S. pilosum, AtsqgA (gene locus tag: AT4G17370) of Arabidopsis thaliana. Mutagenesis of AmSqoD, AmSqgH, and RdSqgA was performed using the Mut Express II Fast mutagenesis kit V2 (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Primers for mutagenesis are presented in Supplementary Data 15. All the bacteria were cultured to OD600 of approximately 0.6 in LB liquid medium with kanamycin resistance, and then transferred to a larger volume at 37 °C, 180 rpm to an OD600 of about 0.8. Subsequently, the bacteria were cooled to 16 °C, then isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Incubation was continued at 180 rpm for 16–18 h at 16 °C, and the bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Bacteria were resuspended in buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) and fragmented on ice with an ultrasonic disruptor (SM-650D), then centrifuged at 4 °C, 12,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm membrane and purified using AKTA pure (Cytiva, MA, USA) in combination with a HisTrap HP column (5 mL, Cytiva). Samples were loaded using 2% elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, followed by elution using an increasing gradient of elution buffers (4, 8, 10, 50%). The purified proteins were examined by SDS-PAGE on a commercial gel (precast protein plus gel, Hepes-Tris, 4–20%). Fractions containing the target protein were subjected to a desalting column (5 mL, Cytiva) with phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 8.0), filtered with 0.2-μm membrane, and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Enzymatic activity assays of AmSqoD, AmSqgH, and RdSqgA

The activity of AmSqoD towards SQ was measured using a colorimetric fuchsin assay17. A negative control omitting AmSqoD was also performed. The 6-dehydroglucose generated in the reaction was derivatized with DNPH and detected according to the following method. Mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in water and mobile phase B was 100% acetonitrile. The column was equilibrated with 95% A and 5% B for 5 min. The gradient conditions were: 5–50% B, 20 min; 50–95% B, 2 min; maintain 95% B, 2 min; 95–5% B, 1 min; maintain 5% B, 5 min. AmSqgH activity assays were conducted using PNPSQ78, PNPGlc, and PNPXyl as substrates. Reaction mixtures (200 µL) contained 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 10 mM PNPSQ (PNPGlc or PNPXyl), and 2 µM AmSqgH/GH31_3/GH31_6 with enzyme omitted in the control. Reactions were monitored at 405 nm using a plate reader (Tecan M200, Männedorf, Switzerland). The kcat /KM values of pH dependence for AmSqgH were measured for PNPSQ hydrolysis in 10 mM phosphate buffer at a range of pH values (5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 8.0) and 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 9.0). AmSqgH and RdSqgA activities were measured using SQGro or SQDG as a substrate. A 100 μL reaction containing 20 μM SQGro, 5 μM AmSqgH, or RdSqgA (add an additional 10 mM NAD+) in buffer (200 mM NH4HCO3, pH 7.5 for AmSqgH, pH 7.0 for RdSqgA) was incubated overnight at room temperature, respectively. Negative controls omitting enzyme were also performed. Reaction mixtures were dried, resuspended in CHCl3: MeOH: H2O (4: 6: 1, v/v/v), filtered through a 0.22-µm nylon membrane filter prior to LC-MS analysis. Measurement of AmSqgH and RdSqgA activity with SQDG was conducted according to the method of Speciale et al.31. SQDG (> 99%, 20 μL, 1 mg/ml in CHCl3: MeOH, 1: 1) in 200 mM NH4HCO3, 5% DMSO, pH 7.5 was incubated with 5 μM AmSqgH or RdSqgA (add an additional 10 mM NAD+) overnight at room temperature, respectively. Reaction mixtures were dried, resuspended in CHCl3: MeOH: H2O (4: 6: 1, v/v/v) and filtered prior to LC-MS analysis.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurement

SPR analyses for substrate binding protein (RdDctP) was performed using Biacore T200 optical biosensors equipped with research-grade CM5 sensor chips (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden). RdDctP was used at a concentration >1 mg/mL. Prior to analysis, a two-channel coupling was performed, with chip 1 channel as a closed coupling and 2 channels as a ligand coupling to eliminate refractive index variation, feed noise, and data drift. Pre-prepared 70% glycerol was normalized to the chip. Sodium acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5) was selected as the buffer for the next step according to the adsorption of ligands to the chip under different pH conditions. A series of concentrations of SQGro or SQ substrate were injected into the flow system and analyzed, respectively, and glucose as a negative control substrate.

Field sample collection

Seven separate cruises samples from seven oceanic regions were collected from July 2022 to August 2023. Samples from the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea were collected in July 2022, samples from the East China Sea were collected in August 2022, samples from the Jiulongjiang Estuary were collected in February 2023, samples from the Dongshan Bay were collected in July 2023, samples from the South China Sea were collected in August 2023, and samples from Central North Pacific were collected in July 2023. With the exception of samples collected from 3 to 500 meters depth in the central North Pacific, all other stations sampled water from depths of 3 to 5 meters. In each site, three parallel water samples were collected. Prior to sampling, seawater (1–3 L) was pre-filtered by a 200-µm a nylon screen and then was collected for particulate organosulfonates (SQDGs, SQ, SQGro, and DHPS) and POC samples using through 0.7-µm GF/F filter membrane (47 mm, Whatman, USA), which was pre-combusted at 480 °C for 5 h to remove carbon contamination. After sampling, the filters were immediately wrapped in pre-combusted aluminum foil and kept frozen at −20 °C until further extraction and analysis. Chlorophyll a content in the field were measured using Seabird SBE recorders (Sea-Bird Electronics Inc., USA). POC of the field samples was detected by elemental analyzer (vario EL Cube, Elementar, Germany) after 24 h of hydrochloric acid fumigation to remove inorganic carbon79. The base map was generated with Ocean Data View (v5.7.2) software.

Quantification of organosulfonates from cultured phytoplankton samples and field samples

For determination of intracellular metabolites SQGro and SQ from algae, the sample filters were cut into pieces and added to bead beating tubes containing 1 mL of a solvent mixture (MeOH: ACN: H2O, 2:2:1, v/v/v) along with 500 µL of silica beads, isotope-labelled taurine-D4 (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, USA) as an internal standard was added19. Three biological replicates of each sample were processed simultaneously. The FastPrep-24 homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, CA, USA) was used for grinding and homogenizing samples. Finally, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min and the extracted supernatants were filtered through a 0.22-µm membrane filter to a clean 1 mL glass vial for HPLC/MS analysis. The extraction steps of SQGro, SQ, DHPS in field samples are consistent with the above treatment.

The extraction of SQDG is based on the method of Bligh and Dyer80,81, with minor modifications. The collected filters of algae samples, along with the field sample filters, were cut into pieces and transferred to bead beating tubes containing 960 μL mixed solvent of MeOH: CH2Cl2: PBS (2:1:0.8, v/v/v) and approximately 500 μL of silica beads. 3-sn-Phosphatidylcholine (C16 PAF) (Merck, Germany) was added as an internal standard28. Then, the samples were shaken on a FastPrep-24 Homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, CA, USA) for three repetitions, then centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g. Sufficient CH2Cl2: PBS (1:1, v/v) was added to the collected supernatant to make the final solvent volume ratio MeOH: CH2Cl2: PBS (1:1:0.9, v/v/v). The samples were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, to allow phase separation. The CH2Cl2 layer, containing total lipids, was collected, and the MeOH: PBS was extracted twice with CH2Cl2. The extracts were dried under a flow of nitrogen. Finally, the sample were resuspended in CH2Cl2: MeOH (1:4, v/v) mixture and filtered through a 0.2-µm membrane filter to a clean 1 mL glass vial for subsequent analysis.

The concentration of SQGro, SQ, and DHPS of all samples were quantified using a Q Exactive high-performance liquid chromatography system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) with an ACQUITY UPLC BEH HILIC Column (130 Å, 1.7 µm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters, USA). A flow rate of 0.25 mL/min was used with two mobile phases A and B, A was acetonitrile and B was 10 mM ammonium acetate. The gradient was as follows: 0 min: 10% B, 15 min: 35% B, 16 min: 60% B, 20 min: 60% B, followed by 10 min of re-equilibration with 10% B and the injection volume was 2 μL. Quantification of SQGro and SQ was achieved with isotope-labelled taurine-D4 as an internal standard. One quality control sample was set for every 10 experimental samples. Data analyses were performed with Xcalibur software version 2.0.3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The concentration of SQDG of all samples was quantified using an Agilent 1290 Infinity II series UHPLC System (Agilent) coupled to an Agilent 6460 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent, CA, USA) via electrospray ionization (ESI), with an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 Column (130 Å, 1.7 µm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm, Waters, USA), flow rate of 0.25 mL/min with two mobile phases A and B, A was MeOH: H2O (85:15, v/v) and B was isopropanol, both containing 10 mM ammonium acetate. Mobile phases were proportioned as the following gradients: 0 min: 20% B, 1 min: 20% B, 8 min: 40%, 9 min: 80% B,11 min: 20% B, 14 min: 20% B, 17 min: 20% B, 20 min: 20% B. Column temperature was kept at 40 °C and the injection volume was 5 μL. Data analyses were performed with the Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis Software (B.07.00, Agilent Technologies, USA). One quality control sample was set for every 10 experimental samples. Quantitation was titrated using external calibration curves of commercially purchased standard SQDG (Larodan, Sweden) and normalized to the recovery of the internal standard.

Estimation of annual production of sulfoquinovosyl compounds

We estimated the annual production of sulfoquinovosyl compounds in the ocean based on their correlation with chlorophyll a concentrations and the assumption of a steady-state kinetic process. First, we calculated the proportion of sulfoquinovosyl carbon relative to POC, focusing specifically on SQDG molecules. Given variability in fatty acid chain composition, SQDGs in our dataset contained between 37 and 48 carbon atoms. Using the carbon content and the amount of individual SQDG lipoforms, we estimated the carbon contribution of SQDGs to the POC pool. This value was then multiplied by the global net primary productivity of 53 Pg C/yr43. To account for heterotrophic consumption ratio of algae-derived organic matter, we applied a 50% correction factor based on the study of Azam et al. (1982), resulting in an estimate of the annual production of sulfoquinovosyl compounds44.

Bioinformatic analysis

The online AlphaFold2 server was used to predict the protein structures of AmSqgH, AmSqoD and the eukaryotic proteins CtSqgA, PpSqgA, AtSqgA, and SpSqgA82. Crystals of RdSqgA were grown by the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method. The structure was determined by molecular replacement with an AlphaFold2 model (UniProt ID: Q167F5) and refined to a resolution of 1.8 Å (Supplementary Data 18). Molecular docking of SQGro into the catalytic domains of AmSqgH and RdSqgA was carried out using AutoDock 4. Gasteiger charges and all hydrogen atoms were added to the protein structures prior to docking. A genetic algorithm was employed for molecular docking, with the maximum number of evaluations set to medium. The conformations with the lowest binding energy were retained for further analysis and used to guide site-directed mutagenesis to verify their functions. Protein-ligand interaction patterns between SQGro and key residues were analyzed using the Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler online tool. For RdSqgA, molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the NAMD program on a Dell EMC PowerEdge R940xa server83. The complex was placed in an orthogonal box containing 9440 water molecules, 34 sodium ions, and 25 chloride ions. The sodium and chloride ions diffuse randomly under periodic boundary conditions. The solvated system underwent energy minimization over 1 ns, followed by 50 ns of molecular dynamics at 300 K. Molecular structures were visualized with Pymol 2.4 (Schrodinger, NY, USA). The representative electron density map for crystal structure is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. The refinement statistics are summarized in Supplementary Data 18.

Alteromonas genomes were obtained from GTDB v220. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using GTDB-Tk based on the marker genes of 120 bacteria strains84, with Pseudoalteromonas caenipelagi serving as the outgroup. Genes involved in the sulfo-SDO pathway were identified using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST)85, and genomes containing a contiguous cluster of the target protein-coding genes and retain the genomes that contain contiguous protein-coding genes (WP_014951127.1, WP_014951128.1, WP_014951129.1, WP_014951130.1, WP_014951131.1, WP_014951132.1, WP_014951133.1, WP_014951134.1, WP_014951135.1, and WP_014951136.1) were retained for further analysis. Representative homologs and paralogs of SqoD, SqgH, and SqgA were obtained from the NCBI reference sequence database. SQGro and SQ gene clusters were identified using the cblaster tool within the NCBI reference sequence database86. Representative sequences of all GH31 subfamilies were retrieved from the CAZy database (http://www.cazy.org/). Homologous eukaryotic SqgA sequences were obtained from UniProt and IMG databases (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot and https://img.jgi.doe.gov). The optimal model for phylogenetic analysis was determined using ModelFinder87. Phylogenetic trees for SqoD, SqgH, and eukaryotic SqgA were constructed using IQ-TREE under the WAG + G4 model with 1000 replicates88. A phylogenetic tree was constructed for bacterial genera containing sqgA using RAxML with the LG + IU+G4m model and 1000 bootstrap replicates89, based on a concatenated alignment of 11 single-copy orthologous genes (COG0087, COG0222, COG0292, COG0256, COG0049, COG0096, COG0051, COG0098, COG0085, and COG0691) shared among bacterial strains. The phylogenetic trees were visualized with Evolview v3 program90. Amino acid sequence alignment of RdSqgA and a eukaryotic representative was performed using MAFFT91, and the results were visualized with ESPript 3 (https://espript.ibcp.fr)92.

Sequences of SqgH and SqoD from A. macleodii ATCC 27126 and SqgA and SmoC from R. denitrificans OCh 114 were used as BLAST queries against the Tara Oceans metagenome (OM-RGC_v2_metaG), metatranscriptome (OM-RGC_v2_metaT), and Bohai Sea and Jiulongjiang Estuary metatranscriptomes36. Eukaryotic SqgA sequences were obtained from the Tara Oceans MATOU database35. An identity cutoff of 50% and 54% was applied to prokaryotic SqgH and SqgA, respectively, while a 60% cutoff was used for SqoD and SmoC. These thresholds were determined by analyzing the sequence alignments of these genes in various bacteria possessing the SQ metabolic gene cluster in this study. Additionally, a bit score cutoff of 204 was used for eukaryotic SqgA, consistent with our previous research19. Prokaryotic gene abundances were normalized to the median abundance of 10 universal single-copy genes (COG0012, COG0016, COG0018, COG0172, COG0215, COG0495, COG0525, COG0533, COG0541, COG0552) for both metagenome and metatranscriptome analyses93,94. Eukaryotic gene abundances were normalized to the median abundance of 10 single-copy marker genes (COG0522, COG0190, COG0097, COG0092, COG0191, COG0194, COG0187, COG0093, COG0096, COG0184)93. The relationship between Tara metadata and log-transformed genes relative abundance was analyzed by Spearman correlation in IBM SPSS Statistics 26. Significance was corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg approach95. Finally, data visualization and analysis were performed using Origin 2021 (OriginLab, MA, USA). The base maps were created using Tableau Desktop (v2019.4).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within this paper and its Supplementary Information files. The raw sequencing data of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI/Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under accession PRJNA1310569. The Proteomic data generated in this study have been deposited in the PRotromics IDEntifications (PRIDE) under accession PXD058686 and PXD058710. Biomolecular mass spectrometry data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29984182.v1). The model of structure generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30008725). Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this article have been deposited in Protein Data Bank database (https://www.rcsb.org/) under deposition numbers 8ZN9. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Cherabier, P. & Ferrière, R. Eco-evolutionary responses of the microbial loop to surface ocean warming and consequences for primary production. ISME J. 16, 1130–1139 (2022).

Ksionzek, K. B. et al. Dissolved organic sulfur in the ocean: biogeochemistry of a petagram inventory. Science 354, 456–459 (2016).

Wu, B. et al. Microbial sulfur metabolism and environmental implications. Sci. Total. Environ. 778, 146085 (2021).

Goddard-Borger, E. D. & Williams, S. J. Sulfoquinovose in the biosphere: occurrence, metabolism and functions. Biochem. J. 474, 827–849 (2017).

Kiene, R. P., Linn, L. J. & Bruton, J. A. New and important roles for DMSP in marine microbial communities. J. Sea Res. 43, 209–224 (2000).

Loi, V. V., Rossius, M. & Antelmann, H. Redox regulation by reversible protein S-thiolation in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 6, 187 (2015).

Teng, Z. J. et al. Acrylate protects a marine bacterium from grazing by a ciliate predator. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 1351–1356 (2021).

Sunda, W., Kieber, D. J., Kiene, R. P. & Huntsman, S. An antioxidant function for DMSP and DMS in marine algae. Nature 418, 317–320 (2002).

Ho, T.-Y. et al. The elemental composition of some marine phytoplankton. J. Phycol. 39, 1145–1159 (2003).

Moran, M. A. & Durham, B. P. Sulfur metabolites in the pelagic ocean. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 665–678 (2019).

Landa, M. et al. Sulfur metabolites that facilitate oceanic phytoplankton-bacteria carbon flux. ISME J. 13, 2536–2550 (2019).

Tang, K. & Liu, L. Bacteria are driving the ocean’s organosulfur cycle. Trends Microbiol. 31, 772–775 (2023).

Durham, B. P. et al. Cryptic carbon and sulfur cycling between surface ocean plankton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 453–457 (2015).

Durham, B. P. et al. Sulfonate-based networks between eukaryotic phytoplankton and heterotrophic bacteria in the surface ocean. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1706–1715 (2019).

Cook, A. M., Denger, K. & Smits, T. H. Dissimilation of C3-sulfonates. Arch. Microbiol. 185, 83–90 (2006).

Snow, A. J. D., Burchill, L., Sharma, M., Davies, G. J. & Williams, S. J. Sulfoglycolysis: catabolic pathways for metabolism of sulfoquinovose. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 13628–13645 (2021).

Ye, Z., Wei, Y., Jiang, L. & Zhang, Y. Oxygenolytic sulfoquinovose degradation by an iron-dependent alkanesulfonate dioxygenase. iScience 26, 107803 (2023).

Kaur, A. et al. Widespread family of NAD+-dependent sulfoquinovosidases at the gateway to sulfoquinovose catabolism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 28216–28223 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. Sulfoquinovose is a widespread organosulfur substrate for Roseobacter clade bacteria in the ocean. ISME J. 17, 393–405 (2023).

Anesi, A. et al. Comparative analysis of membrane lipids in psychrophilic and mesophilic freshwater dinoflagellates. Front. Plant. Sci. 7, 524 (2016).

Yongmanitchai, W. & Ward, O. P. Positional distribution of fatty acids, and molecular species of polar lipids, in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139, 465–472 (1993).

Goss, R. et al. The lipid dependence of diadinoxanthin de-epoxidation presents new evidence for a macrodomain organization of the diatom thylakoid membrane. J. Plant Physiol. 166, 1839–1854 (2009).

Harwood, J. L. & Nicholls, R. G. The plant sulpholipid-a major component of the sulphur cycle. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 7, 440 (1979).

Field, C. B. et al. Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281, 237–240 (1998).

Flombaum, P. et al. Present and future global distributions of the marine Cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9824–9829 (2013).

Van Mooy, B. A. S., Rocap, G., Fredricks, H. F., Evans, C. T. & Devol, A. H. Sulfolipids dramatically decrease phosphorus demand by picocyanobacteria in oligotrophic marine environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8607–8612 (2006).

Van Mooy, B. A. S. et al. Phytoplankton in the ocean use non-phosphorus lipids in response to phosphorus scarcity. Nature 458, 69–72 (2009).

Flores, E. et al. Bacterial and eukaryotic intact polar lipids point to in situ production as a key source of labile organic matter in hadal surface sediment of the Atacama Trench. Biogeosciences 19, 1395–1420 (2022).

Gašparović, B. et al. Particulate sulfur-containing lipids: production and cycling from the epipelagic to the abyssopelagic zone. Deep Sea Res. Pt. I. 134, 12–22 (2018).

Shibuya, I., Yagi, T. & Benson, A. A. Sulfonic acids in algae. In Microalgae and Photosynthetic Bacteria. (eds Japanese Society of Plant Physiologists) 627–636 (Tokyo University Press, 1963).

Speciale, G., Jin, Y., Davies, G. J., Williams, S. J. & Goddard-Borger, E. D. YihQ is a sulfoquinovosidase that cleaves sulfoquinovosyl diacylglyceride sulfolipids. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 215–217 (2016).

Sharma, M. et al. Oxidative desulfurization pathway for complete catabolism of sulfoquinovose by bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2116022119 (2022).

Abayakoon, P. et al. Structural and biochemical Insights into the function and evolution of sulfoquinovosidases. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 1266–1273 (2018).

Arumapperuma, T. et al. A subfamily classification to choreograph the diverse activities within glycoside hydrolase family 31. J. Biol. Chem. 299, 103038 (2023).

Villar, E. et al. The Ocean Gene Atlas: exploring the biogeography of plankton genes online. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W289–W295 (2018).

Han, Y. et al. Transcriptomic evidences for microbial carbon and nitrogen cycles in the deoxygenated seawaters of Bohai Sea. Environ. Int. 158, 106889 (2022).

Hou, S. et al. Benefit from decline: the primary transcriptome of Alteromonas macleodii str. Te101 during Trichodesmium demise. ISME J. 12, 981–996 (2018).

Pedler, B. E., Aluwihare, L. I. & Azam, F. Single bacterial strain capable of significant contribution to carbon cycling in the surface ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7202–7207 (2014).

López-Pérez et al. Genomes of surface isolates of Alteromonas macleodii: the life of a widespread marine opportunistic copiotroph. Sci. Rep. 2, 696 (2012).

García-Martínez, J., Acinas, S. G., Massana, R. & Rodríguez-Valera, F. Prevalence and microdiversity of Alteromonas macleodii-like microorganisms in different oceanic regions. Environ. Microbiol. 4, 42–50 (2002).

Roth Rosenberg, D. et al. Particle-associated and free-living bacterial communities in an oligotrophic sea are affected by different environmental factors. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 4295–4308 (2021).

Mazzotta, M. G. et al. Characterization of the metalloproteome of Pseudoalteromonas (BB2-AT2): biogeochemical underpinnings for zinc, manganese, cobalt and nickel cycling in a ubiquitous marine heterotroph. Metallomics 13, mfab060 (2021).

Johnson, K. S. & Bif, M. B. Constraint on net primary productivity of the global ocean by Argo oxygen measurements. Nat. Geosci. 14, 769–774 (2021).

Fuhrman, J. A. & Azam, F. Thymidine incorporation as a measure of heterotrophic bacterioplankton production in marine surface waters: evaluation and field results. Mar. Biol. 66, 109–120 (1982).

Williams, P. J. L. B. Heterotrophic Utilization of dissolved organic compounds in the Sea I. Size distribution of population and relationship between respiration and incorporation of growth substrates. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. Uk. 50, 859–870 (1970).

Wright, R. T. & Shah, N. M. The trophic role of glycolic acid in coastal seawater. I. Heterotrophic metabolism in seawater and bacterial cultures. Mar. Biol. 33, 175–183 (1975).

Becker, S. et al. Laminarin is a major molecule in the marine carbon cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 6599–6607 (2020).

Yagi, T. & Benson, A. A. Plant sulfolipid. V. Lysosulfolipid formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 57, 601–603 (1962).

Hashiro, S., Fujiuchi, K., Sugimori, D. & Yasueda, H. A novel galactolipase from a green microalga Chlorella kessleri: Purification, characterization, molecular cloning, and heterologous expression. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 1711–1723 (2018).

Behrendt, L. et al. Microbial dietary preference and interactions affect the export of lipids to the deep ocean. Science 385, eaab2661 (2024).

Scholz, S., Serif, M., Schleheck, D., Sayer, M. D. J. & Frithjof Christian, K. Sulfoquinovose metabolism in marine algae. Botanica Mar. 64, 301–312 (2021).

Liang, K. Y. H. F., Orata, D., Boucher, Y. F. & Case, R. J. Roseobacters in a sea of poly- and paraphyly: whole genome-based taxonomy of the family Rhodobacteraceae and the proposal for the split of the “Roseobacter clade” into a novel family, Roseobacteraceae fam. nov. Front. Microbiol. 12, 683109 (2021).

Moran, M. A. et al. Ecological genomics of marine Roseobacters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4559–4569 (2007).

Galí, M., Devred, E., Levasseur, M., Royer, S.-J. & Babin, M. A remote sensing algorithm for planktonic dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) and an analysis of global patterns. Remote Sens. Environ. 171, 171–184 (2015).