Abstract

Understanding dense matter hydrodynamics is critical for predicting plasma behavior in environments relevant to laser-driven inertial confinement fusion. Traditional diagnostic sources face limitations in brightness, spatiotemporal resolution, and in their ability to detect relevant electromagnetic fields. In this work, we present a dual-probe, multi-messenger laser wakefield accelerator platform combining ultrafast X-rays and relativistic electron beams at 1 Hz, to interrogate a free-flowing water target in vacuum, heated by an intense 200 ps laser pulse. This scheme enables high-repetition-rate tracking the evolution of the interaction using both particle types. Betatron X-rays reveal a cylindrically symmetric shock compression morphology assisted by low-density vapor, resembling foam-layer-assisted fusion targets. The synchronized electron beam detects time-evolving electromagnetic fields, uncovering charge separation and ion species differentiation during plasma expansion – phenomena not captured by photons or hydrodynamic simulations. We show that combining both probes provides complementary insights spanning kinetic to hydrodynamic regimes, highlighting the need for hybrid physics models to accurately predict fusion-relevant plasma behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inertial confinement fusion (ICF) recently achieved a historical milestone by reaching a target gain of unity1,2,3,4,5, reigniting optimism for fusion energy as a transformative and sustainable solution. A key challenge in ICF lies in understanding hydrodynamic instabilities during fuel compression, which are critical for the behavior of the burning plasma. To address this challenge, X-ray radiography has long been an essential tool in high-energy-density physics (HEDP)6,7,8, permitting the diagnosis of plasmas with densities normally exceeding ρ ≥ 1 g cm−3. High-energy laser facilities commonly irradiate metal, foam, or gas targets with UV laser beams to create X-ray backlighters9,10,11. While these sources coupled with streak cameras can capture many HED-relevant processes, they suffer from poor brightness due to low conversion efficiency, and limited spatiotemporal resolution typically exceeding Δx > 10 μm and Δt > 200 ps.

In parallel, electric and magnetic fields are increasingly recognized as playing significant roles in ICF environments12. The high temperatures and steep gradients mean that kinetic effects and electromagnetic fields may influence the system dynamics. In this sense, charged particle beam probes have also proven useful in diagnosing these complex interactions13. Although previous studies have proposed simultaneous imaging using different particle types14,15,16, such as X-rays and protons, they are similarly founded on traditional backlighter-based sources facing many limitations. Some of the challenges include restricted proton energy, spectral modulation, limited simultaneity between the probes, and low temporal resolution. Moreover, these methods typically rely on single-pulse, static configurations, limiting their ability to probe time-dependent dynamic systems. New methods that introduce complementary imaging probes could overcome some of these challenges, offering enhanced spatiotemporal resolution and the integration of field-sensitive diagnostics to study complex plasma interactions.

As a promising approach, laser wakefield acceleration (LWFA)17 has emerged over the past decades as a table-top source of relativistic electrons and X-ray pulses18,19,20,21,22,23,24. The betatron X-rays are ultrafast25,26, have a small source size27 enabling high spatial resolution, are brighter than conventional backlighter-based light sources28, and are suitable for high-repetition-rate imaging. Additionally, after propagation of a few cm the photons develop spatial coherence29, making them compatible with phase-contrast X-ray imaging (PCXI)30,31,32,33 techniques. Recent work has demonstrated betatron X-ray capabilities in high-resolution imaging34,35,36, X-ray absorption spectroscopy37,38, among other applications39. Moreover, LWFA electron beams have also been used as probes for laser-matter interactions40,41,42,43, aiming to develop an imaging technique that is sensitive to electromagnetic fields and has ultrafast timing resolution. However, previous LWFA studies have been limited exclusively to either a photon or electron probe, without integrating both to achieve a deeper understanding of the system in question.

In this work, we show that by utilizing both high-resolution X-ray photons and coordinated, electromagnetic field-sensitive electrons, one can reveal experimental details that would remain hidden from using a single particle type alone. In a “multi-messenger”-like approach akin to astronomy, one obtains insights about the whole of the interaction, revealing a picture that is greater than the sum of its parts44. Moreover, previous LWFA experiments have been restricted to single-shot, solid targets, and many have not been able to exploit the potential of high-repetition-rate laser capabilities in combination with liquid targets to image time-dependent dynamic systems.

In this study we capture the full dynamic evolution of a laser-heated ablating plasma and shock-compressed water column using pump-probe imaging of the interaction with both X-ray and charged-particle beams. X-rays capture the hydrodynamic shock development, while the relativistic electron beam measures the generated electromagnetic fields in a non-invasive radiographic scheme. Importantly, both particle sources are correlated in size and synchronized in time. While X-ray or electron beams alone provide an incomplete picture of the interaction, their combination offers a powerful and complementary tool. This approach reveals that detailed knowledge of target conditions along with a holistic view on laser-plasma evolution are needed for accurately modeling the complex plasma dynamics.

Results

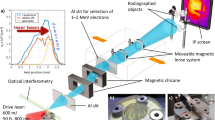

The experiments were performed at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory BELLA Center, where the Hundred Terawatt Thomson (HTT) dual beam system was used to drive both the laser wakefield accelerator and the laser target ablator, as shown in Fig. 1. In combination, a free-flowing liquid (water) target was designed that is capable of providing a bulk plasma (30 μm diameter stream) in vacuum. The custom-made water jet (“Water target”) is replenishable, clean, and suitable for laser-driven high-repetition-rate experiments. The HTT laser system (λ0 = 800 nm, 1 Hz repetition rate) consists of a main LWFA beamline with a linearly-polarized (1.5 ± 0.2 J), ultrafast (pulse duration 40 ± 5 fs FWHM, peak power 33 ± 6 TW) laser pulse focused by an f/20 off-axis parabola to a 20 ± 4 μm FWHM spot, incident on a gas target (“Gas target”) reaching on-target peak intensities of I = [7 ± 2] × 1018 W cm−2. A second shock-driver laser was obtained by splitting the main BELLA HTT beam and subsequently bypassing the compressor, thus generating a long high energy pulse (200 ps FWHM, 1.0 ± 0.2 J). The secondary pulse was focused on a spot of size 20 ± 5 μm along the x direction, perpendicular to the main beam axis z, and reaching intensities of I = [1.4 ± 0.2] × 1014 W cm−2. A variable delay stage on one of the beamlines allowed for precise control of timing between the shock-driver pulse with respect to the LWFA probes up to a maximum of 8 ns within the interaction. Laser pointing fluctuations of ± 15 μm RMS were mitigated by active feedback correction and by setting the focus of the long pulse laser past the water jet, thus employing a spot size larger than the target diameter (w0 ~60 μm) at its plane.

a The main ultrafast laser pulse is focused on the gas jet driving the plasma wakefield accelerator, generating relativistic electrons and ultrafast X-ray pulses. A secondary long laser pulse is focused on the liquid (water) target creating high-energy-density conditions and driving a hydrodynamic shock. The electron beam profile is recorded with a phosphor scintillating screen, and its spectrum is characterized downstream using a magnetic spectrometer. The betatron X-rays are recorded with an in-vacuum CCD camera, and their spectrum is characterized using a Ross filter wheel. b 529 shots taken continuously measuring the electron beam mean momentum, charge, and FWHM divergence angle. The shaded green bands denote the boundaries of scintillating screens. c Energy spectrum of the betatron X-ray source, recovered by imaging a Ross filter wheel. The uncertainty in the electron and X-ray beam spectra is obtained from the standard deviation of the critical energy across multiple shots.

Once the short laser pulse travels through the gas jet the ponderomotive force expels electrons away from high-field intensity regions leaving ion cavities and launching plasma waves on its wake. Due to the high-field gradients following the pulse, trapped electrons can be accelerated to relativistic velocities during the interaction. The oscillation of these electrons inside the ion bubbles in turn generates betatron X-ray pulses of ultrafast duration. In this sense, a laser wakefield accelerator generates synchronized X-rays and relativistic electrons, providing a unique tool for imaging unlike others where only one type of particle is available. In this study, the electron beam probe, having an average energy of 146 ± 7 MeV, was characterized using scintillating screens and a calibrated dipole magnet downstream (“Electron beam characterization”). The betatron X-rays were recorded using a cooled, in-vacuum, CCD camera (PI-MTE). The X-ray beam spectrum was characterized using a Ross pair filter wheel, resulting in Ec = 4.4 ± 0.7 keV, and a source size in the order of ~ 1 μm from the diffraction pattern of a sharp knife-edge (“X-ray beam characterization”). The spectra recorded for both probes are displayed in Fig. 1, and the experimental geometry chosen for multi-messenger imaging is further discussed in (“X-ray beam imaging”) and (“Electron beam imaging”).

Initially, when the long pulse laser interacts with the water, it deposits its energy over some range of densities below critical density, in the corona of the pre-formed plasma. This occurs mostly through inverse bremsstrahlung, but in addition through potential hot electron generation mechanisms45. Early preheating of the interior may also occur via laser shine-through effects46. Following laser energy deposition, electrons carry the heat to higher densities above critical density. Consequently, the dense liquid surface is quickly heated, leading to its ablation and subsequent expansion into a vacuum. In response to the large pressures generated at the ablation surface from the expansion of the material, a hydrodynamic shock wave is launched into the liquid target.

For low-Z laser-irradiated targets, reduced opacity minimizes the role of thermal radiation emission in the dynamics, and the low atomic number significantly reduces bremsstrahlung background from electron-target interactions compared to high-Z materials. However, in liquid water (ρ = 1 g cm−3), partial ionization increases opacity, making radiative losses more significant. At these ICF-relevant densities the evolution of the target is complex, involving hot-electron production, electron heat transport, radiation processes, shock-wave generation, and hydrodynamic expansion—all occurring within fractions of a nanosecond under typical experimental conditions. Nanosecond timescales fall within a regime where the complete physics of the interaction is hardly accessible to any single contemporary simulation. Our setup is then ideally suited for experimentally studying such complex dynamic systems, offering ultrafast and sub-micron resolution, nanosecond delay range, and dual probes sensitive to variation in both density and electromagnetic fields.

In this study, the evolution of the laser-water interaction was predicted using FLASH47, a radiation hydrodynamic simulation code (“FLASH simulations”). Projected density maps obtained from FLASH were post-processed with a Fresnel-Kirchhoff-based algorithm (“Fresnel-Kirchhoff algorithm”) to produce synthetic phase-contrast X-ray patterns as shown in Fig. 2. The first main result, displayed in Fig. 3 presents a time-series comparison between synthetically generated phase-contrast X-ray images and experimentally obtained betatron X-ray images, after preprocessing (“Fourier mask”). The laser-driven shock displays very similar features in both simulation and experiment (see Supplemenary Movie 1 and Supplementary Movie 2). The features observed in Fig. 3a include bright phase-contrast enhancement at the edges of the target, as well as a strong, dark, bow-shaped shock structure that grows in y-direction and propagates forward in x-direction. Smaller precursor signals ahead of the main shock are also appreciable and are examined later.

a Contrast between experimental betatron X-ray images and synthetic phase-contrast X-ray images at different time delays. b and c Lineouts in x direction averaged over 80 pixel rows in the y direction taken at the center of the simulation and experimental images, and stacked together horizontally to obtain a composite picture of the full temporal evolution of the interaction. Cyan dots indicate tracking of shock position.

To analyze these results, average lineouts were taken at the center of each image in the time series. The lineouts were then stacked together to create a composite image of the full interaction, shown in Fig. 3b, c. These aggregate images reveal the main shock breakout through the rear of the target around Δt ≅ 2 ns. The lineouts were subsequently analyzed to compare the shock velocity between simulation and experiment, which are comparable in magnitude as demonstrated in the analysis of Fig. 4.

The velocity measurement tracks the point of highest density in FLASH, and the minimum intensity feature in both synthetic and experimental phase-contrast X-ray images. The error bars of ± 4 μm in the experimental shock position reflect the spatial resolution of the imaging system, and consider the previous edge calibration with simulation density.

Measuring shock velocity is particularly important because it can provide information regarding the thermodynamic state of the material. By taking the frame of reference where the shock is at rest, one can define an upstream shock Mach number, \({M}_{u}={u}_{s}\sqrt{{\rho }_{1}/(\gamma {p}_{1})}\). Here us represents the shock velocity, ρ1 denotes the unshocked fluid density, p1 is the corresponding initial pressure, and the polytropic index value is assumed to be γ = 5/3. Such index is typical for fully ionized, weakly coupled HED systems where radiative effects are minimal48. For the present experimental parameters Mu ≈ 104, which is a clear indication of the strong-shock regime.

In order to calculate useful parameters for ICF environments, one can utilize the well-known Rankine-Hugoniot jump conditions and obtain predictions for the post-shock density and pressure in terms of Mu as,

and

The uncertainty in Mu can be substantial, however note that in the limit when Mu ≫ 1, the physical limit for density jump in a polytropic gas approaches ρ2/ρ1 = (γ + 1)/(γ − 1) ≈ 4, while the pressure grows infinitely, and is strongly dependent on the shock velocity measured experimentally. For the analysis shown in Fig. 4, utilizing us ≈ 20 μm/ns, the resulting post-shock pressure on target is p2 = 3 − 4 Mbar, comparable in magnitude to that at the Earth’s core. This pressure scales with laser intensity as \({p}_{2}\approx 6.1{I}_{14}^{2/3}{\lambda }_{u}^{-2/3}\) Mbar. Where I14 is the intensity in units of 1014 W cm−2 and λu is the laser wavelength in micrometers48.

Moreover, one can utilize the calculated pressure p2 and the measured shock velocity us to obtain a useful prediction for the ion temperature. By taking \({p}_{2}=({Z}_{2}+1){k}_{B}{T}_{2}{\rho }_{2}/(A{m}_{p})\) and taking the strong shock limit one finds

Assuming the electrons are non-degenerate, they fully equilibrate with the ions, and ignoring Coulomb modifications to the pressure, the immediate postshock temperature of the ions before they equilibrate with the electrons can be found by setting Z2 = 0, corresponding to the average ionization state of the post-shock ions. Then Eq. (3) results in an ion temperature of Ti,2 = 4.7 eV.

Notably, although early time agreement with simulations was good regarding the shock propagation velocity, the simulated shock structures did not fully match the experimental measurements at intermediate times. In Fig. 5a, panel (1) represents a simple 3D (or standard 2D) FLASH simulation of a cylindrical water target heated by a laser pulse. Interestingly, ten-shot averaged panel (3) and single-shot panel (4) show X-ray images of the shocked target at near maximum compression at Δt ~ 1.0 ns. These display an apparent rear-driven shock structure that is different from conventional 2D, and simple 3D, FLASH simulations.

a Comparison panels with Meijering filter (“Meijering filter”) at Δt ~ 1.0 ns. Panel (1) is an x–y 2D slice from 3D FLASH simulation with no vapor, panel (2) is an x–y 2D slice from 3D FLASH simulation with surrounding vapor profile, panel (3) is a ten-shot-averaged image taken with betatron X-rays, 4) single-shot image taken with betatron X-rays. b z–x 2D slices from 3D FLASH simulation comparing density and pressure maps as a function of time for two cases: in panel (1) water target without surrounding vapor and in panel (2) water target with surrounding vapor profile.

Analysis of the plasma conditions indicates that it is unlikely to observe a strong shock reflection at the rear interface. Instead, a much better agreement with the structure produced experimentally was achieved in Fig. 5a panel (2), by incorporating a low-density layer surrounding the target, approximating the vapor expected from water evaporation in vacuum. Including the low-density layer in the simulations enhances thermal transport around the water column, resulting in more uniform heating of the jet’s exterior and producing a cylindrical shock49 and symmetric compression morphology closely matching the experimental observations.

To illustrate this effect, Fig. 5b displays 2D slices from 3D simulations of the density and pressure profiles taken at the midpoint, x − z plane, of the water cylinder. Panel (1) shows a simple water target without surrounding vapor, where the laser-driven shock is strong and predominantly one-sided. In contrast, if a vapor density profile falling as ∝ 1/r from the surface is introduced in panel (2) a key difference in compression morphology is observed. The partially ionized vapor blanket provides a low-opacity, low-density medium in which electrons are able to transport energy more efficiently around the surface of the target. This leads to more uniform density and pressure profiles, and to the generation of a cylindrically symmetric shock structure.

To obtain a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, consider that the laser energy at the peak of the pulse is deposited in ionized water electrons below the critical density nc. This creates a high-temperature region of order ~ 1 keV as shown in the simulations of Fig. 6, from which electrons transport heat above nc into the dense matter50. Free electrons in the low-density corona region are not able to fully escape from the electrostatic forces imposed by the ions, but are free to move around the surface of the target traveling a significant distance before depositing their energy. For instance, let us compare the mean-free-path of a 1 keV thermal electron carrying heat in the plasma region below n ≤ nc to that of an electron in the dense solid n ≈ ne0. For the low density region with nc ~ 1021 cm−3 we obtain λmfp ~ 20 μm, in the order of the diameter of the stream. By contrast, for the high-density region n0 ~ 1023 cm−3 the mean-free-path is λmfp ~ 0.2 μm. As a result, the heat flow within the target would be localized, while thermal transport in the vapor layer would be highly nonlocal.

The experimental observations in Fig. 5a panel (3) and panel (4) have led us to better understand the compression morphology of the target and the importance of accurately modeling the experimental conditions. To support this interpretation with observational evidence, we now make use of the relativistic electron beam probe generated by the laser wakefield accelerator. The nonlocality of the heat transport and the presence of energetic electrons around the interaction region, result in the production of electric (through the strong pressure gradients) and magnetic (through current flows) fields in the plasma surrounding the water target. These field-generating mechanisms are well known but are often not included in fluid-based hydrodynamic codes, as electric fields are typically precluded by enforced quasineutrality. Unlike the X-ray probe, the LWFA electron beam will be sensitive to path-integrated deflections caused by electric and magnetic fields along its trajectory. These perturbations are captured downstream on the profile imager, forming an image of the interaction.

Using this approach, the electron beam probe was used to capture the evolution between the long pulse laser and the water stream, as shown in Fig. 7a (see Supplementary Movie 3). Bright features displayed on the scintillator screen indicate accumulation of probe electrons from focusing fields, while dark features would typically represent absence of electrons from defocusing fields. The first noticeable feature in the time-series is a bright channel in the laser propagation direction, which persists for approximately the pulse duration of 200 − 300 ps and focuses the electron probe. The fields are likely to be electric, arising from the pressure gradient caused by the long pulse laser ionization and heating. Notably, the observation of such early-time ionization channel across both sides of the water jet further supports the idea of nonlocal heat transport, hot electron generation, and a symmetrically ablated target observed with the X-rays in Fig. 5. Although the channel forming on both sides of the liquid jet might suggest laser transmission through the water, it is important to recall that the long-pulse laser beam is larger than the water column diameter, allowing a significant portion of the laser energy to bypass the target.

a Time-series of electron beam profile perturbed by electromagnetic fields around the laser-water interaction region recorded on phosphor screen. b Integrated line profiles for the plasma channel and plasma cloud features for both the difference image (I/I0 − 1), and recovered electric fields ∫ ∣E∣dl. Error bands in the recovered field magnitude account for chromatic effects and uncertainty in the electron beam probe energy: two limiting cases were considered 1) with Elow = 20 MeV and 2) with Ehigh = 150 MeV. c Illustration of electric field recovery from electron beam radiographic images (“Field recovery method”). The panel includes the radiographic normalized image I, the difference image (I/I0 − 1), and recovered field magnitude ∫ ∣E∣dl. Dashed circles highlight two distinct cloud features, an Oxygen plasma (inner circle) and a Hydrogen plasma (outer circle).

The second prominent feature observed with the electrons is a dark plasma cloud expanding from the center, indicating the presence of complex, strong electromagnetic fields. While this dark structure might initially be interpreted as defocusing fields, the absence of a plausible physical mechanism from simulations in Fig. 8 suggests the fields are most likely overfocusing the probe. Moreover, the sharp bright circular ring surrounding the plasma cloud indicates the presence of caustics in the image. Although caustics complicate the quantitative analysis of the fields, lower bounds on their strengths and key features of their topology may still be extracted using a field recovery method (“Field recovery method”). From Fig. 7c, we infer integrated fields on the order of ∫ Edl ~ 104 V or ∫ Bdl ~ 10−4 T ⋅ m. In the case of electric fields, a simple estimate using E ~ ∇ P/ene ~ ∇ (kBTe/e) would imply hot electrons with temperatures on the order of keV.

a Recovered projected electric fields ∫ Exdl and ∫ Eydl from experimental data. b Projected electric fields ∫ Exdl and ∫ Eydl obtained from 3D simulation. c Slice of electric fields Ey and Ex obtained from 3D simulation. The simulation fields are obtained following the equation E ~ ∇ P/ene, where P is the pressure field and ne is the electron number-density field output from the FLASH code.

More importantly, a time-dependent morphological understanding of the fields is acquired from Fig. 7, where different plasma species can be identified from the radiographic images. First, there is a dark inner cloud bounded by a bright ring, likely caused by strong overfocusing fields from an oxygen ion plasma. Second, a fainter dark outer ring, which may be attributed to a hydrogen ion (protons) plasma marking the boundary of its expansion into vacuum. At the plasma edge, a sheath field forms due to the separation of electrons and protons by an amount of around the local Debye length. This sheath field balances the thermal motion and exerts a positive force on the electrons in the negative radial direction, focusing (or overfocusing) the probe. The timescale of expansion indicates that the dark outer ring must originate from an expanding proton plasma defocusing the probe, as its expansion is too slow to be attributed exclusively to defocusing electrons given the working temperatures.

Within this framework, the expansion velocity analysis in Fig. 9 presents both a slower oxygen plasma (O+, inner cloud) with average atomic number Z = 8 and velocity of uO = 191 ± 21 μm/ns, as well as a second hydrogen plasma species (H+, outer dark ring) with a much faster characteristic expansion speed of uH = 731 ± 39 μm/ns and much lower average atomic number of Z = 1. The speed of this plasma boundary is consistent with protons moving with the same average energy as the slower expanding oxygen ions. Protons are expected to be accelerated from the surface of a hot plasma51, however, this feature is not present in the single-fluid simulations. To approximate a water molecule, the FLASH plasma fields use a single mean atomic number of Z = 3.33 expanding at a velocity of uF = 260 μm/ns, and falling between the recorded oxygen and hydrogen curves.

For FLASH simulations the measurement tracks the field edge position of the expanding plasma plume. For electron beam radiographic images the measurement tracks annular features expanding in time, where two distinct plasma species components are identified: (1) hydrogen ions plasma and (2) oxygen ions plasma. The uncertainties in the expansion radii are defined as ± 15 μm for H+ feature and ± 30 μm for O+ feature following experimental observations and standard deviation across multiple shots.

Hence, the relativistic electron beam probe is able to provide evidence for an expanding hot plasma surrounding the water column not visible by the X-rays, as well as to capture the evolution of different ion species not present in the simulation. More importantly, the dual-sided near-isotropic ablating plasma, observed with the electron beam probe, would support the model of a cylindrically symmetric compression shock morphology observed with the X-rays.

The absence of hot electron populations in FLASH simulations is particularly relevant in light of our observations. Hot electrons generated during laser-plasma interactions can travel significant distances, driving non-local heat transport and depositing energy into the surrounding vapor layer. These findings underscore the need for advanced diagnostic systems in future HED experiments, as well as hybrid simulations that incorporate kinetic effects alongside radiation hydrodynamics.

Discussion

We have shown that combining information in tandem from both an ultrafast X-ray probe and a relativistic electron beam probe from LWFA enables a multi-messenger technique that reveals insights inaccesible to either probe alone. This approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of the physics involved in high-intensity laser interactions with dense matter. While betatron X-ray imaging captures laser-driven shock hydrodynamics with submicron resolution, electron beam radiography offers a complementary perspective on electromagnetic field time evolution. LWFA, in contrast to other radiation sources, generates simultaneous electron and X-ray beams with good beam properties, intrinsic femtosecond time resolution, excellent absolute timing and synchronization with themselves as well as other lasers. These advantages make it a unique tool not available at synchrotron or X-ray free-electron laser facilities, where only one type of particle probe is typically available for users.

While the experimentally measured shock velocity reasonably agreed with 2D and simple 3D fluid simulations, discrepancies in the shock compression morphology were observed. The multi-messenger probe revealed a more holistic picture of the laser-water interaction, revealing uniform heating of the target and a cylindrically symmetric shock compression structure. By refining the simulation model to more precisely account for the target’s initial conditions, such as vacuum-induced water evaporation, a more accurate understanding of the interaction was obtained.

This vapor-assisted, cylindrically symmetric compression phenomenon can be compared, in some ways, to low-density foam-layer-assisted inertial confinement fusion targets52,53, concerning advanced hohlraum designs with reduced wall-motion in ICF. The ablative expansion morphology of laser-heated materials is a crucial factor in optimizing hohlraum cavities for ICF, where low-density foam liners help manage the expansion of the heated hohlraum walls and decrease the development of instabilities. Previous experiments have demonstrated effectiveness in mitigating wall motion that interferes with a fully spherically-symmetric compression of the D-T fusion target through liners with densities on the order of ρ = 0.01−0.04 g cm−3. In an analogous sense, the low density water vapor layer in this experiment with ρ0 = 0.01 g cm−3 serves to assist the single laser ablator to compress the target with a cylindrically-symmetric morphology. At later times, the X-ray probe further captures complex dynamics consistent with the onset of post-shock plasma instabilities, as expected by the experimental conditions. Some of these features are visible in Fig. 3c at t > 3 ns, as signals not discerned in the simulation model. A detailed analysis of these features is underway and will be presented in future work.

Utilizing the electron beam probe further revealed quasi-isotropic expanding plasma fields on both sides of the target, capable of identifying distinct plasma species expanding at characteristic thermal velocities—features not accessible by photon-based imaging. These observations not only advance our understanding of laboratory plasma physics, but also underscore discrepancies between radiation hydrodynamic simulations and real laser-plasma interactions, where complex phenomena such as ion species differentiation and strong electromagnetic fields are evident from femtosecond to nanosecond timescales.

All measurements were repeated across multiple shots (typically 5–10 per delay time) under the same conditions. Despite the fluid nature of the target, key features such as shock evolution, compression morphology, and field topology were reasonably reproduced across the dataset. That said, the dual-probe setup does involve certain trade-offs, including spatial constraints on sample and detector placement, characterization of each probe, as well as added complexity in target engineering.

While this configuration may not directly replicate full-scale direct-drive ICF experiments, the purpose of this work is to demonstrate the diagnostic power of LWFA based multi-messenger probes and to set the path forward for more sophisticated, high-repetition-rate platforms using liquid targets. These insights may also motivate the design of future smaller-scale HED science experiments, which could one day be adapted to large-scale fusion facilities such as the National Ignition Facility, Laser Mégajoule, or OMEGA.

Methods

X-ray beam imaging

The experimental geometry was carefully designed to enable a propagation-based phase-contrast X-ray imaging configuration. To properly choose a source-to-object distance R0 and object-to-detector distance R1, the coherence length L⊥ = R0/kσ was estimated for a collection of uncorrelated emitters of wavenumber k and source size σ 27. To resolve features of order σ at the image plane, the coherence length must exceed the source size (L⊥ > σ). Rearranging, the source-to-object distance can be estimated as R0 > kσ2, which in terms of the photon energy in units of keV and microns is

For 5 keV X-rays and a σ = 2 μm source size, R0 > 10 cm ensures that the coherence length is larger than the source size.

The broadband polychromatic spectrum of a betatron source supports propagation-based phase contrast since, to first order in the paraxial approximation, the phase-contrast pattern is independent of wavelength when the effective Fresnel number is larger than unity (NF,eff > 1), where

Here λ is the weighted mean wavelength, R = R0 + R1, \(M=({R}_{0}+{R}_{1})/{R}_{0}\) is the magnification, σobj is the size of the smallest object feature, and PSF represents the detector’s point-spread function as described in ref. 54. Therefore, the condition NF,eff > 1 holds true given our experimental setup configuration with source-to-object distance R0 = 16 cm, object-to-detector distance R1 = 580 cm, and beam divergence of a few tens of mrad.

X-ray beam characterization

The X-ray radiation spectrum was characterized using a Ross filter wheel, as described in ref. 55. The filter wheel consisted of wedges made of different materials and thicknesses to selectively attenuate parts of the spectrum. By analyzing the transmitted intensity map and fitting a synchrotron-like spectrum56, the critical energy of the X-ray beam was determined to be Ecrit = 4.4 ± 0.7 keV.

The size of the X-ray source was estimated using a sharp “knife-edge” placed in the beam path. The intensity profile of the transmitted beam was measured and fitted to the expected Fresnel diffraction pattern produced by a Gaussian source interacting with a half-plane. This analysis yielded an upper bound for the X-ray source size of σ ≤ 1 μm.

To obtain a nominal background signal, we recorded images without gas or water flow and averaged over 10 shots to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. The background was then subtracted from each signal image on a shot-by-shot basis. To protect the in-vacuum CCD camera and further reduce background signals, a filter assembly was placed upstream from the detector. This consisted of a 60 μm aluminum foil, a 25 μm kapton film, and a 36 μm mylar layer, which together served to attenuate residual laser light, suppress plasma self-emission, and shield the detector from debris.

Electron beam imaging

The geometry for electron-beam imaging shared the same source-to-object distance as the X-ray imaging setup, \({R}_{0}^{*}={R}_{0}\) but used a significantly shorter object-to-detector distance \({R}_{1}^{*}=141\) cm. This configuration was selected to capture the full electron beam profile on a phosphor scintillating screen located downstream in the chamber, prior to the dipole magnet. This imaging configuration provided a radiographic picture of the electron beam profile and its perturbation from the interaction fields.

By employing distinct object-to-detector distances for the X-ray and electron-beam imaging setups, this configuration provides a dual perspective of the interaction with different magnifications. The electron radiography setup allowed for a broader field of view of the beam profile, complementing the higher-resolution perspective offered by the X-ray imaging.

Electron beam characterization

The relativistic electron beam produced by the wakefield accelerator was characterized using a magnetic spectrometer57, comprising a 1.5 − 3 T electromagnet and a 1 T permanent dipole magnet along the beamline. The magnetic fields dispersed the electrons based on their momenta, projecting their trajectories onto a series of Lanex scintillating screens, from which the electron-induced fluorescence was imaged onto an array of 12-bit CCD cameras.

The beam was characterized by mapping the electron positions on the screens to particle tracking simulations through the experimentally measured magnetic field. This process allows for precise beam energy, divergence, and charge calibration as described in ref. 58.

The mean energy of the electron beam for the experiment was 146 ± 7 MeV as shown in Fig. 1, with a pointing divergence of 7.8 ± 1 mrad in the x-direction and 3.4 ± 0.8 mrad in the y-direction. The mean charge of the beam was 24 ± 4 pC.

For the specific analysis of field recovery from electron radiographs, a representative beam energy of E0 = 44 MeV was selected. This lower energy reflects operating conditions where the beam was intentionally detuned to increase divergence and maximize field sensitivity across the imaging region. Additionally, this choice allows chromatic deflection effects to be better accounted for when measuring field magnitudes.

Gas target

The laser plasma accelerator employed ionization injection59 to generate a relativistic electron beam by focusing the high-power laser pulse into a 3 mm mixed gas jet60 composed of 99.5% helium and 0.5% nitrogen. The supersonic gas jet utilized a fast solenoid valve (Parker Pulse Valve) synchronized and triggered alongside the high-power beamline. A voltage-controlled regulator allowed precise tuning of the gas jet’s backing pressure, enabling adjustment of the gas plume density within the range n0 ∈ [2.1, 2.8] × 1018 cm−3. To characterize the laser-plasma interaction, a Mach-Zehnder interferometer was utilized, incorporating a frequency-doubled probe beam oriented perpendicular to both the gas jet and the high-power laser line. This configuration enabled synchronized diagnostics of the plasma density profile61.

Water target

A custom-made cylindrical liquid water jet flowing in vacuum was employed as the target for the experiment, drawing inspiration from existing systems such as bulk liquid targets used in time-of-flight mass spectrometers62 and thin liquid sheets63.

The water was delivered to the chamber by a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) pump connected to 1/16” OD stainless steel tubing (0.03” ID). The jet nozzle consisted of cleaved Polymicro (Molex) capillary tubing with 30 μm ID and 360 μm OD. The water was delivered at a flow rate kept between 1–2 mL min−1, maintained constant by the HPLC pump.

The water collector assembly included a conical copper head with a top aperture of d ≈ 500 μm, designed to capture the water stream. To prevent ice formation during the alignment procedure, the collector head was heated by embedded miniature cartridge heaters (Thorlabs, 15 W). The collector assembly is connected to a reservoir via standard vacuum components.

The alignment of the water jet stream with the collector was achieved using picomotors for small adjustments along the x, y, and z directions. Two orthogonal cameras positioned outside the vacuum chamber monitored the procedure until stable operation was achieved after pump-down.

After alignment, chamber pressures as low as 10−5 Torr could be achieved using > 1000 L s−1 turbo pumps and a liquid nitrogen cold trap. The stable water jet was subsequently aligned with the long pulse laser beam using translation stages supporting the whole assembly.

FLASH simulations

Three-dimensional (3D) radiation-hydrodynamic simulations were performed using FLASH47 to predict the evolution of the laser-plasma interaction. FLASH is a multi-dimensional, radiation hydrodynamic simulation code based on the Eulerian approach. It features dynamic block adaptive meshing, treats multiple materials, includes electron heat conduction and related physics, transports radiation via multigroup diffusion, and deposits laser energy by tracing rays in 3D. Although FLASH simulations accurately model the fluid dynamics, they do not include electric (E) and magnetic (B) fields nor treat hot electron populations.

The simulations utilized a 3D Cartesian coordinate system consisting of a cylindrical plasma target with a radius of r0 = 15 μm and mass density ρt = 1 g cm−3. A surrounding chamber plasma where r > r0 was initialized with a much lower initial mass density ρc. Two different density profiles for the chamber plasma were explored: 1) a standard target with constant ρc = 10−6 g cm−3 throughout the domain, and 2) an evaporative target so that \({\rho }_{c}={\rho }_{0}({r}_{0}/\sqrt{{{{{\bf{r}}}}}^{2}})\) with ρ0 = 10−3 g cm−3 following a decaying distribution as r increases.

Both the target and chamber plasmas were modeled with the same effective atomic number Zeff,t = Zeff,c = 3.33 and average atomic mass Aeff,t = Aeff,c = 6.0. The plasmas were similarly initialized at room temperature Tt,0 = Tc,0 = 290 K, and the multi-group flux-limited diffusion coefficient was chosen to be f = 0.17, considering our laser parameters and ref. 64. The equation of state for both plasmas was calculated using the PrOpacEOS code.

The shock-driver laser pulse in the simulations was modeled with λ = 0.8 μm using a truncated Gaussian profile for its intensity with FWHM = 40 μm. The laser power deposited into each cell is calculated based on inverse bremsstrahlung, which depends on the local electron number density gradients and the local temperature gradients. The laser pulse was defined in sections using a piecewise linear function, where each section is associated with a time-power pair. These pairs ensure that the total energy in the pulse (1 J) is delivered over the total time window (220 ps).

Image processing

Fourier mask

We applied a custom filter in the Fourier domain to process the experimental X-ray data, reducing undesired high spatial frequencies and thereby increasing the signal-to-noise ratio. The method involves constructing a mask that selectively filters spatial frequencies based on a combination of radial and elliptical criteria.

Given an input image I(x, y) of dimensions Nx × Ny, the two-dimensional Fourier transform \(\widetilde{I}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})={{{\mathcal{F}}}}\{I(x,y)\}\) is computed first, where kx and ky represent the spatial frequency components in the x and y directions, respectively.

Next, a radial frequency component \(K={({k}_{x}^{2}+{k}_{y}^{2})}^{1/2}\) and an elliptical frequency component \({K}_{el}={({a}^{2}{k}_{x}^{2}+{b}^{2}{k}_{y}^{2})}^{1/2}\) are defined. The final frequency-space mask M(kx, ky) is then constructed by incorporating these two terms as:

where \({K}_{\max }=\pi\) is the maximum spatial frequency, and N is a parameter that controls the sharpness of the mask. To avoid singularities when Kel = 0, we set the corresponding values in the mask to 1. Moreover, prior to applying the frequency-space mask the image is rotated by an angle θ to align it with the vertical orientation using bilinear interpolation. In this work, we selected a = 0.5, b = 2.0, and N = 16 to optimize the quality of the processed experimental images.

The constructed mask in frequency-domain is then applied to the image as \({\widetilde{I}}_{masked}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})=\widetilde{I}({k}_{x},{k}_{y})\cdot M({k}_{x},{k}_{y})\), and the inverse Fourier transform is used to recover the masked image in real space:

Fresnel-Kirchhoff algorithm

To model the expected image pattern from a phase-contrast imaging system, we follow a common approach outlined by Born and Wolf65 and applied in past work66,67, which consists of solving the Fresnel-Kirchhoff integrals numerically to obtain the expected complex wave-field distribution \(\widetilde{u}\) after propagation from an initial point at the source, to a point P = (x, y) in the detector plane. In this context, the real “pure” pattern I is given by

where I0 is the incoming intensity distribution at the sample.

Assuming that the effective Fresnel number is larger than unity, the complex-valued wave-field distribution can be simplified utilizing the paraxial approximation. This approximation yields a final expression for the complex-valued wave-field distribution in Fourier space as given by ref. 54,

where u and v are the transverse spatial frequencies corresponding to x and y coordinates, respectively. Equation (9) can be solved using a fast Fourier transform (FFT) algorithm to obtain the pure pattern I, which can then be convolved with the source size σ to obtain the real phase-contrast pattern in the detector. Here T(Mu, Mv) is the Fourier transform of the object transfer function \(t({{{\bf{P}}}})=\exp [i\phi ]\), where the phase induced ϕ is complex-valued and depends on the material properties as

For X-rays crossing a sample, the index of refraction is less than unity and has the form n = 1 − δ − iβ. The phase map is then calculated using Eq. (10) and the following projected distributions obtained from radiation hydrodynamic simulations,

and

where δ and β are the real and imaginary components of the refractive index and are expressed as,

and,

where re is the classical electron radius, NA is the Avogadro number, ρ is the mass density, Aj are the atomic number and the atomic weight of the j-th element of molecule, \({f}_{j}^{{\prime} }\) is the real part of the dispersion factor, ωp is the density-dependent plasma frequency, and ν is the collisions rate factor.

Finally, to account for the polychromaticity of the source, the resulting image can be weighted and summed according to the spectrum distribution of the source

where w(E) is the energy-dependent weighting factor obtained from the source spectrum.

Meijering filter

The Meijering filter is an image processing technique to accurately quantify and segment neurite-like traces in fluorescence microscopy images, as described by Meijering et al.68. In this work the algorithm is adapted for the detection of shocked traces in the sample, which deviate from the nominal un-shocked image.

For the implementation of the algorithm, the modified second-order derivatives of the image are calculated by convolving it with the second-order derivatives of the Gaussian kernel. Specifically, if f mathematically represents the image and G denotes the normalized Gaussian kernel, the second-order derivative of the image at position x = (x, y) can be computed as,

where

and the derivative directions i and j can be either x or y.

Next, the eigenvectors and eigenvalues are computed in the Meijering algorithm by using a modified second-derivative matrix given by,

where α is a parameter which needs to be optimized. The normalized eigenvectors vi(x) and their corresponding eigenvalues λi(x) of the standard Hessian second-derivative matrix are then obtained as,

and

In this way, the algorithm calculates the eigenvectors of the Hessian to determine the similarity of an image region to the shocked traces in the sample. The Meijering filter was applied to both experimental and simulation X-ray images using its default parameters as given by scikit-image filters package.

Field recovery method

Following the technique described by Kugland et al.69, the field recovery method begins by assuming that the perturbed object is located at a distance R0 from the particle (electron) source, with the detection screen situated at a distance R1 from the object. Generally, R1 ≫ R0, and R0 ≫ a, where a is a characteristic spatial scale of the field in question. In a Cartesian geometry, the ideal image I0 at the object plane for an undisturbed electron beam is described by the coordinates (x0, y0), while the real image I in the detector is described by the coordinates (x, y), such that x = x0 × M and y = y0 × M, where M = (1 + R1/R0) is the geometric magnification.

After the electrons traverse the electromagnetic fields, they are deflected by angles αx and αy. The coordinates of the real image, as described by the electrons’ trajectories, can be approximated, when αx, y are small, by

Therefore, the objective of the algorithm is to determine the deflection angles αx and αy, as they can be related to the path-integrated electric or magnetic fields present at the interaction region by the following expressions,

and

Finally, the disturbed beam at the detector plane I(x, y) can be then obtained by the following relation,

Here, ∣∂(x, y)/∂(x0, y0)∣ is the absolute value of the determinant of the Jacobian matrix that relates the object and image planes and can is described by

To solve this equation, we assume that α = [αx, αy, 0] is small and that the object-to-image coordinates follow a linear mapping. Additionally, all electrons’ trajectories are assumed to be rotation-less such that ∇ × α = 0. For this regime, the deflection angles can be obtained from a potential field ϕ so that

For convenience, we introduce the following normalization: \(\widetilde{x}=x/{w}_{x}\), \(\widetilde{y}=y/{w}_{y}\), \(\widetilde{{\alpha }_{i}}={\alpha }_{i}L/{w}_{i}\), \(\widetilde{{{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}}}=\widetilde{\nabla }\widetilde{\Phi }\), and \(\widetilde{{I}_{0}}={I}_{0}/{M}^{2}\) where wi is width of the beam at the image plane. The Jacobian, described by Kugland et al., can then be rewritten as,

This leads to the final equation, which is solved numerically,

Under strong-field conditions, or in the presence of low-energy electrons, large deflection angles αx,y can lead to overlapping beam trajectories, and the formation of caustics in the radiograph. This affects the one-to-one mapping between the source and detector coordinates, making the relationship between x0 and x nonlinear and the correspondence between I0 and I non-unique. Moreover the broad energy spectrum of the electron beam can further introduce chromatic effects in the deflection response, these should not be large as described in ref. 42. Nevertheless, key features of the field topology, its evolution in time, and approximate lower bounds on field strength may still be robustly extracted using this method.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Michigan Deep Blue Data repository under (https://doi.org/10.7302/d62b-w84770). This repository includes the raw X-ray and electron beam imaging datasets, simulation results, and scripts used for image processing. Additional analysis code and simulation outputs are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zylstra, A. B. et al. Burning plasma achieved in inertial fusion. Nature 601, 542–548 (2022).

Kritcher, A. L. et al. Design of inertial fusion implosions reaching the burning plasma regime. Nat. Phys. 18, 251–258 (2022).

Rubery, M. S. et al. Hohlraum reheating from burning NIF implosions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 065104 (2024).

Hurricane, O. A. et al. Energy principles of scientific breakeven in an inertial fusion experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 065103 (2024).

Abu-Shawareb, H. et al. Achievement of target gain larger than unity in an inertial fusion experiment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 065102 (2024).

Casner, A. et al. Progress in indirect and direct-drive planar experiments on hydrodynamic instabilities at the ablation front. Phys. Plasmas. 21, 122702 (2014).

Wan, W. C. et al. Observation of single-mode, Kelvin-Helmholtz instability in a supersonic flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 5001 (2015).

Kuranz, C. C. et al. How high energy fluxes may affect Rayleigh-Taylor instability growth in young supernova remnants. Nat. Commun. 9, 1564 (2018).

Workman, J. et al. Phase-contrast imaging using ultrafast x-rays in laser-shocked materials. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 81, 10E520 (2010).

Park, H.-S. et al. High-energy k alpha radiography using high-intensity, short-pulse lasers. Phys. Plasmas 13, 056309 (2006).

Fournier, K. B. et al. Efficient multi-keV x-ray sources from Ti-doped aerogel targets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 730, 223–232 (2004).

Li, C. K. et al. Measuring e and b fields in laser-produced plasmas with monoenergetic proton radiography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 135003 (2006).

Schaeffer, D. B. et al. Proton imaging of high-energy-density laboratory plasmas. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 045007 (2023).

Ostermayr, T. M. et al. Laser-driven x-ray and proton micro-source and application to simultaneous single-shot bi-modal radiographic imaging. Nat. Commun. 11, 6174 (2020).

Orimo, S. et al. Simultaneous proton and X-ray imaging with femtosecond intense laser driven plasma source. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 46, 5853 (2007).

Nishiuchi, M. et al. Laser-driven proton sources and their applications: femtosecond intense laser plasma driven simultaneous proton and x-ray imaging. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 112, 042036 (2008).

Tajima, T. & Dawson, J. M. Laser electron accelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 43, 267 (1979).

Mangles, S. P. D. et al. Monoenergetic beams of relativistic electrons from intense laser–plasma interactions. Nature 431, 535–538 (2004).

Geddes, C. G. R. et al. High-quality electron beams from a laser wakefield accelerator using plasma-channel guiding. Nature 431, 538–541 (2004).

Faure, J. et al. A laser–plasma accelerator producing monoenergetic electron beams. Nature 431, 541–544 (2004).

Leemans, W. P. et al. Gev electron beams from a centimetre-scale accelerator. Nat. Phys. 2, 696–699 (2006).

Hafz, N. A. M. et al. Stable generation of gev-class electron beams from self-guided laser–plasma channels. Nat. Photonics 2, 571–577 (2008).

Wang, X. et al. Quasi-monoenergetic laser-plasma acceleration of electrons to 2 GeV. Nat. Commun. 4, 1–9 (2013).

Gonsalves, A. et al. Petawatt laser guiding and electron beam acceleration to 8 GeV in a laser-heated capillary discharge waveguide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 084801 (2019).

Ta Phuoc, K. et al. Demonstration of the ultrafast nature of laser produced betatron radiation. Phys. Plasmas 14, 080701 (2007).

Grigoriadis, A., Andrianaki, G., Tatarakis, M., Benis, E. P. & Papadogiannis, N. A. Betatron-type laser-plasma x-ray sources generated in multi-electron gas targets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 131110 (2021).

Kneip, S. et al. Bright spatially coherent synchrotron x-rays from a table-top source (vol 6, pg 980, 2010). Nat. Phys. 7, 737 (2011).

Albert, F. et al. Laser wakefield accelerator based light sources: potential applications and requirements. Plasma Phys. Controlled Fusion 56, 084015 (2014).

Shah, R. C. et al. Coherence-based transverse measurement of synchrotron X-ray radiation from relativistic laser-plasma interaction and laser-accelerated electrons. Phys. Rev. E 74, 045401 (2006).

Snigirev, A., Snigireva, I., Kohn, V., Kuznetsov, S. & Schelokov, I. On the possibilities of X-ray phase contrast microimaging by coherent high-energy synchrotron radiation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 66, 5486–5492 (1995).

Wilkins, S. W., Gureyev, T. E., Gao, D., Pogany, A. & Stevenson, A. W. Phase-contrast imaging using polychromatic hard x-rays. Nature 384, 335–338 (1996).

Fourmaux, S. et al. Single shot phase contrast imaging using laser-produced betatron X-ray beams. Opt. Lett. 36, 2426–2428 (2011).

Vargas, M. et al. X-ray phase contrast imaging of additive manufactured structures using a laser wakefield accelerator. Plasma Phys. Controlled Fusion 61, 054009 (2019).

Wood, J. C. et al. Ultrafast imaging of laser driven shock waves using betatron x-rays from a laser wakefield accelerator. Sci. Rep. 8, 11010 (2018).

Cole, J. M. et al. High-resolution μct of a mouse embryo using a compact laser-driven X-ray betatron source. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 6335–6340 (2018).

Hussein, A. E. et al. Laser-wakefield accelerators for high-resolution X-ray imaging of complex microstructures. Sci. Rep. 9, 3249 (2019).

Mahieu, B. et al. Probing warm dense matter using femtosecond X-ray absorption spectroscopy with a laser-produced betatron source. Nat. Commun. 9, 3276 (2018).

Kettle, B. et al. Extended x-ray absorption spectroscopy using an ultrashort pulse laboratory-scale laser-plasma accelerator. Commun. Phys. 7, 247 (2024).

Albert, F. & Thomas, A. G. R. Applications of laser wakefield accelerator-based light sources. Plasma Phys. Controlled Fusion 58, 103001 (2016).

Schumaker, W. et al. Ultrafast electron radiography of magnetic fields in high-intensity laser-solid interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 015003 (2013).

Wan, Y. et al. Direct observation of relativistic broken plasma waves. Nat. Phys. 18, 1186–1190 (2022).

Zhang, C. J. et al. Capturing relativistic wakefield structures in plasmas using ultrashort high-energy electrons as a probe. Sci. Rep. 6, 29485 (2016).

Zhang, C. J. et al. Femtosecond probing of plasma wakefields and observation of the plasma wake reversal using a relativistic electron bunch. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 064801 (2017).

Mészáros, P., Fox, D. B., Hanna, C. & Murase, K. Multi-messenger astrophysics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 585–599 (2019).

Kruer, W. L. The Physics of Laser Plasma Interactions. CRC Press: Boca Raton, (2019)

Bradley, D. K. et al. Early-time “shine-through” in laser irradiated targets. Laser Interact. Relat. Plasma Phenom. 9, 323–334 (1991).

Fryxell, B. et al. Flash: An adaptive mesh hydrodynamics code for modeling astrophysical thermonuclear flashes. Astrophysical J. Suppl. Ser. 131, 273 (2000).

Drake, R. P. High-Energy-Density Physics: Foundation of Inertial Fusion and Experimental Astrophysics. Springer: Cham, (2018).

Laso Garcia, A. et al. Cylindrical compression of thin wires by irradiation with a joule-class short-pulse laser. Nat. Commun. 15, 7896 (2024).

Delettrez, J. Thermal electron transport in direct-drive laser fusion. Can. J. Phys. 64, 932–943 (1986).

Wilks, S. C. et al. Energetic proton generation in ultra-intense laser-solid interactions. Phys. Plasmas 8, 542–549 (2001).

Moore, A. S. et al. Experimental demonstration of the reduced expansion of a laser-heated surface using a low density foam layer, pertaining to advanced hohlraum designs with less wall-motion. Phys. Plasmas 27, 082706 (2020).

Bhandarkar, S. et al. Fabrication of low-density foam liners in hohlraums for NIF targets. Fusion Sci. Technol. 73, 194–209 (2018).

Barbato, F. et al. Quantitative phase contrast imaging of a shock-wave with a laser-plasma based x-ray source. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11 (2019).

King, P. M. et al. X-ray analysis methods for sources from self-modulated laser wakefield acceleration driven by picosecond lasers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 90, 033503 (2019).

Esarey, E., Shadwick, B. A., Catravas, P. & Leemans, W. P. Synchrotron radiation from electron beams in plasma-focusing channels. Phys. Rev. E 65, 056505 (2002).

Tsai, H.-E. et al. Control of quasi-monoenergetic electron beams from laser-plasma accelerators with adjustable shock density profile. Phys. Plasmas 25, 043107 (2018).

Nakamura, K. et al. Electron beam charge diagnostics for laser plasma accelerators. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top.—Accelerators Beams 14, 062801 (2011).

McGuffey, C. et al. Ionization induced trapping in a laser wakefield accelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 025004 (2010).

Zhou, O. et al. Effect of nozzle curvature on supersonic gas jets used in laser–plasma acceleration. Phys. Plasmas 28, 093107 (2021).

Plateau, G. et al. Wavefront-sensor-based electron density measurements for laser-plasma accelerators. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 81, 033108 (2010).

Charvat, A., Lugovoj, E., Faubel, M. & Abel, B. New design for a time-of-flight mass spectrometer with a liquid beam laser desorption ion source for the analysis of biomolecules. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75, 1209–1218 (2004).

Koralek, J. D. et al. Generation and characterization of ultrathin free-flowing liquid sheets. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–8 (2018).

Chen, Z. H. et al. Effect of non-local transport of hot electrons on the laser-target ablation. Phys. Plasmas 30, 062710 (2023).

Born, M., Wolf, E. Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation, Interference and Diffraction of Light. Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, (2013).

Arfelli, F. et al. Low-dose phase contrast x-ray medical imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 43, 2845 (1998).

Olivo, A. & Speller, R. Experimental validation of a simple model capable of predicting the phase contrast imaging capabilities of any x-ray imaging system. Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 3015 (2006).

Meijering, E. et al. Design and validation of a tool for neurite tracing and analysis in fluorescence microscopy images. Cytom. Part A: J. Int. Soc. Anal. Cytol. 58, 167–176 (2004).

Kugland, N. L., Ryutov, D. D., Plechaty, C., Ross, J. S. & Park, H.-S. Invited article: Relation between electric and magnetic field structures and their proton-beam images. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 101301 (2012).

Balcazar, M. D. et al. Multi-messenger dynamic imaging of laser-driven shocks in water using a plasma wakefield accelerator dataset [Data set], University of Michigan - Deep Blue Data (2025).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (US DOE) Office of Science Fusion Energy Sciences Grant No. DE-SC0020237, Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 the LaserNetUS initiative at the Berkeley Lab Laser Accelerator (BELLA) Center, and partially supported under Contract No. FWP-100884: LaserNetUS Management. The work was also supported by US DOE National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) Center of Excellence under Cooperative Agreement No. DE-NA0003869, the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program with grant agreement No. 682399, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under subcontract No. B645096. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory is operated by Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, for the US DOE NNSA under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344. Certain optomechanical components and translation stages in Fig. 1 incorporate CAD geometry provided by Thorlabs, Inc. (Part Nos. UPH4, TR2, RS4P) and MKS, Inc. (Part Nos. 8302-UHV-KAP, MFA-CCV6, 9066-XYZ-R-V, UTS100PPV6) assembled using SolidWorks software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D.B.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. H.-E.T.: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. T.O.: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—review & editing. P.C.: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing—review & editing. F.A.: Writing - review & editing. Q.C.: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. C.C.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. G.M.D.: Resources, Writing—review & editing. Z.E.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. E.E.: Writing—review & editing. C.G.R.G.: Investigation, Resources, Project administration, Writing—review & editing. E.S.G.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. B.G.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. A.G.: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—review & editing. S.H.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. R.J.: Data curation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. B.K.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. P.K.: Methodology, Writing - review & editing. K.K.: Writing—review & editing. N. Lemos: Writing - review & editing. E.L.: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Y.M.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. S.P.D. Mangles: Writing—review & editing. J. Nees: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing. I.M.P.: Methodology, Writing - review & editing. C.S.: Writing—review & editing. R.A.S.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. M.T.: Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing—review & editing. J.V.T.: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing—review & editing. A.V.: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. A.G.R.T.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. C.C.K.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Michael Tatarakis who co-reviewed with Ioannis Tazes; Victor Malka and Benoi^t Mahieu for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balcazar, M.D., Tsai, HE., Ostermayr, T.M. et al. Multi-messenger dynamic imaging of laser-driven shocks in water using a plasma wakefield accelerator. Nat Commun 17, 529 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67224-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67224-3