Abstract

Steroids are among the most valuable and widely used pharmaceuticals. The cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc) is critical for steroid metabolism and hormone biosynthesis. While mammalian eukaryotic P450scc enzymes are well-characterized, bacterial counterparts remain underexplored despite their industrial promise and potential contributions to bacterial steroid catabolism. Here, we identify a series of CYP204 family P450 enzymes, widely distributed across diverse steroid-degrading bacterial species, that catalyze the side-chain cleavage of cholesterol, phytosterol, and cholestenone to produce pregnenolone and progesterone. Unlike mammalian enzymes, which exhibit strict cholesterol specificity, bacterial P450scc enzymes display relaxed substrate specificity, preferentially converting cholestenone to progesterone—a key precursor in steroid drug semi-synthesis. Structural and mechanistic analyses demonstrate that CYP204 enzymes employ a flexible, dual-regioselective C–H activation mechanism distinct from the sequential hydroxylation of mammalian P450scc enzymes. Iterative saturation mutagenesis identified critical residues for side-chain cleavage, improving catalytic efficiency up to 6.5-fold, and computational analyses clarified sequence–function relationships. This finding of bacterial P450scc enzymes not only underscores their potential function in bacterial steroid catabolism but also lays a foundation for promising biocatalytic strategies for pregnenolone and progesterone synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

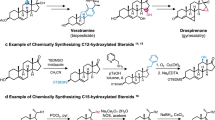

Steroid hormones, such as pregnenolone (PREG) and progesterone (PROG), are indispensable in medicine due to their anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, and endocrine effects, serving as critical precursors for glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, and sex hormones used in clinical therapies1,2,3,4,5,6. In mammals, the precursor to all steroid hormones, PREG is synthesized from cholesterol (CHL) via a well-characterized three-step reaction catalyzed by the cytochrome P450 enzyme mCYP11A1, also known as the side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc)7,8,9. This process involves sequential hydroxylation of cholesterol to 22R-hydroxycholesterol (22R-HC), then to 20R, 22R-dihydroxycholesterol (20R,22R-DHC), followed by C20–C22 bond cleavage to yield PREG (Fig. 1a)10,11,12, which is subsequently converted to PROG by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/isomerase13. Notably, mCYP11A1 exhibits narrow substrate specificity and shows negligible activity toward converting cholestenone (CHO)9. Beyond mammals, plant P450scc enzymes belong to the CYP87A family, which is involved in cardenolide biosynthesis, and have recently been identified14,15,16. (Fig. 1b). In microorganisms, steroids are ubiquitous in natural environments and serve as vital growth substrates, making microbial steroid catabolism pivotal for both pathogenicity and biotechnological applications17,18,19. However, the equivalent P450scc enzymes in prokaryotes remain unexplored.

In addition to their central role in hormone biosynthesis, PREG and PROG, particularly the latter, also serve as key precursors in the industrial synthesis of a significant number of steroid drugs (over 200)1,4. Traditional production of PROG relies on a 7-steps semisynthetic process from diosgenin, known as Marker degradation, but the low yield and environmental concerns have spurred interest in biotransformation alternatives20,21. Recent approaches combining bacterial conversion of phytosterols with semisynthetic methods show promise for producing PROG, though they still require multiple chemical steps—such as converting intermediates like 21-hydroxy-20-methyl-pregn-4-ene-3-one (4-HBC) into PROG—or even more complex reactions to generate PREG4. In comparison, the P450scc pathway provides an environmentally sustainable and direct synthesis route for both target compounds. However, eukaryotic P450scc enzymes are less suitable for industrial biocatalysis due to membrane association, poor heterologous expression, and restricted engineering potential from high sequence conservation22,23,24,25,26,27. In contrast, prokaryotic P450s offer superior biotechnological applicability through their soluble nature and compatibility with industrial bacterial hosts.

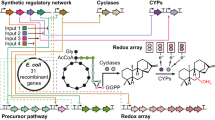

In this study, we report the discovery and characterization of a series of bacterial P450scc enzymes through phylogeny-guided genome mining from steroid-degrading microorganisms, which exhibits a substrate preference for CHO as well as CHL and phytosterols (Fig. 1c). Unlike the strict, sequential C22 to C20 hydroxylation of mammalian CYP11A1, these bacterial enzymes employ a flexible, simultaneous C20 and C22 hydroxylation mechanism, enabled by an expanded substrate cavity that accommodates diverse sterol conformations. Structure-guided engineering of CYP204A5 further significantly enhances the enzyme’s catalytic efficiency. These findings provide valuable insights into bacterial steroid catabolism and highlight their potential for more sustainable and scalable steroid drug production.

Results

Discovery of bacteria-derived P450scc

The bacterial steroid degradation pathway typically involves multiple oxidative hydroxylation steps, largely catalyzed by various P450 enzymes that participate in steroid catabolic pathways and play an important role in steroid degradation17,28. Leveraging the soluble expression and industrial application potential of bacterial P450s, we developed a strategy for mining P450 hydroxylases from steroid-degrading bacterial genomes using a phylogeny-guided genome mining approach (Fig. 2a). While we previously identified a fungal C14α-hydroxylase (CYP14A) that efficiently catalyzes C14-hydroxylation29, its membrane-bound nature limits its broad application. To address this limitation, we initially aimed to identify soluble bacterial P450s capable of C14-hydroxylation, expanding the potential for industrial biocatalysis. Given that lanosterol demethylase initiates its catalytic cycle by hydroxylating the C14-methyl group30, we hypothesize that phylogenetically related bacterial P450s may adopt similar substrate-binding conformations and are capable of hydroxylating the C14 of sterols. To test this, we compiled a local database comprising the genomes of 265 putatively steroid-degrading bacteria18. Using the C14-demethylase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP51 (MTCYP51) as a probe30, we performed BLAST searches and constructed a phylogenetic tree with 1,000 homologous sequences (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Data 1). Eight candidates (P450-A1 to P450-A8) from clades near CYP51, varying in homology and origin, were selected for further study (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1).

a A strategy for mining P450s for steroid functionalization from steroid-degrading bacterial genomes. (b) The structures of the steroid substrates used in this study. c Phylogenetic tree of potential bacteria-derived P450scc proteins. The phylogenetic tree was built from the protein sequences of P450-A8 (CYP204A2, accession number: CCA90294.1, blue) and its homologs with amino acid sequence identity greater than 40%, using the Maximum Likelihood Method. The CYP204A2 homologous proteins chosen for this analysis are colored red.

The corresponding genes were synthesized with codon optimization and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Data 2). To assess their activity, we tested five steroidal substrates (Fig. 2b)—PROG, CHO, 4-HBC, 4-androstenedione (4-AD), and lanosterol—using ferredoxin/ferredoxin reductase pairs (SpFdx/SpFdR from spinach31 and SeFdx1499/FdR0978 from Synechococcus elongatus PCC 794232, Supplementary Table 2) to support catalysis. Among the screened candidates, only P450-A8 exhibited clear activity in the presence of the Synechococcus redox system when CHO was used as the substrate (Supplementary Fig. 3). LC-MS analysis revealed a major product with a mass shift of −70 Da, along with three minor products, presumed to be mono- and di-hydroxylated derivatives, showing mass shifts of +16 Da and +32 Da, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). By scaling up the reaction, we isolated the major product, which was identified as PROG through NMR analysis. These findings demonstrate that P450-A8 unexpectedly catalyzes a sterol side-chain cleavage reaction.

We next evaluated whether P450-A8 could cleave the side chains of other sterols, including CHL, desmosterol, campesterol, and β-sitosterol, the latter two being major components of phytosterols (Fig. 2b). LC-MS analysis confirmed that P450-A8 catalyzes the side-chain cleavage of CHL, desmosterol, and β-sitosterol, producing PREG as the primary product (Supplementary Fig. 4), albeit with lower efficiency—particularly for desmosterol and β-sitosterol—compared to CHO. These results establish that P450-A8 has a much broader substrate specificity than the eukaryotic P450scc, mCYP11A19.

A comprehensive search of the NCBI genome database was conducted using P450-A8 as the query sequence to evaluate the distribution of this enzyme across bacterial species. This analysis identified 192 protein homologs exhibiting greater than 40% sequence identity with P450-A8. These sequences predominantly originate from two prokaryotic phyla: Pseudomonadota and Bacillota (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Data 1). Based on phylogenetic analysis, we selected nine homologous sequences from different clades, which were subsequently codon-optimized and synthesized for further study (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Data 2). According to cytochrome P450 nomenclature33,34, P450-A8 and the nine additional identified homologs were classified as members of the CYP204 family. Consequently, P450-A8 was renamed CYP204A2, while the remaining nine homologous proteins were designated CYP204A3, CYP204A4, CYP204A5, CYP204A6, CYP204B2, CYP204C1, CYP204D1, CYP204E1, and CYP204F1.

These nine proteins, except for CYP204C1 and CYP204D1, were successfully expressed in E. coli in soluble form (Supplementary Fig. 5). Activity assays of the soluble proteins were performed using CHO as the substrate. Notably, CYP204A3, CYP204A4, CYP204A5, CYP204A6, and CYP204B2 demonstrated the ability to catalyze their side-chain cleavage, producing PROG (Fig. 3a). Phylogenetic analysis demonstrates that bacterial P450scc, mammalian P450scc, and plant P450scc enzymes cluster into distinct evolutionary clades, indicating their independent evolutionary origins (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 4). This phylogenetic divergence underscores the convergent evolution of steroid side-chain cleavage functionality across diverse biological kingdoms. Given the lack of detailed investigation into the catalytic mechanisms of these bacterially derived P450scc enzymes, further mechanistic studies are necessary to fully elucidate their functional properties.

Determination of the hydroxylated intermediates produced by bacterial-derived P450scc

The bacterial P450scc enzymes exhibited variability in both protein expression levels and catalytic efficiency (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). Among them, CYP204A5 demonstrated superior catalytic efficiency (1.1-fold better than CYP204A2, 5.3-fold better than CYP204A3, 10.2-fold better than CYP204A4, 13.2-fold better than CYP204A6 and CYP204B2, Supplementary Fig. 6) and was selected as the primary candidate for further biochemical characterization and mechanistic investigation. Additionally, it showed higher catalytic activity with CHO than with CHL; Thus, CHO was chosen as the model substrate for mechanistic studies of CYP204A5.

LC-MS analysis of the CYP204A5-catalyzed reaction identified two monohydroxylated intermediates and one dihydroxylated intermediate, along with the primary product PROG, consistent with the observations for P450-A8 (CYP204A2) (Fig. 3a). According to the mechanism of mammalian P450scc, these hydroxylations are speculated to occur at C20 and C22. To characterize these intermediates, we chemically synthesized four monohydroxylated cholestenone standards—20S-hydroxycholestenone (20S-HCO), 20R-hydroxycholestenone (20R-HCO), 22S-hydroxycholestenone (22S-HCO), and 22R-hydroxycholestenone (22R-HCO) (Fig. 4a). Their structures and absolute configurations were confirmed by NMR or X-ray diffraction (Supplementary data 3). Comparing their retention times on LC-MS revealed that the two monohydroxylated compounds are indeed 20S-HCO and 22R-HCO, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7).

a The structures of the hydroxylated substrates of CHO used in this study. b UPLC analysis of in vitro assays of CYP204A5 with monohydroxylated substrates of CHO in the presence of SeFdx1499/FdR0978 and NADPH at 254 nm. c The structures of the hydroxylated substrates of CHL used in this study. d UPLC-MS analysis of in vitro assays of CYP204A5 with hydroxylated substrates of CHL in the presence of SeFdx1499/FdR0978 and NADPH. The peaks with an asterisk represent unidentified dihydroxylation products of CHL that are not 20R,22R-DHC.

To further determine whether they are true intermediates, 20S-HCO and 22R-HCO, along with the other two monohydroxylated compounds, 20R-HCO and 22S-HCO, were tested for cleavage activity by CYP204A5. The results showed that only 20S-HCO and 22R-HCO were further converted into PROG (Fig. 4b), whereas 20R-HCO and 22S-HCO were unreactive, supporting 20S-HCO and 22R-HCO as intermediates in the CYP204A5 catalytic process. Interestingly, the catalyzed reactions with CHO, 20S-HCO and 22R-HCO as substrates consistently produced a dihydroxy intermediate with the same retention time (Fig. 4b). Subsequent scale-up reactions, NMR characterization, and comparison with the C3-oxidized product of commercially available 20R, 22R-dihydroxycholesterol (20R,22R-DHC) generated by cholesterol oxidase (ChoM) identified the dihydroxy intermediate as 20R, 22R-dihydroxycholestenone (20R, 22R-DHCO) (Supplementary Fig. 7), in which the configuration of the hydroxyl groups at C20 and C22 are identical to those in 20S-HCO and 22R-HCO.

We further investigated whether CYP204A5 exhibits the same specificity toward cholesterol-derived substrates by testing chemically synthesized 20S-hydroxycholesterol (20S-HC) and 20R-hydroxycholesterol (20R-HC) (Fig. 4c), along with commercially sourced 22R-HC, 22S-hydroxycholesterol (22S-HC), and 20R, 22R-dihydroxycholesterol (20R,22R-DHC), for side-chain cleavage activity. Biochemical assays revealed that CYP204A5 can effectively converts 22R-HC, 20R,22R-DHC and 20S-HC into PREG, but exhibits no activity toward 20R-HC. Although 22S-HC can be converted into several hydroxylated products, their retention time didn’t align with 20R,22R-DHC, suggesting a nonspecific hydroxylation (Fig. 4d). These observations are consistent with the results from cholestenone-based substrate assays, establishing that bacterial and mammalian P450scc enzymes share a dihydroxylation-driven C–C bond cleavage mechanism but differ in their sequential hydroxylation steps and regioselectivity. Unlike mammalian P450scc (CYP11A1), which strictly follows a sequential C22 → C20 hydroxylation pattern, bacterial P450scc enzymes (CYP204 family) exhibit a more flexible two-step hydroxylation mechanism, where the initial hydroxylation can occur at either the C-20 or C-22 position (Fig. 1c). This bidirectional catalytic activity could potentially enhance C–C bond cleavage efficiency compared to mCYP11A1. Notably, both hydroxylation steps, along with the subsequent C-C bond cleavage through a dihydroxylated intermediate, are likely mediated by Compound I (Cpd I) as the reactive oxygen species, analogous to the mechanism observed in mammalian P450scc9,10,11,12.

Structural characterization of P450scc

To elucidate the catalytic mechanism of bacterial P450scc, we first pursued structural characterization. Although crystallization of CYP204A5 was unsuccessful, we successfully determined the crystal structure of its homolog CYP204A3 at 2.1 Å resolution (PDB: 9WAT; Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Fig. 8). Sequence alignment revealed 70.3% identity between CYP204A3 and CYP204A5. This high conservation corresponds to functional similarity: while exhibiting reduced activity, CYP204A3 processes identical substrates and generates the same intermediates as CYP204A5 (Fig.3a and Supplementary Fig. 9), strongly suggesting a shared catalytic mechanism.

a The overall structures of CYP204A3. b Docking structure of CHO (cyan) with CYP204A3 (light pink) and residues around substrate-binding pocket within 5 Å. The blue color highlights the corresponding amino acid residues of CYP204A5. The distances between heme-Fe of CYP204A3 and C20/22 of CHO are indicated with yellow dash lines. c The distance from iron-oxo species to C20 (light pink) and C22 (cyan) of CHO over the course of a 100 nanosecond MD simulation for CYP204A3. d WebLogo of the residues around substrate-pocket with 5 Å for several bacteria-derived P450sccs (CYP204 A2-A6, CYP204B2). e The relative activity of CYP204A3 and its mutants in catalyzing the generation of PROG from CHO. All data points were obtained in three replicate experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted. ND: not detected. f The relative activity of CYP204A5 and its mutants in catalyzing the generation of PROG from CHO. All data points were obtained in three replicate experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The CYP204A3 structure adopts the characteristic trigonal-prism fold observed in other bacterial P450s (e.g., P450cam35, NasF505336, and PtmB37). Notably, AlphaFold3’s prediction for CYP204A3 showed remarkable accuracy (RMSD = 0.488 Å) relative to our experimental structure (Supplementary Fig. 10), validating its application for modeling CYP204 family proteins. Notably, the F-G loop showed significant structural differences, likely attributable to its inherent flexibility. Despite extensive crystallization attempts, we were unable to obtain substrate-bound structures of CYP204A3. Therefore, we docked CHO and CHL into its active site, respectively (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 11), revealing different substrate-binding pocket architecture and interaction patterns compared to the mammalian CYP11A1-cholesterol complex (PDB: 3N9Y)9. Leveraging structural insights from P450scc and computational docking, we conducted targeted alanine scanning mutagenesis (Supplementary Fig. 12), where observed reductions in activity supported the predicted binding mode.

Comparative molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the CYP204A3 and CYP11A1 complexes revealed greater fluctuations in the RMSD of both the ligand and the active sites in the CYP204A3 complex (Supplementary Fig. 13), indicating greater active site plasticity. This enhanced conformational flexibility may enable CYP2043 to have a broader range of substrates than mammalian P450sccs. MD simulations of the docked model of CYP204A3-CHO to showed that C20 and C22 remained consistently positioned near the iron-oxo center of compound I (Cpd I) throughout the simulation (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 14). The distances between the Cpd I and C20/C22 were measured at 4.04 ± 0.41 Å and 4.10 ± 0.45 Å, respectively, favoring hydroxylation and subsequent side-chain cleavage. Similar substrate positioning favoring hydroxylation was observed in the docked model of CHO with a CYP204A5 AlphaFold3-predicted structure (Supplementary Fig. 15). This spatial arrangement enables simultaneous hydroxylation of C20 and C22, distinguishing bacterial P450scc from the sequential hydroxylation mechanism of mammalian P450scc. Analysis of the docked model reveals potential ligand-receptor interactions mediated by several key amino acid residues within 5 Å—specifically S80, M81, F84, Y93, S94, L253, W256, A257, and T261—which play a pivotal role in positioning the side chain of CHO above the heme group. (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, most residues within the 5 Å range of the pocket, including those listed above, are conserved in other bacterial P450scc enzymes, such as CYP204A5 (Fig. 5b and 5d, and Supplementary Fig. 16), suggesting that they are critical for substrate binding and maintaining catalytic conformation. To validate this, site-directed mutagenesis was performed on CYP204A5. As anticipated, most mutants exhibited significantly reduced or abolished production of PROG (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Identification of key residues for enhancing bacterial P450scc activity

With the aim of further investigating and improving the catalytic performance of bacterial P450scc enzymes, we conducted a comparative analysis of amino acid differences within the catalytic pocket across various bacterial P450scc enzymes. The analysis revealed that residues 322–325 in CYP204A5 significantly differ from the corresponding region (325Y–328S) in the less active CYP204A3 (Fig. 5b and 5d). Additionally, this motif is relatively conserved in other less active bacterial P450scc enzymes. Given the variation in enzyme activity over evolution, we speculated that these sites might be critical for higher P450scc activity.

This hypothesis was tested through the introduction of the CYP204A5 sequence (322F-323T-324M-325I) into the less active CYP204A3 background (325Y-326M-327L-328S). However, this substitution significantly reduced the catalytic activity of CYP204A3 (Fig. 5e). Further replacing the single residue of CYP204A3 and evaluating their effects on the catalytic activity revealed that only the Y325F mutation slightly enhanced catalytic activity, while other mutants significantly reduced it. Additionally, combinatorial two- and three-site swaps generally resulted in lower catalytic activity, except for the Y325F-L327M-S328I mutant, which retained activity comparable to the wild type (Fig. 5e). These results demonstrate that these regions are pivotal, and subtle changes significantly affect catalytic activity.

To further enhance the catalytic efficiency of CYP204A5, we implemented comprehensive site-saturation mutagenesis (SSM) targeting 22 residues located within the 5 Å substrate-binding pocket: S77, M78, F81, Y90, S91, S177, M180, L250, W253, A254, E257, T258, V320, A321, F322, T323, M324, I325, R326, A429, G430 and T431. A total of 418 single-site variants were generated and screened for their side-chain cleavage activity. Eight mutants (S91M, S91I, T323V, T323L, T323C, T323I, M324L, and M324I) exhibited significantly enhanced catalytic activity, producing PROG at levels approximately 3.5 to 6.5-fold higher than the wild type (Fig. 5f). These beneficial mutations were primarily located at three sites: S91, T323, and M324. Interestingly, T323 and M324 are part of the identified motif, reinforcing their crucial role in catalytic performance. However, combinatorial double mutants did not further enhance catalytic activity (Fig. 5f), suggesting that the identified single-site mutations already optimize the local structural environment for enhanced activity.

For the purpose of elucidating the molecular basis underlying the enhanced catalytic activity, we performed MD simulations on three representative mutants: CYP204A5-S91M, CYP204A5-T323L, and CYP204A5-M324I. For the S91M mutant, MD simulations indicated that the bulkier side chain introduced steric hindrance, which restricted the bending of the CHO-side chain (Fig. 6a). This restriction kept the C20 and C22 positions closer to Cpd I (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 18), thereby promoting more efficient catalytic conversion. Molecular dynamics trajectories indicated that, relative to the wild type, the T323L and M324I mutations also resulted in the C20 and C22 atoms of CHO adopting a closer proximity to the iron-oxo ligand of Cpd I (Fig. 6c–f; Supplementary Fig. 18). This altered positioning may contribute to more efficient hydroxylation at C20 and C22, suggesting a plausible mechanistic basis for the observed changes in catalytic activity. Structural analysis further showed that the T323L and M324I mutations introduced branched aliphatic side chains, enhancing hydrophobic interactions with the CHO. These interactions stabilized the substrate in a catalytically favorable conformation, thereby increasing overall activity.

d1: the distance of Fe-O and C20; d2: the distance of Fe-O and C22. a A representative snapshot of CYP204A5-S91M with substrate CHO. b Statistics of the distance d1 and d2 for CYP204A5 and CYP204A5-S91M. c A representative snapshot of CYP204A5- T323L with substrate CHO. d Comparative statistics of distances d1 and d2 for CYP204A5 and CYP204A5-T323L. e A representative snapshot of CYP204A5-M324I with substrate CHO. f Comparative statistics of the distance d1 and d2 for CYP204A5 and CYP204A5-M324I.

In contrast to the wild-type enzyme, where all monohydroxylated intermediates (20S-HCO and 22R-HCO) and the dihydroxylated intermediate (20R, 22R-DHCO) were detected, the mutant strains exhibited significant conversion of hydroxylated intermediates (Supplementary Fig. 19), consistent with the improved catalytic efficiency observed for CHO cleavage. MD simulations of the S91M and T323I mutants revealed that the monohydroxylated substrates 20S-HCO and 22R-HCO remained in closer proximity to Cpd I throughout the simulation compared to the wild type (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21). This finding is consistent with the observed enhancement in enzymatic activity. This suggests that the primary effect of the mutation on activity is related to altering the distance between the side chain and Cpd I. Based on the MD simulations and mutagenesis results described above, we speculate that the relatively lower activity of CYP204 enzymes towards cholesterol and phytosterols, compared to cholestenone, may be attributed to hydrogen-bonding interactions influenced by the C3-hydroxyl group, as well as steric effects caused by differences in their side chains. These factors likely hinder the optimal positioning of C20 and C22 near the Cpd I for efficient catalysis. Overall, these findings demonstrate that modifying steric hindrance and enhancing hydrophobic interactions in the catalytic pocket of bacterial P450scc enzymes effectively improves side-chain cleavage activity. This structure-guided engineering approach offers a promising strategy for optimizing bacterial P450scc enzymes for biocatalytic applications.

Discussion

Microbial steroid degradation is ecologically, medically, and industrially significant, as steroids, including sterols and hormones, are abundant in nature and serve as microbial growth substrates, yet their persistence poses endocrine-disrupting risks17,18. Bacteria typically mineralize steroids through multi-enzyme pathways for side-chain cleavage4. Here, we identify and characterize bacterial P450scc enzymes from steroid-degrading microorganisms, demonstrating their ability to perform efficient single-enzyme-catalyzed side-chain cleavage, revealing an alternative bacterial steroid side-chain degradation strategy. Evolutionary genome mining and biochemical studies reveal these enzymes across diverse bacterial species, suggesting their potential role in environmental sterol metabolism. These findings highlight the promise for further functional studies and exploration of their distribution in other environments, such as human microbiomes. In addition, while phylogeny-based mining provides an effective approach for identifying candidate steroid-related P450 enzymes, its utility in predicting position-specific hydroxylation patterns remains limited due to the complex structure-function relationships inherent to these enzymes. Future investigations that incorporate sequence-substrate correlations and detailed structural analyses of conserved substrate-binding regions should enable P450s with target regio- and stereoselectivity to be identified more precisely.

Bacterial steroid biotransformation serves as a source of biocatalysts for steroid drug synthesis in the pharmaceutical industry4. The P450-catalyzed cholesterol side-chain cleavage reaction offers a direct and efficient pathway for steroidal drug synthesis. However, the practical application of mammalian P450scc has been hindered by challenges in heterologous expression, membrane-associated complexity, and limited mutability due to high sequence conservation22,24,26. The identification and characterization of previously uncharacterized bacterial P450scc enzymes in this study providing a compelling alternative for biocatalysis. With their robust catalytic activity, excellent solubility, and remarkable engineering plasticity, these enzymes are highly suitable for industrial applications. The successful engineering of CYP204A5 underscores the biotechnological potential of bacterial P450scc enzymes. Through rational mutagenesis of hotspot residues (e.g., T323 and M324), we increased catalytic efficiency by 3.5- to 6.5-fold, a rare accomplishment with mammalian P450scc. Notably, mutations introducing hydrophobic interactions near the steroid nucleus subtly repositioned the substrate toward the heme center, illustrating how precise steric modulation can optimize catalytic geometry. Coupled with their inherent solubility, these insights position bacterial P450scc enzymes as superior platforms for developing next-generation biocatalysts, paving the way for sustainable steroid drug production.

Our study uncovers a mechanistic divergence between bacterial and mammalian P450scc systems. While mammalian CYP11A1 strictly follows a sequential C22 to C20 hydroxylation through rigid substrate repositioning9, bacterial P450scc employs a dynamic C-H activation mechanism that facilitates simultaneous C20 and C22 hydroxylation. Structural and molecular dynamics analyses attribute this functional flexibility to an expanded substrate cavity in bacterial enzymes, enabling diverse sterol conformations—a feature notably absent in their mammalian counterparts. This evolutionary divergence demonstrates how bacterial P450scc has optimized catalytic efficiency through structural versatility rather than constrained substrate positioning.

Overall, we have identified bacterial P450scc enzymes in steroid-degrading microorganisms that exhibit a distinct C–H activation mechanism facilitated by an enlarged substrate binding pocket. This flexible catalytic approach differs fundamentally from the stepwise hydroxylation process observed in mammalian P450scc systems. Structural insights guided rational engineering, achieving a 6.5-fold enhancement in cholestenone-to-progesterone conversion, establishing these enzymes as efficient biocatalysts. Phylogenetic and biochemical analyses revealed their widespread distribution across diverse bacteria, suggesting a role in environmental sterol metabolism. This discovery unveils a distinct bacterial steroid-side chain degradation pathway, diverging from traditional multi-enzyme systems. With their catalytic efficiency, substrate versatility, and biotechnological potential, these enzymes bridge fundamental research and industrial applications, offering a sustainable platform for steroid synthesis and environmental biotechnology.

Methods

Methods for mining bacterial P450s for steroid modification

The selection of 265 microorganisms for this investigation was systematically conducted based on comprehensive literature reviews documenting steroid-degrading microorganisms18. Their genomic sequences were retrieved from the NCBI RefSeq database38. A robust local genomic database comprising 265 microorganisms was constructed utilizing BioEdit2 software39. To identify cytochrome P450 sequences, we conducted a BLAST search against the established local database, employing a known bacterial P450 sequence (NCBI accession number: WP_003898577.1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis EAS054) as the reference30. This analysis yielded 1000 candidate sequences, which were subsequently subjected to multiple sequence alignment using MUSCLE with default parameters. For phylogenetic reconstruction, the identified P450 protein sequences were analyzed alongside known CYP51 sequences through the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method implemented in MEGA 1140. The resulting phylogenetic relationships were visualized and annotated using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) platform41, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 4.

Molecular cloning and mutagenesis

The molecular cloning was performed using E. coli DH5α cells according to standard protocols. The genes encoding P450s (CYP51-A1~A8, CYP204A3-A6, CYP204B2, CYP204C1, CYP204D1, CYP204E1 and CYP204F1) in the study were synthesized and cloned into the pET28a (+) vector with a N-terminal His6-tag by ATANTARES (Suzhou, China) (Supplementary Data 2). Mutational gene construction was achieved by site-directed mutagenesis via rolling circle amplification. Primer synthesis and DNA sequencing were performed at Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. All the primers used in this study are all listed in Supplementary Data 5. Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Protein expression and purification

For the expression of P450s and their mutants, the plasmid carrying the gene encoding P450 was transferred into E. coli BL21 (DE3), the resulting strains were grown overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm, which were used as seed cultures to inoculate LB medium at a 1:100 ratio. Cells were grown at 37 °C until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.8 −1.0 and then induced by the addition of isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (0.1 mM), δ-amino-levulinic acid (0.4 mM), and ferrous sulfate (0.2 mM). The induced cultures were further incubated at 18 °C for 20 h with shaking at 200 rpm. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in Buffer A (25 mM Hepes, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, pH 7.5, the pH can be adjusted according to the characteristics of different proteins). The cells were broken by ultra-sonication, and the insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation at 13,500 x g for 1 h at 4 °C. The protein supernatant was then incubated with 1 mL Ni-NTA sepharose for 1.5 hours with slow, constant rotation at 4 °C. Subsequently the protein resin mixtures were loaded into a gravity flow column, and proteins were eluted with increasing concentrations of imidazole (25 mM, 50 mM, 100 mM, 300 mM) in Buffer A. Purified proteins were collected according to SDS-PAGE and then loaded into PD-10 desalting columns to desalt using Buffer B (50 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, pH 7.5, the pH can be adjusted according to the characteristics of different proteins). The final purified proteins were concentrated by centrifugation using an Amicon Ultra-4(GE Healthcare) and stored at −80 °C for later use.

The expression and purification of redox partner SpFdx/SpFdR, SeFdx1499/ SeFdR0978, and glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) were conducted as described above, except that only IPTG was added when OD600 reached 0.8 −1.0.

Biochemical assay

The enzymatic reactions were performed in a 100 μL reaction mixture containing 50 mM TES buffer (N-(Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl)−2-aminoethanesulfonic acid sodium salt, pH 7.5), 10 µM P450scc, 40 µM Fdx, 10 µM FdR, 500 µM substrate, and an NADPH regeneration system comprised of 10 mM glucose, 1 mM GDH, and 1 mM NADPH. Reactions with boiled enzymes were performed as controls. Then all reactions were incubated at 18 °C for 12 h and subsequently quenched with the addition of equal methanol (100 μL). Protein was removed by centrifugation at 13,500 x g for 10 min, the 5 μL supernatants were subjected to UPLC (LC-30A, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) or UPLC-MS (LCMS-2020, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) system using a Shimadzu Shim-pack GIST C18 column (2 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) at a flow rate of 0.2 mL∙min–1 using a mobile phase of (A) H2O containing 0.1% fomic acid and (B) CH3CN. The elution procedure was a 25 min gradient program as follows: t = 0 min, 30% B; t = 8 min, 100% B; t = 20 min, 100% B; t = 21 min, 30% B; t = 25 min, 30% B.

Mass spectrometer parameters were as follows: positive/negative ionization, SIM event time 0.3 s, Detector voltage 1.5 kV, Interface voltage –4.5 kV, DL voltage 0 V, Interface temperature 350 °C, DL temperature 250 °C, Nebulizing gas flow 1.5 L/min, Heat unit temperature 200 °C, Drying gas flow rate 15 L/min, Ionization mode DUIS (ESI and APCI). The m/z range was 100–850.

Protein structure prediction and molecular docking

The predicted structure of CYP204 enzymes was constructed using AlphaFold342, the CYP204A3 protein sequence (UniProt Accession ID: A0A258V3A8) was submitted to the AlphaFold Server on July 27, 2024 (https://alphafoldserver.com/). The top-ranked model was used for comparison with the experimentally determined crystal structure. The pLDDT scores were color-coded and overlaid from two viewing angles, and the predicted aligned error (PAE) plot was also generated and included, which are provided in Supplementary Fig. 10. The CYP204A5 (NCBI Accession ID: WP_058802412.1) protein sequence was submitted to the AlphaFold Server on January 8, 2025 (https://alphafoldserver.com/). The top-ranked model was used for molecular docking. The visualizations of pLDDT scores and the PAE plot were provided in Supplementary Fig. 15.

Molecular docking studies were conducted using the SwissDock web-based platform43. The center position and dimensions of the box have been adjusted to position it correctly above the P450 heme. All other settings use default values. The selected orientations did not always correspond to the lowest-energy states, as we focused on poses with the steroid side chains positioned close to the ferric heme center. The parameters and details are listed in the Supplementary Table 7, and Protein-Ligand docking structures generated in this study are presented in Supplementary Data 6.

MD Simulations

The optimal binding pose of the substrate in the P450 active site was selected from molecular docking results. The Compound I (Cpd I) fragment, consisting of the heme cofactor (Fe–protoporphyrin IX) with the oxo radical and its proximal cysteine ligand, together with the substrate, was subjected to geometry optimization using Gaussian 1644 at the B3LYP functional level with the LANL2DZ pseudopotential basis set for FE and 6-31 G(d) basis set for C, H, O, N and S atoms. To account for solvent effects, the IEFPCM implicit solvation model was applied throughout the optimization45,46. The spin multiplicity was set to 4, in agreement with previously published studies47. The optimized wavefunction files were processed with Multiwfn48 to derive RESP charges. Bonded and non-bonded parameters for Cpd I and the substrate were generated using Sobtop49 based on the RESP charges.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using GROMACS 2022.450. The AMBER14SB force field51 was used for the protein, GAFF52 for the substrate, and TIP3P53 for water molecules. Four sodium ions were added to neutralize the total charge of the system. The protein complex was solvated in a rectangular box, with periodic boundary conditions applied in all directions. The system setup, including simulation box dimensions, total number of atoms, number of water molecules, and salt concentration, was presented in Supplementary Data 7. The force field parameters contain atom types, charges, and Lennard-Jones parameters (σ, ε) of CpdI and substrate are provided in Supplementary Data 8.

The optimized wavefunction files were processed with Multiwfn48 to derive RESP charges. Specifically, a two-step charge fitting is performed. In the first stage, a weak hyperbolic restraint (a = 0.0005) is imposed on the atomic charges to allow the greatest degree of freedom for the charges on polar atoms to fit the ESP. In the second stage, a restraint coefficient of a = 0.0010 was applied. Based on the first-step results, the fitting is restricted to the charges of sp3 hybridized carbons, methylene carbons (excluding the terminal capping groups), and their attached hydrogen atoms, while enforcing charge equivalency for chemically equivalent hydrogens. The detailed input and output files for the RESP fitting procedure are provided in a figshare repository (see Data Availability).

Protonation states of titratable residues were assigned at pH 7.4 using the default settings of pdb2gmx. Energy minimization was carried out in two steps: 10,000 steps of steepest descent followed by 5,000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization. The minimized structure was equilibrated with 500 ps of NVT and 500 ps of NPT simulations, during which positional restraints were applied. Three independent production MD runs were performed for 100 ns each with a 2 fs integration step. The temperature was maintained at 291.15 K using the V-rescale54 thermostat, and the pressure at 1 bar using the Parrinello–Rahman55 barostat. Long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the particle mesh Ewald (PME)56 method, with a real-space cutoff of 1.2 nm. The van der Waals (vdW) cutoff was also set to 1.2 nm. Hydrogen bonds were constrained with the LINCS algorithm. The input files for energy minimization and equilibration and the files for production runs are provided in provided in a figshare repository (see Data Availability).

Crystallization of protein and compound

CYP204A3 crystals were grown at 20 °C using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method, and crystals of the compounds were produced at 4 °C using the slow volatilization method (details in Supplementary Methods).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The structure of substrate-free CYP204A3 has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under ID numbers, 9WAT57. The structure of mammalian CYP11A1-cholesterol complex is available in Pthe DB database 3N9Y. The crystallographic data for 22S-HCO, 20S-HC, and 22R-HC have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center with deposition numbers CCDC 2414994 (22S-HCO), CCDC 2415099 (20S-HC), and CCDC 2414991 (22R-HC)58, these data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures. All data associated with the MD simulations have been deposited in figshare under the following URLS: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30657758. The other characterization data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information or Source Data file. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kolatorova, L., Vitku, J., Suchopar, J., Hill, M. & Parizek, A. Progesterone: a steroid with wide range of effects in physiology as well as human medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 7989–8024 (2022).

Nagy, B. et al. Key to life: Physiological role and clinical implications of progesterone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11039–11053 (2021).

Lin, Y. C., Cheung, G. & Espinoza, N. Papadopoulos, function, regulation, and pharmacological effects of pregnenolone in the central nervous system. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 22, 100310–100317 (2022).

Peng, H. et al. A dual role reductase from phytosterols catabolism enables the efficient production of valuable steroid precursors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 60, 5414–5420 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Bacterial cytochrome P450-catalyzed regio- and stereoselective steroid hydroxylation enabled by directed evolution and rational design. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 7, 2–19 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. A designed chemoenzymatic route for efficient synthesis of 6-dehydronandrolone acetate: A key precursor in the synthesis of C7-functionalized steroidal drugs. ACS Catal. 13, 13111–13116 (2023).

Mast, N. et al. Structural basis for three-step sequential catalysis by the cholesterol side chain cleavage enzyme CYP11A1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 5607–5613 (2011).

Simpson, E. & Boyd, G. The cholesterol side-chain cleavage system of bovine adrenal cortex. Eur. J. Biochem. 2, 275–285 (1967).

Strushkevich, N. et al. Structural basis for pregnenolone biosynthesis by the mitochondrial monooxygenase system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 10139–10143 (2011).

Davydov, R., Gilep, A. A., Strushkevich, N. V., Usanov, S. A. & Hoffman, B. M. Compound I is the reactive intermediate in the first monooxygenation step during conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone by cytochrome P450scc: EPR/ENDOR/cryoreduction/annealing studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17149–17156 (2012).

Su, H., Wang, B. & Shaik, S. Quantum-mechanical/molecular-mechanical studies of CYP11A1-catalyzed biosynthesis of pregnenolone from cholesterol reveal a C–C bond cleavage reaction that occurs by a compound I-mediated electron transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 20079–20088 (2019).

Yoshimoto, F. K., Jung, I.-J., Goyal, S., Gonzalez, E. & Guengerich, F. P. Isotope-labeling studies support the electrophilic compound I iron active species, FeO3+, for the carbon–carbon bond cleavage reaction of the cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme, cytochrome P450 11A1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12124–12141 (2016).

Samuels, L., Helmreich, M., Lasater, M. & Reich, H. An enzyme in endocrine tissues which oxidizes Δ5-3 hydroxy steroids to α, β unsaturated ketones. Science 113, 490–491 (1951).

Carroll, E., Ravi Gopal, B., Raghavan, I., Mukherjee, M. & Wang, Z. Q. A cytochrome P450 CYP87A4 imparts sterol side-chain cleavage in digoxin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–11 (2023).

Kunert, M. et al. Promiscuous CYP87A enzyme activity initiates cardenolide biosynthesis in plants. Nat. Plants 9, 1607–1617 (2023).

Li, R. et al. Elucidation of the plant progesterone biosynthetic pathway and its application in a yeast cell factory. Metab. Eng. 90, 197–208 (2025).

Chiang, Y.-R., Wei, S. T.-S., Wang, P.-H., Wu, P.-H. & Yu, C.-P. Microbial degradation of steroid sex hormones: implications for environmental and ecological studies. Microb. Biotechnol. 13, 926–949 (2020).

Bergstrand, L. H., Cardenas, E., Holert, J., Van Hamme, J. D. & Mohn, W. W. Delineation of steroid-degrading microorganisms through comparative genomic analysis. mBio 7, 1–13 (2016).

Van der Geize, R. et al. A gene cluster encoding cholesterol catabolism in a soil actinomycete provides insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104, 1947–1952 (2007).

Marker, R. E., Tsukamoto, T., Turner, D. & Sterols, C. Diosgenin1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 62, 2525–2532 (1940).

Herráiz, I. “Chemical pathways of corticosteroids, industrial synthesis from sapogenins” in Microbial steroids. Methods in molecular biology, J.-L. Barredo, I. Herráiz, Eds. (Humana Press, New York, NY), vol. 1645, 15–27 (2017).

Duport, C., Spagnoli, R., Degryse, E. & Pompon, D. Self-sufficient biosynthesis of pregnenolone and progesterone in engineered yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 186–189 (1998).

Efimova, V., Isaeva, L., Rubtsov, M. & Novikova, L. Analysis of in vivo activity of the bovine cholesterol hydroxylase/lyase system proteins expressed in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biotechnol. 61, 261–273 (2019).

Makeeva, D. S., Dovbnya, D. V., Donova, M. V. & Novikova, L. A. Functional reconstruction of bovine P450scc steroidogenic system in Escherichia coli. Am. J. Mol. Biol. 3, 173–182 (2013).

Shashkova, T. V., Luzikov, V. N. & Novikova, L. A. Coexpression of all constituents of the cholesterol hydroxylase/lyase system in Escherichia coli cells. Biochemistry 71, 810–814 (2006).

Zhang, R. et al. Pregnenolone overproduction in Yarrowia lipolytica by integrative components pairing of the cytochrome P450scc system. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 2666–2678 (2019).

Liu, R. et al. Comparative biochemical characterization of mammalian-derived CYP11A1s with cholesterol side-chain cleavage activities. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 229, 1–11 (2023).

Szaleniec, M., Wojtkiewicz, A. M., Bernhardt, R., Borowski, T. & Donova, M. Bacterial steroid hydroxylases: enzyme classes, their functions and comparison of their catalytic mechanisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 8153–8171 (2018).

Song, F. et al. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of C14-functionalized steroids. Nat. Synth. 2, 729–739 (2023).

Bellamine, A., Mangla, A. T., Nes, W. D. & Waterman, M. R. Characterization and catalytic properties of the sterol 14α-demethylase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96, 8937–8942 (1999).

Tian, W. et al. Efficient biosynthesis of heterodimeric C3-aryl pyrroloindoline alkaloids. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–9 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. In vitro reconstitution of the cyclosporine specific P450 hydroxylases using heterologous redox partner proteins. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 44, 161–166 (2017).

Nelson, D. R. “Cytochrome p450 nomenclature, 2004” in Cytochrome p450 protocols. Methods in molecular biology, I. R. Phillips, E. A. Shephard, Eds. (Humana Press, Totowa, NJ), vol. 320, 1-10 (2006).

Nelson, D. R. The cytochrome P450 homepage. Hum. Genomics 4, 1–7 (2009).

Poulos, T. L., Finzel, B. C., Gunsalus, I. C., Wagner, G. C. & Kraut, J. The 2.6-Å crystal structure of pseudomonas putida cytochrome P−450. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 16122–16130 (1985).

Sun, C. et al. Molecular basis of regio-and stereo-specificity in biosynthesis of bacterial heterodimeric diketopiperazines. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–10 (2020).

Wei, G. et al. A nucleobase-driven P450 peroxidase system enables regio-and stereo-specific formation of C─ C and C─ N bonds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 121, 1–9 (2024).

Tatusova, T. et al. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6614–6624 (2016).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/nt. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 (1999).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W78–W82 (2024).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Grosdidier, A., Zoete, V. & Michielin, O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W270–W277 (2011).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01 Inc., Wallingford, CT. (2016).

Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B. & Cammi, R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 105, 2999–3094 (2005).

Miertuš, S., Scrocco, E. & Tomasi, J. Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilizaion of AB initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. Chem. Phys. 55, 117–129 (1981).

Shahrokh, K., Orendt, A., Yost, G. S. & Cheatham III, T. E. Quantum mechanically derived AMBER-compatible heme parameters for various states of the cytochrome P450 catalytic cycle. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 119–133 (2012).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Lu, T. Sobtop, Version 1.0, http://sobereva.com/soft/Sobtop.

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1, 19–25 (2015).

Maier, J. A. et al. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3696–3713 (2015).

Wang, J., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 (2004).

Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 1–8 (2007).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981).

Essmann, U. et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 (1995).

Zhang, Z. Y. et al. The crystal structure data of CYP204A3. RSCB Protein Data Bank, https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb9wat/pdb (2025).

Tian, W. et al. The crystallographic data for 22S-HCO, 20S-HC and 22R-HC. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center. https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Shengying Li (Shandong University) for the kind gift of the plasmid containing DNA encoding the mature form of redox partners SeFdx1499 and SeFdR0978. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22407088 to W.T., 32425033 to X.Q., 22307076 to G.W., 32301216 to M.Z. and 32100036 to H.P.), the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project, the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (23ZR1432800 to X.Q.), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M742272 to W.T., GZB20230413 to W.T. and 2025T180976 to W.T.), Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Talent and Platform Program (202505AF350066 to X.Q.) and the Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (22XD1421300 to X.Q.). We also thank the staff of beamlines BL18U1 and BL19U1 of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) for access and help with the X-ray data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Q., Z.Z., W.T., and G.W. designed research; W.T., G.W., B.D., and H.L. performed research; B.D. and Z.Z. solved the crystal structures; W.T., G.W., B.D., H.P., M.Z., Z.L., Z.D., and X.Q. analyzed data; W.T., G.W., and X.Q. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alec Follmer and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, W., Wei, G., Duan, B. et al. Unveiling cytochrome P450 enzymes that catalyze steroid side-chain cleavage in bacteria. Nat Commun 17, 581 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67278-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67278-3