Abstract

Quantum Monte Carlo is one of the most promising approaches for dealing with large-scale quantum many-body systems. It has played an extremely important role in understanding strongly correlated physics. However, two fundamental problems, namely the sign problem and general measurement issues, have seriously hampered its scope of application. We propose a universal scheme to tackle the problems of general measurement. The target observables are expressed as the ratio of two types of partition functions \(\langle O\rangle=\overline{Z}/Z\), where \(\overline{Z}=tr({Oe}^{-\beta H})\) and \(Z=tr({e}^{-\beta H})\). These two partition functions can be estimated separately within the reweight-annealing frame, and then be connected by an easily solvable reference point. We have successfully applied this scheme to XXZ model and transverse field Ising model, from 1D to 2D systems, from two-body to multi-body correlations and even non-local disorder operators, and from equal-time to imaginary-time correlations. The reweighting path is not limited to physical parameters, but also works for space and time. Essentially, this scheme solves the long-standing problem of calculating the overlap between different distribution functions in mathematical statistics, which can be widely used in statistical problems, such as quantum many-body computation, big data and machine learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) is a highly promising numerical method without approximations for large-scale or high-dimensional quantum many-body systems, capable of simulating complex systems with an exponential degree of freedom while maintaining polynomial computation complexity1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Despite the maturity of QMC techniques after decades of development15,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, there remain two essential challenges that greatly limit the application of QMC. The first is the notorious sign problem34,35,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58, and the second is the issue of general (off-diagonal) measurements7,10,16,30,59.

In this work, we will focus on the enduring challenge of measuring general (off-diagonal) observables. The target is how to extract as more as information from the QMC samplings. Unlike other numerical methods, QMC cannot directly obtain the wave-function of ground state. Typically, the evaluation of a physical quantity 〈O〉 in QMC is derived as follows: \(\langle O\rangle=tr({Oe}^{-\beta H})/Z\), where \(Z=tr({e}^{-\beta H})\) is the partition function (PF), β is the inverse temperature and H is the Hamiltonian. For simplicity, we define \(\overline{Z}=tr({Oe}^{-\beta H})\), hence \(\langle O\rangle=\overline{Z}/Z\).

In a standard QMC framework, the partition function Z can be generally decomposed into the sum of all the weights, i.e. Z = ∑iWi. If the operator O can be treated as a number Oi under the configuration of Wi, which corresponds to a diagonal measurement, the physical quantity can be readily estimated in the form

In this way, the value Oi can be directly obtained when we sample the configurations Wi of the PF, making diagonal measurements straightforward in the QMC framework. In the case of diagonal measurement, it is clear that two PFs, \(\overline{Z}={\sum }_{i}{O}_{i}{W}_{i}\) and Z = ∑iWi, share the same set of configurations {Wi}, but differ in their associated values, with Oi for \(\overline{Z}\) and 1 for Z. Consequently, sampling the configurations {Wi} is sufficient to capture the expectation value \(\langle O\rangle=\overline{Z}/Z\).

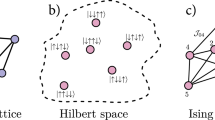

However, the situation would deteriorate significantly during off-diagonal measurements. Off-diagonal operators typically alter the existing configurations {Wi} of Z = ∑iWi, resulting in new configurations \(\{{W}_{i}^{{\prime} }\}\) for \(\overline{Z}={\sum }_{i}{W}_{i}^{{\prime} }\) that are entirely distinct from the original set {Wi}. This implies that we are unable to obtain samples \(\{{W}_{i}^{{\prime} }\}\) within the framework of conventional QMC methods, which are designed to sample from {Wi}. As shown in Fig. 1(a), two PFs no longer share the same configurations, making it impossible to simulate their ratio directly as in the diagonal case. Furthermore, it is usually impossible to design updates between {Wi} and \(\{{W}_{i}^{{\prime} }\}\) in QMC algorithms (If you can realize the updates between {Wi} and \(\{{W}_{i}^{{\prime} }\}\), the ratio \(\overline{Z}/Z\) then can be obtained, such as the QMC algorithm for entanglement entropy60). This represents the fundamental challenge in the off-diagonal measurements.

Direct evaluation of the ratio \(\overline{Z}({J}_{0})/Z({J}_{0})\) is generally infeasible, since the corresponding weight distributions at J0 exhibit a lack of overlap, as sketched in (a). Instead, two independent reweight-annealing (RA) processes are performed: the red path corresponds to \(\overline{Z}(J)/\overline{Z}({J}_{0})\), and the blue path corresponds to Z(J)/Z(J0), as indicated by the colored RA process labels. Along each path, the system is gradually evolved in the annealing direction through small parameter shifts \({J}^{{\prime} }=J+\delta J\), ensuring sufficient overlap between adjacent distributions, as illustrated in (b) and (c). Once the annealing paths reach an easily solvable reference point, the target ratio \(\overline{Z}({J}_{0})/Z({J}_{0})\) can be reconstructed.

In some special cases, certain off-diagonal observables can be extracted in ingenious ways. For instance, determinant QMC (DQMC) can efficiently calculate two-body Green’s functions, where higher-order correlators can be derived using Wick’s theorem11,31,35,61. This works particularly well in fermionic systems, where off-diagonal Green’s functions such as \(\langle {c}_{i}{c}_{j}^{\dagger }\rangle\) are naturally embedded in the sampling weight. We now fix the measurement problem in other Monte Carlo methods, such as diagrammatic QMC62,63,64, world-line QMC and stochastic series expansion (SSE) formulations, in which off-diagonal measurements pose a much more severe challenge. Despite numerous efforts in the past, two-body Green’s functions can be obtained only in certain cases within the framework of worm-like QMC9,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73. The reason is that the configurations in the worm-like update process can be treated as samplings of the two-point Green’s function. However, multi-body Green’s functions remain challenging to be extracted even with this specialized approach and the worm-like algorithm only works in several models. In addition, if the off-diagonal operator to be measured is a part of the Hamiltonian, it can be estimated through the sampling process74. As an instance, 〈Sx〉 can be measured in a transverse field Ising model (TFIM)75,76. Another example is that, in the stochastic series expansion (SSE) method, the energy value can be calculated directly by counting the number of operators in the space-time configurations2,7,30. Although the importance of off-diagonal observables in quantum systems, there is currently no general method for measuring arbitrary operators in QMC, even though a lot of effort has been devoted to it over the past decades.

Recently, a newly proposed method – reweight-annealing (RA)77 has been successfully applied to determine the ratio of two same-type PFs at different parameters. In the reweight-annealing method, as shown in Fig. 1(b) and (c), the PF at the parameter \({J}^{{\prime} }\) can be estimated using the value of PF at another parameter J by resetting the weights.

This equation states that the ratio \(Z({J}^{{\prime} })/Z(J)\) is obtained by averaging \(W({J}^{{\prime} })/W(J)\) over configurations sampled from the ensemble at J (i.e.〈⋅〉J). However, this equation works well only when the distributions \(Z({J}^{{\prime} })\) and Z(J) are adjacent. In this context, the importance sampling can be maintained78. Therefore, if the target parameters J and \({J}^{{\prime} }\) are far away from each other, a series of intermediate parameters {Ji} need to be inserted to split the reweighting process by gradually moving from J to \({J}^{{\prime} }\). This can be expressed as \(Z({J}^{{\prime} })/Z(J)=Z({J}^{{\prime} })/Z({J}_{1})\times Z({J}_{1})/Z({J}_{2})\times \ldots Z({J}_{i})/Z({J}_{i+1})\ldots \times Z({J}_{n})/Z(J)\). Since the entire process involves annealing from one parameter to another with iterative reweighting, it is dubbed as “reweight-annealing"77. The similar spirit of reweighting also has been developed in the high-energy physics and other fields79,80,81,82,83,84. Once a reference point Z(J) is known, \(Z({J}^{{\prime} })\) can be calculated through the ratio. It has been proved that the computation complexity of the RA method is polynomial if the ratio of two closest Z(J) and \(Z({J}^{{\prime} })\) is fixed in the division strategies77. More specifically, in the QMC simulation, maintaining the ratio of two closest partition functions \(Z({J}^{{\prime} })/Z(J)\) with \({\mathcal{O}}(1)\) range (i.e. 0.1 ~ 10) is essential–not only to preserve the polynomial computation complexity under importance sampling77, but also to ensure that system error remains controllable (system error analysis can be found in Supplementary Note 7). In addition, the number of slices should be increased near the phase transition to maintain the ratio with \({\mathcal{O}}(1)\) range, since the distribution of the partition function changes more rapidly in this regime. Motivated by the reweighting scheme, we propose a novel scheme termed “bipartite reweight-annealing (BRA)" method to address the challenges of general measurements in QMC simulations. We will present several examples to demonstrate its feasibility and versatility.

Results

Bipartite reweight-annealing framework

In fact, we realize that the reweighting scheme is not only limited to the standard PF Z(J) but can be applied to any distribution that varies with the related parameters. In practice, an off-diagonal observable can be treated as the ratio of two types of PFs \(\langle O\rangle=\overline{Z}/Z\), where \(\overline{Z}=tr({Oe}^{-\beta H})\). This insight inspires us to reweight different kinds of PFs (the numerator \(\overline{Z}(J)\) and denominator Z(J)) respectively, as Fig. 1(b) and (c) show. The key idea is that we firstly calculate the ratios \(\overline{Z}({J}^{{\prime} })/\overline{Z}(J)\) and \(Z({J}^{{\prime} })/Z(J)\), and if we have a reference point \(\overline{Z}(J)/Z(J)\) which is easily solvable (as displayed in Fig. 1), then the target measurement \(\langle O({J}^{{\prime} })\rangle\) can be estimated in this approach:

where \(\overline{Z}(J)/Z(J)\) is the known reference point, \(\overline{Z}({J}^{{\prime} })/\overline{Z}(J)\) and \(Z(J)/Z({J}^{{\prime} })\) can be calculated by reweighting. Likewise, maintaining the ratio within an \({\mathcal{O}}(1)\) range is imperative (detail can be found in Supplementary Note 7).

This BRA scheme avoids the intractable problem of calculating the ratio between two entirely different PFs (Fig. 1(a)) by translating it into a solvable framework. It is highly general and can be applied to almost all physical quantities. In the following sections, we will employ this scheme to demonstrate several off-diagonal measurements that previously were rather difficult, even impossible to be calculated in QMC. Moreover, scanning the observables along the path of physical parameter to trace the phase diagram becomes natural and efficient in the BRA frame. Actually, we will show the annealing path is not limited to the physical parameter only, but also works for the degree of freedom in both space and time.

Equal-time off-diagonal correlations

As an example, we consider the Hamiltonian of the spin-1/2 XXZ model, which is given by:

where 〈i, j〉 denotes the nearest neighbors, Δ is the parameter that controls the anisotropy. The Hamiltonian can be simulated using the directed loop algorithm of the SSE method (detail can be found in Supplementary Note 1)9,71,85,86. In this model, two-point off-diagonal operators \(\langle {S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{j}^{x}\rangle=\langle {S}_{i}^{y}{S}_{j}^{y}\rangle=(\langle {S}_{i}^{+}{S}_{j}^{-}\rangle+\langle {S}_{i}^{-}{S}_{j}^{+}\rangle )/4\), which can be measured using worm-like sampling trick10,68,70. However, measuring a general off-diagonal correlation function is significantly more challenging.

Here, taking correlation of Sx operators as an example, we show how to measure it via varying the physical parameter Δ in our scheme,

where \(\overline{Z}(\Delta )\) represents a general partition function with extra off-diagonal operators inserted, distinguished from a normal partition function without these extra off-diagonal operators. The calculation of \(\langle {S}_{i}^{y}{S}_{j}^{y}\rangle\) is the same as \(\langle {S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{j}^{x}\rangle\) in this frame, as explained in the Supplement note 1.

Firstly, we consider an obvious reference point of this model: \({\Delta }^{{\prime} }=1\), known as the “Heisenberg point" and possessing SU(2) symmetry. This implies isotropic spin-spin correlations with \(\langle {S}_{i}^{z}{S}_{j}^{z}\rangle=\langle {S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{j}^{x}\rangle\). Moreover, since \(\langle {S}_{i}^{z}{S}_{j}^{z}\rangle\) is accessible through diagonal measurements in a standard QMC framework, the focus shifts to measuring the ratio of the partition functions. For convenience, we define that \(\overline{Z}r=\overline{Z}(\Delta )/\overline{Z}({\Delta }^{{\prime} })\) and \(Zr=Z(\Delta )/Z({\Delta }^{{\prime} })\). Then the Eq. (5) can be rewritten as

In this way, the correlation of Sx operators can be easily calculated as Fig. 2 shows (detail can be found in Supplementary Note 2).

a Ratios of two-point correlations \({C}_{ij}=\langle {S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{j}^{x}\rangle\) as a function of the Ising coupling strength Δ for L = 10 with β = 20. b Ratios of four-point correlations \({C}_{ijkl}=\langle {S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{j}^{x}{S}_{k}^{x}{S}_{l}^{x}\rangle\) in the one-dimensional chain. c Ratios of representative two-point (Cij) and four-point (Cijkl) correlations on a 4 × 2 lattice with β = 8. d Four-point correlation \({C}_{12,L/2,L/2+1}=\langle {S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{2}^{x}{S}_{L/2}^{x}{S}_{L/2+1}^{x}\rangle\) on 8 × 8 and 20 × 20 square lattices with β = 2L. a–c include comparisons with exact diagonalization (ED) results. Error bars ( ± 1σ) from SSE simulation denote the standard error of the mean obtained from the Monte Carlo bins. All calculations are performed on lattices with periodic boundary conditions (PBC).

The QMC results are also compared with the exact diagonalization (ED) in order to demonstrate the reliability of this scheme. Figure 2 shows the calculation results from ED and BRA. The subfigures (a) and (b) exhibit two-point correlations and four-point correlations, represented by \({C}_{2}(r)=\langle {S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{i+r}^{x}\rangle\) and \({C}_{4}=\langle {S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{j}^{x}{S}_{k}^{x}{S}_{l}^{x}\rangle\) in an XXZ chain with L = 10 and β = 20. Similar simulation results of 2D lattice with Lx = 4, Ly = 2, β = 8 are shown in the subfigure (c). The black line represents the ED results which match well with the QMC data. We have plotted only a few points on the graph for clarity, while the actual simulation data points of BRA are densely distributed.

One may feel that the SU(2) symmetry at \({\Delta }^{{\prime} }=1\) is a strict condition which is not general for an arbitrary model. Actually, it is convenient to introduce an auxiliary Hamiltonian H0 with friendly symmetry or easily solvable property. As what quantum annealing does87,88,89, we can set the BRA path as tH + (1 − t)H0 and anneal from t = 0 to t = 1. This approach allows us to obtain the observable of the target Hamiltonian H.

System size and distance growth by annealing

Another choice for the reference point is to measure the observable through the ED method in small size, then anneal the small system to large size.

In this approach, the system size L and distance r between \({S}_{1}^{x}\) and \({S}_{1+r}^{x}\) can be considered as BRA parameters. For instance, we can choose the \(\langle {S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{2}^{x}\rangle\) for L0 = 4 as a reference point, and then we obtain the \(\langle {S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{2}^{x}\rangle\) for larger system L via adding the remaining sites L − L0 to the original chain, as shown in the Fig. 3(a). In this procedure, the interaction J2 is tuned to couple 4 sites with L − 4 sites. When we fix the system size and choose the \(\langle {S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{2}^{x}\rangle\) as a reference point, we can obtain the \(\langle {S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{1+r}^{x}\rangle\) (r > 1) via adding some sites to the area between \({S}_{1}^{x}\) and \({S}_{2}^{x}\) and removing some sites at the end of this chain. We need to tune the coupling J2 from 0+ to 1 and also gradually adjust the coupling J3 from 1 to 0+, in order to keeping the chain length unchanged as displayed in the Fig. 3(b). A consistent match between the QMC and ED results for off-diagonal correlations is found in Supplementary Note 5. This method certainly can be extended to the simulation of large systems. As shown in Fig. 3, we obtain the off-diagonal correlation \({C}^{xx}(r)=\langle {S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{1+r}^{x}\rangle\) using the reweighting method of changing system size (benchmark with the worm-trick method can be found in Supplementary Note 8). In Fig. 3(b), ∣Cxx(r)∣ has power-law decay, which reflects the physical feature of Luttinger liquid. As Δ decreases, the power-law parameter becomes smaller, which indicates the \({S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{j}^{x}\) correlation is enhanced and \({S}_{i}^{z}{S}_{j}^{z}\) correlation is weakened. Besides, we utilize the method of annealing Δ, which was introduced in the preceding section, with fixed large-size L = 48 to obtain the curves of ∣Cxx(r)∣ (dashed line in Fig. 3(b)), which agrees well with the results through annealing L and r.

The off-diagonal correlation measurement via lattice reweight-annealing method in the 1D XXZ model with L = 48. a The lattice diagram for annealing along the system size L. We incrementally tune the coupling J2 from 0+ to 1. b The lattice diagram for annealing along the distance r between \({S}_{1}^{x}\) and \({S}_{1+r}^{x}\). We firstly gradually adjust the coupling J2 from 0+ to 1, then we gradually tune the coupling J3 from 1 to 0+. c Two point off-diagonal correlations for system size L = 48 obtained from subplots (a) and (b) annealing method. The dashed lines represent the simulation for annealing Ising coupling Δ with fixed \({S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{1+r}^{x}\). Both the hollow symbols and the dashed line represent QMC results, displayed with error bars denoting the mean value and standard error.

Separability of measurements

The second scheme, which involves annealing from a small system to larger system, inspires us to explore the separability of the general measurement in a large system. Without loss of generality, we consider a scenario where a large system is composed of two decoupled smaller subsystems as shown in Fig. 4. This approach can be easily extended to systems with multiple parts. In the decoupled case, the density matrix of the total system is the tensor product of the two density matrices, i.e. ρ = ρA ⊗ ρB. Typically, we encounter two kinds of measured operators, OA ⊗ OB and OA + OB, they satisfy

and

where 〈…〉A∪B denotes the observable is measured in the total system A ∪ B and the coupling between A and B is zero. 〈…〉A(B) denotes the measurement in the subsystem A (B).

a When a large system is decomposed into several parts without coupling, the measured observable can also be separated into the product of independent components. b The off-diagonal correlations obtained via the annealing from two small part A and B. Here \({C}_{4}=\langle {S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{2}^{x}{S}_{L/2+1}^{x}{S}_{L/2+2}^{x}\rangle\). The \({S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{2}^{x}\) is set on the part A, and the \({S}_{L/2+1}^{x}{S}_{L/2+2}^{x}\) is set on the part B (i = L/2 + 1). The colorful dots are QMC results with standard error as error bars. And the dashed lines are the pure ED results.

Based on the above two equations, we can firstly decompose a large system into several independent parts without coupling and measure the observables of each part via ED. By taking the ED result as a reference point, we then employ QMC to reweight the coupling between each parts from zero to the target value. Consequently, the final observable in the total system can be obtained in this way.

For example, we assign \({S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{2}^{x}\) operator to subsystem A and another \({S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{i+1}^{x}\) operator to subsystem B. The expectation value \({\langle {S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{2}^{x}\rangle }_{A}\) and \({\langle {S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{i+1}^{x}\rangle }_{B}\) can be obtained via ED since the system size of A or B is small. Subsequently, we incrementally adjust the coupling JAB between A and B to obtain the correlation \(\langle {S}_{1}^{x}{S}_{2}^{x}{S}_{i}^{x}{S}_{i+1}^{x}\rangle\). As depicted in Fig. 4, we utilize the above annealing method to obtain the four-point off-diagonal correlation with different system size, and the reference points are obtained with small system size \({L}^{{\prime} }=L/2\) via ED. The QMC results are in excellent agreement with the pure ED results, which demonstrates the reliability of this method. From a technical standpoint, it is related to the annealing of L and r of the chain in the previous section, but this section more clearly demonstrates the power of this method from small to large sizes. In the next section, we will use this approach to calculate disorder operators in 2D systems.

Disorder operator in 2D TFIM

Here we investigate the off-diagonal measurement for the transverse Ising model (TFIM). The Hamiltonian is given as follows,

where σz/x is the Pauli spin-1/2 matrix and 〈i, j〉 means the nearest-neighbor coupling. h > 0 is transverse field term and J > 0 is the ferromagnetic term6. Because the TFIM only preserves Z2 symmetry, we choose the J = 0+ and h = 1 as a reference point. When J = 0, the reference point \(\langle {\sigma }_{i}^{x}{\sigma }_{j}^{x}\rangle=1\) since all the σx = 1. In the simulation, we can choose J → 0+ which makes \(\langle {\sigma }_{i}^{x}{\sigma }_{j}^{x}\rangle\) very close to 1. The BRA formula can be expressed as \(\frac{\overline{Z}(J)}{Z(J)}=\overline{Z}r/Zr\times {\langle {\sigma }_{i}^{x}{\sigma }_{j}^{x}\rangle }_{J={0}^{+}}\), where \(\overline{Z}r=\overline{Z}(J)/\overline{Z}({J}^{{\prime} }={0}^{+})\) and \(Zr=Z(J)/Z({J}^{{\prime} }={0}^{+})\). If we want to measure the many-body off-diagonal observables, we just need to change the \(\overline{Z}(J)={\langle {\sigma }_{i}^{x}{\sigma }_{j}^{x}\rangle }_{J}\) into \({\langle {\sigma }_{1}^{x}{\sigma }_{2}^{x}\ldots {\sigma }_{n}^{x}\rangle }_{J}\). For TFIM, the QMC results in small system sizes are also well consistent with the ED90,91, detail can be found in Supplementary Note 6.

We then mainly focus on the disorder operator of 2D TFIM on a square lattice. The disorder operator is a non-local operator which can reveal the high-form symmetry breaking and conformal field theory (CFT) information in quantum many-body systems92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102. For 2D TFIM, we define the disorder operator \(\langle X\rangle=\langle {\prod }_{i\in M}{\sigma }_{i}^{x}\rangle\) to detect the non-local information, where M is a R × R square area in the lattice. Its perimeter is l = 4R and it contains R2 off-diagonal operators. This disorder operator, a multi-body off-diagonal observable, was only well measured in the QMC based on σx basis in the past, which is challenging to obtain directly in the σz basis92. Although the operator σx is contained in the TFIM Hamiltonian and can be measured in the σz basis in principle27,74, it suffers from rather large fluctuations due to the requirement of a product of a series of σx in an area. It requires that the series of σx operators must appear connectedly in the time-space manifold in the σz basis, which is a low-probability event.

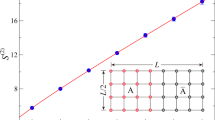

This difficulty can be overcome via BRA method. As depicted in Fig. 5, we have successfully obtained the disorder operator with different perimeters l in the paramagnetic (PM) phase and ferromagnetic (FM) phase (benchmark with the directed calculation in σx basis can be found in Supplementary Note 9). Here we set h = 1 and the critical point becomes J = 0.328573,92. For convenience, we firstly utilize the separability method in the above section to measure the disorder operator at J/h = 0.18. Taking it as a reference point, we then obtain the disorder operators for different J/h via annealing along J. In the PM phase, the disorder operator satisfies the perimeter law 〈X〉 ~ e−al, which is consistent with the CFT prediction. In the FM phase, the disorder operator satisfies the area law \(\langle X\rangle \sim {e}^{-b{l}^{2}}\), which reveals the presence of high-form symmetry92.

Imaginary-time off-diagonal correlations

Our goal becomes to extend our method to imaginary time correlation functions involving off-diagonal operators. Our discussions will concentrate on the framework of path-integral-like QMC. The first way based on the physical parameter reweighting is straightforward, which is similar to the method we have employed in the above sections. By fixing two operators at distinct points in imaginary time τ, we have observed the evolution of the imaginary-time correlation function \(\langle {S}_{i}^{x}(\tau ){S}_{j}^{x}(0)\rangle\) with varying parameter Δ, as depicted in Fig. 6. This is achieved by evaluating the correlation function at several distinct imaginary-time points: τ = 0.1, τ = 1.0, τ = 3, and τ = 5. Notably, when β = 10, τ = β/2 = 5 corresponds to the maximum separation in imaginary time. The simulated values, directly comparable as \(\overline{Z}r/Zr\), demonstrates excellent agreement with the ED results as shown in the subfigure (a) of Fig. 6. For a larger size L = 32 with β = 64, as Δ is tuned from 1 to 0, the imaginary-time off-diagonal correlation \(\langle {S}_{i}^{x}(\tau ){S}_{i+1}^{x}(0)\rangle\) gradually becomes larger, which is analogous to the equal-time cases.

a The ratio for fixed two-point imaginary-time correlations as the parameter Δ varies in the XXZ chain, with L = 8 and β = 10. For clarity, we plotted only 15 parameter points from the dataset, each matching the ED results (black line). All data points are calculated starting from the Heisenberg condition Δ = 1. b The imaginary-time off-diagonal correlation in the XXZ chain with L = 32 and β = 64 for τ = β/4 and τ = β/8. The associated error bars ( ± 1σ) represent the standard error.

Nontrivially, we perform the BRA measurement along the imaginary-time axis, where the distance between two inserted operators increases linearly during the annealing process, as illustrated in Fig. 7(a). For example, we focus on the measurement of 〈O(τ)O(0)〉 (the operators are indicated by gradient of colors) currently inserted at time zero and τ, the corresponding partition function for this configuration is \(\overline{Z}(\tau )\). We aim to derive \(\overline{Z}({\tau }^{{\prime} })\) for the off-diagonal operator at \({\tau }^{{\prime} }\) using the reweighting technique. Different from the above schemes for reweighting in which the old/new weight uses a same configuration, the measured operators O(τ) and \(O({\tau }^{{\prime} })\) represent different configurations here. The solution is to construct an extended ensemble \(\overline{Z}(\tau )\cup \overline{Z}({\tau }^{{\prime} })\), where \(\overline{Z}(\tau )\) and \(\overline{Z}({\tau }^{{\prime} })\) are the measured ensembles containing operators O(τ) and \(O({\tau }^{{\prime} })\), as shown in Fig. 7(a). In this frame, the ratio \(\overline{Z}({\tau }^{{\prime} })/\overline{Z}(\tau )\) can be estimated by the ratio of sampling numbers \({N}_{\overline{Z}({\tau }^{{\prime} })}/{N}_{\overline{Z}(\tau )}\), where the number \({N}_{\overline{Z}(\tau )}\) or \({N}_{\overline{Z}({\tau }^{{\prime} })}\) denotes how many times the sampling belongs to the ensemble \(\overline{Z}(\tau )\) or \(\overline{Z}({\tau }^{{\prime} })\). The similar spirit has been used to calculate the entanglement entropy in QMC60. More details about this scheme are explained in the Supplementary Note 3.

a illustrates the schematic of imaginary-time BRA process. The O operators are depicted by a gradient of colors, with one instance inserted and fixed at the imaginary time τ = 0, and the other moving within the time axis. If successfully moved, it corresponds physically to a transition from the imaginary time point τ to a new time point \({\tau }^{{\prime} }\). The time difference is denoted by \(\Delta \tau={\tau }^{{\prime} }-\tau\). b The simulation results for the XXZ chain with L = 20 using imaginary-time BRA method are presented. The main plot displays the weight ratios with standard error for a fixed inverse temperature β = 40 and varying Δ = 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0. The small inset shows the weight ratios with error bars for fixed Δ = 0.1 and varying β = 2L, 3L, 4L, 5L. These results have not yet been multiplied by the reference values of \(\langle {S}_{1}^{x}(0){S}_{2}^{x}(0)\rangle\). It can be observed that when β is sufficiently large, the furthest correlation \(\langle {S}_{1}^{x}(\tau=\beta /2){S}_{2}^{x}(0)\rangle\) decays to nearly zero.

We present the numerical outcomes for the XXZ chain in Fig. 7(b). Our analysis has focused on the behavior of the weight ratio \(\overline{Z}r\), across three distinct coupling strengths: Δ = 0.1, Δ = 0.5, and the Heisenberg condition Δ = 1.0. We observe that \(\overline{Z}r\) initiates from the same starting point for all three curves, with the Heisenberg coupling exhibiting a more rapid decay which reflects the energy gaps in related cases. As Δ decreases, the imaginary-time off-diagonal correlation decays more slowly, indicating the Sx imaginary-time correlation is enhanced that is similar to the equal-time case. Moreover, the inset illustrates that, at Δ = 0.1, larger β makes the ratio \(\overline{Z}r\) closer to zero via reducing the finite size effect in imaginary-time direction.

Furthermore, we can obtain the spectrum of operators from the momentum imaginary-time correlations via stochastic analytical continuation (SAC)38,103,104. The momentum imaginary-time correlation is defined as \({G}^{\alpha \alpha }({\bf{q}},\tau )=\frac{1}{L}{\sum }_{i,j}{e}^{-i{\bf{q}}\cdot ({{\bf{r}}}_{i}-{{\bf{r}}}_{j})}\langle {s}_{i}^{\alpha }(\tau ){s}_{j}^{\alpha }(0)\rangle (\alpha=x,y,z)\). All the real-space off-diagonal imaginary-time correlation can be captured by the above imaginary-time BRA method, which is used to stimulate the excitation spectrum Sαα(q, ω). As shown in Fig. 8, the off-diagonal spectrum has sharper lower boundary with weak continuum, which is different from the diagonal spectrum that has strong spinon continuum on the upper boundary (ED results can be found in Supplementary Note 4). Since Δ = 0.1 here is close to zero, the difference of the diagonal and off-diagonal spectra can be understood qualitatively from the limit Δ = 0. When Δ = 0, the off-diagonal excitation can be solved by the Jordan-Wigner transformation, which is related to a single-mode dispersion of free fermion, thus its excitation is sharp. Meanwhile, the diagonal spectrum Szz corresponds to two fermion operators, which contributes a continuum therefore. The results demonstrate that our BRA method can be successfully applied to extract the off-diagonal spectrum, which also reveals the different excitation modes compared to the diagonal spectrum with the anisotropic phase.

Discussion

In addition to the sign problem in the original ensemble Z (denominator), the numerator \(\overline{Z}\) may also exhibit a sign problem. It involves another sign problem within this BRA measurement scheme because we have to calculate the ratio of \(\overline{Z}\) with different parameters. For example, when calculating the operator \({\sigma }^{y}=-i| \uparrow \rangle \langle \downarrow |+i| \downarrow \rangle \langle \uparrow |\), it introduces an extra sign of i or − i into the weight, contrasting with the case of \({\sigma }^{x}=| \uparrow \rangle \langle \downarrow |+| \downarrow \rangle \langle \uparrow |\). If we attempt to reweight the general PF containing the measured operator σy, denoted as \({\overline{Z}}_{y}\), the simulation of ratio \({\overline{Z}}_{y}({J}^{{\prime} })/{\overline{Z}}_{y}(J)\) would encounter sign problem. A simple way is to calculate the ratio of \({\overline{Z}}_{y}/{\overline{Z}}_{x}\), where \({\overline{Z}}_{x}\) is the ensemble with the measured operator σy replaced by σx. Note that \({\overline{Z}}_{y}={\sum }_{i}{W}_{i}\) and \({\overline{Z}}_{x}={\sum }_{i}| {W}_{i}|\). As is commonly used in calculating sign value45,47,48,105, \({\overline{Z}}_{y}\) represents the sign system and \({\overline{Z}}_{x}\) is the reference system. The ratio \({\overline{Z}}_{y}/{\overline{Z}}_{x}\) can then be extracted by sampling the reference system \({\overline{Z}}_{x}={\sum }_{i}| {W}_{i}|\), averaging the sign of each configuration in the sign system (\({\overline{Z}}_{y}={\sum }_{i}{W}_{i}={\sum }_{i}{sign}_{i}| {W}_{i}|\)), and ultimately obtaining \({\overline{Z}}_{y}/{\overline{Z}}_{x}=\langle sign\rangle\). Finally, the target observable \({\overline{Z}}_{y}/Z\) can be derived via \({\overline{Z}}_{y}/{\overline{Z}}_{x}\times {\overline{Z}}_{x}/Z\).

In summary, we propose a variety of detailed schemes in the frame of bipartite reweight-annealing to achieve universal measurement by QMC simulation. Typically, we perform annealing along a physical parameter for the PFs \(\overline{Z}(J)\) and Z(J) independently, then connect them via an easily solvable point such as \(\overline{Z}({J}^{{\prime} })/Z({J}^{{\prime} })\). Thereafter, this concept has been extended to annealing of system size and imaginary time. For example, it is easy to employ ED to calculate the observables in each independent parts and anneal their couplings to construct a large system and solve the target measurement problem. The dynamical behaviors of off-diagonal operators have also been addressed in this work. Off-diagonal spectrum is no longer a natural moat in the quantum many-body computation. Within this framework, the long-standing problem for the measurement of QMC has been addressed in a general way.

Essentially, we solve the problem of calculating the overlap between different distribution functions, which is a fundamental challenge in mathematical statistics. The spirit of BRA can be easily generalized to the measurement of entanglement106,107,108 and other statistical problems, such as machine learning109,110,111.

Methods

Our work proposes a general measurement framework based on the SSE-QMC method, the principle of which has been introduced in the main text. The XXZ model and TFIM model involved employ directed-Loop algorithm and cluster SSE algorithm (detail can be found in Supplementary Note 1 and Note 6), respectively, which will be found in detail in the supplementary information.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study have been archived on Zenodo112 with the https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17669618.

Code availability

All code related to this work is available from the authors.

References

Ceperley, D. & Alder, B. Quantum Monte Carlo. Science 231, 555–560 (1986).

Sandvik, A. W. & Kurkijärvi, J. Quantum Monte Carlo simulation method for spin systems. Phys. Rev. B 43, 5950 (1991).

Ceperley, D. M. Path integrals in the theory of condensed helium. Rev. Mod. Phys. 67, 279–355 (1995).

Gubernatis, J., Kawashima, N. & Werner, P. Quantum Monte Carlo Methods. (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Foulkes, W. M. C., Mitas, L., Needs, R. J. & Rajagopal, G. Quantum Monte Carlo simulations of solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 33–83 (2001).

Blöte, H. W. J. & Deng, Y. Cluster Monte Carlo simulation of the transverse Ising model. Phys. Rev. E 66, 066110 (2002).

Sandvik, A. W. Computational studies of quantum spin systems. AIP Conf. Proc. 1297, 135–338 (2010).

Carlson, J. et al. Quantum monte carlo methods for nuclear physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1067–1118 (2015).

Syljuåsen, O. F. & Sandvik, A. W. Quantum Monte Carlo with directed loops. Phys. Rev. E 66, 046701 (2002).

Evertz, H. G. The loop algorithm. Adv. Phys. 52, 1–66 (2003).

Assaad, F.F. & Evertz, H.G.World-line and Determinantal Quantum Monte Carlo Methods for Spins, Phonons and Electrons, pages 277–356. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-540-74686-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74686-7_10 (2008).

Yan, Z. et al. Sweeping cluster algorithm for quantum spin systems with strong geometric restrictions. Phys. Rev. B 99, 165135 (2019).

Yan, Z. Global scheme of sweeping cluster algorithm to sample among topological sectors. Phys. Rev. B 105, 184432 (2022).

Prokof’Ev, N. V., Svistunov, B. V. & Tupitsyn, I. S. Exact, complete, and universal continuous-time worldline Monte Carlo approach to the statistics of discrete quantum systems. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 87, 310–321 (1998).

Sadoune, N. & Pollet, L. Efficient and scalable path integral Monte Carlo simulations with worm-type updates for Bose-Hubbard and XXZ models. SciPost Phys. Codebases, page 9. https://doi.org/10.21468/SciPostPhysCodeb.9 (2022).

Melko, R. G. Stochastic Series Expansion Quantum Monte Carlo, pages 185–206. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-642-35106-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-35106-8_7 (2013).

Blankenbecler, R., Scalapino, D. J. & Sugar, R. L. Monte Carlo calculations of coupled boson-fermion systems. i. Phys. Rev. D. 24, 2278–2286 (1981).

Scalapino, D. J. & Sugar, R. L. Monte Carlo calculations of coupled boson-fermion systems. ii. Phys. Rev. B 24, 4295–4308 (1981).

Hirsch, J. E. Two-dimensional Hubbard model: numerical simulation study. Phys. Rev. B 31, 4403–4419 (1985).

Zhang, S. Finite-temperature Monte Carlo calculations for systems with fermions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 2777–2780 (1999).

He, Y. Y., Qin, M., Shi, H., Lu, Z. Y. & Zhang, S. Finite-temperature auxiliary-field quantum Monte Carlo: self-consistent constraint and systematic approach to low temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 99, 045108 (2019).

Shao, H., Guo, W. & Sandvik, A. W. Quantum criticality with two length scales. Science 352, 213–216 (2016).

Ma, N. et al. Anomalous quantum-critical scaling corrections in two-dimensional antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 117202 (2018).

Cheng, J. Q. et al. Fractional and composite excitations of antiferromagnetic quantum spin trimer chains. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 3 (2022).

Ding, C., Zhang, L. & Guo, W. Engineering surface critical behavior of (2 + 1)-dimensional o(3) quantum critical points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 235701 (2018).

Merali, E., De Vlugt, I. J. S. & Melko, R. G. Stochastic series expansion quantum Monte Carlo for Rydberg arrays. SciPost Phys. Core 7, 016 (2024).

Sandvik, A. W. Stochastic series expansion method for quantum Ising models with arbitrary interactions. Phys. Rev. E 68, 056701 (2003).

Xu, W. & Zhang, X.-F. Loop algorithm for quantum transverse Ising model in a longitudinal field. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.17835. (2024).

Fan, Z., Zhang, C. & Deng, Y. Clock factorized quantum Monte Carlo method for long-range interacting systems. https://scipost.org/10.21468/SciPostPhysCore.8.2.036. (2025).

Sandvik, A. W. Stochastic series expansion methods. https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.10591. (2019).

Sun, F. & Xu, X.Y. Delay update in determinant quantum Monte Carlo. Phys. Rev. B 109, 235140 (2024).

Sun, F. and Xu, X. Y. Boosting determinant quantum Monte Carlo with submatrix updates: Unveiling the phase diagram of the 3D Hubbard model. https://scipost.org/10.21468/SciPostPhys.18.2.055 (2025).

Song, Y.-F., Deng, Y. & He, Y.-Y. Extended metal-insulator crossover with strong antiferromagnetic spin correlation in half-filled 3D Hubbard model. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.016503 (2025).

Li, Z. X., Jiang, Y. F. & Yao, H. Solving the fermion sign problem in quantum Monte Carlo simulations by majorana representation. Phys. Rev. B 91, 241117 (2015a).

Li, Z. X. & Yao, H. Sign-problem-free fermionic quantum monte carlo: developments and applications. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 337–356 (2019).

Liu, J., Qi, Y., Meng, Z. Y. & Fu, L. Self-learning Monte Carlo method. Phys. Rev. B 95, 041101 (2017).

Xu, X. Y., Qi, Y., Liu, J., Fu, L. & Meng, Z. Y. Self-learning quantum Monte Carlo method in interacting fermion systems. Phys. Rev. B 96, 041119 (2017).

Shao, H. & Sandvik, A. W. Progress on stochastic analytic continuation of quantum Monte Carlo data. Physics Reports 1003, 1-88 (2023). Progress on stochastic analytic continuation of quantum Monte Carlo data.

Deng, Z., Liu, L., Guo, W. & Lin, H. Q. Improved scaling of the entanglement entropy of quantum antiferromagnetic Heisenberg systems. Phys. Rev. B 108, 125144 (2023).

Deng, Z., Liu, L., Guo, W. & Lin, H. ai-Q. ing Diagnosing quantum phase transition order and deconfined criticality via entanglement entropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 100402 (2024).

Chen, T., Guo, E., Zhang, W., Zhang, P. Deng, Y. Tensor network Monte Carlo simulations for the two-dimensional random-bond Ising model. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevB.111.094201 (2025).

Loh, E. Y. et al. Sign problem in the numerical simulation of many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 41, 9301–9307 (1990).

Takasu, M., Miyashita, S. & Suzuki, M. Monte Carlo simulation of quantum Heisenberg magnets on the triangular lattice. Prog. Theor. Phys. 75, 1254–1257 (1986).

Hatano, N. & Suzuki, M. Representation basis in quantum Monte Carlo calculations and the negative-sign problem. Phys. Lett. A 163, 246–249 (1992).

Iglovikov, V. I., Khatami, E. & Scalettar, R. T. Geometry dependence of the sign problem in quantum Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. B 92, 045110 (2015).

Henelius, P. & Sandvik, A. W. Sign problem in Monte Carlo simulations of frustrated quantum spin systems. Phys. Rev. B 62, 1102–1113 (2000).

Pan, G. and Meng, Z. Y. The sign problem in quantum Monte Carlo simulations. pages 879–893, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90800-9.00095-0. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323908009000950.

Ma, N., Sun, J. S., Pan, G., Cheng, C. & Yan, Z. Defining a universal sign to strictly probe a phase transition. Phys. Rev. B 110, 125141 (2024).

Wu, C. & Zhang, S. C. Sufficient condition for absence of the sign problem in the fermionic quantum Monte Carlo algorithm. Phys. Rev. B 71, 155115 (2005).

Wei, Z. C., Wu, C., Li, Y., Zhang, S. & Xiang, T. Majorana positivity and the fermion sign problem of quantum Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 250601 (2016).

Wessel, S. et al. Thermodynamic properties of the Shastry-Sutherland model from quantum Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. B 98, 174432 (2018).

D’Emidio, J., Wessel, S. & Mila, F. Reduction of the sign problem near t = 0 in quantum Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. B 102, 064420 (2020).

Li, Z. X., Jiang, Y. F. & Yao, H. Fermion-sign-free Majorana-quantum-monte-carlo studies of quantum critical phenomena of Dirac fermions in two dimensions. N. J. Phys. 17, 085003 (2015b).

Wan, Z. Q., Zhang, S. X. & Yao, H. Mitigating the fermion sign problem by automatic differentiation. Phys. Rev. B 106, L241109 (2022).

Zhang, X., Pan, G., Xu, X. Y. & Meng, Z. Y. Fermion sign bounds theory in quantum Monte Carlo simulation. Phys. Rev. B 106, 035121 (2022).

Wessel, S., Normand, B., Mila, F. & Honecker, A. Efficient Quantum Monte Carlo simulations of highly frustrated magnets: the frustrated spin-1/2 ladder. SciPost Phys. 3, 005 (2017).

Alet, F., Damle, K. & Pujari, S. Sign-problem-free Monte Carlo simulation of certain frustrated quantum magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 197203 (2016).

Mondaini, R., Tarat, S. & Scalettar, R. T. Quantum critical points and the sign problem. Science 375, 418–424 (2022).

Avella, A. et al. Strongly Correlated Systems. Springer, (2012).

Humeniuk, S. & Roscilde, T. Quantum Monte Carlo calculation of entanglement rényi entropies for generic quantum systems. Phys. Rev. B 86, 235116 (2012).

Chang, C. C., Gogolenko, S., Perez, J., Bai, Z. & Scalettar, R. T. Recent advances in determinant quantum Monte Carlo. Philos. Mag. 95, 1260–1281 (2015).

Van Houcke, K., Kozik, E., Prokof’ev, N. & Svistunov, B. Diagrammatic Monte Carlo. Phys. Procedia 6, 95–105 (2010).

Kozik, E. et al. Diagrammatic Monte Carlo for correlated fermions. Europhys. Lett. 90, 10004 (2010).

Werner, P., Oka, T. & Millis, A. J. Diagrammatic Monte Carlo simulation of nonequilibrium systems. Phys. Rev. B 79, 035320 (2009).

Prokof’ev, N. & Svistunov, B. Worm algorithm for problems of quantum and classical statistics. Understanding Quantum Phase Transitions, Lincoln D. Carr, ed. Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, 910, (2010).

Boninsegni, M., Prokof’ev, N. V. & Svistunov, B. V. Worm algorithm and diagrammatic Monte Carlo: A new approach to continuous-space path integral Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. E 74, 036701 (2006).

Gunacker, P. et al. Continuous-time quantum Monte Carlo using worm sampling. Phys. Rev. B 92, 155102 (2015).

Dorneich, A. & Troyer, M. Accessing the dynamics of large many-particle systems using the stochastic series expansion. Phys. Rev. E 64, 066701 (2001).

Zhou, C. et al. Amplitude mode in quantum magnets via dimensional crossover. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 227201 (2021).

Zhu, W. & Guo, W. Measuring off-diagonal correlation function in stochastic series expansion quantum Monte Carlo simulation. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. 57, 593–600 (2021).

Syljuåsen, O. F. Directed loop updates for quantum lattice models. Phys. Rev. E 67, 046701 (2003).

Henelius, P., Fröbrich, P., Kuntz, P. J., Timm, C. & Jensen, P. J. Quantum Monte Carlo simulation of thin magnetic films. Phys. Rev. B 66, 094407 (2002).

Huang, C. J., Liu, L., Jiang, Y. & Deng, Y. Worm-algorithm-type simulation of the quantum transverse-field Ising model. Phys. Rev. B 102, 094101 (2020).

Sandvik, A. W. A generalization of Handscomb’s quantum Monte Carlo scheme-application to the 1D Hubbard model. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 25, 3667 (1992).

Yan, Z., Wang, Y. C., Samajdar, R., Sachdev, S. & Meng, Z. Y. Emergent glassy behavior in a kagome Rydberg atom array. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 206501 (2023a).

Yan, Z., Samajdar, R., Wang, Y. C., Sachdev, S. & Meng, Z. Y. Triangular lattice quantum dimer model with variable dimer density. Nat. Commun. 13, 5799 (2022).

Ding, Y. M. et al. Reweight-annealing method for evaluating the partition function via quantum Monte Carlo calculations. Phys. Rev. B 110, 165152 (2024a).

Neal, R. M. Annealed importance sampling. Stat. Comput. 11, 125–139 (2001).

de Forcrand, P., D’Elia, M. & Pepe, M. ’t hooft loop in su(2) yang-mills theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 1438–1441 (2001).

de Forcrand, P., Lucini, B. & Vettorazzo, M. Measuring interface tensions in 4d su(n) lattice gauge theories. Nucl. Phys. B Proc. Suppl. 140, 647–649 (2005).

de Forcrand, P. & Noth, D. Precision lattice calculation of su(2) ’t hooft loops. Phys. Rev. D. 72, 114501 (2005).

Caselle, M., Hasenbusch, M. & Panero, M. String effects in the 3d gauge Ising model. J. High. Energy Phys. 2003, 057 (2003).

Dai, Z. & Xu, X. Y. Residual entropy from the temperature incremental Monte Carlo method, Feb (2025) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevB.111.L081108.

Mon, K. K. Direct calculation of absolute free energy for lattice systems by Monte Carlo sampling of finite-size dependence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 54, 2671–2673 (1985).

Alet, F., Wessel, S. & Troyer, M. Generalized directed loop method for quantum Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. E 71, 036706 (2005).

Syljuåsen, O. F. & Zvonarev, M. B. Directed-loop Monte Carlo simulations of vertex models. Phys. Rev. E 70, 016118 (2004).

Das, A. & Chakrabarti, B. K. Colloquium: quantum annealing and analog quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1061–1081 (2008).

Yan, Z. et al. Quantum optimization within lattice gauge theory model on a quantum simulator. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 89 (2023b).

Ding, Y. M., Wang, Y. C., Zhang, S. X. & Yan, Z. Exploring the topological sector optimization on quantum computers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 034031 (2024b).

Weinberg, P. & Bukov, M. QuSpin: a Python package for dynamics and exact diagonalisation of quantum many body systems part I: spin chains. SciPost Phys. 2, 003 (2017).

Weinberg, P. & Bukov, M. QuSpin: a Python package for dynamics and exact diagonalisation of quantum many body systems. Part II: bosons, fermions and higher spins. SciPost Phys. 7, 020 (2019).

Zhao, J., Yan, Z., Cheng, M. & Meng, Z. Y. Higher-form symmetry breaking at Ising transitions. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 033024 (2021).

Wang, Y. C., Cheng, M. & Meng, Z. Y. Scaling of the disorder operator at (2 + 1)d u(1) quantum criticality. Phys. Rev. B 104, L081109 (2021).

Wang, Y. C., Ma, N., Cheng, M. & Meng, Z. Y. Scaling of the disorder operator at deconfined quantum criticality. SciPost Phys. 13, 123 (2022).

Jiang, W. et al. Many versus one: the disorder operator and entanglement entropy in fermionic quantum matter. SciPost Phys. 15, 082 (2023).

Liu, Z. H. et al. Fermion disorder operator at Gross-Neveu and deconfined quantum criticalities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 266501 (2023).

Liu, Z. H. et al. Disorder operator and rényi entanglement entropy of symmetric mass generation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 156503 (2024a).

Liu, Z., Huang, R. Z., Wang, Y. C., Yan, Z. & Yao, D. X. Measuring the boundary gapless state and criticality via disorder operator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 206502 (2024b).

Wu, X. C., Jian, C. M. & Xu, C. Universal features of higher-form symmetries at phase transitions. SciPost Phys. 11, 033 (2021).

Lake, E. Higher-form symmetries and spontaneous symmetry breaking, (2018). https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.07747.

Fradkin, E. Disorder operators and their descendants. J. Stat. Phys. 167, 427–461 (2017).

Estienne, B., Stéphan, J. M. & Witczak-Krempa, W. Cornering the universal shape of fluctuations. Nat. Commun. 13, 287 (2022).

Shao, H. et al. Nearly deconfined spinon excitations in the square-lattice spin-1/2 Heisenberg antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041072 (2017).

Sandvik, A. W. Constrained sampling method for analytic continuation. Phys. Rev. E 94, 063308 (2016).

Zhou, Z. et al. Universal critical behavior in the ferromagnetic superconductor \(Eu{({fe}_{0.75}{ru}_{0.25})}_{2}{as}_{2}\). Phys. Rev. B 100, 060406 (2019).

Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Ding, Y-M, Mao, B-B, & Yan, Z. Bipartite reweight-annealing algorithm of quantum Monte Carlo to extract large-scale data of entanglement entropy and its derivative, (2025a). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61084-7.

Ding, Y.-M. et al. Tracking the variation of entanglement rényi negativity: a quantum Monte Carlo study, Jun (2025). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.111.L241108.

Jiang, W. et al. High-efficiency quantum Monte Carlo algorithm for extracting entanglement entropy in interacting fermion systems, (2024). https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.20009.

Surden, H. Chapter 8: Machine learning and law: An overview. In Research Handbook on Big Data Law. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK, (2021). ISBN 9781788972819. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788972826.00014. https://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9781788972819/9781788972819.00014.xml.

Zhou, Z.-H. Machine learning. (Springer Nature, 2021).

Mahesh, B. Machine learning algorithms-a review. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR). [Internet] 9, 381–386 (2020).

Wang, Z., Liu, Z., Mao, B-B, Wang, Z. & Yan, Z. BRA-SSE-off-diagonal (data for this paper). (2025b). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17669618.

Acknowledgements

We thank Youjin Deng, Wenan Guo, Yi-Ming Ding and Xuyang Liang for helpful discussions. Zenan Liu thanks the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grants No.2024M762935 and NSFC Special Fund for Theoretical Physics under Grants No.12447119. Zhe Wang thanks the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grants No.2024M752898. This project is supported by the Scientific Research Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of the Education Department of Anhui Province (No.2022AH020008), the Scientific Research Project (No.WU2024B027) and the Start-up Funding of Westlake University. The authors thank the high-performance computing center of Westlake University and the Beijing PARATERA Tech Co., Ltd. for providing HPC resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. (Zhiyan Wang) and Z.L. contribute equally in this work. Z.Y. initiated the project and conceived the central idea of the BRA algorithm. Z.W. (Zhiyan Wang) and Z.L. developed the algorithmic implementation, performed the large-scale quantum Monte Carlo simulations, and analyzed the results. B.B.M. carried out the excitation spectrum from exact diagonalization calculations. Z.W. (Zhe Wang) contributed to the analysis and discussion of the results. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and to the writing of the manuscript. Z.Y. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Liu, Z., Mao, BB. et al. Addressing general measurements in quantum Monte Carlo. Nat Commun 17, 679 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67324-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67324-0