Abstract

With the advent and development of assisted reproductive technology (ART), more and more people affected by infertility have been able to obtain offspring successfully. Nevertheless, various adverse outcomes have been found to be associated with ART, and mechanisms behind them are still unclear. Therefore, in this study, we examine the differences between mouse pre-implantation embryos obtained via in vitro fertilization (IVF) and in vivo fertilization (IVO) at both transcriptional and epigenetic levels. We find remarkable H3K4me3 differences at blastocyst stage, which could be ascribed to the higher oxidative stress in IVF-derived blastocysts. Intriguingly, treatment with CPI-455, the inhibitor of KDM5 that catalyzes the demethylation of H3K4, successfully rescues the H3K4me3 signatures as well as transcription levels of several genes, facilitating embryo development in vitro and improving the pregnancy outcome. Consistently, CPI-455 supplementation also enhances the formation of high-quality human embryos, emphasizing the potential clinical application of CPI-455 in human ART.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the prevalence of infertility has gradually increased and assisted reproductive technology (ART), mainly including in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), have been widely applied to tackle this issue1,2. Although the majority of offspring conceived via ART seem to be healthy, at the same time, many studies have revealed several adverse outcomes associated with ART, such as low birth weight3,4, abnormal placenta5, impaired insulin sensitivity6 and shorter leukocyte telomere length7,8. However, the potential mechanisms behind such phenomena are still unclear. In fact, during embryo development, the epigenetic landscape, including DNA methylation9, H3K4me3 and H3K27me310, undergoes dramatic and regular reorganization11,12, ensuring precise gene transcription. Researchers thus speculated that the adverse outcomes observed may be related to the improper establishment of epigenetic landscape in ART-conceived embryos as environmental exposures and manipulations in ART could result in epigenetic changes13. Accordingly, perturbations of epigenetic markers have been indeed uncovered in ART-conceived samples13,14,15,16,17, which may consequently affect the transcription of specific genes, such as imprinted genes18. For instance, based on a large cohort accommodating ~1000 ART-conceived and ~1000 spontaneously conceived singleton newborns, widespread DNA methylation differences were observed in cord blood and genes harboring them were indeed associated with the adverse outcomes linked to ART19. Besides, in contrast to natural conceptions, altered global DNA methylation levels have also been observed in IVF-conceived placenta20. A recent work21 with a total of 80 ART and 77 control placentas further identified 6814 significantly differentially methylated CpG sites and 822 differentially methylated regions (DMRs). Functions of genes related to ART-associated DMRs were involved in cell-cell adhesion and tissue development. Of note, previous studies19,22 also proved that the observed DNA methylation differences between ART and natural conceptions could be attributed to ART protocols instead of underlying infertility. Taken together, these studies indeed revealed the potential effects of ART on human DNA methylation landscape.

Of note, most of these studies focused on placenta or cord blood due to their accessibility during delivery process with few studies examining early pregnancy (first-trimester) tissues, such as chorionic villus23,24,25. However, how ART-conceived embryos differed from those conceived spontaneously at much earlier stage (i.e., pre-implantation and peri-implantation) remains largely unknown26, and understanding their differences may provide clues on how to improve the quality of ART-conceived embryos and thus reduce adverse outcomes.

Hence, in this study, we examined the differences between pre-implantation embryos obtained via IVF and IVO (in vivo fertilization) by means of a mouse model. We show that gene transcription from PN5 to morula was highly comparable, except at the late 2-cell stage. At the blastocyst stage, expression of marker genes for both the inner cell mass (ICM) and the trophectoderm (TE) was dysregulated in IVF-derived embryos. Such a phenomenon, together with the imbalance in cell compositions unveiled by our scRNA-seq data in post-implantation embryos, may all be due to the failure of Carm1 activation during zygotic genome activation (ZGA) given that Carm1 has been suggested to play an essential role in mediating the first lineage segregation27,28. On the other hand, at epigenetic level, global and dramatic H3K4me3 differences were observed at blastocyst stage, which was associated with the higher level of oxidative stress in IVF-derived blastocysts. We then checked the effects of the supplementation of CPI-455, the inhibitor of KDM529, on mouse embryo development. At last, we focused on human day 5- and day 6-blastocysts obtained via ART and found their differences resembled those between mouse IVF- and IVO-derived blastocysts in many ways.

Results

Moderate transcriptional differences between IVO- and IVF-derived embryos except the late 2-cell stage

At the beginning of this study, we wondered how and to what extent IVF-derived embryos differed from those obtained via IVO at transcription level. To this end, we firstly performed Smart-seq2 on several stages including PN5, early 2-cell, late 2-cell, 4-cell, 8-cell and morula (Fig. 1a). PCA result manifested a clear developmental trajectory (Fig. 1b) and then, based on gene expression dynamics, we divided genes into 10 clusters regarding transcriptomics obtained from IVO-embryos as gold standard (Supplementary Fig. 1a), and calculated the expression correlation of each gene between IVF and IVO within each cluster. In general, similar patterns were observed (Fig. 1c) and consistently, the median values of correlation coefficient for each cluster exceeded 0.8, except for cluster 8 (median value: 0.79, Fig. 1d).

a A schematic representation summarizing the multi-omics data we generated in this study to investigate the differences between IVF- and IVO-conceived embryos. Illustration was created in BioRender. Zhang, C. (https://biorender.com/3l307ne). b PCA on transcription data from PN5 to morula (n = 3 biological replicates for each condition). c Heatmaps showing the dynamics of gene transcription from PN5 to morula following IVF or IVO. d Quantitative correlation analysis of each gene in (c). The number of genes from cluster 1 to cluster 10 is 1229, 1575, 2307, 2144, 1470, 1644, 1747, 1272, 2773 and 1544, respectively. The line inside of each box is the sample median and the top and bottom edges of each box are the 0.75 and 0.25 quartiles, respectively. The distance between the top and bottom edges is the interquartile range (IQR). The whiskers are lines that extend above and below each box within 1.5 times the IQR and outliers are values that are more than 1.5 times the IQR away from the top or bottom of the box. e The number of DEGs (differentially expressed genes) identified based on the comparison of IVF- and IVO-conceived embryos at each stage. f, g Heatmap (f) and boxplot (g) exhibiting the expression variation of genes within group 2 during ZGA process. T-test (both-tail) was performed. The line inside of each box is the sample median and the top and bottom edges of each box are the 0.75 and 0.25 quartiles, respectively. The distance between the top and bottom edges is the interquartile range (IQR). The whiskers are lines that extend above and below each box within 1.5 times the IQR and outliers are values that are more than 1.5 times the IQR away from the top or bottom of the box. N = 562.

On the other hand, at each stage, we also identified DEGs (differentially expressed genes) between IVF and IVO (Fig. 1e), the number of which were generally low, except for late 2-cell, where dramatic differences were observed. Such a phenomenon may indicate the perturbation of ZGA in IVF and therefore, DEGs between early 2-cell and late 2-cell were further identified (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Through the comparison of them, we found that activated genes were highly conserved between IVF and IVO (group 1) while there still existed several groups of DEGs specific to IVO/IVF (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Further inspection revealed those genes exhibited similar transcription variation between IVF and IVO during ZGA. For instance, 562 genes (group 2) were activated in IVO late 2-cell and a similar tendency was also observed in IVF-derived embryos, but to a much less extent, indicating the inadequate activation (Fig. 1f, g and Supplementary Fig. 1b). The functions of these genes were mainly related to “energy” and “RNA splicing” (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Likewise, compared to IVO, 3083 genes (group 3), functions of which included cell development, suffered more severe repression in IVF late 2-cell (Supplementary Figs. 1b, d–f).

Together, our results indicated the gene transcription landscape was generally similar between IVF and IVO during early embryo development from PN5 to morula, except late 2-cell.

Several genes are dysregulated in IVF-derived blastocysts

We next focused on blastocyst, which is generally the terminus of in vitro operation and will be transferred into the uterus in ART30, aiming to elucidate the differences between IVF and IVO and thus provide possible strategy for the improvement of embryo quality. Firstly, accordant with previous studies31, we found IVF-derived blastocysts were characterized by lower cell numbers (Supplementary Fig. 2a). In fact, to better link our study to clinical practice, in which blastocyst at stage four (see methods for detailed definition) was practically transferred to the uterus, we particularly selected this stage of blastocysts for subsequent analysis. Likewise, the number of total cells, ICM cells and TE cells remained lower in IVF-derived stage four blastocyst (Fig. 2a).

a Upper: Representative light microscopy and immunofluorescence images of the EPI markers OCT4 (red), the TE markers CDX2 (green) and nuclear stain DAPI (blue) in mouse stage four blastocyst conceived from IVO and IVF. Scale bars, 30 μm; lower: quantification of the number of total, ICM and TE cells in mouse stage four blastocyst conceived from IVO and IVF. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Error bar: mean ± std. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed. b PCA on gene transcription data at blastocyst stage. N = 3 biological replicates for each condition. c Gene function analysis performed on IVO-expressed genes. P-adjust was calculated based on hypergeometric distribution with BH (Benjamini-Hochberg) correction. d, e Staining and quantification for ROS (d) and GSH (e) in IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocysts. Scale bars, 60 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Error bar: mean ± std. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed. f Sequence motif analysis on the promoter regions of IVO-expressed genes. P values were obtained based on hypergeometric distribution. g The expression level of several genes, including Pou5f1, Nanog, Eomes, Kdm5a, Kdm6b and Tet3, in IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocysts. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To gain more insights into the above phenomena, we further performed Smart-seq2 experiments and identified 697 DEGs with 286 and 411 genes being specifically expressed in IVO- and IVF-derived blastocysts, respectively (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Remarkably, these two groups of genes exhibited opposite transcription dynamics from PN5 to morula with IVO- and IVF-expressed genes being highly transcribed at the later and earlier stages, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d). Gene function analysis further revealed genes related to “response to oxidative stress”, “cell redox homeostasis”, and various kinds of metabolic processes were dysregulated in IVF-conceived blastocysts (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2e). Consistently, we also found IVF-conceived blastocysts were characterized by higher level of ROS31 (reactive oxygen species) and lower levels of GSH (glutathione), NAD+, NADH and ATP concentration (Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Fig. 2f). These results thus indicate higher oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in IVF-conceived blastocysts, potentially attributable to the in vitro operation and exposure. Intriguingly, sequence motif analysis indeed revealed the enrichment of Bach1 and Nrf2 in the promoter regions of IVO-expressed genes (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 2g), both of which have been suggested to play crucial roles in dealing with oxidative stress32. On the other hand, ICM marker genes, such as Pou5f1 and Nanog, and TE marker gene, Eomes, exhibited lower and higher expression levels in IVF-conceived blastocysts, respectively (Fig. 2g). Such a phenomenon may be associated with the failure of activation of Carm1 during ZGA process following IVF (Supplementary Figs. 2h,i), as the precise achievement of first lineage segregation has been ascribed to, at least partially, the asymmetric expression of Carm1 in two- and four-cell embryos with higher and lower Carm1 expression directing the activation of pluripotency and differentiation genes, respectively, and thus the formation of ICM and TE27,28,33. Therefore, the lower Carm1 expression level may bias the embryo development towards the formation of TE and result in the higher expression level of TE marker gene Eomes. In summary, our data revealed several categories of genes suffered dysregulation in IVF-conceived blastocysts.

Abnormal epigenetic landscape in IVF-derived blastocyst

Of note, we found several genes, including Kdm5a, Kdm6b and Tet3, related to the establishment of chromatin epigenetic landscape, were dysregulated in IVF-conceived blastocysts (Fig. 2g), which may result in the reconfiguration of epigenetic modifications. We thus firstly examined the distribution of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 given that Kdm5a and Kdm6b are responsible for the demethylation of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, respectively. Immunofluorescence staining targeting H3K4me3 indeed revealed significant lower intensity in IVF-conceived blastocyst (Fig. 3a), which was further validated by ULI-NChIP-seq experiments showing dramatic and global reduction of H3K4me3 following IVF (Fig. 3b, c). In detail, we performed differential analysis regarding IVF-conceived blastocyst as control and identified 14342 differentially H3K4me3-binding regions, all of which underwent H3K4me3 loss following IVF (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Besides, both up- and down-regulated genes exhibited lower H3K4me3 signals in their promoter regions following IVF (Supplementary Fig. 3b). In contrast, IVF-conceived blastocysts harbored higher H3K27me3 signals, however, such a difference was much weaker compared to that of H3K4me3 given that only 54 differentially regions were identified (all of them possessed higher H3K27me3 signals in IVF-conceived blastocysts) (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figs. 3c-e).

a Staining and quantification for H3K4me3 in IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocysts. Scale bar, 30 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Error bar: mean ± std. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed. b A snapshot showing the distribution of H3K4me3 signals in IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocysts (n = 2 biological replicates for each condition). c, d Heatmaps showing the distribution of H3K4me3 (c) and H3K27me3 (d) around peaks. e Four states identified by means of chromHMM method. f The overlap of bivalent regions between IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocysts. g A schematic diagram showing our speculation that the disruption of epigenetic landscape in IVF-conceived blastocyst leads to the perturbation of bivalent state around promoter regions and consequently the subsequent gene expression levels will be affected. Illustration was created in BioRender. Zhang, C. (https://biorender.com/06jhmm4). h The global DNA methylation level (inner panel) as well as the DNA methylation distribution around genes in IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocysts (n = 2 biological replicates for each condition). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We then applied chromHMM34 method, leveraging H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 ULI-NChIP-seq data, and identified four distinct chromatin states (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 3f). Consistently, the length of repressive (decorated by H3K27me3, state 2) and active (decorated by H3K4me3, state 4) regions increased and diminished in IVF-generated blastocysts, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3g). In fact, during embryo development, bivalent genome (state 3), which are typically decorated by both H3K4me3 (active) and H3K27me3 (repressive) signals, have been suggested to play vital roles in ensuring precise gene transcription11,35. The disruption of the landscape of both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 in IVF-conceived blastocysts may affect bivalent regions (Fig. 3f) and consequently the proper gene regulation in the subsequent developmental process (Fig. 3g). Indeed, we found bivalent regions were highly variable between IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocysts (Fig. 3f). For instance, Pnpt1 is involved in the processing and degradation of RNA and is associated with system development. The promoter region of Pnpt1 was in a bivalent state in IVO but repressive state in IVF (Supplementary Fig. 3h), and compared to pre-implantation blastocyst, this gene tends to be up-regulated in E6.5 epiblast36 (Supplementary Fig. 3i), which may be achieved via the removal of H3K27me3. In this case, Pnpt1 may be activated inadequately in IVF-conceived embryos, which was indeed validated using our scRNA-seq data (Supplementary Fig. 3j) that will be introduced below in detail. Taken together, we speculated that for IVF-conceived embryos, some genes may be regulated inappropriately in subsequent biological processes, the consequence of bivalency disruption in blastocyst stage.

Besides, the aberrant Tet3 expression in IVF-conceived blastocyst (Supplementary Fig. 3k) let us further perform WGBS experiments to interrogate the DNA methylation differences following IVF and IVO. We firstly found that IVF-derived blastocysts possessed lower DNA methylation levels (Fig. 3h), which was consistent with the results derived from previously published datasets37,38 (Supplementary Fig. 3l). Next, we further identified differentially methylated regions (DMR) regarding IVF as control (Supplementary Fig. 3m). Intriguingly, compared to randomly selected regions, hyper-DMRs (genome regions harboring higher DNA methylation in IVO) tended to bind Tet339 (Supplementary Fig. 3n), thus we speculated that in IVF, Tet3 was highly expressed and capable of binding the hyper-DMRs regions, resulting in the lower DNA methylation. In IVO, the expression level of Tet3 became very low, eliciting the hypermethylation behaviors we finally observed. At last, promoter regions of dysregulated genes were much closer to DMRs (Supplementary Fig. 3o), indicating a possible link between DNA methylation and gene transcription.

In summary, our data revealed the disruption of the patterns of H3K27me3, DNA methylation and especially H3K4me3 in IVF-conceived blastocysts.

Aberrant cell compositions in IVF-derived post-implantation embryos

The preceding results revealed the reconfiguration of the landscape of gene transcription and epigenetics in IVF-conceived blastocysts, for instance, the dysregulation of both ICM and TE marker genes, the effects of which on subsequent developmental process thus become an interesting and open question. To address it, blastocysts derived both in vivo and in vitro were cultured by means of our previously established in vitro culture (IVC) system40. Following 48-h cultivation in IVC1 and IVC2 media, respectively, the embryos at stages analogous to E6.5-E7.5 in vivo were harvested (Fig. 4a). Light microscopy and immunofluorescence analyses revealed that although both IVF- and IVO-derived embryos exhibited normal tri-lineage structures, including epiblast, primitive endoderm, and trophectoderm, following in vitro delayed culture, nevertheless, IVF embryos exhibited reduced size relative to IVO embryos (Fig. 4b–d). We then collected these embryos and performed single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq). Based on it, we identified 11 cell types, which mainly corresponded to/originated from epiblast, primitive endoderm (e.g., ExE endoderm and parietal endoderm) or trophectoderm (e.g., ExE ectoderm) (Fig. 4e, f and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Besides, inspection of the expression distribution of several widely accepted marker genes belonging to epiblast (Pou5f1 and Nanog), primitive endoderm (Gata4, Gata6, Foxa2 and Sox17) and trophectoderm (Cdx2 and Eomes) further ensured the fidelity of cell identity we conferred (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Furthermore, two developmental processes, related to the formation of heart and placenta, respectively, were identified. In detail, cardiomyocyte was speculated to originate from epiblast, which was corroborated using potency score calculated via CytoTRACE241 (Fig. 4g). Gene function analysis also revealed compared to epiblast, cardiomyocyte cells were indeed enriched in GO terms related to heart development, such as “regulation of actin filament depolymerization” and “positive regulation of heart rate” (Supplementary Fig. 4c). The other process unveiled by our data was the formation of trophoblast giant cell (TGC) and spongiotrophoblast (SpT), both of which arise from trophoblast progenitor cell (TPC), in line with previous knowledge related to trophoblast differentiation42. Consistently, compared to ExE ectoderm and trophoblast progenitor cell, TGC and SpT were characterized by lower potency score, indicating more differentiated status (Fig. 4h). Pseudo-time analysis performed via monocle243 (Supplementary Fig. 4d) further encouraged our results with TGC and SpT in the more later stages (Fig. 4i).

a A schematic diagram for the collection of IVO- and IVF-conceived mouse embryos and in vitro culture from blastocysts to the egg cylinder stage (96 h of culture). Illustration was created in BioRender. Zhang, C. (https://biorender.com/s2d8f27). b Representative images of IVO- and IVF-conceived embryos following in vitro culture for 48 h in IVC1 and IVC2, respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm. The representative images shown similar results in at least 5 independent repetitions. c Immunofluorescence of OCT4 (green), EOMES (purple) and DAPI (blue) in IVO- and IVF-conceived embryos following in vitro culture. Scale bars, 100 μm. The representative images shown similar results in at least 5 independent repetitions. d Immunofluorescence of OCT4 (green), GATA4 (purple) and DAPI (blue) in IVO- and IVF-conceived embryos following in vitro culture. Scale bars, 100 μm. The representative images shown similar results in at least 5 independent repetitions. e UMAP showing the cell types we identified based on scRNA-seq data. TBD: to be determined. f Heatmap showing the marker genes in each cell type. g, h Potency scores calculated using CytoTRACE2 of cell types related to the formation of cardiomyocyte (g) and placenta (h). The number of cells is 852 (epiblast), 125 (cardiomyocyte), 3039 (ExE ectoderm), 1443 (trophoblast progenitor cell), 1907 (spiral artery trophoblast giant cell) and 72 (spongiotrophoblast). Welch’s unequal variance t-test (both-tail) was performed. The line inside of each box is the sample median and the top and bottom edges of each box are the 0.75 and 0.25 quartiles, respectively. The distance between the top and bottom edges is the interquartile range (IQR). The whiskers are lines that extend above and below each box within 1.5 times the IQR and outliers are values that are more than 1.5 times the IQR away from the top or bottom of the box. i Pseudotime (inferred by monocle2) of four cell types related to placenta development. j UMAP showing the differences of cell type proportions between IVF- and IVO-conceived embryos.

After gaining a basic understanding towards our scRNA-seq data, we next examined how IVF-derived embryos differed from those via IVO at E6.5-E7.5 stage. Intriguingly, we found that the proportions of TPC, TGC and SpT, which are in a more differentiated status compared to ExE ectoderm, were higher in IVF-conceived embryos (Fig. 4j, Supplementary Figs. 4e, f). In contrast, the proportion of epiblast cells was lower in IVF (Fig. 4j, and Supplementary Fig. 4e). Together, these results thus foreboded the imbalanced proportion of both fetus and placenta, and may be associated with the higher placental weights as well as the increased risk of low fetal/birth weight following IVF reported by previous studies44.

CPI-455 treatment improves mouse pregnancy outcome

The dramatic H3K4me3 difference mentioned above let us further try to ameliorate the quality of IVF-conceived embryos from the viewpoint of H3K4me3. To this end, different concentrations of CPI-455, the inhibitor of KDM5, were introduced into the in vitro culture system and maintained during early embryo development (Fig. 5a). As expected, the addition of CPI-455 generally resulted in an increase of H3K4me3 levels, with higher concentrations inducing more pronounced elevation in H3K4me3 levels (5 \({{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{M}}}}\) VS 20 \({{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{M}}}}\)) (Supplementary Figs. 5a, b). Intriguingly, 5 \({{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{M}}}}\) condition indeed facilitated the formation of blastocyst, which, by contrast, was impeded under 20 \({{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{M}}}}\) condition (Fig. 5b, c), hinting only proper increase of H3K4me3 levels is beneficial to the embryo development.

a A schematic representation exhibiting the addition of CPI-455 during mouse embryo development. Illustration was created in BioRender. Zhang, C. (https://biorender.com/b1074ci). b Representative images of blastocysts derived from IVF following the supplementation with different concentrations of CPI-455. Scale bars, 400 μm, 200 μm. 4x and 10x represent the microscopy magnification times. c The blastocyst formation rate under several conditions with different concentrations of CPI-455. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Error bar: mean ± std. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed. d Upper: a schematic diagram showing how SRGs were identified upon CPI-455 treatment; lower: expression heatmap of the SRGs. N = 3 biological replicates for each condition. Illustration was created in PowerPoint. e Relative mRNA expression levels of several SRGs involved in oxidative stress, functions of ATP and mitochondrion. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Error bar: mean ± std. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed. f The distribution of H3K4me3 signals around TSS of several SRGs validated by RT-qPCR (i.e., genes exhibited in Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 5e). g, h Staining and quantification for ROS (g) and GSH (h) in IVF-conceived blastocysts with/without CPI-455 treatment. Scale bars, 60 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Error bar: mean ± std. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed. i A schematic diagram summarizing the crosstalk between H3K4me3 and oxidative stress as well as the potential mechanisms behind it. Illustration was created in BioRender. Zhang, C. (https://biorender.com/8za44jv). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Thus, we next focused on the 5 \({{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{M}}}}\) condition and sought to clarify the possible mechanism behind the above phenomenon. We firstly performed Smart-seq2 experiments on blastocysts derived from IVF, IVO and CPI-455 treatment, and identified (candidate) successfully rescued genes (SRGs) upon CPI-455 treatment, which are up- or down-regulated in both two comparisons including IVF vs IVO and IVF vs CPI-455 treatment (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 5c. Of note, to seek candidate SRGs, we firstly used a less stringent criterion (p < 0.05) to identify the DEGs of two processes and the expression variation of genes with interest was further validated by RT-qPCR.). Using both-up genes as an illustration, these genes were characterized by lower expression levels in IVF-conceived blastocysts, compared to those obtained from IVO. Upon the addition of CPI-455, these genes were up-regulated and thus successfully rescued. Intriguingly, functions of both-up genes included “oxidative phosphorylation”, “ATP metabolic process”, etc (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Accordingly, several both-up genes, related to mitochondrion, ATP and oxidative stress, were extracted, and their transcription variations were then validated by Reverse Transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) (Fig. 5e). Besides, we also noticed the expression level of several genes related to signal transduction regulated by p53 class mediator were also successfully restored upon CPI-455 treatment (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Furthermore, these genes were suggested to be H3K4me3-sensitive as a close association between transcription and H3K4me3 existed: the lower gene expression levels observed in IVF-conceived blastocysts were accompanied by lower H3K4me3 signal within promoter regions, upon CPI-455 treatment, the increase of H3K4me3 level contributed to the activation of these genes (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 5f).

We next sought to clarify whether the levels of oxidative stress as well as mitochondrial functions could be refined after the addition of CPI-455 given that genes related to mitochondrion and oxidative stress have been rescued. We re-evaluated the levels of ROS, GSH, ATP, NAD+ and NADH in both IVF-conceived and those treated with CPI-455, and found that oxidative stress decreased and mitochondrial functions were indeed restored upon CPI-455 treatment (Fig. 5g, h and Supplementary Fig. 5g), which may thus facilitate embryo development (Supplementary Fig. 5h) as well as blastocyst formation in vitro (Fig. 5c). On the other hand, consistent with previous research45, we also found oxidative stress could in turn influence H3K4me3 intensity, as higher H2O2 concentration led to lower H3K4me3 intensity (Supplementary Figs. 5i, j), and the possible mechanism may be that the SET-domain of MLL1, responsible for the lysine-directed histone methylation, was peroxide-sensitive, which has been uncovered previously45. Therefore, we ascribed the lower H3K4me3 signals in IVF-conceived blastocysts to the elevated level of oxidative stress generated due to in vitro operation and exposure. In contrast, the decrease of oxidative stress level, achieved via NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide)-supplementation, resulted in the increase of H3K4me3 intensity (Supplementary Figs. 5k–m).

Taken together, our results emphasized the crosstalk between oxidative stress and H3K4me3 in mouse embryo development (Fig. 5i), and the addition of CPI-455 (i.e., the increase of H3K4me3) could improve embryo quality from various perspectives via restoring specific-gene transcription.

In fact, on the other hand, the abnormal ROS levels in IVF-conceived blastocysts may indicate that anti-oxidant could be effective towards the improvements of the quality of IVF-conceived embryos. In this study, we selected NMN, an effective precursor of NAD+46, for several reasons: Firstly, NMN has already been suggested to possess antioxidant property47. More importantly, previous studies have revealed that female reproductive aging was accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction48 (including the increase of ROS and decrease of ATP, NADH and NAD+) and the reduction of H3K4me349,50, reminiscent of the properties of IVF-conceived blastocysts reported in our work. Of note, a recent review48 emphasized NMN was a potential therapeutic strategy to alleviate aspects of female reproductive aging (i.e., improving pregnancy rate and blastocyst development via restoring NAD+, NADH and mitochondrial activity). Hence, we speculated NMN may also be capable of improving the quality of IVF-conceived embryos. At last, unlike astaxanthin and vitamin E, another two anti-oxidants, the supplementation of NMN could indeed facilitate the formation of blastocyst (Supplementary Fig. 6a). We thus further performed Smart-seq2 and measured ROS/NAD+/ATP levels to clarify the potential mechanisms behind such a phenomenon and compared the effects of NMN to that upon CPI-455 treatment.

Akin to CPI-455, NMN treatment mitigated oxidative stress and promoted ATP/NAD+ formation (Supplementary Fig. 6b). In addition, as expected, NMN seems to be more effective towards the restoration of NAD+ level (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Nevertheless, with respect to oxidative stress, NMN treatment alleviated oxidative stress to a level similar to that upon CPI-455 treatment (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Taken together, these results indicated that NMN supplementation could restore mitochondrial activity, which further contributed to the formation of blastocyst.

On the other hand, based on Smart-seq2 data, we further identified successfully rescued genes (SRGs) upon NMN treatment (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Expectedly, SRGs are associated with “oxidative phosphorylation”, “mitochondrial ATP synthesis coupled electron transport”, “cellular response to reactive oxygen species” (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Surprisingly, we further found many SRGs are conserved between CPI-455 and NMN treatment (Supplementary Fig. 6e), functions of which included “cytoplasmic translation”, “mitochondrial transport”, “protein targeting to mitochondrion”, “mitochondrial transmembrane transport”, “oxidative phosphorylation” and “mitochondrial ATP synthesis coupled proton transport” (Supplementary Fig. 6f). The transcription variation of genes with interest and involved in oxidative stress, mitochondrion and ATP were further validated by RT-qPCR (Fig. 5e).

At last, we performed embryo transfer and examined whether CPI-455 and NMN could improve pregnancy outcome (Supplementary Fig. 6g and Table 1). In fact, CPI-455 and NMN improved the rates of birth and live-birth to similar levels (Supplementary Fig. 6g and Table 1).

In summary, although the effects of CPI-455 and NMN treatment on embryo development are comparable in many ways, including the alleviation of oxidative damage, the restoration of mitochondrial activity and eventually the enhancement of blastocyst formation, birth rate and live-birth rate, the potential mechanisms behind such phenomena were distinctly different with NMN treatment directly providing NAD+, while the addition of CPI-455 firstly rescued the H3K4me3 levels at promoter regions for genes related to mitochondrion, ATP and oxidative stress, and then their expression levels, which further contributed to the restoration of mitochondrial activity.

CPI-455 treatment facilitates human embryo development

The above findings based on mouse embryos suggested that H3K4me3 level seems to be correlated to development rate as well as clinical outcomes given that compared to embryos conceived through IVF, IVO-conceived embryos developed faster (Supplementary Fig. 5h), possessed better clinical outcomes (Table 1) and displayed higher H3K4me3 signals (Fig. 3a). In addition, the supplementation of CPI-455 could improve both developmental rate (Supplementary Fig. 5h) and pregnancy outcome (Table 1).

We next wondered whether such a correlation also exist in human. In fact, due to the inaccessibility of human in vivo pre-implantation embryos, we focused on two kinds of human blastocysts generated via ART: day5- and day6-blastocysts, which refer to the embryos that develop from zygote to blastocyst within 5 and 6 days, respectively, and firstly examined their clinical outcomes (Supplementary Fig. 6h). To minimize the potential confounding effects of baseline characteristic differences on pregnancy outcomes, propensity score matching was performed to achieve a 1:1 match between patients in the day5 and day6 groups (Supplementary table 1). A total of 2,515 matched cycles were successfully identified. After matching, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of age, body mass index (BMI), age group, BMI group, infertility cause, ART protocol or quality of blastocysts (all p > 0.05). However, the day5 group exhibited higher proportions of biochemical pregnancy (64.14% vs 53.12%, clinical pregnancy (55.94% vs 41.75%), and live birth (44.37% vs 31.69%) (all p < 0.001). Conversely, the day5 group had significantly lower abortion rates (20.26% vs 23.62%, p = 0.045) and early abortion rates (16.92% vs 20.57%, p = 0.021). Furthermore, univariate and multivariate logistic regression modeling revealed that day6- blastocyst development (OR: 0.518; 95% CI: 0.454-0.590; p < 0.001) was an independent predictor of live birth rate (Supplementary table 2). Meanwhile, ULI-NChIP-seq data revealed that day5-(4BB) blastocysts harbored higher H3K4me3 signals generally, compared to day6-(4BB) blastocysts (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 7a). Such an observation was further validated using day5- and day6-(4BC) blastocysts (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Furthermore, as expected, day5-blastocysts were characterized by lower ROS level (Supplementary Fig. 7c). These results manifested that akin to mouse, the correlation between H3K4me3 and oxidative stress, and the underlying link of H3K4me3 to clinical outcomes as well as development rate may also exist in human embryos.

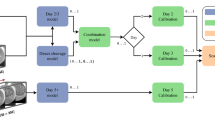

a The distribution of H3K4me3 signals around the TSS of human genes in day5- and day6-blastocysts (n = 3 biological replicates for each condition). b MA-plot showing the differentially H3K4me3-binding regions. c The number of down-regulated genes whose promoter regions were occupied by H3K4me3 lost-peaks. For comparison, we randomly selected genes with the same number as down-regulated genes 100 times and examined whether their promoter regions harbored H3K4me3 lost-peaks. T-test (both-tail) was performed. Error bar: mean ± std. d Functions of genes specifically and highly expression in day6-blastocysts. P-adjust was calculated based on hypergeometric distribution with BH (Benjamini-Hochberg) correction. e The distribution of DNA methylation level around TSS of human genes (left) and global DNA methylation levels (right) in day5- and day6-blastocysts (n = 3 biological replicates for each condition). f A schematic representation displaying the addition of CPI-455 during human embryo development. Illustration was created in BioRender. Zhang, C. (https://biorender.com/ckknt1o). g The rate of blastocysts at day5/6 and high quality embryos at day 3 or day5/6 during human embryo development with/without CPI-455 treatment. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. h Functions of human CPI-455 sensitive genes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Consistent with Fig. 6a, further differential analysis on H3K4me3 ULI-NChIP-seq data revealed almost all differentially regions were lost-regions (10 VS 11404, Fig. 6b), indicating the global reduction of H3K4me3 in day6-blastocysts. Such a variation was associated with gene transcription variation since we found the promoter regions of down-regulated genes tend to be enriched in H3K4me3 lost peaks (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Figs. 7d–f). Notably, functions of genes specifically and highly expressed in day6-blastocysts included “DNA damage response, detection of DNA damage”, “intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway by p53 class mediator” and “mitotic G1 DNA damage checkpoint signaling” (Fig. 6d), which may indicate DNA sequence in day6-blastocysts underwent more severe damage, accordant with preceding results revealing poorer clinical outcomes for day6-blastocysts. In contrast, genes highly expressed in day5-blastocysts were related to mitochondrial function, the metabolic processes of compound and ischemia (Supplementary Fig. 7g). Intriguingly, ischemia has been suggested to be closely linked to oxidative stress51 and therefore gene functions we observed here (e.g., ischemia and metabolic processes) partially resembled those obtained based on DEGs between IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocysts in mouse (Fig. 2c).

On the other hand, we also compared the DNA methylation levels of day5- and day6-blastocysts, which seemed to be irregular (Fig. 6e). However, compared to previous studies52, the sample size in our work was limited, more data taking into account both epigenetic information and clinical outcomes from the same embryo are needed to better compare the correlation of clinical outcomes to H3K4me3/DNA methylation. We next applied CPI-455 treatment, which has been suggested to facilitate mouse embryo development, to human embryos (Fig. 6f). Intriguingly, the addition of CPI-455 was indeed beneficial for the formation of high quality human embryos at both day 3 and day 5/6 (Fig. 6g and Supplementary Figs. 7h, i). In order to clarify the possible mechanism behind it, we further performed Smart-seq2 on CPI-455-treated blastocysts and identified CPI-455-sensitive genes, i.e., genes up- or down-regulated in both CPI-455-treated day5- and day6-blastocysts, compared to day5- and day6-blastocysts without treatment, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7j). These genes are related to cytoplasmic translation, mRNA catabolic process, ATP, mitochondrion and signal transduction regulated by p53 class mediator (Fig. 6h), reminiscent of the functions of SRGs upon CPI-455 addition in mouse embryo (Supplementary Fig. 5d), hinting the conservation of the effects of CPI-455 treatment between human and mouse. Taken together, we speculated that similar to mouse, the restoration of genes related to ATP, mitochondrion, etc., contributed to the improvement of human embryo developmental competence, emphasizing the potential role of CPI-455 in clinical application.

Discussion

Recently, the adverse outcomes following ART have caught people’s attention and accordingly, many studies indeed revealed the discrepancies of epigenetic markers between samples conceived via ART and spontaneously13, which may further lead to the dysregulation of specific genes. Although these researches proposed the potential mechanisms linking adverse outcomes to the disruption of epigenetic modifications, samples they used were at very late stages, such as placenta and cord blood. In fact, clarifying their differences at much earlier stages (pre-implantation) may guide us to ameliorate the quality of embryos conceived via ART and reduce the rate of adverse outcomes. Therefore, in this study, by means of multi-omics data, we firstly delineated in mouse how and to what extent IVF-conceived embryos differed from those generated via IVO at early developmental stages, especially at blastocyst stage. Moderate transcriptional differences were observed from PN5 to morula, except late 2-cell. Of note, we also noticed for IVF-conceived embryos, Carm1, heterogeneously expressed in different blastomeres with higher and lower Carm1 expression contributing to the formation of ICM and TE27,28, respectively, failed to activate during ZGA process. As mentioned above, such a phenomenon may lead to the dysregulation of both ICM and TE marker genes in IVF-conceived blastocysts. Furthermore, this activation failure may also be related to the aberrant and imbalanced cell type compositions (i.e., lower and higher proportions for epiblast and trophoblast-related cells, respectively in IVF-conceived embryos) revealed by our post-implantation scRNA-seq data. In fact, aside from post-implantation stage (~E6.5), at pre-implantation blastocyst stage, we have already observed IVF-conceived blastocysts harbored higher and lower proportion of TE and ICM cells, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8a), which was indeed consistent with our observation at ~E6.5 stage (Supplementary Figs. 4e, f). At E18.5 stage, we collected both mouse placenta and fetus. Intriguingly, in contrast to IVO, IVF was characterized by higher and lower percentage of placenta weight (defined as placental weight divided by the total weight of both placenta and fetus) and efficiency of placenta (defined as the ratio between the weights of fetus and placenta), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8b), in accordance with the cell proportion differences between IVF- and IVO-conceived embryos at both pre-implantation blastocyst and ~E6.5 stages. Taken together, these results were indeed consistent with the abnormal weights of both fetus and placenta reported by previous studies44 and emphasized that strategies towards the restoration of Carm1 expression level may be attempted in future studies.

On the other hand, at epigenetic level, we observed huge H3K4me3 differences between IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocyst. In fact, one previous research53 has also shown that IVO-conceived blastocysts possessed higher H3K4me3 signals using immunofluorescence staining, and such a difference could trace back to as early as zygote stage and maintained during embryo development. Besides, we noticed that one study26 also performed H3K4me3 ULI-NChIP-seq experiments on NM (natural mating) and IVF (in vitro fertilization and in vitro culture), similar to our design. Therefore, we downloaded the raw data and reanalyzed it. We firstly projected H3K4me3 peaks identified in our study to their data to further ensure the fidelity of H3K4me3 peaks (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Then we calculated the H3K4me3 signals within these peaks and found that compared to IVF, NM samples indeed harbored significantly higher H3K4me3 signals, consistent with our observations (Supplementary Fig. 8d). Conclusions derived from previously published H3K4me3 data between IVO54- and IVC10 (in vivo fertilization and in vitro culture)-conceived blastocysts (Supplementary Fig. 8e) also support our discoveries. Furthermore, we also wondered why our data exhibited more striking H3K4me3 differences. We speculated that longer in vitro culture time may lead to more severe oxidative stress and thus lower H3K4me3 signal given that the negative correlation between H3K4me3 intensity and H2O2 concentration has been observed (Supplementary Fig. 5j): The timepoint of NM and IVF data reported in Bai et al. was E3.526, however, in our work, as mentioned above, to better link our study to clinical practice, in which blastocyst at stage four was practically transferred to the uterus, we specifically selected this kind of blastocyst (timepoint: ~E4.5 for IVF-conceived stage four blastocyst) for further investigation. Therefore, it is possible that IVF-conceived embryos in our work suffered more oxidative stress due to the longer in vitro culture time, resulting in more significant H3K4me3 differences. To test this hypothesis, we measured the H3K4me3 intensities and ROS level of IVF-conceived E4.5 and E5.5 (mouse) blastocysts with the latter indeed bearing significantly lower H3K4me3 signals and higher ROS levels (Supplementary Figs. 8f, g). Results derived from human embryos further corroborated our hypothesis as human day6-blastocysts were characterized by lower H3K4me3 and higher ROS levels, relative to day5-blastocysts (Supplementary Figs. 7a–c). Taken together, both our and previously published data revealed in vitro culture procedure could influence H3K4me3 signals. Furthermore, our data uncovered a correlation among in vitro culture time, oxidative stress and H3K4me3 intensity.

Based on large-sample clinical data analysis, our results demonstrated that the duration of embryonic development exerts a significant influence on the outcomes of ART, corroborating findings from previous investigations55,56. The clinical pregnancy rate and live birth rate in the day5-blastocyst group were 60.47% and 50.20%, respectively, which were markedly higher than those in the day6-blastocyst group (39.89% and 29.82%, p < 0.001). Following adjustment for potential confounding variables using PSM (propensity score matching), the observed differences remained statistically significant, thereby confirming that developmental duration is an independent prognostic factor for ART outcomes.

Intriguingly, in our work, we found mouse IVF-conceived blastocysts resembled human day6-blastocysts in many ways. Both of them suffered more oxidative stress and possessed lower H3K4me3 signals. On the other hand, in contrast to mouse IVO- and human day5-blastocysts, mouse IVF- and human day6-blastocysts developed a bit slower with poor clinical outcomes. In fact, the potential mechanisms behind the above phenomena between human and mouse were also similar: relative to mouse IVO- and human day-5 blastocysts, mouse IVF- and human day6-blastocysts underwent longer in vitro culture time and thus accumulated more oxidative stress, which consequently influenced their H3K4me3 signal given that based on previous work45, higher oxidative stress could disturb the activity of enzyme responsible for lysine-directed histone methylation. Intriguingly, the correlation between H3K4me3 and clinical outcomes exist in both mouse and human given that the supplementation of CPI-455 could facilitate blastocyst formation and improve clinical outcomes, further investigation revealed the mechanism related to such improvements upon CPI-455 treatment may also be conserved between human and mouse. Nevertheless, we measured H3K4me3 levels among day5-blastocysts with different morphological grades including 4AA, 4BB and 4BC but no significant difference was observed among them (Supplementary Fig. 8h), which may be due to the similar in vitro culture time. Therefore, the similar H3K4me3 levels among day5-blastocysts with different morphological grades may indicate other factors (such as DNA methylation52) other than H3K4me3 could also be related to clinical outcomes.

Regarding DNA methylation, the proper expression of imprinted genes, such as H19, relies on accurate epigenetic landscape, such as DNA methylation, and is essential for normal embryo development. One previous work57 found that in vitro culture could perturb the methylation level, resulting in the loss of H19 imprinting. Another related work58 performed WGBS experiments on IVF- and IVO-embryos and identified 1624 DMRs. Intriguingly, regions undergoing DNA methylation changes were generally distal from TSS (transcription start sites), indicating enhancer activity may change. Furthermore, given that CTCF has been suggested to play pivotal roles in establishing enhancer-promoter interactions59 through loop-extrusion mechanism60,61 and its binding was methylation-sensitive62, therefore, in future, studies carefully checking the variation of enhancer activity, CTCF binding and 3D chromatin structure in IVF-conceived embryos, and their implications for gene transcription, are needed.

In summary, our work firstly elucidated the differences between IVF- and IVO-conceived embryos at early developmental stages. In addition, the non-negligible crosstalk between H3K4me3 and oxidative stress was uncovered. At last, we found the addition of CPI-455, an inhibitor of KDM5, could facilitate embryo development of both mouse and human, and the potential mechanisms may also be conserved.

Methods

Fertilization, culture and collection of mouse embryos

Superovulation was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 10 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) (110914564, Ningbo Second Hormone Factory) followed by 10 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (110911282, Ningbo Sansheng Biological Technology Co., LTD) 48 h later. In this study, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The only procedures performed on deceased animals were the collection of oocytes from the oviducts, sperm from the caudal epididymides and vas deferens, or embryos from the uteri.

To collect in vivo developed (IVO) blastocysts, female mice were mated with male mice overnight, and the presence of vaginal plugs was checked the following morning. The morning after detecting vaginal plugs was designated as E0.5. Embryos at different stages were collected from their uteri at different time points after hCG injection: PN5 zygote (27 h post-hCG), early 2-cell (39 h post-hCG), late 2-cell (48 h post-hCG), 4-cell (56 h post-hCG), 8-cell (65 h post-hCG), morula (77 h post-hCG), and blastocyst (93 h post-hCG).

In mouse zygotes, post-fertilization development can be categorized into distinct pronuclear (PN) stages, specifically PN1 to PN563,64. A PN5 zygote represents the terminal pronuclear stage of mouse embryonic development, occurring ~16–18 h after fertilization. At this pre-mitotic G2 phase, the zygote exhibits enlarged pronuclei that are closely aligned near the embryonic center, following the completion of DNA replication. This developmental stage directly precedes pronuclear membrane breakdown and the initiation of the first mitotic division.

According to the Gardner and Schoolcraft scoring systems, blastocysts are given a numerical score from 1 to 6 based upon their degree of expansion and hatching status. A stage 4 blastocyst, also known as an expanded blastocyst, is characterized by a blastocoel volume that exceeds that of an early blastocyst (corresponding to stage 1), accompanied by thinning of the zona pellucida. This stage indicates progressive embryonic development prior to potential hatching.

To obtain blastocysts derived from in vitro fertilization (IVF) and culture, IVF procedures were performed. Briefly, the superovulated mice were sacrificed 13–14 h after hCG injection and the oviductal ampullae were broken to release cumulus-oocyte complexes. Sperms from the caudal epididymides and vas deferens were collected from 13-week old male mice, and capacitated in G-IVF PLUS medium (10136, Vitrolife) for 30–45 min at 37 °C, 6% CO2 and 5% O2. Subsequently, capacitated spermatozoa were added at a final concentration of 0.25 × 106 cells/ mL to the cumulus-oocyte complexes in G-IVF PLUS medium under mineral oil (Vitrolife, 10029) for 6 h in a 37 °C cell incubator containing 6% CO2. Fertilized oocytes characterized by two pronuclei were further cultivated in G1 PLUS medium (10128, Vitrolife) under mineral oil at 37 °C, 6% CO2 and 5% O2. Embryos at the following developmental stages were collected: PN5 zygote (29 h post-hCG), early 2-cell (41 h post-hCG), late 2-cell (53 h post-hCG), 4-cell (65 h post-hCG), 8-cell (74 h post-hCG), morula (93 h post-hCG), and blastocyst (113 h post-hCG).

To investigate the influence of H3K4me3 on embryo development, zygotes derived from IVF were cultured in G-1 PLUS medium supplemented with the demethylase inhibitor CPI-455 (HY-100421, MedChemExpress) at concentrations of 0 μM, 1 μM, 5 μM, 10 μM, and 20 μM for 96 h. Blastocysts from the control group and the 5 μM CPI-455 group were subsequently collected for further analysis.

Extended mouse embryo culture

The zona pellucida of IVF- and IVO-conceived blastocysts was eliminated by using Tyrode’s Solution, Acidic (RNBG8296, Sigma). Subsequently, the bottom of each well of a μ-slide 8 well (80827, ibidi) was uniformly covered with 50 μL of Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Extract (RGF BME), Type 2 (3533-005-02, R&D Systems), and the dishes were placed in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 30 min. After the RGF BME solidified, 200 μL of balanced IVC1 medium was added to each well of the eight-well slides, and 5-6 zona pellucida free blastocysts were introduced into the IVC1 medium. Then, the embryos were cultivated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 48 h. Once the embryos were stably adhered to the bottom of the wells, the IVC1 medium was substituted with 200 μL of balanced IVC2 medium. The slides were further incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for another 48 h.

The ingredients of IVC1 and IVC2 media were presented in Supplementary tables 4 and 5, respectively.

Human gametes and early embryo collection

Human immature oocytes were donated by 20–38-year-old women with tubal-factor infertility or as the female partners of infertile couples due to male factors, which were clinically discarded during IVF/ICSI treatments and donated by patients after obtaining informed consent. Controlled ovarian stimulation was carried out and transvaginal ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval was scheduled 36 h after hCG administration. Immature oocytes were cultured in an in vitro maturation (IVM) medium at 37 °C under an atmosphere of 6% CO2 for 18–24 h. The IVM medium comprised M199 medium (GIBCO, 11-150-059), supplemented with 20% Systemic Serum Substitute (Irvine Scientific, 99193) and 75 mIU/mL recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (Merck Serono). These in vitro matured oocytes were fertilized using sperm samples donated exclusively for research purposes and subsequently cultured in G-1 PLUS medium (Vitrolife), either with or without 5 μM CPI-455, under a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 6% CO2 and 5% O2. The day of prokaryotic nuclei emergence was designated as Day 1, and embryo development was evaluated on Days 3 and 5/6, respectively.

The day 5 and day 6 human blastocysts were from donated cryopreserved embryos. Vitrification of the blastocysts was performed as described65. Briefly, the blastocysts were incubated in Vitrification Solution 1 consisting of 8% ethylene glycol and 8% dimethyl sulfoxide in Cryobase (10 mM HEPES-buffered medium containing 20 mg/mL human serum albumin and 0.01 mg/mL gentamicin) at room temperature (RT) for 8 min. Following initial shrinkage, blastocysts with original volume were transferred into Vitrification Solution 2 (16% ethylene glycol, 16% dimethyl sulfoxide, and 0.68 M trehalose in Cryobase) for 1–1.5 min. Finally, blastocysts were loaded onto the Cryotop strip in a small volume of solution (< 0.1 mL) and plunged into liquid nitrogen. After the addition of the protective cover, the Cryotop was stored in liquid nitrogen.

The vitrified blastocysts on the Cryotop strip were rapidly thawed by removing the protective cover and transferring them directly from liquid nitrogen into 2.5 mL of Warming Solution 1 (1 M trehalose in Cryobase) pre-warmed to 37 °C, where they were incubated for 1 min. The blastocysts were subsequently transferred to 0.5 mL of Warming Solution 2 (0.5 M trehalose in Cryobase), also pre-warmed to 37 °C, for 3 min. They were then placed into 0.5 mL of Cryobase for 5 min, followed by a final rinse in fresh 0.5 mL of Cryobase for 1 min. Finally, the blastocysts were transferred to G-1 PLUS or G-2 PLUS medium (Vitrolife) for assessment of embryo quality.

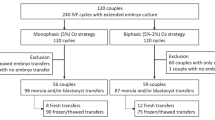

Clinical Study design and statistical analysis

This was a retrospective cohort study based on data collected from the Reproductive Hospital of Shandong University. We investigated the embryo development and pregnancy outcomes of women undergoing autologous Day-5 and Day-6 single vitrified blastocyst transfers following IVF/ICSI from January 2020 to December 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients who underwent their first single embryo thawed transfer at our reproductive center; 2) patients aged between 20 and 45 years. The exclusion criteria included: 1) cervical insufficiency; 2) uterine myomas or malformations; 3) intrauterine adhesion; 4) significant missing data. A total of 16,974 first single frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer cycles were initially identified. Of these, 2,768 cycles were excluded for the following reasons: cervical insufficiency (n = 81), uterine myomas (n = 1423), uterine malformations (n = 286), intrauterine adhesion (n = 965), and significant missing data (n = 13). After screening, 14,206 eligible cycles were included in the final analysis. The blastocyst scoring adopted the Gardner and Schoolcraft scoring systems and those with score ≥4BB were determined as high-quality blastocysts.

Analysis of clinical data was conducted using SPSS 25 statistical software. Quantitative data that met the assumptions of normal distribution and homogeneity of variance were analyzed using independent samples t-tests, with results presented as mean ± standard deviation. Qualitative data were compared using chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Propensity scores were calculated via logistic regression based on patient characteristics and frozen-thawed embryo transfer (FET) variables, including female age, body mass index (BMI), infertility cause, assisted reproductive technology (ART) protocol and quality of blastocysts. Matching without replacement was performed using propensity scores through the nearest neighbor matching algorithm with a 1:1 ratio. A total of 2,515 cycles were matched in pairs. Factors showing statistically significant differences in univariate logistic regression analyses were subsequently included in the multivariate logistic regression model. *P < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Immunofluorescence

Briefly, embryos were fixed for 30 minutes using 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (KGB5001, KeyGEN BioTECH) at RT and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton-X 100 (T8787, Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 20 minutes. Subsequently, the embryos were blocked with the blocking buffer (PBS containing 1% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20 (P9416, Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.01% Triton-X 100) at RT for 30 minutes. Then, the embryos were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in the blocking buffer for an hour. After being rinsed three times for 5 minutes in the washing buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 0.01% Triton-100) on shakers at RT, the embryos were incubated with a secondary antibody on shakers at RT for 30 min in the dark. Nuclei were co-stained with DAPI (1:500 dilution, D3571, Life Technologies). After being rinsed three times, the embryos were placed on slides in the washing buffer and imaged under a laser scanning confocal microscope (Dragonfly, Andor Technology, UK). Immunofluorescence images were analyzed by Image J Software.

The antibodies were presented in Supplementary table 6.

Determination of ROS and GSH

To determine intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in embryos, carboxy-H2DFFDA (C13293, Invitrogen) was used to measure endogenous H2O2 levels. IVF and IVO blastocysts were incubated in M2 medium supplemented with 10 μM carboxy-H2DFFDA at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing at least five times in M2 medium, the embryos were imaged using a confocal microscope (Dragonfly, Andor Technology, UK) with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and identical imaging parameters. Image J (National Institutes of Health, USA) was used to quantify the fluorescence intensity of each embryo. To assess glutathione (GSH) levels, the collected embryos were incubated in M2 medium supplemented with 10 μM Thiol Tracker Violet (T10095, Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by the same washing and imaging procedures as described for ROS measurement.

Determination of NAD+ and NADH

The levels of NAD+ and NADH in embryos were determined using the NAD/NADH-Glo™ Assay Kit (G9071; Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Embryos were lysed with 150 μL of 0.2 M NaOH and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The lysate was then divided into two aliquots (50 μL each). For NAD+ measurement, 25 μL of 0.4 N HCl was added to one aliquot, followed by heating at 60 °C for 15 min. After cooling to room temperature for 10 min, 25 μL of 0.5 M Trizma base was added. For NADH measurement, the second aliquot was heated at 60 °C for 15 min and cooled to room temperature for 10 min, after which 25 μL of 0.5 M Trizma base and 25 μL of 0.4 N HCl were added sequentially. The detection reagent was then added to both samples, and they were incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature. Luminescence was measured using an EnSpire multimode plate reader (PerkinElmer) after shaking for 5 seconds.

Measurement of ATP

The ATP levels in embryos were determined using the Luminescent ATP Detection Assay Kit (ab113849, Abcam). After shaking for 5 seconds with the EnSpire multimode plate reader, the ATP content was calculated based on a formula derived from the 4-parameter logistic (4PL) regression analysis of a standard curve containing six ATP concentrations ranging from 12.5 pmol to 10 nmol. Each experiment utilized at least 40 blastocysts.

H2O2 treatment

IVO-blastocysts were collected as described above. Embryos were incubated in G-1 PLUS medium supplemented with 0 μM, 200 μM, 400 μM, or 1000 μM H2O2 under dark conditions at 37 °C with 6% CO2 and 5% O2 for 3 h. After washing at least five times in M2 medium, the embryos were imaged using a confocal microscope to measure their H3K4me3 levels.

Smart-seq2 experiment

According to previous methods66, five embryos of each stage were used to construct each library. The zona pellucida free embryos were transferred to lysis buffer by mouth pipetting. The library was generated by TruePrep DNA Library Prep Kit V2 for Illumina (Vazyme, TD502) and TruePrep Index Kit V3 for Illumina (Vazyme, TD203). Libraries that passed quality control were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus platform.

RT-qPCR

To validate the sequencing results, reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was conducted. The zona pellucida was removed using acidic Tyrode’s solution. Embryos were lysed in 200 μL RNase-free PCR tubes containing 2 μL cell lysis buffer (5% RNaseOUT (Invitrogen, 10777019) in 0.2% Triton X-100), 1 μL oligo-dT primer and 1 μL dNTP mix (Invitrogen, AB0196) (both 10 μM). After vortexing and centrifugation, hybridization was performed at 72 °C for 3 min. The reaction mixture was chilled on ice, followed by addition of reverse transcription components: 0.5 μL SuperScript IV (200 U/μL; Invitrogen,18090200), 0.25 μL RNaseOUT (40 U), 2 μL 5× SSIV Buffer, 2 μL Betaine (Sigma-Aldrich, 61962), 0.06 μL MgCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, M8266), and 0.19 μL nuclease-free water. After mixing and centrifugation, reverse transcription was conducted at 50 °C for 90 min with subsequent enzyme inactivation at 70 °C for 15 min. The cDNA product was diluted fivefold with nuclease-free water for qPCR template.Target mRNA expression levels were quantified using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q711, Vazyme) on Thermo Fisher Scientific QuantStudio 7 Pro Real-Time PCR System. Relative mRNA levels were calculated after normalization to the internal reference gene Gapdh, using \({2}^{-\Delta \Delta {Ct}}\). The primer sequences were provided in Supplementary table 7.

ULI-NChIP-seq

After removal of the zona pellucida by 0.8% acidic GMOPS, 10 blastocysts were used as a replicate. ~1 μg of histone H3K4me3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 9751 T) or histone H3K27me3 antibody (Active motif, 39155) was used for the immunoprecipitation reaction. The ULI-NChIP-seq libraries were constructed using the NEBNext® UltraTM II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, E7645L) and Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB, M0491S). Libraries that passed quality control were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus platform.

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS)

After eliminating the zona pellucida, bisulfite conversion was performed according to the protocol provided in the EZ-96 DNA Methylation-Direct MagPrep kit (Invitrogen, D5045). The converted DNA was purified using Zymo-Spin columns with 10 ng of tRNA (Roche) added during the purification process. Whole-genome libraries were then constructed. Libraries that passed quality control were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus platform.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)

IVO- and IVF- blastocysts were collected for extended mouse embryo culture as described above. After cultured in IVC1 for 48 h and then cultured in IVC2 for 48 h (the ingredients of IVC1 and IVC2 mediums were shown in Supplementary tables S4 and S5, respectively), 45 embryos were collected in each group and digested by TrypLETM Express Enzyme (1×), no phenol red (Thermo Fisher, 12604013) at 37 °C for 10 min. The scRNA-seq libraries were constructed following the protocol provided in the Singleron GEXSCOPE single-cell sequencing kit (Singleron Biotechnologies). Each library was individually diluted to a concentration of 4 nM and then pooled for combined sequencing on the Illumina novaseq 6000.

Smart-seq2 data processing

Reads were firstly mapped to mouse (mm10) or human (hg38) genome using STAR67 (v2.5.3a) and then the quantification results, including raw counts, TPM and FPKM were obtained via RSEM68 (v1.3.3). For mouse (human), genes with \(\left|{\log }_{2}({fold}-{change})\right|\) > 1 and p-adjust < 0.05 (\(\left|{\log }_{2}({fold}-{change})\right|\) > 0 and p-adjust < 0.1) were identified as DEGs (differentially expressed genes) based on DESeq269 (v1.32.0). Gene function analysis was performed by means of clusterProfiler70 (v4.2.2). Homer (http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/motif/) was used for sequence motif enrichment analysis.

ULI-NChIP-seq data processing

For comparison, raw reads were firstly down-sampled to the same sequencing depth (see Supplementary table 8) and then trimmed using trim_galore (v0.6.7) (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore) with “-q 25 --length 35 -e 0.1 --stringency 4”. The clean reads were aligned to mouse genome (mm10) or human genome (hg38) using bowtie271 (v2.2.5), yielding raw bam files, which were then deduplicated using sambamba72 (v0.6.6). At last, bigwig files with CPM normalization were generated using bamCoverage in deepTools73 (v3.5.1) for downstream analysis. Peaks of H3K4me3 or H3K27me3 were firstly identified individually using macs274 (v2.2.7.1) and then merged together for differentially analysis conducted in DiffBind (v3.2) (https://github.com/nshanian/DiffBind). Figures exhibiting the distribution of histone signals around specific regions (such as peak center and TSS) were generated using computeMatrix and plotHeatmap in deepTools73 (v3.5.1). We applied chromHMM34 (binsize = 500 bp), using H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 ChIP-seq data as input, to divide whole genome into 4 states: none (decorated by neither H3K4me3 nor H3K27me3), active (decorated by only H3K4me3), repressive (decorate by only H3K27me3) and bivalent regions (decorated by both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3).

WGBS data processing

WGBS data were analyzed following Bismark75 (v0.23.1) instructions. Briefly, raw reads were firstly trimmed using trim_galore (v0.6.7) (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore) with “-q 25 --length 35 -e 0.1 --stringency 4” and then mapped to modified mouse (mm10) or human (hg38) genome generated using bismark_genome_preparation. After deduplication, MethylDackel (v0.5.1) (https://github.com/dpryan79/MethylDackel) with default parameters was used to extract DNA methylation information. For the identification of differentially methylated regions (DMR), replicates were firstly merged together and DSS (v2.40.0) (https://github.com/haowulab/DSS) with “delta = 0.1 and p.threshold = 0.001” was further applied. Figures showing the distribution of DNA methylation level around TSS and TES were generated using computeMatrix and plotHeatmap in deepTools73 (v3.5.1).

scRNA-seq data processing

Raw reads were processed to generate gene expression profiles using CeleScope (v1.15.0, Singleron Biotechnologies) (https://github.com/singleron-RD/CeleScope) with default parameters. Briefly, Barcodes and UMIs were extracted from R1 reads and corrected. Adapter sequences and poly A tails were trimmed from R2 reads and the trimmed R2 reads were aligned against the mouse (mm10) transcriptome using STAR67 (v2.6.1b). Uniquely mapped reads were then assigned to genes with FeatureCounts76 (v2.0.1). Successfully Assigned Reads with the same cell barcode, UMI and gene were grouped together to generate the gene expression matrix.

Further analysis based on gene expression matrix was conducted in Seurat77 (v4.3.0). For each dataset, expression data were filtered using the following criteria: 1) genes expressed in less than 3 cells were excluded; 2) cells with gene features <50 were excluded; 3) cells with mitochondrial content > 5% were excluded. After filtering, 4357 and 5415 cells, for IVF- and IVO-conceived embryos, respectively, were used for down-stream analysis. After Log-Normalization and scaling, PCA was performed on the scaled data with 2000 highly variable features being used as input. Harmony78 (v1.2.0) in this study was then applied for data integration and cell clustering was performed using first 40 dimensions with resolution = 1.1. Marker genes were identified and displayed using “FindAllMarkers” in Seurat77 (v4.3.0) and scRNAtoolVis (v0.1.0) (https://github.com/junjunlab/scRNAtoolVis), respectively. SeuratExtend79 (v1.1.2) was used for gene function analysis, and developmental trajectories was inferred by means of CytoTRACE241 (v1.0.0) and monocle243 (v2.21.1).

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. During experiments and outcome assessment, all samples were randomized and blinded. Statistical analyses of immunofluorescence, RT-qPCR, rate of blastocyst formation, and levels of NAD+, NADH and ATP were performed using two tailed unpaired t tests or ordinary one-way and ANOVA by means of GraphPad Prism 10. We also used GraphPad Prism 10 to perform statistical analyses of birth rate and live birth rate based on fisher’s exact test. Each experiment was conducted with at least three biological replicates. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Ethics statement for animal studies

Female mice (6–8-week-old) and male mice (8-week-old) of the Institute for Cancer Research (ICR) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. and reared under specific pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle. All experimental protocols involving mice were approved by the Ethic Committee of Reproductive Medicine of Reproductive Hospital of Shandong University (2022-138). The maintenance and use of mice were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Ethics statement for human studies

All the experiments carried out in human gametes and embryos were approved by the Ethic Committee of Reproductive Medicine of Reproductive Hospital of Shandong University (2022-138), in accordance with Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Human Assisted Reproductive Technology, the ethical guidelines for Human Assisted Reproductive Technology and Human Sperm Banks, and the Declaration of Helsinki. Detailed information of human embryos we used in this work is summarized in Supplementary table 3. All human gametes and embryos used in this study were obtained from the Hospital for Reproductive Medicine Affiliated to Shandong University with signed Informed consent. The participants were informed of the study’s purpose in advance and voluntarily donated gametes and embryos without compensation.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Mouse data generated in this study and related to the comparisons of IVF- and IVO-conceived embryos, including Smart-seq2, H3K27me3 and DNA methylation, have been deposited to the Genome Sequencing Archive (GSA) under the accession number CRA024660. Mouse data generated in this study and related to CPI-455 treatment, including Smart-seq2 and H3K4me3, have been deposited to the GSA under the accession number CRA024689. Human data generated in this study, including Smart-seq2 with/without CPI-455 treatment, H3K4me3 and DNA methylation, can be accessed from GSA-human under the series number HRA011033. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Berntsen, S. et al. IVF versus ICSI in patients without severe male factor infertility: a randomized clinical trial. Nat. Med. 31, 1939–1948 (2025).

Nardelli, A. A., Stafinski, T., Motan, T., Klein, K. & Menon, D. Assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs): Evaluation of evidence to support public policy development. Reprod. Health 11, 76 (2014).

Schieve Laura, A. et al. Low and very low birth weight in infants conceived with use of assisted reproductive technology. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 731–737 (2002).

von Wolff, M. & Haaf, T. In vitro fertilization technology and child health. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 117, 23–30 (2020).

Jauniaux, E., Moffett, A. & Burton, G. J. Placental implantation disorders. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 47, 117–132 (2020).

Chen, M. et al. Altered glucose metabolism in mouse and humans conceived by IVF. Diabetes 63, 3189–3198 (2014).

Brison, D. R. IVF children and healthy aging. Nat. Med. 28, 2476–2477 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Leukocyte telomere length in children born following blastocyst-stage embryo transfer. Nat. Med. 28, 2646–2653 (2022).

Smith, Z. D. et al. DNA methylation dynamics of the human preimplantation embryo. Nature 511, 611–615 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Distinct features of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 chromatin domains in pre-implantation embryos. Nature 537, 558–562 (2016).

Wilkinson, A. L., Zorzan, I. & Rugg-Gunn, P. J. Epigenetic regulation of early human embryo development. Cell Stem Cell 30, 1569–1584 (2023).

Wu, K. et al. Dynamics of histone acetylation during human early embryogenesis. Cell Discov. 9, 29 (2023).

Mani, S., Ghosh, J., Coutifaris, C., Sapienza, C. & Mainigi, M. Epigenetic changes and assisted reproductive technologies. Epigenetics 15, 12–25 (2020).

Tobi, E. W. et al. DNA methylation differences at birth after conception through ART. Hum. Reprod. 36, 248–259 (2021).

Chi, F. et al. DNA methylation status of imprinted H19 and KvDMR1 genes in human placentas after conception using assisted reproductive technology. Ann. Transl. Med. 8, 854 (2020).

Cannarella, R. et al. DNA methylation in offspring conceived after assisted reproductive techniques: a systematic review and meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 11, 5056 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Comparison of histone H3K4me3 between IVF and ICSI technologies and between boy and girl Offspring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8574 (2021).

Choux, C. et al. The hypomethylation of imprinted genes in IVF/ICSI placenta samples is associated with concomitant changes in histone modifications. Epigenetics 15, 1386–1395 (2020).

Håberg, S. E. et al. DNA methylation in newborns conceived by assisted reproductive technology. Nat. Commun. 13, 2022 (1896).

Ghosh, J., Coutifaris, C., Sapienza, C. & Mainigi, M. Global DNA methylation levels are altered by modifiable clinical manipulations in assisted reproductive technologies. Clin. Epigenetics 9, 14 (2017).

Auvinen, P. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation and gene expression in human placentas derived from assisted reproductive technology. Commun. Med. 4, 267 (2024).

Song, S. et al. DNA methylation differences between in vitro- and in vivo-conceived children are associated with ART procedures rather than infertility. Clin. Epigenetics 7, 41 (2015).

Xu, N. et al. Comparison of genome-wide and gene-specific DNA methylation profiling in first-trimester chorionic villi from pregnancies conceived with infertility treatments. Reprod. Sci. 24, 996–1004 (2017).

Zechner, U. et al. Quantitative methylation analysis of developmentally important genes in human pregnancy losses after ART and spontaneous conception. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 16, 704–713 (2010).