Abstract

The CELSR1 gene is a core component of the tissue/planar cell polarity signaling pathway. It encodes a developmentally regulated protein that belongs to the adhesion G protein-coupled receptors. Herein we describe seven subjects, from five unrelated families, featuring a neurodevelopmental disorder associated with biallelic CELSR1 variants. The main phenotypic features of this disorder are different types of brain malformations (including pachygyria, periventricular nodular heterotopia, abnormal corpus callosum, white matter abnormalities, hypoplasia of brainstem and cerebellum), variable degrees of neurodevelopmental delay and intellectual disability, behavioral disorders, and, in some subjects, epilepsy. Using whole exome sequencing, we identify five compound heterozygous variants and one homozygous variant of CELSR1 in these subjects. We infer the pathogenicity and functional effects of these variants through bioinformatic analysis, protein modelling and prediction tools. To further characterize the effects of mutant CELSR1, we generate Celsr1 knockout mice, which exhibit partial agenesis of the corpus callosum, periventricular heterotopia and irregular shape of the ventricular/subventricular zone, enlarged lateral ventricles with a fully penetrant phenotype, and increased susceptibility to seizures. These findings emphasize the importance of CELSR1 in several polarity-dependent processes during embryonic and postnatal development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In humans, the central nervous system (CNS) starts to develop early in embryonic life, and its development continues for years after birth. Neurodevelopmental delay (NDD) is a group of heterogeneous childhood conditions with high clinical heterogeneity and affects ~1–3% of children worldwide1. Features of NDD are impairment in cognition, language, behavior, and/or motor skills (such as impaired gross motor abilities and fine-motor coordination), resulting from abnormal brain development. Intellectual disability (ID), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are common comorbidities associated with NDD2. ID is defined as a disorder with onset during the developmental period that includes both intellectual and adaptive functioning deficits in conceptual, social, and practical domains3. It affects approximately one to four per cent of the population in developed countries4. NDD and/or ID are common manifestations of various genetic neurodevelopmental disorders, and they are often associated with epilepsy, ASD, and ADHD, which are the three most frequent neurodevelopmental comorbidities in patients with NDD with a known genetic cause5,6. Developmental epileptic encephalopathies (DEE) are a group of NDD/ID conditions in which uncontrolled epileptic activity plays a deleterious role in the regression or further slowing of neurodevelopment7. Indeed, in DEE, epileptic activity “per se” can contribute to severely impair cognitive and behavioral development, above what is expected from the underlying pathology, and the developmental consequences may improve with the amelioration of the epileptiform activity8. Encompassed in the group of DEEs, encephalopathy related to status epilepticus during sleep (ESES), recently labeled as DEE with spike-wave activation during sleep (DEE-SWAS) (hence the label ESES/DEE-SWAS that we use in this paper), refers to epileptic conditions, often with a genetic cause, that are characterized by various combinations of cognitive, language, behavioral, and motor disturbances whose onset or worsening is associated with the appearance of a marked enhancement of EEG epileptiform activities during sleep9.

To date, over 1300 causative genes and 1100 candidate genes related to NDD/ID pathogenesis have been identified, and the number continues to grow annually10,11. Making a correct and prompt diagnosis of a genetic neurodevelopmental disorder is important to end a lengthy, resource-consuming diagnostic odyssey, to improve treatment, to inform management even in the absence of established curative or disease-specific therapies, and to provide counseling to patients and families.

The CELSR1 gene (also known as FMI2, OMIM *604523), located on chromosome 22q13.31 in humans and chromosome 15 in mice, encodes a developmentally regulated protein that belongs to the adhesion G protein-coupled receptors (adhesion GPCR)11,12,13,14. The CELSR1 protein is a core component of the tissue/planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling, which governs multiple cell polarization-dependent processes such as convergent extension, oriented cell division, and directional migration13,14,15,16. It is characterized by a large extracellular domain that contains nine contiguous cadherin repeats, eight epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains intermixed by three laminin A G-type (LAG) repeats, followed by a GAIN (G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) autoproteolysis-inducing domain) with the proteolytic site (GPS)17, (WWW.NCBI.NLM.NIH.GOV/GENE/9620). The N-terminus is followed by seven transmembrane domains, and an intracellular C-terminal tail with no clear motives. CELSR1 is believed to mediate homotypic interactions and connect the extracellular matrix to the cytoskeleton. It is involved in morphogenesis of several organs and systems including the kidney, lung, skin, prostate, salivary gland, trachea, thyroid, urogenital tract, and lymphatic system12,17,18,19,20,21,22. Variants in the CELSR1 gene have been linked to congenital defects in the vestibulocochlear system23,24, heart25, kidney26, and lung21. A link between CELSR1, lymphatic system development, and lymphoedema has also been documented for heterozygous LOF variants22,27,28,29. In the nervous system, CELSR1 is highly expressed in neuroepithelial cells during the prenatal period, as well as in neural progenitors and ependymal cells in the postnatal brain20,30 (HUMAN.BRAIN-MAP.ORG). Pathogenic CELSR1 variants were associated with neural tube closure defects and caudal agenesis23,31,32,33,34,35.

In mice, CELSR1 plays a crucial role in the neurogenic switch during histogenesis of the cerebral cortex. In the absence of CELSR1, cortical progenitor cells undergo more proliferative divisions at the expense of neuron production, causing cortical hypoplasia, learning and memory deficits, and autistic-like behavior36. In the developing rhombencephalon, CELSR1 is involved in the directionality of tangential migration of facial nerve motor neurons37. CELSR1 is also key to ependymal cilia polarization and ciliary beats, and its loss severely disrupts the circulation of the cerebrospinal fluid and results in hydrocephalus30.

Here, we report in humans a distinctive neurodevelopmental disorder encompassing various types of brain malformations, NDD, ID, epilepsy, dysmorphic features, and psychiatric/behavioral comorbidities, associated with compound heterozygous or homozygous variants in CELSR1. We correlate this with Celsr1 knockout (KO) mice analysis, which recapitulates the human findings and provides insights into the cellular mechanisms that underlie morphological and behavioral defects.

Results

Patient’s data

Clinical characteristics

We collected seven individuals (five females, two males; age range: 1 month–15 years) with deleterious biallelic CELSR1 variants from five unrelated families; family pedigrees of patients #1 and #2 and of patient #4 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Main clinical information of the affected individuals is summarized in Table 1 (detailed clinical information of patients are reported in Supplementary Notes). Four patients were born at term, three were born moderate to late preterm, after an uneventful pregnancy. One patient died at 1 month of age because of the severity of the clinical picture. Patients #1 and #2 are siblings of related cousins, and there is a strong recurrence of intellectual disability in the family—in five cousins—and one first-degree cousin affected by epilepsy not further specified (Supplementary Fig. 1). The parents of patient #4 are also related and two of his cousins (two sons of related parents) have a neurodevelopmental disorder, not further specified.

Behavior and neurodevelopment

A neurodevelopmental delay, ranging from mild to severe, was observed in all assessable patients. Three patients (#1, #2, and #5) were mildly impaired and attended a school for children with special needs. A mild language delay that improved over time was reported in patients #1, #2 and #5. Patients #3, #4, and #6 displayed a moderate neurodevelopmental delay, with a lack of verbal communication, expressing themselves only by single words. Attention/deficit hyperactivity disorders (ADHD) were reported in patients #2, #3, and #4. In addition, patients #3 and #4 were affected by auto- and hetero-aggressive and autistic features. Two monozygotic twin patients (#5 and #6) had a diagnosis of ASD and had an avoidant restrictive food disorder. The last patient (#7) displayed an extremely severe clinical picture with a severely depressed reactivity to external stimuli and no active movements immediately after delivery, with no spontaneous breathing and swallowing reflex, that led to death at 1 month of age, despite intensive care treatment.

Epilepsy and EEG features

Four out of seven patients suffered from epilepsy (Table 1). Patients #1 and #2 were affected by pharmacosensitive epilepsy since the ages of 6 and 3 years, respectively. Seizures were characterized by brief episodes of staring and eyelid myoclonias. EEG recordings displayed diffuse 3.5–5 Hz spike/polyspikes and wave discharges, enhanced by activating procedures, such as hyperventilation and intermittent photic stimulation (IPS). IPS elicited a photoparoxysmal response at frequencies ranging from 6 to 25 Hz (patient #1) and from 6 to 30 Hz (patient #2) (Fig. 1a, b). Patient #3 had the first bilateral tonic-clonic seizure in early adolescence, with good control of the epilepsy after introduction of anti-seizure medications. EEG showed global background slowing. Patient #4 presented with atypical febrile seizures in early infancy and later developed focal non-motor seizures and status epilepticus. Seizure control with anti-seizure medications was achieved at the age of 6 years. From 5 to 8 years of age, he presented with a cognitive regression and language deterioration associated with a remarkable enhancement of the EEG epileptic activity during non-REM sleep compatible with ESES/DEE-SWAS, which later remitted following appropriate treatment, with an amelioration of the cognitive status.

a EEG tracing in patient #1 during intermittent photic stimulation, showing the appearance of a generalized discharge of irregular fast activity triggered by eye-closure, associated with eyelid myoclonias. b EEG tracing in patient #2 during hyperventilation, showing irregular generalized spike-wave discharge, preceded by a brief run of fast activity in the posterior regions. c EEG tracing in patient #4, showing extreme activation of spike-wave activity during NREM sleep, reproducing the EEG pattern of ESES/DEE-SWAS. EEG electroencephalogram, NREM non-rapid eye movement sleep, pt patient, wkf wakefulness, y years. Source data are provided in the Source Data file.

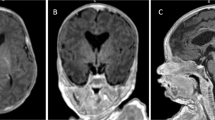

MRI findings

MRI showed malformations of cortical development in four out of six available neuroimaging studies (Fig. 2). In patients #1 (Fig. 2a–c) and #2 (Fig. 2d–f), the MRI disclosed pachygyria, with antero-posterior gradient, sparing the occipital lobes associated with several spotty subcortical white matter abnormalities. Patient #3 (Fig. 2g–i and Supplementary Fig. 2) had focal gray matter heterotopia in the right lateral ventricle and non-specific abnormalities, such as a coarse and small corpus callosum, and enlarged lateral ventricles. In patient #7 (Fig. 2j–l), brain MRI showed cerebral atrophy with enlarged frontal subarachnoidal spaces with septum pellucidum cyst, and brainstem and cerebellum atrophy. In patients #4 and #6, MRI was unremarkable.

a–c Coronal FLAIR, axial, and sagittal T1-weighted (T1W) brain MRI of patient #1 showing rounded subcortical white matter abnormalities, mainly in the frontal lobe, partly confluent (a, arrows) and pachygyria, with an antero-posterior gradient (b, c, arrows), sparing the occipital lobes. d–f Coronal FLAIR, axial, and sagittal T1W brain MRI of patient #2 showing isolated subcortical white matter abnormalities, mainly in the frontal lobe (d, arrows) and pachygyria, with an antero-posterior gradient, sparing the occipital lobes (e, f, arrows). g–i Axial T2W, axial T2W FLAIR, and sagittal T1W brain MRI of patient #3 showing microcephaly with normal gyration, focal gray matter heterotopia in the mesial wall (g), temporal horn (h), and frontal horn (i) of the right lateral ventricle and enlarged lateral ventricles (arrowhead). j–l Axial T2 weighted, coronal FLAIR and sagittal FIESTA brain MRI of patient #7 at 10 days of life showing septum pellucidum cyst (arrowhead) and mild enlargement of frontal subarachnoidal space (white arrow) (j), cerebral atrophy and cerebellar (k, arrow) and brainstem atrophy (l, arrow). Additional MR figures of patient #3 are available as Supplementary Fig. 2. Source data are provided in the Source Data File.

Dysmorphisms and other comorbidities:

Description of facial gestalt was available in all patients, and clinical pictures were available in 3/7 patients (#1–3). Patients #1, #2, and #4 were non-dysmorphic. In contrast, patient #3 had upslanting palpebral fissures, medial sparseness of eyebrows, flat nasal bridge and retrognathia (Fig. 3). Twin patients (#5 and #6) showed deep-set hooded eyelids, epicanthal folds, broad nasal tip, thick lips, narrow palate, diastema of teeth, short neck, and unilateral hockey-stick crease. One (#3) out of seven patients had microcephaly, with a range of −3 to −4 SD at last follow-up, and with a progressive course. Patients #5 and #6 had a history of vesicoureteral reflux with recurrent urinary infections, eczema and otitis. The latter was affected by acute meningitis at the age of 4 years. Patient #7 showed multiple contractures of large and small joints, hip dysplasia, arthrogryposis, hirsutism and cryptorchidism. Muscle biopsy revealed wide areas of fibrosis with loss of clear muscle bundles, variability of the size and partial necrosis of muscle fibers (Supplementary Fig. 3). Other features included visual defects (#1) and asthma (#4).

Genetic findings

We identified five variants, not reported previously, four in the following compound heterozygous states—(i) NM_014246.4:c.2935 C > T NP_055061.1:p.(Leu979Phe) and c.7456 G > C p.(Ala2486Pro); (ii) c.2018T>C p.(Val673Ala) and c.7012 G > A p.(Val2338Ile), (iii) c.3601 G > A p.(Asp1201Asn) and c.4436 T > A p.(Leu1479His), (iv) c.1210 G > A (p.Glu404Lys) and c.4415 C > G (p.Thr1472Ser) and one homozygous variant c.2935 C > T p.(Leu979Phe) in five unrelated families. The variant p.(Leu979Phe) recurred in three Kurdish patients (#1, #2, #4); two of them are siblings and the third patient is unrelated. The other variants were found in one patient each. One variant (c.4436 T > A p.(Leu1479His) in patient #5 and #6) occurred de novo. All other variants were inherited from healthy heterozygous parents. All variants were rare (population allele frequency ≤0.0002652) or not observed in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) representing healthy people (Supplementary Data 1). Patient #3 carries two additional variants: a de novo (NM_000284.4:c.900-7_932dup, NP_000275.1:p.(?)) duplication in PDHA1 and a paternally inherited (NM_145239.3:c.649dup NP_660282.2:p.(Arg217ProfsTer8)) frameshift variant in PRRT2 variant. Pathogenic PRRT2 variants have been associated with infantile movements disorders, familial infantile convulsions and self-limited epilepsy38, features that are not detected in our patient. Pathogenic PDHA1 variants are causing mild dysmorphism, various neurological symptoms, such as congenital hypotonia, severe encephalopathy, agenesis of the corpus callosum, and diffuse hypomyelination. Furthermore, biochemical abnormalities such as increase of blood alanine, increase of blood and urinary lactic and pyruvic acid, as well as hyperammonemia are often observed in PDHA1 patients39,40. These biochemical abnormalities were not detected in our individual, thus suggesting a limited, if any, role of the PDHA1 variant.

In Silico characterization of CELSR1 biallelic variants

It is acknowledged that most variant predictors lack some in performance. SIFT and CADD has been reported with accuracy of 0.7146 and 0.7198 and a precision of 0.7771 and 0.7453, respectively41. In the same way, Polyphen2 has been reported with a specificity of 0.73 and a sensitivity of ~0.8742. Thus, we decided to comprehend the structural consequences of the ascertained genetic variants, by using 3D structural models based on sequence homology to known protein crystal structures (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Glu404 (yellow) stabilizes the E-D-loop by hydrogen bonds to Tyr390 (pink). The substitution Glu404Lys destabilizes the loop. b Illustration of the highly conserved Val673 (raspberry) backbone hydrogen bonds to Phe655 (pink). The substitution Val673Ala destabilizes the E-D-loop and thereby the cadherin domain. c Electrostatic interactions between Leu979 (aquamarine; red arrow) and Asp972 and interactions with the Ca2+-ions are illustrated. Substituting Leu979 with phenylalanine will cause steric interference with Asp972 and Asn886. d The amino acid Asp1201 (yellow stick) interacts via backbone hydrogen bonds with Leu1203, Thr1204, and Asn1205 (pink) stabilizing the Ca2+-binding domain. The Asp1201Asn substitution causes steric interference with Asn1205, destabilizing the Ca2+ binding domain. Conserved Amino acids are indicated in yellow. e Thr1472 (yellow) form backbone hydrogen bonds to Gly1525 and hydroxyl bond to Glu1474 and Arg1838 (all in pink). The Thr1472Ser substitution will abolish the hydroxyl bond and destabilize the structure. f Leu1479 (yellow) forms hydrogen bonds to Leu1494 and Gly1268 (both pink). The substitution Leu1479His will result in steric interference with Thr1472 and Gly1477, destabilizing the highly conserved laminin-neurexin globular cysteine disulfide bridge between Cys1840 and Cys1870 (not highlighted). g The Val2338 (red) and its polar bonds to Phe2253 (light blue) are illustrated. Red arrows depict the autoproteolytic site between β-sheet 19 and the highly conserved β-sheet 20 (orange). Polar bonds stabilizing the GPS domain is illustrated by blue dots. The substitution Val2338Ile is predicted to hamper autoproteolysis. The two pairs of conserved disulfide bonds are illustrated by yellow sticks. h The Ala2486Pro substitution will cause a kink and is incompatible with alpha helical structure. Crystal structure PDB numbers and the associated protein domains of the individual figures are described in the Results section. Hydrogen and polar bonds are illustrated by dashed yellow lines.

The crystal structure of the extracellular cadherin domains 1 to 4 of CELSR1 is reported as PDB no. 8D40. The position of the genetic variant p.(Glu404Lys) is situated in CELSR1 cadherin domain 2 in the loop between strands E and D. Glu404 stabilizes the loop forming polar contacts to Tyr390 (Fig. 4a). The substitution Glu404Lys destabilizes the E-D-loop destabilizing the cadherin repeat.

Embedded in the beta strand A of cadherin domain 4, Val673 displays complete conservation between CELSR1, 2 and 3, and a high conservation throughout the Cadherin Major Branch (CMB) (Supplementary Fig. 4), almost only being replaced by other amino acids with hydrophobic side chains. In the crystal structure of human CELSR1 extracellular cadherin domain 4–7, PDB no. 7SZ8. Val673 is positioned in strand B establish backbone hydrogen bonds to Phe655 on strand E (Fig. 4b). The substitution Val673Ala destabilizes the E-D-loop and thereby the cadherin domain. The Ser741Ile substitution in CELSR3 corresponds to the Ser672Ile substitution in CELSR1 which previously has been reported as pathogenic causing tetralogy of Fallot25.

The residue Leu979 is situated in the linker between cadherin domains 7 and 8. The position is illustrated in a crystal structure based on Homo Sapiens Protocadherin GammaB4, PDB no. 6E6B ref. 43 (HHpred Probability: 99.74%, E-value: 6,8e-11, PHYRE2 confidence 100,00%) (Fig. 4c). Polar interactions are shown. Leu979 displays interaction with Asp972. Substituting Leu979 with phenylalanine will cause steric interference with Asn886 and additionally destroy the bond to Asp972, both involved in Ca2+ binding. The result will be destabilization of the essential extracellular Ca2 + -binding domain of the cadherin repeat, leading to a dysfunctional protein structure.

The position of Asp1201 is deduced using the crystal structure of Sus Scrofa Protocadherin-15, PDB no. 6BXZ ref. 44 (HHpred probability: 98.08%, E-value: 0.0067) (Fig. 4d) and is part of the ninth cadherin domain of CELSR1. Asp1201 is part of the Ca2+-binding loop between strands B and C, stabilizing the loop forming backbone hydrogen bonds to Leu1203, Thr1204, and Asn1205. The substitution Asp1201Asn will result in steric clashes with Asn1205.

The crystal structure of Bos Tarus Neurexin-1-alpha PDB no. 3POY ref. 45 (HHpred probability 99.58%, E-value: 4.4e-13, PHYRE2 confidence 99.9%) served as a model for the laminin G-like1 domain harboring Thr1472 (Fig. 4e) and Leu1479 (Fig. 4f). Thr1472 forms backbone hydrogen bonds to Gly1525 and hydroxyl bond to Glu1474 and Arg1838. The p.(Thr1472Ser) substitution will destabilize the loop between strand C and D of the globular structure. Leu1479 is positioned in strand D forming hydrogen bonds to Leu1494 and Gly1268 in KL-loop harboring the highly conserved cysteine disulfide bridge between Cys1840 and Cys1870. The p.(Leu1479His) substitution will result in steric interference with Thr1472 and Gly1477. The GAIN-GPS has been modeled using the crystal structure PDB no. 4DLQ ref. 46 of Rattus Norvegicus CIRL 1/Latrophilin 1 (CL1) (HHpred Probability: 99.2%, E-value: 1e-9, Phyre confidence 99,95%, intensive mode). The GAIN (G—protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) autoproteolysis-inducing domain) domain of CELSR1 is followed by the GPS domain. Val2338 is situated in the olfactomedin part of the GAIN domain (Fig. 4g) and is part of the GAIN domain binding pocket for the tethered agonist. Situated in sheet 11, Val2338 forms two polar bonds to Phe2253 in sheet 8. Introduction of the p.(Val2338Leu) substitution will cause a change in distance between these two b-sheets (11 and 8) hypothesized to cause a conformational change destabilizing the GPS-autoproteolytic-GAIN domain that then is predicted to decrease or abolish the essential autoproteolysis function at the site between sheet 19 and 20.

For the transmembrane region of CELSR1, a crystal structure based on Homo Sapiens adhesion G protein-coupled receptor L3 (AGRL3), PDB 7SF7 ref. 47 (HHpred Probability: 99,93%, E-value: 2,3e-22, SWISS-MODEL Ramachandran Favored 92,86%, PHYRE2 Confidence 99,9%, intensive mode) was used (Fig. 4h). This region consists of seven transmembrane alpha helixes (TM1–TM7). Ala2486 is situated in the alpha helix constituting TM1. Substituting Ala2486 with a proline will cause a kink and is not compatible with alpha helical structure. The p.(Ala2486Val) substitution is seen in GnomAD. However, alanine and valine are two amino acids with very similar structures and size; hence, this substitution is in contrast to the p.(Ala2486Pro) substitution predicted to preserve the alpha helical structure.

In Supplementary Table 1, the quality parameters of the templates used are listed. Taken together, the above predicted 3D structures present with a very high structural confidence, supporting the strength of the predicted functional consequence of the genetic variants. The recently published structure of CELSR1 is in agreement with our data48. PyMol sessions are available as Supplementary Data 2.

The phenotype of Celsr1 KO mice recaps the human findings

We have previously reported that Celsr1 KO mice exhibit defective embryonic neurogenesis and cilia polarization that result in cortical hypoplasia, enlarged lateral ventricles, learning and memory deficits, and autistic-like behavior30,36. Here, we focused on the postnatal brain. We examined coronal sections from Celsr1 KO mice (n = 17 mice from 33 litters), heterozygotes (n = 119), and control littermates (n = 61) following Cresyl Violet (Nissl bodies), and Luxol Fast Blue (myelin) staining. Heterozygous mice were indistinguishable from controls. Celsr1 KO mice exhibited agenesis of the caudal corpus callosum (Fig. 5a, b). The phenotype was fully penetrant and background independent, as backcrossing on C57Bl/6 or CD1 (eight generations) did not affect the phenotype. The hippocampal commissure was also absent in the KO mice. Tag1 immunostaining at postnatal day (P)0, showed that pioneer callosal axons failed to cross the midline and run along the rostral-caudal axis, forming so-called Probst bundles (Fig. 5c). Glial cells of the indusium griseum were absent in KO mice. The glial wedge that behaves as a repulsive cue towards extending axons49, although present, showed a wider interhemispheric spacing (Fig. 5c). To further characterize the callosal axon defects, we performed axonal tracing using DiI, which confirmed the absence of crossing callosal axons and emphasized their rostrocaudal as well as ventral trajectories (Fig. 5d).

a, b Representative images of the hippocampal commissure phenotype. Coronal sections stained with Cresyl Echt Violet (Nissl bodies, a) or Luxol Fast Blue (Myelin, b) from adult control (Celsr1 wildtype, left) (Ctrl) and Celsr1 KO mice (right). Note the absence of the corpus callosum in the KO. c Coronal sections from control (left) and Celsr1 KO (right) newborn mice were immunostained with Tag1 (green) to show pioneer callosal axons, and GFAP (magenta) to reveal glial cells involved in the midline crossing of these axons. Tag1 immunostaining, showed that callosal axons fail to cross the midline and run along the rostral-caudal axis, forming the Probst bundles (pb). Glial cells of the indusium griseum (IG, magenta) were absent in the KO. The glial wedge that expresses GFAP and behaves as a repulsive cue towards extending axons, although present, showed a wider interhemispheric spacing. d Representative images of DiI tracing. Callosal axons could be traced to the contralateral hemisphere in the control, but not in the KO mice. Lower panels in (c, d) show higher magnifications of the boxed areas in the corresponding upper panels. Callosal pioneer axons fail to project to the contralateral hemisphere in the KO mouse. Observations without quantification have been validated and successfully reproduced in a minimum of three different animals. Scale bars, (a, b) 500 µm, (c, d) 500 µm upper panels, 200 µm bottom panels. AC anterior commissure, CC corpus callosum, Cx cortex, DG dentate gyrus, GW glial wedge, HC hippocampus, IG indusium griseum, pb Probst bundles. Uncropped and unprocessed data are available as Supplementary Fig. 5.

The Celsr1 KO mice also displayed periventricular heterotopia, particularly around the subventricular zone (Fig. 6a–d). Heterotopias are usually due to fate determination and/or neuronal migration defects. We have previously reported that during embryogenesis, neural progenitors undergo more proliferative divisions at the expense of neuron production, leading to local accumulation of cells and widening of the ventricular/subventricular zones (Fig. 6b)36. To assess radial migration, we injected pregnant dames intraperitoneally with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) at embryogenic day (E) 14.5 and analyzed the brain at postnatal day (P)0. Like in control mice, BrdU- and Cux1-positive neurons were seen in the outer tier of cortical ribbon in Celsr1 KO, suggesting that radial migration, layering, and inside-out gradient of cortical maturation were not dramatically affected by the lack of CELSR1 (Fig. 6e, f). However, the density of BrdU-positive cells was significantly higher in the mutant ventricular zone (Fig. 6f, g; Source Data File).

Periventricular heterotopias in Celsr1 KO mice. a–d Forebrain coronal (a, b) and sagittal (c, d) sections from P21 control (Celsr1 wildtype) and Celsr1 KO mice stained with Cresyl Violet (Nissl). Boxes in (a, c) indicate the regions magnified in (b, d), respectively. Compared to controls, the ventricular zones are thicker in the KO mice and display irregular shape and nodular heterotopias (arrowheads). Observations without quantification have been validated and successfully reproduced in a minimum of three different animals. e Nissl attained coronal hemisection, indicating the region for the high magnification in (f). f Forebrain sections immunostained with anti-BrdU (green) and anti-Cux1 (red) antibodies. g Quantification of the number of BrdU-positive cells in the ventricular zone (VZ) of the cortex (Ctrl: 36.87 ± 3.5 cells/0.01 mm2; KO: 56.47 ± 6.1 cells/mm2; p = 0.049) n = 3 for Ctrl and KO mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Values were obtained by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test; ns not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Scale bars, (b, d) 100 μm, (f) 100 μm left panel and 25 μm for the magnification panel. Uncropped and unprocessed data are available as Supplementary Fig. 5. Source data are provided in the Source Data File.

In the postnatal brain, Celsr1 mRNA was expressed in the subventricular zone and the rostral migratory stream (RMS), and its loss led to a marked atrophy of olfactory bulbs (OB) in adult mice (Fig. 7a–c). We used an antibody against Doublecortin (Dcx), which specifically labels neuroblasts and delineates the RMS. In control mice, Dcx-positive cells were located in OB and along the RMS. These cells accumulated around the ventricles, particularly in the SVZ, and in the proximal RMS in Celsr1 KO (Fig. 7d, e). Dcx immunoreactivity was also detected ectopically in the frontal cortex. To further characterize the tangential migration of neuroblasts, we injected adult mice intraperitoneally with BrdU for 3 consecutive days and analyzed the distribution of BrdU-positive cells 9 days after the last injection (~5 days are necessary for adult neural stem cells to differentiate into neuroblasts and migrate from SVZ to OB). Immunostaining with anti-BrdU antibodies showed that the number of BrdU-positive cells was greater in the Celsr1 KO SVZ compared to controls (Fig. 7f–k; Source Data File). These results, together with Dcx immunostaining, suggest that neuroblast migration is disrupted in Celsr1 KO mice. Instead of moving rostrally toward OB, they accumulated in the periventricular areas, leading to a progressive depletion of olfactory interneurons and hypotrophy of OB.

a Freshly dissected mature brain depicting the sectioning plan and position (white line) of the section shown in (b). b Photograph of an autoradiography film from a parasagittal section hybridized with a Celsr1 riboprobe. Celsr1 mRNA is found in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and rostral migratory stream (RMS). c Photographs of dissected adult brains from control (left) and Celsr1 KO (right) mice. The olfactory bulbs (OB), and to a lesser extent the cerebellum, are reduced in the KO mice. d Nissl-stained sagittal section highlighting the subventricular zone and rostral migratory stream. The box area represents the brain region analyzed in (e). e Sagittal sections immunostained with anti-doublecortin (Dcx, green) antibodies. Neuroblasts populate the olfactory bulb and outline the rostral migratory stream in control, but not in Celsr1 KO mice. Observations without quantification have been validated and successfully reproduced in a minimum of five different animals. f Coronal hemisection of the mouse forebrain, indicating the region analyzed in (g) and (h) (boxed area). g BrdU staining at the rostral aspect of the lateral ventricle. h Quantification of the BrdU staining. Celsr1 KO mice have a higher density of BrdU-positive cells in the rostral SVZ (Ctrl: 120.3 ± 10.2 cells/mm2; KO: 191.4 ± 11.4 cells/mm2; p = 0.0001). i Coronal hemisection labeled with Cresyl Violet (Nissl), indicating the regions magnified in (j). j BrdU staining at the caudal aspect of the lateral ventricle. The white boxes indicate the region where the counting was performed. k quantification of the number of BrdU-positive cells at the caudal aspect of the lateral ventricle (Ctrl: 47.18 ± 6.8 cells/mm2; KO: 91 ± 8.8 cells/mm2; p = 0.0007). Note the enlarged ventricles in the Celsr1 KO mice. (n = 12 sections from three different animals for Ctrl and KO mice). Data were represented as mean ± SEM. Values were obtained by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test; ns not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. CC corpus callosum, CPu caudate putamen (striatum), V ventricle. Scale bars, (b, c) 1 mm, (e) 800 μm, (g) 200 μm, (j) 400 μm. CC corpus callosum, CPu caudate putamen (striatum), fi fimbria of the hippocampus, V ventricle. Uncropped and unprocessed data are available as Supplementary Fig. 5. Source data are provided in the Source Data File.

Table 2 summarizes the brain malformations in KO mice in comparison with our patients. A small proportion (20%) of Celsr1 KO mice exhibited spontaneous epileptic seizures starting from the third postnatal week (Supplementary Movie 1). We evaluated the susceptibility of KO mice to pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures in comparison with control littermates. Age- and sex-matched animals of different ages (2–12 months, n = 10 per genotype) were injected with 35 mg/kg of PTZ and visually monitored for 30 min. Control mice displayed neither behavioral nor immobilization disturbances. In sharp contrast, young adult KO mice (≤4 months, n = 4) had generalized seizures (Supplementary Movie 2), whereas mature KO mice (>4 months, n = 6) displayed continuous whole-body myoclonus. Uncropped and unprocessed data of Fig. 5–7 are available as Supplementary Fig. 5

Discussion

We describe a neurodevelopmental disorder with structural brain malformations, NDD, ID, epilepsy, behavioral disturbances, and dysmorphic features due to likely pathogenic variants in CELSR1. These phenotypic features showed a high degree of variability in our cohort, in particular, NDD and ID could range from mild to very severe, language could vary from normal to severely delayed, dysmorphisms were present only in 3/7 of the patients as well as epilepsy who affected 4/7 individuals, and whose severity ranged from self-limited epilepsy to a DEE (ESES/DEE-SWAS). Finally, various types of brain malformation were observed. Indeed, our study cohort shows that genetic variants in CELSR1 can be associated with different types of brain malformations such as pachygyria, periventricular nodular heterotopias, abnormalities of the corpus callosum and hypoplasia of the brainstem and cerebellum in four out of six patients for whom MRI studies were available. Pachygyria and PNH are common causes of developmental delay and epilepsy50. Pachygyria is included in the larger group of lissencephalic syndromes, and it is characterized by decreased cortical convolutions, cortical thickening, and a smooth cerebral surface51,52,53. Pathogenic variants in DCX, ACTB, DYNC1H1, ACTG1, KIF5C, VLDLR, CRADD, ARX genes have also been associated with pachygyria54. Most children affected by lissencephalic syndromes, including pachygyria, come to medical attention during the first year of life due to neurological deficits, ongoing feeding problems and, often intractable, epilepsy50,53. Interestingly, both patients (#1 and #2) with pachygyria had a favorable course with complete seizure control with anti-seizure medications. PNH consists of nodules of gray matter located along the lateral ventricles with a total failure of migration of some neurons54. A large number of genes have been associated with PNH54, with pathogenic variants in FLNA being the most common cause50. Although, most patients with PNH suffer from focal epilepsy of variable severity, there is a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, including several syndromes with intellectual disability and dysmorphic facial features. In individuals with PNH and no other brain malformations, seizures and learning problems are common. When microcephaly or other brain malformations are diagnosed, the likelihood of cognitive impairment, increases greatly, as it appears in our patient #3, who features PNH with several nodules, associated with dysmorphic lateral ventricles, coarse and small corpus callosum, and microcephaly. Epilepsy is the most common and often the presenting disorder among all PNH forms, being reported in 80–90% of patients50, as in patient #3. Four (#1, #2, #3, #4) out of seven patients suffered from drug-responsive epilepsy. As above reported, MRI showed pachygyria in patients #1 and #2, PNH in patient #3, whereas it was normal in patient #4. In particular, patients #1 and #2 presented with an epileptic condition that resembles the syndrome of eyelid myoclonia with absences55, a syndrome currently included in the group of genetic generalized epilepsies7. Patient #3 has been recently diagnosed with epilepsy after the recurrence of episodes of bilateral tonic-clonic seizures. Patient #4 presented with epilepsy characterized by atypical absences, bilateral tonic-clonic seizures and evolution to ESES/DEE-SWAS during the course of the disease, followed by amelioration and eventually complete seizure control. Seizure types and EEG features were consistent with a generalized type of epilepsy in this patient. Overall, in all four patients, the clinical semiology of the seizures and the interictal EEG were compatible with generalized seizure types and suggested that our patients suffered from generalized epilepsy with a favorable outcome and good response to anti-seizure medications.

Abnormal neurodevelopment and cognitive impairment were common features in all our patients, ranging from mild (patients #1, #2, and #5) to moderate (#3, #4, and #6). In addition, one patient (#7) was born with an extremely severe, compromised global status, which led to death at one month of age. Cognitive disorders affected primarily the language domain and executive functions, the acquisition of motor control and coordination. In addition, three out of seven patients (#2, #3, and #4) exhibited ADHD, and three patients (#4, #5, and #6) were diagnosed with ASD.

To our knowledge, this association between the currently described phenotype and pathogenic variants in the CELSR1 gene has not been reported previously. Only one patient affected by a heterozygous 22q13.31 microdeletion, including the critical region of CELSR1, has been described56. Interestingly, this patient exhibited some features such as developmental delay/intellectual disability, speech delay/language disorders, behavioral problems, hypotonia, and hands/feet anomalies that overlap with those observed in our cohort.

In addition, none of the patients with mild epilepsy harboring CELSR1 variants reported recently57, exhibited the cognitive and behavioral profile and the MRI features of our patients.

In mice, Spin cycle (Scy) and Crash (Crsh) heterozygous variants of Celsr1, encoding dominant negative forms of the protein, have been associated with inner ear developmental abnormalities, head bobbing, congenital heart disorders and neural tube defects23. None of our patients shows these defects. Interestingly, a functional analysis has demonstrated that one of these variants p.(Pro870Leu) leads to a gain-of-function effect, suggesting that these phenotypes have a different pathogenesis25. More recently, some studies proposed the association of missense and truncating heterozygous variants of the gene with lymphedema27,29. In the literature25, six patients have atrial septal defect associated with CELSR1 variants, with five out of six presenting with other associated cardiac malformations. However, none of the published patients are compound heterozygous for pathogenic variants in CELSR1, and none of the patients have the variants that we report here. Different levels of residual protein could affect the phenotype differently at the different stages of development and thereby lead to different phenotypes and organ involvement. This implies that different pathophysiological mechanisms may correspond to distinct clinical presentations.

Utilizing protein crystal structures based on agreement between different protein structure predictors and sequence alignment using MUSCLE (MUltiple Sequence Comparison by Log- Expectation), we created 3D homology structures, which allow assessment of the predicted functional consequence of the reported missense variants. The predicted models are considered highly reliable based on the quality of the templates used, the estimate of the modeling match, functional similarities and the overall sequence similarity between the template and the CELSR1 domain under investigation. These data, together with the prediction tools, enabled us to evaluate the possible functional effect of all individual variants, classifying the variants as not compatible with normal function. Functional analysis in cells and animal models bearing these variants should help assess the residual level, trafficking, subcellular partition, and function of the mutated proteins.

Complete loss of CELSR1 in mice affects several polarity-dependent processes during embryonic development, including cortical neurogenesis, directional migration of neurons along the rostrocaudal axis, and polarization of ependymal cells30,36,37. In agreement with this, it has been associated with microcephaly, hydrocephalus, learning and memory deficits, ADHD, and autistic behavior36. We extended our analysis to the postnatal brain of Celsr1 KO mice and report three main findings. First, agenesis of the corpus callosum has a 100% penetrance even though the agenesis is partial in most cases and involves only the caudal part. This was explored by immunofluorescence and axonal tracing. Using GFAP immunostaining, we found that the number of cells that guide callosal axons was reduced, and the residual cells were mislocalized. Second, periventricular heterotopia and irregular shape of the ventricular/subventricular zone due to a compromised type of division of progenitors and migration of neuroblasts in the postnatal brain. This impairs the renewal of olfactory interneurons, ultimately causing OB atrophy. It may be argued that the olfactory bulb phenotype could be due to defects during embryonic development, as we use constitutive KO mice. We believe however that this is unlikely for two reasons: (i) the tangential migration of neuroblasts to olfactory bulb occurs mainly in the postnatal brain; (ii) we did not observe abnormality at birth and the first signs of a reduction of the olfactory bulb appear only after 1 month after birth. In humans, postnatal neurogenesis is debated58,59. Nevertheless, a landmark study showed that a proportion of the SVZ-derived neuroblasts branch off the RMS and migrate toward the frontal cortex through a so-called medial migratory stream (MMS)60, wherein pachygyria was found in patients #1 and #2. Third, enlarged lateral ventricles with a fully penetrant phenotype. These features were also seen in our patients. In fact, two out of six patients, with available MRI studies, have some abnormalities of the corpus callosum and enlarged ventricles. Other recurrent features are microcephaly and PNH. Differences in penetrance between mice and humans could reflect differences in the variant types. Heterozygous mice have no noticeable phenotype. The KO mice have a complete loss of CELSR1 function and exhibit the full phenotype. Most of the patients reported in this paper have biallelic variants in CELSR1, and this may result in a reduction of the functionality of the protein rather than a complete abolition, thus leading to a partially penetrant phenotype with variable features or may result in various levels of gain-of-function. CELSR1 is widely expressed in the central nervous system during fetal life, while the expression decreases during postnatal life. This developmentally regulated expression emphasizes the importance of the gene during brain development. CELSR1 is a PCP protein15, which integrates global directional signaling to produce locally polarized cell behaviors that control division of neural progenitors and chain-migration of neuroblasts. Moreover, its expression in the ependymocytes is pivotal for polarization of ependymal cells, efficacy of ciliary beats, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation. The enlarged ventricles, a constant feature of Celsr1 KO mice found in some patients, is likely due to its dysfunction in ependymal cells61,62. CELSR1 has also been hypothesized to play a role in rostrocaudal patterning during organogenesis, and its role has been implied also in renal tract development in murine models26.

The phenotype and transcriptional landscape of Celsr1 KO mice indicate that neural progenitors’ cells fail to perceive critical neurogenic signals36. Among these signals, retinoic acid (RA) delivered by meningeal cells plays a role in controlling the fate decision of neural progenitors, switching from proliferative to neurogenic divisions at the onset of neurogenesis36. In Celsr1 KO mice, long-term supplementation of RA rescued a proportion of cortical neurons with marked consequences on the mature brain and behavior of the adult mice. On the other hand, removal of the RA-producing meninges produced a phenotypic picture resembling the phenotypic picture of Celsr1 KO mice. Altogether, these data suggest a relationship between RA and the Celsr1 KO phenotype36.

In conclusion, our findings provide evidence supporting CELSR1 as an additional gene in which pathogenic variants can cause a neurodevelopmental disorder featuring variable degrees of NDD/ID, brain malformations, and epilepsy. Regarding phenotype-genotype associations, our findings, together with the data in the literature, suggest that heterozygous protein truncating or splice-site variants leading to haploinsufficiency will likely be associated with lymphedema while biallelic heterozygous or homozygous missense variants, as in our cohort, likely exhibit a primarily neurodevelopmental phenotype. In the approaching era of precision medicine and disease-modifying treatments, our observations might suggest new pathways for investigating and developing targeted treatments in CELSR1-mutated individuals that might require an early, even prenatal, administration with the aim to improve the developmental outcome, epilepsy, and associated comorbidities8.

Methods

Patient’s recruitment

Patients were collected through data sharing among Epilepsy and Genetic Centers in Europe and the United States. Data were included and categorized in a common database stored at the Danish Epilepsy Centre. Grouping of clinical data for this series was facilitated by GeneMatcher63. All patients were clinically evaluated by neuropediatricians, neurologists and clinical geneticists at their respective tertiary healthcare centers. Patients underwent clinically indicated evaluations, including detailed clinical history and physical examinations, genetic testing, EEG, and MRI. Available EEG recordings (either during wakefulness and sleep) and brain MRIs were obtained and reviewed for all patients. Brain MRIs were reviewed and visually analyzed by the same neuroradiologist (CGM) according to standard clinical practice. Various MRI protocols were used, which were of varying field strengths, slice thicknesses, and image qualities (3 T DICOM format to 6-mm slice thickness; hard copy film photos at 1.5 T). Seizures and, where possible, epilepsy syndromes were classified according to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification proposals7,64. Inconsistencies and discrepancies between reported clinical and diagnostic data were solved by seeking further information from referring physicians.

Molecular genetic analysis

All CELSR1 variants were provided through diagnostic laboratories where they have been identified as part of standard clinical formal diagnostic work-up in patients with epilepsy, cognitive impairment, and/or cortical malformations. We received the results as written reports of the genetic analyses, including the precise variant positions and their ACMG classifications. We did not review the raw exome or Sanger sequencing data; only information regarding the specific variants was provided. The pathogenicity of the genetic variants was classified according to ACMG guidelines65. Only class III-V variants are reported here. Class III variants are defined as “variants of unknown clinical significance”, class IV as “likely pathogenic” and class V as “pathogenic” variants. Included in this evaluation were database searches in NCBI PubMed, Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD 2024.1), the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD, release 4.1.0), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), dbSNP(155), ClinVar, and PER viewer [PER.BROADINSTITUTE.ORG/]. To fulfill our filter criteria, the population allele frequency of the variants should be lower than 1% based on the frequencies given in the current version of public variant databases gnomAD and ExAC, and the variants should be absent in the homozygous state from gnomAD and ExAC. In silico evaluation using SIFT, PolyPhen2, MutationTaster, and CADD, was performed to predict the effect of variants on protein function and the evolutionary conservation of the amino acid at the specific position of interest.

Bioinformatic analysis and protein modeling

The SMART SERVER [SMART.EMBL-HEIDELBERG.DE/] was used for assessment of the functional domains of CELSR1. The structure of each functional domain was obtained individually by performing analysis for structural homology using HHPRED66 [TOOLKIT.TUEBINGEN.MPG.DE], PHYRE267 [WWW.SBG.BIO.IC.AC.UK/PHYRE2], I-TASSER68 [ZHANGLAB.CCMB.MED.UMICH.EDU/I-TASSER/], or RAPTORX69 [RAPTORX.UCHICAGO.EDU/], SWISS-MODEL70 [SWISSMODEL.EXPASY.ORG/INTERACTIVE]. When two or more modelers predicted a model, this was selected based on the highest template-model score, if additionally supported by sequence similarity based on multiple sequence alignment (MSA) with an identity above 30% and functional homology of the template. Templates with a resolution below 4.5 Å and an R value below 0.25 was selected. For all tools, standard settings were used except for Phyre2, for which intensive mode was utilized. Models were retrieved from RCSB PDB [WWW.RCSB.ORG]. Retrieved model sequences were aligned to CELSR1 RefSeq NP_055061.1 using MUSCLE.

Mutant mice

The Celsr1 KO mice were described in Ravni et al.31 and Boucherie et al.36. The experiments were carried out on both males and females without any distinction of the gender.

Immunohistochemistry

We used 12-μm-thick cryosections and 50-μm-thick vibratome slices from postnatal brains fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Sections were blocked in PBS supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 3% bovine serum albumin and incubated with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-GFAP (Millipore, Cat. N° AB5804, 1/1000), mouse anti-Tag1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Cat. N° 4D7, 1/40), rat anti-BrdU (Serotec Cat. N° MCA2060GA, 1/100), Rabbit anti-Cux1 (Proteintech Cat. N° 11733-1-AP, 1/1000), rabbit anti-Doublecortin (Dcx, Cell signaling Cat. N° 4604, 1/800). Different AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, 1:800) were used. After immunohistochemistry, the sections were incubated with DAPI (Sigma D9564 100 μM) for 5 min and mounted with Mowiol.

Histology

For histological examination, 8-µm-thick paraffin sections were deparaffinized, hydrated, and incubated with Cresyl Echt Violet (0.1% in distilled water) for 5 min to assess cell density and cortical architectonics, or with Luxol Fast Blue solution (0.1% in 95% ethanol with 0.5% acetic acid) for 24 h at 60 °C to assess the myelin content and axonal tract integrity. The sections were rinsed in deionized water and differentiated in 70% ethanol (Cresyl violet), or 0.05% lithium carbonate solution, followed by 70% ethanol (Luxol Fast Blue). Finally, the sections were dehydrated in an ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and mounted with DPX.

DiI tracing

DiI crystals (D3911, Molecular Probes) were implanted in target areas (cortical layers 2–3) of PFA-fixed brains using tungsten needles. Blocks were incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 4 weeks and sectioned using a vibratome. About 150-µm-thick sections were counterstained with DAPI (0.25 µg/ml) were mounted with Mowiol medium, and examined under epifluorescence microscopy with a rhodamine filter.

In situ hybridization

Total RNA was extracted from normal newborn mouse brains using a RNeasy kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To produce the riboprobe, the first strand cDNA was synthesized from 10 μg of total RNA using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). cDNA of the Celsr1 genes were amplified by RT-PCR using the following primers: forward: 5’-CCACCCCTGAAATCTGACC-3’, reverse 5’-CACTCTGTATCCTTGCCATCC-3’. In situ hybridization (ISH) was carried out with [alpha-P33]UTP-radiolabelled riboprobe. Briefly, cryostat sections were treated with 1 lg⁄mL proteinase K in 0.1 M Tris, pH 8–10 mm EDTA, rinsed in DEPC-treated water, and acetylated for 10 min in 0.25 M acetic anhydride and 0.1 M triethanolamine solution. Slides were incubated over night at 55–58 °C in a humid chamber with denatured probes (1–5.106 dpm⁄slide) in hybridization solution [50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 0.3 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, Denhardt’s solution (1x), 0.6 mg⁄mL yeast tRNA, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)]. Following hybridization, slides were washed for 30 min at 65 °C in 50% formamide, 2x standard sodium citrate (SSC) solution, rinsed in 2x SSC, and treated for 1 h at 37 °C with 20 lg⁄mL RNAseA in NTE buffer (0.5 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, and 5 mM EDTA). Slides were finally washed in 2x SSC at 60 °C for 1 h and in 0.2x SSC at 65–68 °C for 2 h to achieve high stringency and exposed to Kodak BIOMAX-maximum resolution films.

BrdU injection and quantification

To label dividing cells, BrdU (50 mg/kg body weight) was injected into pregnant females at embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5), and brains were collected at birth (P0). For postnatal neurogenesis experiments, Celsr1 KO and control littermates (3 months old mice), were subjected to intraperitoneal injection of BrdU for three consecutive days and euthanized 9 days after the last injection. For BrdU staining, cryosections and vibratome sections were pretreated with 2 N HCL for 30 min, followed by a 10 min incubation with borate buffer and immunodetection using primary antibody mouse rat anti-BrdU (Serotec Cat. N° MCA2060GA, 1/100). For BrdU quantification in the SVZ of adult mice, four sections were selected at rostral and caudal levels for each animal (n = 3 animals per genotype). BrdU-positive cells were quantified manually using ImageJ software in an area of 600,000 µm2, and values were normalized per mm2. Statistical analysis and graphs were constructed using Prism 9 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) software. The exact sample size is specified in the figure legends. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). We performed a Shapiro–Wilk test to evaluate the distribution of the data. We then used a two-tailed Student’s t-test since the data followed a normal distribution (n.s. not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

Pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-mediated kindling

For PTZ-induced sensitization, Celsr1 KO and control littermates (n = 10 per genotype) were injected intraperitoneally with 35 mg/kg of PTZ and visually monitored for 30 min. Their behavior was scored and grouped into seven categories: (0) normal behavior; (1) immobilization, lying on belly; (2) head nodding, facial, forelimb, or hindlimb myoclonus; (3) continuous whole-body myoclonus, myoclonic jerks, tail held up stiffly; (4) rearing, tonic seizure, falling down on its side; (5) tonic-clonic seizure, falling down on the back, wild rushing and jumping; and (6) death.

Microscopic imaging analyses

High-resolution images (1024 × 1024 pixels) were captured with a digital camera coupled with an inverted Zeiss Axio Observer microscope or in a Laser Scanning confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview FV1000) using the ZEN microscopy software and the FluoView FV1000 Software, respectively. Color images were obtained using optical microscopy (ZEISS AxiosKop). Images were processed using ImageJ software, and figures were prepared using Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator CC 2019, a software package. All the figures containing microscopy images were prepared following the image integrity guidelines from Nature Portfolio.

Ethics

The study was performed in accordance with ethical principles for medical research outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All relevant approvals from the local ethics committees of the participating institutions were obtained. Specifically, for patients 1, 2, and 4, ethics approval was obtained under number SJ-91 from the Zealand region of Denmark; for patient 3, ethics approval was obtained under number 29/2016, from the Bioethics Committee, Institute of Mother and Child, Warsaw, Poland; for patients 5 and 6, ethics approval was obtained under number 2025P013828 from Emory University; for patient 7 ethics approval was obtained under numbers 259/T-2 and 287/M-15 from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu. Informed consent to publish identifying information (including three or more potential identifiers) was obtained from all patients’ guardians, and permission to publish in an open-access journal was granted. Written informed consent to publish a photograph of the participant in an open-access journal was obtained from the patient's guardians. Guardians reviewed and approved the final version of the figure containing the photograph prior to publication.

The Celsr1 KO mice were maintained on a mixed genetic background of 129, C57BL/6 and CD1. They were housed on a 12 h light/dark cycle with lights on from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. The room temperature was maintained at 22 ± 2 °C and the relative humidity at 55 ± 10%. Cages were changed twice a week, and new nesting material was provided once a week. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized with carbon dioxide. All the procedures were carried out in accordance with European Guidelines and approved by the animal ethics committee of the Université Catholique de Louvain under agreement number 2019/UCL/MD/006.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

In our study, sequencing has been performed in routine diagnostic labs or genetic testing companies worldwide. The results are based on previously existing data. All data were stored in the electronic health records and will be accessible for up to 10 years following publication. The results of each patient’s data are available on request to one of the authors listed below. For Pt. #1, #2, #4: EEG, MRI and genetic analysis are stored in the Danish Epilepsy Center, Dianalund, Denmark. For access, please contact GR, guru@filadelfia.dk. For Pt. #3: EEG, MRI, photo and genetic analysis are stored in the Department of Medical Genetics, Institute of Mother and Child, Warsaw, Poland. For access, please contact PG, pawel.gawlinski@imid.med.pl. For Pt. #5 and #6: Genetic analysis is stored at GeneDx. MRI of pt. #6 is stored at the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Radiology Department. For access, please contact RSR, rossana.sanchez@emory.edu. For Pt. #7: MRI, genetic analysis, and muscle biopsy are stored in Tartu University Hospital, Estonia. For access, please contact K.Õ., Katrin.ounap@kliinikum.ee. Source data of Figs. 6g, 7h, k are provided in the Source Data File. We used the following PDB structures for the in silico modeling: 3POY, 4DLQ, 6BXZ, 6E6B, 7SF7, 7SZ8, and 8D40. All variants analyzed in this study have been deposited in ClinVar. The accession numbers and direct links are provided below: p.Ala2486Pro, accession code SCV006104285 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/4073566/?oq=SCV006104285&m=NM_001378328.1(CELSR1):c.7456 G%3EC%20(p.Ala2486Pro)], ClinVar Variation ID 4073566 p.Val2338Ile, accession code SCV006104284 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/3490069/?oq=SCV006104284&m=NM_001378328.1(CELSR1):c.7012 G%3EA%20(p.Val2338Ile)], ClinVar Variation ID 3490069 p.Leu1479His, accession code SCV006104282 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/1315700/?oq=SCV006104282&m=NM_001378328.1(CELSR1):c.4436 T%3EA%20(p.Leu1479His)], ClinVar Variation ID 1315700 p.Thr1472Ser, accession code SCV006104281 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/986386/?oq=SCV006104281&m=NM_001378328.1(CELSR1):c.4415 C%3EG%20(p.Thr1472Ser)], ClinVar Variation ID 986386 p.Asp1201Asn, accession code SCV006104279 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/1315692/?oq=SCV006104279&m=NM_001378328.1(CELSR1):c.3601 G%3EA%20(p.Asp1201Asn)], ClinVar Variation ID 1315692 p.Leu979Phe, accession code SCV006104258 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/4073567/?oq=SCV006104258&m=NM_001378328.1(CELSR1):c.2935 C%3ET%20(p.Leu979Phe)], ClinVar Variation ID 4073567 p.Val673Ala, accession code SCV006104257 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/4073568/?oq=SCV006104257&m=NM_001378328.1(CELSR1):c.2018T%3EC%20(p.Val673Ala)], ClinVar Variation ID 4073568 p.Glu404Lys, accession code SCV006104241 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/986390/?oq=SCV006104241&m=NM_001378328.1(CELSR1):c.1210 G%3EA%20(p.Glu404Lys)], ClinVar Variation ID 986390. Source Data are provided with this article. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Moeschler, J. B., Shevell, M. & Committee on Genetics. Comprehensive evaluation of the child with intellectual disability or global developmental delays. Pediatrics 134, e903–e918 (2014).

Reiss, A. L. Childhood developmental disorders: an academic and clinical convergence point for psychiatry, neurology, psychology and pediatrics. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 50, 87–98 (2009).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (AMA, 2013).

Mercadante, M. T., Evans-Lacko, S. & Paula, C. S. Perspectives of intellectual disability in Latin American countries: epidemiology, policy, and services for children and adults. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 22, 469–474 (2009).

Van Bokhoven, H. Genetic and epigenetic networks in intellectual disabilities. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 81–104 (2011).

Wu, R. et al. Phenotypic and genetic analysis of children with unexplained neurodevelopmental delay and neurodevelopmental comorbidities in a Chinese cohort using trio-based whole-exome sequencing. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 19, 205 (2024).

Zuberi, S. M. et al. ILAE classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in neonates and infants: position statement by the ILAE task force on nosology and definitions. Epilepsia 63, 1349–1397 (2022).

McTague, A., Howell, K. B., Cross, J. H., Kurian, M. A. & Scheffer, I. E. The genetic landscape of the epileptic encephalopathies of infancy and childhood. Lancet Neurol. 15, 304–316 (2016).

Rubboli, G., Gardella, E., Cantalupo, G. & Tassinari, C. A. Encephalopathy related to status epilepticus during slow sleep (ESES). Pathophysiological insights and nosological considerations. Epilepsy Behav. 140, 109105 (2023).

Kochinke, K. et al. Systematic phenomics analysis deconvolutes genes mutated in intellectual disability into biologically coherent modules. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 149–164 (2016).

Hadjantonakis, A. K. et al. Celsr1, a neural-specific gene encoding an unusual seven-pass transmembrane receptor, maps to mouse chromosome 15 and human chromosome 22qter. Genomics 45, 97–104 (1997).

Hadjantonakis, A. K., Formstone, C. J. & Little, P. F. mCelsr1 is an evolutionarily conserved seven-pass transmembrane receptor and is expressed during mouse embryonic development. Mech. Dev. 78, 91–95 (1998).

Wang, Y. & Nathans, J. Tissue/planar cell polarity in vertebrates: new insights and new questions. Development 134, 647–658 (2007).

Tissir, F. & Goffinet, A. M. Shaping the nervous system: role of the core planar cell polarity genes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 525–535 (2013).

Devenport, D. The cell biology of planar cell polarity. J. Cell Biol. 207, 171–179 (2014).

Butler, M. T. & Wallingford, J. B. Planar cell polarity in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 375–388 (2017).

Boutin, C., Goffinet, A. M. & Tissir, F. Celsr1-3 cadherins in PCP and brain development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 101, 161–183 (2012).

Formstone, C. J. & Little, P. F. The flamingo-related mouse Celsr family (Celsr1-3) genes exhibit distinct patterns of expression during embryonic development. Mech. Dev. 109, 91–94 (2001).

Shima, Y. et al. Differential expression of the seven-pass transmembrane cadherin genes Celsr1-3 and distribution of the Celsr2 protein during mouse development. Dev. Dyn. 223, 321–332 (2002).

Tissir, F., De-Backer, O., Goffinet, A. M. & Lambert de Rouvroit, C. Developmental expression profiles of Celsr (Flamingo) genes in the mouse. Mech. Dev. 112, 157–160 (2002).

Yates, L. L. et al. The PCP genes Celsr1 and Vangl2 are required for normal lung branching morphogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2251–2267 (2010).

Tatin, F. et al. Planar cell polarity protein Celsr1 regulates endothelial adherens junctions and directed cell rearrangements during valve morphogenesis. Dev. Cell 26, 31–44 (2013).

Curtin, J. A. et al. Mutation of Celsr1 disrupts planar polarity of inner ear hair cells and causes severe neural tube defects in the mouse. Curr Biol 13, 1129–1133 (2003).

Duncan, J. S. Celsr1 coordinates the planar polarity of vestibular hair cells during inner ear development. Dev. Biol. 423, 126–137 (2017).

Qiao, X. et al. Genetic analysis of rare coding mutations of CELSR1-3 in congenital heart and neural tube defects in Chinese people. Clin. Sci. 130, 2329–2340 (2016).

Brzóska, H. Ł et al. Planar cell polarity genes Celsr1 and Vangl2 are necessary for kidney growth, differentiation, and rostrocaudal patterning. Kidney Int. 90, 1274–1284 (2016).

Gonzalez-Garay, M. L. et al. A novel mutation in CELSR1 is associated with hereditary lymphedema. Vasc. Cell 8, 1 (2016).

Erickson, R. P. et al. Sex-limited penetrance of lymphedema to females with CELSR1 haploinsufficiency: a second family. Clin. Genet. 96, 478–482 (2019).

Maltese, P. E. et al. Increasing evidence of hereditary lymphedema caused by CELSR1 loss-of-function variants. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 179, 1718–1724 (2019).

Boutin, C. et al. A dual role for planar cell polarity genes in ciliated cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E3129–E3138 (2014).

Ravni, A., Qu, Y., Goffinet, A. M. & Tissir, F. Planar cell polarity cadherin Celsr1 regulates skin hair patterning in the mouse. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 2507–2509 (2009).

Allache, R., De Marco, P., Merello, E., Capra, V. & Kibar, Z. Role of the planar cell polarity gene CELSR1 in neural tube defects and caudal agenesis. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 94, 176–181 (2012).

Robinson, A. et al. Mutations in the planar cell polarity genes CELSR1 and SCRIB are associated with the severe neural tube defect craniorachischisis. Hum. Mutat. 33, 440–447 (2012).

Lei, Y. et al. Identification of novel CELSR1 mutations in spina bifida. PLoS ONE 9, e92207 (2014).

Tian, T. et al. Somatic mutations in planar cell polarity genes in neural tissue from human fetuses with neural tube defects. Hum. Genet. 139, 1299–1314 (2020).

Boucherie, C. et al. Neural progenitor fate decision defects, cortical hypoplasia and behavioral impairment in Celsr1-deficient mice. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 723–734 (2018).

Qu, Y. et al. Atypical cadherins Celsr1-3 differentially regulate migration of facial branchiomotor neurons in mice. J. Neurosci. 30, 9392–9401 (2010).

Balagura, G. et al. Clinical spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlations in PRRT2 Italian patients. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 28, 193–197 (2020).

Barnerias, C. et al. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency: four neurological phenotypes with differing pathogenesis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 52, e1–e9 (2010).

DeBrosse, S. D. et al. Spectrum of neurological and survival outcomes in pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) deficiency: lack of correlation with genotype. Mol. Genet. Metab. 107, 394–402 (2012).

Wang, D., Li, J., Wang, Y. & Wang, E. A comparison on predicting functional impact of genomic variants. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 4, lqab122 (2022).

Gunning, A. C. et al. Assessing performance of pathogenicity predictors using clinically relevant variant datasets. J. Med. Genet. 58, 547–555 (2021).

Brasch, J. et al. Visualization of clustered protocadherin neuronal self-recognition complexes. Nature 569, 280–283 (2019).

De-la-Torre, P., Choudhary, D., Araya-Secchi, R., Narui, Y. & Sotomayor, M. A mechanically weak extracellular membrane-adjacent domain induces dimerization of protocadherin-15. Biophys. J. 115, 2368–2385 (2018).

Miller, M. T. et al. The crystal structure of the α-neurexin-1 extracellular region reveals a hinge point for mediating synaptic adhesion and function. Structure 19, 767–778 (2011).

Araç, D. et al. A novel evolutionarily conserved domain of cell-adhesion GPCRs mediates autoproteolysis. EMBO J. 31, 1364–1378 (2012).

Barros-Álvarez, X. et al. The tethered peptide activation mechanism of adhesion GPCRs. Nature 604, 757–762 (2022).

Bandekar, S. J. et al. Structural basis for regulation of CELSR1 by a compact module in its extracellular region. Nat. Commun. 16, 3972 (2025).

Shu, T. & Richards, L. J. Cortical axon guidance by the glial wedge during the development of the corpus callosum. J. Neurosci. 21, 2749–2758 (2001).

Parrini, E., Conti, V., Dobyns, W. B. & Guerrini, R. Genetic basis of brain malformations. Mol. Syndromol. 7, 220–233 (2016).

Di Donato, N. et al. Lissencephaly: expanded imaging and clinical classification. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 173, 1473–1488 (2017).

Di Donato, N. et al. Analysis of 17 genes detects mutations in 81% of 811 patients with lissencephaly. Genet. Med. 20, 1354–1364 (2018).

Guerrini, R. & Dobyns, W. B. Malformations of cortical development: clinical features and genetic causes. Lancet Neurol. 13, 710–726 (2014).

Oegema, R. et al. International consensus recommendations on the diagnostic work-up for malformations of cortical development. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 16, 618–635 (2020).

Striano, S. et al. Eyelid myoclonia with absences (Jeavons syndrome): a well-defined idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndrome or a spectrum of photosensitive conditions?. Epilepsia 50, 15–19 (2009).

Palumbo, P. et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of an emerging chromosome 22q13.31 microdeletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 176, 391–398 (2018).

Chen, Z. et al. CELSR1 variants are associated with partial epilepsy of childhood. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 189, 247–256 (2022).

Bédard, A. & Parent, A. Evidence of newly generated neurons in the human olfactory bulb. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 151, 159–168 (2004).

Sanai, N. et al. Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature 427, 740–744 (2004).

Sanai, N. et al. Corridors of migrating neurons in the human brain and their decline during infancy. Nature 478, 382–386 (2011).

Tissir, F. & Goffinet, A. M. Planar cell polarity signaling in neural development. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20, 572–577 (2010).

Wallmeier, J. et al. De novo mutations in FOXJ1 result in a motile ciliopathy with hydrocephalus and randomization of left/right body asymmetry. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 105, 1030–1039 (2019).

Sobreira, N., Schiettecatte, F., Valle, D. & Hamosh, A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum. Mutat. 36, 928–930 (2015).

Fisher, R. S. et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the international league against epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 58, 522–530 (2017).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 17, 405–424 (2015).

Zimmermann, L. et al. A completely reimplemented MPI bioinformatics toolkit with a new HHpred server at its core. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 2237–2243 (2018).

Kelley, L. A., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. M., Wass, M. N. & Sternberg, M. J. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 (2015).

Zheng, W. et al. Folding non-homologous proteins by coupling deep-learning contact maps with I-TASSER assembly simulations. Cell Rep. Methods 1, 100014 (2021).

Wang, S., Li, W., Liu, S. & Xu, J. RaptorX-Property: a web server for protein structure property prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W430–W435 (2016).

Waterhouse, A. et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–W303 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the following grants: FNRS PDR T00075.15, FNRS PDR T0236.20, FNRS-FWO EOS 30913351, Fondation Médicale Reine Elisabeth, and Fondation JED-Belgique to F.T. Estonian Research Council grant PRG471 to K.Õ. National Human Genome Research Institute, with supplemental funding provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) program and the National Eye Institute to the Broad Institute Center for Mendelian Genomics (UM1HG008900).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.R., F.T., and R.S.M. conceived and designed the study. K.B., N.R.-R., G.C., M.A., and F.T. acquired, analyzed and interpreted the results on animal data. Drafting and/or revising manuscript: C.M.B., G.R., and F.T. oversaw all aspects of the project, drafted and revised the paper. C.M.B., P.G., M.D., W.W., M. B.-F., S.C., M.R., G.L., E.G., B.J., T.S.M., T.B.H., R.S.R., E.E.B., K.Õ., P.I., and M.H.W. acquired and analyzed human data. C.M.B., C.G.M., A.B., T.B.H., C.D.F., and E.G. interpreted the results on human data. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript. C.M.B., K.B., N.R.R., and F.T. were responsible for figures and videos. F.T. was responsible for funding acquisition. G.R., F.T., and K.B. collaboratively handled the writing, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mitsuhiro Kato, Anna Jansen, Takashi Ishida and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonardi, C.M., Møller, R.S., Ruiz-Reig, N. et al. Biallelic variants in CELSR1 cause brain malformations, neurodevelopmental disorders and epilepsy in humans. Nat Commun 17, 862 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67576-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67576-w