Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is a validated therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes (T2D), but current FDA-approved agonists are limited by adverse effects. SR10171, a non-covalent partial inverse agonist with modest binding potency, improves insulin sensitivity in mice without bone loss or marrow adiposity. Here, we characterize a series of SR10171 analogs to define structure-function relationships using biochemical assays, hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX), and computational modeling. Analogs featuring flipped indole scaffolds with N-alkyl substitutions exhibited 10- to 100-fold enhanced binding to PPARγ while retaining inverse agonist activity. HDX and molecular dynamic simulations revealed that ligand-induced dynamics within ligand-binding pocket and AF2 domain correlate with enhanced receptor binding and differential repression. Lead analogs restored receptor activity in loss-of-function PPARγ variants and improved insulin sensitivity in adipocytes from a diabetic patient. These findings elucidate mechanisms of non-covalent PPARγ modulation establishing a framework for developing safer, next-generation insulin sensitizers for metabolic disease therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insulin resistance is a defining feature of Type 2 diabetes (T2D) and contributes to a broad spectrum of metabolic disorders, including metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, cardiovascular disease and obesity. The pathogenesis of T2D involves progressive insulin resistance, which initially provokes compensatory hyperinsulinemia, followed by pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and eventual chronic hyperglycemia1,2,3. This metabolic dysregulation substantially increases the risk of severe comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, renal failure, osteoporosis, and stroke4,5,6,7. Despite the availability of insulin-sensitizing agents, their clinical utility is limited by adverse effects, including increased risk of bone loss8 and heart failure9, and reduced efficacy in patients with coexisting conditions like chronic kidney disease (CKD)7. Metformin, the first-line treatment for T2D, is often insufficient as monotherapy and contraindicated in patients with renal impairment. Thiazolidinediones (TZDs), such as rosiglitazone (Rosi) or pioglitazone, target the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) as agonists to improve insulin sensitivity, but are associated with plasma volume expansion, weight gain, bone loss and increased cardiovascular risk10,11,12, and, in rare cases, increased bladder cancer risk13. These limitations underscore the need for alternative PPARγ-targeted therapies that enhance insulin sensitivity while minimizing adverse effects.

PPARγ, which forms a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor alpha, regulates gene networks involved in adipogenesis, lipid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity. Dysregulated PPARγ signaling is implicated in insulin resistance, obesity, and T2D progression1,10,11,12,14,15,16,17. PPARγ exists as two isoforms, PPARγ1 and PPARγ2, that differ by 28 N-terminal amino acids; PPARγ1 is broadly expressed, while PPARγ2 is adipocyte-specific10,17,18. However, both isoforms share a modular architecture comprising an N-terminal activation function-1 domain, a DNA-binding domain, a hinge region, and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) containing the activation function-2 (AF2) surface. Ligand binding to the LBD induces conformational change, particularly at the AF2 surface, to allosterically modulate coactivator and corepressor recruitment and transcriptional activity. As such, the LBD is the principal target for therapeutic modulation of PPARγ activity.

PPARγ ligands, like that observed with other nuclear receptors such as RORγ19,20,21,22, fall into three categories: agonists that enhance basal receptor activity, antagonists that neutralize basal activity by blocking the effects of endogenous or exogenous ligands, and inverse agonists that suppress basal receptor activity. We previously reported that the insulin sensitizing efficacy of TZDs and the partial agonist MRL24, is correlated with the inhibition of serine 273 phosphorylation (pS273) on PPARγ, a CDK5-mediated post-translational modification that represses genes linked to insulin sensitivity23. This finding inspired the development of PPARγ modulators that preserve insulin-sensitizing properties by blocking pS273 while minimizing agonism-associated adverse effects. Among these, non-covalent antagonists and inverse agonists emerged as a promising yet underexplored class, distinct from both agonists and covalent ligands. We previously described SR1664, a non-covalent antagonist with an improved therapeutic index but poor pharmacokinetics24. Building on this scaffold, we conducted structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies25 and developed a series of compounds, including SR11023 (antagonist)26,27, SR10171 (partial inverse agonist)27,28, and SR10221 (full inverse agonist)29, each exhibiting improved drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic properties24,30. Despite their structural similarity, and enhanced binding and repression potency, only antagonists and partial inverse agonists demonstrate antidiabetic efficacy (Supplementary Fig. 1)24,28,30. For example, SR10171 improved insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice while preventing weight gain and bone loss28, suggesting functional differences between partial and full inverse agonists. The bone-protective effect may partly reflect modest PPARα activation28,30,31,32,33. PPARα is expressed in osteocytes and regulates bone microenvironment and systemic energy metabolism34, promoting osteocyte health and contributing to anabolic bone remodeling. When combined with partial PPARγ inverse agonism that enhances insulin sensitization, this dual modulation may underlie the favorable metabolic and skeletal outcomes observed with SR10171. However, SR10171’s modest binding affinity limits its pharmacological potential.

We hypothesized that strategic modifications to the SR10171 scaffold could enhance binding affinity, enabling lower oral doses and improved in vivo efficacy. Yet the molecular mechanisms underlying non-covalent inverse agonism of PPARγ remain unclear. Agonists stabilize the AF2 surface via hydrogen bonding with Helix 12 (H12), promoting co-activator recruitment and an active conformation26,35,36,37. Covalent inverse agonists, by contrast, reposition H12 into the ligand-binding pocket (LBP), favoring corepressor binding and a repressive conformation37,38,39. Non-covalent inverse agonists are proposed to position H12 at the front of H3, disfavoring coactivator binding27, and in the presence of corepressors, may reorient to the back of H3, leading to H12 disorder29,37. These mechanisms have largely been inferred from co-crystal structures of PPARγ-LBD bound to SR1022129, and the structural basis distinguishing partial from full inverse agonism remains undefined. Notably, SR10171 and SR10221, despite the chemical structural similarity, exhibit divergent pharmacological profiles, underscoring the need for deeper mechanistic insight to guide rational design of next-generation non-covalent inverse agonists.

In this study, we present structure-guided optimization of the SR10171 scaffold aimed at enhancing its binding affinity and therapeutic efficacy. We synthesized and characterized a series of SR10171 analogs featuring an inverted indole nitrogen orientation, a modification that unexpectedly improved receptor engagement. To elucidate the structure-function relationships underlying non-covalent inverse agonism, we employed a multidisciplinary approach combining analog synthesis, in vitro and in cellulo biochemical assays, hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS), computational modeling, molecular dynamics simulations (MDS), and functional evaluation of insulin sensitizing activity in murine and human adipocytes. Together, these findings advance the mechanistic understanding of PPARγ modulation and lay the foundation for developing safer and more effective next-generation insulin sensitizers.

Results

Biochemical analysis of SR10171 analogs

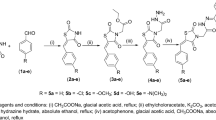

To further investigate structure activity relationships of the SR10171 and SR10221 series of PPARγ inverse agonists, the flipped-indole versions of these leads were synthesized (Fig. 1A). Resulting analogs were tested in a LanthaScreen™ TR-FRET-based competitive binding assay, where Rosi and SR10221 consistently demonstrated approximately threefold lower Kd values compared to SR10171 (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B and Supplementary Table 1). Compounds 1 and 2, the flipped indole analogs of SR10171 and SR10221, respectively, showed approximately 1.5-fold and five-fold improvements in binding affinity relative to their parental compounds, indicating that this scaffold modification enhances ligand binding to PPARγ. To determine whether the flipped indole scaffold retains key functional features of SR10171 (i.e., potent PPARγ inverse agonism while maintaining modest PPARα agonism23,30), these analogs were evaluated in a Gal4-LBD:UAS-luciferase reporter co-transfection assay system. Gal4-VP16 was first included to assess cytotoxicity. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2C, the flipped SR10171 scaffold is not toxic to cells at concentrations below 10 μΜ. Testing of these compounds on Gal4-PPARγ and Gal4-PPARα reveal that altering the indole nitrogen orientation slightly increasing agonism of PPARγ (Supplementary Fig. 2D) while partially reduced PPARα activation (Supplementary Fig. 2E) in a dose-dependent fashion relative to their parental compounds. As expected, compound-mediated agonism of PPARδ was not observed in the Gal4-PPARδ assay apart from the control compounds GW0742 (a potent PPARδ agonist) and GW7647 (a dual potent PPARα agonist and weak PPARδ agonist), suggesting that the SR10171 scaffold with the flipped indole orientation has minimal effects on PPARδ activity (Supplementary Fig. 2F). These results support the use of this indole configuration to develop third generation non-covalent PPARγ inverse agonists with improved binding affinity to PPARγ.

A SAR optimization of SR10171. R = H or t-Bu; R1 = H or Me; R2 = Me, Et, i-Bu, CH2-cyclopropyl, or CH2-cyclobutyl; R3 = H or Me, R4 = H, F, or Cl; X = Y = Me or H. B PCA analysis of SR10171 analogs based on their regiochemical features. The compounds that proceeded with further evaluation are bolded. C LanthaScreen binding assay with PPARγ-LBD. Data represent the mean ± SEM from ≥2 biological replicates, each measured in technical triplicate. Box-and-whisker plots showing fold change in D PPARγ-LBD and E PPARα-LBD activity in the presence of 1 μΜ compounds relative to DMSO in the Gal4::UAS reporter assay. Boxes denote IQR, whiskers indicate min–max, and the line shows the median response. Each compound was tested in at least three biological replicates, each included at least four technical replicates. The statistical significance is over SR10171. F Heatmap clustering analysis summarizing the biochemical profiles of the compounds. Colors represent compound-induced activity with intensities normalized to the maximum response of the positive control in each assay (red: enhanced, white: neutral, blue: reduced). AS: AlphaScreen; pS273: in vitro phosphorylation assays. [compound]:concentration starting from 10 μΜ (30 μΜ for Gal4-VP16::Luc) with threefold serial dilutions. *p ≤ 0.05, ****p ≤ 0.0001. One-way ANOVA corrected by Tukey’s multiple comparison.

To expand the SAR, an additional 95 analogs of Compound 1 were synthesized modifying different portions of the molecule as highlighted in Fig. 1A and evaluated (Supplementary Tables 1–3). To assess their structural diversity, molecular fingerprints were generated using RDKit (https://www.rdkit.org), capturing circular substructures up to two bonds from each atom to encode topological features, including atom types, connectivity, and local chemical environment. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)40 of these fingerprints revealed four distinct compound clusters (Fig. 1B). Each cluster represents a group of analogs with similar molecular environments and potentially shared pharmacological properties, despite subtle differences in substitution patterns (Fig. 1A). All analogs were tested in a microsomal stability assay (human and murine) to exclude compounds with high intrinsic clearance. Functional profiling of using LanthaScreen and Gal4-LBD::UAS-luciferase reporter co-transfection assays was then performed to eliminate low-affinity binders and compounds exhibiting robust PPARγ agonism as described below.

Functional characterization of SR10171 analogs

Twenty-five compounds, including Compound 1 serving as a control compound, were selected for further evaluation (Supplementary Tables 1 and 3). Consistent with results for Compounds 1 and 2, these analogs exhibited lower IC50 values than SR10171 in the LanthaScreen, ranging from 10 to 500-fold, suggesting that the flipped indole orientation greatly enhances ligand binding affinity to PPARγ (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Table 1). Comparing reporter activity in Gal4 assays at 1 μΜ, Compounds 1, 2, 3, and 15 showed a slight but non-significant increase on PPARγ agonism compared to SR10171 (Fig. 1D), whereas SR10171 resulted in ~14% of PPARγ activation compared to that observed with Rosi. Compounds 3 and 4 showed similar PPARα agonism to SR10171 and SR10221 (Fig. 1E), whereas SR10171 led to ~45% activation of PPRAα compared to that observed with GW7647 treatment. As shown in Fig. 1F: Gal4-PPARα panel, the SR10171 analogs differentially enhanced PPARα activity, demonstrating partial PPARα agonism at higher concentrations. While comparing to Rosi (Fig. 1F: Gal4-PPARγ panel), all 25 analogs demonstrated weak or modest PPARγ activity at all concentrations, indicating a lack of PPARγ agonistic activity. As expected, these analogs did not enhance PPARδ activity (Fig. 1F: Gal4-PPARδ panel and Supplementary Fig. 3A). In addition, minimal cytotoxicity was only observed for some analogs at 10 μΜ and above in the Gal4-VP16 assay (Fig. 1F: Gal4-VP16 panel), suggesting that 1 μΜ is a reasonable concentration to evaluate compounds in subsequent in vitro pharmacology experiments. The above results indicate that these analogs target PPARγ with weak agonism of PPARα like that observed with SR10171. Compound 1 was removed after the primary screens due to its higher Kd than Rosi.

The top 24 analogs were tested in the AlphaScreen assay for their ability to alter PPARγ interaction with peptides representative of NR coregulators, including SRC1-2 and NCoR (D2) that are representative of nuclear receptor coactivator 1 and nuclear receptor corepressor 2, respectively. As expected, the PPARγ agonist Rosi enhanced interaction with the coactivator SRC1-2 peptide while decreasing interaction with the corepressor peptide NCoR (D2), while the inverse agonists SR10171, SR10221, and T0070907 had opposing effects to Rosi (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Similarly, all SR10171 analogs decreased SRC1-2 binding and increased NCoR (D2) interaction with PPARγ (Fig. 1F, AS-SRC1 and AS-NCoR) with few exceptions. Prior studies demonstrate that insulin-sensitizing ligands binding to PPARγ reduced CDK5-dependent pS273 within the receptor’s LBD28. Using an in vitro phosphorylation assay, analogs reduced phosphorylation of PPARγ-LBD (Fig. 1F (pS273) and Supplementary Fig. 3C). Collectively, these functional characteristics confirmed the SR10171-like properties of these analogs in modulating PPARγ-LBD dynamics are reflected in transcriptional repression, distinct coregulator interactions, and decreased CDK5-mediated phosphorylation.

To confirm analog activity in the context of full-length (FL) PPARγ, compounds were tested in the following two functional assays. First, a peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE) promoter::reporter assay was used to determine compound inverse agonism efficacy. Second, given the essential role of PPARγ in adipogenesis, a well-established 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell41 model was used to evaluate the impact of SR10171 analogs on fat cell differentiation. Analogs were first tested for cytotoxicity in cells at 1 μΜ concentration for 24-h where all analogs were devoid of activity (Supplementary Fig. 4A). The PPRE::reporter assay revealed that all analogs differentially reduced PPARγ transcriptional activity at 1 μΜ (Fig. 2A). When 3T3-L1 cells were differentiated in the presence of 1 μM of each compound, reduced expression of pro-adipogenic genes, including CEBPA (Supplementary Fig. 4B) and FABP4 (Fig. 2B) was observed as well as a reduction in lipid droplet formation (Fig. 2C, D and Supplementary Fig. 4C) with a few exceptions.

A PPRE reporter activity assays using FL-PPARγ in HEK293T cells. Each compound was tested in at least three biological replicates. Each biological replicate includes five technical replicates. B Fold change in mRNA expression of FABP4 on day 4 post-induction of adipogenesis in L1 cells. Each compound was tested in at least three biological replicates, each measured in technical triplicates. C Fold change in lipid droplet formation, and D representative images of controls on day 10 post-induction of adipogenesis in L1 cells. Each compound was tested in at least three biological replicates, each included four technical replicates. The above assays were performed in the presence of 1 μΜ compounds. Scale bars in 4× and 10× panels represent 500 and 200 μm, respectively. E Heatmap clustering analysis summarizing the PPARγ-directed functional profiles from in vitro and cell-based assays. Colors represent compound-induced activity with intensities normalized to the maximum response of the positive control in each assay (red: enhanced, white: neutral, blue: reduced). AS: AlphaScreen; pS273: in vitro phosphorylation assays. PPRE reporter gene activity assays. CEBPA and FABP4: adipogenic gene expression. [compound]: concentration starting from 10 μΜ (30 μΜ for Gal4-VP16::Luc) with threefold serial dilutions. Data represent the mean ± SEM with statistical significance over DMSO. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. One-way ANOVA corrected by Tukey’s multiple comparison.

Using results from the above assays, hierarchical clustering analysis classified the analogs into three groups based on their pharmacological profile (Fig. 2E). The first group (non-IA, green) clustered with SR10171 and exhibited partial agonism, antagonism, or weak partial inverse agonism on FL-PPARγ. The second group (partial-IA, blue) resulted in higher affinity of PPARγ for the co-repressor peptide (NCoR (D2)) while further repressing FL-PPARγ activity in cell-based assays as compared to SR10171. The third group (full-IA, SR10221-like compounds) blocked both PPARγ-LBD Gal4-UAS and FL-PPARγ PPRE reporter activity, and repressed L1 cell adipogenesis. This clustering analysis reveals how small structural modifications to ligands can distinctly influence the regulatory behavior of PPARγ. To determine if distinct regulation of PPARγ by analogs is driven by binding potency or chemical structure, pairwise correlation analysis was performed across the different assays. This analysis revealed that PPARγ transcription activity significantly correlated to differential preference for coregulator peptide interaction and adipogenesis, but the binding potency (IC50 determined using LanthaScreen) is poorly correlated with functional outcomes (Supplementary Fig. 5). Comparisons of clustering based on structure and functional profiles revealed similar groupings (Fig. 2E), highlighting a clear link between chemical motifs and biochemical properties.

HDX characterization of the conformational dynamics of PPARγ-LBD complexed with inverse agonists

Previous HDX studies of the PPARγ-LBD suggest that two on-exchange timepoints, an early 10 s and late 4 h timepoints, are sufficient to distinguish differential receptor-ligand dynamics26,27,30. Accordingly, a two-timepoint HDX-MS screen was employed to detect perturbations in rapid and sustained protection from solvent exchange modulated by ligand binding42. Heatmap clustering analysis of the screen results revealed that PPARγ-LBD complexes with SR10171 analogs exhibited conformational dynamics similar to those observed with SR10171- and SR10221-bound complexes (Fig. 3A), suggesting broadly conserved receptor-ligand conformations. The 10 s HDX data, representative of highly dynamic solvent exchange events, revealed significant reduction in deuterium uptake was primarily localized to β-sheet 1 (β1), H2b, and H10-12. These regions are situated on the surface of the LBP opposite the dimerization interface. Notably, compounds in the top cluster in the 10 s HDX panel (Fig. 3A), classified as full-IA (purple), showed increased deuterium uptake at H12 (activation helix), suggesting that these full-IAs destabilize H12, promoting an inactive receptor conformation. Conversely, at 4 h, differential protection from deuterium uptake was limited to regions of the receptor that include H2a to β1, H3, and β2–3 to H7. These regions surround the surface of the LBP near the dimerization interface and are likely stabilized by H-bonding and steric shielding by the bound ligand.

A Heatmap clustering analysis summarizing differential deuterium uptake of PPARγ-LBD in the presence of twenty-six PPARγ modulators relative to DMSO at 10 s (10 s) and 4 h (4 h), with the corresponding dendrogram on the left grouping protein-ligand complexes based on their exchange signatures. Each row represents a single PPARγ-LBD:inverse agonist complex, and each column represents a peptide derived from PPARγ. The locations of each peptide in the crystal structure are labeled along the top. B Regions of PPARγ-LBD with significant correlation between HDX-MS dynamics and either PPARγ transcription activity (top) or FABP4 mRNA expression (bottom) were mapped onto the PPARγ-LBD structure (PDB:6C5Q). Colors denote peptides for which the correlation coefficient was significantly non-zero (adjusted p value < 0.05). Representative correlation plots of C PPARγ transcription activity and D FABP4 mRNA expression are shown, with data points colored according to functional classification. Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using Pearson’s correlation test, and p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate method, yielding the adjusted p-value (p) and correlation coefficient (r).

In the HDX dataset, individual peptides are proxies for regions within the folded intact receptor. To identify regions of the receptor LBD that exhibit coupled solvent exchange behavior, covariation analysis was conducted. This analysis suggests that ligand-binding induced LBD dynamics are primarily coordinated within regions spanning H2-H3, H5-H7, and H10-H12 (Supplementary Fig. 6). To help elucidate the mechanism by which compounds modulate PPARγ activity, Pearson correlation analysis was performed with the HDX-MS data and the results from the cell-based assays. This analysis identified 12 peptides whose deuterium uptake significantly correlated (p < 0.05) with the repression of PPARγ transcriptional activity, and 11 peptides correlated with FABP4 expression, a direct PPARγ target gene. Mapping the correlation coefficients onto the PPARγ-LBD structure suggests distinct regional trends (Fig. 3B). There was reduced deuterium uptake in regions of the LBD encompassing H3, particularly the region including FRSVE (Residues 315–319), and the β2/β3 strands with extension towards H7 strongly correlated with enhanced repression of PPARγ activity measured in the PPRE::reporter assay (Fig. 3B, top panel; Fig. 3C). Conversely, the increased deuterium uptake within H12 correlated with increased transcriptional repression. These findings were further supported by correlation analysis of expression levels of FABP4 (Fig. 3B, bottom panel; Fig. 3D) and CEBPA (Supplementary Fig. 7) measured during the early stage of adipogenesis. Collectively, these results demonstrate that stabilization of the LBP coupled with increased flexibility in H12 induced by non-covalent inverse agonists, plays a pivotal role in attenuating PPARγ transcriptional activity.

Integrated computational modeling of ligand-induced PPARγ conformational dynamics

To investigate the binding mechanisms of non-covalent inverse agonists, molecular docking was employed to predict ligand binding poses (Supplementary Table 4), followed by MDS to explore protein-ligand interactions. The resulting complexes were generally stable throughout the simulations according to backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) (Supplementary Fig. 8A). Notably, analogs bearing bulky hydrophobic substitutions on the indole ring exhibited significantly lower total free energies (approximate −70 kcal/mol) compared to SR10171 (approximate −50 kcal/mol), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8B. These findings suggest that such substitutions enhance stabilization of ligand-induced inactive conformation of the receptor LBD. To further dissect the energetic landscape of ligand binding, residue-level free energy distributions were visualized using heatmap clustering analysis (Fig. 4A). Notably, the N-terminal half of H3 exhibited lower free energy values, indicating enhanced stabilization upon ligand binding. This effect was particularly pronounced at the FRSVE motif, which also showed strong protection from deuterium uptake and correlated significantly with PPARγ repression (Fig. 3), implicating R316 and S317 as key interaction hotspots within H3. In contrast, the C-terminal half of H3 displayed higher free energy, suggesting increased flexibility or weaker hydrophobic interactions in this region. These receptor-level structural features align with the ligand-induced conformational dynamics observed in Fig. 3B, collectively highlighting the structural basis of PPARγ repression. Additionally, several residues, including the polar S370 and hydrophobic residues C313, I354, L358, and I369, consistently exhibited low total free energy values (Fig. 4A), underscoring their likely roles in stabilizing the ligand-induced inactive conformation of the PPARγ-LBD in response to non-covalent inverse agonists.

A Heatmap clustering analysis of per-residue MM/PBSA binding energy profiles across twenty-six SR10171 analogs based on their residue interaction profiles. Each row represents a ligand-bound complex, and each column corresponds to a residue within the LBD, annotated with secondary structural elements along the top. Color intensity reflects the total free energy contribution of each residue (blue = favorable, red = unfavorable). Structural overlay of representative binding poses of B SR10171, C SR10221, D Compound 2, and E Compound 23 within the PPARγ-LBD. Dashed lines indicate interatomic distances (Ǻ) between ligand atoms and key residues. F 3D-PCA of the dynamic cross-correlation matrices (DCCMs) derived from MDS. Each point represents a ligand-bound complex, color-coded by the functional classification (green: non-IA, blue: partial-IA, purple: full-IA).

The centroid structure of the top cluster from GROMOS clustering analysis using backbone RMSD43 was extracted as the representative conformation for each ligand-bound PPARγ-LBD complex. The binding pose of SR10171 closely resembled that of SR10221 in the original crystal structure, with the indole core positioned behind H3, forming hydrophobic interactions with R316 (H3), I354 and L358 (H5) (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 9A). The 4-tert-butyl-phenyl moiety engaged additional hydrophobic contacts with AF2 interface residues V318, V321, and V350, while the dimethyl groups and phenyl ring interacted with C313 and I369. These hydrophobic interactions were complemented by potential hydrogen bonds between the amide group of SR10171 and S317 (2.9 Ǻ), and between the acidic tail and S370. While SR10221 exhibits a representative binding pose with a rotated 4-tert-butyl-phenyl group (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 9B), its indole core maintains a similar position within the binding site (Supplementary Fig. 8C). Analysis of Compound 2, a flipped-indole analog of SR10221, reveals a binding pose nearly identical to SR10171 (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. 9C). Notably, this flipped orientation of the indole places the nitrogen atom near the guanidinium group of R316, reducing the distance to 6.7 Å in Compound 2 and further to 5.5 Ǻ in Compound 23 with an N-cyclobutyl substituent (Fig. 4E and Supplementary Fig. 9D). This proximity suggests a potential enhancement of the cation-π interaction between the indole nitrogen and R316, which likely reinforces the polar interaction between the ligand amide and S317, thereby stabilizing the LBP. A similar binding mode is observed for Compound 4, despite the absence of the methyl group on the indole (Supplementary Figs. 8D and 9E). Collectively, these results highlight the role of the alkyl substitution at the indole in enhancing hydrophobic contacts with H5, while the position of the indole nitrogen relative to R316 stabilizes the inactive conformation, likely via cation-π or electrostatic interactions.

To evaluate the conformational dynamics of SR10171 analog-bound LBD complexes during simulations, Dynamic Cross-Correlation Matrices (DCCM) analysis44,45,46,47 was used to representative simulation clusters, followed by PCA40 to delineate dominant modes of conformational variability across the ligand-bound and apo ensemble. As shown in Fig. 4F, full-IAs form a distinct conformational cluster, separated from the apo LBD with minimal overlap. This suggests that this unique conformational state underlies their ability to fully repress PPARγ. In contrast, the non- and partial-IA compounds exhibit a more dispersed distribution in conformational space, overlapping with both the full-IA cluster and the apo LBD. This indicates greater conformational flexibility, which likely correlates with their neutral antagonism or partial inverse agonism profiles.

Validation of structure-function relationships of inverse agonists

To validate the structural basis for inverse agonism (as proposed in Fig. 3B) and assess the therapeutic potential of inverse agonists, five PPARγ mutants (A261E, S273A/D, F310A, F388L, and Y501A) were generated. These residues were selected based on their known implications in LBD stability, ligand-mediated transcriptional regulation, and association with metabolic diseases, including lipodystrophy48,49,50,51,52,53,54 (Fig. 5A). Protein expression level of the mutant receptors was confirmed by immunoblotting and was found to be comparable to that of wild-type (WT) PPARγ, with the exception of the A261E mutant receptor, which exhibited modestly reduced expression (Supplementary Fig. 10A, B). These results demonstrate that all mutant receptors were expressed at levels sufficient for functional characterization using PPRE::reporter assays.

A Structural mapping of disease-relevant mutations within PPARγ-LBD (adapted from PDB:8B8X). PPRE reporter activity assays using PPARγ harboring B Y501A (red in A), C F310A (green), D A261E (sky-blue), and E F388L (blue) were shown as fold change relative to WT-PPARγ receptor activity under DMSO control (Fig. 2A). All assays were conducted in HEK293T cells in the presence of 1 μΜ compound treatment for 24 h. Dashed lines indicate SR10171 reference level. Colors of data points and error bars represent the groups based on regiochemistry. Colored bars above compound names denote the functional classification (green: non-IA, blue: partial-IA, purple: full-IA). Data represent the mean ± SD from three biological replicates (each has five technical replicates) with statistical significance over DMSO in each mutant group. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. One-way ANOVA corrected by Tukey’s multiple comparison.

Consistent with previous findings that Y501 mediates hydrogen bonding between PPARγ agonists and the LBD37,38,55, the Y501A mutation impaired both Rosi-induced agonism and inverse agonism by T0070907 (Fig. 5B). Strikingly, this mutation had no effect on the activity of non-covalent inverse agonists, suggesting that these ligands stabilize the LBD through a mechanism independent of the canonical AF2 hydrogen-bonding network involving H12. The loop region following H2a contains S273, a residue whose phosphorylation has been implicated in osteogenesis and adipogenesis15,28,30,56. However, neither S273A nor S273D mutations affected the inverse agonist activity of SR10171 analogs (Supplementary Fig. 10C, D), indicating that their binding and functional effects are not structurally dependent on this loop region.

Mutation of F310 to smaller or charged residues has been shown to reduce basal PPARγ activity50,57 and alter ligand pharmacology30. Consistent with this, the F310A mutation significantly shifted the pharmacological response of non-covalent inverse agonists from inverse agonism to agonism relative to DMSO (Fig. 5C). This further supports that non-covalent inverse agonists engage with the central region of H3 and can stabilize the LBD even when hydrophobic interactions at the base of the pocket are disrupted. In addition, the A261E mutation, associated with familial partial lipodystrophy type 3 (FPLD3)48, is a loss-of-function variant that destabilizes the LBD. Although reduced expression of A261E-PPARγ may contribute to its lower basal activity compared to wild-type (Supplementary Fig. 10A, B), both non- and partial-IAs substantially enhance receptor activity relative to DMSO (Fig. 5D). This indicates that these ligands can restabilize the mutant LBD, even in the absence of proper H2a positioning. Similarly, the F388L mutation, another FPLD3-associated variant49 that disrupts van der Waals interactions and destabilizes the H11-H12 interface, converted the response of non- and partial-IAs from inverse agonism to agonism (Fig. 5E). This suggests that these ligands can also stabilize the AF2 domain, compensating for structural deficiencies caused by the mutation.

These findings support the proposed SAR, indicating that non-covalent inverse agonists primarily regulate PPARγ activity through stabilization of the LBP, with minimal reliance on interactions with H12 and the H2-3 loop. Moreover, their ability to restore activity in destabilized receptor mutants suggests that LBP stabilization is sufficient to restore function, independent of canonical activation mechanisms.

Evaluation of insulin sensitization by PPARγ inverse agonists

Given that the SR10171 analogs exhibited similar pharmacological profiles to the parent compound, their ability to enhance insulin sensitivity was evaluated. L1-derived adipocytes were used as a model system to assess the compounds’ effects on adipokine expression, adiponectin secretion, and glucose uptake at 1 μM compound concentration both in the absence and presence of TNFα, a well-established inducer of insulin resistance in vitro24,58. Two sequential treatment regimens were tested (Fig. 6A); (1) Compound treatment first for 24-h followed by 6-h exposure to TNFα (Cpds-TNFα), and 2) TNFα treatment first for 6-h followed by 24-h exposure to compound (TNFα-Cpds). Although not statistically significant, hierarchical clustering revealed that non- and partial-IAs grouped with Rosi and SR10171, showing enhanced adipokine expression and glucose uptake in TNFα-treated adipocytes, suggesting potential insulin sensitizing effects. Based on favorable binding affinity and microsomal stability (Supplementary Table 1), three non-IAs and six partial-IAs were selected for further evaluation in both healthy and type 2 diabetic human adipocytes. Two full-IAs were included as negative controls, as they are expected to fully repress PPARγ activity and lack insulin-sensitizing potential.

A Heatmap clustering analysis of compound-induced responses in L1 cell derived adipocytes. The color scale represents compound-induced cell response with intensities normalized to the maximum response in each assay (red: enhanced, white: neutral, blue: reduced). B, C Glucose uptake and D, E adiponectin secretion from human adipocytes derived from the healthy donor (PT5020; B and D) and a type 2 diabetic donor (PT5022; C and E). Dashed lines indicate the baseline insulin response under DMSO control. Colors of bars represent the clustering based on regiochemistry. Colored bars above compound names represent the functional classification. Data represent the mean ± SD from five biological replicates with outliers excluded using an interquartile range (IQR)-based method adapted from Tukey’s fences and statistical significance over DMSO. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001. One-way ANOVA corrected by Tukey’s multiple comparison.

In healthy human adipocytes, insulin significantly increased glucose uptake compared to the no-insulin control (Fig. 6B), but no additional enhancement was observed by compound treatment relative to DMSO. In contrast, in diabetic adipocytes, SR10171, Rosi and four potent SR10171 analogs (two non-IAs and two partial-IAs) significantly enhanced insulin-stimulated glucose uptake compared to DMSO (Fig. 6C). Additionally, Rosi, non-IAs and partial-IAs significantly increased adiponectin secretion in healthy adipocytes relative to DMSO (Fig. 6D). Although variability within the DMSO control group limited statistical power in diabetic adipocytes, non-IAs still showed a ~ 10–20% increase in adiponectin secretion, with Compound 13 inducing a significant 30% increase (Fig. 6E). These results confirm that non- and partial-IAs can enhance insulin responsiveness in diabetic adipocytes by promoting both glucose uptake and adipokine expression, such as adiponectin. Notably, full-IAs significantly reduced insulin responsiveness in both healthy and diabetic adipocytes and had minimal effects on adiponectin secretion (Fig. 6B–E), reinforcing the conclusion that complete repression of PPARγ activity does not support insulin sensitization.

Discussion

The development of next-generation PPARγ modulators that retain insulin-sensitizing efficacy of glitazones while improving safety profiles remains a major challenge. We previously demonstrated that the non-covalent partial inverse agonist SR10171 holds promise as an insulin sensitizer without the adverse effects associated with the glitazones (agonists)23,24. Building on this, we present a structure-guided strategy to enhance the binding potency of non-covalent PPARγ inverse agonists through scaffold optimization of SR10171, particularly focused on the indole core. Systematic biochemical profiling revealed that subtle modifications can profoundly influence the magnitude of PPARγ repression, often independently of binding affinity. This decoupling between ligand potency and functional output underscores the complexity of receptor regulation by non-covalent inverse agonists. Functionally, non- and partial-IAs, but not full-IAs, enhanced insulin response in type 2 diabetic adipocytes, despite all inverse agonists reducing pS273 (Fig. 7). This supports prior findings that PPARγ agonism is dispensable for insulin-sensitizing gene expression28,30 and suggests that while pS273 suppression is necessary, it is not sufficient for insulin sensitization. Full-IAs that inhibit pS273 without improving insulin response imply that pS273 may serve as a ligand engagement marker more than a mechanistic driver. To address potential species-specific effects, we complemented murine studies with assays using human PPARγ constructs and validated insulin-sensitizing activity in human primary adipocytes. The pharmacological profiles were consistent across both models, reinforcing translational relevance. These results underscore the importance of fine-tuning PPARγ conformation to preserve SR10171-like functional profiles.

Created in BioRender. Kuo, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/wjs6zrq.

To probe conformational dynamics of PPARγ, we employed a two-timepoint HDX-MS screen42, which revealed that full-IAs consistently induce H12 deprotection and mid-pocket protection, an HDX signature that mirrors the loss of H12 electron density in the SR10221-bound PPARγ-LBD–SMRT complex29,39, consistent with AF2 destabilization. This highlights two-timepoint HDX-MS as a rapid, effective screen for ligand-induced conformational changes relevant to repression. MDS further clarified the energetic and spatial contributions of key residues: the reversed indole nitrogen and specific alkyl substitutions stabilize conserved binding poses within the LBP, closely reproducing known SR10221 binding modes27,28,29,39. In this orientation, para-tert-butylphenyl-substituted groups in the Western portion of the molecule may sterically clash with H12 and engage corepressor motifs via hydrophobic interactions, enhancing repression29. Alternatively, the meta-tertbutyl-substitutions may modulate coregulator preference by altering AF2 surface topology. Interestingly, the MD-derived pose of SR10221 did not fully recapitulate the crystallographic orientation of the 4-tert-butylphenyl moiety, likely due to bond flexibility and absence of the corepressor peptide in the docking template, highlighting the importance of coregulator context in pose prediction. Overall, the residue-level insights from MDS align closely with peptide-level HDX-MS results. Future studies of analog-bound PPARγ-LBD complexes, combined with expanded HDX-MS timepoints to evaluate MDS predictions, will further advance our understanding of the dynamic mechanisms underlying differential PPARγ repression59.

A notable observation is the disconnect between in vitro peptide interaction assays and cellular transcriptional outcomes. Some compounds enhanced coactivator peptide binding in AlphaScreen assays yet acted as inverse agonists in cell-based reporter gene and adipogenesis assays, or vice versa. This highlights the limitations of LBD-only peptide interaction assays, which capture binary interactions with isolated coregulator motifs and are useful for initial screening, but fail to reflect the complex, multi-domain interactome of full-length PPARγ. Given that the PPARγ interactome varies across subcellular compartments and cellular contexts60, such divergence likely contributes to the observed functional discrepancies among ligands with similar LBD-binding profiles. Future proteomics-based interactome studies will be essential to elucidate how ligand-induced conformational changes propagate through full-length PPARγ to modulate transcriptional networks in adipocytes. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating orthogonal experimental approaches.

Clustering based on bioactivity and MD simulations identifies three functional classes of inverse agonists: non-, partial-, and full-IA, each engaging PPARγ through distinct mechanisms. This mechanistic diversity underscores the potential to rationally design inverse agonist classes tailored to specific therapeutic goals: fine-tuning repression in metabolic disorders, partially restoring function in pathogenic mutants without overactivation, or achieving full suppression when maximal repression is required. For example, non- and partial-IAs restored basal activity in FPLD3-associated loss-of-function mutants, unlike full agonists like Rosi, which can cause adverse effects through hyperactivation48,61,62,63. The need for safer insulin sensitizers is especially urgent in diabetic patients with CKD, a high-risk group with limited treatment options7. While SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists64 effectively control glucose, they offer limited renal benefits and insulin sensitization. Although glitazones may provide both metabolic and renal benefits65, their use declined due to side effect concerns. Given their improved binding potency and insulin-sensitizing effects, non- and partial-IAs are promising candidates to deliver metabolic benefits while minimizing the risks associated with TZDs.

Beyond metabolic disease, PPARγ has emerged as a key player in various cancers, including breast, prostate, colorectal, esophageal, and bladder malignancies, where its dysregulation contributes to tumorigenesis28. Pharmacological modulation of PPARγ, particularly through full-IAs, offers a promising therapeutic strategy to suppress oncogenic PPARγ signaling39,66,67. Our findings suggest that full-IAs, by destabilizing H12 and reinforcing corepressor engagement, may effectively repress aberrant PPARγ activity in tumors. Notably, all inverse agonist classes rescued the transcriptional defect of the F310A mutant, which mimics the oncogenic F310S mutation10,57 known to destabilize the LBD. This highlights a potential precision oncology approach, leveraging structure-guided ligand design to restore receptor function in cancers harboring pathogenic PPARγ mutations. In parallel, modest activation of PPARα may offer additional therapeutic benefits by supporting osteocyte function and systemic energy metabolism, which are often compromised in cancer-associated cachexia and bone metastases34,68. Thus, the dual action of our compounds expands their therapeutic scope beyond insulin sensitization, positioning non-covalent inverse agonists as rational candidates for targeting both metabolic and oncogenic PPARγ pathways, while potentially preserving skeletal health.

In summary, our findings support a mechanistic model with strategic ligand design stabilizing the LBP while destabilizing H12, thereby promoting inverse agonism of PPARγ through dynamic AF2 destabilization. The flipped indole scaffold, combined with N-alkyl substitution, serves as a modular handle to fine-tune ligand pose and dynamics by engaging residues R316, I354, and L358. This study advances understanding of SARs for non-covalent inverse agonism and establishes broadly applicable strategies for gaining mechanistic insight into receptor-ligand interactions during compound screening, even in the absence of a cocrystal structure. The optimized scaffold emerges as a privileged chemotype for non-covalent PPARγ inverse agonism, enabling the development of insulin sensitizers that overcome limitations of TZD-based therapies. These findings may also inform ligand design for other ligand-regulated transcription factors, paving the way for precision pharmacology across diverse disease indications.

Methods

Cell culture

The 3T3-L1 (CL-173) and HEK293T (CRL-3216) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; 10-013-CV, Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; F0926, Sigma-Aldrich) and MycoZap™ Plus-LC antibiotic (VZA-2012, Lonza). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂. Routine mycoplasma testing was performed every three months using the MycoStrip™ detection kit (rep-mys-100, InvivoGen). Cells were passaged according to ATCC recommendations and maintained under standardized culture conditions. Primary human subcutaneous preadipocytes from healthy (PT5020 (Batch No. 0000629514), from a 60-year-old male with BMI of 30) and type-II-diabetic (PT5022 (Batch No. 0F3815), from a 75-year-old male) donors were obtained from Lonza. Cells were maintained in preadipocyte growth medium-2 (PT-8202, Lonza) supplemented by SingleQuotsTM kit (PT-9502, Lonza) according to the manufacturing instructions.

Protein expression and purification

The pET46-EkLIC-hPPARγ-LBD (PPARγ2 residues 231–505) construct was expressed in the Escherichia coli strain BL21 DE3 (Gold) competent cells (Invitrogen). Cultures were grown in terrific broth supplemented with Carbenicillin (100 µg/L) in a temperature-controlled orbital shaker (Innova) operating at 225 RPM at 37 °C. Once the culture reached an optical density (OD610) of 0.6, the temperature of the incubation chamber was lowered to 16 °C, and IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. The cultures were then incubated for 16 h before being harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing protease inhibitors (EDTA-free SigmaFast, Sigma-Aldrich) prior to subsequent harvesting and storage at −80 °C. Unless otherwise stated, all protein purification steps were carried out at 4 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM Sodium Chloride (NaCl, S9888, Sigma-Aldrich), 10% (v/v) glycerol (BP229-4, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP, 50-093-0, Hampton Research), and 40 mM imidazole), supplemented with protease inhibitors, DNase, and lysozyme. Cells were lysed using a French press operating at 20,000 psi. The crude cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation (20,000 rpm for 45 min), and the supernatant was loaded onto Ni-NTA resin pre-equilibrated with Ni-NTA buffer A (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, and 40 mM imidazole) using an AKTA protein purification system. Ni-NTA resin was washed with 20 column volumes of buffer A, and the protein was eluted using a continuous imidazole gradient with buffer B (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, and 500 mM imidazole). The Ni-NTA eluate was concentrated using Amicon Ultra 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff centrifugation tubes and exchanged into storage buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 2 mM TCEP). The protein product was verified using SDS-PAGE gel followed by Coomassie blue staining and immunoblotting.

LanthaScreen TR-FRET competitive binding assay

The assays were conducted according to the manufacturer’s manual (Life Technologies Corporation, PV4894). Briefly, 10 μL of 4× compound or vehicle control solutions were dispensed into a black 384-well low-volume plate (Greiner Bio-One), followed by the addition of 5 μL of 4× Fluormone solutions. Subsequently, 5 μL of a 4× solution containing His-hPPARγ-LBD and Goat-anti-His antibody was added. The mixture was then incubated at room temperature for five hours before being read on an Infinite M1000 plate reader (Tecan). The IC50 values of each compound were then calculated and used to estimate the dissociation constant (Kd). We applied the Cheng-Prusoff equation, using the formula: Kd = (IC₅₀ × 10⁹)/(1 + [L]/KdFluormone), where [L] is the concentration of the fluorescent ligand (5 nM) and KdFluormone is the reported dissociation constant of the tracer (2.8 nM).

AlphaScreen peptide interaction assay

The Amplified Luminescent Proximity Homogeneous Assay (AlphaScreen) assay utilized streptavidin-coated donor beads (Perkin Elmer, 6760002) and anti-His-tag antibody-coated AlphaLisa acceptor beads (Perkin Elmer, AL178M). They demonstrated high sensitivity to the proximity of the N-terminus to the LXXLL NR-box motif and the incorporation of a flexible Ahx linker. All reagents were prepared in assay buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, 0.01% NP40). In brief, 5 μL of a 400 nM solution of His-PPARγLBD was dispensed into a black 384-well low-volume plate (Greiner Bio-One), followed by the addition of 5 μL of 4× compound or vehicle control solutions. Subsequently, 5 μL of a 400 nM representative coactivator peptide biotin-Ahx-SRC1-2 (sequence: LTERHKILHRLLQEGSPSD) or a 400 nM representative corepressor peptide biotin-NCoR-D2 (sequence: DPASNLGLEDIIRKALMGSFDDK) was added, followed by another 5 μL of 4× bead cocktail. The bead mixture was incubated at room temperature for one hour before being read on an EnVision plate reader (Perkin Elmer).

In vitro phosphorylation assay

The assay was conducted using the ADP-Glo™ Kinase Assay kit from Promega. Reagents were prepared in kinase buffer (50 mM Tris, 25 mM MgCl2 (M2670, Sigma-Aldrich), 50 mM DTT, pH = 7.5). CDK5/p35 (C0745, Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with either DMSO or the CDK5 inhibitor 20-223 (865317-30-2, MedChemExpress) for 1 h at 4 °C. Purified His-hPPARγ-LBD was also incubated with DMSO or the compounds for 1 h at 4 °C. Subsequently, the CDK5/p35 solutions were mixed with the PPARγ-LBD solutions and incubated at 4 °C for another 2 h. Following this, 10 μM ATP was added, and the phosphorylation reaction was carried out in a thermocycler (30 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 30 s, cool down). ADP-Glo™ Reagent was then added, and the reaction was incubated at room temperature for 40 min. Detection reagent was then added and incubated in the dark at room temperature for an additional 40 min. Luminescence signal was recorded using the Infinite M1000 plate reader (Tecan).

GAL4-LBD/UAS promoter::Luciferase reporter cotransfection assay

HEK293T cells were plated 3.3 × 106 cells per 10-cm plate. After 24 h, cells were transfected with 8 μg total DNA (1:1 ratio of Gal4-PPAR plasmids or Gal4-VP16 plasmids to UAS-reporter plasmid) using polyethylenimine (PEI). After 24 h of incubation, cells were plated in 384-well plate at density of 10,000 cells/well, incubated 3 h, and treated with compounds or DMSO control for 18 h. Luciferase activity was quantified using Britelite Plus (Perkin Elmer). Absorbance at 490 nm was measured using Agilent BioTek Synergy Neo2 Hybrid Multi-Mode Microplate Reader.

Hepatic microsomal stability

Microsome stability was evaluated by incubating 1 µM test compound with 1 mg/mL hepatic microsomes in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The reaction was initiated by adding NADPH (1 mM final concentration). Aliquots were removed at 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 60 min and added to acetonitrile (5× v:v) to stop the reaction and precipitate the protein. NADPH dependence of the reaction was evaluated with -NADPH samples. At the end of the assay, the samples were centrifuged through a Millipore Multiscreen Solvinter 0.45-micron low-binding PTFE hydrophilic filter plate and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Data were log-transformed and represented as half-life and intrinsic clearance.

PPARγ2 transcription reporter activity assay

HEK293T cells were plated 3.3 × 106 cells per 10-cm plate. After 24 h, cells were transfected with 8 μg total DNA (1:1 ratio of PPARγ2 plasmids to PPRE reporter plasmid) using PEI. After incubating for 24 h, cells were plated in 384-well plate at a density of 10,000 cells/well, incubated 3 h, and treated with either DMSO or 1 μΜ compound for 18 h. Luciferase activity was quantified using Britelite Plus (Perkin Elmer), followed by recorded using the Infinite M1000 plate reader (Tecan).

Cell viability assay

HEK293T cells were transfected under the same condition used for the reporter assays. After 24 h, cells were plated in 384-well plate at 10,000 cells/well and incubated 3 h. Cells were then treated with either DMSO or 1 μΜ compound for 18 h. Following treatment, MTS reagent (G5430, Promega) was added and incubated for 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using the Infinite M1000 plate reader (Tecan).

Adipocyte differentiation

After 4 days of reaching confluence, 3T3-L1 cells underwent induction by replacing the media with differentiation media containing 1 μM dexamethasone, 0.5 mM IBMX, and 850 nM insulin. After 48 h, media was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS plus insulin. Then, the medium was replaced every 2 days until the assay date. Human pre-adipocytes were differentiated based on the manufacturing instructions. On day 7 post differentiation, cells were replaced with DMEM (1 g/mL glucose) supplemented with 0.2% BSA in the absence or presence of compounds for 24 h.

Oil red staining

Following the medium removal, cells were rinsed twice with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were fixed in 10% formalin at room temperature for 1 h, followed by two washes with water. The cells were then rinsed twice with 60% isopropanol and incubated in 60% isopropanol for 5 min. Freshly prepared oil red solution was added to the wells and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Cells were then washed twice with 70% ethanol, followed by two washes with water. The samples were then immersed in water for microscope imaging using the GE Healthcare IN Cell Analyzer 6000 High-Content Imaging System. After imaging, the samples were allowed to air dry overnight. The following day, 100% isopropanol was added to the samples and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Absorbance at 490 nm was measured using Agilent BioTek Synergy Neo2 Hybrid Multi-Mode Microplate Reader.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 3T3-L1 cells using RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen), and the RNA was reverse transcribed using the ABI reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Quantitative PCR was performed with a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR green (Roche). A list of primers used for these studies is shown in Supplementary Table 5.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were extracted from transiently transfected HEK293T cell pellets using RIPA lysis and extraction buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (100X, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before equal amounts of samples heated at 95 °C for 5 min with 6× SDS-PAGE loading buffer with 40 mM DTT. SDS-PAGE was performed with 15 µL of cell lysate. Following transfer (BioRad Trans-turbo) and blocking the membrane using PBS containing 3% BSA, membranes were immunoblotted using primary antibodies (anti-PPARγ (rabbit polyclonal, D69, #2430, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000) and anti-β-actin (rabbit monoclonal, 13E5, #4970, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:2000)) in PBS plus 0.2% Tween 20 overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed 3 times with PBS plus 0.1% Tween 20, treated with secondary antibodies (Li-COR, anti-rabbit 926-32211, anti-mouse 926-68070, 1:10000) in PBS plus 0.2% Tween 20 at room temperature for 1 h and imaged (LI-COR Odyssey). Fluorescence signal was quantified using ImageJ software.

Glucose uptake assay

Glucose uptake was measured using the Glucose Uptake-Glo™ Assay kit (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were washed and equilibrated in Krebs-Ringer phosphate (KRP) buffer (130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl₂, 1.3 mM MgSO₄, and 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were then stimulated either with 0 or with 100 nM insulin for 10 min. 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG) was added and incubated for an additional 10 min at room temperature to allow uptake. After several additions of buffer, luminescence was measured according to the assay protocol using the Infinite M1000 microplate reader (Tecan). All samples were processed in parallel, and data were normalized to control conditions where indicated. For primary human adipocytes, cells were equilibrated in KRP buffer supplemented with 0.2% BSA, followed by 0 or 100 nM insulin treatment for 1 h before 2DG was added.

Adiponectin ELISA

Cell culture media were collected and centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cellular debris. The resulting supernatants were stored at −80 °C until analysis. Secreted Adiponectin concentrations from human primary adipocytes and 3T3-L1-derived adipocytes were measured using the Adiponectin/Acrp30 Quantikine ELISA kits specific for human (DRP300) and mouse (MRP300) samples (Bio-Techne Corporation) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was read at 450 nm with a 570 nm reference wavelength using an Infinite M1000 microplate reader (Tecan).

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS)

Differential HDX-MS experiments were conducted as previously described with a few modifications42,69. Differential HDX-MS experiments that reported here are deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD066095. Experimental details are summarized in Supplementary Table 6.

Peptide identification

Protein samples were subjected to inline pepsin digestion, and the resulting peptides were analyzed by tandem MS/MS using a high-resolution Orbitrap mass spectrometer (QExactive, Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Following digestion, peptides were desalted on a C8 trap column and separated using a 70-min linear gradient from 5% to 40% solvent B (solvent A: 0.3% formic acid in water; solvent B: 0.3% formic acid in 95% acetonitrile). MS data were acquired in data-dependent acquisition mode with a one-second duty cycle, during which the five most abundant precursor ions were selected for higher-energy collisional dissociation MS/MS analysis. After fragmentation, each precursor ion was excluded from reselection for 16 s. The resulting MS/MS spectra were searched using Mascot (Matrix Science) with the following parameters: precursor ion mass tolerance ±10 ppm, fragment ion mass tolerance ±0.6 Da, variable modification of methionine oxidation, non-specific digestion allowing up to four missed cleavages. Peptide identifications were filtered to retain only those with a Mascot score >20 and false discovery rate < 1%. Manual inspection of MS/MS spectra was performed to validate peptide assignments. Duplicate charge states were retained for each peptide, and decoy database searches were used to eliminate ambiguous identifications. Only unambiguous peptides were included in the final peptide set for HDX analysis.

HDX-MS analysis

Experiments were carried out on a fully automated system (CTC HTS PAL, LEAP Technologies, Carrboro, NC; housed inside a 4 °C cabinet) as previously described69 with the following modifications: For differential HDX, PPARγ-LBD-ligand complexes were formed by incubating PPARγ-LBD (10 µM) with compounds (50 µM) for 1 h at 4 °C. Next, 5 μL of sample was diluted into 20 μL D2O buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, and 2 mM TCEP) and incubated for three time points (0, 10, and 14400 s (4 h)) at 4 °C for continuous labeling. The deuterium exchange was then quenched by mixing with 25 L of cold (4 °C) 3 M urea (51456, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA, A116, FisherChemical). Quenched samples were immediately injected into the HDX platform. Upon injection, samples were passed through a 2 mm × 2 cm immobilized pepsin column at 50 μL min−1 (0.1% (v/v) TFA) and the digested peptides were captured on a 2 mm × 1 cm C8 trap column (Hypersil Gold, ThermoFisher Scientific) and desalted. Peptides were eluted across a 2.1 mm × 5 cm C18 column (Hypersil Gold, ThermoFisher Scientific) with a linear gradient of 4–40% (v/v) acetonitrile (CH₃CN) and 0.3% (v/v) formic acid, over 5 min. The eluted peptides were then ionized directly using electrospray ionization, coupled to a QExactive (ThermoFisher Scientific). The intensity weighted mean m/z centroid value of each peptide envelope was calculated and subsequently converted into a percentage of deuterium incorporation. This is accomplished determining the observed averages of the undeuterated and fully deuterated spectra and using the conventional formula described elsewhere70.

Data rendering

The HDX data from all overlapping peptides were consolidated to individual amino acid values using a residue averaging approach. Briefly, for each residue, the deuterium incorporation values and peptide lengths from all overlapping peptides were assembled. A weighting function was applied in which shorter peptides were weighted more heavily, and longer peptides were weighted less. Each of the weighted deuterium incorporation values were then averaged to produce a single value for each amino acid. The initial two residues of each peptide, as well as prolines, were omitted from the calculations. HDX analysis was performed in technical triplicate on two independent preparations (n = 2) of each purified protein/complex. Statistical significance for the differential HDX data is determined by t-test for each time point and is integrated into the HDX Workbench software71. Heatmap and correlation analysis were performed using in-house R scripts.

Molecular docking and ligand preparation

Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina72,73. Initially, the compound structures in mol format were converted to energy-minimized 3D conformations and saved as mol2 files using the Maestro viewer (Schrodinger, academic license). The receptor was prepared based on the SR10221-bound PPARγ-LBD (PDB: 8B8X), covering residues 201–473 (residues 229–501 in PPARγ isoform 2) with the corepressor peptide removed. The receptor model was prepared for molecular docking with extensive energy minimization and refinement using ICM-Pro (Molsoft, LLC). AutoDockTools (version 1.5.7) was then used to prepare the ligand and receptor.pdbqt files (with torsions assigned and hydrogens added to the receptor). Docking calculations were carried out using Autodock Vina (version 1.2.5) with the search grid centered on the LBP and an exhaustiveness parameter of 100; the top 20 predicted binding modes saved per ligand. Promising binding poses were selected based on the criteria: (1) docking poses that exhibited consistent alignment of the core indole moiety and preserved the overall binding geometry relative to the SR10221-bound crystal structure were prioritized; (2) predicted binding affinity lesser than −9.25 kcal/mol, which is the value associated with SR10221’s optimal docking pose, although a few exceptions with predicted affinities around −8.5 kcal/mol were retained based on favorable spatial orientations. The selected.pdbqt docking poses were then converted back to.mol2 format with bonding information restored using an in-house Python script. Hydrogen atoms were subsequently added using PyMOL (3.1.6.1, Schrödinger), and the finalized ligand structures were submitted to Swissparam74,75 to generate corresponding.pdb and.itp files for subsequent MDS.

Molecular dynamics simulations

The MDS for each ligand were conducted with GROMACS (version 2023.2)76,77 using an in-house automated pipeline. The Charmm36 force field78,79 and TIP3 water model were used to construct the topology of the protein-ligand complex. Subsequently, a dodecahedral box was generated to center the complex, ensuring a minimum distance of 1.0 nm between the protein and the box edges. Following this, the protein was solvated with a TIP3 water model80, and ions were introduced to neutralize charge of the system. Energy minimization was then reiterated using steepest descent methods for a maximum step of 50000 or for a maximum force reached <1000.0 kJ/mol/nm. The energy-minimized system was sequentially equilibrated under 1-ns NVT and NPT restrained simulations to uphold a constant temperature (310 K) and pressure (1 bar) using a Lincs hydrogen bond algorithm, Particle Mesh Ewald long-range electrostatics, Berendsen thermostat coupling, and Parrinello-Rahman pressure coupling (NPT only)81,82,83,84. Triplicate trajectories for each ligand were generated from the last frame and two other dumps extracted from the final 10% of dumps during the NPT equilibration phase. Finally, restraints were released during each 100-ns production simulation, employing a time step of 2 fs with frames stored every 5 ps. GROMOS clustering analysis43 was performed using a dynamic cutoff starting at 0.15 nm, with the goal of meeting the following criteria: (1) the top cluster contains at least 30% of the total frames, and (2) the total number of clusters is at least five. Except for RMSD calculation, the first 20 ns of each simulation were excluded from the downstream analysis to minimize the noise from initial structural rearrangements and ensure equilibrium sampling. Post-simulation analyses and visualization were carried out using a combination of MDTraj (version 1.10.0)85, NumPy (version 2.2.6)86, Pandas (version 2.23), Scikit-learn (version 1.6.1)87,88, Matplotlib (version 3.10.3)89, and Seaborn (version 0.13.2)90, along with in-house Python scripts. Dynamic Cross-Correlation analysis44,45,46,47 was conducted based on Cartesian displacements of Cα atoms. Molecular mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) analysis91,92 was performed using the gmx_MMPBSA tool (version 1.6.4)91 to evaluate key residues within 0.6 nm of the ligands during simulations. The MD simulation checklist is included as Supplementary Table 7.

Statistical treatments and analysis

No statistical analysis was done to estimate sample sizes. All heatmap clustering analysis were clustered based on the Ward’s method. For biochemical and cell-based assays, we defined technical replicates as assay replicates and biological replicates as separate preparations of the protein or cells. Unless specified otherwise, all biochemical assays were performed with at least triplicate technical replicates and at least two biological replicates. Results were normalized as fold change over DMSO-treated cells, statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) corrected by Tukey’s multiple comparison and plotted using GraphPad Prism 10 software. Outlier detection was performed using an interquartile range (IQR)-based method adapted from Tukey’s fences. For each data point in small datasets (n ≤ 5), the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles were calculated, excluding the point under the test to prevent self-influence. Data points were classified as outliers if they fell below Q1−1.5 × IQR or above Q3 + 1.5 × IQR, where IQR = Q3−Q1. To perform the correlation and covariation analysis, R version 4.4.1 was used to analyze a collection of HDX-Workbench outputs from 26 modulator differential experiments. The results of this analysis are shown in Fig. 3. After extracting perturbation values (Δ %D) for 67 peptides at two timepoints for 26 compounds, a two tailed t test was applied to determine likelihood that the values were significantly different from 0, followed by applying a Benjamini–Hochberg multiple test correction93 to control the false positive rate. Using the set of significant peptides, a Pearson correlation analysis comparing perturbation values to functional assay activity values was conducted using the psych (version 2.5.6) package. Again, the multiple test correction method of Benjamini–Hochberg was applied and the resulting adjusted p values and R2 (Takeda et al., 2012) and representative correlation plots were plotted in R. PerformanceAnalytics (version 2.0.8) and pheatmap (version 1.0.13) packages were used to visualize covariation within the HDX-MS data set. The correlogram was generated using the corrplot (version 0.95) package in a way that only showed correlation coefficients whose corresponding covariation adjusted p values were less than 0.01.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The HDX-MS raw data generated in this study have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository under accession codes PXD066095. The other data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source Data have been placed at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29538518.

References

Scully, T., Ettela, A., LeRoith, D. & Gallagher, E. J. Obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cancer risk. Front. Oncol. 10, 615375 (2020).

Lu, X. et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 9, 262 (2024).

Corrao, S., Falcone, F., Mirarchi, L., Amodeo, S. & Calvo, L. Type 2 diabetes mellitus remission, dream or reality? A narrative review of current evidence and integrated care strategies. Diab. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-025-01761-4 (2025).

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice, C. 10 Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of care in diabetes—2025. Diab. Care 48, S207–S238 (2025).

Ojo, O. et al. The effect of type 2 diabetes on bone quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 22, 910 (2025).

Pliszka, M. & Szablewski, L. Severe insulin resistance syndromes: clinical spectrum and management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 5669 (2025).

Gonzalez-Perez, A., Saez, M., Vizcaya, D., Lind, M. & Garcia Rodriguez, L. Incidence and risk factors for mortality and end-stage renal disease in people with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease: a population-based cohort study in the UK. BMJ Open Diab. Res. Care 9, e002146 (2021).

Lazarenko, O. P. et al. Rosiglitazone induces decreases in bone mass and strength that are reminiscent of aged bone. Endocrinology 148, 2669–2680 (2007).

Breunig, I. M., Shaya, F. T., McPherson, M. L. & Snitker, S. Development of heart failure in medicaid patients with type 2 diabetes treated with pioglitazone, rosiglitazone, or metformin. J. Manag Care Spec. Ph. 20, 895–903 (2014).

Hernandez-Quiles, M., Broekema, M. F. & Kalkhoven, E. PPARgamma in metabolism, immunity, and cancer: unified and diverse mechanisms of action. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 12, 624112 (2021).

Mal, S. et al. Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) in different disease states: recent updates. Curr. Med. Chem. 28, 3193–3215 (2021).

Cataldi, S., Costa, V., Ciccodicola, A. & Aprile, M. PPARgamma and diabetes: beyond the genome and towards personalized medicine. Curr. Diab. Rep. 21, 18 (2021).

Bansal, G., Thanikachalam, P. V., Maurya, R. K., Chawla, P. & Ramamurthy, S. An overview on medicinal perspective of thiazolidine-2,4-dione: a remarkable scaffold in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Adv. Res. 23, 163–205 (2020).

Montaigne, D., Butruille, L. & Staels, B. PPAR control of metabolism and cardiovascular functions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 809–823 (2021).

Hall, J. A. et al. Obesity-linked PPARgamma S273 phosphorylation promotes insulin resistance through growth differentiation factor 3. Cell Metab. 32, 665–675 e666 (2020).

Anusree, S. S., Sindhu, G., Preetha Rani, M. R. & Raghu, K. G. Insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by TNF-alpha is improved by punicic acid through upregulation of insulin signalling pathway and endocrine function, and downregulation of proinflammatory cytokines. Biochimie 146, 79–86 (2018).

Janani, C. & Ranjitha Kumari, B. D. PPAR gamma gene-a review. Diab. Metab. Syndr. 9, 46–50 (2015).

Li, D. et al. Distinct functions of PPARgamma isoforms in regulating adipocyte plasticity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 481, 132–138 (2016).

Zou, H. et al. Nuclear receptor RORgamma inverse agonists/antagonists display tissue- and gene-context selectivity through distinct activities in altering chromatin accessibility and master regulator SREBP2 occupancy. Pharm. Res. 182, 106324 (2022).

Tan, J. et al. Small molecules targeting RORgammat inhibit autoimmune disease by suppressing Th17 cell differentiation. Cell Death Dis. 11, 697 (2020).

Chang, M. R. et al. Unique Polypharmacology Nuclear Receptor Modulator Blocks Inflammatory Signaling Pathways. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 1051–1062 (2019).

Shibata, A. et al. Pharmacological inhibitory profile of TAK-828F, a potent and selective orally available RORgammat inverse agonist. Biochem. Pharm. 150, 35–45 (2018).

Choi, J. H. et al. Anti-diabetic drugs inhibit obesity-linked phosphorylation of PPARgamma by Cdk5. Nature 466, 451–456 (2010).

Choi, J. H. et al. Antidiabetic actions of a non-agonist PPARgamma ligand blocking Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation. Nature 477, 477–481 (2011).

Asteian, A. et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of indole biphenylcarboxylic acids as PPARgamma antagonists. ACS Med Chem. Lett. 6, 998–1003 (2015).

Zheng, J. et al. Chemical crosslinking mass spectrometry reveals the conformational landscape of the activation helix of PPARgamma; a model for ligand-dependent antagonism. Structure 26, 1431–1439 e1436 (2018).

Frkic, R. L. et al. PPARgamma in complex with an antagonist and inverse agonist: a tumble and trap mechanism of the activation helix. iScience 5, 69–79 (2018).

Stechschulte, L. A. et al. PPARG post-translational modifications regulate bone formation and bone resorption. EBioMedicine 10, 174–184 (2016).

Frkic, R. L. et al. PPARgamma corepression involves alternate ligand conformation and inflation of H12 ensembles. ACS Chem. Biol. 18, 1115–1123 (2023).

Marciano, D. P. et al. Pharmacological repression of PPARgamma promotes osteogenesis. Nat. Commun. 6, 7443 (2015).

Kim, Y. H. et al. Fenofibrate induces PPARalpha and BMP2 expression to stimulate osteoblast differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 520, 459–465 (2019).

Vergori, L., Lauret, E., Soleti, R., Andriantsitohaina, R. & Carmen Martinez, M. Microparticles carrying peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha restore the reduced differentiation and functionality of bone marrow-derived cells induced by high-fat diet. Stem Cells Transl. Med 7, 135–145 (2018).

Wan, Y. PPARgamma in bone homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 21, 722–728 (2010).

Chougule, A. et al. Osteocytes contribute via nuclear receptor PPAR-alpha to maintenance of bone and systemic energy metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 14, 1145467 (2023).

Nolte, R. T. et al. Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Nature 395, 137–143 (1998).

Lee, M. A., Tan, L., Yang, H., Im, Y. G. & Im, Y. J. Structures of PPARgamma complexed with lobeglitazone and pioglitazone reveal key determinants for the recognition of antidiabetic drugs. Sci. Rep. 7, 16837 (2017).

Irwin, S. et al. Biochemical and structural basis for the pharmacological inhibition of nuclear hormone receptor PPARgamma by inverse agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 102539 (2022).

Shang, J. et al. A molecular switch regulating transcriptional repression and activation of PPARgamma. Nat. Commun. 11, 956 (2020).

Orsi, D. L. et al. Discovery and characterization of orally bioavailable 4-chloro-6-fluoroisophthalamides as covalent PPARG inverse-agonists. Bioorg. Med Chem. 78, 117130 (2023).

Abdi, H. & Williams, L. J. Principal component analysis. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2, 433–459 (2010).

Cave, E. & Crowther, N. J. The use of 3T3-L1 murine preadipocytes as a model of adipogenesis. in Pre-Clinical Models: Techniques and Protocols (ed. Guest, P. C.) 263–272 (Springer New York, 2019).

Strutzenberg, T. S. et al. HDX-MS reveals structural determinants for RORgamma hyperactivation by synthetic agonists. Elife 8, e47172 (2019).

Daura, X. et al. Peptide folding: when simulation meets experiment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 236–240 (1999).

Grant, B. J., Rodrigues, A. P. C., ElSawy, K. M., McCammon, J. A. & Caves, L. S. D. Bio3d: an R package for the comparative analysis of protein structures. Bioinformatics 22, 2695–2696 (2006).

Ichiye, T. & Karplus, M. Collective motions in proteins - a covariance analysis of atomic fluctuations in molecular-dynamics and normal mode simulations. Proteins-Struct. Funct. Genet. 11, 205–217 (1991).

Doshi, U., Holliday, M. J., Eisenmesser, E. Z. & Hamelberg, D. Dynamical network of residue-residue contacts reveals coupled allosteric effects in recognition, catalysis, and mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4735–4740 (2016).