Abstract

Reproductive history is closely linked to health, yet its relationship with biological aging and survival remains uncertain. We investigated this in the Finnish Twin Cohort, a population-based study that enables modeling of full childbearing history while controlling for common risk factors, through questionnaires and civil registries. We model the association between reproductive trajectories and survival in 14,836 women, and assess biological aging in a subset of 1054 participants using the PCGrimAge, an algorithm trained to predict biological aging and mortality risk from DNA methylation. We identify six distinct reproductive trajectories describing different timing and number of childbearing events. Women with the most live births throughout their lives (mean 6.8, SD 2.4) and nulliparous women showed accelerated aging and elevated mortality risk. These findings support the disposable soma theory of aging in modern humans, and provide valuable insights into the genetic and lifestyle-related determinants of lifespan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Life history theory suggests that, within a single lifespan, organisms must balance limited resources between reproduction and survival1. Consequently, aging — understood here as the gradual decline in physical capabilities over time — is viewed as a consequence of resource allocation favoring reproduction over bodily maintenance, as proposed by the disposable soma theory of aging2,3. Multiple studies have found a U-shaped relationship between reproduction and mortality in humans and other species: both nulliparity and giving birth to many offspring have been linked to increased mortality risk4,5,6. At one end of the life-history spectrum, lower survival prospects and low reproductive output may both be caused by poorer initial health - whereas at the other end of the spectrum, shorter lifespan in individuals with high numbers of offspring may reflect the physiological implications of a greater reproductive investment5. Interestingly, earlier reproduction has also been linked to a shorter lifespan, which may reflect a coupling between reproduction and survival independent from the number of offspring7. Yet, to our knowledge, most studies have only focused on the effects of single parameters, e.g. age at first reproduction, on lifespan5,6,7,8, and have not assessed the timing of each consecutive childbirth. But a reproductive history (including both the number and the timing of childbearing events) is highly multivariate: while classical modeling approaches are based on selected indicators (typically offspring count, age at first breeding or average interbirth interval), they need to balance parameter space, collinearity between parameters, and accuracy in the representation of reproductive trajectories. Mixture modeling methods, such as latent class analysis (LCA)9 classify reproductive histories into categories based on timing and frequency, capturing nuanced patterns while reducing overfitting and minimizing oversimplifications inherent in tabular methods. At the same time, lifespan is only a proxy for the aging process itself, and can be influenced by external events: as a consequence, it is still unknown whether increased reproductive output really accelerates the aging process itself, what is the effect of the timing of childbirth, and whether any age acceleration is already observable before old age.

DNA methylation-derived age estimates—the epigenetic clocks—can be used to approximate one’s biological age as the apparent age of the body10. Furthermore, the difference between known chronological age and estimated biological age gives us access to an individual’s aging rate, i.e. the relative speed of each individual’s own clock11. Epigenetic clocks can be categorized based on their training focus: those trained to estimate chronological age as closely as possible (such as Horvath’s clock12 and Hannum’s clock13), and those trained to assess phenotypic age (including the DunedinPACE14, PhenoAge15 and GrimAge16 clocks). The GrimAge epigenetic clock, in particular, excels in predicting time-to-death, offering a valuable measure of age-related physiological impairment, years before the end of life16. A recently developed principal component (PC)-based version of the GrimAge clock (hereafter PCGrimAge), uses PCs derived from CpG-level DNA methylation data for biological age estimation17. The PCGrimAge has enhanced the reliability of biological age estimates, as shown by reduced deviations between replicates compared with the original CpG-level clock17. The present study is based primarily on that clock.

Some pioneering cross-sectional studies18,19,20 have linked the number of pregnancies to epigenetic age acceleration, but the evidence has been equivocal21. Recently, Ryan et al. (2024)18 found that increasing parity accelerated epigenetic aging in 22 year old women using six independent epigenetic clocks. However, like in other previous studies, the focus is restricted to younger women without assessing their survival prospects severely limits our understanding of the long-term consequences of reproduction on aging. What is more, to our knowledge, previous studies have focused on the number of children or the age at first reproduction, regardless of the timing of subsequent pregnancies, and thus could not consider the effects of the full childbearing history, including later-life pregnancies18,19,20. Finally, it has so far been challenging to assess the influence of confounding factors, such as early life, socio-economic background, or genetic determinants, that could affect both reproduction and lifespan: for example, Long and Zhang recently identified 98 variants that promoted reproduction but decreased survival7. Ryan et al. controlled for genetic background through a longitudinal study design, where they found that pregnancies between age 25 to 31 years accelerated epigenetic aging using two epigenetic clocks, yet whether these effects were transient or persisted later in life remains unknown18. Thus, the long-term associations of epigenetic aging trajectories and survival with lifelong reproductive history on the one hand, and familial and lifestyle factors on the other remain largely unknown.

The current study addresses this knowledge gap by investigating whether childbearing associates with accelerated aging and lifespan in modern day humans. Based on a dataset consisting of 14,931 Finnish twin women22, we assess the effect not only of the number of offspring, but also the timing of each childbirth. To that aim, we use a dimension-reduction approach based on latent class analysis (LCA)9: briefly, we identify K typical reproductive trajectories based on a very large reference sample (n = 14,931) in our focal population (19-20th century Finland) and describe each individual as a weighted mixture of these K components. This allows for (1) the representation of any individual trajectory as a fixed-length vector of weights of size K, and (2) for analysis of the outcomes of each of the K typical strategies without attempting to separate the interlinked effects of e.g. age at first reproduction and total number of offsprings, and (3) to explore whether our study participants can be differentiated into subgroups based on their childbearing history, simultaneously providing valuable insights into the reproductive behavior of Finnish women born since the 1880’s until the mid-20th century. Given the potential balance in resource allocation between reproduction and somatic maintenance, we expect that women with higher lifetime reproduction trajectories will display accelerated epigenetic aging and a shorter lifespan. We test this by modeling survival as a function of the reproductive trajectories. Further, among women with methylation data (n = 1054), we assess differences in biological age acceleration using the PCGrimAge16,17 algorithm. As we studied twin individuals sampled as twin pairs, we accounted for the non-independence between twins from the same family by including twin pair ID as a random effect in our models. Our method also incorporates data on socioeconomic background and lifestyle-related factors, adjusting for prevalent risk factors of later life morbidity of the 20th century, allowing a rigorous examination of the interplay between reproduction, aging and lifespan.

Results

Latent class analysis identifies six reproductive classes

In order to account not only for the number but also for the timing of births, we first modeled individual reproductive trajectories as a mixture of K typical trajectories inferred from lifelong live birth data (Methods, Supplementary Results) using latent class analysis (LCA9). This data included 10,783 women, who had had at least one live birth during their life. The distribution of ages at childbirth in the raw data is shown in Fig. 1. We tested models with live births summed over 1 to 4 years bins, and K = 1 to 8 latent classes, and selected the one minimizing sample-size adjusted BIC, with the constraint of keeping a meaningful sample size in each class (at least 3% of women with maximum mixture weight in that class), and maximizing entropy and class-specific posterior probabilities (Supplementary Table 1). In the selected model, individual reproductive trajectories were described as a mixture of K = 6 classes (hereafter reproductive classes), where live births were summed over 3-year age bins (Methods; latent class parameters are given in Table 1, cross-class classification probabilities are given in Supplementary Table 2). In this framework, each reproductive class is thus defined as a typical timing and number of live births (Fig. 2a): for example, a woman in class 1 had, on average, birthgivings (SD = 1) and a high probability to give birth before age 24, while a woman in class 6 would have many live births (average 6.8, SD = 2.4) interspersed throughout her reproductive life. This result was well supported by parametric bootstrapping (Supplementary Fig. 1); under this model, women are mostly assigned to a single class (Supplementary Fig. 2). Women who had not given birth (n = 4148) were added to this data and assigned to a separate class (class 0, hereafter nulliparous) with a posterior probability of ~1 for further analyses.

a Probability estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) from a latent class model (n = 10,783 parous women). Mortality hazard ratio estimates with 95% CI for each class from a Cox proportional hazards model weighted with class-specific posterior probabilities, and adjusted for left-truncation, historical cohort and relatedness (b n = 14,836 women), and further adjusted for risk factors (alcohol use, smoking, body mass index, education) (c n = 14,836 women). d, e PCGrimAge EAA estimates with 95% CI for each class from a Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars model adjusted for age and relatedness (d n = 1054 women with DNA methylation data), and further adjusted for risk factors (e n = 1054 women with DNA methylation data). b-e The dashed red line indicates the survival analysis reference class (class 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Reproductive classes predict survival

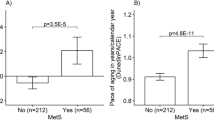

Survival differed significantly between reproductive classes when modeled as mixed Cox proportional hazards, weighted on probabilities of belonging to each class (n = 14,836, Methods, Fig. 2b, c). All of our survival models were adjusted for the historical birth cohort to control for differences in living circumstances in Finland during the range of birth years in our sample (Methods, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Results). When accounting for historical birth cohort and relatedness, the nulliparous women, or with few live births early in life (classes 0, 1 and to a lesser extent 2) had increased risk of death compared to the reference class i.e. class 3 with hazard ratios (HR) of 1.43 (z = 7.08, p = 4 × 10−12), 1.18 (z = 2.78, p = 5.3 × 10−3), and 1.10 (z = 1.81, p = 7 × 10−2), respectively, see 95% confidence intervals (CI) in Fig. 2b). Symmetrically, women with many live births throughout life (class 6 with 6.8 births on average, Table 1) also had increased mortality (HR = 1.25, z = 2.75, p = 6 × 10−3, Fig. 2b). This pattern was attenuated but not abolished when correcting for known risk factors body mass index (BMI) tobacco and alcohol use, and education (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table 3, Methods), also for the complete case sample with no covariate imputation (Supplementary Fig. 3, Methods). We used alternative modeling strategies to assess the robustness of our results. First, we implemented a singleton approach by drawing 100 random subsamples, each including one individual per twin pair from the 9496 families, and reran our survival models on these samples. Second, we reanalyzed survival time using fixed-effects models with cluster-robust standard errors. Both approaches consistently showed elevated hazard ratios for nulliparous women, early mothers, and the high lifetime reproduction group (classes 0, 1 and 6). The increased risks for nulliparous women and the high lifetime reproductive group remained statistically significant after adjusting for risk factors, underscoring the robustness of these associations (Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables 4 and 5, Methods: Alternative analysis strategies).

One women was randomly selected from each twin pair, and the estimates (shown as individual points) were collected across 100 different models with random singleton subsets. The black lines with error bars represent the aggregated estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) across all 100 models calculated by a fixed-effects meta-analysis. a-c. Mortality hazard ratio estimates for each class from a Cox proportional hazards model weighted with class-specific posterior probabilities and adjusted for left-truncation, historical cohort (a n = 9496 women per model), and further adjusted for risk factors (alcohol use, smoking, body mass index, education) with imputed data (b n = 9496 per model), and non-imputed data (c nMean=6031.15, nRange = 6011–6054 per model, sample sizes vary due to random selection of individuals with or without risk factor data in each of the 100 draws). PCGrimAge EAA estimates for each class from a Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars model adjusted for age (d n = 611 women), with additional adjustments for risk factors (e n = 611 women). The dashed red line is drawn for comparison to survival analysis at the estimates for class 3. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

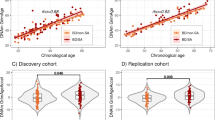

Reproductive classes predict aging

Similarly to survival, there were significant differences between the reproductive classes in epigenetic aging measured by the PCGrimAge clock in a subsample of 1054 women (Fig. 2d, e, see statistics on pair-wise comparisons between all classes in Supplementary Table 6). In our minimally adjusted model (controlling for chronological age and relatedness, Methods), we observed the most accelerated aging for women with few live births in early life (class 1) compared with the women giving birth in their late 20 s and early 30 s (classes 3-5), with 1.42 years (SE = 0.55, p = 0.01) higher biological aging rate than class 4, that had the lowest aging rate, and 2.4 live births on average (see class-specific estimates and 95% CI in Fig. 2d). When additionally adjusting for common risk factors (BMI, tobacco and alcohol use, and education), the most striking difference in epigenetic age acceleration was observed between the class with the highest reproductive output (class 6) and the class 5, which was among the lowest reproductive investment (2.0 live births on average, and had the latest timing of reproduction): class 6 had 1.35 years (SE = 0.54, p = 0.01) higher epigenetic aging rate than class 5 (Fig. 2e). We also found accelerated aging for the nulliparous women, who had 1 year (SE = 0.38, p = 8 × 10−3) more accelerated biological aging compared to class 5, the latest reproduction group (Fig. 2e). These results were also supported by our singleton approach with 100 random draws of individuals from each of the 611 families in our epigenetic age acceleration analyses (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 4). We tested whether we would observe similar patterns with two other published epigenetic clocks that are trained to capture different aspects of biological aging: DunedinPACE14, which is trained to predict pace of biological aging using 19 indicators of organ-system integrity, and PC-based17 PhenoAge, a clock that is developed to measure phenotypic age from clinical measures15. In both, the unadjusted and adjusted DunedinPACE models, we observed the highest pace of aging for the class with most birthgivings (class 6), compared to the nulliparous and classes 2–5 (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 6). We also found accelerated aging for the early mothers (class 1), yet this difference did not remain significant in the risk-factor-adjusted models. In contrast to our results for PCGrimAge, we did not observe accelerated aging for nulliparous women using DunedinPACE, while analysis with PCPhenoAge showed no differences between the classes (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 6).

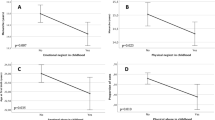

Parity, age at first child, and later health

Our latent class results are consistent with tabular approaches, as we modeled survival and epigenetic age acceleration as a function of parity and age at first childbirth using models with same covariates as in the fully adjusted models (Methods). We observed increased mortality risk for the nulliparous women (HR = 1.37, z = 5.7, p = 1.2 × 10−8, 95% CI = 1.23–1.52), and women with five or more live births (HR = 1.22, z = 2.78, p = 5.4×10-3, 95% CI = 1.06-1.40) compared to the women with three live births (used as a reference), yet no other differences between parity groups were observed (Fig. 4a). Also, the nulliparous women and women with five or more live births had accelerated aging by PCGrimAge and DunedinPACE, but only nulliparous were statistically different from other groups in the risk factor adjusted models (0.95 years of age acceleration for nulliparous compared to women with 1 live birth, SE = 0.27, p = 4.9 × 10−3, Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 5). Later age at first childbirth was associated with slightly decreased mortality risk (HR = 0.98, z = −4.12, p = 3.7 × 10−5, 95% CI = 0.97–0.99) and lower DunedinPACE of aging (Estimate = -1.5 × 10−3, SE = 6.7 × 104, p = 2.5 × 10−3) in our unadjusted models, yet in risk-factor-adjusted models this effect was statistically nonsignificant.

a Mortality hazard ratio estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) from a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for left truncation, historical cohort, relatedness, and risk factors (tobacco and alcohol use, body mass index, education; n = 10,975 women with all covariate data). The red dashed line is drawn for reference at the estimate for women with three live births. b EAA estimates calculated by PCGrimAge with 95% CI from a linear mixed effects model adjusted for relatedness, age and risk factors (n = 855 women with DNA methylation and all covariate data). The red dashed line in the epigenetic models is drawn for reference where the rate of epigenetic aging does not differ from the rate of chronological aging (at 0). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

The observed pattern of increased mortality risk and accelerated aging among the nulliparous women (class 0) and women with high lifetime parity (class 6) are in line with previous findings on the U-shaped pattern between parity and later health6,7,23,24. Among the nulliparous women, pre-existing risk factors linked to health or lifestyle might have a negative effect on reproduction, confounding both the observed increased mortality risk and accelerated aging23,25. However, the associations between increased mortality risk and accelerated aging among nulliparous women, as well as the accelerated aging observed in the high lifetime reproductive class (6), remain significant after adjusting for risk factors (Figs. 2b-d and 3, Supplementary Table 4), especially in our singleton models. This indicates that the effects of reproductive investment on healthspan are unlikely to be fully explained by confounding lifestyle factors, and that childbearing history itself may have a direct effect on survival and age acceleration. The observed high mortality risk in nulliparous women compared to parous women may also be influenced by the lack of protective effects of pregnancy and lactation towards certain diseases, like hormonal cancers, and by the lack of social support from children23,25,26. Kresovich et al.19 found pregnancy to be linked with accelerated aging in Hannum, Horvath and PhenoAge clocks in a sample of 2356 women from USA and Puerto Rico, yet these results were attenuated after risk-factor-adjustment. Here, we confirm this result, but also find accelerated aging in the nulliparous group, in addition to the women with multiple child births. We suggest these differences result from the fact that Kresovich et al.19 modeled parity ordinally per live birth, and thus it might be that potential age acceleration of the nulliparous women in their study was masked by the accelerated aging of the high-parity groups. Further, in their sample, parous women were significantly older than nulliparous women (53.7 years vs 57.0 years), which might partially explain why they did not find accelerated epigenetic aging for the nulliparous women. Ryan et al. found in 201820 that each additional pregnancy was associated with accelerated epigenetic aging using the Horvath clock in 397 women aged 20–22 years from the Philippines, and no age acceleration of the nulliparous. In 2024, in the same population, Ryan et al.18 found that parous women were epigenetically older than nulliparous using Hannum, Horvath, DunedinPACE and PhenoAge clocks, but this effect was not significant for GrimAge. Again, while the finding of accelerated aging in the high-parity groups aligns well with our results, it is in contrast with our finding of accelerated aging in the nulliparous group of women. We suggest that the discrepancies between ours and the studies by Ryan et al.18,20 may result from the fact that the population sample Ryan et al. studied was substantially younger at blood sampling than our sample (~22 y. vs ~64 y.), and Ryan et al. found significantly accelerated aging mainly in epigenetic clocks that are trained to predict chronological age, rather than mortality.

Interestingly, women who reproduce early also have increased mortality risk and accelerated aging according to PCGrimAge and DunedinPACE, although the difference between early mothers on the one hand, and other groups on the other, did not remain significant in the adjusted models in our main analysis using twin data. This result is in line with previous studies that have observed a negative correlation between age at first reproduction, and either mortality5,6,7,8 or epigenetic aging19. While our methods do not allow for causal inference, the link between early motherhood, pace of aging and survival may be partly explained by a less favorable socioeconomic background, and a more limited access to healthcare and resources in general23,27. Further, early childbirth has been associated with increased risk for later life obesity and mobility impairment, and with low education, restricted occupational progression and high risk of divorce28,29. Simultaneously, higher education is known to be associated with healthier lifestyles and increased survival while delaying pregnancy, possibly explaining the decreased mortality and slowest aging in the classes of later motherhood30. These factors related to socioeconomic status and health are partially accounted for through the inclusion of known risk factor descriptors in the current study, and thus might explain why the increased mortality risk and accelerated aging attenuates in our risk-factor-adjusted models. Finally, childbearing itself is hypothesized to be a major determinant of survival in the high lifetime reproduction group, as predicted by life-history theory1. Pregnancy, childbirth, and lactation pose significant physiological challenges31, especially for young mothers32. Early mothers may also be less resilient to parenting-related physical, emotional, and economic stress33, while experiencing higher cumulative stress and allostatic load overall27. Early motherhood and accelerated aging may also be linked by life-history theory: early reproduction can lead to shorter generation times, thus promoting the overall reproductive success of a family line7. Thus, early reproduction might be selected for even if it comes with later life costs, such as accelerated aging. At the epigenetic level, the accelerated aging in the classes of early and high reproductive investment may be related to pregnancy-induced changes19,34,35,36. However, the physiological pathways and possible epigenetic mechanisms by which childbirth could associate with aging require further investigation.

Our results indicate that regarding later-life maternal health, the women with 2 to 2.4 child births (classes 2–5) had the slowest aging and longest lifespan on average, while the average number of child births in our sample was 2.4 (Supplementary Results). In parallel, the timing of reproduction for the women with the slowest aging and longest lifespan was also around the average time of reproduction in our sample (overall average at 27.3 years, with 24.4 years and 29.8 years for first and last childbirth, Supplementary Results, Fig. 1). This convergence of longest healthspan and average reproductive behavior is not surprising under the life-history theory: however, we underline that it is likely driven both by biological parameters, and by socio-economic and cultural constraints valid in this particular context (and reflecting e.g. parental resources, housing, healthcare, childcare, and associated strain on parents in general and mothers in particular). Thus, it is important to note that these patterns reflect the characteristics of our specific study population within its cultural and historical context, and may not generalize directly to other cultural or demographic settings. Furthermore, reproductive decisions are likely influenced by a range of individual and environmental factors, with trajectories that may be adaptive for one person not necessarily benefiting another. Thus, while our results align with the idea that the fertility patterns are shaped by natural selection to balance offspring quantity and somatic self-maintenance37 within the context of a given environment, caution is needed when interpreting these findings more generally. Further research is needed to understand how these findings apply across diverse human populations.

The ability of our latent class model to robustly and convergently identify distinct classes suggests that Finnish women born during 1880-1957 can be distinguished by their reproductive histories into distinct subgroups. However, within the reproductive patterns that were most common within this population (classes 2-5), the differences in survival and aging profiles are minimal after adjusting for confounders. This suggests that, within their realized range, reproductive timing and number of offspring may have a smaller impact on aging and survival than we initially expected. This result is supported when repeating our analysis using the number of births and age at first child as predictors of survival and epigenetic age acceleration (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 5), reinforcing our confidence that we have not overlooked relevant signals, particularly concerning the timing of childbirth.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, we rely on self-reported smoking status, BMI, alcohol usage and information on the number and timing of childbirths. However, we have validated the information on childbirth for women born since the year 1950 (over 40% of women in our study sample) from the Digital and Population Data Services Agency of Finland, and self-reported anthropometric measures have been previously shown to correspond accurately to clinically measured information38 (Methods). Secondly, the wide range of birth years in our sample (1880–1957 for survival, 1909–1957 for epigenetic age acceleration) may influence the estimation of survival and aging patterns. We addressed this by controlling for cohort entry differences through left truncation in survival analyses and by including historical birth cohort as a covariate. The narrower birth year range in the epigenetic age acceleration analyses (1909–1957) reduces this concern, with further adjustments using residual-based age acceleration measures and chronological age as a covariate. Furthermore, our study uses a twin design, which mitigates the challenges posed by the wide birth year range by controlling for genetic factors and shared early-life environments. This approach reduces biases from cohort differences and variations in early-life conditions, which are known to significantly influence later-life health and well-being39. Nonetheless, future research could benefit from more focused cohort designs with narrower age ranges to refine these analyses and minimize potential biases associated with generational differences. However, including participants across a broad temporal span has also allowed us to assemble a large study sample, enhancing statistical power and enabling robust examination of reproduction, aging, and lifespan. Third, while the Finnish Twin Cohort has high response rates and has been shown to be broadly representative of the general population22,40,41, we acknowledge that some selection bias may be present due to the requirement for participants to be alive and respond to the baseline survey in 1975. Additionally, the available DNA methylation data were drawn from a combination of targeted studies and broader cohort expansions. As a result, some samples were specifically selected to investigate particular traits, rather than to represent the full cohort. Consequently, analyses based on this subsample of epigenetic data should be interpreted with caution, as the participants included may be subject to selection bias and may not fully reflect the general population by their physiological condition. Finally, while our study examines associations between reproductive history, epigenetic aging, and survival, the observational nature of our data and the methods used do not allow for causal inference. Although we employ thorough statistical approaches to control for potential confounders, our findings should be interpreted as associations rather than causal effects. Future research using, for example, quasi-experimental designs, such as Mendelian randomization or other instrumental variable approaches, may help to better establish causal relationships.

In this study, we report distinct reproductive trajectories in Western women using a latent class approach, a method that allowed us to capture the multidimensional nature of reproduction. We found both nulliparity and high lifetime reproductive output were associated with increased mortality risk. Further, we were also able to link these differences in reproductive history and survival to biological aging, years before death. Our results confirm and extend prior findings of accelerated aging in both high-parity groups, and early childbearing groups, while also highlighting the dynamic nature of epigenetic aging processes across the lifespan. However, we underline the fact that this study focuses on a population level. While it supports the notion of a balance between reproduction and aging seen as an evolutionary process, it does not suggest that this holds true at the individual level. Thus, our results do not aim to prescribe any particular reproductive choice as healthier for any given woman. Together, these findings underscore the importance of considering both the timing and frequency of reproduction, as well as the choice of epigenetic aging markers, to better understand the balance between reproduction, aging, and survival.

Methods

This study has been approved by the appropriate national research ethics committees, with the most recent approval granted by the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa ethics board in 2018 (#1799/2017). Blood samples for DNA analyses were collected from each participant after they had signed a written informed consent. The samples and data used for the research were obtained as part of the Finnish Twin Cohort studies and have been deposited in the Biobank of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare in accordance with the Finnish Biobank Act (2013). The authors state that all procedures involved in this study adhere to the ethical standards of human experimentation, as well as to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Software

All analyses were performed using Mplus (version 8.2 used throughout the manuscript)42 and R (version 4.2.3 used throughout the manuscript)43 softwares. Specific R packages used in the analysis are detailed in the corresponding method sections. All plots were generated in R with the package ggplot244 and further edited using Inkscape (version 1.4.2)45.

Participants

The study participants were a subset of the older Finnish Twin Cohort (FTC)22, a population-based prospective cohort consisting of twins from monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) pairs born before 1958, with both twins alive in 1967. In 1975, a mailed questionnaire survey was sent to all twin pairs with known residential address22. The questionnaire data includes self-reported information on health and health-related factors. This included information on family members, education, weight, height, and lifestyle-related factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption. The current study includes 14,931 women from the cohort, who were born between 1880 and 1957, and had a known number of live births. The full sample was used to compile the reproductive trajectories in latent class analysis, while a sample of 14,836 women who lived at least 40 years was used to assess the link between reproductive history and mortality risk. For a subsample of 1054 participants, blood samples were taken during 1994–2020. These samples were used to assess genome-wide DNA methylation and epigenetic age acceleration.

Live birth data

Live birth data was curated for all the study participants from the 1975 questionnaire. Participants were requested to report the birth years of each son and daughter. In case a woman had reported multiple childbirths within the same calendar year, these were considered to be from a multiple pregnancy (i.e. twins, triplets, etc.). This data was validated for all participants born between 1950–1957 (n = 4431, 41.1%) by retrieving the exact birth dates of each child from the Digital and Population Data Services Agency on 31 December 2009.

Contextual data

We adjusted our statistical analyses with variables that were hypothesized to contribute to variance in epigenetic age acceleration and mortality risk. See sample sizes by variable categories in Supplementary Table 3.

Historical birth cohort

Our study participants were born between 1880 and 1957, a period during which Finland went through drastic societal and political changes, with likely influence on the study participants’ health and survival prospects, as well as reproductive opportunities. To account for these differences in living circumstances, we assigned each participant to their birth cohort, reflecting differing living circumstances in each time period: 1880–1898 Industrial era, 1899–1917 Pre-independence, 1918–1938 Post-independence, 1939–1945 World War II, 1946–1957 Cold War.

BMI

Body mass index (BMI, kg m−2) has been shown to be associated with epigenetic aging and mortality risk46,47. For survival analysis, BMI was calculated from self-reported weight and height in 1975, which have been previously shown to correlate well (r(264) = 0.95, CI = 0.94–0.96) with measured values for women of the same cohort38. For epigenetic aging analyses, BMI at the time of blood-draw was used. As BMI may have a non-monotonous relationship with health47, we used centered BMI as a linear term as well as a quadratic term in both survival and epigenetic aging models.

Smoking

Smoking is also a known risk factor for mortality and has been shown to influence DNA methylation and accelerate epigenetic aging46,48. For survival analysis, participants were attributed a smoking status (never, former, occasional (non-daily), light (1–9 cigarettes per day), medium (10–19 cigarettes per day), heavy 20 or more cigarettes per day) based on questionnaire data from 197549. At the time of blood sampling, the participants were asked a three-level smoking status (never, former, current), which was used as a covariate in the epigenetic aging analysis. We validated the reliability of self-reported smoking information by calculating correlations between self-reported smoking pack-years (calculated as packs smoked per day multiplied by years as a smoker), preprocessed AHRR DNA methylation at locus cg05575921, which has been previously found to be hypomethylated in heavy-smokers50, as well as blood-based cotinine measures51. The Pearson correlation coefficient between self-reported pack-years and preprocessed cg05575921 methylation was r(1660) = −0.48 (p < 2.2 × 10−16), whereas the correlation between pack-years and plasma cotinine was r(224) = 0.61 (p < 2.2 × 10−16).

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol use is associated with DNA methylation, epigenetic aging, as well as morbidity and mortality risk52,53. An alcohol use index was compiled from the 1975 questionnaire, first as a continuous variable reflecting average daily use in grams of ethanol49, further binned into a categorical variable (abstainer, infrequent (<1.3 g per day), low (<25 g per day), medium (<45 g per day), high (<65 g per day), higher (≥65 g per day) as further described in Zhao et al. (2023)54. As heavy drinking was rare among the women in our cohort, the medium, high, and higher categories were combined into a medium or high category in the survival analysis. In the epigenetic aging analysis, the alcohol index at the time of blood sampling was binned to three levels (non-drinker = 0 g per day, infrequent < 1.3 g per day, frequent ≥ 1.3 g per day) due to the relatively small sample sizes for different categories within each reproductive class.

Education

Higher education has been shown to be associated with lower EAA, later-life morbidity and delayed mortality55,56. Education is also hypothesized to reflect differences in socio-economic status and social networks57. Lifetime years of education were compiled from answers about attained educational level in 1975 and 1981 questionnaires, with further details described in Silventoinen et al. (2004)58. We used education as a three-level (primary ≤ 7 years of lifetime education, secondary ≤ 10 years, tertiary > 10 years) categorical variable in our analysis for both mortality and epigenetic aging.

Handling of missing data

Not all participants answered the 1975 questionnaire, and thus had missing values for our four covariates used as indicators for common risk factors (alcohol use, smoking, BMI and education, Supplementary Table 3). For our survival analysis sample (n = 14,836), there were 10,975 women in the complete case sample, 164 women with only one missing covariate, 17 women with two missing covariates, 325 with three missing covariates and 3355 women with all four missing covariates. We evaluated the nature of missingness in R using the mcar_test from the R package naniar59, which showed our four covariates (alcohol use, smoking, BMI, and education) were not missing completely at random (MCAR; Little’s χ2(26) = 94.3, p = 1.13 × 10−9). Thus, we assumed the data were missing at random (MAR)60. For survival analysis, we used Multiple Imputation (MI) to handle missing covariate values using Mplus, assuming that these values are missing at random (alcohol use, smoking, BMI and education). MI is assumed to produce unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors, as all the available data is utilized to estimate missing variables60. We generated 20 datasets (as recommended in Little et al. 201360) with imputed covariates, and the subsequent modeling was conducted in the same way as the complete case models, by handling multiple imputed datasets with the R package mitools61. For comparison, we also ran the survival analyses with the complete case sample without imputation (Supplementary Fig. 3). For epigenetic aging data (n = 1054), there were no participants with missing education information. There were 890 women in the complete case sample, 35 women with one missing covariate, 132 women with two missing covariates and 60 women with all three (alcohol use, smoking and BMI missing). We analysed epigenetic age acceleration with Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) approach using Full Information Maximum Likelihood, which takes into account all observed data, including missing data (see section Epigenetic aging).

Epigenetic aging data

Blood sampling, DNA extraction, beadchips

Epigenetic age was assessed for a subsample of the participants (n = 1054) based on peripheral blood samples taken at an age ranging from 36 to 8922. High molecular weight DNA was extracted from the blood samples with standard automated protocols and bisulfite converted using EZ-96 DNA methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA methylation levels were measured using Illumina’s Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChips (450k) or the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChips versions 1 and 2 (EPICv1 and EPICv2), which quantify methylation levels at single-nucleotide resolution of over 450,000, 850,000 and 935,000 CpG-sites, respectively. Of the samples included in the present study, 250 were assayed using the 450k array, and 667 and 200 using the EPICv1 and EPICv2 arrays. Both twins in a pair were assayed with the same platform.

Preprocessing DNA methylation data

DNA methylation data were preprocessed in R keeping data from each array type separate. Quality control and control probe-based quantile normalization were conducted using the R package meffil62. We validated our dataset by ascertaining that all methylation-based predictors of sex were indeed predicting female sex. We discarded samples where 1) median methylated signal over all CpG sites was more than 3 SD from the expected, based on regression of median methylated signal by median unmethylated signal in all samples, 2) BeadChip inherent control probe values deviated over 5 SD from from the overall control probe mean, 3) over 20% of probes had detection p value of over 0.01, and 4) over 20% of their probes had less than 3 detected beads. Additionally, a CpG site was removed in all samples if 1) there was only background signal in over 20% of the samples (detection p value > 0.05), and 2) if the bead count of a certain probe was less than 3 in over 20% of samples. Further, all probes in sex chromosomes as well as cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs were removed63,64. Raw probe intensities for each sample were adjusted to conform to its set of normalized quantiles based on 16, 15 and 16 first control probe principal components, for 450k, EPICv1 and EPICv2 platforms respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). Beta Mixture Quantile Normalization65 to adjust the beta-values of type II design probes into a statistical distribution characteristic of type I probes was conducted using the R package wateRmelon66. Methylation beta values were obtained by dividing the intensity of methylated sites (M) by the sum of intensities from methylated and unmethylated sites (\({Beta}=M\div\left(M+U\right)\) where U represents the intensity of unmethylated probes). These processed beta values were then used as input for calculating epigenetic aging.

Epigenetic aging data

Biological age was determined from DNA methylation beta values using three published algorithms: principal component versions17 of GrimAge16 and PhenoAge15 (referred to as PCGrimAge and PCPhenoAge), as well as DunedinPACE14. We used only the probes that were present in all platforms after preprocessing (for PC-clocks 66,260 CpGs/78,464 CpGs; for DunedinPACE 144 CpGs/173 CpGs). Epigenetic ages of the above algorithms were calculated in R using the scripts provided in the corresponding publications. Epigenetic age acceleration was determined as the residual of epigenetic age linearly regressed against an interaction between chronological age and platform, and bisulfite-conversion plate in our sample of 1,054 participants.

Mortality data

The mortality follow-up ended on 31 December 2020, when dates of death were retrieved from the Digital and Population Data Services Agency Finland. The survival time for each woman was defined in years until the date of emigration, death, or end of follow-up, whichever came first.

Statistical analysis

Identifying reproductive trajectories by latent class analysis

Reproductive trajectories were identified from lifelong live birth data of 10,783 women using latent class analysis (LCA)9 with the Mplus software, analysis launched via R using the package MplusAutomation66. The process iterates from random starting values to explore different regions of the parameter space and find values that maximize the likelihood of observing the data given the model. The estimated parameters include class-specific item response probabilities (to give birth) for each indicator (ages at childbirth, see below), as well as class probability parameters, which are used to calculate individual-level posterior probabilities of belonging to each class. The estimation was done by using maximum likelihood estimators with robust standard errors (MLR) using a sandwich estimator (MLR type=COMPLEX)67. The sandwich estimator was used as it is robust to violations of non-independence among observations resulting from shared inheritance. For initiating the estimation we used 500 random sets of parameter values and 20 final stage optimization rounds; the number of starting values and optimizations was increased when needed for the model to converge to global maximum68. Global maximum was assumed when the final models converged to the same likelihood at the final stage optimization rounds68.

The optimal model solution was determined following guidelines by Sinha et al. (2021)69, suggesting to select the model with the smallest number of classes that best fits the data. Fit was assessed with Akaike’s information criterion (AIC)70 and the sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (saBIC)71,72, which both assess model accuracy based on likelihood but penalize overfitting. If these criteria disagreed we prioritized saBIC as it is recommended especially for analyses where sample size is large73,74. After prioritizing information criterion, we aimed to maximize the relative sample size of the smallest class, entropy (a measure of class separation) and class-specific posterior probabilities. We tested models with the number of live births summed over 1–4 year bins as the indicator variables (for example in the 3-year age bins, all births younger than 18 years, 18–20 years, 21–23 years, …, older than 44 years). For each age bin, we fitted latent class models with 1 to 8 classes. The number of live births within 3-year age bins were selected as indicator variables for the final latent class analysis, with 6 latent classes. Comparisons between all the tested models can be found in Supplementary Table 1. In the final model solution, we added women with no reported live births i.e. the nulliparous as an additional class, for which an individual was assigned a probability of 0.9999999 if they had no live births (and 0.0000001 as the class-specific posterior probabilities), and 0.0000001, if they had given birth during the study period and were included in the LCA solution.

Parametric bootstrapping of the latent class solution

The robustness of the final LCA model was tested with parametric bootstrapping in R. We simulated 100 datasets consisting of 10,783 individuals. For each age bin i, the individual probability of having n live births was calculated as the product of the posterior class belonging probability matrix (I classes × S individuals), by the latent class matrix (N possible live births × I classes), yielding a class-specific (N possible live births × S individuals) probability matrix. For each bootstrap replicate, an actual number of live births in each age class for each individual was drawn randomly according to these probability matrices. For each simulated dataset, the latent class model with 6 classes was then fitted.

Assessing differences in survival between the reproductive classes

The differences in survival between the latent classes including the nulliparous class were modeled in R. To account for the non-independence between women from the same twin pair, we conducted a mixed Cox proportional hazards model, where twin pair ID was used as a random effect using R packages survival75 and coxme76. To reflect latent class admixture proportions, we used proportional assignment: each individual was assigned to all of the 7 classes (6 LCA classes and the nulliparous) simultaneously with weights equal to class-specific posterior probabilities77. We used class 3 as the reference class in our survival analyses to reflect a reproductive pattern that is common within this population, as this class had the highest probability of childbirth at age 27–29, while the average age at childbirth was 27.3 in our total sample (Supplementary Results).

The follow-up started at birth, and as the study participants only entered the study provided they answered the 1975 questionnaire, we used 1975 as an entry date for left truncation in our model. Right-censored date of exit was either death, emigration or end of follow-up, whichever came first. Two models were fitted: an unadjusted model included only historical birth cohort and twin pair ID variables, whereas an adjusted model additionally included smoking, alcohol use, and BMI in 1975, and lifetime education (see variable description above). Statistically significant differences in mortality were defined by hazard ratios along with their 95% confidence intervals from the Cox proportional hazards model.

Assessing differences in epigenetic aging between the reproductive classes

The differences in epigenetic age acceleration between the 6 latent reproductive classes and the nulliparous women were modeled in MPlus using the Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) approach which controls for measurement error in the classification78. We used class-specific weights as training data to model the association between epigenetic age acceleration and latent classes. Similarly to survival analysis, we constructed two different models: an unadjusted model, which included independent variables for the twin pair ID and chronological age, and the adjusted model, which additionally included variables for smoking, alcohol use, BMI at the time of blood sampling, and lifetime education.

Assessing effects of parity and age at first child on later health

The effects of the number of live births and age at first child were explored using categorical child count with five levels (one, two, three, four and five or more birthgivings), and age at first child, respectively. All the models were run without imputation of missing covariates, and thus used the complete case sample. First, we modeled survival with mixed Cox proportional hazards models with adjustments for left truncation, alcohol use, smoking, BMI and education, using the same modeling methods in R as for the main analysis with reproductive classes. Women with three live births were used as a reference group for the survival analysis. Second, we modeled epigenetic age acceleration with linear mixed effects models in R using the package lme479. These models were adjusted with chronological age, alcohol use and tobacco use, and BMI at the time of blood sampling and lifetime education. All of the above models included twin pair ID as a random effect to account for related individuals. The epigenetic aging estimates are reported using estimated marginal means with the R package emmeans80.

Alternative analysis strategies

To test whether our results would be impacted by the modeling framework, we modeled our original Cox proportional hazards models in R with cluster-robust standard errors (Supplementary Table 5). The models were otherwise the same as our original models, but twin pair ID was used as a clustering variable instead of a random intercept. Finally, we down-sampled our dataset to a single individual per family, removing the twin structure entirely from our data. This singleton approach was repeated 100 times, each time randomly selecting one individual per family. For each random singleton subset, we modeled our left-truncation adjusted Cox proportional hazard models weighted with class-specific posterior probabilities in R, as well as our epigenetic age acceleration (EAA) models using the Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars method in Mplus, following the same adjustment methods as in our main analyses (excluding random intercept). We summarized the hazard ratios, estimates and 95% confidence intervals across these models in a fixed-effects meta-analysis in R using the package metafor81.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The Finnish Twin Cohort DNA samples and generated DNA methylation data is part of the Finnish Twin Cohort studies, but have been deposited with the Biobank of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare [https://thl.fi/en/research-and-development/thl-biobank/for-researchers/sample-collections/twin-study]. For details on accessing the data, see: https://thl.fi/en/research-and-development/thl-biobank/for-researchers/application-process. The raw data on individual reproductive history, risk factors and survival are protected and are not available due to data privacy laws. The full latent class parameters generated in this study are deposited to Figshare repository under the accession code [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30284872.v2]82. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes used in the analysis (both Mplus and R) are deposited to Figshare [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30284872.v2]82.

References

Stearns, S. C. Trade-offs in life-history evolution. Funct. Ecol. 3, 259–268 (1989).

Abrams, P. A. & Ludwig, D. Optimality theory, Gompertz’ Law, and the disposable soma theory of senescence. Evolution 49, 1055–1066 (1995).

Kirkwood, T. B. Evolution of ageing. Nature 270, 301–304 (1977).

Descamps, S., Boutin, S., Berteaux, D. & Gaillard, J.-M. Best squirrels trade a long life for an early reproduction. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273, 2369–2374 (2006).

Maklakov, A. A. & Chapman, T. Evolution of ageing as a tangle of trade-offs: energy versus function. Proc. Biol. Sci. 286, 20191604 (2019).

Wang, X., Byars, S. G. & Stearns, S. C. Genetic links between post-reproductive lifespan and family size in Framingham. Evol. Med. Public Health 2013, 241–253 (2013).

Long, E. & Zhang, J. Evidence for the role of selection for reproductively advantageous alleles in human aging. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh4990 (2023).

Stearns, S. C. & Medzhitov, R. Evolutionary Medicine: Trade-Offs (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Lazarsfeld, P. F. The logical and mathematical foundation of latent structure analysis. Stud. Soc. Psychol. World War II Vol. IV Meas. Predict. 362, 412 (1950).

Horvath, S. & Raj, K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet 19, 371–384 (2018).

Chen, B. H. et al. DNA methylation-based measures of biological age: meta-analysis predicting time to death. Aging 8, 1844–1865 (2016).

Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 14, 3156 (2013).

Hannum, G. et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 49, 359–367 (2013).

Belsky, D. W. et al. DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. Elife 11, e73420 (2022).

Levine, M. E. et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 10, 573–591 (2018).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 11, 303–327 (2019).

Higgins-Chen, A. T. et al. A computational solution for bolstering reliability of epigenetic clocks: implications for clinical trials and longitudinal tracking. Nat. Aging 2, 644–661 (2022).

Ryan, C. P. et al. Pregnancy is linked to faster epigenetic aging in young women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 121, e2317290121 (2024).

Kresovich, J. K. et al. Reproduction, DNA methylation and biological age. Hum. Reprod. 34, 1965–1973 (2019).

Ryan, C. P. et al. Reproduction predicts shorter telomeres and epigenetic age acceleration among young adult women. Sci. Rep. 8, 11100 (2018).

Harville, E. W. et al. Reproductive history and blood cell DNA methylation later in life: the Young Finns Study. Clin. Epigenet. 13, 227 (2021).

Kaprio, J. et al. The older Finnish twin cohort—45 years of follow-up. Twin Res Hum. Genet 22, 240–254 (2019).

Barclay, K. & Kolk, M. Parity and mortality: an examination of different explanatory mechanisms using data on biological and adoptive parents. Eur. J. Popul. 35, 63–85 (2019).

Keenan, K. & Grundy, E. Fertility history and physical and mental health changes in european older adults. Eur. J. Popul. 35, 459–485 (2019).

Grundy, E. & Tomassini, C. Fertility history and health in later life: a record linkage study in England and Wales. Soc. Sci. Med. 61, 217–228 (2005).

Troisi, R. et al. The role of pregnancy, perinatal factors and hormones in maternal cancer risk: a review of the evidence. J. Intern. Med. 283, 430–445 (2018).

Grundy, E. & Read, S. Pathways from fertility history to later life health: results from analyses of the English Longitudinal Study of ageing. Demogr. Res. 32, 107–146 (2015).

Câmara, S. M. A. et al. Intersections between adolescent fertility and obesity-pathways and research gaps focusing on Latin American populations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1516, 18–27 (2022).

Grundy, E. & Foverskov, E. Age at First Birth and Later Life Health in Western and Eastern Europe. Popul. Dev. Rev. 42, 245–269 (2016).

Andersson, G. et al. Cohort fertility patterns in the Nordic countries. Demogr. Res. 20, 313–352 (2009).

Ginther, S. C., Cameron, H., White, C. R. & Marshall, D. J. Metabolic loads and the costs of metazoan reproduction. Science 384, 763–767 (2024).

Pirkle, C. M., de Albuquerque Sousa, A. C. P., Alvarado, B. & Zunzunegui, M.-V. & For the IMIAS Research Group. Early maternal age at first birth is associated with chronic diseases and poor physical performance in older age: cross-sectional analysis from the International Mobility in Ageing Study. BMC Public Health 14, 293 (2014).

Barban, N. Family trajectories and health: a life course perspective. Eur. J. Popul.-Rev. Eur. de. Demogr. 29, 357–385 (2013).

Mehta, D. et al. Cumulative influence of parity-related genomic changes in multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 328, 38–49 (2019).

Okada, Y., Teramura, K. & Takahashi, K. H. Heat shock proteins mediate trade-offs between early-life reproduction and late survival in Drosophila melanogaster. Physiol. Entomol. 39, 304–312 (2014).

Ryan, C. P. et al. Immune cell type and DNA methylation vary with reproductive status in women: possible pathways for costs of reproduction. Evol. Med. Public Health 10, 47–58 (2022).

Lawson, D. W. & Borgerhoff Mulder, M. The offspring quantity-quality trade-off and human fertility variation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 371, 20150145 (2016).

Tuomela, J. et al. Accuracy of self-reported anthropometric measures—findings from the Finnish Twin Study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 13, 522–528 (2019).

Carr, D. Early-life influences on later life well-being: innovations and explorations. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 74, 829–831 (2019).

Kaprio, J. The finnish twin cohort study: an update. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 16, 157–162 (2013).

Skytthe, A. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in 260,000 Nordic twins with 30,000 prospective cancers. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 22, 99–107 (2019).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide (Muthén & Muthén, 2011).

R. Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2024).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

Inkscape. Inkscape Project. https://inkscape.org (2020).

Heikkinen, A., Bollepalli, S. & Ollikainen, M. The potential of DNA methylation as a biomarker for obesity and smoking. J. Intern Med 292, 390–408 (2022).

Jørgensen, T. S. H. et al. The U-shaped association of body mass index with mortality: influence of the traits height, intelligence, and education. Obesity 24, 2240–2247 (2016).

Cardenas, A. et al. Epigenome-wide association study and epigenetic age acceleration associated with cigarette smoking among Costa Rican adults. Sci. Rep. 12, 4277 (2022).

Kaprio, J. et al. Genetic influences on use and abuse of alcohol: a study of 5638 adult finnish twin brothers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 11, 349–356 (1987).

Grieshober, L. et al. AHRR methylation in heavy smokers: associations with smoking, lung cancer risk, and lung cancer mortality. BMC Cancer 20, 905 (2020).

Bollepalli, S., Korhonen, T., Kaprio, J., Anders, S. & Ollikainen, M. EpiSmokEr: a robust classifier to determine smoking status from DNA methylation data. Epigenomics 11, 1469–1486 (2019).

Rehm, J. et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease—an update. Addiction 112, 968–1001 (2017).

Stephenson, M. et al. Associations of alcohol consumption with epigenome-wide DNA methylation and epigenetic age acceleration: individual-level and co-twin comparison analyses. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 45, 318–328 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Association between daily alcohol intake and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analyses. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e236185 (2023).

Cutler, D. & Lleras-Muney, A. Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence, 12352, (National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc., 2006).

Iso-Markku, P., Kaprio, J., Lindgrén, N., Rinne, J. O. & Vuoksimaa, E. Education as a moderator of middle-age cardiovascular risk factor—old-age cognition relationships: testing cognitive reserve hypothesis in epidemiological study. Age Ageing 51, afab228 (2022).

Antonucci, T. C., Ajrouch, K. J. & Janevic, M. R. The effect of social relations with children on the education–health link in men and women aged 40 and over. Soc. Sci. Med. 56, 949–960 (2003).

Silventoinen, K., Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S., Koskenvuo, M., Lahelma, E. & Kaprio, J. Effect of environmental and genetic factors on education-associated disparities in weight and weight gain: a study of Finnish adult twins. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80, 815–822 (2004).

Tierney, N. & Cook, D. Expanding tidy data principles to facilitate missing data exploration, visualization and assessment of imputations. J. Stat. Softw. 105, 1–31 (2023).

Little, T. D., Jorgensen, T. D., Lang, K. M. & Moore, E. W. G. On the Joys of Missing Data. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 39, 151–162 (2014).

Lumley, T. Mitools: Tools for Multiple Imputation of Missing Data. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mitools (2019).

Min, J. L., Hemani, G., Davey Smith, G., Relton, C. & Suderman, M. Meffil: efficient normalization and analysis of very large DNA methylation datasets. Bioinformatics 34, 3983–3989 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics 8, 203–209 (2013).

Zhou, W., Laird, P. W. & Shen, H. Comprehensive characterization, annotation and innovative use of Infinium DNA methylation BeadChip probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, e22 (2017).

Teschendorff, A. E. et al. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics 29, 189–196 (2013).

Hallquist, M. N. & Wiley, J. F. MplusAutomation: an R package for facilitating large-scale latent variable analyses in Mplus. Struct. Equ. Model. 25, 621–638 (2018).

Muthén, B. O. & Satorra, A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociol. Methodol. 25, 267 (1995).

Berlin, K. S., Williams, N. A. & Parra, G. R. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 39, 174–187 (2014).

Sinha, P., Calfee, C. S. & Delucchi, K. L. Practitioner’s guide to latent class analysis: methodological considerations and common Pitfalls. Crit. Care Med. 49, e63 (2021).

Akaike, H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 52, 317–332 (1987).

Sclove, S. L. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika 52, 333–343 (1987).

Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 6, 461–464 (1978).

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T. & Muthén, B. O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 14, 535–569 (2007).

Morgan, G. B. Mixed mode latent class analysis: an examination of fit index performance for classification. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 22, 76–86 (2015).

Terry M. T. & Patricia M. G. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model (Springer, 2000).

Therneau, T. M. Coxme: Mixed Effects Cox Models. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=coxme (2024).

Lythgoe, D. T., Garcia-Fiñana, M. & Cox, T. F. Latent class modeling with a time-to-event distal outcome: a comparison of one, two and three-step approaches. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 26, 51–65 (2019).

Asparouhov, T. & Muthén, B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: three-step approaches using Mplus. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 21, 329–341 (2014).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Lenth, R. V. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (2025).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48 (2010).

Hukkanen, M. et al. Epigenetic aging and lifespan reflect reproductive history in the Finnish Twin Cohort. Nat. Commun. Analysis scripts and latent class model parameters. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30284872.v2. (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Professor Jacob von Bornemann Hjelmborg for his invaluable statistical guidance and assistance in validating our method. The authors also acknowledge the computational resources of the Institute of Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM) Technology Center. We thank all Finnish Twin Cohort study participants for their generous participation in this research. This research was supported by funding from the Emil Aaltonen Foundation (#230051, M.H.), the University of Helsinki Doctoral Program of Population Health (DOCPOP, M.H., and A.H.) the Academy of Finland Center of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics (#352792, J.K.), the Research Council of Finland (#328685, #307339, #297908, #251316, M.O., and #331320, #354649, R.C.), and the Minerva Foundation, the Liv och Hälsa sr., and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation (M.O.). Open access funded by Helsinki University Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H., J.K., R.C., and M.O. initiated and designed this study. M.O. and R.C. jointly supervised this work. J.K., M.O., M.H., and A.H. conducted data acquisition and preparation. M.H. and A.K. performed the analyses of the study. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M.H., and all authors commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hukkanen, M., Kankaanpää, A., Heikkinen, A. et al. Epigenetic aging and lifespan reflect reproductive history in the Finnish Twin Cohort. Nat Commun 17, 44 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67798-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67798-y