Abstract

Genome wide association studies of schizophrenia reveal a complex polygenic risk architecture comprised of hundreds of risk variants; most are common in the population, non-coding, and act by genetically regulating the expression of one or more gene targets (“eGenes”). It remains unclear how the myriad genetic variants that are predicted to confer individually small effects combine to yield substantial clinical impacts in aggregate. Here, we demonstrate that convergence (i.e., the shared downstream transcriptomic changes with a common direction of effect), resulting from one-at-a-time perturbation of schizophrenia eGenes, influences the outcome when eGenes are manipulated in combination. In total, we apply pooled and arrayed CRISPR approaches to target 21 schizophrenia eGenes in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived glutamatergic neurons, finding that functionally similar eGenes yield stronger and more specific convergent effects. Points of convergence constrain additive relationships between polygenic risk loci: consistent with a liability threshold model, combinatorial perturbations of these same schizophrenia eGenes reveal that pathway-level convergence predicts when observed effects will fail to sum to levels predicted by an additive model. Targeting points of convergence as novel therapeutic targets may prove more efficacious than individually reversing the effects of multiple risk loci.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genetic architecture of schizophrenia is complex and polygenic. Highly penetrant rare mutations underlie only a fraction of cases1. Rather, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) indicate that schizophrenia is predominantly associated with genetic variation that is common in the population2. These risk loci have small effect sizes, are typically found in non-coding regions, and regulate the expression of one or more genes3,4,5. Mapping GWAS loci to their target genes (termed “eGenes”, as defined by significant genetic regulation of expression) remains challenging, but is informed by expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL)6,7,8,9, chromatin accessibility10,11,12, enhancers13,14,15,16, and 3D chromatin architecture17,18,19,20,21,22. The regulatory activity of risk loci can be empirically evaluated using massively parallel reporter assays23,24,25 and pooled CRISPR screens26, and causal gene targets and functions definitively resolved by genetic engineering in human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs)10,11,17,27,28.

Schizophrenia eGenes are particularly expressed during fetal cortical development29,30,31 and in glutamatergic neurons (as well as medium spiny neurons, and certain interneurons)31,32,33. They are highly co-expressed in human brain tissue34 and cultured neurons17, show high connectivity in protein-protein interaction networks17,35,36,37, and are enriched for roles in synaptic function and gene regulation2,7,17,38,39,40,41. Likewise, transcriptomic studies of post-mortem brains from schizophrenia cases also identify aberrant expression of genes associated with synaptic function and chromatin dynamics in neurons42,43,44. The mechanism by which hundreds of distinct eGenes lead to shared molecular pathology is unknown.

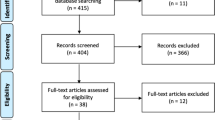

We predicted that eGenes linked to schizophrenia would share substantial downstream transcriptomic changes with a common direction of effect (termed “convergence”). Although convergence has been described in the context of loss-of-function autism spectrum disorder risk genes45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, these rare mutations almost never co-occur in the same individual. The convergent impact of common variants—which are frequently inherited together, and the impacts of which are apparent only in aggregate—remains unknown. We targeted twenty-one schizophrenia eGenes in hiPSC-derived induced glutamatergic neurons (iGLUTs) using pooled and arrayed CRISPR-based approaches, significantly perturbing seventeen (CALN1, CLCN3, DOC2A, FES, FURIN, GATAD2A, NAGA, PCCB, PLCL1, THOC7, TMEM219, SF3B1, SNAP91, SNCA, UBE2Q2L, ZNF823, ZNF804A), and resolving convergent impacts robust to experimental and donor effects. To test if convergence influenced the outcome when eGenes were inherited in combination (i.e. if eGene effects sum linearly according to the additive model26), we compared manipulation of eGenes one at a time and in groups defined by annotated functions at the synapse (“synaptic”: SNAP91, CLCN3, PLCL1, DOC2A, SNCA), or regulating transcription (“regulatory”: ZNF823, INO80E, SF3B1, THOC7, GATAD2A), or with un-related non-synaptic, non-regulatory biology (“multi-function”: CALN1, CUL9, TMEM219, PCCB, FURIN), and random combinations thereof. Altogether, with broad relevance across complex polygenic disease56,57, our work begins to experimentally determine answers to the long-standing question of how risk variants interact in human neurons.

Results

Convergence of downstream transcriptomic impacts across schizophrenia eGene perturbations

We27,58,59,60 and others11,61,62,63,64,65,66,67 demonstrated that iGLUTs are >95% glutamatergic neurons, robustly express glutamatergic genes, release neurotransmitters, produce spontaneous synaptic activity, and recapitulate the impact of psychiatric trait-associated genes. iGLUTs express most schizophrenia eGenes, including all eGenes prioritized herein27.

eGenes whose brain expression was predicted to be up-regulated by GWAS loci2 were prioritized for a pooled CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) experiment, which is currently restricted to one direction of effect. eGenes that were non-coding, located in the MHC locus, or poorly expressed in iGLUTs were excluded. First, transcriptome and epigenome imputation (EpiXcan68) of schizophrenia GWAS2 risk loci from post-mortem brain42,69 prioritized seven schizophrenia eGenes (SCZ1: CALN1, FES, NAGA, NEK4, PLCL1, UBE2Q2L, and ZNF804A) (Table 1; Fig. 1A). Second, transcriptomic imputation (prediXcan70,71,72, p < 6 × 10−6) of SCZ GWAS2 identified ~250 eGenes (SI Table 1), subsequently narrowed by considering colocalization (COLOC73,74, PP4 > 0.8) between schizophrenia GWAS2 and post-mortem brain expression quantitative loci (eQTL) peaks6, which identified 25 eGenes (SI Table 1). 22 eGenes overlapped between approaches, ten of which were coding genes associated with increased expression in schizophrenia (SCZ2: CALN1, CLCN3, CUL9, DOC2A, PLCL1, INO80E, SF3B1, SNAP91, TMEM219, ZNF823) (Table 2; Fig. 1A). Of note, our eGene selection, derived in bulk post-mortem brain, is largely preserved using an excitatory neuron-specific PrediXcan analysis (ExN-PrediXcan, Tables 1A, B).

A Schematic of schizophrenia eGene identification and prioritization. Schizophrenia eGenes were prioritized by fine-mapping (COLOC), transcriptomic imputation (PrediXcan), and/or epigenomic imputation (EpiXcan) schizophrenia GWAS using post-mortem brain expression data. B Effect sizes of significant eGenes from either dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) EpiXcan (blue), DLPFC S-PrediXcan (green) or excitatory neuron (ExN) S-PrediXcan (purple) transcriptomic imputation studies. The size of circles corresponds with the −log10(adjusted p value). C Log2(fold change) of all eGenes in the arrayed experiment following single (teal) and joint perturbations across all 15 eGenes (yellow) or functional (orange) or random (maroon) sets of five eGenes in D21 hiPSC-NPC derived iGLUTs, using individual vectors. The size of circles corresponds with the −log(adjusted p value) from a one-tailed t test. D Log2(fold change) of all eGenes in the pooled experiments SCZ1 and SCZ2, comparing all perturbed cells of one target eGene identity to all other cells of different eGene identities (blue) or compared to only Scramble gRNA (teal). The size of circles corresponds with the −log(adjusted p value) from a one-way pairwise Wilcox Rank Sum. Created with BioRender.com.

Pooled CRISPR screening combined single-cell RNA sequencing readouts and direct detection of sgRNAs75. Two independently designed, constructed, and validated pooled CRISPRa libraries (SCZ1 and SCZ2) were transduced into iGLUTs from two donors in independent experiments at unique developmental time-points (DIV7 or DIV21, SI Fig. 1F). Non-perturbed cells from both SCZ1 and SCZ2 demonstrated gene expression patterns that correlated with expression in the adult postmortem DLPFC in neurotypical controls (SI Fig. 12A–C) and cortical neurons. Specifically, these cells were most strongly correlated with fetal cells transitioning to neuronal fate, fetal excitatory neurons, and cortical adult neurons (SI Fig. 13). The large number of presumably wildtype neurons in the population expressing either a scramble gRNA or no detectable gRNA at all (>60% of all pooled cells, see SI Fig. 4A), mitigates the possibility that results were confounded by non-cell autonomous effects. Likewise, there was no significant difference in the degree of variance in maturity of the cell population between experiments and imputed cell fractions were not correlated with perturbation status (SI Figs. 2 and 3). An unsupervised framework, Weighted Nearest Neighbor Analysis76, assigned successful perturbations; in total, we resolved perturbations of six of seven SCZ1 eGenes (SCZ1: CALN1, FES, NAGA, PLCL1, UBE2Q2L, and ZNF804A; ten gRNAs each) and four of ten SCZ2 eGenes (SCZ2: CLCN3, SF3B1, TMEM219, ZNF823; three gRNAs each). For 5401 and 6352 cells, respectively, we identified the sgRNA in each cell, the cis target gene with differential expression, and the downstream trans alterations to pathways resulting from initial cis up-regulation. Following QC, normalization, and removal of doublets (cells containing more than one sgRNA), an average of 316 cells per sgRNA were successfully perturbed (ranging from 93 to 552) for a total of 3640 perturbed cells and 210 scramble controls (SI Fig. 4−7). Upregulation of eGenes by CRISPRa ranged from 0.2 to 3 log2 fold-change (Log2FC), comparable to the predicted effect sizes [SCZ1 (0.08–0.35); SCZ2 (0.2–0.77)] and eGene expression changes (Log2FC range 0.3–5.2) in the post-mortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Fig. 1B, C; SI Tables 2,3; Fig. 8). Effects of different gRNAs targeting the same eGenes were highly concordant, even when the degree of perturbation varied (SI Fig. 15). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs, pFDR < 0.05, Supplementary Data 2) were enriched for neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, proteasome, and spliceosome Gene Ontology and KEGG Pathways terms (Supplementary Data 3), suggesting that diverse eGenes might impact similar neural processes and pathways.

We define “convergence” as the independent development of transcriptomic changes in the same direction resulting from all eGene perturbations. DEGs were meta-analyzed (using METAL), and “convergent” genes were defined as those with shared direction of effect across all eGene perturbations and with non-significant heterogeneity between eGenes (Cochran’s heterogeneity Q-test pHet > 0.05). Across all schizophrenia eGenes, 363 convergent genes (Bonferroni meta p-value<=0.05) were identified by meta-analysis, with 77 passing multiple testing correction (SI Data 2).

To identify groups of genes with similar expression patterns across eGene perturbations, we define “convergent networks” as relationships between genes that are co-regulated by shared biological mechanisms. Unsupervised Bayesian bi-clustering77 and gene co-expression network reconstruction from the pooled CRISPRa single cell RNAseq (n = 3850 cells, 16,851 genes, donor/batch corrected and normalized to adjust for covariates such as cell heterogeneity) identified high-confidence co-expressed gene networks. Across the pooled single-cell experiments, 1048 protein-coding source node genes (>5 edges) were identified, with a total network membership of 1869 genes that clustered together in at least 20% of the runs (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Data 3), and significant enrichments for gene targets of schizophrenia GWAS loci as well as transcription factors (AP4 (TFAP4)62, NFAT63, ERR164, and TCF478,79) and miRNAs (miR-30) that regulate schizophrenia GWAS loci (Fig. 2A, i–iii). The cross-target convergent network was enriched in biological pathways implicated in schizophrenia etiology (SI Fig. 9); overrepresentation analysis revealed schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder common and rare risk genes to be significantly over-represented in node genes shared across all eGene perturbations (Fig. 2A, i; Supplementary Data 3).

A Convergent network resolved across the downstream transcriptomic impacts of all 10 target perturbations in the pooled experiments SCZ1 and SCZ2 identified 1869 convergent genes with enrichments for (i) brain-related GWAS genes, (ii) transcription factor binding sites of known schizophrenia-associated TFs (TFAP4, NFAT and ERR1), and (iii) common and rare variant target genes. B Convergent networks resolved across the downstream transcriptomic impacts of all fifteen target perturbations in the arrayed assay identified 255 convergent genes with enrichments for (i) miRNA targets and (ii) transcription factor binding sites of known schizophrenia-associated TFs (TFAP4, NFAT and ERR1), and (iii) common and rare variant target genes. C While largely distinct, the resolved convergent networks from the arrayed and pooled experiments shared 16 significant enrichments for miRNA targets and 4 significant enrichments for TF targets – many of which are thought to play a role in the regulation of schizophrenia-associated genes. Ai, 2Bi Overrepresentation analysis using one-tailed Fisher’s exact test for gene enrichment in curated disorder gene lists with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR multiple testing correction. Aii-iii, Bii-iii, C Geneset enrichment based on one-tailed hypergeometric test P values with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR multiple testing correction using FUMA GENE2FUNC. D Overlapping nodes between the two networks were often involved in neuronal proliferation and differentiation. Created with BioRender.com.

To study the strength and composition of convergent networks, we define “network convergence” as the sum of the network connectivity score (i.e., networks with fewer nodes and more interconnectedness have increased convergence). We endeavored to identify the biological factors (e.g., number of eGenes, functional similarity of eGenes, and eGene co-expression) that influenced network convergence. eGene number tested the number of eGenes used to generate a convergent network. Functional similarity (i.e., the degree of shared biological functions amongst eGenes) was calculated in two ways: Gene Ontology semantic similarity scoring (within biological pathway, cellular component, and molecular function)80, and synaptic/signaling score (proportion of eGenes with annotated function as either “signaling” for pooled or “synaptic” for arrayed). The brain expression correlation was calculated as the strength of the correlation of eGene expression in the post-mortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex6 (see Methods, SI Fig. 10). Bayesian reconstruction81 was performed across all random combinations of eGene perturbations from the pooled experiment (1003 unique eGene-Convergent Network sets) and arrayed experiment described in the following section (32,752 sets) and resolved distinct networks (Fig. 3B, E). Principal components analysis tested the effect of biological factors on the network convergence scores (Fig. 3C, D, F, G; SI Fig. 10–11). Only brain expression correlation and the proportion of synaptic/signaling genes were significantly positively correlated with network convergence across all sets in both the pooled [brain expression correlation: Pearson’s r = 0.24, adj. p value < 0.001, signaling proportion: Pearson’s r = 0.14, adj. p value < 0.01, n = 826] and arrayed experiments [brain expression correlation: Pearson’s r = 0.083, Bonferroni adjusted p value < 0.001, signaling proportion: Pearson’s r = 0.25, adj. p value < 0.001, n = 16319] (Fig. 3D, G). The average expression of perturbed eGenes was positively correlated with network convergence but was only significantly associated in the arrayed experiment (Fig. 3D, G). Finally, although SCZ1 and SCZ2 pooled CRISPR screens were generated from distinct differentiation timepoints, the proportion of eGene perturbations by experiment did not correlate with the degree of network convergence, indicating that we have adequately controlled for variation in neuronal maturation (Fig. 3D; Pearson’s r = 0.062, Bonferroni p value = 1).

A Defining convergence and calculating convergent network strength. Here, we define convergence as the independent development of transcriptomic similarities between separate gene perturbations that move towards union or uniformity of biological function. B–G Principal component analysis (PCA) of the convergence scores, the three Gene Ontology scores (Molecular Function, M.F.; Biological Process, B.P.; Cellular Component, C.C.), brain expression correlation (B.E.C), and sample size across all resolved networks in both the pooled and arrayed assays revealed that some functional scores have similar influence on variance as convergence (SI Fig. 19). B, E Distribution of the degree of convergence (x axis) of networks across all possible combinations of 2–8 (y axis; number of sets tested within each set) target perturbations from the single-cell pooled experiment (B) and arrayed experiment (E) across all possible combinations of 2–14 target perturbations from the arrayed experiment show an influence of sample size on the ability to resolve a network. Data are represented as median values, lower and upper hinges correspond to the 1st and 3rd quartiles, upper and lower whiskers represent the largest values within 1.5*IQR (inter-quartile range) from the first or third quartile. Each point represents convergence based on biclustering between 2–8 unique combinations of CRISPR perturbations. B N = 4 replicates per condition (2 x donors, 2 x independent replicates per donor). E N = 2 biological replicates, 10 gRNA replicates (SCZ1); N = 2 biological replicates, 2 technical replicates (sequencing batches) and 3 gRNA replicates (SCZ2). C, F For both the pooled (C) and the arrayed (F) experiment, PCs 1 (x axis) and 2 (y axis) explain ~62% of the variance between networks. PC loadings demonstrate the influence of each variable on the variance between networks; within the first two PCs, the influence of brain expression correlation (B.E.C) and proportion of signaling genes perturbed (S.P) on PCs 1 and 2 on variance explained is more strongly related to convergence degree compared to other functional scores. Since degree of convergence is influenced by number of eGenes perturbed, we ran PCA analysis within networks of the same set size and found that the pattern of influence of signaling proportion and brain expression correlation is maintained when convergence is ranked within set size shown in SI Fig. 20. D, G This corresponds to an overall significant positive correlation between network convergence degree, signaling/synaptic proportion of perturbed genes in a set, and brain expression correlation between genes in a set (Bonferroni adjusted p value of Pearson’s correlations: *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001. Created with BioRender.com.

Convergence constrains the total impact of combinatorial perturbations of schizophrenia eGenes

We manipulated eGenes in combination to approximate the polygenic nature of schizophrenia and test whether convergence between eGenes influences observed effects. Given that genes implicated in synaptic biology and epigenetic/transcriptional regulation are enriched for the schizophrenia risk2,7,17,38,39,40,41, we sought to generate three groups of eGenes, linked to synaptic biology, gene regulation, or neither (Fig. 1A, arrayed experiment). Unconstrained by the unidirectionality of pooled CRISPR screens, we did not restrict our list to eGenes with a single direction of effect. From the 18 coding genes prioritized by the intersection of transcriptomic imputation and colocalization, eGenes were separated into discrete functional categories based on gene ontology annotations. Our final gene list included five synaptic genes (SNAP91, CLCN3, PLCL1, DOC2A, SNCA), five regulatory genes (ZNF823, INO80E, SF3B1, THOC7, GATAD2A), and five genes with non-synaptic, non-regulatory functions, termed “multi-function” (CALN1, CUL9, TMEM219, PCCB, FURIN) (Table 2; Fig. 1A).

We applied an arrayed design (i.e., distinct conditions in each well) to manipulate schizophrenia eGenes alone and in combination, allowing us to capture cell autonomous and non-cell autonomous effects in a manner not possible in the pooled design (Fig. 4, SI Table 4, SI Fig. 19). Endogenous expression was increased and decreased (via CRISPRa and shRNAs, respectively) in the direction associated with schizophrenia risk. CRISPRa and shRNA were specifically selected for perturbation due to the potential for simultaneous, bi-directional perturbation of target eGenes in joint perturbation conditions (see Methods). Three to five vectors per gene were tested in 7-day-old (D7) iGLUTs, identifying the single vector that best achieved the level of significant perturbation predicted by eQTL analyses as confirmed by qPCR (SI Fig. 1E). Each eGene was perturbed in 21-day-old (D21) iGLUTs for 72 hours (Fig. 1D, SI Fig. 1F, G, 19A, and 21A), individually and jointly, including appropriate vector and scrambled controls, from two neurotypical donors with average polygenic risk scores (one experimental batch per donor). Three groups of five random genes, one group of ten random genes, and one group of all fifteen genes were also included. Significant (p < 0.05) changes in eGene expression in iGLUTs were confirmed by RNAseq in 13/15 eGenes (SNAP91, CLCN3, PLCL1, DOC2A, SNCA, ZNF823, SF3B1, THOC7, GATAD2A, CALN1, TMEM219, PCCB, FURIN) (SI Fig. 1G, SI Fig. 19A); we validated the magnitude and direction of experimental eGene perturbation relative to the dosage effects of the top predicted causal SNPs (e.g., eQTL effect size) and predicted eGene expression changes (Fig. 1B, D; SI Table 2–4). Across donors, donor status did not significantly impact the degree of eGene perturbation (SI Fig. 1Hp = 0.75, paired t test). Single perturbation of eGenes by CRISPRa ranged from 0.07 to 0.44 log2 fold change, and RNAi ranged from −0.22 to −0.87 log2 fold change, comparable to EpiXcan effect sizes of 0.10 to 0.31 and −0.06 to −0.20 and PrediXcan effect sizes of 0.22 to 0.77 and −0.17 and −0.38 for corresponding eGenes.

A Schematic of differential expression analysis. Individual eGene perturbations, the implementation of the expected additive model based on the latter and the measured combinatorial perturbation permit the detection of interactive effects through comparison with the additive model. B Combinatorial perturbation of synaptic and regulatory eGenes resulted in non-additive effects on expression across 16.8% (synaptic) and 20.2% (regulatory) of the transcriptome. No significant non-additive effects were seen following joint perturbation of non-synaptic, non-transcriptional regulatory eGenes. Teal = proportion of genes showing significant non-additivity (two-tailed FDR < 0.1); blue = proportion of genes showing no significant non-additivity. C GSEA of non-additive genes in the Synaptic eGene set demonstrated significant enrichment for genes relating to brain disorders and synaptic function. GSEA of non-additive genes in the Regulatory eGene set demonstrated significant enrichment for genes relating to brain disorders and synaptic function. SCZ schizophrenia, CNV copy number variant, FMRP Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein, FDR false discovery rate. D Non-additive effects following combinatorial perturbation of sets of five, ten, and fifteen eGenes randomly assigned from the synaptic, regulatory, and multi-function eGene groups. The proportion of the transcriptome exhibiting significant non-additive effects increased with increasing numbers of perturbed eGenes (average of 5.1%, 10.0% and 19.2% of the transcriptome with non-additive FDR < 0.1 after joint perturbations of 5, 10, and 15 eGenes, respectively).

Across the majority of the schizophrenia eGenes in our arrayed experiment, competitive gene-set enrichment analysis using 698 manually curated neural59 gene-sets (SI Fig. 19B, C, SI Fig. 20A, Supplementary Data 1) resulted in DEGs (pFDR < 0.05) that were strongly enriched for gene-sets related to rare and common psychiatric disorder risk genes (11/15) (SI Fig. 20B), pre-synaptic biology (10/15) (SI Fig. 20C), and glutamatergic neurotransmission (10/15) (SI Fig. 20D).

Overall, we again observed robust convergence at the gene- (METAL77, p < 1.92 × 10−06) and network-level (Bayesian network reconstruction81) (Supplementary Data 3). A densely interconnected network of 255 genes (n = 63 samples, 4/sgRNA or shRNA, 25,487 genes, and normalized to adjust for covariates such as donor) was significantly enriched for biological pathways implicated in schizophrenia etiology; over representation analysis revealed that target genes of schizophrenia, intellectual disability, and autism spectrum disorder common and rare variants were significantly over-represented in the network (Fig. 2B, i; Supplementary Data 3), as well as genes regulated by miRNAs and transcription factors implicated in schizophrenia etiology, such as hsa-miR-124a82 and NKX2 83 (Fig. 2B, ii–iii). Separation of schizophrenia eGenes based on either signaling (SI Fig. 9A) or regulatory (SI Fig. 9B) function resolved unique convergent networks with no overlap in node genes, suggesting that the functional similarity of schizophrenia eGenes affects downstream convergence. Each of these networks included neuropsychiatric risk genes as well as those annotated for synaptic and immune signaling function (Supplementary Data 3). Networks derived from arrayed and pooled experiments shared significant enrichments for targets of miRNAs and transcription factors associated with schizophrenia (Fig. 2C), although only nine node genes overlapped (Fig. 2D).

Following combinatorial manipulation of schizophrenia eGenes, most genome-wide effects occurred as predicted by summing differential expression for single eGene perturbations (“expected additive” model, Box 1), yet 16.8% of the total transcriptome for synaptic eGenes and 20.2% for the regulatory eGenes did not (Fig. 4; SI Figs. 21–23; SI Table 4). We term these overwhelmingly sub-additive effects (SI Fig. 21D) as “non-additive” (Bayes moderated t-statistics, FDR p < 0.1) and report π1 synergy coefficients84 of 43.86 (synaptic eGenes), 42.74 (regulatory eGenes), and 0.00 (multi-function eGenes). Non-additive genes resulting from combinatorial synaptic and regulatory eGene perturbations were significantly enriched for SZ risk genes as well as synaptic gene sets (Fig. 4C).

Key controls demonstrate that non-additive effects did not result from technical limitations of our approach. Consistent with single-cell level effects, observations were similar whether tested from independent expression vectors (Fig. 4), a single multiplexed vector expressing all gRNAs27 (SI Fig. 22A–F), or a polycistronic gRNA vector (SI Fig. 22G, H). Likewise, modified ECCITE-seq confirmed a high number of unique gRNA integrations at the single cell level (SI Fig. 22I). Non-additivity could not be attributed to differences in the magnitude of eGene perturbation between individual and combinatorial perturbations across both donors (SI Fig. 21B, combined donors p > 0.05 Wilcoxon ranked sum test, individual donors p > 0.05 two-way ANOVA), reduced fold-change of non-additive genes (SI Fig. 23C), or differences in baseline expression between non-additive and additive genes (SI Fig. 23D).

Although increasing the number of eGenes perturbed increased the degree of interactive effects on transcription (compare joint perturbations of random sets of 5, 10 and 15 eGenes, Fig. 4D, SI Fig. 23A), our data suggested that specific eGenes may drive non-additive effects; for example, log2FC of CLCN3 (synaptic) and INO80E (regulatory) are the most correlated with synergy coefficients (SI Fig. 16). When evaluated across all eGene sets, the proportion of synaptic (Pearson’s r = 0.49) and regulatory (r = 0.45) eGenes in a set positively correlated with non-additivity, while proportion of multifunctional eGenes was strongly negatively correlated (r = −0.94).

Given that >95% of non-additive genes (whether up- or down-regulated, FDR p < 0.1) showed less differential expression than predicted by the additive model (i.e., changes that were “less up” or “less down” than expected) (SI Fig. 21C), we queried whether overlapping downstream transcriptomic effects (e.g., convergence) constrain the total effects observed in combinatorial perturbation.

Across all combinational perturbations, convergence was significantly correlated with the degree of non-additive effects seen (Fig. 5A, Pearson’s r2 = 0.6569, p = 0.0147). The robust gene-level convergence observed for the synaptic (1070 genes) and regulatory (1070 genes) eGene groups was dramatically reduced in the multi-function eGene group (71 genes) (METAL77, p < 1.92 × 10−06) (Fig. 5B–E; Supplementary Data 3). Convergent genes highly overlapped with non-additive genes (Fisher’s exact test, p < 2.2 × 10−16 for both synaptic and regulatory eGene groups). 71% (761 of 1070) and 94% (1000 of 1070) of convergent genes downstream of synaptic and regulatory eGenes, were included in respective non-additive gene lists (Fig. 5C, D). Convergent effects of synaptic eGenes were enriched for synaptic function (e.g., mGluR5 interactors, p = 1.64 × 10−03) and brain disorder (e.g., schizophrenia GWAS, p = 8.41 × 10−05) gene-sets (Fig. 5F); regulatory eGene convergence was also enriched for brain disorder gene-sets (e.g., bipolar disorder, p = 9.92 × 10−06) (Fig. 5G). Taken together, these findings highlight convergent effects between schizophrenia eGenes on synaptic function and brain disorder risk.

A–E Meta-analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) elicited by individual eGene perturbations for each five-gene grouping using METAL to identify DEGs that showed altered expression consistently in the same direction across all five eGene perturbation conditions for each set of eGenes. A Convergence across individual eGene perturbations is correlated with the degree of non-additive effect seen in the corresponding joint perturbation condition. Two-tailed Pearson’s r2 = 0.6569, p = 0.0147. Teal number of genes showing significant non-additivity (two-tailed FDR < 0.1); yellow no. of genes showing significant convergent effects (two-tailed FDR < 0.1) for each perturbation set. B For each joint eGene perturbation group, non-additive impacts on transcription were compared with genes showing significant convergence across individual perturbations for the same eGene set. C Evidence of convergence was found in 1070 genes across the synaptic eGene perturbations, 761 of which also exhibited non-additive effects in the additive-combinatorial comparison for the same set. D Evidence of convergence was found in 1070 genes across the regulatory eGene perturbations, 1000 of which also exhibited non-additive effects in the additive-combinatorial comparison for the same set. E No significant non-additive effects and only minimal convergence could be seen in eGene perturbations across functional pathways. F GSEA of convergent genes in the synaptic and regulatory eGene groups demonstrated significant enrichment for genes relating to brain disorders and synaptic function. SCZ schizophrenia, CNV copy number variant, FMRP Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein, ID intellectual disability, PPI protein-protein interaction, KEGG Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, FDR false discovery rate.

Convergent signatures represent plausible therapeutic targets

Individually targeting all eGenes with perturbed expression in each patient is an insurmountable challenge. If instead it were possible to reverse the impact of many schizophrenia eGenes by targeting a smaller number of shared downstream targets, convergent networks might represent important therapeutic targets.

We identified drugs predicted to manipulate top node genes85. Across all eGene perturbations, reversers of convergent node signatures were enriched for mechanisms previously associated with psychiatric disorders, including HDAC inhibitors86 (normalized connectivity score (NCS) = −1.63; FDR adjusted p val<0.08), ATPase inhibitors87 (NCS = −1.61; FDR < 0.08), and sodium channel blockers88 (NCS = −1.59; FDR < 0.08). Conversely, mimickers of convergent node signatures were enriched for pathways associated with stress response, including glucocorticoid receptor agonists (NCS = 1.66, FDR < 0.08) and NF-κB pathway inhibitors (NCS = 1.60; FDR < 0.2) (Supplementary Data 4). Finding only nominally significant enrichments in non-neuronal cell lines suggests these may be neuron-specific drug responses.

Three drugs that opposed the transcription signatures of top convergent nodes specifically in neurons or neural progenitor cells (NPCs) were prioritized (see Methods, Box 2): anandamide (reverser of convergent network signature, NCS = −1.59, FDR = 1 as well as CALN1 signature alone, NCS = −1.23, FDR = 0.15), simvastatin (NCS = −1.31, FDR = 1; TMEM219, NCS = −0.8823, FDR = 0.25), and etomoxir (Convergence, NCS = −1.86, FDR < 2.2e-16; CALN1, NCS = −1.42, FDR = 0.0355; TMEM219, NCS = −1.09, FDR = 0.0112) (Supplementary Data 4). These drugs were tested for their ability to reverse, or oppose, the effects of paired schizophrenia eGene perturbations in iGLUTs: CRISPRa for eGenes was followed by treatment with matched reverser drugs (CALN1: anandamide and etomoxir; TMEM219: simvastatin and etomoxir). Downstream transcriptomic (bulk RNA-seq) and phenotypic (high content imaging, multi-electrode array) assays were assessed to resolve eGene-drug effects on neuronal molecular, morphological, and physiological phenotypes (Fig. 6 and SI Figs. 28–30). All drugs reversed or suppressed the transcriptomic impact of the CRISPRa perturbation alone. Notably, simvastatin ameliorated the transcriptomic impact of TMEM219 and blunted an increase in synaptic density caused by TMEM219 perturbation (two-way ANOVA, CRISPRa perturbation p < 0.001; CRISPRa perturbation x drug treatment interaction p < 0.05) (Fig. 6A, B). Etomoxir limited the transcriptomic impact of perturbations of both CALN1 and TMEM219 (SI Fig. 28A, B). Thus, it may be possible to pharmacologically reverse convergent networks rather than targeting schizophrenia eGenes individually.

In vitro validation of drug-eGene phenotypic interactions. A Effects of 48-hour treatment with 10 µM simvastatin on synaptic puncta density in TMEM219 CRISPRa perturbed (teal) or non-perturbed (purple) iGLUT neurons. Syn1-positive puncta values are expressed relative to MAP2-positive neurite length in each well. Perturbation of TMEM219 expression with CRISPRa significantly increased synaptic puncta density; this increase was partially ameliorated by 48 hr treatment with 10 µM simvastatin (two-way ANOVA; CRISPRa variation p < 0.0001; CRISPRa x Drug treatment variation p < 0.05). N minimum of two independent experiments across 2 donor lines with 12 technical replicates per condition. Values for each technical replicate in imaging experiments were averaged from nine separate images per single well. B Treatment of cells perturbed with either TMEM219 CRISPRa with 10 µM Simvastatin reverses or suppresses the transcriptomic impacts of the schizophrenia eGene perturbations alone (SI Figs. 28–30). Treatment of cells with CRISPRa TMEM219-gRNA and 10 µM Simvastatin over 48 hours opposes the transcriptomic impact observed in CRISPRa TMEM219-gRNA + Vehicle-treated cells. Venn diagram of significant DEGs at an (top left) adjusted p val ≤ 0.05 and at an (top right) unadjusted p value of ≤0.05. (bottom) Dot plot demonstrating the logFC of each gene in either the TMEM219 + Vehicle (green) or TMEM219 + 10uM Simvastatin (yellow) condition, ordered by degree of logFC in the TMEM219 + Vehicle-treated cells. Size of the points corresponds to the −log10 (adjusted p value).

Discussion

Shared downstream effects between target genes of schizophrenia GWAS loci were greatest when eGenes had shared biological functions, and enriched for psychiatric risk, brain development and synapse biology genes. Convergent signatures were experimentally robust, detected in three partially overlapping lists of schizophrenia eGenes, whether manipulated in arrayed or pooled experimental designs, and regardless of whether iGLUTs shared a common donor, cell type of origin, or developmental time point. Increased convergence between eGenes with shared biological function correlated to smaller than expected (“sub-additive”) effects following combinatorial perturbations of these same eGenes. Of note, beyond transcription, combinatorial eGene manipulations resulted in phenotypic changes that differed from the summed impacts of individual eGene perturbations (SI Figs. 25–27), reinforcing that polygenic risk cannot be extrapolated from experiments that test one risk gene at a time. Finally, we report that pharmacological manipulation of a convergent hub reversed the effects of multiple eGenes, suggesting that for polygenic disorders, a preferred therapeutic approach may be to target shared downstream effects rather than individual risk loci.

Altogether, the experimental eGene perturbations approximated the magnitude and direction of predicted eGene effect associated with schizophrenia, and generally resulted in downstream gene expression changes related to synaptic biology and psychiatric disorder risk. Nonetheless, further gene set enrichment analysis using 493 inflammation and cell death gene-sets46 revealed enrichments related to cell stress and neurodegenerative diseases across many perturbations (Supplementary Data 1). This enrichment was not seemingly associated with viral burden, being present whether single, combinatorial, or multiplexed vectors were applied. If our in vitro system, defined by repeated lentiviral transduction, antibiotic selection, eGene perturbation, and single cell dissociation, stressed human neurons more than accounted for by the scramble gRNA controls, this would represent a concern of relevance to all CRISPR experiments in human neurons. However, neither high content imaging nor multi-electrode array analyses indicated decreased cell survival or a cessation of neuronal activity (SI Figs. 26 and 27). Moreover, inflammation89 and oxidative stress90, and particularly fetal exposures to inflammation, stress, and hypoxia91,92 are indeed associated with schizophrenia risk.

Mapping GWAS associations to eGene targets is challenging and can yield false positives. How well our three eQTL-based methods prioritized causal eGenes remains a critical question, particularly in that they rely on tissue-specific eQTL data. There are frequent hotspots of multiple TWAS-associated genes in the same locus71, with co-regulation known to underlie pleiotropic TWAS associations93. Here, three eGenes were linked to a single SNP (rs3814883) in schizophrenia-associated copy number variant at 16p11.2, a locus that harbors the greatest excess of psychiatric common polygenic influences94. We posit that a causal GWAS SNP may co-regulate multiple adjacent and distal genes at this locus through chromatin contacts, but it is possible that one or more eGenes at this locus were misidentified. Other schizophrenia GWAS SNPs (e.g., rs2027349) likewise alter expression of multiple genes (VPS45, IncRNA AC244033.2 and a distal gene, C1orf54); indeed, combinatorial perturbation of these eGenes results in non-additive impacts on transcriptomic and cellular phenotypes28.

Given the extent of polygenicity associated with schizophrenia, our conclusions are constrained by the small proportion of eGenes tested here relative to the total number of eGenes impacted by schizophrenia GWAS loci. Technical limitations in testing a larger set of SCZ eGenes include the number of GWAS loci with accurately mapped gene targets; prediction and validation of gRNAs that reliably achieve physiologically relevant gene perturbations across donors and cell types; and the sequencing costs necessary to achieve sufficient gRNA representation to resolve perturbations at scale. Moreover, given that we selected only those schizophrenia eGenes with the very strongest evidence of genetically regulated gene expression, the generalizability of our observations to all schizophrenia eGenes is unclear, particularly if there are non-linear responses to gradual changes in gene dosage95. Thus, future investigation to test across larger gene sets, graded changes in expression95, in vivo brain regions9 and in vitro cell types96, developmental timespans97, drug/environmental contexts98 and donor backgrounds99 will inform the cell-type-specific and context-dependent nature of convergence and non-additivity. Of course, all of this must be considered within the caveat that in vitro perturbations do not exactly recapitulate the physiological impact of possessing multiple genetic variants in human cases and controls. Despite this, it is worth noting that the limited number of perturbations used in our combinatorial conditions is still broadly relevant to studies of common variant interactions. When analyzing the full dataset of 105 S-PrediXcan SCZ eGenes in the post-mortem adult DLPFC6, a median of ten and a maximum of 37 eGenes had outlying expression in the direction of risk association per individual (SI Fig. 17). Across the twenty-one SCZ eGenes targeted in either the pooled or arrayed experiments, a median of two and a maximum of eight eGenes had outlying expression in the direction of risk association per individual (SI Fig. 18). Of course, the present design also falls short of capturing nuances of pleiotropy, incomplete penetrance, and environmental factors.

Whereas population genetics finds very little evidence of non-additive effects in phenotypic variation, molecular biology unequivocally demonstrates the occurrence of gene-gene interactions100. To resolve this seeming contradiction, recall that although the “liability threshold model” assumes that disease risk reflects the total sum of many additive genetic (and/or environmental) effects, the relationship between predisposition and clinical outcome is necessarily binary101. Indeed, the cumulative effect of risk SNPs can exceed observed phenotypic variation. Thus, epistasis at the gene level is consistent with the additivity of complex traits102. Likewise, here we report that convergent perturbations at the pathway level correlated with predominantly sub-additive effects. Our findings indicate that the cumulative effect of gene perturbations is additive only until a downstream pathway is maximally perturbed, after which, additional perturbations yield reduced marginal effects. Our results further suggest that a pathway can be manipulated to the point of saturation effect with only a handful of genes. We posit that there may be many combinations of variants that have the same impact on a pathway. This is supported by emerging evidence of pathway polygenic risk score (PRS) burden103, whereby pathway PRS provided higher prediction power of [disease] than overall genome-wide risk, even in cases with low overall genetic risk104.

We further tested the extent to which our in vitro studies of CRISPR perturbations inform the polygenic architecture of schizophrenia at the population level. First, transcriptomic imputation of brain eGene expression (see Methods,) revealed a dose-dependent effect: schizophrenia case-control status (p < 0.01774, OR > 1.10) was best predicted when three or more eGenes were perturbed (OR3 eGenes = 1.47 vs. OR1 eGene = 1.10) (SI Fig. 1A). Second, transcriptomic risk scores (see Methods) indicated that schizophrenia risk was better predicted from larger (p < 2.2 × 10−16) (SI Fig. 1C) or more biologically diverse (R = 0.19, p < 2.2 × 10−16) (SI Fig. 1D) gene groups. Of note, there was a lack of individuals, either case or control, with strong imputed within-function perturbations, perhaps explaining why population-level schizophrenia risk increased with the number of genes and pathways impacted. Pathway-specific polygenic risk scores (PRSets105) that incorporate biological pathways, co-expression patterns, convergence, and/or non-additivity may improve patient stratification or better predict drug response; consistent with this, non-additive PRSets performed as well as those curated from synaptic genes (SI Fig. 24). Altogether, these studies of transcriptomic imputation and polygenic risk scores suggest that our in vitro studies of CRISPR perturbations indeed inform the polygenic architecture of schizophrenia in vivo.

How does our genetic analysis of convergence advance precision medicine for patients with psychiatric disorders? First, it may inform molecular subtypes of disease. For example, when we cluster individuals based on shared patterns of schizophrenia eGene up-regulation in the post-mortem DLPFC (SI Table 2), diagnosis of included individuals distinguished clusters (Pearson’s Chi-squared; X2 = 140, df = 21, p value = 9.51e-20) (e.g., cluster 8, SCZ, X2 = 3.286; cluster 12, affective disorders (AFF), X2 = 5.57; cluster 16, control, X2 = 3.014) (SI Figs. 31 and 32). A diagnosis of affective disorder (AFF) was significantly associated with up-regulation of FES, NAGA, CALN1, CLCN3, SF3B1 and ZNF804A (cluster 12). Convergence analysis across these six eGenes in iGLUTs identified the central node gene ABCG2, which is a biomarker associated with increased negative symptoms106, down-regulated in a neuroimmune molecular subtype (SCZ Type II)107,108, and associated with SCZ treatment resistance109. Second, points of convergence represent novel therapeutic targets that might be shared across cases; reversing the effects of even a small number of genomic variants could make a substantial difference to an individual’s risk of developing schizophrenia110. We predicted drugs capable of reversing convergent transcriptomic signatures and demonstrated that pharmacological targeting of convergent hubs ameliorated the effects of multiple schizophrenia eGene perturbations. We highlight statins, particularly simvastatin, which crosses the blood-brain barrier and shows promise as an add-on treatment in schizophrenia111. Two double-blind placebo-controlled trials of simvastatin highlighted the possibility that simvastatin may decrease negative symptoms in some patients112,113, potentially predictable based on inflammatory profiles114 and treatment-induced changes in insulin receptor levels115. Targeted shared convergent hubs potentially obviate the need to individually reverse the effects of multiple distinct risk loci in each patient.

That convergent genes were associated with a range of brain disorders indicated that convergent effects may partially explain shared features of psychiatric disorders and pleiotropy of risk. Consistent with this, common and rare risk variants for schizophrenia2,7,17,38,39,40,41,116,117,118, autism spectrum disorder119,120,121 and more broadly across the neuropsychiatric disorder spectrum30,122,123,124 are all highly enriched for genes involved in synaptic biology and gene regulation. Our findings support the hypothesis that common and rare psychiatric risk variants converge on the same biological pathways27. As recently demonstrated for autism125, by combining genetic and clinical data, it may be possible to resolve biologically distinct subtypes of schizophrenia. Our overarching goal is to advance the field towards an era of precision medicine126, whereby patient genetics, in conjunction with clinical evaluation, are used to more accurately predict diagnosis, disorder trajectory, and potential therapeutic interventions.

Methods

Statement of ethics

Yale University Institutional Review Board waived ethical approval for this work. Ethical approval was not required because the hiPSC lines, lacking association with any identifying information and widely accessible from a public repository, are thus not considered to be human subjects research. Post-mortem data are similarly lacking identifiable information and are not considered human subjects research.

Schizophrenia eGene prioritization

eGenes are defined as genes with significant genetic regulation of gene expression levels. In total, across the pooled and arrayed analyses, 20 unique eGenes were prioritized based on statistical and epigenetic evidence supporting genetic (dys)regulation of expression in schizophrenia (see Table 1), rather than GWAS or eQTL effect size; predicted direction and magnitude of eGene effect available in SI Table 1.

i) SCZ1 eGenes: EpiXcan68 was used to impute brain transcriptomes from Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 3 (PGC3)-SCZ GWAS2 at the level of genes and isoforms from the PsychENCODE post-mortem datasets of genotyped individuals (brain homogenate, n = 924)42,69; EpiXcan increases power to identify trait-associated genes under a causality model by integrating epigenetic annotation127 (from REMC128); transcriptomes were imputed at the gene and isoform levels and features with training cross-validation R2 ≥ 0.01 were retained. The epigenetic imputation models were built with the PrediXcan72 method (using a 50kbp window instead of 1Mbp for transcripts), utilizing the recently described ChIPseq datasets21; summary-level imputation was performed with S-PrediXcan70. Peaks were assigned to genes with the ChIPseeker R package129. In addition, PrediXcan72 imputed H3K27ac (brain homogenate, n = 122; neuronal, n = 191) and H3K4me3 (neuronal, n = 163)21 to more confidently identify cis-regulatory elements associated with risk for SCZ. Overall, SCZ eGenes were prioritized from GWAS based on: i) significant genetic up-regulation of expression (z-score >6 for genes), ii) epigenetic support (imputed epigenetic activity (p < 0.01) across at least one of the three assays), iii) exclusion of non-coding genes or those located in the MHC locus, iv) robust expression in our hiPSC neuron RNAseq. Genes were ranked based on the association z-score for imputed gene expression. For pooled experiments (day 7 hiPSC-derived iGLUT), six top coding genes and one top pseudo-gene were selected: NEK4, PLCL1, UBE2Q2L, NAGA, FES, CALN1, and ZNF804 (Table 1).

ii) SCZ2 eGenes: First, transcriptomic imputation (prediXcan70,71,72) identified ~250 significant genes (p < 6 × 10−6) with predicted differential expression between SCZ-cases and controls using SCZ GWAS2 and post-mortem CommonMind Consortium (CMC)6 data (623 samples). Second, colocalization (COLOC73,74) of fine-mapped PGC3-GWAS2 loci (65,205 cases and 87,919 controls) with post-mortem brain6 eQTL (537 EUR samples)6 identified 25 loci with very strong evidence (high posterior probability that a single shared variant is responsible for both signals, PP4 > 0.873). There was significant overlap between the two analyses (binomial test p value 3.03 × 10−112); of the 25 COLOC genes, 22 were also significant by PrediXcan. For each eGene, the magnitude and direction of perturbation associated with SCZ risk were predicted, and expression confirmed in hiPSC neuron RNAseq27. eGenes were further separated into discrete functional categories based on gene ontology annotations (http://geneontology.org/). From these 22, we prioritized the top coding genes across three broad categories: synaptic, regulatory, and multifunctional (defined as not synaptic, regulatory, and seemingly unrelated to each other). To complete the selection of five genes from each category, three additional top-ranked synaptic genes from the prediXcan analysis were included: DOC2A74, CLCN374 and PLCL1124. Overall, 15 SCZ eGenes were prioritized from GWAS based on i) significant genetic regulation by COLOC and/or PrediXcan, ii) exclusion of non-coding genes and those located in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) locus, iii) robust expression in our hiPSC neuron RNAseq.

For arrayed experiments (day 21 NPC-derived iGLUT), our final gene list for combinatorial perturbations included five synaptic genes (SNAP91, CLCN3, PLCL1, DOC2A, SNCA), five regulatory genes (ZNF823, INO80E, SF3B1, THOC7, GATAD2A), and five genes with non-synaptic, non-regulatory functions, termed “multi-function” (CALN1, CUL9, TMEM219, PCCB, FURIN) (Table 2). For pooled experiments (day 21 NPC-derived iGLUT), the ten coding genes with significant genetic up-regulation were selected: CALN1, CLCN3, CUL9, DOC2A, PLCL1, INO8E0, SF3B1, SNAP91, TMEM219, ZNF823. This list was combined with our eGene set previously evaluated in hiPSC-neurons27; one functionally validated gRNA was included for each of these three genes (SNAP91, TSNARE1, and CLCN3)27.

gRNA design

CRISPRa gRNA design and cloning were conducted as described previously130, using the lentiGuide-Hygro-mTagBFP2 backbone (Addgene, No. 99374). For the fifteen eGenes prioritized by a combination of COLOC and PrediXcan, we designed three gRNAs each. For the seven eGenes prioritized by EpiXcan and PrediXcan, we designed ten gRNAs each. For the three previously tested eGenes27 (intended as a positive control), we used one pre-validated gRNA each. All gRNA sequences and corresponding oligonucleotide sequences used for cloning of gRNA vectors and subsequent experimentation are listed in Supplementary Data 5.

iGLUT induction from hiPSC-derived NPCs27,58,59,60 or hiPSCs65,131

Validated control hiPSCs for eGene perturbation were selected from a previously reported case/control hiPSC cohort of childhood onset schizophrenia132. Informed consent was obtained from all fibroblast donors at the National Institute of Mental Health under the review of the Internal Review Board of the NIMH. All hiPSC work was reviewed by the Internal Review Board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. This work was also reviewed by the Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Yale University. The following control hiPSC/NPCs were used: NSB553-S1-1 (male), NSB2607-2/NSB2607-1-4 (male), NSB690-2 (male). All fibroblast samples were genotyped by IlluminaOmni 2.5 bead chip genotyping133,134, PsychChip132, and exome sequencing132. Parental hiPSCs were validated by G-banded karyotyping (Wicell Cytogenetics), with ongoing genome stability monitored by Infinium Global Screening Array v3.0 (Illumina). Critically, SNP genotype is inferred from all RNAseq data using the Sequenom SURESelect Clinical Research Exome (CRE) and Sure Select V5 SNP lists to confirm that neuron identity matches the donor.

i) Validated control hiPSC-derived NPCs for CRISPRa/shRNA were selected from a previously reported case/control hiPSC cohort of childhood onset SCZ (COS)132: NSB553-S1-1 (male, average SCZ PRS, European ancestry), NSB2607-1-4 (male, average SCZ PRS, European ancestry). hiPSC-NPCs were generated via dual-SMAD inhibition (0.1 µM LDN193189 and 10 µM SB542431) followed by neural rosette selection and MACS-based purification and validated as previously described)132. hiPSC-NPCs were subsequently transduced with lentiviral vectors for dCas9-VPR-puro (Addgene, No. 99373) and selected with 1 mg/mL puromycin (Sigma, no. P7255) as described previously132. hiPSC-NPCs expressing dCas9-VPR were cultured in hNPC media (DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies #10565), 1x N2 (Life Technologies #17502-048), 1x B27-RA (Life Technologies #12587-010), 1x Antibiotic-Antimycotic, 20 ng/ml FGF2 (Life Technologies)) on Matrigel (Corning, #354230).

At day −2, dCas9-VPR hiPSC-NPCs were seeded as 1.2 × 106 cells/well in a 12-well plate coated with Matrigel. At day −1, cells were transduced with rtTA (Addgene 20342) and NGN2 (Addgene 99378) lentiviruses. Medium was switched to non-viral medium four hours post-infection. At day 0 (D0), 1 µg/ml dox was added to induce NGN2-expression. At D1, transduced hiPSC-NPCs were treated with antibiotics to select for lentiviral integration (300 ng/ml puromycin for dCas9-effectors-Puro, 1 mg/ml G-418 for NGN2-Neo). At D3, NPC medium was switched to neuronal medium (Brainphys (Stemcell Technologies, #05790), 1x N2 (Life Technologies #17502-048), 1x B27-RA (Life Technologies #12587-010), 1 µg/ml Natural Mouse Laminin (Life Technologies), 20 ng/ml BDNF (Peprotech #450-02), 20 ng/ml GDNF (Peprotech #450-10), 500 µg/ml Dibutyryl cyclic-AMP (Sigma #D0627), 200 nM L-ascorbic acid (Sigma #A0278)) including 1 µg/ml Dox. 50% of the medium was replaced with fresh neuronal medium once every second day.

For pooled analysis, on day 5, young hiPSC-NPC NGN2-neurons were replated onto matrigel-coated plates and cells were dissociated with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies) for 5–10 min, washed with DMEM/10%FBS, gently resuspended, counted and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL in neuron media [Brainphys (StemCell Technologies #05790), 1 N2 (ThermoFisher #17502-048), 1 B27-RA (ThermoFisher #12587-010), 1 mg/ml Natural Mouse Laminin (ThermoFisher #23017015), 20 ng/mL BDNF (Peprotech #450-02), 20 ng/mL GDNF (Peptrotech #450-10), 500 mg/mL Dibutyryl cyclic-AMP (Sigma #D0627), 200 nM L-ascorbic acid (Sigma #A0278)] with doxycycline, puromycin, G418 [4 µM Ara-C (Sigma #C6645)] and 1 Thiazovivin (Sigma #420220). Cells were seeded 5 × 105 per 12-well plate. For arrayed analysis, neurons were not replated, owing to the complexity of the conditions involved.

At D13, iGLUTs were treated with 200 nM Ara-C to reduce the proliferation of non-neuronal cells in the culture, followed by half medium changes. At D18, Ara-C was completely withdrawn by full medium change while adding media containing individual shRNA/gRNA vectors or pools of mixed shRNA and gRNA vectors (Addgene 99374), either targeting eGenes or scramble controls. CRISPRa and shRNA vectors were specifically selected for perturbation due to the potential for simultaneous, bi-directional perturbation of target eGenes in joint perturbation conditions. shRNA knockdown was chosen over CRISPRi due to the difficulties in expressing multiple separate CRISPR effectors in the same cell lines (e.g., dCas9-VPR + dCas12a-KRAB). Control conditions were as follows: scramble gRNA vector (for comparing with target gRNA conditions), scramble shRNA vector (for comparing with target shRNA conditions) and scramble gRNA vector + scramble shRNA vector (for comparing with joint perturbation conditions). All control conditions were MOI-matched to their respective target condition. Medium was switched to non-viral medium four hours post-infection. At D19, transduced iGLUTs were treated with corresponding antibiotics to the gRNA lentiviruses (1 mg/ml HygroB for lentiguide-Hygro/lentiguide-Hygro-mTagBFP2), followed by half medium changes until neurons were harvested at D21.

ii) Clonal hiPSCs from two control donors of European ancestry (NSB690-2 (male, average SCZ PRS, European ancestry) and NSB2607-2 (male, average SCZ PRS, European ancestry)132 with lenti-EF1a-dCas9-VPR-Puro (Addgene #99373), pLV-TetO-hNGN2-eGFP-Neo (Addgene #99378), and lentiviral FUW-M2rtTA (Addgene #20342) were maintained in StemFlex™ Medium (ThermoFisher #A3349401) and passaged with EDTA (Life Technologies #15575-020). On day 1, induction media (DMEM/F12 (ThermoFisher #10565), 1 N2 (ThermoFisher #17502-048), 1 B27-RA (ThermoFisher #12587-010), 1 Antibiotic-Antimycotic (ThermoFisher #15240096), and 1 µg/mL doxycycline) was prepared and dispensed 2 mL of suspension at 1.2 × 106 cells/well in induction media onto a 6-well plate coated with Matrigel (Corning #354230). On day 3, media is replaced with induction medium containing 1 μg/mL puromycin and 1 mg/mLG418. On day 5, split neurons were replated onto matrigel-coated plates and cells were dissociated with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies) for 5–10 min, washed with DMEM/10%FBS, gently resuspended, counted and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL in neuron media [Brainphys (StemCell Technologies #05790), 1 N2 (ThermoFisher #17502-048), 1 B27-RA (ThermoFisher #12587-010), 1 mg/ml Natural Mouse Laminin (ThermoFisher #23017015), 20 ng/mL BDNF (Peprotech #450-02), 20 ng/mL GDNF (Peptrotech #450-10), 500 mg/mL Dibutyryl cyclic-AMP (Sigma #D0627), 200 nM L-ascorbic acid (Sigma #A0278)] with doxycycline, puromycin, G418 [4 µM Ara-C (Sigma #C6645)] and 1 Thiazovivin (Sigma #420220). Cells were seeded 5 × 105 per 12-well plate. On day 7, neurons were harvested for scRNA sequencing.

Neuronal pooled CRISPRa screens

Expanded CRISPR-compatible CITE-seq (ECCITE-seq)75, combines Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) and Cell Hashing for multiplexing and doublet detection135 with direct detection of sgRNAs to enable single cell CRISPR screens with multi-modal single cell readout. By capturing pol III-expressed guide RNAs directly, this approach overcomes limitations of other single-cell CRISPR methods, which detect guide sequences by a proxy transcript, resulting in barcode switching and lower capture rates136,137,138. CRISPRa hiPSC iGLUT neurons (2607 (male) and 690 (male)) were transduced with the pooled gRNA at day −1. After maturation, 7-day-old iGLUT neurons were dissociated into single-cell suspensions with papain, antibody-hashed135, and bar-coded single-cell cDNA generated using 10X Genomics Chromium139. NPC-derived iGLUT neurons (2607 (male) and 553 (male)) were transduced with the mixed-pooled gRNA vectors (Addgene 99374) at day 17. At day 21, media was replaced by 0.5 ml/well Accutase containing 10 μm Rock inhibitor, THX (catalog no. 420220; Millipore) for 1 hour to dissociate neurons. Neurons were spun down (3 mins × 300 g) and resuspended in DMEM/F12 + THX before proceeding to single cell sequencing. Analysis of single-cell CRISPRa screens in DIV 7 and DIV 21 iGLUT Neurons. mRNA sequencing reads were mapped to the GRCh38 reference genome using the Cellranger Software. To generate count matrices for HTO and GDO libraries, the kallisto indexing and tag extraction (kite) workflow was used. Count matrices were used as input into the R/Seurat package140 to perform downstream analyses, including QC, normalization, cell clustering, HTO/GDO demultiplexing, and DEG analysis75,141.

Normalization and downstream analysis of RNA data were performed using the Seurat R package (v.2.3.0), which enables the integrated processing of multimodal single-cell datasets. Each ECCITE-seq experiment was initially processed separately. Cells with RNA UMI feature counts were filtered (200 <nFeature_RNA < 8000), and the percentage of all the counts belonging to the mitochondrial, ribosomal, and hemoglobin genes calculated using Seurat::PercentageFeatureSet. Hashtag and guide-tag raw counts were normalized using centered log ratio transformation, where counts were divided by the geometric mean of the corresponding tag across cells and log-transformed. For demultiplexing based on hashtag, Seurat::HTODemux function was used; and for guide-tag counts Seurat::MULTIseqDemux function within the Seurat package was performed with additional MULTIseq semi-supervised negative-cell reclassification. In both experiments, 8-10% of retained cells contained multiple gRNAs and were assigned as doublets after de-multiplexing. To remove variation related to the cell-cycle phase of individual cells, cell cycle scores were assigned using Seurat::CellCycleScoring, which uses a list of cell cycle markers142 to segregate by markers of G2/M phase and markers of S phase. RNA UMI count data were then normalized, log-transformed, and the percent mitochondrial, hemoglobulin, and ribosomal genes, batch, donor (HTO-maxID; as a biological replicate), and cell cycle scores (Phase) were regressed out using Seurat::SCTransform. The scaled residuals of this model represent a ‘corrected’ expression matrix, that was used for all downstream analyses. To ensure that cells assigned to a guide-tag identity class demonstrated successful perturbation of the target gene, we performed ‘weighted-nearest neighbor’ (WNN) analysis, to assign clusters based on both guide-tag identity class and gene expression76. To identify successfully perturbed cells, we calculated a p value based on the Wilcox rank sum test and Area Under the Curve (AUC) statistic, which reflects the power of each gene (or gRNA) to serve as a marker of a given cluster using Presto. WNN Clusters were then filtered based on two criteria (1) single gRNA-identity with an AUC statistic of ≥ 0.8 (where 1 means the gRNA is a perfect marker of a given cluster) and (2) a logFC ≥ 2 standard deviations of the mean or logFC > 0 and p-val > 0.05, of the target gene (but no other target genes) compared to scramble (non-targeting sgRNAs) controls (SI Fig. 4−8). These clusters were then used for downstream analyses143.

Of note, there was a lower representation of specific gRNAs and fewer gene perturbations resolved in SCZ2 than SCZ1. This likely reflected the use of a single pre-validated gRNA vector per gene from our arrayed experiments for SCZ2, rather than a pooled library comprised of multiple gRNAs targeting each eGene in SCZ1.

Cell fraction imputation and quantification of heterogeneity in the composition of iGLUT neurons

Using CiberSortx, we imputed the cell-faction identity of randomly sampled scramble control cells from each experiment (n = 100/exp) using the PsychEncode scRNAseq dataset as a reference (100 permutations). To determine if the level of heterogeneity of iGLUT neuron maturity and subtype was similar between DIV7 and DIV21 iGLUT neurons in the given experiments, we performed a non-parametric Levene’s Test for Homogeneity of Variance (LT-test) on the imputed cell fraction matrices. Although we observed heterogeneity in relative central and peripheral nervous system marker expression across the cell fractions, this heterogeneity was not due to gRNA identity, and the level of variance in our data due to cellular heterogeneity was not significantly different by time-point. We were underpowered to compare gRNAs between cells with higher expression of different cell markers.

Meta-analysis of gene expression across perturbations144

We performed a meta-analysis and Cochran’s heterogeneity Q-test (METAL77) using the p values and direction of effects (t-statistic), weighted according to sample size across all sets of perturbations in both the arrayed and pooled assays (Target vs. Scramble DEGs). Genes were defined as “convergent” if they (1) had the same direction of effect across all 5, 10, or 15 target combinations, (2) were Bonferroni significant in our meta-analysis (Bonferroni adjusted p value ≤ 0.05), and (3) had a heterogeneity p value = >0.05.

Bayesian Bi-clustering to identify target-convergent networks144

eGene-Convergent gene co-expression Networks (eGCN)81 were built using an unsupervised Bayesian biclustering model, BicMix145, on the log2CPM expression data from all the replicates across each of the 5-target sets and scramble gRNA jointly or all the cells across 10 targets and scramble gRNA jointly for the arrayed and pooled assays, respectively. To account for neuronal maturity differences in the single-cell screen, expression matrices were batch corrected and normalized, and the scramble cells from both experiments (matched scramble gRNA across experiments) were used as a single control population. To perform this as a joint analysis across two experiments, (1) Count matrices from each experiment were combined and RNA transcripts, mitochondrial, ribosomal, and hemoglobin genes were removed ([‘^MT- | ^RP[SL][[:digit:]]|^RPLP[[:digit:]]|^RPSA | ^HB[ABDEGMQZ][[:digit:]]’) as well as genes that had at fewer than 2 read counts in 90% of samples, (2) and limma:voom normalization and transformation was used to compute the log2cpm counts from the effective library sizes of each cell (16851 genes). 40 runs of BicMix were performed on these data, and the output from iteration 400 of the variational Expectation-Maximization algorithm was used. The hyperparameters for BicMix were set based on previous extensive simulation studies146. Convergent networks were identified across all possible combinations of 2–14 as well as all 15 of the targets (n = 32752 combinations) in the arrayed assay, and all possible combinations of 2,3,4,5,6,7 or 8 as well as all 10 of the targets (n = 1003 combinations) in the pooled experiment. Network connections that did not replicate in more than 10% of the runs were excluded. Nodes with fewer than 5 edges or non-coding genes were removed from gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). (The threshold of >5 edges is based on the likelihood of more than 5 edges being present by chance, with 10% being the percentage of runs where the connection was identified, see refs. 81,145. Duplication thresholds are network-dependent, and a metric of confidence in the connections, including those with especially low duplication rates, was not included in downstream analysis.) Of all random sets tested in the pooled experiment, 64.8% resolved a convergent network passing at least a 10% duplication threshold; of all random sets tested in the arrayed experiment, ~50% resolved a convergent network with a 5–255 threshold of duplication depending on the node-edge connection. Using FUMAGWAS: GENE2FUNC, the protein-coding genes were functionally annotated, and overrepresentation gene-set analysis for each network gene set was performed147. Using WebGestalt (WEB-based Gene SeT AnaLysis Toolkit)148, over-representation analysis (ORA) was performed on all convergent network gene sets against a curated list of common and rare variant target genes across ASD, BIP, SCZ, and ID27. Nodes were annotated using GeneCards149, MalaCards150, and GWAS Catalog151. Specific enrichments were observed with 1’ de novo SCZ-CNV152, SCZ eQTLs153, SCZ brain hub gene106, downregulated in ASD/WS154, SCZ neurons155, and Sox21 neural patterning156.

Influence of Functional Similarity on Convergence Degree

Functionally similarity scores across the eGenes represented in each set was calculated using three metrics: (1) Gene Ontology Scores: the average semantic similarity score based on Gene Ontology pathway membership (within Biological Pathway (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF) between genes in a set80, (2) Brain expression correlation (B.E.C.) score: based on the strength of the correlation in gene expression in the CMC (n = 991 after QC) post-mortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) gene expression data6, and (3) Signaling Score: based on the proportion of eGenes whose basic functional annotation was categorized as “signaling” (CALN1, CLCN3, FES, NAGA, PLCL1, TMEM219; with PLCL1 and CLCN3 further separated as specific synaptic genes) or four “epigenetic/regulatory” target genes (SF3B1, UBE2Q2L, ZNF823, ZNF804A; with ZNF823, ZNF804A as specific transcription factors) using FUMAGWAS: GENE2FUNC147 (SI Fig. 10).

Bi-clustering identifies co-expressed genes shared across the downstream transcriptomic impacts of any given set of eGene perturbations, thus, the resolved networks are the transcriptomic similarities between distinct perturbations (convergence). While bi-clustering resolves convergent gene co-expression networks, the strength of convergence within a network can be defined by (i) the degree of network connectivity as defined by two small-world network connectivity coefficients (edge density and average path length) and (ii) the degree of functional similarity or unity between genes represented within the network. Given this definition, (1) represents perturbations with no convergent downstream effects, (2) represents a network with a moderate degree of convergence because it (i) has resolved gene co-expression clusters that can be constructed into a network, (ii) has a moderate degree of network connectivity and (ii) is enriched in biological pathways with some redundancy, while (3) represents a highly convergent network because the degree of network connectivity is stronger and there is greater uniformity in biological pathway gene membership. Overall, we quantify the strength or degree of convergence using the function in (4), where Cp is the edge density (the proportion of edges present given all possible edges) and Lp is the average path length (the mean of the shortest distance between each pair of nodes), MFsc is the average semantic similarity score between each pair of nodes in the network based on Molecular Function Gene Ontology, BPsc is the average semantic similarity score based on Biological Pathway Gene Ontology and CCsc is the average semantic similarity score based on Cellular Component Gene Ontology. Semantic similarity is based on the idea that genes with similar function have similar Gene Ontology annotations. Semantic similarity scores were calculated by aggregating four information content-based methods and one graph structure-based method with the R package GoSemSim.

We assigned each network a “degree of convergence” based on (1) network connectivity and (2) similarity of network genes based on biological pathway membership. We performed a principal components analysis on the functional similarity scores and the degree of network convergence. PCA loadings determined the effect of the included variables on the variability across all resolvable sets (arrayed=16320, pooled=827, variables=6). To quantify this, we calculated two small-world connectivity network coefficients: the cluster connectivity coefficient based on the proportion of edges present out of all possible edges (Cp) and the average path length (Lp)157.

Here, we define convergence as (1) increased connectivity of the resolved networks and (2) functional similarity of genes within the network. Network connectivity was defined by the sum of the clustering coefficient (Cp) and the difference in average length path (Lp) from the maximum average length path resolved across all possible sets [(max)Lp-Lp]. Network functional similarity was scored by taking the sum of the mean semantic similarity scores between all genes in the network. Overall, convergence degree represented the sum of the network connectivity score and the network functional similarity score (1):

Convergent networks with matched patterns of gene expression in the post-mortem brain

We clarify that this approach asks how often eGenes are up-regulated together in individual post-mortem brains. To do this, we ran target-convergent network reconstruction in our scRNA-seq data, not the CMC bulk tissue data, for sets of eGenes defined by the clustering observed in the CMC bulk tissue data. We found zero individuals in the CMC data with significant upregulation of all ten risk eGenes. Instead of only evaluating convergence on the basis of eGene functional similarity as in the first portion of the manuscript, we define eGene pairings more broadly based on the signatures of these eGenes in the post-mortem DLPFC, increasing the relevance to risk at the individual level. Target sets based on gene expression patterns in the CMC (n = 991 after QC) post-mortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). We performed K-means clustering to subset the data into clusters based on the Z-scored gene expression of the 10 target genes. Although initial silhouette analysis identified the optimal number of clusters as two, visualization by a scree plot suggested the optimal number to be between 4 and 6 clusters. Given that data clustered by case/control status (2 clusters), and sub-diagnosis of BP, SCZ, AFF, and Controls (4 clusters), to assess clustering based on 10 eGenes, we tested the impact of using 10 clusters and 20 clusters (SI Fig. 32). Perturbation identities were assigned based on average positive Z-scores of ≥0.5 within each cluster. We then assigned our single-cell data to clusters based on the overlap of perturbations and performed network reconstruction to replicate our convergent analysis using groups based on CMC post-mortem data. We retained clusters that resolved networks with at least a 10% duplication rate, calculated convergence scores, and performed GSEA using protein-coding network genes. Of the twenty clusters, networks were recovered for the combination of targets represented in cluster 4 (2 targets; 913 cells; 15% duplication; 13 node genes), cluster 5 (3 targets; 1260 cells; 15% duplication; 13 node genes), cluster 6 (6 targets; 2035 cells; 15% duplication; 34 node genes), cluster 9 (6 targets, 1822 cells, 20% duplication, 108 node genes), cluster 11 (5 targets; 1640 cells; 15% duplication; 25 node genes), cluster 12 (6 targets; 2357 cells; 20% duplication, 152 node genes), cluster 13 (5 targets; 1741 cells; 17.5% duplication, 17 node genes), cluster 18 (6 targets; 1884 cells, 15% duplication, 25 nodes), cluster 19 (6 targets, 2327 cells, 20% duplication, 153 nodes), cluster 20 (6 targets, 2015 cells, 20% duplication, 33 nodes), while low confidence convergence was resolved for cluster 1 (5 targets, 1600 cells; 7.5% duplication; 38 node genes), cluster 8 (3 targets, 1233 cells, 7.5% duplication, 38 node genes), cluster 14 (3 targets, 1020 cells, 5% duplication, 23 nodes) and 16 (4 targets, 1177 cells, 2.5% duplication, 16 nodes). To determine if convergent networks were distinct between diagnostic groups, we first performed a Pearson’s chi-squared test to determine whether there was a significant difference between the expected frequencies and the observed frequencies in the diagnosis of AFF, BIP and SCZ within the clusters and then calculated Jaccard Similarity Indices between clusters based on convergent network gene membership.

Drug prioritization based on perturbation signature reversal in LiNCs Neuronal Cell Lines

To identify drugs that could reverse the resolved convergent perturbation signature across all ten targets, and within each target individually, we used the Query tool from The Broad Institute’s Connectivity Map (Cmap) Server. Briefly, the tool computes weighted enrichment scores (WTCS) between the query set and each signature in the Cmap LINCs gene expression data (dose, time, drug, cell-line), normalizes the WRCS by dividing by the signed mean w/in each perturbation (NCS), and computes FDR as fraction of “null signatures” (DMSO) where the absolute NCS exceeds reference signature158. We prioritized drugs that reversed signatures specifically in neuronal cells (either neurons (NEU) or neural progenitor cells (NPCs) with NCS ≤ −1.00) and filtered for (i) drugs that cross the blood-brain barriers, (ii) drugs that target genes expressed in iGLUT neurons based on bulk RNA-sequencing data from our lab and (ii) drugs that are currently launched or in clinical trial according to the cMAP Drug Repurposing database and without evidence of neurotoxicity (Box 2).

CRISPRa/shRNA validation27