Abstract

Radiotherapy can both activate and suppress immunity, making it difficult to predict or modulate these opposing effects for better cancer treatment. Boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT), a cellular-level radiotherapy, has demonstrated remarkable therapeutic efficacy in clinical practice, but mechanistically remains inadequately explored. Here, we compare the effects of BNCT with X-ray irradiation at equivalent radiation doses on immune cells and define the immunological mechanisms behind the improved therapeutic benefit of BNCT in mouse tumour models. We find that BNCT has a minimal effect on immune cell viability, while it triggers an immunogenic tumour cell death, ultimately inducing stronger anti-tumour immunity. Additionally, single-cell RNA sequencing indicates that BNCT reshapes the tumour microenvironment by enhancing dendritic cells, T cells, and NK cells activity. Thus, these findings provide important insights into radiobiological mechanisms following BNCT and inform strategies to preserve immune cells during radiotherapy and to increase cancer treatment efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The remodelling of the tumour immune microenvironment induced by radiotherapy is currently garnering extraordinary attention1,2,3, as it can enhance anti-tumour immune responses but, in some cases, also exerts immunosuppressive effects4. The response status of various immune cells plays a pivotal role in shaping treatment outcomes, yet these cells are inherently highly radiosensitive5. Over the past few decades, despite remarkable advancements in the precision of radiation delivery, whether using X-rays, proton beams, or heavy ions, collateral damage to immune cells within tumour tissues has remained an unavoidable challenge. Low-dose radiotherapy modulates immune cell infiltration but compromises tumour control6. Conversely, high-dose radiotherapy achieves more effective tumour ablation but at the expense of rapid immune cell depletion7. Although high-dose regimens can induce immunogenic cell death, the concurrent loss of immune cells often constrains the potential to activate antigen-presenting cells and tumour-specific T cells6. Thus, the ability to eradicate tumour cells while sparing immune cells represents an attractive but elusive goal, which is a dilemma to balance.

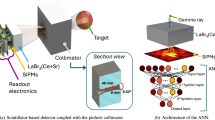

Boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) is theoretically regarded as a binary-targeted radiotherapy with the potential for single-cell precision killing8,9,10. When boron-10 accumulates in tumour cell and captures low-energy (~0.025 eV) thermal neutron, it undergoes nuclear capture, resulting in a 10B(n,α)7Li lethal reaction that produces high linear energy transfer (LET) α particle (150 keV/µm) and lithium-7 nucleus (175 keV/µm) with track lengths of only 5–9 μm. Based on this physical principle, BNCT has been hypothesised to selectively destroy tumour cells while sparing neighbouring normal and immune cells in the tumour microenvironment. The combination of high-LET effectiveness and minimal bystander range gives BNCT the distinctive feature of “tumour cell precision blasting”, which may provide a unique radiotherapeutic strategy that simultaneously achieves tumour ablation and immune cell preservation, contributing to the excellent therapeutic effects.

Encouragingly, BNCT has shown remarkable efficacy in clinical trials, particularly in patients with inoperable malignant tumours11, such as head and neck cancer12,13, glioblastoma multiforme14,15,16,17, and malignant melanoma18,19,20,21. In 2020, BNCT received clinical approval to treat locally advanced or recurrent unresectable head and neck cancer, marking a significant milestone. In real-world clinical practice, the objective response rate has reached 80.5%, and the 1-year overall survival rate is 75.4%22, substantially outperforming traditional treatment options23,24. And a single treatment session is typically sufficient, offering convenience to patients. These impressive outcomes raise important questions regarding the biological basis for the therapeutic advantage of BNCT. However, despite the promising clinical outcomes, the underlying radiobiological mechanisms of BNCT remain insufficiently explored. The concept of BNCT as a single-cell radiotherapy strategy has largely remained theoretical, with limited direct biological evidence to support immune cell sparing in vivo. Moreover, although preliminary reports suggested the possibility of abscopal effects with BNCT25, they failed to explain the immunological mechanisms. Neither the occurrence of BNCT-induced immune activation nor its underlying mechanisms has been systematically investigated, limiting its broader integration into mainstream clinical practice.

In this study, we take a step forward in addressing this gap by providing direct experimental evidence for the single-cell radiotherapy concept and by elucidating the immune mechanisms engaged by BNCT. We demonstrate that BNCT achieves tumour cell-selective killing while avoiding damage to immune cells and triggers immunogenic tumour cell death, thereby enabling robust activation of systemic anti-tumour immunity with long-term memory. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of BNCT-treated hot and cold tumours reveals enhanced antigen processing and presentation by dendritic cells, increased CD8+ T-cell activity, and augmented NK-cell cytotoxicity, and we identify CD8+ T cells as essential mediators of BNCT-induced tumour eradication. Together, these findings establish the immunological significance of BNCT and provide a rationale for preserving immune cells as a mechanistic driver of improved therapeutic benefit.

Results

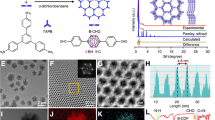

BNCT triggers robust systemic anti-tumour immunity and shapes immunological memory

BNCT is a type of cellular-level radiotherapy (Fig. 1a,b). Malignant melanoma is a clinical indication for BNCT. In this study, we used B16F10 cells, a highly metastatic murine melanoma cell line. B16F10 tumour models were constructed, which are commonly used as a classic model of immunologically cold tumours in tumour immunology26, characterized by an immunosuppressive profile. In addition, we have established an immunologically hot tumour model using the MC38 murine colorectal cancer cell line. With its relatively shallow location, colorectal cancer also shows potential as a suitable candidate for BNCT.

a Principle of the 10B(n,α)7Li reaction. b Principle of boron neutron capture therapy compared with X-ray radiotherapy. X-ray radiation non-selectively kills cells, causing immune cell dysfunction and increasing the potential risk of cancer recurrence. BNCT selectively kills boron-containing cancer cells while sparing the surrounding healthy tissue, especially immune cells. DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns. c–h Abscopal effect assay. c, f Treatment schemes for the B16F10 (c) and MC38 tumour models (f). C57BL/6J mice, 6–8-week-old, female, n = 6 mice for each group tested. d, e Average tumour volume of irradiated (d) and non-irradiated B16F10 tumours (e). NC, negative control. g, h Average tumour volumes of irradiated (g) and non-irradiated MC38 tumours (h). The green line showed the tumour growth curve in the non-irradiated regions of mice without right-side tumour implantation but with identical boron injection and neutron irradiation. i–m Tumour vaccination assay. i Treatment scheme. Average tumour volume (j) and survival fraction (k) of each group of B16F10-bearing mice (n = 5 mice for each group tested), two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, NC vs BNCT, **p = 0.0060, X-ray (4 Gy) vs BNCT, **p = 0.0020. Average tumour volume (l) and survival fraction (m) of each group of MC38-bearing mice (n = 5 mice for each group tested), two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, *p = 0.0274, ****p < 0.0001. n–q Tumour rechallenge assay. n Treatment scheme. Average tumour volume (o) and survival fraction (p) of each group of MC38-bearing mice (n = 5 mice for each group tested). NC-R, right tumour of the negative control group; BNCT-R, right tumour of the BNCT group; NC-L, rechallenged left tumour of the negative control group; BNCT-L, rechallenged left tumour of the BNCT group. q Quantification of naïve (CD44lowCD62Lhigh), central memory (CD44highCD62Lhigh, Tcms), and effector memory (CD44highCD62Llow, Tems) CD8+ T cells in the blood. n = 5 mice for each group tested, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, *p = 0.0250, *p = 0.0380, and *p = 0.0476, respectively. The data are the means ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The boron carrier agents for BNCT need to meet the following requirements: high tumour uptake ( > 20 ppm), high tumour selectivity (tumour to normal tissue ratio > 3), and low toxicity27,28,29. [10B]BPA (boronophenylalanine)30,31, an approved drug, is the most widely used boron carrier agent in clinical practice. At the cellular level, BPA resulted in high tumour cell uptake (Supplementary Fig. 1a). In vivo, boron uptake in the B16F10 and MC38 tumour tissues was 7.74 ppm and 12.60 ppm, respectively, one hour after intravenous injection of 100 mg/kg [10B]BPA (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c).

First, we tested the efficacy of BNCT in these two models. The average therapeutic doses were 4.395 Gy for the B16F10 tumour model and 4.029 Gy for the MC38 tumour model, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Following anaesthesia, the mice were positioned in a specialized mold, with the tumours near the neutron beam, for 30 min of neutron irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 1e). X-ray (4 Gy) external irradiation was used as a control group, BNCT significantly inhibited the growth of B16F10 tumours (Supplementary Fig. 1g,h), and completely cured MC38 tumours (Supplementary Fig. 1i,j), indicating that BNCT is highly effective in treating both tumours.

Given the theoretical basis for the ability of BNCT to preserve immune cells, we next investigated the anti-tumour immune effect of BNCT. Abscopal effects were assessed, and tumour cell vaccines and rechallenge models were established to explore the anti-tumour immunity induced by BNCT. These models have also been used to assess immunogenic cell death (ICD) in immunocompetent syngeneic systems in vivo32,33. Localized radiotherapy may lead to distant, non-irradiated tumour regression, known as the abscopal effect, which has been connected to immune system-mediated mechanisms34,35. B16F10 or MC38 tumours were implanted in the right shoulder of each mouse, and half of the tumour cells from the same source were implanted in the left lower abdomen. Seven or ten days later, BNCT treatment was applied, with only the shoulder tumour exposed to the thermal neutron beam (Fig. 1c,f). In both models, BNCT inhibited the growth of the distal tumour, not just the primary tumour, whereas 4 Gy localized X-ray treatment did not affect the distal tumour (Fig. 1d,e,g,h). Notably, even with the same BPA injection and neutron irradiation on the right shoulder, the growth of the distal tumour was not suppressed without the primary tumour (Fig. 1h). These findings suggested that the BNCT-treated tumour induced secondary effects that inhibited the distal tumour.

Whether BNCT-treated tumour cells could function as tumour vaccines was further investigated. The cells were incubated overnight with 10 mM BPA, irradiated with thermal neutrons for 10 min (Supplementary Fig. 1f), and injected into the mice. Ten days later, untreated tumour cells were implanted in the contralateral site (Fig. 1i). Preinjection of BNCT-treated B16F10 cells delayed the growth of secondary tumours (Fig. 1j) and prolonged the survival of tumour-bearing mice (Fig. 1k). BNCT-treated MC38 cells completely suppressed the growth of the second tumour (Fig. 1l) and allowed the mice to remain healthy (Fig. 1m). These results demonstrated that BNCT could convert irradiated tumour cells into an immunogenic hub and help tumour cells become more visible to the immune system.

Rechallenge experiments were performed to further investigate whether BNCT could promote long-term immune memory (Fig. 1n). MC38 tumour cells were inoculated on the right side of the mouse and treated with BNCT. After 10 weeks, the mice were subjected to a second tumour challenge on the left side. As shown in Fig. 1o, BNCT treatment completely suppressed secondary tumours, and the mice survived longer (Fig. 1p). Even in the rechallenge experiment conducted at week 20, BNCT treatment still completely inhibited tumour growth (Supplementary Fig. 1k,l). Moreover, in the treatment group at 10 weeks post-treatment, the percentage of naïve CD8+ T cells decreased, the percentage of central memory T cells (Tcm) among CD8+ T cells increased from 19% to 26%, and the percentage of effector memory T cells (Tem) significantly increased from approximately 7% to 12% when compared with those in the control group (Fig. 1q, Supplementary Figs. 1m,2). A similar trend was also observed in the axillary lymph nodes and spleen (Supplementary Fig. 1n–q). These findings suggested that BNCT could prime systemic anti-tumour immunity with durability and had the potential immunological benefits by inducing ICD to reduce the systemic disease burden.

BNCT evokes enhanced immunogenic cell death

To gain insight into the immunogenic cell death induced by BNCT, we characterized the properties of BNCT-treated tumour cells and molecular markers. First, we investigated the morphological changes following BNCT treatment, shown in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3a, b. The cells swelled 96 h after BNCT treatment in vitro, a phenomenon that was not prominent within the initial 48 h (Supplementary Fig. 3c). In addition, BNCT-treated MC38 cells displayed fragmentation, with abundant cell debris observed in the culture medium. By contrast, cells exposed to X-ray irradiation demonstrated only minimal morphological alterations. Cell viability assays via CCK-8 revealed significant cytotoxic effects of BNCT on both cell types (Fig. 2b,c). Notably, this cytotoxicity was not immediate; a reduction in cell viability to approximately 50% required 72–96 h. The morphological changes in tumour tissues treated with BNCT in vivo were consistent with those observed in vitro. Five days post-treatment, the tumour tissues exhibited a loose structure with reduced cellular integrity (Fig. 2d). Certain regions displayed more severe cell damage, characterized by a “reticular” structure in cell arrangements (Fig. 2e). Compared with the NC and X-ray groups, the BNCT-treated tumours presented significantly larger average cell sizes (Fig. 2f), progressively increasing intercellular spaces (Fig. 2g), reduced cell density (Supplementary Fig. 3d), and enlarged nuclear areas (Supplementary Fig. 3e). The changes in intercellular spaces and cell density became more pronounced over time, reflecting the progressive disruption of tumour architecture by BNCT. In addition, transmission electron microscopy revealed clear evidence of structural disruption of mitochondria in BNCT-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). JC-1 staining revealed that the aggregate to monomer ratio decreased in BNCT-treated B16F10 cells and MC38 cells compared with controls (Supplementary Fig. 3f–h), indicating a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. This decrease was consistent with the morphological changes observed by electron microscopy, suggesting mitochondrial dysfunction induced by BNCT.

a Cell morphology of tumour cells 96 h after treatment in the negative control (NC), X-ray (4 Gy), or BNCT groups. The red dashed lines outline the cell boundaries. The arrows indicate fragments from the lysed cells. Scale bar, 50 μm. Cell viability of B16F10 cells (b) or MC38 cells (c), n = 6 independently tested cell samples for each group. Two-way ANOVA analysis, B16F10 cells: *p = 0.0378, ***p = 0.0002, ****p < 0.0001. MC38 cells: *p = 0.0218, ***p = 0.0002. d Cell morphology within tumour tissue after treatment at days 1, 3, and 5 from the MC38-bearing C57BL/6J mice (6–8-week-old, female). e Representative areas of severe damage 5 days after BNCT treatment. Scale bar, 50 μm. Average cell area (f) and intercellular area (g) in tumour sections. n = 6 mice for each group tested. Two-way ANOVA analysis. Extracellular ATP levels of B16F10 cells (h) or MC38 cells (i) in vitro. n = 5 independently tested cell samples for each group. Two-way ANOVA analysis, B16F10 cells, NC vs BNCT, 60–96 h: **p = 0.0024, *p = 0.0235, ***p = 0.0008, **p = 0.0092; X-ray vs BNCT, 60-96 h: **p = 0.0058, *p = 0.0317, **p = 0.0020, ***p = 0.0007. MC38 cells, NC vs BNCT, 48–84 h: **p = 0.0011, ***p = 0.0003, **p = 0.0045, *p = 0.0148; X-ray vs BNCT, 48–84 h: **p = 0.0110, ****p < 0.0001, *p = 0.0239, *p = 0.0323. j, Representative immunofluorescence images of tumour samples. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) and an antibody against HMGB1 (green). Scale bar, 50 μm. k Quantification of relative HMGB1 green fluorescence per cell. n = 7 mice for each group tested. Two-way ANOVA analysis. l, m, Serum IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ levels of B16F10-bearing mice (l) or MC38-bearing mice (m), n = 5 mice for each group tested. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. The data are the means ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

BNCT has been demonstrated to elicit a systemic anti-tumour immune response, suggesting that the death of tumour cells is an immunogenic form of cell death. We scrutinized ICD markers at the cellular and molecular levels to substantiate this, focusing on damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)32,33,36. Extracellular ATP acts as a “find-me” signal that recruits DCs and macrophages, promoting proinflammatory responses33. Following BNCT treatment, the extracellular ATP levels in B16F10 cells (Fig. 2h) and MC38 cells (Fig. 2i) gradually increased relative to those in the control group, peaking at ~84 h and 60 h, respectively. At the peak, ATP levels in the culture medium of the BNCT group were approximately four times greater than those in the untreated control group and two times greater than those in the X-ray group, demonstrating that BNCT triggered ATP release, a conserved observation across both B16F10 and MC38 cells. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1), which can mediate potent immunostimulatory effects33, was also evaluated. Compared with those in the NC group, the HMGB1 expression and cytoplasmic accumulation in tumour cells were significantly greater in vivo at days 1, 3, and 5 post-BNCT (Fig. 2j,k), whereas X-ray treatment only slightly elevated HMGB1 levels (Fig. 2j,k). In contrast, calreticulin exposure was not significantly induced after BNCT (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). We subsequently evaluated interferons (IFN) in mouse serum, which were critical immunostimulatory molecules. In B16F10 tumour-bearing mice, there was a trend toward increased expression of IFN-α/β/γ after BNCT treatment on day 7 (Fig. 2l). Similarly, in MC38 tumour-bearing mice, BNCT significantly elevated the serum levels of IFN-α/β/γ on day 5, with IFN-α levels increasing by more than 10-fold (Fig. 2m). The upregulation of ATP release, HMGB1 expression, and interferon level collectively further confirmed that BNCT induces immunogenic cell death in tumour cells.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are recognised as the critical mechanism underlying the cytotoxic effects of high LET particles, including α particles. We observed a significant increase in DSBs in the BNCT group compared with those in the NC group (Supplementary Fig. 4c,d). At 1-, 3-, and 5 days post-treatment, the fold increases in DSBs for the BNCT group were 149, 211, and 205, respectively, whereas for the X-ray group, the corresponding values were 90, 30, and 2, respectively. These findings indicated that the DNA DSBs induced by BNCT were more severe and persistent, remaining irreparable for at least 5 days, distinguishing them from the transient effects observed with X-ray therapy. This finding was further supported by western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4e). In vitro experiments revealed that BNCT induced cell cycle arrest, which began 12 h after treatment and persisted for up to 96 h (Supplementary Fig. 4f–h). We further explored the mechanisms underlying BNCT-induced cell death (Supplementary Fig. 4i,j) compared to X-ray radiation (Supplementary Fig. 4k,l). The inhibition of caspase proteins failed to rescue the cell death induced by BNCT, whereas pan-caspase inhibitors were able to rescue some cells from death under X-ray irradiation. Similarly, inhibitors of necroptosis and ferroptosis could not prevent cell death caused by BNCT. These results indicated that BNCT-induced cell death was not associated with apoptosis, necroptosis, or ferroptosis. Given the characteristics of BNCT-induced cell death, such as cellular swelling, increased intercellular spacing, reduced cell density, persistent and irreparable DNA double-strand breaks, and prolonged cell cycle arrest, we hypothesized that the mode of cell death triggered by BNCT might be necrosis.

BNCT preserves and recruits immune cells within the tumour microenvironment

BPA is an analogue of phenylalanine, which is taken up mainly through L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1), which is encoded by the Slc7a5 gene and is overexpressed in many tumour cells37,38,39,40. Thus, boron selectively accumulates in tumour cells but remains scarce in immune cells. When exposed to the neutrons, tumour cells are far more likely to undergo boron neutron capture reactions than immune cells are, enabling precise tumour-cell killing while sparing immune cells (Fig. 3a).

a Principle of boron neutron capture therapy to preserve immune cells while killing tumour cells. The expression level of the Slc7a5 gene in sorted CD45- non-immune cells and CD45+ immune cells from B16F10 tumours (b) or MC38 tumours (c) was determined via quantitative PCR (n = 5 mice for each group tested, C57BL/6J mice, 6–8-week-old, female, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, ****p < 0.0001). d The distribution of boron-10 (m/z = 209.122) in MC38 tumour sections visualised by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF). Left, bright-field image. Right, MALDI-TOF imaging. The arrows indicate the regions with blood flow, in which immune cells are enriched. Color bar was normalized to the 99th percentile intensity of the ion signal of 209.122, with 211% indicating 2.11× the reference maximum intensity. Scale bar, 1 mm. e, f Survival rates of tumour cells and immune cells in MC38 tumours after 2 days (e, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, **p = 0.0011, ***p = 0.0002, ***p = 0.0002, respectively) or 5 days (f, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, **p = 0.0026; NC vs X-ray (4 Gy) of non-immune cells, *p = 0.0407; NC vs X-ray (4 Gy) of immune cells, *p = 0.0307) of BNCT treatment, as detected by flow cytometry, n = 3 mice for each group tested. NC, negative control. g–i Representative examples of MC38 tumours from NC group (g), X-ray (4 Gy) group (h), and BNCT group (i) by immunohistochemical staining with anti-CD8 (green), anti-CD11c (purple), anti-F4/80 (brown) and anti-MHC-II (cyan) antibodies and DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm. j–n Proportion of CD8+ T cells (j, *p = 0.0351, **p = 0.0037), CD11c+ myeloid cells (k, **p = 0.0014, ****p < 0.0001), CD11c+MHC-II+ cells (l, **p = 0.0050, ****p < 0.0001), F4/80+ macrophages (m, ****p < 0.0001), and F4/80+MHC-II+ cells (n, NC vs X-ray, *p = 0.0230, X-ray vs BNCT, *p = 0.0141, NC vs BNCT, **p = 0.0042) in tumours. (n = 7 mice for each group tested, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test). The data are the means ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To clarify the selective accumulation of boron in tumour cells, we examined the expression of Slc7a5 in non-immune (CD45-) and immune (CD45+) cells in the B16F10 and MC38 tumour models. We found that the expression level of the Slc7a5 gene in non-immune cells was 10.07 times (Fig. 3b) and 10.41 times (Fig. 3c) higher than in immune cells, respectively, indicating the selective enrichment of boron in non-immune cells, greatly reducing the probability of a boron neutron capture reaction in immune cells. Additionally, the uneven distribution of BPA within the tumours in vivo was confirmed via MALDI-TOF imaging (Fig. 3d). In regions with blood flow where immune cells were concentrated, the BPA accumulation was low.

Assessing cell viability within the tumour provides direct insight into the preservation of immune cells by BNCT. Two days after BNCT treatment, the viability of non-immune cells (CD45-) slightly declined (Fig. 3e), and by day 5, their activity had decreased to below 40% (Fig. 3f), confirming the tumour-killing efficacy of BNCT. In contrast, the viability of immune cells (CD45+) remained unchanged compared with that of the control group at both time points (Fig. 3e,f), underscoring the ability of BNCT to effectively eliminate tumour cells without harming immune cells within the tumour microenvironment. On the other hand, X-ray treatment was less effective than BNCT in eradicating tumour cells, causing substantial damage to immune cells (Fig. 3e,f), with this damage persisting for at least 5 days, highlighting BNCT’s unique advantage of selective tumour-cell killing while preserving immune cell function.

Furthermore, immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 3g–n) revealed increased numbers of infiltrating immune cells in the tumour tissue following BNCT treatment. Compared with untreated tumours, BNCT-treated tumours exhibited increased infiltration of three types of immune cells: CD8+ T cells, CD11c+ (particularly CD11c+MHC-II+) myeloid cells, and F4/80+ (especially F4/80+MHC-II+) macrophages. Compared with X-ray treatment, tumours under BNCT increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells, CD11c+MHC-II+ myeloid cells, and F4/80+MHC-II+ macrophages. These findings suggested that immune cells were not directly affected by BNCT and that indirect mechanisms might be involved in their recruitment.

scRNA-seq reveals inflammatory cancer cell subclusters following BNCT

Since BNCT is a single-cell killing therapeutic modality, we employed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to analyze the tumour microenvironment after BNCT treatment. For the immunologically cold B16F10 tumour, all tumour cells were harvested one day after BNCT treatment. On day 7, CD45+ immune cells were enriched at a ratio of CD45- to CD45+ was 1:2, followed by library preparation, sequencing, and analysis (Fig. 4a). After data filtering, 63,415 cells were captured in the B16F10 tumour experiment: 10,679 from the NC (negative control) group, 8478 from the X-ray group, and 14,278 from the BNCT group on day 1; 14,356 from the NC group, 8758 from the X-ray group, and 6902 from the BNCT group on day 7. Clustering was performed, and cell populations, including cancer cells, DCs, T cells, NK cells, B cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, macrophages, and monocytes, were annotated on the basis of marker gene expression (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Figs. 5a–c,6a).

a Workflow for single-cell RNA sequencing of B16F10 tumours (C57BL/6J mice, 6–8-week-old, female). b UMAP plot of all single-cell transcriptomes from 6 B16F10 samples coloured by major cell types. c Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of upregulated genes in BNCT-treated B16F10 cancer cells compared with X-ray (4 Gy)-treated B16F10 cancer cells on days 1 and 7. Fisher’s exact test. d UMAP plot of all cancer cell transcriptomes from 6 B16F10 samples coloured by cell subtype. e Proportional changes in c3 cancer cell subtypes. NC, negative control. f Number of genes expressed across the four cancer cell subtypes in the B16F10 samples. Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test two-sided, ****p < 0.0001. Top and bottom quartiles are shown with horizontal lines at the median, and whiskers denote the range of the data that falls within 1.5 times the interquartile range above the third quartile and below the first quartile. c0, 6418 cells; c1, 4977 cells; c2, 4947 cells; c3, 3342 cells. g Top 10 enriched GO pathways in the c3 subtypes of BNCT-treated B16F10 tumour cells. Fisher’s exact test. h Workflow for single-cell RNA sequencing of MC38 tumours (C57BL/6J mice, 6–8-week-old, female). i UMAP plot of all single-cell transcriptomes from 6 MC38 samples coloured by major cell types. j Boxplot of the expressed genes number across four cancer cell subtypes. Fisher’s exact test. k Proportion of four cancer cell subtypes. l Expressed genes number across four cancer cell subtypes in MC38 samples. Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test two-sided, ****p < 0.0001. Top and bottom quartiles are shown with horizontal lines at the median, and whiskers denote the range of the data that falls within 1.5 times the interquartile range above the third quartile and below the first quartile. c0, 7986 cells; c1, 813 cells; c2, 5846 cells; c3, 6047 cells. m Top 10 enriched GO pathways in the c3 subtypes of BNCT-treated MC38 tumour cells. Fisher’s exact test. n Venn diagram showing the overlap of differentially expressed genes in c3 cancer cells from B16F10 and MC38 tumour tissues.

Differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis of tumour cells following BNCT treatment (Supplementary Fig. 6b,c) revealed that compared with those in the X-ray group, tumour cells on day 1 presented upregulated expression of cell cycle-related genes, such as Ccng1 and Cdkn1a. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of enriched pathways revealed an increase in the G1 DNA damage signalling pathway and DNA damage checkpoint signalling in the BNCT group (Fig. 4c). Analysis of the cell cycle (Supplementary Fig. 6d) also indicated that relative to the NC group, BNCT treatment increased the proportion of tumour cells in the G1 and G2/M phases, with a greater percentage of G2/M phase cells than in the X-ray group. Notably, the increase in G1 phase cells persisted until day 7 in the BNCT group. In contrast, the cell cycle of X-ray-treated cells was similar to that of the control group, suggesting that BNCT caused more severe and persistent cell cycle damage, impairing tumour cell proliferation. More importantly, on day 7 post-BNCT, tumour cells presented significant upregulation of immune-related genes, such as the Tnf, Irf8, Ifitm3, and Irgm1 genes, which were enriched in response to interferon pathways (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 6c).

Owing to the heterogeneity of the boron distribution and the spatial complexity of the tumour tissues, we further clustered the tumour cells (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 5d,6e). Compared with those in the X-ray treatment group, the highly proliferative c0_Mki67 subcluster, characterized by high expression of cell cycle-related genes, such as Mki67, Top2a, and Cdk1 (Supplementary Fig. 6g), decreased from 40% to 25% on day 1 post-BNCT. By day 7, the proportion of the c0_Mki67 subcluster in the X-ray group was similar to that in the NC group. In contrast, this subcluster further declined to below 10% in the BNCT group (Supplementary Fig. 6f), suggesting that BNCT treatment more effectively disrupted the activity of highly proliferative cells, with a stronger and more sustained impact than X-ray treatment. The c1_Fgfr2+ subcluster had no obvious changes in proportion (Supplementary Fig. 6h). The c2_Jund+ subcluster, which was characterized by its high expression of the Jund gene, a known stress-related regulator of cell cycle progression41, displayed G1 phase cell cycle arrest (Supplementary Fig. 6i,j), and increased from 20% to 30% on day 1 following both BNCT and X-ray treatments. By day 7, the proportion of these cells continued to increase in the BNCT group, whereas in the X-ray group, it decreased to levels comparable to those in the NC group, which was consistent with the observed changes in the cell cycle distribution (Supplementary Fig. 6d).

The c3_Rp+ subcluster was characterized by a lower number of expressed genes and upregulation of ribosomal-related genes, such as Rps29 and Rps27. The c3_Rp+ subcluster accounted for more than 30% of the cells in the BNCT group on day 7, compared with only approximately 10% in the X-ray and NC groups (Fig. 4e), and exhibited immune-related signatures (Supplementary Fig. 6k). The total expressed gene number of cells may reflect the extent of cellular damage42. Different clusters presented various numbers of expressed genes (Fig. 4f). The c0_Mki67+ subcluster, representing highly proliferative cells, exhibited the greatest number of expressed genes. While compared with the c0_Mki67+ subcluster, the c1_Fgfr2+ (Supplementary Fig. 6e) and c2_Jund+ subclusters approximately presented two-thirds of the total expressed counts within the c0_Mki67+ subcluster, possibly suggesting the mild damage induced by BNCT. Notably, the c3_Rp+ subcluster showed a markedly reduced expressed gene number, which may indicate severe damage. Further analysis of the c3_Rp+ subcluster’s gene expression profile also revealed the pathway enrichment of the inflammatory response and granulocyte chemotaxis (Fig. 4g). Additionally, this subcluster showed markedly greater expression of certain cytokines, including the Ccl8 and Ccl5 genes, than the other subclusters did (Supplementary Fig. 6l).

We also analyzed the immunologically hot tumour model MC38 via scRNA-seq. Tumour cells were collected 5 days after BNCT or X-ray treatment (Fig. 4h), capturing 24,910 cells, including 7894 from the NC group, 9580 from the X-ray group, and 7436 from the BNCT group. After clustering the tumour cells (Fig. 4i, Supplementary Figs. 7a–c, 8a), we observed that tumour cells treated with BNCT exhibited an inflammatory phenotype, with the upregulated genes significantly enriched in pathways related to the response to interferon and chemokines (Fig. 4j, Supplementary Fig. 8b), compared with those in the X-ray group. Additionally, we identified a subpopulation denoted as c3, which increased in proportion following BNCT treatment (Fig. 4k). This cluster had a reduced number of expressed genes (Fig. 4l) and was enriched in the neutrophil and granulocyte chemotaxis pathways (Fig. 4m). Notably, the two c3 subclusters from B16F10 and MC38 tumours shared 40 overlapping genes among the top 100 specifically upregulated in the BNCT group compared with the X-ray group (Fig. 4n, Supplementary Fig. 8c), including some genes encoding cytokines such as Ccl2, Ccl8, Ccl12, Cxcl2, Ccl9, and Ccl6. In summary, single-cell RNA sequencing revealed a unique subpopulation of tumour cells exhibiting a low expressed gene number, with an increased proportion following BNCT treatment. These cells demonstrated significant upregulation of immune-related genes, specifically cytokines, a phenomenon conserved across the B16F10 and MC38 tumour models. These cells likely serve as critical triggers for the induction of BNCT-mediated anti-tumour immunity.

BNCT remodels the tumour microenvironment and stimulates DCs, T cells and NK cells

The tumour-killing effects of BNCT are intricately linked to the involvement of the immune system. Therefore, we next focused on the dynamics of immune cell populations within the tumour microenvironment. As pivotal antigen-presenting cells, DCs play a critical role in initiating and orchestrating immune responses3. These cells are capable of recognizing and processing antigens and then presenting them to T cells to activate specific adaptive immune responses.

In the immunologically cold B16F10 tumour model (Supplementary Fig. 9a), DCs exhibited significant gene expression changes relative to those in the X-ray group at 7 days post-BNCT treatment, as depicted in Fig. 5a. These genes were enriched in pathways associated with antigen processing and presentation, interferon and interleukin-1 response, and DC chemotaxis (Fig. 5b), as interferon and interleukin-1 are key stimulators of DC maturation. While antigen processing and presentation functions in DCs were not significantly enhanced in the BNCT group on day 1 post-treatment (Supplementary Fig. 9b), there was a marked improvement by day 7 compared with both the NC and X-ray groups (Fig. 5c). Concurrently, genes such as Ccl8, Cxcl2, Ccl2, and Ccl6 were significantly upregulated (Fig. 5d), and they could recruit various immune cells to promote the immune response (including immature DCs, monocytes, and T cells). In the immunologically hot MC38 tumour model (Supplementary Fig. 9c), DCs within BNCT-treated tumour tissues also exhibited upregulated antigen processing and presentation functions (Fig. 5e). These findings suggested that BNCT treatment induced the activation and functional enhancement of DCs within the tumour microenvironment in a time-dependent manner, which might be correlated with the delay in BNCT-induced cell death. We established an in vitro co-culture system to assess DC antigen-presenting capacity (Fig. 5f). Bone marrow derived-dendritic cells (BMDCs) indirectly co-cultured with BNCT-treated B16F10 cells for 3 days showed significantly increased CD80 (Fig. 5g) and CD86 (Fig. 5h) expression compared with control or X-ray groups. When these DCs were subsequently co-cultured with spleen-derived CD8+ T cells, the proportion of CD25+ CD69+ T cells increased after 24 h (Fig. 5i), indicating enhanced T-cell activation. Flow cytometry analysis of DCs in tumour tissues revealed increased expression levels of the costimulatory factors CD80 and CD86 after BNCT treatment in both B16F10 (Fig. 5j,k, Supplementary Figs. 9d,10) and MC38 tumours (Fig. 5l,m, Supplementary Figs. 9e,11), indicating an enhanced ability of DCs to activate T cells, further supporting the role of BNCT in promoting an immune-active tumour microenvironment.

a Volcano plot depicting differentially expressed genes of dendritic cells in BNCT-treated and X-ray (4 Gy)-treated B16F10 tumour tissue on day 7. Pink dots or blue dots represent up-regulated or down-regulated genes, respectively, in BNCT-treated B16F10 DCs. Not sig, not significant. Two-tailed Welch’s t-test. b Top 10 enriched GO pathways in the DCs of BNCT-treated B16F10 tumour tissue compared with those of X-ray (4 Gy)-treated samples. Fisher’s exact test. c Antigen processing and presentation by DCs in B16F10 tumour. NC, negative control. Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test two-sided, *p = 0.0376, ***p = 0.0002, ****p < 0.0001. Top and bottom quartiles are shown with horizontal lines at the median, and whiskers denote the range of the data that falls within 1.5 times the interquartile range above the third quartile and below the first quartile. d Heatmap of antigen presentation-related DEGs in DCs. e Antigen processing and presentation signature scores of DCs in the MC38 models. Top and bottom quartiles are shown with horizontal lines at the median, and whiskers denote the range of the data that falls within 1.5 times the interquartile range above the third quartile and below the first quartile. f Treatment schemes for the co-culture assay. g, h, Expression levels of CD80 (g, NC vs X-ray, *p = 0.0153, X-ray vs BNCT, **p = 0.0035, NC vs BNCT, **p = 0.0017) and CD86 (h, X-ray vs BNCT, *p = 0.0037, NC vs BNCT, **p = 0.0055) of BMDCs. n = 3 independently tested cell samples for each group. i The ratio of CD25+ CD69+ T cells in CD8+ T cells after 24 h co-culture. n = 4 independently tested cell samples for each group, ****p < 0.0001, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. j–m Expression levels of CD80 of DCs in B16F10 tumours (j, k) or MC38 tumours (l, m). n = 4 mice for each group tested, C57BL/6J mice, 6–8-week-old, female. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, ****p < 0.0001, *p = 0.0288. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. The data are the means ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

T cells are central mediators of the adaptive immune system in the fight against cancer. In particular, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells are the most powerful effectors of the anticancer immune response and constitute the backbone of cancer immunotherapy3. We further focused on T-cell changes in the tumour microenvironment after BNCT treatment and clustering analysis of T cells in B16F10 tumour tissues was performed (Supplementary Fig. 9f–h). Although the composition of T-cell subsets did not significantly change (Supplementary Fig. 9i), the CD8+ T cells exhibited an overall activated phenotype following BNCT treatment (Supplementary Fig. 9j). Compared with those in the NC and X-ray groups, the CD8+ T cells in the BNCT-treated MC38 tumours exhibited a significantly increased activation signature (Fig. 6a) and a reduced exhaustion signature (Fig. 6b) 5 days after BNCT treatment. The activation of CD8+ T cells in MC38 tumours was consistent with that in the B16F10 tumour model, demonstrating that the activation effect of BNCT on CD8+ T cells is conserved across tumour models.

a Activation signature score of CD8+ T cells in MC38 tumour. NC, negative control. Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test two-sided, *p = 0.020, ***p = 0.0007. b Exhaustion signature score of CD8+ T cells in MC38 tumour. Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test two-sided, *p = 0.037. Boxplots in a and b show top and bottom quartiles with horizontal lines at the median, and whiskers denote the range of the data that falls within 1.5 times the interquartile range above the third quartile and below the first quartile. c Proportion of expanded or nonexpanded T cells in the MC38 model. Expansion: T-cell number with the same TCR clone greater than 1. Not expansion: the T-cell number with the same TCR clone is equal to 1. d Pie chart showing the TCR clone number; the neighbouring number represents the number of T-cells sharing the same TCR clone. e–g, Proportion of CD4+ T cells (e) and CD8+ T cells (f) and the ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells (g) within the T-cell population in MC38 tumour tissue. n = 3 mice for each group tested, C57BL/6J mice, 6–8-week-old, female. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, e *p = 0.0131, f *p = 0.0119, g **p = 0.0092. h Representative immunofluorescence images of MC38 tumour samples from the negative control (NC) group and X-ray (4 Gy) or BNCT-treated groups. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) and an antibody against CD8a (green). Scale bar, 200 μm. Average tumour volumes (i, j) and survival fractions (k) of each group of MC38-bearing C57BL/6J mice (6–8-week-old, female) treated with BNCT or the combination of BNCT and an anti-CD8 antibody (n = 5 mice for each group tested). Average tumour volumes (l, m) and survival fractions (n) of each group of MC38-bearing C57BL/6J mice (6–8-week-old, female) treated with BNCT or the combination of BNCT and FTY720 (n = 5 mice for each group tested). The data are the means ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

T cell activation requires extracellular stimulatory signals that are mediated mainly by T-cell receptor (TCR) complexes, which function in tumour antigen recognition and signal transduction by interacting with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules43. Radiation-driven immunogenic cell death may facilitate “antigen spread”44, which could diversify the TCR repertoire. While TCR expansion has been shown to play a crucial role in anti-tumour immunity45, TCR sequencing of T cells from BNCT- or X-ray-treated MC38 tumours was performed to assess the TCR repertoire, which reflecting the dynamics of T cells. Following BNCT treatment, the proportion of expanded T cells (~20%) was greater than that in the X-ray group (< 10%), with no expanded T cells detected in the NC group (Fig. 6c). These findings indicated that both BNCT and X-ray treatments can promote the expansion of T cells, with BNCT having a stronger effect. Additionally, analysis of the TCR repertoire composition (Fig. 6d) revealed that X-ray treatment favoured the expansion of the specific T cell clones. In contrast, BNCT treatment increased the expansion and diversity of the TCR repertoire globally. These findings suggested that BNCT may expand tumour antigen pools and facilitate the presentation of a broader range of tumour-specific antigens, enhancing the ability of the immune system to recognize and attack tumour cells.

Flow cytometry analysis of MC38 tumour tissues following BNCT treatment revealed a decreased proportion of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6e) and an increased proportion of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6f). The ratio of CD8+ to CD4+ T cells was also elevated (Fig. 6g). Moreover, BNCT treatment increased the infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6h), which exhibited a clustered distribution.

Next, we explored the necessity of CD8+ T cells in BNCT-induced anti-tumour immunity. When BNCT was combined with CD8-neutralizing antibodies during the first 8 days post-treatment, the anti-tumour effect was comparable to that of BNCT treatment alone (Fig. 6i,j). However, starting from day 10, the tumours in the group treated with both CD8-neutralizing antibodies and BNCT grew continuously, leading to the death of the mice due to the tumour burden (Fig. 6k). Furthermore, FTY720 can inactivate sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptors on T cells, inhibiting T-cell egress from lymphoid organs46. The inhibition of T-cell migration by FTY720 resulted in a weakened tumour-killing ability of BNCT, with continuous tumour growth in mice (Fig. 6l,n), indicating that T cells in lymphoid tissues were also necessary for the anti-tumour effects of BNCT. Both experiments demonstrated that within a certain period after BNCT treatment (approximately 10 days), BNCT suppressed tumours through the direct cytotoxic effect of high-LET radiation. Over time, BNCT-induced anti-tumour immunity gradually played the leading role, with CD8+ T cells and T cells in lymphoid tissues essential.

CD8+ T cells interact with MHC class I (MHC-I) molecules on tumour cells, which present antigenic peptide fragments. We observed that both on day 1 and day 7 post-treatment, the overall expression of MHC- I molecules in tumour cells was significantly greater than that in the control group for both the BNCT and X-ray treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. 12a,b), with a more pronounced increase in the BNCT group. Additionally, several genes encoding MHC-I molecules, particularly the key genes H2-K1 (Supplementary Fig. 12d) and H2-D1 (Supplementary Fig. 12e), were significantly upregulated in the BNCT group (Supplementary Fig. 12c). Similar observations were also observed in MC38 tumours, where BNCT treatment led to a significant increase in MHC-I molecule expression (Supplementary Fig. 12f). These findings suggested that BNCT might increase the level of peptide presentation by increasing the surface expression of MHC-I on tumour cells, thereby improving the ability of tumour cells to be recognized by T cells, which contributed to its tumour-killing efficacy.

Natural killer (NK) cells exhibit potent cytotoxicity and secrete cytokines and chemokines such as IFN-γ and TNF, which aid B-cell and T-cell responses and modulate the functions of DCs and neutrophils, thus inducing systemic anti-tumour immunity3. In the B16F10 and MC38 tumour models, NK cell cytotoxicity in the BNCT groups was significantly elevated compared with that in the NC and X-ray groups (Supplementary Fig. 12g,h). Moreover, the expression of cytotoxicity-related genes, such as Granzyme B (Gzmb) and Interleukin-18 (Il-18), was significantly upregulated (Supplementary Fig. 12i,j). These findings indicated that NK cells in the tumour microenvironment were activated following BNCT treatment. This could result in enhanced anti-tumour function, which was conserved across both “cold” and “hot” tumour models. However, the depletion of NK cells did not affect the therapeutic efficacy of BNCT, indicating that although NK cells could be activated after BNCT, they were not essential for the anti-tumour immune effects (Supplementary Fig. 12k–m).

Discussion

Radiotherapy has long sought to achieve precision, balancing effective tumour eradication with the preservation of normal tissues47. The concept of single-cell radiotherapy may represent a further step, potentially targeting tumour cells at the cellular scale to induce immunogenic cell death while sparing immune cells, thereby maximizing tumour control and maintaining immune competence. In this work, we explored the anti-tumour immunity induced by boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) and revealed that BNCT could offer both potent tumour cell killing at the single-cell level and the ability to spare immune cells. This cellular selectivity arises from the tumour-targeting property of the boron carrier BPA transported into cells via LAT130,31, which is expressed at 10 times higher levels in tumour cells than in immune cells, thus conferring tumour-targeting specificity. We examined immune cell viability in vivo and found that two days after treatment, immune cell activity remained unchanged in the BNCT group but declined in the X-ray group—a trend that persisted even five days after treatment. Importantly, the immune consequences of BNCT extend beyond passive protection of immune cells. We observed robust systemic immune responses, including abscopal effects, in-situ tumour vaccine-like functions of BNCT-treated tumour cells, and persistent immune memory.

Mechanistically, compared with low-LET X-rays, BNCT enhanced immunogenic cell death and induced more DNA double-strand breaks. These breaks persisted longer and were more difficult to repair, leading to cell cycle arrest or even cell death. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has enabled precise identification of cellular subpopulations, which matches the cellular-scale killing characteristics of BNCT and provides a powerful tool for investigating cell-specific responses in vivo. Our scRNA-seq analysis revealed that specific subpopulations of tumour cells, such as the c3_Rp+ subset, exhibited immune-related phenotypes upon BNCT, while others, such as c2_Jund+ , underwent cell cycle arrest and relied on immune clearance. Our findings further indicated that BNCT actively reshaped the tumour immune microenvironment. We observed enhanced antigen presentation of dendritic cells and activation signatures in CD8+ T cells compared to X-ray irradiation, highlighting the critical role of CD8+ T cells in BNCT-mediated immune responses. Innate immune processes showed upregulated natural killer cell cytotoxicity. The phenomenon of BNCT activating DCs, T cells, and NK cells is conserved in “cold” B16F10 and “hot” MC38 tumour models, underscoring the broad immunological potential of this modality.

In addition, based on our work, several basic scientific issues remain for further exploration. Our data demonstrated that BNCT-treated tumour cells exhibited both immunogenic features and mitochondrial damage, helped to rule out a predominant role of classical apoptosis or caspase-dependent mechanisms, and instead supported the possibility of caspase-independent modes of cell death48. However, the precise mode of cell death49 induced by BNCT remains to be clarified. The c3+ cancer cell subpopulation highly expressed ribosomal component genes, and ribotoxin stress responses could regulate signaling pathways that determine cell fate50, while its role in BNCT-induced death is unclear. Defining the molecular identity of BNCT-induced cell death will therefore be an essential direction for future research.

Altogether, our findings may represent a conceptual change that radiotherapy at the single-cell level may provoke stronger anti-tumour immunity by “excusing” immune cells. Moving forward, clinical strategies may also prioritize enhancing tumour-targeting specificity while avoiding immune cell damage, offering a transformative pathway to optimize therapeutic outcomes.

Methods

Mice

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Animal Protection Guidelines of Peking University, China. Animal care and experimental procedures adhered to the animal protocols (IACUC ID: CCME-LiuZB-2) approved by the ethics committee of Peking University. 6–8-week-old female (Considering that female mice exhibit lower aggression when living in groups, which are more suitable for group breeding with reduced management difficulty) C57BL/6J (#213) mice were obtained from Vital River Laboratories (Beijing, China) and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions, maintaining a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 24 ± 2 °C and 50 ± 10% relative humidity, with free access to food and water. The experimental and control animals were co-housed. Animals were euthanized according to IACUC-approved endpoints, including a tumour burden exceeding defined limits (estimated >10% body weight or >20 mm in any dimension), tumours that ulcerated or infected, or tumours that interfered with normal bodily functions, significantly impaired gait, or compromised the animal’s ability to obtain food or water.

General protocols of animal studies

The exact sample size is indicated in the legend. All data were included in the analysis; no data were excluded. All results were independently replicated at least three times with similar results. Mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups (randomization followed two criteria: each mouse had an equal probability of being assigned to any experimental group; and the assignment of one mouse to a group did not affect the assignment of other mice to the same group). Appropriate blinding was used during data collection and analysis.

Cell culture

The B16F10 (#CL-0319) cell lines were purchased from Procell. The MC38 cell lines (#SNL-505) were purchased from SUNNCELL. The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, C11995500BT, Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum, SE100-B, Vistech) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (15070063, Gibco) at 37 °C under 5% CO₂. Upon reaching 80% confluence, the cells were treated with PBS (Phosphate buffered saline, M52270, Meryer) and trypsin (25200114, Gibco) and subcultured into a new culture dish.

Tumour growth and treatment

To verify the efficacy of BNCT for a single tumour model, approximately 1 × 10⁶ B16F10 cells or 5 × 10⁵ MC38 cells suspended in 100 μL of PBS were implanted subcutaneously into the mice. Tumour volumes were calculated via the following formula: volume = 1/2 × length × width². Tumour volumes were measured daily or every two days,or twice a week. The therapeutic experiment was conducted when the tumour volume reached 40–100 mm³, which was 7 days for B16F10 tumours and 10 days for MC38 tumours after transplantation. To establish a mouse tumour model of the abscopal effect, 1×10⁶ B16F10 cells or 5×10⁵ MC38 cells were suspended in PBS (100 μL) and injected subcutaneously into the right shoulders of C57BL/6J mice, while half of the tumour cells were injected into the left abdomen. Only the tumours on the right side of the mouse were exposed to thermal neutrons. For the mouse tumour vaccine experiments, B16F10 cells or MC38 cells were incubated overnight with 10 mM [10B]BPA and irradiated with thermal neutrons for 10 min. Then, BNCT-treated B16F10 cells (1 × 10⁶) or MC38 cells (5 × 10⁵) were subsequently injected subcutaneously into the right shoulder of each mouse. Ten days later, an equal number of untreated tumour cells were injected subcutaneously into the left abdomen of each mouse. For the mouse tumour rechallenge experiments, 5 × 10⁵ MC38 cells were subcutaneously inoculated into the left abdomen of mice at 10 or 20 weeks after the initial tumour inoculation. At week 10, memory T cells were analysed from the blood, axillary lymph nodes, and spleen, or tumours were reimplanted on the left side of some mice to monitor tumour growth. For the CD8 depletion experiments, 200 μg of anti-CD8 antibody (BE0061, Bioxcell) was injected intraperitoneally every three days. For FTY720 treatment, 10 μg of FTY720 (S5002, Selleck) was administered intraperitoneally one day before the initiation of BNCT treatment, followed by 10 μg every other day for two weeks. For NK cells depletion, 200 μg of Ultra-LEAF Purified anti-mouse NK-1.1 Antibody (108759, Biolegend) was administered intraperitoneally one day before the initiation of BNCT treatment, followed by 200 μg every three days.

Tumour and spleen digestion

Tumour tissues were excised and digested with 1 mg/mL collagenase I (SCR103, Sigma) and 0.5 mg/mL DNase I (18047019, Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 30 min. The tumour cell suspension was then passed through a 70 μm cell strainer to remove large pieces of undigested tumour. The spleens from the mice were excised and ground using a 70 μm cell strainer, then transferred to a lymphatic separation solution (7211011, Dakewe). The upper layer was centrifuged for 30 min at 800 g after adding 1 mL Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (RPMI1640, C11875500BT, Gibco), with a slow rise and fall during centrifugation. The right axillary lymph nodes of the mice were harvested for lymph node cells, ground with a syringe plunger through a 70 μm cell strainer, and added to RPMI1640 medium. At room temperature, lymphocytes were centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min, with a slow rise and fall during centrifugation.

Preparation of the BPA solution

The NaOH solution was prepared and allowed to cool for future use. The NaOH solution was used to dissolve 200 mg of [10B]BPA (80994598, Dongguan HEC). Then 180 mg of fructose was added to the reaction mixture, which was stirred for 10 min. Then, the pH was then adjusted to 7.5, and the solution was sterilized through a 0.22 µm filter.

Cellular and in vivo boron concentrations

For cellular boron uptake, B16F10 or MC38 cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well and incubated under standard conditions. The cells were treated with 2–20 mM [10B]BPA and incubated overnight. Then, the cells were washed three times with PBS to remove any residual boron from the culture medium, and then the cells were subsequently digested, centrifuged, and washed again. The cell pellets were lysed with 300 μL HNO3 (112066, TGREAG) at 65 °C for 30 min and then diluted with deionized water. The boron concentration was determined via ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry, NexlON 350X, PerkinElmer).

For determination of the tumour boron concentration, mice bearing B16F10 or MC38 tumours received intravenous injections of 100 mg/kg [10B]BPA solution. 60 min post-injection, the mice were euthanized. Blood and tumours were collected, weighed, and lysed in the microwave-accelerated reaction system with HNO3 at 140 W for 10 min, and then diluted with deionized water for analysis. The boron concentration in these samples was assessed via ICP-MS.

BNCT of cells and animals

Cells or animals were irradiated at the In-Hospital Neutron Irradiator 1 (IHNI-1), which is based on a miniature neutron source reactor, with a thermal neutron flux of 1.9 × 109/cm²/s. The information of neutron spectrum can be found in reference51. The dose rate of boron-10 at 1 ppm is about 0.0124 cGy/s, the total neutron dose rate is 0.0626 cGy/s, and the γ dose rate is 0.0151 cGy/s. For cell irradiation, MC38 and B16F10 cells cultured in a cell culture bottle were incubated with boron carriers overnight and then irradiated for 10 min using thermal neutrons, ensuring that the adherent culture side was positioned close to the beam outlet. For animal irradiation, each mouse in the BNCT group received an intravenous injection of [10B]BPA (100 mg/kg). Before neutron irradiation, mice anaesthetized with tribromoethanol (MA0478, MeilunBio) were secured onto a custom-made module, with the tumour-bearing side positioned close to the beam outlet. 60 min after [10B]BPA treatment, the mice were irradiated with thermal neutrons for 20 min (MC38-bearing mice) or 30 min (B16F10-bearing mice).

Dosimetry by SERA

The neutron capture cross sections (σ) vary significantly between nuclides. The thermal neutrons are preferentially captured by 10B nuclei (3837 barn), and can also be captured by H (0.332 barn) and N (1.75 barn) of which tissues are mainly composed of. Therefore, the magnitude of the radiation dose of BNCT is complicated due to the radiation field in BNCT consists of several separate radiation dose components including B-10 dose (DB, from 10B(n,α)7Li reaction), gamma dose (Dγ, from hydrogen 1H(n,γ)2H in tissue), N-14 dose (DN, from 14N(n,p)14C in tissue) and hydrogen dose (DH, from 1H(n,n)p in tissue) with different physical properties.

The Monte Carlo computation-based dose calculation was performed with SERA (Simulation Environment for Radiotherapy Applications; Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID), tumours were simulated as the average soft tissue (adult ICRU-33) according to ICRU report 4652.

Calculation of radiation dose of B16F10 tumour and MC38 tumour

The average boron accumulation (Conc.B) in B16F10 tumour and MC38 tumour was 7.74 ppm and 12.60 ppm, respectively, with thermal neutron irradiation time (T) of 30 min and 20 min, respectively. Tumour tissue was simulated as a sphere with a radius of 0.5 cm. By Monte Carlo computation, the dose rates for four radiation components were:

The total absorbed dose:

The therapeutic doses were 4.395 Gy for B16F10 tumour model and 4.029 Gy for MC38 tumour model, respectively.

Boron distribution imaging

The MC38-bearing mice were injected with 100 mg/kg of [10B]BPA by the tail vein. Then, the tumour tissue was dissected one hour later. The tissues were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then rewarmed for 1 h at −20 °C. The section thickness was set to 14 µm. Spatial imaging of boron was conducted via matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS, Bruker) at a resolution of 50 µm.

X-ray radiation delivery

X-ray irradiation was conducted via an X-ray generator (RS2000 Pro 225, 225 kV, 17.7 mA; Rad Source Technologies). The cells received a total dose of 10 Gy at a rate of 2.09 Gy/min. For animal irradiation, mice anaesthetized with tribromoethanol were secured onto a module while the remainder of the body was shielded with 5-mm-thick lead. The tumours were irradiated locally at a dose of 4 Gy at a rate of 2.09 Gy/min.

Extracellular ATP assay

The treated cells were digested and transferred to a 96-well plate. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, the extracellular ATP level was measured via the RealTime-Glo Extracellular ATP Assay (GA5010, Promega).

Cell viability assays by CCK-8

To evaluate cell viability following BNCT treatment, MC38 and B16F10 cells were incubated with [10B]BPA overnight. The cells were then irradiated with thermal neutrons for 5 min or under 4 Gy X-ray irradiation. After treatment, MC38 and B16F10 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a concentration of 5 × 10³ cells per well. Cell viability was assessed via the CCK-8 (C0040, Beyotime) assay at 24, 48-, 72-, 96-, and 120 h post-irradiation, following the manufacturer’s protocol. For the combination of BNCT with inhibitors, MC38 and B16F10 cells were incubated overnight with [10B]BPA and/or various inhibitor molecules. The inhibitors included Necrostatin-1s (20 µM, HY-14622A, MCE), GSK872 (5 µM, HY-101872, MCE), Z-VAD-FMK (40 µM, HY-16658B, MCE), Z-IETD-FMK (25 µM, HY101297, MCE), ZDEVD-FMK (50 µM, HY-12466, MCE), and Ferrostatin-1 (5 µM, HY-100579, MCE). The cells were subsequently irradiated with thermal neutrons for 5 min.

H&E staining

Tumours were excised from the mice in different groups 1, 3, and 5 days after treatment. The tumour tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (P0099, Beyotime), embedded in paraffin, sectioned into slices, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (C0105S, Beyotime). The slices were photographed via 3Dhistech, and the data were analyzed with ImageJ (version 1.53a).

Transmission electron microscopy imaging

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were acquired using a JEM-2100F microscope (JEOL Ltd., Japan). The sample preparation procedure was as follows: cells were initially fixed at room temperature for ~5 min in 2.5% glutaraldehyde fixative. The cells were then gently scraped in one direction using a cell scraper, and transferred into a centrifuge tube and centrifuged for 2 min. After discarding the supernatant, fresh fixative was added, and the samples were further fixed at room temperature for 30 min in the dark.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was used to detect phospho-γH2AX in BNCT-treated or X-ray-treated MC38 cells in vitro. A total protein extraction kit (BC3710, Solarbio) was used to extract proteins from the tumours. The concentrations were determined via the BCA protein assay kit (PC0020, Solarbio). Proteins were diluted with 5× SDS-PAGE buffer, boiled for 15 min, subjected to appropriate concentrations for electrophoresis, and then transferred to PVDF membranes. The primary antibodies used were specified as follows: GAPDH (D16H11) XP Rabbit monoclonal mAb (5174S, CST, 1:200), Phospho-histone H2A.X (Ser139) (20E3) (9718S, CST, 1:200). The secondary antibody used was anti-rabbit (7074S, CST). Proteins were analyzed via the GelDoc Go Gel Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

Cell sorting and quantitative PCR

The MC38 and B16F10 tumours were digested into single cells, followed by staining with anti-mouse CD45 FITC (147710, BioLegend) on ice for 1 h. The immune cells (CD45+) and non-immune cells (CD45-) were sorted using a flow cytometer (BD FACSAria III Cell Sorter). RNA was extracted from the sorted cells using RNeasy Mini Kit (74104, QIAGEN), and then cDNA was subsequently synthesized via a PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (RR037A, TaKaRa). The expression level of the Slc7a5 gene was measured via quantitative PCR (qPCR) using LightCycler 96 System (Roche) and BlazeTaq SYBR Green qPCR Mix 2.0 (QP041, GeneCopoeia). Primers were synthesized by RuiBiotech. qPCR was performed for 30 s at 95 °C, 45 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s, with subsequent melting-curve analysis. The expression of target genes was normalized to that of β-actin. The primers used for qPCR with reverse transcription were as follows: β-actin (forward 5′-GTGACGTTGACATCCGTAAAGA-3′, reverse 5′-GCCGGACTCATCGTACTCC-3′), Slc7a5 (forward 5′-CTGACACCTGTGCCATCACT-3′, reverse 5′-TTCACCTTGATGGGACGCTC-3′).

Single-cell sample preparation

B16F10 tumours: Three tumour-bearing mice were irradiated with 4 Gy X-ray. Three tumour-bearing mice were intravenously injected with 100 mg/kg of [10B]BPA, and one hour later, tumours were irradiated with 30 min of thermal neutron irradiation. Three tumour-bearing mice were left untreated. Tumours were harvested one or seven days after treatment. MC38 tumours: Three tumour-bearing mice were irradiated with 4 Gy X-ray. Three tumour-bearing mice were intravenously injected with 100 mg/kg of [10B]BPA, and 1 h later, the tumours were irradiated with 20 min thermal neutron irradiation. Three tumour-bearing mice were left untreated. Tumours were harvested 5 days after treatment. The tumours were digested into single cells. Three tumours from the same group were combined into one sample. For B16F10 tumours 7 days after treatment, cells were stained with anti-mouse CD45 FITC (147710, BioLegend) and sorted via flow cytometry (BD FACSAria III Cell Sorter). CD45+ immune cells were enriched at a ratio of CD45- to CD45+ of 1:2. Libraries were constructed using the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kit v3.1 (10x Genomics), and immune repertoire measurements were conducted via the Chromium Single Cell V(D)J Reagent Kit (10x Genomics) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were sequenced as paired-end 150-base reads on an Illumina HiSeq-X platform.

Single-cell RNA-seq data preprocessing

Here, we performed analyses of the single-cell sequencing data derived from MC38 (mouse-derived) and B16F10 (mouse-derived) samples separately. Newly generated single-cell sequencing data were aligned with the mm10 mouse reference genome and quantified via Cell Ranger (version 7.1, 10x Genomics Inc.). The cells with fewer than 200 genes detected and a mitochondrial unique molecular identifier (UMI) count percentage larger than 10% were filtered out. The genes detected in less than three cells were also filtered out. To remove the potential doublets, Scrublet53 was used for each sample with the expected doublet rate set to be 0.05, and cells with the predicted doubletScore larger than 0.3 were further filtered out. We next normalized the count data using the normalize_total function with the default parameter in Scanpy54. All the normalized data were logarithmically transformed for downstream analyses. Highly variable genes (HVGs) were selected, and principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the matrix of HVGs to reduce noise using the scanpy.tl.pca function. The batch effects were corrected by the Harmony55 algorithm, in which the parameter of the scanpy.external.pp.harmony_integrate function was set to “batch_key=’sample”. The nearest neighbours distance matrix was calculated with the scanpy.pp.neighbors function and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) was employed for visualization via the scanpy.tl.umap function with default parameters. Using the scanpy.tl.leiden function, we performed two rounds of unsupervised clustering to reveal the structure of whole-cell and single-cell populations, such as cancer cell and T-cell populations.

Single-cell RNA-seq data cell-type annotation

To define the main cell types, we categorized the cells according to commonly used cell markers: Col1a2 for fibroblasts, Pecam1 for endothelial cells, Ptprc for immune cells, Cd8a for CD8+ T cells, Cd4 for CD4+ T cells, Klrk1 for NK cells, Cd79a for B cells, Itgam for myeloid cells, Fcn1 for monocytes, Cd68 for macrophages, and H2-Ab1 for dendritic cells. Specifically, to identify the cancer cells, we used Mlana and Pmel for the B16 tumours and Epcam for the MC38 tumours. Furthermore, the infercnvpy Python package was used to infer somatic Copy Number Variation (CNV) in which fibroblast, endothelial, and immune cells were labelled with a normal background for calling CNVs.

Differential gene expression and pathway enrichment analysis

We performed differential gene expression analysis of different cellular populations by using scanpy.tl.rank_genes_groups. Next, we performed the pathway enrichment analysis of those differentially expressed genes using the enricher function of cluster-Profiler V4.6.256 (Gene Ontology gene sets or cancer hallmark gene sets from MSigDB).

Calculation of the signature score and definition of gene sets

We used the sc.tl.score_genes to calculate the signature score of a specific gene set. The antigen processing and presentation gene set was obtained from the GO:0030333 of Gene Ontology. The MHC class 1-related gene set was defined as H2-K1, H2-Ke6, H2-D1, H2-Q4, H2-T23, and H2-T22. The activation and exhaustion gene sets of CD8 T+ cells were obtained from a previous study that uncoupled the dysfunction and activation gene modules in tumour-infiltrating T cells57. The natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity gene set was obtained from the GO:0042267 of Gene Ontology.

TCR analysis

The TCR sequences for each single cell, derived from 10x Genomics data, were processed via Cell Ranger (version 7.1) with the manufacturer-provided mouse V(D)J reference genome. For all assembled TCR contigs, we excluded those that had low-confidence, were nonproductive, or had UMIs < 2. A TCR clone was defined as a combination of the same TCRα chain and TCRβ chain, sharing identical V and J gene segments and the same CDR3 amino acid sequence. TCR clones with more than two cells were classified as expanded.

Cell cycle analysis

At the designated time points, the adherent cells were harvested post-treatment. The Propidium Iodide Flow Cytometry Kit (ab139418, Abcam) was used to distinguish cell cycle stages on basis of the cellular DNA content, following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunofluorescence

Tumour tissues were prepared as cryostat sections. The sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and treated with a permeabilization solution containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature, and then stained with the following primary antibodies: phospho-histone H2A.X (Ser139) antibody (9718S, CST, 1:200, clone number 20E3), anti-HMGB1 polyclonal antibody (ab18256, Abcam; 1:200), anti-Calreticulin polyclonal antibody (ab2907, Abcam, 1:200) or CD8a monoclonal antibody (14-0081-82, Invitrogen; 1:200, clone number 53-6.7), as well as the secondary antibody anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (4412S, CST; 1:1000). The samples were mounted with anti-fluorescence quenching sealing tablets (G1407, Servicebio) containing 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and then imaged using a fluorescence microscope (IX73, Olympus). The visual fields were randomly selected and analyzed via ImageJ (version 1.53a).

Multiplex IHC staining was performed on 4-mm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded slides using an Opal multiplex IHC system (20241001kit, Lifty) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After slide preparation and heat-induced epitope retrieval, the slides were blocked with Lifty Antibody Diluent Block buffer. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (ab217344, Abcam, clone number EPR21769), anti-CD11c monoclonal antibody (ab219799, Abcam, clone number EPR21826), anti-MHC class II monoclonal antibody (14-5321-82, Invitrogen, clone number M5/114.15.2), and anti-F4/80 monoclonal antibody (70076 T, CST, clone number D2S9R). Each slide was baked in the oven at 75 °C for 1 h. Then, the slides were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol solutions. After antigen retrieval in a microwave, the slides were washed with TBST wash buffer. After blocking, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h and then incubated with the polymer HRP Ms+Rb as the secondary antibody for 10 min at room temperature. Opal fluorophores were pipetted onto each slide for 10 min at room temperature, and the slides were microwaved to strip the primary and secondary antibodies. We then repeated the same protocol using the next primary antibody target. Finally, at room temperature, DAPI was pipetted onto each slide for 10 min. The slides were covered with Lifty-BD-FM-1, and images were taken using an AKOYA automated quantitative pathology system. The images were analysed by inForm 2.8.0 software (Akoya Biosciences, Inc., USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Blood was collected via the ocular method, and ELISA assays for IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ were performed on mouse serum using LumiKine Xpress mIFN-α 2.0 (luexmifnav2, Invitrogen), LumiKine Xpress mIFN-β 2.0 (luexmifnav2, Invitrogen), and the IFN-γ pre-coated ELISA kit (430807, BioLegend) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

BMDCs and T cells co-culture

BMDCs were generated by culturing bone-marrow cells in the presence of 20 ng/mL recombinant murine GM-CSF (315-03-250 μg, PeproTech) and 200 ng/mL recombinant murine Flt3 (250-31L-250μg, PeproTech) for 7 days. Then the BMDCs were treated with B16F10 cells in transwell (140652, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 2.5 × 105 BMDCs and 5 × 104 tumour cells per well. After 72 h incubation, cells were sorted, and surface markers CD80/86 were analysed on flow cytometry using anti-mouse CD80 Brilliant Violet 650 (104732, BioLegend), anti-mouse CD86 PE (105007, BioLegend). OT I CD8+ T cells were isolated from spleens using CD8+ T cell isolation kit (130-104-075, Miltenyi Biotec). T cells were then co-cultured with 500 μg/mL OVA (A5503, sigma) and BMDCs at 8:1. After 72 h incubation, T cells were analysed after staining with anti-mouse CD3-PE (100206, BioLegend), anti-mouse CD25-PE/Cyanine 7 (102016, BioLegend), and anti-mouse CD69-BV421 (104545, BioLegend) by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Tumour tissues were dissociated as described above to obtain single-cell suspensions for detecting cell viability (immune cells and non-immune cells), T cells, and dendritic cells. The cells were labelled with the Zombie Aqua Fixable Viability Kit (423102, BioLegend) in PBS and blocked with anti-mouse CD16/32 (101302, BioLegend). Surface staining was performed on ice for 30 min, followed by a wash with FACS buffer (PBS + 2% FBS) and resuspension in FACS buffer for analysis on a BD LSRFortessa X-20 Cell Analyzer. All the data were analyzed using FlowJo (version 10). To assess the viability of immune cells or non-immune cells in tumours treated with or without BNCT, single-cell suspensions were stained with anti-mouse CD45 FITC (147710, BioLegend). For DCs, single-cell suspensions were stained with the following anti-mouse antibodies against: anti-mouse CD45 FITC (147710, BioLegend), anti-mouse I-A/I-E Brilliant Violet 421 (107632, BioLegend), anti-mouse CD11c APC (117310, BioLegend), anti-mouse Ly-6C PerCP/Cyanine5.5 (128012, BioLegend), anti-mouse F4/80 Alexa Fluor 700 (123130, BioLegend), anti-mouse CD80 Brilliant Violet 650 (104732, BioLegend), anti-mouse CD86 PE (105007, BioLegend). For T cells, the following antibodies were used: anti-mouse CD3 PE (100206, BioLegend), anti-mouse CD4 FITC (100510, BioLegend), and anti-mouse CD8a APC (100712, BioLegend). For memory cells in mouse blood, spleen, and lymph nodes, the single-cell suspensions obtained were processed similarly and stained with the following anti-mouse antibodies against: anti-mouse CD3 PE (100206, BioLegend), anti-mouse CD4 FITC (100510, BioLegend), anti-mouse CD8a APC (100712, BioLegend), anti-mouse/human CD44 Brilliant Violet 605 (103047, BioLegend), and anti-mouse CD62L Brilliant Violet 421 (104436, BioLegend). The catalogue numbers of the antibodies used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

The data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Software (version 10).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are included in the Supplementary Information or available from the authors, as are unique reagents used in this Article. The raw numbers for charts and graphs are available in the Source Data file whenever possible. The single-cell RNA-seq data have been deposited in Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) database under the PRJCA038841 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA024829]. The MALDI-TOF data have been deposited in iProX database under the PXD063226 [https://www.iprox.cn//page/project.html?id=IPX0011728000]. The FACS data have been deposited in Flow Repository under the FR-FCM-Z9G8. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

No software or algorithm was generated in this study. The analysis codes have been uploaded to GitHub, https://github.com/Qi-1111/BNCT_scripts.

References

Schaue, D. & McBride, W. H. Links between innate immunity and normal tissue radiobiology. Radiat. Res. 173, 406–417 (2010).

Herrera, F. G., Bourhis, J. & Coukos, G. Radiotherapy combination opportunities leveraging immunity for the next oncology practice. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67, 65–85 (2017).

Barker, H. E., Paget, J. T. E., Khan, A. A. & Harrington, K. J. The tumour microenvironment after radiotherapy: mechanisms of resistance and recurrence. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 409–425 (2015).

Lynch, C., Pitroda, S. P. & Weichselbaum, R. R. Radiotherapy, immunity, and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lancet Oncol. 25, e352–e362 (2024).