Abstract

Layered transition metal oxide cathodes (NaxTMO2) demonstrate a classic type of cathode for Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs), however their practical application faces a long-standing challenge of irreversible phase transitions at high voltages, which causes unsatisfied specific energy and cycling stability, particularly for P-type (Na+ located at prismatic sites) cathodes. This phenomenon is conventionally ascribed to the Na+ re-coordination from prismatic to octahedral (O-type) configuration upon Na+ extraction, whereby the TMO2 slab gliding and abrupt c-lattice change are always coupled, and a straightforward solution to this situation remains elusive. Here, we reveal that, the TMO2 slab gliding and the lattice contraction can be decoupled, and the rapid lattice contraction under high state-of-charge underlies the fundamental origin for the irreversible phase transitions. By pre-engineering 15.8% O-type stacking faults to a P-type Na0.7Mn0.8Ni0.2O2, the dramatic volume variation and irreversible phase transitions at high voltage (4.5 V vs. Na+/Na) can be primarily eliminated. This work advances the understanding on the phase transitions at deep desodiation states, and paves up a feasible way to realize high-energy layered oxides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) based on earth abundant resources demonstrate great application potential in grid-scale energy storage or fast charging scenarios, attributed to their low cost and fast charging ability1,2,3. Layered transition-metal oxides (NaxTMO2, TM refers to transition metals) with high theoretical capacities and good processability, have been well explored as SIB cathode materials, which can be generally classified into different types according to the coordination of Na (trigonal prismatic: P-type or octahedral: O-type) and the stacking of the oxygen layers (e.g., P2:ABBA or O3:ABCABC)4,5,6. The P-type materials with an open prismatic structure allow fast Na+ transportation and are inherently more stable than their O-type counterparts, however, their practical applications have to deal with one primary challenge of uncompetitive specific energy, attributed to their relatively low Na content (x is typically between 0.67 and 0.78)7,8. Even worse, the full charge storage capacity of these cathode materials cannot be fully utilized primarily because they undergo deteriorated P-type to O-type phase transitions along with a very large volume change at Na-depletion states (high SOC, Supplementary Fig. 1)9,10.

The irreversible P-to-O phase transition is characterized by the gliding of the transition metal oxide (TMO2) slabs associated with a re-coordination of the Na+ ions from P-type to O-type, as well as a dramatic contraction of the unit cell along the c-axis11,12,13. Typically, the gradual removal of Na+ will decrease the Na shielding and present face-to-face O2− ions between adjacent TMO2 layers, which causes escalated O2−–O2− electrostatic repulsion and a continuous expansion of the NaO2 layer spacing. At high SOC, this expanded spacing is maintained solely by the repulsive forces between O2− ions, which further precipitates the gliding of TMO2 slabs to form thermodynamically stable O2-type stacking faults (SF). Such a process is invariably accompanied with a rapid and significant c-drop and a volume shrinkage of ~20%, thus triggers severe particle fragmentation and the consequent capacity decay upon cycling, especially at high SOC. A more reversible phase transition from P2 to OP4/Z phase can be induced at high SOC by introducing specific elements (Li+14, Ti4+15, Mg2+16, Zn2+17, Sb5+18, Ca2+19, etc.) or TM vacancies into the TMO2 layer. These OP4 or Z phases are considered to feature with O/P-type intergrowth phase, wherein the ratios between P-type layer and O-type layer vary with the charging/discharging potentials and cycles20,21. However, from the aspect of a single slab, a sudden c-drop and volume change still happen, which can cumulatively lead to inevitable structural failure at a cut-off voltage (usually > 4.3 V) or after prolonged cycling. This casts some fundamental questions: how can the abrupt P-to-O phase transition or the related lattice contraction be avoided at the level of individual slabs? Is there a straightforward way to decouple the TMO2 slab gliding from the lattice contraction?

In this work, we break away from the conventional views by pre-engineering 15.8% O-type SF to a P-type Na0.7Mn0.8Ni0.2O2, and investigate the structural origin of the P-to-O phase transition and the accompanied chemo-mechanical structural degradations. We provide substantive evidence that the TMO2 slabs gliding and the volume change can be largely decoupled, while the significant c-axis expansion upon Na+ extraction and abrupt lattice contraction at high SOC serve as the primary drivers for the irreversible phase transitions. Distinguished from the SF formed during electrochemical charge/discharge, which could damage the structural stability, the pre-engineered SF in P-type layered oxides characterized with large interlayer distance (~5.6 nm) and O-type coordination, can avoid the presence of face to face O2− ions at high SOC, leading to minimal c-axis expansion during the Na+ extraction, which eventually eradicated the irreversible P2 to O2 phase transition. The as-prepared SF-rich Na0.7Mn0.8Ni0.2O2 (SF-NaMN) delivers an specific energy of 635 W h kg−1 (based on cathode materials), and the as constructed hard carbon||SF-NaMN full cell demonstrates a specific energy of 297 W h kg−1 (without presodiation) with capacity retention of ~80% after 600 cycles. A pouch cell and an all-solid-state sodium batteries were also assembled (without presodiation), which demonstrate high specific energy and stable cycling performance. This work clarifies the long-standing puzzle for the origin of P to O phase transition, and paves the way to rationally design high-voltage NaxTMO2 cathodes by the virtue of stacking-faults engineering.

Results and discussion

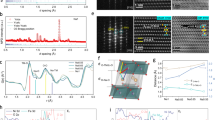

Designing of SF rich P2-type layered oxides

This work aims to decouple the TMO2 slab gliding from the c-lattice contraction, which generally happens co-currently during the charging and discharging process. To disrupt this inherent correlation, one can consider pre-establish certain amounts of O-type slabs into P-type layered structure with unchanged interlayer distances (O–Na–O). Conventionally, O- or P-type phases can be generally achieved by adjusting the cationic potentials through introducing different hetero elements3,4,19,22,23, but such strategies inevitably lead to varied c-lattice spacing (e.g., O3: 0.53–0.54 nm, O2: 0.44 nm, P2: 0.56–0.57 nm). In this work, we focus on the typical Mn-Ni-based P2-type cathode and intentionally disrupt the Mn-Ni ordering by manipulating the co-precipitation process of the (MnNi)CO3 precursor (see details in Supplementary Note 1). We refer the concept of the “cationic potential (Φ)”1 to elucidate how these O-type SF with remained c-parameter can be created in P2-layered oxides. Previous studies have proposed an empirical relationship (y = 0.4065x + 1.572), which is regarded as the P–O phase dividing line (PDL). According to this equation, the compounds with different composition would exhibit distinct cationic potentials, leading to different Na coordination modes contingent upon their position relative to the PDL. Further extending this description, we can draw lines parallel to the PDL, whereby the layered oxides on these parallel lines present similar coordination environments, termed “equal coordination lines” (ECL) in this article. It can be reasonably deduced that the compounds positioned on ECLs closer to the PDL are more likely to form P/O biphasic materials, whereas those far from the PDL tend to yield pure P-type or O-type phases. To validate this hypothesis, we calculated the cationic potentials of those P/O biphasic oxides reported from literature, which are all confirmed situated in the O–P biphasic region (Supplementary Fig. 2; Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We then applied this analysis to individual TMO2 slabs. The calculated cationic potentials of Na0.7Mn1−xNixO2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5, Fig. 1a) reveals that the Φ values vary with the Mn:Ni ratio with such a sequence: Φ(Na0.7Mn0.7Ni0.3O2) > Φ(Na0.7Mn0.5Ni0.5O2) > Φ(Na0.7Mn0.8Ni0.2O2) > Φ(Na0.7Mn0.6Ni0.4O2) > Φ(Na0.7Mn0.9Ni0.1O2) > Φ(Na0.7MnO2) with ECLs approaching the PDL line. Therefore, if the Ni/Mn elements are unevenly distributed in Na0.7Mn1−xNixO2, those Mn-rich TMO2 slabs could induce O-type Na coordination occasionally, which demonstrate the structural origin of the large amount of O-type SF formed in SF-NaMN. With this mind, the Na0.7Mn0.8Ni0.2O2 layered oxides with pre-constructed SF (denoted as SF-NaMN) were synthesized by regulating atomic arrangement of Mn and Ni ions (more detailed information are presented in “Methods”, Supplementary Note 1; Supplementary Figs 3 and 4). Laboratory and synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction patterns (XRD) show that SF-NaMN patterns exhibit obvious diffraction peak broadening on (10 l) (e.g., (102), (103), (104), and (106)) planes, but the peaks of (00 l), (h00) and (hk0) remain sharp (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 3), indicating that SF-NaMN has a structural integrity along the ab-plane. Generally, the diffraction peak broadening can be originated from the crystallites size decrease, the presence of microstrain or certain type of defects etc24,25,26,27. Herein, we applied Williamson–Hall equation (W–H) to probe the origins for peak broadening of (10 l) facets in SF-NaMN28,29,30. The fitted line of (10 l) facets of SF-NaMN deliver a slope of 1.51%, which is 0.1% for the other facets with a line almost parallel to the x-axis in SF-NaMN, and 0.21% for all diffraction peaks of NaMN (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Tables 4; 5 and Supplementary Note 2). This indicate that, the broadening of the (10 l) peaks should be attributed to the presence of SF along the (00 l) facets in SF-NaMN. Furthermore, the percentage of the SF has been calculated as 15.8% according to the equation:

a The cation potential phase map of Na0.7Mn1−xNixO2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5). b X-ray diffraction of SF-NaMN and NaMN, the normalization methodology is min-max normalization, feature scaling to the [0, 1] range. c Williamson–Hall plots of SF-NaMN and NaMN. d Comparison of anion-anion distances in octahedral and prismatic environments of sodium-based layered oxides. Here, d(O–Na–O) and d(O–O) interlayer distances denote the perpendicular distances and straight-line distance between the two oxygen layers, respectively. In this case, the cation-anion distance is considered to be determined by the ionic radii of the cation (r+) and anion (r−), while the in-plane anion-anion distance is governed by the ionic radius of the anion.

\(\beta \frac{\cos \theta }{\lambda }=\frac{0.89}{D}+\frac{1}{2c}\frac{\cos \theta }{\lambda }\cos {\varphi }_{z}4f\) (detailed information described in “Methods”). As contrast, NaMN did not show the peak broadening on (10 l) planes. The Rietveld refinement of XRD patterns of SF-NaMN and NaMN reveals that the c-axis of the SF-NaMN (11.187 Å) exhibits a slight contraction (0.456%) in comparison to the that of NaMN (11.238 Å) (Supplementary Fig. 6; Supplementary Tables 6 and 7), which may be induced by SF. Significantly, no characteristic peaks for O3-type structure were detected, evidencing that the O–Na–O interlayer distance at the O-stacking faults remain the same with the P-type structure. Figure 1d illustrates the P- and O-type configurations with the O–Na–O interlayer distance unchanged. It can be calculated that, under the same O–Na–O interlayer distance, the O–O distance across the intercalant layer will always be longer in O-type than P-type configurations31. Henceforth, the O2−–O2− electrostatic repulsion in the O-type SF can be significantly reduced upon Na+ extraction, which may avoid abrupt lattice contraction, and offers the possibility to decouple the TMO2 slab gliding and the lattice contraction.

Structural characterization

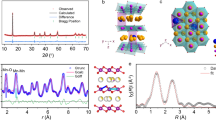

The morphology and microstructure of the samples were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Supplementary Fig. 7) and aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 2a–d and Supplementary Fig. 8). Grains projected along the [100] zone axis were observed, with the large bright spots representing TM atom columns, but light elements, such as Na and O, are not detectable. Notably, a series of periodic regular SF can be found in SF-NaMN (orange box) with interlayer distance of 5.56 Å at stacking fault position, and 5.65 Å for other P-type layers (Fig. 2a). The space distances of the lattice fringes for NaMN are 5.70 and 2.57 Å corresponding to the (002) and (100) plane, respectively (Fig. 2b). The atomic-level structural information along the [001] zone axis further confirmed both TMO6 octahedron of SF-NaMN and NaMN aligned in a hexagonal symmetry arrangement (Fig. 2c, d). The vision of SF in SF-NaMN can be clearly distinguished in [001] direction, which shows ordered honeycomb structure. The bright spots in blue circles represent TM atoms occupied 2a sites of P2-layered hexagonal structure, while the slight spots (green and orange lines) correspond to TM atoms at octahedral 2b sites in SF slabs (Fig. 2c, inset). These SF should be caused by the gliding of a TMO2 slab along [1/3, 2/3, z] or [2/3, 1/3, z] direction, leading to the coordination environment change of Na+ from trigonal prismatic position to octahedral positions. Besides, the horizontal distances between adjacent TMO6 octahedron of SF-NaMN under different signal intensities are similar (5.03 Å), indicating the gliding of TMO2 slabs induced by SF remain integral P2-type structure without obvious variation in atomic spacing (Fig. 2c). As contrast, the horizontal distance between TMO6 octahedron of NaMN is ~5.10 Å without extra signals generated from [001] projection, indicating single-crystalline hexagonal structure of NaMN without obvious SF (Fig. 2d). According to the above structure features observed, we built structural models to understand the special atomic arrangement of SF-NaMN (Fig. 2e, f). It indicates that the P2-Na0.7Mn0.8Ni0.2O2 lattice and O-type SF are compatibly combined by sharing identical closely packed O sublattices in a pseudo-hexagonal scheme, which matches well with the STEM atomic pattern. Notably, the interlayer distance of TMO2 slabs at stacking fault layer in SF-NaMN is close to that the P-type phase (5.56 Å v.s. 5.65 Å), which different from the noticeable decrease in interlayer distance of (002) facet observed in O2 phases (4.3–4.4 Å) during deep desodiation process13. Further characterizations were conducted to explore the possible mechanism for the formation of such SF rich structure. Atomic-resolution energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mappings (Fig. 2g–j) were conducted to distinguish the distribution of Mn and Ni atoms within each sample beneath the projected atomic columns. By comparing the counts of EDX spectra, the ratios of transition metals at the two SF region are approximately Mn:Ni = 0.815:0.185 and 0.789:0.211; as well as 0.789:0.211 and 0.805:0.195, respectively. These values correspond to a to d TMO2 slabs (counted from top to bottom in Fig. 2h). The ionic potential differences of the transition metals between the two layers at the stacking fault are 0.3552, and the cationic potential difference is 0.08532 with constant Na content (0.7) (Supplementary Fig. 9). It is revealed that Mn atoms demonstrate enhanced intensity at SF accompanied with weakened Ni intensity (Fig. 2h), suggesting that there is a variation of Mn-Ni contents among different TMO2 slabs in SF-NaMN. The obvious difference of Mn/Ni ratio at certain TMO2 slabs might be the fundamental origin of SF, which is consistent with our design. As contrast, NaMN sample shows homogeneous Mn and Ni distribution within each layer. (Fig. 2i, j).

a, b STEM-HAADF images of SF-NaMN and NaMN projected along the [100] zone axis. c, d STEM-HAADF images of SF-NaMN and NaMN projected along the [001] zone axis. e Corresponding simulated model of NaMN and SF-NaMN along the [100] zone axis. f Simulated structure of NaMN and SF-NaMN from [001] direction. Atomic EDS mapping of element distributions in the g SF-NaMN and i NaMN, and corresponding normalized element signal density of h, j Mn and Ni atoms along the [100] zone axes. k A section of neutron diffraction (ND) peaks of SF-NaMN and NaMN. The normalization methodology applied to fig h–k is min-max normalization, feature scaling to the [0,1] range.

The local structure of TM-ordering in SF-NaMN and NaMN was further examined by X-ray pair distribution function (PDF) and neutron diffraction (ND) patterns. The local distances of TM-O (orange curve), and TM-TM (green curve) were simulated by PDFgui software (Supplementary Fig. 10). It can be found that the short-range ordering of TM-TM pair of SF-NaMN has obvious decay compared with that of NaMN. Moreover, the TM-ordering reflections experience a noticeable decrease in SF-NaMN than that in NaMN, as evidenced by the reflections around 3.0–4.6 Å in (ND) patterns (Fig. 2k)32, which indicating that the TM (Mn-Ni) arrangement of SF-NaMN are obviously more disordered than that of NaMN. Combining the EDS-mapping and ND results, SF-NaMN synthesized by our methods could induce Mn atoms enriched in several layers of layer oxides, lead to the different TM contents and corresponding cationic potential between adjacent TMO2 slabs. The large cationic potential difference between adjacent TMO2 slabs give rise to non-equilibrium electrostatic repulsion of O2−–O2−, thus leading a couple of weakened Na–O bonds and a pair of strong Na–O bond3. In this case, Na+ occupation in P-phase trigonal prismatic position is unstable and tend to move to octahedral positions driving by non-equilibrium O–Na–O interaction, leading to the occurrence of O-type SF.

To verify the generality of this synthesis method, samples doped with varied metallic ions, such as Na0.74Mn0.75Ni0.2Li0.05O2, Na0.64Mn0.77Ni0.18Ti0.05O2, Na0.7Mn0.75Ni0.2Mg0.05O2, Na0.67Mn0.75Ni0.21Cu0.04O2, Na0.67Mn0.75Ni0.2Al0.05O2, Na0.69Mn0.74Ni0.19Fe0.07O2, Na0.73Mn0.76Ni0.18Zn0.06O2 were synthesized using the same method. The diffraction peak of (102), (103), (104) and (106) facets of these samples were also obviously broadened compared with their control samples (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 8), indicating that such a synthetic approach is viable to regulate the crystal structure of P2-phase materials with diversified compositions.

Electrochemical performance

The electrochemical performance of SF-NaMN and NaMN samples (Supplementary Data 1) was tested at varied potential ranges (vs. Na+/Na) using sodium metal as the anode (Fig. 3a–c). The as prepared SF-NaMN deliver a capacity of 130 mA h g−1 in the voltage range of 2.4–4.5 V (Fig. 3a), and 227 mA h g−1 in a wide voltage range of 1.5–4.5 V (Supplementary Fig. 12) at 0.1 C (1 C = 180 mA h g−1), corresponding to a high specific energy of 635 W h kg−1 (calculated based on active mass of the cathode material). The peak intensities of Na+/vacancy ordering (3.78/3.64 V) are significantly reduced for SF-NaMN compared to that of NaMN, suggesting that pre-constructed SF can effectively suppress the formation of Na+/vacancy ordered structures. The CVs and dQ/dV curves of SF-NaMN and NaMN show two pairs of redox peak in the high voltage region (4.11/4.38 V) corresponding to the Ni3+/Ni4+ and O2−/On− redox reaction5,6,29 (Supplementary Fig. 13), which is confirmed by ex situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Supplementary Figs. 14; 15 and Supplementary Note 3). The galvanostatic intermittent titration techniques (GITT) (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 16) results show no obvious drop on the DNa+ value (10−9.69 → 10−9.89 cm2 s−1) at high voltage (4.5 V) for SF-NaMN, evidencing the improved ion diffusion capability for SF-NaMN. On the contrary, NaMN experienced two orders of magnitude decrease (10−9.89 → 10−11.61 cm2 s−1) of the DNa+. Consequently, SF-NaMN demonstrates notable rate capability and cycling stability (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 17), with an initial discharge capacity of 93 mA h g−1 at 2 C and a capacity retention of 70% after 300 cycles at 25 °C, far surpassing to that of NaMN (37.6% retention after 300 cycles, Supplementary Fig. 18). The as prepared SF-NaMN also exhibits a promising cyclability at high temperature (50 °C) with a capacity retention of 86.1% after 100 cycles at 1 C, surpassing to that of NaMN (64%, Supplementary Fig. 19). The electrochemical performance comparison of cathode doped with varied metallic ions were also examined and summarized in Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21. The GCDs of Li, Ti, Mg, Zn, Cu, Al and Fe doped SF-NaMN cathodes show smoother charge-discharge curves in the high voltage range of 4.2–4.5 V, distinguishing from their corresponding control samples. Meanwhile, the rate performance, coulombic efficiency (CE) and cycling stability of these cathode oxides are further enhanced (Supplementary Fig. 22).

a Initial charge/discharge profiles of SF-NaMN and NaMN in the voltage range of 2.4–4.5 V. b Sodium ion diffusion coefficient (DNa+) of SF-NaMN and NaMN calculated from the GITT formula, the two histograms are the diffusion coefficients of SF-NaMN and NaMN at 4.5 V, respectively. c Long-term cycling stability of SF-NaMN and NaMN at rates of 2 C. d Initial charge-discharge curves of the full cell within 0.5–4.45 V of SF-NaMN and NaMN cathode with unpre-sodiated HC. e Cycling performance of HCups||SF-NaMN full cells within 2–4.2 V. f The comparison of the specific energy and working potential with other reported literatures7,20,21,22,23,24,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64, the capacity is calculated from the reported specific energy and average working potential in these literatures. g, i GCDs within 3.9–4.4 V. DRT contour image of h, HCups||SF-NaMN and j HCups||NaMN within 4.22–4.4 V at 0.1 C during the 1st cycle of charge and discharge process at 25 ± 2 °C. k Charge/discharge profiles of pouch cell of HC||SF-NaMN within 1–4.4 V. l Cycling performance of pouch cell of HCups||SF-NaMN full cells at 1 C charge/1 C discharge.

As has been established that P2-type electrodes usually deliver a low initial charge capacity of ~85 mA h g−1 below 4.0 V due to the low Na content (<0.75) in the molecular9,15, and a low average voltage <3.2 V because of the irreversible P to O phase transition at high voltage33,34, thus compromising the overall specific energy of the battery. Therefore, in order to achieve a decent specific energy, a troublesome pre-sodiation process or adding self-sacrificed additives becomes necessary for the full-cell construction of P2-type cathodes35,36,37. Considering the incredible reversibility of SF-NaMN under high voltage could enable more Na+ ions participate in the electrochemical reactions, full cells were assembled using unpresodiated hard carbon (HCups) as anode (HCups||SF-NaMN) (Supplementary Fig. 23). The as-equipped HCups||SF-NaMN delivered a high specific capacity of 115.5 mA h g−1 (calculated based on the active mass of cathode electrode) with initial CE of 82.4% at a high average operating voltage of 3.5 V at 0.1 C (Fig. 3d), and a high rate performance with 69.2 mA h g−1 capacity remain at 4 C (Supplementary Fig. 24). Most importantly, the HCups||SF-NaMN demonstrated a improved cycling stability at varied voltage ranges (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 25), the capacity retention maintained 96.2% and 87.3% within 1–4.4 V after 50, 100 cycles, and 77.3% within 2–4.2 V after 600 cycles at 1 C respectively with negligible voltage fade of GCD curves (Supplementary Fig. 26), far surpassing that 71.9%, 56.7% within 1–4.4 V after 50, 100 cycles and 67.2% within 2–4.2 V after 229 cycles) of HCups||NaMN. The specific energy of HCups||SF-NaMN was calculated as 297 W h kg−1 (based on the total active mass of both electrodes). Furthermore, a full cell with pre-sodiated hard carbon (HCps) and SF-NaMN (HCps||SF-NaMN) was also constructed (Supplementary Fig. 27), which delivered an specific energy of 303.7 W h kg−1 (based on the total active mass of both electrodes). The specific energy of both HCups||SF-NaMN and HCps||SF-NaMN is comparable to full-cells constructed with P2-layered oxide cathodes and presodiated HCs (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Table 9). A side-by-side comparison of full-cell performance was further conducted by re-synthesis several literatures reported materials and assembling full-cells under the exact same conditions, which suggesting enhanced high voltage and full-cell performance (without presodiation) (Supplementary Fig. 28 and Supplementary Note 4). Intriguingly, the SF-NaMN exhibits optimized compatibility with NASICON (Na3Zr2Si2PO12) solid electrolyte, which achieves a high specific energy of 437.6 W h kg−1 within 2.4–4.5 V (Supplementary Fig. 29). The all solid-state full cell can stably run at a high cutoff voltage of 4.2 V with retaining 81% of the initial capacity after 300 cycles at 0.5 C (Supplementary Fig. 29d).

To have an in-depth understanding on the electrochemical performance of SF-NaMN, the difference of the Na+ kinetic transport between SF-NaMN and NaMN at high voltage (>4.2 V) in the full cell system was systematically studied through the distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis, which employs a model-free approach to analyze impedance evolution. This mathematical transformation converts frequency-domain Nyquist plots into time-domain DRT spectra, enabling a model-independent assessment of electrochemical processes.

Peaks at specific relaxation times correspond to distinct electrochemical processes, while their respective areas quantify the associated impedance values. The relaxation time (τ) is the characteristic time scale required for a system to recover from a non-equilibrium state to an equilibrium state, which reflect the rate of electrochemical reactions or ion diffusion. The electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) are resolved by this analysis with different electrochemical processes38,39,40,41, six main peaks located at 10−6–10−4 (R0), 10−3–10−2 (Rfilm), 10−1–100 (Rct1, Rct2), 100–101 (ZW0), in accordance with ohmic resistance, resistance of solid electrolyte interphase (SEI), (refer to the film atop of anode) and cathode electrolyte interphase (CEI) (film, refer to the film atop of cathode), charge transfer resistance of anode material, charge transfer resistance of cathode material and Warburg resistance, respectively39,42,43. (high and intermediate/low frequency region etc) (Fig. 3g–j and Supplementary Fig. 30). As Na+ deep desodiated, Rct1 for HCups||SF-NaMN gradually increased and moved towards longer relaxation time, this could be attributed to the slow Na+ transport kinetics within the almost fully sodiated HC at 4.35–4.4 V39. Notably, the Warburg resistance (ZW0), which characterizes the bulk Na⁺ diffusion behavior, showed no obvious variation during the first cycle, indicating that the diffusion process remains relatively stable during charging process. The RCt2 and ZW0 resistance could return to their original response position during the discharging process. This reversibility of the impedance-derived parameters serves as compelling evidence for the optimized electrochemical reversibility exhibited by the HCups||SF-NaMN. In contrast, for the HCups||NaMN full cell, both Rct2 (charge transfer resistance of cathode material) and Warburg resistance (ZW0) increased significantly during charging process and can not completely recover during the discharging process, indicating the charge transfer and bulk Na+ diffusion process were severely inhibited by irreversible phase transition of NaMN.

A 0.5 A h pouch cell are assembled to further develop the practical potential application of SF-NaMN (Fig. 3k and Supplementary Table 10). Kilograms of SF-NaMN were synthesized to fabricate a pouch cell via the same condition as that used for the gram-level reaction kettle (Supplementary Figs. 31 and 32). Moreover, HC||SF-NaMN pouch cell can operate for 340 reversible cycles with >80% capacity retention within 2.0–4.2 V at a practical level (Fig. 3l), suggesting great practical potential of SF-NaMN. These results reveal that SF-NaMN exhibit enhanced Na+ kinetic transport capability at high voltage in the SIB full cell.

Investigation of the decoupling mechanism between slab gliding and lattice contraction

To understand the structural evolution of SF-NaMN and NaMN during the charge and discharge process, in situ XRD measurements are conducted. In situ XRD patterns illustrate that, the characteristic (002’) peaks at 20° and 17–19°, corresponding to O2 and OP4 phases, do not show during the charge and discharge process of SF-NaMN, indicating irreversible P to O phase transitions was not observed in SF-NaMN (Fig. 4a). Notably, a slight decrease in the intensity of the (104) peak at 39.75 degrees at the end of charging, demonstrating relative interlayer gliding between the TMO2 slabs happened, leading to atomic displacements and broadening of the (104) peak. However, the (002) peak did not shift, and no new peaks formed, indicating that no obvious interlayer contraction of SF-NaMN occurred during this process. The c-axis variation for SF-NaMN is calculated as 0.9% at 4.0 V, and 1.45% within 2.4–4.5 V (Supplementary Figs. 33–35). As a comparison, new peaks (the (002’) peak at 18.3° and (101’) peak at 37.9°)12 related to the OP4 structure were observed in the XRD patterns of NaMN at 4.25 V, which were enhanced with the increasing voltage, meanwhile, the P-phase peaks were gradually weakened, indicating a phase transition from P2 to Z occurred at high voltage region. Consequently, the NaMN shows an obvious c-axis expansion (2.7% at 4.0 V, 12.8% within 2.4–4.5 V, Fig. 4b, more detailed expression in Supplementary Note 5). Such terrible phase transition can trigger severe irreversible structural structure degradation, eventually unsatisfied electrochemical performance. HADDF-STEM examination visually evidenced the P/O stacking mode at the atomic scale of SF-NaMN and NaMN when charged to 4.5 V. For SF-NaMN, although some TMO2 slabs undergone relative gliding, while the TMO2 slab still maintains interlayer distance of 5.3–5.7 Å, consistent with P2-type structure (Fig. 4c). In contrast, two types of interlayer distances can be statistically depicted in NaMN, with ~5.7 Å (P2-type) and ~4.6 Å (O2-type) in the highlighted image of Fig. 4d. The formation of O-type structure of NaMN can be ascribed to the rapid c-parameter contraction and subsequent P–O phase transition during deep desodiation. Thus, NaMN undergoes a severe irreversible P2–Z phase transition at 4.5 V, while SF-NaMN remains a P2-type structure without any phase transition, which is consistent with the in situ XRD results. Moreover, geometric phase analysis (GPA) SF-NaMN exhibits significantly attenuated interlayer force changes, as evidenced by its uniformly distributed weak structural strain (Supplementary Fig. 36). In stark contrast, pristine NaMN shows severe strain localization with disordered strain vectors, which correlates with uncoordinated gliding and contraction of TMO2 slabs. Therefore, although 15.8% TMO2 slabs have been pre-glided from P to O position, no significant c-contraction was observed in SF-NaMN. In this sense, the traditional correlation between TMO2 slab gliding and c contraction has been decoupled.

a, b intensity contour maps of in situ XRD patterns corresponding to the charge and discharge curves at 0.1 C between 2.4 and 4.5 V of the Swagelok cell of SF-NaMN and NaMN at 25 ± 2 °C. c, d STEM-HAADF images of SF-NaMN and NaMN after 10 cycles at 0.1 C and stopped at 4.5 V along [100] projection. e The desodiation configurations and the corresponding energies of Na9Mn24Ni6O60 (Na0.3Mn0.8Ni0.2O2) for SF-NaMN and NaMN. f The variation of c-axis during desodiation (from Na21Mn24Ni6O60 to Na6Mn24Ni6O60) of SF-NaMN and NaMN. g Theoretical calculation of TM gliding energy of optimized SF-NaMN structure and NaMN with the stoichiometry of Na6Mn24Ni6O60 (Na0.2Mn0.8Ni0.2O2). h Schematic of O-type stacking fault strategy on suppressing P2-O2 phase transition in the P2-type layered oxides.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Supplementary Data 2–6) were conducted to understand the relationship between SF and P-to O-phase transition. Two model systems, Na21Mn24Ni6O60 (Na0.7Mn0.8Ni0.2O2) with homogeneous Ni/Mn distribution structure (representing NaMN), and Na21Mn24Ni6O60 with inhomogeneous Ni/Mn distribution (representing SF-NaMN) were established based on the structural investigation results in Figs. 1 and 2. Specifically, a Mn-rich TMO2 slab was constructed to represent the Mn-rich and Ni-deficient character of TMO2 slabs, according to the EDS mapping result of SF-NaMN. The optimal structures of NaMN and SF-NaMN before desodiation have been investigated. The structural model of SF-NaMN with perfect P2-type input structure showed SF during the structural optimization process. The stacking faults occurred near the Mn-rich TMO2 slab, and the density is 16.7%. However, no SF are observed during the structural optimization process of NaMN with a perfect P2-type input structure (Supplementary Fig. 37). These indicate that SF exist for SF-NaMN. In contrast, NaMN is free from stacking faults before desodiation. Furthermore, the stacking faults located between two adjacent Mn0.8Ni0.2O2 slabs within SF-NaMN have been examined. Interestingly, the stacking fault between two adjacent Mn0.8Ni0.2O2 slabs is unstable, and eventually evolved to reside between MnO2 and Mn0.8Ni0.2O2 slabs after the optimization process, indicating that SF in SF-NaMN might be induced by the variation in TM content between adjacent TMO2 slabs, which in accordance with HADDF-STEM and EDS results.

Then, the role of SF in SF-NaMN on the structural evolution during desodiation processes was studied. Na9Mn24Ni6O60 (Na0.3Mn0.8Ni0.2O2) was established for studying the desodiation states of SF-NaMN and NaMN, with sodium content roughly equivalent to when the material is charged to 4.25 V (Fig. 4e; Supplementary Fig. 38 and Supplementary Note 6). The most stable desodiation configuration for NaMN is achieved through the uniform extraction of Na+ ions from each sodium layer. However, the desodiation configuration for five out of twelve Na+ extracted from the SF slab shows the minimum energy (−628.90 eV) in SF-NaMN (Fig. 4e), suggesting that Na+ is prone to be extracted from the SF slabs in SF-NaMN. This phenomenon can be attributed to the varying compositional characteristics of the TMO2 slabs in relation to their proximity to the SF slab. The SF slab, which is in close proximity to the TMO2 slab with Mn3+/4+ redox couples at low voltage, would show a preference for Na+ extraction. The variation in the c-parameter for a deeper desodiation state Na6Mn24Ni6O60 (Na0.2Mn0.8Ni0.2O2) has been investigated. The variation of the c-parameter from Na21Mn24Ni6O60 to Na6Mn24Ni6O60 for SF-NaMN is 0.097%, which is significantly lower than that of NaMN (1.39%), indicating that SF could effectively inhibit the expansion of c-parameter during desodiation (Fig. 4f). These results agree well with the in situ XRD results in Fig. 4a. We also constructed the models with SF of 8.33% and 12.5% and demonstrated that as stacking fault density decreases, the of c-axis variation of the structure during desodiation gradually increases (Supplementary Figs. 39; 40 and Supplementary Note 7).

The TMO2 slab gliding behavior of TMO2 slabs in Na6Mn24Ni6O60 (Na0.2Mn0.8Ni0.2O2) for SF-NaMN and NaMN along [1/3, 2/3, z] direction were further simulated. It should be noted that the slab gliding energy is calculated as the energy of the structure after gliding minus the energy of the structure before gliding, and this energy value is closely related to the propensity of the material to undergo the P–O transition: a lower energy value indicates that the slab structure is more likely to glide, and thus the material is more prone to transform from P-type to O-type. From the simulation results, the gliding energies for slab-1 and slab-2 are 0.249 and 0.375 eV of SF-NaMN, respectively, which are much greater than the energy required of slab-3 (−0.449 eV) of NaMN (Fig. 4g), indicating that NaMN is more prone to undergo a transition from P-type to O-type under deep desodiation.

Moreover, we successfully achieved a cathode with 12.1% SF by increasing the precipitation pH of the precursors to 9.62. The synthesized sample exhibited a noticeable slope change in their electrochemical profiles at the high voltage plateau of 4.2 V, and the capacity retention was obviously improved compared with NaMN (Supplementary Fig. 41 and Supplementary Note 8). Therefore, pre-constructing SF in P2-type lattice structure is an effective strategy to enhance the cycle life of the cathode material.

The Na+ desodiation behavior and evolution of the P–O phase transition for SF-NaMN and NaMN is schematically illustrated in the Fig. 4h. Previous work has reported that the escalating O2−–O2− electrostatic repulsion would lead to the expansion of the Na layer spacing with Na+ gradually extracted, and oversized Na slabs fail to sustain the P-type structure, thus lead to the re-coordination of Na+ to form thermodynamically stable O-type stacking, accompanied by the sudden c-parameter contraction4,5,8. In our work, the interlayer spacing for the pre-constructed O-type SF in SF-NaMN is ~5.56 Å as evidenced by the experimental results (Fig. 2a), which is similar with that of the P2 phase (~5.65 Å). Therefore, the O–O bond in the adjacent transition metal layer is elongated at the SF layer leading to a significant decrease in the electrostatic repulsion between O2−–O2−. As a result, the interlayer distance increasing caused by the O2−–O2− repulsion during Na+ extraction becomes not obvious in SF-NaMN, leading to negligible tensile strain between the adjacent TMO2 slabs and thus avoiding the sudden c-drop of the materials. In contrast, the control sample (NaMN) experiences strong O2−–O2− repulsion between adjacent TMO2 slabs during Na+ desodiation, resulting in the stretched prismatic Na+ coordination, which eventually induces the sudden cell contraction and subsequent phase transition upon a large amount of Na+ extraction. Therefore, we have significantly decoupled slab gliding within the material from lattice contraction by pre-engineering O–SF with large interlayer distance in the P2-type structure, demonstrating a much smaller c-axis contraction of the SF-NaMN with slabs gliding relative to NaMN (0.456% vs. 12.8%, respectively), with the contraction of SF-NaMN occurring prior to electrochemical desodiation. The phase transition at high SOC can be avoided under the presence of plenty of O-type coordination, as long as the sudden c-drop doesn’t occur.

Investigation of structural evolution during cycling

According to previous reports, the irreversible P–O phase transitions of P2-type layered oxide cathode during the high voltage region can induce grain cracking, TM ions dissolution, and severe side reactions between the cathode material and high oxidizing molecules in the electrolyte solvent4,5,44. The structural evolution of SF-NaMN and NaMN after cycling was monitored using HADDF-STEM (Fig. 5a–f and Supplementary Fig. 42). The SF-NaMN and NaMN electrode are tested with specific current of 0.2 C in 2.4–4.5 V vs. Na+/Na. It can be observed that the layered structure of SF-NaMN retained well with only a small amount of strain relaxation disclosed by the GPA after 30 charge/discharge cycles, showing an interlayer spacing of 5.67 Å (Fig. 5a–c). On the contrary, the cycled NaMN demonstrated obvious microcracks and surface degradation, as well as a severe Na+/TM intermixing rock-salt phase (Fd3m) with a perplexing strain distribution growing along the (00 l) facets (Fig. 5d–f, more detailed information in Supplementary Note 9). The CEI structure of SF-NaMN and NaMN after 30 cycles were detected by the time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS). The TOF-SIMS depth profiles reveal the inorganic species (NaF−) and organic species (CHO2−) showed obvious segregation and with fewer organic species than inorganic species constituting the surface of the CEI of SF-NaMN (with sputtering time <60 s, Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 43), while no apparent segregation was observed between inorganic species (NaF−) and organic species (CHO2−) on the surface of NaMN (Fig. 5i). Noting that, the thickness of the CEI in the SF-NaMN is only two of third of that in NaMN according to the half-normalized maximum of the normalized intensity of the CEI species. Moreover, NiF3− and MnF3− fragments mainly comes from the cathode oxide dissolution driven by acidic attack (HF, etc). NaMN exhibit obviously stronger NiF3− and MnF3− intensity than that of SF-NaMN, confirming severe transition metal dissolution and cross-contamination of NaMN after cycling (Fig. 5h, j)45. Energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDX) of the elemental information on the Na anode reveals that the residual TM element signals in SF-NaMN (Mn: 1.37%, Ni: 1.16%) are significantly weaker than those in NaMN (Mn: 0.23%, Ni: 0.4%), also indicates that the TM dissolution in SF-NaMN has been significantly suppressed (Supplementary Fig. 44). The TEM results further confirm the robust CEI of about 2–3 nm formed on the surface of SF-NaMN cathode after 30 cycles. However, the CEI interface of NaMN is severely degraded and uneven after cycling, leading to significant surface degradation and crack formation (Supplementary Fig. 45). The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements (Supplementary Fig. 46 and Supplementary Note 10) suggest that SF-NaMN exhibit improved ion conductivity than NaMN after 50, 100, and 200 cycles, indicating that the CEI film of SF-NaMN is relatively stable and exhibits fewer side reactions with the electrolyte than that of NaMN.

a, b STEM-HAADF images of SF-NaMN stopped at 2.4 V after 30 cycles at 0.2 C, line profiles corresponding to the red line in Fig. 5b. c The GPA analysis of SF-NaMN from (a). d, e STEM-HAADF images of NaMN stopped at 2.4 V after 30 cycles at 0.2 C, line profiles corresponding to the blue line in Fig. 5e. f The GPA analysis of NaMN from (d). g–j TOF-SIMS profiles and 3D visualization of architecture evolution of SF-NaMN and NaMN stopped at 2.4 V after 30 cycles at 0.2 C. The normalization methodology applied to fig g–i is min-max normalization, feature scaling to the [0,1] range. k Scheme of TM migration and dissolution, and CEI formation on the SF-NaMN and NaMN cathode electrodes.

To intuitively monitor the influence of high-voltage electrochemical behavior of SF-NaMN and NaMN on gas evolution in batteries, in situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry were employed during the first charging process (Supplementary Fig. 47). Carbon dioxide (CO2) evolution was observed at 4.331 V vs. Na+/Na during the first charge of SF-NaMN, which is significantly later than that of NaMN (occurring at 4.171 V vs. Na+/Na). Noting that no obvious O2 release for SF-NaMN and NaMN, but a less considerable amount (CO2) release (308 μmol g−1) of SF-NaMN compared to that of NaMN (937 μmol g−1). According to the previous report, CO2 are generated from the reaction between the carbonate electrolyte with the highly active oxygen species on the surface or O2 evolved from the lattice oxygen of the cathode oxide46,47,48,49. Hence, the amount of CO2 is highly correlated with the release of O2. These results suggest that the degradation of P2-type layered oxide cathode and subsequent severe side reactions during high voltage region could attituded to the irreversible P–O phase transitions, resulting in unstable SEI (CEI) composition and gas evolution (Fig. 5k). SF-NaMN with pre-constructed O-type SF can effectively suppress these side reactions, addressing practical applications of positive electrode materials at the high voltage region.

In summary, we study a long-standing puzzle about the high voltage phase transition ever since the application of P-type transition layered oxides as cathode materials for SIBs: the abrupt lattice contraction underlies the fundamental origin for the irreversible phase transitions, while the TMO2 slabs gliding may not be necessarily correlated. A certain amount of O-type SF was pre-established in P2-type layered oxides with interlayer distances (O–Na–O) unchanged by modulating the cationic potentials of the compounds, which can prevent sudden c-drop under high SOC. Besides, such a structure can significantly suppress the surface degradation and form a stable CEI film, thus stabilizing the Na+ (de)intercalation reaction during the cycling process. The as-prepared SF-NaMN demonstrates single P2 phase with small c-axis change (1.45%) at a high voltage up to 4.5 V, and high temperature of 50 °C. The as assembled HC||SF-NaMN full cell delivered a high specific energy of 297 W h kg−1 without presodiation, and stably cycled over 600 cycles. A pouch-type cell and an all-solid-state full cell were also constructed based on SF-NaMN, delivers optimized cycling stability (340 cycles within 2–4.2 V) and a high specific energy of 437.6 W h kg−1, respectively. This work sheds lights on achieving high specific energy and high-voltage P2-type NaxTMO2 cathodes.

Methods

Materials preparation

We synthesized precursors of Na0.7Mn0.8Ni0.2O2 layered oxides with pre-constructed SF via a modulated co-precipitation method, leveraging the complex reactions between NH4+ and TM ions. In detail, 0.05 mol of nickel acetate (Aladdin, >99.0 %) and 0.1 mol of manganese acetate (Aladdin, >99.0%) were dissolved in deionized water in the required stoichiometric proportion and magnetically stirred at 25 °C for 1 h to yield a clear, homogeneous solution designated as A. 0.01 mol NH4HCO3 (Aladdin, >99.0%) was employed as precipitants, while 10 ml NH4OH (AR) was used to regulate the pH during precipitation, resulting in mixed (MnNi)xCO3 precursors for subsequent high-temperature calcination. During the precipitation, the NH4+ ions can readily complex with Ni2+ and form [Ni(NH3)6]2+, which competes with the precipitation of NiCO3. By precisely controlling the pH to 8.9, a dynamic equilibrium between precipitation and complexation was achieved, disrupting the ordered arrangement of Mn and Ni in (MnNi)xCO3 during repeated cycles of precipitation, dissolution, and reprecipitation of Ni ions. SF-NaMN is obtained after high-temperature calcination process. For comparison, a control sample with the same stoichiometric composition was synthesized using a conventional fast co-precipitation method with Na2CO3 as the precipitant. In the precipitation process, the reaction temperature was maintained at 12 °C. The precursor material was thoroughly washed several times by filtering with deionized water to remove residual sodium species, then dried in a vacuum oven at 120 °C overnight. Next, mixed the carbonate precursor of 0.01 mol with 0.004 mol Na2CO3 into planetary ball mills and milling with high energy in air with 1000 rpm at 25 °C for 6 h. Then, the powers were calcined at 500 °C for 10 h and then sintered at 900 °C for 12 h in Muffle furnace with heating rate of 5 °C/min and cooled down to room temperature. Li, Ti, Mg, Al, Cu, Fe, Zn-(SF-)/NaMN were prepared by mixing the precursor of SF-NaMN and NaMN with corresponding metal salts (Li2CO3, TiO2, MgO, Al2O3, CuO, Fe2O3, ZnO, Aladdin, >99.0%), subsequently calcined under the same thermal conditions. NASICON (Na3Zr2Si2PO12) solid-state electrolytes were purchased from HeFei Kejing company. Hard carbon (average particle size: 1.1 nm) are in-house prepared via bottom-up ZnO-assisted bulk etching strategy50. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, 99.5%), N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP, 99.5%), acetylene black (99.5%, average particle size: 300 nm), Al foil (20 μm, 99.5%) and Cu foil (18 μm, 99.5%) were all purchased from Alfa Aesar. Sodium discs (diameter: 16 mm, 0.5 mm thick) were punched from freshly rolled 99% Na metal (Alfa Aesar). The electrolyte, 1 mol NaPF6 in EC:PC with 5 % FEC (H2O ≤ 20 ppm), is supplied by KELUDE company.

Material characterizations

Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES, PERKINE 7300DV) was used to analyze the elemental composition of the samples. X-ray powder diffraction (PXRD) patterns were collected on a Bruker D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). In situ XRD studies, Al foil were prepared as X-ray windows with a Swagelok cell during charge and discharge process with scan rate of 5°/min, step size is 0.02°. The in situ synchrotron XRD characterizations were also performed using the 14B1 beamline (λ = 0.6887 Å) at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility Inc, China. Rietveld refinements were used to analysis the PXRD data with TOPAS software, which were collected at room temperature using a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (40 kV, 40 mA) at Shanghai Institute of Ceramics. The morphology of all samples are investigated by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, 30 kV for EDX capture). Atomic-scale microstructure was examined with a JEOL JEM-Grand ARM300F, Cs-corrected STEM running at 300 kV in HAADF mode. Synchrotron XANES spectra at the Mn and Ni K-edges were collected in transmission at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility on the IDEAS (Ge 220, IDEAS, double-crystal monochromator) and SXRMB (Si 111 double-crystal monochromator) beamlines, respectively. TOF-SIMS is conducted in negative ion mode with a region size of 80 micrometers × 80 micrometers, a depth of 200 nm, and signal intensities of all species in TOF-SIMS have been normalized. To prevent air exposure, the sample was moved directly from the glovebox into the ToF-SIMS vacuum chamber via a sealed transfer module. Depth profiling was then carried out by sputtering with a 2 kV, 100 nA Ar+ beam. XPS measurements were performed using an RBD-upgraded PHI-5000C ESCA system with Al Kα radiation and a testing duration of 1 h. XPS were calibrated by setting the binding energy for the hydrocarbon (C–C/C–H) in C 1 s spectra to 284.8 eV. Ex situ XPS and XAS analysis was preceded by a two-step EMC rinse of the dismantled electrodes, followed by drying inside the argon glovebox. While still under the same inert atmosphere, the specimens were loaded into a hermetic analysis chamber that was immediately sealed and transported to the spectrometer.

Electrochemical measurement

The electrode slurry was prepared by dissolving the active material, acetylene black, and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) at a mass ratio of 8:1:1 in N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP). It was then coated on one side of an aluminum foil with a loading density of 10–12 mg/cm2, followed by vacuum drying at 80 °C for 12 h. Metallic sodium was prepared by roll pressing followed by cutting into pieces (Ф12 mm). The 2032 coin cells were prepared in an argon-filled glove box. Using sodium tablets as counter electrode and the Glass fiber (GF/D, Whatman, Ф19 mm) was used as the separator in coin cell and PP@ceramic separator (JCK16 ceramic coated (double-face) PP-based separator (MTI); size: 16 μm × 80 mm (thickness × width)) in pouch-type full cell. For coin-type full-cell equipment, the hard carbon anode was blending with PVDF 10% and acetylene black 10%, then coating on copper foil with average loading density of 4–5 mg/cm2 and dried under vacuum at 80 °C for 12 h. The N/P ratio of coin-type full cell is 1.02–1.1, and for pouch cell is 1.15–1.2. The electrolyte amount are ~120 μl. Before pouch cell test, the pouch cell first be charged at a 0.1 C rate to 4.4 V. Subsequently, the pouch cell be unsealed for gas release, resealed properly, and then subjected to cycle testing, with a constant pressure of 69 kPa maintained throughout the entire cycling process. The CE is calculated as the ratio of discharge capacity divided by the charge capacity in the preceding charge cycle. EIS measurements were performed at 25 °C under open circuit potential, using a potentiostatic signal with an amplitude of 5 mV. The tests covered a frequency range of 0.1–106 Hz, with 12 data points collected per decade. The assembled cells were aged for 12 h to ensure that the system was fully wetted. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) results were collected at 0.2 mV s−1 within 2.4–4.5 V from electrochemical workstation (Autolab).

Galvanostatic cycling was carried out on a Land BT2000 tester (Wuhan, China). The Na⁺ diffusion coefficient (DNa+) was extracted from GITT data with the equation

where D denotes the diffusion coefficient of Na+ in the cathode, \({V}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) (cm3 mol–1) is the molar volume, \({{{\rm{m}}}}_{{{\rm{B}}}}\) and \({{{\rm{M}}}}_{{{\rm{B}}}}\) are the electrode mass and molar mass of cathode material. S (1.13 cm2) is the geometric area of the electrode. τ is the duration of the current pulse in the GITT step. \(\Delta {E}_{{{\rm{S}}}}\) is the steady state voltage change, and \({\Delta E}_{{{\rm{\tau }}}}\) is the total voltage change during the pulse. The charging process (galvanostatic pulse) lasted for 15 min, with a data acquisition interval of 10 s, corresponding to an acquisition frequency of 0.1 Hz (0.1 data points per second).

For the hybrid solid-state batteries, a Na disc was attached to one side of the NZSP pellet and heated to 200 °C in a Swagelok cell. A pressure of about 5000 Pa was applied to ensure intimate contact between molten Na and NZSP. To ensure the intimate contact between the cathode and solid electrolyte, 10 μL of 1 mol L–1 NaPF6 dissolved in EC: PC with 5% FEC was added, and the cathode loading was around 3 mg/cm2. The thickness of a NZSP pellet is 1 mm. The testing temperature is ~25 ± 2 °C. Supplementary Data 1 consists of an additional set of electrochemical result, which is provided to demonstrate the reproducibility of the electrochemical result of half-cell and full-cells.

Neutron powder diffraction measurement

The neutron powder diffraction experiment was carried out at the multi-physics instrument, a high-intensity time-of-flight diffractometer, at the China Neutron Spallation Source (CSNS)51. Approximately 1 g of the sample was loaded into a cylindrical sample holder, which was hermetically sealed with indium wires under an argon atmosphere. The sealed holder was then transferred to the scattering chamber for room-temperature testing, covering a neutron wavelength range of 0.1–4.5 Å. Diffraction patterns were collected using six detector banks (Bank 2–7) with 2θ range from 12.5 to 170.0°.

Computational methods

DFT calculations were performed with the Vienna ab-initio simulation package. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional was adopted as the base method. Given that GGA fails to accurately reproduce the localized electronic states of TMO2 materials, the GGA + U correction was introduced, with U values set to 5.05, 6.9 eV for Mn and Ni, respectively. Core electrons were described by the plane-wave projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudo-potentials. For the DFT calculations, a plane-wave basis set cutoff energy of 520 eV was adopted. A force convergence criterion of less than 0.01 eV Å−1 per unit cell was applied, while an electronic iteration convergence threshold of 1 × 10–5 eV was set for the self-consistent field calculations. A 2 × 2 × 3 supercell of Mn-Ni-ordered and disordered structure was conducted. All models have undergone structural optimization.

The energy barrier of phase transition caused by gliding is obtained by the equation:

where E stands for the lowest formation energy of NaxMn0.8Ni0.2O2 of different phase states at each composition. All relevant calculations were based on models with the same numbers and types of atoms.

Calculation of stacking faults probability

According to the Scherrer equation:

and the characteristics of broadening in hexagonal close-packed diffraction lines52, when h-k = 3n ± 1 and l = even, the diffraction line broadening is significant, whereas for l = odd, broadening is minimal. When only SF exist, the integral breadth β for an (hkl) reflection relates to stacking fault broadening \({\beta }_{f}\) as follows:

where\({\varphi }_{z}\) is the angle between the diffracting plane and the (001) plane, f is the stacking fault probability, and c is the lattice parameter along the c-axis.

When both crystallite size and stacking fault effects coexist, the Lorentzian approximation gives the total breadth as:

Solving for D (crystallite size) and f (SF probability) using Eqs. (6)–(8) is complex. Thus, a least squares method is proposed: substitute (3) and (7)-(8) into (6), multiply by \(\frac{\cos \theta }{\lambda }\)

and simplify to:

Define variables: Y= \(\beta \frac{\cos \theta }{\lambda }\), \({{\rm{a}}}=\frac{0.89}{D}\), \(X=\frac{1}{2c}\frac{\cos \theta }{\lambda }\cos {\varphi }_{z}\), F = 4f.

Williamson–Hall analysis

Variations in crystallite size and microstrain lead to the broadening of the diffraction peaks of the sample’s XRD pattern28,29,30, which changing differently as a function of the Bragg angle (θ). These variations can be calculated using the following equation:

where βstrain and βsize are lattice strain and size of crystallite, respectively. K is the shape factor (K = 0.9), and λ is the wavelength of the XRD. L is the crystallite size, and ε is the lattice microstrain.

The following equation are used to correct the instrumental broadening by the standard sample of single-crystal silicon:

βtotal is the measured full-width at half-maximum of each peak, βinstrument is the instrumental broadening, and βsample is the full-width at half-maximum of the sample. βsample is the sum of βstrain and βsize, followed by the equation:

Multiplying throughout by cos θ gives

\({\beta }_{{hkl}}\) is the line broadening (represented as FWHM) of the peak reflecting (hkl) plane.

Calculation of cationic potential

The cationic potential is introduced by Hu et al. to distinguish and design new materials1, the weighted average ionic potential of TMs can be defined as \(\bar{{\varPhi }_{{\mathrm{TM}}}}\),

where \({w}_{i}\) is the content of TM having oxidation state \({n}_{i}\) and radius \({R}_{i}\)

the weighted average ionic potential anionic ion can be defined as:

The weighted average ionic potential of Na is \(\bar{{\varPhi }_{{\mathrm{Na}}}}\), where x represents the Na content.

Based on the weight average ionic potentials of TM, Na and anionic ions, the cationic potential can be defined as:

Data availability

All relevant data supporting our study are provided in the manuscript and Supplementary Information file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhao, C. et al. Rational design of layered oxide materials for sodium-ion batteries. Science 370, 708 (2020).

House, R. A. et al. Superstructure control of first-cycle voltage hysteresis in oxygen-redox cathodes. Nature 577, 502–508 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Decoupling the air sensitivity of Na-layered oxides. Science 385, 744–752 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Toward the high-voltage stability of layered oxide cathodes for sodium-ion batteries: challenges, progress, and perspectives. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402008 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Routes to high-performance layered oxide cathodes for sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 4230–4301 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. Inhomogeneous coordination in high-entropy O3-type cathodes enables suppressed slab gliding and durable sodium storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202416290 (2025).

Shi, Q. et al. Niobium-doped layered cathode material for high-power and low-temperature sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 13, 3205 (2022).

Zhao, C. et al. Revealing high Na-content P2-type layered oxides as advanced sodium-ion cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5742–5750 (2020).

Lee, D. H., Xu, J. & Meng, Y. S. An advanced cathode for Na-ion batteries with high rate and excellent structural stability. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 3304–3312 (2013).

Jin, T. et al. Realizing complete solid-solution reaction in high sodium content P2-type cathode for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 14511–14516 (2020).

Lu, Z. & Dahn, J. R. In situ X-ray diffraction study of P2-Na2/3[Ni1/3Mn2/3]O2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 148, A1225 (2001).

Tournadre, F. et al. On the mechanism of the P2–Na0.70CoO2→O2–LiCoO2 exchange reaction—part I: proposition of a model to describe the P2–O2 transition. J. Solid State Chem. 177, 2790–2802 (2004).

Somerville, J. W. et al. Nature of the “Z”-phase in layered Na-ion battery cathodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 2223–2232 (2019).

Yang, L. et al. Lithium-doping stabilized high-performance P2–Na0.66Li0.18Fe0.12Mn0.7O2 cathode for sodium ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6680–6689 (2019).

Wang, P.-F. et al. Na+/vacancy disordering promises high-rate Na-ion batteries. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar6018 (2018).

Wang, P.-F. et al. Suppressing the P2–O2 phase transition of Na0.67Mn0.67Ni0.33O2 by magnesium substitution for improved sodium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 7445–7449 (2016).

Yan, Z. et al. A hydrostable cathode material based on the layered P2@P3 composite that shows redox behavior for copper in high-rate and long-cycling sodium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 1412–1416 (2019).

Cai, X. et al. Constraining interlayer slipping in P2-type layered oxides with oxygen redox by constructing strong covalent bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 5860–5870 (2025).

Liu, X. et al. Stabilizing interlayer repulsion in layered sodium-ion oxide cathodes via hierarchical layer modification. Adv. Mater. 36, 2407519 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Achieving a high-performance sodium-ion pouch cell by regulating intergrowth structures in a layered oxide cathode with anionic redox. Nat. Energy 9, 184–196 (2024).

Tang, Y. et al. Sustainable layered cathode with suppressed phase transition for long-life sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Sustain. 7, 348–359 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Unexpected elevated working voltage by Na+/vacancy ordering and stabilized sodium-ion storage by transition-metal honeycomb ordering. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202409152 (2024).

Zhu, X. et al. Mitigating mechanical stress by the hierarchical crystalline domain for high-energy P2/O3 biphasic cathode materials. ACS Nano 18, 32003–32015 (2024).

Ding, F. et al. Tailoring planar strain for robust structural stability in high-entropy layered sodium oxide cathode materials. Nat. Energy 9, 1529–1539 (2024).

Warren, B. E. X-ray studies of deformed metals. Prog. Metal Phys. 8, 147–202 (1959).

Révész, Á, Ungár, T., Borbély, A. & Lendvai, J. Dislocations and grain size in ball-milled iron powder. Nanostruct. Mater. 7, 779–788 (1996).

Holzwarth, U. & Gibson, N. The Scherrer equation versus the ‘Debye-Scherrer equation’. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 534–534 (2011).

Dutta, S. et al. Role of defects in tailoring structural, electrical and optical properties of ZnO. Prog. Mater. Sci. 54, 89–136 (2009).

Park, N.-Y., Cho, G., Kim, S.-B. & Sun, Y.-K. Multifunctional doping strategy to develop high-performance Ni-rich cathode material. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2204291 (2023).

Mote, V. D., Purushotham, Y. & Dole, B. N. Williamson-Hall analysis in estimation of lattice strain in nanometer-sized ZnO particles. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 6, 6 (2012).

Radin, M. D. & Van der Ven, A. Stability of prismatic and octahedral coordination in layered oxides and sulfides intercalated with alkali and alkaline-earth metals. Chem. Mater. 28, 7898–7904 (2016).

Rong, X. et al. Structure-induced reversible anionic redox activity in Na layered oxide cathode. Joule 2, 125–140 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Hierarchical engineering of porous P2-Na2/3Ni1/3Mn2/3O2 nanofibers assembled by nanoparticles enables superior sodium-ion storage cathodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1907837 (2020).

Zheng, X. et al. New insights into understanding the exceptional electrochemical performance of P2-type manganese-based layered oxide cathode for sodium ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 15, 257–265 (2018).

Niu, Y.-B. et al. High-efficiency cathode sodium compensation for sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001419 (2020).

Fang, K. et al. Injecting excess Na into a P2-type layered oxide cathode to achieve presodiation in a Na-ion full cell. Nano Lett. 23, 6681–6688 (2023).

Zhang, B. et al. Insertion compounds and composites made by ball milling for advanced sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 7, 10308 (2016).

Chen, Y. et al. Breaking solvation dominance of ethylene carbonate via molecular charge engineering enables lower temperature battery. Nat. Commun. 14, 8326 (2023).

Shafiei Sabet, P. & &Sauer, D. U. Separation of predominant processes in electrochemical impedance spectra of lithium-ion batteries with nickel-manganese-cobalt cathodes. J. Power Sources 425, 121–129 (2019).

Plank, C. et al. A review on the distribution of relaxation times analysis: a powerful tool for process identification of electrochemical systems. J. Power Sources 594, 233845 (2024).

Raccichini, R., Amores, M. & Hinds, G. Critical review of the use of reference electrodes in Li-ion batteries: a diagnostic perspective. Batteries 5, 12 (2019).

Lu, Y., Zhao, C.-Z., Huang, J.-Q. & Zhang, Q. The timescale identification decoupling complicated kinetic processes in lithium batteries. Joule 6, 1172–1198 (2022).

Meddings, N. et al. Application of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to commercial Li-ion cells: a review. J. Power Sources 480, 228742 (2020).

Wang, K., Yan, P. & Sui, M. Phase transition induced cracking plaguing layered cathode for sodium-ion battery. Nano Energy 54, 148–155 (2018).

He, J. et al. Tuning the solvation structure with salts for stable sodium-metal batteries. Nat. Energy 9, 446–456 (2024).

Rinkel, B. L. D., Hall, D. S., Temprano, I. & Grey, C. P. Electrolyte oxidation pathways in lithium-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15058–15074 (2020).

Luo, K. et al. Charge-compensation in 3d-transition-metal-oxide intercalation cathodes through the generation of localized electron holes on oxygen. Nat. Chem. 8, 684–691 (2016).

Jung, R., Metzger, M., Maglia, F., Stinner, C. & Gasteiger, H. A. Oxygen release and its effect on the cycling stability of LiNixMnyCozO2 (NMC) cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, A1361 (2017).

Marie, J.-J. et al. Trapped O2 and the origin of voltage fade in layered Li-rich cathodes. Nat. Mater. 23, 818–825 (2024).

Yin, X. et al. Enabling fast Na+ transfer kinetics in the whole-voltage-region of hard-carbon anodes for ultrahigh-rate sodium storage. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109282 (2022).

Xu, J. et al. Multi-physics instrument: total scattering neutron time-of-flight diffractometer at China spallation neutron source. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 1013, 165642 (2021).

Cheng, G.-F., Yang, C.-Z. & Huang, Y.-H. Characterization and research of hexagonal closed packing structured ZnO nano-powders by X-ray diffraction method. J. Inorg. Mater. 23, 199–202 (2008).

Peng, B. et al. Unusual site-selective doping in layered cathode strengthens electrostatic cohesion of alkali-metal layer for practicable sodium-ion full Cell. Adv. Mater. 34, 2103210 (2022).

Zhou, P. et al. High-entropy P2/O3 biphasic cathode materials for wide-temperature rechargeable sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 57, 618–627 (2023).

Cheng, Z. et al. Mitigating the large-volume phase transition of P2-type cathodes by synergetic effect of multiple ions for improved sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2103461 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Boosting the reversibility and kinetics of anionic redox chemistry in sodium-ion oxide cathodes via reductive coupling mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 22708–22719 (2023).

Shen, Q. et al. Transition-metal vacancy manufacturing and sodium-site doping enable a high-performance layered oxide cathode through cationic and anionic redox chemistry. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2106923 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Multi-level modifications enabling chemomechanically stable Ni-rich O3-layered cathode toward wide-temperature-tolerance quasi-solid-state Na-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203701 (2023).

Liang, X., Yu, T.-Y., Ryu, H.-H. & Sun, Y.-K. Hierarchical O3/P2 heterostructured cathode materials for advanced sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 47, 515–525 (2022).

Peng, B. et al. A customized strategy realizes stable cycle of large-capacity and high-voltage layered cathode for sodium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202411618 (2024).

Jin, J. et al. Intrinsic distortion against Jahn-Teller distortion: a new paradigm for high-stability Na-ion layered Mn-rich oxide cathodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202423728 (2025).

Ding, F. et al. Tailoring electronic structure to achieve maximum utilization of transition metal redox for high-entropy Na layered oxide cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13592–13602 (2023).

Yu, L. et al. Interlocking biphasic chemistry for high-voltage P2/O3 sodium layered oxide cathode. Energy Storage Mater. 50, 730–739 (2022).

Wang, Q. et al. Fast-charge high-voltage layered cathodes for sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Sustain. 7, 338–347 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22479091, 22179077), and East China Normal University Multifunctional Platform for Innovation (004). We greatly appreciate the neutron beamtime granted from the China Spallation Neutron Source (CSNS) and the technical assistance from Huaican Chen. We greatly appreciate for the beamline time given by BL14B1 for testing X-ray diffraction, and BL14W1 station for testing X-ray absorption spectroscopy from the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). This work is supported by the Shanghai Technical Service Center of Science and Engineering Computing, Shanghai University. The three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric data of this study, was performed using VESTA software (Version 3). We acknowledge the development team of this software, and its use is supported by the following reference: K. Momma and F. Izumi, “VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data,” J. Appl. Crystallogr., 44, 1272-1276 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-F.Z. and J.L. conceived and planned the project concept. J.L. and Y.-F.Z. supervised the project. Q.-H.S. performed experiments and initial data analysis. F.-H.N., X.Y., and Z.-P.Y. carried out the theoretical calculation analysis. F.-J.X., R.-J.Q., and J.-S.W. carried out STEM measurements. G.-F.C. carried out XRD test and calculated stacking faults probability. Y.Q. and H.-Y.L. carried out electrochemical tests. H.-F.Z. analyzed XRD and STEM results. T.Z. performed the DEMS test. S.-G.L. and T.L. carried out pouch cell fabrication. Y.-C.L. conducted PDF measurements. H.-C.C. carried out the NPD test. W.W. performed synchrotron XRD tests. Q.-H.S. wrote the original draft. J.-J.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors discussed the results, co-wrote and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bryan Wygant, Zeyu Hui and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Q., Ning, F., Yu, X. et al. Decoupling slab gliding and lattice contraction in Na layered oxides to enable high-voltage Na-ion batteries. Nat Commun 17, 1516 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68238-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68238-7