Abstract

Avena sterilis, the ancestral species of cultivated oats, is a valuable genetic resource for oat improvement. Here we generated a near-complete 10.99 Gb A. sterilis genome and a high-quality 10.89 Gb cultivated oat genome. Genome evolution analysis revealed the centromeres dynamic and structural variations landscape associated with domestication between wild and cultivated oats. Population genetic analysis of 117 wild and cultivated oat accessions worldwide detected many candidate genes associated with important agronomic traits for oat domestication and improvement. Remarkably, a large fragment duplication from chromosomes 4A to 4D harbouring many agronomically important genes was detected during oat domestication and was fixed in almost all cultivated oats from around the world. The genes in the duplication region from 4A showed significantly higher expression levels and lower methylation levels than the orthologous genes located on 4D in A. sterilis. This study provides valuable resources for evolutionary and functional genomics and genetic improvement of oat.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All PacBio sequence data, ONT ultra-long sequence data, transcriptome data, resequencing data and Hi-C data in this study have been deposited in the Chinese National Genomics Data Center (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/) under the BioProject accession number PRJCA023350. The final genome assemblies were also submitted to the Chinese National Genomics Data Center under the accession number GWHERDU00000000. Source data are presented within this article in supplementary table.

References

Ahmad, M. et al. Genetic analysis for fodder yield and other important traits in oats (Avena sativa L.). Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 74, 112–114 (2014).

Soreng, R. et al. A worldwide phylogenetic classification of the Poaceae (Gramineae) II: an update and a comparison of two 2015 classifications. J. Syst. Evol. 55, 259–290 (2017).

Liu, Q. Unraveling the evolutionary dynamics of ancient and recent polyploidization events in Avena (Poaceae). Sci. Rep. 7, 41944 (2017).

Tomaszewska, P., Schwarzacher, T. & Heslop-Harrison, J. S. P. Oat chromosome and genome evolution defined by widespread terminal intergenomic translocations in polyploids. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1026364 (2022).

Zhou, X., Jellen, E. N. & Murphy, J. P. Progenitor germplasm of domisticated hexaploid oat. Crop Sci. 39, 1208–1214 (1999).

Peng, Y. et al. Reference genome assemblies reveal the origin and evolution of allohexaploid oat. Nat. Genet. 54, 1248–1258 (2022).

Yan, H. et al. High-density marker profiling confirms ancestral genomes of Avena species and identifies d-genome chromosomes of hexaploid oat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 129, 2133–2149 (2016).

Linares, C., Ferrer, E. & Fominaya, A. Discrimination of the closely related A and D genomes of the hexaploid oat Avena sativa L. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12450–12455 (1998).

Xuehui, H. & Han, B. Natural variations and genome-wide association studies in crop plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 531–551 (2013).

Shi, J., Tian, Z., Lai, J. & Huang, X. Plant pan-genomics and its applications. Mol. Plant 16, 168–186 (2023).

Song, B. et al. Plant genome resequencing and population genomics: current status and future prospects. Mol. Plant 16, 1252–1268 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. The complete and fully-phased diploid genome of a male Han Chinese. Cell Res. 33, 745–761 (2023).

Naish, M. et al. The genetic and epigenetic landscape of the Arabidopsis centromeres. Science 374, eabi7489 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. A complete telomere-to-telomere assembly of the maize genome. Nat. Genet. 55, 1221–1231 (2023).

Kong, W., Wang, Y., Zhang, S., Yu, J. & Zhang, X. Recent advances in assembly of plant complex genomes. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 21, 427–439 (2023).

Shang, L. et al. A complete assembly of the rice Nipponbare reference genome. Mol. Plant 16, 1232–1236 (2023).

Song, J.-M. et al. Two gap-free reference genomes and a global view of the centromere architecture in rice. Mol. Plant 14, 1757–1767 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. The telomere-to-telomere genome of Fragaria vesca reveals the genomic evolution of Fragaria and the origin of cultivated octoploid strawberry. Hortic. Res. 10, uhad027 (2023).

Kamal, N. et al. The mosaic oat genome gives insights into a uniquely healthy cereal crop. Nature 606, 113–119 (2022).

Tao, Y. et al. Extensive variation within the pan-genome of cultivated and wild sorghum. Nat. Plants 7, 766–773 (2021).

Loskutov, I., Blinova, E., Gavrilova, O. & Gagkaeva, T. The valuable characteristics and resistance to Fusarium disease of oat genotypes. Russ. J. Genet. 7, 290–298 (2017).

Kebede, G., Worku, W., Feyissa, F. & Jifar, H. Agro-morphological traits-based genetic diversity assessment on oat (Avena sativa L.) genotypes in the central highlands of Ethiopia. All Life 16, 2236313 (2023).

Li, N. et al. Super-pangenome analyses highlight genomic diversity and structural variation across wild and cultivated tomato species. Nat. Genet. 55, 852–860 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. A route to de novo domestication of wild allotetraploid rice. Cell 184, 1156–1170.e14 (2021).

Jia, K.-H. et al. SubPhaser: a robust allopolyploid subgenome phasing method based on subgenome-specific k-mers. New Phytol. 235, 801–809 (2022).

Ou, S., Chen, J. & Jiang, N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e126 (2018).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245 (2020).

Li, K., Xu, P., Wang, J., Yi, X. & Jiao, Y. Identification of errors in draft genome assemblies at single-nucleotide resolution for quality assessment and improvement. Nat. Commun. 14, 6556 (2023).

Zheng, D.-S. & Zhang, Z.-W. Discussion on the origin and taxonomy of naked oat (Avena nuda L.). J. Plant Genet. Resour. 12, 667–670 (2011).

Jellen, E. N. et al. A uniform gene and chromosome nomenclature system for oat (Avena spp.). Crop Pasture Sci. 75, CP23247 (2024).

Mascher, M. et al. A chromosome conformation capture ordered sequence of the barley genome. Nature 544, 427–433 (2017).

Wang, K. Genome resources for the elite bread wheat cultivar Aikang 58 and mining of elite homeologous haplotypes for accelerating wheat improvement. Mol. Plant 16, 1893–1910 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Pan-centromere reveals widespread centromere repositioning of soybean genomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2310177120 (2023).

Zhou, J. et al. Centromeres: from chromosome biology to biotechnology applications and synthetic genomes in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 2051–2063 (2022).

Liu, Q. et al. Non-B-form DNA tends to form in centromeric regions and has undergone changes in polyploid oat subgenomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2211683120 (2023).

Ma, H. et al. Centromere plasticity with evolutionary conservation and divergence uncovered by wheat 10+ genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 40, msad176 (2023).

Lv, Y. et al. A centromere map based on super pan-genome highlights the structure and function of rice centromeres. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 66, 196–207 (2023).

Miller, J., Dong, F. G., Jackson, S., Song, J. & Jiang, J. Retrotransposon-related DNA sequences in the centromeres of grass chromosomes. Genetics 150, 1615–1623 (1999).

Chang, X. et al. High-quality Gossypium hirsutum and Gossypium barbadense genome assemblies reveal the centromeric landscape and evolution. Plant Commun. 5, 100722 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Structure and dynamics of retrotransposons at wheat centromeres and pericentromeres. Chromosoma 117, 445–456 (2008).

Maughan, J. et al. Genomic insights from the first chromosome-scale assemblies of oat (Avena spp.) diploid species. BMC Biol. 17, 92 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Pangenome analysis reveals genomic variations associated with domestication traits in broomcorn millet. Nat. Genet. 55, 2243–2254 (2023).

Li, K. et al. Interactions between SQUAMOSA and SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE MADS-box proteins regulate meristem transitions during wheat spike development. Plant Cell 33, 3621–3644 (2021).

Xiaomin, J. et al. Cloning and functional identification of phosphoethanolamine methyltransferase in soybean (Glycine max). Front. Plant Sci. 12, 612158 (2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Population genomic analysis reveals domestication of cultivated rye from weedy rye. Mol. Plant 15, 552–561 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Haplotype-resolved genome assembly provides insights into evolutionary history of the tea plant Camellia sinensis. Nat. Genet. 53, 1250–1259 (2021).

Ji, H. et al. Inactivation of the CTD phosphatase-like gene OsCPL1 enhances the development of the abscission layer and seed shattering in rice. Plant J. 61, 96–106 (2009).

Luo, J. et al. An-1 encodes a basic helix–loop–helix protein that regulates awn development, grain size, and grain number in rice. Plant Cell 25, 3360–3376 (2013).

Hong, J.-P. et al. Suppression of RICE TELOMERE BINDING PROTEIN1 results in severe and gradual developmental defects accompanied by genome instability in rice. Plant Cell 19, 1770–1781 (2007).

Lv, R. et al. Chromosome translocation affects multiple phenotypes, causes genome-wide dysregulation of gene expression, and remodels metabolome in hexaploid wheat. Plant J. 115, 1564–1582 (2023).

Puchta, H. & Houben, A. Plant chromosome engineering - past, present and future. New Phytol. 241, 541–552 (2023).

Liang, Z. et al. Epigenetic modifications of mRNA and DNA in plants. Mol. Plant 13, 14–30 (2020).

Guo, L. et al. Modified expression of TaCYP78A5 enhances grain weight with yield potential by accumulating auxin in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 168–182 (2022).

Logsdon, G. A. et al. The variation and evolution of complete human centromeres. Nature 629, 136–145 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. A near-complete genome assembly of Brassica rapa provides new insights into the evolution of centromeres. Plant Biotechnol. J. 21, 1022–1032 (2023).

Su, H. et al. Centromere satellite repeats have undergone rapid changes in polyploid wheat subgenomes. Plant Cell 31, 2035–2051 (2019).

Ines, O. & White, C. Centromere associations in meiotic chromosome pairing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 49, 95–114 (2015).

Qin, P. et al. Pan-genome analysis of 33 genetically diverse rice accessions reveals hidden genomic variations. Cell 184, 3542–3558.e16 (2021).

Jayakodi, M. et al. The barley pan-genome reveals the hidden legacy of mutation breeding. Nature 588, 284–289 (2020).

Crespo-Herrera, L., Gustavsson, L. & Åhman, I. A systematic review of rye (Secale cereale L.) as a source of resistance to pathogens and pests in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Hereditas 154, 14 (2017).

Li, G. et al. A high-quality genome assembly highlights rye genomic characteristics and agronomically important genes. Nat. Genet. 53, 574–584 (2021).

Kim, W., Johnson, J. W., Baenziger, P., Lukaszewski, A. J. & Gaines, C. S. Agronomic effect of wheat-rye translocation carrying rye chromatin (1R) from different sources. Crop Sci. 44, 1254–1258 (2004).

Chen, Y. et al. Innovative computational tools provide new insights into the polyploid wheat genome. aBIOTECH 5, 52–70 (2024).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Durand, N. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Jain, C. et al. Weighted minimizer sampling improves long read mapping. Bioinformatics 36, i111–i118 (2020).

Vaser, R., Sovic, I., Nagarajan, N. & Sikic, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27, 737–746 (2017).

Servant, N. et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol. 16, 259 (2015).

Akdemir, K. & Chin, L. HiCPlotter integrates genomic data with interaction matrices. Genome Biol. 16, 198 (2015).

Li, H. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. New strategies to improve minimap2 alignment accuracy. Bioinformatics 37, 4572–4574 (2021).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M., Seppey, M., Simão, F. & Zdobnov, E. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4647–4654 (2021).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422 (2017).

Zhang, H. et al. The haplotype-resolved genome assembly of autotetraploid rhubarb Rheum officinale provides insights into its genome evolution and massive accumulation of anthraquinones. Plant Commun. 5, 100677 (2024).

He, Q. et al. The near-complete genome assembly of Reynoutria multiflora reveals the genetic basis of stilbene and anthraquinone biosynthesis. J. Syst. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.13068 (2024).

Hubley, R. & Smit, A. RepeatModeler Open-1.0 (Institute for Systems Biology, 2010); http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler/

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268 (2007).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 18 (2008).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580 (1999).

Stanke, M. & Waack, S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics 19, ii215–ii225 (2003).

Gremme, G., Brendel, V., Sparks, M. E. & Kurtz, S. Engineering a software tool for gene structure prediction in higher organisms. Inf. Softw. Technol. 47, 965–978 (2005).

Haas, B. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–1512 (2013).

Haas, B. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666 (2003).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295 (2015).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 9, R7 (2008).

Aramaki, T. et al. KofamKOALA: KEGG ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 36, 2251–2252 (2020).

Li, H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 27, 2987–2993 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

Ramirez, F. et al. deeptools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W160–W165 (2016).

Said, M. et al. The Agropyron cristatum karyotype, chromosome structure and cross-genome homoeology as revealed by fluorescence in situ hybridization with tandem repeats and wheat single-gene probes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 131, 2213–2227 (2018).

Xi, W. et al. New ND-FISH-positive oligo probes for identifying Thinopyrum chromosomes in wheat backgrounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2031 (2019).

Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for bisulfite-seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571–1572 (2011).

Marcais, G. et al. MUMmer4: a fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14, e1005944 (2018).

Goel, M., Sun, H., Jiao, W.-B. & Schneeberger, K. SyRI: finding genomic rearrangements and local sequence differences from whole-genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 20, 277 (2019).

Emms, D. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Han, M. V., Thomas, G. W. C., Lugo-Martinez, J. & Hahn, M. W. Estimating gene gain and loss rates in the presence of error in genome assembly and annotation using CAFE 3. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1987–1997 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49 (2012).

Wang, D., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhu, J. & Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 8, 77–80 (2010).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff. Fly 6, 80–92 (2012).

Minh, B. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Alexander, D. & Lange, K. Enhancements to the ADMIXTURE algorithm for individual ancestry estimation. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 246 (2011).

Purcell, S. et al. Plink: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFTools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

Zhang, C., Dong, S.-S., Xu, J.-Y., He, W.-M. & Yang, T.-L. PopLDdecay: a fast and effective tool for linkage disequilibrium decay analysis based on variant call format files. Bioinformatics 35, 1786–1788 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Y. Fan at the School of Food and Biological Engineering, Chengdu University, for sharing with us wild oat accessions. We also thank F. Han, Y. Liu and Q. Liu at the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for kindly providing CENH3 antibody and helping to perform the ChIP experiments. This work was supported by the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by Chinese Association for Science and Technology (grant number YESS20210080 to H.D.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 32100500 to H.D.), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (grant numbers C2021201048 and C2023201074 to H.D.), the Interdisciplinary Research Program of Natural Science of Hebei University (grant number 513201422004 to H.D.) and The Excellent Youth Research Innovation Team of Hebei University (QNTD202401 to Q.H.) and was funded by Science and Technology Project of Hebei Education Department (QN2024271 to Q.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.D. conceived and supervised the project; Q.H. and H.D. wrote the paper; Y.M. sequenced and processed the raw data; Q.H., Yu Wang and Y.M. assembled and annotated the genome; Q.H. and Yu Wang performed the centromere analysis. Q.H., Y.M., W.L. and Y.X. performed the phylogenetic and genome evolution analysis; Q.H. and H.Z. conducted the transcriptome analysis; Q.H., Y.M. and Yaru Wang conducted pan-genome analyses. Q.H., J.L., H.D., W.L., H.L. and Yu Wang performed population analyses. T.L., N.L., S.W. and Q.S. conceived of and designed the experiments. N.L. and Y.Y. conducted the FISH validation of chromosomal segment duplication. H.W. revised the manuscript. Z.G. offered invaluable guidance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Jeff Maughan, Klaus Mayer and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Genome assembly for Avena sterilis.

a, Hi-C chromatin interaction map of A. sterilis assembly. b, Principal component analysis (PCA) of differential k-mers from the 21 chromosomes in A. sterilis. Points indicate chromosomes. c, Sequencing coverage and assembly validation of the A. sterilis genome. Uniform whole-genome coverage of mapped HiFi, ONT, Hi-C, and Illumina reads is shown. Black triangle represents the position of gap in the genome. d, BUSCO completeness assessment for genomics data of A. sterilis, Marvellous and Sanfensan. e, LTR Assembly Index (LAI) score for each chromosome of A. sterilis (Aste), Marvellous and Sanfensan. A, C and D subgenome was colored in blue, green and purple, respectively. f, The quality value (QV) score of published T2T genomes. The number on histograms represent genome size.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Identification of A. sterilis centromere.

The centromere region was determined based on Chip-seq peak, gene density, LTR density, and k-mer frequency with 10 Mb window.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Analysis of centromere composition.

a, Comparison of the proportion of LTR‐RT family for the centromeres and non‐centromeres region in OT3098 and Sang genomes. b, Comparison of the insertion time of LTR‐RT family for the centromeres and non‐centromeres region in OT3098 and Sang genomes. Significance levels are computed from two-sided Wilcoxon tests. c, Proportion of LTR-RT family in centromere regions of different subgenome in OT3098 and Sang. d, Proportion of LTR-RT family in centromere regions of different subgenome in Avena eriantha (CC) and Avena insularis (CCDD) oats. e, Copy of Cen46 and Cen55 repeats units in C subgenome of A. eriantha and A. insularis oats.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Gene family and subgenome differentiation.

a, Venn diagram showing the numbers of common and unique gene families identified in the subgenomes of three oat genomes. Aste: A. sterilis. b-c, KEGG enrichment analysis of specific genes in three subgenomes and the expanded genes in the A. sterilis genome. d, Venn diagram showing the numbers of common and unique gene families identified in Pan-A, Pan-C and Pan-D of hexaploid oat. e, GO term enrichment analysis for specific genes in Pan-A, Pan-C, and Pan-D of hexaploid oat. f, Comparison of Ks values between subgenomes in A. sterilis genome. Significance levels are computed from two-sided Wilcoxon tests. g, Gene expression pattern in the A, C, and D subgenome across three tissues in A. sterilis genome. h, Gene expression pattern across different subgenomes in three tissues, using a window of 10 collinear genes in A. sterilis genome. The horizontal axis represents the number of windows based on the A subgenome as a reference.

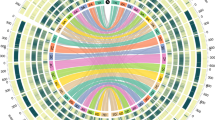

Extended Data Fig. 5 Identification and verification of structural variation.

a, Synteny and rearrangement plot for six oat species, including three hexaploid cultivated oat, A. sterilis, A. longiglumis (AA) and A. insularis (CCDD). b, Verification of SVs. The short-read data were used to validate the borders of deletions randomly selected between Marvellous and A. sterilis genome. c, Schematic diagrams of the distribution of inversion between Marvellous and A. sterilis geome (x-axis: A. sterilis, y-axis: Marvellous). Red box represented the inverted segments relative to A. sterilis. d, Illustration of inversion identified between Marvellous and A. sterilis genome by Hi-C contact map. Chromatin interaction heatmap revealed inversion signals appearing after manual flipping. These maps supported the inversions in chromosome 1C, 2C, 3A, 3C and 4C. e, The validation of inversion borders by PCR amplification. This experiment was repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Analysis of specific LTR-RTs families.

a, Cluster analysis of transposable element (TE) families in three oat genomes. The pie chart represents the proportion of PAVs overlapped with repeat and non-repeat regions. b, The number and insertion time of specific LTR-RTs families in three oat genomes. c, GO term enrichment analysis of genes affected by specific TEs in the A. sterilis genome. d, Gene structures and expression of homologous SAM-MT genes (AVESA.00702a.r1.1Ag0146002, AVESA.00401a.r1.1Ag0188833, AVESA.00022a.r1.1A0151681, and AVESA.00010b.r1.1Ag1357780) in four oat genomes, comprising A. sterilis, Marvellous, Sanfensan, and Sang.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Genetic diversity of wild and cultivated oats.

a, Principal component analysis (PCA) for 117 oat accessions. b, Nucleotide diversity (π) and population divergence (FST) of G1, G2 and G3 groups. The value in each circle represents an estimation of nucleotide diversity for each group, and values on each line indicate pairwise population divergence. c, The linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay analysis for G1, G2 and G3 groups. d-e, GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of genes in selective sweeps region between wild and cultivated group. f, Signals of artificial selection in the OsCLP1 gene related to shattering. Scale bar, 10 cm. Black dashed line is the threshold of the top 5% π ratio and Fst between wild and cultivated oat. g, Gene structure, haplotype, selective signature and expression of OsCLP1 gene between wild and cultivated oat. qRT-PCR was repeated independently at least three times with similar results. Significance levels are computed from two-sided Wilcoxon tests. h, Signals of artificial selection in the An1 gene related to awn length. Scale bar, 1 cm. Black dashed line is the threshold of the top 5% π ratio and Fst between wild and cultivated oat. i, Gene structure, haplotype, selective signature and expression for An1 gene between wild and cultivated oat. qRT-PCR was repeated independently at least three times with similar results. Significance levels are computed from two-sided Wilcoxon tests.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Identification of a candidate locus associated with oat improvement.

a, Manhattan plots showing selective sweep regions based on FST values (G2 vs G3). Candidate locus was marker with gray. b, Different genotypes in candidate locus are represented by different colors. c, Pairwise linkage disequilibrium heatmap (top) of the candidate locus. This locus exhibits high degree of synteny with a previously reported NOH1 locus on rice chromosome 1. d, Top is haplotype frequency of AsTRP1 (AVESA.00022a.r1.4Dg0170063) in Marvellous between G2 and G3 group. Down is reads depth distributions of an SV region in AsTRP1 gene.

Extended Data Fig. 9 The large fragment duplication from 4A to 4D.

a, The Illumina read coverage of the chromosome 4D. Ains: A. insularis. b, The gene collinear between the start of chromosome 4A and 4D. c, Hi-C contact map showing a translocation event occurred from 4A to 4D and this fragment exist two copies. d, FISH confirms the duplication segment in cultivated oat, as observed in cells at the metaphase of mitosis. This experiment was repeated independently at least three times with similar results. e, Differential transcript expression patterns of genes located on start (1–28 Mb) of chromosome 4A and 4D in A. sterilis. f, Expression of genes in chromosome 4A and 4D in A. sterilis.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–7 and Tables 1–17.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Q., Li, W., Miao, Y. et al. The near-complete genome assembly of hexaploid wild oat reveals its genome evolution and divergence with cultivated oats. Nat. Plants 10, 2062–2078 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01866-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01866-x

This article is cited by

-

Integrated transcriptomic, metabolomic and lipidomic analyses uncover the crucial roles of lipid metabolism pathways in oat (Avena sativa) responses to heat stress

BMC Genomics (2025)

-

Reference genome and population genomic analyses reveal insight into herbicide tolerance in Avena fatua L.

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Super-pangenome analyses across 35 accessions of 23 Avena species highlight their complex evolutionary history and extensive genomic diversity

Nature Genetics (2025)