Abstract

As Earth’s magnetic field weakens, space radiation begins to pose a significant threat to the health of not only space travelers, but the world’s population. Space radiation, comprising high-energy and high-charge ions, creates distinct clusters of DNA damage and dense macromolecular damage that result in the accumulation of senescent cells (SnCs) known to play a critical role in promoting multimorbidity. Here, we demonstrate that human fibroblasts exposed to different forms of space radiation acquire senescence-associated phenotypes including morphological alterations and the accumulation of SA-ß-gal+ cells to a greater extent than what is observed following γ-irradiation. Bulk and single cell RNA (scRNAseq) sequencing analysis revealed that space irradiated human fibroblasts up-regulated senescent-like phenotypes to a greater extent compared to γ-irradiation and enriched pathways associated with chronic activation and adaptation of the integrated stress response and NADPH-coupled redox metabolism. Healthy cells treated with conditioned media from irradiated SnCs manifested pro-inflammatory transcriptional profiles dependent on both radiation and cell type. Finally, treatment with known senotherapeutics demonstrated radiation-specific effects in primary dermal fibroblasts. Our data demonstrate that space radiation differentially induces senescent phenotypes in human cells compared to γ-irradiation, which may play a key role in the pathogenic effects of space travel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During space travel, astronauts are exposed to galactic cosmic rays composed of high-energy protons (or hydrogen ions) and high-energy and high-Z (HZE) particles that are essentially nuclei of elements heavier than hydrogen1,2. HZE particles have higher-linear energy transfer (LET) and thus increased damaging potential than the low-LET radiation such as gamma (γ) and X-ray radiation typically encountered on earth3,4. Studies comparing the differential induction of DNA damage in normal fibroblasts induced by γ or HZE-particle radiation showed that unlike γ- radiation, which randomly distributes double stranded breaks throughout the nucleus, HZE ions densely deposit their energy along their trajectory and create non-random clusters of double and single stranded breaks located within a distance of 3.4 nm of each other5,6. The DNA damage induced by heavy-ion irradiation is difficult to repair, resulting in complex chromosomal aberrations including dicentrics, translocations, rearrangements, and large deletions that have been found to be over 1000 base pairs in length, causing genomic instability resulting in cell death and senescence-like growth arrest4. HZE-ion irradiation also promotes a state of chronic oxidative stress in comparison to γ-irradiation4,7,8. Furthermore, current protective shielding fails to prevent this complex, irreparable DNA damage phenotype and has even been shown to exacerbate the effects of HZE ion radiation beyond DNA damage including induction of reactive oxygen species and inflammation5,7,9,10.

DNA damage and the persistent activation of the DNA damage response is known to be a key driver of cellular senescence11,12. Cellular senescence is a dynamic state of cell cycle arrest triggered by the persistent accumulation of molecular damage promoted by stressors including ionizing radiation. Senescent cells (SnCs) create a pathological senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) comprised of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and other macromolecules that alter the cells’ extra cellular matrix, promote a state of low-grade inflammation, and influence neighboring cells13,14,15,16. Thus, SnCs have been shown to play a critical role in promoting multiple chronic diseases including those that appear to be driven by low dose chronic exposure to space radiation such as cancer, neurological, respiratory, and reproductive pathologies1,11,17. The same has been shown in studies examining the health of long-term air crews suggesting pathological consequences for Earth’s inhabitants as we continue to observe a weakening in the earth’s magnetosphere3,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. However, despite current evidence linking radiation exposure, SnC accumulation, and the development of chronic disease, an understanding of how space radiation may differentially induce senescence and potentially contribute to the high risk of chronic diseases in astronauts on long-duration space missions remains unknown.

The therapeutic benefit of selectively eliminating SnCs or attenuating their deleterious senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP) using genetic and pharmacologic clearance has been clearly demonstrated17,25,26. However, SnCs are highly heterogeneous and rely on varying senescence-associated regulatory networks specific to the inducer, tissue, cell type and stage of senescence, which limits the efficacy of current senotherapeutics16,25,27,28,29. Here, we demonstrate that human fibroblasts exposed to different forms of space radiation elicit greater induction of senescence-associated phenotypes including morphological alterations and the accumulation of SA-ß-gal+ cells compared to that observed following γ-irradiation. Bulk RNA-seq on primary dermal fibroblasts demonstrated similarities in the transcriptional profiles of space radiation-exposed cells highlighting chronic activation and adaption of the integrated stress response (ISR) as a key determinant of the space radiation phenotype. Single-cell RNA-seq analysis confirmed transcriptional similarity between space radiation-exposed cells but identified enrichment of NADPH-coupled redox pathways only in space irradiated cells. Transcriptional analysis of individual clusters demonstrated that clusters of space irradiated SnCs harbor non-canonical transcription factor activity profiles that were associated with large scale transcriptional repression particularly in those clusters present in space irradiated groups indicative of deep-irreversible senescence30. Healthy cells treated with conditioned media from irradiated cells demonstrated cell type dependent activation of differential acute inflammatory responses where conditioned media from γ- and H irradiated cells elicited a reponse in IMR-90 cells, whereas HDFs responded to Fe and H. Finally, treatments using three established senotherapeutics in primary human dermal fibroblasts revealed radiation-specific effects. These results demonstrate that space radiation differentially induces senescence in human cells, producing heterogeneity in irradiated cell populations that may play a driving force in the long-term effects of space travel. Thus, the use of space radiation-specific senotherapeutics may be an important strategy to mitigate senescence-driven pathologies that can develop after space radiation exposure.

Results

Charged particle space radiation promotes a more pronounced senescence-like phenotype compared to γ radiation

To begin to examine space-radiation induced senescence we exposed replicate cultures of IMR-90 human fetal lung fibroblasts and primary human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) to galactic cosmic radiation at 0.5 and 4.0 Gray (Gy) doses, mimicking NASA’s yearly limit for space radiation exposure in low earth orbit and the career exposure limit for NASA astronauts respectively2,10,31. At each dose, cells were irradiated with singular components of galactic cosmic rays including charged hydrogen (H), silicon (Si) and iron (Fe) particles, as well as gamma (γ) irradiation, which was used as a “terrestrial radiation” comparator. A mock-irradiated control was also included. After irradiation, cell passaging was tracked over 14 days, which revealed that exposure to either Fe or H irradiation had the most significant impact on passaging rate compared to the mock control, even at 0.5 Gy (Fig. 1a-e). At 14 days post irradiation, live brightfield imaging showed that irradiated cells also displayed senescence-like phenotypes such as hypertrophy, flattened, irregular morphology and the accumulation of cellular debris, which was more evident in cells exposed to charged particle (Si, H and Fe) space radiation (Supplementary Fig. S1 a, c). Finally, cells exposed to charged particles had a higher percentage of SA-ß-gal+ cells than the γ-irradiated controls regardless of dose (Fig. 1f,g; Supplementary Fig. 1b, d). Altogether, these results demonstrate that charged particle space radiation promotes greater induction of senescent-like phenotypes when compared to low-LET γ radiation.

(a) Experiment schematic for both IMR-90 and primary dermal fibroblasts (N = 2). (b-c) Two-week growth curve of IMR-90 (b) or HDF (c) cells irradiated with 0.5 Gy radiation or mock control. (d-e) Two-week growth curve of IMR-90 (d) or HDF (e) cells irradiated with 4.0 Gy radiation or mock control. (f-g) Quantification of IMR-90 (f) or HDF (g) SA-βgal staining shown in Figure S1. Values are percent of all stained nuclei ± S.E.M. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 vs mock controls. Abbreviations; Si, silicon ion; \(\gamma\), gamma; H, hydrogen; Fe, iron; HDF, primary human dermal fibroblasts; Gy, Grays.

The integrated stress response is a key phenotypic distinction between γ and charged particle space radiation in dermal fibroblasts

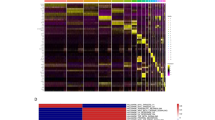

To begin to characterize senescence and examine the possibility of radiation-dependent senescent phenotypes, we conducted bulk RNA-sequencing of primary human dermal fibroblasts exposed to 4 Gy doses of radiation. Comparisons of significant (adjusted p-value < 0.05) differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between groups revealed that a majority were shared between charged particle irradiated samples (Fig. 2a,b). Analysis of senescence markers showed a significant reduction in the expression of markers associated with healthy and proliferating cells including nuclear lamina LAMINB1 and proliferation marker MKI67, but not PCNA (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Moreover, analysis of senescence-associated anti-apoptotic pathway genes showed significant up regulation of BCL2L1 and BCL2L2, but down regulation of BCL2. There was also a significant increase in CDKN2A and repression of CDKN1A as well an altered SASP transcriptional profile between charged particle and γ irradiated cells (Fig. 2c). Over representation analysis (ORA) found identical pathway enrichment profiles between charged particle irradiated samples with little overlap seen with those that were γ-irradiated, highlighting a phenotype associated with increased endoplasmic reticulum stress and reduced cytoplasmic translation in space irradiated dermal fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. 2b-c). To further investigate the space radiation-specific senescent phenotype, we conducted hierarchical clustering of pathways enriched using significant DEGs shared only between Si, H and Fe irradiated samples. Space radiation stimulated a transcriptional program associated with increased protein, endoplasmic reticulum, oxidative and HEME stress signaling, all of which are known activators of the ISR32,33,34 (Fig. 2d, Supplemental Table 1). In addition, pathways found to be repressed were associated with development, morphogenesis and differentiation of limbs, muscle and heart which were accompanied by the repression of small and large, but not mitochondrial, ribosomal protein transcripts (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 2b-d).

(a-b) Venn Diagrams comparing differentially expressed genes (DEG) significantly (adjust p-value < 0.05) (a) up- or (b) down-regulated vs the mock control between irradiated groups. (c) Heatmap showing the average Log2FoldChanges in senescence and SASP genes between treatment groups. (d-e) Tree plots showing hierarchical clustering of significantly enriched Gene Ontology (GO) pathways using over-representation enrichment analysis for (d) up- and (e) down-regulated pathways using genes that are significantly and commonly differentially expressed vs. Mock control between only charged particle space (Silicon, Hydrogen, Iron) irradiated cells filtering for p-value (adjusted p-value < 0.05) where Log2FoldChange cutoffs for up and down regulated input genes was > or < 0 respectively. (f) Heatmap showing the average Log2FoldChange (vs mock control) of integrated stress response (ISR) signaling genes. Abbreviations; ISR, Integrated Stress Response; GO, Gene Ontology.

Given that activation of the ISR is known to promote stress-associated transcriptional reprogramming and large-scale translational repression, space radiation specific pathway enrichment analysis suggests that the integrated stress response (ISR), and its adaption following chronic activation, may determine the senescence phenotype in cells exposed to charged particle irradiation. Transcriptional analysis of ISR regulators and effectors showed elevated expression of the positive ISR regulators GCN2, GADD34 and HRI and repression of the negative ISR regulator phosphatase CREP, suggesting chronic ISR signaling. Consistent with the repression of cardiac and muscle developmental pathways, we find that the main ISR effector transcription factor AFT4 was repressed whereas the other ATF family transcription factors were increased in space irradiated cells (Fig. 2f). These results demonstrate distinct induction of senescence phenotypes between γ- and space radiation in dermal fibroblasts associated with the chronic activation of the ISR resulting in an ATF4-independent adaptive transcriptional and translational reprogramming.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing reveals specific expression of NADPH-coupled redox pathways in space irradiated IMR-90 cells

To examine possible radiation specific senotypes, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on IMR-90 cells irradiated at 4 Gy. UMAP visualization of irradiated groups showed that mock control cells and a subset of H- and Fe-irradiated cells distinctly cluster from the main body of radiation exposed cells (Fig. 3a). Expression density distribution analysis of senescence markers revealed that cells exposed to charged particle radiation significantly increased the expression of positive SnC markers (CDKN1A, CDKN2A, BCL2L1 and BCL2L2) and downregulated negative SnC markers (MKI67 and LAMINB1) (Supplementary Fig. 3a,d,g). Importantly, Si-irradiated cells elicited the most significant alterations in the expression of these markers whereas γ-irradiated cells displayed the least (Supplementary Fig. 3a-i). We used the SenCID machine learning program using the SenCID5 signature for senescent fibroblasts, which denoted the majority of irradiated cells as SenCID5+ SnCs35 (Fig. 3c-b). In addition, the distribution of SenCID5+ SnCs was identical to the expression density distribution of positively correlated senescence markers, including clusters present in the mock control that are likely replicatively-induced SnCs (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 3a,d,g). Further, DEG analysis (SenSID5+ vs mock SenSID5-) revealed that SenCID5+ cells had increased expression of SASP transcripts regardless of the type of radiation exposure (Fig. 3d). Enrichment analysis and functional profiling of gene clusters highlighted similar repression of biological processes associated with mitotic division, double stranded DNA break repair, translation, respiration and mitochondrial transport between SenCID5+ cells (Fig. 3f). However, despite similar significant up-regulation of cell-substrate and various autophagy-related functional pathways, the SenCID5+ H-irradiated cells lacked significant differential up-regulation of peptidyl-serine mediated signal transduction associated with GTPase activity and neuronal axon extension associated with altered ion channel gene expression (Fig. 3e). Importantly, the space irradiated SenCID5+ cells specifically enriched a cluster of biological process GO terms associated with increased ATP metabolism, which were correlated to enrichment in molecular function pathways related to NADPH metabolism (Fig. 3e-g, Supplementary Table 3-4). Collectively, these results demonstrated that space radiation promotes a greater induction of senescent phenotypes in IMR-90 cells compared to γ-irradiated cells, which is correlated with increased activation of NADPH-fueled redox systems, likely as a protective mechanism against mitochondrial ROS damage.

(a) UMAP of different samples in the Seurat object. (b) UMAP showing cells identified as senescent using the SenCID5 mode of the SenCID program. (c) Violin plot showing the normalized SenCID5 score per cell, box plots are displayed along with the mean expression per sample shown as a diamond. Significance was determine using Kruskal-wallis test, p values are present above brackets and are all vs mock control sample. (d) Heatmap showing the average Log2FoldChange of SASP genes vs SenCID5 identified non-senescent cells. (e-f) Biological theme comparison graphs showing hierarchical clustering of significantly enriched GO BP pathways that were found to be (e) up- or (f) down-regulated when using significantly (adjusted p-value < 0.05) differentially expressed genes (vs SenCID5- Mock cells). Colors on node pie charts indicate samples that show enrichment in each hierarchical cluster group. (g) Biological theme comparison graph displaying significant up-regulation of GO Molecular function pathways associated with the enrichment of the purine ATP phosphate electron group in Fig. 3e.

Space radiation induces aberrant transcriptional repression

Despite the profound similarities observed between space- and γ- irradiated IMR-90 cells, the variation in enriched terms seen between the irradiated groups along with the differential expression of some SASP factors suggests radiation-specific cellular heterogeneity. Clustering analysis identified 23 distinct clusters largely unshared between radiation treatments (Fig. 4a-b, Supplementary Fig. 4a). Consistent with the SenCID5 scoring and transcriptional analysis of senescence-related markers, the mock cells identified as SenCID5- clustered together (clusters 8,9) and were the only clusters that had significantly up-regulated pathways associated with mitotic division, which were significantly repressed in the majority of SenCID5+ clusters (Supplementary Fig. 4b,d-e). Furthermore, the greatest variation between clusters is the enrichment of ATP metabolism where significant upregulation was found in clusters 0 and 4, which make up most of the H-irradiated population, and clusters 10 and 14, which are present in all radiation groups. Notably, the greatest source of variability was in the dysregulation of many processes associated with signal transduction, morphogenesis, differentiation, development and others classified in the up-regulated, “cell organization assembly” and repressed “adhesion morphogenesis differentiation” higher group classifications (Supplementary Fig. 4d-e).

(a) UMAP displaying all irradiated conditions and the mock control. (b) UMAP showing clusters present within each condition. (c) Heatmap showing the average Log2FoldChange of SASP genes that are significantly different (adjusted p-value < 0.05) in at least one cluster. (d) Heatmap showing transcription factor activity z-scores of the transcription factors that had the greatest variance regarding transcription factor activity. (e) Heatmap showing the average Log2FoldChange of SMAD3 target genes per cluster (bottom panel) and SMAD3 mode of transcriptional regulation (top panel) derived from CollecTRI, which is being used here as a representative depiction for dysregulated transcription factor activity where a value of 1 indicates up regulation and -1 is indicative of down regulation of Smad3 target genes. (f) Average number of Consecutive geographic silencing events defined as chromosomal regions that contain 10 or more consecutive genes that are within 1e6 bp of each other to be transcriptionally repressed (log2FC < -0.75 vs the SenCID5- mock clusters (combination of cluster 8 and 9)) in each treatment group.

Given the implications of ATF4 in regulating many of these pathways, we investigated the expression of binding partners and effectors of ATF4 known to play a critical role in regulating the ISR as well as muscle, cardiac, neuronal and limb development and differentiation. Interestingly, there was differential expression of these genes in many clusters suggesting a source of phenotypic variation among clusters dependent on transcriptional reprogramming (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Many of the clusters repressed multiple SASP transcripts with significant up-regulation in very few SASP factors per cluster (Fig. 4c). There was also evidence of transcriptional repression with little impact on translation except for global cytosolic repression of cytosolic ribosomes in clusters 16, 17,19 and 5 (Supplementary Fig. 4d-e). In addition, transcription factor activity analysis identified significant differential activity of transcription factors associated with senescence, differentiation, extracellular matrix, cell adhesion and other processes highlighted in our enrichment analysis (Fig. 4d). However, when mapping the expected regulatory action of the transcription factor over the target genes, we find that many transcription factors exhibit dysfunctional activity (Fig. 4e). Given the extent of transcriptional repression and altered transcription factor landscape observed in irradiated cells, we wanted to investigate whether these transcriptional alterations could be due to geographical clustered events of transcriptional inactivation recently observed in senescent fibroblasts associated with epigenomic and architectural changes recently observed in SnCs and thought to be an indicator of a deep, irreversible senescent state30,36. To investigate this, we calculated the frequency of geographically localized gene repression (10+ consecutive genes) across somatic chromosomes per cluster and found that clusters dominantly comprised of Si-irradiated cells had the largest number of consecutive silencing events followed by γ and Fe- irradiated cells whereas SenCID5+ mock cells had the least (Fig. 4f). However, when looking at the average number of consecutive silencing events per treatment, we find that H-irradiated cells had the second highest number of average silencing events despite being comprised of low event containing clusters (Supplementary Fig. 4f). Thus, our data suggests that the catabolic SASP bulk phenotype of IMR-90 cells exposed to radiation is dependent on the presence of clusters that harbor phenotypic alterations regulated by adaption of the ISR and stress-associated geographical silencing that promotes the appearance of a common senescence phenotype.

Space radiation influences the senescence-associated secretory phenotype and paracrine signaling

We investigated the paracrine effects of irradiated SnCs by treating low passage (P4) proliferating IMR-90 and HDF cells with conditioned media for 48 h. Although the treatment did not result in significant differences in the relative expression of the classic senescence and SASP markers (p16INK4a, p21Cip1, IL-6, IL-1ß), space radiation significantly impacted the expression of other SASP and senescence markers in a manner that was both radiation and cell-type specific (Fig. 5b-k; Supplementary Fig. 5a-b). To further examine the paracrine effects of space irradiated SnCs, HepG2 cells were transfected with the cis-FACTORIAL panel of transcription factor reporters and treated with conditioned media (CM) for 24 h. Treatment with CM from cells exposed to space radiation significantly decreased TGF-ß activity and increased BRE activity (Fig. 5l-m). In addition, when comparing transcription factor activity normalized to the mock control, there was small, but significant up regulation of p53 transcription factor activity in all conditions in both cell types. CM from IMR-90s showed significant space radiation specific effects in the ability to alter transcriptional factor activity of E2F, STAT3, and ISRE, while CM from HDFs altered NRF2/ARE and AP-1 showed the most significant space radiation specific alterations. Interestingly, the transcription factors NF-κB and C/EBP, which are primary regulators of SASP, did not exhibit significant alterations in activity, possibly due to the acute treatment. Consistently, results from CM experiments on healthy proliferating cells show no alterations in the expression of classical SASP markers like IL-1ß and IL-6 (Fig. 2d,e). Collectively, these data demonstrate that exposure to different types of space radiation produces distinct SASP profiles able to induce diverse responses through paracrine signaling to healthy cells.

(a) Experimental schematic for the transcription factor response experiments and paracrine effects experiments using conditioned media collected starting 1 week post irradiation. (b-k) RT-qPCR of senescence associated secretory factors 48 h post conditioned media (CM) treatment on low passage proliferating IMR-90s (b,c,g,h) and (d-f, i-k) primary dermal fibroblasts (n = 3). The data shown as fold induction vs. mock control treated cells normalized to mock controls and GAPDH (n = 3) ± S.E.M. (l-m) Transcription factor activity post conditioned media treatment (100uL/mL) from IMR-90 (l) or HDF (m) cells exposed to 4 Gy radiation in HepG2 cells transfected with cis-FACTORIAL after 24 h. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. Abbreviations; Si, silicon ion; \(\gamma\), gamma; H, hydrogen; Fe, iron; HSF, primary human skin (dermal) fibroblasts; Gy, Grays.

Space radiation differentially influences senotherapeutic impact on irradiated primary dermal fibroblasts

To determine if the different space radiation-induced senotypes respond similarly to senotherapeutics, we used primary dermal skin fibroblasts irradiated with the anticipated absorbed dose astronauts are expected to receive during a mars mission (0.5 Gy)1,2,10. Three established senotherapeutics, (the combination of dasatinib and quercetin (D + Q), fisetin, and navitoclax) were used to treat the senescent fibroblasts for 48 h before fluorescence-based detection of SA-ßgal+ cells using C12FDG staining. In γ irradiated fibroblasts, all three senotherapeutics had senolytic activity, and significantly reduced both the number of C12FDG + cells and the total population (Fig. 6a-c). Si irradiated cells show similar senolytic results following treatment with fisetin and D + Q but only showed a significant reduction in the C12FDG+ population following navitoclax treatment, indicative of senomorphic activity (Fig. 6d-f). Further, in H-induced senescence, all senotherapeutics demonstrated senomorphic activity, significantly reducing the number of C12FDG+ SnCs, but not the total cell number (Fig. 6g-i). Finally, fisetin and navitoclax had senomorphic effects on Fe irradiated cells whereas D + Q had no effects on either the C12FDG+ or total cell population. These results suggests that senotherapeutic activity is radiation specific and tailored senolytics designed for charged particle space radiation specific SASP ablation could be a useful countermeasure for space radiation exposure.

Quantification of C12FDG senescence assay on fibroblasts exposed to 0.5 Gy (a-c) Gamma, (d-f) Silicon, (g-i) Hydrogen, (j-l) Iron radiation treated for 48 h with (a,d, g, j) 20uM fisetin (b, e, h, k) the combination of 125 nM dasatinib and 25uM quercetin (DQ) or (c, f, i, l) 10uM Navitoclax. Values are the number of all stained nuclei (total cells) or live cells that are C12FDG+ (C12+) normalized to the respective DMSO control treated cells ± S.E.M. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 (n = 3).

Discussion

The damaging potential of galactic cosmic rays is largely due to the presence of high-energy protons and HZE particles, including Si and Fe atoms that have a higher DNA damaging potential than “terrestrial” γ radiation which can drive cells into senescence5,12. Thus, here we compared senescence induced by different types of galactic cosmic rays and demonstrated that charged particle space irradiation (H, Si and Fe) significantly reduced cell proliferation and increased the frequency of SA-βgal+ cells in vitro when compared to γ-irradiation. RNAseq analysis showed that HDFs exposed to charged particle irradiation shared a majority of DEGs with pronounced up-regulation of pathways associated with stress signaling including responses to ER stress, hemostasis, oxygen levels, and unfolded proteins. The diversity of significantly up-regulated stress pathways observed only in charged particle irradiated cells not only reflects the increased damaging potential of space radiation but also implicates activation of the integrated stress response (ISR) as a key phenotype of space radiation induced senescence compared γ and mock control cells32,33,37. The increased expression of many positive ISR regulators including GCN2, HRI, and GADD34 in charge particle irradiated cells, along with repression of the ISR terminating phosphatase CREP suggests that space radiation induces sufficient damage to promote the chronic activation of the ISR.

Chronic activation and adaption of the ISR is associated with induction of undefined stress response branches9,37,38,39. Indeed, we find that the ISR response in charge particle exposed cells deviates from canonical signaling demonstrated by the significant repression of the main effector of the ISR ATF4. Interestingly, while there was reduced ATF4 mediated transcriptional and translational reprogramming in enrichment analysis as indicated by the downregulation of ATF4 mediated muscle developmental and differentiation pathways, we still observe evidence for persistent ATF4-mediated translational repression34,40,41,42. However, the increase in GADD34 suggests alternative mechanisms for ISR mediated translation repression that may permit the translation of SASP, likely dictated by ISR branches associated with endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial unfolded protein response43,44,45,46,47,48.

Due to the metabolic demands associated with synthesizing and secreting catabolic factors present in the SASP, SnCs also exhibit electron transport chain and oxidative phosphorylation dysregulation associated with the increased production of mitochondrial free radicals44,49,50. Interestingly, our scRNA-seq analysis identified a significant up-regulation of mitochondrial NADPH-coupled redox processes specifically in space irradiated cells. Metabolic reprogramming induced through the cross talk between branches of the ISR and mitochondrial UPR has been previously identified as an adaptive response to improve a cell’s ability to handle stress by upregulating enzymes involved in the one-carbon folate cycle as well as cysteine, serine, amino acid, and nucleotide biosynthetic pathways51,52. This promotes the maintenance of reduced glutathione and thioredoxin, thereby increasing the antioxidant capacity of these cells to protect them against intramolecular ROS and supporting anabolic metabolism for cellular repair53. Thus, ISR and UPR mediated NADPH metabolic reprogramming may serve as a potential senotherapeutic target in human cells exposed to space radiation.

Our scRNA-seq data highlighted significant enrichment in many pathways associated with signal transduction, morphogenesis, differentiation, and development that have been tied to dependence on ATF4-mediated transcriptional and translational reprogramming. This, along with differential expression of ATF4 regulatory partners seen between clusters suggests that cellular heterogeneity observed between SenCID5+ clusters is dependent on the extent of ISR adaption and likely the dominating stressor. However, we find that regardless of differential ISR adaption, the majority of SenCID5+ clusters underwent large scale transcriptional repression of SASP transcripts that resulted in specific SASP transcriptional profiles, suggesting that a few SnCs are responsible for the increased catabolic SASP identified in bulk transcriptional analysis. Recently, it has been found that SnCs exhibit significant geographical silencing events over large regions of the chromosome that contained genes associated stress response programs associated with RNA and protein metabolism30. Thus, given that we observe a high burden of geographical transcriptional repression associated with many stress responses, it is possible that chronic ISR activation and subsequent adaption of metabolic programs and gene regulatory mechanisms will invoke a deep senescent state by undergoing many geographical silencing events over time. If true, geographical silencing events, rather than transcriptional analysis alone, may serve as a valuable biomarker for SnC heterogeneity and further implicates the importance of increasing our knowledge surrounding ISR mediated regulation of senescence phenotypes for the identification of improved senotherapeutic targets.

Despite transcriptional phenotypes suggestive of transcriptional dysregulation and reduced translation, we observe up-regulation of pathways associated with growth factor, interleukin, and ECM induced extrinsic stress signaling responses, which implicates a deleterious impact on neighboring cells and tissue functionality. While transcriptional analysis showed a more pronounced SASP expression in charged particle irradiated cells, conditioned media experiments demonstrated that the activity of only a few transcription factors were affected in healthy HepG2 cells. However, the impact on transcription factor activity was both radiation and cell type specific. In agreement with our sequencing data, we find that conditioned media from IMR-90s irradiated with γ-irradiation promoted a greater transcriptional response than conditioned media from γ-irradiated HDFs, validating the differential impact of γ and space irradiation observed between HDFs and IMR-90s in our transcriptional analysis. Moreover, conditioned media treatments in HDFs significantly increased the expression of more inflammatory and catabolic factors compared to the IMR-90s, which was more prominent in H and Fe irradiated HDFs. Of note, we observe that differences observed between IMR-90 and primary dermal fibroblasts are associated with regulatory functions of dermal fibroblasts, which increase platelet derived growth factor production to promote dermal wound healing in response to tissue damage54,55. Thus, our data collectively demonstrates that space radiation induces a more pronounced senescence phenotype with increased catabolic paracrine capabilities that will likely exacerbate tissue damage and chronic disease when compared to γ radiation.

Given that space radiation produces a senescent phenotype distinct and potentially more deleterious than γ irradiation along with the acknowledgement that senotherapeutics are context specific in their efficacy, we tested the effects of three established senotherapeutics on HDFs11,17,25,26,56,57,58. In agreement with current literature, we find that all compounds exhibited senolytic activity in γ irradiated cells. However, we begin to see differential senotherapeutic effects in cells irradiated with charged particle irradiation where all compounds exhibited only senomorphic effects in H irradiated cells while Fe irradiated SnCs were unaffected by D + Q. These data would suggest that treatment with fisetin or navitoclax may be advantageous for protection against space radiation. We note that the variation seen between senotherapeutic effects is likely driven by alternative dependence of ISR-relates SCAPs, like NADPH metabolism, which represents a target for the development of novel senolytics as space radiation countermeasures.

Methods

Cell culture and irradiation

Primary Human Dermal cells (HDFs) were cultured in αMEM with nucleosides and glutamine (Gibco), supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), and non-essential amino acids. IMR-90 human fibroblasts were obtained from ATCC and cultured in MEM (Gibco), supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), and non-essential amino acids (Gibco) and sodium pyruvate (Gibco). The cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 20% O2. All cells were seeded at 50% confluence and replicate cultures were shipped overnight to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Space Radiation Laboratory at Brookhaven National Laboratory. During shipment cells were not maintained under controlled thermal and atmospheric conditions. Upon arrival, cells, including the mock control, were allowed to recover from shipment overnight prior to radiation exposure and irradiation, carried out as described previously59. Briefly, irradiations were carried out with particle beams for Hydrogen (H), Silicon (Si), Iron (Fe) using particle energies of 150, 238 and 600 MeV/n with LET values of 0.5, 79 and 174 keV/μm respectively. For γ-irradiation, a 137Cs source (JL Shepard and Associates, CA) was used. All cells, regardless of types of radiation exposure, received final doses of 0.5 Gy or 4.0 Gy. Following exposure to space radiation, a media change was preformed, and cells were allowed to rest overnight prior to overnight shipment back to the University of Minnesota where they were allowed to rest another 13 days to allow senescence induction. During senescence induction medium was replaced and collected every 2–3 days and routine passaging was conducted. Upon visual confirmation of 85–100% confluence, replicate cultures for each condition were passaged at the same time and passaging was recorded as a measure of cellular replication. After 14 days of senescence induction, passaging rate was graphed and area under the curve analysis was preformed and a one-way ANOVA was utilized for statical analysis. Replicate cultures of cells were independently shipped and irradiated twice (N = 2).

Senotherapeutic assay

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase was tested using the C12FDG substrate, which becomes fluorescent when hydrolyzed by SA-β-galactosidase. HDFs irradiated with 0.5 Gy radiation were plated in 96-well black wall clear bottom plates (Corning) in triplicate at a density of 2000 cells/well. Cells rested overnight before a 48 hr treatment of fisetin (20 μM), Dasatinib (12 nM) and quercetin (25μM) (D + Q), navitoclax (10μM) or DMSO control (n = 3). All senotherapeutic compounds were purchased from Cayman Chemical. Drug incubation was 48 h in 200uL total volume media + drug. After incubation, drug + media were removed and cells were incubated with bafilomycin A1 (100 nM) (Cayman Chemical) in culture medium for 1 hour to induce lysosomal alkalinization. Cells were then incubated with 20μM (IMR-90) or 30μM (HDF) fluorogenic substrate C12FDG (Invitrogen) in media containing 100 nM bafilomycin A1 for 2 h. Cells were then counterstained with 2 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) for 15 min washed 1x with DPBS, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 mins at room temperature, washed 2x with DPBS, imaged in six fields per well using the high-content fluorescence image acquisition and analysis platform Cytation 1 and analyzed using Gen5 software (BioTek, USA). All incubations up to fixation occurred at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 20% O2. Relative cells populations are representative of all stained nuclei (Total cells) or live cells that are C12FDG+ normalized to the respective DMSO control treated cells and analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA n = 3 per group.

RNA extraction and qRT‒PCR

Total RNA was isolated from fibroblasts using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Following cell lysis, chloroform was added to the TRIzol slurry and incubated prior to centrifugation at 12,000RPM for 15 min at 4°C. RNA extraction on the aqueous phase of the centrifuged homogenate was performed using Invitrogen PureLink RNA Mini Kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, USA) and stored at -80°C until further use. For the synthesis of cDNA, RNA was reverse transcribed using a high-capacity revers transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol where all reactions utilized the sample RNA input and reaction volume. Quantitative polymerase chain reactions were set up in a MicroAmp Fast Optical 96-well reaction plate with 8 μL of diluted cDNA (20 ng total based on RNA input into cDNA reaction), and 12 μL Power UP of SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA)/well with each reaction having a final concentration of 300 nM of each specific oligonucleotide primers (Table 1) and were run using the fast reaction thermocycling conditions. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as a housekeeping gene. The data were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method. Graphs showing the expression of a singular gene between conditions (n = 3) utilized a one-way ANOVA whereas graphs showing the analysis of multiple genes and conditions utilized a 2-way ANOVA for statistical analysis.

Bulk RNA sequencing

Human dermal fibroblasts irradiated with 4 Gy H, Si Fe and γ radiation as well as the mock control and were washed 1x with DPBS (Gibco), trypsinized with TrpLE (Gibco), pelleted via centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 5 mins before being snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80C before RNA extraction (n = 3). RNA extraction was done using 1 mL TRIZOL as described above, with the addition of an on-column DNase digestion as described by the from Invitrogen PureLink RNA Mini Kit’s instructions and was eluted in ultra-pure sterile water (Invitrogen). Library preparation and sequencing was performed at the University of Minnesota Genomics Center. Unique dual indexed paired-end TruSeq stranded libraries were created and pooled following rRNA depletion using the Ribo-Zero Plus rRNA Depletion kit. All libraries were gel size selected (\(\approx\) 200 bp) and sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq X Lane with a 2 x 150 bp flow cell. Libraries were sequenced to a mean depth of \(\ge\)20 M reads. Fastqc files were processed using Trimmomatic for the removal of adapter sequences and bases having a Q-score < 30. The quality of trimmed fastqc files were confirmed using FastQC. Paired-end reads were aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome using Hisat2 v2.0.5 and feature Counts v1.5.0 was used to count and map each gene. Pre-filtering removing low count reads (\(\le 5\)) and Differential Gene expression (DEG) analysis was done in R v4.1.0 using the package DESeq2 v3.19 with the experimental design ~ Condition, using default statistic (Wald) and fit (parametric) parameters using a false discovery rate cut off of 0.0560. Ensemble IDs were converted to HGNC IDs and entrez IDs using the R package biomaRT. Differentially expressed genes with adjusted p-values < 0.05 were selected for downstream over representation analysis (ORA) using the package ClusterProfiler for enrichment analysis and visualization of pathways present in the Hallmark collection from the Molecular Signatures Database and Gene Ontology (GO) pathways61,62,63. Unless otherwise stated, cut off values for significantly up or down regulated DEGs for ORA analysis was and average Log2FoldChange (vs Mock) = 0 and a adjusted p value < 0.05.

Library preparation for single cell RNA sequencing analysis

Single-cell libraries were prepared by trypsinizing and pooling replicate cultures of IMR-90 fibroblasts (n = 3) exposed to 4 Gy radiation and mock control. Cells were trypsinized using TrpLE (Gibco) and examined for viability ( > 80%) through trypan blue staining. Cells were resuspended in MEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS in 100uL at 1500 cells/uL for subsequent library preparation and sequencing provided by the University of Minnesota’s Genomics Center. Briefly, library construction was done using Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3ʹ dual index Kits v3.1 with Chip G (10x Genomics). Live suspensions of ~10,000 single cells were loaded for generation of gel bead-in-emulsions (GEMs), the captured cells were lysed, and the RNA was barcoded while reverse-transcribed in each GEM. GEMs were then broken, and the synthesized cDNA was used for library preparation following the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA quality was assessed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer with Pico-green (Agilent). The libraries underwent additional QC by shallow-sequencing using an Illumina NextSeq instrument. Final library sequencing was done using an Illumina Nova Seq S4 lane capturing ~ 20,000 paired-end reads per cell. 10x sequencing libraries were converted into feature-barcode matrices following the Cell Ranger (10x Genomics, version 5.0.0) pipeline. After demultiplexing, the function ‘cellranger count’ was used with default parameters, reads were mapped using the Cell Ranger prebuilt annotation platform GRCh38.

scRNA-seq QC and clustering

Subsequent analysis of obtained read count matrices was carried out using the R package Seurat, version 5.0.164,65. Using Seurat, we filtered out cells with low feature count ( < 200 genes), high mitochondrial RNA content ( > 10%) with more stringent cutoffs being determined through examination of the coefficient of determination value (R2 = 0.95) for the line describing the relationship for nCount_RNA vs nFeature_RNA leading to an nCount < 20000 threshold. Each sample was normalized using the ‘LogNormalize’ method using the ‘NormalizeData’ function, and the top 3000 highly variable genes were selected from individual samples with the function ‘FindVariableFeatures’. The top 50 principal components, determined by the ‘ElbowPlot’ method, were applied for two-dimensional data visualization with the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) via ‘RunUMAP’ function. Clusters were identified using the Louvain algorithm with a resolution of 0.8. All functions utilized default parameters.

Identification of senescent cells in scRNA-seq data sets

Using the machine learning program SenCID we identified senescent IMR-90 fibroblasts using the SenCID5 gene signature as using the standard described workflow and parameters35.

scRNA-seq cluster identification and DEG list generation

For analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for SnCs identified in each sample, we used the function ‘FindMarkers’ comparing the SenCID5+ cells present in each sample with the SenCID5- cells present in the Mock control. When comparing clusters, the function ‘FindAllMarkers’ was employed to find marker genes that characterized a specific cluster compared to all other clusters.

scRNA-seq pathway enrichment analysis

Before over-representation pathway enrichment analysis common gene symbols were converted into Entrez gene ids and ensemble ids using the R package biomart, version 3.18. Over-representation analysis (ORA) and subsequent visualization of Gene Ontology (GO) terms was conducted using ClusterProfiler (version 3.18.1) using comparisons, Log2FoldChange and adjusted p-values as described in figure legends.

Identification of transcription factor activity in scRNA-seq

To examine transcription factor activity we used the decoupleR package (v2.2.1) and the curated CollecTRI collection of TFs and their transcriptional targets specifying human regulon targets66,67. Pseudo bulk expression data per cluster was obtained using Seurat and the univariate linear model method was utilized for determination of transcription factor activity when using a regulon size minimum of five targets. The top 50 most variable transcription factors were identified based on the standard deviation of their activity scores. The regulatory actions on SMAD3 target genes was utilized as a representative example of one of the significantly differentially active transcription factors with dysregulated activity. Canonical transcription factor activity was derived from the CollecTRI metadata and presented in a 2-color scale demonstrating if the regulatory action of SMAD3 as either an activator or repressor of transcription.

Identification of geographical silencing events in scRNA-seq

Consecutive downregulated genes were detected using the following algorithm. First, we filtered relevant DEG lists for a given clusters such that it only contained DEGs whose adjusted p-value was less than 0.05. Then, the list of DEGs was ordered based on chromosome location and transcription start site such that the first gene in the list was the first DEG on chromosome 1, the second gene in the list was the second DEG on chromosome 1 and so forth. We then searched this list to find geographic silencing events where 10 genes in a row were all downregulated (LFC < -0.75) and each gene of those 10 genes were located within 1e6 base pairs of its neighbors.

Transcription factor activity using cis-factorial

Conditioned media collected days 7–14 post irradiation were combined and concentrated 10X following 1000xg centrifugation at 4 C for 10 mins using Vivaspin 10 kDa centrifugal concentrators (Sartorius) as described by the manufacturer. Concentrated samples were snap frozen and sent to Atta Gene Inc. for transcription factor activity using the cis-factorial assay in HepG2 cells treated with concentrated conditioned media diluted to 1X in DMEM containing 1% charcoal treated FBS in 12-well plates for 24 h (n = 3).

Conditioned media treatments on fibroblasts

Concentrated Conditioned media, collected as described above, were used to treat low passage (p4) proliferating IMR-90 or primary dermal fibroblasts seeded at 150,000 cells/well in 6-well plates for 48 h at a concentration of 1x in growth media before collection for qPCR analysis (n = 3).

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-ß-gal) staining

At 14 days post irradiation cells were seeded at 45,000 cells per 24-well and allowed to settle overnight before fixation and SA-ß-gal staining using the Senescence β-galactosidase kit (Cell Signaling Technology) as described by the manufacturer. Following staining cells were washed 1x with DPBS then counterstained with 2 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) for 20 min at room temperature and washed 3x with DPBS before imaging using the high-content image acquisition and analysis platform Cytation 1 and analyzed using Gen5 software (BioTek, USA). Cell populations are representative of only Hoechst stained nuclei and analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA.

Statistical analysis

The results above are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made by ordinary one- or two-way ANOVA to compare between groups where statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed as described in methods sections using GraphPad Prism version 10.4.1 (Boston, Massachusetts USA). Statical analysis for bioinformatic analysis occurred as described in the methods sections utilizing default parameters in the R packages DESeq2, Seurat and ClusterProfiler where significance was defined as have an adjusted p-value (padj) <0.05.

Data availability

The scRNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE297559. The bulk RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the GEO database under accession code GSE297560.

References

Chancellor, J. C. et al. Limitations in predicting the space radiation health risk for exploration astronauts. NPJ Microgravity 4, 8 (2018).

Cucinotta FA, K. M., Chappell LJ. Space Radiation Cancer Risk Projections and Uncertainties. NASA Technical Publication, 2-132 (2010).

Danho, S., Thorgrimson, J. & Saary, J. in Handbook of Space Pharmaceuticals 371-388 (Springer, 2022).

Hagiwara, Y. et al. Clustered DNA double-strand break formation and the repair pathway following heavy-ion irradiation. J. Radiat. Res. 60, 69–79 (2018).

Mukherjee, B., Camacho, C. V., Tomimatsu, N., Miller, J. & Burma, S. Modulation of the DNA-damage response to HZE particles by shielding. DNA Repair 7, 1717–1730 (2008).

Nakano, T. et al. Formation of clustered DNA damage in vivo upon irradiation with ionizing radiation: Visualization and analysis with atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2119132119 (2022).

Azzam, E. I., Jay-Gerin, J. P. & Pain, D. Ionizing radiation-induced metabolic oxidative stress and prolonged cell injury. Cancer Lett. 327, 48–60 (2012).

Sridharan, D. et al. Understanding cancer development processes after HZE-particle exposure: roles of ROS, DNA damage repair and inflammation. Radiat. Res. 183, 1–26 (2015).

Kumar, S., Suman, S., Fornace, A. J. Jr & Datta, K. Space radiation triggers persistent stress response, increases senescent signaling, and decreases cell migration in mouse intestine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E9832–E9841 (2018).

Officer, N. O. o. t. C. a. M. Design for Ionizing Radiation Protection. NASA-STD-3001 Technical Brief OCHMO-TB-020 Rev E, 1–14 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Cellular senescence: a key therapeutic target in aging and diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 132 (2022).

Rodier, F. et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 973–979 (2009).

Lee, K.-A., Flores, R. R., Jang, I. H., Saathoff, A. & Robbins, P. D. Immune senescence, immunosenescence and aging. Front. Aging 3, 900028 (2022).

Tasdemir, N. et al. BRD4 Connects Enhancer Remodeling to Senescence Immune Surveillance. Cancer Discov. 6, 612–629 (2016).

Acosta, J. C. et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 978–990 (2013).

Fletcher-Sananikone, E. et al. Elimination of Radiation-Induced Senescence in the Brain Tumor Microenvironment Attenuates Glioblastoma Recurrence. Cancer Res 81, 5935–5947 (2021).

Zhang, L., Pitcher, L. E., Prahalad, V., Niedernhofer, L. J. & Robbins, P. D. Recent advances in the discovery of senolytics. Mechanisms Ageing Dev. 200, 111587 (2021).

McNeely, E., Mordukhovich, I., Tideman, S., Gale, S. & Coull, B. Estimating the health consequences of flight attendant work: comparing flight attendant health to the general population in a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 18, 346 (2018).

Sanlorenzo, M. et al. The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 151, 51–58 (2015).

McNeely, E. et al. Cancer prevalence among flight attendants compared to the general population. Environ. Health 17, 49 (2018).

Whiteside, M. & Herndon, J. M. New paradigm: Coal fly ash as the main cause of stratospheric ozone depletion. Eur. J. Appl. Sci.–Vol 10 (2022).

Lorenzen, B. Earth’s magnetic field—The key to global warming. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 7, 25–38 (2019).

Kumar, G. & Kumar, M. Depletion of ozone layer: Review in reference to galactic radiations. Environ. Conserv. J. 26, 249–256 (2025).

Christoudias, T. et al. Earth’s atmosphere protects the biosphere from nearby supernovae. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 326 (2024).

Zhang, L., Pitcher, L. E., Prahalad, V., Niedernhofer, L. J. & Robbins, P. D. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: senolytics and senomorphics. Febs j. 290, 1362–1383 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 14, 644–658 (2015).

Mahmud, S. et al. Developing transcriptomic signatures as a biomarker of cellular senescence. Ageing Res Rev. 99, 102403 (2024).

Xu, M. et al. Targeting senescent cells enhances adipogenesis and metabolic function in old age. Elife 4, e12997 (2015).

Xu, M. et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med 24, 1246–1256 (2018).

Gurkar, A. U., Okawa, S., Guillermier, C., Chaddha, K. & Steinhauser, M. L. Large-Scale Clustered Transcriptional Silencing Associated With Cellular Senescence. Aging Cell n/a, e70015 https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.70015.

Shavers, M. et al. Space agency-specific standards for crew dose and risk assessment of ionising radiation exposures for the International Space Station. Z. Med Phys. 34, 14–30 (2024).

Pakos-Zebrucka, K. et al. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep. 17, 1374–1395 (2016).

Costa-Mattioli, M. & Walter, P. The integrated stress response: From mechanism to disease. Science 368 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat5314.

Nabeebaccus, A. A. et al. The regulation of cardiac intermediary metabolism by NADPH oxidases. Cardiovascular Res. 118, 3305–3319 (2022).

Tao, W., Yu, Z. & Han, J. J. Single-cell senescence identification reveals senescence heterogeneity, trajectory, and modulators. Cell Metab. 36, 1126–1143.e1125 (2024).

Chousal, J. et al. Chromatin Modification and Global Transcriptional Silencing in the Oocyte Mediated by the mRNA Decay Activator ZFP36L2. Dev. Cell 44, 392–402.e397 (2018).

Guan, B. J. et al. A Unique ISR Program Determines Cellular Responses to Chronic Stress. Mol. Cell 68, 885–900.e886 (2017).

Boone, M. & Zappa, F. Signaling plasticity in the integrated stress response. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 11 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2023.1271141.

Lehman, S. L., Ryeom, S. & Koumenis, C. Signaling through alternative Integrated Stress Response pathways compensates for GCN2 loss in a mouse model of soft tissue sarcoma. Sci. Rep. 5, 11781 (2015).

Neill, G. & Masson, G. R. A stay of execution: ATF4 regulation and potential outcomes for the integrated stress response. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 16 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2023.1112253.

Ebert, S. M. et al. Biology of Activating Transcription Factor 4 (ATF4) and Its Role in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. J. Nutr. 152, 926–938 (2022).

Schneider, K. et al. Protein Stability Buffers the Cost of Translation Attenuation following eIF2α Phosphorylation. Cell Rep. 32, 108154 (2020).

Hasnain, S. Z., Lourie, R., Das, I., Chen, A. C. & McGuckin, M. A. The interplay between endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation. Immunol. Cell Biol. 90, 260–270 (2012).

Lee, Y. H. et al. Targeting Mitochondrial Metabolism as a Strategy to Treat Senescence. Cells 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113003.

Mazumder, B., Li, X. & Barik, S. Translation control: a multifaceted regulator of inflammatory response. J. Immunol. 184, 3311–3319 (2010).

Vind, A. C., Genzor, A. V. & Bekker-Jensen, S. Ribosomal stress-surveillance: three pathways is a magic number. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 10648–10661 (2020).

Zdrazilova, L. et al. Metabolic adaptation of human skin fibroblasts to ER stress caused by glycosylation defect in PMM2-CDG. Mol. Genet. Metab. 139, 107629 (2023).

Bhattarai, K. R., Riaz, T. A., Kim, H.-R. & Chae, H.-J. The aftermath of the interplay between the endoplasmic reticulum stress response and redox signaling. Exp. Mol. Med. 53, 151–167 (2021).

Hutter, E. et al. Senescence-associated changes in respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in primary human fibroblasts. Biochem J. 380, 919–928 (2004).

Payea, M. J. et al. Senescence suppresses the integrated stress response and activates a stress-enhanced secretory phenotype. bioRxiv (2023). https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.12.536613.

Labbé, K. et al. Specific activation of the integrated stress response uncovers regulation of central carbon metabolism and lipid droplet biogenesis. Nat. Commun. 15, 8301 (2024).

Martínez-Reyes, I. & Chandel, N. S. Mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism maintains redox balance during hypoxia. Cancer Discov. 4, 1371–1373 (2014).

Balsa, E. et al. Defective NADPH production in mitochondrial disease complex I causes inflammation and cell death. Nat. Commun. 11, 2714 (2020).

Cañedo-Dorantes, L. & Cañedo-Ayala, M. Skin acute wound healing: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Inflamm. 2019, 3706315 (2019).

Sadeghi-Ardebili, M., Hasannia, S., Dabirmanesh, B. & Khavari-Nejad, R. A. Functional characterization of the dimeric form of PDGF-derived fusion peptide fabricated based on theoretical arguments. Sci. Rep. 14, 1003 (2024).

Chang, J. et al. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat. Med. 22, 78–83 (2016).

Roos, C. M. et al. Chronic senolytic treatment alleviates established vasomotor dysfunction in aged or atherosclerotic mice. Aging Cell 15, 973–977 (2016).

Zhu, Y. et al. New agents that target senescent cells: the flavone, fisetin, and the BCL-X(L) inhibitors, A1331852 and A1155463. Aging (Albany NY) 9, 955–963 (2017).

Todorova, P. K. et al. Radiation-induced DNA damage cooperates with heterozygosity of TP53 and PTEN to generate high-grade gliomas. Cancer Res. 79, 3749–3761 (2019).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 16, 284–287 (2012).

The Gene Ontology Consortium The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D330–D338 (2018).

Liberzon, A. et al. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 1, 417–425 (2015).

Hao, Y. et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573–3587.e3529 (2021).

Stuart, T. et al. Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e1821 (2019).

Badia-i-Mompel, P. et al. decoupleR: ensemble of computational methods to infer biological activities from omics data. Bioinformatics Advances 2 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/bioadv/vbac016.

Müller-Dott, S. et al. Expanding the coverage of regulons from high-confidence prior knowledge for accurate estimation of transcription factor activities. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 10934–10949 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by grants from NASA 80NSSC20K0732 (SB) and NIH R01 CA246807 (SB), R01 AG069819 (PDR), P01 AG043376 (PDR), U19 AG056278 (PDR), P01 AG062413 (PDR, JLK, NKL), U54 AG079754 (PDR), U54 AG076041 (PDR), R37AG013925 (JLK), R33AG061456 (JLK) and T32AG029796 (LEP). We are grateful to Dr. Peter Guida and the support staff at the Brookhaven National Laboratory for help with the irradiations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed experiments: Louise E. Pitcher, Bipasha Mukherjee, Tamar Pirtskhalava, Amyn A. Habib, Tamara Tchkonia, James L. Kirkland, Sandeep Burma and Paul D. Robbins. Preformed the experiments: Louise E. Pitcher, Bipasha Mukherjee, Ashley M. Saathoff, Zachary A. Eduvas, and Sandeep Burma. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: Bipasha Mukherjee, Josh Bartz, Xu Zhang, Nino Giorgadze, James L. Kirkland, Xiao Dong, Nathan K. LeBrasseur, Sandeep Burma, and Paul D. Robbins.Wrote and edited the paper: Louise E. Pitcher, Bipasha Mukherjee, Xu Zhang, James L. Kirkland, Sandeep Burma and Paul D. Robbins.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.T. and J.L.K. have a financial interest related to this research, including patents and pending patents covering senolytic drugs and their uses held by Mayo Clinic. This research has been reviewed by the Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest Review Board and was conducted in compliance with Mayo Clinic and Cedars-Sinai conflict of interest policies. P.R. is a co-founder of Itasca Therapeutics and has filed multiple patents on senotherapeutics held by the University of Minnesota.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pitcher, L.E., Mukherjee, B., Saathoff, A.M. et al. Space radiation induces distinct senescent phenotypes: Implications for space travel. npj Aging 11, 95 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00272-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00272-7