Abstract

Dietary restrictions like alternate-day fasting (ADF) can counteract several age-related disorders, but its role in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is still controversial. Recent findings highlight the imbalances in the gut-brain axis in PD, herein, we aim to study whether ADF can confer protection in PD mice through the gut-brain axis. Firstly, we assessed the neuroprotective effect of ADF in a time-dependent manner and found that 16 -week ADF could confer the optimal neuroprotection by preserving dopaminergic neurons and reducing the level of α‑synuclein (α‑syn) in the substantia nigra (SN), and it could decrease inflammatory cytokine levels in both the brain and the gut. Furthermore, ADF reshaped gut microbial composition and altered metabolites associated with PD. Relative abundances of several intestinal flora, including Alistipes, Helicobacter and Lactobacillus, were identified as potential mediators. In addition, we conducted fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) to further investigate the role of the gut-brain axis in the neuroprotective effects of ADF. Notably, we found that FMT from ADF mice conferred equal protection to ADF in ameliorating the pathology and inflammation in both the brain and the gut. Collectively, our findings suggest that the microbiota-gut-brain axis is crucial to the neuroprotective effect of ADF in PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

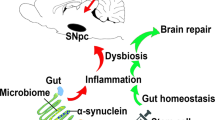

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurological disorder with varying incidence rates depending on age. In the general population, the disorder affects ~14 out of every 100,000 individuals each year. Among those aged above 65, the incidence increases to 160 cases per 100,0001,2. Moreover, PD is typically featured by movement symptoms, including rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability3,4, which are related to dopaminergic neuron degeneration5. Recent studies have highlighted a bidirectional relationship between the brain and the gut. To be specific, the central nervous system(CNS) regulates numerous gastrointestinal functions, such as intestinal muscle motility, the rate of intestinal transit, secretion of digestive substances, and the permeability of the intestinal barrier6; and conversely, bioactive compounds produced from the gut, such as signaling molecules, hormones, and peptides, can influence the CNS functions7,8. The bidirectional interaction between the gut and the brain has been linked to several neurological disorders including PD9,10. Moreover, an increasing number of clinical studies indicated the non-motor symptoms of PD, such as constipation and hyposmia, due to the autonomic system dysfunction often precede the motor symptoms in PD patients11,12,13, which are highly related to the alterations in gut microbiota12,14,15, suggesting that the gut-brain axis has emergingly been a potential therapeutic target in PD.

Neuroinflammation is an important mechanism mediating the onset and progression of nervous system diseases including PD, autism, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis16,17,18,19,20. The nucleotide-binding domain (NBD), leucine-rich repeat (LRR), and pyrin domain (PYD)-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is a critical mediator in neuroinflammation21,22. Its typical markers include NLRP3, caspase1, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), IL-18 and IL-1β21. The NLRP3 and ASC levels are elevated in the midbrain of PD patients23,24. Both α-synuclein (α-syn) fibrils and dopaminergic neuron degeneration can activate the microglial NLRP3 inflammasome24. The activated inflammasome recruits the adapter protein ASC and the inflammatory protease caspase-1 to form the NLRP3 inflammasome complex, which subsequently promotes the release of IL-1β and IL-1821,25,26, thereby triggering an inflammatory response. The microglial NLRP3 could be a sustained source of neuroinflammation and exacerbating PD pathology. Imbalances of gut microbiota can trigger inflammation both in the gut and the brain through the gut-brain axis27. Affected by diet and age, gut microbiota-induced mucosal immune dysregulation results in excessive intestinal inflammation. This typically occurs at the intestinal barrier (IB), leading to an inflammatory or “leaky” IB28,29. Subsequently, pro-inflammatory molecules and cytokines pass through the damaged barrier, entering circulation and triggering systemic inflammation, thus leading to the blood-brain barrier (BBB) damaged30. Ultimately, this allows pro-inflammatory products and cytokines to penetrate the CNS, inducing inflammation and neurodegeneration. One recent study by Mao et al. further revealed that the metabolites of gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), could activate G protein-coupled receptor (GPR)43-NLRP3 pathway and exacerbate α-syn pathology and neuroinflammation31, intensifying the role of gut-brain axis in neuroinflammation.

Dietary restriction (DR) refers to reducing food consumption but not leading to malnutrition. Its beneficial effects in anti-aging and a range of neurodegenerative diseases are being increasingly acknowledged32,33,34,35. Alternate-day fasting (ADF), characterized by strict 24 h periods of no food intake alternating with 24 h intervals of ad libitum (AL) food intake, could demonstrate a positive effect in numerous CNS disorders like Alzheimer’s Disease(AD)36, ischemic stroke37,38, and multiple sclerosis (MS)39. However, there are also studies reporting opposite findings on ADF. Lazic et al. found that ADF for 4 months not only induced microglial activation but also led to a reduction in synaptic plasticity as well as exacerbated neuronal injury in AD mice40. In terms of PD, Choi et al. recently revealed that ADF for 2 weeks could attenuate dopaminergic neuron degeneration in PD mice41. Yet Aquilano et al. reported that ADF for 4 weeks could worsen dopaminergic neuron degeneration when combined with rotenone treatment42. Whether ADF with prolonged duration prior to the neurotoxin-mediated neuropathology could alleviate or worsen the PD symptoms remains elusive, and whether such diet-mediated effect is achieved through the gut-brain axis is also a question to be answered.

The current study revealed that ADF with prolonged duration could alleviate motor dysfunction, neuropathology as well as inflammation in both the brain and gut in PD mice. Exceptionally, ADF modulated gut microbiota composition and alleviated metabolic dysregulation in PD. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from ADF mice could exert similar effects as ADF, including alleviating dopaminergic neuron degeneration, reducing pathological α-syn accumulation, maintaining intestinal mucosal integrity, and suppressing inflammation in both the gut and brain. Moreover, several key gut microbiotas like Alistipes were identified to mediate the protective effect of ADF. These findings suggest that the gut-brain axis is vital to the protective effect of ADF in PD, linking suppressed gut inflammation and improved brain pathology. Taken together, our findings highlight the potential of DR in PD prevention and treatment.

Results

Prolonged ADF showed optimal neuroprotection in PD mice

The time-dependent effect of ADF on mice injected with MPTP was studied using behavioral tests and western blot (WB). The detailed timeline was shown in Fig. 1a. Data from the behavioral tests revealed that the distance moved by mice in the MPTP + AL group was shorter than that of mice in the normal saline (NS) + AL group and mice in the MPTP + ADF groups exhibited a longer total distance moved compared with MPTP + AL group; whereas no statistical difference was observed in the time in center among these groups(Fig.1b–d). In addition, MPTP + AL group showed a shorter time on the rotating rod in rotarod test and a longer moving time in the pole compared with NS + AL group, indicating motor dysfunction; whereas MPTP + ADF groups showed marked enhancement in motor performance during both the rotarod and pole tests compared with MPTP + AL group (Fig.1e, f), suggesting that ADF could alleviate behavioral dysfunction induced by PD. The survival of dopaminergic neurons was analyzed with WB by assessing TH expression, a key marker for dopaminergic neurons. WB analysis of the substantia nigra (SN) samples revealed an 81.52% reduction in TH levels in the MPTP + AL group compared to the NS + AL group, and both ADF-MT (mid-term: 13 weeks) group and ADF-LT (long-term: 16 weeks43,44) group showed alleviated reduction in TH, with the ADF-LT group showing a more considerable protection by 38.20% in comparison to the MPTP + AL group (Fig. 1g, h). Taken together, ADF exerted neuroprotection in a time-dependent manner, and prolonged ADF for 16 weeks showed the optimal neuroprotective effect in PD mice. ADF for 16 weeks was carried out for the subsequent study.

a The timeline of ADF, MPTP injection, behavior tests, fecal samples collection and sacrifice of mice. b Movement locus of the open field test; the yellow parts represent the center area. c Statistical graph of total distance of motion(n = 6). NS + AL versus MPTP+AL: p = 0.007; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF-ST: p = 0.018; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-MT: p = 0.023; MPTP+AL versus MPTP + ADF-LT: p = 0.017. d Statistical graph of total time spent in the center area(n = 6). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p = 0.880; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-ST: p = 0.910; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-MT: p = 0.740; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-LT: p = 0.980. e Statistical graph of latency period in the rotarod test(n = 6). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-ST: p = 0.040; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF-MT: p = 0.020; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-LT: p = 0.007. f Statistical graph of latency period in the pole test(n = 6). NS+AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0. 001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-ST: p = 0.019; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-MT: p = 0.019; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-LT: p = 0.023. g Representative western blot of TH in the SN. h The statistical graph of TH in the SN. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0. 001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-ST: p = 0.979; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-MT: p = 0.009; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF-LT: p < 0. 001. Relative optical density was normalized to GAPDH(n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.02, ***p < 0.001.

ADF altered metabolic pattern and improved motor dysfunction in PD mice

Mice’s body weight was noted two consecutive days a week until MPTP treatment (at the 14th week). The average body weight over the two consecutive days was recorded once a week. Also, the body weight was recorded daily after MPTP modeling until the samples were taken. Prior to MPTP injection, the weight gain of mice fed ADF was slower than that fed AL and the body weight remained lower (Fig. 2a). And from the 2nd day after MPTP injection, mice in the MPTP + AL group began to experience weight loss in comparison with the NS + AL group until the 6th day, after which it increased steadily from the 9th day. Inversely, in the MPTP + ADF group, weight loss appeared from the 2nd day after modeling compared to the NS + ADF group but showed a considerable increase from the 6th day after modeling (Fig. 2b). In terms of the behavioral tests, total movement distance in the open field test and latency period in the rotarod test declined in the MPTP + AL group and picked up substantially by ADF. The pole test also showed that MPTP-induced bradykinesia in MPTP + AL mice was notably relieved by ADF (Fig. 2c–g).

a Comparison of body weight of mice between the AL and ADF groups within 14 weeks prior to MPTP injection(n = 24). b Body weight of mice from the first day of MPTP-injection to the 12th day(n = 12). c Movement locus of the open field test; The yellow parts represent the center area. d Statistical graph of total distance of motion(n = 6). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.030. e Statistical graph of total time spent in the center area(n = 6). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p = 0.130; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF: p = 0.019. f Statistical graph of latency period in the rotarod test (n = 6). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p = 0.003; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.007. g Statistical graph of latency period in the pole test (n = 6). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF: p = 0.028. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.02, ***p < 0.001.

ADF alleviated dopaminergic neuron loss and brain pathology of PD mice

To examine whether ADF could protect dopaminergic neurons and suppress α-syn accumulation, we detected the TH as well as α-syn levels in striatum (STR) and SN by WB, Immunohistochemistry (IHC), and Immunofluorescence (IF). The level of TH in MPTP + AL group was reduced in comparison to NS + AL group, while ADF could reverse the reduction by 20.06% in STR and 16.67% in SN shown in WB (Fig. 3a, b, d, e), and the IHC results showed a parallel trend, demonstrating that ADF was able to prevent dopaminergic neuron loss in PD (Fig. 3g–i). The expression of α-syn was assessed with WB, and the result indicated that α-syn was increased obviously in MPTP + AL group compared with NS + AL group, which was reversed by 81.69% in STR and 123.01% in SN in MPTP + ADF group (Fig. 3a, c, d, f). In addition, IHC staining of α-syn aggregates showed a similar trend (Fig. 3j), suggesting that ADF could not only protect dopaminergic neurons but ameliorate α-syn accumulation in PD mice.

a Representative western blot of TH and α-syn in the STR. b The statistical graph of TH in the STR. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.041. c The statistical graph of α-syn in the STR. NS + AL versus MPTP+AL: p = 0.019; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF: p = 0.031. Relative optical density was normalized to GAPDH (n = 6). d Representative western blot of TH and α-syn in the SN. e The statistical graph of TH in the SN. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0. 001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF: p = 0.007. f The statistical graph of α-syn in the SN. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p = 0.008; MPTP+AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.009. Relative optical density was normalized to GAPDH (n = 6). g Representative IHC staining for TH in the STR and SN. Scale bars = 500 μm (STR and SN) and 100 μm (SNpc). h Statistical graph of the OD value of IHC staining for TH in the STR (n = 4). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF: p = 0.002. i Statistical graph of the number of TH positive cells in the SNpc (n = 4). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.007. j Representative IHC staining for α-syn aggregate in the STR and SN. Scale bars = 50 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.02, ***p < 0.001.

ADF inhibited the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway

To investigate the effect of ADF on MPTP-indued neuroinflammation, we further assessed the expression of proteins associated with the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway in the SN of mice. Animals in MPTP + AL group exhibited a considerable upregulation of NLRP3 and its downstream factors in SN in comparison with NS + AL group. And the MPTP + ADF group performed a marked reduction in these proteins (Fig. 4a–f), demonstrating that ADF inhibited the activation of the NLRP3/caspase1/IL-1β signaling pathway in PD mice. In parallel, the MPTP + AL group showed a considerable increase in Iba1 positive cells in comparison with the NS + AL group, and it was reduced by 44.21% in STR and 53.16% in SN in MPTP + ADF group (Fig. 4g, h). According to the IF staining, activated microglia exhibited amoeba-like morphology with enlarged cell bodies and increased number of cell branches in the MPTP + AL group. These changes were markedly alleviated in the MPTP + ADF group. These results indicated that ADF suppressed neuroinflammation by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

a Representative western blot of NLRP3, caspase1, ASC, IL-18, IL-1β expression in the SN. b The statistical graph of NLRP3 in the SN. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p = 0.377; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF: p = 0.022. c The statistical graph of caspase1 in the SN. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p = 0.014; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.009. d The statistical graph of ASC in the SN. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p = 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.050. e The statistical graph of IL-18 in the SN. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0. 001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF: p < 0.001. f The statistical graph of IL-1β in the SN. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p < 0.001. Relative optical density was normalized to GAPDH (n = 6). g The statistical graph of IHC staining of Iba1 positive cells in STR (n = 4). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p < 0.001. h The statistical graph of IF staining of Iba1+ cells in SN (n = 4).NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.007. i Representative IHC staining of Iba1 positive cells in STR. Scale bars = 100 μm. j Representative IF double staining of Iba1 positive cells (red) and TH positive cells (green) in the SN. Scale bars = 100 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.02, ***p < 0.001.

ADF alleviated intestinal inflammation and protected intestinal mucosal integrity in PD mice

To assess mucosal integrity of enteric canal, IF was applied to detect ZO-1 and Occludin expression. To detect the effect of ADF on gut inflammation, WB was used to assess IL-18 and IL-β protein levels in intestinal tissues. We also conducted IHC staining of IL-1β and HE staining. WB analysis revealed a marked increase in IL-18 and IL-1β levels in MPTP + AL group compared to the NS + AL group, whereas ADF could reverse the trend (Fig. 5a–c). Furthermore, IF staining showed decreased ZO-1 and Occludin expression in the MPTP + AL group compared to that in the NS + AL group, which were elevated after ADF(Fig. 5d–f). The IHC staining of IL-1β showed a similar trend to the WB result (Fig. 5d). HE staining showed that the intestinal mucosa of the NS + AL group was normal, with intact villi and epithelium; in contrast, the MPTP + AL group exhibited disordered intestinal morphology, with damaged villi and separation of the villous epithelium from the submucosa. However, the MPTP + ADF group showed more intact villous structures than the MPTP + AL group, with no significant separation between the lamina propria and the submucosa (Fig. 5d). Above all, ADF was able to protect the intestinal mucosal integrity and suppress intestinal inflammation in PD.

a Representative western blot of Occludin, IL-18 and IL-1β of gut. b The statistical graph of Occludin in the gut. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF: p = 0.003. c The statistical graph of IL-18 in the gut. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.044. d The statistical graph of IL-1β in the gut. NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p = 0.042; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.036. Relative optical density was normalized to GAPDH(n = 6). e Representative IF staining of ZO-1(green) and Occludin(green), IHC staining of IL-1β and HE staining of gut. Scale bars = 100 μm (IF staining) and 200 μm (IHC and HE staining). f The statistical graph of mean fluorescence intensity of ZO-1(n = 4). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p = 0.018; MPTP + AL versus MPTP + ADF: p = 0.039. g The statistical graph of mean fluorescence intensity of Occludin (n = 4). NS + AL versus MPTP + AL: p < 0.001; MPTP + AL versus MPTP+ADF: p = 0.032. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.02, ***p < 0.001.

ADF reshaped the gut microbiota structure

To explore whether ADF could confer protection in PD by regulating the structure of the microbiome community, we performed gut microbiota analysis by metagenomic sequencing to evaluate the gut microbiota composition. We first compared α-diversity between the four groups to assess differences in fecal microbial community structure using Shannon index as well as Simpson index, and found that it was higher in the MPTP + AL group than the NS + AL group, though no remarkable variation between MPTP + AL group and MPTP + ADF group was observed (Fig. 6a, b). Meanwhile, analysis of the gut microbial community structure was performed using PCA and PCoA analysis. The results showed that there was partial overlap in the gut microbiota of mice in NS + ADF group and MPTP + ADF group, indicating that fasting can induce certain specific changes in the structure of gut microbiota (Fig. 6c, d). Subsequently, a LEfSe analysis was conducted to visualize the findings. Notably, pathogens or opportunistic pathogens, such as Helicobacter45 and Desulfovibrionia46, were increased in the MPTP + AL group mice. By contrast, ADF led to the enrichment of Alistipes and Lactobacillus, which were less abundant in fecal samples in PD patients47,48(Fig. 6e, f). ADF ameliorated the gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by MPTP and enriched beneficial bacteria. Subsequently, we assessed microbial physiological functions at the genus level. Using KEGG annotation and functional enrichment, Fig. 6g demonstrated that bacteria involved in metabolic functions have the highest abundance in the gut microbiota (Fig. 6g). In the heatmap shown in Fig. 6h, it was evident that the abundance of bacteria associated with neurodegenerative and viral infectious diseases was decreased in MPTP + AL group, while there was a marked decrease in the MPTP + ADF group, similar to the two groups injected with saline. Meanwhile, bacteria related to metabolism and environmental adaptation were less in the MPTP + AL group, indicating that MPTP led to metabolic disturbance in PD mice; in contrast, the bacteria in the MPTP + ADF group exhibited greater involvement in these two functions (Fig. 6h). Overall, MPTP led to metabolic disturbance, which could be partially restored by ADF.

a, b Represent α-diversity index. c PCA plot result. d PCoA plot result. e The top 35 genera in abundance and their abundance in each sample. f LEfSe analysis of species with abundance at the genus level and their expression in each group. g Number of annotated genes in gut microbiome. h Functional abundance clustering heat map based on KEGG database.

ADF partially reversed the alteration of gut metabolome induced by MPTP

The KEGG functional pathway analysis of fecal metagenomic sequencing described above indicated alterations in the gut metabolome. Analysis of untargeted metabolomics aimed at investigating the metabolomic profiles of PD mice fed AL or ADF was further performed. Firstly, statistical analysis of the identified metabolites in this study revealed that lipid-related compounds were the most abundant, followed by organic acids and derivatives (Fig. 7a). Furthermore, a KEGG pathway analysis of the identified metabolites showed considerable functional enrichment in metabolism of many substances including amino acid, vitamins, lipid and nucleotide, etc (Fig. 7b), indicating that the change of biochemical metabolism regulated by gut microbiota metabolites may be involved in ADF-mediated neuroprotection against PD. At last, several representative metabolites with considerable differences are displayed in Fig. 7c. MPTP apparently led to an increase in testosterone undecanoate, andrographolide, norbutorphanol, etc., and ADF could alleviate this phenomenon. In the meanwhile, metabolites like cholecalciferol were decreased by MPTP and reversed by ADF (Fig. 7c).

a Chemical classification of metabolites. b KEGG analysis of gut microbiome metabolite. c Representative histogram of differential metabolite changes. d Correlation analysis between gut microbiota and metabolites between MPTP + AL and NS + AL groups. e Correlation analysis between gut microbiota and metabolites between MPTP + ADF and MPTP + AL groups.

Changes in fecal metabolite are closely correlated with microbiota variations

To identify the relationship between microbiota and metabolism in stool, we conducted correlation analysis with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Taking the correlation analysis result of differential microbiota and differential metabolites between the MPTP + AL and NS + AL groups as an example, the decrease of Akkermansia induced by MPTP was positively correlated with tocopherol, while it was negatively correlated with cyclopentyl fentanyl. Furthermore, the correlation analysis between differential gut microbiota and metabolites in the MPTP + AL and MPTP + ADF groups revealed that Rothia was negatively correlated with the levels of 2-arachidonoyl glycerol and tyramine, while it was positively correlated with the level of oxaceprol. A more detailed analysis of the associations between differential gut microbiota and metabolites is presented in Fig. 7d, e. Above all, the fecal microbiome was closely correlated with its metabolites.

FMT partially improved behavioral dysfunction of PD mice

To evaluate whether gut microbiota from MPTP + AL group could impair motor function and whether gut microbiota from MPTP + ADF group could confer neuroprotection, we further conducted FMT. The group design and timeline of FMT was shown in Fig. 8a, b. Briefly, mice were divided into two groups: an MPTP-injected PD group and an NS-injected control group. Based on this, mice were given one of three gavage treatments in each group: sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS), FMT from MPTP + AL mice, and FMT from MPTP + ADF mice, yielding a total of six experimental groups: NS + PBS, NS + MPTP-AL, NS + MPTP-ADF, MPTP + PBS, MPTP + MPTP-AL, MPTP + MPTP-ADF. The total movement distance and the time in center area of the open field test and the latency period in the rotarod test were declined in MPTP + PBS group, and in MPTP + MPTP-ADF group, these behavioral tests were improved. The latency time in pole test was lengthened in the MPTP + PBS group and was declined in MPTP + MPTP-ADF group, though it did not reach a statistical difference, which might be attributed to the experiment’s sensitivity to human intervention and the limited time span. The results indicated that FMT of ADF gut microbiota was able to partially alleviate behavioral dysfunction of PD mice (Fig. 8d–g).

a Detailed schematic illustration of FMT: The fecal suspensions prepared from the MPTP + AL group and MPTP + ADF group mice, as well as sterile PBS solution, were administered orally to the control mice and MPTP-induced PD mice, respectively. b The timeline of FMT, MPTP injection, behavioral tests and sacrifice of mice. c Representative images of the open field test; The yellow parts represent the center area. d Statistical graph of total distance of motion (n = 6). NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p < 0.001. e Statistical graph of total time spent in the center area(n = 6). NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p = 0.010. f Statistical graph of latency period in the rotarod test (n = 6). NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p < 0.001. g Statistical graph of latency period in the pole test(n = 6). NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p = 0.237. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.02, ***p < 0.001.

FMT alleviated dopaminergic neuron loss, neuroinflammation and brain pathology induced by PD

To evaluate the effect of FMT on PD, TH, α-syn and Iba1 in brain were detected by WB, IHC and IF. In MPTP + PBS group, TH expression was downregulated compared with NS + PBS group while MPTP + MPTP-ADF group could reverse the reduction (Fig. 9a, b, d, e, f). Moreover, the expression of α-syn and its aggregate in MPTP + PBS group increased notably compared with NS + PBS groups. Though the decrease of α-syn detected by WB was not statistically significant (Fig. 9a, c), the aggregates of α-syn detected by IHC staining reduced in MPTP + MPTP-ADF group compared with MPTP + PBS group (Fig. 9g). Similarly, number of Iba1 positive cells increased obviously both in STR and SN in IHC and IF staining in MPTP + PBS group and decreased in MPTP + MPTP-ADF group (Fig. 9h–k). MPTP-induced activated morphology of microglia was also reversed in the MPTP + MPTP-ADF group (Fig. 9k). These results demonstrated that the neuroprotective effect of ADF could be partially achieved through FMT by inhibiting pathological α-syn aggregation and microglia activation.

a Representative western blot of TH and α-syn in the SN. b The statistical graph of TH in the SN. NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p = 0.004. c The statistical graph of α-syn in the SN. NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p = 0.010; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p = 0.990. Relative optical density was normalized to GAPDH (n = 6). d Representative IHC staining for TH in the STR and SN. Scale bars = 500 μm (STR and SN) and 100 μm (SNpc). e Statistical graph of the OD value of IHC staining for TH in the STR(n = 6). NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP+MPTP-ADF: p=0.020. (f) Statistical graph of the number of TH positive cells in the SNpc (n=6). NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP+PBS versus MPTP+MPTP-ADF: p = 0.020. g Representative IHC staining for α-syn aggregate in the STR and SN. Scale bars = 50 μm. h Representative IHC staining of Iba1 positive cells in STR. Scale bars = 100 μm. i The statistical graph of IHC staining of Iba1 positive cells in STR(n = 6). NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p < 0.001. j The statistical graph of IF staining of Iba1 positive cells in SN(n = 6). NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP+MPTP-ADF: p < 0.001. k Representative IF double staining of Iba1 positive cells (red) and TH positive cells (green) in the SN. Scale bars = 100 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.02, ***p < 0.001.

Effect of FMT on inflammation and pathology in gut

To evaluate the function of FMT on intestinal inflammation and mucosal integrity of enteric canal, we performed WB of Occludin, IF of ZO-1 and Occludin, as well as IHC of IL-1β and HE staining. The results indicated that expression of ZO-1 in MPTP + PBS group was lower than that in NS + PBS group and increased in MPTP + MPTP-ADF group. (Fig. 10d). The level of IL-1β expression in MPTP + MPTP-ADF group was obviously decreased compared to MPTP + PBS group, and the pathologic change also reduced in MPTP + MPTP-ADF group as evidenced by HE staining that the MPTP + MPTP-ADF group showed more intact villous structures compared to MPTP + PBS and MPTP + MPTP-AL group (Fig. 10a). However, the expression of Occludin was decreased in MPTP + PBS group and increased slightly in MPTP + MPTP-ADF group without a statistical difference (Fig. 10b, c, e). These findings suggest that FMT primarily affects the intestinal inflammation in mice, while exerting a relatively limited protective effect on intestinal mucosal integrity.

a Representative IF staining of ZO-1 (green) and Occludin (green), IHC staining of IL-1β and HE staining of gut. Scale bars = 100 μm (IF staining) and 200 μm (IHC and HE staining). b Representative western blot of Occludin. c The statistical graph of Occludin in the gut. NS+PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p = 0.180. Relative optical density was normalized to GAPDH (n = 6). d The statistical graph of mean fluorescence intensity of ZO-1(n = 6). NS + PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p < 0.001; MPTP+PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p = 0.006. e The statistical graph of mean fluorescence intensity of Occludin (n = 6). NS+PBS versus MPTP + PBS: p = 0.003; MPTP + PBS versus MPTP + MPTP-ADF: p = 0.560.

Correlation analysis revealed the protective role of ADF mediated by the gut-brain axis

To better understand the involvement of the gut-brain axis in ADF-mediated protection against PD, we conducted correlation analyses between selected top 10 abundant genera and key protein expression in the brain and gut of PD mice. Additionally, correlations between brain and gut indicators were also analyzed. The results showed that the abundance of Alistipes was positively correlated with TH levels in the STR of mice and negatively correlated with the expression levels of IL-18 and IL-1β in the SN of mice, though the correlation between Alistipes and IL-1β did not reach a statistical difference (Fig. 11a–c). In contrast, the abundance of Helicobacter showed the exact opposite (Fig. 11d–f). Additionally, the IL-18 and IL-1β levels in the gut were negatively correlated with TH expression in the STR and positively correlated with IL-1β and IL-18 levels in the SN (Fig. 11g–l). A more comprehensive description of the correlations is presented in (Fig. 11m).

a Correlation between relative abundance of Alistipes and TH level in STR of mice. p = 0.0181, r = 0.6857. b Correlation between relative abundance of Alistipes and IL-18 level in SN of mice. p = 0.0449, r = −0.5822. c Correlation between relative abundance of Alistipes and IL-1β level in SN of mice. p = 0.0620, r = −0.5393. d Correlation between relative abundance of Helicobacter and TH level in STR of mice. p = 0.0019, r = −0.7474. e Correlation between relative abundance of Helicobacter and IL-18 level in SN of mice. p = 0.113, r = 0.4701. f Correlation between relative abundance of Helicobacter and IL-1β level in SN of mice. p = 0.0170, r = 0.5679. g Correlation between IL-18 level in gut and TH level in STR of mice. p = 0.0008, r = −0.8632. h Correlation between IL-18 level in gut and IL-18 level in SN of mice. p = 0.0002, r = 0.7243. i Correlation between IL-18 level in gut and IL-1β level in SN of mice. p = 0.0003, r = 0.7604. j Correlation between IL-1β level in gut and TH level in STR of mice. P=0.0449, r=0.-0.4271. k Correlation between IL-1β level in gut and IL-18 level in SN of mice. P=0.0098, r=0.4385. l Correlation between IL-1β level in gut and IL-1β level in SN of mice. P=0.0064, r=0.3708. (m) Correlation between the abundance of the Akkermansia, Helicobacter, Alistipes, Parabacteroides, Lactobacillus and TH level in STR, α-syn level in STR, IL-1β level in SN, IL-18 level in SN, IL-1β level in gut, IL-18 level in gut, NLRP3 level in SN, caspase1 level in SN of mice. The red lines represent a positive correlation, and the blue lines represent a negative correlation; The solid lines represent p<0.05, while the dashed lines represent p>0.05.

Discussion

Numerous studies have illustrated the merits of DR on health49,50,51. These benefits were initially validated through observations of prolonged longevity in rats fed indigestible cellulose35. Later studies revealed that dietary interventions can improve brain metabolism and exert a beneficial effect in anti-aging and a number of aging-related neurodegenerative diseases32,41,51,52,53,54. But there are still controversies regarding the neuroprotective effect of ADF in PD42. Moreover, the molecular mechanism of ADF against PD progression needs further to be elucidated. Therefore, we evaluated the time-dependent effect of ADF in a subacute PD model, and studied its underlying mechanism, specifically, regarding the gut-brain axis regulation.

Despite that the conventional pathological features of PD mainly involve the loss of TH neurons and accumulation of pathological α-syn in the brain, emerging evidence in recent years suggests that PD may originate from the gut52,55,56. Moreover, PD patients experience higher levels of α-syn and NLRP3 in intestinal tissue than healthy controls57. Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation could impair dopaminergic neurons and induce motor deficits in PD58, and several studies reported a relation between NLRP3 activation and α-syn formation as well as PD progression59,60,61. Both monomeric and aggregated α-syn proteins activate NLRP3 inflammasome via TLR2 and TLR5 ligation, while suppression of NLRP3 decreases the levels of α‑syn61,22, revealing the interaction relationship between the α-syn and NLRP3. Likewise, the gut microbiome could regulate brain functions via NLRP3 signaling62, this may be attributed to specific bacterial metabolites such as SCFAs, vitamins, or neurotransmitters entering the bloodstream and ascending to the brain, thereby modulating CNS microglial activity63,64. For example, Indole-3-carboxaldehyde derived from Lactobacillus reuteri can bind to aryl hydrocarbon receptors (AhR) in the hippocampus, and alleviate mice’s susceptibility to stress via the AhR/SOCS2/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway65. In addition, several studies have investigated that SCFAs, including alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) and propionate, may inhibit the activation of the NLRP3 signaling pathway through interactions with GPRs, particularly GPR100 and GPR4366,67,68,69. Moreover, bacterial metabolites can directly activate immune cells in the bloodstream, which subsequently migrate to the CNS and modulate brain physiology62. A recent study by Chang et al. demonstrated that brain injury after cardiac arrest/cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CA/CPR) is associated with increased release of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from intestinal Enterobacter, which activates TREM1 on macrophages and subsequently leads to the migration of gut-derived macrophages into the brain70. In addition, in human subjects, NLRP3 inflammasome activation decreases during fasting than that in the refed period71. Herein, we established a subacute PD mouse model to induce microbiota dysbiosis by administering MPTP injections72,73. We found that ADF alleviated MPTP-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis and intestinal metabolic imbalance, and attenuated microglial activation and intestinal inflammation caused by MPTP. Furthermore, FMT experiments demonstrated that the gut microbiota from the MPTP + AL group induced inflammation in both the brain and gut of recipient mice, whereas the microbiota from MPTP + ADF mice suppressed these inflammatory responses. These results suggest that the protective effects of ADF against MPTP-induced neuroinflammation and intestinal inflammation are closely related to the modulation of gut microbiota and its metabolites.

Common animal models of PD include those induced by neurotoxins such as rotenone74,75, paraquat76,77, 6-hydroxydopamine78,79, and MPTP80,81, which can lead to dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the brain. Although these toxin-based models have played a crucial role in exploring key mechanisms and evaluating novel treatments underlying PD, they do not fully recapitulate the complex symptomatology of human PD82,83. Nonhuman primates have a greater advantage than rodents because of their similar genetic background and brain structure with humans. However, primate models, such as the MPTP-induced monkey models, have issues of unstable symptoms, poor health conditions and high costs, and thus limiting their wide use. For several decades, the MPTP-induced mouse model has been one of the most widely used models in PD research due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and greater clinical relevance, such as motor impairments, neuropathological changes, and gastrointestinal symptoms72,82,84,85,86. The current study selected the MPTP-induced subacute model because of its significant advantages over other models in causing intestinal flora disorders and inducing α-syn accumulation, as well as saving time80,81,87. As shown in the current study, the MPTP-induced PD mice lost weight and dyskinesia (indicated by the open field tests, pole tests, and rotarod tests) compared to the NS-injected group. Additionally, analysis of SN and STR tissues revealed that MPTP induced the destruction of TH-positive cells and increased α-syn of monomers and aggregates in the SN, which was consistent with previous studies86,88,89. Apart from this, analysis of brain and gut tissues suggested activated NLRP3 inflammasome in STR and SN as well as enhanced inflammation and damage to intestinal mucosal integrity in gut caused by MPTP. All these pathological alterations could be alleviated by ADF, and the most pronounced effect was observed in the LT- ADF group. As mentioned earlier, intestinal inflammation regulated by gut microbiota may propagate such effects to the brain, ultimately leading to CNS inflammation28,29,30. Besides, numerous studies have confirmed that α-syn, the main composition of the Lewy body, could originate in the gut and reach the brain using the vagal nerve as a communication pathway90,91,92. PD models induced by duodenal or gastric α-syn preformed fibrils (PFFs) inoculation can simulate such process93,94,95, strongly indicating that PD may originate in the intestine92. In our study, we observed that ADF not only improved neuroinflammation and neuropathology in PD, but also alleviated intestinal inflammation and protected intestinal integrity.

The microbiota-gut-brain axis describes an intricate system linking various biological processes, allowing mutual signaling between the gut microbiome and the brain. This axis is essential for sustaining the stability of digestive, neurological, and microbial systems in animals96. FMT was able to ameliorate the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases74,97. For example, FMT from wild-type mice to APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice, an animal model of AD, could improve cognitive disturbance and decrease brain amyloid-β deposition. Additionally, FMT treatment could alter SCFAs from gut microbiome98. In our study, ADF could alter the disordered microbial composition in PD mice. PD mice that received intestinal microbiota orally from the MPTP + ADF group for FMT treatment showed an alleviation in brain pathology compared to PD mice receiving PBS, presenting more preserved TH-positive neurons, reduced α-syn level, and decreased Iba1-positive cells in STR and SN. Similarly, a previous work by Zhong et al. revealed that PD mice treated with FMT from healthy mice showed lower α-syn expression99. Herein, we further revealed a beneficial effect of FMT from PD model under ADF treatment. We found that FMT from the MPTP + ADF group could partially ameliorate the motor dysfunction in PD mice and exert protective effects similar to ADF in the respect of alleviating brain pathology and neuroinflammation, suggesting that the neuroprotective effects of ADF are partially achieved through the modulation of the gut-brain axis. The failure of ADF to preserve the intestinal integrity could be attributed to the different microbial populations, such as Lactobacillus, in the gut microbiota of MPTP + AL group and MPTP + ADF group, are primarily associated with anti-inflammatory effects100,101,102,103. For example, Zhang et al. reported that baicalin attenuated Escherichia coli-induced intestinal inflammation by increasing the abundance of Lactobacillus amylovorus in the gut, while exerting a relatively weak effect on the intestinal tight junction protein Occludin104.

A number of research has exhibited aberrant microbial community structures in PD. PD patients present obvious alterations in the α-diversity and/or β-diversity of gut microbiome105,106,107. Apart from that, increased mucin-degrading Akkermansia and reduced SCFAs-producing Roseburia and Faecalibacterium, which contribute to more intact intestinal permeability, were observed in PD individuals108,109. Animal studies also revealed altered gut microbiome in PD mice72,86,110. In our study, α-diversity of the gut microbiota of PD mice was higher in comparison of the NS + AL group, parallel to the findings in PD and stroke52,75,87,111,112. But some research suggested that PD patients had a lower diversity index74,113,114 or even no significant differences compared to the healthy controls110. We suppose that such variations may be due to the individual differences in the host and feces collection at different disease stages. Gut microbiota structure of fecal samples changed in PD mice compared to the controls, with increased Helicobacter, Desulfovibrionia, Palleniella genus, and decreased Alistipes and Duncaniell genus. Helicobacter could lead to chronic mucosal inflammation and persistent infection if the patient does not receive eradication therapy115. Consistent with our findings, PD patients had a greater popularity of Helicobacter infection compared with the general population116. Helicobacter could promote the development of PD in two main ways: on one hand, its autotoxin induces the pro-inflammatory factors releasing, thereby promoting central inflammation; on the other hand, it breaks the balance within the gut microbiota, which subsequently influences the CNS via the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Importantly, Helicobacter had been found to cause gastric dysmotility, leading to a longer transit time of levodopa to gut, and it could utilize levodopa to promote its own growth and proliferation, causing destruction to the gastrointestinal mucosa and hindering the absorption of levodopa45. Desulfovibrionia is a type of sulfate-reducing bacteria, which is present in about 50% of individuals, residing in both the oral cavity and the gastrointestinal system117,118. SRB proliferates in the intestines, releasing hydrogen sulfide as a byproduct of sulfate loss, an effective genotoxin associated with chronic colonic diseases and colitis inflammation119. Furthermore, these bacteria are involved in the onset or persistence of inflammatory chronic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and periodontitis120. Mounting studies have revealed that PD progression and gut inflammation are closely related30,87. A clinical study showed increased inflammatory factors in the biopsies of ascending colon among PD patients, which is related to the disease course121. Altered gut microbiota like Desulfovibrionia may mediate the gut inflammation and brain pathology in PD. To be noted, except for Helicobacter and Desulfovibrionia, the genus Palleniella was revealed to be relevant to PD for the first time, which was increased notably in MPTP + AL group, but its underlying mechanism requires further research. In the current study, we further analyzed the correlations between abundance of gut microbiota at the genus level and PD neuronal markers, as well as inflammatory markers in the brain and gut. Certain intestinal flora like Alistipes and Parabacteroide were not only correlated with PD neuronal markers and brain inflammation levels but also with gut inflammation. Interestingly, gut inflammation levels were also correlated with specific PD neuronal markers and brain inflammation. The gut microbiota analysis and untargeted metabolomics data from our study support the concept of certain specific gut microbiome, such as Desulfovibrionia, and metabolites, such as α-cyclodextrin, as potential biomarkers for PD diagnosis. These findings also indicate that the microbiota-gut-brain axis mediates the protective effects of ADF in PD.

Additionally, notable reductions in the gut metabolism were observed in PD mice, including metabolism of vitamins and amino acids, as well as lipids and nucleotides according to the KEGG analysis. Furthermore, these changes were alleviated by ADF. Numerous studies suggested that the gut microbiota metabolites played a crucial role in the development of neurological disorders52,56,111,122. For example, ferroptosis inhibitors like tocopherol, which could interrupt the lipid peroxidation cascade, have the potential to treat PD and AD and other brain diseases123. Besides, Akkermansia could inhibit the reduction of dopaminergic neurons and alleviate neuroinflammation in the SN of PD mice124. According to our correlation analysis of gut microbiota and gut metabolism, tocopherol and Akkermansia were positively correlated, which indicates that the neuroprotective role of ADF via the microbiota-gut-brain axis may be achieved by altering the microbial metabolites. In addition, untargeted metabolomic analysis showed an increase of testosterone undecanoate, andrographolide, norbutorphanol, N-acetyl sphingosine and α-cyclodextrin, etc. in MPTP + AL group, all of which were decreased in MPTP + ADF group; while there was a considerable decrease of cholecalciferol in MPTP + AL group, which increased in MPTP + ADF group, indicating that ADF alleviated the metabolic disturbance caused by PD. Among the metabolites, cholecalciferol treatment has been reported to improve L-dopa-induced dyskinesia by reducing movement abnormalities, modulating oxidative stress, inflammation, and microglial responses of STR but not affecting dopamine metabolism125, suggesting that the gut metabolites are promising treatment or adjunctive methods for PD.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations in this study. Firstly, we only applied MPTP-induced subacute mouse model, which may not fully recapitulate the gut microenvironment observed in PD patients80. Also, this model fails to recapitulate the chronic progressive disease course characteristic of human PD. Gut inoculation of α-syn PFFs is also a valuable animal model for studying the gut–brain axis, as it can mimic the gut-to-brain pathological progression of α-synucleinopathy126,127. Moreover, given the differential sensitivity to neurotoxins between males and females128, as well as the notable sex-specific differences in gut microbiota composition129,130, studies focusing on a single sex may present inherent limitations. Further investigations on different PD models across both sexes are necessary to comprehensively validate these findings. In addition, despite several intestinal flora at genus level and metabolites have been identified to potentially mediate the neuroprotective effect of ADF, further in vivo and in vitro studies on individual bacterial strains and metabolites could help further elucidate the underlying mechanism of ADF.

In conclusion, our study revealed a protective role of ADF in PD mice by alleviating behavioral dysfunction, preserving dopaminergic neurons, reducing α-syn pathology, as well as inhibiting inflammation in both brain and gut. Importantly, ADF alleviated gut microbiota dysbiosis and metabolic disturbance of PD mice, and FMT of MPTP + ADF mice could confer similar neuroprotection against MPTP-induced neurotoxicity, supporting that the effect of ADF could be partially mediated by the microbiota-gut-brain axis. These findings provide a theoretical basis for dietary interventions as promising strategies for PD prevention and treatment.

Methods

Group design

Seven-week-old male C57BL/6 J mice were obtained from Hua Fukang (Beijing, China) and given a week-long adaptation period before experimental interventions began. Animals were housed at 24°C and 55% humidity in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) animal laboratory. Mice had unrestricted access to water, while food was provided AL, or ADF conditions. The experimental protocols received approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of the Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (No. 2023PS133K).

After acclimatization, mice were divided into 5 groups to evaluate the time-dependent effects of ADF on MPTP-induced pathology: NS + AL, MPTP + AL, MPTP + ADF-ST (short-term: 5 weeks131), MPTP + ADF-MT, MPTP + ADF-LT. The NS or MPTP was represented by injecting intraperitoneally with NS or MPTP, and the AL or ADF was represented by being fed AL or ADF. The ADF duration which showed optimal neuroprotective effect was selected for subsequent experiments. Mice were further divided into 4 groups randomly for subsequent experiments: NS + AL, NS + ADF, MPTP + AL, and MPTP + ADF.

To investigate whether the effect of ADF on PD is achieved through gut microbiota, the FMT treatment was applied. Animals were randomly divided into six groups: the NS + PBS group, receiving NS by intraperitoneal injection and PBS via oral gavage; the NS + MPTP-AL group, receiving NS by intraperitoneal injection and microbiota from MPTP + AL mice via oral gavage; the NS + MPTP-ADF group, receiving NS by intraperitoneal injection and microbiota from MPTP + ADF mice via oral gavage; the MPTP + PBS group, receiving MPTP by intraperitoneal injection and PBS via oral gavage; the MPTP + MPTP-AL group, receiving MPTP by intraperitoneal injection and microbiota from MPTP + AL mice via oral gavage; the MPTP + MPTP-ADF group, receiving MPTP by intraperitoneal injection and microbiota from MPTP + ADF mice via oral gavage. Details of the experimental design and the timeline of the FMT part are presented in Fig.8a, b.

MPTP treatment

MPTP is known as a neurotoxin that stimulates the death of TH neurons and the overexpression of α-syn in the mouse brain72,82,84. As male mice are more sensitive to MPTP and are conventionally applied for PD studies88,132, male C57BL/6 J mice were intraperitoneally administered MPTP (M0896, Sigma-Aldrich) at a daily dose of 30 mg/kg for 5 consecutive days to induce a subacute model of PD as described previously84,133,134.

Sample collection

Fecal samples of mice were collected 24 h after the final MPTP injection and continued until the mice were sacrificed. The samples produced by mice in metabolic cages were immediately transferred to −80 °C for preservation. To collect the brain and gut tissues for WB, mice were anesthetized with 1% sodium pentobarbital by intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 50 mg/kg and then were perfused via the apex of the heart using 0.9% NS. After perfusion, the mice died naturally without the need of euthanasia. Tissues collected during this process were quickly frozen and preserved at −80°C. The STR and SN regions of the brain tissue were separately preserved for future analyses. Meanwhile, tissues intended for IHC and IF were soaked in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 2 days.

Behavioral tests

Prior to MPTP administration, each mouse underwent behavioral training identical to the formal testing procedures to adapt to the testing environment. Formal behavioral tests for the ADF and FMT groups were conducted 24 h after the final MPTP injection, as illustrated in Fig. 1a and Fig. 8a.

The open field test was used to evaluate the anxiety and spontaneous movement of mice135. Place the mice at a 50 cm × 50 cm × 40 cm box, let the mice move freely for 10 min, and use computer software (Noldus Ethovision) to record the motion trail of mice as in previous studies136. After each experiment, spray the box with alcohol to eliminate odors.

The rotarod test was used to evaluate the balance and coordination of mice135. Place the black sensing plate at the bottom of the rotarod apparatus in a horizontal position, and place the mice on rotating rods with speeds gradually increasing from 0 to 30 h/min over 5 min136. This project was trained for three consecutive days before being processed with MPTP84. The latency to fall was documented for each mouse. At 5 min, the rotarod automatically stopped rotating. If the mouse still hasn’t fallen, record the time as 5 min

The pole test was used to evaluate the coordination of mice88. This device comprised a 50-cm tall wooden pole topped with a small wooden ball, which was placed vertically. Mice were positioned with their heads downward on the wooden ball and went to the bottom as in previous research80. This project was trained for three consecutive days before being processed with MPTP, with a calculation of time from the animal that was released and ended when the hindlimb reached the home cage base.

Western blot analysis

Remove the STR and SN tissues of brain and intestinal tissues from -80 °C and mix them with ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (RIPA: protein phosphatase inhibitor: PMSF = 100:1:1) and let them stand on ice for 30 min. Following centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 40 min at 4°C, the supernatant was mixed with 5× loading buffer (4:1) and boiled at 100 °C for 10 min. The denatured protein was subjected to electrophoresis for 1 h before transferred to PVDF membranes for the next blocking and was incubated with following antibodies: GAPDH(60004-1-lg, Proteintech), TH (ab137869, Abcam), α-synuclein(D37A6, Cell Signaling Technology), NLRP3 (381207, ZEN-BIOSCIENCE), caspase-1(14F468, Santa Cruz), ASC(sc-271054, Santa Cruz), IL-18 (ab191860, Abcam), IL-1β(12242, Cell Signaling Technology). and secondary antibodies successively, then discarded the secondary antibody, and washed for the next detecting. The tissue from STR was used to detect TH and α-syn; The tissue from SN was used to detect TH, α-syn, NLRP3, caspase1, ASC, IL-18 and IL-1β. The protein from gut was used to detect Occludin, IL-18 and IL-1β.

Immunohistochemistry

The paraffin sections of tissues (4um) were subjected to antigen retrieval after being left overnight in a 65 °C dryer. Sections were then blocked with endogenous peroxidase and serum and incubated with a primary antibody: TH (ab137869, Abcam), Iba1(ab283319, Abcam), IL-1β (12242, Cell Signaling Technology), α-syn aggregate (ab209538, Abcam) and a secondary antibody successively for 30 min after being washed. After being stained with DAB (DAB-0031, MXB biotechnologies) substrate and washed, the sections covering a slide were observed.

Immunofluorescence

The paraffin sections of tissues (4um) were subjected to antigen retrieval after being left overnight in a 65 °C dryer. After blocked, sections were incubated with a primary antibody: Iba1 (ab283319, Abcam), TH (ab137869, Abcam), ZO-1 (21773-1-AP, Proteintech) and Occludin (33-1500, Invitrogen) and a secondary antibody successively. Finally, the sections covering a slide with AntiFade Mounting Medium (ab104139, Abcam) were observed.

Gut microbiota analysis by metagenomic sequencing

The analysis of gut microbiota included sample testing, library construction and sequencing. Using 1% agarose gels to assess the extent of DNA degradation and the possibility of contamination and then measure the DNA concentration with Qubit® dsDNA Assay Kit. For library construction, samples were selected based on OD values within the range of 1.8-2.0 and DNA quantities exceeding 1 µg. Then these samples were fragmented to a size of 350 bp using sonication. The resulting PCR amplifications were purified and quantified.

Untargeted metabolomics

Untargeted fecal metabolomics was conducted using UHPLC-MS/MS. First, 1 ml of fecal samples were freeze-dried and then resuspended in cold methanol and then incubated on ice and centrifuged for 15 min. The product was moved to a clean EP tube and centrifuged again under the same conditions. The LC-MS/MS system was used, and the metabolites with VIP > 1 and P-value < 0.05 were considered to be a statistical difference. Data analysis and statistical evaluations were performed using R and Python software.

Fecal microbiota transplantation

Fresh feces were obtained from mice in MPTP + AL and MPTP + ADF groups. To sum up, fresh fecal pellets were treated or transferred to -80°C immediately for short-term storage and repeated freeze-thawing is strictly avoided. 0.1 g of feces were mixed with 1 mL of NS and then were soaked for 1 min and then centrifuged for 3 min at 4°C. At last, 8 week-old recipient mice were given 100 μL of the fecal bacterial suspension by oral gavage, continuing the procedure for 14 consecutive days74. MPTP injection and behavioral tests were conducted during the final 6 days of the FMT. Specifically, MPTP injection was started on day 9 and continued for five consecutive days, followed by behavioral tests on day 14. Tissue collection was performed on day 15 (Fig. 8b).

Statistical analysis

Except for Metagenomic sequencing of gut microbiota and metabolite identification, the GraphPad Prism 9.0 was conducted for data analysis and histogram. The results were examined by Shapiro-Wilk test to check normality. And one-way ANOVA analysis of variance followed by a Tukey post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. Experimental results were described as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), with n representing the sample size of animals. Significance was identified when the p-value was less than 0.05, with significance levels marked as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.02, ***p < 0.001.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are showed in the following content on the figshare: The gut microbiota analysis by metagenomic sequencing: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26312191; The untargeted metabolomics analysis: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26308873; The correlation analysis of metagenomic sequencing and untargeted metabolomics analysis: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26308756.

References

Kalia, L. V. & Lang, A. E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 386, 896–912 (2015).

Ascherio, A. & Schwarzschild, M. A. The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease: risk factors and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 15, 1257–1272 (2016).

Tolosa, E., Garrido, A., Scholz, S. W. & Poewe, W. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 20, 385–397 (2021).

Reich, S. G. & Savitt, J. M. Parkinson’s disease. Med. Clin. North Am. 103, 337–350 (2019).

Berg, A., Bech, S., Aasly, J., Farrer, M. J. & Skaalum Petersen, M. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: results from the Faroese Parkinson’s disease cohort. Neurosci. Lett. 785, 136789 (2022).

Martin, C. R., Osadchiy, V., Kalani, A. & Mayer, E. A. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 133–148 (2018).

Morais, L. H., Schreiber, H. L. T. & Mazmanian, S. K. The gut microbiota-brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 19, 241–255 (2021).

Urrutia, A. et al. Bacterially produced metabolites protect C. elegans neurons from degeneration. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000638 (2020).

Socała, K. et al. The role of microbiota-gut-brain axis in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharm. Res 172, 105840 (2021).

Kesika, P., Suganthy, N., Sivamaruthi, B. S. & Chaiyasut, C. Role of gut-brain axis, gut microbial composition, and probiotic intervention in Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci. 264, 118627 (2021).

Mu¤oz, A. et al. Caenorhabditis elegans RAC1/ced-10 mutants as a new animal model to study very early stages of Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol 234, 102572 (2024).

Lubomski, M. et al. Parkinson’s disease and the gastrointestinal microbiome. J. Neurol. 267, 2507–2523 (2020).

Mulak, A. & Bonaz, B. Brain-gut-microbiota axis in Parkinson’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 10609–10620 (2015).

Cirstea, M. S. et al. Microbiota composition and metabolism are associated with gut function in parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 35, 1208–1217 (2020).

Sampson, T. R. et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell 167, 1469–1480 e1412 (2016).

Pajares, M. A, I. R., Manda, G., Bosca, L. & Cuadrado, A. Inflammation in Parkinsonas disease: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cells 9, 1687 (2020).

Glass, C. K., Saijo, K., Winner, B., Marchetto, M. C. & Gage, F. H. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell 140, 918–934 (2010).

Tiwari, A. et al. Neuroprotective effect of à-mangostin in ameliorating propionic acid-induced experimental model of autism in wistar rats. Brain Sci 11, 288 (2021).

Kajal, S. et al. Neuroprotective potential of tanshinone-IIA in mitigating propionic acidinduced experimental autism-like behavioral and neurochemical alterations: insights into c-JNK and p38MAPK pathways. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 17, 1–32 (2024).

Mamtaj, A., Rajeshwar, K. Y., Elizabeth, M., Aarti, T. & Sidharth, M. Exploring molecular approaches in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug targets from clinical and pre-clinical findings. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 14, 263–280 (2021).

Xu, W., Huang, Y. & Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome in neuroinflammation and central nervous system diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 22, 341–355 (2025).

Yao, J., Wang, Z., Song, W. & Zhang, Y. Targeting NLRP3 inflammasome for neurodegenerative disorders. Mol. psychiatry 28, 4512–4527 (2023).

Anderson, F. L. et al. Plasma-borne indicators of inflammasome activity in Parkinson’s disease patients. NPJ Parkinson’s Dis. 7, 2 (2021).

Gordon, R. et al. Inflammasome inhibition prevents α-synuclein pathology and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaah4066 (2018).

Huang, Y., Xu, W. & Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 18, 2114–2127 (2021).

Akbal, A. et al. How location and cellular signaling combine to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 19, 1201–1214 (2022).

Sun, M. F. & Shen, Y. Q. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota and microbial metabolites in Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 45, 53–61 (2018).

Mou, Y. et al. Gut microbiota interact with the brain through systemic chronic inflammation: implications on neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and aging. Front. Immunol. 13, 796288 (2022).

Metta, V. et al. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: molecular pathology and implications of gut microbiome, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation. J. Neurol. 269, 1154–1163 (2022).

Houser, M. C. et al. Stool immune profiles evince gastrointestinal inflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 33, 793–804 (2018).

Qu, Y. et al. Short-chain fatty acid aggregates alpha-synuclein accumulation and neuroinflammation via GPR43-NLRP3 signaling pathway in a model Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 62, 6612–6625 (2025).

Stekovic, S. et al. Alternate day fasting improves physiological and molecular markers of aging in healthy, non-obese humans. Cell Metab. 30, 462–476.e466 (2019).

Singh, R. et al. Late-onset intermittent fasting dietary restriction as a potential intervention to retard age-associated brain function impairments in male rats. Age (Dordr.) 34, 917–933 (2012).

Mattson, M. P. Energy intake and exercise as determinants of brain health and vulnerability to injury and disease. Cell Metab. 16, 706–722 (2012).

Martin, B., Mattson, M. P. & Maudsley, S. Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting: two potential diets for successful brain aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 5, 332–353 (2006).

Elias, A., Padinjakara, N. & Lautenschlager, N. T. Effects of intermittent fasting on cognitive health and Alzheimer’s disease. Nutr. Rev. 81, 1225–1233 (2023).

Fann, D. Y., Ng, G. Y., Poh, L. & Arumugam, T. V. Positive effects of intermittent fasting in ischemic stroke. Exp. Gerontol. 89, 93–102 (2017).

Fann, D. Y. et al. Intermittent fasting attenuates inflammasome activity in ischemic stroke. Exp. Neurol. 257, 114–119 (2014).

Cignarella, F. et al. Intermittent fasting confers protection in cns autoimmunity by altering the gut microbiota. Cell Metab. 27, 1222–1235.e1226 (2018).

Acosta-Rodr¡guez, V. et al. Circadian alignment of early onset caloric restriction promotes longevity in male C57BL mice. Science 376, 1192–1202 (2022).

Ojha, U., Khanal, S., Park, P. H., Hong, J. T. & Choi, D. Y. Intermittent fasting protects the nigral dopaminergic neurons from MPTP-mediated dopaminergic neuronal injury in mice. J. Nutritional Biochem. 112, 109212 (2023).

Tatulli, G. et al. Intermittent fasting applied in combination with rotenone treatment exacerbates dopamine neurons degeneration in mice. Front Cell Neurosci. 12, 4 (2018).

Kim, K. H. et al. Intermittent fasting promotes adipose thermogenesis and metabolic homeostasis via VEGF-mediated alternative activation of macrophage. Cell Res. 27, 1309–1326 (2017).

Castello, L. et al. Alternate-day fasting protects the rat heart against age-induced inflammation and fibrosis by inhibiting oxidative damage and NF-kB activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 47–54 (2010).

Wei, B. R., Zhao, Y. J., Cheng, Y. F., Huang, C. & Zhang, F. Helicobacter pylori infection and Parkinson’s disease: etiology, pathogenesis and levodopa bioavailability. Immun. Ageing: I A 21, 1 (2024).

Sayavedra, L. et al. Desulfovibrio diazotrophicus sp. nov., a sulfate-reducing bacterium from the human gut capable of nitrogen fixation. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 3164–3181 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Features of gut microbiota in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease]. Zhonghua Xue Zhi 100, 1017–1022 (2020).

Choi, J. G., Huh, E., Kim, N., Kim, D. H. & Oh, M. S. High-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing reveals that 6-hydroxydopamine affects gut microbial environment. PLoS ONE 14, e0217194 (2019).

Fontana, L., Partridge, L. & Longo, V. D. Extending healthy life span-from yeast to humans. Science 328, 321–326 (2010).

de Cabo, R. & Mattson, M. P. Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 2541–2551 (2019).

Hadem, I. K. H., Majaw, T., Kharbuli, B. & Sharma, R. Beneficial effects of dietary restriction in aging brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 95, 123–133 (2019).

Zhou, Z. L. et al. Neuroprotection of fasting mimicking diet on MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mice via gut microbiota and metabolites. Neurotherapeutics 16, 741–760 (2019).

Brocchi, A., Rebelos, E., Dardano, A., Mantuano, M. & Daniele, G. Effects of intermittent fasting on brain metabolism. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061275 (2022).

Mattson, M. P., Longo, V. D. & Harvie, M. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res Rev. 39, 46–58 (2017).

Stefano, G. B. et al. Gut, Microbiome, and brain regulatory axis: relevance to neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 38, 1197–1206 (2018).

Vascellari, S. et al. Gut microbiota and metabolome alterations associated with Parkinson’s disease. mSystems 5, e00561–20 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Effects of electroacupuncture on the intestinal thioredoxin interaction protein/Nod-like receptor 3 signaling pathway in mice with Parkinson’s disease. Zhen Yan Jiu Acupunct. Res. 48, 1041–1047 (2023).

Lee, E. et al. MPTP-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia plays a central role in dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Cell Death Differ. 26, 213–228 (2019).

Huang, Q. et al. The interplay between α-Synuclein and NLRP3 inflammasome in Parkinson’s disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 168, 115735 (2023).

Qin, Y. et al. Impaired autophagy in microglia aggravates dopaminergic neurodegeneration by regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 91, 324–338 (2021).

Amo-Aparicio, J., Daly, J., Højen, J. F. & Dinarello, C. A. Pharmacologic inhibition of NLRP3 reduces the levels of α-synuclein and protects dopaminergic neurons in a model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 20, 147 (2023).

Pellegrini, C. et al. Microbiota-gut-brain axis in health and disease: Is NLRP3 inflammasome at the crossroads of microbiota-gut-brain communications?. Prog. Neurobiol. 191, 101806 (2020).

Ahmed, H. et al. Microbiota-derived metabolites as drivers of gut-brain communication. Gut Microbes 14, 2102878 (2022).

Cook, J. & Prinz, M. Regulation of microglial physiology by the microbiota. Gut Microbes 14, 2125739 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. Gut microbiome-derived indole-3-carboxaldehyde regulates stress vulnerability in chronic restraint stress by activating aryl hydrocarbon receptors. Pharm. Res. 213, 107654 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Alpha-linolenic acid ameliorates T2DM via reshaping gut-liver axis and inflammatory GPR120-NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway in mouse and rat models. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. phytopharmacol. 147, 157214 (2025).

Zhou, J., Yang, Q., Wei, W., Huo, J. & Wang, W. Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharide alleviates ulcerative colitis by modulating gut microbiota and SCFA/GPR/NLRP3 pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 337, 118928 (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Bacillus velezensis MZ09 alleviates DSS-induced colitis in piglets by remodeling the intestinal microbiota activating the SCFAs-GPR43-STAT3 pathway and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 16, 120 (2025).

Shi, Y. et al. Propionate alleviates ulcerative colitis by modulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Food Funct. 16, 6925–6938 (2025).

Chang, Y. et al. Gut-derived macrophages link intestinal damage to brain injury after cardiac arrest through TREM1 signaling. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 22, 437–455 (2025).

Traba, J. et al. Fasting and refeeding differentially regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human subjects. J. Clin. Invest 125, 4592–4600 (2015).

Lai, F. et al. Intestinal pathology and gut microbiota alterations in a methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 43, 1986–1999 (2018).

Dong, Y. et al. Neuroprotective effects of bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis NJ241 in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease:iImplications for gut microbiota and PGC-1à. Mol. Neurobiol. 61, 7534–7548 (2024).

Zhao, Z. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation protects rotenone-induced Parkinson’s disease mice via suppressing inflammation mediated by the lipopolysaccharide-TLR4 signaling pathway through the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Microbiome 9, 226 (2021).

Dodiya, H. B. et al. Chronic stress-induced gut dysfunction exacerbates Parkinson’s disease phenotype and pathology in a rotenone-induced mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 135, 104352 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. VGluT2 neuron subtypes in the paraventricular thalamic nucleus regulate depression in paraquat-induced Parkinson’s disease. J. Hazard. Mater. 472, 134559 (2024).

Duan, W. et al. Upregulation of mitochondrial calcium uniporter contributes to paraquat-induced neuropathology linked to Parkinson’s disease via imbalanced OPA1 processing. J. Hazard. Mater. 453, 131369 (2023).

Yu, J. et al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota inhibits NMNAT2 to promote neurobehavioral deficits and oxidative stress response in the 6-OHDA-lesioned rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 20, 117 (2023).

Mazzocchi, M. et al. Peripheral administration of the Class-IIa HDAC inhibitor MC1568 partially protects against nigrostriatal neurodegeneration in the striatal 6-OHDA rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 102, 151–160 (2022).

Tao, J. et al. The protective role of microbiota in the prevention of MPTP/P-induced Parkinson’s disease by resveratrol. Food Funct. 14, 4647–4661 (2023).

Mannino, D. et al. Neuroprotective effects of GSK-343 in an in vivo model of MPTP-induced nigrostriatal degeneration. J. Neuroinflamm. 20, 155 (2023).

Mustapha, M. & Mat Taib, C. N. MPTP-induced mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: A promising direction of therapeutic strategies. Bosn. J. basic Med. Sci. 21, 422–433 (2021).

Lal, R., Singh, A., Watts, S. & Chopra, K. Experimental models of Parkinson’s disease: challenges and opportunities. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 980, 176819 (2024).

Zhang, Q. S. et al. Reassessment of subacute MPTP-treated mice as animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Pharm. Sin. 38, 1317–1328 (2017).

Luchtman, D. W., Shao, D. & Song, C. Behavior, neurotransmitters and inflammation in three regimens of the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Physiol. Behav. 98, 130–138 (2009).

Zhou, X. et al. Neuroprotective effect of ceftriaxone on MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mouse model by regulating inflammation and intestinal microbiota. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 9424582 (2021).

Cui, C. et al. Vancomycin pretreatment on MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mice exerts neuroprotection by suppressing inflammation both in brain and gut. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol 18, 72–89 (2022).

Yu, H. Y. et al. Exendin-4 and linagliptin attenuate neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 18, 1818–1826 (2023).

Matsuo, K. et al. Inhibition of MPTP-induced α-synuclein oligomerization by fatty acid-binding protein 3 ligand in MPTP-treated mice. Neuropharmacology 150, 164–174 (2019).

Arotcarena, M. L. et al. Bidirectional gut-to-brain and brain-to-gut propagation of synucleinopathy in non-human primates. Brain 143, 1462–1475 (2020).

Van Den Berge, N. et al. Evidence for bidirectional and trans-synaptic parasympathetic and sympathetic propagation of alpha-synuclein in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 138, 535–550 (2019).

Braak, H., de Vos, R. A., Bohl, J. & Del Tredici, K. Gastric alpha-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner’s and Auerbach’s plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson’s disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci. Lett. 396, 67–72 (2006).

Challis, C. et al. Gut-seeded alpha-synuclein fibrils promote gut dysfunction and brain pathology specifically in aged mice. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 327–336 (2020).

Uemura, N. et al. Inoculation of alpha-synuclein preformed fibrils into the mouse gastrointestinal tract induces Lewy body-like aggregates in the brainstem via the vagus nerve. Mol. Neurodegener. 13, 21 (2018).

Kim, S. et al. Transneuronal propagation of pathologic alpha-synuclein from the gut to the brain models Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 103, 627–641.e627 (2019).

Schachtle, M. A. & Rosshart, S. P. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in health and disease and its implications for translational research. Front Cell Neurosci. 15, 698172 (2021).

Rao, J. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation ameliorates stress-induced depression-like behaviors associated with the inhibition of glial and NLRP3 inflammasome in rat brain. J. Psychiatr. Res. 137, 147–157 (2021).

Sun, J. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation alleviated Alzheimer’s disease-like pathogenesis in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 2 (2019).

Zhong, Z. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation exerts a protective role in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease via the TLR4/PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway stimulated by α-synuclein. Neurochem. Res. 46, 3050–3058 (2021).

Si, W. et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG induces STING-dependent IL-10 in intestinal monocytes and alleviates inflammatory colitis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 135, e174910 (2025).

Zhou, W. et al. The gut microbe Bacteroides fragilis ameliorates renal fibrosis in mice. Nat. Commun. 13, 6081 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. The metabolite indole-3-acetic acid of bacteroides ovatus improves atherosclerosis by restoring the polarisation balance of m1/m2 macrophages and inhibiting inflammation. Adv. Sci. (Weinh., Baden. Wurtt., Ger.) 12, e2413010 (2025).

Zhou, Q. et al. Natural, safety immunomodulatory derivatives of lactobacillus biofilms promote diabetic wound healing by metabolically regulating macrophage phenotype and alleviating local inflammation. J. Adv. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2025.04.001 (2025).

Zhang, S. et al. Mechanisms of Baicalin alleviates intestinal inflammation: role of M1 macrophage polarization and lactobacillus amylovorus. Adv. Sci. (Weinh., Baden.-Wurtt., Ger.) 12, e2415948 (2025).

Barichella, M. et al. Unraveling gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 34, 396–405 (2019).

Qian, Y. et al. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in Chinese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 70, 194–202 (2018).

Li, C. et al. Gut microbiota differs between Parkinson’s disease patients and healthy controls in northeast China. Front Mol. Neurosci. 12, 171 (2019).

Nishiwaki, H. et al. Meta-analysis of gut dysbiosis in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 35, 1626–1635 (2020).