Abstract

This study aims to investigate the association between lung function and various types of sensory impairments (specifically visual and hearing impairments) in the elderly population in the middle-aged and older adults in China. This study utilizes data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) from the 2011 and 2015 waves of interviews. Participants aged 45 and older with complete data were included in the study. Lung function was assessed using peak expiratory flow (PEF). Multivariable logistic regression and trend regression models analyzed the cross-sectional relationships between PEF, predicted PEF values, and various sensory impairments (SI) The study also examined the prospective relationship between baseline PEF and sensory impairment deterioration using restricted cubic splines for visualization. Finally, subgroup analyses were performed to validate the results’ stability. The cross-sectional analysis, after adjusting for confounders, revealed that higher baseline and predicted PEF values were associated with a lower prevalence of SI. This inverse relationship was consistent across various types of impairments, including visual impairment, distance vision impairment, near vision impairment, and hearing impairment. The trend ORs were as follows: (Baseline PEF: 0.894 [0.846, 0.945], 0.881 [0.839, 0.926], 0.922 [0.878, 0.969], and 0.916 [0.873, 0.961]; Predicted PEF %: 0.829 [0.786, 0.874], 0.755 [0.719, 0.791], 0.872 [0.831, 0.914], and 0.770 [0.735, 0.806]). In the combined analysis of sensory impairment types, including single sensory impairment (SSI) and dual sensory impairment (DSI), higher PEF values were also linked to lower prevalence rates. The trend ORs for baseline PEF were 0.924 [0.862, 0.990] and 0.884 [0.826, 0.945], and for predicted PEF % values, the trend ORs were 0.915[0.853, 0.981] and 0.775 [0.725, 0.829]. During follow-up, baseline PEF was significantly associated with the deterioration of Non-SI to DSI. Specifically, the adjusted OR for Q4 relative to Q1 was 0.609 [0.397, 0.933], with a trend OR of 0.862 [0.751, 0.988]. Changes in PEF and predicted PEF percentage values during follow-up were not significantly associated with worsening SI. Subgroup analyses indicated that the inverse relationship between PEF and sensory impairments was significant across various age groups, genders, smoking statuses, and lung disease backgrounds, though the correlation was weaker in non-smokers and individuals with lung diseases. Higher PEF values are associated with a lower prevalence of various sensory impairments and a reduced risk of worsening these impairments in middle-aged and older adults. This study supports the effective screening of SI, particularly in identifying high-risk individuals who may experience the progression of DSI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sensory impairments (SI) refer to the loss or decline in the functioning of sensory perception, including vision, hearing, smell, and other sensory functions, caused by physiological diseases, conditions, or aging factors1,2. Among these, vision impairment (VI) and hearing impairment (HI) are the most common types3,4. According to the World Health Organization’s 2019 World Report on Hearing and Vision, approximately 29% of the global population of 7.5 billion people suffer from VI, and 20% from HI5. With the aging of the global population, the prevalence of dual sensory impairments (DSI)—the simultaneous occurrence of vision and hearing impairments—is expected to continue rising6. A large body of research has confirmed that SI are associated with various adverse health outcomes, such as cognitive disorders7, dementia8, and increased mortality9. Notably, DSI is not only the combined damage to sensory functions, but also a significant risk factor for neuropsychiatric diseases. Studies have shown that patients with DSI are at a significantly higher risk of developing cognitive impairment, depression, and dementia compared to those with single-sensory impairment. Its synergistic effect may accelerate brain structural damage10,11,12, further exacerbating the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, and could even be pathologically linked to severe conditions such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica10,13,14,15. The Lancet Commission has classified visual and auditory impairments as core modifiable risk factors for dementia16,17. In this context, with the global aging population increasing, the public health burden caused by DSI is growing, and its precise risk identification holds significant public health value for the prevention and control of neurological diseases12.

Lung function is an important factor influencing the health of middle-aged and older adults, and peak expiratory flow (PEF) is a simple and easily accessible lung function measure. PEF reflects the instantaneous expiratory flow velocity during forced exhalation. PEF effectively screens for lung function impairments in adults aged 40 and older18, and it is widely used in the diagnosis of expiratory muscle dysfunction, airway obstruction, and other pulmonary issues. Compared to the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC), PEF is more sensitive in the early identification of central and upper airway obstructions19. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have focused on the relationship between lung function and adverse health outcomes in the middle-aged and older adults. For instance, PEF has been shown to be associated with frailty20, exercise risk syndromes21, and other health issues. Furthermore, cohort studies have found that persistent HI and VI significantly increase the risk of chronic lung diseases (P = 0.002, HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.17–1.99; P = 0.042, HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.02–2.31), and Mendelian randomization (MR) analyses have confirmed the significance of these associations11. Despite existing studies exploring the association between lung function and SI, research on this topic remains relatively limited, and the quality of existing studies is generally low. Some studies have found that individuals with VI are more likely to report having COPD compared to those without VI (OR 1.65)22. Research based on the Korean National Health Insurance (NHI) system has shown that COPD patients have a higher likelihood of HI, with an odds ratio of 1.10–1.2123. Additionally, the population-based HUNT study in Norway has found a relationship between COPD and long-term hearing loss24, although some other studies, such as one conducted in Austria, did not support a significant relationship between COPD and HI25.

While existing literature suggests certain correlations between lung function and SI, research specifically focused on DSI remains scarce. DSI may have different relationships and mechanisms in relation to lung function, and its severity and associated socioeconomic costs are significantly higher than those of single sensory impairments (SSI). Furthermore, most related studies have concentrated on populations with chronic lung diseases such as COPD, with few studies investigating this association in the general middle-aged and older adults within community settings. Therefore, there is insufficient evidence to establish a reliable and significant independent relationship between lung function and SI. Given this, the present study aims to explore the relationship between PEF and SI in depth, particularly its impact on DSI, using large-scale prospective cohort data. The hypothesis of this study is that lower PEF values will increase the risk of SI, particularly DSI, in the middle-aged and older adults. To test this hypothesis, we use data from the CHARLS, including waves 1 (2011) and 3 (2015), for both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Specifically, this study focuses on visual and hearing impairments in middle-aged and older adults. The findings could help simplify the assessment process for these sensory impairments and promote early detection and prevention.

Methods

Study participants and design

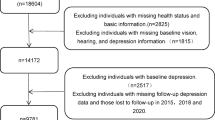

This study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The data for this study were derived from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationwide longitudinal survey targeting community residents aged 45 and older across 28 provinces in China26. The baseline survey was conducted in 2011 and included 150 county-level units and 450 village-level units. The CHARLS study protocol has been approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University (approval number for household surveys: IRB00001052-11015; approval number for biomarker collection: IRB00001052-11014), and all participants provided written informed consent. This study utilized data from the first wave (2011) and third wave (2015) of the CHARLS dataset. The inclusion criterion was participants aged 45 and older. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) incomplete lung function data at baseline or follow-up; (2) participants whose sensory impairment improved from baseline to follow-up (Since sensory impairment are degenerative in nature, any improvement is typically due to medical interventions, such as the use of hearing aids or glasses. These interventions may temporarily alleviate symptoms but do not reverse the underlying degeneration. Therefore, to more accurately reflect the relationship between lung function and the natural progression of sensory impairments, we excluded individuals with improved conditions)5; (3) participants lost to follow-up or those with missing SI data; (4) participants with malignant tumors (Cancer may affect lung function, particularly tumors in the respiratory system, including lung cancer, which can directly impact the measurement and results of PEF)19. Within the design and results of this study, “sensory impairment” is strictly confined to vision and hearing, distinguishing it from the broader clinical concept of sensory function11,27. The final analysis included 7331 participants. The participant exclusion process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Exposure

Lung function was assessed using a peak flow meter (Everpure Medical Plastic Co., Shanghai, China) equipped with a disposable mouthpiece. Trained technicians obtained three PEF measurements per participant. Participants were instructed to stand upright, take a deep breath, place their lips around the outer edge of the mouthpiece, and exhale with maximum effort, ensuring that the mouthpiece was completely covered to avoid air leakage. A 30-s rest period was observed between measurements to ensure consistency and prevent fatigue. The highest value from the three PEF measurements was used in the analysis, with a higher PEF indicating better lung function21,28. To ensure the reliability of the exposure variable and maintain data integrity, we implemented several quality control measures. Additionally, the study utilized trained technicians who followed standardized measurement protocols to ensure consistency across all assessments19,29. Both baseline and endpoint PEF assessments were conducted, and the change in PEF (ΔPEF) was calculated by subtracting the baseline value from the endpoint value. To further enhance the accuracy of the lung function assessment, the ratio of measured PEF to predicted PEF was also used as an additional exposure indicator. The predicted PEF values were calculated using the validated Zhongnan Mountain formula, which is applicable to Chinese adults: for men, the formula is 75.6 + 20.4 × age − 0.41 × age² + 0.002 × age³ + 1.19 × height, and for women, the formula is 282.0 + 1.79 × age − 0.046 × age² + 0.68 × height30.

Assessment of VI and HI

HI and VI status were collected through self-reported questionnaires. The assessment of VI included the following questions: (1) “How is your distance vision (with glasses or corrective lenses), such as being able to recognize a friend across the street?” (2) “How is your near vision (with glasses or corrective lenses), such as being able to read ordinary newspaper print?” Each response could be categorized as “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair,” or “poor.” If either of the responses was “fair” or “poor,” the participant was classified as having VI. VI was further categorized into DVI and NVI based on the specific question responses31,32. An additional question assessed HI: “How is your hearing (including hearing aids if normally used; excluding hearing aids if not normally used)? Is it excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” If the answer was “fair” or “poor,” the participant was classified as having HI. When both hearing and vision impairments were present, the participant was considered to have DSI. SI was classified into three groups: no sensory impairment, SSI, and DSI by asking, “Do you have vision and/or hearing problems?” SSI included only VI or HI11.

As noted by some participants, sensory impairments are unlikely to improve without medical interventions33,34. To avoid potential confounding, this study focused only on the transitional process of worsening SI. The primary focus of the study was on three types of sensory impairment transitions: non-SI to single SI, non-SI to DSI, and single SI to DSI5.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were described according to their distribution characteristics. Normality was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For normally distributed quantitative data, means and standard deviations (SDs) were used; for non-normally distributed data, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were presented. Categorical data were described using absolute frequencies and relative frequencies (%). The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess differences among the four groups stratified by PEF and predicted PEF quartiles, while comparisons of percentages were performed using the chi-square test.

In the cross-sectional analysis, both univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to explore the relationship between PEF and predicted PEF with different types of sensory impairments. The results are presented as ORs with their 95% CIs. In the multivariate logistic regression models, Model 1 adjusted for covariates including gender, age, residence, education level, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and BMI. Model 2 further adjusted for comorbid conditions, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart disease, stroke, lung disease, and diabetes. Additionally, the variance inflation factor (VIF) method was used to check for multicollinearity among the independent variables. A VIF value ≥ 5 indicates significant multicollinearity within the model. In this study, no significant multicollinearity was detected in the logistic regression analysis. To explore the dose-response relationship between PEF and predicted PEF and the risk of various sensory impairments, a restricted cubic splines (RCS) approach was employed. The reference level for the restricted cubic spline analysis was set at the median value of maximal grip strength, with the baseline set to Y = 1. Furthermore, to investigate the relationship between FEF and predicted FEF and the risk of SI, trend regression analysis was performed using four quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4) of PEF and predicted PEF, with the lowest quartile (Q1) as the reference group. This analysis aimed to assess the changing risk trend from Q1–Q4.

In the longitudinal analysis, we also used multivariate logistic regression models to explore the association between PEF and predicted PEF and the worsening of SI, and further trend regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between PEF and predicted PEF and the progression of SI. All statistical analyses were performed using R Studio version 4.3.2, with a statistical significance level set at p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the included participants

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of participants stratified by the quartiles of PEF. Among the 7331 participants included in the cross-sectional analysis, 5542 (75.60%) had VI, and 3852 (52.54%) had HI. Based on the number of sensory impairments, 2476 participants (33.77%) were categorized into the SSI group, and 3459 participants (47.18%) were categorized into the DSI group. Specifically, in the SSI group, 2084 participants had only VI, and 394 participants had only HI.

The baseline characteristics of participants showed a median age of 58.00 years [51.00, 64.00], with 53.87% being female. When classified according to the quartiles of PEF (Table 1), the prevalence of SI significantly decreased with increasing PEF. Specifically, the proportion of participants with VI was 79.44%, 79.31%, 75.47%, and 67.94%, respectively, across the PEF quartiles. For HI, the proportions were 58.51%, 54.89%, 50.39%, and 46.07%, respectively. When classified by the number of sensory impairments, the prevalence of SSI was 31.15%, 34.19%, 35.60%, and 34.28%, respectively, and the prevalence of DSI was 53.40%, 50.00%, 45.13%, and 39.87%, respectively (all p < 0.001).

Additionally, participants with higher PEF were more likely to have the following characteristics: younger age, higher BMI, residing in urban areas, higher educational attainment, being widowed, divorced, or separated, past and current alcohol and tobacco use, and fewer comorbidities including hypertension, dyslipidemia, lung disease, and heart disease (Table 1). The baseline data stratified by the PEF % predicted quartiles can be found in Table S1.

Cross-sectional association between baseline PEF and sensory impairment in 2011

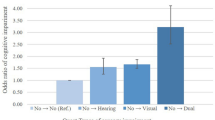

This study employed both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to investigate the cross-sectional associations between baseline PEF and PEF % predicted and the manifestations of SI (Table 2). According to the type of sensory impairment, first, for VI, the trend regression analysis of PEF showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q4 was 0.726 (95% CI 0.612, 0.862), and the trend OR was 0.894 (95% CI 0.846, 0.945). The trend regression analysis of PEF % predicted also showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q4 was 0.564 (95% CI 0.478, 0.667), and the trend OR was 0.829 (95% CI 0.786, 0.874). Furthermore, both PEF and PEF % predicted, treated as continuous variables, exhibited a significant dose-response relationship with VI (PEF: P-overall < 0.001; Non-linear P = 0.104; PEF % predicted: P-overall < 0.001; P non-linear = 0.049) (Fig. 2A, Figure S1A). For DVI and NVI, the trend regression analysis for PEF showed ORs of 0.881 (95% CI 0.839, 0.926) for DVI and 0.922 (95% CI 0.878, 0.969) for NVI. The trend regression analysis for PEF % predicted showed ORs of 0.755 (95% CI 0.719, 0.791) for DVI and 0.872 (95% CI 0.831, 0.914) for NVI. Further multivariate-adjusted RCS analysis results are shown in Figure S1. For HI, the adjusted trend regression analysis for PEF showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q3 and Q4 were 0.857 (95% CI 0.746, 0.983) and 0.769 (95% CI 0.662, 0.894), respectively, with a trend OR of 0.916 (95% CI 0.873, 0.961). The trend regression analysis for PEF % predicted showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q2, Q3, and Q4 were 0.795 (95% CI 0.692, 0.913), 0.623 (95% CI 0.542, 0.717), and 0.450 (95% CI 0.388, 0.522), respectively, with a trend OR of 0.770 (95% CI 0.735, 0.806). Further multivariate-adjusted RCS analysis revealed a significant dose-response relationship between both PEF and PEF % predicted as continuous variables and HI (PEF: P-overall < 0.001; P non-linear = 0.140; PEF % predicted: P-overall < 0.001; P non-linear = 0.406) (Fig. 2B, Figure S1A).

Based on a multivariable-adjusted restricted cubic spline model, we fully adjusted for factors such as age, gender, alcohol consumption, smoking, marital status, education level, place of residence, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart disease, stroke, lung disease, and diabetes. A Vision Impairment (VI); B Hearing Impairment (HI); C Single Sensory Impairment (SSI); D Dual Sensory Impairment (DSI). ight Y-axis: Density, represents the distribution density values of different PEF levels in the study population. lshap: stands for L-shaped restricted cubic spline curve.

For sensory impairments categorized by number, for SSI, the trend regression analysis for PEF showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q4 was 0.784 (95% CI 0.632, 0.972), and the trend OR was 0.924 (95% CI 0.862, 0.990) (Table 2). The trend regression analysis for PEF % predicted showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q4 was 0.785 (95% CI 0.629, 0.980), and the trend OR was 0.915 (95% CI 0.853, 0.981). Further multivariate-adjusted RCS analysis revealed a significant dose-response relationship between both PEF and PEF % predicted as continuous variables and SSI (PEF: P-overall = 0.022; P non-linear = 0.108; PEF % predicted: P-overall < 0.001; P non-linear = 0.001) (Fig. 2C, Figure S1C). For only VI, the trend regression analysis for PEF showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q4 was 0.784 (95% CI 0.627, 0.979), and the multivariate trend OR was 0.923 (95% CI 0.860, 0.991) (Table S2). The trend regression analysis for PEF % predicted showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q4 was 0.788 (95% CI 0.630, 0.985), and the trend OR was 0.912 (95% CI 0.851, 0.978). For only HI, the trend regression analysis for PEF showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q4 was 0.676 (95% CI 0.471, 0.970), and the multivariate trend OR was 0.885 (95% CI 0.790, 0.991) (Table S2). The trend regression analysis for PEF % predicted showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q3 and Q4 were 0.575 (95% CI 0.403, 0.819) and 0.577 (95% CI 0.390, 0.854), respectively, with a trend OR of 0.804 (95% CI 0.712, 0.907). Finally, for DSI, the adjusted trend regression analysis for PEF showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q4 was 0.708 (95% CI 0.574, 0.873), and the trend OR was 0.884 (95% CI 0.826, 0.945) (Table 2). The trend regression analysis for PEF % predicted showed that, compared to Q1, the OR for Q3 and Q4 were 0.657 (95% CI 0.536, 0.806) and 0.458 (95% CI 0.371, 0.565), respectively, with a trend OR of 0.775 (95% CI 0.725, 0.829). Further multivariate-adjusted RCS analysis revealed a significant dose-response relationship between both PEF and PEF % predicted as continuous variables and DSI (PEF: P-overall < 0.001; P non-linear = 0.035; PEF % predicted: P-overall < 0.001; P non-linear < 0.001) (Fig. 2D, Figure S1D).

Longitudinal relationship between baseline PEF and the worsening sensory impairment

During the follow-up period, a total of 437 participants transitioned from Non-SI to SSI, and 616 participants transitioned to DSI. Additionally, 1584 participants in the SSI group transitioned to DSI. Regarding the analysis of the transition from Non-SI to Single SI, the trend regression analysis in the unadjusted model showed that, compared to Q1, the likelihood of transition to Single SI in Q4 was significantly reduced (OR 0.639, 95% CI 0.429, 0.952), with a trend OR of 0.860 (95% CI 0.758, 0.976). However, after adjustment, this result was no longer significant. For the analysis of the transition from Non-SI to DSI, the trend regression analysis in the unadjusted model showed that, compared to Q1, the likelihood of transition to DSI in Q4 was significantly reduced for both PEF and PEF % predicted. Specifically, the OR for PEF was 0.534 (95% CI 0.370, 0.772), and the OR for PEF % predicted was 0.631 (95% CI 0.434, 0.917) (Table 3, Table S3). In the adjusted trend regression analysis, the effect of PEF % predicted was no longer significant; however, the impact of PEF on the transition from Non-SI to DSI remained significant. The likelihood of transition in Q4 was significantly lower than in Q1, with an OR of 0.609 (95% CI 0.397, 0.933), and the trend OR was0.862 (95% CI 0.751, 0.988) (Table 3, Table S3). Further multivariate-adjusted RCS analysis revealed a significant dose-response relationship between PEF as a continuous variable and the transition from Non-SI to DSI (P-overall = 0.013; P non-linear = 0.329). Additionally, multivariate logistic regression analysis with PEF as a continuous variable showed a significant negative correlation between PEF and the transition in the overall cohort, indicating that for each 10 unit increase in PEF, the odds of transitioning to DSI were reduced (OR = 0.986, 95% CI: 0.975, 0.996). Finally, during the follow-up period, no significant associations were found between changes in PEF or PEF % predicted and the deterioration of SI (Fig. 3).

Based on a multivariable-adjusted restricted cubic spline model, we fully adjusted for factors such as age, gender, alcohol consumption, smoking, marital status, education level, place of residence, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart disease, stroke, lung disease, and diabetes. A PEF and Non-SI to Single SI; B PEF and Non-SI to DSI; C PEF and Single SI to DSI; D Predicted PEF % and Non-SI to Single SI; E Predicted PEF % and Non-SI to DSI; F Predicted PEF % and Single SI to DSI. Right Y-axis: Density, represents the distribution density values of different PEF levels in the study population. lshap: stands for L-shaped restricted cubic spline curve.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on various characteristics such as age, sex, smoking status, drinking status, and lung disease, as shown in Table 4. In the cross-sectional subgroup analysis, we found that for every 10 L/min increase in PEF, the ORs for VI and HI in participants under 60 years of age were 0.986 (P < 0.001) and 0.990 (P < 0.001), respectively. In participants aged 60 years or older, PEF showed a significant negative association not only with VI and HI but also with SSI, with ORs of 0.983 (P < 0.001), 0.988 (P < 0.001), and 0.985 (P = 0.003), respectively. For those who had ever smoked or currently smoke, the relationship between PEF and SI was weaker, particularly for VI and SSI, where ORs were 0.985 (P = 0.080) and 1.000 (P = 0.921), respectively. Regarding PEF % predicted, except for the relationships with VI and SSI in participants aged ≥ 60 years and those with lung disease, the association between PEF % predicted and SI was not significant in these subgroups; however, it was significant in all other cases (Table 4).

In the longitudinal subgroup analysis, for changes in PEF, the results showed that in participants under 60 years of age, PEF was significantly negatively associated with the transition from Non-SI to SSI (OR = 0.983, P = 0.019). In participants aged 60 years or older, the relationship between PEF and sensory impairment deterioration was weaker. Moreover, in males, there was a stronger negative correlation in the transition from Non-SI to SSI (OR = 0.985, P = 0.032). For non-smokers, PEF was significantly negatively correlated with the transitions from Non-SI to DSI and Single SI to DSI (Non-SI to DSI OR = 0.983, P = 0.045; Single SI to DSI OR = 0.988, P = 0.035). Finally, in participants with lung disease, there was also a strong negative correlation in the transition from Non-SI to SSI (OR = 0.985, P = 0.032). Regarding changes in PEF % predicted, for non-smokers, PEF % predicted was significantly associated with the transition from Non-SI to DSI (OR = 0.949, P = 0.037); in all other conditions, the relationship was not significant (Table S4).

Discussion

Our study systematically explored for the first time the relationship between PEF and different types of SI in the middle-aged and older adults in China. Cross-sectional analysis revealed significant associations between PEF and various sensory impairments in middle-aged and older adults in China, irrespective of the type of sensory impairment (VI and HI) or the number of affected organs (e.g., SSI and DSI). Longitudinal data further demonstrated that lower PEF was closely related to the occurrence and progression of SI in the middle-aged and older adults, particularly with a significantly increased risk of conversion to DSI. These findings suggest that pulmonary function impairment may be an important predictor for the progression of SI.

Some studies have already explored the relationship between chronic lung disease and SI. For instance, a study from Georgia found that individuals with VI were more likely to report having COPD, and COPD patients had a higher risk of optic nerve damage and VI22. Additionally, studies from Brazil and Egypt also indicated that COPD patients were at higher risk of significant hearing loss, especially when oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) was low35. Moreover, as COPD worsened, the risk of hearing loss significantly increased, particularly in moderate and severe COPD patients24. These studies suggest an important link between pulmonary function and SI, and our research further reveals a close relationship between pulmonary function and various sensory impairments as well as the number of affected organs in the middle-aged and older adults. Specifically, the trend regression OR values for PEF with VI, DVI, NVI, and HI were 0.894, 0.881, 0.922, and 0.916, respectively, indicating a more significant relationship with VI and DVI. Furthermore, based on the number of affected organs, the trend regression OR values for PEF with SSI, only VI, only HI, and DSI were 0.924, 0.923, 0.885, and 0.884, respectively, suggesting a particularly strong association with DSI, which may indicate a cumulative effect. Therefore, future studies should focus on the role and mechanisms of pulmonary function impairment, including COPD and other lung diseases, in the progression of multi-sensory impairments. The study also found that PEF were more strongly and consistently associated with visual and hearing impairments than PEF% predicted. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that the PEF% predicted formula was developed using data from a broad age cohort30,36, while the CHARLS cohort is exclusively comprised of individuals aged ≥ 45 years26. The distinctive demographic attributes of this cohort may impede the applicability of standardized formulas, a finding that aligns with the results of analogous CHARLS studies19,37. Secondly, although the PEF% predicted values were adjusted for age, gender, and height, unmeasured confounding factors may influence the results. PEF, as a direct physiological indicator, has the potential to more accurately reflect the biological association between lung function and sensory impairment. However, this observation necessitates further examination within a more extensive cohort to ensure the robustness of the findings.

This study also examined the relationship between PEF, PEF % predicted, and the deterioration of SI, and for the first time, identified the significant role of baseline PEF in predicting the conversion of Non-SI to DSI. PEF, as a key indicator of pulmonary function, was shown to significantly predict the deterioration of SI, particularly for the most severe DSI type. Pulmonary function impairment is closely related to several factors, such as malnutrition, inflammation, and protein-energy wasting19,38, all of which are closely associated with the progression of SI24. PEF, as an easily obtainable pulmonary function index, has been proven to be as effective as spirometry in pulmonary function screening39, providing a new perspective for assessing the risk of SI, especially DSI, in middle-aged and older adults, with important clinical implications. Furthermore, the significance of PEF% predicted disappeared after confounder adjustment. Although PEF% predicted inherently adjusts for age/sex, additional confounders (e.g., BMI, chronic diseases) may collinearly interact with these variables. This likely leads to over-adjustment, masking PEF%‘s independent effect. Future studies should clarify its specific associations through refined modeling.

In the subgroup analysis, we found that for non-smokers, changes in PEF and PEF % predicted were significantly associated with the transition from Non-SI to DSI, while no such relationship was observed in smokers. This suggests that smoking may significantly impact the relationship between pulmonary function and the deterioration of SI, and may act as an independent influencing factor. Smoking has been shown to have both direct and indirect effects on the visual and auditory systems. Harmful substances in cigarette smoke, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), heavy metals, and toxic particles, directly damage the lens through oxidative stress, leading to cataracts and macular degeneration40,41. Furthermore, smoking damages cochlear hair cells and reduces blood flow to the ear through increased free radical oxygen species and elevated carboxyhemoglobin levels, exacerbating hearing loss42,43,44. Therefore, smoking may play a significant role in the relationship between pulmonary function and SI, and future studies should further investigate the effects and mechanisms of smoking on this relationship.

The interplay between pulmonary function and SI can be explained through various mechanisms. In the visual system, participants with poorer pulmonary function often exhibit chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and hypoxic states, all of which are associated with various abnormal ocular findings, including increased retinal venous diameter, thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer around the optic disc, and changes in choroidal thickness at the macula11. Chronic inflammation can directly trigger retinal inflammation and vascular remodeling through exosomes and vesicles, affecting the optic nerve, leading to optic neuritis, demyelination, and reduced blood supply to the optic nerve, causing vascular inflammation. Additionally, systemic inflammation may cause subretinal yellow deposits, changes in retinal pigment epithelium, and choroidal neovascularization, which could promote macular degeneration45. For the auditory system, the inner ear may suffer similar vascular and neuroepithelial damage, leading to hearing loss. There are plausible mechanisms for the relationship between pulmonary function and HI. The cochlea, an organ with extremely high energy consumption, depends on a sufficient oxygen supply and is vulnerable to hypoxic and ischemic damage, affecting the transduction of sound signals46,47,48. Preclinical and clinical studies have pointed out that hypoxia or ischemia can impair the cochlea and cause hearing loss, especially in individuals with long-term respiratory failure, where oxygen supply to the inner ear is limited, further impairing hearing. Furthermore, ischemia caused by hypoxemia may generate reactive oxygen species, exacerbating oxidative damage to tissues49. Chronic inflammation is also considered a common mechanism associated with hearing loss. Studies have shown that chronic inflammation (such as increased C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha) may lead to gradual cochlear degeneration, resulting in age-related hearing loss50. In addition to cochlear dysfunction, studies have also indicated that the incidence of central auditory nervous system dysfunction is higher in COPD patients, as evidenced by prolonged auditory brainstem response latencies, and insufficient oxygen supply to the inner ear significantly impacts cochlear potentials and otoacoustic emissions23,24,51. Moreover, chronic hypoxia and inflammation are thought to increase the risk of central nervous system degeneration or dysfunction in COPD patients. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the chronic hypoxic and inflammatory state in COPD patients, representing poor pulmonary function, may adversely affect the central auditory nervous system, leading to HI.

Based on the findings of this study, we recommend regular screening to assess the role of pulmonary function in preventing or early treatment of SI in middle-aged and older adults with poor pulmonary function. Early intervention is particularly crucial for VI, including regular eye exams and the management of underlying conditions (e.g., diabetes) to prevent further vision deterioration. It is also advisable to minimize exposure to strong light and provide necessary visual aids when needed. For the prevention of HI, special attention should be given to middle-aged and older adults with poor pulmonary function, as they may experience a decline in sound reception or speech recognition over time. This group should avoid exposure to noise and ototoxic drugs, promptly treat comorbidities affecting hearing, quit smoking, correct hypoxemia, and promote the use of hearing aids when necessary. Regular PEF screening can assist healthcare providers in better managing pulmonary function, promptly identifying and intervening in the risk of SI, which will help reduce the occurrence and progression of SI and improve the overall health and quality of life of patients.

Strengths and limitations

One of the major strengths of this study is its comprehensive exploration of the relationship between pulmonary function and different types of sensory impairments in the elderly. In addition to cross-sectional analysis, we also conducted longitudinal analysis to validate the predictive role of PEF and predicted PEF on SI during follow-up. Furthermore, this study provides new evidence for incorporating sensory impairment assessment into pulmonary function screening. More importantly, the use of a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the elderly population in China significantly enhances the reliability and broad applicability of the results.

However, there are several limitations in this study. First, this study assessed pulmonary function solely using PEF, which may not fully represent overall lung health. The CHARLS database primarily includes PEF measurements and lacks standard indicators such as FEV1 and FVC, limiting our ability to compare findings with other established metrics. Future research should incorporate additional pulmonary function indicators to provide a more comprehensive analysis of the relationship between lung function and SI. By expanding the range of assessed metrics, researchers can better identify optimal indicators that correlate with sensory dysfunctions, enhancing our understanding of how lung function affects these impairments. Second, some potential confounding factors, such as smoking status, educational level, and chronic diseases, were collected through self-reported questionnaires, which may introduce recall bias. In addition, while self-reported SI capture individuals’ perceptions of vision and hearing, they may not align with clinical measurements. Previous research has indicated that middle-aged and older adults often overestimate their VI and underestimate their HI52. This discrepancy may introduce bias by skewing the perception of these conditions, ultimately affecting the reported strength of associations. Therefore, future studies should aim to validate these findings by comparing self-reported data with clinical assessment results, such as standardized vision and hearing tests. Professional assessments would provide a more accurate evaluation of VI and HI, thereby improving our understanding of their relationships with lung function and other health outcomes. Furthermore, the formula for PEF% predicted in the study was developed based on data from a broad population in China, and the age requirement of the CHARLS cohort may limit the applicability of PEF% predicted. Including additional cohorts in future research would enhance the generalizability of the findings and verify the more accurate value of PEF% predicted. As this study focused solely on the most common visual and hearing impairments, future research should validate these findings and expand to include other types of sensory impairments, such as taste, smell, and somatic sensations. Additionally, due to limitations in the cohort characteristics and data, this study was unable to explore in depth the association and mechanisms between pulmonary function and neuropsychiatric diseases potentially related to DSI (including multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica). Future research may need to incorporate neuroimaging and biomarker analyses to further elucidate this relationship. Finally, although this study accounted for various potential confounders, some factors that could influence SI, such as physical activity and dietary patterns, were not included in the analysis, which represents another limitation of the study. Due to data limitations, this study did not control for medication use in the middle-aged and older adults, even though medication use could adversely affect SI. Future research could consider including medication use in the analysis to further enhance the accuracy of the assessment.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be provided by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li, Q. et al. Homeostatic dysregulation proceeds in parallel in multiple physiological systems. Aging Cell. 14, 1103–1112, https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12402 (2015).

Fischer, M. E. et al. Age-related sensory impairments and risk of cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64, 1981–1987, https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14308 (2016).

Liu, L., Cao, Z., Ma, Q. & Liao, Z. The association between dual sensory impairment and social participation among older adults in China: a moderated mediation model of activities of daily living and depressive symptoms. BMC Geriatr. 25, 526, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-025-06173-4 (2025).

Xi, J. et al. Association between sensory impairment and cardiometabolic multimorbidity among older Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study based on the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 25, 548, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-025-06140-z (2025).

Li, S. et al. Associations between cooking fuel use, its transitions, and worsening sensory impairments among Chinese middle-aged and older adults: a cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 24, 288, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04746-3 (2024).

Wang, Q., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Zhao, D. & Zhou, C. Dual sensory impairment as a predictor of loneliness and isolation in older adults: national cohort study. JMIR Public. Health Surveill. 8, e39314, https://doi.org/10.2196/39314 (2022).

Fuller, S. D., Mudie, L. I., Siordia, C., Swenor, B. K. & Friedman, D. S. Nationwide prevalence of self-reported serious sensory impairments and their associations with self-reported cognitive and functional difficulties. Ophthalmology 125, 476–485, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.11.003 (2018).

Hwang, P. H. et al. Longitudinal changes in hearing and visual impairments and risk of dementia in older adults in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2210734, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.10734 (2022).

Fisher, D. et al. Impairments in hearing and vision impact on mortality in older people: the AGES-reykjavik study. Age Ageing 43, 69–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft122 (2014).

Guo, H. H. et al. Exploring associations between dual sensory impairment and neuropsychiatric disorders: insights from a prospective cohort study in the UK biobank. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 135, 105865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2025.105865 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Increased risk of chronic diseases and multimorbidity in middle-aged and elderly individuals with early vision, hearing, or dual sensory impairments: insights from prospective cohort studies and Mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Med. 23, 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-025-03857-x (2025).

Yeo, B. S. Y. et al. Dual sensory impairment: global prevalence, future projections, and its association with cognitive decline. Alzheimers Dement. 21, e14465, https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14465 (2025).

Mesaros, S. et al. Diffusion tensor MRI tractography and cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 78, 969–975, https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824d5859 (2012).

Prosperini, L. et al. Multiple sclerosis: white and gray matter damage associated with balance deficit detected at static posturography. Radiology 268, 181–189, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.13121695 (2013).

Finke, C. et al. Association of visual impairment in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder with visual network reorganization. JAMA Neurol. 75, 296–303, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3890 (2018).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the lancet standing commission. Lancet 404, 572–628, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)01296-0 (2024).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 390, 2673–2734, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31363-6 (2017).

Hansen, M. R. H. & Schmid, J. M. Screening for impaired pulmonary function using peak expiratory flow: performance of different interpretation strategies. Respir. Med. Res. 83, 101015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmer.2023.101015 (2023).

Han, S., Xu, Y. & Wang, Y. Association between pulmonary function and rapid kidney function decline: a longitudinal cohort study from CHARLS. BMJ Open. Respir. Res. 11, e002107, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2023-002107 (2024).

Wang, R., Shi, W., Zhou, W., Xu, Y. & Wang, J. Associations between peak expiratory flow and frailty in olderly individuals: findings from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Front. Public. Health 12, 1392581, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1392581 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Association of peak expiratory flow with motoric cognitive risk syndrome among older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 16, 1412542, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2024.1412542 (2024).

Crews, J. E., Chou, C. F., Sekar, S. & Saaddine, J. B. The prevalence of chronic conditions and poor health among people with and without vision impairment, aged ≥65 years, 2010-2014. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 182, 18–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2017.06.038 (2017).

Choi, H. G. et al. Association between COPD and hearing loss. Laryngoscope 134, 4716–4722, https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.31548 (2024).

Aarhus, L., Sand, M. & Engdahl, B. COPD and 20-year hearing decline: the HUNT cohort study. Respir. Med. 212, 107221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107221 (2023).

Kamenski, G. et al. Does COPD have a clinically relevant impact on hearing loss? A retrospective matched cohort study with selection of patients diagnosed with COPD. BMJ Open. 5, e008247, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008247 (2015).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 61–68, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys203 (2014).

Huang, C. & He, X. Association between sensory impairment and sarcopenia in older Chinese adults: a 4-year longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 25, 90, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05642-6 (2025).

Yang, H. et al. Associations between pulmonary function and depression: evidence from the CHARLS cohort 2015-2018. Front. Public. Health 13, 1551356. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1551356 (2025).

Jiang, G., Feng, L., Qu, X., Wang, J. & Li, Y. Inverted L-shape association between a body shape index and peak expiratory flow among middle-aged and older adults: findings from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Lipids Health Dis. 24, 181, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-025-02599-2 (2025).

Wang, K., Jia, S., Zhao, W., Ge, M. & Dong, B. The creatinine-to-cystatin C ratio (a surrogate marker of muscle mass) as a predictor of lung function decline in older adults: a nationwide longitudinal study in China. Respir. Med. 211, 107197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107197 (2023).

Yan, J. M., Zhang, M. Z., Yu, H. J. & He, Q. Q. Residential greenness, air pollution and visual impairment: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public. Health 24, 3332. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20853-7 (2024).

Rong, H. et al. Association of sensory impairments with cognitive decline and depression among older adults in China. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e2014186, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14186 (2020).

Bikbov, M. M. et al. Prevalence factors associated with vision impairment and blindness among individuals 85 years and older in Russia. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e2121138, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21138 (2021).

Bovo, R., Ciorba, A. & Martini, A. Environmental and genetic factors in age-related hearing impairment. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 23, 3–10, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03324947 (2011).

Eid, H. A. et al. Auditory function assessment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. SAGE Open. Med. 11, 20503121231216212, https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121231216212 (2023).

Jian, W. et al. Reference values for spirometry in Chinese aged 4-80 years. J. Thorac. Dis. 9, 4538–4549, https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017.10.110 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. The relationship between lung function and cognitive impairment among middle-aged and older adults: the mediating role of depressive symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 193, 112148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2025.112148 (2025).

Mukai, H. et al. Restrictive lung disorder is common in patients with kidney failure and associates with protein-energy wasting, inflammation and cardiovascular disease. PLoS One 13, e0195585, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195585 (2018).

Mamyrbekova, S. et al. The diagnostic accuracy of spirometry versus peak expiratory flow test for follow-up of adult asthma patients at primary care level. Allergy Asthma Proc. 43, e58–e64, https://doi.org/10.2500/aap.2022.43.220049 (2022).

Solberg, Y., Rosner, M. & Belkin, M. The association between cigarette smoking and ocular diseases. Surv. Ophthalmol. 42, 535–547, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-6257(98)00002-2 (1998).

Makrynioti, D., Zagoriti, Z., Koutsojannis, C., Morgan, P. B. & Lagoumintzis, G. Ocular conditions and dry eye due to traditional and new forms of smoking: a review. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye. 43, 277–284, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2020.02.009 (2020).

Prabhu, P., Varma, G., Dutta, K. K., Kumar, P. & Goyal, S. Influence of smoking on ultra-high-frequency auditory sensitivity. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 13, 110–112, https://doi.org/10.5152/iao.2017.3412 (2017).

Pezzoli, M. et al. Effects of smoking on eustachian tube and hearing. Int. Tinnitus J. 21, 98–103, https://doi.org/10.5935/0946-5448.20170019 (2017).

Chang, J. et al. Effect of cigarette smoking and passive smoking on hearing impairment: data from a population-based study. PLoS One 11, e0146608, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146608 (2016).

Ojaghi, H., Poorsheykhian, S., Najafi, A. & Iranpour, S. The role of blood related inflammatory factors on age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Immun. Ageing 21, 35, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12979-024-00440-5 (2024).

Kim, C. et al. Ischemia as a potential etiologic factor in idiopathic unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss: analysis of posterior circulation arteries. Hear. Res. 331, 144–151, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2015.09.003 (2016).

Ogawa, H., Okada, M., Shudou, M., Gyo, K. & Hato, N. Prevention of ischemia-induced hearing loss by intravenous administration of hydrogen-rich saline in gerbil. Neurosci. Lett. 665, 195–199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2017.12.013 (2018).

Park, D. J. et al. Induced short-term hearing loss due to stimulation of age-related factors by intermittent hypoxia, high-fat diet, and galactose injection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7068, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21197068 (2020).

Fan, D., Ren, H., Danzeng, D., Li, H. & Wang, P. Influence of high-altitude hypoxic environments on the survival of cochlear hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons in rats. Biomed. Rep. 5, 681–685, https://doi.org/10.3892/br.2016.791 (2016).

Watson, N., Ding, B., Zhu, X. & Frisina, R. D. Chronic inflammation - inflammaging - in the ageing cochlea: a novel target for future presbycusis therapy. Ageing Res. Rev. 40, 142–148, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2017.10.002 (2017).

Atiş, S., Ozge, A. & Sevim, S. The brainstem auditory evoked potential abnormalities in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology 6, 225–229, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1843.2001.00337.x (2001).

Luo, Y., Ma, X., Zhang, L. & He, W. Association of handgrip strength weakness and asymmetry with low physical performance among Chinese older people. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 36, 225, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02886-5 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors also thank all involved laboratory technicians for their help with data collection and analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei-Zhen Tang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft; Ting-He Sheng: Validation, Visualization; Hong-Yu Xu: Visualization; Qin-Yu Cai: Supervision; Zhi-Jian Zhou: Investigation; Xue-Bing Chen: Validation, Visualization; Yi-Han Yang: Investigation; Tai-Hang Liu: Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing; Yongheng Wang: Software, Resources, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent.

Approval committee or the internal review board

The CHARLS study protocol has been approved by the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052–11015). All participants provided informed consent prior to data collection.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, WZ., Sheng, TH., Xu, HY. et al. The association between lung function and sensory impairments among chinese middle-aged and older adults: a longitudinal cohort study from CHARLS. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35, 41 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00446-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00446-6