Abstract

Fault-tolerant quantum computing (FTQC) is essential for achieving large-scale practical quantum computation. Implementing arbitrary FTQC requires the execution of a universal gate set on logical qubits, which is highly challenging. Particularly, in the superconducting system, two-qubit gates on surface code logical qubits have not been realized. Here, we experimentally implement a logical CNOT gate along with arbitrary single-qubit rotation gates on distance-2 surface codes using the superconducting quantum processor Wukong, thereby demonstrating a universal logical gate set. In the experiment, we demonstrate the transversal CNOT gate on a two-dimensional topological processor based on a tailored encoding circuit, at the cost of removing the ancilla qubits required for stabilizer measurements. Furthermore, we fault-tolerantly prepare logical Bell states and observe a violation of CHSH inequality, confirming the entanglement between logical qubits. Using the logical CNOT gate and an ancilla logical state, arbitrary single-qubit rotation gates are realized through gate teleportation. All logical gates are characterized on a complete state set and their fidelities are evaluated by logical Pauli transfer matrices. The demonstration of a universal logical gate set and the entangled logical states highlights significant aspects of FTQC on superconducting quantum processors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum computing holds the promise to accelerate classical computing in various applications such as large number factorization1, quantum simulation2, and machine learning3. However, physical qubits are typically very fragile and are easily disturbed by environmental noise. To address the noise issues in large-scale quantum computing, quantum error correction techniques have been proposed, which introduce redundant information and encode quantum states onto logical qubits to ensure fault tolerance4,5,6.

In recent years, multiple experiments across various quantum computing platforms have demonstrated the memory of quantum information on logical qubits. These experiments are based on hardware systems encompassing superconducting7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, ion trap16,17, neutral atom18, and other systems19,20,21,22,23. Particularly in experiments using bosonic codes, it has been demonstrated that the quality of logical qubits can exceed the so-called break-even point21,22, validating the effectiveness of quantum error correction techniques in suppressing quantum noise.

Furthermore, to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computing (FTQC), a set of logical gates needs to be implemented. The simplest approach to implement logical gates is transversally, where all physical qubits have interacted with at most one physical qubit from each logical block, therefore naturally ensuring fault-tolerance. However, a well-known theorem states that no quantum code can simultaneously promise a transversal and universal logical gate set24,25,26. For instance, in the surface code, the CNOT gate is transversal. While some single-qubit rotation gates, such as the S gate and T gate, typically need to be implemented indirectly using gate teleportation circuits with ancilla logical states27,28.

Currently, more and more experimental works are focusing on demonstrations of logical gates of various quantum error correction codes12,14,18,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. For instance, in neutral atom systems, demonstrations of the CNOT, CZ, and CCZ gates have been achieved on the [8,3,2] color code18. In ion trap systems, the H, S, T, and CNOT gates have been demonstrated on the Steane code30, forming a universal gate set. In superconducting systems, experimental demonstrations of logical gates remain limited, particularly for the surface code, which is the most promising encoding scheme due to its high theoretical threshold and practical nearest-neighbor connectivity requirements28,38. Ref. 31 demonstrated a universal set of single-qubit gates on the distance-2 surface code in superconducting systems, showing the potential of using surface code logical qubits for FTQC in the superconducting quantum processor. The main limitation of their work is the lack of two-qubit logical operations, thus not constituting a complete universal gate set. Additionally, the ancilla quantum states used in gate teleportation are physical states rather than logical states, which is inconsistent with the requirements in FTQC. To the best of our knowledge, no work has yet implemented a complete universal set of logical gates in either the superconducting system or the surface code encoding.

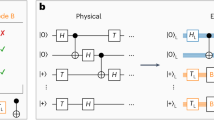

In our work, we use the error-detecting surface code with distance 2 (Fig. 1a) to implement a complete set of universal logical gates, including arbitrary single-qubit rotations around the Z or X axis and the CNOT gate, filling the gap in current literature. In the experiment, we encode two logical qubits in a 2 × 4 qubit region of the superconducting quantum processor Wukong (see Fig. 1b and Supplementary Note 1). The logical CNOT gate is implemented transversally, i.e., by performing four CNOT gates between the corresponding physical qubits. Additionally, single-qubit rotation gates are implemented by preparing the ancilla logical states and applying gate teleportation circuit, which consists of a logical CNOT gate and logical X or Z measurement on the ancilla qubit. To implement transversal CNOT gates on a two-dimensional topology, our design has to simplify the encoding of two logical qubits by removing the measurement qubits required for stabilizer measurements. The error detection in our experiment is achieved through measurement and post-selection at the end of the circuit. While no stabilizer measurements are performed after logical operations, any single error can still be detected in fault-tolerant circuits by reconstructing the stabilizers from the terminal measurement results.

a Two logical qubits of the distance-2 surface code and transversal CNOT gate. Each logical qubit is encoded by four data qubits and the logical CNOT gate between two logical qubits corresponds to the four physical CNOT gates between the corresponding data qubits. b The experiment uses eight physical qubits arranged in a 2 × 4 rectangular region on the superconducting quantum processor Wukong. The deep blue lines represent the topology of the processor, indicating the allowed two-qubit gates between physical qubits.

The logical Pauli transfer matrices (LPTMs) of these logical gates are characterized on a complete set of states, according to which the gate fidelities are evaluated and listed in Table 1. Using fault-tolerant logical state encoding circuits and transversal CNOT gates, four logical Bell states are also prepared. By verifying the violation of the CHSH inequality with these Bell states, we have confirmed the presence of quantum entanglement between two logical qubits. In the experiment, all fault-tolerantly prepared logical states, including single-qubit states and Bell states, exhibit higher fidelity than the results on the corresponding physical qubits (see Table 2).

Note that the fidelity referred to here is the overall fidelity of the preparation and characterization process, therefore, it does not indicate that a logical state beyond the break-even point has been achieved. However, as hardware improves, the logical error rate of error detection codes could exceed the breakeven point, as indicated by some theoretical and experimental work using error detection codes in the context of early fault-tolerant computing39,40.

Moreover, in the long term, the demonstration of transversal CNOT gates on surface codes could support more efficient FTQC. Theoretical works suggest that combining transversal CNOT gates with two-dimensional (2-D) operations has the potential to reduce the space-time overhead of FTQC on surface codes41,42. However, we recognize that this may be a rather distant goal for superconducting systems, as the transversal CNOT gate for surface codes typically requires a multi-layer architecture or a 2-D architecture with long-distance couplings43,44,45,46. Nonetheless, our experiment provides an early exploration for these intriguing applications.

Results

Logical state preparation and measurement

The logical qubit of distance-2 surface code is encoded on four data qubits and is capable of detecting any single-qubit errors. Its code space is the +1 eigenspace of the following stabilizer group:

Then the logical Pauli operators are defined as:

Accordingly, the explicit form of the logical state can be written as:

and

Here, we designed circuits for preparing the logical states \(\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert {1}_{L}\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {-}_{L}\right\rangle\) fault-tolerantly (see Fig. 1), whose fault tolerance is proven in the Methods. In this error-detection context, an operation is fault-tolerant if any single error produces a non-trivial syndrome and can therefore be post-selected out. In order to simultaneously ensure fault-tolerant state preparation and transversal CNOT gate implementation between \(\left\vert {\pm }_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 0/{1}_{L}\right\rangle\) states, we adopt the qubit allocation scheme depicted in Fig. 2a and b. The key is that we exploit the property that \(\left\vert {\pm }_{L}\right\rangle\) can be decomposed into product states (\(\left\vert {\pm }_{L}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{2}{(\left\vert 00\right\rangle \pm \left\vert 11\right\rangle )}^{\otimes 2}\)), and encode \(\left\vert {\pm }_{L}\right\rangle\) on the leftmost two (q1 and q5) and the rightmost two physical qubits (q4 and q8) in the hardware. Moreover, we also provide a circuit for preparing arbitrary logical state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{L}\right\rangle\) in Fig. 2c. Generally, such a circuit for encoding arbitrary logical state is not fault-tolerant, nor is this circuit. In this way, a logical state can be encoded on a chain of four physical qubits (q1-q4) with only nearest-neighbor coupling.

a, b Circuits for fault-tolerant (FT) preparation of \(\left\vert 0/{1}_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\pm }_{L}\right\rangle\) states. The \(\left\vert {1}_{L}\right\rangle\) (or \(\left\vert {-}_{L}\right\rangle\)) state are obtained by applying XL (or ZL) gate after preparing the \(\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle\) (or \(\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle\)) state. c Circuits for non-fault-tolerant (nFT) preparation of arbitrary logical state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{L}\right\rangle\). d–f Density matrices and fidelities of the six single logical states prepared in the experiment. All logical state density matrices are obtained through logical state tomography. g Comparison of fidelity and post-selection (PS) rates between experiments and simulations. The figure shows the fidelity of six logical states and the post-selection rates when measuring their eigenoperators (ZL or XL).

After preparing the logical states, logical X, Y, or Z measurements are performed to characterize these states. Their measurement results are determined by the product of the corresponding Pauli operator measurement result on each data qubits. The logical X and Z measurements are fault-tolerant and correspond to measurements in the X and Z bases on all data qubits, respectively. Post-selection is carried out based on the conditions provided by the three generators of the stabilizer group, discarding results that violate these conditions. Specifically, assuming the X or Z measurement result on the ith data qubit is \({m}_{i}^{x}\) or \({m}_{i}^{z}\in \{+1,-1\}\) the post-selection conditions are \({m}_{1}^{x}{m}_{2}^{x}{m}_{3}^{x}{m}_{4}^{x}=+1\), and \({m}_{1}^{z}{m}_{2}^{z}=+1\), \({m}_{3}^{z}{m}_{4}^{z}=+1\) for logical X and Z measurements, respectively. On the other hand, measurement of the logical Y operator YL = Z1Y3X4 is not fault-tolerant. It requires Z measurements on data qubits D1 and D2, a Y measurement on D3, and an X measurement on D4. The corresponding post-selection condition is \({m}_{1}^{z}{m}_{2}^{z}=+1\). In this case, post-selection cannot eliminate all single-qubit error cases but can suppress some of them. Define the probability of successfully passing the post-selection condition as the post-selection rate. Since the post-selection conditions vary under different measurement bases, the post-selection rate is significantly influenced by the measurement basis.

Here, we conduct experimental demonstrations and characterizations on the fault-tolerantly prepared \(\left\vert 0/{1}_{L}\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert {\pm }_{L}\right\rangle\) states, and non-fault-tolerantly prepared \(\left\vert 0/{1}_{L}\right\rangle\) states. Through logical quantum state tomography, we constructed the density matrix ρL in the code space, as shown in Fig. 2d–f. Furthermore, we computed the fidelity of the logical state:

where \(\left\vert {\psi }_{L}\right\rangle\) is the ideal logical quantum state. The fidelities of the fault-tolerantly prepared states \(\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {1}_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {-}_{L}\right\rangle\), as well as the non-fault-tolerantly prepared states \(\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {1}_{L}\right\rangle\), are 97.9(2)%, 98.0(2)%, 97.7(2)%, 97.8(2)%, 89.2(3)%, and 88.9(3)%, respectively. We also computed the fidelities of the \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle ,\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert +\right\rangle ,\left\vert -\right\rangle\) states prepared on the eight physical qubits in the experiment using physical state tomography. For a fair comparison, we did not use readout error mitigation techniques47 during the physical state tomography. The highest values among eight physical qubits are 96.9(3)% for \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) in q2, 94.8(4)% for \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\) in q2, 93.6(5)% for \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\) in q2 and 90.8(6)% for \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\) in q3. All these values are lower than the fidelities of the fault-tolerantly prepared logical states, demonstrating the noise-suppressing effect in the overall process of the preparation and characterization. However, we remind readers that the fidelities of logical or physical states also affected by noise in the tomography protocol. Due to the difficulty in distinguishing noise in characterization from noise in state preparation, these results do not imply that the fidelity of logical state preparation exceeds that of the physical state. Especially given the significant readout noise on our superconducting processor, the contribution of error detection to the improvement in readout fidelity is likely more substantial.

In addition, we provide information on the post-selection rates when measuring the logical state eigenoperators in Fig. 2e (see Supplementary Note 3 for complete data on the post-selection rate). We also present simulation results for comparison, which are based on the Pauli depolarizing noise model, a commonly used error model in quantum error correction research (see details in Supplementary Note 4). However, we also remark that this model does not fully capture the real noise, leading to discrepancies between experimental and simulated data.

Logical CNOT gate and Bell states

Next, our experiment demonstrates a transversal CNOT gate between two surface code logical qubits (see Fig. 3a and b). Initially, two logical states \(\left\vert {\psi }_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\varphi }_{L}\right\rangle\), are prepared on two chains of the quantum processor (q1-q4 and q5-q8), where \(\left\vert {\psi }_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\varphi }_{L}\right\rangle\) are from a complete state set \(\{\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {-}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {i}_{L}\right\rangle \}\). Here \(\left\vert {i}_{L}\right\rangle =(\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle +i\left\vert {1}_{L}\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) is the +1 eigenstate of the logical operator YL. This step is realized by the preparation circuit for arbitrary logical states described in the previous section. Since the fidelity of states \(\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {-}_{L}\right\rangle\) in our experiment is higher, we prioritize selecting these two states to form the complete state set. The density matrices of the initial logical states are characterized by logical state tomography. Subsequently, a transversal CNOT gate is applied to the initial logical states, and the output states are characterized using logical state tomography. Based on the expectation values of two-qubit Pauli operators of the initial and output states, we extract the LPTMs using the method presented in ref. 31. The fidelity of the logical CNOT gate, as computed from the LPTM, is found to be \({F}_{L}^{G}=88.9(5) \%\). Details concerning the LPTM and fidelity calculation are presented in Supplementary Note 2. Due to the noise in the characterization, this result is actually a conservative estimate of the logical gate fidelity.

a Circuit of the logical CNOT gate implemented transversally. b, c Circuit for applying a logical CNOT gate on arbitrary logical states \(\left\vert {\psi }_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\varphi }_{L}\right\rangle\), and the circuit for fault-tolerant preparation of Bell states, respectively. The blocks represent logical state preparation circuits and the logical CNOT gate. The upper half of the logical CNOT block corresponds to the control logical qubit, while the lower half corresponds to the target logical qubit. d Density matrices and fidelities of the four logical Bell states prepared fault-tolerantly in the experiment. e Average fidelity and post-selection (PS) rates of four logical Bell states when measuring XL ⊗ XL, YL ⊗ YL and ZL ⊗ ZL in experiments and simulations.

Then we use the logical CNOT gate to prepare four Bell states on logical qubits, which are important entangled resources in quantum information. Following the above initialization method, the control and target logical qubits can be initialized to \(\left\vert {\pm }_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert 0/{1}_{L}\right\rangle\) states, respectively. Then they can be acted by a logical CNOT gate to generate a Bell state. However, under such qubit allocation, the prepared \(\left\vert 0/{1}_{L}\right\rangle\) state is not fault-tolerant. Therefore, we adopt the qubit allocation scheme from the previous section to simultaneously fault-tolerantly prepare the \(\left\vert 0/{1}_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\pm }_{L}\right\rangle\) states (see Fig. 3c). This circuit can be viewed as a special planarization of a two-layer architecture. In this layout, all physical CZ gates required in both the logical state preparation and the transversal CNOT gate implementation are 2-D hardware-neighbor. We reconstruct the density matrix of the logical Bell states in Fig. 3d. The overall fidelities in the preparation and characterization for the four logical Bell states are 79.5(5)%, 79.5(5)%, 79.4(5)%, and 79.4(5)%, respectively. We also report the post-selection rates for Bell states under X ⊗ X, X ⊗ X, Z ⊗ Z measurements along with a comparison between simulated and experimental data in Fig. 3e. Correspondingly, we prepare four physical Bell states by physical CNOT gate on qubits q6 and q7. The fidelity of the CNOT gate between q6 and q7 is the highest among all physical CNOT gates in the experiment. The fidelities for the four physical Bell states are 74.4(9)%, 74.2(9)%, 74.5(9)%, and 74.2(9)%, respectively, all of which are lower than the fidelity of the fault-tolerantly prepared logical Bell states.

To confirm entanglement between the two surface code logical qubits, we verify a variant of the CHSH inequality48. For a two-qubit density matrix ρ, define the matrix Tρ with elements \({({T}_{\rho })}_{ij}={\rm{Tr}}(\rho {P}_{i}\otimes {P}_{j})\), where Pi ∈ {X, Y, Z}. A necessary and sufficient condition for violating the CHSH inequality is u1 + u2 > 1, where u1 and u2 are the two largest eigenvalues of the matrix \({T}_{\rho }^{T}{T}_{\rho }\). In our experiment, the values of u1 + u2 for the four logical Bell states are 1.55, 1.55, 1.54, and 1.54, respectively. This result confirms the presence of quantum entanglement between the two surface code logical qubits.

Logical single-qubit rotation

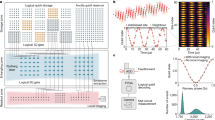

Finally, we demonstrated logical single-qubit rotations around the Z or X axis based on gate teleportation circuit (Fig. 4a). More specifically, these rotation operations are

where θ is the rotation angle. The gate teleportation circuit consists of three parts. First, preparing the ancilla states

Then the logical CNOT gate is applied, and finally, ancilla state is measured in logical Z or X basis. The RZ(θ) or RX(θ) gate is successfully executed only when the logical Z or X measurement results in +1; otherwise, operation RZ(2θ) or RX(2θ) needs to be applied as a compensation. Here, we simply use the post-selection strategy, that is, only retaining the cases where the measurement result is +1. Note that the ancilla states can be viewed as the result of applying RZ(θ) or RX(θ) gates to \(\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle\) or \(\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle\), respectively, that is why we refer to this circuit as gate teleportation circuit.

a Gate teleportation circuits that implement single-qubit rotation operations on logical qubits. The ± sign of the rotation angle depends on the measurement results of the ancilla logical states. b, c Circuits for applying single-qubit rotations RZ(θ) and RX(θ) on the logical state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{L}\right\rangle\) based on gate teleportation, respectively. d, e Average values of Pauli operators and fidelity of the ancilla logical states \(\left\vert {\theta }_{L}^{z}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\theta }_{L}^{x}\right\rangle\) with rotation angles θ ∈ (−π, π], respectively. Scatter points and solid lines are used to distinguish experimental and simulated data. f, g Average values of Pauli operators and fidelity of the output states \({R}_{Z}(\theta )\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle\) or \({R}_{X}(\theta )\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle\) with rotation angles θ ∈ (−π, π], respectively.

In the experiment, we first prepare the required ancilla logical states \(\left\vert {\theta }_{L}^{z}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\theta }_{L}^{x}\right\rangle\) with θ ∈ (−π, π] on a chain of the quantum processor (q1-q4). Then these input states are measured in XL, YL or ZL basis to obtain the expectation values of the logical Pauli operators. Subsequently, we execute the circuits in Fig. 4b, c, demonstrating the single-qubit rotation gates around the Z or X axis on the state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{L}\right\rangle =\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle\) or \(\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle\), respectively. The expectation values of the logical Pauli operators for the input and output states are shown in Fig. 4d–g. Using the expectation values 〈X〉, 〈Y〉, 〈Z〉, we reconstructed the density matrices, thereby calculating the fidelity of each state. The average fidelities of input states \(\left\vert {\theta }_{L}^{z}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\theta }_{L}^{x}\right\rangle\) are evaluated to be 89.0(3)%. Correspondingly, the average fidelities of the output states are 78.0(9)% and 75.0(9)%, respectively.

To characterize the fidelity of the single-qubit logical gates, it is required to construct the LPTMs of these gates. Here, we test the LPTMs of RZ(θ) and RX(θ) with θ ∈ {0, π/4, π/2, π} as examples. The input states are encoded as the logical states from the set \(\{\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {-}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {i}_{L}\right\rangle \}\), and the above logical gates are applied separately. We measure the expectation values of the Pauli operators for the input and output states and construct the LPTMs for these eight logical gates accordingly (see Supplementary Note 2). The fidelities \({F}_{L}^{G}\) of these eight logical gates are estimated to be 94.4(5)%, 90.0(7)%, 87.4(7)%, 93.9(5)%, 92.1(6)%, 90.7(7)%, 89.6(7)%, 92.4(6)%, respectively.

Discussion

This work experimentally demonstrates a complete universal set of logical gates on distance-2 surface code in a superconducting processor. Particularly, logical Bell states that violates CHSH inequality have been fault-tolerantly prepared using the transversal CNOT gate. Based on the logical CNOT gate, the gate teleportation process is experimentally demonstrated to implement single-qubit rotation operations. These results reveal several significant aspects of FTQC based on the surface code in superconducting hardware.

The fidelity of logical operations are in the experiment is affected by a variety of factors. The dominant noise of our superconducting processor is the readout noise and two-qubit gate noise. Through numerical simulations, we found that the performance of logical circuits in our experiment is more sensitive to readout errors compared to gate errors. The Supplementary Note 4 presents the results of these numerical simulations and discusses the mechanisms underlying various types of noise as well as potential approaches for improvement. In addition, in the implementation of single-qubit rotation gates, the fidelity of the logical gates largely depends on the quality of the ancilla logical states in the gate teleportation circuit. In our experiment, the ancilla logical states are generated by non-fault-tolerant preparation circuits, resulting in a relatively high error rate. In a complete FTQC framework, high-fidelity ancilla logical states are typically obtained through state distillation27,49,50,51. A particularly challenging future task is to experimentally demonstrate these distillation protocols.

In our experiment, logical qubits are confined to a one-dimensional structure without measurement qubits. A natural extension is to incorporate the repeated stabilizer measurement process into our work. Achieving both the stabilizer measurement process and transversal CNOT gate typically requires a multi-layer structure or long-range entangling gates (see Supplementary Note 6). For superconducting platforms, this is regarded as a challenging long-term goal. However, we are also excited to see that they are increasingly gaining attention due to the requirements in FTQC52,53,54. Meanwhile, some prototypes of these technologies have been demonstrated recently43,44,45,46,55, indicating that they are not beyond reach.

In conclusion, our experiment enriches the possibilities for research in FTQC. First, from a near-term perspective, our work demonstrates the role of error detection codes or small-distance error-correction codes in the early FTQC era. Notably, the performance of some logical circuits in the experiment surpassed that of physical circuits. Numerical simulations further indicate that the pseudo-threshold of the experimental circuits can significantly exceed the fault-tolerant threshold (approximately 1%, see Supplementary Note 4). Second, on superconducting platforms with planar nearest-neighbor connectivity, lattice surgery is the mainstream method for logical operations56,57,58. Demonstrating transversal CNOT gates supports a hybrid scheme combining them with lattice surgery, potentially reducing the significant overhead of FTQC41,42. We have elaborated on the feasibility and benefits of this architecture in the Supplementary Note 6. Achieving this requires extending the experimental qubit layout to a multi-layer structure, which remains a long-term goal for superconducting platforms.

Methods

Fault-tolerant logical state preparation

Here, we prove that the circuits in the first two parts of Fig. 2a and b are fault-tolerant, meaning that a single-qubit error occurring at any position in the circuit can be detected without leading to a logical error. To clarify this, we note that there are two types of errors to consider: those that remain localized in a single qubit and are thus detectable by the stabilizers, and those that might affect the final state of more than one qubit. We focus on the latter type of errors, ensuring that they do not spread to become logical errors. For ease of discussion, we combine the H gates and CZ gates in the circuit into CNOT gates, focusing on the preparation of the \(\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle\) states, resulting in the circuit shown in Fig. 5. This simplification does not affect the fault-tolerance of the original circuits.

The circuits are simplified to a composition of CNOT and H gates, with fault tolerance equivalent to the original circuits. The possible X (blue) or Z (yellow) errors that could propagate are shown. a Fault-tolerant (FT) preparation circuit for \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\). b Fault-tolerant (FT) preparation circuit for \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\).

For the \(\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle\) state preparation circuit, we only need to consider the Pauli X errors in the circuit, as any logical ZL error produced is trivial for the \(\left\vert 0/{1}_{L}\right\rangle\) state up to a global phase. We mark the locations of all possible single-qubit Pauli X errors (shown as blue X in Fig. 5a). The leftmost X error affects qubits 1 through 4 as X1X2X3X4, which is a stabilizer. The second and third X errors affect qubits 2 and 3 as X2X3 and qubits 1 and 4 as X1X4, respectively. These errors anti-commute with the stabilizers Z1Z2 and Z3Z4, and thus they will be detected by the stabilizer measurements. This proves that no single-qubit Pauli X error at any position in the circuit can spread to become a logical XL error.

Similarly, in the \(\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle\) state preparation circuit, we consider the possible Pauli Z errors. The two possible spreading Pauli Z errors (yellow Z in Fig. 5b) affect qubits 1 and 2 as Z1Z2 and qubits 3 and 4 as Z3Z4, which are the two stabilizers of this code. Since all these errors can be detected or lead to a stabilizer operator, we have demonstrated the fault-tolerance of these two encoding circuits.

Logical Pauli transfer matrix (LPTM)

The Pauli transfer matrix (PTM) describes a quantum process on the components of the density matrix represented in the basis of Pauli operators6,59,60,61. For a d-dimensional Hilbert space, a PTM \({\mathcal{R}}\) is a linear transformation matrix from the expectation values pi = 〈Pi〉 of the Pauli operators Pi in the input state to the expectation values \({p}_{j}^{{\prime} }\) in the output state:

In our experiment, Pi belongs to \({\{{I}_{L},{X}_{L},{Y}_{L},{Z}_{L}\}}^{\otimes 2}\) and {IL, XL, YL, ZL} for the cases d = 4 and d = 2, respectively. To construct the LPTMs of the logical quantum gates in the main text, we use input states from the complete set \({\{\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {-}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {i}_{L}\right\rangle \}}^{\otimes 2}\) (for the logical CNOT gate) or \(\{\left\vert {+}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {-}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {0}_{L}\right\rangle ,\left\vert {i}_{L}\right\rangle \}\) (for the logical single-qubit gates). The density matrices of the input and output states are obtained through logical state tomography, and the expectation values pi and \({p}_{j}^{{\prime} }\) are then calculated. The inverse of the expectation value matrix yields the raw result \({{\mathcal{R}}}^{{\rm{raw}}}\). However, \({{\mathcal{R}}}^{{\rm{raw}}}\) may not satisfy the conditions of a physical channel, i.e., being completely positive and trace-preserving6. Therefore, using the techniques in ref. 31, \({{\mathcal{R}}}^{{\rm{raw}}}\) is transformed into the Choi state representation:

We then optimize ρ under the following objective function and constraints:

where \({{\rm{Tr}}}_{1}\) is the partial trace over the left half subsystem. Using the convex optimization package cvxpy, we obtain the optimal result ρopt. The corresponding LPTM \({\mathcal{R}}\) is

and the fidelity of the logical gate is

where \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{ideal}}}\) is the ideal LPTM of the logical gate?. In our experiment, we constructed the LPTMs for the logical CNOT gate and eight logical single-qubit gates. The specific details of these LPTMs can be found in the Supplementary Note 2.

Quantum state tomography

Quantum state tomography62,63,64 reconstructs the density matrix of an unknown quantum state by measuring some observables. In our experiment, we measure 4n − 1 Pauli operators of the logical qubits, where n is the number of logical qubits. Assuming the expectation values of these Pauli operators are pi = 〈Pi〉, where \({P}_{i}\in {\{{I}_{L},{X}_{L},{Y}_{L},{Z}_{L}\}}^{\otimes n}/\{{I}_{L}^{\otimes n}\}\), the density matrix is reconstructed as:

with p0 = 1 and \({P}_{0}={I}_{L}^{\otimes n}\). Such a density matrix ρL,0 may not satisfy the physicality characteristics of a quantum state. Therefore, we use maximum likelihood estimation65,66 to construct the logical density matrix ρL. Specifically, the objective function to minimize is

subject to \({\rm{Tr}}({\rho }_{L})=1\), and ρL ≥ 0. This process is implemented also using the convex optimization package cvxpy. Likewise, we also apply state tomography to physical states for constructing the density operators of states \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert 1\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert +\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert -\right\rangle\) and four Bell states, which is done for comparison with the logical state density matrices. These results are shown in the Supplementary Note 2.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Shor, P. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proc. 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 124–134 (IEEE, 1994).

Freedman, M. H., Kitaev, A. & Wang, Z. Simulation of topological field theories by quantum computers. Commun. Math. Phys. 227, 587–603 (2002).

Biamonte, J. et al. Quantum machine learning. Nature. 549, 195–202 (2017).

Preskill, J. Reliable quantum computers. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 454, 385–410 (1998).

Gottesman, D. Stabilizer Codes and Quantum Error Correction (California Institute of Technology, 1997).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L.Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Andersen, C. K. et al. Repeated quantum error detection in a surface code. Nat. Phys. 16, 875–880 (2020).

Google Quantum AI. Exponential suppression of bit or phase errors with cyclic error correction. Nature. 595, 383–387 (2021).

Krinner, S. et al. Realizing repeated quantum error correction in a distance-three surface code. Nature. 605, 669–674 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Realization of an error-correcting surface code with superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 030501 (2022).

Google Quantum AI. Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit. Nature. 614, 676–681 (2023).

Hetényi, B, Wootton, J. R. Creating entangled logical qubits in the heavy-hex lattice with topological codes. PRX Quantum 5, 040334 (2024).

Acharya, R. et al. Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. Nature. 638, 920–926 (2024).

Lacroix, N. et al. Scaling and logic in the color code on a superconducting quantum processor. Nature. 645, 614–619 (2025).

Eickbusch, A. et al. Demonstrating dynamic surface codes https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.14360 (2024).

da Silva, M. et al. Demonstration of logical qubits and repeated error correction with better-than-physical error rates. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.02280 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.02280 (2024).

Ryan-Anderson, C. et al. Realization of real-time fault-tolerant quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. X. 11, 041058 (2021).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature. 626, 58–65 (2024).

Campagne-Ibarcq, P. et al. Quantum error correction of a qubit encoded in grid states of an oscillator. Nature. 584, 368–372 (2020).

Gertler, J. M. et al. Protecting a bosonic qubit with autonomous quantum error correction. Nature. 590, 243–248 (2021).

Sivak, V. et al. Real-time quantum error correction beyond break-even. Nature. 616, 50–55 (2023).

Ni, Z. et al. Beating the break-even point with a discrete-variable-encoded logical qubit. Nature. 616, 56–60 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Protecting entanglement between logical qubits via quantum error correction. Nat. Phys. 1–5 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-024-02446-8 (2024).

Eastin, B. & Knill, E. Restrictions on transversal encoded quantum gate sets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 110502 (2009).

Chen, X., Chung, H., Cross, A. W., Zeng, B. & Chuang, I. L. Subsystem stabilizer codes cannot have a universal set of transversal gates for even one encoded qudit. Phys. Rev. A 78, 012353 (2008).

Zeng, B., Cross, A. & Chuang, I. L. Transversality versus universality for additive quantum codes. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 57, 6272–6284 (2011).

Bravyi, S. & Kitaev, A. Universal quantum computation with ideal clifford gates and noisy ancillas. Phys. Rev. A. 71, 022316 (2005).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M. & Cleland, A. N. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A. 86, 032324 (2012).

Hu, L. et al. Quantum error correction and universal gate set operation on a binomial bosonic logical qubit. Nat. Phys. 15, 503–508 (2019).

Postler, L. et al. Demonstration of fault-tolerant universal quantum gate operations. Nature 605, 675–680 (2022).

Marques, J. F. et al. Logical-qubit operations in an error-detecting surface code. Nat. Phys. 18, 80–86 (2022).

Ryan-Anderson, C. et al. Implementing fault-tolerant entangling gates on the five-qubit code and the color code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.01863 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2208.01863 (2022).

Abobeih, M. H. et al. Fault-tolerant operation of a logical qubit in a diamond quantum processor. Nature 606, 884–889 (2022).

Menendez, D. H., Ray, A. & Vasmer, M. Implementing fault-tolerant non-clifford gates using the [8, 3, 2] color code. Phys Rev A 109, 062438 (2024).

Shaw, M. H., Doherty, A. C. & Grimsmo, A. L. Logical gates and read-out of superconducting gottesman-kitaev-preskill qubits. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.02396 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-018-0414-3 (2024).

Yifei, W. et al. Efficient fault-tolerant implementations of non-clifford gates with reconfigurable atom arrays. Npj Quantum Inf. 10, 136 (2024).

Besedin, I. et al. Realizing lattice surgery on two distance-three repetition codes with superconducting qubits https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.04612 (2025).

Wang, D. S., Fowler, A. G. & Hollenberg, L. C. L. Surface code quantum computing with error rates over 1%. Phys. Rev. A 83, 020302 (2011).

Self, C. N., Benedetti, M. & Amaro, D. Protecting expressive circuits with a quantum error detection code. Nat. Phys. 20, 219–224 (2024).

Ginsberg, T. & Patel, V. Quantum error detection for early term fault-tolerant quantum algorithms https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.10790 (2025).

Cai, Z., Siegel, A. & Benjamin, S. Looped pipelines enabling effective 3d qubit lattices in a strictly 2d device. PRX Quantum 4, 020345 (2023).

Viszlai, J., Lin, S. F., Dangwal, S., Baker, J. M. & Chong, F. T. An architecture for improved surface code connectivity in neutral atoms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.13507 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.13507 (2023).

Rosenberg, D. et al. 3d integrated superconducting qubits. npj Quantum Inf. 3, 42 (2017).

Yost, D.-R. W. et al. Solid-state qubits integrated with superconducting through-silicon vias. npj Quantum Inf. 6, 59 (2020).

Rosenberg, D. et al. Solid-state qubits: 3d integration and packaging. IEEE Microw. Mag. 21, 72–85 (2020).

Gold, A. et al. Entanglement across separate silicon dies in a modular superconducting qubit device. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 142 (2021).

Nation, P. D., Kang, H., Sundaresan, N. & Gambetta, J. M. Scalable mitigation of measurement errors on quantum computers. PRX Quantum. 2, 040326 (2021).

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, M. Violating bell inequality by mixed spin-12 states: necessary and sufficient condition. Phys. Lett. A. 200, 340–344 (1995).

Bravyi, S. & Haah, J. Magic-state distillation with low overhead. Phys. Rev. A. 86, 052329 (2012).

Litinski, D. Magic State Distillation: Not as Costly as You Think. Quantum. 3, 205 (2019).

Campbell, E. T. & O’Gorman, J. An efficient magic state approach to small angle rotations. Quantum Sci. Technol. 1, 015007 (2016).

Bravyi, S., Dial, O., Gambetta, J. M., Gil, D. & Nazario, Z. The future of quantum computing with superconducting qubits. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 160902 (2022).

Bravyi, S. et al. High-threshold and low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum memory. Nature. 627, 778–782 (2024).

Ramette, J., Sinclair, J., Breuckmann, N. P. & Vuletić, V. Fault-tolerant connection of error-corrected qubits with noisy links. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 58 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Demonstration of low-overhead quantum error correction codes https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.09684 (2025).

Horsman, D., Fowler, A. G., Devitt, S. & Meter, R. V. Surface code quantum computing by lattice surgery. N. J. Phys. 14, 123011 (2012).

Litinski, D. & Oppen, F. V. Lattice surgery with a twist: simplifying Clifford gates of surface codes. Quantum. 2, 62 (2018).

Litinski, D. A game of surface codes: large-scale quantum computing with lattice surgery. Quantum. 3, 128 (2019).

Chow, J. M. et al. Universal quantum gate set approaching fault-tolerant thresholds with superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 060501 (2012).

Greenbaum, D. Introduction to quantum gate set tomography. arXiv preprint arXiv:1509.02921 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1509.02921 (2015).

Nielsen, E. et al. Gate set tomography. Quantum. 5, 557 (2021).

Raymer, M. G., Beck, M. & McAlister, D. Complex wave-field reconstruction using phase-space tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 1137–1140 (1994).

Leonhardt, U. Quantum-state tomography and discrete Wigner function. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4101–4105 (1995).

Cramer, M. et al. Efficient quantum state tomography. Nat. Commun. 1, 149 (2010).

Banaszek, K., D’Ariano, G. M., Paris, M. G. A. & Sacchi, M. F. Maximum-likelihood estimation of the density matrix. Phys. Rev. A. 61, 010304 (1999).

Smolin, J. A., Gambetta, J. M. & Smith, G. Efficient method for computing the maximum-likelihood quantum state from measurements with additive Gaussian noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 070502 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Chang-Ling Zou and Prof. Ying Li for reviewing the manuscript and providing valuable suggestions, and thank Cheng Xue and Xi-Ning Zhuang for their assistance reviewing this manuscript. This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFB4504101 and Grant No. 2023YFB4502500).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiaxuan Zhang conceived and designed the project. Peng Duan, Yu-Chun Wu, and Guo-Ping Guo provide overall supervision throughout the research. Jiaxuan Zhang, Zhao-Yun Chen, Bin-Han Lu and Hai-Feng Zhang performed the majority of the experiments. Jiaxuan Zhang and Yun-Jie Wang contributed to data analysis. Jiaxuan Zhang drafted the initial manuscript. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Chen, ZY., Wang, YJ. et al. Demonstrating a universal logical gate set in error-detecting surface codes on a superconducting quantum processor. npj Quantum Inf 11, 177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01118-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01118-6