Abstract

Chronic corneal inflammation, a component of sulfur mustard (SM) and nitrogen mustard (NM) injuries frequently leads to limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD), which can compromise vision. Corneal conjunctivalization, neovascularization, and persistent inflammation are hallmarks of LSCD. Ocular exposure to SM and NM results in an acute and delayed phase of corneal disruption, culminating in LSCD. Available therapies for mustard keratopathy (e.g., topical corticosteroids) often have adverse side effects, and generally are ineffective in preventing the development of LSCD. We developed a novel, optically transparent HDL nanoparticle (NP) with an organic core (oc) molecular scaffold. This unique oc-HDL NP: (i) markedly improved corneal haze during the acute and delayed phases in vivo; (ii) significantly reduced the inflammatory response; and (iii) blunted conjunctivalization and corneal neovascularization during the delayed phase. These findings strongly suggest that our HDL NP is an ideal treatment for mustard keratopathy and other chronic corneal inflammatory diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corneal epithelial stem cells are preferentially located in the basal layer of the limbal epithelium1. These limbal epithelial stem cells (LESCs) are responsible for maintaining corneal epithelial homeostasis and are vital for the proper regeneration of the corneal epithelium after trauma or under chronic inflammatory conditions following severe injuries1,2. Loss or dysfunction of LESCs leads to limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD), which is characterized by persistent corneal epithelial defects, ocular surface scarring, extensive corneal neovascularization and conjunctivalization (the migration of conjunctival goblet cells onto the corneal epithelium), ultimately resulting in decreased corneal transparency and loss of vision3,4,5,6. Every year, over 6 million people worldwide suffer from blindness, of which LSCD is one of the leading causes7. Unfortunately, effective therapies that address the underlying cause of LSCD and prevent blindness are lacking. LSCD can be caused by genetic mutations as well as external insults (e.g., chronic inflammation). To resolve inflammation, commonly prescribed steroidal or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications only provide global immune inhibition. However, the unwanted adverse side effects of long-term steroid use interfere with the process of wound healing thereby limiting the therapeutic effectiveness in corneal epithelial repair8. Therefore, the development of a novel, safe, and target-specific therapy that ameliorates corneal inflammation and LSCD is urgently needed.

Exposure of the eye to sulfur mustard (SM), a chemical warfare agent also known as “mustard gas”, results in disorders characterized by corneal epithelial and stromal damage, collectively termed mustard keratopathy (MK)9,10,11,12,13. SM exposure can have both an acute and a delayed phase9,10. In both humans and animals, the acute phase lasts 1 to 2 weeks and includes corneal epithelial defects, acute inflammation, and corneal haze. These defects usually resolve in a few weeks9,10,12. Following a period of quiescence, chronic or delayed injury can occur (delayed phase), which is apparent clinically as corneal haze and vascularity9,10. The corneal epithelium again becomes disrupted, with a loss of barrier function that causes extensive edema and greater corneal epithelial injury than what is noted in the acute phase of injury. The stroma becomes profoundly disorganized accompanied by scaring or hazing9,10,14,15. A significant increase in cytokines (IL-1α, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8), chemokines, and MMPs (MMP12 and 9) are features of the delayed phase9. Finally, goblet cells appear in the corneal epithelium (conjunctivalization) along with corneal stromal neovascularization, which are features associated with LSCD6,16,17,18, that can significantly contribute to a loss of vision. Like LSCD induced by other insults, available treatments for mustard-induced LSCD are inadequate.

Our group has developed high-density lipoprotein-like nanoparticle (HDL NP)-based eyedrops19. HDL NPs are a synthetic biologic platform whose physical and chemical properties can be engineered for applications in the eye20. The HDL NP platform was inspired by native high-density lipoproteins (HDLs), which are nanoparticles that circulate in the bloodstream and function to solubilize and transport lipids21,22. During inflammation, native HDLs target epithelial cells and innate immune cells to inhibit critical inflammatory pathways and can facilitate the resolution of inflammation23,24,25,26,27. These functions of native HDLs are usually enabled by targeting their high-affinity receptor, scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SR-B1), via interaction with the HDL-defining protein, apolipoprotein A-I (apo A-I)28. We demonstrated that one form of synthetic HDL NP, made using a gold nanoparticle (Au NP) core (Au-HDL NP) as a template for the assembly of a phospholipid layer and apoA-I, actively targeted epithelial and stromal cells when applied topically to the intact ocular surface19,20. Furthermore, we showed that Au-HDL NP attenuates the inflammatory reaction and aids in healing mechanical and chemical insults to the cornea19,20. As gold nanoparticles strongly absorb and scatter visible light, our group recently developed optically transparent molecular organic core (oc)-HDL NPs29.

Herein, we demonstrate that pentaerythritol tetraoleate (PE-O4) and pentaerythritol tetrastearate (PE-S4) HDL NPs are similar in size to native HDLs, and they both function to reduce inflammation in an in vitro screening assay using a macrophage NF-kB reporter cell line. Interestingly, the PE-O4 HDL NP significantly reduced many of the abnormalities associated with both the acute and delayed phases of nitrogen mustard (NM; an analog of SM) exposure in mouse eyes. Specifically, after NM exposure, PE-O4 HDL NPs: (i) improved corneal haze; (ii) significantly reduced the inflammatory response; and (iii) blunted conjunctivalization and corneal neovascularization (features of LSCD). Collectively, these findings indicate that the PE-O4 HDL NP is an ideal treatment for mustard keratopathy and has the potential to improve other chronic corneal inflammatory diseases.

Results

Novel oc-HDL NPs are structurally similar to native HDL and have anti-inflammatory properties

Using the PE-S4 and PE-O4 as oc scaffolds, we assembled the HDL NPs, PE-S4 HDL NP and PE-O4 HDL NP, respectively. The particles were found to be spherical in shape and had mean hydrodynamic diameters of 13-14 nm (Fig. 1 and Table 1, data from dynamic light scattering and transmission electron microscopy), which is consistent with oc-HDL NPs made previously29. Additionally, their diameters were similar to native human HDL2 (Table 1) isolated from human serum and used for comparison.

Zeta potential measurements demonstrate that PE-S4 and PE-O4 HDL NP have negative zeta potentials (−19.83 ± 2.03 mV and −18.90 ± 1.81 mV, respectively), which is similar to native HDLs (e.g, ζ = −19 ± 2 mV for human HDL2)29. The concentration of apoA-I in each sample was measured using the bicinchoninic assay (BCA assay). To demonstrate that apoA-I assembled in the oc-HDL NPs in a manner similar to native HDL, we performed in situ crosslinking of particle-associated apoA-I30. Crosslinking of apoA-I followed by western blotting revealed an average of 2-3 apoA-I copies per oc-HDL NP. The amount of oc-HDL NP used in each experiment was thus based on the apoA-I concentration. To verify that the apoA-I that assembled into the oc-HDL NPs maintained a similar structure to that found in native HDLs, we carried out circular dichroism (CD) analysis. Similar CD spectra were obtained for both synthetic HDL NPs and native HDLs (Fig. 1D) with predominantly alpha-helical structures for the apoA-I. Overall, the PE-S4 and PE-O4 HDL NPs were similar to one another and had measured features consistent with native HDL. We removed the particles from 4 °C and tested their stability at room temperature by measuring their size (dynamic light scattering) and surface charge (zeta potential). The particles were stable for several months, at least, at 4 °C (Supplementary Table 1).

To evaluate the in vitro anti-inflammatory function of oc-HDL NP, we employed human monocyte NF-κB reporter cells (THP1-Dual), which produce secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) upon activation of NF-κB. Cells were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to induce NF-κB and treated with PE-O4 HDL NP, PE-S4 HDL NP, HDL2, or PBS. Both nanoparticles reduced NF-κB signaling in a dose dependent manner and became statistically significant (p < 0.05) relative to the LPS only treatment group at an apoA-I concentration of 6.25 nM, with ~25% reduction in NF-κB activity (Supplementary Fig. 1). At the highest tested concentration of apoA-I (100 nM) the particles reduce NF-kB activity by ~50% (p < 0.001).

A mouse model of nitrogen mustard (NM)-induced keratopathy has features consistent with sulfur mustard (SM) injury

To evaluate potential therapies for mustard keratopathies, it is essential to have an animal model that mimics SM keratopathy. A rabbit model has been developed for SM injury; however, due to the extreme toxicity associated with SM, alternative models are required3,9,14,31. We use nitrogen mustard (NM), an analogue of SM9, in our mouse model. Nitrogen mustard is an approved therapeutic for the treatment of dermatologic conditions such as mycosis fungoides32 and does not have the extreme toxicities associated with SM. Our NM mouse model recapitulates many of the features associated with the acute and delayed phases of SM exposure.

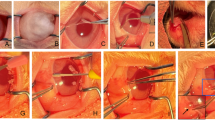

Our NM mouse model is based on a single, 1-minute, topical exposure of the eye to a 2 mm filter paper disc soaked in a 0.5% NM solution. A 2 mm diameter filter paper covers the entire mouse cornea but not the limbal or conjunctival area; however, this area of injury is sufficient to cause a LSCD10. Consistent with the observations in human patients and rabbits3,9,14,31, wild-type mice corneas displayed haze with an average score of 1.9 at 1 week-post NM exposure (acute phase; Fig. 2A, B) using a previously published scoring method33. To clinically evaluate damage to the surface of the cornea following NM exposure, mouse eyes were stained with fluorescein dye and visualized with a cobalt blue light. All NM-exposed eyes revealed areas of fluorescence 1-week post exposure, indicative of corneal epithelial disruption (Fig. 2C). Histological observations of the NM-exposed corneas confirmed and augmented the clinical findings. The corneal epithelium was thin and disorganized, with some focal areas displaying a total loss of epithelium 3 days post-exposure (Fig. 3). Mirroring the clinical haze, the corneal stroma was disorganized and contained a brisk inflammatory infiltrate characterized by monocytes and polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs; Fig. 3). Further characterization of RNAs isolated from the whole corneas by RT-qPCR revealed that NM exposure markedly increased the expression of Cxcl2, Il1b, Mmp9, Cxcl5, Inos, Osm, and Tnfrsf9 (Fig. 5C). At this stage of the acute phase, there was no evidence of corneal angiogenesis or goblet cell egress into the corneal epithelium (conjunctivalization; Fig. 3B).

A, B Mouse eyes were imaged under light scope at the time points indicated after NM exposure. Corneal haze and neovascularization (red arrows) were observed. B Corneal haze was graded on a scale of 0 through 4 as follows: 0, no corneal haze; 1, iris detail visible; 2, Pupillary margin visible, iris detail obscured; 3, pupillary margin not visible; 4, cornea totally opaque. N = 20 mouse eyes. C To determine epithelial integrity, mouse ocular surfaces were stained with fluorescein and imaged under cobalt blue light at the time points indicated after NM exposure. Green fluorescence represents corneal disruption (white arrows). D Whole mount staining for CD31 visualizes blood vessels in ocular surfaces. Neovascularization (white *) in the cornea was detected at 1 week post NM exposure and became severe at 2 weeks post NM exposure. At 4 weeks post NM exposure, most areas of the cornea were vascularized. Uninjured corneas serve as control. The vascularized area in the cornea was measured using ImageJ. N = 4 mice.

After NM exposure, mouse eyes were embedded in paraffin. H&E staining showed inflammatory cell infiltration (green arrows) during the acute phase (3 days post injury; B). H&E staining showed infiltration of immune cells (green arrows), blood vessels (red arrows), and goblet cell clusters in the cornea (blue arrows) during the delayed phase (2 and 4 weeks post injury; C, D). Uninjured cornea was used as control (A).

Two to four weeks post-NM exposure, (the delayed phase), dramatic changes were observed in the corneal epithelium and stroma. Specifically, fluorescein staining revealed a persistent defect on the surface of the corneal epithelium (Fig. 2C), and additional clinical imaging showed that corneal haze became progressively more severe at 2-, 3- and 4-week post-NM injury (Fig. 2A, B). Furthermore, large blood vessels became clinically visible at 3- and 4-week post-NM injury (Fig. 1A; red arrows). Histologically, the corneal epithelium contained numerous clusters of goblet cells amongst the corneal epithelial cells (Fig. 3; blue arrows), which is pathognomonic for conjunctivalization. The corneal stroma also contained frequent large vascular profiles (angiogenesis) with extravasation of red blood cells into the surrounding tissue (Fig. 3; red arrows). Whole-mount staining of corneas with CD31, a vascular marker, amplified the histological findings, with blood vessels detected in the peripheral cornea 2 weeks post-NM injury, and numerous vessels observed in the central corneas at 3- and 4-weeks post NM injury (Fig. 2D). The presence of angiogenesis and conjunctivalization strongly indicates LSCD. Consistent with LSCD, the corneal stroma contained a significant inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 3; green arrows).

Topical treatment with PE-O4 HDL NPs reduced corneal haze and corneal inflammation during the acute phase

We have detected HDL NPs in mouse corneas at 24 h post-treatment20. To examine how rapidly HDL NPs could penetrate an intact epithelium following topical application, we utilized MS MALDI technology and demonstrated that the HDL NPs rapidly entered the intact cornea as early as 1 hour post-treatment and were distributed within the corneal epithelium as well as the stroma (Fig. 4). At 4 h post-treatment, significant signal was still detected throughout the corneal epithelium and stroma (Fig. 4). These observations are consistent with and extend our earlier findings using Cy3-labeled Au HDL NPs20, which revealed that topical application of Au HDL NPs penetrate intact corneal epithelium and can be visualized throughout the corneal epithelium and in stromal keratocytes 24 h post application20. Consistent with previous immunohistochemical observations20, RT-qPCR analysis confirmed the expression of SR-B1, the receptor for HDL NPs, in wild-type mouse corneas. Notably, exposure to NM resulted in a significant upregulation of SR-B1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 2). Since in vitro testing showed that PE-O4 HDL NPs reduced inflammatory responses in a THP-1 reporter cell line (Supplementary Fig. 1), we investigated the efficacy of these NPs in treating the acute phase (3 days post NM exposure). Topical treatment with PE-O4 HDL NPs (2 μM) significantly attenuated NM-induced corneal haze (30% reduction in haze score; Fig. 5A) at 3 days post NM exposure compared to PBS-treated corneas. More importantly, the NPs reduced: (i) inflammatory cell infiltration by 58.3 ± 15.4% (Fig. 5B); and (ii) expression of the proinflammatory genes (Fig. 5C), indicating a dampening of corneal inflammation when compared with the vehicle treatment. An additional feature of NM corneal injury during the acute phase is corneal epithelial thinning9,34 (Fig. 3). H&E staining provided histological evidence that such epithelial thinning was blunted by 79.7 ± 10.6% following topical treatment with PE-O4 HDL NPs (Fig. 5B). Overall, our data indicates that topical application of PE-O4 HDL NPs to the corneal surface has a significant positive effect by alleviating NM-induced corneal haze, inflammation and epithelial defects during the acute phase.

MALDI MSI was conducted to monitor phospholipids in the HDL NPs at 1 and 4 h after topical application of HDL NPs to the intact corneal surface of uninjured WT mice. After topical application of HDL NPs, MALDI MSI detected the spatial distribution of phospholipids in the HDL NPs in the corneal epithelium and stroma. Resolution: 10 µm for all regions. Matrix for MALDI: 10 mg/mL 9-aminoacridine (9AA) in acetone.

Two hours post NM exposure, corneas were treated topically with PE-O4 HDL NP, and PBS (control) once daily for 3 days. A Clinical images visualized corneal haze. PE-O4 HDL NPs attenuates NM-induced corneal haze score. N = 15. B H&E staining was conducted. Then, immune cell filtration throughout the stroma and epithelial thickness was quantified using ImageJ. PE-O4 HDL NPs reduced immune cell infiltration in corneal stroma and prevented epithelial thinning 3 days post-NM exposure (acute phase). N = 5. C Three days post exposure, RT-qPCR was conducted to examine the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in mouse corneas. PE-O4 HDL NPs reduced the levels of proinflammatory gene expression induced by NM exposure during the acute phase. N = 10. Experiments were repeated two times. p values are indicated at the figure.

Topical treatment with PE-O4 HDL NPs reduced corneal haze, corneal inflammation, vascularization and conjunctivalization during the delayed phase

NM exposure caused detrimental effects during the delayed phase including perturbations in the anterior segment that manifested as corneal haze, inflammation, extensive corneal neovascularization, and conjunctivalization (e.g., goblet cells in cornea) of the central cornea (Fig. 2). To examine the efficacy of PE-O4 HDL NPs in mitigating the abnormalities observed during the delayed phase, mouse corneas were topically treated with these NPs once daily for two weeks. Daily topical application of PE-O4 HDL NPs for 14 days resulted in a decreased corneal haze score (~30%; Fig. 6A). Evidence of the anti-inflammatory nature of PE-O4 was the dramatic decrease (33% ± 5%) in inflammatory cells noted in histologic sections of the NM-exposed corneal stroma following 14 days of PE-O4 HDL NP treatment when compared with the PBS control (Fig. 6B). Topical treatment of PE-O4 HDL NPs daily, markedly inhibited conjunctivalization as evidenced by an 81.1 ± 19.6% reduction in corneal epithelial goblet cells, as evidenced by Muc5 immunostaining of corneal epithelial whole mounts (Fig. 7A). Consistent with the results of immunostaining for Muc5, goblet cell clusters were also visualized histologically in sections of the NM-exposed corneal epithelium (Supplementary Fig. 3). PE-O4 HDL NP treatment markedly reduced the numbers of goblet cell clusters when compared with the PBS control (Supplementary Fig. 3). Blood vessels were detected using an anti-CD31 antibody in corneal stromal whole mounts at 2 weeks post NM injury and topical treatment with PE-O4 HDL NPs resulted in a 37.31 ± 12.37% reduction in corneal stromal blood vessels (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, the expression of Vegf showed no significant changes after treatment with PE-O4 HDL NPs (Supplementary Fig. 4). Collectively, these results convincingly demonstrate that PE-O4 HDL NPs attenuate NM-induced conjunctivalization and angiogenesis, hallmarks of LSCD.

Two hours post NM exposure, corneas were treated topically with PE-O4 HDL NP, and PBS (control) once daily for two weeks. A Clinical images visualized corneal haze. PE-O4 HDL NPs reduced NM-induced corneal haze scores at two weeks post NM exposure. N = 15. Experiment repeated three times, p value is indicated at the figure. B H&E staining was conducted and immune cell filtration throughout the stroma was quantified using ImageJ. PE-O4 HDL NPs reduced immune cell infiltration in corneal stroma at 14-day post NM exposure (delayed phase). N = 6. p value is indicated at the figure.

Two hours post NM exposure, corneas were treated topically with PE-O4 HDL NP, and PBS (control) once daily for two weeks. A To assess conjunctivalization, at 2 weeks post NM exposure, immunostaining for muc5 in whole mount corneas visualized goblet cells in the corneal epithelium. Area of goblet cells in the corneal epithelium was measured using ImageJ. HDL NP treatment reduced conjunctivalization during the delayed phase. N = 10. *: p < 0.05. B At 2 weeks post NM exposure, immunostaining for CD31 in the whole mount corneas visualized blood vessels in the corneal stroma. Vascularized area in corneal stroma was measured using ImageJ. HDL NP treatment reduced neovascularization during the delayed phase. N = 10. Experiments are repeated twice. p values are indicated at the figure.

Discussion

The eye is one of the primary routes of entry following exposure to sulfur mustard gas, thus it is not surprising that various animal models have been established to investigate the etiology of ocular sulfur mustard (and its analogue nitrogen mustard) injury. Based primarily on clinical criteria (e.g., haze score, fluoresceine dye exclusion, optical coherence tomography), a consensus exists that ocular mustard keratopathy is biphasic with a relatively transient acute phase lasting 1-2 weeks followed by a more serious delayed phase, which can occur weeks to months after cessation of the acute phase. Using our mouse model, we were able to perform an in depth morphological and immunohistochemical characterization of the temporal changes that occurred to the corneal epithelium and stroma during the acute and delayed phases of NM-induced keratopathy. The most salient features of the delayed phase are a persistent inflammation, prominent vascularization of the peripheral and central corneal stroma and the appearance of conjunctival goblet cells within the corneal epithelium; features consistent with a compromised limbal stem cell niche leading to LSCD. The initial management of LSCD is via medical means; however, in severe cases or total LSCD, surgery is the main resource. Medical management involves removing the toxic insult, restoring the tear film, reducing inflammation, and promoting normal corneal epithelial differentiation. In moderate to extensive LSCD, corticosteroids are frequently administered; however, due to adverse side effects, steroids are not an ideal therapy. We have reported that Au-HDL NPs were an effective topical therapy for the treatment of alkali burns due to their ability to ameliorate inflammation and promote corneal re-epithelialization20. Additionally, these particles were non-toxic to cells and had little, if any, unwarranted side effects. However, the gold core absorbs and scatters light by virtue of its surface plasmon resonance (λmax = 520 nm), which makes gold theoretically less desirable as a therapeutic for the eye where an optically transparent particle will be more ideal. Thus, we developed a unique oc-HDL NP that had similar chemical and biophysical properties as the Au-HDL NPs. Notably, when applied topically to intact corneal surfaces, these oc-HDL NPs rapidly penetrated and were distributed within the corneal epithelium as well as in the stromal keratocytes. Of great translational significance is the fact that the PE-O4 HDL NPs could restore NM-induced LSCD. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a topical therapy that can resolve ocular inflammation, conjunctivalization and corneal stromal neovascularization. With the myriad of diseases having a component of LSCD, we believe that the oc-HDL NP has broad therapeutic potential. Common functions of native HDLs include their ability to reduce inflammation and modulate cell lipid metabolism35. We have demonstrated that our synthetic HDL NPs can reduce inflammation and modulate cell lipid metabolism through mechanisms consistent with native HDL26,29. Importantly, native HDLs have a protective role in stem cell homeostasis. For example, HDL promotes proliferation of stem cells in a variety of tissues, such as adipose-derived stem cells36, vascular endothelial precursor cells37 and bone marrow-derived stem cells38. Of relevance to the present study, a low level of HDL is a predictor of risk for developing corneal LSCD in patients with diabetes39. Native HDL also protects mesenchymal stem cells from reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced stress and promotes stem cell survival via decreasing ROS40. Interestingly, production of ROS is one of key factors associated with the pathogenesis of sulfur mustard toxicity and MGK9. With respect to the mechanism of action of the oc-HDL NPs in combatting LSCD, the PE-O4 core of the oc HDL NP contains several C-C double bonds that can readily react with ROS, effectively neutralizing them and preventing oxidative damage41. This suggests that like native HDL, neutralization of ROS is a potential mechanism by which the oc HDL NPs blunt mustard-induced LSCD. Our observations that the PE-O4 HDL NP concurrently resolved corneal stromal neovascularization and conjunctivalization is consistent with findings that blocking angiogenesis reduced conjunctivalization42.

While LSCD is a well-documented feature of mustard keratopathy in a variety of species, rabbit studies suggest that LSCD does not result from direct injury to limbal epithelial stem cells but rather occurs secondary to damage to the limbal stem cell niche10,43,44,45,46. The limbal stem cell niche is complex, consisting of basally located epithelial stem and early transit amplifying cells, the basement membrane and the stroma beneath the epithelium. With respect to the mechanism of action of PE-O4 on the NM-induced compromization of the limbal stem cell niche, our in vitro studies demonstrated that HDL NP treatment reduced NF-κB signaling, which is a key regulatory pathway for an inflammatory response. The in vivo studies consistently showed that HDL NP treatment reduced the expression of cytokines and chemokines, which suggests that HDL NP alleviates corneal inflammation induced by NM and consequently prevents damage to limbal epithelial stem cells as well as aspects of the stem cell niche via inhibiting NF-κB signaling. These observations are consistent with our previous findings that HDL NPs promoted corneal epithelial wound healing and reduced alkali burn-induced corneal inflammation as well as haze20. We believe that by dampening inflammation, PE-O4 HDL NPs secondarily reduces corneal angiogenesis. In support of this idea, RT-qPCR detected a negligible reduction in VEGF expression, suggesting that HDL NPs have an indirect effect on neovascularization (Supplementary Fig. 4). Importantly, reductions in angiogenesis and conjunctivalization following PE-O4 HDL NP treatment, implies an overall improvement in the limbal stem cell microenvironment. Furthermore, conjunctivalization results from the breakdown of the limbal epithelial stem cell barrier allowing conjunctival goblet cells to migrate into the corneal epithelium3,4,5,6. Collectively, these observations lead us to posit that the PE-O4 HDL NPs restore not only the limbal epithelial stem cells but key aspects of the stem cell niche.

The mechanism by which the oc-HDL NP targets cells may provide some insight into why the synthetic HDL NP is successful in treating NM-induced LSCD. HDLs are essential components of the lipid transport system and the HDL protein, apoA-I, acts as the primary ligand for the HDL receptor SR-B1, which controls the selective uptake of HDL cargo into cells47. We have reported that SR-B1 is prominently expressed on cultured human corneal epithelial cells as well as human and mouse corneal and limbal epithelia20. The SR-B1 receptor is also present on the stromal keratocytes20. The binding of HDL to SR-B1 enables rapid diffusion-based lipid exchange between the bound HDL particle, the cell phospholipid membrane, and the cellular intramembranous network48,49. Also, it is believed that SR-B1 forms a hydrophobic tunnel within the plasma membrane enabling the selective uptake of hydrophobic molecules that bypass lysosomal processing47. Using TEM, we have shown that HDL NPs enter human corneal epithelial cells via a nonendocytic mechanism20. We also demonstrated using MS MALDI technology that HDL NPs rapidly enter the intact cornea and become distributed within the corneal epithelium and the stroma. Together with the increase in SR-B1 expression upon NM-induced injury (Supplementary Fig. 2), we postulate that the direct interaction of the PE-O4 HDL NP with the injured cells would account for its effectiveness as an anti-inflammatory therapeutic. The SR-B1/HDL pathway also potentially represents a novel means for delivering cargo to the cornea. Therefore, HDL NPs themselves or loaded with cargo, such as lipophilic vitamins (e.g., Vitamin D) or miRNAs, represent a new class of ocular therapeutics with potential efficacy for a variety of inflammatory corneal diseases.

Methods

Commercially available materials

Unless otherwise stated, all reagents and reagent-grade solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) and used as received. 3-(Stearoyloxy)-2,2-bis[(stearoyloxy)methyl]propyl stearate (PE-S4) was either synthesized in high-purity (see below) or purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) as a mixture of PE-S4 and incomplete-substitution products (PE-S3 and PE-S2). The phospholipid, 1,2-dipalmitoryl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Human apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) protein, human serum-derived HDL2 and HDL3 subfractions and TGF-β1 protein were purchased from MyBioSource (San Diego, CA). Ultra-pure deionized (DI) water (18.2 MΩ-cm resistivity) was obtained from a Millipore Synergy UV system while nuclease-free water was obtained from Cytiva Life Sciences. Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS, 1X) was purchased from Corning.

Instrumentation

Absorption measurements for BCA, NF-κB reporter, phospholipid quantification, and RNA oligonucleotide quantification assays were recorded with a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek).

Synthesis of PE-S4 and PE-O4 core scaffolds

For this work, we employed two oc molecules to synthesize optically transparent oc-HDL NPs. We utilized one core with unsaturated fatty acyl chains emanating from a central core, pentaerythritol tetraoleate (PE-O4), and one with fully saturated fatty acyl chains, pentaerythritol tetrastearate (PE-S4), to act as scaffolds for the assembly of lipids and apolipoprotein A-I to form PE-O4 HDL NP and PE-S4 HDL NP, respectively. Both of the oc molecules can be made in large-scale and economical fashion.

Synthesis of pure tetraoleyl pentaerythritol (PE-O4) using in-situ-generated oleyl chloride

In a 100 mL flame-dried round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, oleic acid (3.2 mL, 10 mmol, 10 equiv) and anhydrous DCM (10 mL, 0.1 M) were combined under a nitrogen atmosphere applied by a balloon on top of the round-bottom flask. The resulting mixture was placed in an ice bath for 10 min. One drop of DMF was added as the catalyst, followed by the addition of oxalyl chloride (1.8 mL, 20 mmol, 20 equiv). A fine-gauged needle was placed on top of the round-bottom flask to allow for the venting of generated HCl gas during the initial part of the reaction. After gas evolution ceased, the ice bath was removed, and the reaction mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred at ambient temperature for 3 h, during which time the nitrogen atmosphere was occasionally replenished by re-inflating the balloon. After the reaction, the volatile components were then removed on a Schlenk line; anhydrous DCM was then added to the resulting crude product to redissolve it for the next step.

The round-bottom flask containing the DCM solution of the in-situ-generated oleyl chloride was capped with a rubber septum and placed in an ice bath to cool down to 0 °C. Under a nitrogen atmosphere applied by a balloon on top of the flask, pentaerythritol (0.14 g, 1 mmol, 1 equiv) and pyridine (0.8 mL, 10 mmol, 10 equiv) were added neat. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The reaction mixture was poured into a separation funnel and washed with NaOH (3 ×10 mL of a 0.1 M aqueous solution) and HCl (10 mL of a 0.1 M aqueous solution). The remaining organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The crude product was then subjected to column chromatography (30 mm × 250 mm silica gel, hexanes/DCM eluents at 10:1, 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1 ratio). This process afforded the desired compound as a yellow oil after isolation (0.4 g, 0.34 mmol, 34% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.89 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 12H), 1.28 (dt, J = 14.9, 4.8 Hz, 91H), 1.51-1.66 (m, 13H), 2.01 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 16H), 2.30 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 8H), 4.11 (s, 8H), 5.27-5.44 (m, 8H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.3, 22.8, 25.0, 27.3, 27.4, (multiple closely spaced alkyl peaks: 29.27, 29.28, 29.33, 29.47, 29.48, 29.68, 29.86, 29.92), 32.1, 34.3, 42.0, 62.3, 76.9, 77.2, 77.4, 129.9, 130.2, 173.4.

Synthesis of pure tetraoleyl pentaerythritol (PE-O4) using commercially available oleyl chloride

In a 100 mL flame-dried round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar and attached to a Schlenk line, oleoyl chloride (3.61 g, 12 mmol, 6 equiv) and pentaerythritol (0.272 g, 2 mmol, 1 equiv) were combined under a nitrogen atmosphere. The resulting reaction mixture was then stirred at 120 °C under dynamic vacuum for 1 h and then static vacuum for 3 additional h. The crude reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature, diluted with DCM (15 mL), combined with aqueous NaOH (30 mL of a 1 M solution), and stirred for 15 min before being poured into a separation funnel. The aqueous layer, which contains some solids, was separated from the organic, filtered, and extracted with DCM (2 ×15 mL). The DCM extract was then washed with saturated brine (30 mL), combined with the previous organic layer, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated to dryness. The resulting product was further purified using column chromatography (30 mm × 250 mm, hexane/DCM eluents at 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1 ratio). This process afforded the desired pure compound as a yellow oil after isolation (1.4 g, 1.19 mmol, 61% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.83–0.92 (m, 13H), 1.19–1.39 (m, 80H), 1.60 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 8H), 2.01 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 15H), 2.30 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 8H), 4.11 (s, 8H), 5.34 (qd, J = 3.7, 1.6 Hz, 8H). 13 C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.3, 22.8, 25.0, 27.4, (multiple closely spaced alkyl peaks: 29.28, 29.47, 29.68, 29.89), 32.1, 34.2, 42.0, 62.3, 129.86, 130.15, 173.36.

Synthesis of pure tetrastearyl pentaerythritol (PE-S4) core using commercially available stearoyl chloride

In a 100 mL flame-dried round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar and attached to a Schlenk line, stearoyl chloride (3.64 g, 12 mmol, 6 equiv) and pentaerythritol (0.272 g, 2 mmol, 1 equiv) were combined under a nitrogen atmosphere. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at 120 °C under dynamic vacuum for 1 h and then static vacuum for 3 h. The crude reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature, diluted with DCM (15 mL), combined with aqueous NaOH (30 mL of a 1 M), and stirred for 15 min before being poured into a separation funnel. The aqueous layer, which contains some solids, was separated from the organic, filtered, and extracted with DCM (2 × 15 mL). The DCM extract was then washed with saturated brine (30 mL), combined with the previous organic layer, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure until a significant amount of the pure product began to precipitate out of solution. The precipitated compound was then isolated via filtration, quickly washed over the filter with cold DCM, collected, and dried under vacuum. This process afforded the desired pure compound as a white waxy solid (1.5 g, 1.22 mmol, 64% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 0.88 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 12H), 1.25 (s, 109H), 1.59 (p, J = 7.3 Hz, 12H), 2.30 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 8H), 4.11 (s, 8H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.7, 24.9, 29.2, 29.3, 29.5, 29.7, 29.7, 31.9, 34.1, 62.2, 173.3.

Assembly of oc-HDL NPs

Assembly of PE-S4 HDL NP and/or PE-O4 HDL NP was conducted by first preparing stocks of DPPC (1 mM solution in dichloromethane (DCM)) and the organic core (either PE-S4 or PE-O4 as 0.1% w/v solutions in DCM). In what we call the “one pot method,” all the components are dissolved in solvent and combined into a single vial. From the DPPC stock, a 200 nmol quantity is transferred to a clean 2 mL glass vial. To this was then added 1 nmol quantity of the organic core (either PE-S4 or PE-O4). Then, an aliquot containing 2 nmol of apoA-I dissolved in 110 μL of PBS was added to the glass vial. The mixture in the glass vial was vortexed for 10 s and the glass vial was then placed on ice for 15 min to cool down. The cooled-down mixture was then sonicated in a Bransonic 1800 (Branson) lab sonicator for 1 min, followed by 30 sec of rest; and this sonication-rest cycle was repeated 4 more times. After the final round of sonication, the glass vial, now containing a milky white emulsion, was placed on ice again until ready for the next step (typically <10 min). A small magnetic stir bar was added and the contents of the glass vials were then stirred while open to the ambient atmosphere to allow the organic solvent to evaporate. Once only ~100 μL of PBS remained (~1 h after stirring) and the solution had become clear, the vial was capped and stored overnight at 4 °C.

The following day, the contents of the glass vials were transferred to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min to remove any large lipid assemblies that may have formed. The solution/ supernatants were then transferred to pre-wetted Amicon Ultra 0.5 mL 50 kDa MWCO regenerated cellulose spin columns (Millipore) and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, after which the flow-through was discarded and the retentate (usually 20-50 μL) was further diluted with PBS (0.5 mL), homogenized, and centrifuge again. This centrifugation-and-washing cycle was repeated at least 3 times to remove any un-assembled apoA-I, lipid, or core material. After the final wash, the retentate was brought to a final volume of 100 μL with PBS and filtered using a regenerated cellulose syringe filter (4 mm, 0.2 μm pore size, Thermo Scientific). Following filtration, the oc HDL NPs stocks were either used immediately or stored at 4 °C.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

DLS and zeta potential measurements were conducted on a Zetasizer Nano ZS equipped with a He-Ne laser (633 nm) using non-invasive backscatter (173° scattering angle) for detection. For both DLS and zeta potential measurements, samples were prepared in DI water at 150 μM protein concentration. For each sample, three measurements were recorded with 10 runs per measurement.

Negative stain transmission electronic microscopy

Copper grids were first prepared by treating in a plasma cleaner for 10 sec. Particles were then diluted to an apoA-I concentration of 250 μM in PBS and 20 μL of this solution was drop-cast onto plasma treated grids and left there for 5 min. Grids were washed twice with PBS and then stained for 1 min in a 2% aqueous uranyl acetate solution. Finally, the grids were washed with water and air-dried before imaging with a FEI Tecnai Spirit TEM operating at 80 kV.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

Particles were prepared at an apoA-I concentration of 15 μM in a 10 mM monosodium phosphate buffer and analyzed in a 0.1 mm quartz cuvette (Jasco) on a J-1500 CD Spectrometer (Jasco). Spectra were captured between 190 and 250 nm. Secondary structure analysis was performed using the BeStSel software, available at https://bestsel.elte.hu/index.php.

In situ apoA-I crosslinking and western blot

In situ crosslinking of apoA-I was carried out to stabilize oligomerized apoA-I in ocHDL NP. The bis(sulfosuccinidimidyl)suberate (BS3, Sigma Aldrich) crosslinker was used for this purpose according to a previously reported protocol29. In short, ocHDL NP were diluted to a final protein concentration of 50 μg/mL in PBS. The BS3 reagent was then added to the particles (final concentration = 2.5 mM). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min before the reaction was quenched by adding 0.5 M Tris (final concentration = 45 mM). The apoA-I oligomer ladder was generated by mixing PBS solutions of apoA-I (500 μg/mL) with BS3 (final concentration = 0.25 mM) and incubating for 4 h at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 M Tris (final concentration = 45 mM).

The apoA-I ladder and crosslinked particle samples were run on a pre-cast 4-20% polyacrylamide gel (MiniProtean TGX, Bio-Rad). The protein was then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane in tris-glycine buffer with 20% w/v methanol. Next the membrane was rinsed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and blocked in 5% w/v nonfat dry milk diluted in TBS for 1 h at room temperature. A primary anti-apoAI antibody (rabbit, Abcam) was added to the membrane at 1:1000 dilution in 5% w/v nonfat dry milk and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The following day, the membrane was washed three times for 10 min each in TBS-Tween (0.1%). An anti-rabbit HRP conjugated secondary antibody (goat, BioRad) was then added at a 1:2000 dilution in 5% w/v nonfat dry milk and incubated at room temperature for 2 h, after which the membrane was washed 3 three times for 10 min each in TBS-Tween (0.1%). Finally, the membrane was bathed in electrochemiluminescence substrate solution for 1 min and imaged on an C300 Gel Imager (Azure Biosystems).

Quantification of protein content of synthetic HDL NPs and native HDLs

The protein content of particles and native HDL was determined using a commercially available bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Fisher) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, a standard curve was generated in a 96-well plate by adding bovine serum albumin (BSA) into aliquots of BCA reagent (final volume = 80 μL) in duplicate, to attain concentrations ranging from 0.125-2 mg/mL. Nanoparticle samples were diluted into BCA reagent using the same method to generate a 1:16 dilution in triplicate. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 20 min after which the absorbance of each well was measured with a Synergy microplate reader at 562 nm. A linear regression was calculated for the standard curve using the least squares method and protein concentration of particle samples interpolated from the line of best fit.

Phospholipid quantification

The phospholipid content of nanoparticles and native HDL was quantified using a commercially available phospholipid quantification kit (Sigma Aldrich) and per the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, a calibration curve was generated in a 96-well plate by dilution of an included phospholipid standard to concentrations ranging from 20-100 μM into DI water. Samples were serially diluted in DI water, after which an enzyme/reagent mixture was add to sample and standards. The plate was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C before measuring the absorbance of each well at 570 nm with a Synergy microplate reader. Final phospholipid concentrations in samples were interpolated from a linear standard curve generated using the least squares method.

NF-κB activity assays

For NF-κB activity assays, THP1-Dual cells (Invivogen) were cultured in a base media of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. After several passages, cells containing the NF-κB reporter complex were selected (base media containing 10 μg/mL of Blasticidin and 100 μg/mL of Zeocin) prior to being exchanged into base media for experiments. The THP1-Dual cells were plated into a 96-well plate at 1 × 105 cells/well and stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at (1 ng/mL) for 24 h. Experimental wells were simultaneously treated with LPS and test particles for 24 h. After 24 h, 20 μL of supernatant was transferred from culture wells to a new 96-well plate and 180 μL of Quanti-Blue secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) solution (Invitrogen) was added. The plate was then incubated for 1-4 h at 37 °C after which point a Synergy microplate reader was used to measure the absorbance of each well at 640 nm.

Mouse Nitrogen Mustard Cornea Injury Model

All procedures received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Northwestern University and are adherent to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Female C57BL/6 and Balb/c wild-type mice, 6 weeks old, were procured from Charles River. Sulfur mustard (SM) is not used in a normal laboratory setting because SM is likely to cause extensive incapacitating injuries to the eyes, skin, and respiratory tract of exposed persons. Whereas NM as it is a dermatological therapeutic that mimics many if not most of the SM etiology. A 0.5% (w/v) solution of mechlorethamine hydrochloride (nitrogen mustard; Sigma) was made in PBS with 3% DMSO immediately before use and kept for no more than 10 min. Mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). After anesthesia, a sterile filter paper disc (2 mm in diameter) was soaked and saturated with this nitrogen mustard (NM) solution and then placed on the mouse central corneas for 1 minute. Both eyes were exposed to the NM. Prior to exposure, mice were treated topically with analgesia (proparicaine eye drops). After exposure, to relieve distress, mice received sustained-release buprenorphine dosed at 1 mg/kg SC q48h.

The mice were euthanized using CO2, followed by cervical dislocation. After euthanasia, mouse eyes were removed. For histology and immunostaining, eyes were fixed in formalin. For whole mount, eyeballs were fixed in PFA. For RNAs, corneal buttons were dissected and homogenized in Qiazol.

HDL NPs eye drops topical treatment

Two hours postexposure to NM, mice were topically treated with 2 μM PE-O4 HDL nanoparticle (NP) solution in PBS at a dose of 40 µl per eye or PBS (vehicle control). Mice that were not exposed to NM were used as a non-injured/healthy control. Mice received topical treatments daily for 3 days for the acute inflammation model and daily for 14 days to mimic the chronic, long-term injury model. We did not observe any adverse reactions to the topical application of PE-O4 HDL NP, such as excessive scratching of the eyes, eyelid closure and or exudate around the eyes. Mice tolerated daily application of the NP well.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI) Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

MALDI-MSI sample preparation and analysis was performed at the Integrated Molecular Structure Education and Research Center (IMSERC) at Northwestern University. Fresh frozen tissue sections on ITO (indium tin oxide)-coated glass slides were defrosted under vacuum conditions using a vacuum chamber. After taking an optical image of the ITO-coat glass slide using a document scanner, matrix application was conducted using a TM-Sprayer (HTX Technologies, LLC, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA) to spray a solution of 10 mg/mL solution of 9-aminoacridine (9AA) matrix, which was dissolved in 75/25 (v/v) acetonitrile/water. The sprayer settings for 9AA were: number of passes, 8; nozzle temperature, 60 °C; flow rate, 0.12 ml/min; velocity, 1200 mm/min; gas flow rate, 3 l/min; and drying time, 10 sec; nebulizer pressure, 10 psi; nozzle height, 40 mm; and applied with a crisscross pattern and a spacing of 2 mm.

MALDI-MSI data acquisition was performed using a rapifleX MALDI Tissuetyper (Bruker Scientific, LLC, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA). Data was acquired in negative-ion reflectron mode and calibrated using red phosphorus before data acquisition. The mass range collected was m/z 200 – 2000, collecting 200 shots per pixel, using a laser power at 75% - 80%, a sampling rate of 1.25 GS/s, and the raster and laser focus were matched to obtain a 10 µm image resolution. The data was processed using SciLS 2023 Pro to generate the ion heat maps, where the imaging data were normalized using the total ion current (TIC) of the image dataset.

Clinical Imaging for Injury and Corneal Haze

The mouse eyes were examined for clinical haze scores using a light microscope at designated time intervals following exposure to NM. Corneal haze was graded on a scale of 0 through 4 as follows: 0, no corneal haze; 1, iris detail visible; 2, Pupillary margin visible, iris detail obscured; 3, pupillary margin not visible; 4, cornea totally opaque. To assess epithelial integrity, the ocular surfaces of the mice were topically stained with 0.5% fluorescein in PBS (10 µL for each eye, then washed with PBS), then observed under cobalt-blue light at the specified time intervals post-NM exposure.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis

Mouse cornea was meticulously dissected under the dissection scope, enabling the isolation of cornea following previously published protocols20,50. Tissues were homogenized in Qiazol lysis buffer provided by the miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). RNAs were extracted from the corneas using the miRNeasy mini kit following the manufacturer manual (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). For RT-qPCR, cDNA was synthesized by the Superscript III reverse-transcription kit following the manufacturer manual (Invitrogen). To quantify gene expression, qPCR was conducted in 96 well plates with 10 µl reaction mix on a Lightcycler 96 real-time PCR system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, US) employing a quantitative SYBR green PCR kit (Roche). Specific primers for Mouse Inos, CxCl5, IL1b, Mmp9, CxCl2, and TNFRSF9 (detailed in Supplementary Table 2) were utilized. Meanwhile, the internal control, Mouse Rpl19, was used for comparative analysis. The results were calculated as the fold change concerning the wild-type uninjured controls. The fold changes were determined by ΔΔCt.

Whole mount staining

Whole mount staining was conducted as previously published protocols51,52. Briefly, mouse corneas, including the limbus, were meticulously dissected under microscopic observation. Subsequently, these tissues were fixed in a formaldehyde fixative solution (FF) for 1 hour and 15 min at 4 °C. The FF solution was prepared freshly by mixing 1 ml of 10x PBS, 270 µl of 37% formaldehyde to achieve a 1% final concentration, 10 µl of 2 mM MgCl2, 200 µl of 250 mM EGTA (Ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid) (pH 8.0) to reach 5 mM, 20 µl of 10% NP40 to a final concentration of 0.02%, and water to a final volume of 10 ml. After fixation, the tissues were washed with 1x PBS containing 0.02% NP40, then fixed in a 4:1 mixture of pre-cooled (to −20 °C) methanol and DMSO for 2 h. Then, the eyes were transferred to pre-cooled 100% methanol, in which they could be stored at −20 °C for several weeks. Following fixation, tissues were stained with either rat anti-CD31 (BD Biosciences®) or mouse anti-muc5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific®) at a dilution of 1:1000. DAPI was used for counterstaining at a 1:2000 dilution. To ensure the corneas lay as flat as possible on glass slides, small incisions were made at the edges before placement. Whole-mount imaging was performed using a Nikon CSU-W1 Yokogawa Sora Confocal Microscope, equipped with a 10× objective lens. Imaging was conducted in the z-plane, capturing 10 sequential sections to ensure a good three-dimensional visualization.

Histology

Mouse whole eyes were dissected and then fixed in a neutral buffered 10% formalin solution for 24 hours. Tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. Briefly, after deparaffinization and re-hydration, slides were stained in Mayer’s Hematoxylin Solution for 30 sec and rinsed in running tap water for 2 min. Slides were dipped in 1% Acid Alcohol twice and washed with running tap water for 2 min. Slides were counterstained in Eosin Solution (1 ml Eosin Solution + 2ul Acetic Acid Glacial) for 2-3 min. After rinsing with 3-4 washes of tap water, slides were dehydrated and mounted. The resulting slides were analyzed under a Zeiss Axioplan 2 Light Microscope. Epithelial thickness and infiltrated immune cell quantification within the stroma were analyzed with ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

Visual graphics were generated, and statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 10.2.0 software (San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was assessed with an unpaired t-test, with data presented as means±standard error of the mean (SEM). Haze score was considered as categorical data and a Mann−Whitney U test was conducted. A p value of<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were replicated at least three times.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Cotsarelis, G., Cheng, S. Z., Dong, G., Sun, T. T. & Lavker, R. M. Existence of slow-cycling limbal epithelial basal cells that can be preferentially stimulated to proliferate: implications on epithelial stem cells. Cell 57, 201–209 (1989).

Lehrer, M. S., Sun, T. T. & Lavker, R. M. Strategies of epithelial repair: modulation of stem cell and transit amplifying cell proliferation. J. Cell Sci. 111, 2867–2875 (1998).

Kadar, T. et al. Characterization of acute and delayed ocular lesions induced by sulfur mustard in rabbits. Curr. Eye Res 22, 42–53 (2001).

Kadar, T. et al. Prolonged impairment of corneal innervation after exposure to sulfur mustard and its relation to the development of delayed limbal stem cell deficiency. Cornea 32, e44–e50 (2013).

Sprogyte, L., Park, M. & Di Girolamo, N. Pathogenesis of Alkali Injury-Induced Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency: A Literature Survey of Animal Models. Cells 12 (2023).

Deng, S. X. et al. Global Consensus on Definition, Classification, Diagnosis, and Staging of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency. Cornea 38, 364–375 (2019).

Resnikoff, S. et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull. World Health Organ 82, 844–851 (2004).

Petroutsos, G., Guimaraes, R., Giraud, J. P. & Pouliquen, Y. Corticosteroids and corneal epithelial wound healing. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 66, 705–708 (1982).

Fuchs, A., Giuliano, E. A., Sinha, N. R. & Mohan, R. R. Ocular toxicity of mustard gas: A concise review. Toxicol. Lett. 343, 21–27 (2021).

McNutt, P. Progress towards a standardized model of ocular sulfur mustard injury for therapeutic testing. Exp. Eye Res 228, 109395 (2023).

Alemi, H. et al. Insights into mustard gas keratopathy- characterizing corneal layer-specific changes in mice exposed to nitrogen mustard. Exp. Eye Res 236, 109657 (2023).

Umejiego, E. et al. A corneo-retinal hypercitrullination axis underlies ocular injury to nitrogen mustard. Exp. Eye Res 231, 109485 (2023).

Soleimani, M. et al. Cellular senescence implication in mustard keratopathy. Exp. Eye Res 233, 109565 (2023).

Goswami, D. G. et al. Acute corneal injury in rabbits following nitrogen mustard ocular exposure. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 110, 104275 (2019).

Solberg, Y., Alcalay, M. & Belkin, M. Ocular injury by mustard gas. Surv. Ophthalmol. 41, 461–466 (1997).

Puangsricharern, V. & Tseng, S. C. Cytologic evidence of corneal diseases with limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology 102, 1476–1485 (1995).

Tseng, S. C. Concept and application of limbal stem cells. Eye (Lond) 3, 141-157 (1989).

Le, Q., Xu, J. & Deng, S. X. The diagnosis of limbal stem cell deficiency. Ocul. Surf. 16, 58–69 (2018).

Lavker, R. M. et al. Synthetic high-density lipoprotein nanoparticles: Good things in small packages. Ocul. Surf. 21, 19–26 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. HDL nanoparticles have wound healing and anti-inflammatory properties and can topically deliver miRNAs. Adv.Ther (Weinh)3 (2020).

Kontush, A. et al. Structure of HDL: particle subclasses and molecular components. Handb. Exp. Pharm. 224, 3–51 (2015).

Mehta, A. & Shapiro, M. D. Apolipoproteins in vascular biology and atherosclerotic disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19, 168–179 (2022).

De Nardo, D High-density lipoprotein mediates anti-inflammatory reprogramming of macrophages via the transcriptional regulator ATF3. Nat. Immunol. 15, 152–160 (2014).

Murphy, A. J. et al. High-density lipoprotein reduces the human monocyte inflammatory response. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 2071–2077 (2008).

Gruaz, L., Delucinge-Vivier, C., Descombes, P., Dayer, J. M. & Burger, D. Blockade of T cell contact-activation of human monocytes by high-density lipoproteins reveals a new pattern of cytokine and inflammatory genes. PLoS One 5, e9418 (2010).

Hyka, N. et al. Apolipoprotein A-I inhibits the production of interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha by blocking contact-mediated activation of monocytes by T lymphocytes. Blood 97, 2381–2389 (2001).

Hu, J. et al. High-density Lipoprotein and Inflammation and Its Significance to Atherosclerosis. Am. J. Med Sci. 352, 408–415 (2016).

Song, G. J. et al. SR-BI mediates high density lipoprotein (HDL)-induced anti-inflammatory effect in macrophages. Biochem Biophys. Res Commun. 457, 112–118 (2015).

Henrich, S. E., Hong, B. J., Rink, J. S., Nguyen, S. T. & Thaxton, C. S. Supramolecular Assembly of High-Density Lipoprotein Mimetic Nanoparticles Using Lipid-Conjugated Core Scaffolds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 9753–9757 (2019).

Silva, R. A. et al. Structure of apolipoprotein A-I in spherical high density lipoproteins of different sizes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 12176–12181 (2008).

Gordon, M. K. et al. Rabbit Corneal Epithelia and Keratocytes Respond to Sulfur Mustard Exposure by Increasing Autophagy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53 (2012).

Vonderheid, E. C. Topical mechlorethamine chemotherapy. Considerations on its use in mycosis fungoides. Int J. Dermatol 23, 180–186 (1984).

Wang, J. et al. The ACE2-deficient mouse: A model for a cytokine storm-driven inflammation. FASEB J. 34, 10505–10515 (2020).

Joseph, L. B. et al. Sulfur mustard corneal injury is associated with alterations in the epithelial basement membrane and stromal extracellular matrix. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 128, 104807 (2022).

Endo, Y., Fujita, M. & Ikewaki, K. HDL Functions-Current Status and Future Perspectives. Biomolecules 13 (2023).

Shen, H. et al. High density lipoprotein promotes proliferation of adipose-derived stem cells via S1P1 receptor and Akt, ERK1/2 signal pathways. Stem Cell Res Ther. 6, 95 (2015).

Lee, W. Y. et al. Autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells treatment demonstrated favorable and sustainable therapeutic effect for Crohn’s fistula. Stem Cells 31, 2575–2581 (2013).

Zhang, Q., Yin, H., Liu, P., Zhang, H. & She, M. Essential role of HDL on endothelial progenitor cell proliferation with PI3K/Akt/cyclin D1 as the signal pathway. Exp. Biol. Med (Maywood) 235, 1082–1092 (2010).

Chen, D. et al. Evaluation of Limbal Stem Cells in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: An In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Study. Cornea 43, 67–75 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. High density lipoprotein protects mesenchymal stem cells from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis via activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway and suppression of reactive oxygen species. Int J. Mol. Sci. 13, 17104–17120 (2012).

Magtanong, L. et al. Exogenous Monounsaturated Fatty Acids Promote a Ferroptosis-Resistant Cell State. Cell Chem. Biol. 26, 420–432 e429 (2019).

Joussen, A. M. et al. VEGF-dependent conjunctivalization of the corneal surface. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 117–123 (2003).

Kadar, T. et al. Limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) in rats and mice following whole body exposure to sulfur mustard (SM) vapor. Exp. Eye Res 223, 109195 (2022).

Kadar, T. et al. Ocular injuries following sulfur mustard exposure-pathological mechanism and potential therapy. Toxicology 263, 59–69 (2009).

Javadi, M. A. et al. Chronic and delayed-onset mustard gas keratitis: report of 48 patients and review of literature. Ophthalmology 112, 617–625 (2005).

Baradaran-Rafii, A., Javadi, M. A., Karimian, F. & Feizi, S. Mustard gas induced ocular surface disorders. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res 8, 383–390 (2013).

Shen, W. J., Azhar, S. & Kraemer, F. B. SR-B1: A Unique Multifunctional Receptor for Cholesterol Influx and Efflux. Annu Rev. Physiol. 80, 95–116 (2018).

Phillips, M. C. Molecular mechanisms of cellular cholesterol efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 24020–24029 (2014).

Litvinov, D. Y., Savushkin, E. V. & Dergunov, A. D. Intracellular and Plasma Membrane Events in Cholesterol Transport and Homeostasis. J. Lipids 2018, 3965054 (2018).

Peng, H., Kaplan, N., Liu, M., Jiang, H. & Lavker, R. M. Keeping an Eye Out for Autophagy in the Cornea: Sample Preparation for Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing. Methods Mol Biol (2023).

Kaplan, N. et al. EphA2/Ephrin-A1 Mediate Corneal Epithelial Cell Compartmentalization via ADAM10 Regulation of EGFR Signaling. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 393–406 (2018).

Kaplan, N. et al. Ciliogenesis and autophagy are coordinately regulated by EphA2 in the cornea to maintain proper epithelial architecture. Ocul. Surf. 21, 193–205 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Nikon CAM: Imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Microscopy (RRID: SCR_020996) generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer CenterIMSERC: MALDI work made use of the IMSERC (RRID:SCR_017874) MS facility at Northwestern University, which has received support from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), the State of Illinois, and the International Institute for Nanotechnology (IIN). ANTEC: Circular Dichroism spectroscopy was performed in the Analytical BioNanoTechnology Equipment Core Facility of the Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology at Northwestern University. ANTEC receives partial support from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633) and Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.NU-BIF: Confocal microscopy was performed at the Biological Imaging Facility at Northwestern University (RRID:SCR_017767), graciously supported by the Chemistry for Life Processes Institute, the NU Office for Research. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health Chemical Countermeasures Research Program (CCRP) executed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), and the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director (NIH OD) under award number U54AR079795 (K.Q.L., H.P., R.M.L., E.F., T.J.F., J.E.T., N.K., V.D., S.T.N., and C.S.T.). This research was also supported by National Institutes of Health grant EY019463 (R.M.L.), National Institutes of Health grants EY032922, EY028560, EY036320 (H.P.), National Institutes of Health grant T32GM008152 (T.J.F.), and National Institutes of Health grant F31AR081685 (J.E.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: C.S.T., R.M.L., H.P., T.J.F., E.K.N., K.Q.L. Methodology: C.S.T., R.M.L., H.P., E.K.N., T.J.F., A.M., N.K., S.T.N., F.T., P.F. Investigation: E.K.N., T.J.F., A.M., V.X., N.K., F.T., J.E.T., P.F., J.K., E.M.B., A.C., E.W.R., V.P.D. Visualization: T.J.F., E.K.N., X.Q. Funding acquisition: R.M.L., C.S.T., H.P., K.Q.L. Project administration: K.Q.L., C.S.T., R.M.L., H.P. Supervision: C.S.T., H.P., R.M.L., K.Q.L. Writing—original draft: R.M.L., T.J.F., H.P. Writing—review & editing: T.J.F., E.K.N., A.M., N.K., F.T., J.E.T., K.Q.L., S.T.N., R.M.L., H.P., C.S.T.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

CST is the co-founder of a biotech company that licensed technology from Northwestern University. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kayaalp Nalbant, E., Feliciano, T.J., Mohammadlou, A. et al. A novel therapy to ameliorate nitrogen mustard-induced limbal stem cell deficiency using lipoprotein-like nanoparticles. npj Regen Med 10, 14 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-025-00402-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-025-00402-5