Abstract

Chronic wounds present a major burden to patients, health care professionals, and health care systems worldwide, yet treatment options remain limited and often ineffective. Although initially promising, growth factor-based therapies displayed limited and underwhelming effectiveness largely due to poor bioavailabilbioity and impaired receptor function within the chronic wound microenvironment. Here we demonstrate that chronic wounds exhibit elevated cholesterol synthesis, which disrupts growth factor signaling by sequestering receptors within lipid rafts. To address this, we developed a novel therapy combining growth factors with cyclodextrin in an ECM-mimetic scaffold, enabling localized cholesterol modulation and improved receptor accessibility. We demonstrate that this approach enhances growth factor bioavailability and functionality, creating a regenerative environment. In both human ex vivo and diabetic mouse wound models, this targeted co-delivery strategy significantly improved healing outcomes by stimulating angiogenesis and re-epithelialization, supporting a promising new direction for chronic wound therapy through localized metabolic modulation of the wound niche.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wound healing is an intricate biological process requiring coordination among various cell types to repair the skin barrier, while failure to progress through the phases of healing can lead to the development of chronic wounds. Highly prevalent and costly, chronic wounds represent a major burden, affecting millions and costing billions1,2,3,4. Current therapeutic options are limited by poor understanding of the complex pathophysiology underlying chronic wounds5,6,7, creating an urgent and unmet need for more effective treatment strategies.

Chronic wounds are typically managed through a combination of approaches, including debridement (surgical or enzymatic), offloading, compression, and application of dressings designed to facilitate wound healing. Beyond standard of care8,9, more alternative therapeutic options include negative pressure therapy, skin grafts, skin substitutes, and the use of recombinant growth factor-based therapies7,10. Growth factors play pivotal roles in coordinating various cellular processes crucial for tissue regeneration, such as proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, differentiation, and collagen deposition11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Their capacity to coordinate and synchronize multiple cellular types and behaviors, arguably, makes them an ideal approach to treat complex diseases, such are chronic wounds. A topical rhPDGF-BB gel formulation is currently the only FDA-approved growth factor biologic for treatment of diabetic foot ulcers; however, clinical studies have reported limited improvements in healing20. Moreover, strategies employing other growth factors (including EGF, bFGF, KGF, VEGF, and others) have shown varying degrees of success in clinical trials, without reaching efficacy threshold10,21,22,23,24,25,26. This limited clinical effect is attributed to the multifactorial etiology of chronic wounds and limited bioavailability of growth factors due to the harsh wound environment and increased protease activity, resulting in rapid degradation of the topically applied growth factors7,27,28. In addition, we have shown that dysregulation of growth factor receptors precludes their signaling in chronic wounds29,30.

Caveolin-1 (Cav1), the primary structural component of specialized lipid rafts known as caveolae, has been implicated in the pathophysiology of chronic wounds31. Caveolae, microdomains abundant in cholesterol and sphingomyelin, in addition to their role in endocytosis of various molecules32,33 have been recognized to also play a significant role as organizing centers for signaling molecules34,35,36. Increased levels of Cav1 may sequester growth factor receptors, including among others TGFβR and EGFR37,38,39,40 and inhibit their downstream signaling. Consequently, Cav1 has been implicated in regulation of various cellular processes, including differentiation, migration, proliferation, and senescence41,42,43. We have shown that cells at the edge of a healing wound downregulate expression of Cav1 to facilitate increased proliferation and directional cell migration into the open wound to foster wound re-epithelialization31,40. Interestingly, in tissue samples obtained from patients, Cav1 was found upregulated in multiple types of non-healing wounds, including diabetic foot and venous leg ulcers31,40,44,45. Cav1 overexpression in human keratinocytes inhibits directional migration by sequestering EGF-receptor signaling and enhancing RhoA activation to increase stress fiber formation44. Conversely, Cav1 knockdown restores migration by promoting Cdc42 and Rac1 activity, facilitating the formation of filopodia and lamellipodia31,40,44. Thus, for a successful growth factor therapy, it is essential to provide both: sustained delivery and receptor availability.

Removal of cholesterol from cellular membranes prevents Cav1 from inhibiting growth factor receptor signaling and has been demonstrated to promote healing by our group and others31,46,47,48,49. To this end, cyclodextrins are cyclic oligosaccharide molecules that form a ring-like structure with a hydrophobic cavity, which has the potential to encapsulate nonpolar, hydrophobic substances, such as cholesterol50,51. One derivative, methyl-beta-cyclodextrin (MβCD) is widely used in research and in pharmaceutical applications, primarily for its ability to interact with cholesterol and other lipids52. Additionally, 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HβCD), is an FDA-approved compound that is currently found in many pharmaceuticals to improve solubility and bioavailability of various compounds53,54. Thus, cyclodextrins offer a promising pharmacological approach of sequestering cholesterol and downregulating Cav1, by which released growth factor receptors may restore their signaling capacity. Taken together, we posit that harnessing this mechanism could potentially promote tissue repair processes, making repurposing cyclodextrins an intriguing avenue for therapeutic intervention in chronic wound management.

Hydrogels, that can be composed of a variety of biomaterials, including alginate, chitosan, hyaluronic acid, and gelatin, and synthetic polymers such as polyethylene glycol and polyacrylamide55,56,57,58, are gaining popularity in wound management, due to their multifunctionality, biocompatibility, and customizable properties59,60,61. Among various hydrogels, gelatin is a readily advantageous biomaterial derived from collagen, capable of mimicking the extracellular matrix (ECM), with controlled biodegradability and tissue integration, making it an ideal material to promote wound healing62,63. A number of studies have highlighted the therapeutic potential of gelatin-based hydrogels loaded with various bioactive compounds (as well as exosomes and stem cells) demonstrating improved healing outcomes by increasing rates of re-epithelialization, granulation tissue formation, macrophage polarization and neovascularization, as well as ameliorating infections and biofilm recurrence64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75.

Here, we demonstrate that the hyperproliferative epidermis of human chronic wound samples exhibit elevated levels of cholesterol sulfate using time of flight secondary ion mass spectrometry. We next extend our findings to hyperglycemic diabetic db/db mouse wounds, which exhibit perturbed lipid metabolism in comparison to their normoglycemic db/+ counterparts using bulk RNAseq analysis and demonstrate that topical cyclodextrin application to db/db mouse skin can rescue this phenotype at least partially by depleting localized cholesterol levels. Based on these findings, we developed and characterized gelatin-based hydrogels that incorporate cyclodextrins and various growth factors (EGF, PDGF or VEGF), and demonstrated a sustained over burst release of each growth factor from the hydrogel system. Finally, we demonstrate that a combination of growth factor with cyclodextrin hydrogels accelerate cutaneous wound closure in both human ex-vivo and splinted db/db mouse in vivo wound models. This combination hydrogel was superior in enhancing re-epithelialization and angiogenesis, in comparison to growth factor treatment alone. Therefore, targeting depletion of cutaneous cholesterol in combination with a sustained delivery of growth factors from cyclodextrin-based inclusion complexes significantly improves the bioavailability of growth factors, restores functionality of their receptors to promote multiple facets of the wound healing cascade, and promotes wound closure.

Results

Chronic wounds exhibit altered landscape of lipid species

Based on our recent findings that caveolin-1 (Cav1) levels are highly upregulated in non-healing chronic wounds31, coupled with Cav1 localization to cholesterol and sphingomyelin rich regions in cellular membranes, we postulate that perturbation of cholesterol, by statins and cyclodextrins, could facilitate directional cell migration and subsequent wound closure31,40,44. Thus, we sought to determine if human acute and chronic wounds also show changes in cholesterol metabolism. We first analyzed human biopsies of acute and chronic wounds by RNAseq76,77 and found that multiple biological pathways participating in cholesterol metabolism are predicted to be induced in chronic wounds (Fig. 1), which is consistent with our previous findings78. Here, we show spatial changes in other lipid families including long chain fatty acids (FA 24:0, 25:0, 26:0, and 28:0), ceramides, sphingomyelin (SM) and phoshatidylethanolamine (PE). We demonstrate that as the acute wound re-epithelializes (validated by keratin-14 staining) (Supplementary Fig. 4), basal keratinocytes devoid of cornified layer (validated by absence of filaggrin staining) (Supplementary Fig. 4) start producing increased levels of cholesterol and PE, but not ceramides or long chain fatty acids, whose levels are not detectable past the wound edge (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, cholesterol, FAs and ceramides appear to be present primarily in the epidermal cells, whereas SM and PE appear to be in both dermis and epidermis. Moreover, SM seems to have a very peculiar spatial localization whereby in the re-epithelialized epidermis where it exhibits a continuous expression pattern, while away from the wound edge it appears to be more fragmented (Fig. 2a inset). However, due to the limitations in spatial resolution of our method, the exact localization of epidermal layer(s) of SM cannot be further dissected. Interestingly, when we applied the same approach to chronic wound samples, we observed dramatic changes in both pattern and localization of different lipid species in comparison to ex vivo acute wounds. For example, we observed an induction in levels of cholesterol in chronic wounds, along with a more pronounced localization of PE and SM in the dermal compartment of skin, while long-chain FAs and ceramides exhibited increased levels and primarily cornified and granular layers localization in chronic wounds. (Fig. 2b, c).

Time of flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) was used to spatially map lipid species in a healed acute wound, and b non-healing chronic wound with corresponding horizontal and vertical profiles for each lipid category (n = 3 biological specimens form independent donors). c Quantification of lipid species identified by ToF-SIMS using peak areas normalized to total ion current (n = 4 samples plotted as means with error bars corresponding to standard deviation, ****p < 0.0001, One-way Analysis of Variance followed by Tukey’s HSD). (AW Acute wound, CW Chronic wound).

The perturbed lipid homeostasis found in db/db mouse wounds is restored by topical cyclodextrin application

To better characterize the role of lipid homeostasis in physiological and metabolic syndrome-associated changes in wound healing, we utilized leptin receptor-deficient (db/db) mice as a model of type 2 diabetes mellitus and delayed wound closure79,80. To assess changes in gene expression corresponding to lipid metabolism and homeostasis, we used bulk RNAseq and diabetic mouse wound model in vivo. Diabetic mouse wounds were incubated in the presence or absence of topically applied cholesterol disruptor, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) and analyses was performed on the following wounds: (a) day 5 db/+ vs day 0 db/+ (non-diabetic control), (b) day 5 db/db vs day 5 db/+ (diabetic wounds), and c) day 5 db/db+ MβCD treated vs day 5 db/db (treated, diabetic) (Fig. 3a). Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) demonstrated a striking difference in a number of signaling pathways and biological functions relating to lipid metabolism and signaling whereby non-diabetic wounds (db/+ mice) exhibited a stark suppression of pathways and functions involved in lipid metabolism, while diabetic (db/db mice) showed induction of the various biological pathways including fatty acid metabolism, oxidation of lipids, accumulation of lipids, quantity of steroids, concentration of cholesterol and hydrolysis of fatty acids (among others) (Fig. 3b). Moreover, topical MβCD-treated diabetic wounds exhibited reversal of major pathways associated with lipid metabolism, restoring a pattern similar to control acute wounds (Fig. 3b). To further understand how MβCD reverses diabetic lipid metabolism to resemble a non-diabetic state during wound healing, we focused on the genes that are both shared between non-diabetic wounds (db/+ mice) and MβCD-treated diabetic wounds and involved in fatty acid metabolism (Fig. 3c, d), and then compared these networks to diabetic wounds (Fig. 3e). Our analysis identified 21 genes shared between non-diabetic and MβCD-treated wounds (Fig. 3c, d). Among these, 19 genes exhibited the same expression pattern, being downregulated in both non-diabetic and MβCD-treated wounds (Fig. 3c, d). This suggests that these 19 genes are key effectors in the MβCD-induced reversal of the lipidomic phenotype to a control-like state. In contrast, in diabetic wounds, these genes are either upregulated or not regulated at all, leading to increased pathway activity (Fig. 3e). We validated expression patterns of Fabp3 and Pvalb genes from these networks by RT-qPCR (Fig. 3f). Further, we applied the same approach to study the shared gene network involved in lipid synthesis between control, non-diabetic wounds and MβCD-treated wounds (Supplementary Fig. 1). IPA analysis identified 27 shared genes between these two datasets, with 24 of them being regulated in the same direction—their expression is decreased leading to suppression of synthesis of lipids (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Conversely, in diabetic wounds the expression of these genes either increased or not regulated, resulting in induction of synthesis of lipids (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Together, these data support the notion that altered lipid metabolism plays a significant role in delaying cutaneous wound healing in db/db mice which can be rescued by topical administration of cyclodextrins.

a Venn diagram displaying number of genes in common between wounds harvested at day 5 vs day 0 from db/+ mice (I), wounds harvested from db/db vs db/+ mice at day 5 (II), and wounds harvested at day 5 from db/db mice that were topically treated with Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) vs vehicle (III); b Heatmap of functions and pathways exhibiting directionality based on z-scores. z-score represents the predicted directionality of the enriched pathways or functions (z-score ≥ 2 is considered as induced). Network analysis of shared genes associated with fatty acid metabolism between c day 5 vs day 0 from db/+ mice and d wounds harvested at day 5 from db/db mice that were topically treated with MβCD vs vehicle, and comparing with e wounds harvested from db/db vs db/+ mice at day 5. Green – decreased gene expression; red – increased gene expression; gray – not regulated; blue – predicted suppression; orange – predicted activation. f Validation of gene expression levels by qRT-PCR [n = 3 wounds, plotted as means with error bars corresponding to standard deviation, *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001; Two-way Analysis of Variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison testing].

Topical cyclodextrin disrupts cholesterol levels in diabetic wounds to accelerate wound closure

To assess whether wounds treated topically with MβCD exhibit altered levels of cholesterol, we first utilized filipin staining to visualize changes in free cholesterol of our wound samples. We observed that vehicle treated db/db mouse wounds exhibited membranous localization, while topically treated MβCD skin samples exhibited not only lower levels of free cholesterol, but also a change in spatial distribution, whereby these samples exhibited primarily cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 4a). Next, we quantified levels of cholesterol in vehicle vs. MβCD treated wounds and confirmed downregulation of cholesterol levels observed by filipin staining (Fig. 4b). Lastly, we utilized ToF-SIMS to determine changes in spatial localization of total cholesterol and observed similar trends, namely that topical MβCD treatment perturbed levels of cholesterol, as evidenced by lower levels cholesterol sulfate in epidermal cells (Fig. 4c).

a Filipin staining confirms reduced free cholesterol levels in MβCD treated mouse wounds (scale bar = 25 µm). b Total cholesterol levels from diabetic mouse wounds (including free cholesterol and cholesterol esters) were quantified by fluorometry and found to be diminished in MβCD treated mouse wounds [n = 9 from three technical replicates × three biological replicates, plotted as means with error bars corresponding to standard deviation]. c Representative images of ToF-SIMS analysis demonstrating penetration of cyclodextrin through multiple layers of the epidermis to diminish total cholesterol levels in healthy human skin.

As a result, we decided to pursue cyclodextrin as a potential approach to accelerate cutaneous wound closure and formulated a gelatin-based hydrogels that incorporates it. Because it has recently been reported that 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HβCD) is a safer and more tolerable alternative to MβCD with similar ability to extract membrane cholesterol54, we evaluated the biocompatibility of both cyclodextrins to select the best treatment option. First, we treated both primary human keratinocytes (Fig. 5a) and fibroblasts (Fig. 5b) with increasing concentrations of HβCD and MβCD and observed significant cell death starting to occur around 25 mM HβCD as opposed to ~2 mM MβCD, respectively. Next, we assessed their ability to remove cholesterol from primary human keratinocytes when integrated into gelatin hydrogel and observed similar capacity to deplete cholesterol from either HβCD or MβCD (Fig. 5c). Therefore, HβCD was selected for further experiments to assess its ability to accelerate cutaneous wound closure in diabetic mouse model. When applied to splinted db/db mouse wounds, we observed that HβCD exhibited comparable closure rates to that of rhPDGF-BB confirmed by quantification of migrating epithelial tongues from H&E-subsequent sections (Fig. 5d). Functionally, we validated that our HβCD-containing hydrogels downregulated expression of Cav1 at both mRNA and proteins levels (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Viability assays from a primary human keratinocytes and b primary human fibroblasts depict increased tolerability of HβCD over MβCD [n = 9 from three technical replicates × three biological replicates, plotted as means ± SD]. c Total cholesterol levels from primary human keratinocytes seem very similar after treatment with either 2 mM HβCD and 2 mM MβCD [n = 9 from three technical replicates × three biological replicates, plotted as means ± SD, **p < 0.01, One-way Analysis of Variance]. Incorporation of HβCD into gelatin-based hydrogels accelerates wound closure in a splinted db/db mouse similar to that of rhPDGF based on d H&E staining and quantification of migrating epithelial tongues [n ≥ 6 wounds, plotted as bars representing means with error bars corresponding to standard deviation, *p < 0.05, Two-way Analysis of Variance, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison testing]. Scale bar = 500 µm.

HβCD hydrogels improve efficacy of growth factor therapies in accelerating cutaneous wound closure in ex vivo human skin model

Based on the results previously published37,38,39,40 and data presented above we postulate that incorporating growth factors into topical gelatin-HβCD hydrogels may release sequestered growth factor receptors and facilitate their signaling, thus promoting wound closure. Moreover, we posited that incorporation of growth factors into cyclodextrins could form inclusion complexes and thus shield against enzymatic degradation of various proteases known to be elevated in the chronic wound fluid81,82, thus providing their sustained release and improving their therapeutic efficacy. To test this, we first assessed biodegradability of our gelatin-HβCD hydrogels by exposing them to a simulated chronic wound fluid (CWF) loaded with collagenase [10U/ml] and gelatinase [10 µg/ml]. By varying the ratio of the catalysts EDC/NHS to gelatin, we succeed in development of hydrogels with varying degrees of swelling and degradation when exposed to CWF, where a ratio of 1:1 (formulation A1) resulted in high degrees of swelling, while a ratio 10:1 (formulation B1) resulted in more modest degrees of swelling resulting in more stable hydrogels (Fig. 6a). Moreover, exposure of the two hydrogel formulations to CWF resulted in complete degradation of formulation A1 within 24 h, whereas formulation B1 was more stable and lasted for 5 days of exposure to CWF before it exhibited complete degradation (Fig. 6b).

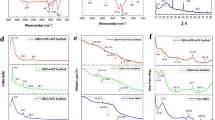

a Increasing the ratio of EDC/NHS to gelatin decreases the swelling capacity of gelatin hydrogels [Error bars correspond to standard deviations from three hydrogels with statistical significance assessed using 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison testing, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001]. b Hydrogels constructed with 10:1 (EDC:Gelatin) exhibited better overall stability in comparison to 1:1 formulation in both simulated normal wound fluid and chronic wound fluid (CWF) [n = 3 gels, plotted as bars representing means ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, Two-way Analysis of Variance, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison testing]. c Introduction of multiple types of growth factors (EGF, PDGF or VEGF) into HβCD promotes a sustained release in comparison to hydrogels without HβCD at multiple time points tested [n = 3 gels, plotted as means over a period of 5 days ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, Two-way Analysis of Variance, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison testing]. d Inclusion of EGF into HβCD hydrogels protects them from degradation and allows for increased bioavailability [n = 3 gels, plotted as means over a period of 5 days with error bars corresponding to standard deviation, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, Two-way Analysis of Variance, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison testing].

Next, we utilized formulation B1 for growth factor release assays. We used ELISA to test levels of growth factor cumulative release into the media (PBS) from slow-degrading gelatin hydrogels in presence or absence of HβCD loaded with either EGF, PDGF-BB, or VEGFa over a period of 5 days. As expected, incorporation of each growth factor into gelatin-HβCD hydrogels produced a more sustained release over the 5 d period, whereas in gelatin gels alone, cumulative release tended to plateau at ~48 h time point (Fig. 6c). Next, we used a similar approach but performed the testing in the presence of chronic wound fluid containing collagenase and gelatinase83,84,85,86,87. Interestingly, we observed that encapsulation of any growth factor into HβCD shielded these growth factors from enzymatic degradation (at least partially), thus enhancing their bioavailability (Fig. 6d).

Next, ex vivo human skin wounds were treated topically with a single application of either vehicle (gelatin hydrogel alone), HβCD-gelatin hydrogel, or EGF-GA hydrogel, and harvested 96 h post-wounding. As expected, incorporation of EGF into gelatin-HβCD hydrogels accelerated re-epithelialization as quantified by measuring the lengths of the migrating epithelial tongues (Fig. 7a). To validate that the EGF released was functionally active, we performed immunoblot analysis using total and phosphorylated forms of EGF-receptor (EGFR), as well as its downstream target (ERK1/2). We observed that EGF released by our hydrogels was indeed bioactive via induction of phosphorylated levels of both EGFR and ERK1/2 (Fig. 7b, c). Since angiogenesis is one of the key processes that support wound healing, we next assessed expression of genes involved in angiogenesis (namely CD31, CD34, VEGFa and VEGFR2) and observed a significant induction of expression at the mRNA level upon incorporating EGF into HβCD hydrogels (Fig. 7d) and then validated elevated levels of CD31 positive blood vessels in the same tissues (Fig. 7e).

a Encapsulating EGF into HβCD promotes wound re-epithelialization based on quantification of migrating epithelial tongues from H&E images [n = 4 with each point in the bar represents an independent skin donor, with bar graphs presented as mean ± SD, One-way ANOVA: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001]. (scale bar = 500 µm) b Immunoblot analysis confirming increased bioactivity of released EGF from human ex vivo wounds treated with HβCD hydrogels. c Quantification of western blots normalized to total EGFR and total Erk1/2 for phospho-EGFR and phospho-Erk1/2 levels, respectively. d RT-qPCR validating increased expression of angiogenesis-related genes when EGF is encapsulated in HβCD hydrogels [n = 3, with each point in the bar represents an independent skin donor, bar graphs presented as mean ± SD, One-way ANOVA: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001]. e Immunostaining of human ex vivo skin confirming increased number of blood vessel cells as quantified by CD31+ staining [Error bars correspond to standard deviations from four biological specimens with statistical significance assessed using paired student t-test, **p < 0.01]. (scale bar = 50 µm).

Gelatin-HβCD hydrogels improve efficacy of growth factor therapies in accelerating cutaneous wound closure in vivo

To confirm findings from ex vivo human wound model, we used splinted db/db mouse wound model88. We administered a single topical treatment with gelatin-hydrogels containing either EGF, PDGF-BB, or VEGF in presence or absence of HβCD to splinted db/db mouse wounds and harvested the wounds at day 10 post-wounding. Representative images of gross wounds by digital planimetry exhibited induction of wound closure in wounds treated with HβCD incorporating any of the growth factors (Fig. 8a). Wound closure was assessed by H&E by measuring lengths of migrating epithelial tongues (Fig. 8b), and area of granulation tissue formation (Fig. 8c). As expected, all growth factors complexed to HβCD show a similar increase in both re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation. We next assessed whether this resulted in increased angiogenesis (similarly to ex vivo human skin wounds demonstrated above), and performed VEGFa ELISA, as well as CD31/PECAM1 immunohistochemistry staining of tissues treated with EGF in presence or absence of HβCD. We observed similar results, where incorporation of EGF into cyclodextrin hydrogels exhibited a clear induction in not only the number of CD31+ vessels (Fig. 8c, d), but also in production of VEGF (Fig. 8e).

a Images of splinted db/db mouse wounds at day 10 post wounding. b Quantification of migrating epithelial tongues from splinted db/db mouse wounds [Error bars correspond to standard deviations from 4 biological specimens with statistical significance assessed using paired 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison testing, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001]. c IHC staining and d quantification of CD31+ cells/mm2 demonstrating increased number blood vessels with HβCD + EGF treatment [Error bars correspond to standard deviations from four biological specimens with statistical significance assessed using paired student t-test, ****p < 0.0001] (E-epidermis, D-dermis; scale bar = 50 µm). d ELISA demonstrating increased levels of VEGF in splinted db/db mouse wounds upon incorporation of growth factors into HβCD hydrogels [Error bars correspond to standard deviations from four biological specimens with statistical significance assessed using paired 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison testing, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001]. (scale bar = 50 µm).

Together, these data strongly suggest that localized depletion of cholesterol synthesis compounded with incorporation EGF into cyclodextrin-based gelatin hydrogels significantly improves healing outcomes in multiple wound models, by increasing growth factor bioavailability and promoting multiple facets of the wound healing cascade. Furthermore, cyclodextrin based gelatin hydrogels provide an excellent system for sustained delivery of multiple wound healing simulating growth factors, providing a new solution to this challenging clinical problem.

Discussion

Much of what has been previously demonstrated regarding the role of lipids in cutaneous wound healing has centered around eicosanoids, leukotrienes, phospholipids, and sphingolipids, whose roles have been extensively characterized during hemostasis, inflammation, and, more recently senescence89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98. Although previous studies have compared circulating levels of high- vs low-density lipoproteins (HDL vs LDL) in acute and chronic wounds and demonstrated elevated HDL levels in healing wounds99,100, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to examine localized changes in cholesterol metabolism of acute vs chronic wounds. Here, we first utilize biopsies from chronic wound patients to demonstrate that chronic wounds exhibit upregulation of genes associated with cholesterol metabolism, and then validated the localized increase in levels of cholesterol sulfate in biopsies of chronic wound patients. We next utilized a similar approach using normoglycemic db/+ and hyperglycemic db/db mice and demonstrate similar elevation of genes regulating lipid metabolism in db/db mouse wounds, which could be rescued by localized cholesterol depletion via topical cyclodextrin treatment. Together, these data still suggest that cholesterol modulation may be a promising therapeutic strategy to treat chronic wound patients. To this end, previous studies have shown a correlation between healing outcome and systemic statin use by patients with chronic wounds, albeit this trend did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.057)101, while around the same time a different group demonstrated that statin use was independently associated with a 52% risk reduction of lower-extremity amputation102. It is arguable, however, to what extent systemic statin delivery reaches the wound microenvironment, and our group is actively pursuing this topic. Regardless, multiple avenues suggest that cholesterol modulation may improve healing outcomes of chronic wound patients.

One of the potential consequences of elevated cholesterol levels in skin is an upregulation of lipid rafts and their associated structural proteins, of which Cav1 has been demonstrated to also be upregulated in both DFUs and VLUs by our group31,44. The ramifications of elevated Cav1 expression could help explain why growth factor-based therapies have demonstrated limited success in treatment of chronic wounds, due in part to the ability of Cav1 to bind to and sequester various growth factor receptors37,38,39,40, and as such, antagonize downstream signaling via these receptors, which are crucial for physiological wound healing. Thus, we developed a strategy to incorporate growth factors and cyclodextrins into gelatin-based hydrogels, as a potential avenue to improve healing outcomes, where we posit that cyclodextrins would locally deplete cutaneous cholesterol and free growth factor receptors from Cav1 sequestration, thus allowing their cognate growth factors to potentiate more effective signaling events associated with proliferation, migration and angiogenesis (all of which play pivotal roles in wound healing). Here, we demonstrate the inclusion of any number of growth factors (including EGF, PDGF, or VEGF) into cyclodextrins can accelerate re-epithelialization and angiogenesis in splinted db/db mouse and human ex vivo skin models. Thus, these data strongly suggest that to be effective, growth factor-based therapies require removal of their cognate receptors from sequestration within lipid rafts, which could be accomplished via cyclodextrins as described here, or via statin-based approaches as described previously by our group and others31,40,44,101,102.

Our findings support a mechanistic model whereby cyclodextrins enhance wound healing by altering membrane lipid composition, particularly through depletion of cholesterol, which disrupts caveolae structure and function. Caveolin-1 (Cav1), a cholesterol-binding protein integral to the architecture of caveolae, is known to sequester several key growth factor receptors (GFRs), including EGFR, PDGFR, VEGFR, and TGFβR. This sequestration limits receptor mobility and accessibility, thereby preventing ligand-induced dimerization and signal transduction. By extracting cholesterol from the plasma membrane, cyclodextrins destabilize these lipid microdomains, leading to Cav1 displacement and redistribution of GFRs to signaling-competent membrane regions. This restoration of GFR signaling enables activation of downstream cascades such as MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT, facilitating cellular processes including migration, proliferation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling, all of which are critical for tissue repair. Additionally, cholesterol depletion modulates Rho GTPase activity, decreasing RhoA-mediated stress fiber formation while enhancing Rac1/Cdc42-driven cytoskeletal dynamics, further promoting keratinocyte motility. Other examples supporting this mechanism include the use of statins, which also inhibit cholesterol synthesis and have been shown to activate SREBP2-mediated LDL receptor expression and increase keratinocyte migration and angiogenesis. Furthermore, studies in neurodegenerative diseases have shown that cyclodextrin-mediated cholesterol extraction can rescue receptor trafficking and improve cellular signaling, reinforcing the universality of this lipid-dependent regulatory mechanism103.

The translational value of this approach lies in the selective targeting of dysfunctional cellular populations within chronic wounds, particularly basal keratinocytes at the wound edge. These cells exhibit a non-healing phenotype characterized by hyperproliferation, elevated Cav1 expression, and blunted response to growth factors. By reversing cholesterol-driven Cav1 sequestration, cyclodextrins can reprogram these cells toward a migratory, growth factor-responsive state. This strategy is particularly compelling given the failure of previous growth factor therapies to reach clinical efficacy, in part due to impaired receptor signaling5,29,30,104,105. Our data suggest that cholesterol depletion is not a universal requirement for all skin cells, but rather a targeted intervention for specific, pathologically altered subpopulations. This precision approach minimizes disruption to the normal wound environment while restoring regenerative capacity to dysfunctional compartments. Examples of cell-targeted strategies include selective depletion of cholesterol in hyperkeratotic margins while preserving dermal fibroblast integrity, or enhancing endothelial responsiveness to VEGF in ischemic ulcer beds105. Moreover, combinatorial strategies could be developed to sequentially deplete cholesterol and then stimulate specific signaling pathways, such as adding Akt or ERK activators following receptor de-sequestration.

The proposed therapeutic platform is readily translatable due to the favorable safety profile and regulatory status of its components. 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HβCD) is already FDA-approved as a pharmaceutical excipient and has demonstrated good tolerability in topical and systemic formulations. Our data establish that HβCD effectively depletes cholesterol at low micromolar concentrations, without inducing cytotoxicity in human keratinocytes or fibroblasts. Gelatin, the hydrogel matrix used here, is a biocompatible, biodegradable polymer derived from collagen and commonly used in wound dressings and drug delivery systems. Moreover, the hydrogel architecture allows for tunable degradation and sustained growth factor release, even under proteolytically active conditions such as chronic wound fluid. The combined formulation thus meets several key criteria for clinical use: biocompatibility, targeted activity, ease of application, and manufacturability under current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) conditions. Importantly, the topical mode of delivery enables high local concentrations while avoiding systemic exposure, reducing the risk of off-target effects.

In practice, gelatin-cyclodextrin hydrogels could be applied as single-use dressings or integrated into layered wound dressings with antimicrobial barriers and absorptive layers. They could also be used in postoperative wound beds or skin graft donor sites to accelerate re-epithelialization and reduce infection. Further, lyophilized hydrogel patches could be engineered for easy rehydration and activation with minimal clinical training, making them viable in both hospital and outpatient settings. Importantly, these hydrogels could be modified to include a range of adjunctive therapeutics including: (a) Antimicrobials (e.g., silver nanoparticles, mupirocin, gentamicin) to reduce bioburden and biofilm formation; (b) Anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., corticosteroids, IL-10, NSAIDs) to modulate chronic inflammation; (c) Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors (e.g., doxycycline, TIMP-mimetics) to protect ECM integrity; (d) Senolytics (e.g., navitoclax, quercetin) to target senescent cells that impair healing; (e) Angiogenic peptides or exosomes derived from stem cells to further stimulate neovascularization.

Future studies should aim to refine and personalize this therapeutic approach. Single-cell RNA sequencing or spatial transcriptomics may identify the most responsive cellular subtypes within chronic wounds, enabling better stratification of patients who might benefit from cholesterol depletion strategies. Additionally, investigation into other lipid raft-resident proteins and downstream signaling pathways may reveal further therapeutic targets or biomarkers. Beyond growth factors, cyclodextrin-based hydrogels could be adapted to co-deliver anti-inflammatory agents, senolytics, or antimicrobial compounds, addressing the multifactorial nature of chronic wounds. Incorporation into smart dressings equipped with biosensors could allow real-time monitoring of wound biochemistry and dynamic adjustment of therapy. Finally, clinical trials are warranted to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and optimal dosing of this combination therapy in chronic wound patients, with particular attention to wound type (e.g., diabetic foot ulcers vs venous leg ulcers), comorbidities, and treatment duration. Additional exploration of hydrogel modularity could include responsive release systems that adjust to pH, protease levels, or oxygenation status in the wound bed. Hydrogels could also be engineered to co-release immunomodulatory cytokines like IL-10 or IL-1Ra to reprogram the chronic inflammatory wound milieu. Pilot studies should investigate durability of the response, reapplication frequency, and potential integration with negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) systems.

In summary, our work identifies localized cholesterol modulation as a mechanistically grounded, clinically feasible strategy for enhancing growth factor responsiveness and wound closure in chronic wounds. Cyclodextrin-based hydrogels offer a versatile and translatable platform for targeted delivery of regenerative therapeutics, opening new avenues for precision wound care.

Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies (along with specific concentrations) for each experiment are listed in Supplementary Table #1. Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma, C4555), hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma, 389146), EGF (Thermo Fisher Scientific, PHG0314), PDGF-BB (Sigma, GF149), VEGF (Sigma, V7259), Gelatin (Sigma, G9391), N-Hydroxysuccinimide (Sigma, 56480), N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (Sigma, 03450), Prolong Diamond (Invitrogen, P36970), Prolong Diamond with DAPI (Invitrogen, P36971).

Gelatin hydrogel fabrication and characterization

Hydrogel fabrication was performed as previously described65,66. Briefly, Gelatin B was dissolved at 10% (w/v) in deionized sterile water and loaded with 10 µg/ml EGF, PDGF-BB, and VEGF in presence or absence of 2 mM HβCD. To incorporate growth factors into HβCD, a 10% (w/v) solution of HβCD (pH 5.5) was prepared, followed by the addition of respective growth factor at 1 mg/ml, incubation at room temperature for 2 h, centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min (to clear any unbound growth factor), filtering through 0.22 µm filter, prior to dilution and addition to gelatin solution. Equal volume of EDC/NHS activation catalysts (1 ml) were combined with gelatin solution (1 ml) for 30 min at 4 °C, after which unreacted EDC/NHS was removed by washing in PBS three times. Hydrogels were then either applied topically to either mouse/human wounds or utilized for determination of release kinetics, swelling, and biodegradability in simulated chronic wound fluid.

For determination of hydrogel degrees of swelling (DS), washed hydrogels were first immersed in PBS for 2 h, and swollen weight of the gel recorded (Ws), followed by incubation at 65 °C overnight to allow for complete water evaporation, after which the weight of the dry hydrogels was measured (Wd). Degrees of swelling were calculated as following: DS =\(\frac{{Ws}-{Wd}}{{Wd}}\). For determination of hydrogel biodegradability, weight of swollen hydrogels was recorded prior to placing onto 0.4 µm PET membranes within a 24well plate and immersing in simulated wound fluid (2% BSA, 20 mM CaCl2, 400 mM NaCl, 80 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5)106 in presence or absence of 10U/ml collagenase I and 10 µg/ml MMP9 to simulate chronic wound fluid (CWF)83,84,85. Weights of hydrogels were then measured 24, 48, 96, or 120 h post-immersion, and degradation was reported as a percentage of the initial hydrogel weight.

For determination of growth factor release from the hydrogels, gelatin hydrogels were loaded onto 0.4 µm PET membranes within a 24 well plate, submerged in PBS, and growth factor release quantified at 0, 12, 24, 48, 96 and 120 h using respective Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems, DEG00 for EGF, DBB00 for PDGF-BB, and DVE00 for VEGF). The cumulative release of growth factors was calculated as a percentage of the released growth factor over the total growth factor loaded into the hydrogels for each timepoint65.

Human skin specimens

Study participants were recruited from patients presenting to the wound clinic at the University of Miami (Miami, FL) with non-infected Venous Leg ulcers (VLU). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects enrolled in the study, and informed consent was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami (IRB protocol numbers 20180256, 20180468). All subjects (n = 11) received standard-of-care. Specimens were clinically designated by a physician as the most proximal skin edge to the ulcer bed. Control skin specimens were collected from discarded human skin tissue obtained from voluntary surgeries (n = 5 donors) at the University of Miami Hospital. Specimens obtained from VLU wound edges were stained using hematoxylin & eosin following standard protocol and assessed for the presence of epidermis and dermis, thus confirming characteristic VLUs morphology as previously described in ref. 107.

Animal procedures

All of the animal procedures were approved by and in accordance with the University of Miami Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC #22-145) as previously described31. Six-week-old female heterozygous (db/+) and homozygous (db/db) mice were purchased from Jaxon Laboratory [(B6.BKS(D)-Leprdb/J, strain #000697] and allowed to acclimatize for one week prior to validating diabetes by measuring fasting blood glucose levels three times over a period of a week (>300 mg/dL). Under anesthesia, hair on the dorsal skin of 8-week-old female mice was removed by clipping and application of chemical depilatory cream (VeetTM) for 30 s, after which the skin was cleaned with water and antiseptics. Full-thickness excisional wounds were created in the dorsal skin on both sides of the midline, after which 10 mm donut-shaped silicone splint was applied using ethyl cyanoacrylate (Krazy glue) and then sutured using Ethilon 6–0 sutures, treated topically, and covered by Tegaderm in a model previously established by the Gurtner group88. The first set of mice was topically treated with 1% MβCD (w/v) and wounds recovered 5 days post-wounding, prior to RNA isolation and subsequent RNAseq analysis. Genes involved in lipid synthesis were validated by RT-qPCR using primer sets delineated in Supplementary Table #2.

For the second set, homozygous db/db female mice were treated with either vehicle (gelatin hydrogel alone), HβCD alone, EGF, PDGF-BB, VEGF, or a combination of HβCD & growth factor encompassing gelatin hydrogel (as described above). Wound tissue was collected either on day 5 or 10 post-wounding, either fixed in 10% formalin, processed, and embedded in paraffin, or saved in RNAlater. Paraffin sections (5 µm) were stained with hematoxylin & eosin for histological analysis and immunohistochemistry experiments.

All animals were humanely euthanized using CO₂ inhalation followed by cervical dislocation, in accordance with institutional guidelines and the ARRIVE 2.0 recommendations, ensuring minimal pain and distress.

Ex vivo wounding

Healthy human skin specimens were obtained as discarded tissue from reduction surgery procedures in accordance with institutional approvals. Specifically, protocol to obtain unidentified, discarded human skin specimens was submitted to University of Miami Human Subject Research Office (HSRO). Upon review conducted by University of Miami Institutional Review Board (IRB), it was determined that such protocol does not constitute Human Subject Research. As such, this project was not subject to IRB review (under 45 CFR46.101.2). Human skin specimens from reduction surgeries were used to generate acute wounds as previously described31,44. Briefly, a 3 mm biopsy punch was used to create an acute wound within an 8 mm biopsy (n = 3 per time point), which were treated daily with media (DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum). Tissue was treated with the aforementioned hydrogels topically once, with daily media change to the underlying gauze. Next, tissue was harvested at 0 h and 96 h post wounding, flash frozen, cryosectioned (5 µm), and stained with hematoxylin & eosin for histological analysis, immunohistochemistry experiments, or spatial lipidomic profiling via ToF-SIMS.

RNAseq and IPA analysis

Preparation and sequencing of RNA libraries for db+ and db/db specimens, as well as biopsies of control human skin (n = 5) and chronic wounds (VLU, n = 11) was performed at the University of Miami’s John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics Sequencing Core. Briefly, total RNA was used as input to create ribosomal RNA-depleted libraries. Each sample was sequenced with 100-base-pair single-end reads with a minimum of 60 million read depth. FASTQ files were imported to Partek Flow Software Suite for analysis. Reads were aligned to either the mouse or human genome reference index using STAR 2.7.3a. For human data processing, gene counts were normalized to counts per million with a 0.0001 offset, and gene-specific analysis was performed using FDR step-up multiple test correction and lognormal with shrinkage (limma-trend) model response distribution to identify differentially expressed genes (DEG). For mouse data processing, gene counts were quantified using the Partek E/M annotation model and normalized using the median ratio method. For gene-specific analysis, we applied DESeq2, a widely used tool for identifying differentially expressed genes. DEGs with a p ≤ 0.05 and |fold-change| ≥ 2 were included in final pathway analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Qiagen). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was performed on differentially expressed genes, and Core Analysis was used to detect distinct and/or jointly regulated pathways and biological processes in three pairs of datasets, where I) db/+ day 5 (D5) vs db/+ day 0 (D0) wounds; II) db/db D5 vs db/+ D5 wounds; and III) db/db D5 MβCD vs db/db D5 wounds.

We utilized a similar approach for analysis of pathways from previously published human acute wound datasets76 (GSE97617) and chronic wound transcriptomic datasets we have generated (GSE279534). Briefly, study participants were recruited from patients presenting to the wound clinic at the University of Miami (Miami, FL) with non-infected Venous Leg Ulcer (VLU). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects enrolled in the study, and informed consent was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami (IRB protocol numbers 20180256, 20180468). All subjects (n = 11) received standard-of-care. Specimens were clinically designated by a physician as the most proximal skin edge to the ulcer bed. Control skin specimens were collected from discarded human skin tissue obtained from voluntary surgeries (n = 5 donors) at the University of Miami Hospital. Specimens obtained from VLU wound edges were stained using hematoxylin & eosin following standard protocol and assessed for the presence of epidermis and dermis thus confirming characteristic VLUs morphology as previously described107. Next, enrichment P values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing. Pathway and Function regulation was determined via IPA-calculated absolute Z-score > 2, an indication whether a biological process is activated or suppressed based on known literature incorporated into IPA database. The gene networks were built using the IPA builder tools, connecting and expanding the interactions between genes involved in chosen processes/functions.

Time of flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS)

ToF-SIMS of lipid species was performed as previously demonstrated78,108,109,110, where we utilized ex vivo human skin samples (n = 3) and chronic wound samples (2 venous leg ulcers and 1 diabetic foot ulcer). Glass slides containing slices were slowly warmed up to room temperature and transferred into the TOF-SIMS analysis vacuum chamber. A TOF-SIMS instrument (ION-TOF, Münster, Germany) equipped with a high spatial resolution liquid metal ion gun analytical beam (25 keV, Bi3+) was used for chemical mapping, similar to our previous report. The instrument was operated in high current bunched (HCBU) spectral mode at a current of 0.215 pA and a total primary ion dose of ∼5 × 1012 ions per cm. Charge accumulation was compensated using a low-energy electron flooding gun (21 eV). Secondary ions were detected with a hybrid detector, composed of a micro-channel plate, a scintillator, and a photomultiplier, efficiently transmitting low mass ions (m/z < 2000). A mass resolving power of m/Δm ∼6000 at m/z 400 and a spatial resolution of 1.2 µm were measured in negative polarity analyses. Secondary ion images were collected with the 2D large area stage raster mode with a field of view of 1.0 × 1.0 mm, a patch side length of 0.3 mm (total 16 patches), and a pixel density of 256 pixels per mm. Data from the TOF-SIMS were analyzed using SurfaceLab 6 software (ION-TOF, Münster, Germany). Internal calibration was achieved with OH-, CH−, CH2−, C2−, C3−, C4H− and C18H33O2 – in the negative mode, and C2H3+, C2H5+, C3H7+, C5H12N+, and C5H14NO+ in the positive mode. From sequential sections, wound re-epithelialization was validated by keratin-14 immunofluorescence staining, while differentiation of epidermal keratinocytes was validated by filaggrin immunofluorescence staining (Supplementary Fig. 4), which are used for orientation and localization of tissue relative to ToF-SIMS imaging.

Cell viability

Toxicity of MβCD and HβCD was assessed on primary human keratinocytes and primary human fibroblast using PrestoBlue HS cell viability reagent (Invitrogen, P50200) per manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 2 × 105 cells were seeded onto 96-well plates, prior to treatment with varying concentrations of either MβCD or HβCD diluted in 100 µl of cell culture medium for 24 h. Cells were washed once with PBS and incubated with PrestoBlue HS reagent diluted 1/10 (v/v) in cell culture media for 3 h prior to fluorescence readout using a microplate reader (560 nmexcitation/590 nmemission).

Filipin staining

Filipin staining of free cholesterol was carried out using Filipin staining kit (Abcam, ab133116) per manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, flash frozen murine wounds were cryosectioned at 7 µm thickness, fixed in 10% formalin for 1 hr at room temperature, prior to staining with 500 μg/ml of Filipin for 2 h at room temperature. Sections were washed with PBS prior to mounting with Prolong mounting media (without DAPI) and imaged immediately.

Total cholesterol quantification

Levels of total cholesterol after MβCD/HβCD treatment were measured using Total Cholesterol Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs, STA-390) per manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, triplicates of ex vivo human skin samples were topically treated with either 2 mM MβCD, 2 mM HβCD, or vehicle control (culture media) for 48 h prior to collection by snap freezing. Next, 10 mg of tissue were lysed and lipids extracted using 500 μl of buffer containing chloroform: isopropanol: NP40 in a 7:11:0.1 ratio, centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min, prior to air drying at 50 °C and then dissolved in 200 μl of 1x Assay Diluent. Fifty microliters of the extracted sample was combined with 50 μl of Cholesterol Reaction Reagent, incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, prior to measuring levels of total cholesterol via fluorescence microplate reader (560nmexcitation/590nmemission) along with predefined quantities of cholesterol standards.

Immunofluorescence staining

All immunofluorescence staining of either human or mouse skin was completed as previously demonstrated111. Briefly, any paraffin embedded samples were deparaffinized in xylene solutions followed by graded ethanol rehydration, while flash frozen sections were fixed in 10% formalin for 10 min and washed in PBS. Samples were then subject to antigen retrieval (citrate buffer with 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.0) for 20 min at 95 °C water bath, blocked in 10% normal goat serum, and incubated with appropriate antibodies (Supplementary Table 1) overnight in a humid chamber. The following day, slides were washed with PBSt (PBS + 0.05% Tween-20) and incubated with respective secondary antibodies conjugated to either Alexa488 or Alexa594 fluorochromes. After washing in PBSt, slides were mounted using Prolong Gold Mounting medium with DAPI. Full slides were imaged, and corresponding TIFF images were exported using an Olympus VS120 slide scanning microscope.

Immunoperoxidase staining

Staining of either human or mouse skin wounds was completed as previously described112. Briefly, any paraffin embedded samples were deparaffinized in xylene solutions followed by graded ethanol rehydration. Samples were then subject to antigen retrieval (citrate buffer with 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.0) for 20 min at 95 °C water bath, after which endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched using 3% H2O2/methanol, with non-specific binding blocked with 10% normal goat serum and incubated with appropriate antibodies (Supplementary Table 1) overnight in a humid chamber. The following day, detection and chromogenic reaction were carried out using the Universal anti-rabbit HRP-Polymer Detection system (Biocare Medical), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were counterstained using Harris hematoxylin (Leica Microsystems) and then dehydrated in graded ethanol and xylene. Full slides were imaged, and corresponding pyramidal TIFF images exported using a Morphlens One slide scanning microscope to QuPath for further analysis.

Quantification of immunohistochemical staining

Bioimage analysis was performed using QuPath bioimage analysis software, as previously described by our group and others45,112,113. Briefly, images were imported into QuPath, and regions of interest were annotated using polygon features within the software, focusing on newly granulation tissue and CD31+ staining. Analysis of positive staining was determined using positive cell detection commands within the software, quantified as DAB+ cells over hematoxylin-stained nuclei (Supplementary Fig. 3 shows sample quantification). For each murine sample, three independent sections were immunostained and quantified, resulting in quantification of anywhere between 5000 and 25,000 cells per section, whereas for each ex vivo human skin sample, this resulted in quantification of anywhere between 500 and 1175 cells per section.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

All SDS-PAGE and subsequent immunoblotting were completed as previously described44. Briefly, to isolate protein, skin samples were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-hydrogen chloride, pH 7.5, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% Triton X-100). The lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were resolved by 4–20% Criterion TGX pre-cast gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and placed in blocking buffer for 1 h (tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween-20, 5% BSA) and then probed with antibodies listed in Supplementary Table 1, followed by exposure to either goat anti-mouse IR680 (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, number 926-68070, 1:15,000, reactive toward mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 heavy/light chains and light chains of mouse IgM and IgA) or goat anti-rabbit IR800 (LI-COR Biosciences, number 926-32211, 1:15,000, reactive toward rabbit IgG heavy/light chains, rabbit IgM, and IgA light chains) secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer and imaged using iBright Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The resulting images of immunoblots were imported into Empiria Studio (version 2.0) for analysis, where red (IR680) and green (IR800) channels were then separated and converted to grayscale for easier visualization. All uncropped blots are included in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Quantitative PCR

RNA isolation and purification were performed as previously described in refs. 44,111. 1.0 µg of total RNA from HEK was reverse transcribed using a qScript cDNA kit (QuantaBio, Beverly, MA), and real-time PCR was performed in triplicates using the Bio-Rad CFX Connect thermal cycler and detection system and a PerfeCTa SYBR Green Supermix (QuantaBio, Beverly, MA). Relative expression was normalized for levels of PUM1 and GAPDH. Primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Statistical analysis

The number of positive cells and area detected were used to calculate the number of positive cells/mm2 (Supplementary Fig. 3), which were then exported to GraphPad Prism for statistical analysis. Similarly, reduction in wound area calculated from gross wound images, as well as percentage of wound closure (calculated by measuring lengths of migrating epithelial tongues over total wound area), and relative expression from RT-qPCR experiments were exported to GraphPad Prism for statistical analyses. Two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, was then used to assess statistical significance, with ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 being used as a determinant of which means among the set of means differed from the rest.

Data availability

Datasets used in this study, necessary to interpret or replicate data of this paper will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Lim, H. W. et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 76, 958–972 e952 (2017).

Nussbaum, S. R. et al. An economic evaluation of the impact, cost, and medicare policy implications of chronic nonhealing wounds. Value Health 21, 27–32 (2018).

Carter, M. J. et al. Chronic wound prevalence and the associated cost of treatment in Medicare beneficiaries: changes between 2014 and 2019. J. Med. Econ. 26, 894–901 (2023).

Queen, D. & Harding, K. Estimating the cost of wounds both nationally and regionally within the top 10 highest spenders. Int Wound J. 21, e14709 (2024).

Eming, S. A., Martin, P. & Tomic-Canic, M. Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 265sr266 (2014).

Darwin, E. & Tomic-Canic, M. Healing chronic wounds: current challenges and potential solutions. Curr. Dermatol Rep. 7, 296–302 (2018).

Burgess, J. L., Wyant, W. A., Abdo Abujamra, B., Kirsner, R. S. & Jozic, I. Diabetic wound-healing science. Medicina 57, 1072 (2021).

Frykberg, R. G. & Banks, J. Challenges in the treatment of chronic wounds. Adv. Wound Care4, 560–582 (2015).

Everett, E. & Mathioudakis, N. Update on management of diabetic foot ulcers. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1411, 153–165 (2018).

Han, G. & Ceilley, R. Chronic wound healing: a review of current management and treatments. Adv. Ther. 34, 599–610 (2017).

Schultz, G. S. et al. Epithelial wound healing enhanced by transforming growth factor-alpha and vaccinia growth factor. Science 235, 350–352 (1987).

Sasaki, T. The effects of basic fibroblast growth factor and doxorubicin on cultured human skin fibroblasts: relevance to wound healing. J. Dermatol. 19, 664–666 (1992).

Jiang, C. K. et al. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor alpha specifically induce the activation- and hyperproliferation-associated keratins 6 and 16. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 6786–6790 (1993).

Konig, A. & Bruckner-Tuderman, L. Transforming growth factor-beta promotes deposition of collagen VII in a modified organotypic skin model. Lab. Investig. 70, 203–209 (1994).

Barrientos, S., Brem, H., Stojadinovic, O. & Tomic-Canic, M. Clinical application of growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 22, 569–578 (2014).

Rodrigues, M., Kosaric, N., Bonham, C. A. & Gurtner, G. C. Wound healing: a cellular perspective. Physiol. Rev. 99, 665–706 (2019).

Garcia-Orue, I. et al. Agar/gelatin hydro-film containing EGF and Aloe vera for effective wound healing. J. Mater. Chem. B 11, 6896–6910 (2023).

Gauthier, T. et al. TGF-beta uncouples glycolysis and inflammation in macrophages and controls survival during sepsis. Sci. Signal. 16, eade0385 (2023).

Hilliard, B. A., Amin, M., Popoff, S. N. & Barbe, M. F. Potentiation of collagen deposition by the combination of substance P with transforming growth factor beta in rat skin fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 1862 (2024).

Smiell, J. M. et al. Efficacy and safety of becaplermin (recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB) in patients with nonhealing, lower extremity diabetic ulcers: a combined analysis of four randomized studies. Wound Repair Regen. 7, 335–346 (1999).

Mohan, V. K. Recombinant human epidermal growth factor (REGEN-D 150): effect on healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 78, 405–411 (2007).

Barrientos, S., Stojadinovic, O., Golinko, M. S., Brem, H. & Tomic-Canic, M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 16, 585–601 (2008).

Uchi, H. et al. Clinical efficacy of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) for diabetic ulcer. Eur. J. Dermatol. 19, 461–468 (2009).

Matsumoto, S. et al. The effect of control-released basic fibroblast growth factor in wound healing: histological analyses and clinical application. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 1, e44 (2013).

Rahim, F. et al. Epidermal growth factor outperforms placebo in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer: a meta-analysis. F1000Res 11, 773 (2022).

Thanigaimani, S., Jin, H., Ahmad, U., Anbalagan, R. & Golledge, J. Comparative efficacy of growth factor therapy in healing diabetes-related foot ulcers: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 39, e3670 (2023).

Rayment, E. A., Upton, Z. & Shooter, G. K. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) activity observed in chronic wound fluid is related to the clinical severity of the ulcer. Br. J. Dermatol. 158, 951–961 (2008).

Serena, T. E. et al. Bacterial protease activity as a biomarker to assess the risk of non-healing in chronic wounds: results from a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial. Wound Repair Regen. 29, 752–758 (2021).

Brem, H. et al. Molecular markers in patients with chronic wounds to guide surgical debridement. Mol. Med. 13, 30–39 (2007).

Pastar, I. et al. Attenuation of the transforming growth factor beta-signaling pathway in chronic venous ulcers. Mol. Med. 16, 92–101 (2010).

Jozic, I. et al. Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of caveolin-1 promotes epithelialization and wound closure. Mol. Ther. 27, 1992–2004 (2019).

Razani, B., Woodman, S. E. & Lisanti, M. P. Caveolae: from cell biology to animal physiology. Pharm. Rev. 54, 431–467 (2002).

Martin, S. & Parton, R. G. Caveolin, cholesterol, and lipid bodies. Semin Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 163–174 (2005).

Zhang, W. et al. Caveolin-1 inhibits epidermal growth factor-stimulated lamellipod extension and cell migration in metastatic mammary adenocarcinoma cells (MTLn3). J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20717–20725 (2000).

Tahir, S. A., Park, S. & Thompson, T. C. Caveolin-1 regulates VEGF-stimulated angiogenic activities in prostate cancer and endothelial cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 8, 2286–2296 (2009).

Parton, R. G. & del Pozo, M. A. Caveolae as plasma membrane sensors, protectors and organizers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 98–112 (2013).

Di Guglielmo, G. M., Le Roy, C., Goodfellow, A. F. & Wrana, J. L. Distinct endocytic pathways regulate TGF-beta receptor signalling and turnover. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 410–421 (2003).

Schwencke, C., Braun-Dullaeus, R. C., Wunderlich, C. & Strasser, R. H. Caveolae and caveolin in transmembrane signaling: Implications for human disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 70, 42–49 (2006).

Oliveira, S. D. S. et al. Inflammation-induced caveolin-1 and BMPRII depletion promotes endothelial dysfunction and TGF-beta-driven pulmonary vascular remodeling. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 312, L760–L771 (2017).

Sawaya, A. P. et al. Mevastatin promotes healing by targeting caveolin-1 to restore EGFR signaling. JCI Insight 4, e129320 (2019).

Cohen, A. W. et al. Caveolin-1 null mice develop cardiac hypertrophy with hyperactivation of p42/44 MAP kinase in cardiac fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 284, C457–C474 (2003).

Sedding, D. G. et al. Caveolin-1 facilitates mechanosensitive protein kinase B (Akt) signaling in vitro and in vivo. Circ. Res. 96, 635–642 (2005).

Yamaguchi, Y., Watanabe, Y., Watanabe, T., Komitsu, N. & Aihara, M. Decreased expression of caveolin-1 contributes to the pathogenesis of psoriasiform dermatitis in mice. J. Investig. Dermatol. 135, 2764–2774 (2015).

Jozic, I. et al. Glucocorticoid-mediated induction of caveolin-1 disrupts cytoskeletal organization, inhibits cell migration and re-epithelialization of non-healing wounds. Commun. Biol. 4, 757 (2021).

Seth, N., Abujamra, B. A., Boulina, M., Lev-Tov, H. & Jozic, I. Upregulation of caveolae-associated proteins in lesional samples of hidradenitis suppurativa: a case series study. JID Innov. 3, 100223 (2023).

Rodal, S. K. et al. Extraction of cholesterol with methyl-beta-cyclodextrin perturbs formation of clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 961–974 (1999).

Elliott, M. H., Fliesler, S. J. & Ghalayini, A. J. Cholesterol-dependent association of caveolin-1 with the transducin alpha subunit in bovine photoreceptor rod outer segments: disruption by cyclodextrin and guanosine 5’-O-(3-thiotriphosphate). Biochemistry 42, 7892–7903 (2003).

Li, X. et al. Loss of caveolin-1 impairs retinal function due to disturbance of subretinal microenvironment. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 16424–16434 (2012).

Christiansen, D. L. et al. Local simvastatin and inflammation during periodontal mini-flap wound healing: exploratory results. J. Periodontol. 94, 467–476 (2023).

Szejtli, J. Introduction and general overview of cyclodextrin chemistry. Chem. Rev. 98, 1743–1754 (1998).

Lopez, C. A., de Vries, A. H. & Marrink, S. J. Molecular mechanism of cyclodextrin mediated cholesterol extraction. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002020 (2011).

Mahammad, S. & Parmryd, I. Cholesterol depletion using methyl-beta-cyclodextrin. Methods Mol. Biol. 1232, 91–102 (2015).

Yoshinari, M. et al. Controlled release of simvastatin acid using cyclodextrin inclusion system. Dent. Mater. J. 26, 451–456 (2007).

Hinzey, A. H. et al. Choice of cyclodextrin for cellular cholesterol depletion for vascular endothelial cell lipid raft studies: cell membrane alterations, cytoskeletal reorganization and cytotoxicity. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 49, 329–341 (2012).

Anjum, S., Arora, A., Alam, M. S. & Gupta, B. Development of antimicrobial and scar preventive chitosan hydrogel wound dressings. Int. J. Pharm. 508, 92–101 (2016).

Hu, W., Wang, Z., Xiao, Y., Zhang, S. & Wang, J. Advances in crosslinking strategies of biomedical hydrogels. Biomater. Sci. 7, 843–855 (2019).

Khan, F. et al. Synthesis, classification and properties of hydrogels: their applications in drug delivery and agriculture. J. Mater. Chem. B 10, 170–203 (2022).

Serafin, A., Culebras, M. & Collins, M. N. Synthesis and evaluation of alginate, gelatin, and hyaluronic acid hybrid hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 233, 123438 (2023).

Lindholm, C. & Searle, R. Wound management for the 21st century: combining effectiveness and efficiency. Int. Wound J. 13(Suppl 2), 5–15 (2016).

Liang, Y., He, J. & Guo, B. Functional hydrogels as wound dressing to enhance wound healing. ACS Nano 15, 12687–12722 (2021).

Gounden, V. & Singh, M. Hydrogels and wound healing: current and future prospects. Gels 10, 43 (2024).

Kushibiki, T. et al. Photocrosslinked gelatin hydrogel improves wound healing and skin flap survival by the sustained release of basic fibroblast growth factor. Sci. Rep. 11, 23094 (2021).

Liu, W. S. et al. Biomembrane-based nanostructure- and microstructure-loaded hydrogels for promoting chronic wound healing. Int. J. Nanomed. 18, 385–411 (2023).

Layman, H. et al. The effect of the controlled release of basic fibroblast growth factor from ionic gelatin-based hydrogels on angiogenesis in a murine critical limb ischemic model. Biomaterials 28, 2646–2654 (2007).

Layman, H. et al. Co-delivery of FGF-2 and G-CSF from gelatin-based hydrogels as angiogenic therapy in a murine critical limb ischemic model. Acta Biomater. 5, 230–239 (2009).

Montero, R. B. et al. bFGF-containing electrospun gelatin scaffolds with controlled nano-architectural features for directed angiogenesis. Acta Biomater. 8, 1778–1791 (2012).

Notodihardjo, P. V. et al. Gelatin hydrogel impregnated with platelet-rich plasma releasate promotes angiogenesis and wound healing in murine model. J. Artif. Organs 18, 64–71 (2015).

Sakamoto, M. et al. Efficacy of gelatin gel sheets in sustaining the release of basic fibroblast growth factor for murine skin defects. J. Surg. Res. 201, 378–387 (2016).

Witherel, C. E. et al. Regulation of extracellular matrix assembly and structure by hybrid M1/M2 macrophages. Biomaterials 269, 120667 (2021).

Sharifi, E. et al. Cell loaded hydrogel containing Ag-doped bioactive glass-ceramic nanoparticles as skin substitute: antibacterial properties, immune response, and scarless cutaneous wound regeneration. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 7, e10386 (2022).

Gul, R., Mir, M. & Ali, M. N. An Appraisal of pH triggered Bacitracin drug release, through composite hydrogel systems. J. Biomater. Appl. 37, 1699–1715 (2023).

Sheng, W. et al. Sodium alginate/gelatin hydrogels loaded with adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote wound healing in diabetic rats. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 22, 1670–1679 (2023).

Tang, L. et al. GelMA hydrogel loaded with extracellular vesicles derived from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for promoting cutaneous diabetic wound healing. ACS Omega 8, 10030–10039 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. Bioprinting a skin patch with dual-crosslinked gelatin (GelMA) and silk fibroin (SilMA): an approach to accelerating cutaneous wound healing. Mater. Today Bio 18, 100550 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ag nanocomposite hydrogels with immune and regenerative microenvironment regulation promote scarless healing of infected wounds. J. Nanobiotechnol. 21, 435 (2023).

Iglesias-Bartolome, R. et al. Transcriptional signature primes human oral mucosa for rapid wound healing. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaap8798 (2018).

Marjanovic, J. et al. Dichotomous role of miR193b-3p in diabetic foot ulcers maintains inhibition of healing and suppression of tumor formation. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabg8397 (2022).

Castellanos, A., Hernandez, M. G., Tomic-Canic, M., Jozic, I. & Fernandez-Lima, F. Multimodal, in situ imaging of Ex vivo human skin reveals decrease of cholesterol sulfate in the neoepithelium during acute wound healing. Anal. Chem. 92, 1386–1394 (2020).

Michaels, J. T. et al. db/db mice exhibit severe wound-healing impairments compared with other murine diabetic strains in a silicone-splinted excisional wound model. Wound Repair Regen. 15, 665–670 (2007).

Couturier, A. et al. Mouse models of diabetes-related ulcers: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. EBioMedicine 98, 104856 (2023).

Cesari, A. et al. Improvement of peptide affinity and stability by complexing to cyclodextrin-grafted ammonium chitosan. Polymers 12, 474 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Protective effect of beta-cyclodextrin on stability of nisin and corresponding interactions involved. Carbohydr. Polym. 223, 115115 (2019).

Wysocki, A. B., Staiano-Coico, L. & Grinnell, F. Wound fluid from chronic leg ulcers contains elevated levels of metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9. J. Investig. Dermatol. 101, 64–68 (1993).

Trengove, N. J. et al. Analysis of the acute and chronic wound environments: the role of proteases and their inhibitors. Wound Repair Regen. 7, 442–452 (1999).

Fitridge, R. & Thompson, M. in mechanisms of vascular disease: a reference book for vascular specialists. (eds. R. Fitridge & M. Thompson) (Adelaide (AU); 2011).

He, C., Hughes, M. A., Cherry, G. W. & Arnold, F. Effects of chronic wound fluid on the bioactivity of platelet-derived growth factor in serum-free medium and its direct effect on fibroblast growth. Wound Repair Regen. 7, 97–105 (1999).

Yager, D. R. et al. Ability of chronic wound fluids to degrade peptide growth factors is associated with increased levels of elastase activity and diminished levels of proteinase inhibitors. Wound Repair Regen. 5, 23–32 (1997).

Galiano, R. D., Michaels, J. T., Dobryansky, M., Levine, J. P. & Gurtner, G. C. Quantitative and reproducible murine model of excisional wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 12, 485–492 (2004).

McDaniel, J. C., Belury, M., Ahijevych, K. & Blakely, W. Omega-3 fatty acids effect on wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 16, 337–345 (2008).

Arun, S. N. et al. Cell wounding activates phospholipase D in primary mouse keratinocytes. J. Lipid Res. 54, 581–591 (2013).

Brogliato, A. R. et al. Critical role of 5-lipoxygenase and heme oxygenase-1 in wound healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 134, 1436–1445 (2014).

Arantes, E. L. et al. Topical docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) accelerates skin wound healing in rats and activates GPR120. Biol. Res. Nurs. 18, 411–419 (2016).

Babaei, S. et al. Omegaven improves skin morphometric indices in diabetic rat model wound healing. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Wound Spec. 9, 39–45 (2017).

Brandt, S. L. et al. Excessive localized leukotriene B4 levels dictate poor skin host defense in diabetic mice. JCI Insight 3, e120220 (2018).

Guimaraes, F. R. et al. The inhibition of 5-Lipoxygenase (5-LO) products leukotriene B4 (LTB(4)) and cysteinyl leukotrienes (cysLTs) modulates the inflammatory response and improves cutaneous wound healing. Clin. Immunol. 190, 74–83 (2018).

Aoki, M. et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate facilitates skin wound healing by increasing angiogenesis and inflammatory cell recruitment with less scar formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 3381 (2019).

Bollag, W. B. et al. Dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol accelerates corneal epithelial wound healing. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61, 29 (2020).

Danby, S. G. et al. Enhancement of stratum corneum lipid structure improves skin barrier function and protects against irritation in adults with dry, eczema-prone skin. Br. J. Dermatol. 186, 875–886 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Association of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and wound healing in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Chin. Med. J.135, 110–112 (2022).

Gordts, S. C., Muthuramu, I., Amin, R., Jacobs, F. & De Geest, B. The impact of lipoproteins on wound healing: topical HDL therapy corrects delayed wound healing in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Pharmaceuticals 7, 419–432 (2014).

Fox, J. D. et al. Statins may be associated with six-week diabetic foot ulcer healing. Wound Repair Regen. 24, 454–457 (2016).

Yang, T. L. et al. Association of statin use and reduced risk of lower-extremity amputation among patients with diabetes: a nationwide population-based cohort observation. Diabetes Care 39, e54–e55 (2016).

Coisne, C. et al. Cyclodextrins as emerging therapeutic tools in the treatment of cholesterol-associated vascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 21, 1748 (2016).

Wu, L., Xia, Y. P., Roth, S. I., Gruskin, E. & Mustoe, T. A. Transforming growth factor-beta1 fails to stimulate wound healing and impairs its signal transduction in an aged ischemic ulcer model: importance of oxygen and age. Am. J. Pathol. 154, 301–309 (1999).