Abstract

Lassa fever virus (LASV), a member of the Arenavirus family, is the etiological agent of Lassa fever, a severe hemorrhagic disease that causes considerable morbidity and mortality in the endemic areas of West Africa. LASV is a rodent-borne CDC Tier One biological threat agent and is on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Priority Pathogen list. Currently, no FDA-licensed vaccines or specific therapeutics are available. Here, we describe the efficacy of a deactivated rabies virus (RABV)-based vaccine encoding the glycoprotein precursor (GPC) of LASV (LASSARAB). Nonhuman primates (NHPs) were administered a two-dose regimen of LASSARAB or an irrelevant RABV-based vaccine to serve as a negative control. NHPs immunized with LASSARAB developed strong humoral responses to LASV-GPC. Upon challenge, NHPs vaccinated with LASSARAB survived to the study endpoint, whereas NHPs in the control group did not. This study demonstrates that LASSARAB is a worthy candidate for continued development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

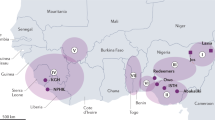

Lassa fever virus (LASV) is one of many emerging biosafety level-4 (BSL-4) hemorrhagic viruses, for which no approved vaccine exists. LASV is endemic to West Africa1, where it is maintained by its rodent reservoir, Mastomys natalensis2,3. The virus is most frequently transmitted to humans when they come into proximity with infected rodents3,4. However, human-to-human transmission can occur, most often in nosocomial settings upon contact with contaminated bodily fluids5,6. It is estimated that between 300,000–500,000 people are infected with LASV annually1, with an overall case fatality rate (CFR) of 1–2%2. In contrast, the CFR increases significantly for hospitalized patients, with one study reporting a 69% CFR in Sierra Leone7. The disease caused by LASV infection, Lassa fever (LF), is similar to other viral hemorrhagic fevers, starting with flu-like symptoms, such as fever, sore throat, and headache, and in severe cases, progressing to vascular leakage and multiple organ failure8. While many patients survive the disease, some develop severe sequela, with a third of patients developing sensorineural hearing loss that is permanent in some cases9. Given the severity of LF and lack of approved vaccines, LASV is categorized as a high-priority pathogen by various United States (US) government agencies, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).

LASV is an arenavirus, and thus has a bi-segmented, ambisense RNA genome that codes for four proteins. One of these proteins, the glycoprotein precursor (GPC), is proteolytically cleaved by a host protease into two glycoproteins (GP1 and GP2), which are present on the surface of the virion and used for attachment and entry into cells10. Given the easy accessibility of the glycoproteins to the immune system and its indispensable function in the LASV lifecycle, the GPC gene is an attractive target for LASV vaccine development. In fact, neutralizing antibodies targeting the glycoproteins were shown to protect both guinea pigs and non-human primates (NHPs) from lethal LASV challenge11,12. Additionally, several vaccine candidates targeting GPC were protective in various LASV challenge models13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. However, many of these vaccine strategies have disadvantages. DNA vaccines have been successful in protecting guinea pigs and NHPs from lethal infection and have advanced to human clinical trials, but they are poorly immunogenic without the use of specialty delivery techniques, such as electroporation14,23,24,25,26. RNA-based vaccines such as alphavirus RNA replicon vaccines require cold-chain storage. Live viral vectors have the potential to develop mutations, rendering them pathogenic, and are typically not suitable for immunization of vulnerable populations including immunocompromised individuals and pregnant patients. Thus, a need for the development of alternative vaccine strategies that mitigate these issues remains.

Rabies virus (RABV) is a promising vaccine platform that has advantages over the vaccine platforms described above. RABV has been successfully used as a vaccine platform for various pathogens27, including LASV28 and a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine, CORAVAX™, that has been tested in a phase I human clinical trial29. The rabies vaccine is administered as an inactivated vaccine, has a well-established safety profile, and provides long-term protective immune responses to the rabies antigens30. RABV shares endemic regions with many pathogens, including LASV, which greatly increases the impact this bivalent vaccine could have in the affected areas. An inactivated RABV vectored vaccine can be lyophilized and remains stable when stored at various temperatures, including at 50 °C for up to two weeks31. Therefore, the RABV platform is an excellent choice for a LASV vaccine.

The correlates of protection for LASV have not yet been defined. Studies investigating the mechanism of protection of various vaccines have produced different results. Both a live Mopiea-Lassa reassortment virus (ML29) and live recombinant vaccinia virus expressing LASV-GPC elicited robust cellular responses without humoral responses and were protective in a challenge model17,32. In contrast, another protective live vaccine platform, recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus with its glycoprotein replaced with LASV-GPC (VSVΔG/LVGPC), was shown to induce both cellular and humoral responses22. Finally, we previously developed a chemically inactivated RABV-based vaccine expressing all the RABV viral proteins and the LASV-GPC (LASSARAB) that was shown to protect mice against challenge with a VSV-based surrogate virus for LASV through Fcγ-receptor mediated functions of antibodies (i.e., antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity [ADCC] or phagocytosis [ADCP])28. Thus, it seems that vaccine-mediated protection against LASV can occur through various mechanisms. While different platforms appear to elicit protection through diverse mechanisms, one commonality between the platforms is a poor neutralizing antibody response after vaccination17,22,28,32. This is not surprising given the absence of neutralizing antibodies seen in many convalescent LASV patients33.

We previously demonstrated that when LASSARAB was administered to NHPs, it elicited strong antibody responses to both LASV-GPC and RABV glycoprotein (G) for up to a year post immunization (pi)34. In the current study, our goal was to test the vaccine efficacy of LASSARAB in a lethal LASV NHP challenge model. To this end, we immunized NHPs with LASSARAB or CORAVAX™35 (an irrelevant RABV-based vaccine) as a negative control and challenged the NHPs at day 70 pi with LASV. All the LASSARAB immunized NHPs survived the LASV challenge, while controls developed severe clinical signs and reached euthanasia criteria before the end of the study. These results indicate that LASSARAB is a good candidate for LASV vaccine clinical trials.

Results

LASSARAB induces a strong humoral response before challenge

In our previous studies, we adjuvanted LASSARAB with glucopyranosyl lipid A in SE (GLA-SE)28,34, which is an adjuvant similar to the adjuvant used in this study, monophosphoryl lipid A, 3D(6 A)-PHAD, in a 2% stable emulsion (PHAD-SE), but is not commercially available. To determine whether these two adjuvants could be used interchangeably with LASSARAB, we performed an immunogenicity experiment in mice (Supplementary Fig. 1). Groups of ten mice were immunized with either LASSARAB or FILORAB1, a rabies-based Ebola virus vaccine36, and five mice from each group received GLA-SE adjuvant, with the other five receiving PHAD-SE adjuvant. There was no difference between adjuvants in the EC50 of anti-LASV immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody titers at any point pi (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Both adjuvants are toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 agonists and thus should elicit a Th1-biased immune response37,38. Both LASSARAB groups regardless of adjuvant elicited an antibody response with a bias towards a Th1 response as indicated by an isotype ratio of IgG2c/IgG1 greater than 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1c–e). The mice immunized with FILORAB1 did not show any immune responses against LASV-GPC. Thus, the immune responses elicited by LASSARAB adjuvanted with PHAD-SE are comparable to those with GLA-SE adjuvant.

Twelve cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) were used in this study: six (two males and four females) immunized with LASSARAB and six (four males and two females) immunized with CORAVAX™, a rabies-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine35 (Fig. 1). Three of the NHPs (NHPs 7, 8 and 9) were previously immunized with the RABV vaccine before the start of this study, and thus were placed into the CORAVAX™ group. The remaining NHPs were randomly assigned into the vaccine groups. NHPs were administered 150 µg of each vaccine, adjuvanted with 15 µg of PHAD-SE. Immunizations were given on days 0 and 28 as outlined in Fig. 1b, c. The antibody responses were first measured against LASV-GPC and RABV-G. Antibody responses against both antigens could be seen starting on day 14 pi, although the LASV-GPC-specific responses were only significantly higher than the background seen in the CORAVAX group on day 28 pi. Peak antibody titers were observed at day 42 pi for both LASV-GPC and RABV-G (Fig. 2). Only NHPs receiving LASSARAB developed significant antibody responses against LASV-GPC, while both groups of NHPs developed binding antibody responses against RABV-G as demonstrated through both 50% effective concentration (EC50) antibody titers (Fig. 2a) and antibody endpoint titers (Fig. 2b).

a Schematic of vaccine constructs with all RABV and foreign proteins indicated. Red diamond indicates the attenuating mutation at amino acid 333 of RABV-G. N nucleoprotein, P phosphoprotein, M matrix protein, G glycoprotein, L RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, LASV-GPC Lassa virus glycoprotein precursor, SARS-CoV-2 S1 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike protein subunit 1, ED31 31 amino acids of the ectodomain, TM transmembrane domain, CD cytoplasmic domain. b Table outlining the vaccine groups and expected experimental outcomes. c Experimental timeline. Red droplets indicate blood draws, rhabdovirus and syringe indicate immunization, and the arenavirus represents the LASV challenge. Figure made with BioRender.com.

Antibody responses against LASV-GPC and RABV-G were measured through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). a Antibody EC50 titers over time for LASV-GPC and RABV-G. b Antibody endpoint titers over time for LASV-GPC and RABV-G. Samples from each NHP were run in triplicate, and error bars are the mean with standard deviation (SD). The Mann-Whitney nonparametric T-test was used to determine statistical differences between groups at each time point. Where significance is not noted, samples have no significant difference. ****<0.0001; ***0.0002; **0.0021; *0.0332; P > 0.05 ns, not significant. LOD limit of detection.

Functionality of antibodies induced by LASSARAB immunization

It was previously demonstrated that the anti-LASV-GPC antibodies elicited by LASSARAB immunization in mice were non-neutralizing with Fc-mediated functions28. To confirm whether LASSARAB immunization of NHPs produced antibodies with non-neutralizing Fc functions, a series of functional antibody assays were conducted. First, a virus neutralization assay (VNA) using a VSV reporter virus pseudotyped with LASV-GPC (ppVSV-ΔG-GPC) was performed. Neither sera from the LASSARAB immunized NHPs, nor from the CORAVAX™ immunized control NHPs showed neutralizing activity against ppVSV-ΔG-GPC, while human monoclonal 37.7H had strong neutralizing activity as previously described28,39 (Fig. 3a). To determine whether these antibodies had Fc-mediated functions, an ADCC assay was performed using cells infected with VSV expressing LASV-GPC (VSV-ΔG-LASV-GPC) and treated with a mixture of NHP sera and a Jurkat reporter cell line expressing human Fcγ receptor IIIa (FcγRIIIa). The human FcγRIIIa ADCC activation Reporter Bioassay measures the binding of the Fc portion of the antibody to the human FcγRIIIa of the effector cells (Jurkat), which results in a quantifiable luminescence signal from the nuclear factor of an activated T-cell (NFAT) pathway. Activation of the luciferase activity in the effector cells was used as an indicator of ADCC activity. Sera from NHPs immunized with LASSARAB showed strong ADCC activity towards VSV-ΔG-LASV-GPC infected cells, whereas sera from control NHPs immunized with CORAVAX™ only showed background signal activity (Fig. 3b). These data indicate that, as in mice, NHPs immunized with LASSARAB induce non-neutralizing antibodies with Fc-mediated functions.

Assays measuring neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibody functions. a Pseudotype virus neutralization assay (VNA) for LASV with sera from immunized NHPs and human monoclonal anti-LASV-GPC antibody 37.7H as a positive control. Error bars represent standard deviation. b Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) assay for LASV with sera from immunized NHPs. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. c Rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT) to measure neutralizing antibodies against RABV (strain CVS-11). Neutralizing titers are represented as international units per mL (IU/mL). 0.5 IU/mL, the WHO threshold suggestive of protection, is indicated by the dotted line. NC negative control, ns not significant.

Whereas, the role of neutralizing antibodies for protection in LASV is unclear, high titers of neutralizing antibodies are the correlate of protection for RABV40. To measure RABV neutralizing antibody titers, we performed the well-established rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT), where a neutralizing titer of 0.5 international units (IU)/mL or more is considered protective by the WHO definition. Starting on day 14 pi, all NHPs regardless of which vaccine they received had RABV-neutralizing antibody titers well above the 0.5 IU/mL threshold, which increased throughout the course of the experiment (Fig. 3c). Additionally, we confirmed that NHPs 7, 8 and 9 in the control CORAVAX™ group were previously immunized against RABV before the start of the study, as demonstrated by the anti-RABV antibody titers at day 0 (Figs. 2b, 3c).

LASSARAB protects NHPs from lethal LASV challenge

On day 70 pi, the NHPs were challenged with 1000 plaque forming units (PFU) of LASV Josiah strain41. While the CORAVAX™ immunized NHPs reached endpoint criteria between days 10 and 19 post challenge (pc), none of the LASSARAB immunized NHPs reached endpoint criteria at any point during the study (Fig. 4a). In addition to requiring euthanasia, all CORAVAX™ NHPs demonstrated high clinical scores, weight loss, and an elevated temperature followed by a drastic drop throughout the course of the challenge (Fig. 4b–d). In contrast, only one LASSARAB NHP, NHP 4, displayed clinical signs that were mild and resolved quickly (Fig. 4b). Additionally, all LASSARAB immunized NHPs maintained weight throughout the challenge and only had a brief increase in body temperature (Fig. 4c, d). NHP 4 showed the greatest weight loss and decrease in temperature of the LASSARAB group, correlating with the display of clinical signs (Fig. 4b–d).

Clinical measurements of LASV disease throughout the NHP challenge study. a Kaplan-Meyer survival curves. Significance between groups was determined using the log-rank Mantel-Cox test (***P = 0.0004). b Clinical scores for individual NHPs. c Changes in weight over time for individual NHPs. d Group average changes in body temperature over time.

LASSARAB immunization reduces viral loads

To quantitate viremia pc, viral loads were measured in serum by plaque assay (actively replicating LASV) and quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR, presence of viral RNA). All CORAVAX™-immunized NHPs had measurable viral replication starting on day 6 pc that persisted until euthanasia (Fig. 5a). Two LASSARAB-immunized NHPs did not have detectable replicating LASV in the blood and the other four NHPs had low viral loads that were rapidly cleared (Fig. 5a). NHP 4, the only NHP displaying clinical signs had the longest viremia of the LASSARAB vaccinated NHPs (Fig. 5a). Both LASSARAB and CORAVAX™ immunized NHPs had detectable viral RNA in the blood starting at day 3 pc (Fig. 5b). Viral RNA was cleared from the blood in LASSARAB-vaccinated NHPs by day 21 for four NHPs and day 28 for the remaining two NHPs. By contrast, viral RNA persisted in the blood of CORAVAX™-vaccinated NHPs throughout the course of LASV infection (Fig. 5b). Thus, vaccination with LASSARAB greatly reduced viral loads compared to vaccination with CORAVAX™.

a Serum viremia post-challenge (pc) measured via plaque assay. Pfu, plaque forming units. b Plasma PCR CT values pc measured by qRT-PCR. The limit of detection for this assay is 42 CT and the line at 37 CT represents the cutoff for positivity. Stars represent significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups as determined by multiple unpaired t-tests.

Humoral responses are boosted post challenge

Antibody responses were measured to LASV-GPC following LASV-exposure to determine how LASSARAB vaccination impacted the humoral responses after challenge. Two of the CORAVAX™ control NHPs did not develop LASV-GPC-specific antibodies before euthanasia, while the other four developed only low antibody titers starting on day 10 pc (Fig. 6a). In contrast, all the LASSARAB-immunized NHPs had low antibody titers on days 0–6 pc and substantially increased antibody titers starting at day 10 pc, peaking at day 14 pc (Fig. 6a). These data indicate that LASSARAB immunization primed the immune system, resulting in this rapid recall response in antibody titers pc.

a Antibody responses against LASV-GPC pc. Total IgG EC50 antibody titers throughout the course of the challenge study. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Statistics at each timepoint were determined by the Mann–Whitney non-parametric T-test. Where significance is not noted, samples have no significant difference. ****<0.0001; ***0.0002; **0.0021; *0.0332; P > 0.05 ns, not significant. b The serum neutralization levels were measured in a microneutralization assay using three-fold serial dilutions starting at 1:10. The bar graph shows LASV Neut50 endpoint titer (EPT), defined as the highest serum dilution achieving a neutralization of at least 50 percent of the control LASV virus. The error bars represent the standard deviation, with the x-axis representing the sampling timepoint and y-axis, the reciprocal serum dilutions. c Percent inhibition curves were plotted in GraphPad Prism 9.4.0 with reciprocal serum dilution on the x-axis and percent inhibition on the y-axis. The individual data points shown for each cynomolgus macaque represent the mean ± standard deviation among two replicates on days 10, 14, 21, and 28 pc.

To understand what role, if any, neutralizing antibodies played among LASSARAB immunized NHPs in LASV infection, a microneutralization assay was performed. We determined that LASV-Josiah neutralizing antibodies were present in the sera of LASSARAB immunized NHPs but not CORAVAX™ immunized NHPs by day 10 pc (Fig. 6b). Neutralizing antibodies persisted in the sera of all LASSARAB immunized NHPs through day 28 pc (Fig. 6b), albeit levels varied. We calculated individual NHP reciprocal endpoint titers (EPT) and average titer ± standard deviation at days 10, 14, 21, and 28 (Fig. 6b). NEUT50 reciprocal EPT were 90, 30, and 10 (90 = NHP1 and NHP3; 30 = NHP2 and NHP6; and 10 = NHP4 and NHP5) at day 10 pc. At day 14 pc, NEUT50 reciprocal EPT were 270 (NHP3), 90 (NHP1, 2, 4, and 6), and 10 (NHP5). At days 21 and 28 pc, NEUT50 reciprocal EPT were 90, 30, and 10 (90 = NHP 1, 2, 3, 4; 30 = NHP6; and 10 = NHP5). The mean titers were 43 ± 37 on day 10 pc, 107 ± 86 on day 14 pc, and 67 ± 37 on days 21 and 28 pc. These data suggest that serum neutralizing antibody levels may peak between days 14 to 21 pc in LASSARAB immunized NHP.

Next, we compared individual LASSARAB immunized NHP neutralizing antibody responses by calculating NEUT50 reciprocal titers using a four-parameter non-linear regression analysis (Fig. 6c). NEUT50 reciprocal titers among all LASSARAB immunized NHP and timepoints ranged from 1 to 286 (Supplementary Table 1). The neutralizing-antibody activity was greatest at day 14 pc among NHP1, 2, 3, 5, and 6. NHP3 had the most potent LASV-neutralizing antibodies at days 10, 14, and 21. In contrast, NHP5 had the least potent antibodies across all timepoints pc. For NHP4, the most potent neutralizing-antibody activity was observed on days 21 through 28 pc.

Immunization with LASSARAB mitigates changes in hematology and blood chemistry

It is well established that LASV infection causes drastic changes to various cell populations and blood chemistry in both humans and NHPs42,43,44. While changes to blood cell populations were similar between LASSARAB and CORAVAX™ vaccinated NHPs at the beginning of the infection, these changes were mostly normalized in LASSARAB vaccinated NHPs starting around day 10 pc (Supplementary Fig. 2). Most notably in the LASSARAB group, platelets returned to baseline levels, and neutrophils, which typically expand and cause damage in LASV infection by releasing toxic effectors43,45, were maintained at consistently low levels throughout the course of the study (Supplementary Fig. 2).

In terms of blood chemistry, LASSARAB-immunized NHPs maintained normal levels of all analytes tested throughout the course of the challenge (Supplementary Fig. 3), unlike CORAVAX™-immunized NHPs, which had significantly increased levels of analytes, indicative of liver and kidney damage (ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, and BUN), as well as significant decreases in ALB, indicative of vascular leakage (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Acute pathology is limited by LASSARAB immunization

Significant LASV histologic findings in NHPs at necropsy are presented in Table 1. The primary histopathologic diagnoses observed in the NHPs include the following: meningoencephalitis, inflammation and vasculitis of the choroid plexus, inflammation in the heart, necrotizing hepatitis, multisystemic vasculitis with or without surrounding inflammation, interstitial pneumonia with alveolitis and vasculitis, and lymphoid hyperplasia in one or more lymph nodes and spleen. The most severe of these lesions, as indicated in Table 1, are restricted to the control NHPs. Severe lesions observed in multiple tissue types of the control NHP are shown in Fig. 7a–f. These lesions are severe, widespread, and typical of fatal Lassa fever in NHPs43. Interestingly, a proliferative and necrotizing arteritis was observed in 5/6 of vaccinated survivors, similar to what has been previously described (Fig. 7g–j)46. Importantly, the proliferative and necrotizing polyarteritis (polyarteritis nodosa) noted in 5/6 survivors is histologically distinct from the vasculitis and/or arteritis noted in all the control animals that succumbed during the acute phase of LASV infection. Figure 7g–j shows these proliferative and necrotizing polyarteritis lesions observed in multiple tissues of vaccinated survivors. These lesions were marked by the thickening of medium muscular arteries in numerous organ systems including the brain, meninges, lung, heart, liver, kidneys, uterus, testicles, and epididymis. This has been previously documented in LASV surviving macaques and guinea pigs46,47. These findings are similar to polyarteritis nodosa described in animals and humans.

a Liver. Multifocal necrosis and loss of hepatocytes (circled) that disrupt normal hepatic cord architecture were observed. b Brain. Within the neuropil, there is increased cellularity (circled), and the blood vessel (BV) wall is expanded by necrotic debris (arrow) and inflammatory cells. c Heart. The epicardium and myocardial interstitium is expanded by inflammatory cells (arrows) composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. Note the increased clear space between myocardiocytes (asterisks), indicating edema. The myocardiocytes appear normal. d Spleen. The arteries (A) are disrupted. The tunica intima, media, and adventitia are disrupted and expanded by inflammatory cells (arrows). These cells are primarily lymphocytes and neutrophils. e Lung. Interstitial pneumonia and most of the alveolar spaces (asterisk) are filled with edema, fibrin, inflammatory cells (arrow), and hemorrhage. There is vasculitis present. The blood vessel (BV) wall is ill-defined and expanded by edema, inflammation, and necrotic debris. f Kidney. Note the intact extremely thin tunica intima with endothelial cell nuclei present (arrows). Note the intact internal elastic lamina (squiggle arrow), the smooth muscle of the tunica media (TM), and few cells and abundant collagen fibers of the tunica adventitia (TA). g Testicle. Note the polyarteritis nodosa of the testicular arteries (A). The arteries have a nodular appearance, compress underlying testicle (arrows), and elevate the surface (arrowheads). h Testicle. Expansion of the tunica intima by infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils. The intact internal elastic lamina (squiggle arrow) is disrupted at the arrowhead. The tunica media contains necrotic debris (arrow), and the tunica adventitia is greatly expanded by inflammatory cells and clear space (edema). i Uterus. Note the polyarteritis nodosa of the uterine arteries (A) (circled). Note the tunica intima (TI) is expanded, proliferative, and infiltrated by macrophages, neutrophils, and necrotic debris (red arrow). j Uterus. The internal elastic lamina (squiggle arrow) remains intact in this section. The tunica adventitia (TA) is greatly expanded by inflammatory cells (black arrows).

To assess the potential presence of viral antigen in tissues at the study endpoint, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis. Figure 8a–d demonstrates the presence of LASV antigen at high levels in multiple tissues, including brain, liver, lung, and spleen in control NHPs. We mainly noted IHC positivity in lymphoid tissues (BALT and GALT and germinal center) and observed arterial smooth muscle cells within vasculitis lesions in multiple organ systems of LASSARAB-vaccinated NHPs (Fig. 8e–l). The strong positivity by IHC in the vaccinated survivors supported further investigation, thus we performed in-situ hybridization (ISH) using a probe targeting the L segment of LASV on selected tissues to determine if the viral RNA was detectable in addition to viral antigen in these tissues. Interestingly, a strong ISH signal was present in the tissues tested, including lung, spleen, lymph node, and brain (Fig. 8m–p). Positivity of IHC and ISH demonstrated presence of viral antigen and RNA in these tissues.

a Brain, choroid plexus, and third ventricle. Strong IHC positivity in choroid plexus cuboidal cells (arrow) and ependymal cells of the third ventricle (arrowhead). b Liver. Strong LASV IHC positivity in hepatocytes and endothelium of hepatic sinuses (arrows). c Lung. Strong LASV IHC positivity of endothelium of artery and interstitium. d Spleen. Strong LASV IHC positivity of endothelium of venous sinuses (arrow) of the red pulp. Additionally, there is positivity in the germinal centers of the white pulp (asterisk), likely FRCs or follicular dendritic cells FDCs. e Lung. Strong LASV IHC positivity in the germinal center of BALT. f Spleen. Strong LASV IHC positivity in the germinal centers of the white pulp. g Lung. Strong LASV IHC positivity in the smooth muscle of the tunica media of a muscular artery. h Kidney. Strong LASV IHC positivity in the smooth muscle of the tunica media of a muscular artery. i Small Intestine. Strong LASV IHC positivity in the germinal centers of GALT. j Inguinal Lymph Node. Strong LASV IHC positivity in the germinal centers of lymphoid follicles. k Testicle. LASV IHC positivity in the smooth muscle (arrow) of the tunica media (TM) of a muscular artery. Additionally, this artery displays proliferative and necrotizing arteritis. l Brain. There is strong LASV IHC positivity in the smooth muscle of the tunica media (arrows) of a meningeal muscular artery. m Lung. Strong LASV ISH positivity in the germinal center of BALT (arrow). n Spleen. Strong LASV ISH positivity in the germinal centers of the white pulp. o Inguinal Lymph Node. Strong LASV ISH positivity in the germinal centers of lymphoid follicles. p Brain. Strong LASV ISH positivity in the meningeal artery smooth muscle (arrows).

Discussion

Given the severity of Lassa fever (LF) and lack of preventative countermeasures against it, there is a great need to develop a safe and effective LASV vaccine. We showed previously that an inactivated RABV-based vaccine targeting LASV-GPC, LASSARAB, was protective in a guinea pig LF challenge model and induced strong humoral responses in nonhuman primates (NHPs) up to one-year pi28,34. This study aimed to determine the protective efficacy of LASSARAB in NHPs. We demonstrated that LASSARAB could protect against severe disease and death in a lethal NHP model of LF.

Neutralizing antibodies are known to protect NHPs from lethal LASV challenge when administered as a cocktail via intravenous infusion as late as day 8 pc12. In LASSARAB vaccinated NHPs, we did not detect neutralizing antibodies prior to day 10 pc. However, after detection at day 10 pc, the neutralizing antibody titers peaked between days 14 to 21 pc and persisted at varying levels through day 28 pc in all LASSARAB vaccinates. Based on these results, it appears that neutralizing antibodies are only produced as a result of LASV challenge, not vaccination with LASSARAB, and thus are not playing a main role in vaccine-mediated protection against LASV challenge.

All LASSARAB-immunized NHPs survived challenge, with only one NHP demonstrating minor outward clinical signs and four NHPs showing transient viremia. One of the main targets of LASV infection is the liver, as indicated by a dramatic increase in liver enzymes43,44. LASSARAB immunized NHPs all maintained normal blood chemistry levels compared to controls, indicating that these NHPs were protected from liver dysfunction. NHPs in the control group developed severe and widespread histological lesions consistent with fatal LF infection as previously described for the cynomolgus macaque model43. Despite the positive clinical outcome and lack of CBC and blood chemistry changes in the vaccinated NHPs, pathologic analysis revealed significant lesions in lymphoid tissue as well as smooth muscle layer of arteries in multiple organ systems that stained positive for LASV antigen. This resembles a systemic auto-immune vasculitis that has been previously described in NHPs and guinea pigs that survive LASV infection46,47. Polyarteritis is a form of systemic necrotizing vasculitis that typically affects medium-sized muscular arteries and can result in secondary tissue ischemia and organ failure. Cashman et al. proposed an immune-mediated response in surviving LASV-infected macaques as primary etiology in previous studies46. In this study, most survivors were found to have the same proliferative and necrotizing polyarteritis to some degree. In the surviving NHP, the arteritis affected primarily medium-sized muscular arteries. The disease process for LASV in NHPs is somewhat protracted compared to other hemorrhagic fever viruses in which NHPs become morbid and require euthanasia 5–7 days after exposure. This study’s endpoint was 28 days after virus exposure. It is unknown if the pathology that was observed in vaccinated survivors at day 28 would have resolved or become less prevalent if the study endpoint was longer. Additionally, the control NHPs had a more severe disease course compared to previous studies, potentially a result of their young age43,46. However, given the severity of the polyarteritis seen in the LASSARAB vaccinated NHPs, further studies with longer endpoints are required to determine if this pathology resolves over time or whether it can be avoided altogether with administration of LASSARAB to a more mature cohort of NHPs. Furthermore, studies to verify that this pathology was not caused by the vaccine itself are necessary to determine the mechanism of pathology.

Other vaccine platforms targeting LASV-GPC have also shown protection in lethal NHP challenge models. These include a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing LASV-GPC48, recombinant22 and modified49 VSVs expressing LASV-GPC, recombinant measles virus (MeV) expressing LASV-GPC and nucleoprotein (NP)15, attenuated Mopeia virus expressing LASV-GPC19, and a DNA vaccine of LASV-GPC14,23,24. Although not sterilizing, the protective efficacy of LASSARAB is comparable to many of these other vaccine platforms15,22,48,49, with 100% of LASSARAB-vaccinated NHPs surviving challenge and showing minimal clinical signs. While these other platforms are protective, the inactivated RABV platform has some advantages over these platforms. As mentioned above, the rabies vaccine has been in use for decades and is safe to administer to a variety of patient populations, including both immunocompromised and pregnant patients30. The rabies vaccine has been shown to elicit long-term immunity in humans50 and appears to confer this longevity to foreign antigens34,51,52, although further studies are required to determine the full extent of the durability of immune responses against foreign antigens.

The areas in which LASV is endemic have warm climates and limited access to cold-chain storage. While most of the other vaccine platforms mentioned above require cold-chain storage to remain stable over time, the inactivated RABV platform has been shown to remain stable over a variety of temperatures for extended periods of time31. The areas where LASV is endemic are also endemic to RABV, and thus LASSARAB can provide protection against both viruses. Importantly given the presence of RABV in these areas, we have shown that vector pre-immunity does not impact the ability of this platform to elicit immune responses against a foreign antigen52, although this will need to be confirmed with LASSARAB. Finally, the rabies vaccine is already commercially available, which means that infrastructure already exists for large-scale production of medical grade material53.

Our previous study demonstrated that in mice, LASSARAB can protect through non-neutralizing antibodies28. We confirmed that pre-challenge, NHPs immunized with LASSARAB also develop non-neutralizing antibodies with Fcγ-receptor mediated functions, but not neutralizing antibodies. The dispensability of neutralizing antibodies for protection against LASV is in line with other vaccine strategies17,22,32 and is likely a result of the LASV glycoprotein glycan shield blocking antibodies from binding to neutralizing epitopes33. While more studies, especially experiments on cellular immunity, are required to establish the mechanism of protection for LASSARAB, non-neutralizing antibodies acting as a potential mechanism of protection would be in contrast to other vaccine strategies targeting GPC, in which vaccine-mediated cellular immunity was protective17,32. Additionally, a gamma-irradiated whole LASV virion vaccine elicited strong antibody responses, but could not protect NHPs from LASV challenge54. These disparities in protective mechanism are likely attributed to the type of platform used, given that our platform is an inactivated RABV, while the two that require cellular immunity are live viral vectors (Vaccinia and Mopeia viruses)17,32, and the non-protective vaccine was inactivated LASV virions54. Overall, this suggests that there is not one specific mechanism of protection for LASV vaccines, and the mechanism will have to be determined on a case-by-case basis.

We are currently setting up a phase I clinical trial of LASSARAB in the US. Nevertheless, other studies should be performed to support the use of LASSARAB in the clinic. An ideal vaccine candidate should be cross-protective against a variety of LASV strains. Three LASV vaccine candidates, the MeV-, VSV-, and modified VSV-based vaccines, have demonstrated cross-protection against heterologous strains of LASV in NHPs49,55,56. These vaccines target LASV-GPC, demonstrating that immune responses against LASV-GPC are protective against various strains of LASV. LASSARAB also targets LASV-GPC, indicating that this vaccine has the potential for cross-protection; however, further studies are required to investigate this. In addition to a vaccine that can protect against various strains of LASV, another focus has been the development of vaccines that only require a single dose and provide rapid protection. All live viral-vectored LASV vaccines showed protection in NHPs after a single dose15,19,22,48,49. Furthermore, a VSV-based LASV vaccine was able to protect NHPs that were challenged either 3- or 7-days pi56. Given the advantage of a single-dose vaccine regimen, additional studies should be conducted to determine whether LASSARAB can protect NHPs after a single-dose immunization and how rapidly LASSARAB confers protection pi.

As a result of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, there was limited availability of NHPs at the time of this study. The NHPs we acquired for this study were young and small in size, which limited the amount of blood we were able to collect. Thus, we were unable to perform assays looking at cellular immunity elicited by LASSARAB or whether these responses play a role in LASSARAB-mediated protection. We previously showed that Fcγ-receptor knockout mice immunized with LASSARAB were not protected from challenge with a VSV-based LASV surrogate challenge virus28. While this indicates that the strong non-neutralizing antibody responses may play a role in the protection conferred by LASSARAB, we cannot exclude the possibility that neutralizing antibodies, and T cells, play a role in protection, especially given that these mechanistic studies have not yet been repeated in a challenge model with wildtype LASV. Future studies must determine whether LASSARAB induces a cellular response and what role (if any) these responses play in vaccine-mediated protection. LASSARAB is administered in a prime/boost immunization regimen, which is a significant limitation of this platform compared to other platforms that have shown protection after a single dose15,19,22,48,49. As mentioned above, studies testing the protective efficacy of LASSARAB after immunization with a single dose are required to determine the extent of this limitation. It should also be noted that the vaccine did not prevent the development of systemic, immune-mediated, proliferative, and necrotizing vasculitis in NHPs surviving to day 28 pc. An additional study with a longer endpoint may be warranted to observe whether these pathologic lesions will resolve over time.

Materials and methods

Animal use statement

All procedures involving mice or NHPs, including vaccinations, blood collections, physical examinations, and euthanasia were conducted in accordance with facility specific IACUC- approved protocol in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, PHS Policy, and other Federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The facilities where this research was conducted is accredited by the AAALAC International and adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 2011. All procedures conducted on mice at Thomas Jefferson University (TJU) were performed while mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane/O2 gas. Mice were humanely euthanized at the completion of the study by exsanguination under 3% isoflurane/O2 gas. Death was confirmed by cervical dislocation in accordance with TJU IACUC approved mouse protocols. Blood collection and vaccination of NHPs at Alphagenesis (AGI) were conducted on anesthetized NHPs following AGI IACUC approved protocols. Briefly, NHP were injected IM with 10–25 mg/kg of ketamine before procedures. All vaccinations were administered in the opposite hind limb used for sedation. Study personnel at United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) were blinded to group assignment, thus eliminating bias for clinical signs and euthanasia assessments. Procedures at USAMRIID causing momentary discomfort were conducted on anesthetized NHP, as mandated by the IACUC-approved protocols and in accordance with USAMRIID standard Operating procedures (SOPs). Briefly, NHP were held off feed the evening prior to the procedures, then on the morning of the procedure, were administered an IM anesthetizing dose of Ketamine-HCl (8–10 mg/kg) prior to procedures. After the procedures were completed, NHP were carefully monitored until recovered. NHP were humanely euthanized either when IACUC-approved clinical criteria were met, or at the completion of the study in accordance with USAMRIID internal SOPs. Briefly, NHP were deeply anesthetized using an intramuscular dose of 15 mg/kg or greater of Ketamine-HCl prior to intravenous administration of pentobarbital solution as a concentration of 150 mg/kg. Death was confirmed by absence of heartbeat for at least 10 min prior to conducting necropsy, in accordance with USAMRIID SOPs.

Study design

The goal of this study was to determine the protective efficacy of a RABV-based LASV vaccine, LASSARAB28. Mauritius cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) ages 10 months to 2.5 years were used for this study. A total of twelve NHPs were pre-screened to assess prior immunity to LASV-GPC and RABV-G. No NHPs had prior immunity to LASV-GPC, but three were previously immunized against RABV. The three RABV-positive NHPs were placed into the control group (NHPs 7, 8 and 9). The remaining nine NHPs were randomly assigned with three additional NHPs placed into the control group (3 RABV-positive and 3 RABV-negative) and six NHPs placed into the experimental group. Each NHP was vaccinated at Alphagenesis (AGI, Yemassee, South Carolina, USA) by intramuscular (IM) administration of 150 μg LASSARAB or 150 µg CORAVAX™ and both vaccines were adjuvanted with 15 µg of monophosphoryl lipid A, 3D(6 A)-PHAD, in 2% stable emulsion (PHAD-SE). LASSARAB and the negative control vaccine CORAVAX™35 were prepared by growing the viruses in bioreactors, concentrating the viral supernatants and inactivating the viruses with β-propiolactone. NHPs were immunized on days 0 and 28, and blood was taken on days −14, 0, 14, 28, 42, and 56 for immunological analysis. NHPs were shipped to the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID, Fort Detrick, Maryland, USA) and moved into the ABSL-4 containment laboratory on day 63 in preparation for the challenge study. Study team members involved with daily observations, physical exams, and data acquisition were blinded to group assignment to eliminate bias. On day 70, baseline weights and rectal temperatures were obtained, and blood samples were collected to establish baseline blood counts and blood chemistry levels. Each NHP was then administered a target dose of 1000 PFU of LASV via IM route. NHPs were evaluated daily for changes in clinical signs. Rectal temperatures and weights were obtained, and physical exams performed on all scheduled blood collection days (days 0, 3, 6, 10, 14, 21, and 28 pc), as well as on the day of euthanasia. Animals surviving to day 98 (day 28 pc) or deemed moribund based on clinical signs and euthanasia criteria were euthanized. Euthanasia determinations were made based on criteria in the IACUC-approved protocol. Each NHP received a clinical score at each observation as follows: 0 = animal is alert, responsive, and engaging in normal species-specific behavior; 1 = animal is exhibiting slightly diminished general activity, is subdued, but responding normally to external stimuli; 2 = animal is withdrawn, may have head down, upright fetal posture, hunched, and exhibiting reduced response to external stimuli; 3 = animal is prostrate but able to rise if stimulated, or is exhibiting dramatically reduced response to external stimuli; or 4 = animal is persistently prostrate, is severely or completely unresponsive. A clinical score of 4 was considered criteria for immediate humane euthanasia. At necropsy, tissues were collected, preserved, processed, and examined microscopically for each NHP.

Cells

BEAS-2B (ATCC® CRL-9609™), 293 T (available from the Schnell laboratory), Vero CCL81 (ATCC® CCL81™), Vero E6 (ATCC® CRL-1586) and Vero 76 (ATCC® CRL-1587) cells were cultured with DMEM (Corning®) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta-Biological®) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (P/S) (Gibco®). Mouse neuroblastoma (NA) cells (available upon request) were cultured with RPMI (Corning®) containing 5% FBS and 1% P/S. Jurkat cells with the Fcγ receptor IIIa and nanoluciferase reporter gene (Promega) were cultured with RPMI (Corning®) containing 10% FBS, 100 µg/mL hygromycin, and 500 µg/mL Geneticin. All cells were stored in incubators with 5% CO2 at 37 °C or 34 °C for virus infected cells.

Viruses

RABV strain CVS-11 (GenBank: GQ918139.1) was produced on NA cells in the Schnell laboratory and is available upon request57,58. The LASV Josiah stock used for this study was acquired from the CDC in 1982 (CDC #800789) and propagated by USAMRIID. It was originally isolated during an outbreak in 1976 from the serum of a severely ill patient in Sierra Leone, Africa.

Immunization of mice for adjuvant comparison

Groups of 5, female C57BL/6 mice (Charles River) were immunized IM with 10 µg of LASSARAB or FILORAB1 (Rabies-based Ebola virus vaccine). The vaccines were adjuvanted with either glucopyranosyl lipid A in a squalene-in-oil emulsion (GLA-SE) or PHAD-SE at a dose of 5 µg GLA/PHAD and 2% SE. Each dose was administered as 50 µL in each hind leg (for a total of 100 µL). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and immunized on days 0 and 21. Serum was collected via retro-orbital bleeds on days 0 and 21, and the final bleed was on day 28.

ELISA antigen production

Both RABV-G and LASV-GPC were prepared as stripped antigens as previously described28,34,59. In brief, BEAS-2B cells were infected with either recombinant VSV (rVSV)-ΔG-LASV-GPC or rVSV-ΔG-RABV-G-GFP in Opti-Pro SFM (Gibco). Viral supernatants were then concentrated, and sucrose purified, and glycoproteins were stripped from the surface of their virions using 2% OGP (Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside) detergent.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Mouse and NHP sera were analyzed by ELISA to look for anti-LASV-GPC or RABV-G immunoglobulin (Ig) G, as described elsewhere28,34. Briefly, plates were coated overnight with 50 ng/well of each antigen, then the following day blocked for 2 h and incubated with mouse or NHP serum samples overnight at 4 °C. Next, plates were incubated with the respective secondary antibody at 25 ng/mL for 2 h, and then o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride substrate (Sigma–Aldrich) was added to each well for development.

Plates were read at the absorbance wavelengths of 630 nm and 490 nm, and the delta value was calculated by subtracting the 630 nm reading from the 490 nm reading. The delta values were used for analysis in GraphPad Prism 9 software. Both half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) serum or antibody titer and endpoint cutoff values were calculated as previously described34. Any samples without a proper curve were considered to have no detectable antibodies, given that a full curve is required for calculating an accurate EC50 value.

Rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT)

Rabies virus neutralization was measured using the RFFIT assay as previously described60. Briefly, heat-inactivated NHP sera was incubated with a previously determined amount of RABV strain CVS-11 that produces infection of 90% of the cells for 1 h, overlaid onto NA cells for 2 h, and then aspirated and replaced with fresh medium. After 24 h total infection, cells were fixed and stained for RABV-N. 50% endpoint titers were determined using the Reed-Muench method and then, through comparison to the WHO standard, converted to international units (IU) per mL.

Production of pseudovirus

VSV pseudovirus (ppVSV) was produced as previously described28. In brief, 293 T cells were transfected with a pCAGGS plasmid containing LASV-GPC with X-tremeGENE9 (Sigma–Aldrich). After incubation overnight at 37 °C, cells were infected with ppVSV-NL-GFP at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. Infected cells were incubated at 34 °C until cells were 60–80% GFP positive, and then viral supernatant (termed ppVSV-ΔG-LASV-GPC-NL-GFP) was collected.

LASV pseudotype virus neutralization assay (VNA)

VNAs using the pseudovirus ppVSV-ΔG-LASV-GPC-NL-GFP was performed as described previously28. In brief, heat-inactivated NHP serum or positive control monoclonal antibody 37.7H39 (30 µg/mL starting dilution; generous gift of Dr. Robert Garry, Tulane University) was mixed with ppVSV-ΔG-LASV-GPC-NL-GFP for 2 h and then overlaid onto Vero CCL81 cells and incubated overnight. The following day, cells were lysed and treated with NanoLuc substrate (Promega) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Luminescence was read using the Omega Luminometer, with relative luminescence units (RLU) being normalized to the signal in wells without serum/antibody (100% infectivity). Any signal above 100% was reported as 100%.

LASV microneutralization assay

To determine the ability of serum to neutralize LASV Josiah host cell infection, we used a fluorescent microneutralization assay. The assay was performed in duplicate using 8 three-fold serial dilutions of sera starting at a 1:10 dilution in cell culture media containing 2% heat-inactivated FBS (MEM + 2% FBS) (Corning 10-010; GE Healthcare Hyclone). For negative and positive controls, we used serum from naïve and LASV convalescent NHPs. One day prior to starting the assay, we seeded Vero E6 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) at 2.5E4 cells/well in 96-well black clear-bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One). The following day, we mixed diluted serum with LASV Josiah, incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and added the virus/serum mixture to the ATCC Vero E6 cells at a target MOI of 0.5. Unbound virus was removed after the 1-hour incubation at 37 °C. Cells were washed once in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline without calcium and magnesium (DPBS, MilliporeSigma), and cell culture media (MEM + 5% FBS + 1% P/S (Gibco Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140122)) was added. Cells were fixed 48 h after infection, washed 3 times with DPBS (MilliporeSigma), permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 (Bio-Rad), and blocked with Cell Staining Buffer (Biolegend). The number of infected cells was determined using LASV-GP-specific mouse monoclonal antibody (Clone L52-161-6), goat anti-mouse IgG (H&L) Alexa Fluor 568 F(ab’)2 fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (Invitrogen Thermo Fisher Scientific, A11019), and NucBlue Live ReadyProbes Reagent (Hoechst 33342) (Invitrogen Thermo Fisher Scientific). The percentage of infected cells was determined with the Cytation 5 (Agilent BioTek), using Gen 5.11 software. We determined the neutralization percentage for each serum sample at each dilution relative to untreated, virus-only control wells.

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) assay

Fc-mediated antibody effector functions were measured using an ADCC assay adapted from previously described methods61. Vero CCL81 cells were seeded in white, 96-well flat-bottomed plates at a density of 3E4 cells per well in the inner 60 wells of the plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The following day, cells were infected with rVSV-ΔG-LASV-GPC at an MOI of 0.1 and incubated for 16 h at 34 °C. NHP serum samples were heat-inactivated for 30 min at 56 °C. Serum was then serially diluted in a 2-fold dilution series at a starting dilution of 1:3.3 (for a final concentration of 1:10 once added to assay plates) in 96-well round-bottomed plates in assay buffer (RPMI 1640, 4% Low IgG Serum). The medium from the infected Vero CCL81 cells was removed and replaced by 25 µL of assay buffer and 25 µL of diluted NHP sera and incubated for 30 min at 34 °C. Next, Jurkat cells expressing human Fcγ receptor IIIa effector cells with an NFAT controlled nano-luciferase reporter gene (Promega) were added to the infected Vero CCL81 cells/sera plate in 25 µL at a 5:1 ratio of effector to target cells and incubated for 6 h at 34 °C. Next, plates were incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and then 75 µL of Bio-Glo Luciferase assay reagent (Promega) was added to each well in addition to 3 wells without cells or sera. After at least 5 min, plates were analyzed for luminescence on the Omega Luminometer. Fold induction was calculated using relative light units (RLU) with the following formula: (RLU induced – RLU background) / (RLU uninduced – RLU background), with RLU induced being the NHP serum samples, RLU background being the wells without cells or sera, and RLU uninduced being the cells without sera. For each dilution, mean values and standard errors of the means (SEM) were graphed using a nonlinear regression curve on GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Blood chemistries

The General Chemistry 13 panel, which includes analytes alanine transaminase (ALT), serum albumin (ALB), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), amylase (AMY), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), calcium (CA), creatinine (CRE), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), glucose (GLU), total bilirubin (TBIL), and total protein (TP) was run on Piccolo® blood chemistry analyzers (Abaxis).

Hematology

A VETSCAN® HM5 hematology analyzer was used to obtain complete blood counts throughout the study. The analytes included were white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils (NEU), eosinophils (EOS), basophils (BAS), lymphocytes (LYM), monocytes (MON), red blood cells (RBC), hemoglobin (HGB), hematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), red cell distribution width (RDW), platelet counts (PLT), mean platelet volume (MPV), plateletcrit (PCT), and platelet distribution width (PDW). Blood chemistries and hematology analyses were obtained contemporaneously during the in-life phase.

Viremia

Serum viremia was measured by both standard plaque assay (which can enumerate replicating virus in samples) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR, which can enumerate viral RNA present without regard to replication status). The standard plaque titration assay was performed on Vero 76 cells in accordance with (IAW) USAMRIID standard operating procedure (SOP) for LASV26. Briefly, required dilutions of each specimen were added to plates containing Vero 76 cells on assay day 0, in duplicate. The cells were stained with neutral red on assay day 4, and resulting viral plaque counts were obtained on assay day 5. Titers were calculated for each specimen based on all dilution series with countable plaques between 10 and 150. PCR was performed on Trizol-LS-inactivated plasma by first extracting RNA using a QIAamp® Viral RNA Mini Kit. The quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) reaction used the Invitrogen™ SuperScript® II One-Step RT-PCR System with additional magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) added to a final concentration of 3.0 mM. The sequence of the primer and probes for the LASV target gene are shown below in Table 2.

Specimens were run in triplicate using an Applied Biosystems® 7500 Fast Dx instrument. The resulting data were expressed as cycle threshold (CT), which shows the number of PCR replication cycles in each sample that is required for the signal to exceed background levels. Limit of detection for this assay was determined to be 42 CT.

Histopathology

In preparation for histology analysis, tissue samples collected at necropsy were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 28 days. Tissues were processed in a Tissue-tek VIP-6 vacuum infiltration processor (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA) followed by paraffin embedding with a Tissue-Tek model TEC (Sakura). Sections were cut on a Leica model 2245 microtome at 5 µm, deparaffinized, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard procedure.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed in accordance with USAMRIID SOPs and using the Dako Envision system (Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions, Carpinteria, CA, USA). LASV-infected and uninfected macaque tissues from historical studies were used as IHC positive and negative controls, respectively. Briefly, after deparaffinization, peroxidase blocking, and antigen retrieval, sections were covered with mouse anti-Lassa virus monoclonal antibody (clone 52-2074-7 A, USAMRIID) at a dilution of 1:8000 and incubated at room temperature for 40 min. They were rinsed, and the peroxidase-labeled polymer (secondary antibody) was applied for 30 min. Slides were rinsed, and a brown chromogenic substrate 3,3’ Diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (Dako Agilent Pathology Solutions) was applied for 8 min. The substrate-chromogen solution was rinsed off the slides, and slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and rinsed. The sections were dehydrated, cleared with xyless (Val Tech Diagnostics, Brackenridge, PA, USA), and then coverslipped. The following severity scale was used for reporting: 0 = Negative:- no cells in section are positive; 1 = < 10% of cells in section are positive (minimal); 2 = 11–25% of cells in section are positive (mild); 3 = 26–50% of cells in section are positive (moderate); 4 = 50–75% of cells in section are positive (marked); 5 = > 75% of cells in section are positive (severe).

In-situ hybridization

In-Situ Hybridization (ISH) was performed on select animals and select tissues. LASV-infected and uninfected macaque tissues from historic studies were used as ISH positive and negative controls, respectively. RNA ISH was performed using RNAscope® 2.5 HD RED kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA). Briefly, 20 ZZ probes set targeting to 466–1433 polymerase (L protein) of Lassa virus genome with GenBank accession number KM821901.1 were synthesized. After deparaffinization and peroxidase blocking, the sections were heated in antigen retrieval buffer and then digested by proteinase. The sections were covered with ISH probes and incubated at 40 °C in hybridization oven for 2 h. After rinsing, ISH signal was amplified using kit-provided Pre-amplifier and Amplifier conjugated to alkaline phosphatase and incubated with a Fast Red substrate solution for 8 min at room temperature. Sections were then stained with hematoxylin, air-dried, and cover slipped.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9 software was used for all statistical analysis. For ELISA and RFFIT assays, log transformed data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney test at each timepoint. Statistical differences in survival curves were determined using the log-rank Mantel-Cox test. Viremia, cell population, hematology parameters, and blood chemistry data were analyzed using multiple unpaired t-tests assuming a Gaussian distribution.

Disclaimer

Research was conducted under an IACUC approved protocol in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, PHS Policy, and other Federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The facilities where this research was conducted is accredited by the AAALAC International and adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 2011. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References

Ogbu, O., Ajuluchukwu, E. & Uneke, C. J. Lassa fever in West African sub-region: an overview. J. Vector Borne Dis. 44, 1–11 (2007).

McCormick, J. B., Webb, P. A., Krebs, J. W., Johnson, K. M. & Smith, E. S. A prospective study of the epidemiology and ecology of Lassa fever. J. Infect. Dis. 155, 437–444, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/155.3.437 (1987).

Keenlyside, R. A. et al. Case-control study of Mastomys natalensis and humans in Lassa virus-infected households in Sierra Leone. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 32, 829–837, https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.829 (1983).

Kafetzopoulou, L. E. et al. Metagenomic sequencing at the epicenter of the Nigeria 2018 Lassa fever outbreak. Science 363, 74–77, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau9343 (2019).

Fisher-Hoch, S. P. et al. Review of cases of nosocomial Lassa fever in Nigeria: the high price of poor medical practice. Bmj 311, 857–859, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7009.857 (1995).

Hallam, H. J. et al. Baseline mapping of Lassa fever virology, epidemiology and vaccine research and development. NPJ Vaccines 3, 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-018-0049-5 (2018).

Shaffer, J. G. et al. Lassa fever in post-conflict sierra leone. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2748, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002748 (2014).

McCormick, J. B. & Fisher-Hoch, S. P. in Arenaviruses I: The Epidemiology, Molecular and Cell Biology of Arenaviruses (ed Michael B. A. Oldstone) 75–109 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2002).

Cummins, D. et al. Acute sensorineural deafness in Lassa fever. Jama 264, 2093–2096 (1990).

Nunberg, J. H. & York, J. The curious case of arenavirus entry, and its inhibition. Viruses 4, 83–101, https://doi.org/10.3390/v4010083 (2012).

Cross, R. W. et al. Treatment of Lassa virus infection in outbred guinea pigs with first-in-class human monoclonal antibodies. Antivir. Res. 133, 218–222, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.08.012 (2016).

Mire, C. E. et al. Human-monoclonal-antibody therapy protects nonhuman primates against advanced Lassa fever. Nat. Med. 23, 1146–1149, https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4396 (2017).

Safronetz, D. et al. A recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-based Lassa fever vaccine protects guinea pigs and macaques against challenge with geographically and genetically distinct Lassa viruses. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003736, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003736 (2015).

Cashman, K. A. et al. A DNA vaccine delivered by dermal electroporation fully protects cynomolgus macaques against Lassa fever. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 13, 2902–2911, https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2017.1356500 (2017).

Mateo, M. et al. Vaccines inducing immunity to Lassa virus glycoprotein and nucleoprotein protect macaques after a single shot. Sci. Transl. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw3163 (2019).

Pushko, P., Geisbert, J., Parker, M., Jahrling, P. & Smith, J. Individual and bivalent vaccines based on alphavirus replicons protect guinea pigs against infection with Lassa and Ebola viruses. J. Virol. 75, 11677–11685, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.75.23.11677-11685.2001 (2001).

Fisher-Hoch, S. P., Hutwagner, L., Brown, B. & McCormick, J. B. Effective vaccine for lassa fever. J. Virol. 74, 6777–6783, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.74.15.6777-6783.2000 (2000).

Lukashevich, I. S. et al. A live attenuated vaccine for Lassa fever made by reassortment of Lassa and Mopeia viruses. J. Virol. 79, 13934–13942, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.79.22.13934-13942.2005 (2005).

Carnec, X. et al. A Vaccine platform against arenaviruses based on a recombinant hyperattenuated mopeia virus expressing heterologous glycoproteins. J. Virol. 92 https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.02230-17 (2018).

Bredenbeek, P. J. et al. A recombinant Yellow Fever 17D vaccine expressing Lassa virus glycoproteins. Virology 345, 299–304, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.001 (2006).

Fischer, R. J. et al. ChAdOx1-vectored Lassa fever vaccine elicits a robust cellular and humoral immune response and protects guinea pigs against lethal Lassa virus challenge. NPJ Vaccines 6, 32, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-021-00291-x (2021).

Geisbert, T. W. et al. Development of a new vaccine for the prevention of Lassa fever. PLoS Med. 2, e183, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020183 (2005).

Jiang, J. et al. Multivalent DNA vaccines as a strategy to combat multiple concurrent epidemics: mosquito-borne and hemorrhagic fever viruses. Viruses 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/v13030382 (2021).

Jiang, J. et al. Immunogenicity of a protective intradermal DNA vaccine against Lassa virus in cynomolgus macaques. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 15, 2066–2074, https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1616499 (2019).

Cashman, K. A. et al. DNA vaccines elicit durable protective immunity against individual or simultaneous infections with Lassa and Ebola viruses in guinea pigs. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 13, 3010–3019, https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2017.1382780 (2017).

Cashman, K. A. et al. Enhanced efficacy of a codon-optimized DNA vaccine encoding the glycoprotein precursor gene of Lassa Virus in a Guinea Pig Disease Model when delivered by dermal electroporation. Vaccines 1, 262–277, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines1030262 (2013).

Scher, G. & Schnell, M. J. Rhabdoviruses as vectors for vaccines and therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Virol. 44, 169–182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2020.09.003 (2020).

Abreu-Mota, T. et al. Non-neutralizing antibodies elicited by recombinant Lassa-Rabies vaccine are critical for protection against Lassa fever. Nat. Commun. 9, 4223, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06741-w (2018).

India, C. T. R. Intramuscular inactiavted rabies vector platform Corona virus vaccine (rDNA-BBV151), http://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/showallp.php?mid1=58694&EncHid=&userName=035425 (2021).

Giesen, A., Gniel, D. & Malerczyk, C. 30 Years of rabies vaccination with Rabipur: a summary of clinical data and global experience. Expert Rev. Vaccines 14, 351–367, https://doi.org/10.1586/14760584.2015.1011134 (2015).

Kurup, D. et al. Inactivated rabies virus-based ebola vaccine preserved by vaporization is heat-stable and immunogenic against ebola and protects against rabies challenge. J. Infect. Dis. 220, 1521–1528, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz332 (2019).

Carrion, R. Jr. et al. A ML29 reassortant virus protects guinea pigs against a distantly related Nigerian strain of Lassa virus and can provide sterilizing immunity. Vaccine 25, 4093–4102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.038 (2007).

Sommerstein, R. et al. Arenavirus glycan shield promotes neutralizing antibody evasion and protracted infection. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005276, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1005276 (2015).

Kurup, D. et al. Tetravalent rabies-vectored filovirus and Lassa Fever vaccine induces long-term immunity in nonhuman primates. J. Infect. Dis. 224, 995–1004, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiab014 (2021).

Kurup, D., Wirblich, C., Ramage, H. & Schnell, M. J. Rabies virus-based COVID-19 vaccine CORAVAX™ induces high levels of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. NPJ Vaccines 5, 98, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-020-00248-6 (2020).

Johnson, R. F. et al. An inactivated rabies virus-based Ebola vaccine, FILORAB1, adjuvanted with glucopyranosyl lipid A in stable emulsion confers complete protection in nonhuman primate challenge models. J. Infect. Dis. 214, S342–s354, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiw231 (2016).

Behzad, H. et al. GLA-SE, a synthetic toll-like receptor 4 agonist, enhances T-cell responses to influenza vaccine in older adults. J. Infect. Dis. 205, 466–473, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jir769 (2012).

Hernandez, A. et al. Phosphorylated hexa-acyl disaccharides augment host resistance against common nosocomial pathogens. Crit. Care Med. 47, e930–e938, https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000003967 (2019).

Robinson, J. E. et al. Most neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies target novel epitopes requiring both Lassa virus glycoprotein subunits. Nat. Commun. 7, 11544, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11544 (2016).

Johnson, N., Cunningham, A. F. & Fooks, A. R. The immune response to rabies virus infection and vaccination. Vaccine 28, 3896–3901, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.039 (2010).

Jahrling, P. B. et al. Lassa virus infection of rhesus monkeys: pathogenesis and treatment with ribavirin. J. Infect. Dis. 141, 580–589, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/141.5.580 (1980).

Johnson, K. M. et al. Clinical virology of Lassa fever in hospitalized patients. J. Infect. Dis. 155, 456–464, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/155.3.456 (1987).

Hensley, L. E. et al. Pathogenesis of Lassa fever in cynomolgus macaques. Virol. J. 8, 205, https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422x-8-205 (2011).

Yun, N. E. & Walker, D. H. Pathogenesis of Lassa fever. Viruses 4, 2031–2048, https://doi.org/10.3390/v4102031 (2012).

Fisher-Hoch, S. P. et al. Physiological and immunologic disturbances associated with shock in a primate model of Lassa fever. J. Infect. Dis. 155, 465–474, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/155.3.465 (1987).

Cashman, K. A. et al. Immune-mediated systemic vasculitis as the proposed cause of sudden-onset sensorineural hearing loss following Lassa Virus exposure in cynomolgus macaques. mBio 9 https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01896-18 (2018).

Liu, D. X. et al. Persistence of Lassa Virus associated with severe systemic arteritis in convalescing guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus). J. Infect. Dis. 219, 1818–1822, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiy641 (2019).

Fisher-Hoch, S. P. et al. Protection of rhesus monkeys from fatal Lassa fever by vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus containing the Lassa virus glycoprotein gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 317–321, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.86.1.317 (1989).

Cross, R. W. et al. Quadrivalent VesiculoVax vaccine protects nonhuman primates from viral-induced hemorrhagic fever and death. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 539–551, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci131958 (2020).

Mansfield, K. L. et al. Rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis elicits long-lasting immunity in humans. Vaccine 34, 5959–5967, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.09.058 (2016).

Yankowski, C., Kurup, D., Wirblich, C. & Schnell, M. J. Effects of adjuvants in a rabies-vectored Ebola virus vaccine on protection from surrogate challenge. NPJ Vaccines 8, 10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-023-00615-z (2023).

Yankowski, C., Wirblich, C., Kurup, D. & Schnell, M. J. Inactivated rabies-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine provides long-term immune response unaffected by vector immunity. NPJ Vaccines 7, 110, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-022-00532-7 (2022).

Rupprecht, C. E., Nagarajan, T. & Ertl, H. Current status and development of vaccines and other biologics for human rabies prevention. Expert Rev. Vaccines 15, 731–749, https://doi.org/10.1586/14760584.2016.1140040 (2016).

McCormick, J. B., Mitchell, S. W., Kiley, M. P., Ruo, S. & Fisher-Hoch, S. P. Inactivated Lassa virus elicits a non protective immune response in rhesus monkeys. J. Med. Virol. 37, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.1890370102 (1992).

Mateo, M. et al. A single-shot Lassa vaccine induces long-term immunity and protects cynomolgus monkeys against heterologous strains. Sci. Transl. Med. 13 https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abf6348 (2021).

Cross, R. W. et al. A recombinant VSV-vectored vaccine rapidly protects nonhuman primates against heterologous lethal Lassa fever. Cell Rep. 40, 111094, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111094 (2022).

Wunner, W. H., Dietzschold, B., Smith, C. L., Lafon, M. & Golub, E. Antigenic variants of CVS rabies virus with altered glycosylation sites. Virology 140, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6822(85)90440-4 (1985).

Wiktor, T. J. & Koprowski, H. Antigenic variants of rabies virus. J. Exp. Med. 152, 99–112, https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.152.1.99 (1980).

Blaney, J. E. et al. Antibody quality and protection from lethal Ebola virus challenge in nonhuman primates immunized with rabies virus based bivalent vaccine. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003389, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003389 (2013).

Smith, J. S., Yager, P. A. & Baer, G. M. A rapid reproducible test for determining rabies neutralizing antibody. Bull. World Health Organ 48, 535–541 (1973).

Kurup, D. et al. Measles-based Zika vaccine induces long-term immunity and requires NS1 antibodies to protect the female reproductive tract. NPJ Vaccines 7, 43, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-022-00464-2 (2022).

National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th edn, (The National Academies Press, 2011).

Acknowledgements

K.C. would like to acknowledge husbandry personnel in the Veterinary Medicine Division at USAMRIID for excellent advice and daily care for the NHP assigned to this study. K.C. would also like to acknowledge the careful and detailed work of the USAMRIID pathology Division for the preparation of the tissue sections and slides for analysis. The research was conducted under an IACUC-approved protocol in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, PHS Policy, and other Federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The facilities where this research was conducted are accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International and adhere to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 201162. The authors would like to acknowledge Alphagenesis (Yemassee, South Carolina, USA) for immunizing and bleeding the NHPs pre-challenge. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge IDT Biologika (Dessau-Rosslau, Germany) for producing the LASSARAB vaccine lots used in this study and Bharat Biotech (Telangana, India) for producing the CORAVAX™ vaccine lots used in this study. Funding: National Institutes of Health Contract HHSN272201700082C (M.J.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.J.S. Methodology: M.J.S., K.C., G.S. Investigation: G.S., C.Y., K.C. Visualization: N/A. Funding acquisition: M.J.S. Animal study performance: K.C., E.W., N.J., J.W., J.S., G.L., S.V. Postlife analysis: K.C., E.W., N.J., J.W., N.T., X.Z. Project administration: M.J.S., D.K. Supervision: M.J.S. Writing—original draft: G.S. and K.C. Writing—review & editing: G.S., M.J.S., K.C.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Scher, G., Yankowski, C., Kurup, D. et al. Inactivated rabies-based Lassa fever virus vaccine candidate LASSARAB protects nonhuman primates from lethal disease. npj Vaccines 9, 143 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00930-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-024-00930-z

This article is cited by

-

Structure-guided design of a prefusion GPC trimer induces neutralizing responses against LASV

npj Vaccines (2025)

-

Immunogenicity and safety of a rabies-based highly pathogenic influenza A virus H5 vaccine in cattle

npj Vaccines (2025)

-

Current perspectives on vaccines and therapeutics for Lassa Fever

Virology Journal (2024)