Abstract

Macrophages present a spectrum of phenotypes that mediate both the pathogenesis and resolution of atherosclerotic lesions. Inflammatory macrophage phenotypes are pro-atherogenic, but the stimulatory factors that promote these phenotypes remain incompletely defined. Here we demonstrate that microbial small RNAs (msRNA) are enriched on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and drive pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization and cytokine secretion via activation of the RNA sensor toll-like receptor 8 (TLR8). Removal of msRNA cargo during LDL re-constitution yields particles that readily promote sterol loading but fail to stimulate inflammatory activation. Competitive antagonism of TLR8 with non-targeting locked nucleic acids was found to prevent native LDL-induced macrophage polarization in vitro, and re-organize lesion macrophage phenotypes in vivo, as determined by single-cell RNA sequencing. Critically, this was associated with reduced disease burden in distinct mouse models of atherosclerosis. These results identify LDL-msRNA as instigators of atherosclerosis-associated inflammation and support alternative functions of LDL beyond cholesterol transport.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Code availability

Informatics tools used for sequencing analysis in this manuscript are available for public use via GitHub (https://github.com/shengqh). Additional support is available through the corresponding authors.

References

Danesh, J., Collins, R., Appleby, P. & Peto, R. Association of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of prospective studies. JAMA 279, 1477–1482 (1998).

Ridker, P. M., Rifai, N., Rose, L., Buring, J. E. & Cook, N. R. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1557–1565 (2002).

Sabatine, M. S. et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 1713–1722 (2017).

Ridker, P. M. et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1119–1131 (2017).

Moore, K. J. & Tabas, I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell 145, 341–355 (2011).

Moore, K. J. & Freeman, M. W. Scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis: beyond lipid uptake. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 1702–1711 (2006).

Babaev, V. R. et al. Reduced atherosclerotic lesions in mice deficient for total or macrophage-specific expression of scavenger receptor-A. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 2593–2599 (2000).

Suzuki, H. et al. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature 386, 292–296 (1997).

Que, X. et al. Oxidized phospholipids are proinflammatory and proatherogenic in hypercholesterolaemic mice. Nature 558, 301–306 (2018).

Febbraio, M. et al. Targeted disruption of the class B scavenger receptor CD36 protects against atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 1049–1056 (2000).

Stewart, C. R. et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat. Immunol. 11, 155–161 (2010).

Miller, Y. I. Toll-like receptors and atherosclerosis: oxidized LDL as an endogenous toll-like receptor ligand. Future Cardiol. 1, 785–792 (2005).

Steinbrecher, U. P. & Lougheed, M. Scavenger receptor-independent stimulation of cholesterol esterification in macrophages by low density lipoprotein extracted from human aortic intima. Arterioscler. Thromb. J. Vasc. Biol. 12, 608–625 (1992).

Steinberg, D. & Witztum, J. L. Is the oxidative modification hypothesis relevant to human atherosclerosis? Do the antioxidant trials conducted to date refute the hypothesis? Circulation 105, 2107–2111 (2002).

Kim, Kyeongdae et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals nonfoamy rather than foamy plaque macrophages are proinflammatory in atherosclerotic murine models. Circ. Res. 123, 1127–1142 (2018).

Fernandez, D. M. et al. Single-cell immune landscape of human atherosclerotic plaques. Nat. Med. 25, 1576–1588 (2019).

Zernecke, Alma et al. Meta-analysis of leukocyte diversity in atherosclerotic mouse aortas. Circ. Res. 127, 402–426 (2020).

Spann, N. J. et al. Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell 151, 138–152 (2012).

Jaiswal, S. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 111–121 (2017).

Estruch, M. et al. CD14 and TLR4 mediate cytokine release promoted by electronegative LDL in monocytes. Atherosclerosis 229, 356–362 (2013).

Lamarche, B., Lemieux, I. & Després, J. P. The small, dense LDL phenotype and the risk of coronary heart disease: epidemiology, patho-physiology and therapeutic aspects. Diabetes Metab. 25, 199–211 (1999).

Smith, E. B. & Ashall, C. Low-density lipoprotein concentration in interstitial fluid from human atherosclerotic lesions. Relation to theories of endothelial damage and lipoprotein binding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 754, 249–257 (1983).

Kruth, H. S., Huang, W., Ishii, I. & Zhang, W.-Y. Macrophage foam cell formation with native low density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34573–34580 (2002).

Goldstein, J. L., Ho, Y. K., Basu, S. K. & Brown, M. S. Binding site on macrophages that mediates uptake and degradation of acetylated low density lipoprotein, producing massive cholesterol deposition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 76, 333–337 (1979).

Anzinger, J. J. et al. Native low-density lipoprotein uptake by macrophage colony-stimulating factor-differentiated human macrophages is mediated by macropinocytosis and micropinocytosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 2022–2031 (2010).

Jackson, W. D., Weinrich, T. W. & Woollard, K. J. Very-low and low-density lipoproteins induce neutral lipid accumulation and impair migration in monocyte subsets. Sci. Rep. 6, 20038 (2016).

Goulopoulou, S., McCarthy, C. G. & Webb, R. C. Toll-like receptors in the vascular system: sensing the dangers within. Pharmacol. Rev. 68, 142–167 (2016).

Seimon, T. A. et al. Atherogenic lipids and lipoproteins trigger CD36-TLR2-dependent apoptosis in macrophages undergoing endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 12, 467–482 (2010).

Mistry, P. et al. Inhibition of TLR2 signaling by small molecule inhibitors targeting a pocket within the TLR2 TIR domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 112, 5455–5460 (2015).

Kadl, A. et al. Identification of a novel macrophage phenotype that develops in response to atherogenic phospholipids via Nrf2. Circ. Res. 107, 737–746 (2010).

Vaeth, M. et al. Ca2+ signaling but not store-operated Ca2+ entry is required for the function of macrophages and dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 195, 1202–1217 (2015).

Heil, F. et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science 303, 1526–1529 (2004).

Tanji, H. et al. Toll-like receptor 8 senses degradation products of single-stranded RNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 109–115 (2015).

Sarvestani, S. T. et al. Sequence-dependent off-target inhibition of TLR7/8 sensing by synthetic microRNA inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 1177–1188 (2015).

Hornung, V. et al. Sequence-specific potent induction of IFN-α by short interfering RNA in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Nat. Med. 11, 263–270 (2005).

Zhang, S. et al. Small-molecule inhibition of TLR8 through stabilization of its resting state. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 58–64 (2018).

Jurk, M. et al. Human TLR7 or TLR8 independently confer responsiveness to the antiviral compound R-848. Nat. Immunol. 3, 499 (2002).

Diebold, S. S., Kaisho, T., Hemmi, H., Akira, S. & Reis e Sousa, C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science 303, 1529–1531 (2004).

Liu, J. et al. A five-amino-acid motif in the undefined region of the TLR8 ectodomain is required for species-specific ligand recognition. Mol. Immunol. 47, 1083–1090 (2010).

Ishii, N., Funami, K., Tatematsu, M., Seya, T. & Matsumoto, M. Endosomal localization of TLR8 confers distinctive proteolytic processing on human myeloid cells. J. Immunol. 193, 5118–5128 (2014).

Gorden, K. K. B., Qiu, X. X., Binsfeld, C. C. A., Vasilakos, J. P. & Alkan, S. S. Cutting edge: activation of murine TLR8 by a combination of imidazoquinoline immune response modifiers and polyT oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Immunol. 177, 6584–6587 (2006).

Allen, R. M. et al. Bioinformatic analysis of endogenous and exogenous small RNAs on lipoproteins. J. Extracell. Vesicles 7, 1506198 (2018).

Krieger, M., Brown, M. S., Faust, J. R. & Goldstein, J. L. Replacement of endogenous cholesteryl esters of low density lipoprotein with exogenous cholesteryl linoleate. Reconstitution of a biologically active lipoprotein particle. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 4093–4101 (1978).

Jonsson, A. L. & Bäckhed, F. Role of gut microbiota in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 14, 79–87 (2017).

Robbins, M. et al. 2’-O-methyl-modified RNAs act as TLR7 antagonists. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 15, 1663–1669 (2007).

Sioud, M., Furset, G. & Cekaite, L. Suppression of immunostimulatory siRNA-driven innate immune activation by 2′-modified RNAs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 361, 122–126 (2007).

Mitchell, S. et al. An NFκB activity calculator to delineate signaling crosstalk: type I and II interferons enhance NFκB via distinct mechanisms. Front. Immunol. 10, Article 1425 (2019).

Rayner, K. J. et al. Antagonism of miR-33 in mice promotes reverse cholesterol transport and regression of atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2921–2931 (2011).

Rahman, S. M. et al. CCAAT/Enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) expression regulates dietary-induced inflammation in macrophages and adipose tissue in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 34349–34360 (2012).

Zernecke, A. & Weber, C. Chemokines in atherosclerosis: proceedings resumed. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 742–750 (2014).

Duewell, P. et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464, 1357–1361 (2010).

Sugiyama, Y., Sugiyama, F., Yagami, K., Miyaji, S. & Kurosawa, T. Comparison of plasma endotoxin levels in germ-free, SPF and conventional laboratory animals (mice and rats). Jikken Dobutsu 42, 89–92 (1993).

Wright, S. D. et al. Infectious agents are not necessary for murine atherogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 191, 1437–1442 (2000).

Stepankova, R. et al. Absence of microbiota (germ-free conditions) accelerates the atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice fed standard low cholesterol diet. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 17, 796–804 (2010).

Patinote, C. et al. Agonist and antagonist ligands of toll-like receptors 7 and 8: ingenious tools for therapeutic purposes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 193, 112238 (2020).

Janssen, H. L. A. et al. Treatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNA. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1685–1694 (2013).

He, T. C. et al. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 2509–2514 (1998).

Michell, D. L. et al. Isolation of high-density lipoproteins for non-coding small rna quantification. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/54488 (2016).

Bligh, E. G. & Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem Physiol. 37, 911–917 (1959).

Paigen, B., Morrow, A., Holmes, P. A., Mitchell, D. & Williams, R. A. Quantitative assessment of atherosclerotic lesions in mice. Atherosclerosis 68, 231–240 (1987).

Linton, M. F., Atkinson, J. B. & Fazio, S. Prevention of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice by bone marrow transplantation. Science 267, 1034–1037 (1995).

Makowski, L. et al. Lack of macrophage fatty-acid-binding protein aP2 protects mice deficient in apolipoprotein E against atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 7, 699–705 (2001).

Babaev, V. R. et al. Macrophage EP4 deficiency increases apoptosis and suppresses early atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 8, 492–501 (2008).

Chen, Y., Yu, Q. & Xu, C.-B. A convenient method for quantifying collagen fibers in atherosclerotic lesions by ImageJ software. Int J Clin Exp Med. 10, 14904–14910 (2017).

Park, E. K. et al. Optimized THP-1 differentiation is required for the detection of responses to weak stimuli. Inflamm. Res. 56, 45–50 (2007).

Fleetwood, A. J., Lawrence, T., Hamilton, J. A. & Cook, A. D. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF) and macrophage csf-dependent macrophage phenotypes display differences in cytokine profiles and transcription factor activities: implications for CSF blockade in inflammation. J. Immunol. 178, 5245–5252 (2007).

Na, Y. R., Jung, D., Gu, G. J. & Seok, S. H. GM-CSF grown bone marrow derived cells are composed of phenotypically different dendritic cells and macrophages. Mol. Cells 39, 734 (2016).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Langmead, B., Trapnell, C., Pop, M. & Salzberg, S. L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25 (2009).

Galkina, E. et al. Lymphocyte recruitment into the aortic wall before and during development of atherosclerosis is partially L-selectin dependent. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1273–1282 (2006).

Liu, Q. et al. scRNABatchQC: multi-samples quality control for single cell RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 35, 5306–5308 (2019).

Stuart, T. et al. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e21 (2019).

Franzén, O., Gan, L.-M. & Björkegren, J. L. M. PanglaoDB: a web server for exploration of mouse and human single-cell RNA sequencing data. Database 2019, 1–9 (2019).

Audzevich, T. et al. Pre/pro-B cells generate macrophage populations during homeostasis and inflammation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E3954–E3963 (2017).

Williams, J. W. et al. Limited proliferation capacity of aortic intima resident macrophages requires monocyte recruitment for atherosclerotic plaque progression. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1194–1204 (2020).

Tacke, R. et al. The transcription factor NR4A1 is essential for the development of a novel macrophage subset in the thymus. Sci. Rep. 5, 10055 (2015).

Sarrazy, V. et al. Maintenance of macrophage redox status by ChREBP limits inflammation and apoptosis and protects against advanced atherosclerotic lesion formation. Cell Rep. 13, 132–144 (2015).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Greenwald, R. A. CRC Handbook of Methods for Oxygen Radical Research (CRC Press, 1987).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank W. Reichard, M. Kuzmich, S. Landstreet, A. Ifram, L. Sedgeman, C. Wiese and V. Babaev for technical assistance and helpful discussions. We also thank Q. Liu of the Vanderbilt Center for Quantitative Sciences for consultation on single-cell sequencing analysis, and A. Jones of VANTAGE at VUMC for expertise in high-throughput sequencing technologies, the Vanderbilt Flow Cytometry Shared Resource and Translational Pathology Shared Resource. This work is supported by American Heart Association awards 19CDA34660280 (R.M.A.) and 18IPA34180005 (R.M.A.), W.M. Keck Research Foundation Grant (K.C.V., R.M.A., M.F.L. and Q.S.) and National Institutes of Health grants P01HL116263 (M.F.L.) and R01HL128996 (K.C.V.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M.A.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization and writing—original draft. D.L.M.: methodology, investigation, formal analysis and writing—reviewing and editing. A.B.C.: investigation and formal analysis. N.M.: investigation and formal analysis. E.M.S.: formal analysis and investigation. D.M.C.: resources and formal analysis. W.Z.: resources. C. DeJulius: resources. M.C.: resources. Y.Z.: resources. C.A.R.: formal analysis. M.R.-S.: software and visualization. S.Z. software and visualization. C. Duvall: methodology. A.C.D.: methodology and writing—reviewing and editing. Q.S.: methodology, software, visualization and writing—reviewing and editing. M.F.L.: methodology, supervision and writing—reviewing and editing. K.C.V.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, formal analysis, visualization and writing—reviewing and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.F.L. has received research funding from Amgen, Regeneron, Ionis, Merck, REGENXBIO, Sanofi and Novartis, and has served as a consultant for Esperion, Alexion Pharmaceuticals and REGENXBIO. All other authors have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cell Biology thanks Jeffrey Kroon and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 nLDL induces inflammatory activation of macrophages.

(a) mRNA expression determined by qPCR of THP-1 macrophages treated with indicated doses of nLDL (matched to Fig. 1f) for 24 h (n = 3 biological replicates). (b) Quantification of immunoblots presented in Fig. 1f (n = 3 biological replicates). (c) Secreted cytokines in the media of THP-1 macrophages stimulated with 0.5 mg/ml nLDL for 3 h, 6 h, 24 h relative to cells receiving no treatment for 24 h (Ctr) (matched to Fig. 1e; n = 3 biological replicates) (d) Primary mouse bone-marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) differentiated with GM-CSF were treated with nLDL (0.5 mg/ml) for 24 h and assayed for mRNA expression by qPCR (n = 3 biological replicates), (e) cytokine secretion by ELISA (n = 3 biological replicates), and (f) protein expression in cell lysates by immunoblot (n = 2 biological replicates). Data are mean ± SEM. (a-c) One-way ANOVA and (d) Two-way ANOVA with Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli FDR (Q = 0.05), *q < 0.05, **q < 0.01, ***q < 0.001, ****q < 0.0001. e, Student’s t-test (unpaired, two-sided), **p < 0.01. Numerical source data, statistics, exact p values and q values are provided.

Extended Data Fig. 2 nLDL and macrophage TLR responses quality control.

(a) Total protein (top) and neutral lipid (bottom) of ox LDL, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 10 human nLDL of independent donors resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis. Image represents two independent experiments. (b) TBARS assay of nLDL samples, or matched LDL samples treated with copper sulfate as indicated (limit of detection = 0.625 μM) (n = 10 independent preparations). (c) Quantification of total protein and lipids of DGUC-VLDL, -LDL, -HDL, or BSA following fractionation with 2x-Superose-6 columns. Lipoprotein data are matched to a single donor representative of >10 independent experiments. (d) mRNA expression of primary human macrophages (CD14 + ; GM-CSF/IFNγ) pre-treated with C29 (200 μM) for 30 min, then stimulated with PAM3CSK4 (2 ng/mL) for 4 h (n = 3 biological replicates(BR)). (e) Normalized NF-κB-driven luciferase activity of HEK293T cells over expressing an empty vector, hTLR7 or hTLR8 following treatments with vehicle (Ctr, n = 4 BR), nLDL (0.5 mg/ml, n = 4 BR), ssRNA40 (TLR8 ligand; 2 μg/mL, n = 4 BR), R848 (TLR7 ligand; 10 μM, n = 3 BR), or CL075 (TLR8 ligand; 2.5 μg/mL, n = 3 BR). (f-h) mRNA expression of THP-1 macrophages electroporated with siRNA against TLR7,TLR8, or no siRNA (Control, n = 4 BR) and then treated with (f) nLDL (0.5 mg/mL, n = 6 BR), (g) R848 (10 μM, n = 6 BR) or (h) ssRNA40 (0.5 μg/mL, n = 6 BR). (i) Relative NF-κB-driven luciferase activity of HEK293T cells over expressing an empty vector (n = 7–8), mTLR7 (n = 7–8) or mTLR8 (n = 6-8) treated with mock transfection, R848 (10 μM), ssRNA40 (2 μg/mL), or nLDL (0.5 mg/ml) for 24 h. (j) mRNA expression in wild-type (WT) and Tlr7-/- BMDMs following treatment with 0.5 mg/ml nLDL, or 1 μg/mL ssRNA40 for 24 h (n = 3 BR). (k) Relative NF-κB-driven luciferase activity of HEK293T cells over expressing human or mTLR8 pre-treated with CU-CPT9a and exposed to nLDL for 24 h (n = 4 BR). Data are mean ± SEM. (d) Two-way ANOVA; Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. (e, i-k) Two-way ANOVA; Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli FDR (Q = 0.05), *q < 0.05, **q < 0.01, ***q < 0.001). (f-h) One-way ANOVA; Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Numerical source data, statistics, exact p values and q values are provided.

Extended Data Fig. 3 The small RNA on LDL is predominantly exogenous and removed by LDL re-constitution.

a) Normalized abundance of taxa identified upon alignment of LDL-sRNA to non-host tRNA database (tRNA-db). RPM, reads per million total reads. b) Normalized abundance of bacterial phyla (human microbiome database) contributing sRNA to LDL. c) Normalized abundance of fungal sRNA and representative genomes present on LDL. d) Normalized abundance of algal and protist sRNA and representative genomes present on LDL. RPM, reads per million total reads. Matched nLDL and rLDL samples were fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) using two superose-6 columns in tandem and assessed for e) phospholipid and protein content by colorimetric kit (representative data of three independent experiments), f) fluorescence (TopFluor Cholesteryl ester), and g) APOB protein by immunoblot (representative image of three independent experiments). h) Relative expression of exogenous sRNA in matched rLDL and nLDL of a single preparation relative to buffer controls. i) Oil-Red-O staining and fluorescence microscopy (TopFluor Cholesterol ester) (representative images of three biological replicates). Scale bar = 200 μm. Numerical source data, statistics, exact p values and q values are provided.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Microbial small RNA on lipoproteins is not depleted in germ-free mice.

a) Plasma from two cohorts of adult mice - specific pathogen free (SPF; n = 6 mice total) and facility-matched germ-free (GF; n = 17 mice total) fed a chow diet were harvested at the National Gnotobiotic Rodent Resource Center (NGRRC; North Carolina, USA) for lipoprotein sRNA-seq b) Plasma was fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and cholesterol-rich fractions corresponding with HDL were selected for sRNA-seq. c) Relative percentage of reads aligned to host and non-host databases, as well as reads too short for analysis or reads that failed to align to either database (unmapped). d) Percentage of sRNA reads aligned to host miRNA, host tRNA and host rRNA transcripts. e) Percentage of reads aligned to the non-host rRNA database and tRNA database. f) Percentage of reads aligned to genomes of fungi and algae. g) Percentage of reads aligned to bacterial genomes associated with a human microbiome (HMB) database. h) Reads per million total reads (RPM) mapped to indicated bacterial phyla within the HMB database. i) Percentage of reads aligned to bacterial genomes within an environmental bacteria (ENV) database. j) Differential abundance (log2) of bacterial sRNA (dots represent individual genomes of the HMB and ENV databases) between GF and SPF mice categorized by phyla. Gray bar represents a 1.5 fold change. Data are mean ± SEM. (d-g, i) Statistical differences between GF and SPF were assessed by Mann-Whitney U-test, but no evaluations were statistically significant. j) Differences in abundance of individual genomes within each database were assessed between groups by the Wald Test, but applying False Discovery Rate correction (α = 0.05) resulted in no differentially abundant genomes. Numerical source data, statistics, exact p values and q values are provided.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Locked nucleic acid (LNA) bases mediate antagonism of single-stranded RNA ligands of TLR8.

a) HEK293T cells over-expressing human TLR8, UNC93B1 and CD14 were pre-treated with vehicle (DOTAP) or corresponding DNA/LNA oligonucleotides (2.5 μg/mL) for 30 min and then stimulated with TLR8 nucleoside analogue agonist CL075 or TLR8 ORN agonists ssRNA40 or ORN06 (2 μg/mL) for 24 h (n = 5 biological replicates). Two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (statistical significance relative to untreated within each group; **p < 0.0001). b) THP-1 macrophages were pre-treated + /- nt-LNA (1 µg/mL) for 45 min and treated with LPS (500 ng/mL), Poly I:C (1 µg/mL), CL075 (2.5 μg/ml), or ssRNA40 at 1 µg/mL (1:1, nt-LNA:ssRNA40) or 0.2 µg/ml (5:1) for 24 h (n = 3 biological replicates). Relative mRNA expression of IL1B, IL6 and TNF were then assessed by qPCR. For each treatment, the relative fold change of each treatment in the presence of nt-LNA was expressed as a percentage of the relative fold change of each treatment without nt-LNA pre-treatment (% inhibition). Two-way ANOVA, Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli FDR (Q = 0.05), **q < 0.01. c-d) Primary human CD14 + PBMC differentiated with GM-CSF and IFNγ were pre-treated with 2.5 μg/mL nt-LNA or vehicle (DOTAP) for 30 minutes and then stimulated with or without ssRNA40 (0.5 μg/mL) for 24 h. c) mRNA expression was quantified by qPCR (n = 4 biological replicates) d) Cytokine (IL-6) secretion was quantified by ELISA (n = 4 biological replicates). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (e) mRNA expression (n = 4 biological replicates), (f) cytokine secretion (n = 3 biological replicates) and (g) immunoblotting (representative image of three independent experiments) of BMDMs following up to 24 h treatment with IFNγ (100 U/mL) +/- 0.5 mg/ml nLDL in the presence or absence of 2.5 μg/mL nt-LNA. Two-way ANOVA, Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli FDR (Q = 0.05), *q < 0.05, **q < 0.01. Data are mean ± SEM. Numerical source data, statistics, exact p values and q values are provided.

Extended Data Fig. 6 nt-LNA treatment reduces atherosclerosis without altering lipid or lipoprotein metabolism in Apoe-/- mice.

a) Female and male Apoe-/- mice fed a western diet were administered saline (Ctr; n = 4 mice per sex), nt-LNA-A (20 mg/kg; n = 4 mice per sex) or nt-LNA-B (20 mg/kg; n = 4 mice per sex) by intraperitoneal injection once weekly for four weeks. Treatments for each were randomized between cohabitating animals separated by sex. At sacrifice, the aortic sinus was serially sectioned and stained with Oil-Red O to identify atherosclerotic lesions. Scale bar = 500 μm. b) Quantification of lesion area in serial sections and c) sex-normalized, relative lesion area under the curve (n = 8 mice per treatment). d) Plasma of female Apoe-/- mice treated for 4 weeks with saline (Ctr; n = 10) or nt-LNA (n = 10) were fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography and assessed for total cholesterol (TC) e) Plasma protein levels were assessed by immunoblot of individual cages receiving either Saline/Ctr (n = 5 mice) or nt-LNA (n = 5 mice) treatments (representative images of two independent assessments). f) Quantification of independent immunoblots by densitometry (n = 10 mice per treatment) normalized to C3. g) Lesion area (Oil-red O) of matched sections of the aortic root following treatment with saline (Ctr) or nt-LNA for 4 weeks (n = 10 mice per treatment). h) Hepatic mRNA expression determined by qPCR (n = 10 mice per treatment). Data are mean ± SEM. (c) One-way ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparison test, *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. (f-h) Two-way ANOVA with Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli FDR (Q = 0.05), *q < 0.05, **q < 0.01,***q < 0.001. Numerical source data, statistics, exact p values and q values are provided.

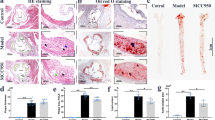

Extended Data Fig. 7 nt-LNA treatment promotes atherosclerotic regression in Ldlr-/- mice.

(a) Schematic for regression study design. Male(M) and female(F) Ldlr-/- mice were fed a chow diet (n = 6 mice) or an atherogenic diet (n = 50 mice) for 14 weeks. After 14 weeks, chow-fed mice and a subset of mice from the atherogenic diet group (baseline; n = 7 M/8 F mice). Remaining diet-fed mice were then switched to a chow diet to allow lesion regression (Reg.) and were injected once weekly with saline control (Reg. Ctr; n = 9 M/9 F mice) or Reg. nt-LNA (30 mg/kg; n = 9 M/8 F mice). b) Plasma total cholesterol (TC) or c) triglycerides (TG) following fractionation by SEC; chow (n = 6; 3 M/3 F), baseline (n = 8; 4 M/4 F), Reg. Ctr; (n = 10; 5 M/5 F) and Reg. nt-LNA (n = 10; 5 M/5 F) d) Immunoblots of plasma proteins in Reg. Ctr (n = 10) or Reg. nt-LNA (n = 9) groups. Representative images of two independent experiments are shown. e) Quantification of immunoblots by densitometry. f-g) Lesion area of serial sections of the aortic root in baseline (n = 15 mice; 7 M/8 F), Reg. Ctr(n = 18 mice; 9 M/9 F) or nt-LNA (n = 17; 9 M/8 F) groups. h) Lesion area under the curve (AUC) for both sexes of mice as determined by Oil Red O staining in the aortic root (Baseline: n = 15; Reg. Ctr: n = 18; Reg. nt-LNA; n = 17). One-way ANOVA; Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. i) Lesion AUC for mice of each group separated by sex. Two-way ANOVA; Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, **p < 0.01. j-k) Masson’s Trichrome staining and quantification of fibrosis in aortic roots of baseline (n = 7 mice; 3 M/4 F) Reg. Ctr (n = 9 mice; 4 M/5 F) or Reg. nt-LNA (n = 10 mice; 5 M/5 F) groups. l-m) MAC2 (green) immunofluorescence and quantification within aortic roots obtained of at baseline (n = 7 mice; 3 M/4 F), Reg. Ctr (n = 10 mice; 5 M/5 F), or Reg. nt-LNA (n = 10 mice; 5 M/5 F) groups. Two-way ANOVA; Tukey’s multiple comparison test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM. Scale bar = 500 μm. Numerical source data, statistics, exact p values and q values are provided.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Gating strategy of leukocytes from mouse aortas for single-cell RNA sequencing.

Sequential gating fluorescent activated cell sorting for single and live cells, followed by non-red blood cells. Cells were then sorted that were CD45 + but CD3−.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Single-cell RNA sequencing of the atherosclerotic lesion to identify anti-atherosclerotic mechanisms of nt-LNA treatment.

a) Apoe-/- mice fed an atherogenic diet for 4 weeks were injected once weekly with saline control (Ctr; n = 8) or nt-LNA (30 mg/kg; n = 8). b) UMAP projection of unbiased clusters obtained from atherosclerotic lesions. c) Relative contribution of cells from saline (Ctr) and nt-LNA treated mice to each cluster of (b). d) Relative expression (color) and % of cells reaching threshold of detection (size) of transcripts pertaining to T cell and NK cell phenotypes (top) or B-cell phenotypes (bottom) in atherosclerosis for each cluster. Numerical source data, statistics, exact p values and q values are provided.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 1

Uncropped Western blots.

Source Data Fig. 2

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Uncropped Western blots.

Source Data Fig. 3

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Uncropped Western blots.

Source Data Fig. 5

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Numerical source data.

Source Data Fig. 7

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Uncropped Western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Uncropped Western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Uncropped Western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Uncropped Western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Uncropped Western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Numerical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Uncropped Western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Numerical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, R.M., Michell, D.L., Cavnar, A.B. et al. LDL delivery of microbial small RNAs drives atherosclerosis through macrophage TLR8. Nat Cell Biol 24, 1701–1713 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-022-01030-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-022-01030-7

This article is cited by

-

Proteomic and lipidomic analysis of low-density lipoprotein identifies potential biomarkers of early estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer

Cancer & Metabolism (2025)

-

Fortilin deficiency induces anti-atherosclerotic phenotypes in macrophages and protects hypercholesterolemic mice against atherosclerosis

Communications Biology (2025)

-

A high-cholesterol diet promotes the intravasation of breast tumor cells through an LDL–LDLR axis

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Blood Lipoproteins Shape the Phenotype and Lipid Content of Early Atherosclerotic Lesion Macrophages: A Dual-Structured Mathematical Model

Bulletin of Mathematical Biology (2024)