Abstract

Lipid droplets (LDs) are organelles that store and supply lipids, based on cellular needs. Although mechanisms preventing oxidative damage to membrane phospholipids are established, the vulnerability of LD neutral lipids to peroxidation and protective mechanisms are unknown. Here we identify LD-localized ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) as a critical regulator that prevents neutral lipid peroxidation by recycling coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) to its lipophilic antioxidant form. Lipidomics reveal that FSP1 loss leads to the accumulation of oxidized triacylglycerols and cholesteryl esters, and biochemical reconstitution of FSP1 with CoQ10 and NADH suppresses triacylglycerol peroxidation in vitro. Notably, inducing polyunsaturated fatty acid-rich LDs triggers triacylglycerol peroxidation and LD-initiated ferroptosis when FSP1 activity is impaired. These findings uncover the first LD lipid quality-control pathway, wherein LD-localized FSP1 maintains neutral lipid integrity to prevent the build-up of oxidized lipids and induction of ferroptosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Lipid droplets (LDs) are the primary cellular organelle for lipid storage1,2. During LD biogenesis, neutral lipids such as triacylglycerols (TGs) and cholesteryl esters (CEs) accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) bilayer, forming a lipid lens that eventually buds into the cytoplasm1,3. LDs contain a neutral lipid core encircled by a phospholipid monolayer decorated with regulatory proteins1,4. Functionally, LDs serve as dynamic lipid storage depots, supplying lipids for biosynthesis and energy while protecting cells by sequestering potentially harmful species1,5,6.

Cells employ sophisticated quality-control mechanisms to preserve the integrity of biomolecules, including ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation7 and DNA damage repair8. Lipids are also vulnerable to damage, such as oxidation, necessitating lipid quality-control systems to prevent and counteract such damage9. Characterized by unchecked phospholipid peroxidation and consequent plasma membrane rupture, ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death that represents a failure of lipid quality control9,10,11,12,13,14. To suppress ferroptosis, cells rely on specialized lipid quality-control mechanisms. The glutathione-dependent peroxidase GPX4 plays a pivotal role by converting lipid peroxides into benign lipid alcohols15,16. In parallel, FSP1 suppresses ferroptosis by recycling quinone antioxidants (CoQ1017,18 and vitamin K19,20), which quench lipid radicals and block their propagation.

Cells also modulate ferroptosis sensitivity by regulating membrane lipid composition. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are prone to peroxidation compared to monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and increasing the phospholipid MUFA:PUFA ratio reduces ferroptosis sensitivity across various contexts21,22. This shift can be achieved by supplementing cells with excess MUFAs (for example, oleate)23 or by the regulation of lipid metabolic enzymes such as acyl-CoA synthetase (ACSL)-dependent fatty acid activation24,25,26 or membrane-bound O-acyltransferase (MBOAT) family-dependent fatty acid incorporation into phospholipids27,28,29. LDs have also been implicated in the regulation of phospholipid MUFA:PUFA composition. By sequestering PUFAs in stored TGs, LDs restrict their incorporation into membrane phospholipids, thereby decreasing membrane oxidizability and reducing cellular susceptibility to ferroptosis10,11,12,14.

The mechanisms underlying membrane phospholipid peroxidation have been extensively studied, but much less is known about the susceptibility of LD-residing neutral lipids to peroxidation. Whether neutral lipids within LDs are prone to oxidative damage and what cellular mechanisms exist to protect them remain largely unexplored. In this article we uncover a lipid quality control pathway for LDs in which FSP1 acts at LDs to safeguard stored neutral lipids from peroxidation and prevent LD-initiated ferroptosis.

Results

FSP1 is required to maintain PUFA-containing di- and triacylglycerols

To advance our understanding of the specific lipids protected by FSP1, we performed untargeted lipidomics to analyse the lipid profiles of FSP1 knockout (KO) cells and KO cells expressing doxycycline (DOX)-inducible wild-type (WT) or catalytically inactive E156A mutant FSP1 (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1a). FSP1 is a key ferroptosis resistance factor in U-2 OS osteosarcoma cells18. However, the basal levels of neutral lipids and LDs in this cell type are low, limiting the ability to assess the potential role of FSP1 in the regulation and peroxidation of stored neutral lipids. Therefore, to increase neutral lipids and LDs, we supplemented the cells with a mixture of oleate (fatty acid (FA) 18:1) and arachidonate (FA 20:4) (3:1 ratio) (Extended Data Fig. 1b,c).

a, Volcano plots of untargeted lipidomics data comparing the global lipidomes of WT versus FSP1 KO and FSP1-GFP versus FSP1(E156A)-GFP re-expression constructs (GFP, green fluorescent protein). Lipid classes are coloured according to the legend. Cer, ceramide; DG, diacylglcyerol; TG, triacylglycerol; CE, cholesteryl ester; PC, phosphatidylcholine; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; LPE, lysophosphatidylethanolamine; SM, sphingomyelin; PS, phosphatidylserine; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PG, phosphatidylglycerol. Data are autoscaled and log10-transformed. Thresholds for significant regulation are fold change (FC) > 2. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided t-test, and values were deemed significant if P < 0.05 (false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected)). b, Heatmap displaying a cluster of lipids that are protected by catalytically active FSP1 as identified by hierarchical clustering in Extended Data Fig. 1d. Data are autoscaled and log10-transformed. c, Volcano plots of untargeted lipidomics data comparing TG lipids of WT versus FSP1 KO and FSP1-GFP versus FSP1(E156A)-GFP re-expression constructs. TG unsaturation is coloured according to the legend. SFA, saturated fatty acid containing (total double bonds = 0); MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid containing (total double bonds = 1); PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid containing (total double bonds ≥ 4); MUFA or PUFA containing (total double bonds = 2 or 3). Data are autoscaled and log10-transformed. Thresholds for significant regulation are fold change > 2. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided t-test, and values were deemed significant if P < 0.05 (FDR-corrected)). d, Selected lipids from the FSP1-protected lipid cluster. ISTD, internal standard. Raw data are plotted. Data are presented as mean values ± s.d., n = 4. Statistical significance is assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; *P < 0.05).

Lipidomics revealed extensive alterations in lipid abundance across the experimental conditions (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1d). Unbiased hierarchical clustering identified a subset of lipids that were preserved, or protected, by active FSP1 but not the catalytically inactive E156A mutant FSP1 (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1d; representative examples are shown in Fig. 1d). This cluster of lipids included highly unsaturated phospholipids, such as phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and phosphatidylserine (PS), as well as many neutral lipids, consistent with dual membrane and LD protective roles (Fig. 1b). FSP1 KO cells showed a shift from PUFA-TGs to saturated TGs (Fig. 1a–c and Extended Data Fig. 1e), revealing its role in maintaining unsaturated neutral lipids.

In addition to the lipids that decreased upon FSP1 KO, a subset of lipids showed increased levels. CEs were elevated in FSP1 KO cells, a change that was reversed by the expression of WT FSP1 and partially reversed by the catalytically inactive E156A mutant FSP1 (Fig. 1a,d and Extended Data Fig. 1e). CEs have been implicated in preventing TG lipid peroxidation as sacrificial antioxidants in vitro30, similar to the cholesterol intermediate 7-dehydrocholesterol31,32,33, suggesting that their increase may reflect an adaptive compensatory mechanism. We also observed an increase in some MUFA-TG species, particularly in cells expressing E156A mutant FSP1. The importance of this change is unclear, but would be predicted to be protective and could similarly indicate an adaptive mechanism.

FSP1 is required to prevent oxidative damage to cellular PUFA-containing neutral lipids

A potential explanation for the observed reduction in PUFA-containing TGs in FSP1 KO cells (Fig. 1) is that they are being oxidized and thus no longer detected. Given the immense complexity of lipid species and their oxidized derivatives, we employed a semi-targeted liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) approach for sample-specific epilipidome profiling19,31,34,35 for the measurement of oxidized lipids enriched in FSP1 KO cells. We detected numerous oxidized neutral lipids that selectively accumulated in FSP1 KO cells, including oxidized TGs and CEs (Fig. 2a,b). These findings implicate FSP1 as a key factor in protecting neutral lipids from oxidative damage.

a, Volcano plots of untargeted epilipidomics data comparing oxidized lipids of WT versus FSP1 KO. Oxidized lipid class is coloured according to the legend. Data are autoscaled and log10-transformed. Thresholds for significant regulation are fold change > 2. Statistical significance was assessed by a two-sided t-test, and values were deemed significant if P < 0.05 (FDR-corrected). b, Example MS/MS spectra from parallel reaction monitoring-based analysis of sodiated ions of oxidized TG and CE displaying informative fragments necessary for oxidized TG and CE identification. Inset: parallel reaction monitoring-based quantification of the targeted transition (applied mass accuracy for extracted ion chromatogram generation = 5 ppm). c, Cartoon depiction of constructs re-expressed in FSP1 KO cells to study the role of FSP1 catalytic activity and subcellular localization. d, Selected oxidized lipids significantly elevated by FSP1 KO. Raw data are plotted, and data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 4. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA (*P < 0.05; NS, not significant). e, Heatmap displaying only oxidized TG and oxidized CE lipids extracted from a cluster of oxidized lipids that are protected by catalytically active FSP1, as identified by hierarchical clustering in Extended Data Fig. 3a. Data are autoscaled and log10-transformed. f, Cell death sensitivity to RSL3, assessed by time-resolved fluorescence microscopy (IncuCyte) with the cell death indicator SYTOX Green over the course of 24 h. The number of SYTOX Green-positive objects per image equals the number of dead cells and is normalized to cell area per image, expressed as confluency. sg+ indicates SYTOX Green-positive objects. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3. g, LD50 (lethal dose, 50%) values for RSL3 in different cell lines under standard conditions or LD-inducing conditions, determined by time-resolved fluorescence microscopy (IncuCyte) using SYTOX Green. LD50 values are calculated as the inflection point from the RSL3 dose–response curve under each condition. FA18:1, oleate; FA20:4, arachidonate. Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; NS, not significant. h, Cell death sensitivity to RSL3 assessed by time-resolved fluorescence microscopy (IncuCyte) with SYTOX Green over the course of 24 h. The number of SYTOX Green-positive objects per image equals the number of dead cells and is normalized to cell area per image expressed as confluency. sg+, SYTOX Green-positive objects. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3).

FSP1 localizes to multiple organelles, including LDs17,18, raising the possibility that FSP1 influences oxidative damage to distinct sets of lipids at these discrete subcellular sites. To investigate the possibility that FSP1 acts directly on LDs, we analysed cell lines expressing a panel of FSP1 constructs18 (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2a,b), including WT FSP1, catalytically inactive E156A mutant FSP1, myristoylation-defective G2A mutant FSP1, which impairs FSP1 membrane and LD recruitment, and a construct targeting FSP1 selectively to LDs (that is, FSP1 fused to PLIN2). Expression of WT FSP1 substantially suppressed the loss of PUFA-containing glycerolipids and the peroxidation of TGs and CEs in FSP1 KO cells (Fig. 2d,e and Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). In contrast, the E156A and G2A mutants exhibited diminished protective effects, highlighting the importance of FSP1’s enzymatic activity and membrane association (Fig. 2d,e). Remarkably, FSP1 targeted selectively to LDs by fusion to PLIN2 strongly suppressed TG and CE peroxidation (Fig. 2d.e), suggesting that FSP1 acts directly at LDs to preserve the integrity of stored TGs and CEs.

FSP1 is well established as a ferroptosis suppressor17,18, but its specific roles in LD function and the cellular consequences of oxidized neutral lipids are unknown. WT FSP1, but not the catalytically inactive E156A mutant, conferred resistance to RSL3-induced ferroptosis in FSP1 KO cells grown under both standard conditions (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d) or under fatty acid-supplemented conditions that induce LD biogenesis (Fig. 2f). Our previously published results indicated that plasma membrane-targeted FSP1 was sufficient to suppress ferroptosis, but that LD-targeted FSP1 had no effect of ferroptosis resistance18. However, those assays were performed under standard growth conditions18, in which U-2 OS cells have low TG levels and few LDs. To investigate the impact of LD-localized FSP1 and neutral lipid peroxidation on ferroptosis, we performed dose–response analyses for RSL3 in our panel of FSP1-targeted cell lines pretreated with fatty acids to induce LDs. As anticipated, WT FSP1 prevented RSL3-induced cell death under both standard and fatty acid-supplemented conditions, whereas the E156A and G2A mutants failed to confer protection (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). Interestingly, although LD-targeted FSP1 (that is, FSP1-PLIN2) exhibited no protective effect under standard growth conditions, consistent with our previous results18, it suppressed ferroptosis under fatty acid-supplemented conditions in which cells contain LDs (Fig. 2g,h). These findings highlight the context-specific role of LD-localized FSP1 in protecting stored neutral lipids from oxidative damage and suppressing ferroptosis.

CoQ10 is present in LDs isolated from cells

To investigate the presence of FSP1 substrates in intracellular LDs, we established a targeted LC–MS/MS method to detect derivatives of coenzyme Q, vitamin K and vitamin E in LD-enriched buoyant fractions. As anticipated, these fractions were highly enriched with TG and CE (Fig. 3a). Among the quinone antioxidants, only CoQ10 (and small amounts of CoQ9) was detected in the LD fractions (Fig. 3b). To gain quantitative insights, we developed an absolute quantification method by spiking in isotopically labelled CoQ10, enabling the precise measurement of oxidized CoQ10, reduced CoQ10H2 and total CoQ10 levels in LD-enriched fractions. LD CoQ10 was present at ~1 per 2,000 neutral lipid molecules, with ~60% of CoQ10 in the reduced form (CoQ10H2) (Fig. 3c). These findings raise the possibility that FSP1 acts through local recycling of CoQ10 to maintain LD antioxidant capacity and prevent neutral lipid peroxidation.

a, Thin-layer chromatogram of lipids extracted from LD fractions. b, Parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) used for the relative quantification of known FSP1 substrates in LD fractions generated by density gradient centrifugation from cell lysates. Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3. c, Absolute quantification of CoQ10 levels by PRM in LD fractions spiked with an isotopically labelled CoQ10 internal standard. Levels of CoQ10 were normalized to total amounts of TG and CE lipids, quantified via thin-layer chromatography. Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3. d, Cartoon describing the FENIX assay, adapted for artificial LDs after recruitment of recombinant FSP1. e, FENIX assay in artificial LDs with various substrate and enzyme compositions. f, FENIX assay in artificial LDs in the presence and absence of catalytically active FSP1 or the catalytically inactive FSP1(E156A) mutant. g, FENIX assay in artificial LDs in the presence of 100 nM FSP1, 10 µM CoQ10, 1 mM total lipid and varying concentrations of NADH. NADH consumption throughout the FENIX assay was assessed via NADH autofluorescence within the same experiment. h,i, FENIX assay in artificial LDs in the presence of increasing concentrations of CoQ10 (h) or α-tocopherol (i, αTOC). j,k, PRM-based quantification of TG and PC oxidation products during the peroxidation of artificial LDs. Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3.

FSP1 suppresses oxidative damage to TG in a biochemically reconstituted system

To examine the mechanisms of FSP1 in suppressing lipid peroxidation, we used biochemically reconstituted approaches. Purified recombinant His-tagged WT FSP1, but not the E156A mutant, displayed the expected activity, consuming NADH in the presence of the soluble CoQ10 analogue CoQ1 and reducing the soluble and fluorescent CoQ10 analogue CoQ1-coumarin to its quinol form in the presence of NADH (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). To determine whether recombinant FSP1 can suppress lipid peroxidation using CoQ10, we generated liposomes containing nickel-conjugated phospholipids to recruit His-tagged FSP1 to the liposome surface (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Employing the FENIX (fluorescence-enabled inhibited autoxidation) assay36, lipid peroxidation was triggered using the lipid radical initiator di-tert-undecyl hyponitrite (DTUN) and lipid peroxidation propagation followed by BODIPY-C11 fluorescence (Extended Data Fig. 4e). In this reconstituted liposome system, WT FSP1, but not the E156A mutant, prevented lipid peroxidation when its substrates NADH and CoQ10 were present (Extended Data Fig. 4e,f). FSP1 also efficiently suppressed lipid peroxidation in the presence of NADH and the vitamin E derivative α-tocopherol (Extended Data Fig. 4g).

When carefully examining the controls, we noted that FSP1 rescued lipid peroxidation in liposomes and artificial LDs in the absence of exogenously added CoQ10. We wondered whether FSP1 directly reduces lipid radicals, and we examined this possibility by tracking the formation of TG alkoxyl radicals using LipiRadicalGreen37. However, FSP1 only reduced lipid radicals in the presence of CoQ and NADH, but not in the presence of NADH itself (Extended Data Fig. 4h), indicating that other mechanisms govern the observed background activity. We hypothesized that the recombinant FSP1 preparations contain low levels of CoQ that were copurified from bacteria. To test this hypothesis, we implemented a targeted quantification method for CoQ10 and its bacterial isoform CoQ8. We indeed identified CoQ8 in recombinant FSP1 preparations (Extended Data Fig. 4i). We tested two protocols to remove CoQ by using bovine serum albumin (BSA)/CoQ10 as a model system, and identified that protein-bound CoQ10 can be removed by the non-denaturing organic solvent 1-BuOH (Extended Data Fig. 4j). This workflow was applied to CoQ10/BSA and recombinant FSP1, and resulted in ~50% loss of protein concentration (Extended Data Fig. 4k,l) and a complete loss of FSP1 activity (Extended Data Fig. 4m), indicating that this protocol was incapable of effectively removing CoQ and simultaneously maintaining enzymatic function. Thus, although FSP1 suppresses phospholipid peroxidation, there is some background activity due to copurified bacterial CoQ8.

To test the ability of FSP1 to directly protect TG from oxidative damage in LDs, we developed a modified FENIX assay that uses artificial LDs generated in vitro (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 5a). Artificial LDs composed of TG cores and a phospholipid monolayer, ~290 nm in diameter (Extended Data Fig. 5b,c), were validated by thin-layer chromatography (Extended Data Fig. 5d,e) and the fluorescence emission spectrum of the solvatochromatic dye Nile Red (Extended Data Fig. 5f). Similar to our liposome assays, His-tagged FSP1 was recruited to the LD surface using nickel-conjugated phospholipids (Extended Data Fig. 5h). Following the initiation of lipid peroxidation with DTUN, we observed unrestricted lipid peroxidation based on the oxidation of BODIPY-C11 (Fig. 3e). The addition of NADH marginally reduced the rate of lipid peroxidation (Fig. 3e). However, NADH did not fully prevent lipid peroxidation, as indicated by the absence of a lag phase. In contrast, the addition of FSP1, together with CoQ10 and NADH, resulted in full inhibition of lipid peroxidation propagation, evident by an extended lag phase (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 5i). It should be noted that the background lipid peroxidation-suppressing function of FSP1 is also observed in artificial LD oxidations (Fig. 3e), and is even more pronounced than in liposomes. As expected, the E156A mutant FSP1 had no effect on the kinetics of lipid peroxidation (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 5j). In the presence of FSP1, NADH and CoQ10, the lag phase continued for approximately 10,000 s and then unrestricted lipid peroxidation was observed (Fig. 3e,f). These findings suggested that a component within the reaction was being consumed. Indeed, the addition of increasing concentrations of NADH resulted in an extension in the lag phase followed by lipid peroxidation upon complete consumption of NADH (Fig. 3h). In contrast, addition of higher amounts of CoQ10 did not affect the reaction (Fig. 3h), indicating that 1 µM CoQ10 is sufficient to drive maximal suppression of lipid peroxidation in this assay and that the low levels of copurified CoQ8 are already sufficient to drive near-maximal lipid peroxidation suppression. FSP1 was also able to suppress lipid peroxidation in the presence of NADH together with the vitamin E derivative α-tocopherol or the vitamin K derivative menaquinone-4 (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 5k). Given that we were unable to detect α-tocopherol or menaquinone-4 in LDs purified from our cells, it is likely that FSP1 uses CoQ10 to prevent neutral lipid peroxidation in LDs. However, there may be cell types or metabolic conditions in which α-tocopherol or menaquinone-4 are present in LDs, and FSP1 could employ these other quinone antioxidants to maintain LD lipid quality.

In vitro-generated artificial LDs contain both phospholipids and TGs. An indirect lipid peroxidation indicator such as BODIPY-C11 is unable to discern which lipids are oxidized. Semi-targeted oxidized epilipidomics analyses revealed that FSP1, together with CoQ10 and NADH (but also NADH alone due to the background activity of copurified CoQ8), suppressed the oxidation of both TGs (Fig. 3j and Extended Data Fig. 6a–e) and phospholipids (Fig. 3k and Extended Data Fig. 6f–i). Thus, our findings in cellular and reconstituted systems indicate that FSP1 acts as a CoQ10 oxidoreductase to prevent oxidative damage to neutral lipids stored in LDs.

PUFA supplementation generates PUFA-rich LDs that are prone to peroxidation

Analysis of FSP1 dependency in DepMap revealed a correlation between FSP1 essentiality and the amount of PUFA-containing TGs across 927 cancer cell lines (Fig. 4a,b). Although, FSP1 is not essential in most cell types, FSP1 is required for the viability of a subset of cell types with high PUFA TGs (Fig. 4a,b). PUFA-containing TG levels (for example, TG 56:6) correlate with the essentiality for many genes related to ferroptosis, including genes involved in glutathione synthesis, selenoprotein biosynthesis, fatty-acid metabolism and antioxidant defence (for example, GPX4 and FSP1/AIFM2) (Fig. 4c). These data indicate a correlation between PUFA-containing TGs and ferroptosis sensitivity, which may reflect the overall cellular lipid unsaturation environment or a vulnerability to ferroptosis conferred by the unsaturation of TGs.

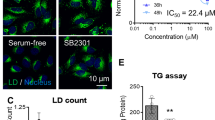

a, Mining the cancer dependency portal DepMap for correlations of FSP1 essentiality with metabolite abundance indicates FSP1 essentiality correlates with elevated levels of PUFA-containing TG and PUFA-containing PC lipids. q values represent Benjamini–Hochberg FDR-adjusted P values for the association between metabolite abundance and gene essentiality (DepMap portal). b, Example correlation of TG 56:6 with FSP1 essentiality across 927 cancer cell lines. Each dot represents one cell line. c, Association of relative abundance of TG 56:6 with gene essentiality indicates that anti-ferroptotic genes correlate highly with PUFA-TG levels. q values represent Benjamini–Hochberg FDR-adjusted P values for the association between metabolite abundance and gene essentiality (DepMap portal). d, LD quantification in U-2 OS cells treated with 200 µM oleate (FA 18:1) or arachidonate (FA 20:4) for 24 h in the presence and absence of DGAT1 (15 μM A-922500) and DGAT2 (10 μM PF-06424439) inhibitors. LDs were stained with BODIPY 493/503 and nuclei with Hoechst. e, LDs were imaged, and the LD area for each cell was quantified using Harmony data analysis software (Revvity). Each dot represents the LD area in an individual cell. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; NS, not significant. f, Quantification of TG levels via thin-layer chromatography. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; NS, not significant. g, Example of a thin-layer chromatogram used for the quantification in f. h, LC–MS/MS-based untargeted lipidomics comparing cells in the presence and absence of 200 µM FA 20:4 for 24 h. Lipid classes are coloured according to the legend. Data were autoscaled and log10-transformed. Thresholds for significant regulation are fold change > 2. Statistical significance was assessed by a two-sided t-test, and values were deemed significant if P < 0.05 (FDR-corrected). i, The same data as displayed in h. Significantly regulated lipids are coloured based on the presence or absence of FA20:4 metabolites. A lipid was deemed a putative FA20:4 metabolite when either of its fatty acids had more than 20 carbons with more than four double bonds. Data are autoscaled and log10-transformed. Thresholds for significant regulation are fold change > 2. Statistical significance was assessed by a two-sided t-test, and values were deemed significant if P < 0.05 (FDR-corrected). j, Bubble plot showing absolute quantities and the regulation of fatty acids in the non-polar lipid fraction extracted from U-2 OS cells treated with 200 µM FA20:4 for 24 h. For quantification, lipid extracts were separated into a non-polar lipid fraction using solid-phase extraction, and esterified fatty acids were transmethylated and quantified using GC–FID. k, Mol% of arachidonate (FA20:4 (n–6)) in non-polar and polar lipid fractions. Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; NS, not significant. l, Mol% of adrenate (FA22:4 (n–6)) in non-polar and polar lipid fractions. Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; NS, not significant.

To explore the possibility that PUFA-rich TG confers ferroptosis sensitivity and represents a vulnerability to the loss of FSP1, we developed a cell-based system in which we generate high amounts of PUFA-rich TGs. We hypothesized that FSP1 inactivation in this background would preferentially lead to LD peroxidation. Incubation of U-2 OS cells with the MUFA oleate (FA 18:1) or the PUFA arachidonate (FA 20:4) induced comparable biosynthesis of TGs and LDs, which were both dependent on diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 and 2 (DGAT1/2) (Fig. 4d–f). Incubation with arachidonate altered the cellular lipid landscape, with the majority of changes being in the amounts of TG lipids (Fig. 4g,h and Extended Data Fig. 7). Analysis of TG lipid changes also revealed an overwhelming increase in TG lipids containing arachidonate or putative arachidonate elongation and desaturation products (Fig. 4i), which was dependent on DGAT1/2 (Extended Data Fig. 7). A small number of phospholipids were also upregulated under arachidonate-supplemented conditions, indicating that arachidonate was also incorporated into other membranes. The untargeted lipidomics approach utilized in this study does not provide quantitative information regarding fatty-acid quantities within different lipid classes, and only yields relative quantitative information for individual intact lipids. We thus extracted total lipids from cells, isolated non-polar lipids and polar lipids (Extended Data Fig. 7i,j), and used gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC–FID) to quantify the fatty-acid compositions (Fig. 4j–l and Extended Data Figs. 7k–n and 8). This analysis indicated an increase in arachidonate and adrenic acid (22:4)-containing non-polar lipids (Fig. 4j) in the treated samples relative to control, with very little change observed in the polar lipids (that is, phospholipids) (Extended Data Fig. 7n). Importantly, DGAT inhibition blocked the increase in arachidonate and adrenic acid in non-polar lipids, with little effect on the amount present in polar lipids (Fig. 4k,l). These data establish a cell-based system to generate intracellular LDs with high amounts of PUFA-containing TGs.

Inhibition of FSP1 in cells containing PUFA-TG-rich LDs induces LD-specific neutral lipid peroxidation

We hypothesized that the PUFA-rich TGs in arachidonate-treated cells would be peroxidation-prone and sensitive to the loss of FSP1 function. Indeed, untargeted lipidomics indicated that treatment with the FSP1 inhibitor FSEN1 reduced the highest abundant arachidonate-containing TGs, implying their consumption by lipid peroxidation (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 7o). Co-treatment with the radical-trapping antioxidant ferrostatin (Fer-1) reversed this decrease (Fig. 5a), indicating that the observed decrease in arachidonate-containing TGs following FSP1 inhibition is peroxidation-dependent. To test this possibility directly, we performed semi-targeted epilipidomics analysis. Treatment with the FSP1 inhibitor FSEN1 resulted in the accumulation of oxidized arachidonate-containing CE and TG lipids, which was blocked by co-treatment with Fer-1, indicating that oxidized TG and CE are generated by active lipid peroxidation (Fig. 5b). To exclude possible off-target effects of FSP1 inhibitors, we also performed a similar assay in FSP1 KO cells. FSP1 KO cells display heightened cell death sensitivity to arachidonate treatment, so a lower arachidonate concentration had to be used to induce a PUFA TG phenotype to maintain the viability of the FSP1 KO cells. Treatment of the FSP1 KO cells with 20 μM arachidonate induced a similar upregulation of TGs containing arachidonate and putative arachidonate metabolites that could be blocked with DGAT1/2 inhibitors (Extended Data Fig. 7c–h). Within this system, FSP1 KO similarly resulted in an accumulation of oxidized CE and TG lipids, which were suppressed by Fer-1 co-treatment (Fig. 5c). Having established that FSP1 inhibition results in the specific accumulation of oxidized TG and CE in cells with PUFA-TG-rich LDs, we next sought to identify the localization of this lipid peroxidation. Using the lipid peroxidation stain BODIPY-C11, we observed lipid peroxidation puncta that colocalized with the LD marker LipiBlue and were prevented by Fer-1 treatment (Fig. 5d,e).

a, Highest intense TG lipids in cells treated with 200 µM FA20:4 for 24 h in the presence or absence of the indicated compounds, as quantified by untargeted lipidomics. b, Semi-targeted epilipidomics analysis of non-polar lipids in WT U-2 OS cells. The cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 200 µM FA20:4 for 24 h. After 24 h, the cells were treated with the indicated compounds for 6 h (shortly before cell death set in) and collected. c, Semi-targeted epilipidomics analysis of non-polar lipids in control and FSP1 KO U-2 OS cells treated with 20 µM FA20:4 for 24 h in the presence or absence of the indicated compounds. d, U-2 OS cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 200 µM FA20:4 for 24 h and subsequently treated with the indicated compounds. LDs were visualized using LipiBlue, and lipid peroxidation was visualized with BODIPY-C11. e, Quantification of the signal densities of colocalized markers for LDs (LipiBlue signal) and lipid peroxidation (BODIPY-C11) was performed using ImageJ. Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 7. Data were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (two-sided), with adjustment for multiple comparisons. f, U-2 OS cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 200 µM FA20:4, followed by incubation with FSEN1, and the cells were collected at 6 h. Absolute quantification of oxidized fatty acids was performed by separating lipid extracts into polar and non-polar lipid fractions, followed by basic hydrolysis and targeted LC–MS/MS for absolute quantification of oxidized fatty acids. The oxidized fatty acids displayed were identified by hierarchical clustering (Extended Data Fig. 10a). HETE, hydroxy-eicosa-tetra-en-oic acid; DiHETE, dihydroxy-eicosa-tetra-en-oic acid; DiHETrE, dihydroxy-eicosa-tri-en-oic acid; HDoHE, hydroxy-docosa-hexa-en-oic acid; HEPE, hydroxy-eicosa-penta-en-oic acid; LTB, leukotriene B; PGE, prostaglandin E; IsoP, isoprostane. Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3. g,h, U-2 OS cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 200 µM FA 20:4 for 24 h, followed by incubation with FSEN for 3 h. Oxidized fatty acids in polar lipids (g) or non-polar lipids (h) were quantified as described in f. Data are autoscaled. Thresholds for significant regulation are fold change > 2. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided t-test, and values were deemed significant if P < 0.05 (FDR-corrected). i, U-2 OS cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 200 µM FA 20:4 for 24 h, followed by incubation with FSEN for 0, 1, 3 or 6 h. Oxidized fatty acids in polar or non-polar lipids were quantified as described in f. All HETE regioisomers were summed up and plotted over time. Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3.

Pro-ferroptotic conditions are thought to induce the formation of phospholipid hydroperoxides, alcohols and ketones in the plasma membrane, but the accumulating oxidation products during LD peroxidation are not known. Current non-targeted epilipidomics workflows are incapable of identifying the exact structure of the various types of lipid modification and cannot provide quantitative information about the absolute levels of oxidized lipids. Therefore, to identify the main oxidized neutral lipids generated as a result of the loss of FSP1-mediated LD quality control, we extracted lipids from cells, separated the neutral lipid and polar lipid fractions using solid-phase extraction, and released esterified oxidized fatty acids via base hydrolysis, ultimately using a targeted approach that allows for absolute quantification of oxidized fatty acids (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Hierarchical clustering identified a cluster of oxidized fatty acids that specifically enriches in the neutral lipid fraction of cells with PUFA-TG-rich LDs (Extended Data Fig. 9a,b). This cluster contained almost exclusively alcohol-containing polyunsaturated fatty acids and identified various regioisomers of arachidonate-based alcohols (that is, hydroxy-eicosatetraenoic acids, HETE, FA20:4<OH>, <OH> = hydroxyl modification) as the main species accumulating as a result of FSP1 inhibition (Fig. 5f). Univariate statistics in polar and non-polar lipid fractions collected at different time points after FSP1 inhibition showed that the accumulation of arachidonate-based alcohols occurs only in the non-polar lipid fraction up to 3 h post FSP1 inhibition, but can also be detected in the polar lipid fraction after that (Fig. 5g,h and Extended Data Fig. 9f,g). Arachidonate-based alcohols are only detected in the phospholipid-containing polar lipid fraction at around 6 h post FSP1 inhibition, shortly before cell death (Fig. 5i). Interestingly, although arachidonate-based hydroperoxides (that is hydroperoxyl-eicosatetraenoic acids, HpETE, FA20:4<OOH>, <OOH> = hydroperoxyl modification) were highly enriched in the non-polar fraction of cells even at baseline (Extended Data Fig. 9d), these lipids did not accumulate or decrease during the observed time frame (Extended Data Fig. 9e). Several scenarios may explain why lipid alcohols, but not hydroperoxides, accumulate following FSP1 inhibition. One possibility is the presence of an enzymatic peroxidase system on LDs that selectively reduces lipid hydroperoxides to alcohols. Alternatively, the alkaline hydrolysis used during sample preparation may degrade hydroperoxides into alcohols, ketones, and epoxides38. This is further complicated by the lack of isotopically labelled internal standards for hydroperoxides, making their stability difficult to assess. It is also possible that the peroxidation environment in LDs inherently favours the formation of alcohols and other stable products. It remains unclear whether the observed alcohol accumulation reflects a biological process or an experimental artefact. These data indicate that PUFA-containing neutral lipids are highly reliant on FSP1 to prevent their peroxidation and that neutral lipid alcohols (and potentially other oxidized lipid derivatives that were not targetable with our approach) are the accumulating species driving LD peroxidation-mediated cell death.

FSP1-mediated neutral lipid quality control prevents LD-initiated ferroptosis

Our cellular system provides a controlled model to investigate the cellular consequences of neutral lipid peroxidation. Arachidonate treatment was well tolerated by control cells, with minimal cell death observed at concentrations up to 200 µM (Fig. 6a). In contrast, FSP1 KO cells, and cells treated with FSEN1, exhibited heightened sensitivity to arachidonate, with cell death occurring at concentrations as low as 25 µM and substantial cell death observed at 200 µM (Fig. 6a,b and Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). This arachidonate-induced cell death in FSP1 KO cells was reversed by co-treatment with Fer-1 (Fig. 6a). Notably, although treatment with the monounsaturated fatty acid oleate increased LDs similar to arachidonate treatment (Fig. 4d–f), it did not induce appreciable cell death and there were no substantial differences between control and FSP1 KO cells (Fig. 6c). These findings identify a cell death that is induced by the peroxidation of PUFA-rich LDs, even in the absence of targeting the GSH-GPX4 pathway, highlighting the critical role of FSP1 in protecting cells from ferroptosis by maintaining neutral lipid quality control.

a–c, Cell death sensitivity to arachidonate (FA20:4) (a,b) or oleate (FA18:1) (c) treatment, assessed by time-resolved fluorescence microscopy (IncuCyte) with SYTOX Green over the course of 24 h. The number of SYTOX Green-positive objects per image equals the number of dead cells and is normalized to cell area per image expressed as confluency. sg+, SYTOX green-positive objects. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3). d–g, Cell death quantified for 200 µM FA20:4 after 24 h in the presence of FSP1 inhibitor (‘FSEN1’ indicates co-treatment with 5 μM FSEN1), DGAT1/2 inhibitors (co-treatment with 15 μM A-922500 and 10 μM PF-06424439), acyl-CoA synthetase inhibitor (‘triacsin C’ indicates co-treatment with 1 μg ml−1 triacsin C) or TG lipolysis inhibitor (‘ATGLi’ indicates co-treatment with 10 μM NG-497). Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; NS, not significant). h, Expression levels of FSP1 in human tissues. Data are derived from the Human Protein Atlas. i, Absolute quantification of TG levels in Huh7 cells through thin-layer chromatogram densitometry. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3. j, LD peroxidation-initiated ferroptosis in Huh7 cells by the exogenous addition of 200 µM FA20:4 after 24 h in the presence of FSP1 inhibitor (‘FSEN1’ indicates co-treatment with 5 μM FSEN1), DGATi (co-treatment with 15 μM A-922500 and 10 μM PF-06424439), radical-trapping antioxidant (‘Fer-1’ indicates co-treatment with 2 µM Fer-1). Data are presented as mean ± s.d., n = 3. Data were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (two-sided), with adjustment for multiple comparisons. k, Schematic depicting the proposed mechanism of LD protection by FSP1.

To investigate the importance of FSP1 activity and localization, we utilized our panel of cell lines expressing various FSP1 constructs. Expression of WT FSP1 strongly suppressed arachidonate-induced cell death in FSP1 KO cells, whereas this protective effect was abolished by the catalytically inactive E156A mutation (Fig. 6d). The LD-targeted FSP1 construct partially mitigated arachidonate-induced cell death in FSP1 KO cells, although not as effectively as WT FSP1, which localizes to multiple cellular compartments (Fig. 6d). The suppression of cell death by FSP1 was reversed by co-treatment with the FSP1 inhibitor FSEN1 (Fig. 6d), emphasizing the importance of FSP1 catalytic activity in protecting cells under these conditions. Inhibitors of acyl-CoA synthetases (for example, triacsin C) and DGAT1/2 effectively prevented arachidonate-induced cell death (Fig. 6e,f and Extended Data Fig. 10c,d), indicating that the cytotoxic effects of arachidonate in FSP1 KO cells are dependent on its activation and incorporation into TGs. Adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) inhibition increased LDs (Extended Data Fig. 10e,f), but did not prevent arachidonate-induced ferroptosis and slightly enhanced death in FSP1 KO cells (Fig. 6g and Extended Data Fig. 10c). Importantly, in contrast to the established radical-trapping antioxidant Fer-1, the utilized DGAT1/2 inhibitors and the human ATGL inhibitor (NG-497) had no radical-trapping antioxidant activity, supporting an on-target mechanism of action (Extended Data Fig. 10g). We noted that the mouse ATGL inhibitor atglistatin exhibited some radical-trapping antioxidant activity (Extended Data Fig. 10g). Although we did not use this inhibitor in our studies, we wanted to share the data as a cautionary note for the field.

FSP1 transcript levels are highest in LD-rich tissues such as adipose and liver, but considerable levels are also found in the kidney, lung and brain (Fig. 6h). Treatment with arachidonate resulted in increased TG levels in hepatoma (Huh7), lung adenocarcinoma (A549) and clear cell renal cell carcinoma (Caki-1) cells, but did not lead to considerable TG accumulation in a microglial cell line (HMC3) (Fig. 6i and Extended Data Fig. 6j,m,p). Strikingly, Huh7 cells (a liver hepatoma cell line) strongly relied on FSP1-mediated LD quality control, as inhibition of FSP1 under arachidonate treatment resulted in high rates of cell death at arachidonate concentrations as low as 50 µM, which was completely rescued by co-treatment with DGAT1/2 inhibitors (Fig. 6j). Other tested cell lines displayed cell death that was partially rescued by DGAT1/2 inhibition (A549, Caki-1), whereas the cell death observed in HMC3, a cell line that did not exhibit TG induction, was not rescued by DGAT1/2 inhibition. Thus, there is a cell type specificity that is dependent on the biogenesis of PUFA-rich LDs. Together, these results highlight the pivotal role of FSP1 in preventing ferroptosis induced by the accumulation of oxidatively damaged TGs in LDs, and its essentiality as a homeostatic mechanism for cell survival.

Discussion

In this Article we have identifed FSP1 and CoQ10 as mediators of the first LD-specific lipid quality-control pathway (Fig. 6h), which prevents neutral lipid peroxidation and the initiation of ferroptosis from LDs. Remarkably, oxidized neutral lipid build-up and ferroptosis following FSP1 inhibition occur without GPX4 loss, revealing contexts where FSP1 is the primary suppressor. This expands the paradigm that FSP1 prevents peroxidation at multiple membranes, each representing distinct ferroptosis vulnerabilities.

LD-localized FSP1 reduces CoQ10 to generate local antioxidants that prevent neutral lipid peroxidation. CoQ10 often functions as a co-antioxidant with α-tocopherol, quenching tocopheroxyl radicals generated following the action of α-tocopherol as a radical-trapping antioxidant. However, LDs, which we find to lack detectable α-tocopherol or vitamin K in the conditions analysed in this study, appear to represent a context in which CoQ10 acts directly as the major radical scavenger. Other lipophilic antioxidants may contribute in specific tissues. How CoQ10 traffics to LDs remains an open question.

TG peroxidation may occur at packing defects in the LD monolayer39,40, which could expose TGs to reactive species, such as hydroxyl radicals and iron. Additionally, it is possible that oxidative damage initiates in the phospholipids of the LD monolayer and propagates inward to TG molecules in the LD core. The accumulation of oxidized neutral lipids probably impacts the structural and functional properties of LDs. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest that PUFA peroxidation within TG molecules increases their polarity, leading them to migrate from the neutral lipid core to the periphery of the LD, with the oxygen atoms protruding from between the LD phospholipid headgroups41. Structural changes resulting from oxidized fatty acids protruding between phospholipid headgroups would be expected to disrupt LD phospholipid packing, which is known to play important roles in LD protein targeting and association1,4. LDs would not be expected to rupture in the traditional manner of other organelles, because their lumen is made of neutral lipids rather than an aqueous compartment, however, the increased exposure of the hydrophobic oil core to the aqueous cytosol would probably disrupt LD morphology, alter protein association with LDs, and potentially facilitate the propagation of lipid peroxidation within LDs by enabling Fenton-type reactions with iron.

Our findings indicate that, in addition to the ER and lysosomes23,42,43,44, ferroptosis can also be triggered from LDs. LD-initiated ferroptosis required high PUFA-TG content and impaired FSP1 function. DGAT inhibitors, which block TG synthesis and LD biogenesis, effectively prevented ferroptosis in this context, underscoring the critical role of TGs and LDs in initiating ferroptosis under these conditions. Oxidation of LDs may contribute to ferroptosis under other conditions, such as ferroptosis induced by co-treatment with imidazole ketone erastin and the oxidized form of vitamin C13. Truncated forms and hydroxyl derivatives of TGs have been observed in dendritic cells in cancer and hypoxic trophoblast cells41,45,46, although their importance remains to be determined. The mechanisms by which lipid peroxidation propagates from intracellular organelles such as LDs to the plasma membrane remains unclear, but lipolysis is not required, as ATGL inhibition had no effect. It is possible that exposed TG peroxides at the LD surface could propagate oxidative damage by promoting iron oxidation, or LD phospholipid peroxides could be transferred to other membranes at membrane contact sites. The ER’s connection with LDs is notable, as LDs can grow through Ostwald ripening, a process in which the ER acts as a conduit for TG trafficking that enables neutral lipid exchange between LDs47. This suggests a potential pathway for the transmission of lipid peroxidation from LD neutral lipids to ER phospholipids, which could then spread through vesicular trafficking or phospholipid transfer at membrane contact sites.

The role of FSP1 in LD quality control has broad physiological and pathological implications. LDs are central in adipose and liver metabolism, and FSP1 is strongly expressed in brown adipose tissue48. LDs also accumulate under various pathological conditions. For instance, neurons efflux fatty acids (possibly lipid peroxides) for sequestration within astrocytic LDs as a protective mechanism49,50,51,52,53,54. Similarly, ferroptosis has been linked to liver diseases characterized by the accumulation of PUFA-containing TGs and LDs, such as metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and metabolic-associated steatohepatitis (MASH)55,56,57. These contexts underscore the potential biomedical importance of LD quality control in preventing ferroptosis-related damage.

In summary, we show that LD-localized FSP1 prevents neutral lipid oxidation and LD-initiated ferroptosis. LDs can be protective by sequestering PUFAs, but in the absence of FSP1, they become vulnerable sites of lipid peroxidation. These findings establish a unifying framework for LD lipid quality control and ferroptosis, highlighting the need for further study in physiology and disease.

Methods

LC–MS-based lipidomics and epilipidomics

Materials used for LC–MS were water (Fisher Scientific, W6-4), acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific, A955-4), 2-propanol (Supelco, 1.02781.4000), ammonium formate (Sigma-Aldrich, 70221-25G-F) and formic acid (Fisher Scientific, A117-50). Solvents for lipid extraction were tert-butyl methyl ether (Sigma-Aldrich, 34875) and methanol (Fisher Scientific, A456), spiked with 0.1% (wt/vol) 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (Sigma-Aldrich, B1378). The lipid internal standard mixture was SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Mass Spec Standard (Avanti Research, 330707).

Lipid extraction for lipidomics and epilipidomics

Confluent culture plates (10 cm or 6 cm in diameter) were washed once with PBS and then scraped into 1 ml of ice-cold PBS. The cells were pelleted at 3,000g for 5 min at 4 C, the supernatant was removed, and the cell pellets were stored at −80 °C. Before extraction, the cell pellets were thawed at room temperature for 3 min and suspended in 50 µl of PBS. Internal standards (3 µl of SPLASH LIPIDOMIX per sample) dissolved in methanol were added directly to each cell suspension, then lipids were extracted by adding 1250 µl of tert-butyl methyl ether and 375 µl of methanol. The mixture was incubated on an orbital mixer for 1 h at room temperature (on a revolver shaker, 32 r.p.m.). To induce phase separation, 315 µl of water was added, and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature (on a revolver shaker, 32 r.p.m.). The samples were centrifuged at 15,000g at room temperature for 3 min, then the upper organic phase was collected and subsequently dried in vacuo (in an Eppendorf concentrator 5301).

Liquid chromatography

Dried lipid extracts were reconstituted in 150 µl of chloroform/methanol (2:1, vol/vol), and 20 µl of each extract was aliquoted in high-performance LC (HPLC) vials containing glass inserts. Pooled quality-control samples were generated by mixing equal volumes of each lipid extract followed by aliquotation in 20-µl aliquots. Aliquoted extracts and pooled quality controls were dried in vacuo (in an Eppendorf concentrator 5301) and redissolved in 20 µl of isopropanol for injection.

Lipids were separated by reversed-phase LC on a Vanquish Core system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an Accucore C30 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm, 150 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific). They were separated by gradient elution with solvent A (acetonitrile/water, 1:1, vol/vol) and B (isopropanol/acetonitrile/water, 85:10:5, vol/vol) both containing 5 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid. Separation was performed at 50 °C at a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1 using the following gradient: 0–15 min, 25–86% B (curve 5); 15–21 min, 86–100% B (curve 5); 21–32 min, 100% B isocratic; 32–32.1 min, 100–25% B (curve 5); followed by 6 min re-equilibration at 25% B.

Mass spectrometry

The reversed-phase LC set-up was coupled online to a Q Exactive Plus Hybrid Quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a heated electrospray ionization (HESI) probe. Mass spectra were acquired in positive and negative modes with the following ESI parameters: sheath gas, 40 l min−1; auxiliary gas, 10 l min−1; sweep gas, 1 l min−1; spray voltage, (+)3.5 kV (positive ion mode); (−)3.2 kV (negative ion mode); capillary temperature, 250 °C; S-lens RF level, 35; auxiliary gas heater temperature, 370 °C.

Data acquisition for lipid identification was performed in pooled quality-control samples by acquiring data in data-dependent acquisition mode (DDA). The DDA parameters featured a survey scan resolution of 140,000 (at m/z 200), AGC target of 1e6, maximum injection time of 100 ms in a scan range of m/z 240–1,200. Data-dependent MS/MS scans were acquired with a resolution of 17,500, AGC target of 1e5, maximum injection time of 60 ms, isolation window of 1.2 m/z and stepped normalized collision energies of 10, 20 and 30. A data-dependent MS2 was triggered (loop count of 15) when an AGC target of 2e2 was reached followed by a dynamic exclusion for 10 s. All isotopes and charge states >1 were excluded. All data were acquired in profile mode.

For deep lipidome profiling, iterative exclusion was performed using the IE omics R package58. This package generates a list for already fragmented precursors from a prior DDA run to be excluded from subsequent DDA runs, ensuring a higher number of unique MS/MS spectra for deep lipidome profiling. After the initial DDA analysis of a pooled quality-control sample, the pooled quality control was measured two more times, but excluding all previously fragmentated precursor ions. The samples were analysed both in positive and negative ion modes. The parameters for generating exclusion lists from previous runs were as follows: RT window of 0.3; noiseCount of 15; MZWindow of 0.02 and MaxRT of 36 min.

Data for lipid quantification in individual samples were acquired in full MS mode with the following parameters: scan resolution of 140,000 (at m/z 200), AGC target of 1e6 and maximum injection time of 100 ms in a scan range of m/z 240–1,200.

Lipid identification and quantification

Lipostar (version 2.0, Molecular Discovery), equipped with an in house-enerated structure database built in LipoStarDB manager, was used. This database features fatty acids with no information on double-bond regio- or stereoisomerism and covers glycerolipid, glycerophospholipid, sphingolipid and sterol ester lipid classes. The raw files were imported directly with Sample MS Signal Filter Signal Threshold = 1,000 for MS and Sample MS/MS Signal Filter Signal Threshold = 10. Automatic peak picking was performed with m/z tolerance = 5 ppm, chromatography filtering threshold = 0.97, MS filtering threshold = 0.97 and signal filtering threshold = 0. Peaks smoothing was performed using the Savitzky–Golay smoothing algorithm with window size = 3, degree = 2 and multi-pass iterations = 3. Isotopes were clustered using m/z tolerance = 5 ppm, RT tolerance = 0.25 min, abundance Dev = 40% and max charge = 1. Peak alignment between samples used m/z tolerance = 5 ppm and RT tolerance = 0.25 min. A gap filler with RT tolerance = 0.05 min and signal filtering threshold = 0 with an anti-spike filter was applied.

For lipid identification, an MS/MS-only filter was applied to keep only features with MS/MS spectra for identification. Triacylgylcerols, diacylglycerols and steryl esters were identified as [M + NH4]+ adducts. Lysophosphatidylcholines lysophosphatidylethanolamines, and acyl-, ether- and vinyl ether-PE, phosphatidylserines, phosphatidylinositols, ceramides and sphingomyelins were analysed as [M + H]+ adducts. Acyl-, ether- and vinyl ethers were identified as [M−H]− adducts59. The following parameters were used for lipid identification: 5-ppm precursor ion mass tolerance and 20-ppm product ion mass tolerance. Automatic approval was performed to keep structures with a quality of 3–4 stars. Identifications were refined using manual curation and Kendrick mass defect analysis, and lipids that did not follow linear Kendrick mass defect–retention time correlations were excluded as false positives.

Quantification was performed by peak integration of the extracted ion chromatograms of single lipid adducts. Peak integration was manually curated and adjusted. Identified lipids were normalized to peak areas of added internal standards to decrease analytical variation, and eventually normalized to the protein concentrations of cell pellets after lipid extraction.

Statistical analysis of lipidomics data

MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://new.metaboanalyst.ca/home.xhtml) was used for statistical analysis and data transformation. Raw lipidomics data were imported into the ‘Statistical analysis [one factor]’ analysis pipeline. Data were transformed by ‘log transformation (base 10)’ and scaled by ‘auto scaling’ for statistical analysis. The transformed data and calculated statistics were exported as .csv files and plotted in GraphPad Prism 10.2.2 (GraphPad Software).

Comprehensive epilipidomics (oxidized lipid analysis) for analysis of FSP1 mutants

Prediction of sample-specific oxidized lipidome data-dependent acquisition

For the semi-targeted identification of oxidized lipids from cell extracts we followed a protocol as published previously57. To narrow down the number of potential lipid peroxidation products, we chose a subset of lipids for in silico oxidation. This lipid subset consisted of the top ten lipids with the highest intensity of phosphatidylcholine (PC), plasmalogen phosphatidylcholine (P-PC), alkyl ether phosphatidylcholine (O-PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), plasmalogen phosphatidylethanolamine (P-PE) and alkyl ether phosphatidylethanolamine (O-PE) and the top 20 lipids with the highest intensity of TG and CE lipid classes identified in each FSP1 mutant cell lipidome. We also incorporated the top ten lipids whose intensity correlates positively with sensitivity to cell death induced by RSL3 in each FSP1 mutant cell line. This led to a target list for the in silico oxidation of 176 lipids in total, represented by 77 phospholipids and 99 non-polar lipids.

In silico oxidation on this subset of rationally selected lipids was performed with LPPtiger234,35 utilizing the following parameters: max modification site = 2, max total O = 3, max OH = 2, max keto = 1, max OOH = 1, max epoxy = 0. The predicted epilpidome was refined by the unmodified lipid list generated in the step described above. An inclusion list was generated featuring the [M+Na]+ adducts of these entries, as the generated fragments of sodiated oxidized lipid ions are most informative for oxidized lipid identification.

Liquid chromatography

Pooled quality-control samples were dissolved in 20 µl of isopropanol for injection. The lipids were separated by reversed-phase LC on a Vanquish Horizon system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an Accucore C30 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm, 150 Å; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Lipids were separated by gradient elution with solvent A (acetonitrile/water, 1:1, vol/vol) and B (isopropanol/acetonitrile/water, 85:10:5, vol/vol) both containing 5 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid. Separation was performed at 50 °C with a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1 using the following gradient: 0–20 min, 10–80% B (curve 5); 20–24 min, 80–95% B (curve 5); 24–27 min, 95–100% B (curve 5); 27–32 min, 100% B isocratic; 32–32.1 min, 100–10% B (curve 5); followed by 7.9 min re-equilibration at 10% B.

Data-dependent acquisition settings to target the in silico oxidized epilipidome

The reversed-phase LC set-up was coupled online to an Orbitrap Exploris 240 Hybrid Quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a HESI probe. Mass spectra were acquired in positive and negative modes with the following ESI parameters: sheath gas, 40 arbitrary units (arb); auxiliary gas, 10 arb; sweep gas, 1 arb; spray voltage, (+)3.5 kV (positive ion mode); (–)2.5 kV (negative ion mode); ion transfer tube temperature, 300 °C; S-lens RF level, 35; vaporizer temperature, 370 °C. EASY-IC was set to run start.

Data acquisition for oxidized lipid identification was performed in quality-control samples by acquiring data in the data-dependent acquisition mode (DDA) with an inclusion list of predicted oxidized lipids. DDA parameters featured a survey scan resolution of 60,000 (at m/z 200), AGC target of 1e6, maximum injection time auto in a scan range of m/z 500–980 in negative ion mode (0–22 min) and m/z 480–1,200 in positive ion mode (22–40 min). Data-dependent MS/MS scans were acquired with a resolution of 60,000, normalized AGC target of 100%, maximum injection time of 200 ms, number of dependent scans, 6; isolation window, 1.5 m/z; first fixed mass, m/z 100; microscans, 2; normalized higher energy collision induced dissociation (HCD) collision energies, 22, 32, 43% in negative ion mode and 32, 43, 54% in positive ion mode. Dynamic exclusion was set to exclude precursors that were fragmented five times within 6 s were excluded from fragmentation for 5 s with a mass tolerance of ±5 ppm. All isotopes and charge states >1 were excluded. All data were acquired in profile mode.

Identification of oxidized lipids from the data-dependent acquisition dataset

MS/MS scans containing informative fragments were extracted using LPPtiger35 in lipid identification mode. The .raw files were converted to .mzML using MSConvertGUI from ProteoWizard 3.0.913460. The .mzML files were uploaded to LPPtiger2, and MS/MS spectra containing oxidized lipid candidates were identified with the following settings: MS1 tolerance = 5 ppm, MSMS tolerance = 20 ppm, precursor intensity = 100, precursor mz window = m/z 480–1,100, Selection window = m/z 1.2 with a score filter > 60, isotope score > 80, rank score > 40 and considering peaks with intensity >1%.

To remove false-positive MS/MS candidates and improve identification confidence, the spectra were filtered manually, and MS/MS candidates that did not contain an ‘oxidized fatty acid specific fragment’ were removed. For oxTG and oxCE,n, ‘oxidized fatty acid specific fragment’ was defined as an [M + Na]+ or [M + H]+ adduct of an intact oxidized fatty acid (for example [FA18:2<OOH>+Na]+) or an oxidized fatty-acid fragment that after fragmentation retained at least one oxygen atom (for example, [FA18:2<OOH–H2O+H]+). MS/MS candidates containing fragments originating from oxidized fatty acids that do not retain additional oxygen atoms after fragmentation were removed (such as acid (for example, [FA18:2<OH>–H2O+H]+), as these spectra cannot be used to confidently determine the presence of a fatty acid-specific modification. For oxPC and oxPE, an oxidized fatty acid fragment was defined as an [M−H]− adduct of an intact oxidized fatty acid (for example, [FA18:2<OOH>–H]−) or an oxidized fatty-acid fragment that after fragmentation retained at least one oxygen atom (for example, [FA18:2<OOH>–H2O–H]−). MS/MS candidates containing fragments originating from oxidized fatty acids that do not retain additional oxygen atoms after fragmentation were removed (such as acid (for example, [FA18:2<OH>–H2O–H]−) as these spectra cannot be used to confidently determine the presence of a fatty acid specific modification. Isomeric species were removed to result in a final list covering 82 m/z values representing oxidized lipids.

Relative quantification of oxidized lipids by parallel reaction monitoring

Lipids were dissolved in isopropanol and separated and ionized as described above for data-dependent acquisition.

Optimized data acquisition settings for the parallel reaction monitoring were as follows: isolation window = 1.5 m/z, resolution = 15,000, maximum IT = 100 ms, microscans = 1, featuring a single collision energy. Transitions were quantified with Skyline59 utilizing a 5-ppm mass accuracy on a centroided fragment signal. Confidence of quantification was improved by observing transitions of [M + Na]+ → [oxFA + Na]+ or [oxFA + H]+ depending on the targeted lipid.

The signal intensities of each oxidized lipid were normalized to isotopically labelled standards of their respective lipid class in the SPLASH LIPIDOMIX standard (Avanti Research, 330707) and finally normalized to the protein concentration in each cell pellet previously determined by a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, PI23227).

Statistical analysis of epilipidomics data

MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://new.metaboanalyst.ca/home.xhtml) was used for statistical analysis and data transformation. Raw lipidomics data were imported into the ‘Statistical Analysis [one factor]’ analysis pipeline. The data were transformed by ‘Log transformation (base 10)’ and scaled by ‘auto scaling’ for statistical analysis. The transformed data and calculated statistics were exported as .csv files and plotted in GraphPad Prism 10.2.2 (GraphPad Software).

Epilipidomics of oxidized non-polar lipids in the PUFA-induced LD damage model

Prediction of sample-specific oxidized lipidome data-dependent acquisition

For the untargeted identification of oxidized lipids from cell extracts, we followed a previously published protocol59. To narrow down the number of potential lipid peroxidation products, we chose a subset of lipids for in silico oxidation. This lipid subset consisted of the top 15 lipids with the highest intensity of TG and CE lipid classes in either U-2 OS WT cells treated with 200 µM arachidonic acid or U-2 OS TetR and U-2 OS FSP1 KO cells treated with 20 µM arachidonic acid. We also incorporated the lipids that were substantially downregulated (that is, log2(fold change) > 2, P < 0.05) by FSP1 inhibition via FSEN1 treatment in the arachidonic acid-treated conditions. This led to a target list for the in silico oxidation of 95 lipids, in total represented by 18 CE and 77 TG lipids.

In silico oxidation on this subset of rationally selected lipids was performed with LPPtiger35 with the following parameters: max modification site = 2, max total O = 3, max OH = 2, max keto = 1, max OOH = 1 and max epoxy = 0. The predicted epilipidome was refined by the unmodified lipid list generated in the step described above. An inclusion list was generated featuring the [M + Na]+ adducts of these entries, as the generated fragments of sodiated oxidized lipid ions are most informative for oxidized lipid identification.

Liquid chromatography

Dried lipid extracts were reconstituted in 60 µl of chloroform/methanol (2:1, vol/vol) and 10 µl of each extract was aliquoted in HPLC vials containing glass inserts. Quality-control samples were generated by mixing equal volumes of each lipid extract followed by aliquotation in 10-µl aliquots. Aliquoted extracts were dried in vacuo (in an Eppendorf concentrator 5301) and redissolved in 20 µl of isopropanol for injection, then 5 µl were loaded onto the column.

The lipids were separated by reversed-phase LC on a Vanquish Core system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an Accucore C30 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm, 150 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The lipids were separated by gradient elution with solvents A (acetonitrile/water, 1:1, vol/vol) and B (isopropanol/acetonitrile/water, 85:10:5, vol/vol), both containing 5 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid. Separation was performed at 50 °C with a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1 using the following gradient: 0–15 min, 25–86% B (curve 5); 15–21 min, 86–100% B (curve 5); 21–32 min, 100% B isocratic; 32–32.1 min, 100–25% B (curve 5); followed by 6 min re-equilibration at 25% B.

Data-dependent acquisition settings to target the in silico oxidized epilipidome

The reversed-phase LC set-up was coupled online to a QExactive Plus Hybrid Quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a HESI probe. Mass spectra were acquired in positive and negative modes with the following ESI parameters: sheath gas, 40 l min−1; auxiliary gas, 10 l min−1; sweep gas, 1 l min−1; spray voltage, (+)3.5 kV (positive ion mode; capillary temperature, 250 °C; S-lens RF level, 35; auxiliary gas heater temperature, 370 °C.

Data acquisition for oxidized lipid identification was performed in quality-control samples by acquiring data in data-dependent acquisition mode (DDA). The DDA parameters featured a survey scan resolution of 140,000 (at m/z 200), AGC target of 1e6 and a maximum injection time of 100 ms in a scan range of m/z 500–1,200. Data-dependent MS/MS scans were acquired with a resolution of 17,500, AGC target of 1e6, maximum injection time of 200 ms, loop count of 7, isolation window of 1.2 m/z, fixed fist mass of 100 and normalized collision energy of 30. A data-dependent MS/MS was triggered when an AGC target of 1e1 was reached followed by a dynamic exclusion for 3 s. All isotopes and charge states >1 were excluded. All data were acquired in profile mode.

Identification of oxidized lipids from the data-dependent acquisition dataset

MS/MS scans containing informative fragments were extracted using LPPtiger35 in lipid identification mode. The .raw files were converted to .mzML using MSConvertGUI from ProteoWizard 3.0.913460. The .mzML files were uploaded to LPPtiger, and MS/MS spectra containing oxidized lipid candidates were identified with the following settings: MS1 tolerance = 5 ppm, MSMS tolerance = 20 ppm, precursor intensity = 100, precursor mz window = m/z 500–1,100, selection window = m/z 1.2 with a score filter > 60, isotope score > 80, rank score > 40 and considering peaks with intensity >1%.

To remove false-positive MS/MS candidates and improve identification confidence, the spectra were filtered manually, and MS/MS candidates that did not contain an oxidized fatty acid specific fragment were removed. An oxidized fatty acid specific fragment was defined as an [M + Na]+ or [M + H]+ adduct of an intact oxidized fatty acid (for example, [FA18:2<OOH> + Na]+) or an oxidized fatty acid fragment that at least retained one oxygen atom after fragmentation acid (for example, [FA18:2<OOH> – H2O + H]+). MS/MS candidates containing fragments originating from oxidized fatty acids that did not retain additional oxygen atoms after fragmentation were removed (such as acid (for example, [FA18:2<OH> – H2O + H]+), as these spectra cannot be used to confidently determine the presence of a fatty acid specific modification. All entries were sorted, and isomeric species were removed to result in a final inclusion list covering 16 m/z values representing oxidized lipids.

Relative quantification of oxidized lipids by parallel reaction monitoring

The lipids were dissolved in isopropanol and separated and ionized as described above for data-dependent acquisition.

The confidence of quantification was improved by observing transitions of [M + Na]+ → [oxFA + Na]+ or [oxFA + H]+ depending on the targeted lipid.

Optimized data acquisition settings for the parallel reaction monitoring were as follows: isolation width = 1.2 m/z, resolution = 17,500, maximum IT = 200 ms, microscans = 1, maximum IT = 200 ms featuring normalized collision energy = 30. Transitions were quantified with Skyline61 utilizing a 5-ppm mass accuracy on a centroided fragment signal. The signal intensities of each oxidized lipid were normalized to the isotopically labelled standards of their respective lipid class in the SPLASH LIPIDOMIX standard (Avanti Research, 330707).

Statistical analysis of epilipidomics data

MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://new.metaboanalyst.ca/home.xhtml) was used for statistical analysis and data transformation. Raw lipidomics data were imported into the ‘Statistical Analysis [one factor]’ analysis pipeline. The data were transformed by log transformation (base 10) and scaled by auto scaling for statistical analysis. The transformed data and calculated statistics were exported as .csv files and plotted in GraphPad Prism 10.2.2 (GraphPad Software).

Relative quantification of redox active lipids

WT U-2 OS cells were treated with 200 µM oleate (Nu-Chek Prep) and 0.1% fatty acid=free BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, A3803). LDs were extracted as described below in the section ‘LD enrichment and flotation’.

Lipophilic radical-trapping antioxidants were extracted by the addition of 600 µl of methanol (Fisher Scientific, A456) + 0.1% (vol/vol) hydrochloric acid (Fisher Scientific, A144) and 600 µl hexane (Fisher Scientific, H302) to a 600-µl LD fraction. The samples were vortexed vigorously for 60 s at room temperature and centrifuged at 2,000g for 3 min at 4 °C. The upper hexane fraction was collected and transferred to a HPLC glass vial. The upper hexane phase was dried in vacuo (in a vacuum concentrator 5301, Eppendorf). For LC–MS analysis, the dried fraction was dissolved in 50 µl of isopropanol (Supelco, 1.02781.4000), and 10 µl were injected for analysis. Coenzyme Q10, Q9, Q8, vitamin K1 (phylloquinone), vitamin K2 (menaquinone-4) and (+)-α-tocopherol were analysed by parallel reaction monitoring.

The lipids were separated by reversed-phase LC on a Vanquish Core system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an Accucore C30 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm, 150 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Separation was carried out by gradient elution with solvent A (acetonitrile/water, 1:1, vol/vol) and B (isopropanol/acetonitrile/water, 85:10:5, vol/vol) both containing 5 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid. Separation was performed at 50 °C with a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1 using the following gradient: 0–15 min, 25–86% B (curve 5); 15–21 min, 86–100% B (curve 5); 21–32 min, 100% B isocratic; 32–32.1 min, 100–25% B (curve 5); followed by 6 min re-equilibration at 25% B.

The reversed-phase LC set-up was coupled online to a Q Exactive Plus Hybrid Quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a HESI probe. Mass spectra were acquired in positive and negative modes with the following ESI parameters: sheath gas, 40 l min−1; auxiliary gas, 10 l min−1; sweep gas, 1 l min−1; spray voltage, (+)3.5 kV (positive ion mode); (−)3.2 kV (negative ion mode); capillary temperature, 250 °C; S-lens RF level, 35; and auxiliary gas heater temperature, 370 °C.

Lipids were analysed by parallel reaction monitoring, and individual ions were isolated with an isolation window of 1.2 m/z. MS/MS spectra were acquired with an AGC target of 1e6 with a maxIT of 100 ms and a resolution of 17,500. The quantification of each lipid was optimized, and the final settings were CoQ10 (collision energy, 15; retention time, 22.4 min; precursor formula, C59H90O4; adduct, [M + NH4]+; product formula, C10H12O4; product m/z, 197.0808; product adduct, [M + H]+); CoQ10H2 (collision energy, 15; retention time, 22.1 min; precursor formula, C59H92O4; adduct, [M + NH4]+; product formula, C10H12O4; product m/z, 197.0808; product adduct, [M + H]+); CoQ9 (collision energy, 15; retention time, 21.4 min; precursor formula, C54H82O4; adduct, [M + NH4]+; product formula, C10H12O4; product m/z, 197.0808; product adduct, [M + H]+); CoQ9H2 (collision energy, 15; retention time, 21.1 min; precursor formula, C54H84O4; adduct, [M + NH4]+; product formula, C10H12O4; product m/z, 197.0808; product adduct, [M + H]+); CoQ8 (collision energy, 15; retention time, 20.2 min; precursor formula, C49H74O4; adduct, [M + NH4]+; product formula, C10H12O4; product m/z, 197.0808; product adduct, [M + H]+); vitamin K1 (collision energy, 25; retention time, 17.5 min; precursor formula, C31H46O2; adduct, [M + H]+; product formula, C12H10O2; product m/z, 187.0754; product adduct, [M + H]+); menaquinone-4 (collision energy, 25; retention time, 14.8 min; precursor formula, C31H40O2; adduct, [M + H]+; product formula, C12H10O2; product m/z, 187.0754; product adduct, [M + H]+); α-tocopherol (collision energy, 20; retention time, 13.2 min; precursor formula, C29H50O2; adduct, [M + H]+; product formula, C10H12O2; product m/z: 165.091; product adduct, [M + H]+).

The relative quantification of each analyte was performed by quantification of the transitions in the table above in Skyline61 utilizing a 5-ppm mass accuracy on a centroided signal.

Cellular and in vitro assays

Cell culture

U-2 OS parental cells, Caki-1 cells and HMC3 cells were obtained from the UC Berkeley Cell Culture Facility. Huh7 cells were a kind gift from H. Ramage (University of Pennsylvania). U-2 OS, Caki-1 and Huh7 cells were cultured in DMEM with L-glutamine and without sodium pyruvate (Corning, 10-017-CM) and containing 10% fetal bovine serum (GemCell, 100-500). All cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. A549 cells were a kind gift from S. Dixon’s laboratory (Stanford University) and were cultured in RPMI with L-glutamine (Corning, 10-040-CM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GemCell, 100-500). HMC3 cells were cultured in EMEM (ATCC, 30-2003) with l-glutamine supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GemCell, 100-500).

FSP1 mutant expression was induced in U-2 OS cells with 10 ng ml−1 doxocycline (Sigma-Aldrich, D9891) for 48 h before the respective experiments.

Immunodetection (western blotting) of FSP1

Cells were cultured in 10-cm culture dishes. Before collection, the cells were washed with 5 ml of PBS and scraped into 1 ml of PBS. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 3,000g for 3 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was discarded. For lysis, the cells were resuspended in 100 µl of RIPA buffer (Pierce, 89901) with 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce, A32955) and sonicated by probe sonication for 30 s with 15% amplitude on a Branson 150 sonicator equipped with a sonication probe (Branson Ultrasonics, 4C15). Protein concentration was determined via a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, PI23227).

For gel electrophoresis, the cell lysates were diluted with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 10–15 µg of protein were loaded on a 4–20% gradient gel (Bio-Rad, 4561094) and separated at 90 V for 10 min followed by 250 V for 20 min. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, 1704158) using the TransblotTurbo system (Bio-Rad) at mixed molecular-weight settings. The membranes were blocked with 5% milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich, P7949) for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. Primary antibodies were diluted 1:1,000 in 5% BSA (Fisher Scientific, BP9703) in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, and the blots were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Next, blots were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:25,000 in 5% BSA in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. After washing three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, the blots were imaged on a Li-Cor imaging system (Odyssey).

Cell death analysis

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates (Corning, 3904) at 15% confluency in 10 ng ml−1 doxycycline hyclate (Sigma-Aldrich, D9891) for 48 h to induce FSP1 expression or 30% confluency for 24 h in WT cells before the respective experiments. LDs were induced by treating cells with 200 µM of the respective fatty acid (Nu-Chek Prep) and 0.1% fatty acid-free BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, A3803).