Abstract

Dating the tree of Fungi has been challenging due to a paucity of fossil calibrations and high taxonomic diversity of the group. Here we reconstructed and dated a comprehensive phylogeny comprising 110 fungal species, utilizing 225 phylogenetic markers and accounting for across-site compositional heterogeneity in amino acid sequences. To address uncertainties in fungal dating, we sampled chronograms from four relaxed molecular clock analyses, each integrating distinct sets of calibrations and relative time-order constraints. The first analysis used a core set of 27 calibrations alongside 17 relative constraints derived from fungi-to-fungi horizontal gene transfer events. Three further analyses extended this core set with additional timing information identified in our reevaluation of the evolution of pectin-specific enzymes in Fungi. Our timetree, integrating analytic uncertainties, suggests older ages for crown Fungi (1,401–896 Ma) than recently reported, providing a minimum age for ancient interactions involving fungi and the algal ancestors of embryophytes in terrestrial ecosystems (1,253–797 Ma). This supports a protracted gap between the onset of these interactions and the rise of modern land plants. Altogether, our study provides a refined timescale for fungal diversification and a temporal framework for future investigations into early interactions involving fungi and the algal ancestors of embryophytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The fungal kingdom is composed of an extensive diversity of organisms that evolved to inhabit nearly all of Earth’s ecosystems1. Fungi are involved in key ecological interactions that were probably important during the early evolution of complex life2. Among other hypotheses, it has been proposed that fungi and plants colonized land as mutualistic partners, paving the way for the radiation of macroscopic life in terrestrial habitats3,4.

Fungi exhibit diverse morphologies5, lifestyles6 and complexity levels7, the best known of which are filamentous and mushroom-forming fungi and yeasts, most of which belong to the subkingdom Dikarya. Fungi, however, also contain several ‘early-diverging’ non-Dikarya phyla, including Zoopagomycota, Mucoromycota, Olpidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota and Chytridiomycota1. While less studied than Dikarya, these phyla and their ancestors experienced some of the most important events in fungal evolution, including the origin of multicellular hyphae8, terrestrialization(s) and the loss(es) of a flagellum9,10, and the transition from a phagotrophic feeding strategy to osmotrophy11. Osmotrophy unites Dikarya with the early-diverging non-Dikarya phyla12, and we use it as a defining feature of Fungi that leaves Aphelida, Rozellida, Microsporidia and Nucleariidea as the closest relatives of Fungi in the tree of life12,13,14 (Fig. 1).

We defined Fungi as the clade including the coloured groups, as they are characterized by an absorptive/filamentous specialized osmotrophic lifestyle that distinguishes them from their closest relatives in the tree of life (non-coloured groups). Silhouettes are from PhyloPic (see Supplementary Information section 6 for credit and license details).

The evolution of non-Dikarya phyla has been the subject of intense study. As a result, their phylogenetic relationships are relatively well known9,12,13,14,15,16, with the exception of a few hard-to-resolve relationships, which seem to be sensitive to methodological choices17. Aside from the phylogenetic relationships, establishing a dated phylogeny of Fungi is crucial to understand when major clades originated or how interactions between fungi and other lineages shaped the biosphere.

Main challenges in dating the ToF

The reconstruction of a dated tree of Fungi (ToF) is confronted by four major challenges (Challenges A–D; Fig. 2a). From a taxonomic standpoint, the availability of genomic data has historically been skewed towards Dikarya18, leaving some early-diverging phyla underrepresented in genomic databases (Challenge A, although substantial progress has been achieved thanks to initiatives such as the ‘1000 Fungal Genomes Project’19). In addition, dating a broad and diverse phylogeny constitutes a difficult computational endeavour. While researchers have developed tools to accelerate molecular dating analyses for large phylogenetic datasets20, these often use simplified models that cannot account for complex protein sequence properties, such as amino acid site compositional heterogeneity21,22 (Challenge B). Furthermore, deep phylogenetic relationships are not yet fully resolved17, including: (1) whether Chytridiomycota12 or Blastocladiomycota15 is the sister group to the rest of the fungi; (2) the position of the flagellated group Olpidiomycota9, which is critical to understanding whether terrestrial fungal groups originated from one or multiple terrestrialization events; and (3) the placement of the genus Basidiobolus, which has been variably positioned near Mucoromycota16 or Zoopagomycota15 (Challenge C). Finally, fungal fossils are scarce, especially for unicellular groups that diverged before Dikarya. This issue is compounded by previous studies largely relying on a narrow set of calibration points, such as Paleopyrenomycites, with limited exploration of additional fossils23,24 (Challenge D). Aiming to address these challenges, we implemented a comprehensive methodological workflow that integrates cutting-edge phylogenetic and molecular dating techniques (Fig. 2b).

a, Main challenges. b, A summary of the methodological workflow executed to deal with these challenges and produce the ‘Default’ set of chronograms. See the main text and Methods for further details.

Results

A broad and diverse taxon sampling

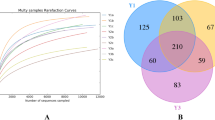

To achieve a phylogenetically broad and taxonomically diverse ToF (addressing Challenge A), we utilized publicly available data from the 1000 Fungal Genomes Project19 to gather a genomic taxon sampling of 110 fungal species, including 43 from non-Dikarya fungal groups, plus an additional 43 non-fungal taxa, enabling us to contextualize the ToF within a broader diversity of eukaryotes (see taxon sampling in Fig. 3). We combined three distinct strategies to collect a total of 889 phylogenetic protein markers from the downloaded genomic data (see ‘Candidate marker set’ section in Methods). We then selected 225 markers based on optimal metrics screening (see ‘Filtering the marker set’ section in Methods), and the selected markers were aligned and concatenated into a supermatrix comprising 95,968 protein amino acid sites and 153 taxa. This supermatrix provided the molecular data to reconstruct a dated ToF by means of a two-step process (Fig. 2b): (1) inference of the ToF (the phylogenetic relationships between the species) and (2) the datation of the ToF.

Four chronogram sets were produced: ‘Default’ (based on a core set of 24 calibration points and 17 relative constraints), and three other chronogram sets that incorporated calibrations and relative constraints based on plausible scenarios related to the evolutionary history of pectin and pectin specific-enzymes (PSE) in Fungi (see Fig. 4). To be conservative and to account for node age uncertainty, the branch lengths of this figure correspond to mean divergence times from ‘Default’, while node age bars show the oldest and the lowest among the 95% high posterior density (HPD) credibility interval values retrieved from the four chronogram sets reconstructed. Consensus chronograms obtained separately from each of these four analyses are available in the extended data Fig.s 3, 6, 7 and 8. Supplementary Fig. 2 includes cumulative probability distributions for node ages. Supplementary Data includes more detailed information on node age probabilities and pairwise node age orderings to complement the summary HPD data displayed in this figure. Silhouettes are from PhyloPic (see Supplementary Information section 6 for credit and license details).

Dealing with topological uncertainties

For the first step of the process, reconstructing the topology of the ToF, modelling amino acid site compositional heterogeneity (the fact that protein sites evolve under non-homogeneous compositional constraints) has been shown to be crucial in solving deep phylogenetic relationships22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Among the available implemented models to handle this, the CAT model33 has proven to be useful to solve complex scenarios of long branch attraction21,28,29,30,32,33,34. However, CAT is computationally costly and only available in a Bayesian framework (Phylobayes software)35,36. Among the alternative approaches explored (Methods), we used the CAT-PMSF pipeline22 (where PMSF is posterior mean site frequencies), which allows inference of amino acid preferences at each site without the computational overhead of a full Bayesian inference across tree topologies. We also used a complementary species tree reconstruction analysis using the software ASTRAL37 to better capture topological uncertainty in the ToF. The CAT-PMSF tree (Extended Data Fig. 1) but not the ASTRAL tree (Extended Data Fig. 2) shows B. meristosporus grouped with Zoopagomycota, as expected based on its taxonomic classification38. Meanwhile, Chytridiomycota branched as a sister group to the rest of Fungi in both trees, consistent with the most recently published ToFs that also used site-heterogeneous models12,13,16,17. Finally, the placement of the flagellated fungi O. bornovanus was unresolved, also in the ASTRAL topology.

To clarify the position of O. bornovanus in relation to the non-flagellated terrestrial fungi, we tested five alternative topologies using two different approaches. Two of these topologies were rejected on the basis of approximately unbiased (AU) tests39 applied to the concatenated matrix (P < 0.05), while a further two were dismissed using a phylogenetic reconciliation approach40, which analysed 38,837 gene families (see Methods for details). Only the topology in which Olpidiomycota branched as the sister group to the terrestrial fungal clade composed by Dikarya + Mucoromycota + Zoopagomycota was not rejected. We thus consider the recovered monophyly of the non-flagellated terrestrial fungi as the most likely topology. This agrees with recent findings9 and supports the hypothesis that these groups share a common ancestor that transitioned from an aquatic to a terrestrial environment, potentially losing the flagellum as a result of this shift9,10.

A core set of calibrations and HGT-derived relative constraints

After having inferred a topology for the ToF (CAT + PMSF topology, with O. bornovanus positioned as sister to terrestrial fungal groups; Fig. 3), the next step was to date it. As a source of timing information to date the tree (Challenge D), we first established, as described below, a core set of calibrations as well as relative constraints derived from horizontal gene transfer (HGT) data.

Compiling a broad and reliable set of calibrations is critical for relaxed molecular clock analyses providing local checks on rate variation41. To this end, we derived an initial set of 17 fossil-based calibration points for the fungal clade following the best practice principles42 (calibrations 1–4 and 6–18; Supplementary Information section 1). In Metazoa and Embryophyta, maximum age calibrations (maxima) can be established on the basis of absence data, qualified by taphonomic outgroup controls that demonstrate that in-group representatives would be preserved if they existed; this is possible because most lineages of animals and plants have a structured and predictable fossil record43. By contrast, fungal vegetative structures fossilize very poorly and their fossil record is, for the most part, unstructured and unpredictable. We could, however, transfer the maximum constraint on the age of Embryophyta to three fungal nodes based on their phylogenetic and ecological association with the land plant crown clade. First, we transferred the maximum age proposed for crown Embryophyta44 to crown Endogonales45 (Jimgerdemannia flammicorona + Endogone sp. clade, calibration 5) and to crown Glomeromycotina46 (Gigaspora sp. + Glomus cerebriforme clade, calibration 7B). This was based on the observation that representatives of both groups are involved in complex and ancient symbiotic associations with embryophytes, suggesting that they probably originated after the emergence of Embryophyta (see Supplementary Information section 1 for details). We also used the maximum age calibration for crown Embryophyta to the Cadophora sp. + Tolypocladium inflatum clade within Dikarya (calibration 20) on the basis of a HGT event from within Embryophyta to this clade (Supplementary Information section 2). This HGT event was identified on the basis of a systematic and conservative screening of potential HGT cases involving Embryophyta and Fungi (Methods). Apart from the mentioned calibrations, all of which calibrate nodes within Fungi, we also included calibration 19 (a maximum for the root of the tree), and calibrations 21–24, which calibrate other eukaryotic nodes (Supplementary Information section 1). Overall, this set includes 27 calibrations for 24 nodes (3 nodes have both maximum and minimum age calibrations, 19 of the calibrated nodes are from Fungi).

Beyond these 24 calibration points, this core set incorporated 17 relative constraints inferred from a second HGT screen, this time exploring HGTs involving distantly related fungal groups. This allowed us to identify 19 fungi-to-fungi HGTs (Supplementary Information section 3) from which we inferred 17 relative time-order constraints based on non-repetitive HGT information. Relative time-order constraints establish older and younger relationships between nodes in the tree based on the principle that the parent node of the lineage identified as the HGT donor must be older than the descendant node of the lineage identified as the receptor of the HGT event47,48,49.

Accelerated chronogram sampling based on sophisticated methods

Once we inferred the topology of the ToF and obtained the core set of timing information described above, we used Mcmcdate50,51 to date the tree. This tool performs relaxed molecular clock analyses from a precomputed set of phylogram data (trees with branch lengths representing substitutions per site), from which Mcmcdate takes less than a day on a standard laptop to complete the analysis. This allowed us to overcome the computational constraints of large-scale dating (Challenge B) and also to perform preliminary analyses to evaluate the impact of methodological variables (see details in Supplementary Information section 5). For example, we evaluated whether modelling across-site compositional heterogeneity (for example, with CAT), which is more computationally expensive than the typically used site homogeneous models, also has an impact for branch length estimation as it has for the inference of the topology21,28,29,30,32,33,34. We found that, at least for the employed methodology, using CAT to sample input phylogram data for Mcmcdate had a substantial impact on the sampled node ages, more than, for example, exchanging the autocorrelated for the uncorrelated rates clock model (Supplementary Information section 5-Fig. 1). In this regard, posterior predictive simulations showed that using CAT for phylogram sampling led to a better modelling of the input alignment than not using it (Supplementary Information section 5-Table 1). We also observed that CAT led to chronogram sets with lower variance in node age (Supplementary Information section 5-Fig. 3). Altogether, we decided to use phylograms sampled under the CAT model for the definitive dating analyses. In addition, to provide information that could be valuable for future studies, we assessed whether the number of sites in the input alignment has an impact on branch length estimation. We found that, despite some increase in node age variance (Supplementary Information section 5-Fig. 3), 10,000 randomly subsampled sites from the full phylogenetic marker set (which is one order of magnitude larger) would have been sufficient to get consistent node ages, whereas 5,000 sites would not have been (Supplementary Information 5-Figs. 1, 5 and 6). Finally, progressively subsampling sites from either the slowest- or fastest-evolving markers had less impact on the estimated ages than changing the clock model or omitting the use of CAT (Supplementary Information section 5-Fig. 1).

We continued the exploratory analyses described above, next testing the impact of the core set of 27 calibrations and 17 relative constraints on the resulting ages. We found that the ages retrieved by using this core set (‘Default’ analysis; Extended Data Fig. 3) were substantially older than the ages retrieved from an alternative analysis done by using only the least possible calibration information (‘Only root calibration’ analysis; Extended Data Fig. 4a). This trend probably stems from the influence of the 21 minimum age calibrations (minima; Extended Data Fig. 5a,b), whereas the maximum age calibrations (maxima) in this core set had a more localised effect on the retrieved ages (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d). Given the uncertainty on the informativity of the maxima available in the core set, in the next sections we aimed to explore the incorporation of additional timing information to finally produce a timetree of Fungi that accounts for this uncertainty (Fig. 3).

Reevaluating the pectin-related maximum age calibration

A strategy to mitigate the lack of maxima extracted from palaeontological evidence is to retrieve calibration information from molecular data. In particular, Chang et al. (2015)52 and Chang et al. (2021)9 imposed a soft maxima of 750 million years ago (Ma) and 850 Ma, respectively, on the last common ancestor of Chytridiomycota + Dikarya (LCA-Chytridiomycota + Dikarya, which in our phylogeny corresponds to the last common ancestor of Fungi, LCA-Fungi). Chang et al. (2015)52 imposed this calibration based on inference of an ancestral expansion in LCA-Chytridiomycota + Dikarya of enzymes specifically involved in pectin degradation (pectin-specific enzymes, PSE). Pectins are matrix polysaccharides of the cell walls of plants and are involved in controlling growth, cell wall porosity and expansion, among other important functions53,54. Rather than being restricted to Embryophyta, some streptophyte algal relatives of land plants also have pectins related to those found in embryophytes54,55,56. Based on the increase of PSE content found in LCA-Chytridiomycota + Dikarya, Chang et al. (2015)52 hypothesized that this early fungus should have been younger than the last common ancestor of streptophytes with pectin cell walls. Accordingly, they imposed a maximum (750 Ma) for LCA-Chytridiomycota + Dikarya based on published age inferences for Streptophyta. Chang et al. (2021)9 applied this same topological calibration but constrained it to 850 Ma.

Given the impact this maximum age calibration has for the timescale of fungal evolution, we revisited the evolutionary history of PSE in Fungi, previously done by Chang et al. (2015)52, in the light of a more comprehensive genome dataset. For this, we reconstructed ancestral gene content of PSE families, including methods that account for HGT. As a justification of modelling HGT when reconstructing ancestral gene content for PSE, a manual screening of the PSE phylogenies revealed 17 instances of HGT (Supplementary Information section 4). When we used HGT-aware methods for ancestral gene content reconstruction, we did not recover PSE presence in LCA-Chytridiomycota+Dikarya (Supplementary Information section 4). Instead, the oldest fungal ancestor for which all the reconstruction methods detected PSE content was the last common ancestor of Mucoromycota + Dikarya (LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya). Given the lack of support by the HGT-aware method for PSE presence in LCA-Chytridiomycota + Dikarya, we refrained from using the pectin-related maximum age calibration as used in previous studies. Instead, we performed a series of additional datation analyses, each incorporating distinct sets of timing information inferred from our evolutionary reconstruction of PSE evolution in Fungi. For that, we took advantage of Mcmcdate implementing relative constraints in the relaxed molecular clock analysis.

Exploring a relative constraint involving streptophytes and early terrestrial fungi

The first relative constraint tested, implemented in the ‘PSE-constraint A’ condition (Fig. 4), covers the possibility that LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya could have been younger than Klebsormidium + Embryophyta, the node subtending the branch in which classic pectin/pectin sensu stricto probably originated. By classic pectin, we refer to pectin cell wall fractions with similar polysaccharide profiles to the pectin cell wall fractions of embryophytes, based on homogalacturonan with calcium-bridged α-(1→4)-GalA residues as main pectic fraction, and which have been shown to be hydrolysed in endopolygalacturonase-mediated digestion assays57,58. The relative constraint is justified on our inference of ancestral gene content of PSE families in LCA-Mucoromoycota + Dikarya that, based on recent works, seem to digest only the pectin cell wall fractions of those streptophyte groups that diverged later than Klebsormidium from the lineage path leading to Embryophyta (see ‘A PSE-related relative age constraint’ in Supplementary Information section 4 for a detailed justification of this relative constraint).

All nodes correspond to the last common ancestors of the named groups (see Fig. 3 for a phylogenetic context). ‘Default’ analysis was done based on the core set of 24 calibration points and 17 relative constraints (see ‘A core set of calibrations and HGT-derived relative constraints’ section). For information on ‘PSE-constraint A’ and ‘PSE-constraint A + calib’, see ‘Exploring a relative constraint involving streptophytes and early terrestrial fungi’ section. For information on ‘PSE-constraints B + C’, see ‘Exploring relative constraints involving embryophytes with macroscopic terrestrial fungi’ section.

We expected ‘PSE-constraint A’ to be informative as, in the initial dating scheme (‘Default’ in Fig. 4), LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya (1,138 Ma; Extended Data Fig. 3) was found to be substantially older than the Klebsormidium + Embryophyta node (686 Ma). Accordingly, incorporating this relative constraint resulted in a substantially older age for Klebsormidium + Embryophyta (1,129 Ma; Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 6). By contrast, the age of LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya remained almost identical (1,107 Ma), as well as the age of the rest of Fungi (Extended Data Fig. 4b).

We next tested ‘PSE-constraint A + calib’, aiming to cover the possibility that our taxon sampling and calibration set, conceived to reconstruct and date the ToF, may be limited to provide accurate age estimates for the Streptophyta side of the tree. The ‘PSE-constraint A + calib’ condition extends ‘PSE-constraint A’ by incorporating a soft maximum age calibration for the Klebsormidium + Embryophyta node based on age estimates provided for this node in the bibliography. Among recently published timescaled phylogenies including a broad sampling of Streptophyta, Harris et al. (2022)50 incorporated a rich set of timing information, including novel fossil calibrations and a relative constraint. As a conservative soft maximum calibration for Klebsormidium + Embryophyta, we set the upper bound of the credibility interval reported by Harris et al. (2022)50 for the Arabidopsis + Klebsormidium clade (927 Ma according to the supplementary data provided in this study). ‘PSE-constraint A + calib’ (Extended Data Fig. 7) resulted in younger ages for LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya and LCA-Fungi (Fig. 4), as well as for more internal nodes of the tree (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Younger ages than in ‘PSE-constraint A’ were also estimated for the Klebsormidium + Embryophyta, consistent with the implemented calibration, as well as for the parent node of this node, LCA-Streptophyta (Fig. 3).

Exploring relative constraints involving embryophytes with macroscopic terrestrial fungi

Finally, we also tested the ‘PSE-constraints B + C’ condition. This covers the possibility that the main expansions of PSE content in terrestrial Fungi may have occurred in response to the emergence of Embryophyta as an ecologically dominant streptophyte lineage in terrestrial settings. From the early PSE content inherited from LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya (Fig. 5a), two main PSE expansions occurred in terrestrial fungi. On the one hand, a gradual and longstanding expansion trajectory started in Yarrowia lipolytica + Cadophora sp. (Supplementary Table 5), the parent node of LCA-Pezizomycotina. Pezizomycotina is one of the two major groups of terrestrial macroscopic Fungi. On the other hand, a second expansion occurred in concomitance to the emergence of Agaricomycotina, the second major clade of macroscopic terrestrial fungi. Within Agaricomycotina, the expansion of PSE content started in Calocera viscosa + Mycena galopus (Supplementary Table 6), the descendant node of LCA-Agaricomycotina. Both Agaricomycotina and Pezizomycotina are well represented by species with lifestyles related to embryophytes, either as symbionts (for example, mycorrhiza and lichens), plant pathogens or decomposers of plant material59,60. It is plausible that PSE expansions in both groups may correspond to gene content adaptations to the establishment of embryophytes as an ecologically relevant lineage in terrestrial settings. Based on that, the ‘PSE-constraints B + C’ condition incorporates two soft relative constraints forcing the nodes in which the onset of both PSE expansions were detected (Y. lipolytica + Cadophora sp. and C. viscosa + M. galopus) to be younger than LCA-Embryophyta. ‘PSE-constraints B + C’ (Extended Data Fig. 8) led to younger ages in Fungi than in the ‘Default’ condition, not only for Agaricomycotina and Pezizomycotina but also for the most internal nodes including LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya and LCA-Fungi (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 4d). However, in contrast to ‘PSE-constraint A’ and ‘PSE-constraint A + calib’, the ages of the most internal nodes of Streptophyta (Klebsormidium + Embryophyta and LCA-Streptophyta) remained similar to the ‘Default’ condition (Fig. 4).

a, Expansion of PSE in the ancestral path to macroscopic terrestrial fungi. The right axis (dashed lines) shows the relative PSE copy number in the ancestral paths leading to Cadophora sp. (Pezizomycotina) and Mycena galopus (Agaricomycotina), the two species showing the largest PSE content in both groups of macroscopic fungi. See Methods for details on how PSE content per My was computed. The left axis shows the percentage of chronograms in which each fungal clade (non-dashed lines) is found to be older than a certain age. Plausible Streptophyta partners for terrestrial fungi over time are shown based on the 95% HPD CI values retrieved for the Streptophyta nodes as shown in b. b, The 95% HPD credible interval (CI) of sampled ages from the four chronogram sets obtained by relaxed molecular clock analyses based on distinct sets of calibrations and relative constraints (Fig. 4). The 95% HPD CI information was retrieved from Fig. 3. Klebsormidium + Embryophyta is the node subtending the branch in which classic pectin/pectin sensu stricto (pectin s.s.) probably originated (see ‘Exploring a relative constraint involving streptophytes and early terrestrial fungi’ section).

A timescale of fungal diversification

The ages retrieved by the ‘PSE-constraint A’, ‘PSE-constraint A + calib’ and ‘PSE-constraints B + C’ cover a series of plausible scenarios related to our evolutionary reconstruction of PSE evolution in Fungi. While the scenarios represented by each of these conditions are certainly hypothetical, we consider them plausible enough to extend the age ranges obtained in the ‘Default’ analysis (Extended Data Fig. 3) by incorporating the chronogram data sampled under the other three datation analyses (Extended Data Figs. 6–8). We present a timeline for fungal diversification based on our extended, conservative age estimates (Fig. 3). The eukaryotic supergroup Opisthokonta diverged into Holozoa (the clade containing animals) and Holomycota (the clade containing Fungi) between 1,767 Ma and 1,151 Ma. Within Holomycota, the lineage leading to Fungi separated from the lineage leading to Paraphelidium tribonemae (Aphelida)—a group of endobiotic, phagotrophic algae parasites—between 1,470 Ma and 945 Ma. The emergence of crown Fungi marked the first major divergence in extant fungal diversity, with the Chytridiomycota and the Blastocladiomycota + Sanchytriomycota clades branching off from the main fungal line between 1,401 Ma and 896 Ma and between 1,374 Ma and 877 Ma, respectively.

Within Chytridiomycota, Chytridiomycetes, characterized by coenocytic thallus and rhizoids, diverged between 1,222 Ma and 462 Ma from the lineage leading to Neocallimastigomycetes (Orpinomyces sp. + Anaeromyces robustus clade, 72–40 Ma, anaerobic symbionts found in ruminant digestive systems). Blastocladiomycota, a group of saprotrophs and aquatic parasites (1,106–591 Ma), diverged from the branch leading to Sanchytriomycota, a clade of chytrid-like parasites with amoeboid zoospores and reduced flagella (Amoeboradix gromovi + Sanchytrium tribonematis clade, 484–150 Ma), between 1,217 Ma and 705 Ma.

A subsequent divergence occurred between 1,303 Ma and 831 Ma, when Olpidiomycota, an obligate zoosporic endoparasite, split from the clade comprising non-flagellated terrestrial fungi—the Zoopagomycota + Mucoromycota + Dikarya clade. Within this clade, Zoopagomycota and Mucoromycota have largely overlapping age ranges (1,252–796 Ma and 1,213–678 Ma, respectively) and diversified before Dikarya (1,114–701 Ma). Zoopagomycota encompasses lineages with predominantly non-plant-related lifestyles, while Mucoromycota includes Glomeromycotina (Gigaspora sp. + Rhizophagus irregularis clade, 580–408 Ma) and Endogonales (Endogone sp. + Jimgerdemannia flammicorona clade, 340–76 Ma), both of which form complex symbiotic relationships with land plants.

From Dikarya, the most extensively studied fungal group, the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota clades originated between 940 Ma and 577 Ma and between 889 Ma and 550 Ma, respectively. These two groups exhibit considerable phenotypic diversity, spanning unicellular yeasts in Saccharomycotina (Yarrowia lipolytica + Saccharomyces cerevisiae clade, 643–347 Ma) and Wallemiomycotina (Wallemia mellicola + Basidioascus undulatus clade, 559–279 Ma), to complex multicellular fungi in Pezizomycotina (661–409 Ma) and Agaricomycotina (706–430 Ma).

Discussion

We applied a comprehensive methodological framework to address the challenges of reconstructing and dating the evolutionary history of Fungi, a deep eukaryotic lineage (Fig. 2). This approach enabled the reconstruction of a timetree of Fungi (Fig. 3), incorporating extensive taxon sampling of 153 taxa (110 fungi and 43 other eukaryotes), phylogenetic information from 225 protein markers and substitution models that account for site-specific amino acid compositional heterogeneity33,35. Site-heterogeneous models were used for both phylogeny inference and species tree dating. To overcome the computational bottleneck of dating with site-heterogeneous models, we utilized the Mcmcdate software50,51, which performs relaxed molecular clock analyses on precomputed phylograms (trees with branch lengths representing substitutions per site). Once phylograms are generated, sampling chronograms (trees with branch lengths expressing divergence times) takes less than one day on a standard laptop. This allowed us to benchmark distinct methodological variables. We found that, at least for our dataset and for our methodological workflow, sampling chronograms by accounting for site compositional heterogeneity had a larger impact than, for example, the choice of the molecular clock model used for the relaxed molecular clock analyses. We also concluded that 10,000 randomly subsampled amino acid sites would have been sufficient to produce consistent results with the ages obtained from the full phylogenetic marker set, which is of one order of magnitude larger. This offers a pathway to accelerate even more the chronogram sampling process without compromising accuracy. Finally, site-homogeneous models are much less computationally demanding than site-heterogeneous models, and as such, they allow reconstructing and dating very large phylogenies (for example, see alternative timetree with 662 species in Supplementary Fig. 1). However, site-homogeneous models can offer a poorer fit and a worse modelling of the amino acid diversity in the input alignment, as we observed for our 153-taxa dataset for which we could benchmark site-homogeneous versus site-heterogeneous models (Supplementary Information section 5-Table 1).

Our core set of timing information includes 27 absolute age calibrations (6 maxima—5 excluding the root calibration—and 21 minima for 24 calibrated nodes, including 19 nodes from Fungi). This is a substantial increase compared with previously published timetrees of Fungi (for example, 13 calibrated fungal nodes in Lutzoni et al. (2018)61 and 8 in Chang et al. (2019)62). Our core set of timing information also includes 17 relative time-order constraints informed by a conservative fungi-to-fungi HGT screening. These 17 relative constraints, reflecting speciation order between nodes, reduced node age uncertainty across the phylogeny (Supplementary Information section 5-Figs. 8 and 9). Regarding the core set of calibrations, sensitivity analyses confirmed the informativity of the 21 minima, which led to a generalized increase in node ages. By contrast, the five maxima did not have a global impact on the timescale, suggesting that these may not have been sufficiently informative. Given this uncertainty, we aimed to extend our analyses by incorporating additional timing information. Following Chang et al. (2015)52, we re-examined the evolutionary history of PSE with HGT considerations, resulting in three additional sets of calibrations and relative constraints (Fig. 4), each representing a plausible scenario related to PSE evolution in Fungi.

The age ranges shown in Fig. 3 integrate the uncertainties inherent in the four different sets of calibrations and relative constraints used (Fig. 4). Aggregating node age uncertainty leads to broader uncertainty ranges (Extended Data Fig. 9). Notwithstanding this, we emphasize the conservative age ranges in Fig. 3, as they illustrate the complexities of dating eukaryotic lineages with a limited fossil record, particularly compared with animals or plants (but see Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data for more specific information on node age probability distributions). Based on Fig. 3, we provided a timeline for fungal diversification (see ‘A timescale of fungal diversification’ section in the Results), starting from the split between the lineage leading to fungi and the lineage leading to animals (Opisthokonta, 1,767–1,152 Ma; for an alternative timescale more especially focused in the whole Opisthokonta supergroup, we refer to ref. 17, and for alternative timescales of Fungi, we refer to refs. 9,61).

How old are Fungi? The age range retrieved for crown Fungi (1,401–896 Ma; Fig. 3), as well as the age ranges reported by Chang et al. (2021)9 and Lutzoni et al. (2018)61 (~980–650 Ma and ~950–715 Ma, respectively, based on the figures shown in these studies), are compatible with the potential fungal identity of recently reported fossils dated to 1,010–890 Ma (ref. 63) and 810–715 Ma (ref. 64). However, our timescale is also compatible with older—although more uncertain—fungal fossils, such as the specimens described by Hermann and Podkovyrov65 (1,025–1,015 Ma) and, more generally, with the possibility that bona fide fungal fossils from the Mesoproterozoic (1.6–1.0 Ga) could be reported in future studies (LCA-Fungi is >1 Ga in 88.5% of our chronograms; Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data). It is important to clarify that the discussed fossils were not included among our calibrations because we considered their assignment to crown Fungi plausible but not unequivocal. At the same time, we acknowledge that temporal compatibility between fossil and clade ages is not in itself evidence of affinity.

Our results also have implications concerning ancient fungi–algae interactions preceding the emergence of crown embryophytes. Previously hypothesized based, for example, on comparative timescale information (for example, ref. 61), following ref. 52 (see ‘Reevaluating the pectin-related maximum age calibration’ and ‘Exploring a relative constraint involving streptophytes and early terrestrial fungi’ sections in the Results), our findings on PSE evolution and aggregated chronogram data (Fig. 5) provide evidence for such interactions and suggest a minimum age for early interactions involving ancestral streptophytes and Fungi (1,253–797 Ma, LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya), predating by hundreds of million years the emergence of modern land plants (LCA-Embryophyta, 612–431 Ma). This is supported by our inference of ancestral PSE content in LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya, indicating that this fungus presented specific enzymes to degrade pectin. Chang et al. (2015)52 inferred PSE content also in LCA-Chytridiomycota + Dikarya, an older fungal ancestor. However, we did not recover PSE content in this ancestor when HGT-aware methods were used.

Altogether, the reported timescale (Fig. 3) adds more weight to the reinterpretation of the Mesoproterozoic and early Neoproterozoic, not as a ‘boring billion’ (1.8–0.8 Ga)66, but as an important interval in which eukaryote lineages diversified67,68,69,70. This episode is not especially well documented by the fossil record, and the record that exists is challenging to interpret69,70. As such, it is important to use molecular approaches to see through the gaps in the fossil record. Concerning the emergence of macroscopic eukaryotes—such as plants, animals or some fungi—after the not so ‘boring billion’, attempts have been made to establish a causal link between the origin of complex multicellularity and Cryogenian Snowball Earth events71,72. Regarding Fungi, if the emergence of complex multicellularity in Pezizomycotina and Agaricomycotina roughly coincided with the last common ancestor of both groups, LCA-Agaricomycotina (706–430 Ma) and LCA-Pezizomycotina (660–409 Ma), then these could have originated either during or after the Cryogenian Snowball Earth events (~720 − 635 Ma (ref. 72)), but not before them.

LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya, an ancestral fungus in which we identified PSE content, is an early representative of the major clade of terrestrial fungal groups (Fig. 3). Given this, and given also that streptophyte algae share some adaptations found in embryophytes to terrestrial life73,74, we consider it plausible that early interactions involving LCA-Mucoromycota + Dikarya and streptophyte algae occurred in terrestrial settings or in freshwater–terrestrial interfaces, possibly in primitive microbial communities resembling modern biological soil crusts or microbial mats75. During the protracted gap between the onset of these interactions and the emergence of crown embryophytes, early fungi and streptophytes may have coexisted as mere ecosystem partners, or may have already been involved in complex symbiotic interactions3. Fossil evidence for such hypothetical interactions remains elusive (the oldest unequivocal fossils representing mycorrhizae and lichen associations are from ~400 Ma (refs. 76,77,78), already from the Embryophyta period). Further work is needed in characterising ecological interactions involving extant fungi and streptophyte algae79 to better understand how these two lineages may have interacted before the rise of embryophytes, and how important these interactions may have been for the terrestrialization process of both eukaryotic groups. To our knowledge, beyond co-occurrences80 (for example, streptophytes have been found in the microbiome of lichens, but never in the role of the main algal partner76), as well as some lineages of fungi and some fungal relatives being able to parasitise81,82 and to feed on streptophyte algae83, no complex symbiosis involving fungi and streptophyte algae has been reported in modern microbial interactions. Altogether, our study provides a refined timescale of the diversification process of Fungi, offering also a temporal framework for future investigations concerning early interactions involving fungi and the algal ancestors of embryophytes in terrestrial ecosystems.

Methods

Taxon sampling

We constructed a protein sequence dataset including 110 fungal species (+12 outgroup species, see below), hereafter referred to as original_dataset (Supplementary Table 1, this dataset was extended later to incorporate a total of 153 species; see ‘Incorporation of additional taxon sampling into the species tree’ section). These species were selected to maximize the most balanced possible representation of every major fungal group (detailed below) and also the inclusion of representatives from clades for which fossil data are less scarce. In particular, original_dataset includes 42 Basidiomycota, 25 Ascomycota, 15 Mucoromycota (including 3 Glomeromycotina), 9 Zoopagomycota, 1 Olpidiomycota, 12 Chytridiomycota and 6 Blastocladiomycota, including also 2 Sanchytriomycota species. In addition, 12 non-fungal species from the Amorphea division of eukaryotes were also included as outgroups for phylogeny rooting purposes (Supplementary Table 1). Outgroup selection was to a great extent based on the species included in one of the latest published ToFs at the time this project started13.

Candidate marker set

For the inference of the species tree, marker genes were selected from three different methodological sources: (1) we started grouping original_dataset sequences into clusters using MCL v.14-13784 with an inflation value of 2, using −log10-transformed E-values as a similarity metric. E-values were retrieved from an all-against-all alignment of all original_dataset sequences with BLASTP85 (v.2.10.1+) using the following parameters: [-evalue 1e-3 -soft_masking yes -max_target_seqs 1000]. From the resulting clusters, we initially selected as potential markers those that were single-copy—that is, clusters without duplicated sequences at the species level. We next allowed clusters to become single-copy after eliminating terminal duplications. For this, a preliminary alignment (MAFFT86 v.7.313-linsi) and gene tree reconstruction (FastTree87 2.1.11, phylogenetic model: WAG) were performed. We selected and eliminated terminal duplications only from those gene trees where all duplicated proteins of a species formed a monophyletic clade using a custom-made script88 (https://github.com/zsmerenyi/compaRe/blob/main/Terminaldupdet.zip. (2) We performed a hidden Markov model (HMM)-based search by running BUSCO89 v.3.0.2 on the fungal profiles (fungi_odb9) over our original_dataset. Only ‘Complete’ and ‘Fragmented’ proteins were considered. (3) Finally, we ran an HMM search on original_dataset using HMMER 3.3.290 and the HMM profiles from the Joint Genome Institute 1086 marker gene set62 as a query (https://github.com/1KFG/Phylogenomics_HMMs/tree/master/HMM/JGI_1086). For (3), we considered only the best matches for each species (ordered by E-value and full score), using the E-value cut-off <1 × 10−5 for the full alignment. Also, for each HMM query, we identified the most represented MCL clusters among the target sequences, and excluded from the target set all the original_dataset sequences grouped in other MCL clusters. Then, to prevent the inclusion of saturated markers, we removed those candidate markers from the three methodological sources showing average amino acid alignment distance ≥1.5 using the WAG model of the function dist.ml from the phangorn package91. Also, we eliminated candidates containing potential ancestral paralogues with the same method as in ref. 88. Finally, we also excluded clusters if (1) they were represented by <25 species and (2) if they included repeated sequences from other clusters (in such a case, we prioritized first the markers obtained from MCL clusters, and then those obtained from the Joint Genome Institute marker gene set over those obtained from the BUSCO dataset). This altogether led to a set of 839 markers representing a total of 261,382 amino acid sites (candidate market set). For each of these candidate markers, we aligned the corresponding sequences using MAFFT and trimmed the resulting alignments with trimAl92 1.2rev59 using the -gappyout option. A preliminary gene tree was constructed from each candidate marker using IQ-TREE93 v.1.6.12 (LG + G4 model, 1,000 optimized ultrafast bootstraps) to compute the metrics needed to select the definitive marker set (see below).

Filtering the marker set

Because we recovered more markers than needed for our target of approximately 100,000 amino acid sites, we discarded from the candidate set those markers that exhibited suboptimal metrics (low number of sites, low bootstrap values, high tip-to-root distance and high tip-to-root covariance94). In particular, we discarded candidate markers that met any of the following criteria: (1) a number of sites lower than that of 66% of the candidates, (2) UFBoot support values lower than those of 66% of the candidates, (3) tip-to-root distance metrics higher than those of 75% of the candidates, and (4) tip-to-root covariance metrics higher than those of 75% of the candidates. Moreover, we retained only those candidate markers found in at least ≥50% of Dikarya taxa, ≥50% of other fungal groups and ≥50% of outgroup sequences. This altogether led to a definitive set of 225 markers representing a total of 97,487 amino acid sites (definitive market set), which were concatenated into a sole file (Data/MSAs/original_concatenate.phylip).

Species tree inference and selecting the most supported topology

We performed a first inference of the species tree using the software IQ-TREE and the LG + F + G4 + C60 model, which allows modelling compositional and rate heterogeneity between sites in the alignment. This analysis took 6 days and 5.5 h on 48 central processing unit (CPU) threads of Intel Xeon 4116 @ 2.1 GHz CPUs. Using C60 provided a markedly better model fit (C60 + LG + G4 + F, Bayesian information criterion score 23,863,331) than site-homogenous alternatives (LG + G4 + F, Bayesian information criterion score 24,389,728), underscoring the importance of using site-heterogeneous models for supermatrix-based species tree inferences. While the resulting tree (Supplementary Fig. 3) from this first round of inference showed an overall reasonably congruent topology with recent publications in the bibliography (for example, refs. 13,16), three main potentially conflicting topologies were identified: (1) Blastocladiomycota being the first branch within Fungi instead of Chytridiomycota; (2) Basidiobolus meristosporus (Zoopagomycota) branching with Mucoromycota; and (3) Olpidium bornovanus (found to be the closest relatives of non-flagellated fungal groups in ref. 9) branching within a clade of non flagellated Fungi. Aiming to recover a more congruent topology, we used a more complex model such as the CAT + GTR + G4 model available in Phylobayes21,33. As running this complex model with our dataset would have been computationally impractical, we used the recently developed approach CAT-PMSF22. CAT-PMSF could be simplified as a two-step process. First, site-specific stationary distributions are sampled by running Phylobayes under the CAT + GTR + G4 using the LG + F + G4 + C60 topology as guide topology (the method has been proven to be robust to the chosen topology22). For this, we ran two Phylobayes chains for more than 20,000 generations each, and site-specific stationary distributions (amino acid exchangeabilities and site-state frequencies) were sampled after chain convergence assessment (burn-in 10,000). This analysis took 37 days on 240 CPU threads of Intel Xeon 4116 CPU @ 2.1 GHz for each chain. Then, we performed a species tree inference with IQ-TREE using the PMSF approach95, combining the sampled amino acid exchangeabilities and site-state frequencies with the G4 model (Extended Data Fig. 1). This analysis took 11 h using 16 CPU threads of Intel Xeon Silver 4116 CPU @ 2.1 GHz. To corroborate our choice of the CAT-PMSF over the LG + F + G4 + C60 topology, we conducted a model adequacy test as described by ref. 96. We simulated 100 parametric bootstraps using AliSim97 implemented in IQTree93 v.2.4.0 with the same model specifications used to infer the species trees and then comparing the across-sites amino acid diversity of the simulated samples with the original data. We measured a 18-fold lower Z score (4.95) for the CAT-PMSF model than for the LG + F + G4 + C60 (Z score −89.26), supporting our decision to use the topology inferred by CAT-PMSF in the downstream analysis. The scripts and input files for generating parametric bootstrap samples and calculating the Z scores are available in Data/Model_adequacy_tests.zip.

To clarify the position of Olpidium bornovanus (Obor), we performed two separate rounds of AU topology tests39 based on two alternative approaches. The first approach, the most standard one, consisted of running five rounds of the CAT + PMSF analysis but constraining each time the inference to a given topological hypothesis (1) Obor branching as sister group to Mucoromycota, (2) Obor branching as sister group to Mucoromycota + Dikarya, (3) Obor branching as sister group to Zoopagomycota, (4) Obor branching as sister group to Zoopagomycota + Dikarya and (5) Obor branching as sister group to Mucoromycota + Zoopagomycota + Dikarya (Supplementary Table 7). Topologies (1) and (4) were rejected with the AU test (AU-test P values 0.000751 and 4.47 × 10−118; Supplementary Table 7). We then submitted the three remaining topologies to the second approach, which consisted of running three runs of gene-tree species-tree reconciliation with the software ALE98, each run using one of the three surviving topologies as species tree, and always the same set of optimized ultrafast-bootstrap replicates sampled for each gene family (one gene family per MCL cluster). (To sample ultrafast-bootstrap replicates for each MCL cluster, we followed the same approach as we did to produce gene trees for the MCL clusters that were among the candidate marker set; see ‘Candidate marker set’ section above.) We retrieved the likelihood values from the uml_rec files produced by ALE for each gene family (a total of 38,824 likelihood values for each ALE run), and used the AU test to test whether some of the remaining topologies can be rejected. The logic for performing this test was the following. ALE reconciles every gene family with the species tree and outputs a likelihood value. A more realistic species tree can be expected to result in fewer discordances with gene trees, leading to improved likelihood values. For each of the three tested topologies, we had a total of 38,824 likelihood values. Analogously, each of these can be seen as if they were the likelihood values corresponding to alignment sites representing each of the three topologies to be tested. Based on AU-test results performed with CONSEL99 v.0.20, we could reject topologies (2) and (3) (AU-test P values 1.00 × 10−6 and 2.00 × 10−5; Supplementary Table 7), leaving topology (5) as the only non-rejected topology. We thus used the phylogenetic tree reconstructed during the constrained inference of topology (5) with the CAT-PMSF model as the topology from which to produce chronogram data.

Calibrations and HGT-derived relative time-order constraints

Justification of the node age calibrations used in this study can be found in Supplementary Information section 1. This section also includes a justification of the maximum age calibration inferred from a broad-scale exploration of the HGT events from Embryophyta to Fungi (see Supplementary Information section 2 for details on how this HGT exploration analysis was done). Regarding HGT-derived relative time node order constraints, the methodology and the HGT events based on which relative constraints were established are detailed in Supplementary Information section 3. The retrieved node ages are robust to the possibility that some relative constraint may have introduced erroneous relative node order information (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Reevaluating the evolutionary history of PSE in Fungi

To infer ancestral PSE presence in Fungi, which could have implications to calibrate the maximum age of Fungi52, we reevaluated the evolutionary history of PSE in Fungi. See Supplementary Information section 4 for details on these analyses.

Incorporation of additional taxon sampling into the species tree

The reconstruction of PSE evolution (Supplementary Information section 4) showed evidence of ancestral interactions involving Fungi and the algal ancestors of embryophytes. To further explore the codiversification of both groups, we incorporated ten additional taxa from the Streptophyta side of eukaryotes. We also incorporated 21 additional taxa from other eukaryotic groups for a broader representation of intermediate lineages branching between Fungi and Streptophyta (Supplementary Table 2). Given this expanded taxon sampling, our original species tree—used to guide the phylogram sampling process required for chronogram reconstruction (see below)—had to be extended to incorporate the phylogenetic relationships of the additional taxa, based on existing bibliographic references50,100,101 (Fig. 3). We also had to extend the concatenate alignment using the following strategy. (1) We built HMM profiles for each of the 225 definitive markers (those that were used to reconstruct the species tree with the original taxon sampling of 122 species). We used this set of HMM profiles to scan a concatenate of FASTA sequences for the 31 extended taxon sampling. Positive hits for each marker (candidate sequences to be incorporated) were considered for step 3. (2) We used Diamond102 v.2.0.14.152 [-e 1.0E-03 --more-sensitive --masking 1] to align that same FASTA concatenate against a large dataset including the original 122 set of species, as well as a large representation of non-eukaryotic taxa (to ensure the exclusion of potential prokaryote contaminant sequences). (3) We filtered the candidate sequences and incorporated only those for which the best Diamond hit corresponded to a member of the marker set being used. The candidate marker FASTA files were thus extended with the sequences from the 31 extended taxon sampling that passed this filter. (4) To generate the final concatenate alignment, the extended candidate markers were aligned with MAFFT [-linsi], alignments were trimmed with trimAl [-gappyout], and the trimmed alignments were concatenated into a FASTA file that included 153 taxa and 95,968 amino acid sites (Data/MSAs/extended_concatenate.phylip).

Chronogram inference

We used Phylobayes21,33 mpi v.1.8b to sample phylograms (branch lengths) for the chronogram sampling process. In particular, two chains were run for more than 11,000 generations using the CAT + GTR + G4 model (‘CAT’ stands for stick-breaking Dirichlet process mixture, ‘GTR’ for amino acid exchangeabilities estimated from the data and ‘G4’ for discrete gamma distribution of rates across sites with four categories). The phylogram sampling process was accelerated by constraining the sampling of branch lengths to a fixed species tree topology (Fig. 3). A burn-in of the first 5,000 generations was considered after chain convergence assessment. Post burn-in resulted in two sets of 6,390 phylograms per chain. In total, this analysis took 22 days on 192 threads of Intel Xeon 4116 CPU @ 2.1 GHz for each chain. We next used Mcmcdate50,51 v.1.0.0.0 software to sample chronograms based on the sampled phylograms, using the auto-correlated lognormal model and the full covariance matrix to approximate the likelihood calculation. We arbitrarily chose the phylograms from the first chain as input for Mcmcdate, because an exploration made revealed very minor differences between chronogram sets obtained from four distinct Mcmcdate runs (two runs per phylogram set—chain 1 and chain 2; Supplementary Table 4). The MCMC sampler was run for 8,000 iterations after a burn-in of 4,930 iterations, sampling a timetree for every 10 iterations. Each Mcmcdate run took <1 day on a standard computer. Data files from each chronogram analysis (‘Default’, ‘PSE-constraint A’, ‘PSE-constraint A+calib’ and ‘PSE-constraints B + C’) are available in Data/Chronograms. For hard bound and soft bound calibrations (Supplementary Information section 1), we allowed, respectively, 0.01% and 3% of the probability mass to fall outside the corresponding age boundary. In the case of the constraints, the probability mass allowed to fall outside was 2.5%.

Dating PSE content expansions

PSE content over time in the ancestral paths leading to Cadophora sp. (Pezizomycotina) and Mycena galopus (Agaricomycotina) were computed by crossing information on (1) ancestral PSE content (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6) with (2) branch existence probability over time. In particular, PSE content for every million year (My) time unit was computed with a weighted mean in which every branch in the evolutionary path towards the target species (either Cadophora sp. or M. galopus) had an influence on each My unit according to a specific weight determined by the relative frequency of chronograms supporting the existence of that branch lineage in the given My time unit. All chronograms sampled in the process of constructing the consensus chronogram shown in Fig. 3 (Data/Chronograms) were used for this purpose.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28046594 (ref. 103). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Stajich, J. et al. The Fungi. Curr. Biol. 19, R840–R845 (2009).

Berbee, M. L., James, T. Y. & Strullu-Derrien, C. Early diverging fungi: diversity and impact at the dawn of terrestrial life. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 71, 41–60 (2017).

Selosse, M.-A. & Le Tacon, F. The land flora: a phototroph–fungus partnership? Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 15–20 (1998).

Gross, M. The success story of plants and fungi. Curr. Biol. 29, R183–R185 (2019).

Smith, T. J. & Donoghue, P. C. J. Evolution of fungal phenotypic disparity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1489–1500 (2022).

Naranjo-Ortiz, M. A. & Gabaldón, T. Fungal evolution: major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions. Biol. Rev. 94, 1443–1476 (2019).

Kües, U., Khonsuntia, W. & Subba, S. Complex fungi. Fungal Biol. Rev. 32, 205–218 (2018).

Kiss, E. et al. Comparative genomics reveals the origin of fungal hyphae and multicellularity. Nat. Commun. 10, 4080 (2019).

Chang, Y. et al. Genome-scale phylogenetic analyses confirm Olpidium as the closest living zoosporic fungus to the non-flagellated, terrestrial fungi. Sci Rep. 11, 3217 (2021).

James, T. Y. et al. Reconstructing the early evolution of Fungi using a six-gene phylogeny. Nature 443, 818–822 (2006).

Torruella, G., de Mendoza, A., Grau-Bové, X. & Ruiz-Trillo, I. Phylogenomics reveals convergent evolution of lifestyles in close relatives of animals and fungi. Curr. Biol. 25, 2404–2410 (2015).

Galindo, L. J. et al. Phylogenomics supports the monophyly of aphelids and fungi and identifies new molecular synapomorphies. Syst. Biol. 72, 505–515 (2022).

Galindo, L. J., López-García, P., Torruella, G., Karpov, S. & Moreira, D. Phylogenomics of a new fungal phylum reveals multiple waves of reductive evolution across Holomycota. Nat. Commun. 12, 4973 (2021).

Torruella, G. et al. Global transcriptome analysis of the aphelid Paraphelidium tribonemae supports the phagotrophic origin of fungi. Commun. Biol. 1, 231 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. A genome-scale phylogeny of the kingdom Fungi. Curr. Biol. 31, 1653–1665 (2021).

Strassert, J. F. H. & Monaghan, M. T. Phylogenomic insights into the early diversification of fungi. Curr. Biol. 32, P3628–3635.e3 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. A taxon-rich and genome-scale phylogeny of Opisthokonta. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002794 (2024).

Grigoriev, I. V. et al. Fueling the future with fungal genomics. Mycology 2, 192–209 (2011).

Grigoriev, I. V. et al. MycoCosm portal: gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D699–D704 (2014).

Reis, M. D. & Yang, Z. Approximate likelihood calculation on a phylogeny for Bayesian estimation of divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2161–2172 (2011).

Lartillot, N., Brinkmann, H. & Philippe, H. Suppression of long-branch attraction artefacts in the animal phylogeny using a site-heterogeneous model. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 1–26 (2007).

Szánthó, L. L., Lartillot, N., Szöllősi, G. J. & Schrempf, D. Compositionally constrained sites drive long-branch attraction. Syst. Biol. 72, 767–780 (2023).

Berbee, M. L. et al. Genomic and fossil windows into the secret lives of the most ancient fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 717–730 (2020).

Taylor, T. N & Krings, M. Fossil Fungi (Elsevier, 2014).

Schrempf, D., Lartillot, N. & Szöllősi, G. Scalable empirical mixture models that account for across-site compositional heterogeneity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 3616–3631 (2020).

Foster, P. G. Modeling compositional heterogeneity. Syst. Biol. 53, 485–495 (2004).

Baños, H. Is over-parameterization a problem for profile mixture models? Syst. Biol. 73, 53–75 (2024).

Feuda, R. et al. Improved modeling of compositional heterogeneity supports sponges as sister to all other animals. Curr. Biol. 27, 3864–3870 (2017).

Williams, T. A., Cox, C. J., Foster, P. G., Szöllősi, G. J. & Embley, T. M. Phylogenomics provides robust support for a two-domains tree of life. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 138–147 (2020).

Philippe, H. et al. Resolving difficult phylogenetic questions: why more sequences are not enough. PLoS Biol. 9, e1000602 (2011).

Muñoz-Gómez, S. A. et al. Site-and-branch-heterogeneous analyses of an expanded dataset favour mitochondria as sister to known Alphaproteobacteria. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 253–262 (2022).

Bujaki, T. & Rodrigue, N. Bayesian cross-validation comparison of amino acid replacement models: contrasting profile mixtures, pairwise exchangeabilities, and gamma-distributed rates-across-sites. J. Mol. Evol. 90, 468–475 (2022).

Lartillot, N. & Philippe, H. A Bayesian mixture model for across-site heterogeneities in the amino-acid replacement process. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1095–1109 (2004).

Williams, T. A. et al. Inferring the deep past from molecular data. Genome Biol. Evol. 13, evab067 (2021).

Lartillot, N., Rodrigue, N., Stubbs, D. & Richer, J. PhyloBayes MPI: phylogenetic reconstruction with infinite mixtures of profiles in a parallel environment. Syst. Biol. 62, 611–615 (2013).

Lartillot, N., Lepage, T. & Blanquart, S. PhyloBayes 3: a Bayesian software package for phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular dating. Bioinformatics 25, 2286–2288 (2009).

Zhang, C., Rabiee, M., Sayyari, E. & Mirarab, S. ASTRAL-III: polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinf. 19, 153 (2018).

Spatafora, J. W. et al. A phylum-level phylogenetic classification of zygomycete fungi based on genome-scale data. Mycologia 108, 1028–1046 (2016).

Shimodaira, H. An approximately unbiased test of phylogenetic tree selection. Syst. Biol. 51, 492–508 (2002).

Williams, T. A. et al. Phylogenetic reconciliation: making the most of genomes to understand microbial ecology and evolution. ISME J. 18, wrae129 (2024).

Sanders, K. L. & Lee, M. S. Y. Evaluating molecular clock calibrations using Bayesian analyses with soft and hard bounds. Biol. Lett. 3, 275–279 (2007).

Parham, J. F. et al. Best practices for justifying fossil calibrations. Syst. Biol. 61, 346–359 (2012).

Donoghue, P. C. J. & Yang, Z. The evolution of methods for establishing evolutionary timescales. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20160020 (2016).

Morris, J. L. et al. The timescale of early land plant evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E2274–E2283 (2018).

Bidartondo, M. I. et al. The dawn of symbiosis between plants and fungi. Biol. Lett. 7, 574–577 (2011).

Field, K. J. & Pressel, S. Unity in diversity: structural and functional insights into the ancient partnerships between plants and fungi. New Phytol. 220, 996–1011 (2018).

Davín, A. A. et al. Gene transfers can date the Tree of Life. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 904–909 (2018).

Chauve, C. et al. MaxTiC: fast ranking of a phylogenetic tree by maximum time consistency with lateral gene transfers. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/127548 (2017).

Szöllõsi, G. J. et al. Relative time constraints improve molecular dating. Syst. Biol. 71, 797–809 (2022).

Harris, B. J. et al. Divergent evolutionary trajectories of bryophytes and tracheophytes from a complex common ancestor of land plants. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1634–1643 (2022).

Schrempf, D. McmcDate. GitHub https://github.com/dschrempf/mcmc-date (2024).

Chang, Y. et al. Phylogenomic analyses indicate that early fungi evolved digesting cell walls of algal ancestors of land plants. Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 1590–1601 (2015).

Eder, M. & Lütz-Meindl, U. Pectin-like carbohydrates in the green alga Micrasterias characterized by cytochemical analysis and energy filtering TEM. J. Microsc. 231, 201–214 (2008).

Domozych, D. S. & LoRicco, J. G. The extracellular matrix of green algae. Plant Physiol. 194, 15–32 (2024).

Herburger, K., Ryan, L. M., Popper, Z. A. & Holzinger, A. Localisation and substrate specificities of transglycanases in charophyte algae relate to development and morphology. J. Cell Sci. 131, jcs203208 (2018).

O’Rourke, C., Gregson, T., Murray, L., Sadler, I. H. & Fry, S. C. Sugar composition of the pectic polysaccharides of charophytes, the closest algal relatives of land-plants: presence of 3-O-methyl-d-galactose residues. Ann. Bot. 116, 225–236 (2015).

Rapin, M. N., Murray, L., Sadler, I. H., Bothwell, J. H. & Fry, S. C. Same but different—pseudo‐pectin in the charophytic alga Chlorokybus atmophyticus. Physiol. Plant. 175, e14079 (2023).

Rapin, M. N., Bothwell, J. H. & Fry, S. C. Pectin-like heteroxylans in the early-diverging charophyte Klebsormidium fluitans. Ann. Bot. 134, 1191–1206 (2024).

Smith, S., E. & Read, D. J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis (Academic Press, 2010).

Spatafora, J. W. et al. The fungal tree of life: from molecular systematics to genome-scale phylogenies. Microbiol. Spectr. 5, 5.5.03 (2017).

Lutzoni, F. et al. Contemporaneous radiations of fungi and plants linked to symbiosis. Nat. Commun. 9, 5451 (2018).

Chang, Y. et al. Phylogenomics of Endogonaceae and evolution of mycorrhizas within Mucoromycota. New Phytol. 222, 511–525 (2019).

Loron, C. C. et al. Early fungi from the Proterozoic era in Arctic Canada. Nature 570, 232–235 (2019).

Bonneville, S. et al. Molecular identification of fungi microfossils in a Neoproterozoic shale rock. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax7599 (2020).

Hermann, T. N. & Podkovyrov, V. N. A discovery of riphean heterotrophs in the Lakhanda group of Siberia. Paleontol. J. 44, 374–383 (2010).

Buick, R., Des Marais, D. J. & Knoll, A. H. Stable isotopic compositions of carbonates from the Mesoproterozoic Bangemall group, northwestern Australia. Chem. Geol. 123, 153–171 (1995).

Javaux, E. J. & Lepot, K. The Paleoproterozoic fossil record: implications for the evolution of the biosphere during Earth’s middle-age. Earth Sci. Rev. 176, 68–86 (2018).

Bowles, A. M. C., Williamson, C. J., Williams, T. A., Lenton, T. M. & Donoghue, P. C. J. The origin and early evolution of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 28, 312–329 (2023).

Porter, S. M. & Riedman, L. A. Frameworks for interpreting the early fossil record of Eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 77, 173–191 (2023).

Porter, S. M., Riedman, L. A., Woltz, C. R., Gold, D. A. & Kellogg, J. B. Early eukaryote diversity: a review and a reinterpretation. Paleobiology 51, 132–149 (2025).

Simpson, C. Adaptation to a viscous Snowball Earth Ocean as a path to complex multicellularity. Am. Nat. 198, 590–609 (2021).

Crockett, W. W., Shaw, J. O., Simpson, C. & Kempes, C. P. Physical constraints during Snowball Earth drive the evolution of multicellularity. Proc. R. Soc. B 291, 20232767 (2024).

Bierenbroodspot, M. J. et al. Phylogenomic insights into the first multicellular streptophyte. Curr. Biol. 34, 670–681.e7 (2024).

De Vries, J. & Archibald, J. M. Plant evolution: landmarks on the path to terrestrial life. New Phytol. 217, 1428–1434 (2018).

Mitchell, R. L. et al. Cryptogamic ground covers as analogues for early terrestrial biospheres: initiation and evolution of biologically mediated proto-soils. Geobiology 19, 292–306 (2021).

Puginier, C., Keller, J. & Delaux, P.-M. Plant–microbe interactions that have impacted plant terrestrializations. Plant Physiol. 190, 72–84 (2022).

Krings, M. et al. Fungal endophytes in a 400‐million‐yr‐old land plant: infection pathways, spatial distribution, and host responses. New Phytol. 174, 648–657 (2007).

Honegger, R., Edwards, D. & Axe, L. The earliest records of internally stratified cyanobacterial and algal lichens from the Lower Devonian of the Welsh Borderland. New Phytol. 197, 264–275 (2013).

Kataržytė, M., Vaičiūtė, D., Bučas, M., Gyraitė, G. & Petkuvienė, J. Microorganisms associated with charophytes under different salinity conditions. Oceanologia 59, 177–186 (2017).

Knack, J. J. et al. Microbiomes of streptophyte algae and bryophytes suggest that a functional suite of microbiota fostered plant colonization of land. Int. J. Plant Sci. 176, 405–420 (2015).

Karling, K. S. Studies in the chytridiales III. A parasitic chytrid causing cell hypertrophy in chara. Am. J. Botany. 15, 485–496 (1928).

Gachon, C. M. M., Sime-Ngando, T., Strittmatter, M., Chambouvet, A. & Kim, G. H. Algal diseases: spotlight on a black box. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 633–640 (2010).

Jephcott, T. G., van Ogtrop, F. F., Gleason, F. H., Macarthur, D. J. & Sholz, B. in The Fungal Community: Its Organization and Role in the Ecosystem (eds Dighton, J. & White, J. F.) 239–255 (CRC Press, 2017).

Enright, A. J., Van Dongen, S. & Ouzounis, C. A. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 1575–1584 (2002).

Altschul, S., Gish, W. & Miller, W. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2—approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 5, e9490 (2010).

Merényi, Z. et al. Genomes of fungi and relatives reveal delayed loss of ancestral gene families and evolution of key fungal traits. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1221–1231 (2023).

Simao, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Eddy, S. R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195 (2011).

Schliep, K. P. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27, 592–593 (2011).

Capella-Gutierrez, S., Silla-Martinez, J. M. & Gabaldon, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Vankan, M., Ho, S. Y. W. & Duchêne, D. A. Evolutionary rate variation among lineages in gene trees has a negative impact on species-tree inference. Syst. Biol. 71, 490–500 (2022).

Wang, H. C., Minh, B. Q., Susko, E. & Roger, A. J. Modeling site heterogeneity with posterior mean site frequency profiles accelerates accurate phylogenomic estimation. Syst. Biol. 67, 216–235 (2018).

Giacomelli, M. et al. CAT-posterior mean site frequencies improves phylogenetic modeling under maximum likelihood and resolves tardigrada as the sister of Arthropoda plus Onychophora. Genome Biol. Evol. 17, evae273 (2025).

Ly-Trong, N., Barca, G. M. J. & Minh, B. Q. AliSim-HPC: parallel sequence simulator for phylogenetics. Bioinformatics 39, btad540 (2023).

Szöllosi, G. J., Rosikiewicz, W., Boussau, B., Tannier, E. & Daubin, V. Efficient exploration of the space of reconciled gene trees. Syst. Biol. 62, 901–912 (2013).

Shimodaira, H. & Hasegawa, M. CONSEL: for assessing the confidence of phylogenetic tree selection. Bioinformatics 17, 1246–1247 (2001).

Strassert, J. F. H., Irisarri, I., Williams, T. A. & Burki, F. A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids. Nat. Commun. 12, 1879 (2021).

Torruella, G., Galindo, L. J., Moreira, D. & López-García, P. Phylogenomics of neglected flagellated protists supports a revised eukaryotic tree of life. Curr. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2024.10.075 (2024).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Ocaña-Pallarès, E. Supplementary Data Files: ‘A timetree of Fungi dated with fossils and horizontal gene transfers’. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28046594 (2025).

Acknowledgements

J. Longcore is thanked for valuable discussions on the placement of the fossil Rhizophydites matryoshkae. The authors also thank the three reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. We are grateful for the help and support provided by the Scientific Computing and Data Analysis section of Core Facilities at OIST. This project was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences to Z.M. (grant no. BO/00269/24/8). L.L.S., G.J.S. and E.O.-P. received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 714774). P.D. was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant nos BB/T012773/1 and BB/Y003624/1), the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (grant no. 10.37807/GBMF9741), the Leverhulme Trust (grant nos. RF-2022-167 and RPG-2020-199) and the John Templeton Foundation (grant no. 62220; the opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation). T.G. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant nos PID2021-126067NB-I00, CPP2021-008552, PCI2022-135066-2 and PDC2022-133266-I00), cofounded by ERDF ‘A way of making Europe’, as well as support from the Catalan Research Agency (AGAUR) (grant no. SGR01551), European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant no. ERC-2016-724173); Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (grant number GBMF9742); ‘La Caixa’ foundation (grant no. LCF/PR/HR21/00737) and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (IMPACT grant nos. IMP/00019 and CIBERINFEC CB21/13/00061- ISCIII-SGEFI/ERDF). L.G.N. was supported by the National Research Development and Innovation Office (grant no. OTKA 142188) and the European Research Council (grant no. 101086900). E.O.-P. acknowledges support from FJC2021-046869-I funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR, as well as from the Beatriu de Pinós programme (BP 2022, file number BP 00075). This work is part of the grant RYC2023-042807-I, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the ESF+. The project that gave rise to these results received also the support of a fellowship from the La Caixa Foundation (ID 100010434). The fellowship code is ‘LCF/BQ/PI24/12040009’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: E.O.-P., G.J.S. and L.G.N. Methodology: E.O.-P., G.J.S., L.G.N., L.L.S., Z.M., P.D. and T.G. Investigation: E.O.-P., G.J.S., L.G.N., L.L.S., Z.M., P.D. and T.G. Visualization: E.O.-P., L.L.S. and Z.M. Funding acquisition: E.O.-P., G.J.S. and L.G.N. Project administration: E.O.-P., G.J.S. and L.G.N. Supervision: E.O.-P., G.J.S. and L.G.N. Writing—original draft: E.O.-P., L.L.S., Z.M., G.J.S., L.G.N., P.D. and T.G. Writing—review and editing: E.O.-P., L.L.S., Z.M., G.J.S., L.G.N., P.D. and T.G.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Iker Irisarri and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Phylogenetic tree of the original dataset of 122 taxa, reconstructed with a dataset of 97,487 amino acid sites, reconstructed by means of the CAT-pmsf pipeline.

(see Main text and Methods). Ultrafast bootstrap support values are shown in nodes. The root of the tree was set in the split of the tree separating Amoebozoa from the rest of the tree.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Species tree topology reconstructed by coalescent methods (ASTRAL).

In contrast to the concatenate approach from the main analysis, to run ASTRAL, we first run Phylobayes (CAT + GTR + G4 model) on the trimmed multiple sequence alignment of each of our 225 phylogenetic markers. We then run Phylobayes bpcomp to compute a consensus with branch supports by pooling the trees of all the runs obtained. The retrieved topologies (1 per gene tree) were put together into a single text file used as input to run ASTRAL version 5.7.8 with the default settings (ASTRAL annotates branches by default with the posterior probability values obtained for the main resolution). As in Strassert et al. 2022 (Current Biology, Volume 32, Issue 16, Pages 3628-3635.e3), before running ASTRAL, branches with bipartition support below 10% were collapsed as recommended by the developers.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Consensus chronogram reconstruction based on the core set of timing information (‘Default’ analysis).