Abstract

The neutral theory of molecular evolution, positing that most amino acid substitutions in protein evolution are neutral, is supported by vast comparative genomic data. However, here we report that the key premise of the theory—beneficial mutations are extremely scarce—is violated. Deep mutational scanning data from 12,267 amino acid-altering mutations in 24 prokaryotic and eukaryotic genes reveal that > 1% of these mutations are beneficial, predicting that > 99% of amino acid substitutions would be adaptive. This observation demands a new theory that is compatible with both the high beneficial mutation rate and the comparative genomic data considered consistent with the neutral theory. We propose such a theory named adaptive tracking with antagonistic pleiotropy. In this theory, virtually all beneficial mutations observed are environment specific. Frequent environmental changes and mutational antagonistic pleiotropy across environments render most of the beneficial mutations seen at one time deleterious soon after and hence rarely fixed. Consequently, despite the occurrence of adaptive tracking—continuous adaptation to a changing environment fuelled by beneficial mutations—neutral substitutions prevail. We show that this theory is supported by population genetics simulation, empirical observations and experimental evolution and has implications for the adaptedness of natural populations and the tempo and mode of evolution.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The Illumina sequencing data have been deposited to NCBI SRA under the accession number PRJNA1181288. Data for generating figures are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17149945 (ref. 93).

Code availability

Custom code is available via Github at https://github.com/song88180/Adaptive_Tracking_with_Antagonistic_Pleiotropy/releases/tag/v1.

References

Kimura, M. Evolutionary rate at the molecular level. Nature 217, 624–626 (1968).

King, J. L. & Jukes, T. H. Non-Darwinian evolution. Science 164, 788–798 (1969).

Kimura, M. The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1983).

Zhang, J. in Evolution Since Darwin: The First 150 Years (eds Bell, M. A. et al.) 87–118 (Sinauer, 2010).

Zuckerkandl, E. & Pauling, L. in Horizons in Biochemistry (eds Kasha, M. & Pullman, B.) 189–225 (Academic Press, 1962).

Ohta, T. The nearly neutral theory of molecular evolution. Annu Rev. Ecol. Syst. 23, 263–286 (1992).

Zhang, J. in Oxford Bibliographies in Evolutionary Biology (ed. K. Pfennig) (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Kern, A. D. & Hahn, M. W. The neutral theory in light of natural selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1366–1371 (2018).

Smith, N. G. & Eyre-Walker, A. Adaptive protein evolution in Drosophila. Nature 415, 1022–1024 (2002).

Jensen, J. D. et al. The importance of the neutral theory in 1968 and 50 years on: a response to Kern and Hahn 2018. Evolution 73, 111–114 (2019).

Nei, M., Suzuki, Y. & Nozawa, M. The neutral theory of molecular evolution in the genomic era. Annu Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet 11, 265–289 (2010).

Kimura, M. On the probability of fixation of mutant genes in a population. Genetics 47, 713–719 (1962).

Eyre-Walker, A. & Keightley, P. D. The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 610–618 (2007).

Wei, H. & Li, X. Deep mutational scanning: a versatile tool in systematically mapping genotypes to phenotypes. Front. Genet. 14, 1087267 (2023).

Shen, X., Song, S., Li, C. & Zhang, J. Synonymous mutations in representative yeast genes are mostly strongly non-neutral. Nature 606, 725–731 (2022).

Shen, X., Song, S., Li, C. & Zhang, J. Further evidence for strong non-neutrality of yeast synonymous mutations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 41, msae224 (2024).

Chen, P. & Zhang, J. Asexual experimental evolution of yeast does not curtail transposable elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 2831–2842 (2021).

Flynn, J. M. et al. Comprehensive fitness maps of Hsp90 show widespread environmental dependence. eLife 9, e53810 (2020).

Roscoe, B. P., Thayer, K. M., Zeldovich, K. B., Fushman, D. & Bolon, D. N. Analyses of the effects of all ubiquitin point mutants on yeast growth rate. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 1363–1377 (2013).

Thompson, S., Zhang, Y., Ingle, C., Reynolds, K. A. & Kortemme, T. Altered expression of a quality control protease in E. coli reshapes the in vivo mutational landscape of a model enzyme. eLife 9, e53476 (2020).

Levy, S. F. et al. Quantitative evolutionary dynamics using high-resolution lineage tracking. Nature 519, 181–186 (2015).

Couce, A. et al. Changing fitness effects of mutations through long-term bacterial evolution. Science 383, eadd1417 (2024).

Joseph, S. B. & Hall, D. W. Spontaneous mutations in diploid Saccharomyces cerevisiae: more beneficial than expected. Genetics 168, 1817–1825 (2004).

Bondel, K. B. et al. Inferring the distribution of fitness effects of spontaneous mutations in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000192 (2019).

Bondel, K. B. et al. The distribution of fitness effects of spontaneous mutations in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii inferred using frequency changes under experimental evolution. PLoS Genet. 18, e1009840 (2022).

Rutter, M. T., Roles, A. J. & Fenster, C. B. Quantifying natural seasonal variation in mutation parameters with mutation accumulation lines. Ecol. Evol. 8, 5575–5585 (2018).

Wiser, M. J., Ribeck, N. & Lenski, R. E. Long-term dynamics of adaptation in asexual populations. Science 342, 1364–1367 (2013).

Tenaillon, O. et al. Tempo and mode of genome evolution in a 50,000-generation experiment. Nature 536, 165–170 (2016).

Bailey, S. F., Alonso Morales, L. A. & Kassen, R. Effects of synonymous mutations beyond codon bias: the evidence for adaptive synonymous substitutions from microbial evolution experiments. Genome Biol. Evol. 13, evab141 (2021).

Zhang, J. & Qian, W. Functional synonymous mutations and their evolutionary consequences. Nat. Rev. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-025-00850-1 (2025).

Johnson, M. S. et al. Phenotypic and molecular evolution across 10,000 generations in laboratory budding yeast populations. eLife 10, e63910 (2021).

Li, W. H., Gojobori, T. & Nei, M. Pseudogenes as a paradigm of neutral evolution. Nature 292, 237–239 (1981).

Otto, S. P. & Whitlock, M. C. in Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (John Wiley & Sons, 2013).

Roles, A. J., Rutter, M. T., Dworkin, I., Fenster, C. B. & Conner, J. K. Field measurements of genotype by environment interaction for fitness caused by spontaneous mutations in Arabidopsis thaliana. Evolution 70, 1039–1050 (2016).

Wang, A. D., Sharp, N. P., Spencer, C. C., Tedman-Aucoin, K. & Agrawal, A. F. Selection, epistasis, and parent-of-origin effects on deleterious mutations across environments in Drosophila melanogaster. Am. Nat. 174, 863–874 (2009).

Li, C. & Zhang, J. Multi-environment fitness landscapes of a tRNA gene. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1025–1032 (2018).

Qian, W., Ma, D., Xiao, C., Wang, Z. & Zhang, J. The genomic landscape and evolutionary resolution of antagonistic pleiotropy in yeast. Cell Rep. 2, 1399–1410 (2012).

Wei, X. & Zhang, J. The genomic architecture of interactions between natural genetic polymorphisms and environments in yeast growth. Genetics 205, 925–937 (2017).

Wei, X. & Zhang, J. Environment-dependent pleiotropic effects of mutations on the maximum growth rate r and carrying capacity K of population growth. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000121 (2019).

Chen, P. & Zhang, J. Antagonistic pleiotropy conceals molecular adaptations in changing environments. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 461–469 (2020).

Chen, P. & Zhang, J. The loci of environmental adaptation in a model eukaryote. Nat. Commun. 15, 5672 (2024).

Zhang, J. Patterns and evolutionary consequences of pleiotropy. Annu Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 54, 1–19 (2023).

Simons, A. M. Modes of response to environmental change and the elusive empirical evidence for bet hedging. Proc. Biol. Sci. 278, 1601–1609 (2011).

Haller, B. C. & Messer, P. W. SLiM 2: flexible, interactive forward genetic simulations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 230–240 (2017).

Bromham, L. & Penny, D. The modern molecular clock. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4, 216–224 (2003).

Machado, H. E. et al. Broad geographic sampling reveals the shared basis and environmental correlates of seasonal adaptation in Drosophila. eLife 10, e67577 (2021).

Rudman, S. M. et al. Direct observation of adaptive tracking on ecological time scales in Drosophila. Science 375, eabj7484 (2022).

Tenaillon, O. et al. The molecular diversity of adaptive convergence. Science 335, 457–461 (2012).

Huang, C. J., Lu, M. Y., Chang, Y. W. & Li, W. H. Experimental evolution of yeast for high-temperature tolerance. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1823–1839 (2018).

Toprak, E. et al. Evolutionary paths to antibiotic resistance under dynamically sustained drug selection. Nat. Genet. 44, 101–105 (2011).

Barrick, J. E. & Lenski, R. E. Genome dynamics during experimental evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 827–839 (2013).

McDonald, M. J. Microbial experimental evolution—a proving ground for evolutionary theory and a tool for discovery. EMBO Rep. 20, e46992 (2019).

Miura, S., Zhang, Z. & Nei, M. Random fluctuation of selection coefficients and the extent of nucleotide variation in human populations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 10676–10681 (2013).

Abdul-Rahman, F., Tranchina, D. & Gresham, D. Fluctuating environments maintain genetic diversity through neutral fitness effects and balancing selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4362–4375 (2021).

Lourenco, J. M., Glemin, S. & Galtier, N. The rate of molecular adaptation in a changing environment. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1292–1301 (2013).

Huerta-Sanchez, E., Durrett, R. & Bustamante, C. D. Population genetics of polymorphism and divergence under fluctuating selection. Genetics 178, 325–337 (2008).

Gordo, I. & Campos, P. R. Evolution of clonal populations approaching a fitness peak. Biol. Lett. 9, 20120239 (2013).

Johnson, O. L., Tobler, R., Schmidt, J. M. & Huber, C. D. Fluctuating selection and the determinants of genetic variation. Trends Genet. 39, 491–504 (2023).

Wittmann, M. J., Bergland, A. O., Feldman, M. W., Schmidt, P. S. & Petrov, D. A. Seasonally fluctuating selection can maintain polymorphism at many loci via segregation lift. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E9932–E9941 (2017).

Haldane, J. B. S. & Jayakar, S. D. Polymorphism due to selection of varying direction. J. Genet. 58, 237–242 (1963).

Cvijovic, I., Good, B. H., Jerison, E. R. & Desai, M. M. Fate of a mutation in a fluctuating environment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E5021–E5028 (2015).

Gillespie, J. H. The Causes of Molecular Evolution (Oxford Univ. Press, 1991).

Levins, R. Evolution in Changing Environments; Some Theoretical Explorations (Princeton Univ. Press, 1968).

Bell, G. Fluctuating selection: the perpetual renewal of adaptation in variable environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365, 87–97 (2010).

Kimura, M. Process leading to quasi-fixation of genes in natural populations due to random fluctuation of selection intensities. Genetics 39, 280–295 (1954).

Lynch, M., Wei, W., Ye, Z. & Pfrender, M. The genome-wide signature of short-term temporal selection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2307107121 (2024).

Torrillo, P. A. & Lieberman, T. D. Reversions mask the contribution of adaptive evolution in microbiomes. eLife 13, e93146 (2024).

Neel, J. V. Diabetes mellitus: a ‘thrifty’ genotype rendered detrimental by ‘progress’?. Am. J. Hum. Genet 14, 353–362 (1962).

Kassen, R. The experimental evolution of specialists, generalists, and the maintenance of diversity. J. Evol. Biol. 15, 173–190 (2002).

Ghalambor, C. K. et al. Non-adaptive plasticity potentiates rapid adaptive evolution of gene expression in nature. Nature 525, 372–375 (2015).

Ho, W. C. & Zhang, J. Evolutionary adaptations to new environments generally reverse plastic phenotypic changes. Nat. Commun. 9, 350 (2018).

Ho, W. C. & Zhang, J. Genetic gene expression changes during environmental adaptations tend to reverse plastic changes even after the correction for statistical nonindependence. Mol. Biol. Evol. 36, 1847–1848 (2019).

Kruglyak, L. et al. Insufficient evidence for non-neutrality of synonymous mutations. Nature 616, E8–E9 (2023).

Baba, T. et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006.0008 (2006).

Winzeler, E. A. et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285, 901–906 (1999).

Lynch, M. & Marinov, G. K. The bioenergetic costs of a gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15690–15695 (2015).

Gerrish, P. J. & Lenski, R. E. The fate of competing beneficial mutations in an asexual population. Genetica 102/103, 127–144 (1998).

Liu, H. & Zhang, J. Yeast spontaneous mutation rate and spectrum vary with environment. Curr. Biol. 29, 1584–1591 (2019).

Agrawal, A. F. & Whitlock, M. C. Inferences about the distribution of dominance drawn from yeast gene knockout data. Genetics 187, 553–566 (2011).

Grieshop, K. & Arnqvist, G. Sex-specific dominance reversal of genetic variation for fitness. PLoS Biol. 16, e2006810 (2018).

Chao, L. & Carr, D. E. The molecular clock and the relationship between population size and generation time. Evolution 47, 688–690 (1993).

Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123, 585–595 (1989).

Fu, Y. X. & Li, W. H. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics 133, 693–709 (1993).

Fay, J. C. & Wu, C. I. Hitchhiking under positive Darwinian selection. Genetics 155, 1405–1413 (2000).

Zeng, K., Fu, Y. X., Shi, S. & Wu, C. I. Statistical tests for detecting positive selection by utilizing high-frequency variants. Genetics 174, 1431–1439 (2006).

Garud, N. R., Messer, P. W., Buzbas, E. O. & Petrov, D. A. Recent selective sweeps in North American Drosophila melanogaster show signatures of soft sweeps. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005004 (2015).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Ranwez, V., Douzery, E. J. P., Cambon, C., Chantret, N. & Delsuc, F. MACSE v2: toolkit for the alignment of coding sequences accounting for frameshifts and stop codons. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 2582–2584 (2018).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Park, C., Chen, X., Yang, J. R. & Zhang, J. Differential requirements for mRNA folding partially explain why highly expressed proteins evolve slowly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E678–E686 (2013).

Zhang, J., Rosenberg, H. F. & Nei, M. Positive Darwinian selection after gene duplication in primate ribonuclease genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 3708–3713 (1998).

Song, S., Chen, P. Shen, X. & Zhang, J. Adaptive tracking with antagonistic pleiotropy results in seemingly neutral molecular evolution. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17149945 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Jiang, W. Qian, X. Wei, H. Xu and J. Yang for valuable comments. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health research grant R35GM139484 to J.Z.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. conceived of the study. S.S., P.C. and J.Z. designed the study. S.S. performed the simulation. P.C. performed the experiments. S.S., P.C. and X.S. analysed the data. S.S., P.C. and J.Z. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks B. Jesse Shapiro, Olivier Tenaillon, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Distribution of individual mutational fitness effects and inferred Ω and 1-α under various conditions.

a, Fitness effects of individual beneficial non-synonymous mutations in the 21 yeast genes. Each dot represents the point estimate of the fitness effect of a mutation, with its standard error shown by the error bar. Red indicates a significant fitness effect (nominal P < 0.05), whereas grey indicates a non-significant fitness effect. b–c, Inferred Ω (b) and 1-α (c) when various statistical stringencies are applied in calling significant fitness effects of mutations. Under a statistical cutoff, Ω and 1-α are estimated by setting all non-significant fitness effects at 0. d–e, Inferred Ω (d) and 1-α (e) when asexual populations are considered. f–g, Inferred Ω (f) and 1-α (g) when the effective population size (Ne) is 104. See Fig. 1b,c for symbol definitions.

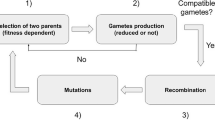

Extended Data Fig. 2 Conceptual illustration of (a) neutral, (b) adaptive, and (c) adaptive tracking models of molecular evolution in sexual populations.

In each panel, the left diagram shows mutant frequencies over time, whereas the right diagram shows fractions of deleterious, neutral, and beneficial mutations (upper bar) and substitutions (lower bar), respectively. All three models assume that most mutations are deleterious. The neutral model assumes negligible beneficial mutations, so most substitutions are due to random fixations of neutral mutations. The adaptive model allows a non-negligible fraction of beneficial mutations, resulting in substitutions being largely beneficial and driven to fixation by positive selection. The adaptive tracking (with antagonistic pleiotropy) model allows a non-negligible fraction of beneficial mutations but assumes that these beneficial mutations soon become deleterious when the environment changes and thereby cannot reach fixation; consequently, most substitutions are neutral.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Derived allele frequency spectra, polymorphisms, substitutions, and substitution rates under various evolutionary models simulated, with conditions not considered in Fig. 2.

a–d, Allele frequency spectra (a), polymorphisms (b), substitutions (c), and Ω (d) under AdapTrack with a constant or fluctuating population size (indicated by “fluc”). e–h, Allele frequency spectra (e), polymorphisms (f), substitutions (g), and Ω (h) under AdapTrack with different fractions of neutral mutations that reflect different levels of gene importance. i–l, Allele frequency spectra (i), polymorphisms (j), substitutions (k), and Ω (l) under AdapTrack with different ranges of the probability that a sometimes-beneficial mutation can be beneficial in an environment. m–p, Allele frequency spectra (m), polymorphisms (n), substitutions (o), and Ω (p) under AdapTrack in which the magnitude of an environmental change that occurs every generation follows an exponential distribution (see Methods). The larger the mean of the exponential distribution, the greater the mean and variance of the magnitude of the environment changes. q–t, Allele frequency spectra (q), polymorphisms (r), substitutions (s), and Ω (t) under Neutral, Adaptive, and AdapTrack with or without dominance. With dominance (indicated by “dom”), the coefficient of dominance of a mutation in an environment is h = 0.75 if the mutation is beneficial in the environment, 0.50 if the mutation is neutral, and 0.25 if the mutation is deleterious. Without dominance, h = 0.50 regardless of the mutational fitness effect.

Extended Data Fig. 4 non-synonymous substitution rates (dN) of 90 fly genes likely under parallel seasonal (antagonistic) selections and those of 100 negative control genes.

The violin plot shows the frequency distribution, with the red dot representing the mean and the top and bottom horizontal bars respectively indicating the maximal and minimal values. Genes under antagonistic selections have significantly lower dN than the negative control genes (P = 0.0025, t-test).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Population dynamics of non-synonymous SNVs in a changing environment and corresponding constant environments.

a–b, Data from ref. 40 are reanalyzed to generate non-synonymous SNV frequency trajectories in five representative populations evolving in an antagonistic changing environment (a) and in five populations evolving in corresponding constant environments (b). In (a), the environment changed every 224 generations from one to the next of the five environments shown in (b). In (a), each line shows the allele frequency trajectory of a non-synonymous mutation at the beginning of the experimental evolution, four time points marking the four environmental changes, and the end of the experimental evolution. In (b), each line shows the allele frequency trajectory of a non-synonymous mutation at the same time points as in (a). Trajectories of all non-synonymous SNVs in each population are displayed, and different SNVs are shown using different colors.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Results from a SLiM simulation mimicking the asexual, diploid yeast experimental evolution.

Ne = 4×105, genome size = 1.6×105, mutation rate = 1×10−7 per site per generation, and other conditions followed the basal AdapTrack and Adaptive models. The simulation was run for 800 generations, and the environment changed every 80 generations under AdapTrack but remained constant under Adaptive. a, Fractions of “substitutions” belonging to various categories, where “substitutions” refer to mutational differences between the progenitor and a single sampled individual at the end of the simulation. b, Ω computed from the “substitutions” above defined. Shown are the results from 100 simulation replications. In (b), the lower and upper edges of a box represent the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles, respectively, the horizontal line inside the box indicates the median, the whiskers extend to the most extreme values inside inner fences from Q1 – 1.5 × (Q3 – Q1) to Q3 + 1.5 × (Q3 – Q1), and the dots show outliers.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Additional comparisons of beneficial substitutions and ω between yeast experimental evolution in constant and changing environments.

a–b, The fraction of beneficial substitutions is significantly lower in changing environments than in corresponding constant environments. Same as Fig. 5c, except that only non-synonymous SNVs, nonsense SNVs, and frame shifting indels (a), or only non-synonymous SNVs (b) are considered in identifying beneficial substitutions. c, The fraction of beneficial substitutions in a changing environment increases with the similarity among the 10 media making up the changing environment. Each dot represents one of the 10 changing environments. Spearman’s correlation and associated one-tailed P-value are presented. d–f, Same as Fig. 5c except that the 12 potentially contaminated populations are excluded. Results are obtained when all substitution types (d), only non-synonymous SNVs, nonsense SNVs, and frame shifting indels (e), or only non-synonymous SNVs (f) are considered in identifying beneficial substitutions. g, ω is significantly lower in changing environments than in constant environments, as in Fig. 5d, except that the 12 potentially contaminated populations are excluded.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Results of SLiM simulations under AdapTrack and other models of fluctuating selection.

a-d, Derived allele frequency spectra (a), polymorphisms (b), substitutions (c), and Ω (d). Under the quasi-neutral model (QuasiNeu), beneficial mutations are subject to fluctuating selection with zero expected selection coefficients across environments. Under the fluctuating positive selection model (FluPosSel), beneficial mutations are subject to fluctuating selection with positive expected selection coefficients across environments.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Signals of selective sweeps in SLiM simulated data.

a-e, Distributions of Tajima’s D (a), Fu and Li’s D (b), Fay and Wu’s H (c), Zeng et al.’s E (d), and Garud et al.’s H12 (e) for populations simulated under five different models. Each distribution, presented as a violin plot, is based on the aggregated data from 20 timepoints of each of 30 simulation replications. A t-test is conducted between Neutral and AdapTrack (inf env) or AdapTrack (20 env) as well as between Adaptive and AdapTrack (inf env) or AdapTrack (20 env). Here, “inf env” stands for infinite number of environments whereas “20 env” stands for 20 rotating environments. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.0005. In the violin plot, the white dot represents the median, the dark rectangular spans from the first (Q1) to third (Q3) quartile, and the dark vertical line represents the range of the distribution after removing outliers that lie outside the domain from Q1 – 1.5 × (Q3 – Q1) to Q3 + 1.5 × (Q3 – Q1).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Results of SLiM simulations under AdapTrack with temporal vs. spatial heterogeneity in fitness effects of mutations.

a-d, Derived allele frequency spectra (a), polymorphisms (b), substitutions (c), and Ω (d). We consider the average fitness across all environments when classifying beneficial and deleterious polymorphisms/substitutions under the spatial heterogeneity model. The results of the simulation of temporal heterogeneity are from Fig. 2a-d.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary discussion.

Supplementary Data 1

Inferred non-synonymous substitution rate relative to the neutral expectation (Ω) and inferred fraction of non-synonymous substitutions that are beneficial (α), under various empirical DFEs of non-synonymous mutations in sexual and asexual populations.

Supplementary Tables 1–5

Supplementary Tables 1–5.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, S., Chen, P., Shen, X. et al. Adaptive tracking with antagonistic pleiotropy results in seemingly neutral molecular evolution. Nat Ecol Evol 9, 2358–2373 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02887-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02887-1

This article is cited by

-

Deep mutational scans clarify the record of evolution

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025)