Abstract

Despite the growing abundance of sequenced animal genomes, we only have detailed knowledge of regulatory organization for a handful of lineages, particularly flies and vertebrates. These two taxa show contrasting trends in the molecular mechanisms of 3D chromatin organization and long-term evolutionary dynamics of cis-regulatory element (CRE) conservation. Here we study the evolution and organization of the regulatory genome of echinoderms, a lineage whose phylogenetic position and relatively slow molecular evolution have proven particularly useful for evolutionary studies. We generated new reference genome assemblies for two species belonging to two different echinoderm classes: the purple sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus and the bat sea star Patiria miniata using PacBio and HiC data and characterize their 3D chromatin architecture. We show that these echinoderms have TAD-like domains that, such as in flies, do not seem to be associated with CTCF motif orientation. We systematically profiled CREs during sea star and sea urchin development using ATAC-seq, comparing their regulatory logic and dynamics over multiple developmental stages. Finally, our analysis of sea urchin and sea star CRE evolution across multiple evolutionary distances and timescales showed several thousand elements conserved for hundreds of millions of years, revealing a vertebrate-like pattern of CRE evolution that probably constitutes an ancestral property of the regulatory evolution of animals.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Genome assemblies used in this work are publicly available at the NCBI genome database GenBank with accession numbers GCA_015706575.1 (P. miniata) and GCA_000002235.4 (S. purpuratus). The HiC (GSE281901) and ATAC-seq (GSE280529) raw and processed sequencing data were deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession code of the SuperSeries GSE281904, with the exception of ATAC-seq data in S. purpuratus at 48 hpf that were deposited in GSE186363. Files and share links for viewing the multiple genome alignment are available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30506378 (ref. 147).

References

Sebé-Pedrós, A. et al. The dynamic regulatory genome of capsaspora and the origin of animal multicellularity. Cell 165, 1224–1237 (2016).

Berná, L. & Alvarez-Valin, F. Evolutionary genomics of fast evolving tunicates. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 1724–1738 (2014).

Harmston, N. et al. Topologically associating domains are ancient features that coincide with Metazoan clusters of extreme noncoding conservation. Nat. Commun. 8, 441 (2017).

Kapusta, A., Suh, A. & Feschotte, C. Dynamics of genome size evolution in birds and mammals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E1460–E1469 (2017).

Moriyama, Y. & Koshiba-Takeuchi, K. Significance of whole-genome duplications on the emergence of evolutionary novelties. Briefings Funct. Genomics 17, 329–338 (2018).

Martín-Durán, J. M. et al. Conservative route to genome compaction in a miniature annelid. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 231–242 (2021).

Marlétaz, F. et al. Amphioxus functional genomics and the origins of vertebrate gene regulation. Nature 564, 64–70 (2018).

Zimmermann, B. et al. Topological structures and syntenic conservation in sea anemone genomes. Nat. Commun. 14, 8270 (2023).

Schwaiger, M. et al. Evolutionary conservation of the eumetazoan gene regulatory landscape. Genome Res. 24, 639–650 (2014).

modENCODE Consortium et al. Identification of functional elements and regulatory circuits by Drosophila modENCODE. Science 330, 1787–1797 (2010).

Martín-Zamora, F. M. et al. Annelid functional genomics reveal the origins of bilaterian life cycles. Nature 615, 105–110 (2023).

Pérez-Posada, A. et al. Hemichordate cis-regulatory genomics and the gene expression dynamics of deuterostomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02562-x (2024).

Irimia, M. et al. Extensive conservation of ancient microsynteny across metazoans due to cis-regulatory constraints. Genome Res. 22, 2356–2367 (2012).

Acemel, R. D. & Lupiáñez, D. G. Evolution of 3D chromatin organization at different scales. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 78, 102019 (2023).

Irimia, M. & Maeso, I. in Old Questions and Young Approaches to Animal Evolution (eds Martín-Durán, J. M. & Vellutini, B. C.) 175–207 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Simakov, O. et al. Insights into bilaterian evolution from three spiralian genomes. Nature 493, 526–531 (2013).

Wong, E. S. et al. Deep conservation of the enhancer regulatory code in animals. Science 370, eaax8137 (2020).

Kim, I. V. et al. Chromatin loops are an ancestral hallmark of the animal regulatory genome. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08960-w (2025).

Rao, S. S. P. et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680 (2014).

de Wit, E. et al. CTCF binding polarity determines chromatin looping. Mol. Cell 60, 676–684 (2015).

Kaaij, L. J. T., Mohn, F., van der Weide, R. H., de Wit, E. & Bühler, M. The ChAHP complex counteracts chromatin looping at CTCF sites that emerged from SINE expansions in mouse. Cell 178, 1437–1451.e14 (2019).

Franke, M. et al. CTCF knockout in zebrafish induces alterations in regulatory landscapes and developmental gene expression. Nat. Commun. 12, 5415 (2021).

Cavalheiro, G. R. et al. CTCF, BEAF-32, and CP190 are not required for the establishment of TADs in early Drosophila embryos but have locus-specific roles. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade1085 (2023).

Kaushal, A. et al. CTCF loss has limited effects on global genome architecture in Drosophila despite critical regulatory functions. Nat. Commun. 12, 1011 (2021).

Maeso, I. & Tena, J. J. Favorable genomic environments for cis-regulatory evolution: a novel theoretical framework. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 57, 2–10 (2016).

Nord, A. S. et al. Rapid and pervasive changes in genome-wide enhancer usage during mammalian development. Cell 155, 1521–1531 (2013).

Paris, M. et al. Extensive divergence of transcription factor binding in Drosophila embryos with highly conserved gene expression. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003748 (2013).

Vierstra, J. et al. Mouse regulatory DNA landscapes reveal global principles of cis-regulatory evolution. Science 346, 1007–1012 (2014).

Villar, D., Flicek, P. & Odom, D. T. Evolution of transcription factor binding in metazoans—mechanisms and functional implications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 221–233 (2014).

Villar, D. et al. Enhancer evolution across 20 mammalian species. Cell 160, 554–566 (2015).

Glazov, E. A., Pheasant, M., McGraw, E. A., Bejerano, G. & Mattick, J. S. Ultraconserved elements in insect genomes: a highly conserved intronic sequence implicated in the control of homothorax mRNA splicing. Genome Res. 15, 800–808 (2005).

He, Q. et al. High conservation of transcription factor binding and evidence for combinatorial regulation across six Drosophila species. Nat. Genet. 43, 414–420 (2011).

Tan, G., Polychronopoulos, D. & Lenhard, B. CNEr: a toolkit for exploring extreme noncoding conservation. PLoS Comput. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006940 (2019).

Vavouri, T., Walter, K., Gilks, W. R., Lehner, B. & Elgar, G. Parallel evolution of conserved non-coding elements that target a common set of developmental regulatory genes from worms to humans. Genome Biol. 8, R15 (2007).

Royo, J. L. et al. Transphyletic conservation of developmental regulatory state in animal evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14186–14191 (2011).

Clarke, S. L. et al. Human developmental enhancers conserved between deuterostomes and protostomes. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002852 (2012).

Frith, M. C. & Ni, S. DNA conserved in diverse animals since the Precambrian controls genes for embryonic development. Mol. Biol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msad275 (2023).

Harmston, N., Baresic, A. & Lenhard, B. The mystery of extreme non-coding conservation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 368, 20130021 (2013).

Pennacchio, L. A., Bickmore, W., Dean, A., Nobrega, M. A. & Bejerano, G. Enhancers: five essential questions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 288–295 (2013).

Woolfe, A. et al. Highly conserved non-coding sequences are associated with vertebrate development. PLoS Biol. 3, e7 (2005).

Pennacchio, L. A. et al. In vivo enhancer analysis of human conserved non-coding sequences. Nature 444, 499–502 (2006).

Wang, J., Lee, A. P., Kodzius, R., Brenner, S. & Venkatesh, B. Large number of ultraconserved elements were already present in the jawed vertebrate ancestor. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 487–490 (2009).

Lee, A. P., Kerk, S. Y., Tan, Y. Y., Brenner, S. & Venkatesh, B. Ancient vertebrate conserved noncoding elements have been evolving rapidly in teleost fishes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 1205–1215 (2011).

Thompson, A. W. et al. The bowfin genome illuminates the developmental evolution of ray-finned fishes. Nat. Genet. 53, 1373–1384 (2021).

Najle, S. R. et al. Stepwise emergence of the neuronal gene expression program in early animal evolution. Cell 186, 4676–4693.e29 (2023).

Sea Urchin Genome Sequencing Consortium et al. The genome of the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Science 314, 941–952 (2006).

Simakov, O. et al. Hemichordate genomes and deuterostome origins. Nature 527, 459–465 (2015).

Lewin, T. D., Liao, I. J.-Y. & Luo, Y.-J. Conservation of bilaterian genome structure is the exception, not the rule. Genome Biol. 26, 247 (2025).

Gildor, T., Hinman, V. & Ben-Tabou-De-Leon, S. Regulatory heterochronies and loose temporal scaling between sea star and sea urchin regulatory circuits. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 61, 347–356 (2017).

Annunziata, R., Andrikou, C., Perillo, M., Cuomo, C. & Arnone, M. I. Development and evolution of gut structures: from molecules to function. Cell Tissue Res 377, 445–458 (2019).

Voronov, D. et al. Integrative multi-omics increase resolution of the sea urchin posterior gut gene regulatory network at single-cell level. Development https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.202278 (2024).

Marlétaz, F. et al. Analysis of the P. lividus sea urchin genome highlights contrasting trends of genomic and regulatory evolution in deuterostomes. Cell Genomics 3, 100295 (2023).

Eno, C. C., Böttger, S. A. & Walker, C. W. Methods for karyotyping and for localization of developmentally relevant genes on the chromosomes of the purple sea urchin, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Biol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1086/BBLv217n3p306 (2009).

Saotome, K. & Komatsu, M. Chromosomes of Japanese starfishes. Zool. Sci. 19, 1095–1103 (2002).

Byrne, M. Life history diversity and evolution in the Asterinidae. Integr. Comp. Biol. 46, 243–254 (2006).

Colombera, D. & Tagliaferri, F. The male chromosomes of five species of echinoderms together with some technical hints. Caryologia 39, 347–352 (2014).

Thibaud-Nissen, F. et al. P8008 The NCBI eukaryotic genome annotation pipeline. J. Anim. Sci. 94, 184 (2016).

Dixon, J. R. et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485, 376–380 (2012).

Nora, E. P. et al. Spatial partitioning of the regulatory landscape of the X-inactivation centre. Nature 485, 381–385 (2012).

Sexton, T. et al. Three-dimensional folding and functional organization principles of the Drosophila genome. Cell 148, 458–472 (2012).

Schmidbaur, H. et al. Emergence of novel cephalopod gene regulation and expression through large-scale genome reorganization. Nat. Commun. 13, 2172 (2022).

Huang, Z. et al. Three amphioxus reference genomes reveal gene and chromosome evolution of chordates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2201504120 (2023).

Marlétaz, F. et al. The little skate genome and the evolutionary emergence of wing-like fins. Nature 616, 495–503 (2023).

Kaaij, L. J. T., van der Weide, R. H., Ketting, R. F. & de Wit, E. Systemic loss and gain of chromatin architecture throughout zebrafish development. Cell Rep. 24, 1–10.e4 (2018).

Vargas-Chávez, C. et al. An episodic burst of massive genomic rearrangements and the origin of non-marine annelids. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 9, 1263–1279 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the northern Pacific seastar Asterias amurensis. Sci. Data https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02688-w (2023).

Watanabe, K. et al. The crucial role of CTCF in mitotic progression during early development of sea urchin. Dev. Growth Differ. 65, 395–407 (2023).

Pallarès-Albanell, J. et al. Gene regulatory dynamics during the development of a paleopteran insect, the mayfly Cloeon dipterum. Development https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.203017 (2024).

de-Leon, S. B.-T. & Davidson, E. H. Information processing at the foxa node of the sea urchin endomesoderm specification network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 10103–10108 (2010).

Nam, J., Dong, P., Tarpine, R., Istrail, S. & Davidson, E. H. Functional cis-regulatory genomics for systems biology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3930–3935 (2010).

Oliveri, P., Walton, K. D., Davidson, E. H. & McClay, D. R. Repression of mesodermal fate by foxa, a key endoderm regulator of the sea urchin embryo. Development 133, 4173–4181 (2006).

Hinman, V. F. & Davidson, E. H. Evolutionary plasticity of developmental gene regulatory network architecture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19404–19409 (2007).

Dylus, D. V. et al. Large-scale gene expression study in the ophiuroid Amphiura filiformis provides insights into evolution of gene regulatory networks. Evodevo 7, 2 (2016).

Hore, T. A., Deakin, J. E. & Ja, M. G. The evolution of epigenetic regulators CTCF and BORIS/CTCFL in amniotes. PLoS Genet. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000169 (2008).

Kadota, M., Yamaguchi, K., Hara, Y. & Kuraku, S. Early vertebrate origin of CTCFL, a CTCF paralog, revealed by proximity-guided shark genome scaffolding. Sci. Rep. 10, 14629 (2020).

Mongiardino Koch, N. et al. Phylogenomic analyses of echinoid diversification prompt a re-evaluation of their fossil record. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.72460 (2022).

Linchangco, G. V. Jr et al. The phylogeny of extant starfish (Asteroidea: Echinodermata) including Xyloplax, based on comparative transcriptomics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 115, 161–170 (2017).

Villier, L. et al. Superstesaster promissor gen. et sp. nov., a new starfish (Echinodermata, Asteroidea) from the Early Triassic of Utah, USA, filling a major gap in the phylogeny of asteroids. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 16, 395–415 (2018).

Deline, B. et al. Evolution and development at the origin of a phylum. Curr. Biol. 30, 1672–1679.e3 (2020).

Telford, M. J., Budd, G. E. & Philippe, H. Phylogenomic insights into animal evolution. Curr. Biol. 25, R876–R887 (2015).

Cunningham, J. A., Liu, A. G., Bengtson, S. & Donoghue, P. C. J. The origin of animals: can molecular clocks and the fossil record be reconciled?. Bioessays 39, 1–12 (2017).

Odom, D. T. et al. Tissue-specific transcriptional regulation has diverged significantly between human and mouse. Nat. Genet. 39, 730–732 (2007).

Schmidt, D. et al. Five-vertebrate ChIP-seq reveals the evolutionary dynamics of transcription factor binding. Science 328, 1036–1040 (2010).

Ksepka, D. T. et al. The fossil calibration database—a new resource for divergence dating. Syst. Biol. 64, 853–859 (2015).

Sebé-Pedrós, A. & Ruiz-Trillo, I. Evolution and classification of the T-box transcription factor family. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 122, 1–26 (2017).

Ben-Tabou de-Leon, S., Su, Y.-H., Lin, K.-T., Li, E. & Davidson, E. H. Gene regulatory control in the sea urchin aboral ectoderm: spatial initiation, signaling inputs, and cell fate lockdown. Dev. Biol. 374, 245–254 (2013).

Gross, J. M., Peterson, R. E., Wu, S.-Y. & McClay, D. R. LvTbx2/3: a T-box family transcription factor involved in formation of the oral/aboral axis of the sea urchin embryo. Development 130, 1989–1999 (2003).

Valencia, J. E., Feuda, R., Mellott, D. O., Burke, R. D. & Peter, I. S. Ciliary photoreceptors in sea urchin larvae indicate pan-deuterostome cell type conservation. BMC Biol. 19, 257 (2021).

Fresques, T. M. & Wessel, G. M. Nodal induces sequential restriction of germ cell factors during primordial germ cell specification. Development https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.155663 (2018).

Paganos, P., Voronov, D., Musser, J. M., Arendt, D. & Arnone, M. I. Single-cell RNA sequencing of the Strongylocentrotus purpuratus larva reveals the blueprint of major cell types and nervous system of a non-chordate deuterostome. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.70416 (2021).

Meyer, A., Ku, C., Hatleberg, W. L., Telmer, C. A. & Hinman, V. New hypotheses of cell type diversity and novelty from orthology-driven comparative single cell and nuclei transcriptomics in echinoderms. eLife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.80090 (2023).

Nora, E. P. et al. Targeted degradation of CTCF decouples local insulation of chromosome domains from genomic compartmentalization. Cell 169, 930–944.e22 (2017).

Rao, S. S. P. et al. Cohesin loss eliminates all loop domains. Cell 171, 305–320.e24 (2017).

Niu, L. et al. Three-dimensional folding dynamics of the Xenopus tropicalis genome. Nat. Genet. 53, 1075–1087 (2021).

Cui, M., Vielmas, E., Davidson, E. H. & Peter, I. S. Sequential response to multiple developmental network circuits encoded in an intronic cis-regulatory module of sea urchin hox11/13b. Cell Rep. 19, 364–374 (2017).

Damle, S. & Davidson, E. H. Precise cis-regulatory control of spatial and temporal expression of the alx-1 gene in the skeletogenic lineage of S. purpuratus. Dev. Biol. 357, 505–517 (2011).

Lee, P. Y., Nam, J. & Davidson, E. H. Exclusive developmental functions of gatae cis-regulatory modules in the Strongylocentrorus purpuratus embryo. Dev. Biol. 307, 434–445 (2007).

Livi, C. B. & Davidson, E. H. Regulation of spblimp1/krox1a, an alternatively transcribed isoform expressed in midgut and hindgut of the sea urchin gastrula. Gene Expr. Patterns 7, 1–7 (2007).

Yuh, C.-H. et al. Patchy interspecific sequence similarities efficiently identify positive cis-regulatory elements in the sea urchin. Dev. Biol. 246, 148–161 (2002).

Irie, N. & Kuratani, S. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals vertebrate phylotypic period during organogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2, 248 (2011).

Hu, H. et al. Constrained vertebrate evolution by pleiotropic genes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1722–1730 (2017).

Duboule, D. Temporal colinearity and the phylotypic progression: a basis for the stability of a vertebrate Bauplan and the evolution of morÿphologies through heterochrony. Development 1994, 135–142 (1994).

Bogdanovic, O. et al. Dynamics of enhancer chromatin signatures mark the transition from pluripotency to cell specification during embryogenesis. Genome Res. 22, 2043–2053 (2012).

Buono, L. et al. Conservation of cis-regulatory syntax underlying deuterostome gastrulation. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13131121 (2024).

Skvortsova, K. et al. Active DNA demethylation of developmental cis-regulatory regions predates vertebrate origins. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abn2258 (2022).

Gonzalez, P., Hauck, Q. C. & Baxevanis, A. D. Conserved noncoding elements evolve around the same genes throughout metazoan evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 16, evae052 (2024).

Koren, S. et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27, 722–736 (2017).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Juicebox.js provides a cloud-based visualization system for Hi-C data. Cell Syst. 6, 256–258.e1 (2018).

Knight, P. A. & Ruiz, D. A fast algorithm for matrix balancing. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 33, 1029–1047 (2012).

Kruse, K., Hug, C. B. & Vaquerizas, J. M. FAN-C: a feature-rich framework for the analysis and visualisation of chromosome conformation capture data. Genome Biol. 21, 303 (2020).

Crane, E. et al. Condensin-driven remodelling of X chromosome topology during dosage compensation. Nature 523, 240–244 (2015).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Katoh, K., Rozewicki, J. & Yamada, K. D. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings Bioinf. 20, 1160–1166 (2017).

Larsson, A. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 30, 3276–3278 (2014).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2014).

Hoang, D. T., Chernomor, O., von Haeseler, A., Minh, B. Q. & Vinh, L. S. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 518–522 (2017).

Heger, P., Marin, B., Bartkuhn, M., Schierenberg, E. & Wiehe, T. The chromatin insulator CTCF and the emergence of metazoan diversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 17507–17512 (2012).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589 (2017).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296 (2021).

Armstrong, J. et al. Progressive cactus is a multiple-genome aligner for the thousand-genome era. Nature 587, 246–251 (2020).

Arshinoff, B. I. et al. Echinobase: leveraging an extant model organism database to build a knowledgebase supporting research on the genomics and biology of echinoderms. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D970–D979 (2022).

Buenrostro, J. D., Giresi, P. G., Zaba, L. C., Chang, H. Y. & Greenleaf, W. J. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods 10, 1213–1218 (2013).

Magri, M. S. et al. Assaying chromatin accessibility using ATAC-Seq in invertebrate chordate embryos. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 7, 372 (2019).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

Li, Q., Brown, J. B., Huang, H. & Bickel, P. J. Measuring reproducibility of high-throughput experiments. Ann. Appl. Stat. 5, 1752–1779 (2011).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Heinz, S. et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589 (2010).

Ye, T. et al. seqMINER: an integrated ChIP-seq data interpretation platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e35 (2011).

Ramírez, F. et al. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W160–W165 (2016).

Hickey, G., Paten, B., Earl, D., Zerbino, D. & Haussler, D. HAL: a hierarchical format for storing and analyzing multiple genome alignments. Bioinformatics 29, 1341–1342 (2013).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3176 (2015).

Martínez-Redondo, G. I. et al. FANTASIA leverages language models to decode the functional dark proteome across the animal tree of life. Commun. Biol. 8, 1227 (2025).

Alexa, A. & Rahnenfuhrer, J. topGO: Enrichment Analysis for Gene Ontology (Bioconductor, 2025); https://doi.org/10.18129/B9.bioc.topGO

Untergasser, A. et al. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e115 (2012).

Xiong, A.-S. et al. PCR-based accurate synthesis of long DNA sequences. Nat. Protoc. 1, 791–797 (2006).

Arnone, M. I., Dmochowski, I. J. & Gache, C. in Development of Sea Urchins, Ascidians, and Other Invertebrate Deuterostomes: Experimental Approaches (eds Ettensohn, C. A. et al.) 621–652 (Academic Press, 2004).

Perillo, M., Paganos, P., Spurrell, M., Arnone, M. I. & Wessel, G. M. Methodology for whole mount and fluorescent RNA in situ hybridization in echinoderms: single, double, and beyond. Methods Mol. Biol. 2219, 195–216 (2021).

Paganos, P. et al. FISH for all: a fast and efficient fluorescent hybridization (FISH) protocol for marine embryos and larvae. Front Physiol. 13, 878062 (2022).

Foley, S. Files for viewing multiple genome alignment of marine invertebrates from ‘Deep conservation of cis-regulatory elements and chromatin organization in echinoderms uncover ancestral regulatory features of animal genomes’. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30506378 (2025).

Brasó-Vives, M. et al. Parallel evolution of amphioxus and vertebrate small-scale gene duplications. Genome Biol. 23, 1–24 (2022).

Saudemont, A. et al. Ancestral regulatory circuits governing ectoderm patterning downstream of Nodal and BMP2/4 revealed by gene regulatory network analysis in an echinoderm. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001259 (2010).

Acknowledgements

I.M., M.S.M., M.P. and M.F.-M. are supported by grants PID2021-128728NB-I00 and CNS2022-136105 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ‘ERDF/EU’ and ‘European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR’. I.M. was also funded by grants RYC-2016-20089 and PGC2018-099392-A-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, ‘ERDF A way of making Europe’ and ‘ESF Investing in your future’. M.S.M. was granted a fellowship of the Program for the Training of Researchers (BES-2014-068494), and M.F.M. holds a FPU fellowship (FPU20/02733), funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MICIU). J.L.G.-S. was supported by the European Research Council (grant agreement number 740041) and the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (grant number PID2019-103921GB-I00). P.M.M.-G. was funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from Junta de Andalucía (DOC_00397). V.F.H., S.F., G.A.C. and C.K. were supported by grant P41HD09583106 funded by the National Institutes of Health. Computing was supported via the Bridges2 system by allocation request BIO210137 awarded to S.F. D.V., M.L.R. and C.C. were supported by the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn PhD fellowships. This work was supported by the H2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Innovative Training Network EvoCELL (grant number 766053 to M.I.A. and fellowship to P.P.). We thank D. Burguera and I. Almudi for helpful discussions and F. Mantica for advice in orthogroup inference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DNA library preparation: G.A.C. S. purpuratus genome assembly: G.A.C. and S.F. P. miniata genome assembly: C.K. and S.F. Gene annotation coordination: S.F. ATAC-seq experiments: M.S.M., D.V., J.R. and C.C. ATAC-seq data analyses: M.S.M. and D.V. TF motif analyses: M.S.M., P.N.F. and P.M.M.-G. HiC experiments: M.F. and R.D.A. Preparation of samples for HiC: D.V., C.C. and P.P. HiC data analyses: J.M.S.-P. and P.M.M.-G. Gene family evolution analyses: M.F.-M. Multi-species genome alignments: S.F. and A.G.-G. Sequence conservation analyses: M.S.M., A.G.-G., R.D.A. and M.P. Conservation of pCREs target genes: M.F.-M. and M.P. Preparation of constructs and cis-regulatory reporter assays: D.V., P.P., M.L.R. and M.F.-M. Microinjection experiments: M.I.A. Whole mount in situ hybridization: P.P. Conceptualization and design of the project: I.M., M.I.A., J.L.G.-S. and V.F.H. Project coordination and supervision: I.M., M.I.A. and V.F.H. Funding acquisition: J.L.G.-S., V.F.H., M.I.A. and I.M. Figure preparation: M.S.M., D.V., S.F., P.M.M.-G., J.M.S.-P., M.F.-M., P.P., M.L.R., I.M. and M.I.A. Paper writing–original draft: M.S.M., D.V., S.F. and I.M. Paper writing–review and editing: I.M., D.V., M.S.M., S.F., M.I.A., V.F.H., C.K., J.M.S.-P., P.F., R.D.A., P.P. and M.F.-M. All authors revised and approved the paper. Animal silhouettes for A. planci, P. miniata and A. japonica were drawn by I.M. Sea star and sea urchin embryos were drawn by M.I.A.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks José Martín-Durán and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

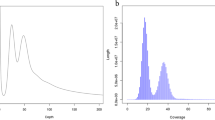

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison of current and previous assembly statistics.

a, BUSCO statistics of current and previous genome assemblies. b, Assembly statistics of the two new genomes along with their older versions for comparison, generated with the assembly-stats perl package. c, d, Snailplots of general metrics (scaffold total length, scaffold count, longest scaffold, N50 and N90 values, and base compositions) of the new assemblies of the bat sea star (GCA_015706575.1) (c, upper panel) and purple sea urchin (GCA_000002235.4) (d, upper panel) versus those of previous assemblies (lower panels). e, f, HiC genome-wide contact maps of the bat sea star (e) and purple sea urchin (f) assemblies.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Chromatin domains and loops in echinoderms.

a, Heatmaps showing normalized HiC signal at 10-kb resolution in A. amurensis. Insulation scores and computationally called TAD boundaries are plotted below the heatmaps. b, Aggregate analysis of the observed versus expected HiC signal around TAD boundaries called at 10-kb resolution in A. amurensis (top) and D. melanogaster (bottom). c, Boxplots showing the distribution of boundary scores (left) and TAD sizes (right) in P. miniata (boundaries n = 2,108, TADs n = 2042), S. purpuratus (boundaries n = 3,009, TADs n = 2880), A. amurensis (boundaries n = 1,596, TADs n = 1566) and D. melanogaster (boundaries n = 476, TADs n = 484). d, Aggregate peak analyses of HiC loops in P. miniata, S. purpuratus, A. amurensis and D. melanogaster. The observed vs. expected HiC signal is shown. e, Boxplots showing the distribution of loop ranges in P. miniata, S. purpuratus, A. amurensis and D. melanogaster. Number of loops in each species as in d. f, Normalized number of ATAC-seq peaks harboring CTCF motifs around HiC loops in P. miniata (left), S. purpuratus (middle) and D. rerio (right). Shuffle control is shown per each graph. Boxplots in c and e show center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5× interquartile range; notches, 95% confidence interval of the median.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Examples of ancient conserved microsyntenic blocks located within TAD boundaries.

Sea star (left panels) and sea urchin (right panels) genomic regions around four developmental genes included within ancient microsyntenic blocks (Tbx2/3, Foxa and Pax1/9, and Egr). From top to bottom: heatmaps showing normalized HiC signal at 10-kb resolution in late gastrula sea star and sea urchin embryos, ATAC-seq signal at late gastrula stage embryos of both species, IDR ATAC-seq peaks (pCREs), conserved ATAC-seq peaks (merging peaks conserved at the Valvatida+Asteroidea strata and Odontophora+Echinoidea strata), gene models (with those included within the conserved syntenic blocks colored in green), insulation scores and computationally called TAD boundaries. Note that the conserved block containing Foxa and Pax1/9 is split in two in the case of sea urchin.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cohesin and CTCF phylogeny and conservation.

a, ML phylogenetic tree of cohesin subunit SA1-3 proteins. Sponge SA proteins were used as outgroups. b, ML phylogenetic tree of CTCF, including the tetrapod-specific paralog CTCFL (also known as BORIS), the outgroup (OG) branch includes the insect proteins CROOKED LEGS, a zinc finger containing family of transcription factors. c, Alignment of CTCF proteins from different bilaterians, showing the region containing its putatively ancestral 11 zinc finger domains, where ambulacrarian species have lost one or two domains. Silhouettes from PhyloPic under a Creative Commons license: sponge (Staurocalyptus solidus), whale shark and Onychophora (CC0 1.0) and sea star (CC BY 3.0).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Functional assays of foxa1 pCREs.

a, Screenshot of sea urchin UCSC browser with ATAC-seq tracks around the foxa1 (LOC110977664) gene and pCREs. b, Relative GFP expression levels driven by foxa1 CREs in sea urchin embryos at mesenchyme blastula stage. c, Scoring table for embryos injected with foxa1 pCRE-Tag constructs at mesenchyme blastula stage. This highlights the distribution of embryos with expression in both ectoderm and endoderm, only ectoderm or only endoderm, as well as the ones exhibiting GFP expression in regions ectopic to foxa1 expression. This was also concordant with scoring done for the FIJ concatenate69 since the majority of the expression is in the endoderm with oral ectoderm expression exhibited by fewer embryos.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Evolutionary strata and developmental dynamics of sea urchin and sea star pCREs.

a, Accession numbers of the genome assemblies included in the alignments. b, Counts of pCREs according to their evolutionary strata. c, Genome browser screenshots around the P. miniata pbx1a (LOC119720117, top panel) and the S. purpuratus six1 (LOC110974175, lower panel) genes showing ATAC-seq tracks from different developmental stages (in orange and purple, respectively), IDR peaks (orange and purple bars) and gene models (dark blue). A conserved Asteroidea pCRE (red bar) with late developmental dynamics and Deuterostome and Odontophora pCREs (green bars) with early developmental dynamics are highlighted with gray boxes.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Sequence and accessibility conservation of transphyletic pCREs and GO term enrichments of their associated genes.

a, Venn diagram with the number of conserved transphyletic pCREs present in each species. pCREs ancestral to deuterostomes and to ambulacrarians are shadowed in blue and orange, respectively. n.a. (not applicable) labels pCRE sharing between species pairs not addressed in this plot: those between amphioxus and hemichordates, which were not directly investigated in the present work, and pCREs shared between sea star and sea urchin, where shared conserved pCREs from the echinoderm stratum were not included to avoid confusions with transphyletic pCREs. b, Venn diagram with the number of transphyletic pCREs showing shared chromatin accessibility in sea star, sea urchin and amphioxus embryos. Deuterostome and ambulacrarian pCREs are indicated in black and gray, respectively. c–e, Top ten significantly enriched GO terms of genes associated with all transphyletic pCREs (c), and with the subsets of pCREs ancestral to deuterostomes (d) and ambulacrarians. Biological Process and Molecular Function ontologies are indicated in the left and right panels, respectively. B. lanceolatum drawing adapted from ref. 7 under a Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0). Hemichordate (Balanoglossus) silhouette from PhyloPic under a Creative Commons license (CC0 1.0).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Functional assays of Tbx2/3 deeply conserved CRE.

a, Numbers of embryos examined in functional assays with the two different CREs and percentages of expression in S. purpuratus (Sp), P. lividus (Pl), P. miniata (Pm). Microinjection experiments were performed using at least two independent batches of embryos and for each experiment at least 30 embryos were analyzed. b, Expression pattern of tbx2/3 by fluorescent in situ hybridization in S. purpuratus late gastrula (top left, focus on the ectoderm) and functional assays of S. purpuratus and P. miniata CREs in different species (S. purpuratus (Sp), P. lividus (Pl), P. miniata (Pm)) by GFP fluorescence. Scale bar 20 µm; lv, lateral view; vv, ventral view. c, The dot plots highlight the expression of endogenous tbx2/3 as detected from scRNA-seq data analysis of gastrula stages in S. purpuratus51, left column, and from snRNA-seq data analysis of gastrula stages in P. miniata91, right column.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data 1

MAFFT alignment of SA1-3 proteins.

Supplementary Data 2

MAFFT alignment of CTCF and CROL proteins.

Supplementary Data 3

SA1-3 tree.

Supplementary Data 4

CTCF tree.

Supplementary Data 5

Orthogroups used to assess conservation of pCREs associated genes.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–14.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Magri, M.S., Voronov, D., Foley, S. et al. Deep conservation of cis-regulatory elements and chromatin organization in echinoderms uncover ancestral regulatory features of animal genomes. Nat Ecol Evol 10, 355–371 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02941-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02941-y