Abstract

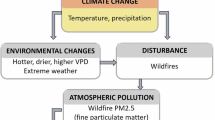

Wildfire activity has increased in the USA and is projected to accelerate under future climate change1,2,3. However, our understanding of the impacts of climate change on wildfire activity, smoke and health outcomes remains highly uncertain because of the difficulty of modelling the causal chain from climate to wildfire to air pollution and health. Here we quantify the mortality burden in the USA due to wildfire smoke fine particulate matter (PM2.5) under climate change. We construct an ensemble of statistical and machine learning models that link climate to wildfire smoke PM2.5 and empirically estimate smoke PM2.5–mortality relationships using data on all recorded deaths in the USA. We project that smoke PM2.5 could result in 71,420 excess deaths (95% confidence interval: 34,930–98,430) per year by 2050 under a high-warming scenario (shared socioeconomic pathway scenario 3-7.0, SSP3-7.0)—a 73% increase relative to the estimated 2011–2020 average annual excess deaths from smoke. Cumulative excess deaths from smoke PM2.5 could reach 1.9 million between 2026 and 2055. We find evidence for mortality impacts of smoke PM2.5 that last up to 3 years after exposure. When monetized, climate-driven smoke deaths result in economic damages that exceed existing estimates of climate-driven damages from all other causes combined in the USA4,5. Our research suggests that the health impacts of climate-driven wildfire smoke could be among the most important and costly consequences of a warming climate in the USA.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data needed to replicate results and main text figures are available in a public repository at Zenodo92 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16855665), except for county-level mortality data for low-population counties, which were obtained through application to the National Center for Health Statistics. Although we cannot share the full mortality data that we used in the analysis, we released a dataset that allows replication of our smoke–mortality model using public mortality data derived from CDC WONDER.

Code availability

R code to replicate results and main text figures is available at Zenodo92 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16855665).

References

Abatzoglou, J. T. & Williams, A. P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11770–11775 (2016).

Diffenbaugh, N. S., Konings, A. G. & Field, C. B. Atmospheric variability contributes to increasing wildfire weather but not as much as global warming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2117876118 (2021).

Jones, M. W. et al. Global and regional trends and drivers of fire under climate change. Rev. Geophys. 60, e2020RG000726 (2022).

Hsiang, S. et al. Estimating economic damage from climate change in the United States. Science 356, 1362–1369 (2017).

Technical Documentation on the Framework for Evaluating Damages and Impacts (FrEDI) (EPA, 2023).

Iglesias, V., Balch, J. K. & Travis, W. R. U. S. fires became larger, more frequent, and more widespread in the 2000s. Sci. Adv. 8, eabc0020 (2022).

McClure, C. D. & Jaffe, D. A. US particulate matter air quality improves except in wildfire-prone areas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 7901–7906 (2018).

O’Dell, K., Ford, B., Fischer, E. V. & Pierce, J. R. Contribution of wildland-fire smoke to US PM2.5 and its influence on recent trends. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1797–1804 (2019).

Childs, M. L. et al. Daily local-level estimates of ambient wildfire smoke PM2.5 for the contiguous US. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c02934 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. Wildland fires worsened population exposure to PM2.5 pollution in the contiguous United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 19990–19998 (2023).

Reid, C. E. et al. Critical review of health impacts of wildfire smoke exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 1334–1343 (2016).

Gould, C. F. et al. Health effects of wildfire smoke exposure. Annu. Rev. Med. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-052422-020909 (2023).

Chen, G. et al. Mortality risk attributable to wildfire-related PM2.5 pollution: a global time series study in 749 locations. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e579–e587 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Dominance of wildfires impact on air quality exceedances during the 2020 record‐breaking wildfire season in the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094908 (2021).

Burke, M. et al. The contribution of wildfire to PM2.5 trends in the USA. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06522-6 (2023).

Zhuang, Y., Fu, R., Santer, B. D., Dickinson, R. E. & Hall, A. Quantifying contributions of natural variability and anthropogenic forcings on increased fire weather risk over the western United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2111875118 (2021).

Zhong, Q., Shen, G., Wang, B., Ma, J. & Tao, S. Climate-driven escalation of global PM2.5 health burden from wildland fires. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 3131–3142 (2025).

Westerling, A. L. Increasing western US forest wildfire activity: sensitivity to changes in the timing of spring. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 371, 20150178 (2016).

Law, B. E. et al. Anthropogenic climate change contributes to wildfire particulate matter and related mortality in the United States. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 336 (2025).

Radeloff, V. C. et al. Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 3314–3319 (2018).

Balch, J. K. et al. Warming weakens the night-time barrier to global fire. Nature 602, 442–448 (2022).

Hessilt, T. D. et al. Future increases in lightning ignition efficiency and wildfire occurrence expected from drier fuels in boreal forest ecosystems of western North America. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 054008 (2022).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Juang, C. S., Williams, A. P., Kolden, C. A. & Westerling, A. L. Increasing synchronous fire danger in forests of the western United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091377 (2021).

Wang, S. S.-C., Leung, L. R. & Qian, Y. Projection of future fire emissions over the contiguous US using explainable artificial intelligence and CMIP6 models. J. Geophys. Res. 128, e2023JD039154 (2023).

Brown, P. T. et al. Climate warming increases extreme daily wildfire growth risk in California. Nature 621, 760–766 (2023).

Lam, Y. F., Fu, J. S., Wu, S. & Mickley, L. J. Impacts of future climate change and effects of biogenic emissions on surface ozone and particulate matter concentrations in the United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 4789–4806 (2011).

Yue, X., Mickley, L. J., Logan, J. A. & Kaplan, J. O. Ensemble projections of wildfire activity and carbonaceous aerosol concentrations over the western United States in the mid-21st century. Atmos. Environ. 77, 767–780 (2013).

Sarangi, C. et al. Projected increases in wildfires may challenge regulatory curtailment of PM2.5 over the eastern US by 2050. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 1769–1783 (2023).

Liu, J. C. et al. Future respiratory hospital admissions from wildfire smoke under climate change in the Western US. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 124018 (2016).

Ford, B. et al. Future fire impacts on smoke concentrations, visibility, and health in the contiguous United States. Geohealth 2, 229–247 (2018).

Neumann, J. E. et al. Estimating PM2.5-related premature mortality and morbidity associated with future wildfire emissions in the western US. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 035019 (2021).

Stowell, J. D. et al. Asthma exacerbation due to climate change-induced wildfire smoke in the Western US. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 014023 (2021).

Wang, S. S.-C., Qian, Y., Leung, L. R. & Zhang, Y. Interpreting machine learning prediction of fire emissions and comparison with FireMIP process-based models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 3445–3468 (2022).

Ye, X. et al. Evaluation and intercomparison of wildfire smoke forecasts from multiple modeling systems for the 2019 Williams Flats fire. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 14427–14469 (2021).

Carter, T. S. et al. How emissions uncertainty influences the distribution and radiative impacts of smoke from fires in North America. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 2073–2097 (2020).

Xie, Y., Lin, M. & Horowitz, L. W. Summer PM2.5 pollution extremes caused by wildfires over the western United States during 2017–2018. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089429 (2020).

Qiu, M. et al. Evaluating chemical transport and machine learning models for wildfire smoke PM2.5: implications for assessment of health impacts. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c05922 (2024).

Southworth, E. K. et al. The influence of wildfire smoke on ambient PM2.5 chemical species concentrations in the contiguous US. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c09011 (2025).

Heft-Neal, S. et al. Emergency department visits respond nonlinearly to wildfire smoke. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2302409120 (2023).

Xie, Y. et al. Tripling of western US particulate pollution from wildfires in a warming climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2111372119 (2022).

Rennert, K. et al. Comprehensive evidence implies a higher social cost of CO2. Nature 610, 687–692 (2022).

van der Werf, G. R. et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 697–720 (2017).

Ma, Y. et al. Long-term exposure to wildland fire smoke PM2.5 and mortality in the contiguous United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2403960121 (2024).

Zhang, D., Xi, Y., Boffa, D. J., Liu, Y. & Nogueira, L. M. Association of wildfire exposure while recovering from lung cancer surgery with overall survival. JAMA Oncol. 9, 1214–1220 (2023).

Elser, H. et al. Wildfire smoke exposure and incident dementia. JAMA Neurol. 82, 40–48 (2025).

Carleton, T. et al. Valuing the global mortality consequences of climate change accounting for adaptation costs and benefits. Q. J. Econ. 137, 2037–2105 (2022).

Grillakis, M. et al. Climate drivers of global wildfire burned area. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 045021 (2022).

Abatzoglou, J. T. et al. Projected increases in western US forest fire despite growing fuel constraints. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 227 (2021).

Connolly, R. et al. Mortality attributable to PM2.5 from wildland fires in California from 2008 to 2018. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl1252 (2024).

Park, C. Y. et al. Future fire-PM2.5 mortality varies depending on climate and socioeconomic changes. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 024003 (2024).

Deryugina, T., Heutel, G., Miller, N. H., Molitor, D. & Reif, J. The mortality and medical costs of air pollution: evidence from changes in wind direction. Am. Econ. Rev. 109, 4178–4219 (2019).

Weichenthal, S. et al. How low can you go? Air pollution affects mortality at very low levels. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo3381 (2022).

Rao, K., Williams, A. P., Diffenbaugh, N. S., Yebra, M. & Konings, A. G. Plant-water sensitivity regulates wildfire vulnerability. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 332–339 (2022).

Schollaert, C. L. et al. Quantifying the smoke-related public health trade-offs of forest management. Nat. Sustain. 7, 130–139 (2023).

Dickinson, G. N. et al. Health risk implications of volatile organic compounds in wildfire smoke during the 2019 FIREX‐AQ campaign and beyond. Geohealth 6, e2021GH000546 (2022).

Gao, Y. et al. Wildfire-related PM2.5 and cardiovascular mortality: a difference-in-differences analysis in Brazil. Environ. Pollut. 347, 123810 (2024).

Gao, Y. et al. Wildfire-related PM2.5 and cause-specific cancer mortality. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 285, 117023 (2024).

Kelp, M., Burke, M., Qiu, M., Liu, T. & Diffenbaugh, N. Effect of recent prescribed burning and land management on wildfire burn severity and smoke emissions in the western United States. AGU Adv. 6, e2025AV001682 (2025).

Burke, M. et al. Exposures and behavioural responses to wildfire smoke. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1351–1361 (2022).

van Donkelaar, A. et al. Monthly global estimates of fine particulate matter and their uncertainty. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 15287–15300 (2021).

Buch, J., Williams, A. P., Juang, C. S., Hansen, W. D. & Gentine, P. SMLFire1.0: a stochastic machine learning (SML) model for wildfire activity in the western United States. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 3407–3433 (2023).

Mesinger, F. et al. North American regional reanalysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 87, 343–360 (2006).

Xia, Y. et al. Continental-scale water and energy flux analysis and validation for North American Land Data Assimilation System project phase 2 (NLDAS-2): 2. Validation of model-simulated streamflow. J. Geophys. Res. 117, D03109 (2012).

Mitchell, K. E. et al. The multi‐institution North American Land Data Assimilation System (NLDAS): utilizing multiple GCIP products and partners in a continental distributed hydrological modeling system. J. Geophys. Res. 109, 2003JD003823 (2004).

Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC), North American Land Change Monitoring System, Canada Centre for Remote Sensing (CCRS), U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO), Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR), Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). North American Environmental Atlas – Land Cover 2015 30m, edn 4.0. https://www.cec.org/north-american-environmental-atlas/land-cover-30m-2015-landsat-and-rapideye/ (2024).

Pullabhotla, H. K., Zahid, M., Heft-Neal, S., Rathi, V. & Burke, M. Global biomass fires and infant mortality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218210120 (2023).

Qiu, M., Ratledge, N., Azevedo, I. M. L., Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Burke, M. Drought impacts on the electricity system, emissions, and air quality in the western United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2300395120 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Smoke-weather interaction affects extreme wildfires in diverse coastal regions. Science 379, 457–461 (2023).

Urbanski, S. Wildland fire emissions, carbon, and climate: emission factors. For. Ecol. Manage. 317, 51–60 (2014).

Jen, C. N. et al. Speciated and total emission factors of particulate organics from burning western US wildland fuels and their dependence on combustion efficiency. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 1013–1026 (2019).

Liang, Y. et al. Emissions of organic compounds from western US wildfires and their near-fire transformations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 9877–9893 (2022).

Jaffe, D. A. et al. Wildfire and prescribed burning impacts on air quality in the United States. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 70, 583–615 (2020).

Achtemeier, G. L. Measurements of moisture in smoldering smoke and implications for fog. Int. J. Wildland Fire 15, 517 (2006).

Shen, L., Mickley, L. J. & Murray, L. T. Influence of 2000–2050 climate change on particulate matter in the United States: results from a new statistical model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 4355–4367 (2017).

Westervelt, D. M. et al. Quantifying PM2.5-meteorology sensitivities in a global climate model. Atmos. Environ. 142, 43–56 (2016).

Mickley, L. J., Jacob, D. J., Field, B. D. & Rind, D. Effects of future climate change on regional air pollution episodes in the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L24103 (2004).

Barnes, E. A. & Fiore, A. M. Surface ozone variability and the jet position: Implications for projecting future air quality. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 2839–2844 (2013).

Turner, A. J., Fiore, A. M., Horowitz, L. W. & Bauer, M. Summertime cyclones over the Great Lakes Storm Track from 1860–2100: variability, trends, and association with ozone pollution. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 565–578 (2013).

NCHS. Multiple Cause of Death 1999–2020. National Vital Statistics System (CDC, 2023).

Wei, Y. et al. Exposure-response associations between chronic exposure to fine particulate matter and risks of hospital admission for major cardiovascular diseases: population based cohort study. Brit. Med. J. 384, e076939 (2024).

Hsiang, S. Climate econometrics. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 8, 43–75 (2016).

Di, Q. et al. Air pollution and mortality in the Medicare population. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 2513–2522 (2017).

Pope, C. A., Coleman, N., Pond, Z. A. & Burnett, R. T. Fine particulate air pollution and human mortality: 25+ years of cohort studies. Environ. Res. 183, 108924 (2020).

Krewski, D. et al. Extended follow-up and spatial analysis of the American Cancer Society study linking particulate air pollution and mortality. Res. Rep. Health Eff. Inst. 140, 5–114 (2009).

Hoek, G. et al. Long-term air pollution exposure and cardio- respiratory mortality: a review. Environ. Health 12, 43 (2013).

NCHS. Multiple Cause of Death 1999–2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, Released 2021: Data Compiled from Data Provided by the 57 Vital Statistics Jurisdictions Through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program (CDC, 2021); https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html.

O’Dell, K. et al. Estimated mortality and morbidity attributable to smoke plumes in the United States: not just a western US problem. Geohealth 5, e2021GH000457 (2021).

US Census Bureau. National Population Projections Tables: Main Series (2023).

Berlin Rubin, N. & Wong-Parodi, G. As California burns: the psychology of wildfire- and wildfire smoke-related migration intentions. Popul. Environ. 44, 15–45 (2022).

McConnell, K. et al. Rare and highly destructive wildfires drive human migration in the U.S. Nat. Commun. 15, 6631 (2024).

EPA Report on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases: Estimates Incorporating Recent Scientific Advances (EPA, 2023).

Qiu, M. et al. Data and code for ‘Wildfire smoke exposure and mortality burden in the USA under climate change’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16855665 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Wilson for helping process mortality data; Y. Ma and K. Chen for sharing their smoke mortality estimates for comparison; A. van Donkelaar for helping with dataset of total PM2.5 concentrations; seminar participants at Stanford University, Harvard University and the Brookhaven National Laboratory for comments; and the Keck Foundation for funding. M.Q. acknowledges the support from the planetary health fellowship at Stanford’s Center for Innovation in Global Health, and Minghua Zhang faculty career catalyst award from Stony Brook University. M.L.C. was supported by an Environmental Fellowship at the Harvard University Center for the Environment. R.J. acknowledges support for this work from NIH grant R01HD104835 and the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award grant 5T32HS026128-07. N.S.D. acknowledges support from Stanford University. Some of the computing for this project was performed on the Stanford Sherlock cluster, and we thank Stanford University and the Stanford Research Computing Center for providing computational resources and support that contributed to these research results. NCEP North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR) data were provided by the NOAA PSL from their website (https://psl.noaa.gov).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Q. and M.B. designed the study. M.Q. led the smoke projection modelling with inputs from all of the authors. M.Q., J.L. and R.J. led the statistical and machine learning modelling of fire emissions. M.Q., S.H.-N., C.F.G. and M.L.C. led the health impacts analysis. M.Q. and M.B. led the writing of the manuscript. M.Q., J.L., C.F.G., R.J., M.K., M.L.C., J.W., Y.X., M.L., M.V.K., S.H.-N., N.S.D. and M.B contributed to interpretation of results and reviewed the manuscripts.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Joan Casey, Lulu Chen, Gaige Kerr, Scott Weichenthal, Xiao Wu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Future smoke contribution from different fire regions.

Source-receptor matrix of the contributions from fire emissions from the five source regions (x-axis) to population-weighted smoke PM2.5 concentrations in nine receptor regions across the contiguous US (y-axis). The plot shows the contributions in 2046–2055 averaged over all GCMS under the SSP3-7.0 scenario.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Historical and projected dry matter (DM) emissions.

Historical annual average emissions in 2001–2021 and projected annual emissions (2046–2055) under the SSP3-7.0 scenario in the eastern US (top), Canada and Alaska (middle), and Mexico (bottom). Projected emissions are first stochastically downscaled from regional emissions predictions and then averaged over 40 simulated downscaling estimates.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Illustration of the stochastic downscaling approach using the western US as an example.

Historical annual average emissions in 2001–2021 from GFED4s, and projected annual emissions averaged between 2046–2055 under the SSP3-7.0 scenario at the grid level. The “static” panel shows the results derived from the static downscaling method, which applies a common ratio to the historical emission pattern to match the future projected emissions. The “stochastic” panel shows our main stochastic downscaling method, which generates the same total emissions as the static method regionally but allows for the possibility that grids that have never burned could burn. Projected emissions are first stochastically downscaled from regional emissions predictions and then averaged over 40 simulated downscaling estimates (six are shown here for the illustration purpose).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Estimated annual excess deaths due to smoke PM2.5 using alternative exposure-response functions.

Panel A: results estimated using alternative smoke-mortality models (averaged over 2011–2020). In addition to our main model (grey bar), we estimate a model that uses the public mortality data from CDC WONDER, a model that additionally includes year 2020 in the regressions, a model that follows similar specification from Ma et al., 2024 (i.e. a monthly model with alternative bin specifications and 12-month moving average of smoke PM2.5 concentration), and models which calculates the number of months or the number of days in a year that fall in different smoke bins to represent different temporal aggregations. The bars show mean values of bootstrapped estimates, and the whiskers show bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (500 bootstraps). Panel B: results estimated using published exposure-response functions that link total PM2.5 to mortality. Note the results here are estimated using lag 0 model and all-ages group, to match earlier work.

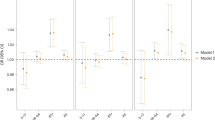

Extended Data Fig. 5 Cumulative effects of smoke on mortality across different lag years.

Panel A: aggregated coefficients for each smoke bin across different lag years, representing the cumulative effects of smoke exposure on mortality in the same year and subsequent years. Panel B: estimated mortality due to annual smoke PM2.5 under historical (2011–2020) and future scenarios (2046–2055). The plot shows the same-year mortality due to smoke (in the case of lag 0), and cumulative mortality (lag 0-1,…,lag 0-4). The bars show mean values of bootstrapped estimates, and the whiskers show bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (500 bootstraps). We report results from “lag 0-1” model as our main estimates.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Estimated excess deaths due to smoke PM2.5 under the historical, SSP1-2.6, and SSP3-7.0 scenarios due to annual smoke exposure (lag 0-1).

The top panels show estimates at the county level. The bottom panels show estimates at the state level.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Uncertainty in projected annual smoke PM2.5 concentration (Panel A) and mortality (Panel B).

The red dashed line shows the main estimate. The solid bar shows the 10th and 90th percentile, and the black line shows the 2.5th and 97.5th percentile. Uncertainty from “climate projection” is calculated using the percentiles of 28 GCMs. Uncertainty from “climate-fire model” and “fire-smoke model” is calculated using bootstrap procedures performed on the climate-fire and fire-smoke models. Uncertainty from “emission downscaling” shows the range of smoke and mortality estimated across 40 different downscaling estimates. Uncertainty from “smoke-mortality function” is calculated using bootstrap procedures performed on the smoke-mortality response functions. The combined uncertainty is quantified using a Monte-Carlo simulation approach, where we randomly sample 500 combinations of GCMs, climate-fire models, downscaling estimates, and fire-smoke models, and smoke-mortality functions.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–11, Supplementary Figs. 1–12 and Supplementary References.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, M., Li, J., Gould, C.F. et al. Wildfire smoke exposure and mortality burden in the USA under climate change. Nature 647, 935–943 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09611-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09611-w