Abstract

The interleukin-4 (IL-4) cytokine plays a critical role in modulating immune homeostasis. Although there is great interest in harnessing this cytokine as a therapeutic in natural or engineered formats, the clinical potential of native IL-4 is limited by its instability and pleiotropic actions. Here, we design IL-4 cytokine mimetics (denoted Neo-4) based on a de novo engineered IL-2 mimetic scaffold and demonstrate that these cytokines can recapitulate physiological functions of IL-4 in cellular and animal models. In contrast with natural IL-4, Neo-4 is hyperstable and signals exclusively through the type I IL-4 receptor complex, providing previously inaccessible insights into differential IL-4 signaling through type I versus type II receptors. Because of their hyperstability, our computationally designed mimetics can directly incorporate into sophisticated biomaterials that require heat processing, such as three-dimensional-printed scaffolds. Neo-4 should be broadly useful for interrogating IL-4 biology, and the design workflow will inform targeted cytokine therapeutic development.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The original experimental data that support the findings of this work are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported hNeo-4 crystal structure have been deposited with the PDB under accession code 8DZB. Diffraction images of hNeo-4 have been deposited in the SBGrid Data Bank with digital object identifier 959. The Neo-2 crystallographic structure used in this study can be accessed at the PDB database under accession code 6DG5. Plasmids encoding the proteins described in this article are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code for developing mechanistic computational models of IL-4 signaling can be accessed in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/meyer-lab/IL4-model.

References

Wang, X., Lupardus, P., LaPorte, S. L. & Garcia, K. C. Structural biology of shared cytokine receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 29–60 (2009).

Wynn, T. A. Type 2 cytokines: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 271–282 (2015).

Junttila, I. S. Tuning the cytokine responses: an update on interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 receptor complexes. Front. Immunol. 9, 888 (2018).

LaPorte, S. L. et al. Molecular and structural basis of cytokine receptor pleiotropy in the interleukin-4/13 system. Cell 132, 259–272 (2008).

Junttila, I. S. et al. Redirecting cell-type specific cytokine responses with engineered interleukin-4 superkines. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 990–998 (2012).

Nelms, K., Keegan, A. D., Zamorano, J., Ryan, J. J. & Paul, W. E. The IL-4 receptor: signaling mechanisms and biologic functions. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 701–738 (1999).

Luzina, I. G. et al. Regulation of inflammation by interleukin-4: a review of ‘alternatives’. J. Leukoc. Biol. 92, 753–764 (2012).

Hou, J. et al. An interleukin-4-induced transcription factor: IL-4 Stat. Science 265, 1701–1706 (1994).

Heller, N. M. et al. Type I IL-4Rs selectively activate IRS-2 to induce target gene expression in macrophages. Sci. Signal. 1, ra17 (2008).

Sosman, J. A., Kefer, C., Fisher, R. I., Ellis, T. M. & Fisher, S. G. A phase I trial of continuous infusion interleukin-4 (IL-4) alone and following interleukin-2 (IL-2) in cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 5, 447–452 (1994).

Hemmerle, T. & Neri, D. The antibody-based targeted delivery of interleukin-4 and 12 to the tumor neovasculature eradicates tumors in three mouse models of cancer: IL4- and IL12-based immunocytokines. Int. J. Cancer 134, 467–477 (2014).

Karo-Atar, D., Bitton, A., Benhar, I. & Munitz, A. Therapeutic targeting of the interleukin-4/interleukin-13 signaling pathway: in allergy and beyond. BioDrugs 32, 201–220 (2018).

Shimamura, T., Husain, S. R. & Puri, R. K. The IL-4 and IL-13 Pseudomonas exotoxins: new hope for brain tumor therapy. Neurosurg. Focus 20, E11 (2006).

Antoniu, S. A. Pitrakinra, a dual IL-4/IL-13 antagonist for the potential treatment of asthma and eczema. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 11, 1286–1294 (2010).

Taverna, D. M. & Goldstein, R. A. Why are proteins marginally stable? Proteins 46, 105–109 (2002).

De Groot, A. S. & Scott, D. W. Immunogenicity of protein therapeutics. Trends Immunol. 28, 482–490 (2007).

Silva, D.-A. et al. De novo design of potent and selective mimics of IL-2 and IL-15. Nature 565, 186–191 (2019).

Quijano-Rubio, A., Ulge, U. Y., Walkey, C. D. & Silva, D.-A. The advent of de novo proteins for cancer immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 56, 119–128 (2020).

Huang, P.-S., Boyken, S. E. & Baker, D. The coming of age of de novo protein design. Nature 537, 320–327 (2016).

Mohan, K. et al. Topological control of cytokine receptor signaling induces differential effects in hematopoiesis. Science 364, eaav7532 (2019).

Glasgow, A. A. et al. Computational design of a modular protein sense–response system. Science 366, 1024–1028 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. De novo design of protein logic gates. Science 368, 78–84 (2020).

Spangler, J. B. et al. Antibodies to interleukin-2 elicit selective T cell subset potentiation through distinct conformational mechanisms. Immunity 42, 815–825 (2015).

Andrews, R. P., Rosa, L. R., Daines, M. O. & Hershey, G. K. K. Reconstitution of a functional human type II IL-4/IL-13 receptor in mouse B cells: demonstration of species specificity. J. Immunol. 166, 1716–1722 (2001).

Salavessa, L. et al. Cytokine receptor cluster size impacts its endocytosis and signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2024893118 (2021).

Rolling, C., Treton, D., Pellegrini, S., Galanaud, P. & Richard, Y. IL4 and IL13 receptors share the γc chain and activate STAT6, STAT3 and STAT5 proteins in normal human B cells. FEBS Lett. 393, 53–56 (1996).

Wang, I.-M., Lin, H., Goldman, S. J. & Kobayashi, M. STAT-1 is activated by IL-4 and IL-13 in multiple cell types. Mol. Immunol. 41, 873–884 (2004).

Mohrs, M., Shinkai, K., Mohrs, K. & Locksley, R. M. Analysis of type 2 immunity in vivo with a bicistronic IL-4 reporter. Immunity 15, 303–311 (2001).

Deavall, D. G., Martin, E. A., Horner, J. M. & Roberts, R. Drug-induced oxidative stress and toxicity. J. Toxicol. 2012, 645460 (2012).

Chan, F. K. -M., Moriwaki, K. & De Rosa, M. J. in Immune Homeostasis (eds Snow, A. L. & Lenardo, M. J.) 65–70 (Humana Press, 2013).

Sadtler, K. et al. Developing a pro-regenerative biomaterial scaffold microenvironment requires T helper 2 cells. Science 352, 366–370 (2016).

Hamidzadeh, K., Christensen, S. M., Dalby, E., Chandrasekaran, P. & Mosser, D. M. Macrophages and the recovery from acute and chronic inflammation. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 79, 567–592 (2017).

Chung, L. et al. Interleukin 17 and senescent cells regulate the foreign body response to synthetic material implants in mice and humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eaax3799 (2020).

Junttila, I. S. et al. Tuning sensitivity to IL-4 and IL-13: differential expression of IL-4Rα, IL-13Rα1, and γc regulates relative cytokine sensitivity. J. Exp. Med. 205, 2595–2608 (2008).

Tan, Z. C. & Meyer, A. S. A general model of multivalent binding with ligands of heterotypic subunits and multiple surface receptors. Math. Biosci. 342, 108714 (2021).

Jammalamadaka, U. & Tappa, K. Recent advances in biomaterials for 3D printing and tissue engineering. J. Funct. Biomater. 9, 22 (2018).

Kushwaha, S. Application of hot melt extrusion in pharmaceutical 3D printing. J. Bioequivalence Bioavail. 10, 3 (2018).

Stanković, M., Frijlink, H. W. & Hinrichs, W. L. J. Polymeric formulations for drug release prepared by hot melt extrusion: application and characterization. Drug Discov. Today 20, 812–823 (2015).

Pugliese, R., Beltrami, B., Regondi, S. & Lunetta, C. Polymeric biomaterials for 3D printing in medicine: an overview. Ann. 3D Print. Med. 2, 100011 (2021).

Abdelfatah, J. et al. Experimental analysis of the enzymatic degradation of polycaprolactone: microcrystalline cellulose composites and numerical method for the prediction of the degraded geometry. Materials 14, 2460 (2021).

Shim, J.-H. et al. Comparative efficacies of a 3D-printed PCL/PLGA/β-TCP membrane and a titanium membrane for guided bone regeneration in beagle dogs. Polymers 7, 2061–2077 (2015).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Cell adhesion and proliferation evaluation of SFF-based biodegradable scaffolds fabricated using a multi-head deposition system. Biofabrication 1, 015002 (2009).

Levin, A. M. et al. Exploiting a natural conformational switch to engineer an interleukin-2 superkine. Nature 484, 529–533 (2012).

Charych, D. H. et al. NKTR-214, an engineered cytokine with biased IL2 receptor binding, increased tumor exposure, and marked efficacy in mouse tumor models. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 680–690 (2016).

Moraga, I. et al. Instructive roles for cytokine–receptor binding parameters in determining signaling and functional potency. Sci. Signal. 8, ra114 (2015).

Richter, D. et al. Ligand-induced type II interleukin-4 receptor dimers are sustained by rapid re-association within plasma membrane microcompartments. Nat. Commun. 8, 15976 (2017).

Vaishya, R. & Mitra, A. K. Future of sustained protein delivery. Ther. Deliv. 5, 1171–1174 (2014).

Song, Y. et al. High-resolution comparative modeling with RosettaCM. Structure 21, 1735–1742 (2013).

Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 (2010).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Bricogne, G. et al. BUSTER Version 2.10.3 (Global Phasing, Ltd., 2017).

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022).

Eastman, P. et al. OpenMM 7: rapid development of high performance algorithms for molecular dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005659 (2017).

Wang, X., Rickert, M. & Garcia, K. C. Structure of the quaternary complex of interleukin-2 with its α, ß, and γc receptors. Science 310, 1159–1163 (2005).

LaPorte, S. L. et al. Molecular and structural basis of cytokine receptor pleiotropy in the interleukin-4/13 system. Cell 132, 259–272 (2008).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D.Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the \({2{^{-\Delta\Delta{C}_{t}}}}\) method.Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Hulsen, T., de Vlieg, J. & Alkema, W. BioVenn—a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics 9, 488 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Peña, E. Mihealsick and G. Russo for advice on conducting mRNA isolation and RT–qPCR. The graphical abstract and Figs. 5b and 6c were created with BioRender.com. The package venndiagram.tk was used to generate Fig. 3b. We acknowledge funding from NIH (U01AI148119 to A.S.M., R01AI5321 to K.C.G., Director’s Pioneer Award to J.H.E., R01CA240339 to D.B. and R01EB029455 to J.B.S.) and the Emerson Collective Cancer Research Fund to J.B.S. We thank Bruce and Jeannie Nordstrom and Patty and Jimmy Barrier Gift for the Institute for Protein Design (IPD) Fund (budget number 68–0341), CONACyT SNI (Mexico), CONACyT postdoctoral fellowship (Mexico) and IPD translational research program to D.-A.S.; ‘la Caixa’ Fellowship (‘la Caixa’ Banking Foundation, Barcelona, Spain) to A.Q.-R. and JDRF (2-SRA-2016–236-Q-R) to U.Y.U. K.C.G. is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. W.J.L. is supported by the Division of Intramural Research, NHLBI, NIH. H.Y., Z.J.B. and D.R.M. are recipients of National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program awards.

GM/CA@APS has been funded by the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006, P30GM138396). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract number DE-AC02-06CH11357. The Eiger 16M detector at GM/CA-XSD was funded by NIH grant S10 OD012289. For RNA-seq data, next-generation sequencing was performed at the NHLBI DNA Sequencing Core.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

U.Y.U., A.Q.-R., J.-H.C., D.-A. S. and D.B. designed, produced and characterized the binding kinetics of Neo-4 mimetics. H.Y., Z.J.B., W.W., D.R.M., Y.-H.K., N.M.H. and J.B.S. designed and conducted in vitro cellular signaling assays and gene expression evaluations. H.Y., W.W., D.R.M., L.C., J.H.E. and J.B.S. designed and performed in vivo studies of mNeo-4. J.-X.L., P.L. and W.J.L. designed and conducted RNA-seq analyses. K.M.J. and K.C.G. designed and performed crystallography studies. K.M.J. performed protein structure modeling using AlphaFold2. B.T.O.-J. and A.S.M. developed and analyzed computational models of IL-4 binding and signaling dynamics. H.Y., Z.J.B, L.C., S.S., J.M. and W.L.G. designed, produced and characterized 3D-printed scaffolds containing IL-4 and Neo-4. H.Y., U.Y.U., Z.J.B., Y.H.A. and J.B.S. wrote the draft of the manuscript, and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. D.B. and J.B.S. supervised all research for this study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

U.Y.U., A.Q.-R., D.-A.S. and D.B. are cofounders and stockholders of Neoleukin Therapeutics, a company that aims to develop the inventions described in this manuscript. U.Y.U., A.Q.-R., D.-A.S., D.B. and J.B.S. are co-inventors on a US provisional patent application (number 62/689769), which incorporates discoveries described in this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Jun Ishihara and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

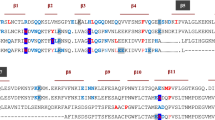

Extended Data Fig. 1 De novo design and production of Neo-4 molecules.

a, Structural alignment of Neo-2 and hIL-4. Residues in hIL-4 at the hIL-4/hIL-4Rα interface that were grafted onto Neo-2 are depicted with sticks, and the corresponding residues on Neo-2 are depicted with lines. b, structural alignment of hNeo-4 and mIL-4. Residues in mIL-4 at the mIL-4/mIL-4Rα interface that were grafted onto hNeo-4 are depicted with sticks, and the corresponding residues on hNeo-4 are depicted with lines. c, Amino acid sequence alignment of Neo-2, designed hNeo-4, and the final evolved hNeo-4 (henceforth denoted hNeo-4), demonstrating the evolution of the hNeo-4 sequence during the development process. Mutations introduced at each round of evolution are marked in red. d, Amino acid sequence alignment of designed hNeo-4, designed mNeo-4 and the final evolved mNeo-4 (henceforth denoted mNeo-4), demonstrating the evolution of the mNeo-4 sequence during the development process. Mutations introduced at each round of evolution are marked in red. mIL-4 cysteine at position 87, depicted in yellow, was not grafted to the hNeo-4 structure. e. SDS-PAGE analysis of purified hNeo-4 and mNeo-4. Experiment was repeated once independently with similar results. f, AlphaFold2 predictions of the structure of hNeo-4 bound to the human type I IL-4 receptor complex (peach) aligned to the IL-4Rα subunit in the experimentally determined crystal structure of the type I hIL-4 complex (gray; PDB ID 3BPL). hNeo-4 is predicted to preserve all three binding interfaces present in the hIL-4 signaling complex.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Flow cytometry plots depicting the selection process for evolution of IL-4 mimetics.

Yeast libraries were incubated with fluorescent streptavidin only (Negative Control, left column) or with the indicated biotinylated receptor subunits followed by fluorescent streptavidin (Sorted Population, center column), with difference histogram shown on the right (blue represents Negative Control and line represents Sorted Population). Concentrations of soluble receptor chain(s) used in each round of selection are indicated next to the histograms. Expression of IL-4 mimetics on the yeast surface is tracked by Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-cmyc tag antibody and binding is quantified by phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled streptavidin. a-c, Rounds 2, 3, and 4 of human IL-4 mimetic evolution. d-e, Rounds 2 and 3 of mouse IL-4 mimetic evolution.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Characterization of Neo-4 binding properties.

a, Equilibrium bio-layer interferometry (BLI) titrations of hIL-4 or hNeo-4 against immobilized hIL-4Rα. b, BLI sensograms depicting interactions between hIL-4 or hNeo-4 and the hIL-4Rα/hγc complex. Equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) derived from the kinetic parameters are indicated. Equilibrium BLI titrations of hIL-4 or hNeo-4 (3-fold serial dilutions starting at 333 nM for both) against the hIL-4Rα/hγc complex are shown at right. c-d, BLI sensograms depicting the interaction between hNeo-4 or Neo-2 and immobilized (c) IL-2Rβ and (d) hIL-2Rβ/hγc complex. In (c) biosensors were exposed to 3-fold serial dilutions of Neo-2 starting at 60 nM or hNeo-4 starting at 100 nM, respectively; and in (d) biosensors were exposed to 3-fold serial dilutions of Neo-2 starting at 33 nM or hNeo-4 starting at 300 nM, respectively. KD values derived from the kinetic parameters are indicated. Equilibrium BLI titrations of hNeo-4 or Neo-2 against immobilized (c) hIL-2Rβ and (d) hIL-2Rβ/hγc are shown at right. e, Equilibrium BLI titrations of mIL-4 or mNeo-4 against immobilized mIL-4Rα extracellular domain. f, BLI sensograms depicting interactions between mIL-4 or mNeo-4 (3-fold serial dilutions starting at 650 nM for mIL-4 and 750 nM for mNeo-4) and mIL-4Rα/mγc complexes. KD values derived from the kinetic parameters are indicated. Equilibrium BLI titrations of mIL-4 or mNeo-4 against the mIL-4Rα/mγc complex are shown at right. All raw data were fitted using a 1:1 Langmuir binding model. Fitted curves are shown in gray.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Characterization of Neo-4 bioactivity in vitro.

a, STAT6 phosphorylation induced by hIL-4, hNeo-4, or Neo-2 in human Ramos B cells (n = 3) and primary monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) (n = 3). b, STAT6 phosphorylation induced by mIL-4, mNeo-4, or Neo-2 in mouse A20 B cells (n = 3) and primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (n = 4) c, STAT5 phosphorylation induced by hIL-4, hNeo-4, or Neo-2 in human YT-1 natural killer cells (n = 3). Data represent mean ± SD. d, qRT-PCR analysis of CD200r1 expression in primary human monocytes treated with hIL-4 or hNeo-4 (n = 4). Data represent mean ± SD (n = 4). ****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA. e, Chil3, Il1b expression in primary mouse BMDMs treated with mIL-4 and mNeo-4. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 4 biologically independent samples). ****p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA. f, STAT6 phosphorylation induced by hIL-4, hIL-13, or hNeo-4. in human primary monocytes. Saturating concentrations of all 3 protein treatments were determined to be 100 nM, as indicated by the red line, guiding dosing for RNA-seq studies. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 2). g, Flow cytometry histograms showing CD14 expression levels on PBMCs before (gray) and after (red) CD14+ cell sorting. The sorted cells were considered monocytes. For ease of visualization, only significance compared to the control cohort is shown in panels d-e. All p-values are recorded in Supplementary Table 7. h, STAT6 phosphorylation induced by hIL-4, hIL-13, or hNeo-4 in human CD4+ T cells. i, Phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 induced by hIL-4, hIL-13, or hNeo-4 in human primary monocytes. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 2). j, Phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 induced by mIL-4 or mNeo-4 in mouse BMDMs. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 2).

Extended Data Fig. 5 In vitro toxicity assessment of Neo-4 compared to IL-4.

a-b, Human (a) or mouse (b) CD4+ T cells were subjected to Th2 polarization conditions through treatment with titrated amounts of IL-4 or Neo-4 for 1, 3, and 5 days. Live cell count, viability, and normalized reactive oxygen species staining are shown. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 2). c-d, LDH activity from supernatants of human CD4+ T cells (c) and human monocytes (d) polarized with titrated amounts of IL-4 or Neo-4 for 1, 3, and 5 days, as quantified by colorimetric assay. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 2).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Functional characterization of mIL-4 and mNeo-4 in mouse volumetric muscle loss model.

a, Illustration of experimental design and dosing regimen. Mice were treated with proteins or PBS for 4 consecutive days. Treatments were injected directly at the injury site on day 0, and the subsequent 3 treatments were injected subcutaneously. b, qRT-PCR analysis of genes related to tissue regeneration in isolated muscle samples (n = 1) from Pilot Study 1 (1.5 μg of mIL-4 or PBS treatments). Effects of mIL-4 were normalized to the PBS control. Fold change (FC) represents 2-ΔΔCT. c, Repeated qRT-PCR analysis of M2-like macrophage-related genes in isolated muscle samples (n = 4) from Pilot study 1. d, qRT-PCR analysis of M2-like macrophage-related genes from the isolated muscle samples (n = 5) in Pilot Study 2 (1.5 μg of mIL-4, 1.5 μg mNeo-4, or PBS treatments). Effects of mIL-4 or mNeo-4 were normalized to the PBS control. e-f, Mice were treated with either mNeo-4 (at low [0.03 µg, n = 5], medium [1.6 µg, n = 5], or high [71 µg, n = 4] dose), 1.5 µg mIL-4 (n = 5), or PBS (n = 5) in the model shown in a. qRT-PCR analysis of M2-like macrophage-related genes in isolated (e) muscle and (f) spleen samples are shown. Effects of each treatment were normalized to the PBS control. Data represent mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA. For ease of visualization, only significance compared to the control cohort is shown in panels c-f. All p-values are recorded in Supplementary Table 7. g, NanoString analysis (myeloid panel) on the muscle samples from mice treated as described in e-f. Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes are shown for the mNeo-4 versus the mIL-4 cohort. The significance of differential gene regulation was determined by calculating adjusted p values using the Benjamini-Yekutieli method of estimating false discovery rates (FDR) in the nCounter software (thresholds of adjusted P < 0.05, and 0.01 are shown).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Evaluation of biased signaling activation induced by IL-4 mimetics.

a, BLI sensograms depicting interactions between hIL-4 or hNeo-4 (3-fold serial dilutions starting at 1 μM) and the hIL-4Rα/hIL-13Rα1 complex. Equilibrium BLI titrations of hIL-4 or hNeo-4 against the hIL-4Rα/hIL-13Rα1 complex are shown at right. Raw data were fitted using a 1:1 Langmuir binding model. Fitted curves are shown in gray. b, STAT6 activation elicited by mIL-4 or mNeo-4 in mouse A20 cells (n = 3), BMDMs Mouse 1 (n = 3), BMDMs Mouse 2 (n = 2), and 3T3 fibroblast cells (n = 3). Type I or Type II receptor biases were defined by the ratio of mγc to mIL-13Rα1 expression on each cell line (shown below each plot), with higher ratios indicating type I receptor bias. Data represent mean ± SD. c-d, STAT6 activation induced by (c) hIL-4 and (d) hNeo-4 in human Ramos B cells (n = 3) in the presence (dotted lines) or absence (solid lines) of anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody. e-g, STAT6 activation induced by (e) hIL-4, (f) hIL-13, or (g) hNeo-4 in primary human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) (n = 2) in the presence (dotted lines) or absence (solid lines) of anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody. h-j, STAT6 activation induced by (h) hIL-4, (i) hIL-13, or (j) hNeo-4 in primary human monocytes (n = 3) in the presence (dotted lines) or absence (solid lines) of anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody. k-l, STAT6 activation induced by (k) hIL-4 or (l) hIL-13 in A549 lung epithelial cells (n = 3) in the presence (dotted lines) or absence (solid lines) of anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody. Data represent mean ± SD. m, Principal component analysis (PCA) of STAT6 activation induced by hIL-4, hIL-13, and hNeo-4 on 5 human cell lines (Ramos B cells, primary monocytes, MDMs, primary fibroblasts, and A549 cells). Half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50) that were used to compare the signaling activities of the 3 cytokines are tabulated in Supplementary Table 6.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Characterization and modeling of biased type I IL-4 receptor signaling elicited by hNeo-4.

a-b, STAT6 phosphorylation induced by hIL-4, hNeo-4, and super-4 in (a) Ramos B cells and (b) A549 lung epithelial cells. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples). c, Heat map showing the induction levels of the top 30 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in IL-4-treated fibroblasts. d-e, Prediction accuracies for STAT6 activation induced by mNeo-4 or mIL-4 in A20 B cells, primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), and 3T3 fibroblast cells, using either the (d) sequential or (e) multivalent IL-4 signaling model. f, Cross-validation of the accuracies of the multivalent model STAT6 activation predictions in human Ramos B cells, primary monocytes, primary monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs), primary fibroblasts, and A549 lung epithelial cells. g, Fitted equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) of hIL-4, hIL-13, or hNeo-4 binding to IL-4 receptor chains obtained from the multivalent model. N.B. indicates no binding. h, Fitted KD values of mIL-4 or mNeo-4 binding to IL-4 receptor chains obtained from the multivalent model. i, Experimental STAT6 activation by hIL-4, hIL-13, or hNeo4 compared to multivalent model predictions in MDMs, primary fibroblasts, and A549 cells.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Thermal stability characterization of IL-4 mimetics.

a, Thermal denaturation curves for hNeo-4 and Neo-2. b, Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of hNeo-4 at pre-heating (25 °C), melting (95 °C), and post-heating (25 °C) stages. c, Thermal denaturation curve for mNeo-4. d, CD spectra of mNeo-4 pre-heating (25 °C), melting (95 °C), and post-heating (25 °C) stages. e, Schematic of the manufacturing and characterization of a PCL-based 3D-printed scaffold incorporating hNeo-4. f, STAT6 phosphorylation induced by hIL-4, hNeo-4, and lyophilized hNeo-4 in Ramos B cells. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 2) g, Release profile of hNeo-4 (percentage mass) from 3D-printed scaffolds, as measured by fluorescent protein quantification assay. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples). h, Release profile of hNeo-4 (mass) from 3D-printed scaffolds, as measured by fluorescent protein quantification assay. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples). i, Quantification of hNeo-4 mass released from 3D-printed scaffold over 16 h incubation at 4 °C, as measured by fluorescent protein quantification assay. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 9 biologically independent samples). j, Percentage mass of hNeo-4 released from 3D-printed scaffold over 16 h incubation at 4 °C, as calculated based on the measurements from fluorescent protein quantification assay shown in i. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 9). k, STAT6 signaling activation induced by hNeo-4 from 3D-printed scaffolds on Ramos B cells. Signaling stimulated by either hNeo-4 released from 3D-printed scaffolds (M) or hNeo-4 on the surface of 3D-printed scaffolds (S) is shown. Signaling of unmodified PCL scaffolds is shown for reference. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent samples).

Extended Data Fig. 10 Characterization of IL-4 and Neo-4 protease and serum stability.

a-f, Human or mouse IL-4 and Neo-4 were incubated with trypsin (a,b), chymotrypsin (c,d), or pepsin (e,f) for various time periods and subsequently subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis to detect protein degradation. Protease stability tests of each protein were performed once for each time point. g, 1 mg/ml (final concentration) of 6XHis-tagged hIL-4 or hNeo-4 was incubated in human serum for the indicated time periods up to 4 h. h, 1 mg/ml (final concentration) of 6XHis-tagged mIL-4 or mNeo-4 was incubated in mouse serum for the indicated time periods up to 4 h. Cytokines were detected with an anti-6XHis tag antibody via immunoblotting. hIL-4 and mIL-4 migrate as 22-24 kDa and 19-23 kDa, respectively, on the gel due to glycosylation. Serum stability test of each protein was performed once independently with similar results.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1 and Tables 1–12.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data for Fig. 2c,d.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data for Fig. 4b,c.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed gel image for Extended Data Fig. 1e.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 4d,e.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 6c–e.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Unprocessed western blots and gels for Extended Data Fig. 10.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, H., Ulge, U.Y., Quijano-Rubio, A. et al. Design of cell-type-specific hyperstable IL-4 mimetics via modular de novo scaffolds. Nat Chem Biol 19, 1127–1137 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-023-01313-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-023-01313-6

This article is cited by

-

The JAK-STAT pathway: from structural biology to cytokine engineering

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2024)