Abstract

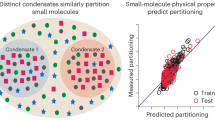

Many pharmaceutical targets partition into biomolecular condensates, whose microenvironments can significantly influence drug distribution. Nevertheless, it is unclear how drug design principles should adjust for these targets to optimize target engagement. To address this question, we systematically investigated how condensate microenvironments influence drug-targeting efficiency. We found that condensates highlight a notable heterogeneity, with nonpolar-residue-enriched condensates being more hydrophobic and housing more hydrophobic drugs. Furthermore, L1000 dataset analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between inhibitor hydrophobicity and targeting efficiency for phase-separated proteins, represented by estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) enriched with nonpolar residues. We developed random forest models to predict inhibitor targeting efficiency from molecular properties, with hydrophobicity identified as a key determinant. In cellulo experiments with ESR1 condensates confirmed that both binding affinity and hydrophobicity of inhibitors contribute significantly to potency. These results suggest a new drug design principle for phase-separated proteins by considering condensate micropolarity, potentially leading to drugs with optimal target engagement.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the figshare platform (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29459246)56. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code is available on GitHub and Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16038951)57: small-molecule drug processing and target information extraction (https://github.com/TingtingLiGroup/CondMicroEnv/tree/main/DataProcess), machine learning models about IDR clustering (https://github.com/TingtingLiGroup/CondMicroEnv/tree/main/IDRPredict) and signature similarity analysis of inhibitors and prediction of potency (https://github.com/TingtingLiGroup/CondMicroEnv/tree/main/DrugPotency).

Change history

29 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-02057-1

References

Vamathevan, J. et al. Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 463–477 (2019).

Du, B.-X. et al. Compound–protein interaction prediction by deep learning: databases, descriptors and models. Drug Discov. Today 27, 1350–1366 (2022).

Gorgulla, C. et al. An open-source drug discovery platform enables ultra-large virtual screens. Nature 580, 663–668 (2020).

Hou, C. et al. PhaSepDB in 2022: annotating phase separation-related proteins with droplet states, co-phase separation partners and other experimental information. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D460–D465 (2023).

Abyzov, A., Blackledge, M. & Zweckstetter, M. Conformational dynamics of intrinsically disordered proteins regulate biomolecular condensate chemistry. Chem. Rev. 122, 6719–6748 (2022).

Boeynaems, S. et al. Spontaneous driving forces give rise to protein–RNA condensates with coexisting phases and complex material properties. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7889–7898 (2019).

King, M. R. et al. Macromolecular condensation organizes nucleolar sub-phases to set up a pH gradient. Cell 187, 1889–1906 (2024).

Latham, A. P. & Zhang, B. Molecular determinants for the layering and coarsening of biological condensates. Aggregate 3, e306 (2022).

Ahlers, J. et al. The key role of solvent in condensation: mapping water in liquid-liquid phase-separated FUS. Biophys. J. 120, 1266–1275 (2021).

Ye, S. et al. Micropolarity governs the structural organization of biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 443–451 (2024).

Alshareedah, I., Moosa, M. M., Pham, M., Potoyan, D. A. & Banerjee, P. R. Programmable viscoelasticity in protein–RNA condensates with disordered sticker-spacer polypeptides. Nat. Commun. 12, 6620 (2021).

Klein, I. A. et al. Partitioning of cancer therapeutics in nuclear condensates. Science 368, 1386–1392 (2020).

Ambadi Thody, S. et al. Small-molecule properties define partitioning into biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. 16, 1794–1802 (2024).

Dumelie, J. G. et al. Biomolecular condensates create phospholipid-enriched microenvironments. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 302–313 (2024).

Kilgore, H. R. & Young, R. A. Learning the chemical grammar of biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 1298–1306 (2022).

Howard, T. P. & Roberts, C. W. M. Partitioning of chemotherapeutics into nuclear condensates—opening the door to new approaches for drug development. Mol. Cell 79, 544–545 (2020).

Shin, Y. & Brangwynne, C. P. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 357, eaaf4382 (2017).

Mitrea, D. M., Mittasch, M., Gomes, B. F., Klein, I. A. & Murcko, M. A. Modulating biomolecular condensates: a novel approach to drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 841–862 (2022).

Boija, A., Klein, I. A. & Young, R. A. Biomolecular condensates and cancer. Cancer Cell 39, 174–192 (2021).

Brangwynne, C. P., Tompa, P. & Pappu, R. V. Polymer physics of intracellular phase transitions. Nat. Phys. 11, 899–904 (2015).

Kilgore, H. R. et al. Distinct chemical environments in biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 291–301 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Therapeutic target database update 2022: facilitating drug discovery with enriched comparative data of targeted agents. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D1398–D1407 (2022).

Wishart, D. S. et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1074–D1082 (2018).

Chen, Z. et al. Screening membraneless organelle participants with machine-learning models that integrate multimodal features. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2115369119 (2022).

Wishart, D. S. et al. HMDB 5.0: the Human Metabolome Database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D622–D631 (2022).

Luck, K. et al. A reference map of the human binary protein interactome. Nature 580, 402–408 (2020).

Huttlin, E. L. et al. Dual proteome-scale networks reveal cell-specific remodeling of the human interactome. Cell 184, 3022–3040 (2021).

Go, C. D. et al. A proximity-dependent biotinylation map of a human cell. Nature 595, 120–124 (2021).

Hein, M. Y. et al. A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell 163, 712–723 (2015).

Wan, C. et al. Panorama of ancient metazoan macromolecular complexes. Nature 525, 339–344 (2015).

Nepusz, T., Yu, H. & Paccanaro, A. Detecting overlapping protein complexes in protein-protein interaction networks. Nat. Methods 9, 471–472 (2012).

Shin, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal control of intracellular phase transitions using light-activated optoDroplets. Cell 168, 159–171 (2017).

Nair, S. J. et al. Phase separation of ligand-activated enhancers licenses cooperative chromosomal enhancer assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26, 193–203 (2019).

Zhu, L., Pan, Y., Hua, Z., Liu, Y. & Zhang, X. Ionic effect on the microenvironment of biomolecular condensates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14307–14317 (2024).

Jung, K. H., Kim, S. F., Liu, Y. & Zhang, X. A fluorogenic AggTag method based on Halo- and SNAP-tags to simultaneously detect aggregation of two proteins in live cells. Chembiochem 20, 1078–1087 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. The cation–π interaction enables a Halo-tag fluorogenic probe for fast no-wash live cell imaging and gel-free protein quantification. Biochemistry 56, 1585–1595 (2017).

Subramanian, A. et al. A next generation connectivity map: L1000 platform and the first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell 171, 1437–1452 (2017).

Méndez-Lucio, O., Baillif, B., Clevert, D.-A., Rouquié, D. & Wichard, J. De novo generation of hit-like molecules from gene expression signatures using artificial intelligence. Nat. Commun. 11, 10 (2020).

Alberti, S., Gladfelter, A. & Mittag, T. Considerations and challenges in studying liquid–liquid phase separation and biomolecular condensates. Cell 176, 419–434 (2019).

Rekhi, S. & Mittal, J. Amino acid transfer free energies reveal thermodynamic driving forces in biomolecular condensate formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 122, e2425422122 (2025).

Rogers, D. & Hahn, M. Extended-connectivity fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 742–754 (2010).

Su, M. et al. Comparative assessment of scoring functions: the CASF-2016 update. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59, 895–913 (2019).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 4, 82 (2024).

Campello, R. J. G. B., Moulavi, D. & Sander, J. Density-based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. In Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (eds Pei, J., Tseng, V. S., Cao, L., Motoda, H. & Xu, G.) (Springer, 2013).

Fu, L. et al. ADMETlab 3.0: an updated comprehensive online ADMET prediction platform enhanced with broader coverage, improved performance, API functionality and decision support. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W422–W431 (2024).

Le Guilloux, V., Schmidtke, P. & Tuffery, P. Fpocket: an open source platform for ligand pocket detection. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 168 (2009).

Quaglia, F. et al. DisProt in 2022: improved quality and accessibility of protein intrinsic disorder annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D480–D487 (2022).

Piovesan, D. et al. MobiDB: intrinsically disordered proteins in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D361–D367 (2021).

Emenecker, R. J., Griffith, D. & Holehouse, A. S. Metapredict: a fast, accurate, and easy-to-use predictor of consensus disorder and structure. Biophys. J. 120, 4312–4319 (2021).

Oates, M. E. et al. D2P2: database of disordered protein predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D508–D516 (2013).

Lyons, H. et al. Functional partitioning of transcriptional regulators by patterned charge blocks. Cell 186, 327–345 (2023).

Cohan, M. C., Shinn, M. K., Lalmansingh, J. M. & Pappu, R. V. Uncovering non-random binary patterns within sequences of intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 434, 167373 (2022).

Mendez, D. et al. ChEMBL: towards direct deposition of bioassay data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D930–D940 (2019).

Gilson, M. K. et al. BindingDB in 2015: a public database for medicinal chemistry, computational chemistry and systems pharmacology. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D1045–D1053 (2016).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Ouyang, J. Source data for ‘Navigating condensate micropolarity to enhance small molecule drug targeting’. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29459246 (2025).

Ouyang, J. Code for ‘Navigating condensate micropolarity to enhance small molecule drug targeting’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16038951 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Xiao, X. Lu, M. Zhou and Y. Chen at the Instrumentation and Service Center for Molecular Sciences at Westlake University for the assistance on FLIM and MS, F. Xu at the Westlake University High-Throughput Core Facility for the assistance on SPR data collection, Y. Huang for the assistance on protein purification and J. Ma for the assistance on MS. T.L. thanks support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (T2325003), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Z230014) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFF120470). X.Z. thanks support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22494700, 22494702), Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory Construction Project, Research Center for Industries of the Future at Westlake University and Westlake Laboratory of Life Sciences and Biomedicine (2024SSYS0035). This work was supported by the High-Performance Computing Platform of Peking University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.O., X.Z. and T.L. conceptualized the ideas. X.Z. and T.L. supervised the project. J.O. performed the data and computational analysis. J.C. performed all in vitro and live-cell experiments. Z.W. performed protein expression and purification. J.O. and J.C. wrote the paper. K.Y., T.C., X.Z. and T.L. edited the paper. Y.Q.G. and P.L. provided suggestions and insights that contributed to this study. All authors commented on and approved the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Jose Villegas and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Data details of FDA-approved small molecule drugs.

a, Distribution of heavy atom counts of drugs in TTD and DrugBank. b, Distribution of carbon atom counts of drugs in TTD and DrugBank. c, Family or superfamily of the 58 PS protein targets. d, Family or superfamily of the 704 NPS protein targets. e, Hierarchically-clustered heatmap of the 346 drugs targeting PS proteins. Drugs targeting the same protein superfamily or family were more structurally similar to each other than those targeting different groups. f, Pocket feature comparisons of PS protein targets and NPS protein targets (ns: P value > 0.01). The box plots display the median and the interquartile range (IQR), with the upper whiskers extending to the largest value ≤1.5×IQR from the 75th percentile and the lower whiskers extending to the smallest values ≤1.5×IQR from the 25th percentile (same for g). g, Hydrophobicity comparison for small molecule ligands of PS proteins and NPS proteins. Evaluated with two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (f and g).

Extended Data Fig. 2 PS-state targets definition and greater hydrophobicity for PS-state drugs.

a, Definition of PS-state targets. Created with BioRender.com. b, Function category and number of approved drugs for the 28 defined PS-state targets. c, Source of the 30 PS-unknown targets. Among them, ABL1, IKBKB, HDAC6, KEAP1 and FTL came from PhaSepDB2.1. d-f, Hydrophobicity (d, e) and aqueous solubility (f) comparisons of PS-state-drugs, PS-unknown-drugs and NPS-drugs (ns: P value > 0.01). The box plots display the median and the interquartile range (IQR), with the upper whiskers extending to the largest value ≤1.5×IQR from the 75th percentile and the lower whiskers extending to the smallest values ≤1.5×IQR from the 25th percentile (same for g-i). g-i, Hydrophobicity (g, h) and aqueous solubility (i) comparisons of small molecule drugs targeting PS-state targets with long IDRs, PS-state targets without long IDRs, PS-unknown targets and NPS targets (P value, ****P < 0.00005, ***P < 0.0005, **P < 0.005, *P < 0.05, ns P > 0.05). PS-state (IDR)-drugs (P = 0.0065 for g, 0.039 for h, 0.025 for i, PS-state (nonIDR)-drugs; P = 2.2e-5 for g, 7.8e-7 for h, 2.1e-5 for i, PS-unknown-drug; P = 1.3e-10 for g, 7.9e-18 for h, 4.1e-34 for i, NPS-drugs); PS-state (nonIDR)-drugs (P = 6.0e-7 for g, 3.4e-8 for h, 2.5e-5 for i, PS-unknown-drug; P = 5.1e-9 for g, 1.3e-10 for h, 4.9e-14 for i, NPS-drugs). Sample size is shown on the bottom (d-i). Evaluated with one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (d-i).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Hydrophobicity characteristics of endogenous metabolites.

a, Hydrophobicity comparison of metabolites with varying degrees of interaction strength with PS proteins. PS*n refers to n PS proteins present in the associated protein set. The box plots display the median and the interquartile range (IQR), with the upper whiskers extending to the largest value ≤1.5×IQR from the 75th percentile and the lower whiskers extending to the smallest values ≤1.5×IQR from the 25th percentile (same for b and c). b, Box plots showing hydrophobicity comparison of PS-related and PS-unrelated metabolites when setting different threshold of defining PS-related metabolites. PS*n refers to the requirement of at least n PS proteins for the definition of PS-related metabolites. c, Box plots showing hydrophobicity comparison of metabolites in PS-enriched and NPS-enriched subnetworks when four out of the five PPI resources were used in the construction of PPI network. Evaluated with one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (b and c).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Sequence properties and drug hydrophobicity for varying IDR clusters.

a, Hierarchically-clustered heatmap that shows the nonpolar amino acids enrichment of IDRs in the nonpolar residue-enriched cluster. Each value in the heatmap represents the relative aa fraction (fraction divided by the total fraction of all nonpolar aas, similar in b and c). b, Hierarchically-clustered heatmap that shows the hydrophilic amino acids enrichment of IDRs in the hydrophilic residue-enriched cluster. c, Hierarchically-clustered heatmap that shows the charged amino acids enrichment of IDRs in the charge block cluster. d, Two instances including TOP2A and BRD2 that possess charge blocks within IDRs. NCPR, net charge per residue; the positions of charge blocks (10-residue window NCPR \(\ge\) abs (5)) is shown as dark blue bars. e-g, Hydrophobicity (e, f) and aqueous solubility (g) comparisons of FDA-approved small molecule drugs pertinent to varying IDR clusters (P value, ****P < 0.00005, ***P < 0.0005, **P < 0.005, *P < 0.05, ns P > 0.05). nonpolar-drug (P = 1.9e-10 for e, 2.1e-11 for f, 0.0029 for g, hydrophilic-drugs; P = 0.00081 for e, 0.00029 for f, 0.0013 for g, charge-drugs; P = 2.2e-22 for e, 2.1e-30 for f, 2.0e-31 for g, NPS-drugs); hydrophilic-drugs (P = 0.00013 for e, 3.3e-5 for f, 0.00018 for g, charge block-drugs; P = 0.023 for f, 2.1e-11 for g, NPS-drugs); charge block-drugs (P = 0.0034 for e, 0.025 for f, NPS-drugs).The box plots display the median and the interquartile range (IQR), with the upper whiskers extending to the largest value ≤1.5×IQR from the 75th percentile and the lower whiskers extending to the smallest values ≤1.5×IQR from the 25th percentile. Sample size is shown on the bottom. Evaluated with one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (e-g).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Confocal images of mCherry-CRY2 and properties of O-SBD-Halo.

a, Illustration showing that mCherry-CRY2 and ESR1(185-595 aa)-mCherry-CRY2 did not form droplets upon blue light induction. This indicates that constructs without IDR sequence cannot form condensates, even under blue light induction. Scale: 10 µm. b, The chemical structure and fluorescence property of O-SBD-Halo. c, Fast FLIM images of O-SBD-Halo in solvent mixtures of glycerol and ethylene. Scale: 10 µm. d, Fluorescence lifetime decay curves of O-SBD-Halo in ethylene glycol-glycerol solvent mixtures with varying ratios. For example, 30% glycerol (h = 0.081 Pa·s), 50% glycerol (h = 0.183 Pa·s), 70% glycerol (h = 0.426 Pa·s)10. The fluorescence time of O-SBD-Halo remained unchanged across different concentrations of ethylene glycol.

Extended Data Fig. 6 FLIM imaging for condensates of varying IDR clusters.

a, (left) O-SBD-Halo labeled FLIM images of DDX4 (IDR)-Halo and DDX4 (IDR)-Halo-CRY2; (right) Dot plots comparing micropolarity in these two scenarios. Evaluated with one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (P value: *P < 0.05, P = 0.010). Representative images were selected from 6 and 14 cells (n = 6 and n = 14), respectively. Centerline and error bars represent mean value +/- SD. DDX4 (IDR)-Halo did not form condensates in cell. Conversely, DDX4 (IDR)-Halo-CRY2 was able to form condensates. When condensate formation did not occur, the micropolarity was evenly distributed within the cell, exhibiting a relatively hydrophilic microenvironment. b, O-SBD-Halo labeled FLIM images of condensates for nonpolar and hydrophilic residue-enriched IDRs. c, Class probability heatmap of newly-screened IDRs for each category using our random forest classifier. d, O-SBD-Halo labeled FLIM images of condensates for IDRs obtained using random forest classifier. Scale: 10 µm. e, Plots showing results for FRAP analyses of the average recovery traces of ESR1 IDR condensates. Scale: 1 µm. f, Chemical structure of BODIPY-Halo. g, Fast FLIM images of BODPY-Halo labeling ESR1 IDR condensates. Scale: 10 µm. These results indicate that ESR1 IDR condensates exhibit liquid-like mobility and possess a relative lower viscosity within their microenvironment.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Relationships of inhibitors’ potency with hydrophobicity and affinity.

a, The number of inhibitors (up) and normalized expression (down) of ESR1, EGFR, KDR and AR in varying cancer cell lines. Black frames indicate that targets are highly expressed in these cell lines, which were selected for further correlation analysis. b, Scatter plots and regression plots showing correlation of hydrophobicity and potency of inhibitors (upper row), correlation of affinity and potency of inhibitors (below row). rs: Spearman correlation; p: P value; ns: no significance. Solid line and shaded area represent the regression line and the 90% confidence interval of regression plots, respectively. Evaluated with two-sided Spearman correlation analysis. c, Scatter plot showing performance of the regressor that predicted the potency of AR inhibitors in VCAP cell line. pcc: Pearson correlation coefficient; p: P value; N: data size. Evaluated with two-sided Pearson correlation analysis. d, Heatmap showing the top-5 most important features across all leave-one-outs of the regressor that predicted the potency of AR inhibitors in VCAP cell line. e-f, Scatter plots showing relationships of potency with affinity and hydrophobicity for EGFR inhibitors in HCC515 cell line (e) and AR inhibitors in VCAP cell line (f). Red frame refers to inhibitors exhibiting high affinity and great hydrophobicity. Color coding of data points: red color refers to inhibitors exhibiting high potency. Unit of docking score: kcal/mol.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Experimental assessment of inhibitors’ affinity to ESR1.

Dissociation constants were determined by the high-throughput and high-sensitivity surface plasmon resonance (SPR) system.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Partitioning of ESR1 inhibitors into ESR1 and other types of condensates.

a, Microscopy images showing droplets of MBP-ESR1 IDR. Scale: 10 µm. b, Chemical structure of SBD methyl-ester. c, Free SBD (SBD methyl-ester) labeled Fast FLIM images and dielectric constant of condensates formed by MBP-ESR1 IDR. Scale: 10 µm. d, Scatter plot and regression plot showing correlation of affinity with partition coefficient of inhibitors. Affinity is represented by Kd value. Data are represented as mean value +/- SD in three independent mass spectrometry experiments. Solid line and shaded area represent the regression line and the 90% confidence interval of regression plots, respectively (same for e-i). ns, no significance: P value > 0.05. Evaluated with two-sided Spearman correlation analysis (same for e-h). e-f, Scatter plots and regression plots showing correlation of affinity with hydrophobicity. Affinity is represented by docking score (e) and Kd value (f), respectively. g-i, Free SBD (SBD methyl-ester) labeled Fast FLIM images and dielectric constant of the condensates formed by ELP V-120 (g), IDR of FUS (h) and IDR of DDX4 (i) before and after the addition of ESR1 inhibitors (up); plots showing ESR1 inhibitors’ partitioning into these condensates (down). ELPs are bioengineered low-complexity peptide polymers composed of multiple pentameric repeats of VPGXG, where the guest residue (X) can be any amino acid except proline. V-120 consists exclusively of pentamers with valine as the guest residue. Data are represented as mean value +/- SD in three independent mass spectrometry experiments. rs: Spearman correlation coefficient; p: P value. Scale: 10 µm. j, Distribution of charged residues in FUS IDR and DDX4 IDR.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Influence of RNA on the micropolarity of condensate microenvironment.

a, Confocal images showing that RNA were co-localized with condensates formed by IDR of DDX4 (1-236 aa), ESR1 (79-174 aa) and FUS (1-286 aa). b, Free SBD (SBD-methyl-ester) labeled Fast FLIM images and dielectric constant of these three condensates when co-incubated with different concentrations of RNA. Scale: 10 µm. As RNA concentration increased, the micropolarity of the highly polar DDX4 condensates remained unchanged. While FUS condensates displayed a slight decrease in micropolarity with increasing RNA concentration and ESR1 condensates exhibited a slight increase, these fluctuations were relatively subtle when compared to the variations between the micropolarity of condensates enriched with nonpolar residues and that enriched with hydrophilic or charged residues. Therefore, the addition of RNA influences the microenvironment slightly and may not significantly influence drug partitioning. The FLIM image of micropolarity data for DDX4 IDR at 0 µM RNA, serving as the control, is referenced from Extended Data Fig. 9i, where DDX4 IDR was shown without inhibitor. Similarly, the image for MBP-FUS IDR at 0 µM RNA is referenced from Extended Data Fig. 9h, where MBP-FUS IDR was presented without inhibitor.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–7, Note and references.

Supplementary Data 1

The sources of ESR1 inhibitors, including supplier information and compound purity data, are provided.

Supplementary Data 2

Statistical source data for Supplementary Table 2.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Full-length, unprocessed gels.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ouyang, J., Chen, J., Wu, Z. et al. Navigating condensate micropolarity to enhance small-molecule drug targeting. Nat Chem Biol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-02017-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-02017-9